Abstract

Quantum dots are promising candidates for more efficient and brighter light-emitting diodes in display and lighting applications. However, due to low carrier concentrations and strong confinement, the electroluminescence efficiency and brightness are hindered by low exciton formation rate, i.e. the probability of electrons meeting holes. Here, we demonstrate that the weak hole confinement, induced inter-dot hole diffusion in quantum dots with large CdZnSe cores and thin ZnS shells, allows more efficient exciton formation. As a result, we achieve a peak external quantum efficiency of 30.7%, a maximum luminance exceeding 1.9 million cd m-2 in green quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Moreover, efficient utilization of carriers depresses the Joule heat generation, allowing us to achieve a T95 operational lifetime (time for the luminance to decrease to 95% of the initial value) of 21,900 hours at 1000 cd m−2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solution-processed quantum dot light-emitting diodes (QD-LEDs) are emerging as leading candidates for next-generation displays and lighting, owing to their high emission efficiency, narrow spectral bandwidth, and low-cost manufacturing1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Red, green, and blue devices now routinely surpass external quantum efficiencies (EQEs) of 20%8,9,10. Yet, sustaining exceptional efficiency at ultrahigh brightness remains a central challenge, particularly for applications in augmented and virtual reality as well as ultra-high-definition displays11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Although approaches including interlayer engineering, charge-transport layer modification10,21,22,23,24,25, and energy-level optimization11,14,26,27,28 have improved performance, the exciton formation rate continues to limit both brightness and EQE.

Unlike photoluminescence, which always generates electrons and holes in pairs, electrons and holes are injected separately during the electroluminescence process. Excitons only form when electrons and holes are injected into the same QD29. Therefore, the exciton formation probability is highly dependent on the carrier concentration. However, in our recent work, we found the carrier population per QD in the operational device was low, as determined by electrically excited transient absorption (EETA) spectroscopy6,7,10. This leads to a low exciton formation probability and low luminance.

Therefore, more efficient exciton generation at low carrier concentrations is very important for improving the performance of QD-LED. Here, we use the Monte Carlo model to investigate the carrier injection and formation in QD-LEDs30, and we find that increasing the diffusion ratio of carriers can significantly improve the probability of exciton formation, especially when the injection increases, even a small diffusion across QDs can enhance the exciton formation dramatically. Inspired by this, we propose a QD structure with a large CdZnSe core and thin ZnS shell to reduce the hole confinement and enhance hole diffusion across QDs. By further fine-tuning the balance between carrier confinement and diffusion by shell engineering of QDs, we achieve a record EQE of 30.7% (the certified EQE of 29.5%), a maximum luminance exceeding 1.9 million cd m−² in green QD-LEDs. Efficient luminance also reduces heat generation in devices, leading to a record T95 operational lifetime of 21,900 h at 1000 cd m−². To our knowledge, these three important parameters—EQE, maximum luminance, and operational lifetime (T95@1000 cd m−²)—are all currently the highest reported values for green QD-LEDs.

Results

Carrier diffusion accelerates the electroluminescence

The large diffusion length in all inorganic-LEDs makes it difficult to achieve good performance as the device size decreases31. However, the situation is the opposite in QD-LEDs, where the strong confinement inside individual QD emitters restricts the injection and diffusion of carriers, especially in thick ZnS shell-coated QDs11,26,27,32. As a result, radiative recombination is dependent on exciton formation through injecting an electron and a hole into one QD (Fig. 1a), and appropriate carrier diffusion is theoretically beneficial for improving luminance in QD-LEDs (Fig. 1b).

The schematic diagrams showing the exciton formation with (a) and without (b) carrier diffusion in the QD layer between electron transport layer (ETL) and hole transport layer (HTL). c The Monte Carlo simulated exciton formation number in the QD layer with/without carrier lateral migration (see “Method” for details). d The relationship between the exciton formation rate and carrier migration proportion under high/low carrier concentration conditions.

To further investigate the impact of diffusion and injection on device performance, we build a Monte Carlo model to simulate the exciton formation probability. A 100 × 100 matrix with periodic boundary conditions was employed to represent a single QD layer, where each matrix element corresponds to a QD (as described in the “Methods”). We found that, while maintaining a constant electron-hole injection rate, a small increase in the lateral diffusion rate can effectively enhance the formation of excitons (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Especially at high charge concentrations, a little increase in diffusion leads to dramatically improved exciton formation rates (Fig. 1c, d).

Increasing carrier diffusion of quantum dots

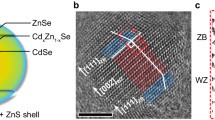

Inspired by this calculation, we introduce green core/shell QDs with a large CdZnSe core and a thin ZnS shell (referred to as L/T-QDs, see scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) for nanostructure of QDs in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3) to reduce the carrier confinement and promote the lateral diffusion. We choose to lose hole confinement in this work because it also benefits the electron-hole injection balance. Traditional QDs with a small CdZnSe core and a thick ZnS shell were also synthesized (referred to as S/T-QDs, Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). These have the same average size (approximately 11 nm) and PL peaks (540 nm, Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7), while their full width at half-maximum (FWHM) are 41 nm and 25 nm, respectively. The broader FWHM of photoluminescence emission for L/T-QDs is mainly attributed to the larger CdZnSe core, which possesses a greater extent of carrier delocalization.

To verify the enhanced lateral diffusion of carriers in L/S-QDs, we performed time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) and nanosecond transient absorption (nsTA) spectroscopy. For II-VI QDs, the ground state bleaching (GSB) signal of nsTA is mainly contributed by electrons because of much higher degeneracy in the valence band (Fig. 2a)33. Therefore, we can verify the presence and type of carrier diffusion by comparing the energy evolution of the GSB signal with that of recombination. The redshift of recombination confirmed the occurrence of carrier diffusion or Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) process, while the energy redshift of the GSB signal indicates electron diffusion or FRET process (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Fig. 8). Given no change of peak position in the GSB signal while a noticeable redshift in TRPL, we conclude that the diffusing occurs in holes for L/S-QDs (Fig. 2d–f).

Schematic diagrams of a carrier states of QDs, b electron migration, and c hole migration between adjacent QDs. GSBe-h signal of ground state bleaching of electron-hole pairs, GSBe signal of ground state bleaching of excited-state electrons, GSBh energy of ground state bleaching of holes, PLe-h signal of recombination of electron-hole pairs. GSBe-h is approximately equal to GSBe, GSBh is approximately equal to 0. Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) and nanosecond transient absorption (nsTA) spectra of (d) QDs with a small core and a thick shell (S/T-QDs) and (e) QDs with a large core and a thin shell (L/T-QDs). f Peak positions of TRPL and nsTA spectra change with time of S/T-QD and L/T QD film. g Ground state bleaching dynamics of nsTA spectra. h PL decay dynamics. i QD structure illustration and energy level diagram; Top: S/T-QDs; Bottom: L/T-QDs.

To further analyze the probability of hole diffusion, we calculated the probability of carriers overcoming shell barriers to adjacent QDs by the Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin (WKB) quantum tunneling model (as described in the “Methods”, Supplementary Fig. 9). Since tunneling probability affect by both the effective mass and the structure of barrier, we observe a larger probability for hole tunneling when the ZnS shell is less than 1.5 nm in CdZnSe/ZnS QDs. For L/T-QDs with 3 monolayers (ML) ZnS (the ZnS shell thickness: ~0.92 nm), the electron/hole tunneling probability ratio is 0.68, which indicates a higher hole tunneling probability.

The lateral diffusion of holes can also be confirmed from the dynamics of PL decay in QDs, which is accelerated by QDs with non-negligible lateral carrier diffusion due to easier exciton dissociation34,35. As shown in Fig. 2g, h and Supplementary Fig. 10, nsTA decays reveal the charge carriers—which are formed from dissociated exciton - lifetime remains long, indicating the PL quenching is not induced by trapping, instead it is caused by exciton dissociation—electrons and holes are still alive in QDs, they just separate from each other, so they do not recombine and emit light. However, above discussed situation is for photoexcitation, under electrical excitation, the charge carrier concentration is higher, so they have a much higher chance to stay together and emit light. For L/T-QDs with thin ZnS shells, the large CdZnSe core ensures the lateral diffusion of holes. The thin ZnS shell passivates surface defects on the cores while not affecting the lateral diffusion of holes (Fig. 2i).

To investigate the effect of core size and shell thickness of L/T-QDs on hole diffusion, we further synthesized L/T-QDs with different core sizes (size 1-4) and a 1 ML ZnS shell (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). With the increase of core sizes, the PL lifetime of L/T-QD films gradually shortens, indicating an enhanced hole diffusion. Furthermore, compared to L/T-QDs with a core size of 9.85 nm (size 3), the PL lifetime of QDs with larger core sizes (size 4, 10.56 nm) shows almost no decrease, indicating that there is no further increase in hole diffusion. L/T-QDs with CdZnSe core (size 3) and different ZnS shells were also synthesized to verify the effect of shell thickness on lateral hole diffusion (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14). The PL lifetime decreases from 3.68 ns for L/T-QDs 5 ML to 1.58 ns for L/T-QDs 1 ML (Supplementary Fig. 15). Meanwhile, the tunneling probability of holes in L/T-QDs with 5 ML of ZnS (an average ZnS shell thickness of 1.27 nm) are 1.14 × 10−5, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 9). Reducing the ZnS shell thickness to L/T-QDs with 3 ML of ZnS (an average ZnS shell thickness of 0.92 nm) results in tunneling probability for holes of 2.08 × 10−4, respectively. The tunneling probability of holes in L/T-QDs with 1 ML of ZnS (an average ZnS shell thickness of 0.34 nm) is 4.63 × 10−2, respectively. These data indicate that as the thickness of the ZnS shell decreases, the tunneling probability of holes increases exponentially. Therefore, the thin ZnS shell in L/T-QDs (a QD structure with a large CdZnSe core and thin ZnS shell) ensures that holes can effectively migrate under the condition of a thin barrier thickness.

Increasing luminance by large hole diffusion

As discussed above, the weak hole confinement in L/T-QDs facilitates lateral hole diffusion and exciton formation, especially at high charge carrier concentrations under electrical excitation. However, the effect of the electric field force on the charge carriers in working QD-LEDs should also be considered, we calculated the Coulomb interaction force and the average electric field force under different driving voltages (as described in the “Methods”, Supplementary Fig. 16). To eliminate any controversy, we tested the EETA spectra under reverse voltage for QD-LEDs (Supplementary Fig. 17a). The devices usually do not experience carrier injection under reverse voltage, allowing us to consider the electric field as a mean field. This is also evidenced by the linear increase of the QD Stark signal with voltage (Supplementary Fig. 17b). Furthermore, it is found that the signal intensity of the Stark effect at 9 V is only comparable to that of the device at a reverse voltage of −1.7 V (Supplementary Fig. 17c). This value is also close to the results obtained from our model simulations (When the driving voltage is less than 2.1 V, the electric field force is less than the Coulomb force, Supplementary Fig. 16). The agreement between the test results and the model simulation results indicates the reliability of our model. The Coulomb interaction forces show no order-of-magnitude difference and even larger than the electric field force at a low driving voltage. These results indicate that the lateral charge diffusion cannot be neglected and is important for electroluminescence.

We then fabricated QD-LEDs with a conventional structure of ITO/PEDOT:PSS/TFB/QDs/ZnMgO/Al using S/T-QDs and weak confinement L/T-QDs with different MLs of ZnS shell (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 14). The nearly identical positions of the valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) indicate that these two types of QD-LEDs exhibit the same HTL/QD/ETL energy level structure (Supplementary Fig. 18 and Table 1). Increasing the thickness of the ZnS shell can enhance the carrier confinement potential and reduce leakage current, thereby demonstrating a decreased current density of single-carrier devices (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 19)36. The device using L/T-QDs with 1 ML ZnS exhibits higher electron/hole injection densities and leakage current density, resulting in similar electron concentration compared to S/T-QD based device (Fig. 3b–d and Supplementary Fig. 20). LED using L/T-QDs with 1 ML ZnS exhibits a higher luminance of 1,329,000 cd m−2 compared to 970,000 cd m−2 for the device using S/T-QDs at 9 V (Fig. 3d). The enhanced hole migration of L/T-QDs can effectively improve hole transport (Fig. 3b). Transient electroluminescence (TrEL) dynamics and capacitance-voltage (C-V) characterization indicate that QDs with lateral hole diffusion enhance exciton formation and in QD-LEDs (Supplementary Fig. 21). Thus, we have not only demonstrated our standpoint regarding hole migration in QD films from the perspectives of theoretical simulations and experimental characterizations, but we have also verified, through the carrier dynamics of devices, that hole migration enhances exciton formation and improves device brightness.

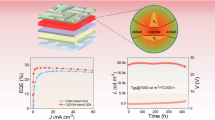

a Schematic structure and cross-sectional TEM image of the QD-LED (scale bar is 100 nm). b Current density (J)-voltage (V) curves of electron-only-device (EOD) and hole-only-device (HOD). c Average electron population per QD (<Ne>) as a function of bias. d Current density-voltage-luminance (L) curves. e External quantum efficiency (EQE)-luminance curves. f Statistical box diagrams of EQE, error bars represent the standard deviation of over 30 independent samples.

The enhancement in the brightness of the above device validates our calculations, and we seek to further increase charge concentration to promote exciton formation. Our previous work demonstrated that the addition of a ZnS shell could inhibit the leakage of electrons to the hole transport layer, thereby increasing the electron concentration in QDs36. This encourages us to increase the thickness of the ZnS shell on the L/T-QDs. Consequently, QD-LEDs based on L/T-QDs with 3 ML ZnS exhibit the highest electron concentration per QD (Fig. 3c). In addition, the slightly increased ZnS shell thickness allows L/T-QDs with 3 ML ZnS to still maintain significant hole diffusion, as evidenced by the shortening of the PL lifetime in QD films (Supplementary Fig. 22). As a result, using L/T-QDs with 3 ML ZnS, our LEDs exhibit a broader FWHM (~39 nm) of EL, which can be narrowed to 28 nm by a planar microcavity, basically meeting the requirements for display applications (Supplementary Fig. 23). And they achieve a luminance of over 1,950,000 cd m−2 at 10 V and an increased maximum EQE and current efficiency (CE) of 30.7% and 147 cd A-1, respectively, compared to 20.2% for devices using S/T-QDs (Fig. 3d, e and Supplementary Fig. 24). The turn-on voltage is significantly reduced due to the accelerated exciton formation induced by the lateral hole diffusion and increased electron concentration. Meanwhile, statistical results from over 30 devices further confirm the EQE enhancement and reproducibility of devices with L/T-QDs (Fig. 3f). The National Institute of Metrology of China validated our devices with a certified peak EQE of 29.5% (Supplementary Fig. 25). The performance improvement is attributed to the most efficient exciton generation, resulting from balanced carrier injection and diffusion in the QD layer. As the ZnS shell thickness increases from 1 ML to 3 ML, the device efficiency gradually improves, with the average EQE increasing from 23.32% to 29.64%. However, when the ZnS shell thickness is further increased to 5 ML, the average EQE decreases to 27.37% (Supplementary Figs. 26–28).

Efficient exciton generation for long operational lifetime

The efficient luminance of L/T-QDs significantly reduces non-radiative heat generation during operation6,37,38. The surface temperature of the device increases by only 2.3 °C as the brightness rises from 0 to 300,000 cd m−2 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Figs. 29–31). This low heat generation ensures exceptionally high operational stability for our devices. The T95 operational lifetime (the time taken for luminance to degrade to 95% of the initial luminance (L0)) at an initial brightness of 1000 cd m−2 is 21,938 h for L/T-QD-based QD-LEDs, with an acceleration factor of 1.85 (Fig. 4b, c). The T95 operational lifetimes at an initial brightness of 1000 cd m−2 are 10,630 and 13,316 h for LEDs with S/T-QDs and L/T-QDs 1 ML ZnS, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 32). This marks the first time a T95 lifetime exceeds 20,000 h, setting record values for EQE, maximum luminance, and T95 at 1000 cd m−2 for reported green QD-LEDs (Fig. 4d–f).

a The surface temperature of devices using L/T-QDs 3 ML ZnS under different brightness. b T95 lifetime measurements at different initial luminance for the acceleration factor (n) extrapolation. Inset: EL spectrum of LEDs with L/T-QDs 3 ML ZnS at 3 V. c L-time-V. d–f EQE, maximum luminance, and T95 at 1000 cd m−2 compared to other state-of-the-art green QD-LEDs in previous reports.

In summary, we propose a strategy to simultaneously accelerate carrier injection and diffusion across QDs, maximizing the exciton formation rate to achieve high EQE and brightness in green QD-LEDs. We synthesized green QDs with a structure featuring a large CdZnSe core and a thin ZnS shell to reduce confinement and enhance hole diffusion. Combined with precise control of ZnS thickness to balance carrier confinement and diffusion, we achieve a record EQE exceeding 30% and a maximum luminance exceeding 1.9 million cd m−2 in green QD-LEDs. Efficient carrier utilization also reduces Joule heating, allowing a record T95 operational lifetime of 21,900 h at 1000 cd m−2. This work presents a novel approach to utilize carriers more efficiently in QD-LEDs to achieve ultra-bright luminance.

Methods

Materials

Zinc acetate (Zn(OAc)2, 99.99%), 1-octadecene (ODE, 90%), selenium (Se, 99.99%, Powder), trioctylphosphine (TOP, 90%), and oleic acid (OA, 90%) were purchased from Alfa Aesar. Sulfur (S, 99.998%, powder), Cadmium oxide (CdO, 99.99%), magnesium acetate tetrahydrate (Mg(OAc)2·4H2O, 99.98%), Zinc acetate dihydrate (Zn(OAc)2·2H2O, 99.99%), tetramethylammonium hydroxide pentahydrate (TMAH, 99%), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 99.7%), n-octane (99%), ethanol (99.8%) and chlorobenzenes (99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Poly (9, 9-dioctylfluoro-co-N - (4- (3-methylpropyl)) -diphenylamine) (TFB) and Poly(ethylenedioxythiophene): polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) were purchased from dye sources of United States and Heraeus of Germany, respectively. All chemicals were used as received without any purification.

Preparation of precursors

Zn(OA)2 precursor: 20 mmol of Zn(OAc)2, 20 mL of OA, and 20 mL of ODE were placed in a 100 mL three-neck flask, heated to 120 °C for 15 min under vigorous stirring to degas, then raised to 220 °C until a clear solution formed. Cd(OA)2 precursor: 10 mmol of CdO, 10 mL of OA, and 10 mL of ODE were loaded into a 100 mL three-neck flask, heated to 120 °C for 15 min under vigorous stirring to degas, then raised to 240 °C until a clear solution formed. Se precursor-1: 10 mmol of Se powder and 10 mL of ODE were added into a 25 mL single-neck flask and ultrasonicated for 30 min until fully dispersed. Se precursor-2: 12 mmol of Se powder and 120 mL of ODE were loaded into a 250 mL three-neck flask, heated to 120 °C for 15 min under vigorous stirring to degas, then to 240 °C for 200 min, and further to 280 °C until the solution turned light reddish-brown (about 60 minutes). S precursor: 20 mmol of S powder and 40 mL of TOP were loaded into a 100 mL single-neck flask and ultrasonicated for 30 min until fully dissolved.

Synthesis of quantum dots

Synthesis of S/T-QDs: 0.18 mmol of CdO, 3 mmol of Zn(OAc)2, 6 mL of OA, and 14 mL of ODE were placed in a 100 mL three-neck flask, degassed at 120 °C for 15 min, and heated to 290 °C. Two microliters of Se precursor-1 was quickly injected and reacted for 10 min to grow CdZnSe cores. The temperature was then raised to 310 °C, and 10 mL of S precursor was added dropwise at 4 mL h−1, with 2 mL Zn(OA)2 precursor co-injected for every 2 mL of S precursor. After complete addition, the reaction was cooled naturally to room temperature to yield S/T QDs.

Synthesis of L/T-QDs: 0.18 mmol of CdO, 3 mmol of Zn(OAc)2, 6 mL of OA, and 14 mL of ODE were loaded into a 100 mL three-neck flask, degassed at 120 °C for 15 min, and heated to 290 °C. Two microliters of Se precursor-1 was quickly injected and reacted for in min to form CdZnSe cores. To grow large CdZnSe cores, Cd, Zn, and Se precursors were added simultaneously. For example, to obtain 9.85 nm cores, 0.4 mL of Cd(OA)2 precursor and 1 mL of Zn(OA)2 precursor were added at 300 °C and maintained for 5 min, followed by dropwise addition of Se precursor-2 (6 mL) over 20 min. This cycle was repeated three times, with core size controlled by the number of cycles. For thin ZnS shell growth (e.g., 3 ML), 2 mL of Cd(OA)2 precursor was added at 310 °C and maintained for 5 min, followed by dropwise addition of S precursor (2 mL) at 4 mL h−1. The reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature to yield L/T QDs. The QDs were purified with ethanol and n-hexane, and dispersed in n-octane for characterization and device fabrication.

Fabrication of quantum-dot light-emitting diodes

The indium tin oxide (ITO) glass substrate was sonicated sequentially in detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropanol (15 min each), dried with nitrogen, and treated with UV-ozone for 20 min. The PEDOT:PSS solution was filtered (0.45 μm), drop-cast onto the ITO substrate, spin-coated at 5000 rpm, and excess PEDOT:PSS was removed to expose the electrodes. The film was annealed at 135 °C for 15 min in air, then transferred to a nitrogen-filled glove box. TFB solution (8 mg mL⁻¹ in chlorobenzene) was spin-coated at 3000 rpm for 30 s and annealed at 150 °C for 30 min. QD solution (15 mg mL⁻¹ in octane) and ZnMgO nanoparticle dispersion (30 mg mL⁻¹ in ethanol) were spin-coated at 2000 rpm and 2500 rpm, respectively, for 40 s each. Excess leaky electrode material was removed with chlorobenzene, followed by annealing at 60 °C for 30 min. Finally, a 100 nm Al cathode was thermally deposited in a vacuum chamber.

Material characterization

TRPL was measured using a Horiba 4200A-SCS+DeltaFlex TrEL test system. TEM images were obtained on a JEOL JEM-2010 at 200 kV. STEM imaging was conducted on a JEOL ARM200F with aberration correction at 200 kV. EDS mapping was carried out on an FEI Talos F200X with four symmetrically designed spectrometers. Absorption and PL spectra were recorded using a Marine PC2000-ISA spectrophotometer. PL QY was measured with a Marine optical ISP-50-8-I absolute PLQY system in an integrating sphere. PL decay was collected on an Edinburgh FLS1000 single-photon counting spectrometer. UPS was performed on a Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250 XI using a He I discharge lamp.

Device testing

Current density-voltage characteristics were measured using an Agilent 4155 C semiconductor parameter analyzer with a calibrated Newport silicon diode. Brightness was calibrated with a Photo Research PR735 spectrometer. Device lifetime was evaluated using a QD-LED Aging Life Test System (D3000-adv).

Electro-excited transient absorption measurement

Electrical pulses (1 kHz, 10 μs) generated by a Keysight 33512B were applied to QD-LEDs. A Supercontinuum white laser (Leukos, Disco) was split into probe and reference beams. Using an electronic time-delay module, the probe beam was directed to the excitation area of the device and collected by a monochromator and charge-coupled device, while the reference beam was recorded to eliminate optical jitter. The measured signal corresponded to the difference in probe intensity with and without the pump electrical pulse.

Monte Carlo simulations

Charge injection currents in QD-LEDs were described by the drift–diffusion model. Near the turn-on voltage, the applied bias offsets the built-in field, making the drift current negligible; thus, only diffusion current was considered. According to the Fick’s first law of diffusion, the diffusion carrier current density can be written as:

[Where \({P}_{{\mbox{E}}\to {\mbox{Q}}}\) (\({P}_{{\mbox{Q}}\to {\mbox{E}}}\)) is the probability for electrons to transport from ETL (QD layer) to QD (ETL), and \({P}_{{\mbox{H}}\to {\mbox{Q}}}\) (\({P}_{{\mbox{Q}}\to {\mbox{H}}}\)) is the probability for holes to transport from HTL (QD layer) to QD (HTL). \({n}_{{\mbox{ETL}}/{\mbox{HTL}}/{\mbox{QD}}}\) and \({p}_{{\mbox{ETL}}/{\mbox{HTL}}/{\mbox{QD}}}\) are the counts of electrons and holes in the ETL/HTL/QD layers, respectively. We assume \({P}_{{\mbox{E}}\to {\mbox{Q}}}\) and \({P}_{{\mbox{H}}\to {\mbox{Q}}}\) are also similar in two types of devices. We further assumed \({P}_{{\mbox{E}}\to {\mbox{Q}}}={P}_{{\mbox{Q}}\to {\mbox{E}}}={P}_{{\mbox{n}}}\), and \({P}_{{\mbox{H}}\to {\mbox{Q}}}={P}_{{\mbox{Q}}\to {\mbox{H}}}={P}_{{\mbox{p}}}\) to simplify our calculation. Thus, the numbers of injected electron (\({N}_{{\mbox{e}}}\)) and hole (\({N}_{{\mbox{h}}}\)) can be described as:

The irradiative recombination current in QD-LEDs is generated by direct vertical charge injection and lateral charge migration. We use 100 × 100 and (XX nm) QDs in QD-LEDs within an area of XX μm2, and set \({n}_{{\mbox{QD}}}\) = \({p}_{{\mbox{QD}}}\) = 0 as the initial condition. \({P}_{{\mbox{n}}}\) and \({P}_{{\mbox{p}}}\) are set to be 0.0512 and 0.0256. We use injected carrier numbers divided by QD population in the matrix as injection probability:

Where \({N}_{{\mbox{e}}}\) and \({N}_{{\mbox{h}}}\) denotes the number of electron and holes injected into QDs, respectively. The corresponding injection probabilities are denoted by \({P}_{{\mbox{e}}}\) and \({P}_{{\mbox{h}}}\), respectively.

We have further taken Columbic interaction into consideration during the charge injection process, a 60 meV exciton binding energy was adopted in our calculations, according to the Boltzmann distribution, this will cause around 10 times difference in terms of injection probability. When there is an electron in a QD, the probability of injecting another electron into the QD is denoted as \({P}_{{\mbox{ee}}}\), which is 10 times lower than those empty QDs. Conversely, the probability of injecting another hole to format an exciton is 10 times higher, denoted as \({P}_{{\mbox{eh}}}\). For the QDs that are positively charged, the probability of injecting one more hole into QDs (\({P}_{{\mbox{hh}}}\)) is also 10 times smaller, and the probability of injecting another electron to format an exciton is 10 times higher (denoted as\(\,{P}_{{\mbox{he}}}\)).

The other formation origination of exciton comes from lateral charge migration. We then consider the probability of carrier lateral charge migration (denoted as Pl) for one injection cycle. For an electron or a hole in a QD, the probability of that migrating into an adjacent neutral QD is denoted as \({P}_{{\mbox{le}}}\) or \({P}_{{\mbox{lh}}}\), respectively. The probability of an electron or hole migrating into an adjacent neutral QD with a hole or electron to format an exciton is denoted as \({P}_{{\mbox{leh}}}\) or \({P}_{{\mbox{lhe}}}\), respectively. Conversely, the probability of an electron or hole migrating into QD with an electron or hole is denoted as \({P}_{{\mbox{lee}}}\) or \({P}_{{\mbox{lhh}}}\), respectively.

Then we start the Monte Carlo simulation. In each cycle, we generate a random probability and compare it with the probabilities calculated above to determine whether a charge is injected or not. We then count the electron and hole population and go back to calculate the number of injected charges. And then we generate a random probability and compare it with the migration probabilities to determine whether a charge is migrated or not. A full cycle is considered as a unit time, and the carrier numbers and exciton generation rates are recorded after each cycle.

Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin quantum tunneling model

To clarify this point, we further analyzed the diffusion of carriers through shell barriers to adjacent QDs using the WKB quantum tunneling model. The tunneling probability is determined by the effective mass of the carriers and the barrier profile. The expression for this relationship can be formulated as follows:

Where \({m}_{{\mbox{e}}/{\mbox{h}}}^{*}\) is the effective mass of electrons or holes, \(\Delta E(x)\) represents the energy barrier to overcome, and ћ is Planck’s constant. It can be inferred that the tunneling probability is jointly determined by the effective mass of the carriers and the potential barrier. For L/T-QDs with a typical structure as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 9a, and effective masses of 0.13 m0 for electron and 0.45 m0 for hole, substituting these parameters into Eq. (7) allows for the adjustment of the ZnS shell thickness to calculate the tunneling probabilities of electrons and holes (Supplementary Fig. 9b).

Coulomb interaction force simulations

The mean driving force of lateral carrier diffusion is attributed to the Coulomb interactions. Therefore, we calculated the electric field force and the Coulomb interaction force using the formulas as follows:

Where the FE and FC are the electric field and the Coulomb interaction forces, respectively. e is the electron/hole charge, V is the driving voltage. l and d are the thickness of devices and the distance between adjacent QDs, respectively.

Data availability

The data generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29307188)39. More detailed data can be obtained upon request from the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Shirasaki, Y., Supran, G. J., Bawendi, M. G. & Bulović, V. Emergence of colloidal quantum-dot light-emitting technologies. Nat. Photon. 7, 13–23 (2012).

Mashford, B. S. et al. High-efficiency quantum-dot light-emitting devices with enhanced charge injection. Nat. Photon. 7, 407–412 (2013).

Shen, H. B. et al. Visible quantum dot light-emitting diodes with simultaneous high brightness and afficiency. Nat. Photon. 13, 192–197 (2019).

Kim, T. et al. Efficient and stable blue quantum dot light-emitting diode. Nature 586, 385–389 (2020).

Deng, Y. Z. et al. Solution-processed green and blue quantum-dot light-emitting diodes with eliminated charge leakage. Nat. Photon. 16, 505–511 (2022).

Gao, Y. et al. Minimizing heat generation in quantum dot light-emitting diodes by increasing quasi-fermi-level splitting. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1168–1174 (2023).

Bian, Y. Y. et al. Efficient green InP-based QD-LED by controlling electron injection and leakage. Nature 635, 854–859 (2024).

Li, M. Q. et al. Ultrabright and stable top-emitting quantum-dot light-emitting diodes with negligible angular color shift. Nat. Commun. 15, 5161 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. Dipole–dipole-interaction-assisted self-assembly of quantum dots for highly efficient light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photon. 18, 186–191 (2024).

Zhang, W. J. et al. Stable and efficient pure blue quantum-dot LEDs enabled by inserting an anti-oxidation layer. Nat. Commun. 15, 783 (2024).

Li, X. Y. et al. Bright colloidal quantum dot light-emitting diodes enabled by efficient chlorination. Nat. Photon. 12, 159–164 (2018).

Yang, Z. W. et al. All-solution processed inverted green quantum dot light-emitting diodes with concurrent high efficiency and long lifetime. Mater. Horiz. 6, 2009–2015 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. Toward full-color electroluminescent quantum dot displays. Nano Lett. 21, 26–33 (2020).

Lee, T. et al. Bright and stable quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 34, 2106276 (2021).

Meng, T. T. et al. Ultrahigh-resolution quantum-dot light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photon. 16, 297–303 (2022).

Zhang, H., Chen, S. & Sun, X. W. Efficient red/green/blue tandem quantum-dot light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 21%. ACS Nano 12, 697–704 (2017).

Fan, J. et al. Recent progress of quantum dots light-emitting diodes: materials, device structures, and display applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2312948 (2024).

Kim, Y. H., Yoon, S. Y. & Yang, H. Blue-emissive ZnSeTe quantum dots and their electroluminescent devices. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 2142–2151 (2024).

Li, B. et al. Advances in understanding quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 1, 412–425 (2024).

Su, Q., Zhang, H. & Chen, S. Carrier dynamics in quantum dot light-emitting diodes: the conversion between electrons, excitons, and photons. Adv. Phys. Res. 4, 2400130 (2025).

Dai, X. L. et al. Solution-processed, high-performance light-emitting diodes based on quantum dots. Nature 515, 96–99 (2014).

Yang, Y. X. et al. High-efficiency light-emitting devices based on quantum dots with tailored nanostructures. Nat. Photon. 9, 259–266 (2015).

Chen, D. et al. Shelf-stable quantum-dot light-emitting diodes with high operational performance. Adv. Mater. 32, 2006178 (2020).

Luo, X. et al. Shelf-stable green and blue quantum dot light-emitting diodes with high efficiencies. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 6722–6727 (2024).

Zhu, X. T. et al. Doping bilayer hole-transport polymer strategy stabilizing solution-processed green quantum-dot light-emitting diodes. Sci. Adv. 10, eado0614 (2024).

Lee, K. H. et al. Highly efficient, color-pure, color-stable blue quantum dot light-emitting devices. ACS Nano 7, 7295–7302 (2013).

Lee, K. H. et al. Over 40 Cd/A efficient green quantum dot electroluminescent device comprising uniquely large-sized quantum dots. ACS Nano 8, 4893–4901 (2014).

Li, Z. et al. Efficient and long-life green light-emitting diodes comprising tridentate thiol capped quantum dots. Laser Photonics Rev. 11, 1600227 (2016).

Deng, Y. et al. Deciphering exciton-generation processes in quantum-dot electroluminescence. Nat. Commun. 11, 2309 (2020).

Peyvast, N., Shahid, H., Hogg, R. A. & Childs, D. T. D. Monte Carlo model incorporating many-body effects for determining the gain spectra of quantum dot lasers. Appl. Phys. Express 8, 122102 (2015).

Park, J.-H., Pristovsek, M., Amano, H. & Seong, T.-Y. Recent advances in micro-pixel light emitting diode technology. Appl. Phys. Rev. 11, 021319 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Quantum-dot light-emitting diodes for outdoor displays with high stability at high brightness. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 1901145 (2019).

Efros, A. L. et al. Band-edge exciton in quantum dots of semiconductors with a degenerate valence band: dark and bright exciton states. Phys. Rev. B 54, 4843 (1996).

Lee, E. M. Y., Tisdale, W. A. & Willard, A. P. Perspective: nonequilibrium dynamics of localized and delocalized excitons in colloidal quantum dot solids. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 36, 068501–068501 (2018).

Sheehan, T. J., Saris, S. & Tisdale, W. A. Exciton transport in perovskite materials. Adv. Mater. 37, 2415757 (2024).

Li, B. et al. Origin of the efficiency roll-off in quantum dot light-emitting diodes: an electrically excited transient absorption spectroscopy study. Nano Lett. 24, 10650–10655 (2024).

Sun, Y. Z. et al. Investigation on thermally induced efficiency roll-off: toward efficient and ultrabright quantum-dot light-emitting diodes. ACS Nano 13, 11433–11442 (2019).

Sadi, T., Radevici, I. & Oksanen, J. Thermophotonic cooling with light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photon. 14, 205–214 (2020).

Zhang, H. Source data for “Hole migration enables efficient and ultra-bright green quantum dot LEDs”. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29307188 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFE0205000, H.S.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U22A2072 (H.S.), 22205054 (L.W.), 61922028 (H.S.), 22479041 (Q.L.)), Zhongyuan High Level Talents Special Support Plan (244200510009, H.S.) and Science and Technology Innovation 2030- Major Project (2024ZD0604000, H.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z. and J.L. synthesized QDs, fabricated the QD-LEDs, and collected the data. X.W. and B.L. performed the EETA experiments and conducted the Monte Carlo model. Q.Y. and Q.L. analyzed the data. L.W., B.L., F.F., and H.S. conceived the idea, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. All authors commented and modified the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jeongkyun Roh, Ya-Kun Wang, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Li, J., Wang, L. et al. Hole migration enables efficient and ultra-bright green quantum dot LEDs. Nat Commun 16, 10143 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65135-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65135-x