Abstract

Edge computing requires real-time processing of high-throughput analog signals, posing a major challenge to conventional electronics. Although integrated photonics offers low-latency processing, it struggles to directly handle raw analog data. Here, we present a photonic edge intelligence chip (PEIC) that fuses multiple analog modalities—images, spectra, and radio-frequency signals—into broad optical spectra for single-fiber input. After transmission onto the chip, these spectral inputs are processed by an arrayed waveguide grating (AWG) that performs both spectral sensing and energy-efficient convolution (29 fJ/OP). A subsequent nonlinear activation layer and a fully connected layer form an end-to-end optical neural network, achieving on-chip inference with a measured response time of 1.33 ns. We demonstrate both supervised and unsupervised learning on three tasks: drug spectral recognition, image classification, and radar target classification. Our work paves the way for on-chip solutions that unify analog signal acquisition and optical computation for edge intelligence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decade, the rapid expansion of edge devices has generated an unprecedented demand for real-time analytics at resource-constrained edge nodes1. Applications ranging from machine vision in robotics2 to pharmaceutical diagnostics3,4,5, healthcare wearables6,7, and radar surveillance8,9 all rely on the rapid handling of high-throughput analog data, including images, spectra, and radio-frequency (RF) signals (Fig. 1a). Traditional digital approaches rely on sensors and analog-to-digital convertors (ADCs) followed by extensive electronic processing (Fig. 1b(i)). This scheme faces significant throughput and energy constraints10, making it costly for ultra-low-latency or battery-powered applications. As the scale and speed of edge data continue to rise11, there is a pressing demand for novel hardware paradigms to offer high-throughput, low-latency, and energy-efficient performance.

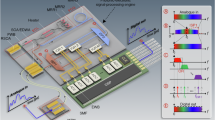

a Edge Applications: Various applications relying on the rapid processing of large-scale analog data, which involve processing images, spectra, and RF signals. b Existing solution for processing analog inputs from the edge, including: conventional digital systems, free-space optical systems, and integrated photonic systems. ADC analog-to-digital converter, DAC digital-to-analog converter. c Modal fusion and PEIC architecture. Modal fusion converts diverse analog input signals—images, spectral data, and RF signals—into broadband optical spectra, enabling high-throughput input via a single optical fiber. The PEIC integrates a sensing and convolution layer, followed by a nonlinear activation function (NAF) layer and a fully connected (FC) layer to form an end-to-end optical neural network. d Principal and performance metrics of the sensing and convolution layer. (i) and (ii) depict the compute density and energy consumption comparison of the AWG-based convolution engine against other photonic solutions. The compute density (TOPS/mm²) of the AWG is determined by the ratio of quadratic-scaling operations to an area that grows as a sum of linear (from the waveguide array) and quadratic (from the free-propagation regions) terms. This density initially increases with scale, as the linear area term from the large waveguide array is often the dominant factor for a significant range of N, before saturating towards a constant value for very large systems. The AWG minimizes energy consumption by using a linear number of devices to perform quadratic-order computing operations. This approach avoids the large cascading losses seen in traditional methods. The dashed line indicates the limited scalability of the MRR array due to the free spectral range (FSR) constraints. (iii) presents the workflow of sensing and the convolution layer. MZI Mach–Zehnder interferometers, MRR micro-ring resonator.

Free-space optical systems have been extensively explored for real-time analog image processing12,13,14,15. They employ large-scale spatial parallelism to accelerate computationally intensive tasks such as feature extraction and pattern recognition. By manipulating optical fields in free space, they can efficiently manage spatial data with minimal electronic overhead, enabling high-throughput image-based computations (Fig. 1b(ii)). However, these systems are often bulky, susceptible to environmental disturbances, and fundamentally limited to spatial inputs. As a result, they are impractical for compact edge devices and cannot seamlessly accommodate other analog data types, including spectral or RF signals, which are increasingly vital in diverse edge applications. By contrast, integrated photonic computing architectures promise a compact, robust, and energy-efficient alternative16,17,18,19,20,21,22 through the monolithic integration of optical and electronic components on semiconductor chips23,24. This scheme yields enhanced compactness, reduced latency, and greater environmental stability than free-space platforms.

Despite these advantages, incorporating raw analog signals into waveguide-based integrated photonic circuits typically demands extensive electronic preprocessing. In many cases, data must first be digitized and manipulated in the electrical domain, then re-encoded via on-chip modulators25,26, as shown in Fig. 1b(iii)—a process that executes multiple analog-to-digital and electro-optic conversions, undermining the inherent energy and bandwidth advantages of photonic chips. Some research has attempted to bypass this challenge by directly processing analog signals within photonic chips. For instance, monochromatic illumination and two-dimensional grating coupler arrays have been used to capture free-space images directly into the chip, thus eliminating the need for full electronic preprocessing27. Nevertheless, this method is limited by the planar nature of photonic circuits: unlike free-space propagation, which supports two-dimensional image encoding with an independent propagation axis, planar waveguides, after defining the propagation direction, leave only one degree of freedom for signal routing, making it difficult to handle 2D image data. As a result, attempts to scale to larger spatial inputs encounter significant cross-talk and routing limitations. Similarly, while integrated photonic devices capable of modulating RF signals at high bandwidths show promise28, time-domain processing of these signals remains difficult. This typically requires bulky optical delay lines to manage temporal information28,29,30, which compromises the compactness and scalability that integrated photonics aim to provide.

To address the aforementioned challenges, we propose a solution that integrates analog modal fusion with a photonic edge intelligence chip (PEIC) to create an end-to-end optical neural network as presented in Fig. 1c. The modal fusion component converts all input data types into broad optical spectra. Specifically, image data is encoded using scattering media, which can be viewed as the inverse process of a speckle spectrometer. RF signals are modulated onto light via a phase modulator, mapping high-speed time-domain information to the optical spectrum by generating sidebands around the carrier frequency. Spectral inputs are directly transmitted onto the chip without additional conversion. By converting these various signal types into unified optical spectra, the high-frequency nature of optical signals (193.5 THz at 1550 nm) provides vast bandwidth and ultra-high throughput31. This physical property of the spectrum facilitates parallel transmission of large amounts of data and the unification of different analog signals into a single optical fiber for high-throughput input.

Once the spectral inputs are transmitted onto the chip, they first pass through the sensing and convolution layer, which is mainly composed of an arrayed waveguide grating (AWG), as shown in Fig. 1d. The inherent properties of the AWG enable it to perform spectral sensing effectively32,33,34. Moreover, as we previously proposed and demonstrated, the unique routing capabilities of the AWG allow it to function as a redundancy-free optical convolution engine35, surpassing all other on-chip optical convolution schemes in performance21,27,30,36,37,38,39,40. The convolution process using the AWG is illustrated in Fig. 1d(iii). The original optical spectrum is first fanned out before entering the AWG, where Mach–Zehnder interferometers (MZIs) impose the kernel weights. Each MZI output is then directed to one of the multiple AWG input ports, encoding different segments of the weighted optical spectrum. From these input ports, the AWG’s unique routing functionality directs the signals to specific output ports, where they are fanned-in losslessly. This scheme ensures that the same convolution kernel can be applied to multiple segments of the input spectrum without redundant resource usage, thereby maximizing computational efficiency while minimizing the total number of required devices (more information could be found in Supplementary Note 1). By utilizing linear quantities of devices, this approach can perform quadratic orders of computing operations while avoiding the large-scale cascading losses typically encountered in other traditional schemes. As presented in Fig. 1d(i), (ii), the convolution scheme based on the AWG offers superior compute density and energy efficiency compared to other solutions (detailed calculations can be found in Supplementary Note 2). The advantages become even more pronounced as the system scale increases.

Following the sensing and convolution layer, a subsequent nonlinear activation function (NAF) layer and fully connected (FC) layer complete the end-to-end optical neural network, enabling on-chip inference with a measured response time of 1.33 nanoseconds (ns). This optical neural network architecture supports both supervised and unsupervised learning across a range of tasks. These tasks involve different signal modalities: drug spectral recognition uses spectral inputs, image classification processes spatial (image) inputs, and radar target classification works with RF signals. These examples highlight the PEIC’s capability to efficiently handle multi-modal analog data, showcasing its practicality in addressing a wide range of edge computing challenges.

As shown in Table 1, we compare the PEIC’s performance with state-of-the-art end-to-end photonic neural network chips. A key metric we introduce is the “Interface bandwidth per channel for analog optical input” (Table 1), which must be carefully distinguished from the network’s overall operational speed. This metric quantifies the efficiency of delivering raw analog data onto the chip. The ability to handle such data efficiently represents a critical bottleneck for edge intelligence hardware, particularly given the scarcity and high cost of high-speed electrical I/O ports and optical fiber interfaces on integrated photonic chips. Furthermore, it addresses the challenge of directly inputting raw analog signals from sensing front-ends onto the chip via optical fiber. While our modal fusion achieves a THz-scale input bandwidth through a single optical port, the end-to-end operational rate of our current proof-of-concept system is limited to the ~100 MHz range by the nanosecond response time of the NAF. This is a common limitation for contemporary end-to-end photonic platforms, where nonlinearities are realized through photodiode-driven micro-ring modulators leveraging the carrier injection effect25,26,27,41. Our contribution lies in demonstrating an input architecture that decouples the per-port analog input bandwidth from the system’s repetition rate. This approach overcomes a fundamental limitation of conventional electronic encoding schemes, which require a large array of power-hungry electrical I/O channels to achieve high aggregate bandwidth, and represents a crucial step towards future, faster all-optical processors.

The PEIC delivers superior energy efficiency and input bandwidth, positioning it as an ideal candidate for real-time, energy-efficient processing at the edge. Our work lays the foundation for next-generation edge intelligence systems by integrating multi-modal analog signal acquisition and processing on a single photonic chip. Our scheme has the potential to drive advancements in fields such as autonomous systems, robotics, wearable healthcare, and environmental monitoring, where high-throughput, low-latency processing is critical for real-time decision-making.

Results

Building blocks of PEIC

We implemented the PEIC using the commercial foundry process. Figure 2a shows a microphotograph of the PEIC, highlighting the monolithic integration of all required subsystems, including the sensing and convolution layer, the NAF layer, and the FC layer. The final classification result is determined by identifying which of the chip’s physical output ports receives the maximum optical power, with no subsequent digital post-processing. Detailed information on the chip fabrication process is provided in the “Methods.” As shown in Fig. 2b, we use a custom photonic packaging that integrates three fiber arrays for input, output, and monitoring. The electrical interfaces connect to the chip through wire bonding, linking the chip devices to a printed circuit board for control.

a Microphotograph of the fabricated PEIC. b Packaging of the PEIC. c The fabricated MZI for kernel loading. d Microphotograph of the AWG. e Transmission spectrum of the AWG. f Computing accuracy measurement with 2000 random inputs and kernels. g The fabricated NAF unit. h The diagram and measured output response of the NAF unit. i Response time measurement of the NAF unit. j The fabricated MZI mesh for the FC layer. k Transmission curve for tuning the phase shifter of the MZI. l The histogram illustrates the measured fidelity for 1000 randomly selected real-valued matrices.

Figure 2c–f shows the characterization results of the sensing and convolution layer. Figure 2c presents a microphotograph of the MZI used for convolution kernel loading. The MZI is designed with wide waveguides and inverse-designed multi-mode interference structures42 to minimize the effect of fabrication errors and ensure broad spectral response. Since the convolution process only requires intensity modulation, phase shifters are placed solely on the upper MZI arms, with thermal isolation between the upper and lower arms to prevent thermal cross-talk. Figure 2d shows a microphotograph of the AWG used in the sensing and convolution layer. It overlaps the input and output star couplers to reduce the device footprint, resulting in a size of 1.5 × 1.5 mm. The device contains 185 arrayed waveguides, with an adjacent waveguide length difference of 19.394 μm, corresponding to a grating order of m = 35. Figure 2e displays the transmission spectrum of the AWG, which includes 16 spectral channels, each with a 100 GHz channel spacing. The measured insertion loss is approximately 3.66 dB. Figure 2f shows the convolution precision test performed on the AWG-based convolution layer. The experiment used 2000 random input signals and convolution kernels, with results showing a standard deviation of 0.94%, corresponding to 6.73 bits of precision according to ref. 43.

Figure 2g shows a microphotograph of the fabricated NAF unit, which consists of an integrated photodetector (PD) and a micro-ring modulator (MRM). The PD is electrically connected to the MRM, forming the core structure of the NAF unit. Figure 2h illustrates its operational diagram. When an optical input is applied, the PD generates a photocurrent, which changes the refractive index of the micro-ring modulator via carrier injection. The output signal from the NAF unit is a nonlinear function of the input light, determined by the electro-optic transfer function of the MRM41. As shown in Fig. 2h, the NAF unit begins to exhibit nonlinear behavior beyond approximately 20 µW of input optical power. Figure 2i presents the time-domain response of the NAF unit, characterized by a pump-probe experimental setup. The pump signal (magenta curve) is generated by a 10 GHz intensity modulator and a bit pattern generator, while the probe signal (blue curve) represents the response of the output of the NAF unit. The time traces are captured using a high-speed photodiode and oscilloscope. Detailed information on the experimental setup can be found in Supplementary Note 3. The full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) difference between the pump and probe signals is 1.33 ns, which we take as the response time of the NAF unit.

Figure 2j shows the microphotograph of our optical FC layer, which adopts the incoherent real-valued matrix scheme we previously proposed44. In this design, any N × N real-valued matrix can be implemented using N2 phase shifters with an optical depth of N + 1, effectively halving both the optical depth and the number of phase shifters required by the conventional coherent MZI mesh (details in Supplementary Note 4). To ensure consistency across the chip, each individual MZI in the FC layer uses the same design as the MZI for convolution kernel loading. Figure 2k illustrates the transmission curve of a single MZI in the FC layer as a function of the voltage applied to the phase shifter. We evaluated the performance of this scheme by randomly selecting 1000 real-valued matrices and measuring their optical implementations on chip. As shown in Fig. 2l, the average correlation coefficient between the measured matrices and the target matrices reaches 0.9949, reflecting a high degree of fidelity in reproducing arbitrary real-valued connections.

PEIC for spectral recognition

Efficient spectral recognition is crucial for a range of edge applications, including pharmaceutical quality control, chemical analysis, and environmental monitoring. However, conventional methods depend on bench-top spectrometers coupled with digital processors, making them impractical for real-time, on-site deployment. By integrating sensing and computation on a single chip, photonic solutions promise a compact, low-power platform for rapidly analyzing spectra at the edge. To verify the schematic of the PEIC, we conducted the experimental setup shown in Fig. 3a. We employed an amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) source followed by a programmable waveshaper to encode spectral samples derived from a public dataset5. In total, 120 samples were included in the dataset, each corresponding to one of four tablet types (A, B, C, and D). The waveshaper precisely modulates the ASE output so that the shaped spectra accurately replicate the reference profiles provided by the dataset. After wave-shaping, the light was amplified by an erbium-doped fiber amplifier (EDFA) to ensure sufficient optical power before coupling it into the PEIC. Once inside the PEIC, the spectra are processed by an end-to-end photonic neural network chip for classification.

a Experimental setup: An amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) source is shaped by a waveshaper into four tablet types (A, B, C, D) derived from a public dataset. The shaped spectra are amplified by an erbium-doped fiber amplifier (EDFA) and then coupled into the PEIC for classification. b (i) Example input spectra for the four tablet types. (ii) Corresponding spectral sampling results after the AWG, where each channel captures a portion of the spectrum for parallel processing. c Neural network architecture and in situ learning methods on the PEIC. (i) The neural network diagram of the PEIC. (ii) In situ supervised learning uses labeled data to update on-chip tunable devices via gradient descent. (iii) Fine-tuning with unlabeled data aligns the hardware output distribution with a reference model through a local loss function, mitigating process variations and device nonuniformities without requiring labels. d Training curves over 200 epochs and the corresponding confusion matrix. e Comparison of confusion matrices without (left) and with (right) the hardware fine-tuning procedure. After fine-tuning, the accuracy increases from 75% to 97.5%.

The AWG carries out spectral sampling to extract the relevant information (sensing), and then leverages its unique cyclic routing property to realize the convolution step in the sensing–convolution layer. Examples of the samples from the dataset and their corresponding spectral sampling results are shown in Fig. 3b(i), (ii), respectively.

Figure 3c(i) presents the network diagram. The AWG in our design provides 16 channels, corresponding to a neural network input dimension of 16. The inputs (4 × 4) are fed into a convolution layer with a 3 × 3 kernel (details on the 2D convolution can be found in Supplementary Note 1). The resulting 2 × 2 output feature map is flattened before entering an FC layer, which translates these extracted features into final classification outputs for the four target categories. To mitigate the impact of fabrication-induced variations in the deployed PEIC, we implement an in situ supervised learning procedure directly on the chip (Fig. 3c(ii)). In situ training refers to optimizing parameters directly within the physical hardware (with the help of a digital computer), distinguishing it from in silico training, where a digital model is trained offline and its parameters are subsequently transferred to the hardware. Specifically, we use the final classification loss—namely the mean cross-entropy—to iteratively adjust tunable on-chip devices via a gradient descent algorithm (details in Supplementary Note 5). This scheme enables the PEIC to converge efficiently and maintain high accuracy. In future implementations, calculating partial gradients in parallel26,45,46,47 could further accelerate this training process and reduce the hardware burden on the training circuits.

Moreover, unlabeled data are especially relevant for edge deployment. Once the PEIC is operating at the edge and begins processing raw analog signals in real time, ground-truth labels are often unavailable. To address this scenario, we propose a fine-tuning technique that compensates for fabrication imperfections without requiring labeled samples (Fig. 3c(iii)). We initialize the on-chip parameters using the in silico training model. We then fine-tune the actual hardware deployment by minimizing the local loss function at each network layer (as follows):

Where \({{{\rm{\alpha }}}}\) is the scaling hyperparameter that balances the two loss components. The first term, Lcorr,i, ensures that the physical operation of the on-chip hardware correctly mimics the target mathematical operator. The second term, Ldiv,i, aims to align the statistical output distribution of the physical layer with that of the ideal in silico model. This alignment is particularly crucial as Ldiv,i, implicitly incorporates the effects of the on-chip NAF. The inclusion of α is vital to prevent the distribution alignment from causing severe deviations from the original model’s intended operation. The first term Lcorr,i is given by \({L}_{{corr},i}=1\,-\,{{Corr}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}\), where \({{Corr}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}\) is the correlation between the ith layer’s linear operator and the target operator. Inspired by the concept of distribution alignment in unsupervised learning48, the second term Ldiv,i uses the Jensen–Shannon divergence to align the output distribution of the ith layer in actual hardware (Qi) with that of the reference in silico model (Pi):

Where Mi = (Pi + Qi)/2 is the midpoint distribution and DKL denotes the Kullback–Leibler divergence, defined by: \({D}_{{KL}}(P{{{\rm{||}}}}Q)={\sum }_{x}P(x)\log (\frac{P(x)}{Q(x)})\). By iteratively minimizing Li at each layer, the PEIC could adjust its hardware parameters for consistent performance without labeled training data. This fine-tuning method ensures that the network output remains aligned with the intended model behavior, enhancing reliability and accuracy when facing unlabeled, real-world signals at the edge. Its unsupervised approach makes it well-suited for edge applications, where labeled data may be unavailable and the system must adapt to manufacturing variations without supervision.

Figure 3d presents the in situ supervised learning results. It shows the training curves (loss versus epoch and the corresponding accuracy) and the confusion matrix for the four-class spectral classification task over 200 epochs, demonstrating that our PEIC achieves an accuracy of 98.3% with in situ supervised learning. Figure 3e displays the results of unsupervised fine-tuning. It compares the confusion matrices obtained without and with the fine-tuning process. Without fine-tuning, the parameters that were trained in silico are directly deployed in the PEIC. However, due to factors such as fabrication errors, this leads to a classification accuracy of 75%. In contrast, the unsupervised fine-tuning method, performed in situ on the PEIC, adjusts the on-chip parameters without requiring knowledge of the specific input signal labels. This fine-tuning improves the overall accuracy to 97.5%, effectively compensating for the manufacturing discrepancies and ensuring better alignment with the desired in silico model behavior.

PEIC for vision task

Real-time processing of visual data at the edge is essential for applications spanning from autonomous navigation to wearable health monitoring. While traditional edge devices rely heavily on digital processors and sensors, they often struggle with performance limitations in terms of throughput and power efficiency. To address these limitations, we demonstrate the application of the PEIC for image classification tasks, which utilizes spatial-to-spectral mapping to enable high-throughput, low-latency, on-chip visual data processing, providing an efficient solution for edge-based image classification tasks. As shown in Fig. 4a, the experimental setup begins with broadband illumination generated by an ASE source and shaped by a waveshaper. The light is directed toward an object, which is encoded by a spatial light modulator (SLM) to represent the object’s image. The light then passes through a 4f relay system to relay the spatial light field to the random scattering chip. At the random scattering chip, the spatial image information is converted into spectral data, which is then transmitted through a fiber. The spectrally encoded light is passed through an EDFA to ensure sufficient optical power before entering the PEIC. The PEIC processes the spectral data and outputs the classification results.

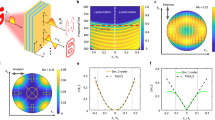

a Experimental setup for image classification using the PEIC. b Structure and microscope image of the random scattering chip, which features waveguides etched with random duty cycle gratings. The chip utilizes multi-stage scattering and coupling to convert spatial image data into unique spectral signatures. c Measured optical intensity distributions of the random scattering chip at two input wavelengths (1542 nm and 1543 nm), highlighting the differences in the resulting speckle patterns. d Measured average normalized spectral correlation function of the scattering chip. e Schematic of the spatial-to-spectral mapping process, where the spatial distribution of light is transformed into spectral signatures. f Example of spatial inputs and the corresponding spectral samples after processing through the random scattering chip and subsequent AWG sampling. g Training curves of the vision task and the corresponding confusion matrix. h Comparison of confusion matrices for the image classification task, with (right) and without (left) the unsupervised hardware fine-tuning procedure.

Figure 4b illustrates the structure of the random scattering chip, which consists of 64 waveguides arranged side-by-side along the x-axis. The waveguides are etched with gratings that have random duty cycles. The light entering this array undergoes continuous scattering and coupling within the waveguides, ultimately combining at the output. The spatial distribution of the incident light affects the combined spectral output, thus enabling spatial-to-spectral mapping. Along the y-axis, the chip is divided into five alternating regions of grating regions and coupling regions. The grating regions receive the incoming spatial optical field and generate random scattering. The coupling regions introduce additional optical path diversity for the scattered light, achieved through cross-talk between waveguides. This multi-stage scattering and coupling process ensures that the device can effectively translate the spatial profile of the input beam into a unique spectral response. Further details are provided in “Methods” and Supplementary Note 6.

We first tested the spectral-to-spatial mapping features of the fabricated random scattering chip to get its quantitative properties. Details regarding the experimental setup for characterizing the random scattering chip can be found in Supplementary Note 6. Figure 4c shows the speckle patterns obtained at 1542 nm and 1543 nm, respectively, using a tunable laser source. The distinct difference between the two speckles demonstrates the feasibility of the mapping process. To evaluate the device’s spectral resolution, we measured the average normalized spectral correlation function, yielding a FWHM of 576 pm (Fig. 4d). For spectral-to-spatial mapping, this indicates that when the wavelength shifts by more than 576 pm, the speckle pattern undergoes a noticeable change. For spatial-to-spectral mapping, this implies that a spectral sampling interval larger than 576 pm can effectively capture the spatial distribution of the input light. Since our AWG employs a 0.8 nm spectral sampling spacing, it satisfies this requirement and ensures mapping performance. Instead of relying on wavelength changes to generate different scattering patterns49,50, we employ the inverse process of the conventional speckle spectrometer, as described in Fig. 4e. Using the random scattering chip, we convert the spatial information of an image, o(x), into a unique set of spectral signatures, S(λ). This inversion can be mathematically represented by:

where A(λ,x) is the transmittance matrix, which characterizes the interaction between light and the chip’s scattering medium. This inversion is crucial for high-throughput, on-chip image classification, enabling the PEIC to process incoming visual data in the spectral domain. As an example, Fig. 4f demonstrates how several sample images from the MNIST dataset are transformed into their corresponding spectral signatures after passing through the chip and subsequent AWG sampling.

The vision-task results are summarized in Fig. 4g, h. For the drug spectral recognition and radar target classification tasks, the entire datasets were used. For the vision task, due to the large size of the full MNIST dataset, a randomly selected subsample was used for our proof-of-concept demonstration. This demonstration consists of 640 samples for the training set and 320 samples for the testing set. As shown in Fig. 4g, the in situ supervised training phase converges to a classification accuracy of 83.75%. This 83.75% accuracy for the MNIST task is currently lower than what is achievable with digital full-precision models having the same parameter count and network architecture, which typically reach around 90% accuracy (see Supplementary Note 7 for details). Figure 4h compares the confusion matrices for the classification task, with and without unsupervised fine-tuning. Without fine-tuning, the PEIC achieves a classification accuracy of 39.375%. After applying the fine-tuning method, the accuracy improves to 75.625%.

PEIC for radar classification

Radar classification is a cornerstone of many edge applications, including autonomous navigation and security systems, where rapid object detection is critical. Conventional radar systems rely on digital signal processing techniques that introduce significant latency and power consumption. These issues are magnified when processing high-speed radar signals for real-time applications, exacerbating the strain on the limited energy budgets of edge devices. Our PEIC addresses these challenges by converting radar signals into optical spectra and processing them in the optical domain. It exploits the ultra-high bandwidth and inherent parallelism of integrated photonic systems. To evaluate the PEIC’s capability for radar classification, we adopt a radar detection scheme featuring two transmit antennas (TA1 and TA2) and one receive antenna (RA), as illustrated in Fig. 5a. The time-domain waveforms at the RA vary with the object’s geometry and position. Using a geometric optics (GO) method, these temporal waveforms are computed to capture the reflection characteristics of different shapes. This method approximates each object as a set of reflecting surfaces, yielding distinct time delays and amplitudes in the received signals. Further details of the GO method can be found in “Methods” and Supplementary Note 7. Following this modeling, the receiver signals S(t) are applied to modulate the phase of an optical carrier at frequency \({\omega }_{0}\). The temporal output field is: \({E}_{{out}}\,=\,{E}_{0}\cos ({\omega }_{0}t+\beta {S}(t))\), where \(\beta\) is the modulation depth. In the frequency domain, the radar signal S(t) gives rise to a series of sidebands around \({{{{\rm{\omega }}}}}_{0}\), with amplitudes governed by the Bessel functions. The frequency response can be represented as:

Where Ω characterizes the main frequency components of S(t), and the integral \({\int }_{0}^{T}\beta {S}({t}^{\prime} ){dt}^{\prime}\) captures the accumulated phase modulation over one observation period T. This expression shows how the time-varying radar signal S(t) is translated into frequency components, enabling the PEIC to perform radar classification by processing these modulated optical spectra.

a Schematic of the experimental setup. It illustrates the radar detection system, where microwave signals are transmitted and reflected by various objects (square, cross, circle, plus). The reflected signals are received and converted into optical spectra via an electro-optic phase modulator. The multi-wavelength laser is used to generate discrete optical lines across a broad spectral range, enabling precise sampling of the radar-modulated optical signal. The PEIC processes these signals for radar classification. b (i) Different objects (square, cross, circle, plus) used to demonstrate radar detection. b (ii) Time-domain waveforms at the receiver, computed via the geometric optics (GO) method, showing distinct signal patterns for each object. b (iii) Experimentally measured spectral responses of the radar-modulated optical signal, revealing each object’s unique spectral signature. c In situ supervised training curves for radar classification, reaching 83.4% accuracy. d Confusion matrices comparing classification results with and without fine-tuning. Accuracy improves from 28.1% to 76.9% through unsupervised fine-tuning.

Next, the optical signal undergoes sampling for spectral analysis. Ideally, the frequency response of the optical carrier could be directly sampled spectrally. However, due to experimental limitations, additional modifications are required. The spectral channel spacing of the AWG and the sampling rate of the arbitrary waveform generator impose constraints on the available frequency range. The direct use of the AWG for spectral sampling of the optical signal is limited by these factors, as a single optical carrier’s frequency spectrum cannot be extended beyond a certain bandwidth. To overcome this limitation, a multi-wavelength laser is used as the input source. It generates multiple discrete optical lines across a broad spectral range, providing a method to offset-sample the radar-modulated optical signal. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, the optical signal is sampled at different spectral intervals corresponding to the positions of these laser lines. This results in displaced sampling across the optical spectrum, effectively enabling a wider spectral range to be sampled despite the hardware limitations. While this technique successfully addresses the challenges in the current experimental setup, it imposes certain limitations on the sampling efficiency for future applications. These constraints and potential improvements will be discussed in the Discussion section.

Figure 5b(i) shows a schematic for radar detection, where different objects (square, cross, circle, and plus) are detected by the radar system. The objects reflect the transmitted radar signal, and the receiver detects variations in the waveform based on their geometry and position. Figure 5b(ii) presents the temporal responses for each object. These waveforms, simulated using the GO method, vary in intensity and pattern based on the object’s shape, reflecting distinct radar signatures. Figure 5b(iii) illustrates the experimentally measured spectral response corresponding to the temporal signals. The radar-modulated optical signal produces unique spectral profiles for each object, with shifts centered around the carrier wavelength, revealing the object’s characteristics in the optical domain.

Figure 5c shows the in situ supervised training curves for radar classification, with loss (orange) and accuracy (blue) plotted over epochs. The accuracy reaches 83.4% after training. Figure 5d presents confusion matrices comparing performance with and without fine-tuning. Without fine-tuning, the accuracy is 28.1%, while with unsupervised fine-tuning, the accuracy improves to 76.9%.

Discussion

Scalability of PEIC

The scalability of the PEIC is one of its core strengths, allowing it to handle increasingly complex tasks at the edge. Central to this scalability is the AWG-based convolution engine, which offers high energy efficiency and computational density. Unlike traditional optical computing methods that rely on cascaded devices, the AWG’s unique routing capabilities enable it to perform a quadratic number of convolution operations with a linear number of devices and avoid the cascading losses typically encountered in conventional systems.

The scalability of PEIC can be enhanced by increasing the scale of the AWG. Currently, the scale of AWG can reach 512 channels51, achieving a throughput of 12.8 THz per input port. Such an expansion optimizes performance and enables real-time, high-throughput edge computing applications. Additionally, when used for convolution operations, a 512-channel AWG can achieve an energy efficiency as low as 4.6 femtojoules per operation (fJ/OP), enabling more parallel processing and increasing the system’s capacity to handle complex, multi-modal data without significantly increasing energy consumption.

Beyond the scaling of AWG, expanding PEIC’s neural network architecture provides another significant avenue for growth. By integrating multiple AWG convolution engines, PEIC can support a monolithic end-to-end photonic neural network with numerous convolutional layers, which enhance the ability to extract increasingly complex features at different levels of abstraction. This hierarchical processing enables PEIC to learn complex representations of data, improving its capacity to perform advanced tasks like real-time decision-making in autonomous systems. The implementation of multiple convolutional layers can be facilitated through the addition of on-chip pooling and more scalable NAFs, as outlined in Supplementary Note 8. Furthermore, to enhance integration density, the AWG can be fabricated using silicon nitride, which offers superior performance in photonic applications. The adoption of multi-layer silicon nitride technology enables the 3D stacking of a series of convolutional layers, which further increases integration density and expands PEIC’s capability.

Seamless integration of visual and radar sensing with PEIC

One promising direction for vision tasks with PEIC is the use of multi-mode fiber for spatial-to-spectral mapping. Multi-mode fibers inherently exhibit frequency-dependent propagation, where different guided modes travel at different speeds. It enables the encoding of spatial information into the spectral domain with significantly lower loss and higher spectral resolution, reaching the femtometer and even attometer levels52,53. This approach is particularly beneficial for fiber-based endoscopic sensing applications54, where a single fiber can serve as an ultra-thin imaging probe. The spatial information captured through the fiber is directly converted into spectral signatures that PEIC can process, enabling ultra-low-latency, low-power computation at the edge.

In addition to the advancements in visual sensing, future radar integration with PEIC will also benefit from higher-density AWGs with reduced channel spacing. State-of-the-art AWGs have achieved spectral channel spacings as low as 1 GHz55, which allows for finer spectral resolution of incoming radar signals. Furthermore, the broad spectral processing capability of PEIC makes it well-suited for integration with emerging THz radar systems56,57,58. The extended bandwidth of THz radar signals can be efficiently processed within PEIC’s optical computing framework. Another potential enhancement is the use of an on-chip time-lens59 for frequency-domain stretching of radar signals before they enter PEIC. This will align the radar signal’s spectrum with the AWG’s spectral sampling interval, enhancing sensing efficiency and classification performance. These techniques together enable PEIC to fully leverage wider spectral bandwidths for radar processing with greater parallelism and efficiency.

To address the path towards a practical, fully integrated system, it is important to distinguish between the core PEIC architecture and the laboratory equipment used to validate it. In this proof-of-concept demonstration, components such as the ASE source, waveshaper, and SLM served as part of the testing apparatus to emulate a wide variety of real-world analog signals (e.g., the SLM simulates an image input, while the ASE and waveshaper simulate a spectral input). In a deployed edge scenario, the PEIC would directly receive raw analog signals from the sensing front-end, meaning these emulation components would not be part of the system’s final footprint.

Furthermore, for practical edge deployment, the PEIC must be able to process potentially weak analog signals from the environment, which often necessitates optical pre-amplification. While our current demonstration uses an external EDFA, a clear pathway exists for full integration. Future implementations can be deployed by endowing silicon nitride (Si₃N₄) photonic integrated circuits with erbium-based gain60. This would enable the realization of compact and efficient on-chip optical amplifiers, eliminating the need for bulky external components. Such integration, along with the peripheral circuits for static control and calibration43,61, would represent a crucial step towards fully monolithic photonic edge intelligence.

In summary, the fusion of diverse analog inputs into broad optical spectra unlocks the exceptional parallelism of optical signals. It enables efficient, high-throughput photonic computing with a single optical fiber for raw analog data input. Combined with the AWG-based convolution engine, this fusion approach facilitates seamless, energy-efficient real-time processing of multi-modal data streams from the edge. As AWG channels scale and advanced architectures are integrated, these innovations will redefine performance limits, paving the way for compact, energy-efficient edge intelligence solutions. Our work in photonic computing lays the foundation for next-generation edge intelligence applications, offering transformative potential in fields such as autonomous systems, healthcare monitoring, and environmental sensing, where rapid, adaptive decision-making is critical for real-time operations.

Methods

Dataset

The dataset of tablet spectra and MNIST handwritten digits was respectively taken from https://ucphchemometrics.com/tablet/ and https://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/.

Chip fabrication

The photonic integrated circuits were fabricated on a 200 mm silicon-on-insulator (SOI) platform. The starting wafers feature a 220 nm-thick top silicon device layer over a 2 µm buried oxide (BOX). Waveguides were formed through a series of lithographic and etching steps, allowing both fully etched and partially etched silicon regions for strip or rib geometries as needed. Multiple ion-implantation steps introduced p–n doping profiles (including contact regions) for modulators, photodiodes, and other active devices. Germanium epitaxy was performed to create on-chip photodiodes. Localized thin-film heaters were added for thermal-phase tuning, followed by tungsten contacts and two levels of copper interconnect for electrical routing.

Arrayed waveguide grating design

The AWG is based on a commercial SOI wafer with a 220 nm top silicon thickness and SiO2 top cladding. It has a channel spacing of 100 GHz (i.e., 0.8 nm) and a free spectral range of 34.246 nm. Both the arrayed waveguides and free-propagation region (FPR) are silicon ridge waveguides with an etch depth of 70 nm to reduce phase errors and sidewall scattering loss in the arrayed waveguides. The AWG has 12 input channels and 27 output channels. The input and output star couplers are overlapped to make the device more compact, with a size of 1.5 × 1.5 mm. There are 185 arrayed waveguides, each consisting of a bent waveguide and a straight waveguide. The straight waveguide width is 1.2 μm, the bent waveguide width is 800 nm, and the bent radius is between 47 and 53 μm. Tapers are used between the straight and bent waveguides. The star coupler radius is 353.877 μm. The adjacent arrayed waveguide length difference is 19.394 μm, corresponding to a grating order m = 35. The waveguide spacing is 3 μm, both on the input/output star coupler circumference and on the AWG circumference. To reduce coupling loss between the arrayed waveguides and FPR, the arrayed waveguide width on the grating circumference is expanded to 2.8 μm. The input and output waveguides on the star coupler circumference have a width of 1.5 μm.

Experimental setup

An ASE source (Amonics ALS-CL−15) serves as the broadband light source, with its output shaped by a programmable waveshaper (Finisar WaveShaper 1000S). The light is amplified by the EDFA (GF-PA-45-09-1-1-B) before coupling into the PEIC. The PEIC is controlled by a custom field-programmable gate array (FPGA) based framework. DAC modules (LTC2688) supply voltage outputs from 0 to 10 V with 16-bit resolution across 96 channels, under the control of an Xilinx 7K325T FPGA chip. These voltages are used to load the network weights in the PEIC during both inference and in situ training. For the image classification experiment, a 4f optical system relays the image from an SLM (Holoeye PLUTO-2.1, 1920 × 1280 pixels with an 8 µm pixel pitch) onto a random scattering chip. The first lens in the 4f system has a focal length of 100 mm, while the second lens has a focal length of 25 mm. In the radar classification experiment, a multi-wavelength laser source (IDPHOTONICS CoBrite-DX) generates discrete optical lines. An arbitrary waveform generator (Keysight M8195A), followed by an electrical amplifier (GT-LNA-47GHz), produces the time-domain radar signals. These signals drive an electro-optic phase modulator (EOSPACE PMP-SHJ911) to encode the radar waveforms onto the optical carriers.

Random scattering chip design

The chip is composed of 64 parallel waveguides arranged side-by-side along the x-axis. To minimize combining losses, eight waveguides (evenly spaced among the 64) are specifically dedicated to gathering the scattered optical signals at their top and bottom ends, whereas the remaining waveguides terminate with distributed Bragg reflectors to extend their effective optical path length. Along the y-axis, the chip alternates between grating regions and coupling regions. Each grating region is 2 µm wide, with a grating period of 0.58 µm, a duty cycle in the range of 0.45 to 0.55, and a total of 30 periods. In contrast, each coupling region features waveguides of 400 nm width with 180 nm spacing to introduce additional path diversity through cross-talk. A compact taper, designed via inverse methods, bridges the width transition between grating and coupling sections. By combining multiple rounds of scattering in the grating regions and mode-mixing in the coupling regions, the chip effectively translates the spatial distribution of incident light into unique spectral signatures. Further details are provided in Supplementary Note 6.

Radar simulation

We employed the GO method, which is widely used in radar simulation62, to compute the backscattered signals from various targets. Each ray from the transmitter was traced until it either reflected off the target and returned to the receiving antenna or exited the simulation boundary. Summing these individual “sub-echoes” produced the overall radar echo. By shifting the targets’ positions, we obtained 80 distinct echo profiles per target, yielding 320 samples in total across four target categories. Further details on the simulation parameters can be found in Supplementary Note 7.

Data availability

All the data supporting this study are available in the paper and Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Abbas, N., Zhang, Y., Taherkordi, A. & Skeie, T. Mobile edge computing: a survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 5, 450–465 (2018).

Suleiman, A., Zhang, Z., Carlone, L., Karaman, S. & Sze, V. Navion: a 2-mW fully integrated real-time visual-inertial odometry accelerator for autonomous navigation of nano drones. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 54, 1106–1119 (2019).

Esteva, A. et al. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat. Med. 25, 24–29 (2019).

Obermeyer, Z. & Emanuel, E. J. Predicting the future—big data, machine learning, and clinical medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 1216–1219 (2016).

Dyrby, M., Engelsen, S. B., Nørgaard, L., Bruhn, M. & Lundsberg-Nielsen, L. Chemometric quantitation of the active substance (containing C≡N) in a pharmaceutical tablet using near-infrared (NIR) transmittance and NIR FT-Raman spectra. Appl. Spectrosc. 56, 579–585 (2002).

Maity, A. et al. Ultra-fast portable and wearable sensing design for continuous and wide-spectrum molecular analysis and diagnostics. Adv. Sci. 9, 2203693 (2022).

Li, A. et al. Advances in cost-effective integrated spectrometers. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 174 (2022).

Shrestha, A., Li, H., Le Kernec, J. & Fioranelli, F. Continuous human activity classification from FMCW radar with Bi-LSTM networks. IEEE Sens. J. 20, 13607–13619 (2020).

Saponara, S., Greco, M. S. & Gini, F. Radar-on-chip/in-package in autonomous driving vehicles and intelligent transport systems: opportunities and challenges. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 36, 71–84 (2019).

Zhou, F. & Chai, Y. Near-sensor and in-sensor computing. Nat. Electron. 3, 664–671 (2020).

Data growth worldwide 2010-2028. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/871513/worldwide-data-created/.

Chen, Y. et al. All-analog photoelectronic chip for high-speed vision tasks. Nature 623, 48–57 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. Image sensing with multilayer nonlinear optical neural networks. Nat. Photonics 17, 408–415 (2023).

Huang, Z. et al. Pre-sensor computing with compact multilayer optical neural network. Sci. Adv. 10, eado8516 (2024).

Yan, T. et al. Nanowatt all-optical 3D perception for mobile robotics. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn2031 (2024).

Shen, Y. et al. Deep learning with coherent nanophotonic circuits. Nat. Photonics 11, 441–446 (2017).

Zhou, H. et al. Photonic matrix multiplication lights up photonic accelerator and beyond. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 30 (2022).

Wu, T., Menarini, M., Gao, Z. & Feng, L. Lithography-free reconfigurable integrated photonic processor. Nat. Photonics 17, 710–716 (2023).

Cheng, J. et al. Photonic emulator for inverse design. ACS Photonics 10, 2173–2181 (2023).

Tait, A. N. et al. Neuromorphic photonic networks using silicon photonic weight banks. Sci. Rep. 7, 7430 (2017).

Feldmann, J. et al. Parallel convolutional processing using an integrated photonic tensor core. Nature 589, 52–58 (2021).

Shastri, B. J. et al. Photonics for artificial intelligence and neuromorphic computing. Nat. Photonics 15, 102–114 (2021).

Shekhar, S. et al. Roadmapping the next generation of silicon photonics. Nat. Commun. 15, 751 (2024).

Atabaki, A. H. et al. Integrating photonics with silicon nanoelectronics for the next generation of systems on a chip. Nature 556, 349–354 (2018).

Huang, C. et al. A silicon photonic–electronic neural network for fibre nonlinearity compensation. Nat. Electron. 4, 837–844 (2021).

Bandyopadhyay, S. et al. Single-chip photonic deep neural network with forward-only training. Nat. Photonics 18, 1335–1343 (2024).

Ashtiani, F., Geers, A. J. & Aflatouni, F. An on-chip photonic deep neural network for image classification. Nature 606, 501–506 (2022).

Xu, S., Liu, B., Yi, S., Wang, J. & Zou, W. Analog spatiotemporal feature extraction for cognitive radio-frequency sensing with integrated photonics. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 50 (2024).

Lin, Z., Sun, S., Azaña, J., Li, W. & Li, M. High-speed serial deep learning through temporal optical neurons. Opt. Express 29, 19392–19402 (2021).

Bai, B. et al. Microcomb-based integrated photonic processing unit. Nat. Commun. 14, 66 (2023).

McMahon, P. L. The physics of optical computing. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 717–734 (2023).

Yang, Z., Albrow-Owen, T., Cai, W. & Hasan, T. Miniaturization of optical spectrometers. Science 371, eabe0722 (2021).

Cheben, P. et al. A high-resolution silicon-on-insulator arrayed waveguide grating microspectrometer with sub-micrometer aperture waveguides. Opt. Express 15, 2299–2306 (2007).

Subramanian, A. Z. et al. Silicon and silicon nitride photonic circuits for spectroscopic sensing on-a-chip [Invited]. Photonics Res. 3, B47–B59 (2015).

Zhang, S. et al. Redundancy-free integrated optical convolver for optical neural networks based on arrayed waveguide grating. Nanophotonics 13, 19–28 (2024).

Xu, S. et al. Optical coherent dot-product chip for sophisticated deep learning regression. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 221 (2021).

Xu, X. et al. 11 TOPS photonic convolutional accelerator for optical neural networks. Nature 589, 44–51 (2021).

Meng, X. et al. Compact optical convolution processing unit based on multimode interference. Nat. Commun. 14, 3000 (2023).

Zhu, H. H. et al. Space-efficient optical computing with an integrated chip diffractive neural network. Nat. Commun. 13, 1044 (2022).

Fan, L., Wang, K., Wang, H., Dutt, A. & Fan, S. Experimental realization of convolution processing in photonic synthetic frequency dimensions. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi4956 (2023).

Tait, A. N. et al. Silicon photonic modulator neuron. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 064043 (2019).

Song, L. et al. Low-loss calibration-free 2 × 2 Mach-Zehnder switches with varied-width multimode-interference couplers. J. Light. Technol. 40, 5254–5259 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Silicon microring synapses enable photonic deep learning beyond 9-bit precision. Optica 9, 579 (2022).

Wu, B. et al. Real-valued optical matrix computing with simplified MZI mesh. Intell. Comput. 2, 0047 (2023).

Xue, Z. et al. Fully forward mode training for optical neural networks. Nature 632, 280–286 (2024).

Pai, S. et al. Experimentally realized in situ backpropagation for deep learning in photonic neural networks. Science 380, 398–404 (2023).

Hughes, T. W., Minkov, M., Shi, Y. & Fan, S. Training of photonic neural networks through in situ backpropagation and gradient measurement. Optica 5, 864–871 (2018).

Ganin, Y. et al. Domain-adversarial training of neural networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 1–35 (2016).

Lin, Z. et al. High-performance, intelligent, on-chip speckle spectrometer using 2D silicon photonic disordered microring lattice. Optica 10, 497–504 (2023).

Redding, B., Liew, S. F., Sarma, R. & Cao, H. Compact spectrometer based on a disordered photonic chip. Nat. Photonics 7, 746–751 (2013).

Cheung, S., Su, T., Okamoto, K. & Yoo, S. J. B. Ultra-compact silicon photonic 512 × 512 25 GHz arrayed waveguide grating router. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 20, 310–316 (2014).

Bruce, G. D., O’Donnell, L., Chen, M., Facchin, M. & Dholakia, K. Femtometer-resolved simultaneous measurement of multiple laser wavelengths in a speckle wavemeter. Opt. Lett. 45, 1926–1929 (2020).

Bruce, G. D., O’Donnell, L., Chen, M. & Dholakia, K. Overcoming the speckle correlation limit to achieve a fiber wavemeter with attometer resolution. Opt. Lett. 44, 1367–1370 (2019).

Wen, Z. et al. Single multimode fibre for in vivo light-field-encoded endoscopic imaging. Nat. Photonics 17, 679–687 (2023).

Takada, K., Abe, M., Shibata, T. & Okamoto, K. 1-GHz-spaced 16-channel arrayed-waveguide grating for a wavelength reference standard in DWDM network systems. J. Light. Technol. 20, 850–853 (2002).

Hu, B. B. & Nuss, M. C. Imaging with terahertz waves. Opt. Lett. 20, 1716–1718 (1995).

Woodward, R. M. et al. Terahertz pulse imaging in reflection geometry of human skin cancer and skin tissue. Phys. Med. Biol. 47, 3853 (2002).

Cooper, K. B. et al. THz imaging radar for standoff personnel screening. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 1, 169–182 (2011).

Yu, M. et al. Integrated femtosecond pulse generator on thin-film lithium niobate. Nature 612, 252–258 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. A photonic integrated circuit–based erbium-doped amplifier. Science 376, 1309–1313 (2022).

Cheng, J. et al. Self-calibrating microring synapse with dual-wavelength synchronization. Photonics Res. 11, 347–356 (2023).

Knott, E. F. Chapter 14: Radar cross section. In Radar Handbook (ed. Skolnik, M. I.) (McGraw-Hill Education, 2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62425504 to J.J.D.); Knowledge Innovation Program of Wuhan -Basic Research (2023010201010049 to J.J.D.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J.Z. conceived the idea. S.J.Z., X.Y.J., and W.G.X. designed and performed the experiments. S.J.Z., X.Y.J., B.W., H.J.Z., H.L.Z., Z.C.R., and X.L.Z. discussed and analyzed data. S.J.Z. prepared the manuscript. J.J.D. revised the paper. J.J.D. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Jiang, X., Wu, B. et al. Photonic edge intelligence chip for multi-modal sensing, inference and learning. Nat Commun 16, 10136 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65151-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65151-x