Abstract

Sepsis, a syndrome of life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by dysregulated host responses to infection, exhibits profound pathobiological heterogeneity, hindering the development of effective therapies. Current subtyping approaches, often reliant on single-omics data or unsupervised clustering, yield poorly reproducible and therapeutically misaligned classifications. Here, we introduce a goal-directed subgroup identification (GD-SI) framework that optimizes patient stratification for differential treatment responses, integrating longitudinal multi-omics data (transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, phenomic) from 1327 subjects across 43 hospitals. While supervised multi-omics integration frameworks (e.g., DIABLO) effectively capture shared biological signals, our approach anchors subgroup discovery directly to treatment-effect optimization. This strategy achieves substantial cross-omic concordance and, crucially, generalizes to predict differential treatment response across international critical care databases. Patients stratified by GD-SI-derived benefit scores for restrictive versus liberal fluid resuscitation exhibited marked survival differences, with similar advantages observed for ulinastatin immunomodulation. External validations in MIMIC-IV and ZiGongDB confirm prognostic generalizability. This framework reconciles biological heterogeneity with clinical actionability, offering a scalable infrastructure for precision trial design and personalized sepsis management. Our findings underscore the translational potential of omics-driven, goal-directed stratification to overcome decades of therapeutic stagnation in critical care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis, a life-threatening syndrome driven by dysregulated host responses to bacterial or viral infections, remains a leading global cause of mortality, accounting for 20% of all global deaths1. Despite decades of research that have marginally reduced sepsis-related deaths through standardized protocols2,3, recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) failed to identify therapies that significantly improve survival—a stagnation attributed to the syndrome’s profound pathobiological heterogeneity4,5,6,7. Emerging evidence reveals distinct sepsis subtypes with divergent clinical trajectories and treatment responses8,9,10,11,12, yet existing subtyping frameworks exhibit critical limitations: classification systems derived from single-omics datasets or unsupervised clustering algorithms demonstrate poor interstudy reproducibility and lack therapeutic alignment13,14. For instance, transcriptomic vs. phenomic clustering analyses often yield non-overlapping patient stratifications13, while subtype-specific treatment effects for interventions like immunomodulators or vasopressors have not been validated consistently15,16. While modern supervised integrative methods (e.g., DIABLO) successfully resolve biological discordance to yield stable phenotypes17, phenotypes optimized for biological coherence may not inherently capture variation in treatment response. This highlights a distinct and unmet need for subtyping paradigms that are explicitly designed to prioritize clinical actionability and therapeutic personalization.

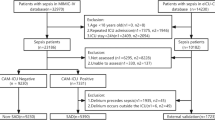

To bridge this translational gap, we propose a goal-directed subgroup identification (GD-SI) framework that explicitly links sepsis subtyping to treatment-effect optimization. The contributions of this study include the following aspects: (1) We established the first reusable, multicenter sepsis cohort integrating longitudinal multi-omics profiling (transcriptome, proteome, metabolome) with granular clinical phenomics from 1327 ICU patients across 43 hospitals. All data are FAIR-compliant (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) and available via controlled access. (2) We demonstrated that conventional unsupervised sepsis subtypes exhibited suboptimal concordance across omics layers. (3) By anchoring subtype discovery to differential treatment effects (fluid resuscitation: restrictive vs. liberal, ulinastatin response), we derived GD-SI subgroups with cross-omic reproducibility and mechanistic interpretability. (4) GD-SI subgroups were generalizable to multiple international critical care databases (MIMIC-IV, eICU-CRD, AmsterdamUMCdb) in retaining prognostic stratification power for short-term mortality (Fig. 1). By anchoring subtype discovery to specific therapeutic decisions rather than exploratory biology, this approach establishes a reusable precision medicine infrastructure, enabling rapid iteration of subtype-guided RCTs for sepsis interventions ranging from anticoagulation to renal support therapies.

The Chinese Multi-omics Advances In Sepsis (CMAISE) cohort prospectively enrolled 1327 participants (including 47 healthy controls) from 43 tertiary hospitals across mainland China. Longitudinal blood sampling (days 1, 3, and 5) yielded 3895 patient-days of phenomic data, with matched transcriptomic (n = 2,776), proteomic (n = 468), and metabolomic (n = 457) profiles. Key analytical steps included: (1) Unsupervised Consensus Clustering: Applied to each omics layer (transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, phenome) to identify sepsis subtypes, followed by cross-omics cluster concordance analysis. (2) Goal-Directed Subgroup Identification (GD-SI): Implemented via LASSO-penalized regression to optimize subgroups for differential treatment effects of ulinastatin (UTI) and fluid resuscitation strategies. (3) Subgroup Validation: Cross-omics concordance of GD-SI-derived clusters and external validation of fluid response subgroups in public critical care datasets (e.g., MIMIC-IV, eICU-CRD). CMAISE Chinese Multi-omics Advances In Sepsis, UTI ulinastatin, GD-SI goal directed subgroup identification, LASSO least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, HR hazard ratio, MIMIC medical information mart for intensive care, eICU-CRD eICU collaborative research database.

Results

Participants and baseline characteristics

The CMAISE cohort enrolled 1327 subjects across 43 hospitals, with longitudinal sampling spanning 3895 patient-days of clinical and multi-omics data. After excluding 47 healthy controls, we rigorously aligned transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and phenomic profiles at matched timepoints, yielding 457 patient-days (35.0% of total) with complete cross-omics data for subtype concordance analysis. The remaining 3438 patient-days were allocated to therapeutic validation of GD-SI-derived subgroups.

Baseline clinical characteristics between the complete-data and validation cohorts were balanced across age, sex, mortality and vital signs (all P > 0.1, Supplementary Table S2). The complete-data group exhibited a higher prevalence of pulmonary/thoracic infections (49% vs. 42%, P < 0.001) but lower rates of pre-existing heart failure (5% vs. 12%, P = 0.005) and cerebrovascular disease (13% vs. 21%, P = 0.023). These differences were attenuated after Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction (q > 0.1), confirming minimal selection bias.

Unsupervised sepsis clustering across omic layers

Consensus clustering was systematically applied to transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and phenomic datasets using cluster numbers ranging from k = 2–6. Optimal cluster counts varied across algorithms and omics layers, as determined by consensus heatmap (Supplementary Figs. S1 to S11) and minimizing the proportion of ambiguous clustering (PAC < 0.3). For instance, affinity propagation achieved maximal stability at k = 3 for transcriptomic data (PAC = 0.21; S = 0.68), whereas NMF-Brunet performed optimally at k = 4 for metabolomic profiles (PAC = 0.18; S = 0.72). It is important to note that while the PAC metric guided the assessment of cluster stability within each individual omics layer, the pronounced lack of agreement in optimal cluster number across layers (Fig. 2) precluded the designation of a single, universal k for multi-omics integration. Thus, the PAC analysis was used to evaluate within-layer stability rather than to dictate a cross-optimal cluster number. Final subtype assignments for each patient were derived through majority voting across 12 algorithms (AP, BLOCK, CMEANS, etc.), resolving ties via modal agreement (Supplementary Fig. S12).

a–d Proportion of Ambiguity Clustering (PAC) values for transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, and phenome datasets across clustering algorithms (AP, BLOCK, CMEANS, DIANA_Euclidean, GMM, HC_Euclidean, KM, NMF_Brunet, NMF_Lee, PAM_Euclidean, SC, SOM) over cluster numbers k = 2 to 6. Lower PAC values indicate higher clustering stability. e–g Alluvial plots mapping patient transitions between omics-derived clusters. Sample distribution across clusters for metabolome, phenome, proteome, and transcriptome datasets at k = 2, 3, 4. Stacked bars reflect cluster assignments for each omics type, illustrating alignment of patient subgroups across transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, and phenome layers. AP affinity propagation, BLOCK biclustering using a latent block model, CMEANS fuzzy C-means clustering, DIANA_Euclidean dIvisive ANAlysis clustering, GMM Gaussian mixture model using Bayesian information criterion on EM algorithm, HC_Euclidean hierarchical clustering, KM K-means clustering, NMF nonnegative matrix factorization, PAM_Euclidean Partition Around Medoids, SC spectral clustering using Radial-Basis kernel function, SOM self-organizing map, PAC proportion of ambiguous clustering.

Inter-omics subtype concordance was quantified for k = 2–4 using Light’s κ statistics. After aligning cluster assignments across modalities using Hungarian algorithm (optimal assignment), only 63/457 patients (13.8%, 95% CI 10.7–17.4%) exhibited consistent subtype labels across all omics layers at k = 2, declining to 17 (3.7%, CI 2.1–5.8%) at k = 3 and 2 (0.4%, CI 0.05–1.5%) at k = 4 (Benjamini–Hochberg q < 0.05; Fig. 2a–d). Discordance primarily stemmed from transcriptomic vs. phenomic stratification mismatches (κ = −0.114), contrasting with higher proteome-metabolome alignment (κ = 0.0556). Although κ values across modalities were relatively low, this does not necessarily invalidate a biology-first classification, as each omics layer may reflect a distinct axis of the sepsis continuum, capturing complementary rather than redundant biological features.

DIABLO identifies multi-omics signatures associated with sepsis-induced acute kidney injury

To identify a coherent multi-omics signature associated with AKI subtypes, we applied the DIABLO (Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker discovery using Latent cOmponents) framework. This supervised integrative method models relationships between multiple omics datasets and a categorical outcome—here, AKI status as defined by the SOFA renal component score—by extracting latent components that maximize covariance between data blocks while balancing classification accuracy and integration.

Model performance was optimized through component number selection. Both overall and balanced error rates (BER) decreased steadily up to six components, with minimal further improvement beyond this point, as indicated by error standard deviations (Supplementary Fig. S13). Consequently, the final model was constructed using six components to achieve optimal discriminative power.

Visualization of the first two components revealed distinct centroid positions for each AKI subtype, though moderate overlap in confidence ellipses indicated residual within-group heterogeneity (Fig. 3a). Loading analysis demonstrated that the majority of transcriptomic variables contributed negatively to the first component, while phenomic variables exhibited separation across both component dimensions (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. S14).

a Diagnostic plot from multiblock sPLS-DA applied on the CMAISE study. Samples are represented based on the specified component (here ncomp = 1) for each data set (Transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics and phenomics). Samples are colored by AKI severity scores and 95% confidence ellipse plots are represented. b Correlation circle plot from multiblock sPLS-DA performed on the CMAISE study. Variable types are indicated with different symbols and colors, and are overlaid on the same plot. A majority of the transcriptomic variables are negatively correlated with the first component while the phenomic variables seem to separate along both dimensions. These first two components correlate highly with the selected variables from the metabolomic dataset. From this, the correlation of each selected feature from all four datasets can be evaluated based on their proximity. c Sample plot from multiblock sPLS-DA performed on the CMAISE study. The samples are plotted according to their scores on the first 2 components for each data set. Samples are colored by AKI subtype. d ROC and AUC based on multiblock sPLS-DA for the proteomic data set after 3 components. The function calculates the ROC curve and AUC for one class vs. the others.

We further assessed clustering quality by projecting samples into the component space of each omics block. This analysis revealed differential discriminative power across data types: proteomic data showed the clearest separation between AKI subtypes, followed by metabolomic data, while transcriptomic data exhibited the lowest clustering quality (Fig. 3c). This pattern suggests particularly strong subtype-discriminative information contained within the proteomic data (Fig. 3d).

Collectively, our DIABLO-based integration identified a robust multi-omics signature highly correlated with AKI subtypes. This signature demonstrates both significant discriminative capacity and substantial biological interpretability, providing a validated foundation for further mechanistic investigation.

Goal-directed subgroup identification for differential fluid resuscitation response in sepsis

Fluid resuscitation strategies in sepsis remain controversial due to heterogeneity in study populations and therapeutic outcomes18,19,20. To address this, we employed a transcriptome-driven goal-directed subgroup identification (GD-SI) framework to stratify patients based on their differential survival response to restrictive versus liberal fluid protocols. This pipeline involved three integrated steps: first, we controlled for baseline confounding using propensity scores. Second, we applied an A-learning Cox model to estimate individual-level treatment benefit scores. Finally, we used LASSO regularization to refine these scores into a parsimonious model based on a sparse set of transcriptomic and clinical features, resulting in a continuous benefit score for each patient. Transcriptomic analysis revealed substantial overlap between restrictive and liberal strategy groups (Fig. 4a). We derived a fluid benefit score (range: −2.3 to 0.50) using Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO)-penalized regression, where higher scores favored restrictive strategies. Patients above the 60th percentile benefit score threshold exhibited a significant survival benefit from restrictive protocols (median OS: 68.1 vs. 53.8 days; HR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.66–0.94, P < 0.05). Conversely, those below the threshold (n = 183/457) showed a survival benefit with liberal strategies (median OS: 92.4 vs. 36.4 days; HR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.56–0.95. P < 0.05; Fig. 4b). LASSO regression identified eight genes predictive of fluid response (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table S5): RERT-LncRNA (ENSG00000171570), ACTBP8 (ENSG00000220267), IGHV3-15 (ENSG00000211943), LOC107986954 (ENSG00000287927), ENSG00000284431 (uncharacterized lncRNA), HNRNPUL2-BSCL2 (ENSG00000234857), SCN5A (ENSG00000183873), TGM3 (ENSG00000125780). Differential expression analysis between strategy-specific subgroups highlighted enrichment in immunoglobulin regulation, azurophil granule membrane activity, and ATPase complex assembly (Fig. 4e, f). The enrichment of immunoglobulin regulation and azurophil granule activity suggests a state of dysregulated innate and adaptive immunity, which can exacerbate endothelial injury and capillary leak—a key determinant of fluid requirements in critical illness21. Concurrently, alterations in ATPase assembly point to cellular energy failure, potentially impairing vascular tone and fluid homeostasis22. In an independent cohort (2319 patient-days), adherence to GD-SI-recommended strategies reduced mortality risk (HR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.23–1.65; P < 0.001 for non-adherence). Subgroups defined by benefit scores retained prognostic discrimination across ICU settings (C-index = 0.71).

a Density plots and histograms of propensity scores for restrictive (blue) and liberal (orange) fluid strategy groups (<3 L/day and SOFACV ≥ 2 vs ≥3 L/day or SOFACV < 2 over the initial 5-day window). The substantial overlap in distributions (common support area) indicates balanced baseline characteristics between treatment arms. b Mean survival outcomes for adherence to GD-SI-recommended fluid strategies in training (left panel) and bias-corrected validation cohorts (right panel). Bootstrap resampling (1000 iterations) was applied to adjust for estimator bias. Intersection of the curves confirms survival benefits when adhering to recommended strategies. c Regularization paths for transcriptomic feature coefficients across increasing model complexity (λ values). Each trajectory represents a feature’s coefficient shrinkage, with key predictors (e.g., ENSG00000171570, ENSG00000220267, ENSG00000211943) retained at λ = 1-se (vertical dotted line). d Partial likelihood deviance (y-axis) versus λ (x-axis), demonstrating improved model fit (lower deviance) with optimal complexity at λ = 1-se (1-SE rule, gray dashed line). Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval (n = 457). e Volcano plot comparing gene expression (fold change, x-axis) between liberal and restrictive strategies, with significance thresholds (FDR-adjusted p value: −log10[P] > 1.3, log2[fold change] > 1.5; horizontal dashed line). Top hits include LOC124901358 and SLC6A19. f Tree plot of enriched pathways (rows) for differentially expressed genes, colored by adjusted p values. Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using a hypergeometric test. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg method, and nodes are colored by these adjusted p values (-log10 scale). The size of the circle indicates the number of genes. The enrichment of immunoglobulin regulation and azurophil granule activity suggests a state of dysregulated innate and adaptive immunity, which can exacerbate endothelial injury and capillary leak—a key determinant of fluid requirements in critical illness. Concurrently, alterations in ATPase assembly point to cellular energy failure, potentially impairing vascular tone and fluid homeostasis. FC fold change, NS non-significance.

Similar analyses were performed in proteome, metabolome and phenome layers. The results showed that subgroups can be identified in each omics layer. In the proteome data, We derived a fluid benefit score (range: −4.54 to 1.13) using LASSO-penalized regression, where higher scores favored restrictive strategies. Among patients above the 60th percentile benefit score threshold, those assigned to a restrictive fluid protocol had a significantly lower risk of death than those assigned to a liberal protocol (HR = 0.78, 95% CI [0.56, 0.93], log-rank P < 0.05). LASSO regression identified five palsma proteins predictive of fluid response (Supplementary Fig. S15): IL13 (0.694), NCLN (0.1673), NCR1 (−0.1946), CCL21 (−0.1027), and CDON (−0.0613). Some enriched pathways included Reactome immunoregulator, Reactome TNF-alpha non-canonical NF-kB pathway, and Marzec IL-2 signaling pathway. The enriched Reactome Immunoregulatory Interactions pathway suggests fluid resuscitation may modulate immune cell crosstalk (e.g., T-cell/B-cell coordination) to mitigate sepsis-induced hyperinflammation, potentially stabilizing endothelial function and reducing capillary leak23. The TNF-alpha non-canonical NF-κB pathway enrichment implies fluid strategies could influence inflammatory signaling cascades, where balanced resuscitation may suppress excessive TNF-α-mediated organ damage. Additionally, the Marzec IL-2 Signaling Pathway indicates fluid management might alter T-cell activation and cytokine production, impacting immune homeostasis in critical illness24.

Using LASSO-penalized regression in metabolome layer, we derived a fluid benefit score (range: −0.97 to −0.26) to stratify patients by response to restrictive versus liberal fluid resuscitation strategies, with higher scores indicating preferential benefit from restrictive protocols. Patients below the 60th percentile threshold (n = 198/457) exhibited survival benefits (HR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.58–0.88, p < 0.05) when adhering to liberal strategies compared to restrictive. Key predictive metabolites identified included hydroxypropionic acid, gluconolactone, and N-acetylneuraminic acid (Supplementary Fig. S14). Similarly, a phenome-derived fluid benefit score (range: −1.37 to 0.16) was generated via LASSO regression, with higher scores favoring restrictive strategies. Patients below the 60th percentile (n = 183/457) demonstrated a survival advantage with liberal protocols (HR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.61–0.87; p < 0.05). Predictive clinical variables included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), and actual base excess (ABE) (Supplementary Fig. S17). Differential analysis revealed significant disparities in chloride levels, maximum respiratory rate, arterial pH, and CRRT utilization between fluid-strategy subgroups. In the CMAISE cohort, there was U-shaped relationship between fluid intake and mortality outcome moderated by the SOFA cardiovascular scores (Supplementary Fig. S18).

Data on fluid intake and vasopressor utilization are accessible in multiple public critical care databases, including MIMIC-IV25, eICU-CRD26, GuangzhouDB27, AmsterdamUMCdb28, and ZigongDB29 (Supplementary Table S3). Subgroup identification models developed using clinical variables demonstrated improved survival outcomes when validated in MIMIC-IV and AmsterdamUMCdb cohorts, where non-adherence to recommended resuscitation strategies (e.g., restrictive or liberal fluid protocols) was associated with increased mortality risks (HR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.09–1.46 in MIMIC-IV, 1.84, 95% CI: 1.22–2.01 in AmsterdamUMCdb). However, this survival benefit was not consistently replicated in the eICU-CRD (HR: 1.02 [0.87–1.12]) and ZiGongDB datasets (HR: 0.99 [0.88–1.23]), suggesting potential heterogeneity in patient populations, treatment practices, or data granularity across these platforms (Supplementary Table S4).

Goal-directed subgroup identification for differential ulinastatin response in sepsis

Although widely used in Mainland China for sepsis, the efficacy of Ulinastatin (UTI)—an immunomodulatory agent—remains controversial, resulting in substantial variations in its uses across different hospitals30,31,32. To order to understand the heterogeneity in responses to UTI, we initially developed a benefit score, ranging from −4.18 to 3.75, based on transcriptome data through LASSO-penalized regression. Higher scores imply a positive response to UTI. Among patients with a benefit score above the 60th percentile (274 out of 457 patients), a 79-day median survival benefit was observed when using UTI compared to those who did not receive UTI (HR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.55–0.91; p < 0.05, Fig. 5). Conversely, patients below the 60th percentile threshold (183 out of 457) showed a 3.3-day improvement in median overall survival (mOS) if they did not receive UTI (HR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.76–1.02; p = 0.053). Differential expression analysis between subgroups specific to different strategies (UTI vs. control) revealed enrichment in functions related to respirasome phosphatase, phagocytic vesicle membrane, and immunoglobulin complex. In an independent cohort comprising 2319 patient-days, adhering to the GD-SI-recommended strategies was associated with an improvement in survival outcome (HR = 1.28, 95% CI: 1.14–1.37; P < 0.001 for non-adherence).

a Density plots and histograms of propensity scores for UTI (blue) and Ctrl (orange) groups over the initial 5-day window. The limited common support area indicates unbalanced baseline characteristics between treatment arms. b Mean survival outcomes for adherence to GD-SI-recommended UTI treatment in training (left panel) and bias-corrected validation cohorts (right panel). Bootstrap resampling (1000 iterations) was applied to adjust for estimator bias. Intersection of the curves confirms survival benefits when adhering to recommended strategies. c Regularization paths for transcriptomic feature coefficients across increasing model complexity (λ values). Each trajectory represents a feature’s coefficient shrinkage, with key predictors retained at λ = 1-se (vertical dotted line). d Partial likelihood deviance (y-axis) versus λ (x-axis), demonstrating improved model fit (lower deviance) with optimal complexity at λ = 1-se (1-SE rule, gray dashed line). Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval (n = 457). e Volcano plot comparing gene expression (fold change, x-axis) between liberal and restrictive strategies, with significance thresholds (FDR-adjusted p value: −log10[P] > 5, log2[fold change] > 1.5; horizontal dashed line). Top hits include ENSG00000282885, SHANK1 and ENSG00000260549. f Tree plot of enriched pathways (rows) for differentially expressed genes, colored by adjusted p values. The size of the circle indicates the number of genes. Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using a hypergeometric test. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. The enrichment of phagocytic vesicle and immunoglobulin pathways suggests a state of neutrophil and humoral immune activation, which may be modulated by UTI’s known protease inhibition and anti-inflammatory properties. Simultaneously, alterations in respirasome function point to mitochondrial dysregulation, a process UTI may ameliorate by preserving cellular energetics and reducing oxidative stress. FC fold change, NS non-significance, UTI ulinastatin.

Similar analyses were performed in proteome, metabolome and phenome layers. The results showed that subgroups can be identified in each omics layer. In the proteome data, we derived a UTI benefit score (range: −6.46 to 9.21) using LASSO-penalized regression, where higher scores favored UTI use. Patients above the 60th percentile benefit score threshold exhibited a 65-day survival advantage when adhering to UTI versus control. LASSO regression identified 10 plasma proteins predictive of a favorable response to UTI (Supplementary Fig. S19): FCRL3, NCLN, IL5, IL1A, CLEC4C, IL15, NTF3, CD276, CTRC and CCL24. Some enriched pathways included reactome immunoregulator, reactome TNF-alpha non-canonical NF-kB pathway, and Marzec IL-2 signaling pathway (Supplementary Fig. S19).

Using LASSO-penalized regression in metabolome layer, we derived an UTI benefit score (range: −6.3 to 34.9) to stratify patients by response to UTI versus control treatments, with higher scores indicating preferential benefit from UTI use. Patients above the 60th percentile threshold exhibited a 61-day survival advantage when adhering to UTI compared to controls. Key predictive metabolites identified included Creatine, Hydroxypropionic acid, Kynurenine, and Aminoadipic acid (Supplementary Fig. S20). Similarly, a phenome-derived UTI benefit score (range: −7.66 to 19.34) was generated via LASSO regression, with higher scores favoring UTI use. Patients above the 60th percentile (n = 274/457) demonstrated a 54-day survival advantage with UTI use. Predictive clinical variables included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), lactate, mechanical ventilation, and diabetes (Supplementary Fig. S21). Differential analysis revealed significant disparities in lactate levels, renal failure, diabetes, and CRRT utilization between UTI and control groups.

Inter-omics concordance of goal-directed subgroup identification

Goal-Directed Subgroup Identification (GD-SI) demonstrated robust cross-omics concordance in stratifying sepsis patients who would respond favorably to Ulinastatin (UTI) and fluid resuscitation therapies. For UTI treatment stratification, proteome-BS exhibited the strongest correlation with transcriptome-BS (Pearson’s r = 0.627, P < 0.01), followed by metabolome-BS and transcriptome-BS (r = 0.594, P < 0.01; Fig. 6a). Using a 60th percentile BS threshold to classify patients into UTI-recommended or non-recommended subgroups, 307/457 patients (67.2%) showed consistent cluster membership across all four omics layers, with substantial agreement (Light’s κ = 0.638, P = 1.26 × 10−4; Fig. 6b). For fluid strategy stratification, phenome-BS correlated most strongly with transcriptome-BS (r = 0.767, P < 0.01), followed by transcriptome-BS and proteome-BS (r = 0.630, P < 0.01; Fig. 6c). Similarly, 304/457 patients (66.5%) demonstrated cross-omics cluster consistency (Light’s κ = 0.63, P = 1.6 × 10−4; Fig. 6d). These results highlight GD-SI’s ability to reconcile omics heterogeneity, yielding reproducible, biologically coherent subgroups (κ > 0.6) that align with therapeutic responses, thereby supporting their utility in precision trial design and personalized sepsis management.

a Matrix plot depicting pairwise correlations of ulinastatin (UTI) benefit scores across omics layers (transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, phenome). Correlations were calculated using Pearson correlation. Diagonal histograms show the distribution of omics-specific benefit scores. Correlation coefficients (Corr) and significance (***P < 0.001) are annotated. b Sankey diagram illustrating alignment of cluster memberships derived from UTI benefit scores across omics layers. Edge widths reflect the proportion of patients consistently stratified into the same subgroup. c Matrix plot of pairwise correlations for fluid resuscitation benefit scores across omics layers, with diagonal histograms showing score distributions. Correlations were calculated using Pearson correlation, which is a two-sided test. (***P < 0.001). d Sankey plot demonstrating cross-omics concordance of fluid strategy subgroups, with cluster transitions quantified by patient overlap. Corr Pearson’s correlation coefficient, UTI ulinastatin, the Chinese Multi-omics Advances In Sepsis (CMAISE) Consortium.

Discussion

The present study introduces a goal-directed subgroup identification (GD-SI) framework to reconcile the translational disconnect between sepsis subtyping and therapeutic decision-making. By anchoring subtype discovery to differential treatment effects rather than exploratory biology, our approach addresses critical limitations of conventional unsupervised methods, which prioritize biological plausibility over clinical actionability. The integration of longitudinal multi-omics data from the CMAISE cohort, coupled with rigorous external validation, demonstrates that GD-SI-derived subgroups exhibit robust cross-omic concordance and prognostically stratify patients for targeted interventions such as fluid resuscitation and Ulinastatin (UTI) therapy. These findings advance sepsis precision medicine by establishing a reproducible infrastructure for subtype-guided trials and personalized management.

Our results underscore the profound discordance of sepsis subtypes derived from unsupervised clustering across omics layers13. While transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and phenomic data each captured distinct biological axes, their misalignment (e.g., κ = −0.114 for transcriptome-phenome clusters) highlights the inadequacy of single-omics or purely data-driven approaches for therapeutic stratification. In contrast, GD-SI subgroups—optimized for differential treatment effects—achieved substantial cross-omic agreement (κ > 0.6) that was generalizable to patient cohorts in multiple international critical care databases. For instance, non-adherence to GD-SI-recommended fluid strategies increased relative mortality risk by 45% (HR = 1.45, P < 0.001). Similarly, UTI-benefit subgroups identified by the transcriptomic LASSO regression had a survival advantage with the use of UTI, and this was explained by pathway enrichments in immunoregulation and cellular respiration. These results align with emerging evidence that treatment response, rather than static biomarkers, should drive sepsis subtyping frameworks.

Previous studies have largely focused on unsupervised clustering or single-omics signatures33,34,35,36, yielding subtypes with limited reproducibility and therapeutic relevance37. Our findings align with prior evidence that sepsis subtyping strategies—whether based on clinical features, biomarkers, or transcriptomic signatures—yield non-overlapping patient cohorts, reflecting divergent biologic underpinnings rather than a unified taxonomy13. Our prior work demonstrated that unsupervised clustering analysis across six international cohorts exhibited modest reproducibility (median normalized mutual information: 0.08–0.54), underscoring that sepsis subtypes identified in one cohort frequently fail to be generalized to others due to the heterogeneous and evolving nature of the syndrome14. This inconsistency likely stems from the inherent continuum of sepsis pathophysiology, with which patients exhibit overlapping features rather than distinct boundaries. Intermediate cases may move between clusters depending on cohort-specific factors like severity of illness or variation in clinical practices. However, the SUBSPACE framework harmonizes disparate sepsis endotypes (e.g., Sweeney’s inflammopathic/adaptive38, MARS subtypes39) into a cohesive model, revealing shared biology across syndromes. By anchoring dysregulation scores to cell-specific gene expression—validated via single-cell RNA-seq—this study clarifies the cellular drivers of critical illness, such as immature neutrophils in myeloid dysregulation and exhausted T cells in lymphoid dysfunction. This mechanistic granularity advances beyond prior transcriptomic classifiers, which often lacked interpretability or therapeutic alignment40. Our work extends these efforts by integrating multi-omics data and explicitly modeling treatment effects, thereby resolving the “biological vs. actionable” dichotomy. The GD-SI framework also addresses heterogeneity in fluid resuscitation and immunomodulator responses, two areas where RCTs have consistently failed to change clinical practice, largely due to heterogeneity in treatment effects by enrolling unstratified populations. By aligning subgroups with mechanistically interpretable pathways (e.g., immunoglobulin regulation, TNF-α signaling), our approach integrates molecular insights into clinical decision-making—a pivotal advancement in defining actionable sepsis endotypes.

Several limitations merit consideration. First, while the CMAISE cohort is Asia’s largest sepsis multi-omics resource, its geographic focus (China) may limit generalizability to other populations. The inconsistent validation of fluid responsive subgroups using the eICU-CRD and ZiGongDB databases underscores the potential of demographic or protocol-driven biases, necessitating broader international collaboration. It is critical to note that the survival differences observed based on adherence to the GD-SI recommendation are derived from observational, post-hoc comparisons. While provocative, these associations may be influenced by residual confounding and are not equivalent to the causal effects estimated by the model itself. These results should be interpreted as generating hypothesis for future validation in prospective studies. Second, GD-SI relies on LASSO regression, which, while effective for high-dimensional data, may overlook nonlinear interactions or temporal dynamics in sepsis pathophysiology. Future studies could integrate machine learning architectures (e.g., deep learning) or longitudinal modeling to capture patients’ evolving states. Third, the 60th percentile threshold for benefit scores, though statistically justified, requires validation in prospective trials to confirm its clinical utility. Furthermore, our primary mortality analysis, while employing time-to-event models, was limited by the inability to account for patients who may have been discharged to die at home, a common practice in the regional healthcare context. This precludes a direct composite endpoint analogous to “in-hospital mortality plus discharge to hospice” used in other critical care literature, and should be considered when comparing our findings with studies from healthcare systems with more granular post-discharge vital status tracking.

Beyond its implications for hemodynamic/UTI management, our study invites consideration of how multi-omic signatures could inform other therapeutic dilemmas in sepsis. The initial decision to administer antibiotics—and to do so rapidly—represents a perhaps even more pressing clinical uncertainty. A compelling future application of this approach would be to derive host-response signatures that predict a patient’s likelihood of having a confirmed bacterial infection and their potential to respond to antimicrobial therapy41. Such a tool would be of immense practical value, helping to resolve the ongoing debate about antibiotic timing in sepsis without shock and providing much-needed guidance for the ~50% of cases without microbiological confirmation.

By harmonizing multi-omics heterogeneity with therapeutic optimization, the GD-SI framework represents a paradigm shift in sepsis research. Its ability to derive reproducible, clinically actionable subgroups addresses longstanding barriers to precision critical care. As sepsis management evolves beyond “one-size-fits-all” protocols, GD-SI provides a scalable infrastructure for rapidly iterating subtype-guided RCTs and implementing dynamic treatment algorithms at the bedside. Future work should prioritize real-world validation of these subgroups through decentralized trials and interoperable digital platforms, ultimately translating omics-driven insights into measurable improvements in sepsis outcomes.

Methods

The CMAISE cohort

This study was approved the ethical approval of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital (Ethics Approval No.: 20201014-39) and other particiapating hospitals (Supplementary Methods), with written informed consent obtained from all participants or their legally authorized surrogates. Sex was incorporated as a biological variable in the study design, and clinical data are reported and analyzed disaggregated by sex. Participants were provided non-monetary compensation through access to their de-identified health data and personalized clinical insights. As part of the Chinese Multi-omics Advances In Sepsis (CMAISE) consortium (Supplementary Methods)42, the prospective cohort enrolled patients across 43 tertiary hospitals in China between November 2020 and November 2024. The protocol was prospectively registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000040446; accessible at https://www.chictr.org.cn/). Inclusion Criteria included Adults ≥ 18 years meeting Sepsis-3.0 criteria (suspected/documented infection + acute SOFA score increase >2 points) on ICU admission43. Septic shock was defined as hypotension (mean arterial pressure <65 mmHg) requiring vasopressors post-fluid resuscitation. Exclusion Criteria included End-stage cirrhosis (Child–Pugh C); Active malignancy or autoimmune disease; Do-not-resuscitate orders; Pregnancy; Sepsis onset >48 h prior to enrollment or prior treatment at non-CMAISE centers; Immunosuppression (chronic immunosuppressants, chemotherapy, corticosteroids >20 mg/day prednisone-equivalent for >14 days, radiotherapy, or HIV/AIDS); Acute myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolism.

The CMAISE consortium was updated to version 1.5 to expand its clinical and multi-omics scope, increasing participating hospitals/units from 35 to 43 geographically diverse tertiary hospitals across China to enhance demographic representativeness and reduce urban-centric bias44. This iteration integrates longitudinal metabolomics (Q300), high-resolution phenomics (longitudinal vital signs and laboratory variables), and standardized proteomic workflows (Olink Explore 384 panel). The expanded cohort supports robust external validation of goal-directed subgroups, positioning CMAISE_v1.5 as Asia’s largest sepsis multi-omics resource for precision critical care.

Blood sample preparation and testing

Transcriptomic profiling and analysis

Peripheral whole blood samples were collected on days 1, 3, and 5 post-enrollment using PAXgene™ Blood RNA tubes (PreAnalytiX) and stored at −80 °C until processing. RNA sequencing libraries were prepared and sequenced by LC-Bio Technologies (Hangzhou, China), with raw reads aligned to the GRCh38 human reference genome. Gene expression quantification and differential analysis were performed using the DESeq2 pipeline (v1.38.3)45, excluding genes with <100 total counts across all samples. Count data were normalized via variance-stabilizing transformation (VST) to stabilize variance across expression levels. Batch effects from multi-center sampling were adjusted using a linear model incorporating institution as a covariate. Differential expression between restrictive and liberal fluid strategy groups was visualized via volcano plots (|log2FC| > 1, FDR < 0.05). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted using clusterProfiler (v4.12.0)46, leveraging Gene Ontology (GO) terms to annotate biological pathways47,48.

Proteomic quantification and pathway analysis

Plasma protein levels were quantified using the Olink® Inflammation Panel (Olink Proteomics AB), employing proximity extension assay (PEA) technology. Briefly, target proteins were bound by oligonucleotide-labeled antibody probe pairs, enabling hybridization and DNA polymerization upon proximity. Resulting DNA templates were amplified and quantified using a microfluidic real-time PCR system (Signature Q100, LC-Bio Technologies). Normalized Protein Expression (NPX) values were log2-transformed for analysis. Differential protein expression between treatment groups was assessed via linear mixed-effects models (FDR < 0.1). Pathway enrichment analysis utilized the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB)49, implemented through clusterProfiler, to identify inflammation-related biological processes.

Matabolomic quantification

Serum samples collected from sepsis patients underwent comprehensive metabolomic profiling using the Q300 Metabolite Array Kit (Metabo-Profile Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), which employs a rigorous protocol for metabolomic profiling using ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS)50. Serum samples were thawed on ice, and proteins were precipitated using ice-cold methanol spiked with isotopically labeled internal standards (e.g., d4-succinate, 13C6-phenylalanine). After centrifugation, supernatants underwent derivatization at 30 °C to enhance polar metabolite detection, followed by dilution and re-centrifugation. Metabolite separation was achieved via an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm) with a gradient mobile phase (0.1% formic acid in water and acetonitrile/isopropanol [70:30]) over an 18-minute run. Mass spectrometry parameters included electrospray ionization (ESI±), capillary voltages (1.5–2.0 kV), and desolvation at 550 °C. Quality control (QC) measures included interspersed pooled QC samples, reagent blanks, and calibration curves (LLOQ–ULOQ) to ensure reproducibility (inter-batch CV < 15%). Data were processed using TMBQ software (v1.0) for peak integration and quantitation, with multivariate analyses (PCA, PLS-DA, OPLS-DA) and univariate tests (t-test, ANOVA) performed to identify metabolic signatures. Sample and data integrity were maintained through ISO9001-compliant LIMS tracking, ensuring traceability from acquisition to analysis.

Data collection and clinical stratification

Upon ICU admission, baseline demographic variables—including age, biological sex (documented via hospital records), height, and weight—were prospectively recorded. Serial laboratory assessments (C-reactive protein, serum creatinine, urine output, procalcitonin, coagulation profiles) and daily fluid intake volumes were rigorously collected at 24-h intervals (days 1, 3, and 5). Patients were classified into two fluid management cohorts: restrictive strategy (daily fluid intake <3000 mL and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment cardiovascular subscore [SOFA-CV] ≥ 2, prioritizing vasopressor use) and liberal strategy (daily fluid intake ≥3000 mL or SOFA-CV < 2). The 3000 mL/day threshold, informed by prior critical care studies51,52,53,54, ensured statistically robust subgroup sizes while reflecting clinically meaningful fluid responsiveness phenotypes55. Fluid management strategies and Ulinastatin (UTI) administration were evaluated during the initial 5-day window, a period critical for hemodynamic stabilization and mortality outcomes. This structured approach enabled precise alignment of therapeutic interventions with patient-specific pathophysiological states, addressing heterogeneity in septic shock management.

Unsupervised consensus clutering analysis

Our cluster analysis employed consensus clustering, a robust method that integrates results from multiple algorithms to enhance result reliability and stability56. We applied several clustering algorithms, including Hierarchical Clustering, K-Means, and Partition Around Medoids, to various subsamples of the data (Supplementary Table S1). This approach captured different aspects of the data structure and mitigated the impact of individual algorithm limitations. The results were combined into a consensus matrix, indicating how frequently sample pairs clustered together and serving as a basis for assessing cluster stability.

The process generated cluster assignments across different subsamples and algorithms for varying cluster numbers (k). A consensus heatmap visually represented the consensus matrix, with rows and columns corresponding to samples and color intensity reflecting the frequency of samples being grouped together. Higher intensity signaled more frequent grouping across algorithms and subsamples, aiding in identifying distinct clusters and evaluating their stability. Based on validity indices, underperforming algorithms were trimmed to improve clustering results. Additionally, the Proportion of Ambiguous Clusters (PAC) was calculated to measure cluster ambiguity and identify the most consistent and stable clusters.

Multi-omics data integration using DIABLO

To identify biologically coherent multi-omics signatures associated with Acute Kidney Injury (AKI), we employed the Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker discovery using Latent cOmponents (DIABLO) framework implemented in the mixOmics R package (version 6.32.0)57. The categorical outcome variable for our DIABLO model was development of AKI, defined according to the SOFA renal component score, with patients stratified into two distinct classes: AKI (SOFA renal score ≥1) and No-AKI (SOFA renal score = 0).

The DIABLO framework, a supervised multiblock extension of sparse Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (sPLS-DA), was specifically constructed to maximize the covariance between omics datasets that demonstrate predictive capability for AKI status. We implemented a full design matrix to specify that all datasets should be equally weighted in their pairwise correlations, thereby ensuring balanced integration across omics platforms.

Model hyperparameters—including the optimal number of components (ncomp) and the number of features to select per dataset and component (keepX)—were systematically tuned using repeated 10-fold cross-validation with 10 repetitions, optimizing the model’s balanced error rate while maintaining generalizability. The final model was subsequently trained on the complete dataset using these optimized parameters, with performance validation through multiple robustness checks and sensitivity analyses to ensure biological relevance and statistical reliability.

Goal-directed subgroup identification

The analysis began with the construction of a propensity score function to estimate the probability of a patient receiving treatment based on covariates, which was crucial for adjusting biases in observational studies. Subgroup identification models were then fitted using the A-learning method58. These models aimed to estimate the benefit score, which quantified the expected treatment benefit for individual patients. The methodology allowed for flexible choices of loss functions and model forms. In our study, the loss function associated with the negative partial likelihood of the Cox proportional hazards model, corresponding to time-to-event outcomes, was employed. To account for temporal variations in both treatments (fluids/UTI) and omics/cluster states, we employed time-dependent Cox models. Treatments were modeled as time-varying exposures, and longitudinal omics measurements (where available) were incorporated as time-updated covariates. Additionally, variable selection was incorporated using a LASSO penalty. The fitted models were subsequently validated using bootstrap bias correction to ensure reliable estimates of treatment effects within the identified subgroups. A cutpoint based on the 60th percentile of the benefit score distribution was adopted for balanced group sizes. This meant that patients with a benefit score exceeding the 60th percentile value were recommended for the treatment, while those below this threshold were recommended the control. This approach allowed the tailoring of treatment recommendations to patients most likely to experience a positive outcome from the treatment, based on their covariate profiles. The results provided insights into how different patient subgroups respond to treatments, thereby supporting the development of personalized treatment strategies. To ensure rigorous and unbiased evaluation of the GD-SI model’s generalizability, the coefficients defining the benefit score (i.e., feature weights derived from the original LASSO model) were transported unchanged to all external validation datasets.

Concordance of cluster membership across multi-Omics

In our study, we assessed the concordance of cluster membership across multi-omics data to evaluate the consistency of patterns identified from different omics layers. To quantify the agreement of cluster membership across different omics datasets, we utilized Light’s Kappa statistic59. Light’s Kappa is a measure of inter-rater agreement that adjusts for chance agreement, making it suitable for evaluating the consistency of cluster assignments from different omics layers. To visually represent the intersection and transition of clusters across multi-omics data, we employed Sankey plots. Sankey plots provide a clear and intuitive visualization of how clusters from one omics dataset correspond to those from another. The width of the bands in the Sankey plot represents the proportion of samples transitioning from one cluster to another, highlighting the major overlaps and discrepancies between clustering results from different omics layers.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The transcriptomic data generated in this study have been deposited in the National Genomic Data Center (NGDC) repository under BioProject accession number PRJCA006118. Raw sequencing data are subject to restricted access under national data privacy regulations; approved researchers may request access through formal application to the NGDC, typically processed within two weeks. Processed transcriptomic data are publicly available at OMIX006457. Proteomic datasets are accessible via the NGDC repository under accession number OMIX006238. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

For comprehensive protocols, analytical pipelines, and additional resources, visit the CMAISE project webpage: https://github.com/zh-zhang1984/CMAISE/wiki. Source Data are provided with this paper.

References

Rudd, K. E. et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 395, 200–211 (2020).

MacPhail, A. et al. Sepsis mortality among patients with haematological malignancy admitted to intensive care 2000-2022: a binational cohort study. Crit. Care 28, 148 (2024).

Kaukonen, K.-M., Bailey, M., Suzuki, S., Pilcher, D. & Bellomo, R. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000-2012. JAMA 311, 1308–1316 (2014).

Andrews, B. et al. Effect of an early resuscitation protocol on in-hospital mortality among adults with sepsis and hypotension: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 318, 1233–1240 (2017).

Yu, Y. et al. Effectiveness of anisodamine for the treatment of critically ill patients with septic shock: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Crit. Care 25, 349 (2021).

Dulhunty, J. M. et al. Continuous vs intermittent β-lactam antibiotic infusions in critically Ill patients with sepsis: the BLING III randomized clinical trial. JAMA 332, 629–637 (2024).

Antcliffe, D. B. et al. Sepsis subphenotypes, theragnostics and personalized sepsis care. Intensive Care Med. 51, 756–768 (2025).

Zhang, Z. et al. Deep learning-based clustering robustly identified two classes of sepsis with both prognostic and predictive values. EBioMedicine 62, 103081 (2020).

Bhavani, S. V. et al. Development and validation of novel sepsis subphenotypes using trajectories of vital signs. Intensive Care Med. 48, 1582–1592 (2022).

Scherger, S. J. & Kalil, A. C. Sepsis phenotypes, subphenotypes, and endotypes: are they ready for bedside care? Curr Opin Crit Care https://doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0000000000001178 (2024).

Jang, J. Y., Yoo, G., Lee, T., Uh, Y. & Kim, J. Identification of the robust predictor for sepsis based on clustering analysis. Sci. Rep. 12, 2336 (2022).

Chenoweth, J. G. et al. Sepsis endotypes identified by host gene expression across global cohorts. Commun. Med. 4, 120 (2024).

van Amstel, R. B. E. et al. Uncovering heterogeneity in sepsis: a comparative analysis of subphenotypes. Intensive Care Med. 49, 1360–1369 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Exploring disease axes as an alternative to distinct clusters for characterizing sepsis heterogeneity. Intensive Care Med. 49, 1349–1359 (2023).

Teixeira, J. P. et al. The scientific rationale and study protocol for the DPP3, Angiotensin II, and Renin Kinetics in Sepsis (DARK-Sepsis) randomized controlled trial: serum biomarkers to predict response to angiotensin II versus standard-of-care vasopressor therapy in the treatment of septic shock. Trials 25, 182 (2024).

Slim, M. A. et al. Towards personalized medicine: a scoping review of immunotherapy in sepsis. Crit. Care 28, 183 (2024).

Singh, A. et al. DIABLO: an integrative approach for identifying key molecular drivers from multi-omics assays. Bioinformatics 35, 3055–3062 (2019).

Abdelbaky, A. M., Elmasry, W. G. & Awad, A. H. Restrictive versus liberal fluid regimen in refractory sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus 15, e47783 (2023).

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Prevention and Early Treatment of Acute Lung Injury Clinical Trials Network et al. Early restrictive or liberal fluid management for sepsis-induced hypotension. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 499–510 (2023).

Myles, P. S. et al. Restrictive versus liberal fluid therapy for major abdominal surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 2263–2274 (2018).

Saravi, B. et al. Capillary leak and endothelial permeability in critically ill patients: a current overview. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 11, 96 (2023).

Arora, J., Mendelson, A. A. & Fox-Robichaud, A. Sepsis: network pathophysiology and implications for early diagnosis. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 324, R613–R624 (2023).

Xia, T. et al. Vascular endothelial cell injury: causes, molecular mechanisms, and treatments. MedComm 6, e70057 (2025).

Zhang, Y.-Y. & Ning, B.-T. Signaling pathways and intervention therapies in sepsis. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 6, 407 (2021).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data 10, 1 (2023).

Pollard, T. J. et al. The eICU collaborative Research Database, a freely available multi-center database for critical care research. Sci. Data 5, 180178 (2018).

Gou, E. et al. Association between albumin-bilirubin score and in-hospital mortality in patients with sepsis: evidence from two large databases. Heliyon 10, e34697 (2024).

Thoral, P. J. et al. Sharing ICU patient data responsibly under the Society of Critical Care Medicine/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine joint data science collaboration: the Amsterdam University Medical Centers database (AmsterdamUMCdb) example. Crit. Care Med. 49, e563–e577 (2021).

Xu, P. et al. Critical care database comprising patients with infection. Front. Public Health 10, 852410 (2022).

Gao, S. et al. Effects of ulinastatin on therapeutic outcomes and inflammatory markers in pediatric septic shock patients. Sci. Rep. 15, 16624 (2025).

Jiang, W. et al. ADJunctive Ulinastatin in Sepsis Treatment in China (ADJUST study): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 19, 133 (2018).

Karnad, D. R. et al. Intravenous administration of ulinastatin (human urinary trypsin inhibitor) in severe sepsis: a multicenter randomized controlled study. Intensive Care Med. 40, 830–838 (2014).

Zhou, L., Zhang, W., Shao, M., Wang, C. & Wang, Y. Deciphering the impact of sepsis phenotypes on improving clinical outcome predictions: a multicenter retrospective analysis based on critical care in China. Sci. Rep. 15, 12057 (2025).

Li, N. et al. Unsupervised clustering for sepsis identification in large-scale patient data: a model development and validation study. ICMx 13, 37 (2025).

Hu, C., Li, Y., Wang, F. & Peng, Z. Application of machine learning for clinical subphenotype identification in sepsis. Infect. Dis. Ther. 11, 1949–1964 (2022).

Chenoweth, J. G. et al. Gene expression signatures in blood from a West African sepsis cohort define host response phenotypes. Nat. Commun. 15, 4606 (2024).

van Amstel, R. B. E. et al. Clinical subtypes in critically ill patients with sepsis: validation and parsimonious classifier model development. Crit. Care 29, 58 (2025).

Sweeney, T. E. et al. Unsupervised analysis of transcriptomics in bacterial sepsis across multiple datasets reveals three robust clusters. Crit. Care Med. 46, 915–925 (2018).

Scicluna, B. P. et al. Classification of patients with sepsis according to blood genomic endotype: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 5, 816–826 (2017).

Moore, A. R. et al. International multi-cohort analysis identifies novel framework for quantifying immune dysregulation in critical illness: results of the SUBSPACE consortium. bioRxiv 2024.11.12.623298 https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.11.12.623298. (2024).

Wiersinga, W. J. & van der Poll, T. Immunopathophysiology of human sepsis. EBioMedicine 86, 104363 (2022).

Zhang, Z. zh-zhang1984/CMAISE: identifying septic shock subgroups to tailor fluid strategies through multi-omics integration. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13689848 (2024).

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315, 801–810 (2016).

Zhang, Z. et al. Identifying septic shock subgroups to tailor fluid strategies through multi-omics integration. Nat. Commun. 15, 9028 (2024).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology resource: enriching a GOld mine. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D325–D334 (2021).

Wu, T. et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2, 100141 (2021).

Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 1, 417–425 (2015).

Xie, G. et al. A metabolite array technology for precision medicine. Anal. Chem. 93, 5709–5717 (2021).

Corl, K. A. et al. The restrictive IV fluid trial in severe sepsis and septic shock (RIFTS): a randomized pilot study. Crit. Care Med. 47, 951–959 (2019).

Semler, M. W., Janz, D. R., Casey, J. D., Self, W. H. & Rice, T. W. Conservative fluid management after sepsis resuscitation: a pilot randomized trial. J. Intensive Care Med. 35, 1374–1382 (2020).

Meyhoff, T. S. et al. Restriction of intravenous fluid in ICU patients with septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 2459–2470 (2022).

Macdonald, S. P. J. et al. Restricted fluid resuscitation in suspected sepsis associated hypotension (REFRESH): a pilot randomised controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 44, 2070–2078 (2018).

Li, Y., Zhang, D., Li, H., Wang, Y. & Zhang, D. Effect of timing of norepinephrine administration on prognosis of patients with septic shock: a prospective cohort study. J. Intensive Med. 5, 160–166 (2025).

Monti, S., Tamayo, P., Mesirov, J. & Golub, T. Consensus clustering: a resampling-based method for class discovery and visualization of gene expression microarray data. Mach. Learn. 52, 91–118 (2003).

Rohart, F., Gautier, B., Singh, A. & Lê Cao, K.-A. mixOmics: an R package for’omics feature selection and multiple data integration. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005752 (2017).

Chen, S., Tian, L., Cai, T. & Yu, M. A general statistical framework for subgroup identification and comparative treatment scoring. Biometrics 73, 1199–1209 (2017).

Light, R. J. Measures of response agreement for qualitative data: Some generalizations and alternatives. Psychol. Bull. 76, 365–377 (1971).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by fundings from the China National Key Research and Development Program (No. 2023YFC3603104, ZZ), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82272180, 82472243, ZZ), the Huadong Medicine Joint Funds of the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LHDMD24H150001 (ZZ). A collaborative scientific project co-established by the Science and Technology Department of the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine and the Zhejiang Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (GZY-ZJ-KJ-24082, ZZ), General Health Science and Technology Program of Zhejiang Province (2024KY1099, ZZ), Project of Zhejiang University Longquan Innovation Center (ZJDXLQCXZCJBGS2024016, ZZ), the Key Research and Development Project of Zhejiang Province (2024C03240, ZZ) and Wu Jieping Medical Foundation Special Research Grant (320.6750.2024-23-07, ZZ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

L. Chen and Z. Zhang designed the study and drafted the manuscript; H.S., J.W., J.Y., S.Y., W.Z., X.J., X.W., H.Y., X.S., Y.J., B.L., J.S., and H.N. helped interpret the results and write some discussions; L. Cheng and H.N. performed statistical analysis and result interpretation; X.M., F.Z., W.G., H.Y., L.W., Y.Y. and D.F. performed subject enrollment and sample preparations; M.R.A., P.W.G.E., and K.M.H. conducted a rigorous critical review of the manuscript, contributing invaluable intellectual insights and constructive feedback that substantially strengthened the scientific rigor and clarity of the final work. Z. Zhang is identified as the guarantor of the paper, taking responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Steven Simpson, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Chen, L., Shen, H. et al. Deriving consensus sepsis clusters via goal-directed subgroup identification in multi-omics study. Nat Commun 16, 10328 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65271-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65271-4