Abstract

Block copolymer (BCP) self-assembly – neat, or in a homopolymer/second BCP containing molecular blend – enables complex nanostructures including spherical micelles, co-continuous cubic gyroids and Frank-Kasper phases. Emergent properties in metallic and high entropy alloys inspire a paradigm shift: treating chemically distinct BCP micelles as functional building blocks to pave a path for multicomponent assemblies with molecularly engineered property profiles. Slowing current progress are challenges associated with the structural characterization of such BCP assemblies with poor atomic contrast. Here, we demonstrate how film surface self-assemblies of binary and ternary BCP micelle alloys can be phase inverted to generate porosity. This, combined with machine-learning assisted image segmentation, allows component classification via routine scanning electron microscopy. Results are supported by mechanistic insights from Voronoi analysis, cluster analysis and Monte Carlo/Brownian Dynamics simulations, revealing rich and controllable non-equilibrium surface structural behavior. Such multicomponent materials are expected to enable emergent properties for a range of applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Block copolymer self-assembly (BCP SA) comprises a rich platform for nanoengineered bulk materials and surfaces1,2. Recent advances in synthetic polymer chemistry have expanded upon the accessible architectures and number of compatible blocks/block chemistries3,4, realizing, e.g., complex superstructures5, Frank-Kasper (FK) phases6,7, and the plumber’s nightmare structure8. To circumvent stringent synthetic requirements, blending a BCP with a homopolymer9,10 or second chemically identical (but compositionally variable) BCP11,12 emerges as a promising alternative strategy. These blends generally exhibit mixing on a (near) molecular level (e.g., whereby the homopolymer relieves the packing frustration of the original BCP).

Contrary to the rich history of single-component BCP SA as well as binary BCP/homopolymer13 and BCP/BCP molecular blends14, treatments of BCP micelles as modular, chemically distinct building blocks (essentially “soft colloids”) remain limited15,16. Colloids resemble large “artificial” atoms whose binary (and higher order) mixtures may assume specific crystal structures guided by design rules involving tailored size ratios (\(\alpha\)), interaction potentials (e.g., attractive/neutral/repulsive, hard/soft), and relative compositions17,18,19,20. Soft BCP micelles consist of individual polymer chains collectively assembled into an outer corona and inner core. Their structural variations (e.g., Janus21, multicompartment22, and zwitterionic23 micelles) promise intriguing interaction potentials and multicomponent (N ≥ 2) materials beyond those present in current hard colloidal systems.

To date, exploration of BCP micelle “alloying” has been predominantly theoretical24,25,26, with experimental studies limited to binary mixtures and/or the bulk27,28,29,30. Experimental translation of this concept beyond crystalline structures involves overcoming a substantial hurdle: characterization, in particular of non-periodic structures. Traditional micron sized colloidal assemblies are directly resolvable via optical microscopy18,31, whereas heavy elements in metallic/semiconducting/ magnetic nanoparticle mixtures or superlattices generate contrast under transmission electron microscopy (TEM)17,19,20. Meanwhile, BCP micelles generally have interpenetrating coronas that complicate individual resolution and consist of light elements with limited atomic contrast (e.g., C, N, O). To unlock the full potential of such multicomponent materials and potentially allow them to follow the trajectory of high-entropy materials32,33,34, there is a need for experimental and analytical strategies that enable the characterization of non-periodic features of BCP micelle alloys (BMAs).

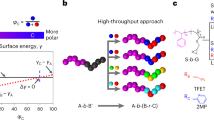

To elucidate the design rules underlying BMA surface nanostructure formation, and to explore whether traditional colloidal systems provide guidance for design and understanding of such experiments, the current work considers model systems comprising three chemically distinct BCPs: poly(isoprene-b-styrene-b-4-vinylpyridine) (PI-b-PS-b-P4VP, ISV), a novel tetrablock quarterpolymer poly(isoprene-b-styrene-b-2-vinylpyridine-b-ethylene oxide) (PI-b-PS-b-P2VP-b-PEO, ISVO; synthetic protocol and characterization in Supplementary Fig. 1), and poly(styrene-b-4-vinylpyridine-b-propylene sulfide) (PS-b-P4VP-b-PPS, SVPS). Characteristics of all BCPs are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. These BCPs are first individually assembled into micellar building blocks in solution (Fig. 1a) and then blended to generate multicomponent (binary and ternary) BMAs (Fig. 1b, c). Large sample numbers and the constituents’ similar elemental compositions (i.e., all BCPs predominantly comprise carbon and nitrogen, with only trace amounts of oxygen (ISVO) and sulfur (SVPS)) would make TEM characterization of such BMAs challenging. Here, we propose an alternative approach to surface structural analysis. We utilize non-equilibrium processing conditions—a combination of solvent evaporation induced self-assembly and non-solvent induced phase separation (SNIPS)—to generate porous BCP micelle surface arrays. Pore size and lattice geometry of the porous top surface domains can then be imaged via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and employed for building block identification (Fig. 1d). Machine-learning (ML) assisted image segmentation techniques—image processing methods that partition a digital image into multiple segments—are used for high throughput object identification (e.g., distinguishing pore space from non-porous, solid matrix or subdividing pore space into individual pore populations, vide infra). This enables streamlined visualization and quantification of surface nanostructures. Therefrom, top surface assembly rules are construed with the assistance of Voronoi analysis (a type of surface tessellation or tiling), cluster analysis, and coarse-grained Brownian Dynamics (BD) simulations. We first apply this approach to the characterization of single-component (ISV, ISVO, or SVPS) derived top surfaces, before advancing to their binary and, subsequently, ternary combinations. This allows us to probe how neutral/repulsive micelle-micelle interactions, solution stoichiometry, size asymmetry, and polydispersity (i.e., traditional colloidal control parameters) impact film surface structure. Findings are ultimately summarized in a ternary surface morphology diagram. Results suggest advanced BCP micelle alloying approaches to nanoengineered surface structures tailorable via traditional colloidal parameters, promising widely tunable property profiles for coatings and other BCP material applications.

a Chemical structures and BCP micellar representations from which pure, binary, and ternary porous films are derived via evaporation induced non-equilibrium BCP self-assembly and non-solvent induced phase separation (SNIPS). Polyisoprene, polystyrene, poly(4-vinylpyridine), poly(2-vinylpyridine), poly(ethylene oxide), and poly(propylene sulfide) blocks are respectively abbreviated as I, S, V (red), V (blue), O, and PS (naming convention: corona|core). Chemically distinct blocks assembled into the same micelle core/corona are depicted in the same color. b SNIPS steps (from left to right): film deposition, doctor blading, evaporation, and plunging into water bath. c Schematic illustrating modular blending of three distinct micellar building blocks (in a) into three binary BMAs and one ternary BMA. Corona interactions: χΑΑN = 0 (left) and χABN » 0 (middle and right), respectively, denote the enthalpically expected absence and presence of local micelle segregation in the resulting BMA films as illustrated. d Porosity introduced as medium for micellar building block identification via differences in pore size and pore lattice geometry on film surfaces.

Results

BCP micelles as soft colloidal building blocks

Figure 1a schematically depicts the three BCP micelle building blocks (ISV, ISVO, SVPS), where colors reflect distinct core and corona chemistries. Figure 1b illustrates individual steps in the SNIPS process: (1) film deposition, (2) doctor blading, (3) evaporation, and (4) plunging into water bath. All BCPs share the same base (> 80 wt.% PS + PVP), allowing a common solvent mixture (tetrahydrofuran and 1,4-dioxane) to be used. At typical BCP concentrations (10 to 20 wt.%), PVP forms the core and PS forms the corona, irrespective of the additional smaller blocks (Supplementary Discussion 1). After film deposition and doctor blading, the binary solvent mixture is evaporated. Rather than evaporation to completion, a particular time point (here: 80 s) is chosen for plunging the film into a water bath. This arrests the film densification process into the glassy state of a high glass-transition temperature matrix (here: polystyrene, PS). The result is therefore a porous, non-equilibrium state. Figure 1c illustrates how BMA surface nanoarchitectures can be tailored by coupling microphase separation in a single BCP micelle with local (sub-μm) segregation amongst chemically distinct micelles. Binary BMAs comprise one n-BMA (neutral-BMA; left) reference case (ISV + ISVO) displaying neutral interactions between the chemically identical corona blocks (χIS-IS = 0, therefore χN = 0, where χ is the Flory-Huggins interaction parameter and N the degree of polymerization), and two r-BMA (repulsive-BMA; middle) cases (ISVO + SVPS and ISV + SVPS) expected to exhibit local segregation due to enthalpic repulsion between the ISV(O) isoprene block and the SVPS styrene block (χI-S > 0, χI-SN » 0; Supplementary Table 1 lists N values). Micelle coronas are assumed to shield the core blocks from contributing here. Using unique BCP signatures (e.g., pore size and/or lattice size and geometry; Fig. 1d)—dependent on number average molar mass (Mn) and block volume fractions—the building block distribution can be read from the final film surface (vide infra). Insights from the binary surface assemblies are then applied to understanding ternary ISV + ISVO + SVPS BMA assemblies (Fig. 1c, right).

Surface SEM micrographs of pure ISV121 (Fig. 2a), ISVO165 (Fig. 2b), and SVPS53 (Fig. 2c) films (subscripts denote Mn in kg mol−1; see Supplementary Table 2 for solution compositions) convey high contrast between the pores (dark gray/black) and the solid matrix (light gray). A fully evaporated dense film would lack such pore derived contrast, highlighting a benefit of employing non-equilibrium processing conditions to characterize BMA surface nanostructures. To discern structural features for reliable building block distinction in binary and ternary BMAs, the SEM images were segmented into two classes (pore + matrix) with a random forest ML algorithm using the Trainable Weka Segmentation (TWS) Fiji plugin35,36 (Fig. 2d–f, “Methods”). Pores were colored to reflect the micelle core chemistries they originated from (ISV: red, ISVO: blue, SVPS: green), while the solid matrix was depicted in magenta, irrespective of corona chemistry. Figure 2h shows the surface pore size distributions (PSDs) of pure ISV121 (20.2 ± 3.2 nm), ISVO165 (24.6 ± 3.7 nm), and SVPS53 (15.0 ± 2.6 nm; full dataset in Supplementary Fig. 2). Segmented images were then subjected to Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis to extract lattice parameters, thereby modeling scattering experiments on our surface structures (Fig. 2i; “Methods”). ISV121 and ISVO165 lattices were both consistent with a 2D square geometry—the higher Mn ISVO165 BCP formed the larger lattice (55.6 nm vs. 42.5 nm)—supporting the assumption that the additional PEO block likely does not affect the V-core micelle structure (Supplementary Discussion 1). Conversely, SVPS53 formed a 26.0 nm lattice consistent with 2D hexagonal geometry. Thus, ISV121 and ISVO165 are best identified by their pore and/or lattice sizes, whereas SVPS53 can be detected by lattice geometry. To complement and rationalize experimental results, micelles were coarse-grained in BD simulations as spherical colloidal particles exhibiting the same packing geometries as their experimental counterparts (Fig. 2g; “Methods” and Supplementary Figs. 3–5). Relative particle sizes were approximated by the averages of the experimental PSDs (i.e., monodisperse populations of “average” sized particles; see Supplementary Table 3 for derived simulation scaling factors), unless otherwise stated. Additional experiments confirm negligible cross-population micelle chain exchange on the timescale of film casting due to large micelle core block size, relatively concentrated solutions, and room temperature processing (see “Methods”, Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7 and Supplementary Discussion 2), validating this degree of coarse-graining and, fundamentally, the micelle-as-building block treatment.

a–c Top surface SEM micrographs and d–f, derived segmentations of pure (a, d) ISV121, (b, e) ISVO165, and (c, f) SVPS53 films evaporated for 80 s. Red, blue, green, and magenta pixels respectively represent ISV, ISVO, SVPS pores, and the solid matrix. Insets depict enlarged 250 × 250 nm regions highlighting the individual lattice geometries. g A coarse-grained ISV micelle, alongside enlarged Brownian Dynamics (BD) simulation box surface snapshots of square-packed (red) and hexagonally packed (green) single-component systems. h Pore size distributions (PSDs) of pure ISV121, ISVO165, and SVPS53 film surfaces derived from the segmentations in (d–f). i Fast Fourier transform (FFT) image analysis of (d–f) with lattice spacings derived from the first peak positions (q*) as labeled. Tick marks accompanying the ISV and ISVO traces correspond to (q/q*)2 = 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, and 10, consistent with a 2D square lattice. Tick mark for SVPS trace correspond to (q/q*)2 = 1, 3, 4, and 7, consistent with a 2D hexagonal lattice.

Stoichiometry and interaction potential tailor surface structure in binary BMAs

Solution stoichiometry provides a rational and accessible means of tailoring multicomponent structures. To start, ISV121 + ISVO165 n-BMA surfaces were probed for composition and local segregation. Films comprising ISV121:ISVO165 weight ratios of 75:25 and 50:50 (rounded to the nearest multiple of 5; exact weight ratios in Supplementary Table 2) were evaporated for 80 s, phase inverted, and surface characterized via SEM (Supplementary Fig. 8b, c). Following two-class segmentation (pore-matrix; “Methods” and Supplementary Fig. 9), the pores were nominally classified as ISV121 (red) and ISVO165 (blue) based on a 24.5 nm threshold (e.g., diameter ≥ 24.5 nm → ISVO165; for details and rationale, see Supplementary Fig. 9). Surprisingly, surface compositions (by number) of the stoichiometrically distinct n-BMAs (75:25 vs. 50:50 ISV121:ISVO165; Fig. 3a, b) exhibited no substantial differences (82:18 ± 2 vs. 77:23 ± 2 ISV121:ISVO165), and further adjusting the solution to 25:75 ISV121:ISVO165 by wt. still yielded an ISVO-poor surface (64:36 ± 1 ISV121:ISVO165, Supplementary Fig. 8d). This depletion effect persisted following statistical corrections for segmentation and thresholding choices (Supplementary Fig. 8h and Supplementary Discussion 3). Increasing deviation from solution stoichiometry with ISVO165 solution abundance (Supplementary Fig. 8h) suggests slowing system dynamics, supported by dynamic light scattering (DLS) correlograms (Supplementary Fig. 10a) derived from diluted solutions (3 wt.%). The order-of-magnitude slower dynamics of ISVO165 allows ISV121 to outcompete its surface assembly (for further in-depth discussion, see Supplementary Discussion 4). Despite this, the near-stoichiometric FFT derived lattice spacings (Supplementary Fig. 8g and Supplementary Table 4) confirm the presence of the larger ISVO micelles in the film. Solution stoichiometry, therefore, presents an experimental dial that can be used to tune the lattice size of two chemically distinct micelle building blocks sitting on a single lattice. Note that this FFT analysis was performed on the combined ISV121 + ISVO165 lattice, distinct from the split-component FFT analysis discussed below.

Top surface SEM image derived segmentations of binary a, b ISV121 + ISVO165, c, d ISVO165 + SVPS53, and e, f ISV121 + SVPS53 BMAs evaporated for 80 s. Red, blue, green, and magenta pixels, respectively, represent ISV121, ISVO165, SVPS53 pores, and the solid matrix. Compositions by wt. as labeled following the same color code. The larger non-porous spaces in (a and b) are a result of image processing (“Methods”). g–l BD simulation box surface snapshots of binary BMAs at the labeled wt. compositions. Each pair of snapshots (e.g, g and h) reflects the same simulation time (“Methods”). FFT image analysis of 75:25 m ISV121: ISVO165, n ISVO165: SVPS53, and o ISV121: SVPS53 samples (by wt.) was performed after the populations were split (“Methods”). FFT traces from split populations are sandwiched between those of the corresponding pure samples (top and bottom in m–o). Vertical reference lines—corresponding to first four peak positions of the uppermost trace—serve as visual aids.

ISV121 + ISVO165 n-BMAs were then analyzed for signs of local segregation, here defined as the coexistence of two distinct lattice sizes or geometries on the film surface. To that end, split-component FFT curves derived from segmentation results in Fig. 3a were compared against the respective pure component FFT curves (Fig. 3m). The presence of just a single, intermediate lattice size amongst the two blend components (d = 46.9 ± 0.5 nm; compare with ISV: d = 42.8 ± 0.8 nm and ISVO: d = 55.7 ± 1.3 nm) suggests the absence of significant size based segregation (i.e., the building blocks randomly occupy sites of a common square lattice)37. The BD simulation snapshot of the 75:25 ISV121:ISVO165 n-BMA surface (Fig. 3g) shows mid-grain (vs. grain boundary) insertion of minority ISVO165, echoing experimental observations. Interestingly, the simulated 50:50 ISV121:ISVO165 n-BMA surface (Fig. 3h) exhibits compositional variation from Fig. 3g, inconsistent with experiment. This is potentially linked to the evened out dynamic behavior from the large degree of coarse-graining. Minor size-dependent component clustering observed in the simulations (one to three particles wide) is not considered local segregation according to the present definition.

In contrast to the binary ISV121:ISVO165 n-BMA surfaces, those of the binary ISVO165:SVPS53 r-BMAs exhibit visible local segregation (Fig. 3c, d; see Supplementary Fig. 11 for raw SEM micrographs and “Methods” for three-class segmentation details), as expected from their repulsive coronal interactions (χIS-SN » 0). Surface compositions suggest positive correlation with solution stoichiometry (44:55 ± 3 and 22:78 ± 1 ISVO165:SVPS53 for Fig. 3c, d, respectively). These features are to a lesser extent echoed in the BD simulations (Fig. 3i, j). Figure 3n confirms the distinct ~58 nm and 27 nm lattices, respectively, formed by the blue ISVO and green SVPS components, consistent with local segregation. Note that this reflects a non-equilibrium, arrested thermodynamic state that would otherwise be expected to evolve towards traditional macrophase segregation, as observed by 2D equilibrium Monte Carlo (MC) simulations (vide infra). Slow system dynamics, short processing times, and potentially the compatibilization of the chemically distinct coronas (PI + PS vs. PS) via the common PS block confine the experiments to a sub-μm segregated state conducive to tailoring nanostructures and properties38 (vs. a state of macroscopic segregation). The disordered nature of the ISVO component, marked by the lack of higher-order FFT peaks and visually evident in Fig. 3c, d, precludes confirmation of distinct lattice geometries. Considering the system’s higher mobility as compared to that of ISV121 + ISVO165 (compare relative positions of ISV121 and SVPS53 curves in Supplementary Fig. 10a), the structural disorder is puzzling. This can, however, be rationalized by thinking of the smaller, more mobile components as structure-directing agents. ISV and ISVO individually assume the same 2D square lattice geometry and have no enthalpic drive to segregate. Therefore, assembly of the former prompts that of the latter. Conversely, SVPS and ISVO prefer distinct lattice geometries (hex. vs. square), and therefore efficient assembly of the former traps the latter in a disordered state due to ISVO’s limited mobility in the presence of two competing “forces”: (i) taking on its inherent square packing and (ii) assimilating into the SVPS’ hex. packing.

This hypothesis was probed via ISV121 + SVPS53 r-BMAs—more mobile executions of the ISVO165 + SVPS53 r-BMAs. Like before, experiments (Fig. 3e, f; see Supplementary Fig. 11 for raw SEM micrographs) and BD simulations (Fig. 3k, l) both exhibit local segregation. Now, however, the components’ more similar mobilities (Supplementary Fig. 10a) allow both to assume their native lattice geometries (Fig. 3o). Notably, the SVPS53 lattice size (29.5 nm) is larger than it is in the prior ISVO165 + SVPS53 r-BMAs (27.1 nm) and in pure SVPS53 (26.0 nm). The strain field set up by the larger, highly ordered 43.8 nm ISV lattice could be prompting the soft SVPS coronas to expand and assimilate, an effect perhaps more subdued in the presence of the disordered ISVO lattice.

Micelle size asymmetry and dispersity tune surface composition in binary r-BMAs

r-BMA surface structures have thus far convoluted BCP chemistry (ISVO + SVPS vs. ISV + SVPS) and size asymmetry (\(\alpha\) = Mn,ISV(O)/Mn,SVPS). To isolate effects of the latter, 75:25 ISV:SVPS r-BMA solutions with \(\alpha\) = 1.8–3.1 were evaporated for 80 s, and characterized via SEM (see Supplementary Fig. 11 for raw SEM images). Figure 4a–d shows that SVPS surface prevalence increases with α. Surface coverage with two different surface energy entities (PI + PS for ISV vs. PS for SVPS; γPI = 32 mJ m−2 and γPS = 40 mJ m−2)39 points towards non-equilibrium structures frozen under evolving environmental conditions (e.g., where initial conditions favor X, final conditions favor Y, but the system is deliberately frozen prematurely). As discussed elsewhere, during ambient solvent evaporation from a polymer film surface, evaporative cooling increases local relative humidity—sometimes to the point of condensation—steadily replacing the polymer-air interface with a polymer-water vapor interface40. While initial interfacial conditions favor ISV (γPI < γPS; vide supra), final conditions favor SVPS (θwater-PI ~ 102° > θwater-PS ~ 88°)41, prompting environment-induced structural re-equilibration42. Considering the semi-concentrated nature of SNIPS casting solutions43, the surface prevalence of SVPS becomes a measure of its surface accessibility. With increasing size asymmetry, the smaller entity (SVPS) more readily inserts itself into the interstices of the lattice formed by the larger entity (ISV)44, leading to a positive correlation between \(\alpha\) and SVPS surface composition (Fig. 4e). Modified Voronoi analysis (MVA; “Methods” and Supplementary Fig. 12) of the segmentation derived pore centroids showed diminishing fourfold (ISV) correlation length with larger \(\alpha\) (Supplementary Fig. 13), consistent with expectation and segmentation results. This trend with size asymmetry persists even when SVPS surface composition is normalized to its mol.% (as opposed to wt.%) in solution (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Micelles outlined in the same color (top) are derived from the same BCP (e.g., ISV micelles depicted for \(\alpha\) = 1.8 and \(\alpha\) = 2.3). SEM derived object-based segmentations of a ISV121 + SVPS67, b ISV121 + SVPS53, c ISV138 + SVPS53, and d ISV164 + SVPS53 film surfaces evaporated for 80 s, all made from 75:25 ISV:SVPS (by wt.) solutions blended for 15 min. Red, green, and magenta regions, respectively, represent ISV, SVPS, and the solid matrix. \(\alpha\) denotes BCP size ratio (Mn,ISV/Mn,SVPS). e Quantitative comparison between outcomes of segmentation (s) and modified Voronoi analysis (MVA or v). Averages and standard deviations from three separate regions reported. For MVA, the following correspondence between classification and number of cell edges (nearest neighbors, N) was used: ISV (N = 4), SVPS (N = 6), defect (Def; N ≠ 4 or 6). f–h Monodisperse and j–l polydisperse BD simulation surface snapshots corresponding to size asymmetries of \(\alpha\) = 2.3, 2.6, and 3.1, respectively (“Methods”). i Approximation of BD simulation polydispersity via relative frequencies of five discrete populations (as labeled) derived from the experimental pure film PSD.

To substantiate the surface accessibility argument, BD simulations reflecting the \(\alpha\) = 2.3, 2.6, and 3.1 ISV + SVPS r-BMAs were conducted (Fig. 4f–h). The \(\alpha\) = 1.8 system was excluded to keep one constituent (SVPS53) constant. As evident, monodisperse colloidal particles reflecting average pore sizes do not capture the experimental trends in Fig. 4b–d, due to the marginally smaller pore size of ISV138 (19.9 nm) vs. that of ISV121 (20.2 nm; Supplementary Fig. 2). Nonetheless, these simulations do highlight that greater size asymmetry improves SVPS surface accessibility (i.e., the r-BMAs with the smallest/largest average ISV pore size have the least/most SVPS surface presence). Ordered lattice formation kinetics of ISV could also be modulating SVPS surface accessibility (e.g., fast lattice formation would deter surface penetration). In hard sphere colloids, increased size polydispersity can fully suppress ordered lattice formation45. While packing restrictions of polydisperse soft colloids are likely less stringent, minor differences in lattice formation kinetics could still impact SVPS surface accessibility. Approximating size polydispersity by the second moment of the PSD (i.e., the standard deviation, \(\sigma {;}\) Supplementary Fig. 2a–c), it is evident that polydispersity increases with Mn for the three ISV BCPs studied. The observed trend remains following “polydispersity” normalization via the coefficient of variation (σ/μ). To probe the effects of polydispersity in a computationally feasible manner, experimental PSDs were approximated as weighted combinations of five discrete populations (Fig. 4i; see Supplementary Table 5 for simulation scaling factors). BD simulation box snapshots of the corresponding polydisperse assemblies are shown in Fig. 4j–l (quantitative data in Supplementary Fig. 15)—now conforming to the experimental trends—suggesting that the experimental outcomes are likely a convolution of size asymmetry and r-BMA size polydispersity.

Trends observed in binary BMAs inform behavior of associated ternary BMAs

Following detailed n-BMA and r-BMA surface analyses, we wanted to see whether trends observed there would similarly apply to ternary ISV121 + SVPS53 + ISVO165 BMAs. Here, one question of interest was whether the stoichiometric variance of ISV121:ISVO165 (i.e., tuning the size of their shared lattice; vide supra) could modulate the effective size asymmetry, and thus surface structure, of the ternary system (i.e., generating a ternary analogue of Fig. 4a–d). Ternary BMA solution compositions (Fig. 5e) were chosen to ensure sufficient surface representation of each population. Resulting SEM segmentations are presented in Fig. 5a–c (raw SEM images in Supplementary Fig. 11). Four-class segmentations (3 building blocks + solid matrix) combined prior two- and three-class segmentation methods: components were first classified as SVPS, non-SVPS, or matrix (three-class segmentation), after which non-SVPS components were split into ISV and ISVO based on the 24.5 nm size threshold (“Methods” and Supplementary Fig. 7). Echoing ISV-ISVO n-BMAs, surface depletion of ISVO was common across various solution stoichiometries (Supplementary Table 2). FFT analysis of the non-SVPS components (Fig. 5d) confirms tailorability of the 2D square-packed lattice sizes, though these are smaller than would be expected from a binary ISV + ISVO n-BMA with the same ISV:ISVO ratio (e.g., compare weighted averages, 46.6, 49.3, and 52.0 nm, for ISV:ISVO compositions in Fig. 5a–c, respectively, with the values listed in Fig. 5d). This result highlights the soft colloidal nature of BMAs (e.g., expansion and compression of micelle coronas per the colloidal “soup” composition). To quantify how vulnerable different sized square (fourfold symmetry) lattices are to SVPS disruption, cluster analysis was performed on the entire pore coordinate array to detect clusters with high local Φ4 (fourfold) orientational order (“Methods” and Supplementary Fig. 16). Figure 5f–h respectively depicts the ten largest fourfold clusters detected in Fig. 5a–c, while Fig. 5i statistically summarizes the size distribution of the ten largest clusters across three sample regions (30 clusters per sample). Mean and median cluster sizes decrease with increasing effective size asymmetry (i.e., from Fig. 5a–c), consistent with an increased tendency for SVPS to insert itself interstitially as was observed for binary ISV-SVPS r-BMAs. Substantial ISV/ISVO surface presence despite (i) increasing effective size asymmetry (compare Fig. 4c, d to Fig. 5a–c) and (ii) system size polydispersity compared to the binary BMAs (as the square lattice comprises both ISV121 and ISVO165), could be explained by the substantial ISVO165 solution concentration. ISVO165, with its drastically slower dynamics (Supplementary Fig. 10), is likely preventing the timely response of ternary BMAs to the changing interfacial environment.

a–c SEM segmentations of ternary ISV121:SVPS53:ISVO165 film surfaces (relative compositions as labeled) evaporated for 80 s. Red, green, blue, and magenta regions represent ISV, SVPS, ISVO, and the solid matrix, respectively (“Methods”). d FFT image analysis of the ISV and ISVO regions (red and blue, collectively) in (a–c). Lattice spacing derived from the position of the first peak (q*) as labeled. Vertical reference lines reflect expected peak positions up to (q/q*)2 = 1, 2, 4, and 5 for a 2D square lattice with 46.3 nm spacing, highlighting the compositionally dependent lattice expansion. e Relative solution compositions of (a–c) by wt. depicted on a ternary ISV-SVPS-ISVO phase diagram. f–h \({\varPhi }_{4}\) cluster analysis of (a–c), respectively, with ten largest detected clusters shown. Pores in the same cluster depicted in the same color (“Methods”). i Box-and-whisker plot summarizing \({\varPhi }_{4}\) cluster analysis statistics. Statistics for the 10 largest detected clusters from three separate 2500 × 2500 nm regions (i.e., 30 clusters per sample composition; see overlaid scatter plot) were reported, with means and medians as shown. Data points outside 1.5× the interquartile range depicted as outliers (hollow circles).

Outcomes of binary and ternary BMAs are summarized in a ternary surface morphology diagram (Fig. 6). Multicolored circles reflect relative surface compositions of the three building blocks in each BMA sample (see Fig. 6 inset), and regional color-coding the majority surface component following 80 s of evaporation. As depicted (by component wt. fraction), the smallest (SVPS53)/largest (ISVO165) building blocks respectively dominate the largest/smallest compositional regions. To assess how far these experimental snapshots deviate from equilibrium, 2D equilibrium MC simulations (“Methods”)—with numerical component ratios reflecting the experimental surface compositions—were conducted as points of comparison (Fig. 6a–d). Structurally, n-BMAs closely resemble equilibrium structures (compare Fig. 6a and Fig. 3b), whereas r-BMAs (Fig. 6b–d) do not (e.g., compare Fig. 6b and Fig. 3f). Equilibrium structures of the latter display further segregation (akin to macrophase separation) than do their experimental counterparts, consistent with film phase inversion (structural freezing) following a short evaporation period (80 s)—insufficient time for equilibration. r-BMAs demonstrate the nano-structural tailoring and diversification accessible via non-equilibrium processing of “active” colloidal assemblies.

Experimental non-equilibrium ISV121-SVPS53-ISVO165 ternary surface morphology diagram of BMA surface compositions (\({f}_{n}\); Supplementary Table 2) following 80 s of evaporation. Each sample is denoted by a two- or three- colored circle, whose position and color reflect the relative solution (wt. %) and surface (number %) compositions, respectively. Surface compositions derived from averages of three separate 2500 × 2500 nm experimental sample regions. Regions of surface morphology diagram shaded to reflect majority surface component. a–d 2D equilibrium Monte Carlo (MC) simulation snapshots whose number fractions correspond to the surface compositions of the experimental samples (as labeled).

Discussion

We demonstrated how binary and ternary “alloys” of chemically distinct BCP micelles could be—upon solvent evaporation induced assembly—treated as soft colloids whose surface structures are tailorable via traditional colloidal parameters (e.g., solution stoichiometry, neutral/repulsive colloidal interactions, size asymmetry, and size polydispersity). Film porosity derived from a non-equilibrium synthetic technique was used in conjunction with ML-assisted image segmentation analysis to overcome the lack of atomic contrast in multicomponent polymeric systems that generally complicates component differentiation. BD simulations were employed to test mechanistic surface structure formation hypotheses and untangle associated complex experimental phenomena. An 80 s evaporation time was chosen to generate multicomponent surface structures that showcase the classification abilities of the techniques described in this work (e.g., ML-assisted image segmentation, Voronoi analysis, and cluster analysis). Together, these techniques unveiled the following surface design rules for BMAs: (i) the lattice size of binary n-BMAs (where Mn,1 ≠ Mn,2) individually forming geometrically identical lattices can be modulated by composition; (ii) surface compositions of binary r-BMAs can be tuned via micelle size, asymmetry and dispersity; (iii) trends observed in binary BMAs inform behavior of associated ternary BMAs.

BCP micelle “alloying” (BMA), i.e., the treatment of chemically distinct BCP micelles as soft colloids, remains largely unexplored. As advocated in the introduction, this is largely due to difficulties in such multicomponent soft nanomaterials characterization. The current experimental surface structure formation study suggests that these limitations can likely be overcome via progressive development in experimental and computational methods. For example, it would be desirable to go beyond the top surface discussed here and reveal whether sub-surface layers mirror its structure and order. Continuous advances in X-ray ptychography have recently enabled large-volume reconstruction of self-assembled BCP structures46. Backfilling the ordered pores of BMAs with inorganic materials exhibiting higher electron density contrast and stability may help such efforts. Alternatively, one could subject BMA film surfaces to controlled reactive ion etching gradients and analyze resulting depth-dependent SEM images via ML-assisted image segmentation.

Results of the current study show that surface structures are tailorable via traditional colloidal control parameters, consistent with BD simulations treating the BCP micelles as soft colloids. This further suggests that the SNIPS induced top surface porosity may not substantially alter key structural aspects of the micellar (colloidal) surface assembly relative to BCP micelle film surfaces generated without the SNIPS quenching step. The former may therefore be used as a simpler-to-analyze approximation of the latter. Multicomponent soft colloidal systems then promise substantial progress scientifically (e.g., in our fundamental understanding of non-equilibrium and equilibrium surface and bulk structure formation) and technologically (e.g., towards emergent properties for applications spanning coatings, microelectronics, and membrane-based separations all the way to self-healing). As BCP micelle alloying should be applicable to numerous simple-to-obtain mixtures of chemically distinct BCP micelles, this concept opens the door to widely tailorable property profiles.

Methods

Materials

1,4-dioxane (DOX, Sigma-Aldrich, anhydrous, 99.8%), tetrahydrofuran (THF, Sigma-Aldrich, anhydrous, > 99.9%), chloroform (Macron Fine Chemicals, ≥ 99.8%), sec-butyllithium (sec-BuLi, Sigma-Aldrich, 1.4 M solution in cyclohexane) and potassium chloride (Alfa Aesar, now Thermo Scientific Chemicals, ultra dry, 99.95%) were used as received. For anionic polymerization, the following chemicals were used after purification: benzene (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥ 99.9%), tetrahydrofuran (Fisher Chemical, OptimaTM for HPLC), isoprene (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%) and ethylene oxide (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.5%) were distilled over n-butyllithium (n-BuLi, Acros Organics, now Thermo Scientific chemicals, 1.6 M solution in hexanes) at room temperature; 1,1-diphenylethylene (DPE, Thermo Scientific Chemicals, 98%) was distilled over n-BuLi at 110 °C; styrene (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥ 99%) was distilled over di-n-butylmagnesium (Sigma-Aldrich, 1 M in ether and hexanes); 4-vinylpyridine (4VP, Acros Organics, now Thermo Scientific Chemicals, 95%) was distilled over ethylaluminum dichloride (Sigma-Aldrich, 1.0 M in hexanes); 2-vinylpyridine (2VP, Sigma-Aldrich, 97%) and propylene sulfide (Merck, 96+%) were dried over calcium hydride (CaH2, Alfa Aesar, now Thermo Scientific Chemicals, 90–95%) overnight prior to distillation. Methanolic HCl (Supelco, 3 M HCl in methanol) was degassed prior to use. Deionized (DI) water (18.2 MΩ-cm) was freshly generated with a Barnstead water system directly before use as a non-solvent bath.

Experimental and image processing methods

Polymer synthesis and characterization

Triblock terpolymers poly(isoprene-b-styrene-b-4-vinylpyridine) (PI-b-PS-b-P4VP, ISV) and poly(styrene-b-4-vinylpyridine-b-propylene sulfide) (PS-b-P4VP-b-PPS, SVPS) were synthesized using established sequential anionic polymerization techniques47,48. For the synthesis of ISV, the polymerization of isoprene was initiated by sec-BuLi in benzene at room temperature. After 6 h, an aliquot was taken and terminated for GPC analysis. Distilled styrene was then added to the reactor and allowed to react overnight. Thereafter, living anionic chains were capped with DPE by adding a 10× molar excess (relative to sec-BuLi) before benzene was exchanged for THF through successive distillations. The reactor was cooled to −78 °C and 4VP was added. After 1.5 h, the PI-b-PS-b-P4VP chains were quenched with degassed methanol. The synthesized polymer was worked up by removing THF via rotary evaporator, redissolving in chloroform and precipitating into methanol before vacuum drying at 50 °C for 48 h. The synthetic procedure for SVPS had the following modifications: (1) polymerization of styrene was initiated by sec-BuLi in benzene at room temperature and allowed to react overnight before an aliquot was terminated for quantitative analysis; (2) following the 1.5 h growth of the P4VP block, distilled propylene sulfide was added at −78 °C, and the reactor was allowed to warm up under ambient conditions for 1.5 h before the PS-b-P4VP-b-PPS chains were quenched with methanolic HCl. The novel tetrablock quarterpolymer poly(isoprene-b-styrene-b−2-vinylpyridine-b-ethylene oxide) (PI-b-PS-b-P2VP-b-PEO, ISVO) was synthesized for the first time by adapting the ISV synthesis as follows. Following the solvent change from benzene to THF, the reactor was cooled to −78 °C and 2VP was added. After 1.5 h, the PI-b-PS-b-P2VP chains were end-functionalized with excess ethylene oxide before quenching with methanolic HCl (forming PI-b-PS-b-P2VP-OH, ISVOH). After THF was removed via rotary evaporator, the ISVOH was redissolved in chloroform and washed with water three times before being precipitated in methanol. The vacuum dried (48 h at 50 °C) polymer was redissolved in THF, followed by the addition of excess potassium chloride. Re-initiation of PI-b-PS-b-P2VP-OH was achieved through the addition of potassium naphthalenide. Distilled ethylene oxide was added and allowed to react for 4 days at 50 °C before the resulting polymer was quenched with methanolic HCl and worked up as previously described for ISVOH. All synthetic products were quantitatively characterized using a combination of THF gel permeation chromatography (GPC, Waters, equipped with a 410 differential refractive index detector) and 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectroscopy (Bruker AV-500, solvent: CDCl3). For a summary of all individual BCP characteristics see Supplementary Table 1.

Porous film preparation via SNIPS

Single and multicomponent porous films were generated via the combination of solvent evaporation induced block copolymer (BCP) self-assembly with non-solvent induced phase separation, also referred to as SNIPS47,49. To that end, BCP solutions (60–150 μL depending on viscosity) were pipetted onto glass substrates and spread into thin films by an automated blade casting system comprising a casting knife (Elcometer) and a step-motor-controlled stage (Velmex, Inc.) situated in a humidity-controlled dry box. For solutions containing ISVO, a 25 mm diameter hydrophilic polyester substrate (0.2 μm pore size, Sterlitech) was placed atop the glass substrate for additional mechanical stability. Before each cast, gate height was manually adjusted to 0.203–0.229 mm and dry box relative humidity purged to 40–45% (ambient temperature 18–20 °C) with dry nitrogen gas. The step motor was programmed to (1) cast at 1185 spins per second (15 mm s−1) and (2) allow for 80 s of preferential solvent evaporation, driving BCP self-assembly into ordered lattices near the film surface, before (3) submerging the partially evaporated film into a non-solvent DI water bath ( ~ 5 L) to precipitate out the polymer. Resulting film thickness after complete drying was typically of order 40–50 microns. Selective evaporation of corona-selective THF over core-selective DOX leads to an asymmetric solvent distribution in the post-evaporated film (i.e., solvent-swollen cores amidst denser, solvent-poor coronas). For a detailed discussion of how evaporation in binary solvent systems studied here maps onto composition and associated phase transformations of BCP micelle systems in the top surface layer of such films, the interested reader is referred to earlier model studies of ISV in THF/DOX binary solvents50,51. The subsequent exchange of solvent for non-solvent by inserting the films into a water bath essentially stops the regular evaporation process, which would otherwise lead to a dense film. This causes the core chains to retract and collapse against the corona chains, generating pores, which in turn facilitate structure analysis (vide supra). From earlier analysis, we know, however, that this solvent exchange essentially maintains the associated lattices (e.g., hexagonal versus cubic) formed during evaporation. Following precipitation ( ~ 5 min), films were dabbed dry and prepared for subsequent characterization. All solutions were prepared by individually dissolving respective BCPs in a DOX/THF mixture (detailed concentrations and solvent compositions in Supplementary Table 2) and ambiently stirring at 300 rpm for a minimum of two hours. For multicomponent (N ≥ 2) BMAs, said BCP solutions were combined by weight and allowed to ambiently stir at 200 rpm for 15 min. prior to casting. Mixing time was chosen to minimize degree of inter-micellar chain exchange (e.g., chain exchange between an ISV and SVPS micelle) as outlined in Supplementary Discussion 2. To demonstrate that 15 min. « the timescale of chain-exchange, a 60:40 ISV121:SVPS67 solution was stirred for 15 min, after which 100 μL was cast according to the above protocol. The remaining solution was sealed via parafilm and stirred at 200 rpm for 3 more days, at which point a further 100 μL was cast.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) characterization

Porous films (evaporated top surface facing upwards) were affixed to flat SEM stubs with double-sided carbon tape. To minimize effects of charging, material edges were painted with conductive carbon adhesive before samples were sputter coated with Au-Pd (7 s, Denton Desk II vacuum sputter coater). Surface imaging was performed on a Tescan Mira3 FESEM (5 kV accelerating voltage) equipped with an in-lens secondary electron detector. For a detailed description of an SEM imaging based pore modeling approach characterizing pores in film subsurface domains, the interested reader is referred to an earlier study52.

SEM image analysis

All image analysis was performed using the FIJI distribution of ImageJ236. Unless otherwise stated, sample statistics (e.g., averages and standard deviations) were derived from three separate 2500 × 2500 nm sample regions. As a first step in isolating the regions of interest (pore space) from the solid matrix, images were bandpass filtered (3 <pixels <40), autoscaled, and saturated (e.g., Supplementary Fig. 7a, g, k). Images were then imported into the TWS plugin for pixel-based segmentation35.

Pixel-based segmentation

For single-component (e.g., pure ISV) and binary neutral-BMA (n-BMA) ISV121 + ISVO165 samples, the interactive user interface was used to manually label select sample regions as either pore space or matrix based on visual identification. Default segmentation settings were used to train a FastRandomForest classifier (200 trees and 2 random features per node; random features: Gaussian blur, Sobel filter, Hessian, difference of Gaussians, and membrane projections). More sample regions were iteratively labeled until reasonable segmentation results were achieved (as determined by the user). Images stemming from the same (combination of) BCPs were segmented using the same trained classifier. To remove image artifacts (regions erroneously classified as pore space due to minor intensity perturbations), objects < 78.54 nm2 (10 nm diameter, assuming perfect circularity) were removed for all segmentations. For visualization purposes, images were color coded, with red, blue, green, and magenta pixels representing ISV, ISVO, SVPS, and matrix domains, respectively (see Fig. 2d–f). For ISV121 + ISVO165 n-BMAs, visual inspection revealed that the segmentation had picked up on domains not part of the primary 2D square lattice (lattice spacing > 40 nm; see Supplementary Fig. 9d inset and associated description). To aid FFT analysis in capturing the effects of blend composition (i.e., x% ISV121 + (100-x)% ISVO165) on primary lattice spacing, an attempt was made to systematically remove these non-primary domains according to certain nearest neighbor distance (NND) and domain size criteria. The NND distribution of ISV121 (the smaller of the BCP pair; Supplementary Fig. 9b) was used as a reference (nearest neighbor distance plugin for FIJI written by Yuxiong Mao, Mississippi State University) when designating the minimum NND cut-off (NND = 35 nm). To differentiate between the primary and non-primary domains fulfilling the above NND criterion, a 14 nm domain size threshold was chosen based on trial-and-error. Domains removed due to these criteria are outlined in red (Supplementary Fig. 9e). While this approach was conservative in nature (i.e., it did not remove all non-primary domains), the improvement was sufficient for subsequent FFT analysis. Classification of the remaining ISV121 + ISVO165 sample domains as either ISV or ISVO was realized by applying a size threshold of 471.44 nm2 (24.5 nm diameter, assuming perfect circularity; Supplementary Fig. 9f) derived from the domain size distributions of pure ISV and pure ISVO films. Statistics suggest that, on the experimental timescale (« the timescale for chain-exchange), over 90% of the domains in the binary blend exceeding this threshold would be ISVO (Supplementary Fig. 9a).

For binary and ternary repulsive-BMAs (r-BMAs) displaying evidence of local segregation (e.g., the presence of two distinct lattice spacings or lattice geometries), the interactive user interface was used to manually select traces of three classes (ISV(O), SVPS, and matrix) for classifier training. When selecting representative traces, ISV(O) and SVPS domains were visually identified on the bases of domain size (ISV(O) > SVPS), lattice geometry (2D square vs. 2D hexagonal), and/or pixel value (ISV(O) domains were closer to the black end of the spectrum; see Supplementary Fig. 7a, g). Traces were iteratively added until satisfactory segmentation results (e.g., Supplementary Fig. 7b, h) were achieved. Supplementary Fig. 7c highlights the domains removed by size thresholding (remaining domains > 78.54 nm2), more clearly unveiling the underlying square/hexagonal lattices. Due to the pixel-based nature of TWS, the collection of pixels in a single domain could comprise more than one class (e.g., red domains with a few green pixels lining the edge, or vice versa). As chain-exchange was shown to be minimal on the experimental timescale (Supplementary Fig. 6), domains (micelles) should only reflect a single BCP chemistry (e.g., only ISV/red or only SVPS/green). To have the segmentation results reflect this, the TWS-output pixel-based segmentation was transformed to an object-based segmentation via a winner-takes-all approach (Supplementary Fig. 7f). Assigning individual red and green pixels values of 0 and 1, respectively, the mean value across an entire domain was taken. Thereafter, domains were recolored such that \(0\le {mean}\le 0.5\,\in {red}\) and \(0.5 < {mean}\,\le 1\,\in {green}\) (Supplementary Fig. 7d). The vast majority (> 70%) of domains fall within 5% of the two extremes (Supplementary Fig. 7e), suggesting a clear pixel-based distinction between the ISV and SVPS classes. As such, the error introduced by this adjustment is minimal. An analogous approach was used for the ISVO165-SVPS53 samples (see Supplementary Fig. 7h–j). For ternary BMAs, a combination of the ISV-ISVO and ISV-SVPS approaches was utilized. Starting with a bandpass filtered image (Supplementary Fig. 7k), the above ISV-SVPS approach yielded Supplementary Fig. 7l. Thereafter, all ISV domains > 471.44 nm2 (24.5 nm diameter, assuming perfect circularity) were reassigned to ISVO (Supplementary Fig. 7m). Visual inspection revealed that domains not part of the primary square ISV/ISVO lattice (spacing > 40 nm) had been erroneously assigned as green (SVPS) (see circled sections of Supplementary Fig. 7m). These features, despite their size and contrast, are not believed to be SVPS due to their existence in binary ISV-ISVO samples (compare square packed regions in Supplementary Fig. 7m with those in Supplementary Fig. 9d). Considering the native lattice spacings of SVPS (~26 nm) and ISV/ISVO (> 40 nm; from Fig. 2i), the SVPS component was isolated from the square-packed components (analogous to Supplementary Fig. 6i), and domains whose NND exceeded 40 nm were removed, yielding Supplementary Fig. 7n.

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)

Starting with a binarized image (e.g., Supplementary Fig. 9e or, for split-component FFT analysis, a binarized version of Supplementary Fig. 6g), the maxima (prominence > 10.00, essentially the domain centroids) were found (Process » Find Maxima…), and the output was used to run the Fiji FFT command. The resulting FFT was subjected to the radial profile plugin (Paul Baggethun), yielding an intensity vs. pixel value plot, where the x-axis was subsequently spatially calibrated to nm−1. Lattice spacing was calculated using \(\frac{2\pi }{q*}\) where q* is the position of the first correlation peak.

Pore size distributions (PSDs)

To obtain PSD statistics, the Analyze Particles… function was run on a binarized image (e.g., Supplementary Fig. 9e). The output area (A) for each pore was transformed into a diameter value (D) assuming perfect circularity (i.e., \(D=2\sqrt{\frac{A}{\pi }}\)).

Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

DLS measurements were performed on a Malvern Zetasizer ZS equipped with a 4 mW 633 nm laser and a 173° backscatter measurement angle setup. 60 mg BCP was dissolved in 7:3 DOX:THF (~2 mL) under overnight stirring (final concentration: 3 wt.% BCP). Solutions were syringe filtered (0.45 μm), after which 1 mL was transferred to a lidded quartz cuvette for characterization. Due to its large micelle size, the ISVO165 solution could not be filtered as such. The viscosity and refractive index for the binary solvent mixture were calculated from pure solvent values at 25 °C, yielding a viscosity of 0.88 cP (classic Arrhenius mixing rule) and a refractive index of 1.42 (volume-fraction mixing rule, Newton formula). Samples were allowed to equilibrate at 25 °C for 120 s prior to measurement. Intensity-based hydrodynamic diameter (DH) distributions (e.g., Supplementary Fig. 10b) were obtained from 10 to 20 runs per measurement as automated by Zetasizer software. Supplementary Fig. 10b shows one representative measurement out of the three taken per sample. Correlation data was exported from the Zetasizer software and plotted without further modification (Supplementary Fig. 10a).

Voronoi analysis

To obtain a detailed understanding of the square and hexagonal motifs in the ISV + SVPS film surface structures, we used the freud library53 to perform a MVA. Adaptations were made from the standard Voronoi tessellation analysis (VTA) to correct for the minor structural perturbations inherent to the square packed ISV121 structures. The input for MVA is the array of domain centroids (FIJI » Process » Find Maxima…) extracted from a binary segmentation of the film surface (TWS-generated output without class information; see Supplementary Fig. 12a). The insets in Supplementary Fig. 12b, c demonstrate how the modified Voronoi cells are derived from the VTA. MVA excludes small Voronoi cell edges resulting from minor lattice perturbations (gray), treating only the remaining cell edges (black) as the central domain’s nearest neighbors. This transformation reveals the fourfold symmetry (red cells in Supplementary Fig. 12c) underlying the predominantly sixfold symmetry (green cells in Supplementary Fig. 12b) suggested by VTA. Small edges can be identified by the angle, δ, subtended by the cell edge to the central domain. After examining the δ distribution of pure ISV121 (lattice: 2D square) and SVPS67 (lattice: 2D hexagonal) top surfaces (Supplementary Fig. 12d), we identified δ = 30° as the cut-off that balances: (1) screening the small edges (δ ≤ 30°) in ISV Voronoi representations while (2) retaining the sixfold symmetry formed by the SVPS domains. Supplementary Fig. 12e compares the ISV121 domains’ number of nearest neighbor distributions according to VTA and MVA (i.e., before and after the imposition of the δ = 30° cut-off).

Cluster analysis

Cluster analysis was utilized to quantify the extent to which SVPS53 disrupts differently sized ISV121 + ISVO165 square lattices (lattice size: domain spacing according to FFT analysis) on ternary ISV121 + SVPS53 + ISVO165 BMA surfaces. A more disrupted lattice is expected to consist of, on average, smaller fourfold symmetry clusters (cluster: a collection of domains exhibiting strong structural correlation). To identify such clusters, the segmentation derived array of domain centroids (Supplementary Fig. 16a) was used in conjunction with its global radial distribution function g(r) (Supplementary Fig. 16b) to identify the four nearest neighbors of each domain (a radial distance of 100 nm was used to search for neighbors, from which the four nearest neighbors were selected). Thereafter, the local fourfold bond orientational order parameter for each domain k, \({\varPhi }_{4}({{{\bf{r}}}}_{k})\) (Eq. (1)), was calculated.

i is the imaginary number and \({\theta }_{{jk}}\) is the angle formed by a fixed reference axis and the \({{{\bf{r}}}}_{k}\) vector connecting domain k to its neighbor j (see inset in Supplementary Fig. 16a). For each of the four nearest neighbors j of domain k, the dot product of the local fourfold bond orientational vectors, d4(j,k) (Eq. (2)), was calculated to estimate their degree of correlation, with a higher value reflecting stronger correlation (distribution of all such pairs in Supplementary Fig. 16c).

The * denotes the complex conjugate. Spatially connected clusters displaying fourfold order were constructed by considering neighbors of k that satisfy d4(j,k) ≥ 0.60, and the number of nearest neighbor connections, Nc ≥ 2. Supplementary Fig. 16d shows the ten largest clusters color-coded based on their number of domains. Our choices of d4(j,k) and Nc were optimized to detect the connectivity of local fourfold ordered clusters and also distinguish the cluster domains separated by grain boundaries.

Simulation methods

Computational coarse graining

The goal of the computational analysis in this work was to provide structural insights into the self-assembly of the ISV-ISVO-SVPS micelle systems submitted to the SNIPS process. While one could approach this by fully modeling the assembly of unimers into micelles and subsequently into lattices, achieving lateral scales comparable to the experimental SEM images (e.g., thousands of micelles) is computationally infeasible. As such, a coarse-grained perspective was adopted to approximate system behavior.

Coarse graining assumed negligible molecular exchange between chemically distinct micelle populations on the SNIPS timescale (< 1 h), as substantiated by Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Discussion 2. Therefore, the BCP micelles should behave as soft, dynamical units whose internal polymer dynamics can be ignored. Given the size of the micelles, a colloidal perspective was utilized where effective pair potentials were used to simulate the interactions between the micellar units, and the solvent was treated implicitly (Supplementary Fig. 3). The dynamics of the system were probed using standard BD methods.

Particle interaction potential

Micelles were treated as colloids whose interaction potential was chosen as follows. The chosen potential must: (1) allow assembly into square (for ISV/ISVO) and hexagonal (for SVPS) geometries; (2) allow for some degree of interpenetration to reflect the soft micellar interactions; (3) be primarily repulsive; (4) be monotonic, as there is no complex interactive pattern in the BCP micelles.

The Yoshida-Kamakura (YK) potential54 (Eq. (3)) is a suitable choice that satisfies the above criteria.

Here, \(\epsilon\) and \(\sigma\) respectively denote the classical scales for energy and length, and \(a\) is the softness parameter whose main role is to control whether the potential leads to square or hexagonal structures. The structural landscape of this potential across different thermodynamic conditions has been studied previously55. In this work, \(a=3.0\) and \(a=3.7\) were respectively used to assemble square (ISV/ISVO) and hexagonal (SVPS) structures at the interface.

Different micelle sizes were accounted for by incorporating a scaling factor \(f\) to the potential (Eq. (4)).

This scaling factor is set based on the relative average pore sizes in the experimental system (Supplementary Fig. 2). Scaling factors for monodisperse simulations are shown in Supplementary Table 3. To represent dispersity, a histogram with a wide bin size (bin size = 2; see Fig. 4i) was used to capture the general shape of the PSD. Each distribution was split into five weighted, discrete populations (μ − 2σ, μ − σ, μ, μ + σ, μ + 2σ) based on its average (μ) and standard deviation (σ). The associated size factors are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

To describe the interaction between chemically distinct micelles, classical geometric mixing rules were used:

For micelle pairs with chemically distinct coronas (e.g., ISVO-SVPS, ISV-SVPS), the additional enthalpic repulsion is accounted for via a mixing value for \(\epsilon\) that exceeds 1. For this work, the optimal value was found to be \({\epsilon }_{{mix}}=1.075\). Supplementary Fig. 4 shows representative examples of the potentials.

Interfacial potential

Solvent evaporation during the SNIPS process drives changes in the interfacial (film-environment) conditions, prompting micelle rearrangement. This interface was approximated by introducing repulsive walls above and below the simulation box that repel all species. These walls follow a half-harmonic form, where only the repulsive part is applied. For each species in the simulation (distinct in either chemistry or size), the interfacial potential follows this functional form:

Here, \(r\) is the distance between the center of mass of the micelle and the wall, \(K\) sets the strength of the repulsion, \(f\) is the scaling factor and \(H\) is the Heaviside function, which serves the role of cutting the interaction at a set length \({r}_{c}\).

The potential for each component is composed of two walls. The first, denoted by \({HW}\), is a hard and short repulsive potential (same for all species) whose exclusive role is to prevent the particles from leaving the simulation box. The second term, denoted by \(i\), is a chemically specific potential that serves to model the conditions at the interface for each species. Species size is accounted for by scaling both the strength and the cutoff of each wall with the species-specific scaling factor \(f\).

The strength of the second wall changes dynamically throughout the simulation to reflect the changes in the interfacial conditions (vide supra; see main text for a more detailed description). At the start, it is the same for all chemical species (normalized by micelle size), but as the simulation goes on, it is increased for species we expect to be repulsed by the interface (ISV and ISVO) and decreased for others (SVPS). This change drives the surface transition and leads to the observed structures. See Supplementary Fig. 5 for a schematic of the wall potential and its evolution.

The values for the interfacial properties were chosen to best match the experimental evolution of the system. For this work, we used \({r}_{c}^{{HW}}=0.5\), \({r}_{c}=2.0\), \({K}^{{HW}}=20\), \({K}_{i}^{{initial}}=0.2\), \({K}_{i}^{{final\; ISV}/{ISVO}}=1.1\) and \({K}_{i}^{{final\; SVPS}}=0.0\).

Mass calculations

As previously stated, experimental PSDs were used to determine the relative simulation sizes (f) of each BCP micelle. To match simulation compositions to those in the experiments, relative micelle masses (m) were computed. For each simulation, unless stated otherwise, the mass of the largest component was set to 1.0. The following relation was then used to derive the masses of the remaining components:

For the densities, the following approximate values were computed based on the densities and volume fractions of each BCP: \({\rho }_{{ISV\_}121}=1.036\frac{g}{{ml}}\), \({\rho }_{{ISVO\_}165}=1.04\frac{g}{{ml}}\) and \({\rho }_{{SVPS\_}53}=1.069\frac{g}{{ml}}\).

Once relative component masses have been calculated, their number ratios can be derived based on the weight fraction of each component in the experimental solution (Supplementary Table 2). For a three component (\(i,j\) and \(k\)) system, the following equation can be used to compute how much of each component, \({N}_{i}\), is needed:

Here \({NT}\) corresponds to the desired total number of particles in the simulated system (300,000 for BD and 1500 for MC simulations), \(m\) corresponds to the mass of each component and \(P\) is the goal mass percentage of each component.

Note that this equation fails if any \(P\) is zero. In that case, it becomes a two-component problem, and the following equation applies:

For polydisperse simulations (vide supra), these equations were used to determine the total number of each chemical species needed, and these were then split using the relative distributions for each size (e.g., Fig. 4i).

Brownian dynamics (BD) simulations

System evolution was studied via BD simulations with implicit solvent, performed on the Large-Scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS)56. For each simulation, the system comprised 300,000 micelles. This led to interfaces with 6000–10,000 particles, comparable to the number of pores in a 2500 × 2500 nm surface SEM image.

All values presented below are in Lennard Jones units as implemented in LAMMPS56. The particles are first initialized randomly at a low concentration in a fully periodic 3D system. The system is then subjected to a Langevin thermostat at a temperature of \(0.025\) and pressurized slowly from \(1.0\) to \(5.0\) using a Berendsen barostat for \(5\times {10}^{5}\) timesteps of 0.05. These conditions were chosen to match the thermodynamic regime in which the YK potential reaches the desired structures.

Once equilibrated, the system is introduced to the interfacial walls in the z direction, while remaining periodic in the x and y directions. To equilibrate the system following the introduction of the walls, it is annealed at a temperature of \(0.05\) and cooled to \(0.02\) for the dynamic interfacial run. This cooling run is for \({1.5\times 10}^{6}\) steps with a timestep of 0.01. After this equilibration run, the timestep is increased to 0.05 and the dynamic interfacial changes start, with walls slowly evolving over \({10}^{6}\) steps. After this procedure is completed, the system undergoes a final equilibration run of \({5\times 10}^{5}\) steps.

During the dynamical wall evolution, particle positions are stored every 5000 steps and the trajectory is read using the pyscal python module57. The top layer composition is used for structural quantification and comparison to experiments. Due to the size dependent scaling of the wall potential (Supplementary Fig. 5a), which drives the system evolution, simulation times between systems representing different ISV BCPs combined with the same SVPS53 BCP are not comparable (i.e., because the different sized ISV components are all scaled to 1.0, the SVPS component ends up ranging from 0.661 to 0.751, even though it is experimentally the same BCP; Supplementary Table 3). To remedy this, the ratios of average pore sizes from the PSD (Supplementary Fig. 2) were used to scale time. The time dependent changes in ISV surface composition before and after scaling are shown in Supplementary Fig. 15a, b, respectively. Scaling for both the monodisperse and polydisperse BD simulations used the ISV121 + SVPS53 system as a baseline. The characteristic time for the ISV121 + SVPS53 BD simulation was chosen to match the ISV121 + SVPS53 experimental surface composition (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 2). Equivalent scaled times were chosen for the remaining systems (Supplementary Fig. 15b), resulting in the surface snapshots shown in Fig. 4f–h, j–l.

Equilibrium Monte Carlo (MC) simulations

In addition to the BD simulations, it was of interest to determine how close the experimentally observed surface structures—derived from a non-equilibrium process—resemble equilibrium structures.

To approximate the equilibrium behavior of the BMAs, classic Metropolis NPT MC simulations58 were performed. The same coarse-grained model and interaction potential (as described above for BD simulations) were used. These simulations were done in 2D, modelling only the equilibrium monolayer morphologies of the corresponding BMAs.

For each simulation, the system starts in a random dilute configuration. The system is then equilibrated for \({1.5\times 10}^{6}\) MC cycles, each corresponding to a mixture of displacement, swap, and area moves. Displacement moves are calibrated to a 40% acceptance rate, while area moves are calibrated to a 30% acceptance rate.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are included in the manuscript or the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Brownian Dynamics and Monte Carlo simulation scripts/codes are freely accessible on GitHub. Additional associated files are available upon request.

References

Chai, J., Wang, D., Fan, X. & Buriak, J. M. Assembly of aligned linear metallic patterns on silicon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 500–506 (2007).

Mai, Y. & Eisenberg, A. Self-assembly of block copolymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 5969–5985 (2012).

Bates, F. S. et al. Multiblock polymers: panacea or pandora’s box? Science 336, 434–440 (2012).

Lutz, J.-F., Lehn, J.-M., Meijer, E. W. & Matyjaszewski, K. From precision polymers to complex materials and systems. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 1–14 (2016).

Liang, R. et al. Hierarchically engineered nanostructures from compositionally anisotropic molecular building blocks. Nat. Mater. 21, 1434–1440 (2022).

Lee, S., Bluemle, M. J. & Bates, F. S. Discovery of a Frank-Kasper σ phase in sphere-forming block copolymer melts. Science 330, 349–353 (2010).

Kim, K. et al. Thermal processing of diblock copolymer melts mimics metallurgy. Science 356, 520–523 (2017).

Lee, H. et al. Thermodynamically stable plumber’s nightmare structures in block copolymers. Science 383, 70–76 (2024).

Winey, K. I., Thomas, E. L. & Fetters, L. J. The ordered bicontinuous double-diamond morphology in diblock copolymer/homopolymer blends. Macromolecules 25, 422–428 (1992).

Matsen, M. W. Phase behavior of block copolymer/homopolymer blends. Macromolecules 28, 5765–5773 (1995).

Spontak, R. J. et al. Phase behavior of ordered diblock copolymer blends: effect of compositional heterogeneity. Macromolecules 29, 4494–4507 (1996).

Lindsay, A. P. et al. A15, σ, and a quasicrystal: access to complex particle packings via bidisperse diblock copolymer blends. ACS Macro Lett. 9, 197–203 (2020).

Ruzette, A.-V. & Leibler, L. Block copolymers in tomorrow’s plastics. Nat. Mater. 4, 19–31 (2005).

Spontak, R. J. & Patel, N. P. Phase behaviour of block copolymer blends. In Developments in Block Copolymer Science and Technology 159–212 https://doi.org/10.1002/0470093943.ch5 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2004).

Gröschel, A. H. et al. Guided hierarchical co-assembly of soft patchy nanoparticles. Nature 503, 247–251 (2013).

Qiu, H., Hudson, Z. M., Winnik, M. A. & Manners, I. Multidimensional hierarchical self-assembly of amphiphilic cylindrical block comicelles. Science 347, 1329–1332 (2015).

Redl, F. X., Cho, K.-S., Murray, C. B. & O’Brien, S. Three-dimensional binary superlattices of magnetic nanocrystals and semiconductor quantum dots. Nature 423, 968–971 (2003).

Leunissen, M. E. et al. Ionic colloidal crystals of oppositely charged particles. Nature 437, 235–240 (2005).

Shevchenko, E. V., Talapin, D. V., Kotov, N. A., O’Brien, S. & Murray, C. B. Structural diversity in binary nanoparticle superlattices. Nature 439, 55–59 (2006).

Evers, W. H., Friedrich, H., Filion, L., Dijkstra, M. & Vanmaekelbergh, D. Observation of a ternary nanocrystal superlattice and its structural characterization by electron tomography. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 9655–9657 (2009).

Walther, A. & Müller, A. H. E. Janus particles. Soft Matter 4, 663–668 (2008).

Li, Z., Kesselman, E., Talmon, Y., Hillmyer, M. A. & Lodge, T. P. Multicompartment micelles from ABC miktoarm stars in water. Science 306, 98–101 (2004).

Liu, S. & Armes, S. P. Synthesis and aqueous solution behavior of a pH-responsive schizophrenic diblock copolymer. Langmuir 19, 4432–4438 (2003).

Magruder, B. R., Park, S. J., Collanton, R. P., Bates, F. S. & Dorfman, K. D. Laves phase field in a diblock copolymer alloy. Macromolecules 55, 2991–2998 (2022).

Case, L. J., Bates, F. S. & Dorfman, K. D. Tuning conformational asymmetry in particle-forming diblock copolymer alloys. Soft Matter 19, 90–97 (2022).

Xie, J., Lai, C. T. & Shi, A.-C. Regulating the self-assembly of AB/CD diblock copolymer blends via secondary interactions. J. Polym. Sci. 62, 716–732 (2024).

Ishizu, K., Omote, A. & Fukutomi, T. Phase separation in binary block copolymer blends. Polymer 31, 2135–2140 (1990).

Abbas, S. & Lodge, T. P. Superlattice formation in a binary mixture of block copolymer micelles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 097803 (2006).

Gdowski, Z. M., Swartzendruber, S. M., Mahanthappa, M. K. & Bates, F. S. Diblock copolymer blends do not mimic metal alloys. Macromolecules https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.4c01146 (2024).

Li, Y. M., Srinivasan, D., Vaidya, P., Gu, Y. & Wiesner, U. Asymmetric membranes from two chemically distinct triblock terpolymers blended during standard membrane fabrication. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 37, 1689–1693 (2016).

Manoharan, V. N. Colloidal matter: packing, geometry, and entropy. Science 349, 1253751 (2015).

George, E. P., Raabe, D. & Ritchie, R. O. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 515–534 (2019).

Oses, C., Toher, C. & Curtarolo, S. High-entropy ceramics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 295–309 (2020).

Schweidler, S. et al. High-entropy materials for energy and electronic applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 266–281 (2024).

Arganda-Carreras, I. et al. Trainable Weka Segmentation: a machine learning tool for microscopy pixel classification. Bioinformatics 33, 2424–2426 (2017).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Zeng, H., Li, J., Liu, J. P., Wang, Z. L. & Sun, S. Exchange-coupled nanocomposite magnets by nanoparticle self-assembly. Nature 420, 395–398 (2002).

Kietzke, T. et al. Novel approaches to polymer blends based on polymer nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 2, 408–412 (2003).

Stein, G. E., Laws, T. S. & Verduzco, R. Tailoring the Attraction of Polymers toward Surfaces. Macromolecules 52, 4787–4802 (2019).

Lin, Z. Evaporative Self-Assembly of Ordered Complex Structures (World Scientific, 2012).

Kawaguchi, D., Ohya, M., Torikai, N., Takano, A. & Matsushita, Y. Temperature dependence of surface segregation in miscible polymer blend of poly(4-trimethylsilylstyrene)/polyisoprene. Polym. J. 39, 1274–1280 (2007).

Koberstein, J. T. Molecular design of functional polymer surfaces. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 42, 2942–2956 (2004).

Dorin, R. M. et al. Solution small-angle X-ray scattering as a screening and predictive tool in the fabrication of asymmetric block copolymer membranes. ACS Macro Lett 1, 614–617 (2012).

Mahynski, N. A., Zerze, H., Hatch, H. W., Shen, V. K. & Mittal, J. Assembly of multi-flavored two-dimensional colloidal crystals. Soft Matter 13, 5397–5408 (2017).

Auer, S. & Frenkel, D. Suppression of crystal nucleation in polydisperse colloids due to increase of the surface free energy. Nature 413, 711–713 (2001).

Karpov, D. et al. High-resolution three-dimensional imaging of topological textures in nanoscale single-diamond networks. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 1499–1506 (2024).

Phillip, W. A. et al. Tuning structure and properties of graded triblock terpolymer-based mesoporous and hybrid films. Nano Lett 11, 2892–2900 (2011).

Zhang, Q. et al. Dynamically responsive multifunctional asymmetric triblock terpolymer membranes with intrinsic binding sites for covalent molecule attachment. Chem. Mater. 28, 3870–3876 (2016).

Peinemann, K.-V., Abetz, V. & Simon, P. F. W. Asymmetric superstructure formed in a block copolymer via phase separation. Nat. Mater. 6, 992–996 (2007).

Gu, Y., Dorin, R. M., Tan, K. W., Smilgies, D.-M. & Wiesner, U. In situ study of evaporation-induced surface structure evolution in asymmetric triblock terpolymer membranes. Macromolecules 49, 4195–4201 (2016).

Hibi, Y., Hesse, S. A., Yu, F., Thedford, R. P. & Wiesner, U. Structural evolution of ternary amphiphilic block copolymer solvent systems for phase inversion membrane formation. Macromolecules 53, 4889–4900 (2020).

Riasi, M. S. et al. Stochastic microstructure delineation and flow simulation in asymmetric block copolymer ultrafiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 668, 121163 (2023).

Ramasubramani, V. et al. freud: a software suite for high throughput analysis of particle simulation data. Comput. Phys. Commun. 254, 107275 (2020).

Yoshida, T. & Kamakura, S. Theory of melting at high pressures. II: pair potentials and melting curves. Prog. Theor. Phys. 47, 1801–1816 (1972).

Yoshida, T. & Kamakura, S. Crystal structures and pair potentials. Prog. Theor. Phys. 56, 330–332 (1976).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Menon, S., Leines, G. D. & Rogal, J. pyscal: a Python module for structural analysis of atomic environments. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1824 (2019).

Frenkel, D. & Smit, B. Understanding Molecular Simulation: From Algorithms to Applications (Elsevier, 2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Y. Gu for providing the ISV164 polymer and R.P. Thedford for experimental assistance in anionic polymerization. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Single Investigator Award DMR-2307013 (U.B.W.). This work made use of the facilities and instrumentation at the Cornell University Materials Research Science and Engineering Center supported by NSF (DMR-1719875) and the Cornell University NMR Facility, which is supported, in part, by the NSF through MRI award (CHE-1531632). This work was also partially supported by the NSF CHE-2101829 Grant. L.A.N.-R. was supported by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program (DGE-1650441 and DGE-2139899) and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation: University Centers for Exemplary Mentoring (UCEM) Fellowship Program (Award No. 81253).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.T. and U.B.W. conceived the ideas for this work. L.T. synthesized and characterized the ISV121 and SVPS67 polymers, performed all SNIPS related experiments, SEM characterization, and associated data analysis; Q.Z. and Y.M.L. synthesized and characterized the ISV138 and ISVO165 polymers; Q.Z. synthesized and characterized the SVPS53, all under the guidance of U.B.W. L.A.N-R. performed BD and MC simulations; B.P.P. performed MVA and cluster analysis, both under the guidance of F.A.E. L.T. and U.B.W. wrote the manuscript, with input from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

L.T. and U.B.W. have submitted a patent disclosure on this work to the Center for Technology Licensing (CTL) at Cornell. U.B.W. is a cofounder of Terapore Technologies, Inc., which has licenced earlier patents on triblock terpolymer derived ultrafiltration membranes from Cornell. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information