Abstract

There is a great unmet medical need for development of molecularly characterizing modalities to assist in the complex classification of rare kidney cancers, some of which are diagnosed as unclassified renal cell carcinoma (unclassified RCC) due to complex histology. Here we show utility of the comparative transcriptome atlas as an assistive modality for complex classification of rare kidney cancers. Whereas whole genome sequencing (WGS) of 52 rare kidney cancers identifies very few clinically significant variants in a subset of cases, unsupervised clustering results of RNA-seq data from 219 renal tumors including 140 rare kidney cancers are largely consistent with the histological classification based on WHO2022 classification. Additionally, the comparative transcriptome atlas may provide an opportunity to define the molecular characteristics of unclassified RCC and might predict patient outcome. These findings support the comparative transcriptome atlas as an assistive modality for complex classification of rare kidney cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lack of an assistive modality for complex classification of rare kidney cancers sometimes leads to over- or under-treatment, or random drug selection without any clear evidence in the management of these rare kidney cancers. Most studies, including The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA) and TRACERx Renal study, have been focused on renal tumorigenesis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC), and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (ChRCC)1,2,3,4. Most clinical trials have been designed for these major histological types, and very few clinical studies have been conducted on rare subtypes, resulting in a great unmet medical need for the development of precision medicine for patients with rare subtypes5,6. Additionally, the genetic panel testing incorporated into routine clinical practice is unable to identify gene variants in a considerable number of these rare kidney cancers.

Histology of rare kidney cancers is complex; complicated immunohistochemistry (IHC) or fluorescence in situ hybridization is necessary for pathological diagnosis7,8. The number of histological subtypes of renal tumors is increasing in the WHO classification of urinary and male genital tumors; 12 subtypes in WHO2004, 16 subtypes in WHO2016, and 21 subtypes in WHO2022 (5th edition)9,10,11. The WHO2022 classification has classified renal tumors into various subtypes, including mucinous tubular and spindle cell carcinoma (MTSCC), clear cell papillary RCC (ccpRCC), tubulocystic RCC (tcRCC), multilocular cystic renal neoplasm (MCRN), TFE3-rearranged RCC (TFE3-RCC), epithelioid angiomyolipoma (eAML), collecting duct carcinoma (CDC), metanephric adenoma, juxtaglomerular cell tumor, Wilms tumor (WT), acquired cystic disease-associated renal cell carcinoma (ACD-RCC), other oncocytic tumors of the kidney, and various hereditary kidney cancers11. Notably, some cases are diagnosed as unclassified renal cell carcinoma (unclassified RCC), for which urologists and medical oncologists have no chance to conduct personalized medicine12,13.

More than thirteen kidney cancer-associated genes have been identified either in metabolic or in epigenetic pathways, most of which were found through kindred analyses of hereditary kidney cancers, including von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome, hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC), and hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndrome (PGL/PCC)14. Functional analyses of kidney cancer-associated genes have provided mechanistic insights into renal tumorigenesis, including increased angiogenesis resulting from the dysregulation of the VHL-HIF-VEGF pathway, upregulated renal cell proliferation and increased mitochondrial biogenesis caused by a dysregulated FLCN/FNIP1/FNIP2 complex, and a distinct CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) driven by mutations in the fumarate hydratase (FH) gene14.

These analyses have, in part, clarified our understanding of renal tumorigenesis resulting from alterations of various kidney cancer-associated genes; however, the molecular complexity in a variety of renal tumors remains elusive. Although BHD-associated renal tumors harbor no common gene variant except FLCN, the causative gene for BHD syndrome, BHD patients develop a variety of histological types of renal tumors, including hybrid oncocytic chromophobe renal tumor (HOCT), ChRCC, oncocytoma, ccRCC, and pRCC, suggesting that the molecular characteristics of renal tumors may not be simply determined by which kidney cancer-associated gene is altered15,16,17. In addition, single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) revealed intra-tumor heterogeneity of BHD-associated HOCT, characterized by mutually exclusive expressions of L1CAM or FOXI1, developmental markers for collecting duct15,18,19. These data suggest that the molecular diversity of renal tumors may be generated not only by variations in altered kidney cancer-associated genes but also by variations in the metabolic and epigenetic status during tumor progression, and hence, a diagnostic modality for precision medicine needs to be developed in addition to the genetic panel testing already incorporated into routine clinical practice.

In this work, to elucidate how molecular heterogeneity develops in various rare kidney cancers, we re-assess the histology of 227 renal tumors according to WHO2022 classification (5th edition), conduct comparative whole genome sequencing (WGS) and RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analyses on some of them, and integrate those data with clinical information including patient outcomes (Table 1, Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Results

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) revealed unique gene alterations in rare subtypes

To investigate renal tumorigenesis of clinically rare subtypes, we conducted WGS analysis of 52 rare subtypes (Fig. 1a–c). Rare subtypes had fewer VHL alterations than ccRCC except for RCC with sarcomatoid features (sRCC), ccpRCC, and MCRN (8/52), and infrequently harbored alterations in PBRM1 (4/52), a gene frequently altered in ccRCC, indicating divergence of rare subtype tumorigenesis from ccRCC (Fig. 1b)1. Alterations of CDKN2A were observed (8/52) in sRCC, TFE3-RCC, CDC, and unclassified RCC, supporting the aggressiveness of these tumors20. WGS analysis identified germline alterations in BAP1 and SDHB in patients at 40 and 25 years of age, respectively, which were not predicted from systemic manifestations or family history, highlighting the difficulty in identifying these rare hereditary kidney cancer kindreds in the clinical setting. Fewer copy number alterations (CNA) were observed in TFE3-RCC, ccpRCC, and eAML, compared to other histological types (Fig. 1c). Loss of chromosomes where various kidney cancer-associated genes are located was observed, including chromosome 1q in FH-deficient RCC and chromosome 3p in VHL and/or BAP1-altered sRCC or unclassified RCC. Loss of chromosome 9p and 9q was observed in sRCC. Interestingly, loss of chromosome 14q, 18p, and 18q was frequently observed in unclassified RCC, suggesting that loss of these chromosomes may contribute to the development of histologically complex kidney cancers (Fig. 1c).

a Images show representative H&E staining of histologically rare RCC and unclassified RCC analyzed in this study. Scale bars represent 100 μm. In each subtype, multiple cases exhibited similar histomorphology, and representative images are shown for each subtype. The number of cases in each subtype is displayed in Table 1. b Gene mutation matrix of WGS data is shown. Variants in kidney cancer-associated genes, chromatin remodeling genes, DNA repair-associated genes, p53 pathway-associated genes, SMAD pathway-associated genes, and Hippo-Yap pathway-associated genes are displayed. c Copy number alterations (CNA) of WGS data are shown. Amp amplification, LOH loss of heterozygosity, Rel. Loss relative loss, Abs. Loss absolute loss. Source data are provided in the Source data file.

Tumor mutation burdens (TMBs), mitochondrial DNA copy numbers, and cell-of-origin (COO) inferred from putative chromatin marks are variable in rare subtypes

WGS analysis exhibited diverse tumor mutation burdens (TMBs) in rare subtypes; TMB of sRCC was high, whereas those of TFE3-RCC, ccpRCC, eAML, and BHD-RCC were low (Fig. 2a). Mitochondrial DNA copy number varied depending on each tumor, especially in tcRCC; mitochondrial DNA copy numbers of TFE3-RCC and BHD-RCC were high, whereas those of MTSCC and ccpRCC were low. (Fig. 2b).

a Box plot shows the number of mutations in various renal tumors. The number of patients in each subtype was as follows: BHD-associated RCC (n = 16), Unclassified RCC (n = 10), ACD-associated RCC (n = 9), TFE3-rearranged RCC (n = 8), Clear cell papillary RCC (n = 7), FH-deficient RCC (n = 5), MTSCC (n = 4), Tubulocystic RCC (n = 4), Epitheliod AML (n = 3), and Clear cell RCC with sarcomatoid (n = 3). Box plots include center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers are the highest and lowest values no greater than 1.5 × IQR. b Box plots show mitochondrial DNA copy numbers in various renal tumors. Patient numbers for each subtype and the style of the box plots are identical to those in Fig. 2a. c The scheme shows four COO types defined in this study. PT (proximal tubule) type includes tumors arising from PEC (parietal epithelial cell), PT_VCAM (subpopulation of proximal tubule with VCAM1 expression), PCT (proximal convoluted tubule), or PST (proximal straight tubule). DT (distal tubule) type includes tumors arising from TAL (thick ascending limb), DCT (distal convoluted tubule), or CNT (connecting tubule). CD (collecting duct) type includes tumors arising from ICA (type A intercalated cells), ICB (type B intercalated cells), or PC (principal cells). MC (mesenchymal) type includes tumors arising from MES_FIB (mesangial cells_fibroblasts) or ENDO (endothelial cells). This figure was created with BioRender.com (https://BioRender.com/0x3wjn7). d Bar plots show COO results for histologically rare renal tumors. Source data are provided in the Source data file.

Comprehensive integrative molecular analyses using multi-omics data from the TCGA project emphasized the dominant role of cell-of-origin (COO) patterns21. On the other hand, a recently reported bioinformatic algorithm that infers COO based on putative chromatin marks shaped by the distribution of somatic mutations, named the COO algorithm, further provides an opportunity to classify renal tumors in the context of their natural history22,23. We first classified ccRCC, pRCC, and ChRCC from the TCGA dataset into four COO types using the COO algorithm, some of which were associated with patients’ prognosis (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2a–e). Next, we applied the COO algorithm to WGS data of the histologically rare subtypes. Generally, the COO in the rare subtypes varied depending on the sample, which may be associated with the molecular diversity of rare subtypes (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2f).

Comparative transcriptome atlas of a variety of renal tumors delineates molecular characteristics of histologically rare RCC and may define features of unclassified RCC

To better understand the complexity of renal tumorigenesis, we analyzed expression profiles of 219 renal tumors that included rare subtypes (140/219) and major histological types without any clinical background, including sporadic clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe renal cell carcinomas (79/219). The dendrogram produced by an unsupervised clustering algorithm based on expression profiles largely matched the histological diagnosis by our pathologists (Fig. 3a). Results from other various unsupervised clustering algorithms, including Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), and principal component analysis (PCA), further supported associations between expression profiles and histological diagnosis (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). In addition, both t-SNE and UMAP analyses using randomly subsampled 150 cases demonstrated robust clustering results that were consistent with those observed in the full set of 219 cases (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). When one of 69 excluded samples was added to a t-SNE plot composed of 150 subsampled cases, it was correctly clustered into the cluster corresponding to its histological subtype (Supplementary Fig. 4c). These algorithms basically subdivided all tumors into four major groups: clear cell, papillary, chromophobe/oncocytic, and “other.” Clusters of MTSCC and pRCC overlapped with each other on the heatmap, suggesting that these tumors may share common molecular characteristics. Four cases of tcRCC did not form a specific cluster and rather scattered across the heatmap, UMAP plot, t-SNE plot, and PCA plot, implying the molecular characteristics of tcRCC may be diverse. MCRN were clustered into clear cell type, indicating that the clear cell feature may be a key element defining the molecular characteristics of these tumors24.

a The upper heatmap created from an unsupervised clustering based on expression profiles shows a variety of molecular characteristics of histologically rare RCC and unclassified RCC. The lower heatmap created from single-sample GSEA (ssGSEA) displays the top 10 upregulated ssGSEA pathways in each cluster. Sarcomatoid: renal tumors with sarcomatoid variant. Systemic ther. systemic therapy, BOR best overall response. Inherited: hereditary kidney cancer. Subtype: Expression subtypes based on expressions of FOXI1 or L1CAM24. Chen’s class.: Subtypes based on Chen’s classification25. Immune subtype: Classification based on a condensed Thorsson immune subtype classification26,27,28,29. IO immuno-oncology drug, TKI tyrosine kinase inhibitor, MTSCC mucinous tubular spindle cell carcinoma, PGL/PCC hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndrome, HOCT hybrid oncocytic chromophobe tumor, Other oncocytic other oncocytic tumors of the kidney, ChRCC chromophobe RCC, ACD-RCC acquired cystic disease-associated RCC, HLRCC FH-deficient RCC, CDC collecting duct carcinoma, MTSCC mucinous tubular and spindle cell carcinoma, TFE3-RCC TFE3-rearranged RCC, tcRCC tubulocystic RCC, pRCC papillary RCC, ccRCC clear cell RCC, Onco oncocytoma, MCRN multilocular cystic renal neoplasm, Other other rare subtypes, uRCC unclassified RCC. b t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) plot is shown. Black dots indicate unclassified RCC cases. Expressions of CA9, FOXI1, AKR1B10, and VEGFA are shown in the lower panels. c t-SNE plot highlighted with the Jaccard index is shown. Source data are provided in the Source data file.

Based on bootstrapping analysis, a widely used validation approach to assess the robustness of clusters, histological subtypes comprising a large number of samples, including ccRCC (n = 57, median Jaccard index = 0.824), pRCC (n = 37, median Jaccard index = 0.780), and ChRCC (n = 26, median Jaccard index = 0.770) demonstrated high Jaccard indices (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 4d and Supplementary Data 2). In contrast, clusters with a smaller number of samples showed more variable Jaccard indices. Exceptionally, MCRN (n = 2, median Jaccard index = 0.858) and MTSCC (n = 5, median Jaccard index = 0.784) showed relatively high Jaccard indices, possibly reflecting shared molecular characteristics with ccRCC and pRCC, respectively. Another notable exception was oncocytoma (n = 5, median Jaccard index = 0.768), which showed a high Jaccard index, indicating the uniformity of expression profiles as well as molecular proximity to ChRCC and BHD-RCC (n = 16).

Urologists and medical oncologists are unable to conduct precision medicine for histologically unclassified RCC, unless gene panel testing can identify genetic alterations (which may occur at low frequency), enabling therapeutic administration of molecular agents that target those genetic alterations. In fact, unclassified RCCs were scattered across the heatmap, UMAP plot, t-SNE plot, and PCA plot, underscoring the molecular diversity of unclassified RCCs (Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Notably, histology reports for some of the unclassified RCC had suggested molecular characteristics that were shared with neighboring cases on the heatmap; one of the differential diagnoses for unclassified RCC RKC7073 (U13) was adult WT, and this unclassified RCC was clustered next to a child WT on the heatmap (Fig. 3a, b and Table 2). Additionally, one of the differential diagnoses for unclassified RCC RKC7687 (U17) was dedifferentiated urothelial carcinoma, and this unclassified RCC was clustered next to a CDC or close to an invasive urothelial carcinoma on the heatmap. These data suggest that a proximity to cases with known histology on the heatmap and t-SNE plot could help us to understand molecular characteristics of unclassified RCC (Fig. 3a, b and Table 2).

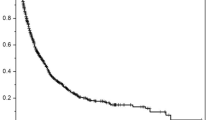

Poor prognostic cases were clustered in a specific location in comparative transcriptome atlas, named Cluster X

Based on the dendrogram of the heatmap, many sRCC or unclassified RCCs were clustered in a specific location named Cluster X, where many poor prognostic cases were clustered (Fig. 3a). Most cases of Cluster X were also plotted in a specific location in the t-SNE plot, and exhibited the poorest prognosis among the five identified clusters (Fig. 4a, b). Two out of three cases of unclassified RCC with NF2 loss, the poor prognostic subtype among the six unclassified RCC subtypes identified by Chen et al., were clustered into Cluster X, supporting its aggressive nature (Fig. 3a)25. Importantly, PCA comparing six cases each of Cluster X with sarcomatoid features and Clear cell type with sarcomatoid features subdivided these two groups into distinct clusters. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using Hallmark pathway demonstrated that pathways associated with tumor progression were enriched in Cluster X with sarcomatoid features compared to Clear cell type with sarcomatoid features, suggesting that sarcomatoid features may not be the key elements characterizing the aggressive nature of Cluster X (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b).

a t-SNE plot colored by five clusters is shown. t-SNE plot in Fig. 3b was used. b Kaplan–Meier curves show the overall survival of patients in five clusters. Log-rank test was used for overall comparisons among clusters. The number of patients in each subgroup was as follows: Chromophobe/Oncocytic type (n = 49), Clear cell type (n = 40), Papillary type (n = 50), Other type (n = 34), and Cluster X (n = 22). c Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) results using Hallmark gene sets comparing Cluster X with Clear cell type (left panel), or Cluster X with Papillary type (right panel) are shown. Red triangles indicate pathways associated with tumor progression, yellow triangles indicate immune-related pathways, and blue triangles indicate pathways typically upregulated in Clear cell or Papillary types. d Differentially expressed genes between Cluster X and Clear cell type (left panel), or Cluster X and Papillary type (right panel) are shown. Genes highlighted in black and blue are associated with neural development and the development of other organs, respectively. Statistical differences were assessed using a two-sided Wald test, and p values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. The number of patients in each subgroup was as follows: Cluster X (n = 24), Clear cell type (n = 53), and Papillary type (n = 56). e A box plot shows signature scores based on the top 20 genes commonly upregulated in Cluster X compared to Clear cell and Papillary types. Gene list is provided in Supplementary Fig. 7a. Statistical differences between groups were assessed using two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (Cluster X versus each other cluster), and p values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. The number of patients in each subgroup was as follows: Chromophobe/Oncocytic type (n = 51), Other type (n = 35), Papillary type (n = 56), Cluster X (n = 24), and Clear cell type (n = 53). Box plots include center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers are the highest and lowest values no greater than 1.5 × IQR. f Kaplan–Meier curves show the overall survival of patients in the TCGA cohort grouped according to the median signature score. Log-rank test was used. The number of patients was as follows: 518 for KIRC (n = 262 with a high Cluster X score and n = 256 with a low Cluster X score); 278 for KIRP (n = 139 with a high Cluster X score and n = 139 with a low Cluster X score); and 65 for KICH (n = 32 with a high Cluster X score and n = 33 with a low Cluster X score). Source data are provided in the Source data file.

Single-sample GSEA (ssGSEA) using C2 (curated gene sets) collection from MSigDB and GSEA using Hallmark pathway exhibited that pathways related to immune response and tumor progression were upregulated in Cluster X. On the other hand, angiogenesis and NRF-2-associated xenobiotic metabolism were downregulated in Cluster X compared to Clear cell and Papillary types, respectively, suggesting that some of the molecular characteristics observed in Clear cell or Papillary types may be lost in Cluster X (Figs. 3a and 4c). Of note, 9 out of 24 Cluster X cases (38%) and 4 out of 53 Clear cell type cases (8%) were classified as immune suppressive types in a condensed Thorsson’s classification (p = 0.00235), suggesting that immune cells might be suppressed in Cluster X cases (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 6a)26,27,28,29. Deconvolution analyses using publicly available scRNA-seq datasets of ccRCC exhibited variable compositions of individual immune cell types, further delineating the distinct immune microenvironment of Cluster X cases (Supplementary Fig. 6b)30,31.

Differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis comparing Cluster X with neighbor clusters, including Clear cell and Papillary types, exhibited that 7 out of 20 top upregulated genes in Cluster X were associated with organ development and cell differentiation, including SOX1, OLIG3, KREMEN2, NKX2-2, AICDA, PAD13, and BARX1 (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). Interestingly, among those genes, SOX1, OLIG3, KREMEN2, and NKX2-2 are key regulators for neural development, suggesting that dysregulated neural lineage program may be associated with the aggressive nature of Cluster X (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). Additionally, a gene signature composed of the top 20 upregulated genes in Cluster X was associated with overall survival in clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe RCC patients in the TCGA cohort (Fig. 4e, f and Supplementary Fig.7a).

Discussion

In this study, 219 renal tumors were grouped into individual clusters by unsupervised clustering, most of which were consistent with the histological diagnosis by our pathologists. Some histological subtypes did not cluster into a specific group; MTSCC and pRCC cases were intermingled in, and tcRCCs were scattered across the heatmap, UMAP plot, t-SNE plot, and PCA plot, suggesting that molecular characteristics of MTSCC and tcRCC might be variable. The bootstrapping analysis further supported the utility of hierarchical clustering based on expression profiles (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 4d and Supplementary Data 2). The median Jaccard index for cluster X was 0.650, indicating a moderately robust clustering in which the primary structure and separation were largely maintained despite some variability. Notably, TMBs were low in TFE3-RCC, eAML, and BHD-RCC relative to the other subtypes. In mouse kidneys, overexpression of the Tfe3 fusion gene, inactivation of Tsc2, or inactivation of Flcn leads to increased kidney cell proliferation, supporting the idea that alterations of TFE3, TSC2, or FLCN may act as main drivers requiring fewer additional alterations for renal tumorigenesis17,32,33,34.

In this cohort, unclassified RCC were scattered across the heatmap, UMAP plot, t-SNE plot, and PCA plot, highlighting their diverse molecular characteristics. Importantly, we did not observe any genetic alteration that indicates a histologic subtype, except for two cases with VHL alterations leading to their clear cell features; therefore, genetic panel testing used in the clinical setting may not be useful to define the molecular characteristics of unclassified RCC. Because the heatmap, UMAP plot, t-SNE plot, and PCA plot created in this study successfully clustered unclassified RCC based on their expression profiles, the comparative transcriptome atlas created from expression profiles of various renal tumor,s including rare subtypes, may serve as a robust tool to define molecular characteristics of unclassified RCC.

The mitochondrion is a critical organ for metabolic homeostasis in nephron cells, and numerous studies have highlighted associations between dysregulated mitochondrial metabolism and renal tumorigenesis. For instance, inactivation of Flcn in murine kidney, muscle, heart, and adipose tissue leads to increased Pgc1a-dependent oxidative phosphorylation35,36,37. In addition, TFE3 and TFEB, both of which are regulated by FLCN, have been reported to be critical regulators of mitochondrial metabolism38,39. Because both BHD-RCC and TFE3-RCC harbored higher mtDNA copy numbers compared to other histological subtypes, the FLCN-TFE3 axis may be a critical regulator of oxidative phosphorylation in some types of renal tumors.

The COO algorithm is a newly created bioinformatics technology that infers the putative COO by integrating genome-wide somatic mutation distributions with epigenomic profiles of nephron cell subpopulations22,23. Importantly, the results of the COO algorithm analysis were in agreement with the molecular characteristics of BHD-RCC in our previous study, in which none of L1CAM-expressing tumors in BHD-associated kidney cancers and sporadic ChRCCs might arise from intercalated cells, as well as with patient prognosis in TCGA ccRCC15 (Supplementary Fig. 2a–e). These results underscore the COO algorithm as a classifier of renal tumors based on the distribution of somatic mutations in the tumor genome, which may be associated with chromatin marks and epigenetic features of their COO.

Mutational signatures are imprints of DNA damage and repair processes that have been operative during tumorigenesis and can provide insights into environmental and endogenous causes of cancer and the biological implications of somatic mutations40. Mutational signature analysis using WGS data demonstrated that rare subtypes harbored mutational signatures of single base substitution (SBS), double base substitution or small insertion and deletion (ID) similar to those observed in the TCGA ccRCC cohort including SBS1 (deamination of 5-methylcytocine), SBS5 (unknown), and SBS40 (unknown); however, some of the signatures including SBS2 (APOBEC activity), SBS13 (APOBEC activity), SBS12 (unknown) and ID12 (unknown) were specific to rare subtypes (Supplementary Fig. 8a–c). Recent studies have uncovered geographic variation in mutational signatures in kidney cancer genomes, including SBS12, which was specific to Japanese ccRCC and hepatocellular carcinoma41,42. Interestingly, strong enrichment of SBS12 (unknown) was observed in ACD-RCC, suggesting that chemicals or waste materials responsible for SBS12 may be incompletely filtered in Japanese hemodialysis patients.

Hereditary kidney cancer may account for 5–8% of kidney cancers diagnosed43. In this study, patients with germline alterations of BAP1 or SDHB had neither systemic manifestations nor family history. Our previous study that aimed to elucidate germline alterations in 1532 Japanese kidney cancer patients demonstrated that 14 out of 249 non-ccRCC patients (5.62%) had germline alterations in kidney cancer-associated genes including BAP1 and FH, and most of those patients were diagnosed under 45 years of age, supporting the previous notion that a portion of histologically rare renal tumors diagnosed under 45 years of age may be hereditary kidney cancer44,45.

DEG analysis exhibited upregulation of genes associated with neural development in Cluster X, including SOX1, OLIG3, KREMEN, and NKX2-2. Notably, SOX2, a highly homologous gene with SOX1, has been implicated in promoting neural lineage characteristics in a subset of hormone-refractory prostate cancers46. Although SOX1 and SOX2 play distinct roles for neural development, it is interesting to postulate that dysregulation of the neural lineage program may be associated with aggressiveness in both prostate and kidney cancers.

The findings in this study, which delineate the molecular landscape of a variety of rare histological subtypes, have in part uncovered the molecular complexity of renal tumorigenesis. Importantly, an unsupervised comparative transcriptome atlas of various kidney cancers, including rare subtypes, exhibited potential as an assistive modality for complex classification, which may define molecular characteristics of histologically undefined cases and predict patient outcomes. These findings suggest that an unsupervised comparative transcriptome may assist complex classification and add some benefit in drug selection for metastatic cases, as well as in post-operative follow-up for early-stage renal tumors.

Methods

Patients and specimens

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yokohama City University (A200100004) and RIKEN (H20-11), and each patient provided written informed consent for publication. Participant characteristics: male, n = 142; female, n = 85; median age 61 years (range 6–87). Sex was abstracted from clinical records (assigned at birth). Participants did not receive financial compensation. Surgical or biopsy specimens of renal tumors (n = 227) were obtained from patients treated at Yokohama City University Hospital, Iwate Medical University Hospital, or Akita University Hospital from 1980 to 2023. Samples were frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored in −80 °C freezers and remain stored for future research. Histology of each tumor was evaluated according to the WHO2022 classification of urinary and male genital tumors (5th edition) by six pathologists who have expertise in kidney cancer11. Each case was evaluated by at least three independent pathologists. The clinical summary for 227 renal tumors is shown in Table 1, and patient outcomes are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. All clinical and sample annotations are available in Supplementary Data 1. Human tissue samples remain stored at Yokohama City University after analysis. Due to ethical and legal restrictions, these samples cannot be openly shared, but they are available to qualified researchers upon approval by the Institutional Review Board of Yokohama City University. Requests for access should be directed to the corresponding author. Sex/gender considerations: Sex was considered as a descriptive variable; no sex-stratified analyses were performed because the study was not powered for subgroup analyses, and this was not a pre-specified objective. Sex-disaggregated counts are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

RNA-seq analysis

In this study, RNA-seq analyses were newly performed on 158 renal tumors that consisted of 90 rare subtypes and 68 major histological types without any clinical background, including sporadic clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe renal cell carcinomas, along with four normal kidneys. These data were integrated with RNA-seq data from our previous studies of 61 renal tumors that were comprised of 50 rare subtypes and 11 major histological types without any clinical background, including sporadic clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe renal cell carcinomas, along with five normal kidneys15,18,47. All 219 renal tumors that were comprised of 140 rare subtypes and 79 major histological types without any clinical background including sporadic clear cell, papillary and chromophobe renal cell carcinomas, along with nine normal kidney tissues were used for comparative transcriptomic analyses in Figs. 3a, b and 4a–d The list of samples analyzed by RNA-seq is available within the “RNA-seq ID” tab in Supplementary Data 1. Additionally, eight renal tumors that developed in hemodialysis patients, shown in Fig. 2a–d, were only analyzed with WGS due to the unavailability of frozen specimens for RNA-seq analysis.

RNAs were extracted from frozen tissues using the RNA extraction reagent ISOGEN (Nippon-gene) following the manufacturer’s protocol, qualified and quantified by Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Library preparation was done using TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit and TruSeq RNA CD Index Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina). Sequencing was performed with the HiSeq 2500 system with 126-bp reads (Illumina). Using STAR (v2.7.9a), the FASTQ files were mapped to a reference sequence generated from the GRCh38 fasta and GENCODE Release 38 comprehensive gene annotation for reference chromosomes. Aligned SAM files were sorted, and duplicates were marked with Picard MarkDuplicates. Mapped reads were counted by featureCounts. For the series of analyses from FASTQ file data to raw count data, the riboduct pipeline was used (https://github.com/msfuji/riboduct), and the details of the commands and parameter settings are available on the GitHub page. Then, these read count data were used for further expression analysis. All RNA-seq data were generated at a single institution using the same reagents and protocols. No significant batch effect associated with sequencing time points was observed in various unsupervised clustering analyses, including heatmap, t-SNE, UMAP, and PCA. Fusion genes were detected using STAR-Fusion (v1.12.0) with default parameters and the GRCh38_gencode_v44_CTAT reference, based on FASTQ files. Output files are provided in Supplementary Data 3. With STAR-Fusion, we have detected TFE3 fusion genes in seven cases. However, based on our WGS data, which identified TFE3 fusion genes in eight cases, we concluded that this cohort includes eight cases of TFE3-rearranged RCC (Fig. 1b).

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) analysis

In this study, WGS analysis was newly performed on 65 renal tumors consisting of 52 rare subtypes and 13 major histological types without any clinical background, including sporadic clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe renal cell carcinomas. WGS data from the 52 rare subtypes were further analyzed and used in Fig. 1b, c. The WGS data from the 52 rare subtypes in this study were integrated with our previous data of 48 rare subtypes, including 18 BHD-RCC and 30 RCC that developed in hemodialysis patients, and the results from these integrated data are shown in Fig. 2a–d after removing data from singlets15,18,47. The list of samples analyzed by WGS is available within the “WGS ID” tab in Supplementary Data 1.

Genomic DNA was extracted from frozen tissues using the QIAGEN DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer’s protocol, qualified and quantified by Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Either an adjacent normal kidney or a blood sample was used as a reference. The library construction was done using the TruSeq Nano DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Paired-end sequencing of 150-bp reads was performed using NovaSeq6000. FastQC ver 0.11.9 was used to examine the quality of the WGS reads. Reads were then mapped, sorted, and duplicates marked using fq2bam in Parabrick 4.0.0-1 with readgroups set based on sample, flowcell, and lane number. The reference GRCh38 genome fasta (GCA_000001405.15_GRCh38_no_alt_analysis_set.fna) was obtained from the Hartwig Medical Foundation’s resource website. Fq2bam was run with –knownSites file Homo_sapiens_assembly38.dbsnp138.vcf.gz and Homo_sapiens_assembly38.known_indels.vcf.gz downloaded from https://console.cloud.google.com/storage/browser/gcp-public-data--broad-references/hg38/v0;tab=objects?pli=1&invt=AbuR7w&prefix=&forceOnObjectsSortingFiltering=false. Parabricks CollectWGSMetrics was used to calculate WGS metrics used in subsequent steps.

Germline and somatic variant calling

Single-nucleotide variants (SNV), multi-nucleotide variants (MNV), and small insertion-deletions (Indels) were called using SAGE v3.2 (Somatic Alterations in Genome) from the Hartwig Medical Foundation (HMF: https://github.com/hartwigmedical/hmftools/releases/tag/sage-v2.8). Germline calling parameters were based on the “germline mode” in the SAGE documentation. The panel-of-normals (PON) VCFs used in the pipeline for annotation and filtering of somatic variants called by SAGE were created from 149 Japanese germline samples 1. Genome-wide somatic variant calls were performed with a quality cutoff of 70 and then filtered using bcftools with a quality cutoff of 70 for hotspots and 100 for other genomic locations. The maximum acceptable variant allele frequency (VAF) for the reference sample was set at 4% and the minimum VAF for the tumor was set at 2.5%. The output VCFs were filtered for PON variant sites, sites that were variant or likely fixed (MAF > 0.01 and AF < 0.99; AF ≥ 0.99) in dbSNP or ALFA population samples47. The resulting VCFs were annotated using HMF’s PAVE v1.4.2 (https://github.com/hartwigmedical/hmftools/releases/tag/pave-v1.4.2). To integrate analyses of SNVs/MNVs/Indels, SVs, and CNAs, we processed germline and somatic VCFs with output of GRIDSS v2.13.2 (https://github.com/PapenfussLab/gridss/releases/tag/v2.13.2), B-allele frequencies (BAF) from AMBER v3.9 (https://github.com/hartwigmedical/hmftools/releases/tag/amber-v3.9), and read depth ratios from COBALT v1.14 (https://github.com/hartwigmedical/hmftools/releases/tag/cobalt-v1.14) through PURPLE v3.8.3 (https://github.com/hartwigmedical/hmftools/releases/tag/purple-v3.8.3/) and Linx v1.23.5 (https://github.com/hartwigmedical/hmftools/releases/tag/linx-v1.23.5) using our Tumor-GRaPPLer pipeline47. Gene fusions based on WGS data were extracted from Linx output files. Variants detected in this study were listed in Supplementary Data 4.

Copy number alteration (CNA) and tumor mutation burden (TMB) analyses

PURPLE’s CN segment data were processed to detect LOH, absolute deletions, relative deletions, gains, and amplifications. Cytoband regions were annotated using GRCh38. CNA results are available in Supplementary Data 5. The number of mutations were counted based on the VCF files, and those results are available in Supplementary Data 6.

Mitochondrial DNA analysis

Mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) copy number per cell in tumor and normal tissues was calculated as previously described15,48. The results are available in Supplementary Data 7.

Cell-of-origin (COO) estimation based on putative chromatin marks shaped by the distribution of somatic mutations

COOBoostR is an xgboost-based machine learning algorithm that aims to predict putative tissue-of-origin or COO (https://github.com/SWJ9385/COOBoostR)22,23. Recent studies revealed that COO chromatin marks and epigenomic features, including open chromatin regions, are associated with the distribution and density of somatic mutations in the cancer genome22. These findings support the concept that the mutational landscape of a given cancer may reflect its COO. Based on this concept, we inferred the COO of various kidney cancers by applying a machine learning algorithm that integrates genome-wide somatic mutation distributions with a public database of cell type-specific epigenetic profiles for each nephron cell subpopulation23,49. In our study, COOBoostR was applied to predict putative COO in each rare kidney sample and the TCGA kidney cancer data. Briefly, 1-megabase window-based somatic point mutation frequencies from WGS data were calculated for individual tumor samples, along with processing single-cell ATAC-seq data from normal kidney tissue by calculating 1-megabase window sequencing count density for each cell type (pre-specified inside the metadata)49. Samples whose mutation density (number of mutations per 1-megabase) is above 1.25 were used in Fig. 2d to ensure a prediction accuracy of over 80%23. All prediction results, including those for the remaining samples with a mutation density below 1.25, are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2f. For the parameters, default values were used except for the eta and depth (set to 0.3 and 10). Results of COOBoostR analysis are available in Supplementary Data 8. For TCGA samples, we used consensus somatic VCF files from the ICGC/TCGA PCAWG project50. The original VCF files were aligned to the GRCh37 reference genome, so we lifted them over to GRCh38 using GATK v4.5.0.0 LiftoverVcf with a chain file obtained from Ensembl (http://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/assembly_mapping/homo_sapiens/GRCh37_to_GRCh38.chain.gz) and modified to use chr1–22, chrX, chrY, and chrM instead of 1–22, X, Y, and MT. The lifted-over SNV/MNV and indel files were merged sample-wise using the VariantAnnotation package in R (v.1.52.0)51, filtered to retain only “PASS” sites, and exported with TCGA sample IDs.

Mutational signature analysis

Analysis of somatic mutation signatures was performed using SigProfiler (v.3.3)(https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/signatures/tools/) with the VCFs. Somatic mutation signature profiles were decomposed to COSMIC 3.2 signatures40. The default settings were used for each parameter in all of the analyses. The results are available in Supplementary Data 9.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

GSEA was done with GSEA software (v.4.2.3) (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp) using RNA-seq count data normalized by the variance-stabilizing transformation (VST) function in the DESeq2 R package (version 1.46.0) with default parameters52,53. ssGSEA was performed using the GSVA R package (version 2.0.7) with RNA-seq count data normalized by counts per million (CPM). The gene set used for this analysis was “c2.all.v2024.1.Hs.symbols.gmt” from MSigDB version 2024.1. The results are available in Supplementary Data 10–12.

Clustering analysis

For unsupervised clustering analyses, a Heatmap was created based on the top 2000 most variable genes using iDEP (integrated Differential Expression and Pathway analysis) (v.0.96) (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/idep96/), a tool for RNA-seq analysis54. Raw count data were normalized using a VST using the DESeq2 package in iDEP, and default settings were used for each parameter. UMAP and t-SNE were done using the R package Seurat (v.5.1.0) based on the top 2000 most variable genes53,55. For UMAP and t-SNE, raw count data were normalized using log-normalized and scaled using Seurat (v5.1.0). UMAP analysis was conducted using the RunUMAP function with the argument dims = 1:10, and t-SNE analysis was performed using the RunTSNE function with the argument dims = 1:10. For PCA, raw count data were normalized using the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) method with the edgeR package (v3.42.4), followed by log2 transformation with a prior count of 1 to obtain logCPM value56. PCA was conducted based on the 2000 most variable genes. To assess robustness of clustering, unsupervised clustering analyses using 150 randomly subsampled cases were done twenty times each with t-SNE and UMAP analyses, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4a (t-SNE) and 4B (UMAP). One of the 69 excluded samples was added to a t-SNE plot composed of 150 subsampled cases to ensure that the added sample is correctly clustered into the cluster corresponding to its histological subtype, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4c. The list of subsampled cases is shown in Supplementary Data 13.

Bootstrapping analysis

To assess the robustness of hierarchical clustering, we performed a bootstrap-based stability analysis in 30-dimensional principal component (PC) space. PCA was performed on the scale.data matrix of the 2000 highly variable genes identified by the FindVariableFeatures function in Seurat. The top 30 PCs were used for all subsequent analyses. In each of 1000 bootstrap iterations, 219 samples were resampled with replacement, and PCA was recalculated. Each sample’s k-nearest neighbors (k = 30) in the bootstrapped PC30 space were compared to those in the original PC30 space, and a Jaccard index was computed. These values were averaged across iterations to obtain a mean Jaccard stability score per sample. The resulting scores were used to evaluate clustering robustness. The list of Jaccard indices for each sample is provided in Supplementary Data 2.

Differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis

DEG analysis was performed using DESeq2 (v1.40.2) with internal normalization by the median-of-ratios method. The gene list is available in Supplementary Data 1453.

Immune subtype analysis

Immune subtype analysis based on a condensed Thorsson’s classification was conducted using ssGSEA26,27,28,29. Gene sets were defined as follows: high expression of CD8A, CD8B, GZMA, GZMB, PRF1, IFNG, CXCL9, and CXCL10 for the Immune_Hot subtype; high expression of TGFB1, SMAD2, SMAD3, and SMAD4 for the Immune_Excluded subtype; high expression of FOXP3, IL2RA, CTLA4, CD33, ARG1, and S100A9 for the Immune_Suppressive subtype; and low expression of PTPRC, CXCR4, and CCR7 for the Immune_Desert subtype26,27,28,29. The results are provided in Supplementary Data 15.

Deconvolution analysis

To estimate the proportion of immune cell populations in tumor tissues, deconvolution of bulk RNA-seq datasets was performed using CIBERSORTx (https://cibersortx.stanford.edu/) with publicly available scRNA-seq datasets30,31,57. For the single-cell input option, the Min. Expression parameter was set to 0, while other parameters were kept at default values: 999 for the maximum condition number (kappa) for the signature matrix, 0.01 for the q-value cutoff for differential expression analysis, and 300 and 500 for the minimum and maximum number of barcode genes per phenotype, respectively. Using the resulting signature matrix, cell fraction imputation was conducted with the Impute Cell Fractions module in CIBERSORTx. S-mode was selected for batch correction, and the same scRNA-seq dataset used to generate the signature matrix was also provided as the single-cell reference matrix file. The number of permutations for significance analysis was set to 100. The estimated immune cell fractions are provided in Supplementary Data 16.

Statistics

Welch’s two-sample t-test or Wilcoxon test was applied to determine whether the means of two populations were different, and differences were considered to be statistically significant at a value of p < 0.05. For multiple comparisons, p values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. All statistical tests were two-sided. For the analysis of the correlation between the two gene expressions, Pearson’s correlation coefficient and p value were calculated. Survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan–Meier method with the R packages survival (v3.8.3; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival) and survminer (v0.5.0; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survminer). The log-rank test was applied to assess statistical differences between groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions between categorical variables, particularly for contingency tables with small sample sizes.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the Japanese Genotype-phenotype Archive (JGA) under accession numbers JGAS000737. The data are available under restricted access due to ethical and legal restrictions related to human genetic data. Access can be obtained by applying to the National Bioscience Database Center (NBDC) with an approved data use agreement, in accordance with the JGA guidelines. All requests for data and materials will be promptly reviewed to verify whether the request is subject to any intellectual property or confidentiality obligations. The raw sequencing data are protected and not publicly available due to data privacy laws. Inquiries regarding data should be forwarded to the corresponding author, H. Hasumi. Any materials that can be shared will be released via a Material Transfer Agreement. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All codes used to generate Figs. 1–4 and Supplementary Figs. S1–S8 are available at Figshare: https://figshare.com/s/ad48d64a102255d08bd6.

References

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature 499, 43–49 (2013).

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of papillary renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 135–145 (2016).

Davis, C. F. et al. The somatic genomic landscape of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 26, 319–330 (2014).

Turajlic, S. et al. Tracking cancer evolution reveals constrained routes to metastases: TRACERx renal. Cell 173, 581–594 e512 (2018).

Motzer, R. J. et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1277–1290 (2018).

Motzer, R. J. et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus sunitinib in first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: final prespecified overall survival analysis of CLEAR, a phase III study. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 1222–1228 (2024).

Lee, S., Kim, B., Park, J. H. & Moon, K. C. Fumarate hydratase-deficient renal cell carcinoma: a single institution-based study of 29 patients by clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and genetic approaches. Pathology 57, 10–16 (2025).

Kato, I. et al. RBM10-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma characterised by paracentric inversion with consistent closely split signals in break-apart fluorescence in-situ hybridisation: study of 10 cases and a literature review. Histopathology 75, 254–265 (2019).

Lopez-Beltran, A., Scarpelli, M., Montironi, R. & Kirkali, Z. 2004 WHO classification of the renal tumors of the adults. Eur. Urol. 49, 798–805 (2006).

Moch, H., Cubilla, A. L., Humphrey, P. A., Reuter, V. E. & Ulbright, T. M. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs—Part A: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur. Urol. 70, 93–105 (2016).

Moch, H. et al. The 2022 World Health Organization classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs—Part A: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur. Urol. 82, 458–468 (2022).

Perrino, C. M., Grignon, D. J., Williamson, S. R., Idrees, M. T., Eble, J. N. & Cheng, L. Morphological spectrum of renal cell carcinoma, unclassified: an analysis of 136 cases. Histopathology 72, 305–319 (2018).

Sirohi, D., Smith, S. C., Agarwal, N. & Maughan, B. L. Unclassified renal cell carcinoma: diagnostic difficulties and treatment modalities. Res. Rep. Urol. 10, 205–217 (2018).

Linehan, W. M. et al. The metabolic basis of kidney cancer. Cancer Discov. 9, 1006–1021 (2019).

Jikuya, R. et al. Comparative analyses define differences between BHD-associated renal tumour and sporadic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. EBioMedicine 92, 104596 (2023).

Hasumi, H. et al. BHD-associated kidney cancer exhibits unique molecular characteristics and a wide variety of variants in chromatin remodeling genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 2712–2724 (2018).

Henske, E. P., Cheng, L., Hakimi, A. A., Choueiri, T. K. & Braun, D. A. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 41, 1383–1388 (2023).

Jikuya, R. et al. Single-cell transcriptomes underscore genetically distinct tumor characteristics and microenvironment for hereditary kidney cancers. iScience 25, 104463 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Single-cell analyses of renal cell cancers reveal insights into tumor microenvironment, cell of origin, and therapy response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2103240118 (2021).

Ricketts, C. J. et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas comprehensive molecular characterization of renal cell carcinoma. Cell Rep. 23, 313–326.e315 (2018).

Hoadley, K. A. et al. Cell-of-origin patterns dominate the molecular classification of 10,000 tumors from 33 types of cancer. Cell 173, 291–304.e296 (2018).

Polak, P. et al. Cell-of-origin chromatin organization shapes the mutational landscape of cancer. Nature 518, 360–364 (2015).

Yang, S. et al. COOBoostR: an extreme gradient boosting-based tool for robust tissue or cell-of-origin prediction of tumors. Life 13, 71 (2022).

Halat, S. et al. Multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma is a subtype of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 23, 931–936 (2010).

Chen, Y. B. et al. Molecular analysis of aggressive renal cell carcinoma with unclassified histology reveals distinct subsets. Nat. Commun. 7, 13131 (2016).

Thorsson, V. et al. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity 48, 812–830.e814 (2018).

Bruni, D., Angell, H. K. & Galon, J. The immune contexture and Immunoscore in cancer prognosis and therapeutic efficacy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 662–680 (2020).

Spranger, S., Bao, R. & Gajewski, T. F. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature 523, 231–235 (2015).

Mariathasan, S. et al. TGFbeta attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature 554, 544–548 (2018).

Alchahin, A. M. et al. A transcriptional metastatic signature predicts survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 13, 5747 (2022).

Li, R. et al. Mapping single-cell transcriptomes in the intra-tumoral and associated territories of kidney cancer. Cancer Cell 40, 1583–1599.e1510 (2022).

Alesi, N. et al. TFEB drives mTORC1 hyperactivation and kidney disease in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Nat. Commun. 15, 406 (2024).

Baba, M. et al. TFE3 Xp11.2 translocation renal cell carcinoma mouse model reveals novel therapeutic targets and identifies GPNMB as a diagnostic marker for human disease. Mol. Cancer Res. 17, 1613–1626 (2019).

Baba, M. et al. Kidney-targeted Birt-Hogg-Dube gene inactivation in a mouse model: Erk1/2 and Akt-mTOR activation, cell hyperproliferation, and polycystic kidneys. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 100, 140–154 (2008).

Hasumi, H. et al. Regulation of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism by tumor suppressor FLCN. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 104, 1750–1764 (2012).

Hasumi, Y. et al. Folliculin (Flcn) inactivation leads to murine cardiac hypertrophy through mTORC1 deregulation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 5706–5719 (2014).

Yan, M. et al. Chronic AMPK activation via loss of FLCN induces functional beige adipose tissue through PGC-1alpha/ERRalpha. Genes Dev. 30, 1034–1046 (2016).

Napolitano, G. et al. A substrate-specific mTORC1 pathway underlies Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Nature 585, 597–602 (2020).

El-Houjeiri, L. et al. The transcription factors TFEB and TFE3 link the FLCN-AMPK signaling axis to innate immune response and pathogen resistance. Cell Rep. 26, 3613–3628.e6 (2019).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature 578, 94–101 (2020).

Senkin, S. et al. Geographic variation of mutagenic exposures in kidney cancer genomes. Nature 629, 910–918 (2024).

Fukagawa, A. et al. Genomic and epigenomic integrative subtypes of renal cell carcinoma in a Japanese cohort. Nat. Commun. 14, 8383 (2023).

Ball, M. W. & Shuch, B. M. Inherited kidney cancer syndromes. Curr. Opin. Urol. 29, 334–343 (2019).

Sekine, Y. et al. Different risk genes contribute to clear cell and non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma in 1532 Japanese patients and 5996 controls. Hum. Mol. Genet 31, 1962–1969 (2022).

Shuch, B. & Zhang, J. Genetic predisposition to renal cell carcinoma: implications for counseling, testing, screening, and management. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 3560–3566 (2018).

Mu, P. et al. SOX2 promotes lineage plasticity and antiandrogen resistance in TP53- and RB1-deficient prostate cancer. Science 355, 84–88 (2017).

Johnson, T. A. et al. Genomic features of renal cell carcinoma developed during end-stage renal disease and dialysis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 32, 290–303 (2023).

Yuan, Y. et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of mitochondrial genomes in human cancers. Nat. Genet. 52, 342–352 (2020).

Muto, Y. et al. Single cell transcriptional and chromatin accessibility profiling redefine cellular heterogeneity in the adult human kidney. Nat. Commun. 12, 2190 (2021).

Consortium ITP-CAoWG Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature 578, 82–93 (2020).

Obenchain, V., Lawrence, M., Carey, V., Gogarten, S., Shannon, P. & Morgan, M. VariantAnnotation: a Bioconductor package for exploration and annotation of genetic variants. Bioinformatics 30, 2076–2078 (2014).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Ge, S. X., Son, E. W. & Yao, R. iDEP: an integrated web application for differential expression and pathway analysis of RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinform. 19, 534 (2018).

Hao, Y. et al. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 293–304 (2024).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Newman, A. M. et al. Determining cell type abundance and expression from bulk tissues with digital cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 773–782 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Noboru Nakaigawa, Dr. Keiichi Kondo, Dr. Narihiko Hayashi, Dr. Kimito Osaka, Dr. Koichi Uemura, Dr. Takuya Kondo, and Dr. Yumiko Yokomizo in the Department of Urology, Yokohama City University, for the surgical resection of kidney cancers. Authors were supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number as follows: H. Hasumi by 23K08717, I.K. by 19K16563, Y. Ito by 19K18591, H.I. by 20K18121 and 19K23781, M.K. by 21H03068, M. Furuya by 20K07395, M.Y. by 19K09717, S.F. by 19K07769, H.N. by 18H04049, T.Hasegawa by 25K00119, and M.B. by 18H02938. This work was also supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI), Center for Cancer Research. This project was funded in part with federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, NIH, under Contract HHSN261201500001E. This study was also supported in part by the Nippon Shinyaku Research Grant (Grant number: 2472000001 to R.J.), the Takeda Science Foundation (Grant number: 2471000035 to R.J.), and the Yokohama City University Academic Research Promotion Program (“Young Researcher Support Project”) (no grant number, to R.J.). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.J., C.J.R., L.S.S., W.M.L., H. Nakagawa, and H. Hasumi designed the study and wrote the manuscript. G.N., S.M., W.O., K.N., T. Habuchi, T. Tatenuma, D.U., M.K., H.I., Y. Ito, K. Muraoka, K. Makiyama, Y. Iribe, H. Hamanoue, T.M., S.O., S.K., K.A., H. Nagasaka, T. Kawahara, M.Y., and H. Hasumi contributed to sample acquisition. E.M., S.F., M.F., I.K., T. Tsuzuki, and Y.N. contributed to the pathological evaluation. R.J., T.A.J., K. Maejima, S.S., Y.K., H.L., W.J.S., H.S., S.I., Y. Momozawa, A.N., T. Hasegawa, H. Nakagawa, and H.Hasumi analyzed data. R.J., Y. Miura, G.K., T.O., H.U., M.B., T. Tamura, T.S., T. Kodama, B.M.S., C.J.R., L.S.S., W.M.L., H. Nakagawa, and H. Hasumi interpreted the data. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Gabriel Malouf, who co-reviewed with Xiaofan Lu, Yuping Zhang, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jikuya, R., Johnson, T.A., Muraoka, E. et al. Comparative transcriptome atlas as an assistive modality for complex classification of rare kidney cancers. Nat Commun 16, 10340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65303-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65303-z