Abstract

Acute myocardial infarction remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Pharmacogenetic and chronotherapeutic approaches are increasingly applied to optimize therapy in chronic cardiovascular diseases. While gene variants are known to influence long-term drug efficacy, their role in modulating drug-induced cardioprotection in acute conditions such as myocardial infarction is unclear. Similarly, the impact of circadian timing on cardioprotective responses remains insufficiently defined. To address these questions, we evaluated metoprolol as a model cardioprotective agent. Here we examine, in a non–pre-specified exploratory analysis of the METOCARD-CNIC trial (NCT01311700), the influence of ADRB1 Arg389Gly polymorphism and the time of AMI onset on metoprolol efficacy. We found that metoprolol reduced infarct size only in patients homozygous for the ADRB1 Arg389 allele, consistent with its genotype-dependent inhibition of neutrophil migration. In-silico docking and binding studies revealed unstable interactions of metoprolol with the Gly389 variant of ADRB1. Moreover, metoprolol was associated with reduced infarct size when AMI onset occurred between 6:00 and 12:00 h. Restricted cardioprotection to the light phase was confirmed in male mice and in neutrophil-specific Adrb1-knockout models. Collectively, these findings highlight the critical roles of genetic background and circadian timing in shaping the efficacy of acute cardioprotective therapies, supporting the rationale for personalized interventions in acute myocardial infarction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Precision medicine entails the adjustment of disease medication and prevention strategies according to patient-specific factors such as environment, lifestyle, and genotype. One of the key elements of precision medicine is pharmacogenetic testing, which has emerged as a valuable guide to the treatment of cardiovascular (CV) conditions affected by genetic variants in drug-metabolizing enzymes. The most prominent example is CYP2C19 genotyping, which is now widely used to predict the efficacy of clopidogrel1. Other promising applications of pharmacogenetic guidance in CV medicine include warfarin dosing and statin medication2.

Several CV phenotypes are linked to single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the beta-1 adrenergic receptor (ADRB1). The most studied ADRB1 variants are the Arg389Gly (rs1801253) and Ser49Gly (rs1801252) polymorphisms, with the Gly variants in each case associated with lower receptor activity, through decreased signal transduction and receptor downregulation, respectively2,3. These SNPs have been shown to influence cardiovascular disease (CVD) progression and the response to beta-blockers2,4,5,6,7,8. The Arg389 variant in particular is strongly associated with a stronger effect of beta-blockers in chronic diseases, including heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and hypertension2.

CV pathophysiology, including medication kinetics and dynamics, is also influenced by circadian rhythms, resulting in administration-time differences in efficacy and safety. Scheduling medication according to the body’s circadian rhythms, known as chronotherapy, has been shown to improve treatment effects. For example, hypercholesterolemia is more effectively controlled when statins are taken before dinner, and acetylsalicylic acid is more effective at reducing the post-waking peak in platelet aggregation if taken before bedtime9.

Pharmacogenetic and chronotherapeutic strategies are increasingly used in the management of chronic CVDs; however, little attention has been paid to their potential application in acute disease contexts such as myocardial infarction (MI), a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. MI shows time-of-day variations in both onset and the degree of irreversible injury10,11, with the onset of the light phase associated with a higher frequency of events and larger infarcts. There is also evidence for time-of-day changes in the rate of infiltration into the infarcted myocardium by leukocytes, especially neutrophils12,13.

The preservation of myocardial function after MI depends on the rapid reestablishment of myocardial blood flow to minimize infarct size (IS). However, reperfusion triggers a neutrophil-driven sterile inflammatory process that contributes to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI) and final IS14,15,16,17,18. Another important contributor to IRI is microvascular obstruction (MVO), which can prevent efficient tissue perfusion despite blood flow restoration in the large epicardial coronary artery19,20. IS can be limited by timely administration of the selective ADRB1 blocker metoprolol21,22,23, largely through its inhibitory action on neutrophils24. Based on evidence from patients and animal models, current clinical practice guidelines recommend early intravenous (i.v.) administration of metoprolol to patients with an ongoing MI25.

In the present study, we explored the efficacy of the protective effect of i.v. metoprolol against myocardial IRI according to the time-of-day MI onset and patient genotype. Our results show that metoprolol cardioprotection is restricted to patients with the Arg/Arg389 ADRB1 genotype and is effective only when MI onset occurs in the morning. These outcomes highlight the importance of considering genotype and time-of-day when evaluating drug efficacy in acute clinical settings and support the development of individualized therapeutic approaches to acute CVD.

Results

The cardioprotective effect of metoprolol in patients with acute myocardial infarction is dependent on ADRB1 genotype

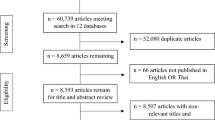

Blood samples taken from the last 102 consecutive patients enrolled in the METOCARD-CNIC trial in Madrid were used to genotype the Arg389Gly SNP (rs1801253) in the ADRB12. As per the trial protocol, patients had been randomized to receive i.v. metoprolol (n = 51) or control (no metoprolol, n = 51) during hospital transit during MI (Fig. 1a). In agreement with previous studies26,27,28, the Arg389Gly genotype distribution was 56% Arg/Arg389, 37% Arg/Gly389, and 8% Gly/Gly389 (Fig. 1b). The analysis was performed assuming a dominant model and comparing Arg/Arg to Gly carriers.

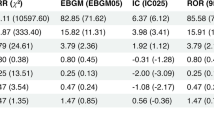

A METOCARD-CNIC trial timeline: patients with ongoing ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) were recruited and randomized to receive i.v. metoprolol (up to 15 mg) or control (no drug) before reperfusion. A subset of 102 patients (51 control, 51 metoprolol) was genotyped for the Arg389Gly beta-1 adrenergic receptor (ADRB1) single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (rs1801253), and the patients were assessed for infarct size (IS) by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging 1 week after acute myocardial infarction as per the standard METOCARD protocol. B Genotype distributions of the Arg389Gly SNP in the full ADRB1-genotyped subcohort and in patients with pre-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) TIMI grade 0–1 (88 patients: 46 control, 42 metoprolol), when assuming a dominant model and comparing Arg/Arg to Gly carriers. C–E CMR analysis of cardiac anatomy and function at 1-week post-reperfusion stratified by ADRB1 Arg389Gly genotype in all patients (left) and in patients with pre-PCI TIMI grade 0–1 (right). Linear regression models were used to evaluate the association between patient genotype and IS (necrotic tissue, g) (C); microvascular obstruction (MVO, % of left ventricle) (D); and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, %) (E), after adjusting for the following cofounders: sex, age, diabetes mellitus, ischemia duration, and pre-PCI TIMI. Patient numbers (C | M) = 30 | 27 Arg/Arg389 and 21 | 24 Arg/Gly389 + Gly389 for the full subcohort and 26 | 23 Arg/Arg389 and 20 | 19 Arg/Gly389 + Gly389 for patients with pre-PCI TIMI grade 0 to 1. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Differences were deemed statistically significant at P < 0.05. C control group, M metoprolol group. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

IS measured by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) on day 7 post-infarction was significantly limited by iv metoprolol among patients with the Arg/Arg389 genotype (median [Q1, Q3] IS: 16.94 g [6.080, 36.30 g] vs. 29.16 g [13.38, 45.04 g] in Arg/Arg389 control patients; P < 0.05). For Arg/Gly389 and Gly/Gly389 genotypes, IS did not differ between the metoprolol and control groups (Fig. 1c). Similar results were obtained for IS estimated from peak CK (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and when the analysis was restricted to patients with a fully occluded artery on angiography (pre-PCI thrombolysis MI (TIMI) 0-1, 88 patients: 46 control; 42 metoprolol) (Fig. 1C). CMR-measured MVO, another independent predictor of long-term mortality29, was also significantly reduced by pre-reperfusion i.v. metoprolol only in Arg/Arg389 patients (median [Q1, Q3] MVO: 4.110 % [0.000, 13.03 %] vs. 11.44 % [5.556, 18.62 %] in Arg/Arg389 metoprolol vs Arg/Arg389 control group patients; P < 0.05) (Fig. 1d). The same outcome was seen with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), which was significantly higher after metoprolol treatment only in homozygous Arg389 carriers (median [Q1, Q3] LVEF: 49.00 % [43.23, 57.18 %] vs. 45.20 % [32.50, 64.90 %] in Arg/Arg389 metoprolol vs Arg/Arg389 control patients; P < 0.05) (Fig. 1e). IS attenuation and LVEF improvement were also evident in the second CMR evaluation at 6 months post infarction (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Baseline characteristics of patients randomized to metoprolol or control did not differ between genotype groups (Supplementary Table 1).

The Ser49Gly (rs1801252) genotype distribution was 82% Ser/Ser49, 13% Ser/Gly49, and 5% Gly/Gly49 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Because frequency of patients carrying 1 or 2 alleles of Gly49 was low, our study was limited when studying the Ser49Gly SNP in metoprolol’s cardioprotection. However, Ser49 variant was only protective when associated with Arg389, thus suggesting a key role of Arg389Gly polymorphism (Supplementary Fig. 2b-e).

Metoprolol inhibition of neutrophil migration depends on ADRB1 genotype

Metoprolol exerts its cardioprotective effect not only by reducing cardiac contraction and oxygen demand, but also by blocking neutrophil migration and thus reducing MVO during reperfusion24,30. We therefore next assessed how the ADRB1 Arg389Gly polymorphism influences this neutrophil-stunning effect in a chemokine-induced migration Transwell assay (Fig. 2a). Neutrophils for this analysis were obtained from blood donated by healthy volunteers. The frequencies of the Arg389Gly (rs1801253) variants in this group were 46% Arg/Arg389, 49% Arg/Gly389, and 5% Gly/Gly 389 (Fig. 2b), and baseline characteristics did not differ according to genotype (Supplementary Table 2).

A CXCL1-induced transwell migration experimental set-up. B Distribution of the Arg389Gly single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (rs1801253) in healthy volunteers. C Representative flow cytometry plots illustrating reduced migration in the presence of metoprolol of neutrophils (CD45 + CD66b+ cells) from a volunteer with the Arg/Arg389 beta-1 adrenergic receptor (ADRB1) genotype. Negative, no CXCL1; Positive, CXCL1 but no metoprolol (vehicle). D CXCL1-induced neutrophil migration in all volunteers and stratified by ADRB1 389 phenotype. Each biological cell condition was run with 2 technical replicates. n = 19 Arg/Arg389 and n = 22 Arg/389Gly + Gly389 volunteers. To allow comparison between experiments, neutrophil migration for all treatments was normalized to the mean positive-control value (CXCL1+vehicle) in each independent assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD and compared using a one-way ANOVA and Friedman post-hoc multiple comparison test for paired samples. Differences were deemed statistically significant at P < 0.05. E Modeling of metoprolol binding by the Arg389 and Gly389 human ADRB1 variants. Ligand-free conformations are shown in gray (Arg389) and yellow (Gly389), and the metoprolol-bound conformations are shown in light blue. Images were obtained with the PyMOL molecular visualization system. F In silico analysis of metoprolol docking with the human Arg389 and Gly389 ADRB1 variants, showing energy of complex and energy of interface (Rosetta Energy Internal Units) and cavity size (Å2). Metoprolol binding to Gly389 is unstable relative to Arg389 (energy of complex: −482.89 vs. −1263.53; energy of interface: −16.214 vs. −19.574, respectively), implying rapid displacement from the receptor. G The comparative analysis of Molecular Dynamics simulations for the Gly389 and Arg389 ADRB1 variants bound to metoprolol showed relevant differences in the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) profile. H The evaluation of the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) showed that the Gly389 ADRB1 bound to metoprolol exhibited higher fluctuations than the Arg389 variant, which suggested a greater molecular motion and a more unstable binding to the drug. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Human neutrophils were exposed across Transwell filters to the chemoattractant CXCL1 in the presence or absence of metoprolol (10 µM), and the number of cells migrating across the membrane was quantified by flow cytometry after 90 min. Given that only one volunteer was homozygous for the Gly389 allele, this person was included in the Arg/Gly389 genotype for comparison with the Arg/Arg389 group. Among the Arg/Arg389 carriers, metoprolol inhibited baseline neutrophil migration towards CXCL1 by ≈ 20% (P < 0.05), whereas no effect was observed on neutrophils from Arg/Gly389 carriers (Fig. 2c, d, Supplementary Fig. 3a). Furthermore, genotype had no effect on neutrophil migration along the CXCL1 gradient in the absence of metoprolol, in line with data from the ADRB1-genotyped METOCARD-CNIC patients showing no influence of ADRB1 genotype on IS in the control group not receiving metoprolol (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c).

The ADRB1 Gly389 variant forms an unstable complex with metoprolol

In silico docking studies using the PPM server, which provides accurate modeling of protein position and orientation in the membrane, revealed a striking difference in metoprolol-binding stability between the Arg389 and Gly389 human ADRB1 variants (energy of complex, −1263.53 vs. −482.89; energy of interface, −19.57 vs. −16.21, in Rosetta Energy Internal Units) (Fig. 2e, f). Moreover, the model revealed that the Gly389 ADRB1 variant has a smaller drug binding pocket and a smaller internal cavity, and these parameters were not significantly affected by the presence of metoprolol. This computational data indicates that metoprolol forms an unstable complex with Gly389 ADRB1 and is therefore likely to be rapidly displaced.

To further explore these results, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations were run for the in-silico models of Gly389 and Arg389 human ADRB1 with and without metoprolol. The comparative analysis showed relevant differences in the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) profile. In the case of Arg389 ADRB1 (Fig. 2g), the cavity showed a strong stabilization with metoprolol, which was closely bound to the protein along the trajectory. For the Gly389 ADRB1 (Fig. 2h), the core and cavity displayed a similar behavior to the Arg389 form. However, in this scenario, metoprolol had low initial binding, which increased along the trajectory and showed a strong stabilization around 60% (Supplementary Movies 1–4).

The Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) profile indicates how much the residues of the protein fluctuate from their original mean positions during MD simulation. The Gly389 ADRB1 bound to metoprolol exhibited higher fluctuations than the Arg389 variant, which suggested a greater molecular motion and a more unstable binding to the drug (Fig. 2i, j).

To validate our in-silico results, recombinant protein expression in HEK293 cells was used to produce and purify both variants of the human ADRB1 (Arg389 and Gly389) (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c). Then, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) binding studies were conducted using aliquots of the affinity-purified TwinStrep-His10-tagged Arg389 or Gly389 human ADRB1. Metoprolol showed a strong affinity (KD nM) for both forms, which was around 15 times higher for the Arg389 variant. This was particularly due to the increase association rate constant (ka) for metoprolol binding to Arg389 (1.10 × 106 M−1 s−1) compared to Gly389 (1062 M−1 s−1), which could speed the onset of the blockade effect on the Arg389 (Supplementary Fig. 4d-e). These outcomes reinforce our in-silico results and strongly support our efficacy results showing a cardioprotective effect of metoprolol in Arg/Arg 389 patients.

Metoprolol-induced cardioprotection shows time-of-day variations

Given the major circadian variations in neutrophil biology13,31,32, we next examined the full METOCARD-CNIC trial cohort data (220 patients: metoprolol, n = 108; control, n = 112) to determine if the cardioprotective effect of metoprolol was time-of-day–dependent. The time-of-day of MI onset was divided in 4 periods based on previous research11 (Fig. 3a, b). Consistent with previous studies10,11, the MI onset was more frequent during the morning period, spanning the dark-to-light transition (P2, 6 am-noon) (Supplementary Table 3).

A METOCARD-CNIC trial timeline for the full study population of 220 patients (112 control, 108 metoprolol). B Time-of-day of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) onset in the full METOCARD-CNIC study population and in patients with pre-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) TIMI grade 0–1 (178 patients: 92 control, 86 metoprolol). Patients were assessed for infarct size (IS) by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging 1 week after acute myocardial infarction as per the standard METOCARD protocol. C–E CMR analysis of cardiac anatomy and function at 1-week post-reperfusion stratified by time of STEMI onset in all patients (left) and in patients with pre-PCI TIMI grade 0–1 (right). Linear regression models were used to evaluate the association between time-of-day of myocardial infarction and IS (necrotic tissue, g) (C); microvascular obstruction (MVO, % of left ventricle) (D); and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, %) (E), after adjusting for the following cofounders: sex, age, diabetes mellitus, ischemia duration, and pre-PCI TIMI. Patient numbers (C | M) = P1, 21 | 17; P2, 39 | 32; P3, 28 | 33; and P4, 24 | 26 for the full cohort and P1, 18 | 14; P2, 30 | 25; P3, 23 | 27; and P4, 21 | 21 for patients with pre-PCI TIMI grade 0 to 1. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Differences were deemed statistically significant at P < 0.05. C control group, M metoprolol group, CK creatine kinase. Period 1 (P1), from midnight to 6 am; period 2 (P2), from 6 am to noon; period 3 (P3), from noon to 6 pm; and period 4 (P4), from 6 pm to midnight. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

A significant increase in MI incidence was observed in P2 (X2 goodness of fit test; P = 0.012). However, time-of-day differences in terms of IS were not seen. Metoprolol exerted significant cardioprotection only in patients with MI onset within the first hours of the light period (P2 median IS on CMR 22.00 g [Q1, Q3: 10.20–30.00 g] in the metoprolol group vs. 29.55 g [Q1, Q3: 17.28–42.93 g] in control; P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained when the analysis was restricted to patients presenting with a fully occluded artery (pre-PCI TIMI 0-1) (Fig. 3c) and when IS was estimated with the surrogate biomarker peak CK (Supplementary Fig. 5a). MVO, another well-established predictor of poor long-term outcome29, was evaluated on day-7 by CMR. Consistent with the IS data, MVO was significantly reduced in metoprolol-treated patients only when MI onset occurred in P2 (P2 median MVO 7.74 % [Q1, Q3: 0.15–13.4 %] in the metoprolol group vs. 9.67 % [Q1, Q3: 5.34–18.2 %] in control; P < 0.05) (Fig. 3d). Analysis of LVEF at 7 days post-reperfusion showed the same pattern, with significant preservation in metoprolol-treated patients only for MI onset during P2 (Fig. 3e). Moreover, the effect of MI-onset time was maintained in the 6-month follow-up assessment of IS and LVEF, with metoprolol associated with improved systolic function only in patients with MI onset in P2 (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

The interaction between genotype and time-of-day variations was also evaluated. The number of Arg/Arg389 and Gly389 carriers was consistent among the different circadian periods (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The cardioprotective effect of metoprolol was restricted to the onset of the light cycle (P2) in Arg/Arg389 patients, but not in Gly389 carriers (Supplementary Fig. 6b-e). These results reinforced our previous data and offered a broader view from the precision medicine perspective, although they should be carefully taken due to the fewer number of patients in each group.

ADRB1 modulation by metoprolol and therefore cardioprotection is restricted to the onset of the light phase

Metoprolol protects against myocardial IRI, as well as other conditions characterized by exacerbated inflammation such as acute lung injury and peritonitis, by inhibiting structural rearrangements in neutrophils and thus preventing their interaction with other cells and their infiltration of target tissues24,30,33. We therefore next investigated if the time-of-day restriction in the cardioprotective effect of metoprolol was secondary to an attenuation of its effect on neutrophil biology. For this analysis, we induced myocardial IRI at different times of day in WT mice by occluding the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery for 45 min followed by ligature release to produce reperfusion (Fig. 4a). The administration of i.v. metoprolol (12.5 mg/kg) 10 min before reperfusion markedly limited IS (expressed as percentage of the area-at-risk, AAR) when IRI was induced during the onset of the light period (zeitgeber time (ZT) 1-5) (metoprolol, 18.0 ± 2.57%; vehicle, 34.6 ± 2.94%; P < 0.005). Metoprolol showed a milder protective effect on IS when IRI was induced later in the light cycle (ZT 9-13) (metoprolol, 23.7 ± 0.96%; vehicle, 32.5 ± 0.84%; P < 0.01) but had no effect on IRI induced in the dark period (ZT 18-22) (metoprolol, 13.8 ± 1.47%; vehicle, 14.8 % ± 1.22%; P = 0.862) (Fig. 4b, c, Supplementary Fig. 7). Metoprolol administration had no time-of-day–dependent effect on total immune cell and platelet numbers in peripheral blood (Supplementary Fig. 8). Induction of myocardial IRI in LysM-GFP+ mice (carrying a GFP reporter in myeloid-derived cells) revealed that the cardioprotective effect of metoprolol during ZT 1-5 was associated with attenuated LV infiltration by neutrophils (LysM-GFP+Ly6G+, but not LysM-GFP+Ly6G− cells) (metoprolol, 0.67 ± 0.07%; vehicle, 1.00 ± 0.06%; P < 0.005) and reduced co-aggregate formation by neutrophils and platelets (Ly6G+CD41+ cells) in blood at 24 h post-reperfusion (metoprolol, 47.1 ± 9.50%; vehicle, 77.6 ± 2.73%; P < 0.005). Again, no effect was observed when MI was induced in the dark phase (Fig. 4d, e, Supplementary Fig. 9).

A Mouse model of myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI) induced at different times of the day (ZT 1-5, ZT 8-13, and ZT 18-22) for the estimation of area-at-risk and infarct size (NA/AAR, %) by Evans Blue and TTC staining. WT mice were treated 10 min before reperfusion by i.v. injection of vehicle (0.9% NaCl) or metoprolol (12.5 mg/kg). B Representative images of 1-mm-thick transverse LV slices showing AAR (negative for Evans Blue) and the infarcted area (extent of necrosis; TTC-negative area) after IRI induced at different times of day. C Histological analysis of IS in mice subjected to IRI and randomized to receive vehicle or metoprolol before reperfusion. Vehicle, n = 12 for ZT1; n = 10 for ZT 9-13; n = 8 for ZT 18-22. Metoprolol, n = 10 for ZT 1-5; n = 9 for ZT 9-13; n = 8 for ZT 18-22. D Flow cytometry analysis of neutrophil infiltration of the LV 24 h after induced IRI in LysM-GFP reporter mice at ZT 1-5 (control, n = 5; metoprolol, n = 4) and ZT 18-22 (control, n = 5; metoprolol, n = 6). LysM-GFP+Ly6G+ cells were counted in dispersed LV cells. Representative plots are shown. E Flow cytometry analysis of co-aggregate formation between neutrophils and platelets (Ly6G+CD41+ cells) in peripheral blood 24 h after induced IRI in LysM-GFP reporter mice at ZT 1-5 (control, n = 9; metoprolol, n = 6) and ZT 18-22 (n = 5 per condition). Representative plots are shown. F Myocardial IRI model in mice lacking Adrb1 in neutrophils (Mrp8-Cre-/+ Adrb1FLOX/FLOX, KO) and littermates (Mrp8-Cre-/- Adrb1FLOX/FLOX, WT). G Representative images of Evans Blue and TTC staining in 1 mm-thick transverse LV slices. Histological analysis of (H) AAR (% LV) and (I) IS (NA/AAR, %) in mice lacking Adrb1 (blue) or littermates (red) 24 h after induced IRI at ZT 1-5 (n = 10 per condition) and ZT 18–22 (n = 4 for WT; n = 9 for KO). Squares represent individual mice. (C–E, H, I) Data are presented as mean ± SD and compared by 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney test, for normally or non-normally distributed data, respectively. Differences were deemed statistically significant at P < 0.05. AAR, area-at-risk; IS, infarct size (NA/AAR, %); LV left ventricle, NA necrotic area, TTC triphenyl tetrazolium chloride, WT Wild-type, ZT Zeitgeber time. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To confirm the influence of ADRB1 on metoprolol-induced cardioprotection, we induced myocardial IRI in Mrp8-Cre-/+ Adrb1FLOX/FLOX mice, which specifically lack Adrb1 in neutrophils34 (Fig. 4f). When myocardial IRI was induced during ZT 1-5, the neutrophil-specific Adrb1-KO mice had smaller infarcts than their littermate controls (Adrb1-KO, 21.4 ± 3.21%; littermate controls, 39.4 ± 2.06%; P < 0.005) (Fig. 4g–i), and pre-reperfusion i.v. metoprolol had no additional effect on IS in the absence of the receptor (Supplementary Fig. 10). Neutrophil-specific Adrb1 deletion had no effect on IS when IRI was induced in ZT 18-22 (23.3% ± 2.36% vs 20.0 ± 2.65; P = 0.422) (Fig. 4g–i).

Time-of-day variations in the metoprolol-induced disruption of neutrophil dynamics

To confirm the changes in the effect of metoprolol on neutrophil infiltration capacity throughout the day, we investigated the influence of time-of-day on thioglycolate-induced peritonitis in mice. Metoprolol blocked the neutrophil-driven sterile inflammatory response in the peritoneal cavity when peritonitis was induced in the onset of the light cycle (ZT 1-5) (metoprolol, 10.1 ± 1.04 × 105 neutrophils/mL; vehicle, 15.2 ± 1.91 × 105 neutrophils/mL; P < 0.05). In contrast, metoprolol showed no ability to lessen neutrophil infiltration of the peritoneal cavity when peritonitis was induced at ZT 9-13 or ZT 18-22 (Fig. 5a–c, Supplementary Fig. 11).

A Experimental procedure for thioglycolate-induced peritonitis. Wild-type (WT) mice received i.v. metoprolol (12.5 mg/kg) or vehicle (0.9% NaCl) immediately after intraperitoneal thioglycolate administration at ZT 1-5, ZT 9-13, or ZT 18-22. B Representative flow cytometry plots illustrating reduced peritoneal infiltration by neutrophils (Ly6G+ cells) in mice treated with metoprolol after intraperitoneal thioglycolate administration in the morning (ZT 1-5). C Absolute numbers of neutrophils/mL in peritoneal infiltrate 6 h after thioglycolate injection in WT mice. Vehicle, n = 13 for ZT1; n = 8 for ZT 9-13; n = 9 for ZT 18-22. Metoprolol, n = 13 for ZT 1-5; n = 10 for ZT 9-13; n = 10 for ZT 18-22. D Experimental scheme for 2D intravital microscopy of neutrophil motility in inflamed cremaster muscle at ZT 5-9 and ZT 11-15. E Representative tracks of crawling neutrophils within inflamed cremaster vessels of mice treated with vehicle or metoprolol after intrascrotal TNFα injection in the indicated time frames. F Representative time-lapse images of platelets (CD41+ cells, red) interacting with polarized neutrophil uropod (CD62L+ domain, yellow) or leading edge (Ly6G+ domain, green). Arrowheads indicate interactions with the uropod domain. Scale bars: 10 µm. G Quantification (%) of platelet interactions with neutrophil uropod or leading edge. Vehicle, n = 25 different cells for ZT 5-9; n = 26 for ZT 11-15. Metoprolol, n = 22 different cells for ZT 5-9; n = 27 for ZT 11-15. 3 mice per condition. H Influence of the time of inflammation onset on 2D intravascular neutrophil motility parameters and their sensitivity to metoprolol treatment: velocity (µm/s), accumulated distance (µm), Euclidean distance (µm), and directionality. Vehicle, n = 43 different cells for ZT 5-9; n = 48 for ZT 11-15. Metoprolol, n = 35 different cells for ZT 5-9; n = 41 for ZT 11-15. 3 mice per condition. C, G, H Data are presented as mean ± SD and compared by 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney test, for normally or non-normally distributed data, respectively. Differences were deemed statistically significant at P < 0.05. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To directly visualize the effect of metoprolol on neutrophil migration, we examined the effect of TNFα-induced inflammation in mouse cremaster vessels by 2-dimensional (2D) intravital microscopy (IVM). Consistent with the myocardial IRI and peritonitis results, neutrophil kinetics were disrupted by metoprolol only when TNFα-mediated inflammation was induced in the light phase (ZT 5-9) (Fig. 5d–f). In these experiments, metoprolol also reduced the proportion of neutrophils interacting with platelets through the uropod and increased interactions through the leading edge (Fig. 5g,h). Metoprolol had no effect on neutrophil kinetics or the mode of neutrophil interaction with platelets was affected by metoprolol when cremaster muscle inflammation was induced later in the day (ZT 11-15) (Fig. 5d–h). Time-of-day differences in neutrophil kinetics were also abrogated in mice lacking neutrophil expression of Adrb1 (Supplementary Fig. 12, Supplementary Movies 5-10). Experiments were not performed at ZT 18-22 as 12-h light–dark cycle could not be inverted in the IVM facility.

Circadian markers (CD62L, CXCR2, CXCR4 and CD11b)31,32 and leukocyte counts were evaluated in Mrp8-Cre-/+ Adrb1FLOX/FLOX mice and their WT littermates. Our results confirmed that the lack of the receptor had no influence on circadian neutrophil phenotype (Supplementary Fig 13a) or leukocyte counts (Supplementary Fig 13b). Light-scattering (SSC-A) values for neutrophils were also measured by flow cytometry. Our results showing a decrease in the granularity of neutrophils (indicated by the side scatter by flow cytometry) are consistent with previous results35. By contrast, no differences were seen between both genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 13c).

Discussion

The results of this study provide robust evidence that light–dark cycles and individual genetics play important roles in the cardioprotective response to the selective ADRB1 blocker metoprolol during acute MI. In the ADRB1-genotyped patients from the METOCARD-CNIC trial, administration of i.v. metoprolol before reperfusion was cardioprotective only in patients carrying 2 Arg389 ADRB1 alleles, demonstrating that the Arg389Gly (rs1801253) polymorphism is a good predictor of the response to metoprolol. Furthermore, the beneficial effect of metoprolol injection was evident only for MI onset at the start of the light cycle, thus suggesting that the ability of metoprolol to induce neutrophil stunning coincides with the period of enhanced neutrophil activity.

Our previous reports demonstrated that metoprolol-induced selective blockade of ADRB1 in neutrophils has a unique effect on neutrophil activity that results in the amelioration of acute conditions characterized by exacerbated inflammation, such as myocardial IRI24,30, stroke34, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)30,33. The existence both of ADRB1 polymorphic variants and of light–dark patterns in MI and neutrophil activity prompted us to investigate if the protective effect of i.v. metoprolol against acute neutrophil-driven conditions might be restricted to patients with a specific ADRB1 genotype and to a specific time of the day. In contrast to the extensive application of pharmacogenetics and chronotherapy to improve the management of chronic CV disorders, little attention has been paid to the potential application of these approaches to the management of acute CV conditions2. In the present study, we focused on myocardial IRI as a model disease setting, but the results are likely applicable to any acute condition in which exacerbated inflammation plays a crucial role.

The clinical response to drug therapy is a complex phenomenon that emerges from the interaction of the drug used, patient comorbidities, and environmental factors. This complexity results in notable interindividual heterogeneity in the responses to and efficacy of drugs prescribed for CV conditions. Genotype-related interindividual differences in drug response can derive from sequence variants in genes encoding drug-metabolizing enzymes (e.g. CYP2C19 for clopidogrel), drug transporters (e.g. SLCO1B1 for statins), or drug targets (e.g. VKORC1 for warfarin). Although pharmacogenetic evidence is accumulating for other CV medications, the data are insufficient to support the use of pharmacogenetics as a guide to prescription in clinical practice2.

Based on the specific and unique cardioprotective effect of metoprolol achieved through neutrophil stunning21,22,24,30, current clinical practice guidelines for ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) management recommend early i.v. administration of metoprolol in preference to other beta-blockers25. However, there is still a lack of interventions for reducing IS that show a solid clinical benefit in terms of endpoint reductions. The complexity of translation from animal models to human trials highlights the need to consider the genetic background of animals used in experimental settings in relation to patient genetics36.

ADRB1 is a major target of CV pharmacotherapy, and intense efforts are underway to take account of ADRB1 polymorphic variants in the development of individualized therapeutic approaches37. SNPs in ADRB1 have been shown to modulate the response to beta-blocker therapy, with the clinically most significant ADRB1 polymorphism being Arg389Gly (rs1801253)2. The Arg/Arg389 genotype is strongly associated with a more potent clinical effect of beta-blockers for chronic indications. The results of our study reinforce the relevance of the Arg389Gly ADRB1 polymorphism to the prediction of acute responses to metoprolol in STEMI patients. Only Arg/Arg389 homozygotes were good responders and benefited from metoprolol-induced cardioprotection (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1).

The genotype-dependent response to metoprolol in the context of acute conditions, such as acute MI, coincided with a restriction of metoprolol-inhibited neutrophil migration to Arg/Arg389 healthy individuals (Fig. 2a–c). In-silico docking analysis and MD simulations revealed a rapid drug-receptor association and stronger stabilization of the Arg389 ADRB1 by metoprolol compared to the Gly389 variant, which would explain the weaker response to the drug observed in the latter. SPR studies also support these conclusions. These results may also shed light on the overall lack of responsiveness to beta-blockers in chronic clinical scenarios in which beta-blockers exert a drug-class effect (Fig. 2d–j, Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Movies 1-4)5,6,38,39,40.

Although the present work focused on genetic variations affecting pharmacodynamics of metoprolol, polymorphic variations can significantly alter drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and clearance (so-called ADME), leading to variability in drug efficacy and toxicity. In fact, polymorphisms in CYP2D6 result in substantial variability in beta-blocker pharmacokinetics, particularly for metoprolol (level IA)41,42,43,44,45. Despite not being evaluated, CYP2D6 metabolizer phenotype of patients should not be excluded as an important determinant in the response to metoprolol.

Multiple features of CV physiology and pathophysiology show circadian rhythms, primarily attributed to time-of-day control of neurohumoral axes (including cortisol, melatonin, catecholamines, and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system), as light is the most important cue for entraining the clock with the environment. Therefore, arterial blood pressure, heart rate, endothelial function, platelet aggregation, and blood viscosity all increase in the early morning, as does the onset of adverse cardiac events46,47. These rhythms also play an important role in regulating most reproductive hormones in females and males48. Moreover, alterations in circadian clock genes, such as BMAL1 and CLOCK, lead to blood pressure dysregulation and contribute to hypertension49. On this point, polymorphisms in the CLOCK gene are linked to increased susceptibility to metabolic syndrome, type 2-diabetes, and CVD. In addition, circadian misalignment, as common in shift workers, is associated with a higher prevalence of hypertension and other CV risks50,51.

Light–dark cycles also affect the production and activity of myeloid cells (granulocytes and monocytes). Neutrophil numbers in peripheral blood follow a circadian rhythm, which also affects circulating neutrophil phenotype31 and the way these cells are recruited to tissues13. Neutrophil phenotype is defined by the expression of surface molecules (CD62L, CXCR4 and CXCR2) whose expression follows a circadian pattern31,32,52.

Human and mouse studies have shown that infarcts tend to be larger when MI occurs in the light cycle11,32. Consistent with these previous results, we also found a significant increase in MI incidence in P2; however, time-of-day differences in terms of IS were not seen, probably because of the inclusion of anterior wall MIs, or different primary endpoints and techniques for IS evaluation compared to other studies. Our current findings show that the clinical cardioprotection provided by metoprolol injection is restricted to MI with an onset in the P2 time-window (6 am-noon) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 4). The fact that metoprolol is cardioprotective when the incidence and IS are higher underscores the significant benefit of this therapeutic intervention. However, a smaller proportion of enrolled females ( ≈ 15%) and the lack of experimental results in female mice limits the degree of generalizability of our results to the overall population, as sex differences in circadian biomarkers have been reported48. Therefore, sex differences in the response to metoprolol should not be completely ruled out without a more extended validation.

Time-of-day variations in the cardioprotective effect of metoprolol were confirmed in the mouse IRI model, in which cardioprotection declined progressively throughout the day from a peak within the first hours of the light period (ZT 1-5, equivalent to P2 in the human study). The restriction of metoprolol blockade of LV neutrophil infiltration to MI induced in ZT 1-5 (Fig. 4a–e) likely indicates dependence of this effect on neutrophil reprogramming during the dark cycle. The single-cell in vivo 2D IVM analysis confirmed that neutrophils became intrinsically unresponsive to metoprolol at dark-cycle onset (Fig. 5d–h). The light-dependent effect of metoprolol on neutrophil recruitment was also observed after the induction of acute peritonitis (Fig. 5a–c, Supplementary Fig. 11).

Moreover, the Mrp8-Cre-/+ Adrb1FLOX/FLOX mice, engineered to constitutively lack Adrb1 in neutrophils, were cardioprotected against IRI when induced within the first hours of the light cycle, and metoprolol had no additional protective effect in these animals (Fig. 4f–i). This result confirms that metoprolol protects against IRI by neutrophil stunning achieved by switching off Adrb1 signaling24. Neutrophil unresponsiveness was again evident, since absence of Adrb1 made no difference to IS when IRI was induced in the dark phase (Supplementary Fig. 10)34.

Similarities between our mice and human studies might disagree with the fact that the morning time for mice is opposite to humans, which brings differences regarding feeding/activity phases and blood leukocytes32,35. Neutrophils exhibit an intrinsic program (“timer”) controlled by the molecular clock that regulates cell properties, including the phenotypic change from “fresh” to “aged” neutrophils31,32. Importantly, similar diurnal changes have been found in humans, suggesting the conservation of this phenomenon across species that aligns neutrophil phenotype with the body’s light–dark cycle32. Although some models have proposed extrinsic factors (e.g. gut microbiota53) as potential drivers of neutrophil aging, these diurnal patterns persisted in constant darkness32. In fact, time-of-day differences in neutrophils were reproduced in mice with neutrophil-specific deficiency in Arntl (nighttime, “fresh”) or Cxcr4 (daytime, “aged”). Mice with aged circulating neutrophils (ZT5 or Cxcr4 deficient) exhibited larger IS and higher death rates, due to severe thrombo-inflammatory reactions following myocardial IRI32. The more “aged” neutrophils infiltrate the heart at ZT5 (equivalent to morning in humans), the more worsening remodeling and increasing IS. Here, our results showed that metoprolol administration results in cardioprotection and neutrophil stunning at ZT1-5, when circulating neutrophils are more abundant and aged, and IS are larger. Interestingly, in a model of non-reperfused myocardial infarction (permanent coronary ligation), the exacerbated infiltration of neutrophils at ZT13 accounted for increased cardiac damage12. On the contrary, both mice and humans exhibit larger IS in the onset of the light cycle in the context of reperfused myocardial infarction (IRI), thus suggesting that the type of injury (with/out reperfusion) follows distinct patterns13.

Key molecules modulating the effect of metoprolol also exhibit a circadian expression pattern. The expression and sensitivity of ADRB1 are under circadian control, particularly in tissues like the heart54 and pineal gland55. Downregulation of circadian clock genes led to reduced ADRB1 expression, thus connecting the core clock machinery to the receptor expression56. Notably, time-of-day variations in IRI were lost upon genetic ablation of the cardiomyocyte circadian clock, which revealed its crucial role in myocardial tolerance to IRI57. Although circadian expression or density of ADRB1 in neutrophils has not been explored, experiments in Mrp8-Cre-/+ Adrb1FLOX/FLOX mice confirmed that the lack of the receptor had no influence on neutrophil phenotype at ZT1, when its absence conferred cardioprotection (Supplementary Fig. 13). In addition, time-related changes also impact pharmacokinetics (chronopharmacokinetics) and can influence the activity of certain CYP450 enzymes such as CYP3A4, whose activity tends to be more active at night58. The CYP2D6 metabolizer profile of patients and its chronoregulation are crucial features to be further investigated in the context of beta-blocker therapy.

Differences in the prevalence of less responsive ADBR1 variants may provide a mechanistic explanation for ethnic differences in the response to beta-blockers27, and this should be taken into consideration in retrospective analyses and the design of prospective clinical trials36. Even though the time currently required for SNP testing rules out the possibility of prescribing pre-reperfusion metoprolol to STEMI patients on the basis of ADRB1 genotype, this strategy could be used in other clinical scenarios. One example is ARDS, a condition in which i.v. metoprolol has been shown to provide clinical benefit by reducing lung inflammatory infiltration33. The ongoing MAIDEN clinical trial (NCT05847517) will validate these benefits of metoprolol in a much larger population of patients admitted with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Methods

Study population

This study reports non–pre-specified exploratory outcomes from the METOCARD-CNIC clinical trial (NCT01311700), which was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Clinico San Carlos University Hospital (ref. 10/020). Patients provided written consent. All primary outcomes from this trial have already been published59. The METOCARD-CNIC clinical trial recruited patients with anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing mechanical reperfusion by primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within 6 h of symptom onset. Patients were randomized to receive i.v. metoprolol (15 mg) or no drug (control) before reperfusion. The trial also evaluated a pre-specified subgroup of patients presenting with a fully occluded artery (pre-PCI thrombolysis myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow grade 0-1), which represents the target cohort for evaluating the clinical effect of metoprolol against myocardial IRI. The exclusion criteria21,59 included previous treatment with beta-blockers.

Time of day and infarct size in METOCARD trial patients

To evaluate the impact of the time-of-day of MI onset on the cardioprotective effect of metoprolol against IRI, 4 6-h periods were defined11: period 1 (P1), from midnight to 6 am; period 2 (P2), from 6 am to noon; period 3 (P3), from noon to 6 pm; and period 4 (P4), from 6 pm to midnight11.

Human ADRB1 genotyping

A subgroup of 102 consecutive patients enrolled in the METOCARD-CNIC study was genotyped for the Arg389Gly (rs1801253; 1165 G > C) and Ser49Gly (rs1801252; 145 A > G) SNPs in ADRB1. Protocols were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Carlos III Hospital (ref. P15/12). Patients provided written consent.

All these patients underwent the CMR study, and the subgroup contained equal numbers of patients receiving metoprolol and in the control group (51 each). Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from whole blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen), quantified with a NanoDrop 1000 Spectophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific), and genotyped by probe-based PCR with the TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay for human samples (Applied Biosystems, ThermoFisher Scientific). Genotyping was performed by the CNIC Genomics Unit.

Volunteer recruitment

A total of 51 healthy volunteers aged from 18 to 65 were recruited for blood drawing in the early morning (between 8 am and 9 am). All volunteers provided written informed consent. Protocols were approved by the ISCIII Research Ethics Committee (ref. CEI PI 74_2017-v2). Genotyping was performed as described above. Blood pressure, heart rate, height, and weight were measured before blood collection and used to calculate body mass index.

Cardiac magnetic resonance

Patients were examined by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) 5 to 7 days after myocardial infarction (MI) and at 6-month follow-up. Images were acquired with a 3.0 Tesla magnet (Achieva Tx, Philips Medical Systems) with vector cardiographic gating and a dedicated cardiac 32-channel phased-array surface coil. A detailed description of the magnetic resonance (MRI) protocol and analytical methods is reported elsewhere21,59. The parameters determined in the 1-week CMR study were left ventricular (LV) volume, LV mass, LV ejection fraction (LVEF), the extent of myocardial edema and necrosis, and the extent of microvascular obstruction (MVO). Human infarct size (IS) was measured as the mass of necrotic myocardium (grams of LV tissue), defined by the extent of abnormal gadolinium enhancement. For the determination of MVO, a delayed enhancement imaging was performed 10 min after gadolinium contrast injection, using a T1-weighted 2-D Inversion Recovery Turbo Field Echo (2D IR-TFE) sequence. MVO was defined as black-hypoenhanced signal within the bright-hyperenhanced regions (absence of contrast wash-in inside the delayed gadolinium-enhanced area) and was quantified both as grams of LV tissue and, to correct for IS, as a percentage of the infarcted area (total late gadolinium enhanced area). The parameters determined at 6-month CMR were LV volume, LV mass, LVEF, and the extent of myocardial necrosis (IS)22.

CMR analysis was undertaken by operators blinded to treatment allocation at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares Carlos III (CNIC). Myocardial necrosis and MVO were quantified by semiautomatic delineation with dedicated software (QMass MR 7.6; Medis, Leiden, the Netherlands).

Mouse procedures

All experimental and other scientific procedures with animals conformed to EU Directive 2010/63EU and Recommendation 2007/526/EC, incorporated into Spanish law under Real Decreto 53/2013. Animal protocols were approved by the local ethics committee and the Animal Protection Area of the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Adult mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions in a temperature (22 ± 2 °C) and humidity (50 ± 10%)-controlled room, with a 12 h light–dark cycle at the CNIC animal facility. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All animal experiments were reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. Animal health and welfare were monitored daily throughout the study. At the endpoint, mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation.

Myocardial IRI and thioglycolate-induced peritonitis experiments were performed with 8–13-week-old wild-type (WT) male C57BL/6 (JOlaHsd) mice at zeitgeber times (ZT, 24 h notation used to mark the phase of a circadian cycle) ZT1-5, ZT8-13, and ZT18-22. ZT0 represented the beginning of the light period and ZT12 marked the start of the dark period. Therefore, ZT1-5 was equivalent to P2 in humans (from 7 am to 11 am), ZT8-13 to late P3-early P4 (from 2 pm to 7 pm), and ZT18-22 to P1 (from midnight to 4 am). The 12-h light–dark cycle was inverted for experiments in the dark phase. Because the 12-h light-dark cycle could not be either controlled or inverted, experiments using Intravital Microscopy (IVM) were performed at ZT 5-9 (equivalent to late P2-early P3) and ZT 11-15 (late P3-early P4). The intrascrotal administration of TNFα was done at ZT5 and ZT11, respectively.

Myocardial IRI was also performed in mice constitutively lacking Adrb1 in neutrophils (Mrp8-Cre-/+ Adrb1FLOX/FLOX) and their WT littermates (Mrp8-Cre-/- Adrb1FLOX/FLOX)34. Metoprolol-tartrate (12.5 mg/kg, M5391, Sigma) was administered by i.v. injection as in previous studies24,30. Mice were randomly allocated to the treatment (i.v. metoprolol or vehicle, 0.9% NaCl). Mouse body temperature was strictly controlled throughout experiments. LysM-GFP reporter mice were used to assess the number of myeloid cells infiltrating the left ventricle (LV) 24 h after post-myocardial IRI24. The effect of i.v. Metoprolol on neutrophil behavior at different times of the day was investigated by IVM in Mrp8-Cre-/+ Adrb1FLOX/FLOX mice and their WT littermates.

Mouse model of myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury

Male 8-13-week-old mice were subjected to 45 min occlusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. IS, neutrophil–platelet interactions, and neutrophil infiltration were assessed 24 h after reperfusion. For the ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI) procedure, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of an anesthetic cocktail of atropine sulfate (1 mg/kg; B. Braun, 1 mg/mL), xylazine hydrochloride (20 mg/kg; Rompun Bayer, 20 mg/mL), and ketamine (100 mg/kg; Anesketin Dechra, 100 mg/mL). Fully anesthetized animals were intubated and temperature controlled throughout the experiment at 36.5 °C to prevent hypothermic cardioprotection. Access was made via an intercostal space to minimize incision size and reduce wound healing time. The LAD was then ligated with a nylon 8/0 monofilament suture thread for 45 min. Total coronary artery occlusion (ST-segment elevation) throughout the 45 min ischemia was confirmed by electrocardiography (MP36R, Biopac Systems Inc.)24. Mice were randomized 10 min before reperfusion onset to receive a single i.v. bolus of metoprolol (12.5 mg/kg) or vehicle (0.9% NaCl; saline) via retro-orbital injection into the venous sinus. At the end of the 45 min ischemia period, the suture thread to reperfuse the LAD, and the intercostal space was closed. Gas flow was maintained at 100% O2, and animals were analgesized with subcutaneous buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg).

Mouse infarct size

At 24 h post-reperfusion, mice were re-anesthetized and re-intubated, and the LAD coronary artery was re-occluded by ligating the suture in the same position as for the original infarction. Animals were then sacrificed and 1 ml of 1% Evans Blue dye (Sigma) was infused i.v. to delineate the area-at-risk (AAR, corresponding to the myocardium lacking blood flow and thus negative for blue dye staining). The LV was isolated, cut into transverse slices (5–7 1 mm slices per LV), and both sides were imaged. To delineate the infarcted (necrotic) myocardium, slices were incubated in a solution of triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma) at 37 °C for 15 min. Slices were then rephotographed and weighed, and regions negative for both Evans Blue staining (AAR) and TTC (infarcted myocardium) were quantified with ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Percentage values for AAR and necrotic (infarcted) myocardium were independently mass corrected for each slice. The AAR was determined as the percentage mg:mg ratio of AAR to LV, and IS was determined as the percentage mg:mg ratio of necrotic myocardium to AAR.

Left ventricle enzymatic digestion for flow cytometry analysis

To evaluate the number of neutrophils infiltrating the LV at 24 h post-reperfusion, the LAD coronary artery occlusion procedure was performed with LysM-GFP reporter mice24. Mice were killed and transcardially perfused with PBS, and LVs were removed and digested with a cocktail composed of collagenase/hyaluronidase (STEMCELL #07912) and DNase I (STEMCELL #07900) in RMPI for 30 min with shaking at 37 °C. Cells were filtered through 40 µm cell strainer (Falcon #352340) and incubated with a Dylight-650-conjugated anti-mouse Ly6G (BE0075-1, Clone 1A8, Bioxcell). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (D8417, Sigma), and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for 30 s at constant flow (see below). The number of immune cells was calculated per mg of LV tissue. Neutrophils were detected as LysM-GFP+Ly6G+ cells and monocytes as LysM-GFP+Ly6G- cells.

Neutrophil–platelet interactions in peripheral blood

Neutrophil–platelet interactions were assessed in peripheral blood obtained at 24 h post-reperfusion. Blood samples were citrated and immediately included in ThromboFix Platelet Stabilizer (6607130, Beckman Coulter, Life Sciences), which preserves platelets in their state at the time of blood extraction and can be used in conjunction with dye-conjugated anti-platelet monoclonal antibodies for flow cytometry analysis. After a minimum of 1 h, erythrocytes were lysed with hypotonic buffer (Red Blood Lysis buffer). Platelets (CD41+ cells) and neutrophils (Ly6G+ cells) were detected by flow cytometry (see below), and double-positive signals (CD41-Ly6G+ cells) were identified as neutrophil–platelet co-aggregates. The number of neutrophil–platelet co-aggregates was calculated relative to total Ly6G+ cells30.

Thioglycolate-induced peritonitis

The ability of metoprolol to inhibit neutrophil recruitment at different times of the day (ZT 1, ZT 9, and ZT 18) was assessed with a well-established model of thioglycolate-induced peritonitis30. Wild type mice were given intraperitoneal injections of 1 ml sterile thioglycolate (BD211716) and immediately randomized to receive a single i.v. bolus of saline or metoprolol (12.5 mg/kg). After 6 h, animals were sacrificed, and 2 mL PBS was i.p. injected and distributed manually for 30 s to detach circulating cells that had infiltrated the peritoneum. Another 8 mL PBS was then injected to facilitate collection of the peritoneal exudate. The exudate was collected, and 1 mL samples were gently centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min, and the cells were washed with PBS and incubated for 30 min with Dylight-650-conjugated anti-mouse Ly6G (BE0075-1, Clone: 1A8, Bioxcell). After the incubation, cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (D8417, Sigma). All samples were filtered through a 100 µm cell strainer (352360, Falcon) before flow cytometry analysis for 30 s at constant flow. Neutrophil recruitment efficiency was calculated for each individual animal as neutrophils/mL of exudate.

Transwell assay of chemokine-induced migration

The capacity of neutrophils to migrate toward the chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 1 (CXCL1) was assessed in a Transwell assay24,30. Blood collected from healthy volunteers at the CNIC was filtered through a 100 µm cell strainer (352360, Falcon), and erythrocytes were lysed with hypotonic buffer (RBL buffer). Leukocytes were resuspended in RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum and either vehicle (PBS 1X) or 10 μM metoprolol-tartrate. Transwell inserts (6.5 mm, 5.0 μm pore size; 3421, Corning Costar Corporation) were pretreated with 50 μl RPMI for 15 min and placed in 24-well culture plates before seeding cells. The lower compartments (wells) were filled with 600 μL RPMI containing 0.02 ng/μL CXCL1 (275-GR, R&D Systems) to induce chemoattractive movement (positive control) or with medium lacking CXCL1 to assess spontaneous migration (negative control). After incubation of the culture plates at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 90 min, cells were collected from the lower compartment, and the number of neutrophils (CD45 + CD66b+ cells) was counted by flow cytometry (see below). Each condition was run with 2 technical replicates. To allow comparison between experiments, neutrophil migration in each experiment was normalized to the mean positive-control value.

Flow cytometry

Neutrophil infiltration of the LV 24 h after myocardial I/R and of the peritoneum 6 h after thioglycolate-induced inflammation was assessed by incubating cells with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated and Dylight-650-conjugated anti-mouse Ly6G (BE0075-1, Clone 1A8, Bioxcell), respectively, with DAPI used to assess viability (D8417, Sigma). Neutrophil–platelet interactions in peripheral blood were assessed by fixing cells with ThromboFix Platelet Stabilizer and incubating cells with PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD41 (Clone MWReg30, 12-0411-83, eBioscience) and Dylight-650-conjugated anti-mouse Ly6G, with DAPI used to assess viability.

The expression of markers on neutrophils was evaluated by incubating cells with PE-conjugated anti-CD182 (CXCR2) (Clone SA044G4, 149304, BioLegend), PE-conjugated anti-CD184 (CXCR4) (Clone 149304, 146506, BioLegend), FITC-conjugated anti-CD62L (Clone MEL-14, 104405, BioLegend) and AlexaFluor647-conjugated anti-CD11b (Clone M1/70, 557686, BD Pharmingen). Median fluorescence intensity was calculated for each marker, as well as light-scattering (SSC-A) values on the neutrophil population.

Neutrophil migration in Transwell assays was assessed by incubating cells with allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-human CD45 (555485, Clone HI30, BD Pharmingen) and FITC-conjugated anti-human CD66b (555724, Clone G10F5, BD Pharmingen), with DAPI used to assess viability (D8417, Sigma).

Mouse and human neutrophils were gated on the basis of staining for Ly6G (mouse) and CD45 and CD66b (human), and were counted with a FACS Canto-3L flow cytometer equipped with DIVA software (BD Biosciences).

Data were analyzed with FlowJo (Ashland) software. All experiments were conducted at the CNIC Cellomics Unit. A list of the antibodies used in the study can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Intravital microscopy of the inflamed cremaster muscle microcirculation

IVM of the cremaster muscle microcirculation was performed after intrascrotal injection of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) (0.5 μg, R&D Systems)17 in the morning (ZT 5-9) or evening (ZT 11-15) to induce local neutrophil recruitment, followed immediately by injection of a single i.v. bolus of saline or metoprolol (12.5 mg/kg). Before cremaster muscle preparation, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of an anesthetic cocktail of ketamine (72 mg/kg; Anesketin Dechra, 100 mg/mL) and medetomidine hydrochloride (1 mg/kg; Domitor, 1 mg/mL). Body temperature was controlled throughout the experiment to avoid possible effects due to hypothermia. After microsurgical preparation, fluorescently labeled antibodies (0.5-1.25 μg/mouse) were administered by retro-orbital injection into the venous sinus to label surface molecules on polarized neutrophils (FITC-conjugated anti-CD62L and APC-conjugated anti-Ly6G) and platelets (PE-conjugated anti-CD41).

Fluorescence in cremaster muscle venules (6–10 per mouse) was acquired for 1–2 min between 210 and 300 min after TNFα injection (Cy3/561 nm channel for PE, FITC/488 nm channel for FITC, and Cy5/640 nm channel for APC). For double staining with PE- and FITC-conjugated antibodies, acquisition was facilitated in single (FITC) and quad (PE) filters in order to avoid between-channel bleed-through of fluorescent signals.

The IVM system was built by 3i (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO) on an Axio Examiner Z.1 workstation (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) mounted on a 3-dimensional (3D) motorized stage (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA). This set-up allows precise computer-controlled lateral movement between XY positions and a Z focusing drive for confocal acquisition. The microscope was equipped with a CoolLED pE widefield fluorescence LED light source system (CoolLED Ltd., UK) and a quad pass filter cube with a Semrock Di01-R405/488/561/635 dichroic and a FF01-446/523/600/677 emitter. We used a Plan-Apochromat 40x W NA1.0 ∞ /0 objective (Zeiss). Two-dimensional (2D) images were collected with a CoolSnap HQ2 camera (6.45 × 6.45 μm pixels, 1392 × 1040-pixel format; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Image acquisition was coordinated and offline data analysis facilitated with SlideBook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations), run on a Dell Precision T7500 computer (Dell Inc., Round Rock, TX).

Neutrophil tracking and neutrophil–platelet interactions in cremaster venules

The kinetic properties of crawling neutrophils were studied by 2D IVM. Kinetic parameters of interest were velocity, accumulated and Euclidean distance, and directionality. Euclidean distance is defined as the straight-line distance between initial and finishing points of neutrophil movement, whereas accumulated distance is the total length of the path followed.

Polarized neutrophils were identified and tracked from clearly polarized morphology and L-selectin staining. The cell adhesion molecule L-selectin (CD62L) is expressed in a protruding microdomain at the rear of polarized leukocytes (the uropod) that is essential for signal integration. The CD62L-negative pole is generally known as the leading edge. The neutrophil uropod was thus defined as the CD62L-positive domain and the leading edge as the CD62L-negative pole forming multiple protrusions and showing guided movement (Ly6G + ). Around 4-10 venules per mouse were recorded, and time-lapse videos of crawling neutrophils were analyzed with the Manual Tracking and Chemotaxis and Migration Tool plugins in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). For each video, channel intensities were first adjusted and then converted to RGB format. Videos were rotated so that the vessels were positioned horizontally and the blood flow oriented left-to-right. Both plugins were set up with XY calibration values, which depend on the camera and microscope parameters, to convert pixels into linear measures, as well as the time interval between video frames (3 s). Each polarized neutrophil was tracked manually 21 times (1 min) using the Manual Tracking Plugin, which generated a dataset with the respective XY track coordinates. We then used the Chemotaxis and Migration Tool to plot tracks and to obtain the following neutrophil kinetic parameters: velocity (μm/s), accumulated distance (μm), Euclidean distance (μm), and directionality.

Platelets in the inflamed cremaster vessels were visualized as CD41-labeled cells and quantified as described elsewhere17. Between 4 and 10 venules were recorded per mouse, and platelet interactions with neutrophils at the uropod and leading edge (CD62L-positive and -negative, respectively) were calculated as percentages of the total interactions.

In-silico modeling of human ADRB1 and comparative ligand docking

For in-silico modeling of the human ADRB1 protein (including the Arg>Gly variant at position number 389), a fasta sequence (Uniprot ID: P08588) was submitted to the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR)-I-TASSER server. As final templates, we selected the best models corresponding to the largest cluster (human 2580 decoys, mouse 3245 decoys, from more than 20000 in both cases) with minimal energy and correct topology (7 transmembrane segments and the best structural alignment with the β2AR structure (pdb ID 3sn6 as homology template). To minimize the global energy and resolve clashes, these models were refined with the mp relax tool in the Rosetta script interface of Rosetta software suite v3.10 (www.rosettacommons.org). This tool recomputes the side-chain coordinates of the protein residues to take account of membrane environment, lipophilicity, the trans-membrane segment, and protein composition. For each original model, 100 independent refined models were calculated. As before, the models with lower energy and correct folding were selected as final models. To better show the protein position and orientation in the membrane, the refined models were submitted to the PPM server (http://opm.phar.umich.edu/). This server uses a large structural database (membranome) and specialized computational methods to predict and position membrane proteins from 3D structures. These methods take account of long-range electrostatic interactions, first-shell solvation energy (van der Waals, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond interactions), the gradual polarity changes along the bilayer normal, the preferential solvation of protein groups by water, and the hydrophobic mismatch for transmembrane proteins.

We then used the Concavity tool in the Rosetta script to detect cavities and pockets in the models as potential ligand binding sites. The complex formed by the final refined models with metoprolol, and including membrane positioning, was modeled using the ligand-docking tool in the Rosetta script. Briefly, a representative conformer of the ligand was located close to the ligand pocket in the receptor. The protocol computes combinations of atomic coordinates for ligand conformers and the side-chain rotamer rearrangements of the residues in the receptor pocket in order to explore the conformational space and identify ligand-protein interactions. Finally, a new relax cycle was run. As before, the models were submitted to the PPM server to better show the protein position and orientation in the membrane, and the pockets were analyzed with the Concavity tool. In all cases, at least 1000 models were computed. The selected models were those with correct interface topology (ligand inside the pocket without clashes between ligand and protein) and the best energy of interface (minor ΔG, more stability, and protein–ligand interactions such as electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrophilic, van der Waals, hydrogen bonds, and salt bridges).

MD simulations of human ADRB1

MD simulations were run for in-silico models of human Arg389 and Gly389 ADRB1 with and without metoprolol modeled before using a local implementation of GROMACS (version 2024.1)60,61,62. Briefly, in each case (plus ligand), the initial system (model, membrane, ions and water) was created using the CHARMM-GUI web server63 (see Supplementary Tables 5–7).

In every case, KCl concentrations of 0.15 M and a Temperature of 310.15 K were fixed and the asymmetric mammalian plasma membrane:

From the initial input, each MD simulation was run in GROMACS with an initial minimization NPT (Number of molecules, pression 1 atm and temperature 310.15 K constant) of 5000 ps, following by 6 step of equilibration NVPT (1,25,000 ps) and 10 step of production NVPT of 500,000 ps each one, and concatenated to obtain a final MD production of 500 ns (sampled ratio 0.002, ratio of compression 1/10). For each case, 3 replicates were made. To extract and analyze the trajectories, the GROMACS CLI and MD Analysis64,65 (version 2.9.0) tool were used.

Expression and purification of ADRB1 for SPR studies

Two different regular plasmid gene expression vectors were designed and then produced by VectorBuilder, each one encoding one of the hADRB1 variants of the rs1801253 SNP (NM_000684.3: 1165 G > C; p. Gly389Arg). To track the recombinant protein expression, both human ADRB1 and EGFP genes were controlled under the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) early enhancer/promoter and separated using a P2A linker. A Twin-Strep-tag (2 tandem Strep-tag II linked with 3xGGGS) was incorporated at the C-terminal end, followed by a His tag. After bacterial transformation, plasmid DNA was isolated and purified using a Maxi kit (ThermoFisher, #12748412). HEK293T cells were then transfected using 15 µL Lipofectamine LTX Reagent (ThermoFisher, #11668019). 24 h after, cells were dissociated, washed with PBS 1X, pelleted down and stored at −80 °C. Recombinant protein expression in HEK293T cells was confirmed by epifluorescence

When required, the pellet was thawed and resuspended in 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, 10 mM EDTA supplemented with one cOmpleteTM protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (pH 7.4) (Roche, #11836170001). All subsequent procedures were carried out at 4 °C. The suspension was homogenized by sonication for 30 s, incubated with Universal Nuclease (ThermoFisher, #88700) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and centrifuged at 23,755 × g for 25 min. The pellet containing the membrane fraction was then suspended in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES-NaOH and 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 7.4) and homogenized by sonication for 30 s. After one last centrifugation at 23,755 × g for 1 h, the pellet was resuspended in SPR running buffer [10 mM sodium phosphate, 135 mM NaCl, 0.15% dodecyl maltoside (ThermoFisher, #329370050) (pH 7.4)] and homogenized for 30 s. Protein concentration was estimated against the standard bovine serum albumin using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay (ThermoFisher, #23225), and then frozen at −80 °C. Protein concentration was 9.37 and 9.89 mg/ml for G389 and R389 hADRB1, respectively.

Immmunoblotting

Isolated and quantified proteins from HEK293T cells were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System, Bio-Rad), and probed with an antibody anti-ADRB1 (Abcam, ab85037). After washes and incubation with the appropriate secondary antibody, the bound antibody was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ImageQuant LAS 4000 series, GE Healthcare Life Sciences), and blots were analyzed with ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

SPR experimental details

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) binding studies were conducted at 25 °C using a Biacore X100 with Streptavidin sensor chips equilibrated in running buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, 0.15% dodecyl maltoside, pH 7.4). Aliquots of the affinity-purified TwinStrep-His10-tagged G389 or R389 ADRB1 were extensively dialyzed against the running buffer, diluted 10x (to a final concentration of 200 µg/mL) in the running buffer, and injected at 5 µL/min to achieve capture levels of ~4500–5000 resonance units (RU). The captured surfaces were washed with the running buffer for at least 1 h and allowed to stabilize overnight. Prior to the experiment, hADRB1 was detected around 70 kDa in dialyzed samples by immunoblot.

The effect of metoprolol binding to the receptor surfaces was assessed in three independent experiments using a single-cycle kinetic design that involved five consecutive injections of 62.5, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 nM metoprolol at 30 µL/min. All biosensor data processing and analysis were performed using BiaEvaluation (Cytiva), with all responses being double-referenced. For kinetic analyses, data were globally fit to a 1:1 interaction model that included a term for mass transport to obtain binding parameters.

Statistics

Data in graphs are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed with Prism software 10.2.3 (Graphpad, Inc.) and IBM SPSS Statistics software (v23.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York). Normality tests (Shapiro-Wilk test) were used to determine if variables followed a normal distribution. In tables showing clinical data, qualitative patient variables are represented as N (%), and quantitative patient variables are represented as median and interquartile range (IQR: Q1, Q3).

To assess the impact of circadian variations on the effect of metoprolol, the study population was segmented into 4 6-h timeframes: period 1 (P1, from midnight to 6 am), P2 (from 6 am to noon), P3 (from noon to 6 pm), and P4 (from 6 pm to midnight). The statistical analysis was performed according to the per-protocol principle. A chi-square goodness of fit test was used to evaluate differences in MI incidence between the 4 6-h timeframes. A two-tailed chi-square independence test was used to evaluate differences between categorical clinical variables. Linear regression models were used to evaluate the association between patient genotype and the time-of-day of MI onset and the outcome after adjusting for the following cofounders: sex, age ( > 60 years-old), diabetes mellitus, ischemia duration, and pre-PCI TIMI flow grade ( ≤ 1 vs TIMI > 1). In the analysis restricted to patients with a fully occluded artery on angiography (pre-PCI TIMI 0-1), linear regression models were employed after adjusting for sex, age, diabetes mellitus and ischemia duration. Patients with a missing MRI parameter were included. Patients who did not undergo the long-term follow-up MRI for different causes were excluded from the 6-months analysis (n = 5; 2 control and 3 metoprolol in the genotyped-subgroup of patients; n = 18; 12 control and 6 metoprolol in the full cohort).

Results combining genotype and time-of-day of MI onset were analyzed in the full cohort and comparisons between the treatments were done by 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney for non-normally distributed data, and by the Student’s t-test for variables with a normal distribution. Comparisons between cell culture conditions (transwell assays) were done by repeated measures 1-way ANOVA with Friedman post-hoc multiple comparison test for paired samples.

For animal studies assessing the protective action of metoprolol against myocardial IRI and neutrophil migration, sample size was calculated by power analysis using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7). Based on previous data, sample size for the myocardial IRI and peritonitis models was calculated as follows keeping in mind the effect size (40% and 60% of reduction, respectively), standard deviation (30% and 50%, respectively), type 1 error (5%, P = 0.05), power (80%), direction of the effect (two-tailed) and statistical tests (student t-test). Sample size calculated by power analysis was around 10 and 12 animals/group in each model. Experiments were analyzed by blinded operators, and results from mouse models were presented from at least two independent experiments. Comparisons between 2 treatments (vehicle vs. metoprolol) were by 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney for non-normally distributed data and by the Student t-test for variables with a normal distribution. Time-of-day differences in neutrophil marker expression and between genotypes were done by 2-way ANOVA with Šidák’s post-hoc multiple comparison test. Differences were deemed statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Individual-level data from the clinical trial are subject to controlled access due to patient privacy and ethical restrictions. De-identified data will be made available upon reasonable request for proposals of clear scientific merit and feasibility. Requests should be directed to the corresponding author. Each request will be reviewed by the study investigators and the corresponding ethics committee, with a response provided within 4 weeks. Access will be granted under a data use agreement stipulating that the data are used solely for the approved scientific purpose and that no attempts will be made to re-identify participants. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Mega, J. L. et al. Reduced-function CYP2C19 genotype and risk of adverse clinical outcomes among patients treated with clopidogrel predominantly for PCI: a meta-analysis. JAMA 304, 1821–1830 (2010).

Duarte, J. D. & Cavallari, L. H. Pharmacogenetics to guide cardiovascular drug therapy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18, 649–665 (2021).

Johnson, J. A. & Liggett, S. B. Cardiovascular pharmacogenomics of adrenergic receptor signaling: clinical implications and future directions. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 89, 366–378 (2011).

Mialet Perez, J. et al. Beta 1-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms confer differential function and predisposition to heart failure. Nat. Med. 9, 1300–1305 (2003).

Liu, W. N. et al. beta1 adrenergic receptor polymorphisms and heart failure: a meta-analysis on susceptibility, response to beta-blocker therapy and prognosis. PLoS One 7, e37659 (2012).

Johnson, J. A. et al. Beta 1-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms and antihypertensive response to metoprolol. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 74, 44–52 (2003).

Pereira, S. B. et al. beta-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms in susceptibility, response to treatment and prognosis in heart failure: implication of ethnicity. Mol. Med. Rep. 7, 259–265 (2013).

Parikh, K. S. et al. Dose response of beta-blockers in adrenergic receptor polymorphism genotypes. Circ. Genom. Precis Med. 11, e002210 (2018).

Smolensky, M. H., Hermida, R. C. & Geng, Y. J. Chronotherapy of cardiac and vascular disease: timing medications to circadian rhythms to optimize treatment effects and outcomes. Curr. Opin. Pharm. 57, 41–48 (2021).

Muller, J. E. et al. Circadian variation in the frequency of onset of acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 313, 1315–1322 (1985).

Suarez-Barrientos, A. et al. Circadian variations of infarct size in acute myocardial infarction. Heart 97, 970–976 (2011).

Schloss, M. J. et al. S. The time-of-day of myocardial infarction onset affects healing through oscillations in cardiac neutrophil recruitment. EMBO Mol. Med. 8, 937–948 (2016).

Aroca-Crevillen, A., Adrover, J. M. & Hidalgo, A. Circadian features of neutrophil biology. Front Immunol. 11, 576 (2020).

Ibanez, B., Heusch, G., Ovize, M. & Van de Werf, F. Evolving therapies for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65, 1454–1471 (2015).

Heusch, G. et al. Cardiovascular remodelling in coronary artery disease and heart failure. Lancet 383, 1933–1943 (2014).

Vinten-Johansen, J. Involvement of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of lethal myocardial reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 61, 481–497 (2004).