Abstract

This paper presents boundary-layer profiles of streamwise mean and streamwise/wall-normal fluctuation data (\(\overline{u},{u}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}}^{{\prime} },{v}_{{{\rm{RMS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\)) recorded with Krypton Tagging Velocimetry (KTV) at 100 kHz in a hypersonic, turbulent, zero-pressure-gradient boundary layer. The edge Mach number, wall-to-recovery temperature ratio, and friction Reynolds number are (M∞ = 6.4, Tw/Tr = 0.54, Reτ = 450), and (M∞ = 6.0, Tw/Tr = 0.17, Reτ = 780), for the ‘cold-flow’ and ‘enthalpy-matched’ conditions, respectively. The KTV data agrees with direct numerical simulation (DNS) within the error bounds of the experiment down to as low as 10% of the boundary-layer thickness (y/δ ≈ 0.1). The KTV and DNS data agree with incompressible laser-doppler anemometry (LDA) data after applying the Morkovin scaling, which accounts for mean density differences across the boundary layer. Therefore, the experimental data presented are supportive of Morkovin’s hypothesis, which is fundamental to our understanding of supersonic and hypersonic compressible turbulence. These are the first such wall-normal fluctuation measurements to support the hypothesis first proposed in 1962.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aerodynamic drag and heat transfer must be accurately predicted to design a high-speed vehicle; to do so requires a physical understanding of supersonic and hypersonic turbulence1. Morkovin’s hypothesis2 is foundational to our understanding of these flows, and it states that “we can expect with confidence that the essential dynamics of these supersonic shear flows will follow the incompressible pattern.” An outcome of this hypothesis is that the profiles of mean velocity and Reynolds stresses may be transformed from the compressible form to a similar incompressible form by simply accounting for mean density variations across the boundary layer3. That is, “similarity is achieved if the local velocity scale in the constant stress region is now \({u}_{\tau }\sqrt{{\rho }_{w}/\rho }\) [for the compressible case] instead of uτ [for the incompressible case]”4. Here, \({u}_{\tau }=\sqrt{{\tau }_{w}/{\rho }_{w}}\), τw is the shear stress at the wall, and ρw is the density at the wall. An open question is: At what Mach number is Morkovin’s hypothesis still valid? Smits and Dussauge4 suggest that this hypothesis may be used with confidence in boundary layers up to a Mach number of ~5. Above Mach 5, pressure and density fluctuations become more intense. They may become locally supersonic, leading to shocklets about the turbulent eddies. These intense disturbances could appreciably alter the energy exchange mechanisms in the flow, making the difference between the incompressible and compressible cases substantive and nullifying Morkovin’s hypothesis.

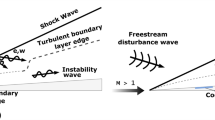

Morkovin2 suggests “careful coupled fluctuation and mean-flow measurements in supersonic turbulent boundary layers with heat transfer and/or roughness” to test “the idea of the Mach independence of the basic mechanisms” of turbulence. To this end, researchers have spent six decades seeking to assess the hypothesis by performing conventional experiments, the current standard of which is particle-image velocimetry (PIV), and sampling computational results performed with direct numerical simulation (DNS), noting that DNS solves the Navier–Stokes equations without making simplifying assumptions about turbulence. That is, if Morkovin’s hypothesis is correct, the streamwise and wall-normal fluctuation data recorded in a zero-pressure gradient (ZPG) compressible boundary layer from PIV and DNS literature should, more or less, match incompressible boundary layer data when normalized by \({u}_{\tau }\sqrt{{\rho }_{w}/\rho }\). In Fig. 1, data representative of the DNS literature5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 from Zhang et al.10 and PIV literature13,14,15,16,17 from Williams et al.17 are compared to classical incompressible data from DeGraaff and Eaton18 taken with laser-doppler anemometry (LDA). The compressible DNS and the incompressible LDA fluctuation data have the same qualitative variation when normalized by \({u}_{\tau }\sqrt{{\rho }_{w}/\rho }\), although the peak fluctuation may be different close to the wall. Moreover, the compressible PIV data are within striking distance of DNS and the incompressible LDA data for the streamwise fluctuations. However, for the wall-normal fluctuations, there is clear disagreement between the transformed compressible PIV data when compared to the incompressible LDA data and transformed compressible DNS. This yields an outstanding question: Are the compressible simulation data flawed and/or Morkovin’s hypothesis invalid, or are the PIV data flawed? This is the question that this letter addresses.

Since Morkovin himself analyzed the Kistler19 findings from 1958, experimentalists have attempted to test Morkovin’s hypothesis with velocimetry techniques based on Pitot-probe measurement, hot-wire anemometry (HWA), and particle-based techniques, such as laser-Doppler velocimetry and particle image velocimetry20. Pitot-probe measurement and HWA are well-established and work well in low-speed flows; but, these methods are intrusive and suffer from issues related to frequency response, spatial resolution, and assumptions on local temperature. PIV represents the current state-of-the-art (SOA); however, because the flow may slip about a particle due to rarefaction and inertial effects, it may not faithfully trace the flow at all relevant scales21,22,23,24. This is a fundamental limitation which may not be overcome and has manifested itself most clearly in the wall-normal velocity fluctuations data (\({v}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\) in Fig. 1). Furthermore, an authoritative review of the literature in Williams et al.17 states that, for the existing data at hypersonic Mach number, “the scatter is such that little can be said of Morkovin’s hypothesis with any degree of confidence, with much of the experimental data below the incompressible profiles and DNS simulations." An alternative method, called Tagging Velocimetry (TV), addresses this problem whereby a gas that is native, seeded, or synthesized in the flow is tagged and the resulting pattern is imaged to track velocity25,26. This is the driving force behind why many researchers have intensively studied tracer species for TV in high-speed flows that include oxygen27, biacetyl28, acetone29,30,31,32,33,34, hydroxyl35,36,37,38, iodine39,40, nitric oxide41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51, nitrogen52,53,54,55,56, and argon57 as well as many others58,59,60,61.

For this work, Krypton Tagging Velocimetry (KTV)62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70 is chosen as the TV tracer. This is because Kr is non-toxic and inert, making it safe and nonreacting in a broad class of applications, including high-enthalpy flows. The transport and photophysical properties of Kr are well documented with energy levels accessible with current laser and camera systems; this has enabled the recording of high signal-to-noise-ratio KTV data near the wall in high-speed, turbulent boundary layers.

In the paper, we present boundary-layer profiles of streamwise mean and streamwise/wall-normal fluctuation data (\(\overline{u},{u}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}}^{{\prime} },{v}_{{{\rm{RMS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\)) recorded with KTV at 100 kHz in a Mach 6 ZPG boundary layer at cold-flow and enthalpy-matched conditions; these data support Morkovin’s hypothesis2.

Results

Experimental setup

Experiments were performed in the Stevens Shock Tunnel, which is a reflected-shock tunnel designed to duplicate Mach 6 flight, with matching enthalpy, Mach, and Reynolds number at 20 km34,71,72. The nozzle exit diameter is 16 in (406 mm) and the test rhombus is ~13 in (330 mm) high by 5 ft (1.5 m) long. The Mach 6 ‘enthalpy-matched’ condition has a test time of 5 ms at unit Reynolds number up to 8 × 106 1/m (a 3 × 106 1/m condition is used for this work) and is executed with a He driver. For the “cold-flow” condition, a N2 driver was used, providing a longer 15 ms test time and an increased Reynolds number of up to 32 × 106 1/m (a 14 × 106 1/m condition is used for this work). This reduces the reservoir enthalpy but provides sufficient heating such that the flow in the freestream does not condense. For this campaign, the test gas was 95%N2/5%Kr. Doping the flow with 5% Kr slightly alters the transport properties and freestream conditions which are calculated with Cantera73 and the Shock and Detonation Toolbox74 following the methods in Korte et al.75 and Segall et al.34. For reference, seeding the N2 test gas with 5% Kr changes the ratio of specific heats from 1.400 to 1.407 or ≈0.5%. The conditions and those for some in the relevant literature are presented in Table 1. Five shock tunnel runs were executed for both the streamwise and wall-normal tests for the cold flow condition. Each run yields ≈70 realizations for a total of ≈350 realizations per data set. Three shock tunnel runs were executed for the streamwise and five for the wall-normal tests for the enthalpy-matched condition. All tunnel run data is available as Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

The test article is a hollow-cylinder flare (HCF) that fits within the inviscid test rhombus. The HCF is 1 m-long with a 0.102 m (4 in) outer diameter hollow cylinder and a 34∘ flare of maximum diameter 0.203 m (8 in). Three 40-grit sanding belt trips were placed on the test article to induce turbulence with distributed roughness: (1) 0.076 m (3 in) long at 0.026 m (1 in) from the sharp leading edge; (2) 0.076 m (3 in) long at 0.137 m (5.375 in); and (3) 0.222 m (8.75 in) long at 0.267 m (10.5 in). The tagging location is 0.84 m (32.9 in) downstream of the HCF leading edge. This is Rex = 11.5 × 106 and Rex = 2.4 × 106 for the cold-flow and enthalpy-matched conditions, respectively, and at least 45δ downstream of the end of the trip. The boundary layer is assumed to be in an equilibrium, turbulent state as supported by focused laser differential interferometry (FLDI) measurements reported in section “Results” and Chen et al.76. The FLDI measurements were made upstream of the KTV measurements at 0.7 m (27.6 in) or Rex = 9.8 × 106 and Rex = 2.0 × 106 from the HCF leading edge for the cold-flow and enthalpy-matched conditions, respectively. Those results match those of DNS, bringing confidence to the understanding of the state of the boundary layer.

Following Mustafa et al.68 and Shekhtman et al.77, KTV is performed by issuing a laser beam into the flow to excite the Kr along a line. “Write” and “read” exposures of laser-induced fluorescence from the excited and recombining Kr/Kr+ are recorded at a prescribed delay. The relevant transitions are marked in purple and red in the energy level diagram in Fig. 2, as this KTV write/read procedure may differ slightly from work in the literature. The “write step" is performed by exciting Kr atoms to form the tagged tracer through a (2+1) resonance-enhanced, multiphoton ionization (REMPI) process. First, two-photon excitation occurs via 4p6 (1S0) → 5p[1/2]0 (two 212.6 nm photons, transition A) with subsequent one-photon ionization (one 212.6 nm photon, transition B). Fluorescence for the write step is recorded primarily from the decay to the resonance state \(5p{[1/2]}_{0}\to 5s{[3/2]}_{1}^{\,{{\rm{o}}}\,}\) (758.9 nm, transition C). After a prescribed delay, the “read step” is performed. The displacement of the tagged Kr is imaged from transitions E-I resulting from the recombination process J. The streamwise measurements made use of a CW 769.5 nm tunable laser diode to boost the signal with re-excitation of the metastable state discussed in ref.70,77 (transition D in Fig. 2). This boosts the signal by up to ≈50% and was not used for the wall-normal experiments.

The 100 kHz, 212.6 nm laser pulses for (2+1) REMPI were generated using an externally triggered Spectral Energies QuasiModo 1200 Burst-Mode Laser (Fig. 3-top). The fundamental Nd:YAG output near 1064.5 nm was frequency tripled to produce 354.8 nm pulses. A beam splitter was used to direct 66% of the power to pump an optical-parametric oscillator (OPO) described in Grib et al.78. The OPO output 530.1 nm pulses, which were then sum-frequency mixed with the residual (33%) 354.8 nm pulses to form the 212.6 nm.

For the streamwise measurements, the 212.6 nm beam was directed into the test section such that it traversed the spanwise direction and was focused at a point tangent to the HCF just upstream of the flare with a 300 mm lens (Fig. 3-top). This was done following Segall et al.34 to reduce the laser-induced ablation plume and increase wall resolution using a coordinate transformation. The imaging system for the streamwise measurements was a Carl Zeiss 85 mm Lens, a 28 mm lens tube, a Video Scope VS4-1845HS image intensifier (50 ns gate), and a Phantom 2512 high-speed camera (10 pixel/mm resolution). The prescribed write/read delay was 2 μs. Sample write/read exposures are shown in Fig. 3 (bottom).

To measure wall-normal fluctuations, a novel approach was implemented as shown in Fig. 4 (top). Juxtaposed to the streamwise setup, the 212.6 nm beam entered a window on the side of the facility, traversing the spanwise direction to a mirror just behind the flare on the HCF. Then, the beam is turned at nearly a right angle and directed upstream at a shallow angle (θF = 14∘ in Fig. 4) to the freestream to strike the top of the HCF. This tagged line captures wall-normal fluctuation information. The angle had to be shallow to reduce streamwise fluctuation contamination of the wall-normal data and to capture the entire boundary layer and a significant portion of the freestream (y/δ ≈ 1.6); these requirements will be discussed in section “Results”. This relatively long traversal length required the use of a 750 mm lens to provide a long Rayleigh length. Because the gas is moving in nearly the opposite direction of the 212.6 nm beam, the absorption wavelength of the Kr will change substantially. Following Demtröder79, this is calculated as \({\lambda }_{s}={\lambda }_{0}/[\left(1-(U/c)\right.\cos ({\theta }_{{{{\rm{F}}}}})]\), where λs, λ0 and c and are the Doppler-shifted wavelength, the un-Doppler-shifted wavelength, and the speed of light, respectively. In practice, this was done by blue-shifting the idler of the OPO by ≈20 pm, which was monitored by a wavemeter. The wall-normal fluctuation imaging system was a Carl Zeiss 85 mm Lens, an 8 mm lens tube, a Video Scope VS4-1845HS image intensifier (200 ns gate), and a TMX 7510 high-speed camera (12 pixel/mm resolution). The prescribed write/read delay was 2 μs. Sample write/read exposures are shown in Fig. 4 (bottom).

Data reduction and uncertainty estimate

The write/read image pairs are processed in a similar way as Segall et al.34 to yield dimensional velocity profiles. The translated fluorescing lines are captured with the intensified camera, and Gaussian fits are made to find their location.

The streamwise data processing procedure is as follows:

-

(1)

Binning by six pixels vertically (collapsing in the wall-normal direction).

-

(2)

Cropping to the desired region.

-

(3)

Smoothing by 3 pixels per row.

-

(4)

Normalizing the image intensity.

-

(5)

Using the peak-finding algorithm of O’Haver80 to fit a Gaussian to the peak intensity value of each row. The displacement from the write line to the read line, Δx, over the prescribed delay, Δt, resulted in the velocity profile for each frame, u = Δx/Δt. For reference, see the sample exposures in Fig. 3 (bottom).

Following Segall et al.81, uncertainty in the streamwise KTV measurements was estimated as

where uncertainty estimates of a variable are indicated with a tilde. The uncertainty in the measured displacement distance, \(\widetilde{\Delta x}\), of the tracer is estimated as 10 μm, which is the 95% confidence interval of peak location for the Gaussian fit. The uncertainty in time, \(\widetilde{\Delta t}\), is estimated to be half the intensifier gate width (25 ns), which causes fluorescence blurring as considered in Bathel et al.43. The third term in Eq. (1) is uncertainty in streamwise velocity due to wall-normal flow in the xy-plane82. The wall-normal fluctuation uncertainty used in Eq. (1) is conservatively estimated to be \(\widetilde{{v}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }}={u}_{\tau }\sqrt{{\rho }_{w}/\rho }\), which is ≈2–5% of the velocity at the boundary-layer edge.

A novel processing algorithm was used to quantify the wall-normal fluctuations, \({v}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\). These fluctuations may be found through the Reynolds decomposition, \(v=\overline{v}+v{\prime}\); that is, the mean will be used as a reference to find the fluctuating quantity. The process is as follows:

-

(1)

Referring to Fig. 5-top, in physical space (Xcyl, Ycyl), fit a straight line (XF, YF) to the read-line data (XR, YR) outside the boundary layer at y/δ = 1.0−1.6 and extend that line to the model surface (green line in Fig. 5-top). The fitted line will have angle θF.

Fig. 5: Approach for wall-normal velocity fluctuation measurement. Top Left: Sketch of write line in purple, translated read line in red, and fit to read line above boundary layer in blue, y/δ = 1.0−1.6 ΔY1. Bottom Left: Sketch of read deviation from freestream fit in blue, and mean read deviation from freestream fit in gold. Top right: Visualization of ΔY1 and \(\overline{\Delta {Y}_{1}}\) of bottom left for all realizations in one shock tunnel run. Bottom Right: Visualization of ΔY2 and ΔY2RMS for all realizations in one shock tunnel run.

-

(2)

Find the difference in the wall-normal direction between the read data and the freestream fitted line to form ΔY1 = YR − YF.

-

(3)

Recast the data in (Ycyl, ΔY1) space as shown in Fig. 5-bottom.

-

(4)

Find the mean of ΔY1 for to form \(\overline{\Delta {Y}_{1}}\) shown in Fig. 5 (top-right).

-

(5)

Subtract \(\overline{\Delta {Y}_{1}}\) from ΔY1 to form \(\Delta {Y}_{2}=\Delta {Y}_{1}-\overline{\Delta {Y}_{1}}\), as shown in Fig 5 (bottom-right).

-

(6)

Find the RMS of ΔY2 to form ΔY2-RMS, shown in black in Fig. 5 and divide by the interframe delay to form \({v}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}}^{{\prime} }=\Delta {Y}_{2{{\rm{-RMS}}}}/\Delta t\).

Exposures for the wall-normal fluctuations were processed nearly identically to the streamwise data. The images were rotated such that the line was forced to be nearly vertical to help the Gaussian peak-finding algorithm, and the images were unwarped. Because the fluorescing line extends the entire length of the camera lens, from bottom left to top right, image warping became appreciable. To rectify this, images were unwarped before analysis using the imwarp MATLAB command and prescribing a displacement. The displacement was quantified by:

-

(1)

Capturing a write line to be used as a reference (with no flow).

-

(2)

Rotating the reference line such that it is vertical.

-

(3)

Performing the binning, truncation, and peakfit to the reference line as done in the streamwise data.

-

(4)

Performing a linear fit to the reference line.

-

(5)

Record the displacements in x between the reference line and linearly-fitted line for every y.

A sanity check on this unwarping procedure was to plot the reference write line, which can be assumed to be straight, before and after applying imwarp in MATLAB. Because of the differential nature of the technique, this unwarping procedure was probably not necessary but for the presentation of ΔY1 and \(\overline{\Delta {Y}_{1}}\) in Fig. 5 (top-right). That is, the results in ΔY2 in Fig. 5 (bottom-right) do not change appreciably relative to the error in the measurement with or without the unwarping procedure.

Uncertainty in the wall-normal KTV measurements is estimated in the usual way as

where the first two terms consider precision error and the final term considers bias error. The uncertainty in ΔY2-RMS is estimated as 10 μm (from Gaussian fitting). The uncertainty in time, \(\widetilde{\Delta t}\), is estimated to be 100 ns (half the intensifier gate width).

The last term, \({v}_{\,{{\rm{RMS-Bias}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\), accounts for the uncertainty due to the potential in-plane contamination from \(\overline{u}\), \(u{\prime}\), and \(\overline{v}\). Two strategies were used to assess the in-plane contamination. The first approach is to analyze the magnitude of the measured wall-normal velocity fluctuation as

where the wall-normal velocity fluctuation from Zhang et al.10 DNS is \({v}_{\,{{\rm{DNS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\) and the uncertainty in the wall-normal fluctuation due to the streamwise fluctuation, by geometry, is \(\delta {v}_{u{\prime} }^{{\prime} }={u}_{\,{{\rm{DNS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\tan {\theta }_{F}\). The second approach is to create and analyze pseudo data via a Monte Carlo (MC) simulation of the kinematics of the write/read line as

The velocity vectors in Eqs. (4) are created from Zhang et al.10, assuming 300 normally distributed random samples for the fluctuations. The pseudo data was processed identically to the experimental data.

Processing the Monte Carlo (MC) pseudo data in the same way as the experimental data results in a nearly identical \({v}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\) as that from the analytical prediction in Eq. (3), bringing confidence to both (Fig. 6 (left)). Additionally, in Fig. 6 (left), we evaluate the response of the measurement technique to turning on/off different components of velocity. Including all components, \((\overline{u},u{\prime},\overline{v},v{\prime} )\), most closely mimics the present experiment and was used to evaluate the bias error in Eq. (2), as there is a slight bias error high (plotted in red). Because of the differencing step in the measurement technique, there is no error in \({v}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\) from \((\overline{u},\overline{v})\) (plotted in blue). The primary form of bias error is then from the \((u{\prime} )\) (purple). Finally, a sanity check including only \((\overline{v},v{\prime} )\) matches the prescribed DNS data nearly identically (plotted in green).

Left: Response of the measurement technique to turning on/off different velocity components to assess their effect on \({v}_{\,{{\rm{RMS-Bias}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\). Data labeled with a component includes only those components; e.g., data labeled with \(\overline{u},u{\prime}\) includes only those two components. Right: Response of the measurement technique to variable incident angle θF.

Figure 6 (right) shows that the bias error of the technique is highly dependent on the incident angle, θF. The bias error is low outside the boundary layer and increases closer to the wall due to the onset of streamwise velocity fluctuation contamination in wall-normal measurements. This is apparent in the bias error increasing in Fig. 6 (left) nearer to the wall. The data appear to nearly collapse at θF = 5∘. Ultimately, for the current experimental setup with θF = 14∘, the maximum bias error in \({v}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\) is at most ≈8% high at y/δ ≈ 0.1. We assert this bias error is acceptable, given the dearth of data for this flowfield, and report error bars in the final results per Eqs. (2) and (3).

Focused laser differential interferometry (FLDI) measurement of turbulent, boundary-layer spectra

FLDI data were recorded to support the assumption that the KTV data were recorded in an equilibrium, turbulent boundary layer. Developed by Smeets83,84,85,86,87,88 and Smeets and George89 in the 1970s, FLDI is a common path, polarizing interferometer sensitive to the phase difference between the interfering beam pairs. It features excellent spatial and temporal resolution (<100 μm and 10 MHz), as well as high sensitivity at low densities (0.1 g/m3)90. Parziale et al.91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98 advanced the FLDI technique and used it to characterize the facility-disturbance-level and boundary-layer instability/turbulence in a reflected-shock tunnel.

The FLDI beams used to interrogate the boundary layer generated over the model were positioned ~700 mm from the model’s leading edge and 6.5 mm above the surface of the hollow cylinder (see locations in Figs. 3 (top) and 4 (top)). Two FLDI probe volumes were interspaced by 1.1 mm in the streamwise direction. The intraspacing between the FLDI beam pairs was 700 μm.

Turbulent boundary-layer spectra of density fluctuations from the cold-flow and enthalpy-matched FLDI experiments are compared to the DNS results from Chen et al.76 in Fig. 7. The abscissa is presented in the inner-scaling normalization of the angular frequency by the kinematic viscosity and friction velocity (\({\omega }_{{{{\rm{norm}}}}}=\omega {\nu }_{w}/{u}_{\tau }^{2}\)) to account for the differences in the run conditions. The cold-flow and enthalpy-matched experiments appear to qualitatively match the representative DNS data. Moreover, the Pearson correlation coefficient is computed between the DNS and cold-flow and the DNS and enthalpy-matched FLDI spectra to be ρCF/DNS = 0.98 and ρEM/DNS = 0.91, respectively. The qualitative (shape) and quantitative (Pearson correlation coefficient) similarity supports the assertion that the FLDI data, and thus the KTV data, is that of a fully developed, equilibrium, turbulent boundary layer. Non-fully-developed, turbulent boundary-layer spectra are readily apparent as they show appreciable deficits in the region marked by ω−5/3. These FLDI data are recorded at xFLDI = 700 mm, which is upstream of the KTV tagging line location xKTV = 840 mm. FLDI data at a single location does not constitute a definitive validation of an equilibrium, turbulent boundary layer; however, the FLDI data and KTV data, in concert, and their consistency with DNS, provide the best possible evidence with the current experimental setup to this end. Further details on the spectra comparison can be found in Chen et al.76.

Density-fluctuation spectra comparison between representative FLDI experiments and DNS results of similar conditions from Chen et al.76. Spectra are presented in inner-scaling normalization of the angular frequency. FLDI spectra, recorded upstream of KTV, indicate an equilibrium turbulent boundary layer.

DNS/KTV comparison in support of Morkovin’s hypothesis

The mean streamwise velocity is then nondimensionalized via the van Driest99 transformation following100,101 with the local mean density profile coming from the generalized Reynolds analogy from Zhang et al.102, as opposed to the simpler Walz103 relation. The skin-friction coefficient is evaluated following Zhao and Fu104, replacing the previous technique of using the Kármán–Schoenherr correlation and the van Driest II99 transformation. The Zhao and Fu104 method is chosen, as the van Driest II method struggles to map the compressible scaling of skin-friction to the incompressible relation for a highly cooled wall, as confirmed by Huang et al.101 and Zhao and Fu104. Nondimensional streamwise velocity from computations (DNS), comparable experiments (PIV), and the present work (KTV) data are presented in Fig. 8. Agreement between the methods is within the estimated uncertainty of the current measurement technique, bringing confidence to the results.

The streamwise (\({u}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\)) and wall-normal (\({v}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\)) fluctuation data are shown in Fig. 9 as normalized by the Morkovin scaling for computations (DNS), comparable experiments (PIV), and the present work (KTV). Additionally, the LDA data from De Graaff, D. B., and Eaton, J. K.18 is shown as a point of comparison for incompressible flow. That is, the fluctuation profiles may be transformed from the compressible form to a similar incompressible form by simply accounting for mean density variations across the boundary layer10. The nondimensional mean and fluctuation profiles were not found to change substantially (<2%) when the mean density variation was evaluated with the Walz103 relation and compared to the generalized Reynolds analogy in Zhang et al.102.

The data are presented in the outer units (against y/δ) where sensitivity to Reynolds number differences between data sets would be most modest; this is because the fluctuations could be expected to collapse with Reynolds number as in incompressible flow. Closer to the wall, the KTV bias error increases, per section “Results”. The DNS, PIV, and KTV streamwise fluctuation data are in reasonable agreement with the incompressible data when appropriately transformed. However, it is apparent that PIV, which is the current SOA measurement technique, cannot capture the wall-normal fluctuations at hypersonic conditions. Williams et al.22 postulate that this discrepancy is because PIV is fundamentally limited by insufficient particle response times due to rarefaction effects, especially near the wall.

In contrast, because of the use of a tagging technique which does not suffer from reduced particle response, both the streamwise and wall-normal KTV fluctuation data in Fig. 9 show good agreement with DNS from Zhang et al.10 performed at two wall-temperature ratios. DNS predicts that the wall-temperature ratio will shift the peak magnitude and location slightly at wall-normal locations below y/δ ≈ 0.1, a feature apparently captured in the \(u{\prime}\) data for the TW/TR = 0.17 case. The fluctuation data plotted in outer units nominally collapse for y/δ ≿ 0.1, as in Duan et al.6. The transformed DNS and KTV data agree with the incompressible data from DeGraaff and Eaton18. These KTV data are the first such measurements of hypersonic wall-normal fluctuations in support of Morkovin’s hypothesis2. There is a slight undulation in the KTV data with a wavelength of y/δ ≈ 0.2. This feature is not believed to be physical and falls well within the error bars of the measurement. KTV also indicates a higher level of noise outside the boundary layer than in the DNS, a topic of future investigation.

Discussion

Profiles of streamwise mean and streamwise/wall-normal fluctuation velocity (\(\overline{u},{u}_{\,{{\rm{RMS}}}}^{{\prime} },{v}_{{{\rm{RMS}}}\,}^{{\prime} }\)) for a hypersonic, turbulent, zero-pressure-gradient boundary layer are presented. These data are recorded with KTV at 100 kHz in the Stevens Shock Tunnel operated at two conditions. The edge Mach number, wall-to-recovery temperature ratio, and friction Reynolds number are (M∞ = 6.4, Tw/Tr = 0.54, Reτ = 450), and (M∞ = 6.0, Tw/Tr = 0.17, Reτ = 780), for the ‘cold-flow’ and ‘enthalpy-matched’ conditions, respectively. KTV and DNS data agree with incompressible LDA data after applying the Morkovin scaling down to as low as 10% of the boundary-layer thickness (y/δ ≈ 0.1). Therefore, the experimental data presented in this letter are supportive of Morkovin’s hypothesis2, which is fundamental to our understanding of supersonic and hypersonic compressible turbulence. These are the first such wall-normal fluctuation measurements to support the hypothesis first proposed in 1962.

There are several avenues for future work. Normalizing the fluctuation data with the inner variables will yield scaling insights as in Fig. 2 of Marusic et al.105. Efforts will be made to extend the tagging technique as close to the wall as possible to investigate true, near-wall compressibility effects as noted in Yu et al.106. Understanding the effects of freestream noise on turbulence quantities will be investigated, as reported for low-speed flows in Dogan et al.107. Finally, higher Reynolds number tests are planned with simultaneous off-body and surface measurements to assess historical and newly proposed skin-friction correlations as in Zhao and Fu104.

Data availability

The van Driest and fluctuation KTV data presented in this paper are included as Source Data. Additional information can be had by contacting the corresponding author. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Leyva, I. A. The relentless pursuit of hypersonic flight. Phys. Today 70, 30–36 (2017).

Morkovin, M. V. Effects of compressibility on turbulent flows. Mécanique de la Turbulence, 367–380 (CNRS Paris, 1962).

So, R. M. C., Gatski, T. B. & Sommer, T. P. Morkovin hypothesis and the modeling of wall-bounded compressible turbulent flows. AIAA J. 36, 1583–1592 (1998).

Smits, A. J. & Dussauge, J. P. Turbulent Shear Layers in Supersonic Flow 2nd edn (Springer, New York, New York, 2006).

Martin, M. P. Direct numerical simulation of hypersonic turbulent boundary layers. Part 1. Initialization and comparison with experiments. J. Fluid Mech. 570, 347–364 (2007).

Duan, L., Beekman, I. & Martin, M. P. Direct numerical simulation of hypersonic turbulent boundary layers. Part 2. Effect of wall temperature. J. Fluid Mech. 655, 419–445 (2010).

Duan, L., Beekman, I. & Martin, M. P. Direct numerical simulation of hypersonic turbulent boundary layers. Part 3. Effect of Mach number. J. Fluid Mech. 672, 245–267 (2011).

Duan, L. & Martin, M. P. Direct numerical simulation of hypersonic turbulent boundary layers. Part 4. Effect of high enthalpy. J. Fluid Mech. 684, 25–59 (2011).

Priebe, S. & Martin, M. P. Low-frequency unsteadiness in shock wave–turbulent boundary layer interaction. J. Fluid Mech. 699, 1–49 (2012).

Zhang, C., Duan, L. & Choudhari, M. M. Direct numerical simulation database for supersonic and hypersonic turbulent boundary layers. AIAA J. 56, 4297–4311 (2018).

Passiatore, D., Sciacovelli, L., Cinnella, P. & Pascazio, G. Finite-rate chemistry effects in turbulent hypersonic boundary layers: a direct numerical simulation study. Phys. Rev. Fluids 6, 054604 (2021).

Cogo, M., Salvadore, F., Picano, F. & Bernardini, M. Direct numerical simulation of supersonic and hypersonic turbulent boundary layers at moderate-high Reynolds numbers and isothermal wall condition. J. Fluid Mech. 945, 30 (2022).

Tichenor, N., Humble, R. & Bowersox, R. Response of a hypersonic turbulent boundary layer to favourable pressure gradients. J. Fluid Mech. 722, 187–213 (2013).

Peltier, S. J., Humble, R. A. & Bowersox, R. D. W. Crosshatch roughness distortions on a hypersonic turbulent boundary layer. Phys. Fluids 28, 045105 (2016).

Neeb, D., Saile, D. & Gülhan, A. Experiments on a smooth wall hypersonic boundary layer at Mach 6. Exp. Fluids 59, 68 (2018).

Lee, J. H., Kevin Monty, J. P. & Hutchins, N. Validating under-resolved turbulence intensities for PIV experiments in canonical wall-bounded turbulence. Exp. Fluids 57, 129 (2016).

Williams, O. J. H., Sahoo, D., Baumgartner, M. L. & Smits, A. J. Experiments on the structure and scaling of hypersonic turbulent boundary layers. J. Fluid Mech. 834, 237–270 (2018).

De Graaff, D. B. & Eaton, J. K. Reynolds-number scaling of the flat-plate turbulent boundary layer. J. Fluid Mech. 422, 319–346 (2000).

Kistler, A. L. Fluctuation measurements in supersonic turbulent boundary layers. Phys. Fluids 2, 290–296 (1959).

Laderman, A. J. & Demetriades, A. Mean and fluctuating flow measurements in the hypersonic boundary layer over a cooled wall. J. Fluid Mech. 63, 121–144 (1974).

Lowe, K. T., Byun, G. & Simpson, R. L. The effect of particle lag on supersonic turbulent boundary layer statistics. In Proc. AIAA SciTech 2014 (AIAA-2014-0233, National Harbor, Maryland, 2014).

Williams, O. J. H., Nguyen, T., Schreyer, A.-M. & Smits, A. J. Particle response analysis for particle image velocimetry in supersonic flows. Phys. Fluids 27, 076101 (2015).

Aultman, M. T., Disotell, K. & Duan, L. The effect of particle lag on statistics of hypersonic turbulent boundary layers subject to pressure gradients. In Proc. AIAA Scitech 2022 (AIAA-2022-1062, San Diego, California and Virtual, 2022).

Brooks, J. M., Gupta, A. K., Smith, M. S. & Marineau, E. C. Particle image velocimetry measurements of Mach 3 turbulent boundary layers at low Reynolds numbers. Exp. Fluids 59, 83 (2018).

Danehy, P. M. et al. Non-intrusive measurement techniques for flow characterization of hypersonic wind tunnels. in Flow Characterization and Modeling of Hypersonic Wind Tunnels (NATO Science and Technology Organization Lecture Series STO-AVT 325) (NF1676L-31725 - Von Karman Institute, Brussels, Belgium, 2018).

Jiang, N., Hsu, P. S., Gragston, M. & Roy, S. Recent progress in high-speed laser diagnostics for hypersonic flows. Appl. Opt. 62, 59–75 (2023).

Clark, A., McCord, W. & Zhang, Z. Air resonance enhanced multiphoton ionization tagging velocimetry. Appl. Opt. 61, 3748–3753 (2022).

Mirzaei, M., Dam, N. J. & Water, W. Molecular tagging velocimetry in turbulence using biacetyl. Phys. Rev. E 86, 1–8 (2012).

Lempert, W. R., Jiang, N., Sethuram, S. & Samimy, M. Molecular tagging velocimetry measurements in supersonic microjets. AIAA J. 40, 1065–1070 (2002).

Lempert, W. R., Boehm, M., Jiang, N., Gimelshein, S. & Levin, D. Comparison of molecular tagging velocimetry data and direct simulation Monte Carlo simulations in supersonic micro jet flows. Exp. Fluids 34, 403–411 (2003).

Handa, T., Mii, K., Sakurai, T., Imamura, K., Mizuta, S. & Ando, Y. Study on supersonic rectangular microjets using molecular tagging velocimetry. Exp. Fluids 55, 1725 (2014).

Gragston, M. & Smith, C. D. 10 kHz molecular tagging velocimetry in a Mach 4 air flow with acetone vapor seeding. Exp. Fluids 63, 1–9 (2022).

Andrade, A., Hoffman, E. N. A., LaLonde, E. J. & Combs, C. S. Velocity measurements in a hypersonic flow using acetone molecular tagging velocimetry. Opt. Express 30, 42199–42213 (2022).

Segall, B. A., Shekhtman, D., Hameed, A., Chen, J. H. & Parziale, N. J. Profiles of streamwise velocity and fluctuations in a hypersonic turbulent boundary layer using acetone tagging velocimetry. Exp. Fluids 64, 122 (2023).

Boedeker, L. R. Velocity measurement by H2O photolysis and laser-induced fluorescence of OH. Opt. Lett. 14, 473–475 (1989).

Wehrmeyer, J. A., Ribarov, L. A., Oguss, D. A. & Pitz, R. W. Flame flow tagging velocimetry with 193-nm H2O photodissociation. Appl. Opt. 38, 6912–6917 (1999).

Pitz, R. W. et al. Hydroxyl tagging velocimetry in a supersonic flow over a cavity. Appl. Opt. 44, 6692–6700 (2005).

André, M. A., Bardet, P. M., Burns, R. A. & Danehy, P. M. Characterization of hydroxyl tagging velocimetry for low-speed flows. Meas. Sci. Technol. 28, 085202 (2017).

McDaniel, J. C., Hiller, B. & Hanson, R. K. Simultaneous multiple-point velocity measurements using laser-induced iodine fluorescence. Opt. Lett. 8, 51–53 (1983).

Balla, R. J. Iodine tagging velocimetry in a Mach 10 wake. AIAA J. 51, 1–3 (2013).

Dam, N., Klein-Douwel, R. J. H., Sijtsema, N. M. & Meulen, J. J. Nitric oxide flow tagging in unseeded air. Opt. Lett. 26, 36–38 (2001).

Danehy, P. M., O’Byrne, S., Houwing, A. F. P., Fox, J. S. & Smith, D. R. Flow-tagging velocimetry for hypersonic flows using fluorescence of nitric oxide. AIAA J. 41, 263–271 (2003).

Bathel, B. F. et al. Velocity profile measurements in hypersonic flows using sequentially imaged fluorescence-based molecular tagging. AIAA J. 49, 1883–1896 (2011).

Sánchez-González, R., Srinivasan, R., Bowersox, R. D. W. & North, S. W. Simultaneous velocity and temperature measurements in gaseous flow fields using the venom technique. Opt. Lett. 36, 196–198 (2011).

Sánchez-González, R., Bowersox, R. D. W. & North, S. W. Simultaneous velocity and temperature measurements in gaseous flowfields using the vibrationally excited nitric oxide monitoring technique: a comprehensive study. Appl. Opt. 51, 1216–1228 (2012).

Sánchez-González, R., Bowersox, R. D. W. & North, S. W. Vibrationally excited NO tagging by NO(A2Σ+) fluorescence and quenching for simultaneous velocimetry and thermometry in gaseous flows. Opt. Lett. 39, 2771–2774 (2014).

Sánchez-González, R., McManamen, B., Bowersox, R. D. W. & North, S. W. A method to analyze molecular tagging velocimetry data using the Hough transform. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 86, 105106 (2015).

S. Matos, P. A., Barreta, L. G. & Martins, C. A. Velocity and NO-Lifetime Measurements in an Unseeded Hypersonic Air Flow. J. Fluids Eng. 140, 121105 (2018).

Leonov, B., Jiang, N., Siddiqui, F., Roy, S. & Miles, R. Seedless velocimetry of high-enthalpy hypersonic boundary layers by nitric-oxide ionization induced flow tagging and imaging at 100 kHz. Opt. Lett. 50, 205–208 (2025).

Jiang, N. et al. Long-lived nitric oxide molecular tagging velocimetry with 1+ 1 REMPI. Opt. Lett. 49, 1297–1300 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Resonant-enhanced multiphoton ionization of nitric oxide (NO) tagging velocimetry in a detonation-driven hypersonic shock tunnel. Phys. Fluids 36, 081701 (2024).

Michael, J. B., Edwards, M. R., Dogariu, A. & Miles, R. B. Femtosecond laser electronic excitation tagging for quantitative velocity imaging in air. Appl. Opt. 50, 5158–5162 (2011).

Edwards, M. R., Dogariu, A. & Miles, R. B. Simultaneous temperature and velocity measurements in air with femtosecond laser tagging. AIAA J. 53, 2280–2288 (2015).

Jiang, N. et al. Selective two-photon absorptive resonance femtosecond-laser electronic-excitation tagging velocimetry. Opt. Lett. 41, 2225–2228 (2016).

Jiang, N. et al. Seedless velocimetry at 100 khz with picosecond-laser electronic-excitation tagging. Opt. Lett. 42, 239–242 (2017).

Burns, R. A., Danehy, H. P. M. & Jiang, B. R. N. Femtosecond laser electronic excitation tagging velocimetry in a transonic, cryogenic wind tunnel. AIAA J. 55, 680–685 (2017).

Mills, J. L. Investigation of Multi-Photon Excitation in Argon with Applications in Hypersonic Flow Diagnostics. PhD thesis, Old Dominion University (2016).

Pitz, R. W. et al. Unseeded velocity measurement by ozone tagging velocimetry. Opt. Lett. 21, 755–757 (1996).

Pitz, R. W. et al. Unseeded molecular flow tagging in cold and hot flows using ozone and hydroxyl tagging velocimetry. Meas. Sci. Technol. 11, 1259–1271 (2000).

ElBaz, A. M. & Pitz, R. W. N2O molecular tagging velocimetry. Appl. Phys. B 106, 961–969 (2012).

Arisman, C. J., Johansen, C. T., Bathel, B. F. & Danehy, P. M. Investigation of gas seeding for planar laser-induced fluorescence in hypersonic boundary layers. AIAA J. 53, 3637–3651 (2015).

Mills, J. L., Sukenik, C. I. & Balla, R. J. Hypersonic wake diagnostics using laser induced fluorescence techniques. In Proc. 42nd AIAA Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference (AIAA 2011-3459, Honolulu, Hawaii, 2011).

Parziale, N. J., Smith, M. S. & Marineau, E. C. Krypton tagging velocimetry of an underexpanded jet. Appl. Opt. 54, 5094–5101 (2015).

Zahradka, D., Parziale, N. J., Smith, M. S. & Marineau, E. C. Krypton tagging velocimetry in a turbulent Mach 2.7 boundary layer. Exp. Fluids 57, 62 (2016).

Mustafa, M. A., Parziale, N. J., Smith, M. S. & Marineau, E. C. Nonintrusive freestream velocity measurement in a large-scale hypersonic wind tunnel. AIAA J. 55, 3611–3616 (2017).

Mustafa, M. A. & Parziale, N. J. Simplified read schemes for krypton tagging velocimetry in N2 and air. Opt. Lett. 43, 2909–2912 (2018).

Mustafa, M. A., Parziale, N. J., Smith, M. S. & Marineau, E. C. Amplification and structure of streamwise-velocity fluctuations in compression-corner shock-wave/turbulent boundary-layer interactions. J. Fluid Mech. 863, 1091–1122 (2019).

Mustafa, M. A., Shekhtman, D. & Parziale, N. J. Single-laser krypton tagging velocimetry investigation of supersonic Air and N2 boundary-layer flows over a hollow cylinder in a shock tube. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 064013 (2019).

Shekhtman, D., Yu, W. M., Mustafa, M. A., Parziale, N. J. & Austin, J. M. Freestream velocity-profile measurement in a large-scale, high-enthalpy reflected-shock tunnel. Exp. Fluids 62, 1–13 (2021).

Jiang, N. et al. Mach 18 flow velocimetry with 100-kHz KTV and PLEET in AEDC tunnel 9. Appl. Opt. 62, 25–30 (2023).

Shekhtman, D., Hameed, A., Segall, B.A., Dworzanczyk, A. R. & Parziale, N. J. Initial shakedown testing of the stevens shock tunnel. In Proc. AIAA SciTech 2022 (AIAA 2022-1402, San Diego, California and Virtual Event, 2022).

Segall, B. A., Shekhtman, D., Langhorn, J. & Parziale, N. J. Improved debris blocker and flow terminator in a shock tunnel. In Proc. AIAA Scitech 2024 (AIAA 2024-2570, Orlando, Florida, 2024).

Goodwin, D. G., Moffat, H. K., Schoegl, I., Speth, R. L. & Weber, B. W. Cantera: An Object-oriented Software Toolkit for Chemical Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Transport Processes. https://www.cantera.org (2022).

Browne, S. T. et al. Numerical Solution Methods for Shock and Detonation Jump Conditions (GALCIT - FM2018-001, Caltech, 2018).

Korte, J. J. et al. Determination of hypervelocity freestream conditions for a vibrationally frozen nitrogen flow. In Proc. AIAA SciTech 2021 (AIAA-2021-0981, Virtual Event, 2021).

Chen, J. H., Hameed, A., Parziale, N. J., Roy, D. & Duan, L. Spectral analysis of mach 6 turbulent boundary layer over a hollow cylinder with FLDI and DNS. In Proc. AIAA Scitech 2024 (AIAA 2024-2734, Orlando, Florida, 2024).

Shekhtman, D., Mustafa, M. A. & Parziale, N. J. Excitation line optimization for krypton tagging velocimetry and planar laser-induced fluorescence in the 200-220 nm range. In Proc. AIAA SciTech 2021 (AIAA-2021-1300, Virtual Event, 2021).

Grib, S. W. et al. 100 khz krypton planar laser-induced fluorescence imaging. Opt. Lett. 45, 3832–3835 (2020).

Demtröder, W. Atoms, Molecules, and Photons: An Introduction to Atomic-, Molecular, and Quantum-Physics 3rd edn (Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, 2018).

O’Haver, T. A Pragmatic Introduction to Signal Processing (University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, 1997).

Segall, B. A. et al. Debris blocker and flow terminator for a shock tunnel. AIAA J. 61, 2739–2743 (2023).

Hill, R. B. & Klewicki, J. C. Data reduction methods for flow tagging velocity measurements. Exp. Fluids 20, 142–152 (1996).

Smeets, G. & George, A. Gas Dynamic Investigations in a Shock Tube using a Highly Sensitive Interferometer. Translation of ISL Internal Report 14/71 (Original 1971, Translation 1996).

Smeets, G. Laser interferometer for high sensitivity measurements on transient phase objects. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems AES-8 186–190 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 1972).

Smeets, G. & George, A. Anwendungen des Laser-Differentialinterferometers in der Gasdynamik. ISL - N 28/73, Also translated by Goetz, A.: ADA-307459 (1973).

Smeets, G. Laser-Interferometer mit grossen, fokussierten Lichtbündeln für lokale Messungen. Institut Saint-Louis Report ISL - N 11/73 (Institute of Saint-Louis (ISL), 1973).

Smeets, G. Verwendung eines Laser-Differentialinterferometers zur Bestimmung lokaler Schwankungsgrössen sowie des mittleren Dichteprofils in cinem turbulenten Freistrahl. ISL - N 20/74 (Institute of Saint-Louis (ISL), 1974).

Smeets, G. Flow diagnostics by laser interferometry. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. AES-13, 82–90 (1977).

Smeets, G. & George, A. Laser differential interferometer applications in gas dynamics. Translation of ISL Internal Report 28/73 (Original 1975, Translation 1996).

Ceruzzi, A. P. & Cadou, C. P. Simultaneous velocity and density gradient measurements using two-point focused laser differential interferometry. In Proc. AIAA Scitech 2019 (AIAA-2019-2295, San Diego, California, 2019).

Parziale, N. J., Shepherd, J. E. & Hornung, H. G. Reflected shock tunnel noise measurement by focused differential interferometry. In Proc. 42nd AIAA Fluid Dynamics Conference and Exhibit (AIAA-2012-3261, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2012).

Parziale, N. J., Jewell, J. S., Shepherd, J. E. & Hornung, H. G. Optical detection of transitional phenomena on slender bodies in hypervelocity flow. In Proc. RTO Specialists Meeting AVT-200/RSM-030 on Hypersonic Laminar-Turbulent Transition (NATO, San Diego, California, 2012).

Parziale, N. J., Shepherd, J. E. & Hornung, H. G. Differential interferometric measurement of instability at two points in a hypervelocity boundary layer. In Proc. 51st AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting Including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition (AIAA-2013-0521, Grapevine, Texas, 2013).

Parziale, N. J., Shepherd, J. E. & Hornung, H. G. Differential interferometric measurement of instability in a hypervelocity boundary layer. AIAA J. 51, 750–753 (2013).

Parziale, N. J. Slender-Body Hypervelocity Boundary-Layer Instability. PhD thesis, California Institute of Technology (2013).

Parziale, N. J., Shepherd, J. E. & Hornung, H. G. Free-stream density perturbations in a reflected-shock tunnel. Exp. Fluids 55, 1665 (2014).

Parziale, N. J., Shepherd, J. E. & Hornung, H. G. Observations of hypervelocity boundary-layer instability. J. Fluid Mech. 781, 87–112 (2015).

Paquin, L. A., Hameed, A., Parziale, N. J. & Laurence, S. J. Time-resolved wave packet development in highly cooled hypersonic boundary layers. J. Fluid Mech. 983, 36 (2024).

Driest, E. R. On turbulent flow near a wall. J. Aeronaut. Sci. 23, 1007–1011 (1956).

Huang, P. G. & Coleman, G. N. Van Driest transformation and compressible wall-bounded flows. AIAA J. 32, 2110–2113 (1994).

Huang, J., Duan, L. & Choudhari, M. M. Direct numerical simulation of hypersonic turbulent boundary layers: effect of spatial evolution and Reynolds number. J. Fluid Mech. 937, 3 (2022).

Zhang, Y.-S., Bi, W.-T., Hussain, F. & She, Z.-S. A generalized Reynolds analogy for compressible wall-bounded turbulent flows. J. Fluid Mech. 739, 392–420 (2014).

Walz, A. Compressible turbulent boundary layers with heat transfer and pressure gradient in flow direction. J. Res. Natl Bur. Stand. B 63B, 53–70 (1959).

Zhao, Z. & Fu, L. Revisiting the theory of van Driest: a general scaling law for the skin-friction coefficient of high-speed turbulent boundary layers. J. Fluid Mech. 1012, R3 (2025).

Marusic, I. et al. Wall-bounded turbulent flows at high Reynolds numbers: recent advances and key issues. Phys. Fluids 22, 065103 (2010).

Yu, M., Xu, C.-X. & Pirozzoli, S. Genuine compressibility effects in wall-bounded turbulence. Phys. Rev. Fluids 4, 123402 (2019).

Dogan, E., Hanson, R. E. & Ganapathisubramani, B. Interactions of large-scale free-stream turbulence with turbulent boundary layers. J. Fluid Mech. 802, 79–107 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Eric Marineau of the Office of Naval Research (ONR) for his technical counsel and encouragement, efforts that go beyond the typical responsibilities of a program officer. Labor and supplies from ONR-YIP N00014-20-1-2549 and ONR-BAA N00014-23-1-2474. Equipment from FA9550-15-1-0325, FA9550-19-1-0182, N00014-20-1-2637, N00014-23-1-2474, and N00014-24-1-2202. Dr. Ivett Leyva, then of the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR), supported the development of KTV with the AFOSR-YIP FA9550-16-1-0262. Thank you to Professor Lian Duan for sharing their DNS data. Thank you to Dr. Ammar Mustafa of General Electric and Mr. Mike Smith of AEDC Tunnel 9 for their work in developing the KTV diagnostic in its nascent stages. Thank you to the Spectral Energies team for their hard work and help with the OPO under FA9101-17-P-0094/FA2487-19-C-0013. Thank you to Mills, Sukenik, and Balla62 for sharing their original ideas on metastable Kr as a tagging tracer in a conference paper. All grants were proposed and administered by NJP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.A.S., T.C.K., and D.S. designed and executed the KTV experiments in the Stevens Shock Tunnel (SST) with the BML/OPO. J.C.K. and A.H. performed the FLDI measurements and helped run the SST. J.D.L. helped run the SST. N.J.P. helped design and execute the experiments, and served as PI.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Segall, B.A., Keenoy, T.C., Kokinakos, J.C. et al. Hypersonic turbulent quantities in support of Morkovin’s hypothesis. Nat Commun 16, 9584 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65398-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65398-4