Abstract

Tissue spheroids fuse to form larger tissue structures, a process controlled by their living material properties. However, how these properties emerge from the active behavior of individual cells is not well understood. Here, we studied fusion dynamics of spheroids from human periosteum-derived cells. Using confocal microscopy, we measured spheroid granularity and, with two-photon microscopy, we quantified active cell movements during fusion. Inhibiting cytoskeletal contractility with Y-27632 Rho kinase inhibitor produced more granular tissues with fewer cell rearrangements but faster fusion. Further reducing contractility with blebbistatin and Y-27632 increased granularity, reduced rearrangements, and slowed fusion. Across all conditions, complete fusion coincided with frequent cell rearrangements. We present an active foam model representing cells as viscous shells with interfacial tension and persistent motility to link fusion outcomes and tissue fluidity to measurable cell properties. This framework shows how cell activity regulates tissue mechanics and offers insights for tissue assembly in regenerative medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tissue spheroids are small self-organized cell aggregates resembling tissues or micro-tumors. They offer a versatile platform for exploring cellular behavior in a 3D context1 and play an important role in drug discovery, disease modeling, and various applications in regenerative medicine2. Their small size effectively overcomes diffusion limitations encountered in larger tissues, while their self-organized 3D micro-environment serves as an optimal setting for recapitulating various developmental pathways, including chondrogenic differentiation3,4,5. In tissue engineering, they serve as building blocks for tissue grafts that are suitable for transplantation6,7.

An essential step in the assembly of tissue spheroids into larger tissues is the fusion of two spheroids. Fusion not only serves as the unit operation for the fabrication of larger tissue constructs, but it also offers a controlled, in vitro setting to study the properties of cellular condensations in development8. Spheroid fusion can be modeled as the coalescence of two viscous droplets driven by surface tension, forming a single spherical aggregate by minimizing free surface energy9. In this model, fusion dynamics depend on spheroid size, material viscosity, and effective surface tension10. Spheroid fusion may also arrest, preserving aspects of the original spheroid shape and spatial structure in large tissue constructs11,12. Arrest.ed dynamics can be modeled by the buildup of elastic energy during fusion13. At the cell scale, this apparent elastic energy stems from the inability of cells to undergo topological rearrangements, where cells switch neighbors14. As such, it relates to the jamming transition, in which cells effectively become caged in their local neighborhood due to energy barriers resulting from cell-cell adhesion, or from the rigidity of the nucleus, the cell or the extracellular matrix15. External forces, but also the presence of internal active forces due to motility, can help overcome these energy barriers to recover tissue fluidity16.

Interest in rigidity transitions has grown due to their crucial role in tissue transformations where phenotypic transitions are enabled, such as those encountered in embryonic development and disease17,18,19,20. These transitions allow tissues to rapidly shift between viscous and elastic behaviors during development21,22. Still, the implications of these transitions for tissue engineering and biofabrication applications remain largely unexplored. Although cell motility is expected to influence both the degree of fusion and the time scale, there is no overarching theory linking fluidized or jammed cellular-scale states to tissue-scale viscoelastic and rheological properties23. Computational models such as the vertex24 and self-propelled Voronoi model16 have greatly advanced our understanding of the jamming transition in biology. More recently, these models have been extended into “active foam” frameworks that represent cells as soft, space-filling bubbles capable of generating internal forces25,26,27. This approach allows simulation of both the shape and movements of cells, including the formation of dynamic intercellular spaces. Foam-like models have also proven effective for inferring mechanical forces from the 3D geometry of cells in tightly packed aggregates28,29. However, current foam models lack the capability to capture the active 3D dynamics of tissue spheroids.

In this work, we investigate the fusion dynamics of small spheroids of human periosteum-derived cells (hPDCs) used in bottom-up bone and cartilage engineering3. HPDCs are instrumental for the formation of the fracture callus, a transient cartilaginous tissue that enables fracture healing30. For skeletal tissue engineering, in vitro multicellular condensations of these cells have been engineered to replicate skeletal developmental cascades3,30. By combining microscopy experiments, visco-elastic theory and simulations of an active foam model, we explore the link between fusion dynamics and the microscopic fluidized or jammed state of the tissue material. Additionally, we uncover how tissue fluidity scales with active mechanical properties at the cellular scale.

Results

Small tissue spheroids display visco-elastic fusion dynamics

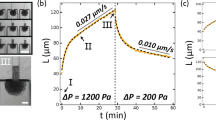

To obtain statistically reliable data on fusion dynamics, we conducted high-throughput time-lapse microscopy of fusing spheroids containing approximately 100 hPDCs in chondrogenic combination medium (C8), comprising Y-27632 Rho kinase inhibitor (ROCKi) and TGF-β1, along with other components (Fig. 1A). ROCKi, an inhibitor of the Rho-ROCK signaling pathway, is known for suppressing actin polymerization31 and has been previously shown to qualitatively influence aggregation dynamics32 and enhance fusion capacity3. TGF-β, an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition inducer, is recognized for its role in promoting chondrogenesis in mesenchymal cells33,34. We characterized the fusion angle θ based on the analogy between spheroid fusion and the coalescence of two spherical droplets (Fig. 1B). Elimination of ROCKi resulted in deceleration of fusion (Fig. 1C). In an effort to diminish cellular force generation, we enriched the medium with a higher concentration (100 μM) of ROCKi and introduced 20 μM of blebbistatin, an inhibitor of non-muscle myosin II that reduces cell contractility. These conditions led to a distinct slowdown in fusion dynamics. Yet, viability was maintained and fusion persisted. Finally, we inhibited actin disassembly with jasplakinolide35. This strongly impaired spheroid fusion, indicating that cytoskeletal remodeling is essential for spheroid fusion (Supplementary Fig. 1). To quantify differences in fusion dynamics, we fitted individual fusion curves with a solution to the governing equation for fusion of visco-elastic droplets13,

Here, τΓ = R0ηt/Γ is the visco-capillary time and \({\tau }_{\varepsilon }=4{\eta }_{t}/{G}^{{\prime} }\) is the visco-elastic time, with initial spheroid radius R0, tissue viscosity ηt, tissue surface tension Γ, and shear modulus \({G}^{{\prime} }\). This model fits the data well under all studied conditions (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). We extracted two key fusion parameters: the equilibrium fusion angle θeq, with \(\sec ({\theta }_{eq})-\cos ({\theta }_{eq})=4\Gamma /({G}^{{\prime} }{R}_{0})\), and the fusion time-scale \({\tau }_{f}=4{\tau }_{\Gamma }{\tau }_{\varepsilon }/{(4{\tau }_{\Gamma }^{2}+{\tau }_{\varepsilon }^{2})}^{1/2}\). Spheroids cultured in the absence of ROCKi exhibited significantly longer fusion times compared to the baseline C8 condition (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, the fusion time was significantly increased for spheroids with blebbistatin and elevated levels of ROCKi. Despite large variation between replicates, most conditions exhibit nearly complete coalescence, with equilibrium fusion angles close to 90° (Fig. 1E). We also examined an alternative model for viscoelastic fusion dynamics, proposed by Beaune et al. (2022)36 based on earlier work on tissue spreading37. This approach assumes that both viscous dissipation and elastic deformation are confined to the contact region between fusing bodies (see Supplementary Notes for details). When we fitted this model to our data, the results were consistent with our primary findings: We observed a reduction in the characteristic elastic length scale following treatment with blebbistatin and ROCK inhibitor (Supplementary Figs. 5, 6).

In 4 conditions: C8 medium (C8), C8 w/o Y-27632 Rho kinase inhibitor (ROCKi−), C8 w/o TGF-β1 (TGF−) and C8 + 100 μm Y-27632 Rho kinase inhibitor and 25 μm blebbistatin (Bleb/ROCKi+). A bright-field microscopy snapshot at 0, 120, 300 and 1440 min after the start of fusion. Results are representative of 5 independent biological repeats shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. B Illustration of the fusion angle θ, with fitted circular contours for each spheroid. C Temporal evolution of the average fusion angle for 4 treatment conditions, together with the fit of Eq. (1). Data acquired from a single experiment, n = 7, 10, 8, 9, for resp. C8, ROCKi−, TGF−, Bleb/ROCKi+. D Fusion timescale τf and E Equilibrium fusion angle θeq for 4 treatment conditions. Data is pooled from 5 different experiments, see Supplementary Fig. 2, with n = 38, 46, 44, 22 for resp. C8, ROCKi−, TGF−, Bleb/ROCKi+. Horizontal bars represent the mean and data extrema (min-max). Significance with two-sided Dunnett’s test comparing treatments versus C8. n.s.: p > 0.05, ***: p < 0.001, ROCKi−: p = 6.22E-11; TGF−: p = 0.62; Bleb/ROCKi+: p = 1.82E-10.

Micro-structure and dynamics reveal distinct cell mechanics and motility

Subsequently, we investigated the relation between fusion dynamics and micro-structure and dynamics at the cell scale. Cell-cell interfacial tension governs tissue surface tension (Γ) at the spheroid scale38,39,40, which in turn sets the fusion time-scale τf. In a foam, the relative interfacial tension is discernible in the contact angle at triple junctions28. We used confocal microscopy imaging to reveal the shape and internal structure of individual spheroids in four conditions. In the absence of ROCK inhibition, both nuclei and actin structures exhibited increased orientation in the circumferential direction compared to other conditions, which displayed a more isotropic distribution (Fig. 2A). Additionally, distinct differences in spheroid shape granularity were observed between conditions. To quantify these differences in granularity, we analyzed the angular distribution of curvature in cells at the periphery of the spheroid (Fig. 2B). From this analysis, we define the granular shape index as GSI = r(κ − 1/R), where r is the mean cell radius, R the spheroid radius, and κ the median sector curvature (Fig. 2C). The GSI is zero for a perfectly smooth spherical aggregate and approaches 1 for a loosely packed, granular cell arrangement with radius r. Through the simulation of a static foam with surface tension γ and adhesive tension w, we found that, for sufficiently large aggregates (>50 cells), the GSI well approximates the relative cell-cell tension GSI ≈ α = 1 − w/γ (Supplementary Fig. 7). Unlike methods that estimate α using contact angles21,41, this approach avoids the potentially error-prone task of precisely delineating cell-cell interfaces, especially in smooth, spherical aggregates. The GSI was approximately 0.5 for C8 both with and without TGF-β1, dropped significantly to around 0.25 in the absence of ROCKi, and increased significantly, approaching 0.75, with blebbistatin and elevated ROCKi levels (Fig. 2D). Thus, while cell-cell tension governs tissue surface tension, the observation of faster fusion times in C8 implies that fusion time cannot be directly inferred from cell-cell tension alone, as additional factors likely contribute.

A Confocal microscopy slices of spheroids in conditions C8, ROCKi−, TGF− and Bleb/ROCKi+, with stainings DAPI (nucleus), Phalloidin (actin) and CellBrite (membrane). Representative images from 2 independent biological repeats for C8, ROCKi−, and TGF−, and 1 repeat for Bleb/ROCKi+. Total spheroids imaged: C8, 1+4; ROCKi−, 3+8; TGF−, 3+3; Bleb/ROCKi+, 4. B Circular approximation of spheroid periphery, showing contour radii and contact angles for conditions C8, ROCKi−, and Bleb/ROCKi+. C Cumulative distribution of contour curvature, extracted from contour circles, in 4 conditions. Data is pooled with n = 5, 10, 6 and 4 for resp. C8, ROCKi−, TGF− and Bleb/ROCKi+. D Granular Shape Index (GSI) for 4 conditions. Data is from individual spheroids as used in (C). Horizontal bars indicate the mean for each condition. Significance with two-sided Dunnett’s test, comparing treatments versus C8. n.s: p > 0.05, *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01. ROCKi−: p = 0.003; TGF−: p = 0.92; Bleb/ROCKi+: p = 0.016. E Time-lapse of cell nuclei (DAPI staining) from two-photon microscopy imaging, colored by z-position (relative to the bottom of the spheroid). F Cell trajectories traced from time-lapse two-photon confocal microscopy imaging of tissue spheroid fusion for 4 conditions. The color scale indicates the elapsed time for each trajectory. G Time-averaged mean squared relative displacement (MSRD) for fusing spheroids in 4 conditions, showing mean (full line) and standard deviation (shaded region) for n = 3 for all conditions. The dashed line indicates diffusive behavior (exponent ν = 1). H Effective relative diffusivity for a lag time of 1 h, computed as Deff,Δt = MSRD(Δt)/(6Δt) for 4 conditions. Horizontal bars indicate the mean for each condition. Significance was assessed using a two-sided Welch’s t-test. *: p < 0.05. C8 vs. ROCKi−: p = 0.19; C8 vs. TGF−: p = 0.92; C8 vs. Bleb/ROCKi+: p = 0.51; ROCKi− vs. TGF−: p = 0.045; ROCKi− vs. Bleb/ROCKi+: p = 0.022; TGF− vs. Bleb/ROCKi+: p = 0.10. All scale bars represent 50 μm.

We then explored the impact of active cell motility on fusion dynamics. Using time-lapse two-photon microscopy, we observed fusing spheroids across the 4 studied conditions (Fig. 2E). Cell trajectories were determined by tracking nucleus positions (Fig. 2F), and we computed the time-averaged mean squared relative displacement (MSRD) for all initially neighboring cell pairs. These relative displacements signify cellular rearrangements that are expected to occur frequently in a fluidized state while being nearly absent in a solid, jammed tissue state25. In all cases, we observed mild sub-diffusive behavior in the MSRD (Fig. 2G). However, in all conditions, the lag time for topological rearrangements or mixing time, signified by MSRD > r2, was under one hour, confirming that the tissue material exhibited fluid-like behavior within the experimental timescale. Based on the MSRD at a 1-h lag time (Fig. 2H), we estimated effective relative diffusivities ranging from 7 to 52 μm2/h, consistent with previous values for encapsulated microparticles36. We found that the relative diffusivity was greater in the absence of ROCKi compared to blebbistatin and elevated ROCKi, consistent with the known function of Rho kinase inhibitor in suppressing cytoskeletal rearrangements and subsequently reducing cell motility42. Interestingly, despite decreased relative cell-cell tension and increased cell motility, fusion proceeded notably slower in the absence of ROCKi compared to C8, which contains ROCKi. Upon elimination of TGF-β1, granularity and relative displacements showed no significant differences from C8, consistent with similar fusion dynamics.

Active foam model captures observed fusion dynamics

To study the physical behavior of multicellular aggregates during tissue fusion, we developed a 3D active foam model in which each cell is treated as a soft, deformable entity. The model mimics how cells interact, move, and deform under mechanical forces, similar to how bubbles behave in a foam. Cells are modeled as pressurized cortical shells with average radius r, planar viscosity η and free surface tension γ. They interact via adhesive tension w, representing the reduction of interfacial tension at the cell-cell interface43, and migrate via persistent, random protrusion forces (Fig. 3A). The key physical parameters governing fusion are: i) the relative cell-cell tension α = 1 − w/γ, ii) the relative active pressure par/2γ, iii) the persistence time τp, and iv) the hydrodynamic length Lη = (η/ξ)1/2 with cell-cell friction constant ξ44. Observing diffusive behavior in the mean-squared relative displacements for all lag times (Fig. 2G), we infer that τp ≪ τf. We further adimensionalize time by τp. Additionally, we first assume that the viscous length scale is significant, implying low cell-cell friction, setting Lη/r = 0.5. Through modulation of cell-cell tension α and subsequent condensation and equilibration, we produced virtual tissue spheroids containing 100 cells with varying levels of granularity, as shown in Fig. 3B. When brought into contact, the simulated spheroids underwent spontaneous fusion (Fig. 3C, Supplementary Movie 1–3). In line with our experimental observations, fusion dynamics closely align with the analytical solution derived from the governing equation of visco-elastic fusion, Eq. (1), both when varying cell-cell tension Fig. 3D and cell motility (Fig. 3E). This permits the estimation of the equilibrium fusion angle and the fusion time scale from simulations. When varying both par/2γ and α, we found that complete fusion (θeq → 90°) requires high motility and low relative cell-cell tension, i.e., high adhesive tension (Fig. 3F). Conversely, arrested coalescence occurred in conditions of low motility and/or high cell-cell tension. Fusion time-scale first increases with pa at low motility, while it decreases with pa at higher levels of motility (Fig. 3G, Supplementary Fig. 8).

A Model overview, showing cells with surface tension γ at the cell-medium interface, viscosity η and active pressure pa, interacting with adhesive tension w and cell-cell friction ξ. B Cross-sections of simulated spheroids at cell-cell tension α = [0.25, 0.50, 0.75], together with the GSI obtained as in the experiments (Fig. 2D). C Temporal snapshots of simulated fusion for α = 0.25, 0.5 and 0.75 at par/2γ = 0.45. D Temporal evolution of the average simulated fusion angle at fixed active pressure par/2γ = 0.34 and varying α, together with fitted dynamics using Eq. (1). E Temporal evolution of the average simulated fusion angle at fixed α = 0.56 and varying pa, together with fitted dynamics. F Equilibrium fusion angle θeq for varying α and pa. G Fusion time-scale τf for varying α and pa. Vertical and horizontal dashed lines in (F) and (G) indicate the parameter range for resp. panels (D) and (E). Hatched data points in (F, G) show simulations that failed to converge at high motility and low α due to highly negative surface tension at the cell front (par/2γ ≫ α). All values shown in (D–G) correspond to the average over 10 random repeats.

Fusion outcome reflects microscopic tissue fluidity

By tracking simulated cells, we then measured the time-averaged mean-squared relative displacement, mirroring the experimental procedure (Fig. 4A, B). As cellular motility increases and cell-cell tension decreases, we observe a transition in the mean-squared relative displacement. At low motility, it shows a sub-diffusive plateau at intermediate lag times, indicating a jammed configuration45, which vanishes at higher cell motility, suggesting a fluidized state. We then analyzed cell rearrangements by counting unique contacts during fusion, a measure indicating fluidity (Fig. 4C). The critical active pressure to fluidize the tissue material appears to scale as pa,crit ∝ α−1/2. In the studied range of cell-cell tension α, the tissue is mostly confluent21. In this regime, the ability of cells to deform is expected to drive topological rearrangements24. The role of cell deformation in tissue fluidity is evident in the 3D shape index S/V2/3, with cell area S and volume V (Fig. 4D). The critical shape index of 5.41, which was previously derived from a 3D Voronoi model46, effectively marks the jamming transition at high levels of cell motility. Through the variation of parameters α, pa, τp, and γ, we identified a dimensionless activity parameter \({{{\mathscr{A}}}}\) that collapses the scaling of cell rearrangements,

with τγ = η/γ (Fig. 4E, Supplementary Figs. 9, 10). For small spheroids, the effect of spheroid size on tissue fluidity is weak (Supplementary Figs. 11, 12). The observed scaling can be rationalized by a minimal model in which active protrusions must exceed a critical length \({L}_{a,y}^{*} > {r}_{a,\alpha \gamma }^{*}\) to grow, with protrusion radius \({r}_{a,\alpha \gamma }^{*}\propto \alpha \gamma /{p}_{a}\) (see “Methods”), akin to a micropipette aspiration threshold47. Modeling protrusion length as an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process with relaxation time τγ and effective diffusivity \({D}_{a}\propto {v}_{a}^{2}{\tau }_{p}\), where the active front velocity scales as va ∝ par2/η, yields a characteristic protrusion length \({L}_{a,y}^{*}\propto {({D}_{a}{\tau }_{\gamma })}^{1/2}\). This leads to the dimensionless activity scaling as \({{{{\mathscr{A}}}}}^{2}\propto {L}_{a,y}^{*}/{r}_{a,\alpha \gamma }^{*}\).

A Mean-squared relative displacements (MSRD) for varying cell-cell tension α at fixed motility par/2γ = 0.34. B MSRD for varying par/2γ at fixed α = 0.56. C Normalized unique contact number (total number of distinct cell-cell contacts formed over the full simulation, divided by the time-averaged number of contacts) for varying α and pa. Dashed lines show the scaling \(\alpha \propto {({p}_{a}r/2\gamma )}^{2}\). D 3D shape index S/V2/3 with cell surface area S and volume V for varying α and pa. The black line shows the iso-contour of shape index 5.4146. Hatched data points in (c,d) show simulations that failed to converge at high motility and low α. E Normalized unique contacts for varying pa (marker size), τγ (marker hatching), τp (marker shape) and α (marker color), see further Supplementary Figs. 12, 13, showing collapse of data points for \({{{\mathscr{A}}}}={p}_{a}r{({\alpha }^{1/2}\gamma )}^{-1}{({\tau }_{p}/{\tau }_{\gamma })}^{1/4}\). F Equilibrium fusion angle θeq vs. MSRD60 from combined simulations (for baseline value of τp = 100 s), colored by activity \({{{\mathscr{A}}}}\) and compared to experiments under four conditions. The dashed line indicates a LOESS trend of simulation data, providing a visual guide to the data trend, and the shaded region shows the local standard deviation. Inset: MSRD60 follows normalized unique contacts in simulations. G Temporal evolution of aggregate mixing for low (left) and high (right) levels of cell activity. H Normalized unique contact number (left) and equilibrium fusion angle (right) in function of Lη for varying α. All values shown in A-H correspond to the average over 10 random repeats.

In our simulations, the degree of coalescence is closely tied to microscopic tissue fluidity, as is evident from the comparison between the equilibrium fusion angle and the mean squared displacement for a fixed lag time, an experimentally accessible parameter that follows the normalized unique contact count (Fig. 3F). Jamming coincides with arrested coalescence, where θeq and, correspondingly, the tissue viscoelastic timescale τϵ, increase with activity. As the cellular material fluidizes, coalescence becomes complete, and τϵ → ∞. At high activity levels, the equilibrium fusion angle decreases again due to active shape fluctuations in the aggregate. When mapped onto this chart, and assuming a persistence time τp = 100 s, our experimental observations follow this general pattern. Interestingly, they are located close to the fluid-to-solid transition, which is approached with blebbistatin and elevated levels of ROCKi. Rearrangements due to cell activity also enhance mixing during fusion. At low activity, cells from separate spheroids maintain distinct interfaces. However, increased activity leads to the intermixing of cells from different spheroids in the timescale of fusion (Fig. 4G), resulting in the loss of distinct boundaries between the original tissues (Fig. 3C).

The active foam model treats cells as discrete entities capable of relative sliding, allowing us to evaluate the impact of cell-cell friction on spheroid fusion and fluidity. At slow timescales, the dynamic binding and unbinding of adhesive ligands lead to an effective wet friction, which is parameterized in our model by the hydrodynamic length-scale Lη48. Hence, increasing the bond lifetime of adhesive ligands corresponds to a decrease in Lη. As Lη decreases, the normalized unique contact count and the equilibrium fusion angle notably reduce (Fig. 4H), indicating that cell-cell friction facilitates arrested coalescence. Interestingly, jamming also occurs for elongated cells with a high shape index, suggesting that cell-cell friction offers a distinct mechanism to induce jamming compared to shape-dependent rigidity transitions24,46 (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Discussion

Small tissue spheroids are well-suited for examining tissue rheology in 3D due to their well-defined boundaries, compact size allowing for precise measurement of individual cell shape and dynamics, and the ability to study dynamic processes such as fusion, spreading, dispersion, and aspiration. In this work, we explored the fusion dynamics of small tissue spheroids, conceptualizing them as active cellular foams. In small spheroids of hPDCs, we found that complete fusion was associated with frequent cellular rearrangements, indicating fluidization of the tissue material. Reduction of actin polymerization and cell contractility through inhibition of ROCK resulted in more granular tissue shapes and decreased cell movements, but faster fusion. Further reducing cell contractility through blebbistatin and ROCKi led to more enhanced tissue granularity and decreased cell movements, but also slowed down fusion dynamics. These results add to prior findings in chondrogenic organoids. For instance, inhibition of ROCK during aggregate formation shifted dynamics from those of a dewetting liquid to an agitated granular pile32. Similarly, our results show increased spheroid granularity with inhibition of ROCK. Despite this granularity, fusion dynamics remained consistent with the coalescence of continuum, visco-elastic materials, both in experiments and simulations. However, the inferred relative cell-cell tension was below the critical value for internal pore formation (α ≈ 0.87521), indicating that these spheroids were internally confluent, unlike during aggregate formation.

To clarify the interplay between single-cell properties and tissue dynamics, we developed a dynamic 3D active foam model with discrete, deformable cells, parameterized by relative cell-cell tension and motility. This model reproduces characteristic fusion dynamics while capturing cell shape and relative motility. Our results show that complete fusion, corresponding to the coalescence of liquid droplets at the macroscopic level, is closely linked to tissue fluidization at the microscopic level, as illustrated in Fig. 5. This finding aligns with previous experimental studies reporting that enhanced fusion correlates with increased cell intermixing49,50. We uncovered a universal scaling relationship that links tissue fluidization to relative cell-cell tension, persistence time, cortical relaxation time, and active motility, through an effective activity parameter. Due to fluidization, significant variations in neighbor exchange rates are predicted between instances of near-complete coalescence. Hence, depending on cell activity, complete coalescence might involve either significant intermixing of cells from different spheroids or a quasi-stable tissue interface. This observation is relevant for biofabrication51,52, where independent control of coalescence and intermixing may be necessary. We found that the ability of cells to elongate governs the rigidity transition, in line with vertex and Voronoi model predictions24,46. Low cell-cell tension reduces energy barriers, allowing fusion akin to passive liquid behavior, while active migration forces are required to overcome these barriers at higher cell-cell tension. Classical foam and vertex models solely account for cell-cell interfaces, whereas our discrete foam model incorporates relative cell-cell sliding, which we associate with adhesive ligand or intercellular matrix turnover rates. Our results show that friction, while typically linked to transient phenomena, induces arrested fusion by promoting jamming through a distinct physical mechanism, consistent with recent phase field model predictions in cell monolayers53. The physical implication of cell-cell friction on tissue dynamics still needs to be explored for relevant biological mechanisms, such as cadherin turnover in epithelia54, or the dynamic remodeling of extracellular matrix in 3D tumors and organoids55.

At low activity, the tissue material is jammed, and arrested fusion may be observed (θeq < 90°). At high cell activity, the tissue material is fluidized and fusion is complete. Further increasing activity decreases the mixing time (lag time for which MSRD > r2) relative to the fusion time (Supplementary Fig. 15), resulting in homogenized cell aggregates. Based on relative cell-cell tension and apparent cell diffusion, the experimental conditions of C8, Bleb/ROCKi+ and ROCKi− can be located on this chart.

Comparison between predictions of the active foam model and our experimental observations highlights a few noteworthy similarities. Specifically, in the reference C8 chondrogenic medium, with τf ≈ 6.4 h, θeq ≈ 84°, and α ≈ 0.5, our fusion simulations are compatible with experimental outcomes at intermediate levels of cell motility, Fig. 3D–G. Furthermore, the observed increase in granularity, fusion slowdown, and decrease in relative motility after the addition of both ROCKi and blebbistatin align with simulation results at elevated α = 0.75 and reduced or equal cell motility. This treatment, as indicated by shape index and cell rearrangements, corresponds to a transition from a fluidized state to a more jammed material, see Fig. 5. Elimination of ROCKi led to reduced granularity and increased cell movement, but also decreased fusion time. In line with this, our active foam model predicts increased relative cell movements and decreased granularity at α ≈ 0.25 (Figs. 3B, 4A). However, while higher cell motility can slow fusion Fig. 3G, our model cannot replicate the slowdown in fusion observed with ROCKi removal. Decreasing α consistently speeds up fusion, and adjusting the cortical relaxation time in simulations does not match the observed increase in cell movement. This suggests the active foam model does not fully capture the biophysical changes associated with ROCKi removal, possibly due to the polarized cells with anisotropic actin structures seen in Fig. 2A. These structures, predominantly oriented in the circumferential direction, may impede radial cell movements necessary for spheroid fusion, thus slowing down fusion dynamics as they require remodeling. Future active foam models could investigate how anisotropic surface tension and cortex viscosity influence tissue structure and dynamics.

Through simulations, we demonstrated that two distinct fusion regimes, arrested and complete, are closely linked to the tissue (un)jamming transition. Below the unjamming transition, assembloid formation is akin to colloidal sintering, with the sintering degree tied to cellular activity. Beyond this transition, it resembles liquid droplet coalescence, where the mixing-to-fusion timescale ratio dictates long-term stability. These insights are crucial for the spatial and temporal assembly of large tissue constructs in biofabrication. In the future, these models can be expanded to incorporate interactions with encapsulating materials such as bioinks or the extracellular matrix. Our results on in vitro tissue spheroids provide insights into the physics of their in vivo counterparts, multicellular condensations, which play a crucial role in tissue patterning, organ formation, and cell differentiation. By taking into account the heterogeneity and asymmetries encountered in vivo, this theoretical framework has the potential to shed light on complex biological processes, including cell sorting, both in vivo and in their in vitro analogs.

Methods

Periosteal cell isolation and culture

HPDCs were isolated from periosteal biopsies of two female and four male donors aged between 11 and 17 years old. A single cell pool was created, and cells were seeded at a density of 5000 cells/cm2 for expansion. Cells were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity until passage 9 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Life Technologies, UK) enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone FBS, Thermo Scientific, USA) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (100 units/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin and 0.25 mg/mL amphotericin B). Expansion medium was changed every 3 days, and cells were dissociated using TrypLE™ Express (Life Technologies, UK) at a confluence of 90%. For all donors, informed consent was obtained, and all procedures were approved (S64471) by the ethical committee for Human Medical Research (KU Leuven).

Aggregate formation

Single-cell hPDCs suspension was seeded in U-bottom Ultra-low Attachment 96 well plates (PrimeSurface® 3D culture, S-BIO, Japan) with a density range of 60 to 90 cells per well in 200 μl of appropriate chemically defined chondrogenic medium formulation. The cells were left to form aggregates over 48 h at 37 °C 5% CO2, and 95% humidity before imaging. C8 consisted of LG-DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (100 units/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin and 0.25 mg/mL amphotericin B), 1 mM ascorbate-2 phosphate, 100 nM dexamethasone, 40 μg/mL proline, 20 μM of Rho-kinase inhibitor Y-27632 (Axon Medchem), ITS + Premix Universal Culture Supplement (Corning) (including 6.25 μg/mL insulin, 6.25 μg/mL transferrin, 6.25 μg/mL selenious acid, 1.25 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 5.35 μg/mL linoleic acid), 100 ng/mL BMP-2 (INDUCTOS®), 100 ng/mL GDF-5 (PeproTech), 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 (PeproTech), 1 ng/mL BMP-6 (PeproTech) and 0.2 ng/mL FGF-2 (PeproTech). TGF− consisted of the same supplements as C8, excluding TGF-β1. ROCKi− consisted of the same supplements as C8, excluding Y-27632. Bleb/ROCKi+ consisted of the same supplements as C8 with 100 μM instead of 20 μM Y-27632 and an additional 20 μM blebbistatin. A summary of medium compositions for the 4 studied conditions is provided in Supplementary Table 3. For treatment with jasplakinolide, two aggregates grown in C8 medium without ROCKi were transferred into a single well of a U-bottom Ultra-Low Attachment 96-well plate containing 100 μl of C8 medium without ROCKi (ROCKi−). Actin-stabilizing compound jasplakinolide (J4580, Sigma-Aldrich) was immediately added to the wells to achieve final concentrations of 1 μM, 0.5 μM, 0.25 μM, and 0 μM (as control).

Brightfield imaging of spheroid fusion

Two spheroids (48 h from seeding) were transferred per well of the U-bottom Ultra-low Attachment 96-well plate. To minimize variability, 12 replicates per condition were imaged simultaneously in a single well plate. After transfer, the plate was immediately placed in an OKOlab Top Stage Incubator with OKO-Air-Pump-BL, OKOlab 2GF-Mixer, and OKOlab T unit controller, all operated via an OKOlab Touch set at a temperature of 37 °C and a CO2 concentration of 5%. Wells containing two spheroids were selected and imaged with an Olympus IX53 microscope, SC30 Color Camera (Olympus), UPLFLN 10× magnification objective for 24 h with a 10 min interval. The CellSens Dimension (Olympus) software was used for image acquisition. This procedure was performed for 5 random repeats. Images were masked using the scikit-image library in Python and ImageJ56.

Fusion shape analysis

Fusion geometry was parameterized as \({\sin }^{2}(\theta )={(a/R)}^{2}\), with spheroid radius R (assuming equal sizes) and contact radius a, both evolving over time, see Fig. 1B. The following analysis was performed on each frame of the time-lapse microscopy sequence or active foam simulation. 1) Masks were smoothed by dilating and eroding with a kernel size of 3. For two large objects (indicating no contact), outer contour pixels were extracted from both. For a single large object (indicating fusion), the outer pixels of that object were extracted. 2) A double circle was fitted by searching for the center of mass points (xc,1, yc,1) and (xc,2, yc,2) that minimize the squared error on the distance from each contour pixel to the closest center of mass. For two separate objects, the center of mass was calculated by averaging the pixel positions. For a single object, an ellipse was fitted to the outer contour, and the initial guess was set at −0.5 and +0.5 along the major axis of the ellipse. The previous time step was considered as an extra initial guess, and the result with the lowest converged cost function was selected. 4) Upon convergence, the spheroid radius was determined from \({d}_{i}=\min ({d}_{i,1},{d}_{i,2})\). Using the circle centers and radius, the intersection points were calculated and subsequently the contact radius x, which is half the distance between the intersection points. Frames where circle fitting failed were excluded from the time series analysis of fusion dynamics. Additionally, due to the sparsity of cells in some aggregates and potential distortion of contours caused by loosely attached or detached cell clusters, or the presence of pronounced blebbing, the entire time series of fusion was discarded from the dataset.

Visco-elastic model for tissue spheroid fusion

Assuming that viscous dissipation and elastic deformation occur throughout the bulk of the fusing spheroids, fusion dynamics can be expressed as a function of visco-elastic material properties by the governing equation13

θ is the angle shown in Fig. 1B, and is influenced by the tissue surface tension Γ, the radius of the spheroid before fusion R0, the apparent tissue viscosity ηt and the shear modulus \({G}^{{\prime} }\) of the tissue. These parameters are combined into two characteristic time constants: τΓ is the visco-capillary time, and τε is the visco-elastic time. The analytical solution of Eq. (2) is

where the complex number C can be obtained from the initial conditions θ(t = 0) = θ0

Fusion dynamics are parameterized by the time scale τf and equilibrium angle θeq. Based on Eq. (3), we define τf as:

As τε → ∞, i.e., there is no elasticity, and we obtain τf = 4τΓ, When dominated by elasticity, i.e. τε → 0, τf = 2τε. Resubstituting \({\tau }_{\varepsilon }=4{\eta }_{t}/{G}^{{\prime} }\) and τΓ = ηtR0/Γ, we obtain

The equilibrium angle is

Hence, Eq. (3) can be written as

We fitted Eq. (4) to experimental and simulated fusion curves (t, θ) with fit parameters β, τf and θ0 using ‘curve_fit’ from the Python package SciPy57.

Confocal microscopy imaging

Aggregates were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 1 h at room temperature and washed with PBS. Aggregates were stained with the mixture of CellBrite® Fix 640 (1:1000, #30089-T, Biotinum), 1X Alexa Fluor™ 488 phalloidin (A12379, Invitrogen), 5 μg/ml Wheat Germ Agglutinin, Alexa Fluor™ 594 in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with 1 μg/ml DAPI for 15 min at room temperature. The aggregates were washed three times with PBS and mounted into Mowiol® 4–88 (Sigma, USA). Confocal imaging was performed with an LSM 780 confocal microscope (Zeiss) with a water-immersion 25× objective lens (NA 0.8, Zeiss).

Granular shape index

The granular shape index was defined as \(GSI=r\left(\kappa -1/R\right)\) where r is the (mean) cell radius, κ the curvature of the tissue spheroid, and R the spheroid radius. In the limit of high cohesion, the spheroid approximates a perfect sphere with radius R, so κ = 1/R and GSI = 0. Conversely, at low cohesion, with r ≪ R, the curvature κ ≈ 1/r, resulting in GSI → 1. Based on earlier experiments, the radius of hPDCs follows a Gamma distribution with shape factor k = 37 and scale factor ϑ = 0.24 μm, with average radius r = kϑ = 8.88 μm39. From confocal microscopy images, curvature κ was calculated as: 1) Slices were taken in the middle of the aggregate and contrast was adjusted to enhance contour visibility. 2) Based on a custom analysis tool in Python, we approximate a section (typically corresponding to a cell) by fitting a circle through 3 manually selected points. 3) Based on the intersection points of these circles, the intersection arc was determined, which forms the full contour of the aggregate slice, see Fig. 2B. 4) 1000 equidistant points were sampled along the contour and binned into 360 angular bins. κ(φ) is the mean curvature in each bin. Due to heavy tails in the curvature distribution from loose cells or blebs, Fig. 2C, κ is defined as the median of the binned curvature. 5) A circle is fitted through the equidistant contour points, searching for the center of mass point (xc,yc) for which the distance to each boundary pixel has the lowest squared error.

Two-photon imaging for cell tracking

hPDCs were labeled at 70% confluence in a T75 flask with 3 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (#H3570) in 10 ml of non-additive DMEM for 20 min at 37 °C. Cells were subsequently washed, trypsinized and seeded in a U-bottom Ultra-low Attachment 96-well plate as was done for brightfield imaging. The inclusion of Hoechst 33342 did not influence cell aggregation and aggregate fusion. Labeled 48h old aggregates were transferred into a bioinert Spheroid Perfusion μ-Slide (Ibidi, 80350, Germany) and subsequently imaged on an LSM 780 confocal microscope (Zeiss) with a water-immersion 25× objective lens (NA 0.8, Zeiss). A tunable Mai Tai DeepSee Titanium-Sapphire femtosecond laser (690–1040 nm, Spectra-Physics) set at 750 nm was used for 2-photon excitation, and fluorescence was detected in epi between 391–598 nm. Time-lapses were recorded with a 5 min interval for 10 h, a variable Z-stack range depending on the thickness of aggregates and a 0.29 × 0.29 × 1.7 μm voxel size. Images were adjusted for brightness and contrast and registered with descriptor-based registration plugins in ImageJ58.

Automated cell segmentation and tracking

From the confocal time-lapse series, Z-stacks were extracted for every time point and subsequently rescaled to obtain isotropic voxel dimensions. Every Z-stack was further split into 4 substacks of the Z-stack along the x- and y-directions, thus preserving the height, with a 10% overlap with neighboring substacks to reduce memory costs of computation. To account for the decay of intensity with distance from the objective, the slice-wise mean of the substacks was scaled with the overall mean intensity of the substack. The substacks were smoothed using a 3D Gaussian blur (σ = 1.5 μm), followed by a Frangi-Vesselness filter (α = 0.9, β = 0.9, γ = 1.0) to amplify blob-shaped objects. The Frangi-filtered substacks were thresholded using automatic Otsu’s thresholding to obtain a binary mask of blob-like objects of the substacks. These binary masks were recombined to the original Z-stack dimensions, preserving the maximal values in overlapping regions, thus reassembling nuclei that were potentially cut due to the separation in substacks. To obtain individual objects from the binary mask of the Z-stack, the binary mask was segmented using a watershed algorithm seeded from local maxima in the intensity signal. Foreground and background objects were separated by using Otsu’s threshold on the distribution of mean intensities of all segmented objects. Finally, to select the segmented nuclei, only large objects were retained by Otsu’s filtering of the volume of the foreground objects extracted from all the Z-stacks originating from a single time-lapse experiment. The tracking over time of the segmented nuclei was automatically performed using LapTrack59. Frame-to-frame linking of nuclei was performed by solving a Linear Assignment Problem (LAP) with the cost function being the squared Euclidean distance between the centroids of the nuclei in successive frames. The cut-off distance for linking nuclei was set to dc = 15 μm. Merging and splitting of tracks was not allowed.

Relative diffusion measurement

The squared relative displacement was calculated between cell pairs at various lag times (τ > 0),

where xij is the relative position of cells i and j, xij = xi − xj, \({{{\mathscr{C}}}}(\tau )\) is a set of ordered pairs of cells still observed at time τ after their first collision/proximity, N(τ) is the number of these pairs, \(N(\tau )=| {{{\mathscr{C}}}}(\tau )|\), and \({t}_{ij}^{\,{\mbox{c}}\,}\) is the time of the first collision between cells i and j. In simulations, pairs are obtained based on direct contacts between cells. In experiments, only connections were retained for which the distance between the centers of mass was shorter than 3.5r, and the analysis was restricted to trajectories overlapping more than 240 min after initial proximity.

3D active foam model

The computational cell model, based on previous approaches25,60,61,62, portrays tissues as foam-like materials. Each cell i is modeled as a volume-conserving, pressurized “bubble”, characterized by a thin, viscous shell with plane viscosity η. This represents the cell’s acto-myosin cortex-membrane complex. Cells possess polarity \({\hat{{{{\bf{p}}}}}}_{i}\), which diffuses as \({{{\rm{d}}}}{\hat{{{{\bf{p}}}}}}_{i}=\sqrt{2{D}_{r}}\,{{{\rm{d}}}}{{{{\bf{W}}}}}_{t,i}\times {\hat{{{{\bf{p}}}}}}_{i}\), with persistence time τp = 1/Dr and standard Wiener process Wt To model active cell migration, an outward migration pressure is exerted on the cell surface as \({p}_{a,i}={p}_{a}({\hat{{{{\bf{x}}}}}}_{r,i}\cdot {\hat{{{{\bf{p}}}}}}_{i}){S}_{c,i}/{S}_{i}\), where pa is the active pressure, \({\hat{{{{\bf{x}}}}}}_{r,i}=({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{i}-{{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{c,i})/| | {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{i}-{{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{c,i}| |\) is the relative position with respect to the cell center xc,i, Sc,i is the total cell-cell contact area and Si is the total cell area. To preserve internal force balance, the internal reaction traction \({{{{\bf{T}}}}}_{c,i}=-\frac{1}{{S}_{c,i}}{\oint }_{{S}_{i}}{p}_{a,i}{{{\rm{d}}}}{{{{\bf{S}}}}}_{i}\) is applied on contacting surfaces, where we integrate over an oriented contact surface. Given plane tangent vectors \({\hat{{{{\bf{t}}}}}}_{1,i}\) and \({\hat{{{{\bf{t}}}}}}_{2,i}\), the resulting in-plane stress is σi = η ∇ ui + γsI, with in-plane velocity \({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{i}=[{{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{i}\cdot {\hat{{{{\bf{t}}}}}}_{1,i},{{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{i}\cdot {\hat{{{{\bf{t}}}}}}_{2,i}]\). Note that for the viscous stress, we have assumed irrotational Stokes flow. The net surface tension is

We define the cortical relaxation time τγ = γ/η, and the relative cell-cell tension is α = 1 − w/γ. The in-plane force balance for surface i in contact with surface j reads

with \(\tilde{A}={[{\hat{{{{\bf{t}}}}}}_{1},{\hat{{{{\bf{t}}}}}}_{2}]}^{T}\), medium damping c0, and cell-cell friction ξ, setting the hydrodynamic length-scale Lη = (η/ξ)1/2. The out-of-plane pressure balance is

with outward normal \(\hat{{{{\bf{n}}}}}\). The total pressure is pi = pK,i + pa,i + pc,i, with pK,i the bulk pressure for volume conservation and pc,i the normal contact pressure, which for overlap distance δij is \({p}_{c,i}=w/{h}_{0}-w{\delta }_{ij}/{h}_{0}^{2}\), with effective range of interaction h0. To simulate multicellular collections, a particle-based computational model is adopted where the cortex-membrane complex is represented by a triangulated surface mesh, with nodal positions serving as degrees of freedom. Details of the numerical discretization and computational implementation of this 3D foam model are provided in the Supplementary Note.

Parametric generation of virtual tissue spheroids

For each combination of cell mechanical properties (without motility), a library of 10 virtual tissue spheroids was generated. For this, we generated N spherical cells with radii from a Gamma distribution, uniformly distributed within a spherical volume of radius 2N1/3ri, with r = 8.88 μm as the reference. The cells were enclosed by a reflective sphere with radius 2N1/3r + 2r. The domain’s radius linearly decreased over time, τinit = 10τγN1/3, to allow relaxation. A centripetal force \({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{cp}(t)=-{F}_{cp}\exp (-5t/{\tau }_{{{{\rm{init}}}}}){{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{r}\) was applied to cells outside the final boundary for t ≤ τinit/5. Cells were then allowed to relax without compression for an additional τinit.

Simulation setup

To simulate fusion, two spheroids are initially positioned with minimal overlap. First, two sequential spheroids from the library are selected and centered with random orientations. They are then translated along the ex axis until their boundaries touch. The minimum translation required for geometric contact is computed; if it exceeds a critical threshold, the spheroids are moved further apart, and the process is repeated. If it is below the threshold, the spheroids are moved to achieve contact, and the iteration ends. Finally, the simulation is centered at the origin. For parameter combinations that resulted in numerical instability, we only retained results if at least 5 runs completed successfully; otherwise, the condition is reported as ‘failed to converge.’ All simulations were carried out in Python using the Mpacts particle-based simulation framework.

Scaling exponents of tissue fluidity

To quantify the empirical scaling exponents relating tissue fluidity to active cell mechanical properties, we define a dimensionless activity parameter \({{{{\mathscr{A}}}}}_{\pi }=\mathop{\prod }_{i=0}^{3}{\pi }_{i}^{{a}_{i}}\), where the dimensionless groups are chosen as π0 = par/γ, π1 = α, π2 = τp/τγ, and π3 = N (the number of cells per spheroid). The exponents ai are scaling coefficients, with a0 = 1 set by convention. To determine the exponents ai, we minimize the loss function:

where rs is Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, Y * is the standardized unique contact number, and \(\sigma \left({\Delta }_{{{{{\mathscr{A}}}}}_{\pi }}{Y}^{*}\right)\) is the standard deviation of successive differences in Y*, sorted by \({{{{\mathscr{A}}}}}_{\pi }({a}_{i})\). The coefficients ai were estimated using the differential evolution algorithm in SciPy57. We performed 10 independent random iterations and report the resulting mean and standard deviation.

Theoretical scaling of tissue fluidity

In our model, active cell protrusions are the primary drivers of topological transitions within the tissue. The theoretical rationale for the scaling of tissue fluidity with cell mechanical properties is based on an analogy with the classical micropipette aspiration experiment47. As cell polarity undergoes diffusion, random front protrusions extend under active pressure pa and retract due to cortical tension. We assume that surface effects are significant because of intercellular pores or due to a significant cell fraction being at the spheroid surface. Then, the protrusion restoring timescale is set by the relaxation time τγ = η/γ. The protrusion length La,γ can be modeled as an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process:

where Da represents the effective diffusivity of the cell front. For a persistent random process at long timescales \({D}_{a}\propto {v}_{a}^{2}{\tau }_{p}\), where va is the active front velocity. Assuming subdominant cell-cell friction (Lη ~ r), the active velocity va arises from the balance of active pressure pa and cortical viscosity η, giving va ∝ par2/η. This yields the characteristic length of a protrusion,

The effective radius of a protrusion is determined by the Young-Laplace law at the junction, governed by interfacial tension αγ, thus

The stability criterion for protrusion elongation \({L}_{a,\gamma }^{*}/{r}_{a,\alpha \gamma }^{*} > 1\) leads to an activity parameter that controls tissue fluidity \({{{{\mathscr{A}}}}}^{2}\propto {L}_{a,\gamma }^{*}/{r}_{a,\alpha \gamma }^{*}\). Substituting the characteristic scales yields:

This result aligns with the scaling observed empirically in simulations, with a critical active pressure to fluidize the tissue pa,crit ∝ α1/2. Note that, when surface effects are negligible, the relaxation time is ταγ = η/(αγ), and we predict that pa,crit ∝ α3/4.

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. For the high-throughput brightfield microscopy fusion experiments, large sample sizes were obtained. Aggregates that did not make contact (and thus could not fuse) were excluded from the analysis, as indicated in the source data. Spheroid triplets were also excluded. For the two-photon microscopy experiments, the sample size (n = 3) was determined by the time and resource requirements associated with these measurements. The simulations are fully reproducible using the provided Docker image available in the Zenodo repository (see Data Availability). The experiments were not randomized, and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Ethics declaration

The ethical committee for Human Medical Research (KU Leuven) approved all procedures, and patients’ informed consent forms were obtained (ML7861).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database under accession code 13883906. This repository contains the raw microscopy data, processed datasets, simulation software and scripts, analysis tools, and metadata required to reproduce the results presented in this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The source code for the simulations presented in this study is publicly available on GitLab63. To ensure full reproducibility, the complete computational environment, including all dependencies and solver backend, is provided through a publicly accessible Docker container of the Mpacts software, along with a Singularity image and the simulation scripts used to generate the reported results, archived and documented in the Zenodo repository. The Mpacts backend is free to use under a non-open-source license; it can be accessed without restriction, but is provided without warranty. Documentation for the solver and usage instructions are available in the associated GitLab records.

References

Moroni, L. et al. Biofabrication strategies for 3d in vitro models and regenerative medicine. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 21–37 (2018).

Nunes, A. S., Barros, A. S., Costa, E. C., Moreira, A. F. & Correia, I. J. 3d tumor spheroids as in vitro models to mimic in vivo human solid tumors resistance to therapeutic drugs. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 116, 206–226 (2019).

Nilsson Hall, G. et al. Developmentally engineered callus organoid bioassemblies exhibit predictive in vivo long bone healing. Adv. Sci. 7, 1902295 (2020).

Hall, G. N. et al. Patterned, organoid-based cartilaginous implants exhibit zone specific functionality forming osteochondral-like tissues in vivo. Biomaterials 273, 120820 (2021).

Burdis, R. et al. Spatial patterning of phenotypically distinct microtissues to engineer osteochondral grafts for biological joint resurfacing. Biomaterials 289, 121750 (2022).

Mironov, V. et al. Organ printing: tissue spheroids as building blocks. Biomaterials 30, 2164–2174 (2009).

Kim, S.-j, Kim, E. M., Yamamoto, M., Park, H. & Shin, H. Engineering multi-cellular spheroids for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 9, 2000608 (2020).

Boot, R. C., Koenderink, G. H. & Boukany, P. E. Spheroid mechanics and implications for cell invasion. Adv. Phys.: X 6, 1978316 (2021).

Frenkel, J. Viscous flow of crystalline bodies under the action of surface tension. J. Phys. (USS R.) 9, 385 (1945).

McCune, M., Shafiee, A., Forgacs, G. & Kosztin, I. Predictive modeling of post-bioprinting structure formation. Soft Matter 10, 1790–1800 (2014).

Oriola, D. et al. Arrested coalescence of multicellular aggregates. Soft Matter 18, 3771–3780 (2022).

Kosheleva, N. V. et al. Cell spheroid fusion: beyond the liquid drops model. Sci. Rep. 10, 12614 (2020).

Ongenae, S., Cuvelier, M., Vangheel, J., Ramon, H. & Smeets, B. Activity-induced fluidization and arrested coalescence in fusion of cellular aggregates. Front. Phys. 9, 649821 (2021).

Ben Amar, M., Nassoy, P. & LeGoff, L. Physics of growing biological tissues: the complex cross-talk between cell activity, growth and resistance. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180070 (2019).

Grosser, S. et al. Cell and nucleus shape as an indicator of tissue fluidity in carcinoma. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011033 (2021).

Bi, D., Yang, X., Marchetti, M. C. & Manning, M. L. Motility-driven glass and jamming transitions in biological tissues. Phys. Rev. X 6, 021011 (2016).

Oswald, L., Grosser, S., Smith, D. M. & Käs, J. A. Jamming transitions in cancer. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50, 483001 (2017).

Mongera, A. et al. A fluid-to-solid jamming transition underlies vertebrate body axis elongation. Nature 561, 401–405 (2018).

Ilina, O. et al. Cell–cell adhesion and 3d matrix confinement determine jamming transitions in breast cancer invasion. Nat. cell Biol. 22, 1103–1115 (2020).

Kang, W. et al. A novel jamming phase diagram links tumor invasion to non-equilibrium phase separation.iScience 24, 103252 (2021).

Petridou, N. I., Corominas-Murtra, B., Heisenberg, C.-P. & Hannezo, E. Rigidity percolation uncovers a structural basis for embryonic tissue phase transitions. Cell 184, 1914–1928 (2021).

Hannezo, E. & Heisenberg, C.-P. Rigidity transitions in development and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 32, 433–444 (2022).

Guevorkian, K., Colbert, M.-J., Durth, M., Dufour, S. & Brochard-Wyart, F. Aspiration of biological viscoelastic drops. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 218101 (2010).

Bi, D., Lopez, J., Schwarz, J. M. & Manning, M. L. A density-independent rigidity transition in biological tissues. Nat. Phys. 11, 1074–1079 (2015).

Kim, S., Pochitaloff, M., Stooke-Vaughan, G. A. & Campàs, O. Embryonic tissues as active foams. Nat. Phys. 17, 859–866 (2021).

Brown, P. J., Green, J. E. F., Binder, B. J. & Osborne, J. M. A rigid body framework for multicellular modeling. Nat. Comput. Sci. 1, 754–766 (2021).

Vetter, R., Runser, S. V. & Iber, D. Polyhoop: Soft particle and tissue dynamics with topological transitions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 299, 109128 (2024).

Ichbiah, S., Delbary, F., McDougall, A., Dumollard, R. & Turlier, H. Embryo mechanics cartography: inference of 3d force atlases from fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Methods 20, 1989–1999 (2023).

Vanslambrouck, M. et al. Image-based force inference by biomechanical simulation. PLOS Comput. Biol. 20, e1012629 (2024).

Duchamp de Lageneste, O. et al. Periosteum contains skeletal stem cells with high bone regenerative potential controlled by periostin. Nat. Commun. 9, 773 (2018).

Yamamoto, T. et al. Modulation of microenvironment for controlling the fate of periodontal ligament cells: the role of rho/rock signaling and cytoskeletal dynamics. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 12, 369–378 (2018).

Smeets, B. et al. Compaction dynamics during progenitor cell self-assembly reveal granular mechanics. Matter 2, 1283–1295 (2020).

Freyria, A.-M. & Mallein-Gerin, F. Chondrocytes or adult stem cells for cartilage repair: the indisputable role of growth factors. Injury 43, 259–265 (2012).

Mendes, L. et al. Advancing osteochondral tissue engineering: bone morphogenetic protein, transforming growth factor, and fibroblast growth factor signaling drive ordered differentiation of periosteal cells resulting in stable cartilage and bone formation in vivo. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 9, 1–13 (2018).

Holzinger, A. Jasplakinolide: an actin-specific reagent that promotes actin polymerization.Methods Mol. Biol. 586, 71–87 (2010).

Beaune, G., Sinkkonen, L., Gonzalez-Rodriguez, D., Timonen, J. V. & Brochard-Wyart, F. Fusion dynamics of hybrid cell–microparticle aggregates: a jelly pearl model. Langmuir 38, 5296–5306 (2022).

Douezan, S. et al. Spreading dynamics and wetting transition of cellular aggregates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 108, 7315–7320 (2011).

David, R. et al. Tissue cohesion and the mechanics of cell rearrangement. Development 141, 3672–3682 (2014).

Cuvelier, M., Pešek, J., Papantoniou, I., Ramon, H. & Smeets, B. Distribution and propagation of mechanical stress in simulated structurally heterogeneous tissue spheroids. Soft Matter 17, 6603–6615 (2021).

Méhes, E. et al. 3d cell segregation geometry and dynamics are governed by tissue surface tension regulation. Commun. Biol. 6, 817 (2023).

Pawlizak, S. et al. Testing the differential adhesion hypothesis across the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. N. J. Phys. 17, 083049 (2015).

Park, S. et al. Directional migration of mesenchymal stem cells under an sdf-1α gradient on a microfluidic device. PLoS ONE 12, e0184595 (2017).

Maître, J.-L. et al. Adhesion functions in cell sorting by mechanically coupling the cortices of adhering cells. Science 338, 253–256 (2012).

Marchetti, M. C. et al. Hydrodynamics of soft active matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 1143 (2013).

Weeks, E. R. & Weitz, D. Properties of cage rearrangements observed near the colloidal glass transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 095704 (2002).

Merkel, M. & Manning, M. L. A geometrically controlled rigidity transition in a model for confluent 3d tissues. N. J. Phys. 20, 022002 (2018).

Hochmuth, R. M. Micropipette aspiration of living cells. J. Biomech. 33, 15–22 (2000).

Schwarz, U. S. & Safran, S. A. Physics of adherent cells. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 1327 (2013).

Olsen, T. et al. Manipulation of cellular spheroid composition and the effects on vascular tissue fusion. Acta Biomater. 13, 188–198 (2015).

Lindberg, G. C. et al. Probing multicellular tissue fusion of cocultured spheroids-a 3D-bioassembly model. Adv. Sci. 8, 2103320 (2021).

Rago, A. P., Dean, D. M. & Morgan, J. R. Controlling cell position in complex heterotypic 3d microtissues by tissue fusion. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 102, 1231–1241 (2009).

Livoti, C. M. & Morgan, J. R. Self-assembly and tissue fusion of toroid-shaped minimal building units. Tissue Eng. part A 16, 2051–2061 (2010).

Chiang, M., Hopkins, A., Loewe, B., Marchetti, M. C. & Marenduzzo, D. Intercellular friction and motility drive orientational order in cell monolayers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 121, e2319310121 (2024).

Arslan, F. N., Eckert, J., Schmidt, T. & Heisenberg, C.-P. Holding it together: when cadherin meets cadherin. Biophys. J. 120, 4182–4192 (2021).

Chaudhuri, O., Cooper-White, J., Janmey, P. A., Mooney, D. J. & Shenoy, V. B. Effects of extracellular matrix viscoelasticity on cellular behaviour. Nature 584, 535–546 (2020).

Van der Walt, S. et al. scikit-image: image processing in Python. PeerJ 2, e453 (2014).

Virtanen, P. et al. Scipy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Preibisch, S., Saalfeld, S., Schindelin, J. & Tomancak, P. Software for bead-based registration of selective plane illumination microscopy data. Nat. Methods 7, 418–419 (2010).

Fukai, Y. T. & Kawaguchi, K. Laptrack: linear assignment particle tracking with tunable metrics. Bioinformatics 39, btac799 (2023).

Misra, M., Audoly, B., Kevrekidis, I. G. & Shvartsman, S. Y. Shape transformations of epithelial shells. Biophys. J. 110, 1670–1678 (2016).

Cuvelier, M. et al. Stability of asymmetric cell division: A deformable cell model of cytokinesis applied to c. elegans. Biophys. J. 122, 1858–1867 (2023).

Runser, S., Vetter, R. & Iber, D. Simucell3d: three-dimensional simulation of tissue mechanics with cell polarization. Nat. Comput. Sci. 4, 299–309 (2024).

Ongenae, S., Vangheel, J., Pesek, J., Belpaire, T. & Smeets, B. Mpacts: active foam dynamics of tissue spheroid fusion. https://gitlab.kuleuven.be/mebios-particulate/publications/mpacts-active-foam-dynamics-of-tissue-spheroid-fusion (2025).

Acknowledgments

This work is part of Prometheus, the KU Leuven R&D Division for Skeletal Tissue Engineering. Images were recorded on a Zeiss LSM 780 - SP Mai Tai HP DS (Cell and Tissue Imaging Cluster, CIC), supported by Hercules AKUL/11/37, KU Leuven/BOF D9549, TRK/25/001 and FWO G.0929.15 (to P.V.B.). This work was further supported by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO), grants G042425N (Cartibot; to I.P. and B.S.), 11D9923N (to J.V.) and 12Z6118N (to B.S.), and by the Internal Funds KU Leuven, grant numbers C24M/22/058 (to I.P.) and C14/18/055 (to B.S.). H.S. acknowledges support from the MSCA4Ukraine fellowship (AvH ID: 101101923). This project has received funding through the MSCA4Ukraine initiative, funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the MSCA4Ukraine Consortium as a whole, nor any individual member institutions, can be held responsible for them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.O. designed and implemented the model, performed the simulations, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript. H.S. prepared samples and performed microscopy experiments. T.B. analyzed microscopy data and contributed to writing the manuscript. J.V. implemented the model and contributed to writing the manuscript. T.M. performed microscopy experiments and analyzed the microscopy data. P.V.B. supervised the microscopy experiments. I.P. conceptualized the research, wrote the manuscript, provided resources, and supervised the project. B.S. conceptualized the research, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript (original draft and revisions), provided resources, and supervised the project. All authors contributed to the discussion of results and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alessandro Mongera and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ongenae, S., Svitina, H., Belpaire, T.E.R. et al. Active foam dynamics of tissue spheroid fusion. Nat Commun 16, 10467 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65463-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65463-y