Abstract

Comprehensive knowledge of drug targets, their binding efficacy, and the subsequent activated cellular pathways is critical for determining therapeutic efficacy, elucidating mechanisms of action, and identifying potential side effects. However, acquiring this information in living cells remains challenging using routine proteomics methods. In this study, we propose an approach, the Solvent-Induced partial Cellular Fixation Approach (SICFA), to assess protein stability and drug interactions in living cells. By combining SICFA with quantitative proteomics, we can quantify stability for approximately 5600 proteins within the intracellular proteome. SICFA demonstrates high sensitivity in detecting drug-induced stability changes in target proteins and downstream effector proteins. Time-resolved SICFA allows the tracking of drug-induced molecular events over time, revealing the early impact of 5-Fluorouracil on RNA post-transcriptional modifications and ribosome biogenesis. Unlike traditional proteomics, SICFA offers enhanced sensitivity in detecting early biochemical events, providing critical insights into drug-target interactions and the sequence of drug-induced pathway alterations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurate identification of drug targets and their downstream effects is critical for understanding mechanisms of action and optimizing therapeutic outcomes1,2,3,4,5,6. Traditional methods, such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR)7, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)8, and fluorescence polarization (FP)9, rely on purified protein assays. While effective for studying direct target binding, they fail to replicate the complex physiological conditions of living cells. Advances in proteomic methods, such as Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA)10 and Thermal Proteome Profiling (TPP)11, have revolutionized the study of drug-target interactions by enabling high-throughput analyses across the proteome. TPP identifies drug targets by measuring protein stability shifts induced by small molecules, using thermal denaturation to detect shifts in melting temperature (ΔTm), and has been widely used12. Building on thermal denaturation principles, subsequent techniques like Proteome Integral Solubility Alteration (PISA)13 and isoThermal Shift Assay (iTSA)14 have further improved throughput and sensitivity. PISA estimates the area under thermal melting curves (Sm) by pooling soluble fractions from multiple temperatures, while iTSA measures solubility differences at a single temperature, offering a 10-fold increase in throughput compared to TPP. Despite their utility in cell lysates or live cells10, these thermal-based methods face limitations: they fail to detect targets that are heat-resistant or have no measurable solubility shift upon ligand binding during thermal treatment.

Beyond thermal denaturation, alternative methods using chemical denaturants (e.g., guanidine hydrochloride15, organic solvents16,17, ions18, acids19 have been developed to probe protein-ligand interactions. Solvent-induced precipitation (SIP)16 and solvent proteome profiling (SPP)17 are based on the principle that drug-binding proteins are more resistant to solvent-induced precipitation. SIP primarily quantifies the soluble proteins after treatment with a single solvent concentration, while SPP combines tandem mass tags (TMT) to generate complete protein melting curves across multiple solvent concentrations, both of which have become important tools for identifying protein-ligand interactions20,21,22,23. Only ion-based methods have been demonstrated to be applicable to intact cells18, whereas other denaturation methods are limited to cell lysates. In cell lysates, the disruption of cellular compartments and loss of protein-protein interactions may lead to false negative and false positive identifications. Moreover, lysate-based approaches primarily identify direct drug targets but fail to capture the full complexity of intracellular drug effects. To address these limitations, alternative methods that directly operate in living cells are preferred. Live-cell methods can preserve cellular integrity, providing insights into drug permeability, subcellular distribution, and downstream pathway effects. Bridging the gap between lysate-based methods and live-cell complexity would provide a more accurate understanding of pharmacological mechanisms and clinical relevance.

In this study, we introduce the solvent-induced partial cellular fixation approach (SICFA), a highly sensitive, label-free proteomics approach specifically designed to operate directly in living cells. Unlike lysate-based methods such as SIP or SPP, SICFA exploits the permeability of organic solvents and solvent-induced denaturation of intracellular proteins to enable in situ protein stability measurements while maintaining cellular integrity. Our results demonstrate that SICFA has the ability to detect both direct targets and stability shifts of downstream effector proteins with high sensitivity. The IsoSolvent Dose-Response SICFA (ISDR-SICFA) workflow quantifies the drug binding potency to intracellular targets and its effect on downstream effector proteins. For example, in the study of kinase inhibitors, both the EC50 values of CDK kinases and their substrate protein RB1 were determined simultaneously. In several drug studies, SICFA has shown strong complementary to TPP, broadening the scope of target identification. Furthermore, SICFA’s ability to track time-resolved drug effects provides unique insights into the temporal sequence of intracellular events induced by 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). After 4 h of 5-FU treatment, SICFA quantified the stability changes of several RNA post-transcriptional modification enzymes and validated these results through RNA modification level measurements. These findings reveal the early impact of 5-FU on RNA post-transcriptional modifications and ribosome biogenesis, underscoring SICFA’s sensitivity in detecting early biochemical events that are often overlooked by traditional proteomics methods. By bridging the gap between drug-target interactions and downstream effects, SICFA holds promise for providing valuable insights into drug mechanisms, making it a powerful tool for advancing proteomics-driven drug discovery.

Results

Partial fixation of proteins in living cells allows the proteome-wide assessment of cellular protein stability

Fixation is the critical initial step for preserving cellular structures, maintaining their lifelike appearance for cell imaging. The fixatives, including organic solvent-based fixatives directly alter the hydration layer of proteins by preferentially binding to the protein surface, displacing water molecules, and thereby inducing denaturation and aggregation. We hypothesized that proteins in different cellular states exhibit varying tolerance to fixative-induced denaturation and aggregation. Building on this principle, we propose a method termed solvent-induced partial cellular fixation approach (SICFA) to assess protein stability across the proteome in living cells. Unlike traditional fixation, SICFA uses gradient concentrations of organic solvent-based fixatives to progressively disrupt protein conformations, enabling the mapping of protein stability by analyzing soluble protein fractions after partial denaturation and aggregation.

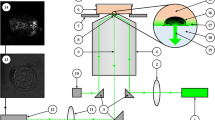

We optimized the conditions for partial cell fixation (Supplementary Note 1) and selected a mixture of organic solvents, specifically acetone, ethanol, and acetic acid (1:1:0.2%, v/v/v)16 as the fixative for SICFA experiments. To confirm the possibility of using SICFA to measure cellular protein stability on a proteome-wide scale, K562 cells were treated with fixative at 10 concentrations (0–25%) for 10 min. After adding 0.4% NP-40, cells were lysed by three freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen. Following high-speed centrifugation, equal volumes of soluble protein fractions were subjected to trypsin digestion and quantified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (Fig. 1a). Using 0% fixative as reference, a denaturation heatmap spanning ~6800 proteins was generated (Fig. 1b), revealing broad variability in fixative-induced denaturation sensitivity. Nonlinear fitting of normalized protein intensities across fixative concentrations yielded 6515 denaturation curves, each parameterized by slope (denaturation rate), half-effect concentration (unchained concentration, CU), plateau (extent of denaturation), and goodness of fit (R2). Applying quality criteria (valid slope, R2 > 0.8, plateau < 0.3) resulted in robust CU curve fits for 5577–5638 proteins across three replicates, covering ~82% of the K562 proteome (Fig. 1c). CU values ranged from 1% to 21%, with a median of 9.72% (Fig. 1d). CU values showed strong correlation among three biological replicates (Fig. 1e, R > 0.93). These data indicate that SICFA can reproducibly assign CU values to approximately 82% of proteins in cells.

a Workflow for Solvent-Induced partial Cellular Fixation Approach (SICFA). Cells are treated with increasing concentrations of fixative, followed by high-speed centrifugation and protein extraction. Protein stability is assessed using SDS-PAGE or LC-MS/MS. b Heatmap showing the relative abundance of all quantified proteins in replicate 1 at various fixative concentrations compared to 0%. Proteins are ordered by their CU values (indicating the fixative concentration at which the protein is equally distributed between folded and unfolded states). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. c Number of proteins quantified in each replicate and those with well-fitted denaturation curves (R2 > 0.8 and plateau < 0.3). d Distribution of CU values across three technical replicates, showing a median CU of 9.72%. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. e Pearson correlation coefficient of CU values between three repeated experiments (R > 0.93). f Boxplot of the proportion of amino acid (AA) residues in secondary structures (helices, IDRs, sheets, turns) in proteins, grouped by CU value (low, middle, high, unfit). The proteins were sorted according to the CU values, and the top 20% (n = 977 proteins), middle 20% (n = 977 proteins), and bottom 20% (n = 977 proteins) of the proteins were taken as the high, middle, and low protein groups in the box plot. All proteins without a determined CU value were classified as the unfit group (n = 701 proteins). The center line indicates the median, the box represents the interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles), and the whiskers extend to the range of the data. Significant (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Wilcoxon test with Benjamini–Hochberg correction, two-sided) between groups are indicated by asterisks. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. g Representative fixative-induced denaturation curves for MTFR1L and CYB5R3, shown for three replicates. The protein structure was visualized using data from AlphaFoldDB (MTFR1L: AF-Q9H019-F1-v4) and PDB (CYB5R3: 7thg).

To explore structural and thermodynamic correlates of CU, we stratified proteins into four groups—high, median, low, and undetermined CU—and analyzed stability-related features. Proteins with high CU had a greater proportion of β-sheets and turns, while those with low CU showed more intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) (Fig. 1f). MTFR1L (CU: 3.41%) and CYB5R3 (CU: 19.68%) exemplify these secondary structure patterns (Fig. 1g). Thermodynamically, CU tends to increase with the increase in activation Gibbs energy of unfolding (Supplementary Fig. 1a), suggesting that proteins with higher CU values tend to have higher energetic barriers to denaturation. Concurrently, CU is inversely associated with apparent partition energy, entropy of formation, radius of gyration of side chain, residue volume, and side chain hydropathy corrected for solvation (Supplementary Fig. 1b–f). These trends support the use of CU as a robust metric of protein stability. Proteins without a determined CU (not meeting quality criteria) exhibited a broad distribution in abundance and a wide range of subcellular localizations (including exosomes, cytoplasm, mitochondria, organelles, and nucleus) (Supplementary Fig. 1g, h, Supplementary Note 2). These proteins also displayed a wide range of unfolding energies, with median values that sometimes exceeded those of high CU proteins, suggesting that some proteins possess superior intrinsic stability against SICFA-induced denaturation.

Together, these analyses confirm that SICFA reliably quantifies protein stability landscapes in living cells and that CU values reflect structural and energetic stability across the proteome.

SICFA enables the detection of drug-induced protein stability shifts in living cells

We subsequently investigated whether SICFA could effectively measure stability shifts in target proteins induced by drug binding within living cells. We reason that ligand binding induces conformational changes, leading to the stabilization of proteins and thereby resistance to fixative-induced aggregation. To test the feasibility of this method, raltitrexed, a specific inhibitor of thymidylate synthase (TYMS), was selected as a model drug. Jurkat cells were incubated with control or raltitrexed (1 µM) for 30 min, and then a single or a series of concentrations of fixative were added to induce partial denaturation and aggregation of intracellular proteins. After cell lysis, soluble proteins were extracted and quantitatively analyzed by western blotting or liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to reveal drug-induced protein stability shifts (Fig. 2a). Western blotting results showed that at 10% and 12% fixative concentrations, the soluble TYMS content in the drug-treated group was markedly higher than in the control (Fig. 2b). This suggests that raltitrexed binding increases the resistance of TYMS to fixative-induced aggregation.

a Schematic overview of the experimental workflow. Cells are treated with either vehicle (control) or ligand (drug) and divided into aliquots. Each aliquot is subjected to solvent-induced fixation at low concentrations of a fixative solution. After partial fixation, cells were lysed, and the lysate was centrifuged to separate the soluble fractions from the precipitate. The supernatant containing soluble proteins was collected for downstream analysis. Protein abundances were measured via immunoblotting for target verification or LC-MS/MS-based quantitative proteomics for target identification. This approach evaluates stability shifts of drug targets and downstream effector proteins within cells following drug treatment. b Western blot analysis validating the stabilization of TYMS by Raltitrexed in Jurkat cells at various fixative concentrations, with Tubulin as a loading control (n = 2 biological replicates). c Volcano plot illustrating the identification of raltitrexed targets using SICFA. The dashed horizontal line represents a −log10(p value) of 4.0. Known targets are highlighted in red. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. d Volcano plot showing target recognition by SICFA for dasatinib. The dashed horizontal line represents a −log10(p value) of 3.5. Known targets (red) and potential targets (green) are highlighted. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. e Volcano plot showing the targets of MTX (20 μM, 30 min incubation in cell lysate) in the SIP experiment. Known target is highlighted. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. f Volcano plot showing the targets of MTX (1 μM, 30 min incubation in live cells) in the SICFA experiment. Known target (red) and potential targets (green) are highlighted. c–f p values from two-sided empirical Bayes t tests without adjustment, n = 5 cell replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. g Schematic representation of metabolic pathways influenced by MTX, highlighting interactions with target proteins TYMS and DHFR.

To achieve target identification, we aim to combine SICFA with quantitative proteomics analysis. Similar to iTSA14 method, we propose a workflow to detect drug- and control-induced protein stability (also known as solubility) shifts (ΔY, Fig. 2a) using a single concentration of fixative. This simplified workflow not only avoids the loss of information caused by poor curve fitting in traditional strategies but also significantly enhances throughput. Additionally, this workflow can be integrated with label-free quantification (LFQ) data-independent acquisition (DIA) methods, allowing for flexible increases in the number of replicates24 or expansion of the experimental design. Specifically, cells treated with raltitrexed or a control were incubated with 10% fixative for 10 min (five biological replicates). After cell lysis, soluble proteins were collected, and the digested peptides were quantitatively analyzed by LC-MS/MS in DIA mode. A total of 10 samples from five biological replicates were generated, requiring only 16.7 h of instrument time. After searching with Spectronaut software, the quantified proteins between the two groups were analyzed using the empirical Bayes t-test, and the protein with the lowest p value was determined as the target protein. In a single SICFA experiment, the number of protein identifications and the overall intensity range of ten samples in the drug group and control group were consistent across five replicates (Supplementary Fig. 2a), and a high correlation (r > 0.98) of the quantitation between samples was observed (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Above results indicate that SICFA experiments are highly reproducible. TYMS was identified as the leading candidate target in the pool of 5,534 proteins, with no other significant candidate targets (−log10(p value) ≥ 4.0) (Fig. 2c). When ranking the −log10(p value) of all quantified peptides, it is notable that 12 of the top 13 peptides are from the TYMS protein (Supplementary Fig. 2c). These findings demonstrate that SICFA is capable of accurately identifying the target protein of raltitrexed in cells with high specificity. The results of the trypan blue staining experiment and microscope images further supported the view that the cell membrane remained largely intact after treatment with 10% fixative (Supplementary Fig. 2d–f).

To further validate SICFA, we extended this workflow to the multi-target compound dasatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor25. After dasatinib treatment (1 μM, 30 min), we quantified 8 known targets (n = 5094) of dasatinib (the major target BCR-ABL was not quantified in our MS analysis due to low abundance). Among these, four known targets (MAPK14, YES1, MAP3K20, LYN) exhibited significant stability changes (−log10(p value) > 3.5, Fig. 2d). In cell lysate study using the kinobeads approach26, 47 proteins (including 11 known targets) showed a more than 50% reduction in binding at 1 µM dasatinib, including BCR-ABL, LYN, YES1 and RIPK2. This discrepancy may be attributed to kinobeads’ extensive coverage of kinases and its complete contact with cell lysates. In the SICFA experiment, dasatinib not only stabilized its direct target LYN but also reduced the stability of LYN’s interacting partner, CDKN1C (Fig. 2d). This could be explained that dasatinib’s binding to LYN affects the interaction between LYN and CDKN1C, resulting in decreased stability of CDKN1C. This suggests that SICFA can identify direct drug targets as well as interacting proteins via binding-induced stability shifts.

SICFA, as a method for measuring intracellular protein stability, is intended to monitor drug targets and their induced downstream effector proteins. We compared the target profiles of methotrexate (MTX) determined by the SIP and SICFA methods. MTX, a competitive inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), blocks the conversion of dihydrofolate (DHF) to tetrahydrofolate (THF), disrupting THF-dependent pathways27. K562 cell lysates or living cells were incubated with 20 µM or 2 µM MTX, respectively, for 30 min, followed by SIP and SICFA analysis. In both experiments, DHFR stability was significantly increased, confirming its direct interaction with MTX (Fig. 2e, f). After entering the cell, MTX is metabolized into its polyglutamate form (MTX-PG), which binds to TYMS and affects DNA synthesis. In the SIP experiment using cell lysates, TYMS stability remained unchanged (Fig. 2e). However, in live cells, metabolized MTX-PG binds to TYMS, resulting in increased TYMS stability in the SICFA results (Fig. 2f). Methionine synthase (MTR) stability was reduced in SICFA experiments (log2FC = −0.38), likely due to decreased 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-CH3-THF) levels following the inhibition of THF synthesis (Fig. 2g). SICFA also detected increased stability of C-1-tetrahydrofolate synthase (MTHFD1), reflecting a rapid cellular response to disrupted THF metabolism. Unlike cell lysate-based experiments, SICFA in living cells not only identified direct MTX targets but also revealed downstream effectors of MTX treatment. These findings offer valuable insights into the mechanisms of drug action in complex cellular environments.

Dose dependent experiments coupled with SICFA allow determination of the drug’s binding potency in living cells

Evaluating a drug’s binding potency to its targets in living cells is essential for understanding its efficacy. To determine the binding potency of drugs under physiological conditions, we developed a workflow called IsoSolvent Dose-Response SICFA (ISDR-SICFA), which evaluates drug binding potency by measuring protein stability shifts across a range of drug concentrations in living cells. In this study, ISDR-SICFA was applied to determine the binding potency of staurosporine (STS), an ATP-competitive kinase inhibitor. K562 cells were treated with STS at seven different concentrations (0–10 µM) for 15 min and then subjected to SICFA assay (Fig. 3a). Dose-response curves for 5087 proteins, including 197 kinases, were fitted to calculate EC50 values for each protein. To identify key candidate targets, we screened for dose-response curves with R2 values ≥ 0.8, plateau values ≥ 1.3 for increased stability or ≤0.7 for decreased stability, and a −log10(p value) ≥ 2.3 at 10 µM STS (Fig. 3b). This process yielded 118 candidate targets with EC50 values under 10 µM, including 59 ATP-binding proteins (Fig. 3c). A broad range of pEC50 values was observed among the candidate targets, highlighting STS’s diverse interactions (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 3a).

a Schematic representation of the ISDR-SICFA workflow, which assesses drug binding potency by measuring protein stability shifts across various drug concentrations in living cells. K562 cells were treated with staurosporine (STS) at concentrations ranging from 0 to 10 μM for 15 min. Soluble proteins were extracted following SICFA treatment, digested, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. b Volcano plot of ISDR-SICFA analysis in K562 cells treated with 10 μM STS. Kinases, ATP-binding proteins, and other proteins are indicated by red, purple, and gray dots, respectively. The horizontal dotted line indicates a −log10(p value) threshold of 2.3. The p values from two-sided empirical Bayes t tests without adjustment, n = 5 cell replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. c Circular bar plot showing the pEC50 values of candidate targets. Bars represent candidate proteins, categorized into kinases, ATP-binding proteins, and others. Kinase annotations are from Kinhub. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. d Correlation between −log10(p value) and pEC50 values of candidate targets identified by ISDR-SICFA. The p values from two-sided empirical Bayes t tests without adjustment, n = 5 cell replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. e Dose-response curve for the non-denatured fraction of PRKCA with increasing concentrations of STS. The EC50 value was calculated to be 160 nM. f Summary of the number of kinase targets and other targets identified in the living cell dataset and lysate dataset. g Enrichment analysis of 118 candidate targets identified by ISDR-SICFA, showing Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes and KEGG pathways. The statistical significance of each pathway and the number of genes involved are represented using the −log10 p values (one-sided Fisher’s exact test, no adjustment) and the size of the circles, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. h Heatmap showing the dose-dependent effects of STS on RB1, CDK2, CDK5, and CDK9 in live cells. Color intensity represents relative protein intensity after transformation. i Dose-response curve for the non-denatured fraction of RB1 with increasing STS concentrations. The EC50 value was calculated to be 557 nM. j Schematic representation of the STS mechanism of action on the RB1-E2F complex. STS inhibits CDK, leading to dephosphorylation of RB1 and formation of a complex with E2F, thereby affecting cell cycle progression.

We focused on the known STS target Protein Kinase C (PRKC) family28. In ISDR-SICFA, the EC50 of PRKCA was 160 nM (Fig. 3e). EC50 values for other PRKC family members were also determined, including PRKCB (624 nM), PRKCD (153 nM), PRKCI (3875 nM), and PRKCQ (25.5 nM) (Fig. 3c). To investigate the potential differences between ISDR-SICFA and lysate-based methods, we conducted STS dose-response experiments (0–40 µM) in K562 cell lysates, ensuring that all other procedures and data analyses were consistent with those in the ISDR-SICFA experiments. A total of 49 candidate targets with EC50 values below 40 µM were identified (Supplementary Fig. 3b), of which 46 were kinases, representing 94% of the total target pool (Fig. 3f), which was higher than the in-cell results (33%), possibly suggesting that SICFA captured the information of downstream effector proteins.

Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the ISDR-SICFA results (Fig. 3g) identified processes such as peptidyl-serine/threonine phosphorylation, protein autophosphorylation, and apoptosis, along with pathways including MAPK, FoxO, and GnRH signaling. Further analysis of the non-kinase targets in the ISDR-SICFA results revealed that 44 of them could be mapped to protein-protein interaction networks with ATP-binding proteins or kinases (Supplementary Fig. 3c). This suggests that perturbation of kinase or ATP-binding protein activity by STS in living cells affects the stability of both kinases and their interacting proteins, such as the interaction between MAPK14 and MKNK129.

Notably, ISDR-SICFA data revealed a negative correlation between the stability shifts of substrate RB1 (retinoblastoma-related protein) and CDKs (cyclin-dependent kinases), with similar pEC50 values (Fig. 3h, i). In contrast, no significant changes in RB1 stability were observed in the cell lysate data (Supplementary Fig. 3d). RB1’s interaction with E2F transcription factors and its ability to inhibit transcription are regulated by phosphorylation catalyzed by CDKs30,31. This could be explained by the inhibition of CDKs activity by STS, which may prevent RB1 phosphorylation (Fig. 3j). ISDR-SICFA successfully elucidated the phosphorylation-dependent stability changes of the CDK kinase substrate RB1, which reflects the inhibition of kinase activity. These findings emphasize the distinct effects features of the two methods: lysate-based experiments reveal targets that directly interact with the drug, while ISDR-SICFA captures information not only on direct drug-target interactions but also on downstream effector proteins.

SICFA complementary to TPP for target protein identification

SICFA uses fixative, while TPP uses heating to unfold and denature proteins within cells to probe the stability of proteins. Since the denaturing principles are different, we speculate that SICFA and TPP methods have preferences for different proteins. We systematically investigated the differences in protein stability determined by SICFA and TPP. K562 cells were treated with two gradient denaturant conditions: 10 fixative concentrations and 10 temperatures, each with 2 technical replicates, to generate denaturation curves. Each method quantified approximately 6500 proteins, with around 80% of proteins showing high-quality denaturation curves in both replicates (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The results showed that 4597 proteins (80.1%) exhibited high-quality denaturation curves in both SICFA and TPP, with 492 proteins uniquely well-fitted by SICFA and 301 proteins uniquely well-fitted by TPP (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Overall, the CU (SICFA) and Tm (TPP) showed a moderate correlation (R = 0.631), which was lower than the intra-method correlation (R = 0.928, 0.903, Supplementary Fig. 4c–e). In addition, distinct denaturation patterns between the two methods were observed for individual proteins (Supplementary Fig. 4f). These results suggest that SICFA and TPP have some difference on denaturing proteins in living cells and therefore have the potential to complement each other in identifying target proteins.

To evaluate the range of target proteins identified by SICFA and the latest advancements in TPP methods (PISA13 and iTSA14), we employed the ATP-competitive kinase inhibitor staurosporine (STS) as a model compound. To enable fair comparison, we experimentally reproduced two widely used PISA protocols: PISA3 (53–59 °C)24 and PISA10 (48–58 °C)13,32,33, as the temperature range has been shown to influence PISA performance34. In parallel, we reproduced the iTSA experiment (named iTSA) and downloaded the STS data from the same study (named Ball_iTSA). K562 cells were treated with either STS or DMSO, and all experiments were performed under identical conditions with five biological replicates per method.

We used empirical Bayes t-test (eBayes) and two-sided unpaired t-tests (equal variance) to assess the significance between STS and DMSO groups. After filtering proteins for |log2FC| > 0.3 and ranking by −log10(p value). Target identification performance was evaluated at a 50% true positive rate (TPR) cutoff for two target categories: kinases and ATP-binding proteins (Fig. 4a). In most data, eBayes identified more kinase and ATP-binding protein targets than t-tests, so eBayes results were used in subsequent analyses. Although SICFA identified more ATP-binding protein targets than other TPP methods (59 vs. 25–36, Fig. 4a), results from a single drug and comparison standard are insufficient to evaluate the sensitivity of different methods. We further compared the kinase targets identified by each method. SICFA, iTSA, PISA3, and PISA10 each identified around 30 kinase targets, while Ball_iTSA identified fewer (21), likely due to differences in quantification methods and MS. Overlap analysis revealed that SICFA yielded highest number of unique kinase target identifications (13) (Fig. 4b), accounting for 24% of the total number of results from all TPP/PISA methods. When SICFA is combined with any TPP/PISA method, the number of identified kinase targets increases by more than 63% (Fig. 4c). The above results indicate that SICFA is highly complementary to thermal treated methods in target protein identification as the different denaturing methods are used. We further compared the fold changes (log2FC) and significance (−log10(p value)) of known PRKC family targets across methods. Compared to the TPP/PISA method, SICFA yielded the largest fold changes (log2FC) for several PRKC targets (Fig. 4d), making it easier to detect stability shifts in some target proteins and helping to enhance confidence.

a The bar plot shows the comparison of the number of ATP-binding protein targets (yellow) and kinase targets (blue) identified by different methods. Among these, iTSA, PISA3 (53–59 °C), and PISA10 (48–58 °C) were data that were reproduced in our laboratory based on published literature, while Ball_iTSA was based on STS data downloaded from the literature. The plot shows the data of two statistical methods: eBayes (dark) and t-test (light). b Upset Plot shows the overlap of kinase targets identified by different methods. The figure shows the size of the intersection and the number of overlapping kinase targets of SICFA, iTSA, PISA3, and PISA10. c The bar plot shows the number of kinase targets identified after combining SICFA with any of the TPP-based methods. d Stability fold change (log2FC) of STS targets (PRKCA, PRKCB, PRKCD, PRKCQ) identified by SICFA, iTSA, PISA3, and PISA10. Each data point represents a single replicate, and asterisks are used to indicate −log10 (p value) > 2. e Fold changes in stability (log2FC) of SNS-032 targets (CDK2, CDK7, CDK9, RB1) identified by SICFA and PISA10. Data points represent single replicates, and asterisks indicate −log10 (p value) > 2. f Fold changes in stability (log2FC) of Panobinostat targets (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, HDAC4, HDAC6, HDAC8) identified by SICFA and PISA10. Data points represent single replicates, and asterisks indicate −log10 (p value) > 2. d–f the p values from two-sided empirical Bayes t tests without adjustment, n = 5 cell replicates.

To further assess the complementary of these two types of methods, we tested SICFA and PISA10 with two additional compounds: SNS-032 (CDK2/7/9 inhibitor) and Panobinostat (HDAC inhibitor). In the SICFA results, CDK2, CDK9, and substrate RB1 all exhibited large stability shifts (log2FC > 0.5; Fig. 4e). In contrast, the fold change for CDK2 in the PISA10 experiment was difficult to detect (~0.1; Fig. 4e). Upon Panobinostat treatment, three known targets—HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC6—showed consistent stabilization across both methods, while HDAC3 exhibited opposite trends. Notably, HDAC8 was uniquely identified by SICFA (Fig. 4f). These results highlight the complementary nature of SICFA and TPP/PISA in target identification and suggest that combining both approaches could improve confidence and coverage in drug target discovery.

Time-resolved SICFA unveils the temporal sequence of intracellular biochemical pathways induced by 5-FU

Long-term drug treatment induces substantial cellular alterations, complicating the extraction of relevant data from complex datasets. We propose integrating SICFA with time-resolved experiments to elucidate the sequence of drug impacts on biochemical pathways. 5-FU is metabolized intracellularly to active forms, including 5-fluorodeoxyuridine monophosphate (5-FdUMP), which inhibits TYMS, disrupts DNA synthesis. It can also be converted into 5-fluorouridine triphosphate (5-FUTP) and 5-fluorodeoxyuridine triphosphate (5-FdUTP), which are incorporated into RNA and DNA, leading to cancer cell dysfunction and death35 (Fig. 5a). To investigate the activation process and temporal regulation of intracellular biochemical pathways by 5-FU, K562 cells were incubated with 50 µM 5-FU or DMSO for 30 min, 4 h, 12 h, and 24 h. Cells were divided into two groups: one treated with 10% fixative for SICFA analysis (stability group), and the other treated with 8 M guanidine hydrochloride for complete protein quantification analysis (abundance group) (Fig. 5b). The differences in protein stability (n = 5491) and abundance (n = 7005) at the four time points were calculated (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 5a). After filtering (|log2FC| > 0.5, −log10(p value) > 4.0), 459 proteins with altered stability and 312 with altered abundance were identified (Fig. 5d). 232 proteins showed stability changes independent of protein expression, indicating that 5-FU directly impacts protein stability (Fig. 5d).

a Schematic representation of the metabolic pathways of 5-FU and their impact on DNA and RNA damage. Proteins with significant changes in stability and abundance are highlighted in red. b Experimental workflow of the protein stability and protein abundance analysis. K562 cells were treated with 5-FU or DMSO at different time points (30 min, 4 h, 12 h, and 24 h), followed by cell lysis, protein extraction, digestion, and LC-MS/MS analysis. c Volcano plots showing changes in protein stability (SICFA) after 5-FU treatment in K562 cells at different time points (30 min, 4 h, 12 h, 24 h). The p values from two-sided empirical Bayes t tests without adjustment, with n = 4 cell replicates. Known targets are marked in red, and potential targets are shown in green. The dashed line corresponds to a significance threshold of −log10(p value) = 4. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. d Venn diagram showing overlap between proteins with significant changes in stability (SICFA) and those with altered abundance. e Line chart showing the number of proteins with significant changes in stability and abundance over time. Cellular responses are categorized into four stages: (i) molecular initiating events, (ii) early events, (iii) intermediate events, and (iv) outcome events. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. f Heatmaps showing bioinformatics enrichment analysis of biological processes associated with proteins with significant changes in stability (SIC) and abundance (Abu) at different time points, highlighting the time-resolved effects of 5-FU on cellular biochemical pathways. Colors indicate p-values (one-sided Fisher’s exact test, no adjustment), with white cells indicating a lack of enrichment of the term in the corresponding gene list.

SICFA detected 1, 15, 136, and 307 proteins with significantly altered stability across the four time points, while quantitative proteomics detected much lower numbers, 0, 2, 43, and 267, of proteins with significantly changed in abundance (Fig. 5e). Principal component analysis (PCA) results showed that at earlier time points, the control and drug groups showed significant differences in protein stability, while protein abundance showed no difference (Supplementary Fig. 5b). These results suggest that protein stability is a more sensitive and responsive indicator of 5-FU’s downstream effects compared to protein abundance. After a brief 30-min incubation with 5-FU, TYMS stability increased significantly (log2FC: 2.11) without corresponding changes in protein abundance. This indicates that 5-FU underwent rapid metabolic conversion to 5-FdUMP, which specifically bound to TYMS, inhibiting its activity. This highlights SICFA’s ability to capture the molecular initiating event (MIE) of 5-FU treatment. At 4 h, 15 proteins exhibited stability changes that persisted over time, marking these as early events (Fig. 5e). These proteins are involved in RNA modification, translation regulation, mRNA/tRNA processing, and ribosome assembly (Fig. 5f). Previous research indicates that 5-FU accumulates in RNA at levels substantially higher than in DNA36, supporting the observation that the early cellular response to 5-FU, particularly its impact on RNA pathways. After 12 h of 5-FU treatment, the number of proteins with altered stability increased to 136, suggesting the occurrence of intermediate events following the initial drug-target binding and early events. The SICFA results indicated that the early cellular response was sustained and intensified, particularly in processes related to ribosome biosynthesis, RNA processing and modification, and translation regulation. Additionally, significant enrichment was observed in pathways such as DNA replication, p53-mediated signal transduction, and pyrimidine biosynthesis (Fig. 5f). The incorporation of 5-FU likely caused DNA damage, which may have activated the p53 pathway, leading to cell cycle arrest and ultimately apoptosis37. Over a 24-h period, the effects of 5-FU expanded to broader outcome events affecting energy production (oxidative phosphorylation), protein transport, mitochondrial organization, and the cell cycle. Stability changes were detected in CHEK1, CDK1, CDK2, and cyclins CCNA2 and CCNB1, indicating DNA damage response and potential progression to apoptosis. The transcriptional coactivator CREBBP also showed altered stability, further promoting apoptosis by regulating p53 transcription. A protein-protein interaction network revealed functional modules related to mitochondrial respiration, endoplasmic reticulum stress, RNA processing, and transcriptional regulation (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c). It is likely that 5-FU not only induces apoptosis via direct DNA damage but also promotes cell death by influencing mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum functions. Although these predicted results require further experimental validation, a stability shift assay in living cells could provide key information for hypothesis generation for further biological studies.

By analyzing data across multiple time points, SICFA effectively elucidated the time-resolved cellular responses to 5-FU. This encompasses the molecular initiation events that facilitate the binding of the drug to the target, the early events that influence RNA pathways, the intermediate events that involve ribosome assembly and DNA damage, and ultimately the outcome events, including cell cycle arrest, mitochondrial damage, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and apoptosis. Time-resolved SICFA provides a comprehensive framework for determining the sequential impact of 5-FU on cellular biochemical pathways, facilitating a deeper understanding of drug mechanisms that may enhance therapeutic strategies and reduce drug resistance.

SICFA reveals that the early biochemical pathways of 5-FU are focused on post-transcriptional RNA modifications

Understanding early molecular events is crucial for elucidating drug mechanisms, clarifying drug-target interactions, and optimizing therapeutic strategies. To evaluate the direct target binding and early biochemical effects of 5-FU, we focused on the stability changes of 15 proteins at the 4-h time point (Fig. 6a), which are involved in RNA modification, ribosome biogenesis, and rRNA processing (Fig. 6b). SICFA revealed the early stability shifts in proteins involved in small ribosomal subunit biogenesis, including RIOK2, BYSL, RRP12, NOB1, EMG1, LTV1, and FAM207A (Fig. 6a). Among these, EMG1 is responsible for the methylation of pseudouridine (Ψ) in 18S rRNA, a key step in the maturation of 18S rRNA38. These findings provide insights into how 5-FU inhibits rRNA maturation39 and the subsequent assembly of functional ribosomes40.

a Heatmap showing the stability and abundance change patterns (transformed log2FC) of 15 proteins in early response to 5-FU treatment. b Network depicting bioinformatics enrichment analysis for proteins with significant stability changes at 4 h. Gene nodes are colored by log2FC, and biological process node sizes represent the number of contained genes. c Bar charts showing the log2FC values for stability (SICFA) and abundance of pseudouridine synthases (PUS1, PUS3, PUS10, TRUB1, TRUB2) at different time points following 5-FU treatment. Chemical structures illustrate the conversion of uridine to pseudouridine catalyzed by the PUS family. d Bar chart depicting the log2FC values for stability and abundance of DUS3L (tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase) at different time points. The chemical structure shows the conversion of uridine to 5,6-dihydrouridine. e Bar charts showing the log2FC values for stability and abundance of TRMT2A and EMG1, which are involved in methylation modifications of uridine and pseudouridine, respectively, at different time points after 5-FU treatment. The chemical structures illustrate these methylation modifications. f Volcano plots showing the fold change (log2FC) and statistical significance (−log10(p value)) of tRNA modifications after 5-FU treatment for 4 h (left) and 24 h (right), compared to the control group. The p values from two-sided empirical Bayes t tests without adjustment, with n = 3 cell replicates. Significantly downregulated tRNA modifications are marked in orange, upregulated ones in blue, and unchanged modifications in gray. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Interestingly, the stability of several key enzymes involved in RNA post-transcriptional modifications, including pseudouridine synthases (PUS family members PUS1, PUS3, PUS10, TRUB1, TRUB2; Fig. 6c), dihydrouridine synthase (DUS3L; Fig. 6d), and RNA methyltransferases (TRMT2A, EMG1; Fig. 6e), significantly increased after 5-FU treatment and further enhanced with prolonged treatment (Fig. 6c–e). The stability shift patterns of TRMT2A and EMG1 were further confirmed by limited proteolysis (Supplementary Fig. 6d). It is hypothesized that the covalent complexes formed by 5-FU-tRNA with PUS41,42 and with TRMT2A43 alter the stability of these enzymes and affect their functions43,44. To further investigate whether the stability shifts of RNA post-transcriptional modification enzymes detected by SICFA reflect changes in enzyme function, we measured tRNA modification levels in 5-FU-treated cells (at 4 and 24 h) using LC-MS/MS. The experimental results showed that no significant changes in RNA modifications were observed at 4 h, but at 24 h, multiple modifications, including Ψ, ncm5U(5-carbamoylmethyluridine), hm5C(5-hydroxymethylcytidine), and m5U(5-methyluridine), were significantly downregulated (Fig. 6f). These results indicate that SICFA sensitively detects the effect of 5-FU on intracellular RNA post-transcriptional modifying enzymes at early stage (4 h), whereas changes in the corresponding post-transcriptional modification levels require a much longer period of time to accumulate (24 h) before they can be detected.

In summary, protein stability changes occur earlier than both post-transcriptional modifications and protein expression changes, and therefore can serve as a sensitive indicator for identifying early molecular events. The sensitive monitoring of protein stability by SICFA provides a distinctive perspective for understanding the early mechanisms of 5-FU and lays the theoretical foundation for the development of future anticancer therapies targeting RNA modifications.

Discussion

In this study, we developed and validated a method, termed SICFA (Solvent-Induced partial Cellular Fixation Approach), that enables the monitoring of drug-induced stability changes of target proteins and downstream effector proteins on a proteome-wide scale in live cells. Specifically, living cells are subjected to partial fixation to induce protein aggregation within the intracellular environment. Soluble proteins are subsequently collected and quantified to evaluate their stability, which is altered by interactions with drugs or other molecules. By integrating this partial fixation principle with immunoblotting and quantitative mass spectrometry, SICFA offers a powerful tool to measure the effects of drugs on the stability of individual proteins or the entire proteome. In experiments with raltitrexed, dasatinib, and MTX, SICFA accurately identified the known targets of these drugs while maintaining membrane integrity, demonstrating the method’s precision and robustness.

Unlike lysate-based methods such as SIP or SPP, SICFA provides a live-cell approach for drug-target identification. On the one hand, SICFA captures both the direct targets of a drug and the downstream effects induced by drug binding, offering insights into drug mechanisms. In contrast, lysate-based methods disrupt cellular signaling and structure, diluting endogenous factors and restricting stability changes to those directly involving the drug’s target. This distinction is supported by experimental data comparing MTX’s effects in live-cell and lysate-based settings. On the other hand, cell-based SICFA can identify the targets of prodrugs such as 5-FU, which must be metabolized into an active form within cells to exert their effects. Direct targets of 5-FU cannot be identified using lysate-based screening (Supplementary Fig. 7).

In contrast to TPP-based methods, SICFA uses organic solvents to induce protein denaturation within cells. Our data, as well as findings from the SIP16 and SPP17 methods, report that the two methods have complementary denaturation ranges. We conducted a parallel comparison of SICFA and TPP/PISA in identifying the targets of three different drugs. The combination of these two methods has been shown to increase the number of targets identified, with some targets being uniquely identifiable only by one of the methods. This suggests that SICFA and TPP/PISA are complementary in target identification, and the combined use of these methods could significantly improve target coverage.

Moreover, the streamlined workflow in SICFA increases throughput and allows for various experimental designs, such as ISDR-SICFA combined with drug concentrations and time-resolved SICFA with different treatment durations. These designs enable quantitative determination of drug-target engagement potency and resolve the temporal sequence of drug-induced stability shifts across intracellular biochemical pathways. Such as the EC50 value of the CDK substrate protein RB1, which reflects a phosphorylation-dependent stability shift32. This may link inhibitor binding potency to kinase activity, offering important insights into the intracellular efficacy and mechanism of drug action. In a previous study, Liang et al.45 employed the IMPRINTS (Integrated Modulation of PRINTS)-CETSA method to investigate the mechanism of action of 5-FU in parental and resistant cells. However, a comprehensive analysis of the sequence of drug regulation of intracellular biochemical pathways has not been conducted. By integrating the time-resolved drug treatment experiments with SICFA, the intracellular molecular initiation, early, intermediate, and outcome events triggered by 5-FU were successfully distinguished. The time-resolved protein stability shifts indicate that 5-FU primarily affects RNA modifications, rather than being limited to its known mechanism of inhibiting DNA synthesis.

Compared to quantitative proteomics, protein stability data holds promise as a sensitive indicator of early biochemical effects induced by drugs. For example, SICFA results showed significant stability changes in several RNA modification enzymes at the 4-h time point. Furthermore, the decrease in pseudouridine and methylation levels in tRNA suggests that the stability changes measured by SICFA are linked to functional alterations in these enzymes. The early effects of 5-FU on RNA modifications may precede and influence subsequent cellular responses, thereby deepening our understanding of the early cellular effects of 5-FU.

In conclusion, SICFA provides a systematic framework for studying drug-target binding and downstream biochemical pathways in live cells. In addition to the workflow presented in this study, SICFA can also be integrated with stability curves or the PISA strategy, further enhancing its applicability across various research scenarios. Beyond drug target screening, SICFA can be expanded to distinguish different functional protein isoforms within cells. In addition, this method supports multiple detection methods, such as Western blot, MS-based proteomics, and high-throughput microplate fluorescence analysis, to facilitate large-scale drug screening. Future research will focus on extending SICFA to a broader range of ligands and cellular contexts, further enhancing its applications in drug discovery and other fields.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

IGEPAL (NP-40), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), protease inhibitor cocktail, formic acid (FA), tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), 2-chloroacetamide (CAA), ethanol, guanidine hydrochloride, urea, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) and 5-fluorodeoxyuridine monophosphate (5-FdUMP) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Raltitrexed, Methotrexate (MTX), Dasatinib, Staurosporine and 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) were purchased from Selleck (Houston, TX, USA). Acetone was purchased from DAMAO (Tianjin, China). Acetone was purchased from XiLONG SCIENTIFIC (Guangdong, China). Sequencing-grade modified trypsin was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Acetonitrile and methanol (HPLC grade) were from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Cell culture

K562(ATCC, No. CCL-243) and Jurkat(ATCC, No. TIB-152) cells were cultured in IMDM and RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, USA), respectively. Both media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA) and 1% streptomycin (Beyond, China). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Assessing intracellular protein stability using partial fixation

K562 cells (10 million) were washed three times with ice-cold PBS, resuspended in PBS containing 1% protease inhibitor cocktail, and divided into nine equal aliquots. A mixed solvent (acetone: ethanol: acetic acid, 1:1:0.2%, referred to as fixative) with increasing gradient concentrations (0%, 4%, 8%, 12%, 14%, 16%, 20%, 25%, and 30%) was added to each aliquot. Samples were equilibrated at 37 °C with continuous shaking at 1200 rpm for 10 min. After equilibration, 0.4% NP-40 was added to each sample. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for 3 min, thawed in a 37 °C water bath for 1 min, and then subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles to lyse the cells. Lysates were centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant containing soluble proteins was collected for BCA analysis.

For mass spectrometry analysis, cells were divided into 10 samples (three replicates per condition), treated with fixative concentrations of 0%, 3%, 6%, 8%, 10%, 12%, 14%, 17%, 21%, and 25%. The cell lysis and centrifugation steps were performed as described above. Equal volumes of supernatant (containing soluble proteins) from each sample were transferred to new 0.6 mL microtubes for mass spectrometry sample preparation and analysis.

Solvent-induced partial cellular fixation approach (SICFA) analysis

K562 cells were seeded at equal numbers into 12-well plates in complete growth medium and treated with raltitrexed (1 µM; 1% DMSO) or vehicle (1% DMSO) for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were then collected by centrifugation (320 × g, 3 min), washed three times with ice-cold PBS, and resuspended in PBS supplemented with 1% protease inhibitor cocktail.

For Western blot analysis, cells from raltitrexed or vehicle groups were divided into seven aliquots (approximately 2 million cells). Varying concentrations of fixative (0%, 6%, 8%, 10%, 12%, 14%, and 16%) were added to each aliquot. The samples were equilibrated at 37 °C with shaking at 1200 rpm for 10 min. After equilibration, 0.4% NP-40 was added to each sample. The samples were then subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles using liquid nitrogen. After lysis, the samples were centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and equal volumes of supernatant were collected for western blot analysis.

For MS analysis, raltitrexed- and vehicle-treated cells were exposed to fixative at a final concentration of 10% and equilibrated at 37 °C with shaking (1200 rpm, 10 min). After equilibration, the cells were lysed, and the supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, as described above, for subsequent MS analysis.

ISDR-SICFA analysis

K562 cells were incubated with seven different concentrations of Staurosporine (10, 1, 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001, and 0 μM, including a DMSO control) for 15 min. After incubation, the cells were harvested and washed three times with ice-cold PBS. Five biological replicates were performed for each concentration. All samples were fixed with 10% fixative at 37 °C for 10 min, then treated with 0.4% NP-40. Samples were then subjected to freeze-thaw cycles and centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Equal volumes of supernatant from each sample were collected for mass spectrometry analysis.

Comparison between SICFA and TPP

K562 cells were washed with ice-cold PBS were divided into two aliquots for generating SICFA and TPP denaturation curves. For SICFA, 10 aliquots (two biological replicates) were treated with varying concentrations of fixative (0%, 3%, 6%, 8%, 10%, 12%, 14%, 17%, 21%, 25%), equilibrated at 37 °C with shaking at 1200 rpm for 10 min. For TPP, 10 aliquots (two biological replicates) were heated in a thermal cycler at a series of temperatures (37 °C, 41 °C, 45 °C, 48 °C, 51 °C, 54 °C, 57 °C, 61 °C, 65 °C, 69 °C) for 3 min, followed by cooling at 25 °C for 3 min. After treatment, all samples were supplemented with NP-40 to a final concentration of 0.4%, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles to lyse the cells. Samples were then centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and equal volumes of supernatant were transferred to new 0.6 mL microtubes for mass spectrometry sample preparation and analysis.

Time-resolved SICFA analysis

K562 cells were cultured and treated with 50 µM 5-FU or an equivalent volume of DMSO for 30 min, 4 h, 12 h, and 24 h. After treatment, cells were harvested, washed three times with ice-cold PBS, and resuspended in PBS containing 1% protease inhibitor cocktail. The cells were then equally divided into two groups for protein stability analysis (SICFA group) and protein quantification (Abundance group). For the SICFA group, cells treated with 5-FU or DMSO at each time point were fixed with 10% fixative at 37 °C with shaking at 1200 rpm for 10 min, supplemented with 0.4% NP-40, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for 3 min. The cells were lysed using three freeze-thaw cycles. For the Abundance group, three volumes of 8 M guanidine hydrochloride were added to cells treated with 5-FU or DMSO at each time point, and the samples were sonicated using the Bioruptor (high power mode, 30 s on/30 s off) for 20 cycles to ensure complete cell disruption. All lysed samples from both groups were centrifuged at 4 °C, 21,000 × g for 15 min. Equal volumes of the supernatants were collected and transferred to new microtubes for mass spectrometry preparation and analysis.

Solvent-induced protein precipitation (SIP) analysis

K562 cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed three times with cold PBS. The cells were resuspended in PBS buffer containing 1% protease inhibitor mixture (without EDTA). The cell suspension was then frozen in liquid nitrogen for 3 min, followed by thawing in a 37 °C water bath. This freezing-thawing process was repeated three times. The samples were centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant containing the protein was collected. The protein samples were divided into two groups: one was treated with DMSO, and the other was incubated with drugs (MTX: 20 μM) for 30 min. Each group was further divided into five equal portions, to which the same organic solvent as the fixative used in this study was added to a final concentration of 10%. The samples were shaken at 1200 rpm for 10 min at 37 °C to induce protein denaturation. After denaturation, the samples were centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected for subsequent mass spectrometry (MS) analysis.

In the experiment to identify the affinity of staurosporine, K562 cell lysate was incubated with 0, 0.01, 0.1, 0.8, 5, 20, and 40 μM for 30 min, respectively. Each drug concentration group contained 5 replicate samples, and the rest of the steps were the same as the above MTX experimental process.

SDS-PAGE and western blotting

For SDS-PAGE analysis, protein samples were initially resolved on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, followed by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye. Western blot samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE separation and subsequently transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Immunoblotting was conducted using primary antibodies targeting TRMT2A, EMG1, GAPDH, and Tubulin (Proteintech, Wuhan, China), as well as TYMS (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Secondary goat anti-rabbit HRP-IgG antibodies (Proteintech, Wuhan, China) were employed following the manufacturer’s instructions.

LC-MS/MS sample preparation

The supernatant protein solution obtained from the previous experiment was mixed with 3 volumes of denaturation buffer (containing 8 M guanidine hydrochloride and 50 mM HEPES, pH 8.2) for denaturation. Protein disulfide bonds were then reduced by adding tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) and alkylated using 40 mM chloroacetamide (CAA). The mixture was heated at 95 °C for 5 min. After denaturation, each sample was transferred to a 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off filter unit (Vivacon® 500 from Sartorius Stedim Biotech) for buffer exchange, followed by washing with 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3). Trypsin (Promega) was added for overnight digestion. Peptides were collected from the filtrate and dried using a SpeedVac system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA).

LC-MS/MS analysis

Dried peptides were reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid (FA) and analyzed using an Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), equipped with a FAIMS interface and coupled to a micro-flow HPLC system (Dionex Ultra 3000, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The FAIMS parameters were set as follows: compensation voltage, −45 V; total carrier gas flow rate, 3.5 L/min. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% FA (A) and a mixture of 0.1% FA and 80% acetonitrile (ACN) (B).

Specifically, 10 μg of peptides were separated on a 1 mm × 15 cm ACQUITY UPLC Peptide CSH C18 column (130 Å, 1.7 μm; Waters), heated to 45 °C, with a flow rate of 50 μL/min. The following gradient was applied: 0–1 min, 4–6% B; 2–80 min, 6–32% B; 80–93 min, 32–45% B; 93–94 min, 45–90% B; 94–98 min, 90–90% B.

The Exploris 480 mass spectrometer acquired full MS scans at a resolution of 120,000 (at m/z = 200) over the m/z range of 350–1400. The automatic gain control (AGC) target was set to 3e6, with a maximum injection time (IT) of 45 ms. MS/MS scans were performed in data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode, with a resolution of 30,000 (at m/z = 200). A total of 24 DIA segments were acquired, covering the m/z range of 400-1000. The AGC target was set to 2e6 with an auto maximum IT. The normalized collision energy (NCE) was fixed at 30%.

Measurement of tRNA modification levels

For cell treatment, K562 cells were incubated with either 50 μM 5-FU or DMSO for 4 h or 24 h, respectively. After the incubation period, the cells were harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellet was then resuspended in Trizol reagent and stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA extraction.

For the RNA extraction, frozen samples stored at −80 °C were thawed on ice and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was carefully removed, and the pellet was treated with 100 μL of Buffer BCP (a chloroform substitute) and vigorously shaken for 15 s. The sample was incubated at room temperature for 5 min before centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube and mixed with an equal volume of isopropanol. After mixing, the sample was incubated at room temperature for 30–60 min. RNA precipitation was collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the RNA pellet was washed with 1 mL of pre-chilled 80% ethanol. After centrifugation at 7500 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was air-dried for 5–10 min until it became transparent. The RNA was resuspended in 20–50 μL of DEPC-treated water.

For tRNA isolation, the RNA sample was loaded onto a denaturing urea-PAGE gel and electrophoresed at 130 V and 10–15 mA per gel for 40–50 min. SYBR Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain was diluted and added to the gel, followed by a 2-min incubation at room temperature. Gel slices corresponding to mature tRNA fragments of 70–90 base pairs were excised. Then the gel was incubated with 300 μL of elution buffer at room temperature for 2 h to elute, and then centrifuge using a Spin-X centrifuge tube filter (Corning, 8162). The eluate was then mixed with 450 μL of anhydrous ethanol, 30 μL of sodium acetate, and 1 μL of glycogen, and precipitated on dry ice for 1 h. The sample was centrifuged, washed twice with 80% ethanol, air-dried, and resuspended in water before quantification.

RNA was analyzed following the previously established protocols46. Briefly, RNA samples were digested into nucleosides with 10 mU of nuclease P1, 10 mU of recombinant shrimp alkaline phosphatase, 1 mU of phosphodiesterase I, and 12 μU of phosphodiesterase II in 20 μL of digestion buffer (1 mM ZnCl2, 30 mM NaOAc, pH 7.5) overnight at room temperature. The nucleosides were purified using a porous graphitic carbon (PGC) solid-phase extraction (SPE) plate (Thermo Scientific). The samples were washed with 0.1% (v/v) TFA in water and eluted with 80% (v/v) ACN and 0.1% (v/v) TFA in water. The eluate was dried using CentriVap Centrifugal Concentrators (Labconco) and reconstituted in water for LC-MS/MS analysis.

The nucleosides were separated using a nanoAcquity UPLC M-Class System (Waters) coupled to a ZenoTOF 7600 mass spectrometer (SCIEX), with a Hypercarb Porous Graphitic Carbon HPLC column (1 mm × 100 mm, 3 μm, Thermo Scientific) at a constant flow rate of 50 μL/min. The gradient consisted of 0–2 min, 2% B; 2–20 min, 2–28% B; 20–29 min, 28–72% B; 29–30 min, 72–95% B; 30–34 min, 94% B; 34–35 min, 95–2% B; 35–40 min, 2% B. Ion source gases 1 and 2, as well as the curtain gas, were set to 20, 60, and 35 psi, respectively. Nucleosides were detected under SWATH positive mode, with MS1 spectra acquired over a mass range of m/z 200–1000 with a 0.2 s accumulation time. A total of 20 SWATH mass windows were used, with zenoSWATH mode on, and collision-induced fragmentation was performed with nitrogen gas using dynamic collision energy. Product ions were monitored from the m/z range of 100–1000 with a 18 ms accumulation time.

Cell membrane integrity assay

Cell membrane integrity was assessed in fixative-treated Jurkat cells using the trypan blue dye exclusion method. Cells were incubated with a gradient of fixative concentrations for 10 min, after which the reaction was terminated by 10-fold dilution with PBS. A 10 µL aliquot of each cell suspension was mixed with an equal volume of 0.4% (w/v) trypan blue dye solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The mixtures were then analyzed using an automated cell counter (CountessTM 3 FL, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells that excluded trypan blue were considered to have intact cell membranes, while trypan blue-stained cells were identified as having compromised membrane integrity.

Raw data analysis

Raw data were processed using the default parameters of the directDIA analysis module in Spectronaut (version 18.1). The Human UniProt FASTA database (updated on 2020-06, containing 20,350 non-redundant proteins) was used for protein identification, allowing up to two missed trypsin cleavages. The false discovery rate (FDR) was controlled at 1% at the protein group level. For protein quantification, the top three peptide ion intensities were used. Protein intensities across different technical replicates were normalized using a local normalization strategy.

Wiff files was converted to .mzXML format using MS Converter (v3.0.2), and nucleosides were identified using NuMoFinder (https://github.com/ChenfengZhao/NuMoFinder). The identified nucleosides were confirmed and quantified by integrating the peaks using Skyline (v23.1).

Except as noted, all statistical analyses in this work were performed using the limma package loaded in R (https://www.r-project.org) for two-sample empirical Bayesian tests.

Denaturation curve fitting

For data processing of SICFA denaturation curves, the specific process refers to the work of Savitski et al.11. Protein ratios were calculated using the protein intensity at the lowest concentration of fixative (0%) as a reference. The protein ratio showed an S-shaped trend as the fixative changes, and the fitted equation is:

In this equation, a represents the slope, b is the denaturation point, and plateau refers to the steady-state value. Each protein’s dataset was grouped by protein ID, and initial fitting parameters were set to a = −0.1, b = 8, and plateau = 0.01. Non-linear least squares (NLS) fitting was used to optimize the values of a, b, and plateau for each protein, minimizing the residual error between the fitted curve and the observed data. The goodness of fit was assessed using an R-squared value, which quantifies how well the model explains the variability in the data. The final optimized parameters and R-squared values for each protein were saved for further analysis.

For the data processing of TPP denaturation curves, we again followed the approach of Savitski et al.11. Here, protein ratios were calculated using the intensity at the lowest temperature (37 °C) as the reference. Similar to the SICFA curves, the protein ratios showed a sigmoidal trend as the temperature increased. The following equation was used for fitting:

In this case, a is the slope, b represents the melting point, and plateau denotes the steady-state value. The initial fitting parameters were set to a = −0.1, b = 42, and plateau = 0.01. NLS fitting was used to optimize these parameters for each protein, and the R-squared value was calculated to evaluate the model’s fit. The final fitted parameters and R-squared values were recorded for further analysis.

Calculation of pEC50 values from ISDR-SICFA or SIP experiments

First, the coefficient of variation (CV) of protein intensities across five replicates at each drug concentration was calculated, and proteins with CV > 1.0 were excluded. For the remaining proteins, the average intensity from four replicates with the lowest CV values was calculated. These average intensities were used to determine fold changes relative to the control at each drug concentration. Dose-response curves were fitted using a four-parameter logistic model (LL.4), and pEC50 values were determined for each protein. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to compare the estimated and original values, yielding the correlation (R2) between the protein dose-response curve and the sigmoid trend. Proteins with R2 ≥ 0.8 were retained for further analysis.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analysis methods of the data were detailed in the subsections above. All SICFA proteomic experiments were performed in ≥4 biological replicates. No statistical method was used to predetermine the sample size. All samples and cells were randomly allocated into experimental groups. The investigators were not blinded to sample identity, as the data were obtained through objective quantitative methods, which minimize the risk of subjective bias. Except as noted, all data were included in the analyses.

Bioinformatic analysis

Gene ontology (GO) cellular compartment analysis was performed on the DAVID platform (v.6.8, https://david.ncifcrf.gov/).

Protein-protein interactions were analyzed using the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/), which integrates known and predicted interactions. Interactions with a confidence score greater than 0.7 were considered significant. The resulting interaction network was visualized using Cytoscape (version 3.9.1).

Physicochemical properties of proteins were obtained from the AAindex database47,48. Secondary structure information for each amino acid residue was sourced from AlphaFold49.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry data generated in this study have been deposited in the PRIDE repository with accession code PXD057157. The protein structures used in this work were available via PDB ID 7THG and AlphafoldDB ID AF-Q9H019-F1. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes that support the findings of this study is available on Zenodo50 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17242086).

References

Baillie, T. A. Drug–protein adducts: past, present, and future. Med. Chem. Res. 29, 1093–1104 (2020).

Ali, E. S. et al. Recent advances and limitations of mTOR inhibitors in the treatment of cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 22, 284 (2022).

Druker, B. J. et al. Effects of a selective inhibitor of the Abl tyrosine kinase on the growth of Bcr–Abl positive cells. Nat. Med. 2, 561–566 (1996).

Robers, M. B. et al. Quantifying target occupancy of small molecules within living cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 89, 557–581 (2020).

Schenone, M., Dančík, V., Wagner, B. K. & Clemons, P. A. Target identification and mechanism of action in chemical biology and drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 232–240 (2013).

Mitchell, D. C. et al. A proteome-wide atlas of drug mechanism of action. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 845–857 (2023).

Acharya, B., Behera, A. & Behera, S. Optimizing drug discovery: surface plasmon resonance techniques and their multifaceted applications. Chem. Phys. Impact 8, 100414 (2024).

Velazquez-Campoy, A. & Freire, E. Isothermal titration calorimetry to determine association constants for high-affinity ligands. Nat. Protoc. 1, 186–191 (2006).

Nikolovska-Coleska, Z. et al. Development and optimization of a binding assay for the XIAP BIR3 domain using fluorescence polarization. Anal. Biochem. 332, 261–273 (2004).

Molina, D. M. et al. Monitoring drug target engagement in cells and tissues using the cellular thermal shift assay. Science 341, 84–87 (2013).

Savitski, M. M. et al. Tracking cancer drugs in living cells by thermal profiling of the proteome. Science 346, 1255784 (2014).

Mateus, A., Kurzawa, N., Perrin, J., Bergamini, G. & Savitski, M. M. Drug target identification in tissues by thermal proteome profiling. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 62, 465–482 (2022).

Gaetani, M. et al. Proteome integral solubility alteration: a high-throughput proteomics assay for target deconvolution. J. Proteome Res. 18, 4027–4037 (2019).

Ball, K. A. et al. An isothermal shift assay for proteome scale drug-target identification. Commun. Biol. 3, 75 (2020).

Meng, H., Ma, R. & Fitzgerald, M. C. Chemical denaturation and protein precipitation approach for discovery and quantitation of protein–drug interactions. Anal. Chem. 90, 9249–9255 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. Solvent-induced protein precipitation for drug target discovery on the proteomic Scale. Anal. Chem. 92, 1363–1371 (2020).

Van Vranken, J. G., Li, J., Mitchell, D. C., Navarrete-Perea, J. & Gygi, S. P. Assessing target engagement using proteome-wide solvent shift assays. eLife 10, e70784 (2021).

Beusch, C. M., Sabatier, P. & Zubarev, R. A. Ion-based proteome-integrated solubility alteration assays for systemwide profiling of protein–molecule interactions. Anal. Chem. 94, 7066–7074 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Highly effective identification of drug targets at the proteome level by pH-dependent protein precipitation. Chem. Sci. 13, 12403–12418 (2022).

Yu, C. et al. Solvent-induced proteome profiling for proteomic quantitation and target discovery of small molecular drugs. Proteomics 23, 2200281 (2023).

Bizzarri, L. et al. Studying target–engagement of anti-infectives by solvent-induced protein precipitation and quantitative mass spectrometry. ACS Infect. Dis. 10, 4087–4102 (2024).

Bravo, P. et al. Integral solvent-induced protein precipitation for target-engagement studies in Plasmodium falciparum. ACS Infect. Dis. 10, 4073–4086 (2024).

Yu, Z. et al. Characterization of a small-molecule inhibitor targeting NEMO/IKKβ to suppress colorectal cancer growth. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 71 (2022).

Batth, T. S. et al. Streamlined analysis of drug targets by proteome integral solubility alteration indicates organ-specific engagement. Nat. Commun. 15, 8923 (2024).

Carter, T. A. et al. Inhibition of drug-resistant mutants of ABL, KIT, and EGF receptor kinases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11011–11016 (2005).

Bantscheff, M. et al. Quantitative chemical proteomics reveals mechanisms of action of clinical ABL kinase inhibitors. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1035–1044 (2007).

Kremer, J. M. Toward a better understanding of methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 50, 1370–1382 (2004).

Tamaoki, T. et al. Staurosporine, a potent inhibitor of phospholipid/Ca++dependent protein kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 135, 397–402 (1986).

Huttlin, E. L. et al. The BioPlex network: a systematic exploration of the human interactome. Cell 162, 425–440 (2015).

Harbour, J. W., Luo, R. X., Santi, A. D., Postigo, A. A. & Dean, D. C. Cdk Phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells move through G1. Cell 98, 859–869 (1999).

Chellappan, S. P., Hiebert, S., Mudryj, M., Horowitz, J. M. & Nevins, J. R. The E2F transcription factor is a cellular target for the RB protein. Cell 65, 1053–1061 (1991).

Van Vranken, J. G. et al. Large-scale characterization of drug mechanism of action using proteome-wide thermal shift assays. eLife 13, RP95595 (2024).

Sabatier, P., Beusch, C. M., Meng, Z. & Zubarev, R. A. System-wide profiling by proteome integral solubility alteration assay of drug residence times for target characterization. Anal. Chem. 94, 15772–15780 (2022).

Li, J., Van Vranken, J. G., Paulo, J. A., Huttlin, E. L. & Gygi, S. P. Selection of heating temperatures improves the sensitivity of the proteome integral solubility alteration assay. J. Proteome Res. 19, 2159–2166 (2020).

Longley, D. B., Harkin, D. P. & Johnston, P. G. 5-Fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 330–338 (2003).

Pettersen, H. S. et al. UNG-initiated base excision repair is the major repair route for 5-fluorouracil in DNA, but 5-fluorouracil cytotoxicity depends mainly on RNA incorporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 8430–8444 (2011).

Adamsen, B. L., Kravik, K. L. & De Angelis, P. M. DNA damage signaling in response to 5-fluorouracil in three colorectal cancer cell lines with different mismatch repair and TP53 status. Int. J. Oncol. 39, 673–682 (2011).

Thomas, S. R., Keller, C. A., Szyk, A., Cannon, J. R. & LaRonde-LeBlanc, N. A. Structural insight into the functional mechanism of Nep1/Emg1 N1-specific pseudouridine methyltransferase in ribosome biogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 2445–2457 (2010).

Wilkinson, D. S., Tlsty, T. D. & Hanas, R. J. The inhibition of ribosomal RNA synthesis and maturation in novikoff hepatoma cells by 5-fluorouridine. Cancer Res. 35, 3014–3020 (1975).

Therizols, G. et al. Alteration of ribosome function upon 5-fluorouracil treatment favors cancer cell drug-tolerance. Nat. Commun. 13, 173 (2022).

Samuelsson, T. Interactions of transfer RNA pseudouridine synthases with RNAs substituted with fluorouracil. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 6139–6144 (1991).

Gu, X., Liu, Y. & Santi, D. V. The mechanism of pseudouridine synthase I as deduced from its interaction with 5-fluorouracil-tRNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14270–14275 (1999).

Hussain, S. On a new proposed mechanism of 5-fluorouracil-mediated cytotoxicity. Trends Cancer 6, 365–368 (2020).

Huang, L., Pookanjanatavip, M., Gu, X. & Santi, D. V. A conserved aspartate of tRNA pseudouridine synthase is essential for activity and a probable nucleophilic catalyst. Biochemistry 37, 344–351 (1998).