Abstract

Anion exchange membrane fuel cells are limited by the slow kinetics of the alkaline hydrogen oxidation reaction (HOR). Aided by density functional theory combined with fine-tuned machine learning interatomic potential, we establish a family of bimetallic catalysts with controlled surface atomic arrangements to identify the optimal catalysts for HOR. Our theoretical analysis successfully predicts the HOR activity rankings of these catalysts, consistent with the experimental results. RuIr exhibits the highest activity, followed by PtRu, AuIr, PtRh, PtIr, PtAu, RhIr, RuRh, AuRu, and AuRh. These trends correlate with the electron-accepting tendencies and the adsorption strengths of H2 and OH* on the catalysts. Among all candidates, RuIr emerges as the most active and durable bimetallic catalyst. Furthermore, operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy and electrochemical measurements reveal a strong synergistic effect of RuIr, where Ir exhibits superior electron-accepting tendency and strong H2 adsorption, while Ru demonstrates strong OH* adsorption, accelerating the alkaline HOR process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anion-exchange membrane fuel cells (AEMFCs) have received ever-increasing interest since they can achieve the direct conversion of chemical energy to electricity in alkaline electrolytes by hydrogen oxidation reaction (HOR) and oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) at the anode and cathode sides, respectively. However, HOR suffers from sluggish kinetics in alkaline solutions compared with acidic ones, which hinders the practical application of AEMFCs1,2,3. In alkaline solution, the HOR occurs via a Tafel−Volmer or Heyrovsky−Volmer mechanism: (1) Tafel step: H2 + 2* → 2Had; (2) Heyrovsky step: H2 + OH− + * → Had + H2O + e−; (3) Volmer step: Had + OH− → H2O + e− + *, where * is the surface site and Had represents the adsorbed hydrogen. The HOR mechanism is still elusive since the Had is believed to react either with OH− in the solution or with adsorbed hydroxyl (OHad; formed by OH− + * → OHad + e−) on the surface to form H2O4,5,6. The hydrogen binding energy (HBE) theory suggests adsorbed Had as a key reaction intermediate of HOR7,8,9,10. However, it is difficult to elucidate the whole reaction process comprehensively owing to the involvement of OH− in the Heyrovsky or Volmer step. The hydroxyl binding energy (OHBE) theory (or called bifunctional theory) emphasizes the cooperative adsorption of both Had and OHad on the active surface11,12,13,14. Computational and experimental studies have shown that the competitive adsorption and desorption between these intermediates critically influence catalytic performance. In particular, the electron-accepting capability of the catalyst surface has been identified as a dominant factor in facilitating the Volmer step, thereby governing the overall HOR performance. Despite its physical relevance, this concept has rarely been employed in previous HOR studies15,16.

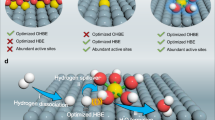

Several strategies have been developed for promoting HOR activity by manipulating atomic arrangements and coordination environments of the active centers17,18, controlling crystalline phases19,20,21,22, and alloying metals11,23,24,25,26,27. However, effectively addressing the challenge of competition between hydrogen and hydroxyl intermediates for access to active sites remains a significant hurdle. An ideal alkaline HOR electrocatalyst with a delicate balance between intermediates should possess three advantages: (1) The coexistence of two distinct types of active sites on the catalyst surface, enabling selective adsorption-desorption behavior for hydrogen and hydroxyl intermediates, which prevents mutual competition between these processes; (2) A uniform distribution of these two types of active sites across the surface, facilitating a synergistic effect in optimizing the binding energies of intermediates; and (3) High resistance to intermediate poisoning, as such poisoning could impede the accessibility of active sites and potentially reduce the durability. Given these considerations, bimetallic electrocatalysts with two different types of active sites are regarded as promising candidates for efficient HOR catalysis. However, such a bimetallic electrocatalyst possessing all three advantages to show the most active and durable toward alkaline HOR seems to be contradictory to one another in many recent studies. It is not very surprising because many internal (e.g., atomic arrangement and crystallinity) and external (e.g., electrolyte and pH) factors, which are intricately intertwined, can affect the HOR kinetics.

In this work, we developed a machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP) that was fine-tuned using our own density functional theory (DFT) data, enabling accurate and efficient evaluation of complex adsorption configurations, such as H2 and OH*, on various bimetallic surfaces. Compared to conventional DFT calculations, this MLIP significantly accelerates the screening process while maintaining high predictive accuracy for adsorption energetics relevant to HOR. To further advance catalyst screening, we introduce the relative Fermi level position as a new electronic descriptor for HOR activity. This parameter reflects the electron-accepting tendency of a surface and correlates with the Volmer step kinetics in alkaline HOR. Although physically meaningful, this descriptor has rarely been applied in previous HOR studies15,16. Crucially, our study also addresses a major limitation in prior research, namely, the inconsistency in catalyst morphology and testing conditions, which often complicates meaningful comparisons. Even when the same compositions are reported, structural variations such as spherical nanoparticles, nanowires, and porous or irregular morphologies introduce significant variability in performance, obscuring the intrinsic role of composition28,29,30,31,32. In contrast, our platform maintains both compositional and structural consistency across catalysts, enabling a reliable evaluation of bimetallic systems and the identification of combinations with optimal HOR performance. Among these, RuIr emerges as a highly effective pair. Operando synchrotron X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and electrochemical analyses reveal a pronounced synergistic effect on the RuIr surface. This synergy facilitates balanced interactions with both hydrogen and hydroxyl intermediates, thereby significantly enhancing alkaline HOR kinetics.

Results

DFT-aided design and prediction for HOR catalysts

In this study, we focus on the preparation of atomic-mixing bimetallic alloys made of commonly used catalytically active Ru, Rh, Ir, Pt, and Au as mixed elements to form 10 different bimetallic catalysts enclosed by the same square atomic arrangements of face-centered cubic (FCC) {100} facets because of their unique electronic structures and superior catalytic performances for HOR. Most importantly, we fix all internal and external factors that can disturb the HOR except the elemental composition of the bimetallic catalysts. In addition, the constituent elements of these bimetallic catalysts are in equimolar ratios. This will allow us to acquire an optimized composition of bimetallic catalysts with high HOR activity and durability while gaining a comprehensive understanding of their catalytic mechanisms. Although other crystal facets, such as the {111} facet of FCC metals (e.g., Pd and Pt) and the {101} facet of hexagonal close-packed (HCP) metals (e.g., Ru), are also catalytically relevant, achieving well-controlled epitaxial growth on these surfaces remains experimentally challenging. For example, FCC metals like Pd often expose {111} facets, but atomic-layer deposition on these surfaces tends to shift from layer-by-layer to island growth due to their relatively low surface energy, resulting in rough or discontinuous shells (Supplementary Fig. S1). In the case of HCP metals like Ru, synthesizing nanocrystals that predominantly expose the prismatic {101} facet is particularly difficult, as they often form spherical particles or anisotropic morphologies with mixed facet exposure. Furthermore, the significant lattice mismatch between HCP-structured cores and FCC-structured bimetallic shells complicates epitaxial growth and limits atomic-level control over shell uniformity. Given these constraints, we selected the {100} facet of FCC-structured Pd nanocubes as a synthetically accessible and structurally uniform platform. This choice enables controlled epitaxial growth of ultrathin bimetallic shells with consistent square atomic arrangements, facilitating reliable comparison across the bimetallic catalyst series.

As discussed in the Introduction, the Volmer step, which is considered the rate-determining step for HOR33, depends primarily on two reactants: Had and OH- (or OHad), and involves electron transfers to the metal catalyst. Recognizing the importance of these factors, we commenced with DFT calculations on various monometallic catalyst surfaces. These surfaces were modeled on the symmetry of the Pd (001) surface to closely simulate the experimental conditions of epitaxial growth on Pd, incorporating metals such as Ir, Pt, Ru, Rh, and Au. We calculated the adsorption energy of H2 and OH* to assess the binding energies. Additionally, to understand the differences in electron transfer among metals, we analyzed the relative positions of the Fermi levels with respect to the vacuum level, which indicates the electron-accepting tendencies of the metal surfaces. With these factors evaluated on monometallic catalysts, we proceeded to explore synergistic effects and predict the HOR activity rankings for the various bimetallic combinations.

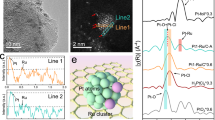

Figure 1a depicts the surface structure (slab model) of a monometallic Ir surface, which aligns with the symmetry of the Pd (001) surface. A 6-layer slab was selected in this work, as the surface energy converged and the difference is around 0.002 J/m2 beyond this thickness (Supplementary Table S1). Other monometallic surface structures are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S2. Figure 1a also demonstrates the variation in electrostatic potential across the Ir surface, necessary for computing the work function and band alignments. The electrostatic potentials for other monometallic surfaces are documented in Supplementary Fig. S3. Notably, the work functions of Ir and Pt are relatively high, at 5.59 eV and 5.77 eV, respectively, compared to those of Ru, Au, and Rh, which are 4.91 eV, 5.22 eV, and 5.09 eV, respectively. In exploring the adsorption of H2 and OH* on monometallic surfaces, multiple adsorption configurations, including vertical, horizontal, and inclined orientations with varying rotational angles and sites, were considered, as shown in Fig. 1b. Exhaustively evaluating all possible adsorption configurations using DFT would be computationally prohibitive. To address this challenge, we utilized a pre-trained machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP), CHGNet34, to enable rapid energy screening of various structures. However, typical pre-trained MLIPs are trained primarily on relaxed bulk structures, which can limit their accuracy when applied to surface adsorption systems. Therefore, we performed additional DFT calculations on representative adsorption configurations and used this dataset to fine-tune the pre-trained CHGNet model, creating system-specific MLIPs for each surface. The number of DFT data utilized for fine-tuning and the corresponding total energy calculations from both DFT and pre-trained CHGNet MLIP model are presented in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3, respectively, with details provided in the Methods section. Specifically, for the horizontal H2 adsorption on the Ir surface, the initial CHGNet-calculated (without fine-tuning) total energy was −932.967 eV, compared to the DFT-calculated energy of −920.692 eV. After fine-tuning with additional DFT data, the CHGNet model predicted an energy of −920.378 eV, significantly closer to the DFT value, while reducing computation time. Consequently, this fine-tuned MLIP was employed for rapid screening of various adsorption configurations of H2 and OH* on different monometallic surfaces, as illustrated for H2 on Ir in Fig. 1b and for other surfaces in Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5. The horizontal and inclined configurations exhibited lower energies than vertical adsorption, indicating their favorability. However, due to residual discrepancies between the MLIP and precise DFT calculations, configurations with lower CHGNet energies were selected for further accurate DFT evaluations. The configuration with the lowest DFT energy was ultimately chosen for detailed adsorption energy calculations. Supplementary Figs. S6 and S7 present the most energetically favorable structures for H2 and OH* adsorbed on monometallic surfaces. Notably, H2 molecules are well adsorbed and dissociated on Ir, Pt, Ru, and Rh surfaces. However, H2 does not adsorb well on Au surfaces in any configuration, corroborating previous studies that also reported poor adsorption of H2 on Au6,8.

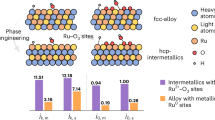

a Depiction of the optimized iridium (Ir) metal surface (slab model) simulating iridium grown on palladium (Pd) cubic seeds (\({{\mbox{Fm}}}\bar{3}{\mbox{m}}\)) and (001) surface. This panel includes the calculated electrostatic potential across the slab used to determine the work function (\(\phi={V}_{{vac}}-{E}_{F}\)), where \({V}_{{vac}}\) is the vacuum level, \({E}_{F}\) is the calculated Fermi level, and \({V}_{{avg}}\) is the average electrostatic potential across the slab. b Adsorption of H2 and OH* on metal surfaces, illustrating various molecule configurations and adsorption sites identified via the Delaunay triangulation algorithm. A pre-trained MLIP model (CHGNet) was fine-tuned with additional DFT calculations to estimate total energies and to rapidly screen configurations of adsorbates and adsorption sites. Lower energy structures were re-evaluated with precise DFT calculations to identify the most favorable adsorbate-adsorbent configurations. c Comparative analysis of the relative Fermi levels and adsorption energies of H2 and OH* on various metal surfaces, all conforming to Pd (001) symmetry. d Summary of the features of various metals and their bimetallic alloys based on DFT-calculated electron-giving tendencies and H2/OH* adsorption strengths. More negative Fermi levels and adsorption energies indicate stronger electron accepting and adsorption capabilities, respectively. Features of the superior metal in bimetallic catalysts were chosen to represent the combined properties. e Predicted HOR activity sequence derived from DFT calculations for single metals and bimetals, prioritizing electron acceptance followed by H2 and OH* adsorption strength.

Figure 1c provides a summarized comparison of aligned Fermi levels (EF) versus vacuum levels and adsorption energies (Ead) of H2 and OH* on five monometallic surfaces. Ir and Pt exhibit relatively lower Fermi levels at −5.59 eV and −5.77 eV, respectively, compared to Ru, Au, and Rh, indicating a stronger tendency to accept electrons. Conversely, Ru shows the highest EF at −4.91 eV, suggesting the least electron-accepting tendency among the investigated metals. In terms of H2 adsorption energy, Ir, Pt, and Ru demonstrate relatively negative values of −1.45 eV, −1.34 eV, and −1.37 eV, respectively, indicating stronger adsorption strengths compared to Au and Rh, which exhibit −0.01 eV and −1.13 eV, respectively. For OH* adsorption energy, Ru exhibits the most negative value at −0.67 eV, followed by Ir at −0.21 eV and Rh at −0.17 eV, highlighting the strongest OH* adsorption strength of Ru. Conversely, Au shows the most positive adsorption energy at +1.03 eV for OH*, indicating a repulsive interaction between OH* and the Au surface, consistent with previous studies35. We note that the presence of a Pd core may introduce strain effects, potentially altering the adsorption properties of the outer metal layer relative to its pure metal counterpart, as suggested in a recent study36. To evaluate this effect, we calculated the H adsorption energy on both pure metal surfaces and the corresponding outer metal layers supported on a Pd core (Supplementary Table S4). The results show that Ead values on the Pd-supported systems are slightly more negative, indicating a modest strain effect. However, the changes are relatively small (typically ~0.1 eV), and the overall adsorption trends are retained: Ir, Ru, and Pt maintain strong H adsorption, while Au remains weakly adsorbing. Therefore, although the Pd core introduces measurable strain, its influence does not alter the qualitative conclusions regarding H and OH adsorption behavior. In Fig. 1d, we introduce an activity diagram and map, derived from the three properties discussed in Fig. 1c, to illustrate the electron accepting tendencies, and H2 and OH* adsorption strengths. For a metallic HOR catalyst, higher values in these properties suggest increased HOR activity, as these are crucial for the Volmer step of HOR. When formulating bimetallic catalysts, we hypothesized that combining the advantageous properties of each metal would enhance overall performance. For instance, an RuIr bimetallic catalyst, combining strong H2 adsorption of Ir with effective OH* adsorption of Ru, would exhibit enhanced performance in both respects. This principle aided the construction of an activity prediction map for potential bimetallic combinations of Ir, Pt, Ru, Au, and Rh, also depicted in Fig. 1d.

Figure 1e outlines the proposed ranking of HOR activity (current density) for monometallic and bimetallic catalysts based on DFT calculations. The electron-accepting tendency is considered a dominant factor influencing HOR activity, as it drives the Volmer step. This conclusion is supported by experimental HOR activity measurements on monometallic surfaces (Ir, Pt, Ru, Rh, and Au), as shown later in Fig. 4 which show a strong correlation with their Fermi level positions, confirming the central role of electron-accepting ability. Ir and Pt, with their superior electron-accepting tendencies and strong H2 adsorption, are expected to exhibit higher HOR activity. Among Ru, Au, and Rh, Ru is expected to be more active due to its favorable properties in both H2 and OH* adsorption, whereas Rh shows poor OH* adsorption and Au lacks significant affinity for both H2 and OH*. Therefore, for monometallic catalysts, the ranking based on DFT-calculated properties for HOR performance is (Ir, Pt) > Ru > (Rh, Au). Similarly, for bimetallic catalysts, the optimal combinations are hypothesized to involve Ir or Pt paired with a metal exhibiting strong OH* adsorption, such as Ru. This pairing is expected to enhance HOR activity by complementing the already strong electron-accepting and H2 adsorption properties of Ir and Pt with effective OH* adsorption from Ru (RuIr and PtRu). This descriptor-aided design is a direct extension of our findings from the monometallic systems. Following this principle, secondary combinations may involve Ir or Pt paired with metals less effective in OH* adsorption, such as Au or Rh (AuIr, PtRh, PtIr, PtAu, and RhIr). Lastly, combinations lacking Ir or Pt are expected to exhibit the lowest HOR activity (RuRh, AuRu, and AuRh), as electron-accepting tendency plays a crucial role in enhancing HOR even with strong H2 and OH* adsorption properties. These hypotheses and proposed mechanisms will be further investigated in subsequent sections to provide comprehensive insights into all discussed monometallic and bimetallic catalysts.

Construction of a bimetallic catalyst family with controlled atomic arrangements

We first synthesized {100}-faceted Pd cubic seeds with an average edge length of 19.0 nm (Supplementary Fig. S8), providing a structurally uniform platform for subsequent shell growth. To construct bimetallic atomic layers with square atomic arrangements, we deposited approximately four atomic layers of equiatomic bimetallic alloys onto the {100}-faceted Pd cubic seeds via an epitaxial growth strategy, resulting in the formation of Pd@bimetallic core-shell nanocubes, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. We used the dropwise synthesis of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes with 4 atomic layers of shells as a typical example to introduce our epitaxial growth strategy. A precursor mixture of RuCl3·xH2O and H2IrCl6·xH2O in an equimolar ratio in ethylene glycol (EG; solvent and reducing agent) was slowly injected at a rate of 0.8 mL h-1 into another EG solution that contained Pd cubic seeds, ascorbic acid (AA; reducing agent), poly-(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP; colloidal stabilizer), and Br− (deceleration of reduction kinetics) at a temperature of 195 oC. A high enough reaction temperature of 195 oC is needed to increase the reduction power of EG and promote surface diffusion of the deposited Ru and Ir atoms to avoid the island growth on the seeds and thus layer-by-layer epitaxial growth (Supplementary Fig. S9). Most importantly, our kinetic study further revealed that introducing Ru(III) and Ir(IV) ions drop by drop during the synthesis could facilitate the formation of bimetallic layers with the atomic-mixing phase rather than a phase-separated phase (Supplementary Figs. S10 and S11). The other nine types of bimetallic layers and five mono-metallic layers on the Pd cubic seeds were also prepared using the typical protocols mentioned above except for varying the types of the metal precursors used (Supplementary Figs. S12 and S13).

a Schematic of epitaxial growth to obtain bimetallic atomic layers on Pd cubic seeds enclosed by {100} facets. b–f TEM, HAADF-STEM, FFT, and EDS-mapping analysis of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes. g ICP-OES analysis of Ru and Ir elements in the RuIr atomic layers. h XPS spectrum of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes for Ru 3p. i XPS spectrum of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes for Ir 4f. Source data for Fig. 2 are provided as a Source Data file.

Figure 2b shows a transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of the Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes with smooth surfaces, suggesting the involvement of layer-by-layer epitaxial growth. As shown in Fig. 2c, high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) of the single Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocube shows a significant contrast between the Pd core and the Ru0.47Ir0.53 shell owing to the difference in atomic number between these elements. The atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM of Fig. 2d further confirms the periodic lattice extending across the interface between the core and subnanometer-thick shell of only around 4 atomic layers. An average interplanar spacing of 0.192 nm is observed for the (002) plane of the FCC structure, based on measurements across three distinct lattice fringes within the four atomic layers of the RuIr shell on the Pd cubic seeds. This value is consistent with the corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern (Fig. 2e). These TEM, atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM, and FFT analyses demonstrate that the epitaxial growth strategy successfully yields bimetallic Ru0.47Ir0.5 atomic layers enclosed by {100} facets with square atomic arrangements. Note that alloying of Ru with Ir via epitaxial growth enables the formation of FCC atomic layers on the Pd seeds, which is not the thermodynamically stable phase for bulk Ru (hexagonal close-packed, HCP) under ambient conditions, consistent with the X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Supplementary Fig. S14). As shown in Fig. 2f, energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS) elemental mappings show th at Ru and Ir elements are homogeneously distributed on the entire Pd surface. The inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) analysis reveals that the atomic percentages of Ru and Ir elements are 47 and 53% (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Tables S5 and S6), respectively, in good agreement with the original feeding ratios of the precursor mixture. In addition, the surface chemical states of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes were characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). As shown in Fig. 2h, the Ru 3p XPS spectrum revealed the coexistence of major metallic Ru(0) and minor oxidized Ru(IV) species, attributable to the highly oxophilic nature of Ru atoms on the outermost surface when exposed to air37. Similarly, the Ir 4f XPS spectrum (Fig. 2i) demonstrated the presence of major metallic Ir(0) and minor oxidized Ir(IV) states. This observation can be ascribed to the spontaneous oxidation of the outermost surface of the RuIr alloy upon air exposure.

Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 3, synchrotron X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was used to reveal the atomic-mixing phase of Ru0.47Ir0.53 shells as well as the electronic interactions between the Ru and Ir elements in the Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes. Figure 3a, b shows the X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra of Ru K-edge and Ir L3-edge. Compared to the reference samples of metallic foils and oxides, most of the Ru and Ir elements were in a metallic state, which is consistent with the XPS results. Moreover, the Ru K-edge shifts slightly to higher energy, while the white line structure of the Ir L3-edge decreases. This indicates electron transfer from Ru atoms to Ir atoms, consistent with DFT predictions showing the superior electron-accepting tendency of Ir (Fig. 1d). In the post-edge spectra of the constituent elements within the Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53, deviations in both intensity and oscillatory patterns are evident compared with the foil and oxides. These observations suggest orbital hybridization within the bimetallic Ru0.47Ir0.53 layers, contributing to the fine-tuning of their electronic structure. The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra were further used to determine the coordination environments of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53. As shown in Fig. 3c, d, the Fourier transformed EXAFS (FT-EXAFS) spectra of Ru and Ir in Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 split from single peak to doublet at positions about 2.0 and 2.7 Å, which manifests the re-ordering of atoms around elements center38,39,40,41. Furthermore, Fig. 3e, f and Supplementary Table S7 show the EXAFS fittings results on both Ru and Ir components of the Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53. The average coordination numbers (CN) for Ru-Ir, Ru-Ru, and Ru-O in the Ru case were determined to be 3.922, 3.190, and 1.758, respectively. On the other hand, the coordination numbers for Ir-Ru and Ir-Ir in the Ir case were found to be 3.990 and 4.674. These values suggest that both Ru and Ir atoms are surrounded by a nearly equal number of heteronuclear and homonuclear neighbors. Given the overall atomic ratio of Ru:Ir ≈ 1:1, these coordination statistics are in good agreement with the expected values for a randomly mixed equiatomic Ru0.5Ir0.5 solid-solution alloy, where each atom ideally has ~6 nearest neighbors of the other type in a FCC lattice (i.e., 50% of the 12 nearest neighbors). This agreement further supports the formation of a homogeneously mixed atomic phase without evidence of phase segregation, consistent with the atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM images, EDS elemental mappings, and XRD analysis. Again, the wavelet analysis of the k2-weighted EXAFS (WT-EXAFS) shows the significant difference in coordination environments between Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes and the corresponding foils and oxides (Fig. 3g–l). These results support the random elemental mixing of Ru0.47Ir0.53 atomic layers with electronic interactions between the Ru and Ir elements.

a XANES spectra of Pd@RuIr core-shell nanocubes and their corresponding metallic foils and oxidation states at the Ru K-edge. b XANES spectra of Pd@RuIr core-shell nanocubes and their corresponding metallic foils and oxidation states at the Ir L3-edge. c FT-EXAFS spectra of Pd@RuIr core-shell nanocubes and their corresponding metallic foils and oxidation states at the Ru K-edge. d FT-EXAFS spectra of Pd@RuIr core-shell nanocubes and their corresponding metallic foils and oxidation states at the Ir L3-edge. e FT-EXAFS spectra (lines) and curve fits (points) of Pd@RuIr core-shell nanocubes at the Ru K-edge. f FT-EXAFS spectra (lines) and curve fits (points) of Pd@RuIr core-shell nanocubes at the Ir L3-edge. g–i WT-EXAFS contour maps of Pd@RuIr core-shell nanocubes, Ru foil, RuO2 at Ru K-edge. j–l WT-EXAFS contour maps of Pd@RuIr core-shell nanocubes, Ir foil, IrO2 at Ir L3-edge. Source data for Fig. 3 are provided as a Source Data file.

Catalytic activity and durability

The electrocatalytic performances of various subnanometer bimetallic layers on the Pd cubic seeds for alkaline HOR were studied, and their monometallic counterparts as well as the commercial Pt/C were also compared (Fig. 4a, b). Prior to electrochemical measurements, all nanocrystal catalysts were subjected to a well-established acetic acid cleaning protocol to remove surface-adsorbed PVP (Supplementary Fig. S15). We examined the HOR catalytic activities by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) polarization curves in a three-electrode setup with H2-saturated 0.1 M KOH solution. All the electrocatalytic studies in this work were conducted with non-iR corrected. When performing linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) in H2-saturated 0.1 M KOH solution, we observed the large anodic currents over 0 VRHE (versus reversible hydrogen electrode, VRHE), indicating the oxidation reaction of H2. As shown in Fig. 4a, b, the LSV polarization curves of the monometallic and bimetallic catalysts normalized by the electrode area of 0.07 cm2 were compared, respectively. Among the monometallic layers on the Pd cubic seeds, the Ir catalysts showed the highest geometric current densities (Jg) under the whole potential range and the HOR activity followed the trend of Ir > Pt > Ru > Rh >Au. Most importantly, the current was greatly increased on some specific bimetallic alloys such as Ru0.47Ir0.53 and Pt0.47Ru0.53, implying the positive synergistic effects between the elements to enhance the HOR kinetics. The Ru0.47Ir0.53 performed the highest current of Jg at low anode potentials of <0.2 VRHE among all bimetallic layers, which is critical to obtaining high HOR catalytic activity in alkaline electrolytes. The current profiles are inclined at high potentials of > 0.2 VRHE for all three RuIr alloys with different atomic ratios of Ru and Ir (i.e., Ru0.67Ir0.33, Ru0.47Ir0.53, and Ru0.41Ir0.59) (Supplementary Fig. S16), which could be attributed to the oxophilic surface of RuIr42,43,44.

a Polarization curves of Pd@M core-shell nanocubes (M = Ir, Pt, Ru, Rh, and Au) and commercial Pt/C in H2-saturated 0.1 M KOH at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1 and rotating speed of 1600 rpm. b Polarization curves of Pd@bimetallic alloy core-shell nanocubes in H2-saturated 0.1 M KOH at a rotating speed of 1600 rpm with a scan rate of 5 mV s−1. c Comparison of the specific activity at 0.05 VRHE. These data are obtained with no iR correction. Source data for this Figure are provided as a Source Data file.

Bimetallic samples in H2-saturated 0.1 M KOH (rotation speed: 1600 rpm) exhibited mass-transport-limiting currents up to 2.50 mA/cm2. The best-performing Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes reached a current density of 2.62 mA/cm2 at 100 mVRHE, which approaches the mass-transport-limiting current compared with other reported literature values (typically 2.3–2.8 mA/cm2) (Supplementary Table S8). To further characterize the HOR kinetics, the influence of H2 mass transport was evaluated by analyzing the polarization behavior of commercial Pt/C and Ru0.47Ir0.53 at varying rotation speeds (400, 625, 900, 1225, 1600, 2025, and 2500 rpm; Supplementary Fig. S17). As shown in Supplementary Fig. S17, the polarization currents increased with rotation speed, indicating a diffusion-controlled process. The corresponding Koutecky–Levich plots at 100 mVRHE show a linear relationship between the inverse current and the square root of the rotation rate. The slope for Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 is 4.60 cm2 mA-1 s-1/2, which closely matches the theoretical value of 4.20 cm2 mA-1 s-1/2 for a two-electron HOR process and falls within the typical range reported in the literature (4.30–4.90 cm2 mA-1 s-1/2)45,46,47, further confirming that the reaction is limited by H2 mass transport. In addition, kinetic current densities (Jk) were extracted from the Koutecky–Levich equation (Supplementary Fig. S18). Over the potential range of 0–50 mVRHE, Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 nanocubes exhibit substantially higher kinetic activity compared to commercial Pt/C.

To compare their catalytic activities, the geometric current densities at 0.05 VRHE (Jg@0.05V) and the specific activities normalized to the ECSA (Supplementary Figs. S19–S21) at 0.05 VRHE (Js@0.05V) were determined, as summarized in Supplementary Fig. S22 and Fig. 4c, respectively. On the other hand, the values of the exchange current density (J0, s) normalized to ECSA were determined by linear fitting of the micro-polarization region (-10 to 10 mVRHE) (Supplementary Figs. S23 and S24). To the Jg@0.05V, Js@0.05V, and J0, s, the Ru0.47Ir0.53 layers have the highest HOR activity among all studied catalysts, including 5 monometallic and 10 bimetallic layers as well as the commercial Pt/C catalysts. Specifically, the Js@0.05V of Ru0.47Ir0.53 (0.66 mA/cm2) was approximately three times greater than that of commercial Pt/C (0.22 mA/cm2), and also surpassed all other monometallic and bimetallic catalysts examined in this study. These results suggest that Ru0.47Ir0.53 possesses the highest intrinsic catalytic activity toward alkaline HOR. In addition, these experimental results align with the DFT-based predictions of HOR activity rankings (Fig. 1) for both monometallic ((Ir, Pt) > Ru > (Rh, Au)) and bimetallic catalysts ((RuIr, PtRu) > (AuIr, PtRh, PtIr, PtAu, RhIr) > (RuRh, AuRu, AuRh)).

To address the potential role of Pd as a hydrogen-adsorbing component, we also conducted additional control experiments using Pd@Pd0.52Ru0.48 core-shell nanocubes and Pd@Pd counterparts (Supplementary Fig. S25). Although Pd is known for strong hydrogen adsorption, the measured geometric current density (0.81 mA/cm2) and specific activity (0.24 mA/cm2) of Pd@Pd0.52Ru0.48 were significantly lower than those of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 and Pd@Pt0.47Ru0.53 at 0.05 VRHE. For further comparison, we also synthesized monometallic Pd atomic layers on Pd cubic seeds (i.e., Pd@Pd), which similarly showed poor catalytic activity. Moreover, our DFT calculations show that Pd has a lower work function (5.11 eV) than Ir (5.59 eV) and Pt (5.77 eV) (Fig. 1c), suggesting a relatively higher Fermi level and weaker electron-accepting tendency. The calculated H2 adsorption energy on Pd is -1.06 eV, which is less negative than that of Ir (-1.45 eV) and Pt (-1.34 eV), indicating weaker H2 binding. Together, these results suggest that Pd is less effective as a hydrogen adsorption site in the context of alkaline HOR, especially when compared to Ir and Pt, which not only exhibit stronger hydrogen binding but also higher electron-accepting capabilities. As a result, the PdRu bimetallic catalyst, despite the strong OH* adsorption ability of Ru, did not exhibit enhanced HOR activity relative to RuIr or PtRu.

Furthermore, we evaluated the HOR durability of three representative Pd@bimetallic core-shell nanocubes with distinct activity levels: Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 (higher activity), Pd@Pt0.51Ir0.49 (moderate activity), and Pd@Au0.45Rh0.55 (lower activity), as shown in Fig. 5a–c. Commercial Pt/C was also included for comparison in Fig. 5d. Durability tests were performed by continuous potential cycling between -0.05 and 0.7 VRHE in H2-saturated 0.1 M KOH. The current density at 0.05 VRHE (Jg@0.05V) for Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 decreased by only 20.9% after 3000 cycles, starting from an initial value of 1.77 mA/cm2. In contrast, Pd@Pt0.51Ir0.49 and Pd@Au0.45Rh0.55 exhibited more significant losses of 29.5% and 43.1%, respectively. Commercial Pt/C also showed a 30.6% decrease in current density. We also complemented the chronoamperometry test for commercial Pt/C and Ru0.47Ir0.53 in Supplementary Fig. S26. The results showed Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 retained 89% of its activity, whereas commercial Pt/C fell to 20% at 20000 seconds, demonstrating the superior long-term stability of the Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 catalyst. These results suggest that Ru0.47Ir0.53 layers on the Pd cubic seeds can serve as the most active and durable HOR catalysts.

CV curves in H2-saturated 0.1 M KOH and rotating speed of 1600 rpm of a Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53, b Pd@Pt0.51Ir0.49, c Pd@Au0.45Rh0.55 core-shell nanocubes, d Commercial Pt/C at 1st, 750th, 1500th, and 3000th cycles. e HAADF-STEM and EDS-mapping analysis of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes after 3000 CV cycles. These data are obtained with no iR correction. Source data for this Figure are provided as a Source Data file.

The enhanced durability of Pd@RuIr can be attributed to both its structural robustness and favorable adsorption energetics for HOR intermediates. HAADF-STEM imaging and EDS mapping (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. S27) confirm that the RuIr shell remains structurally intact after 3000 cycles, with no signs of degradation or detachment from the Pd core. In parallel, DFT calculations reveal that the RuIr surface provides well-balanced adsorption strengths for both H* and OH*, enabling rapid and reversible intermediate turnover. This dual-site behavior is critical for promoting alkaline HOR, where both species participate in the reaction mechanism. By contrast, Pd@Au0.45Rh0.55, despite retaining its structural morphology and elemental distribution after 3000 cycles (Supplementary Fig. S28), exhibited a substantial 43.1% activity loss. DFT results suggest that the weak and unbalanced adsorption of H* and OH* on AuRh impedes efficient intermediate turnover, leading to surface blockage and deactivation over time. These findings highlight that long-term catalytic durability arises not only from structural integrity but also from optimized surface binding characteristics that sustain the reaction kinetics.

To further validate the practical viability of our Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 catalyst, we performed single-cell anion exchange membrane fuel cell (AEMFC) testing under operating conditions (Supplementary Fig. S29). A membrane electrode assembly (MEA) was fabricated using Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 as the anode catalyst and commercial Pt/C as the cathode. The polarization curve in Supplementary Fig. S29, which plots cell voltage versus current density, demonstrates the catalyst’s performance in a functional AEMFC. The cell exhibits an open-circuit voltage of approximately 1.08 VRHE and achieves a current density exceeding 700 mA cm-2 at 0.2 VRHE. These results confirm the effectiveness of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 as an active HOR catalyst in real-device operation.

Catalytic mechanism

Operando XAS measurements were performed under different conditions, including air, open circuit potential (OCP), and the specific potentials of 0.65, 0.9, and 1.05 VRHE at the Ru K-edge and Ir L3-edge of representative Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes to identify the active sites and elucidate the underlying mechanism within an H2-saturated 0.1 M KOH electrolyte. The XANES and corresponding FT-EXAFS spectra for the Ru K-edge and Ir L3-edge are shown in Fig. 6a. Notably, the distinct peak at approximately 1.50 Å is enhanced in the FT-EXAFS at OCP and various applied potentials (Fig. 6b). These observations suggest the adsorption of OH* intermediates onto the Ru sites. In contrast, the white line structure in the Ir L3-edge of XANES remains constant within the range from OCP to 0.65 VRHE, while displaying an increase from 0.65 to 0.9 and 1.05 VRHE (Fig. 6c). Additionally, the positions of the first-shell peaks observed at Ir L3-edge of FT-EXAFS remain almost unchanged throughout the HOR (Fig. 6d). These results are likely attributed to the adsorption and dissociation of molecular H2 on the Ir sites, as supported by the DFT results (Fig. 1)48. The above operando XAS analysis reveals that Ru and Ir sites facilitate the selective adsorption of OH* and H2 intermediates, respectively, leading to the synergistic effect during the HOR process.

a, b Operando XANES spectra and FT-EXAFS spectra of RuIr atomic layers measured under air, OCP and applied potentials of 0.65 VRHE, 0.90 VRHE, and 1.05 VRHE during alkaline HOR at the Ru K-edge. c, d Operando XANES spectra and FT-EXAFS spectra of RuIr atomic layers measured under air, OCP and applied potentials of 0.65 VRHE, 0.90 VRHE, and 1.05 VRHE during alkaline HOR at the Ir L3-edge. e CV curves of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes, Pd@Ru core-shell nanocubes, Pd@Ir core-shell nanocubes and commercial Pt/C in N2-saturated 0.1 M KOH. f CO stripping curves of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes, Pd@Ru core-shell nanocubes, Pd@Ir core-shell nanocubes and commercial Pt/C. g Adsorption of OH* on Ru, Ir, and RuIr surfaces, shown in both top and cross-sectional views, along with calculated OH* adsorption energies. h Schematic of the alkaline HOR catalytic mechanism. These data are obtained with no iR correction. Source data for this Figure are provided as a Source Data file.

To gain deeper insights into the synergistic effect of the bimetallic Ru0.47Ir0.53 on the binding affinity of Had and OHad species on the surface, we further employed electrochemical desorption curves for hydrogen underpotential deposition (HUPD) and CO-stripping curves, respectively. We also examined the corresponding Pd@Ru and Pd@Ir core-shell nanocubes, along with commercial Pt/C catalysts, for comparison. As shown in Fig. 6e, in the cyclic voltammetry (CV) experiments regarding hydrogen underpotential deposition (HUPD), stronger hydrogen binding is indicated by observing the shift of HUPD peaks towards higher potentials6,7,49. However, CV of Pd@Ru core-shell nanocubes do not show a significant hydrogen desorption peak, suggesting that the binding strength of hydrogen to Pd@Ru core-shell nanocubes is too weak. Thus, the potentials of HUPD peaks for these three samples follow this order: Pd@Ir (0.255 VRHE) > commercial Pt/C (0.221 VRHE) > Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 (0.215 VRHE), which is consistent with the DFT and XAS results (Figs. 1 and 6c, d). In addition, the HUPD analyses of varying Ir composition (Supplementary Fig. S30) also suggest that Ir is responsible for hydrogen adsorption, and the binding strength of Had could be weakened when alloying Ir with Ru to form a bimetallic surface, resulting in a moderate range of strength. Furthermore, we also conducted CO stripping experiments to estimate the binding strength for OHad species, as OHad can facilitate the conversion of surface adsorbed COad intermediates into CO2, as shown in Fig. 6f. Generally, lower potential of CO-stripping peak suggests a greater affinity for OHad adsorption46. Interestingly, the trend of CO-stripping peaks is as follows: Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 (0.643 VRHE) <commercial Pt/C (0.672 VRHE) < Pd@Ru (0.682 VRHE) < Pd@Ir (0.861 VRHE). The CO-stripping peak for commercial Pt/C displays a shoulder, likely attributed to the presence of different facets on the catalyst surface50. These experimental results corroborate our DFT-predicted findings that Ir exhibits weaker OH* adsorption compared to Ru. Figure 6g illustrates OH* adsorption on monometallic Ru, Ir, and bimetallic Ru-Ir and Ru-Ru sites (confirmed by Ru-Ir and Ru-Ru bonding through XAS analysis, as shown in Supplementary Table S7 for the RuIr surface. DFT calculations show OH* adsorption energies of -0.67 eV for Ru and -0.21 eV for Ir, with OH* adsorption energies of -0.40 eV and -0.61 eV on the Ru-Ir and Ru-Ru sites for the RuIr surface, respectively. The similar OH* binding strengths observed between Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 and Pd@Ru from the CO stripping experiments (Fig. 6f) could be attributed to the potential OH* adsorption occurring primarily on the Ru-Ru sites within the RuIr surface.

Following the Sabatier principle51, catalytic activity reaches a maximum when each intermediate binds neither too weakly nor too strongly. The Ir sites in Ru0.47Ir0.53 provide an exothermic H2 dissociation energy of -1.45 eV, while neighboring Ru sites bind OH* at -0.67 eV. Together with the moderate OH* adsorption, this places RuIr near the apex of the classical volcano curve for alkaline HOR1. In contrast, pure Ir (with excessively strong H* binding) and pure Ru (with insufficient electron-accepting ability) fall off the optimum. These findings demonstrate how bifunctional site design enables a balanced adsorption regime that enhances the overall turnover frequency in alkaline HOR. Also, according to the recently established hydroxyl binding energy-volcano for alkaline HOR/HER, the turnover frequency peaks when ΔGOH* ≈ -0.6 to -0.8 eV52. The Ru sites in Ru0.47Ir0.53 bind OH* at -0.67 eV, i.e., near the apex, ensuring that OH* formed during water dissociation (Tafel step) can desorb or react with adjacent H* (Volmer step) without site poisoning.

Taken together, DFT calculations, electrochemical measurements, and operando XAS collectively reveal that the HOR on the Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 catalyst proceeds predominantly via the Tafel–Volmer mechanism. Specifically, our DFT results (Fig. 1c) show that H2 dissociates exothermically on Ir sites (Ead = -1.45 eV), indicating that molecular hydrogen can split spontaneously without requiring electron–proton transfer, thereby facilitating the Tafel step. In parallel, Ru exhibits stronger OH⁻ affinity, with an OH* adsorption energy of -0.67 eV, significantly more negative than that on Ir (-0.21 eV), highlighting Ru as the dominant OH* adsorption center under alkaline conditions. These findings support a mechanistic picture in which H2 initially dissociates on Ir sites (Tafel step), while the resulting H atoms are subsequently oxidized by OH* adsorbed on neighboring Ru sites (Volmer step). The synergistic interplay between Ir and Ru thus accelerates the HOR kinetics by optimizing both hydrogen activation and hydroxide adsorption. As illustrated in Fig. 6h, this dual-site mechanism combines the strong electron-accepting ability and H2 adsorption capability of Ir with the high OH* affinity of Ru, thereby facilitating efficient HOR catalysis under alkaline conditions.

Discussion

To summarize, we have developed a rational design strategy for a family of bimetallic catalysts aimed at optimizing the HOR catalyst through a combination of theoretical and experimental approaches. Our efforts also provide deeper insights into the HOR mechanism using operando techniques. Initially, our DFT calculations predicted that the RuIr bimetallic catalyst would be the most active for HOR among the screened monometallic and bimetallic systems, based on electron-accepting tendencies and H2/OH* adsorption strengths of the bimetallic catalysts. Confirming these predictions, the RuIr bimetallic catalyst demonstrated the highest specific activity of 0.66 mA/cm² for HOR at an overpotential of 0.05 VRHE, approximately 3 times greater than that of commercial Pt/C catalysts (0.22 mA/cm²). Additionally, the RuIr catalyst exhibited superior catalytic durability compared to other catalysts. Operando XAS analysis and electrochemical measurements revealed a strong synergistic effect within RuIr, where Ir shows superior electron-accepting tendency and strong H2 adsorption, while Ru exhibits strong OH* adsorption, significantly enhancing the alkaline HOR process. These results underscore the importance of engineering bimetallic catalysts with appropriate binding strengths for intermediate species when designing high-performance alkaline HOR catalysts. This approach could potentially be extended to other bimetallic or multi-component catalysts and catalytic reactions involving multiple intermediates.

Methods

Materials

Sodium tetrachloropalladate(II) (Na2PdCl4), potassium tetrachloroplatinate(II) (K2PtCl4), rhodium(III) chloride hydrate (RhCl3·xH2O), hydrogen hexachloroiridate(IV) chloride hydrate (H2IrCl6·xH2O), ruthenium(III) chloride hydrate (RuCl3·xH2O), hydrogen tetrachloroaurate(III) trihydrate (HAuCl4·3H2O), L–ascorbic acid (AA), potassium bromide (KBr), and poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP, MW ≈ 55,000), aqueous hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37% by weight), aqueous nitric acid (HNO3, 70% by weight) and ethylene glycol (EG) were all obtained from Sigma–Aldrich. Deionized (DI) water with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm was used for all the experiments.

Synthesis of Pd cubic seeds

To prepare the 19.0-nm Pd cubic seeds, a standardized protocol is used based on a previous study53. An 8-mL water-based solution comprising AA (60 mg), PVP (105 mg), and KBr (600 mg) is introduced into a 23-mL vial. Subsequently, the solution undergoes pre-heating at 80 °C for 10 minutes. After this pre-heating step, a single injection of 3 mL of aqueous Na2PdCl4 solution, having a concentration of 19 mg/mL, is swiftly added into the vial. The resulting mixture is sealed with a cap and maintained at 80 °C for 3 hours under continuous magnetic stirring. Following this, the mixture is allowed to cool down to room temperature. The produced Pd cubic seeds undergo a purification process involving centrifugation and three washes with DI water.

Epitaxial growth of subnanometer bimetallic layers on Pd cubic seeds

For the preparation of Pd@bimetallic alloy core-shell nanocrystals, the epitaxial growth strategy is used. To illustrate this strategy, we present the synthesis of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocubes as a representative example. Within the context of standard epitaxial growth for the synthesis of Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocrystals, we prepare 0.40 mL of the suspension containing Pd cubic seeds in EG, along with 20 mg of AA, 100 mg of PVP, 60 mg of KBr, and 3.1 mL of EG, into a 20-mL vial. This vial undergoes heating at 110 °C for 20 minutes under magnetic stirring. The temperature is then elevated to 195 °C within a 20-minute interval. Subsequently, 14 mL of a precursor solution comprising metal precursors of RuCl3·xH2O and H2IrCl6·xH2O in EG, each in equimolar proportion, is introduced into the reaction solution using a syringe pump at a controlled rate of 0.8 mL h-1. To modulate the number of Ru0.47Ir0.53 atomic layers on the Pd cubic seeds to around 4, adjustments to the concentration of individual metal precursors are executed, maintained at 0.042 μmol mL-1. Following the introduction of the precursor solution, the reaction mixture is maintained at 195 °C for 2 hours. After that, the Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 core-shell nanocrystals are collected by centrifugation, washed once with acetone and two times with DI water, and finally dispersed in DI water. The methodologies for producing monometallic (Pt, Ir, Ru, Rh, and Au) and bimetallic (PtAu, PtRu, PtRh, PtIr, AuRu, AuRh, AuIr, RuRh and RhIr) alloy shells onto the Pd cubic seeds align with the standard epitaxial growth process detailed above. In these experiments, K2PtCl4, RhCl3·xH2O, and HAuCl4·3H2O act as the metal precursors for Pt, Rh, and Au elements, respectively.

Kinetic analyses of the reduction reactions of Ru(III) and Ir(IV) precursors during the epitaxial growth using ICP-OES measurements and mathematical analysis

We conducted kinetic analyses of the reduction process of Ru(III) and Ir(IV) precursors by measuring the residual concentrations of the precursor ions in the reaction solution at various time intervals during the epitaxial growth of Pd@RuIr core-shell nanocubes using ICP-OES measurements. In a standard procedure, 0.40 mL of the Pd cubic seeds suspension in EG, 20 mg of AA, 100 mg of PVP, 60 mg of KBr, and 3.1 mL of EG were added into a 20-mL vial. This mixture was heated to 110 °C for 20 minutes under magnetic stirring and then the temperature was increased to 195 °C within 20 minutes. Subsequently, 7 mL of a precursor solution containing equal molar amounts of RuCl3·xH2O and H2IrCl6·xH2O (0.252 μmol/mL each) was added to the reaction solution in one shot using a pipette, and the timing was initiated. At designated time intervals, a 0.1 mL aliquot was extracted using a glass pipette and promptly combined with 0.9 mL of deionized (DI) water held in an ice bath to quench the reaction. The mixtures were then centrifuged at 30,000 rpm for 15 minutes to precipitate all solid products, leaving the residual metal ions in the supernatant. Finally, the supernatants were diluted with DI water in preparation for ICP-OES analysis.

Subsequently, we need to determine the reduction rate constant k for the Ru(III) and Ir(IV) precursors through curve fitting. As documented in the literature, the reduction process of a metal precursor typically involves interactions and electron transfer between precursor ions and the molecules acting as reductants. This process can be described by a second-order kinetic rate law. Given that the reductant (i.e., AA) in our system is present in significant excess compared to the metal precursors, and its concentration remains relatively constant throughout the reaction, the rate law can be simplified to a pseudo-first-order equation54:

where \(k\) is the combined rate constant (hereafter referred to as the rate constant); \([{{{{\rm{M}}}}}^{{{{\rm{X}}}}+}]\) and \(\left[{\mbox{AA}}\right]\) are the concentrations of the metal precursor and AA, respectively. Integration of this equation yields:

where \({[{{{{\rm{M}}}}}^{{{{\rm{X}}}}+}]}_{t}\) and \({[{{{{\rm{M}}}}}^{{{{\rm{X}}}}+}]}_{0}\) represent the concentrations of a metal precursor at a specific time point t and t = 0. By plotting \({{\mathrm{ln}}}{[{{{{\rm{M}}}}}^{{{{\rm{X}}}}+}]}_{t}\) versus t, the rate constants for the Ru(III) and Ir(IV) precursors can be determined through the curve fittings (Supplementary Fig. S10).

Assuming a pseudo-first-order reaction, we can quantify the individual consumption of metal precursor ions from each droplet and represent the total quantity of precursor ions remaining in the reaction mixture at time t (\({{\mbox{n}}}_{t}\)) as the cumulative sum of all droplets (Supplementary Fig. S11a)54:

where n0 is the number of precursor ions in a single droplet, k is the rate constant derived from the curve fitting of experimental data, \(\tau\) represents the time gap between adjacent drops, and N denotes the total number of droplets that have been introduced up to time t. Using the derived \({{\mbox{n}}}_{t}\), we can calculate the quantities of metal atoms generated through the reduction of precursor ions between successive droplets (n0-(nt-nt-τ). This data allows us to determine the instantaneous percentages of Ru and Ir metal atoms generated (Supplementary Fig. S11b). Additionally, we can derive the total number of metal atoms generated \(({{\mbox{n}}}_{0}\times N-{{\mbox{n}}}_{t})\) for each precursor up to time t, which can be further used to calculate the composition of shell atoms in the product as a function of time (Supplementary Fig. S11c)54,55.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS)

The XAS spectra are obtained through a customized three-electrode system employing a fluorescence mode. This system features a Teflon container that is equipped with a window enveloped by Kapton tape. The experimental conditions for XAS measurements are identical to those described above for electrocatalytic HOR measurements. Within the XAS measurements, the Kapton tape is traversed by X-rays, and a detection mode of total-fluorescence-yield is applied. These measurements are conducted with the use of Lytle detectors located at the TPS 44 A beamline within the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC) in Hsinchu, Taiwan. The obtained data is subsequently subjected to analysis using Athena software. This facilitates the examination of XANES spectra of the L3-edge of Ir and the K-edge of Ru. Furthermore, FT-EXAFS analysis is conducted. This involves applying a Fourier transform on k2-weighted oscillations of EXAFS data, enabling the assessment of the local coordination environments surrounding the target elements.

Electrocatalytic measurements for alkaline hydrogen oxidation reaction (HOR)

Within this study, HOR electrochemical measurements are conducted using a Nova electrochemical workstation, specifically the Metrohm Autolab PGSTAT204 model. For the rotating electrode setup, a glassy carbon cell is employed as the working electrode, accompanied by Pt acting as the counter electrode, and Hg/HgO serving as the reference electrode. In this study, prior to electrochemical measurements, all nanocrystal catalysts are subjected to a well-established acetic acid cleaning protocol to remove surface-adsorbed PVP4,5. In general, 1.5 mg of the as-synthesized nanocrystal catalysts and 6 mg of Vulcan XC-72R carbon are first dispersed separately in 3 mL and 12 mL of DI water, respectively. Each dispersion is subjected to ultrasonication for 3 hours at room temperature to ensure uniform dispersion. The two suspensions are then mixed and further sonicated for 30 minutes to achieve homogeneous loading of the nanocrystals onto the carbon support. The resulting carbon-supported nanocrystals are collected by centrifugation and redispersed in 10 mL of aqueous acetic acid and heated at 60 °C for 3 hours under stirring. This acetic acid treatment is commonly used to displace surface-bound PVP through ligand exchange or desorption56,57. Following the acid treatment, the samples are thoroughly washed four times with ethanol and another four times with DI water to ensure complete removal of residual acetic acid and any remaining organic species. After washing, the samples are dried in an oven at 90 °C to remove water or any residual solvent, yielding the final clean catalyst powder used for subsequent electrochemical testing.

In the preparation of the catalyst ink, 1 mg of catalysts in carbon support (Vulcan XC-72R) with 20 wt% is dispersed in a mixture of 0.5 mL isopropanol, 0.5 mL DI water, and 0.02 mL of a 5 wt% Nafion solution. To ensure uniform dispersion of the catalyst, the catalyst inks are ultrasonicated in an ice bath for 60 minutes. Subsequently, 3.6 μL of the resulting catalyst suspension is drop-cast onto a glassy carbon electrode (geometric area: 0.07 cm2) in three equal aliquots. Prior to electrochemical measurements, the electrode is dried in an atmosphere saturated with isopropanol. Prior to the electrocatalytic measurements, the electrolyte is first purged with N2 gas for 30 minutes. To clean the electrode surface, 50 cycles of CV testing are conducted, with the potential range spanning from 0.05 to 1.1 VRHE, and employing a scan rate of 500 mV s-1. After that, HOR catalytic measurements are performed within a 0.1 M KOH electrolyte, which had been purged with H2 gas for 30 minutes. CV and LSV curves are systematically recorded over a potential range spanning from -0.1 to 0.7 VRHE with non-iR corrected. These measurements are conducted under a rotational speed of 1600 rpm at the scan rates of 10 mV s-1 and 5 mV s-1, respectively. For evaluating the long-term durability, an intensive examination involving 3000 cycles of CV was conducted within the same potential range. This durability test occurred within an electrolyte saturated with H2. The measured potentials vs. Hg/HgO were standardized with a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) based on the formula E vs. RHE = Emeasured + 0.059 pH + 0.118.

Exchange current density (J0) can be obtained from the slope (J/η) of linear fitting of the micro-polariztion region near the equilibrium potential (-10 to 10 mVRHE). In this region, the Bulter-Volmer equation can be simplified to Eq. (S4)4,52:

where J is the measured current density, which is also referred to as the geometry current density. η, F, R, and T represent the overpotential, the Faraday constant, the universal gas constant, and the temperature in Kelvin, respectively.

The kinetic current (Jk) was calculated based on the Koutecky–Levich equation58,59:

where J stands for the measured current density, Jd represents the diffusion current density, B is the Levich constant, C0 is the solubility of H2 (7.33 × 10-4 mol L-1), F is Faraday constant (96485 C mol-1), D is the H2 diffusion coefficient in 0.1 M KOH (4.5×10-5 cm2 s-1), ν is the kinematic viscosity (1.01 × 10-2 cm2 s-1), and ω is the rotating rate.

Evaluation of electrochemical surface area (ECSA)

The electrochemical surface area is measured using the double-layer capacitance (Cdl)60. In the measurement of double-layer capacitance, CV with scan rates varying from 25 to 500 mV s-1 in a 0.1 M N2-saturated KOH electrolyte is utilized. A potential window of 0.1 VRHE, centered at the open circuit potential (OCP), is chosen for the non-faradaic region. To determine the double-layer capacitance, the cathodic and anodic currents are each divided by their corresponding scan rates to compute the slope.The ECSA is then derived using the following formula:

where CS represents a predetermined specific capacitance value, typically taken as 40 μF cm-² for mixed platinum-group metal surfaces in 0.1 M KOH61,62.

Electrode preparation and testing for AEMFC

Gas diffusion electrodes (GDEs) were prepared using an airbrush spraying technique by directly depositing catalyst ink onto hydrophobic carbon paper substrates. The gas diffusion layer (GDL) employed was Sigracet 39 BB, a non-woven carbon paper featuring a microporous layer (MPL) treated with 5 wt% polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) to enhance hydrophobicity and gas transport. Catalyst ink was formulated using either 20 wt% Premetek Pt/C or a synthesized Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 catalyst. The catalyst was dispersed at a concentration of 4 mg mL-1 in a solvent mixture of n-propanol and deionized water (1:1 v/v), with 5 wt% Sustainion XA-9 anion exchange ionomer added as the ionic conductor. The final ionomer content in the electrode was adjusted to 20 wt%. For the cathode, Pt/C catalyst was applied to achieve a platinum loading of 0.4 mgPt cm-2. The anode was prepared using a Pd@Ru0.47Ir0.53 catalyst with a metal loading 0.2 mg(Ir+Ru) cm-2. Metal loadings were precisely quantified using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF).

The membrane used was PiperION A15, an anion exchange membrane from Versogen. To replace the bromide (Br⁻) counter-ions present in the membrane and ionomer with hydroxide ions (OH⁻), the gas diffusion electrodes and membrane were immersed in 1 M KOH for 24 hours. Subsequently, both the membrane and electrodes were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water until the pH of the rinsing solution reached neutrality. Finally, the membrane and gas diffusion electrodes were assembled into a membrane electrode assembly (MEA) by sandwiching without hot pressing. The MEA, with an active area of 5 cm², was installed inside a 50 cm² single-cell hardware from Fuel Cell Technologies (FCT), which features graphite flow-field plates with a serpentine channel design. The cell was assembled by gradually tightening the bolts in 1 N·m increments up to a final torque of 5 N·m to ensure uniform compression, gas sealing, and mechanical stability. The assembled cell was then used for AEMFC performance evaluation.

Fuel cell performance was evaluated using a Scribner 850e test station with hydrogen (H2) supplied to the anode and oxygen (O2) to the cathode. The cell temperature was regulated by the 850e system using integrated cartridge heaters and cooling fans. Unless otherwise specified, all measurements were conducted at an absolute pressure of 120 kPaabs and under 80% relative humidity (RH) for both anode and cathode gas streams. Prior to testing, nitrogen (N2) was introduced to both electrodes at a flow rate of 500 mL min-1, and the cell temperature was gradually increased to 60 °C while maintaining 80% RH. Once the temperature and backpressure stabilized, the feed gases were switched to H2/O2, at 800 mL min-1 and 80% RH throughout the test. Before polarization measurements, an activation procedure was conducted by holding the cell voltage at 0.6 VRHE until stable output current was obtained. Polarization curves were subsequently recorded in voltage-control mode, sweeping from the open-circuit voltage (OCV) down to 0.15 VRHE, with a 30-second hold at each potential step.

Hydrogen underpotential deposition (HUPD) analysis

The hydrogen underpotential deposition (HUPD) curves are obtained in N2-saturated 0.1 M KOH by scanning the potential from 0.05 to 1.1 VRHE at a scan rate of 50 mV s-1. The peak observed in the CV curve in the HUPD region from 0.05 to 0.4 VRHE is analyzed, and the potential of the HUPD desorption peak (Epeak) serves as an indicator of hydrogen binding energy (HBE) for each sample.

CO-stripping analysis

The CO-stripping experiment is performed in 0.1 M KOH. First, a high-purity CO gas is purged into the electrolyte for 30 minutes to form a CO-saturated solution, and then the electrode potential is held at 0.1 VRHE for 10 minutes to allow CO to adsorb on the catalyst surface. Subsequently, N2 is purged for 20 minutes to remove residual CO from the solution. Finally, the CO stripping curves between 0 and 1.2 VRHE were obtained at a scan rate of 50 mV s-1 for two cycles.

Characterizations

The element contents are analyzed using an iCAP 7200 ICP-OES system (Thermo Scientific). TEM and HAADF-STEM images, along with EDS mapping, are acquired using a spherical-aberration corrected field emission TEM (JEOL, JEM-ARM200FTH) operating at 200 kV. The surface chemical states are examined through XPS with a high-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (ULVAC-PHI, PHI Quantera II). The XAS spectra are recorded at beamline TPS 44 A of the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center. Metal loadings on AEMFC electrodes are quantified using XRF spectroscopy (Thermo Scientific, ARL QUANT’X EDXRF Analyzer).

Constructions of monometallic and bimetallic catalyst atomic structures

The metallic catalyst structures were constructed based on our experimental setup, which involves epitaxial deposition onto Pd (100) cubic seeds. The Pd bulk phase was modeled using the \({{\mbox{Fm}}}\bar{3}{\mbox{m}}\) space group, and the (100) surface orientation was chosen. A vacuum layer of 20 Å was applied along the z-axis to avoid spurious interactions between periodic images. To determine an appropriate slab thickness, we performed surface energy convergence tests, leading to the choice of a six-layer slab for the monometallic surface models.

For identifying adsorption sites of H2 and OH*, we used the Delaunay triangulation algorithm63, implemented in Pymatgen64. As shown in Fig. 1b, this approach yielded four unique adsorption sites per surface. For each site, we generated 55 different molecular configurations by rotating the H2 and OH* species in vertical, horizontal, and inclined orientations (10° increments), symmetrically placing them on both sides of the slab. In total, 1595 distinct configurations were generated across all sites and surfaces.

Due to the computational expense of evaluating this large number of configurations via DFT, we employed a machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP) framework to pre-screen them efficiently. Specifically, we adopted the Crystal Hamiltonian Graph Neural Network (CHGNet)34, an open-source MLIP pre-trained primarily on relaxed bulk structures. However, since such models are typically less accurate for surface and adsorbate systems, we fine-tuned the CHGNet model using over 1000 additional DFT data points generated from H2 and OH* adsorption configurations. The composition and distribution of the fine-tuning dataset are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. The CHGNet model was fine-tuned on this dataset, with training conducted using mean-squared-error loss to simultaneously optimize energy, forces, stress, and magnetic moments. Loss weights were kept at 1.0, 1.0, 0.1, and 0.1, for energy, forces, stress, and magnetic moments, respectively. The dataset was randomly split into 70% training, 20% validation, and 10% testing subsets. Model optimization was carried out for 50 epochs using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10-2 and a cosine learning-rate scheduler65. A batch size of 15 was employed. To preserve the pretrained representations, all embedding and convolutional layers were frozen, allowing only the final task-specific layers to be updated. The best model was selected based on the lowest validation mean-absolute error, following the default behavior of the CHGNet training framework.

The fine-tuned CHGNet model exhibited improved accuracy compared to DFT, with total energy errors summarized in Supplementary Table S3. The MLIP enabled us to rapidly and reliably screen all 1595 configurations, achieving approximately 300× speedup relative to direct DFT. From these, the four lowest-energy configurations per site were selected for full DFT optimization to determine the most stable adsorption geometries and corresponding adsorption energies.

This approach allowed us to combine the efficiency of machine learning with the accuracy of DFT, enabling comprehensive exploration of surface adsorption behavior that would otherwise be computationally intractable.

DFT calculation settings

The DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)66 employing the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) form of generalized gradient approximation (GGA)67 in combination with the plane-wave projector-augmented-wave (PAW) method68. The valence electron configurations implemented for each element were as follows: 4p64d95s1 for Pd, 5d86s1 for Ir, 5d96s1 for Pt, 4p64d75s1 for Ru, 5d106s1 for Au, 4p64d85s1 for Rh, 1 s¹ for H, 2 s²2p⁴ for O. For bulk structures, both the atom positions and lattice parameters were optimized to eliminate internal stress. For surface structures, only the atom positions were relaxed. During the geometry optimization, a cutoff energy of 500 eV was used with the Methfessel–Paxton smearing method to describe the partial occupancies of orbitals with a width of 0.2 eV. Spin polarization was included in all calculations. The criteria for convergence of the electronic and ionic relaxation steps were set at an energy difference of 10-5 eV and a force smaller than 0.01 eV Å-1, respectively. A k-spacing of 0.03·2π/Å in the reciprocal space as per the Monkhorst–Pack grid69 was chosen to ensure a total energy shift with k-grids under 1 meV/atom. For further accurate Density of States (DOS) calculations, a smaller k-spacing of 0.01·2π/Å was used to ensure accuracy.

We calculated the adsorption energy (Ead) of H2 and OH* molecules on monometallic surfaces based on the formula:

where \({E}_{{total}}\) is the total energy of that when adsorbate and surface are both present. The \({E}_{{surface}}\) and \({E}_{{adsorbate}}\) are the energies of the surface and H2 and OH* molecules, respectively. As to the \({E}_{{OH}*}\), it can be obtained by70:

\({E}_{{adsorbate}}\) multiplied by two is because the adsorbate is adsorbed on both sides of the surface to eliminate the dipole moment in DFT calculations for slab models. The 1/2 factor in the equation is utilized to compute the adsorption energy of a single adsorbate.

To better capture the mechanistic aspects of HOR, we chose to evaluate the adsorption energy based on molecular H2 rather than single-atom hydrogen (H*). Previous DFT studies have also adopted molecular H2 as the adsorbate to investigate dissociation effects71,72. Therefore, including molecular H2 adsorption allows us to reflect both the adsorption and dissociation energetics, offering a more complete picture of surface reactivity relevant to HOR. Moreover, our calculations confirm that the adsorption energy of H2 is approximately twice that of H on the same surface, as shown in Supplementary Table S10, and the optimized geometries show clear evidence of dissociative adsorption on all surfaces except Au, which is consistent with experimental observations of its inertness toward H273. These results further validate our descriptor choice. The use of machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIP), fine-tuned by DFT, enabled us to efficiently explore a large number of H2 configurations, ensuring robustness and statistical reliability in identifying the most favorable adsorption structures.

To evaluate the sensitivity of our results to the choice of exchange–correlation functional, we also performed additional calculations using PBE-D2 and PBEsol functionals for selected surfaces (Ir, Ru, and Au). While variations in absolute values of adsorption energies and Fermi level positions were observed, the relative trends among the materials remained consistent across all tested functionals (see Supplementary Fig. S31). These results indicate that the key conclusions drawn in this work are not significantly affected by the specific choice of functional, thus confirming the robustness of our predictions.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are included within the main text and the Supplementary Information files. All the raw data of this manuscript are also available from the corresponding author upon request. All the machine learning data are available at the GitHub page (https://github.com/enkmsc/Source_data_bimetal). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Durst, J. et al. New insights into the electrochemical hydrogen oxidation and evolution reaction mechanism. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 2255–2260 (2014).

Sheng, W., Gasteiger, H. A. & Shao, Y. Hydrogen oxidation and evolution reaction kinetics on platinum: acid vs alkaline electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, B1529 (2010).

Sheng, W. et al. Correlating hydrogen oxidation and evolution activity on platinum at different pH with measured hydrogen binding energy. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–6 (2015).

Cong, Y., Yi, B. & Song, Y. Hydrogen oxidation reaction in alkaline media: from mechanism to recent electrocatalysts. Nano Energy 44, 288–303 (2018).

Mu, X., Liu, S., Chen, L. & Mu, S. Alkaline hydrogen oxidation reaction catalysts: insight into catalytic mechanisms, classification, activity regulation and challenges. Small Struct. 4, 2200281 (2023).

Yao, Z.-C. et al. Electrocatalytic hydrogen oxidation in alkaline media: from mechanistic insights to catalyst design. ACS Nano 16, 5153–5183 (2022).

Davydova, E. S. et al. Electrocatalysts for hydrogen oxidation reaction in alkaline electrolytes. ACS Catal. 8, 6665–6690 (2018).

Durst, J. et al. Hydrogen oxidation and evolution reaction (HOR/HER) on Pt electrodes in acid vs. alkaline electrolytes: mechanism, activity and particle size effects. ECS Trans. 64, 1069 (2014).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Trends in the exchange current for hydrogen evolution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, J23 (2005).

Trasatti, S. Work function, electronegativity, and electrochemical behaviour of metals: III. Electrolytic hydrogen evolution in acid solutions. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interf. Electrochem. 39, 163–184 (1972).

Ishikawa, K. et al. Enhancement of alkaline hydrogen oxidation reaction of Ru–Ir alloy nanoparticles through bifunctional mechanism on Ru–Ir pair site. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 22771–22777 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Experimental proof of the bifunctional mechanism for the hydrogen oxidation in alkaline media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 15594–15598 (2017).

Strmcnik, D. et al. Improving the hydrogen oxidation reaction rate by promotion of hydroxyl adsorption. Nat. Chem. 5, 300–306 (2013).

Xing, Y.-F. et al. Bifunctional mechanism of hydrogen oxidation reaction on atomic level tailored-Ru@Pt core-shell nanoparticles with tunable Pt layers. J. Electroanal. Chem. 872, 114348 (2020).

An, L., Zhao, X., Zhao, T. & Wang, D. Atomic-level insight into reasonable design of metal-based catalysts for hydrogen oxidation in alkaline electrolytes. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 2620–2638 (2021).

Men, Y. et al. Oxygen-inserted top-surface layers of Ni for boosting alkaline hydrogen oxidation electrocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 12661–12672 (2022).

Marković, N., Grgur, B. & Ross, P. N. Temperature-dependent hydrogen electrochemistry on platinum low-index single-crystal surfaces in acid solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 5405–5413 (1997).

Markovića, N. M., Sarraf, S. T., Gasteiger, H. A. & Ross, P. N. Hydrogen electrochemistry on platinum low-index single-crystal surfaces in alkaline solution. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 92, 3719–3725 (1996).

Li, Y. et al. Boosting hydrogen oxidation performance of phase-engineered Ni electrocatalyst under alkaline media. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 3682–3689 (2022).

Qin, X. et al. The role of Ru in improving the activity of Pd toward hydrogen evolution and oxidation reactions in alkaline solutions. ACS Catal. 9, 9614–9621 (2019).

Qiu, Y. et al. BCC-phased PdCu alloy as a highly active electrocatalyst for hydrogen oxidation in alkaline electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 16580–16588 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Engineering the near-surface of PtRu3 nanoparticles to improve hydrogen oxidation activity in alkaline electrolyte. Small 17, 2006698 (2021).

Lin, X.-M. et al. In situ probe of the hydrogen oxidation reaction intermediates on PtRu a bimetallic catalyst surface by core-shell nanoparticle-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 22, 5544–5552 (2022).

Lu, S. & Zhuang, Z. Investigating the influences of the adsorbed species on catalytic activity for hydrogen oxidation reaction in alkaline electrolyte. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5156–5163 (2017).

Qin, S. et al. Ternary nickel-tungsten-copper alloy rivals platinum for catalyzing alkaline hydrogen oxidation. Nat. Commun. 12, 2686 (2021).

Wang, H. & Abruña, H. D. IrPdRu/C as H2 oxidation catalysts for alkaline fuel cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 6807–6810 (2017).

Zhan, C. et al. Subnanometer high-entropy alloy nanowires enable remarkable hydrogen oxidation catalysis. Nat. Commun. 12, 6261 (2021).

Huang, M., Yang, H., Xia, X. & Peng, C. Highly active and robust Ir-Ru electrocatalyst for alkaline HER/HOR: combined electronic and oxophilic effect. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 358, 124422 (2024).

Huang, Z. et al. Implanting oxophilic metal in PtRu nanowires for hydrogen oxidation catalysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 1097 (2024).

Ohyama, J., Kumada, D. & Satsuma, A. Improved hydrogen oxidation reaction under alkaline conditions by ruthenium-iridium alloyed nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 15980–15985 (2016).

De Lile, J. R. et al. First principles study of Ir3Ru, IrRu and IrRu3 catalysts for hydrogen oxidation reaction: effect of surface modification and ruthenium content. Appl. Surf. Sci. 545, 149002 (2021).

Hamo, E. R. et al. Carbide-supported PtRu catalysts for hydrogen oxidation reaction in alkaline electrolyte. ACS Catal. 11, 932–947 (2021).

Yang, F., Tian, X., Luo, W. & Feng, L. Alkaline hydrogen oxidation reaction on Ni-based electrocatalysts: from mechanistic study to material development. Coord. Chem. Rev. 478, 214980 (2023).

Deng, B. et al. CHGNet as a pretrained universal neural network potential for charge-informed atomistic modelling. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 1031–1041 (2023).

Kayode, G. O. & Montemore, M. M. Factors controlling oxophilicity and carbophilicity of transition metals and main group metals. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 22325–22333 (2021).