Abstract

BCL-xL promotes cell survival by binding BH3-only initiators through its hydrophobic groove. Combining resonance energy transfer assays and molecular dynamics simulations, we unravel that membrane anchoring of BCL-xL via its tail anchor selectively advantages binding to membrane-anchored PUMA initiator over BH3 mimetic ligands of the groove. This is due to the combined allosteric effect on BH3-in-groove binding of BCL-xL and PUMA tail anchors. Moreover, doubly anchored PUMA / BCL-xL complexes recruit endogenous BAX, which favors their antagonism by BH3 mimetics. BAX’s tail anchor alone is sufficient to enhance BH3 mimetics-induced death in cells expressing PUMA / BCL-xL. Our work supports a model in which the survival function of BCL-xL is regulated by a complex interplay between its tail anchor and those of its interacting partners. This enables both resistance to pharmacological inhibitors and modulation by BAX, which functions as a crucial feedback disruptor of the BCL-xL network.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

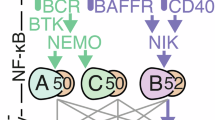

BCL-2 family proteins regulate mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and subsequent cell death. They comprise three subgroups: guardians (BCL-xL, BCL-2, MCL-1), which sequester executioners (BAX and BAK), capable of forming pores leading to MOMP, and initiators (BH3-only proteins), which inhibit guardians and activate executioners1. The structure of the BH3-binding interface of BCL-xL, conserved in anti-MOMP members (guardians), revealed that the BH3 domain of pro-MOMP counterparts (executioners and initiators) engages a canonical hydrophobic binding groove of the guardians2. These structural insights enabled the development of BH3 mimetics (BH3m), small molecules that competitively and selectively occupy the groove and offer substantial therapeutic potential in oncology3. Optimizing these compounds is essential, as they exhibit dose-limiting side effects and can lead to suboptimal responses related to partial MOMP, potentially generating persister cells4.

Understanding BH3m action requires deciphering how guardians engage intracellular interactions within intact cells. Their affinity for initiators or executioners depends on their location and abundance. Intracellular mobility of BCL-xL increases upon interaction with BAX (less with BAK), but decreases upon interactions with initiators or non-family proteins5,6,7,8. This interaction network is also highly dynamic9. For instance, BH3m-induced release of pro-MOMP factors from BCL-xL can be offset by MCL-1 sequestration, promoting cell survival10. Consequently, evaluating cell death may not directly reflect BH3m’s antagonistic disruption of guardian interactions. Moreover, the occurrence of BCL-2 interactions at subcellular membranes adds to their complexity11. It is thus important to use methods preserving cellular integrity to compare interactions between full-length proteins and to evaluate BCL-2 network assembly dynamics. BRET/FRET (Bioluminescence/Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer) studies in live cells have revealed that BCL-xL responses to BH3m vary with the bound pro-apoptotic ligand, differing from cell-free assays12,13,14. BCL-2 family interactions at subcellular membranes enhance affinity and modulate the hierarchy of binding partners15,16. Most members of the BCL-2 family harbor a C-terminal hydrophobic α-helix (hereinafter named tail anchor, TA), which allows insertion into OMM or ER membrane17,18. TAs are required for optimal pro-MOMP activity of executioners/initiators and support the guardian’s anti-MOMP activity16,19. BCL-xL TA also mediates retrotranslocation of executioners and allosteric regulation of initiator for BAX activation20,21. Recent studies indicate that TAs interactions among BCL-2 family proteins help regulate apoptosis6,19,21,22,23. The BCL-xL TA determines the interaction hierarchy of membrane-anchored BCL-2 family members24. Moreover, we showed that BCL-2/BCL-xL membrane anchoring limits the BH3m antagonism, but the underlying mechanism had remained mostly uncharacterized so far12.

One limitation hindering a comprehensive understanding of how these proteins regulate MOMP is the lack of structural data for BCL-2 family complexes in the subcellular membrane. Cellular analysis of higher-order complexes with BCL-xL or MCL-1 challenges the notion that guardians control pro-MOMP partners solely by forming heterodimers20,25. Moreover, the dynamic assembly of the BCL-xL complex involves allosteric regulation, wherein distant modifications induce conformational changes that modulate the protein’s activity. For instance, BCL-xL allosterically controls BAX activation, p53 or initiator sequestration20,26. Binding initiators, like PUMA or BIM, which are intrinsically disordered, induces their BH3 domain to adopt an amphipathic α-helix, and its helical stability contributes to affinity27,28. Structural and molecular dynamics (MD) studies also highlighted high conformational diversity in BCL-xL, with BH3 peptides engagement inducing significant conformational changes in α-helices, particularly at the BH3-in-groove interface2,29. Its hydrophobic binding groove represents a so-called cryptic binding site of remarkable flexibility, which can be transiently exposed when unbound30, but that turns into a stably open binding site with different conformations upon BH3 domain or mimetic engagement, according to an induced-fit mechanism31,32. Binding of the PUMABH3 peptide significantly alters BCL-xL conformation, α2 and α3 becoming highly disordered with potential functional consequences33. While membrane anchoring may constrain conformational dynamics during protein assembly, its biological consequences remain mostly unexplored. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations help investigate these conformational dynamics at binding interfaces, which are difficult to study experimentally34. In particular, these studies revealed structural disparities between soluble and membrane-anchored BCL-xL, as well as the dynamics of BH3-in-groove positioning concerning the membrane35,36. MD simulations also enabled energetic analysis, which highlighted other determinants within the BCL-2 family interaction network37.

Based on these premises and incognita, we herein investigated how BCL-xL TA modulates protein binding in cells. We evaluated BRET dose-response between various initiators and BCL-xL variants and performed biochemical and proteomic analysis of BCL-xL complexes. MD simulations and MM/GBSA (Molecular Mechanics with Generalized Born and Surface Area) modeling of membrane-bound BCL-xL complexes were performed to infer the influence of TA on binding. Through this unprecedentedly comprehensive description of the interplay between BCL-2 proteins TAs and BH3 binding, we show that the former allosterically restrict BH3-mediated antagonism of the latter and subject membrane-anchored BCL-xL to negative feedback by the BAX executioner.

Result

In cell, BCL-xL binds to BH3 domains via the canonical mode

We investigated whether the robustness of certain BCL-xL interactions with BIM and PUMA in response to BH3m antagonism in a whole cell context is due to a binding mode that is mechanistically distinct from the canonical one. We investigated by BRET assays interactions between full-length BCL-xL used as an acceptor (YBCL-xL fused to Yellow Fluorescent Protein, indicated by a subscripted Y) with a range of 36 mer peptides comprising the BH3 domains of PUMA, BIM, and tBID used as donors (RPUMABH3, RBIMBH3, and RBIDBH3 fused to Renilla Luciferase, indicated by a subscripted R) (Supplementary Table 1). Specificities of interaction were validated with BRET donor saturation and mutations in BH3 domain (Supplementary Fig. 1a and description). Notably, we mutated key residues in the BH3 domains (BIM 2A, tBID 3A, PUMA 3A; Supplementary Table 1), which abolished their specific binding to BCL-xL in BRET assays (Fig. 1a). The BCL-xL-specific BH3m compounds (WEHI-539, A-11555463, A-1331852) exhibited dose-dependent antagonism of BH3 domain/BCL-xL interactions (Fig. 1b). BH3m antagonism across complexes was assessed by statistical analysis of area under the curve differences (see Supplementary Figs.). The relative efficacy of the compounds correlated with their published affinities for the BCL-xL BH3-binding pocket (Supplementary Fig. 1a)14,38,39. Thus, when BH3 domains are excised from the context of the whole proteins, they bind to BCL-xL groove in a canonical manner. This implies that structure-activity relationships of the BH3-binding pocket of BCL-xL are comparable in cell-free assays or in intact cells, and that BH3m occupy this pocket in similar manners regardless of contexts.

a Involvement of hydrophobic amino acids H2, H4, and conserved ASP of PUMA, BIM, and tBID BH3 domains in binding of BCL-xL. BRET donor saturation assays were conducted using RBH3 domain (empty disk mark, dot line), both fused to RLuc, and YBCL-xL fused to YFP in MCF-7 cells. The variant with ALA substitutions (cross mark, dash line) (Supplementary Table 1) was compared to the wild-type variant. Data were fitted with a nonlinear regression equation assuming a single binding site using GraphPad Prism version 8 for macOS. The data presented are representative of at least two independent experiments. b Dose-response analysis of three BH3m (WEHI-539, A-1155463, and A-1331852) selectively antagonizing YBCL-xL, interacting with either initiator or its BH3 domain alone fused to RLuc in MCF-7 cells. Each BRET signal is normalized to the untreated condition (100%). The graphs include data points from at least three independent replicates. Some of the marks may be superimposed on the graph. The pictograms used to represent the complexes under investigation are shown in Fig. 2a. All data were fitted using an equation: [Inhibitor] vs. response—Variable slope using GraphPad Prism version 8 for macOS. Area under the curve (AUC) values were calculated from the dose-response curves to quantify the overall response to BH3 mimetic treatment across different complexes. A lower AUC indicates greater sensitivity to the treatment. Source data are available in the Source Data file. c Involvement of hydrophobic amino acids H2, H4 and conserved ASP of PUMA, BIM, and tBID in binding of BCL-xL. BRET donor saturation assays were conducted using RBH3-only initiator (full disk mark, full line) and YBCL-xL in MCF-7 cells. The variant with ALA substitutions (cross mark, dash line) (Supplementary Table 1) was compared to the wild-type variant. The representation follows the description provided in Fig. 1a. The data presented are representative of at least two independent experiments.

BH3 domain is a non-unique determinant for initiator/BCL-xL interaction

In addition to our studies with the BCL-xL variant carrying a dysfunctional groove12, multiple lines of evidence further argued that whole-cell complexes with full-length executioners depend, albeit not solely, on BCL-xL’s canonical BH3-binding site. Firstly, substitutions in the BH3 domain (Supplementary Table 1) impact the saturation curve, although this effect is less pronounced for PUMA 3A and BIM 2A compared to their BH3 domain alone (Fig. 1c). Secondly, BRET assays showed that PUMA or BIM interactions with BCL-xL were antagonized by the BH3m A-1155463 or A-1331852 (Fig. 1b), even though the concentrations required were much higher than those required to displace interactions with BH3 domains alone. These compounds more effectively antagonized BAD and tBID interactions with BCL-xL than WEHI-539 (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1a). To validate assay specificity, we confirmed that ABT-199 and S-63845 did not affect BAD/BCL-xL interactions, while effectively inhibiting BAD/BCL-2 and BAK/MCL-1 interactions, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). Thus, BH3m effects in intact cells reflect their affinities and selectivities for BCL-xL BH3-in-groove interfaces determined in cell-free assays14,40. Thirdly, we substituted conserved Gly or Ala residues (A145V, G96V, G35V) to alter BH3 helix flexibility27, modestly affecting BRET signals with a slight, inconsistent affinity increase (Supplementary Fig. 1d), while dose-response analyses showed enhanced WEHI-539 sensitivity (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

Overall, these experiments are consistent with evidence from the BH3 peptides, indicating that the formation of BCL-xL complexes with initiators in whole cells is guided by, although not exclusively, BH3 binding, in a manner dependent on the α helix structure and its composition in amino acids. However, the robustness of PUMA or BIM interactions with BCL-xL to BH3m antagonism, compared to the BH3 domain alone, suggests that additional molecular features endow these initiator proteins with a competitive advantage over BH3m for binding to BCL-xL.

TAs cooperate to form BH3m-resistant complexes

PUMA and BIM complexes with BCL-xL were consistently more resistant to BH3m than tBID or BAD complexes (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1b). tBID showed greater sensitivity than BAD, compared to previous reports14,41, likely due to species differences (human vs. mouse) affecting BRET-detected complex stability (Supplementary Fig. 1f).

We focused on PUMA/BCL-xL interactions and searched for molecular features that might provide a competitive advantage to PUMA over BH3m. We designed a chimeric protein replacing the PUMABH3 domain with that of BID (PUMA-BIDBH3, Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 1), which interacts with BCL-xL most sensitively to BH3m. Unlike tBID, the domain-swapped chimera’s interaction with BCL-xL was resistant to WEHI-539 and strikingly less sensitive to A-1331852 (Figs. 1b, 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Thus, domains surrounding the PUMABH3 domain contribute to enforcing interaction with BCL-xL. Notably, the G145V substitution in PUMA-BIDBH3 resulted in WEHI-539 sensitivity, similar to tBID G35V (Supplementary Fig. 2b), indicating BH3 binding still contributes to chimera engagement. Deleting PUMA’s N-terminus (annotated dNPUMA and dNPUMA-BIDBH3) did not affect BH3m sensitivity, whereas removing its TA (annotated PUMAdC and PUMA-BIDBH3dC) increased BCL-xL complex susceptibility to BH3m (Supplementary Table 2; Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Fig. 2c, d). In HCT116 cells, BCL-xL antagonism by A-1331852 also differs between PUMA and tBID, in a PUMA TA-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 2e). These results show that PUMA TA confers a selective binding advantage to BCL-xL compared with BH3m. Of note, deleting BCL-xL’s TA (BCL-xLdC, Supplementary Table 2) had less impact on BH3m sensitivity of PUMAdC/BCL-xL than PUMA/BCL-xL, and did not affect interactions with isolated BH3 domains (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2f, g), highlighting cooperative TA function to promote robustness against BH3m-induced displacement.

a Schematic representation of different protein variants expressed in the cells for this study. BH3 domain of initiators and TA are indicated. The numbering indicates the amino acid position in the full-length protein. The pictograms used to describe the complexes evaluated in the BRET dose-responses analysis are displayed on the right. See Supplementary Table 1 for sequences. b Dose-response antagonism of YBCL-xL by WEHI-539, depending on the interaction with RPUMA-BH3BID variants in MCF-7 cells. The representation is as described in Fig. 1b. c Dose-response antagonism of YBCL-xL by A-1331852, depending on the interaction with RPUMA variants in MCF-7 cells. Note that for ease of comparison, the data for the response of the RPUMA/YBCL-xL complex shown in Fig. 1b have been reproduced. The representation is as described in Fig. 1b. d Dose-response antagonism of YBCL-xL and YBCL-xLdC by WEHI-539 interacting with RBH3 domains of initiators in MCF-7 cells. Note that for ease of comparison, the data for the responses of the RBH3 domain/YBCL-xL complexes shown in Fig. 1b have been reproduced. The representation is as described in Fig. 1b.

Membrane anchoring of PUMA and BCL-xL orients BH3 groove toward lipids

The TAs of PUMA and BCL-xL mediate their stable, alkali-resistant membrane anchoring, targeting to mitochondrial and ER membranes. Consistently, a PUMA variant lacking this domain (PUMAdC, fused to mCherry; mCPUMA) displayed ubiquitous localization upon expression in MCF-7 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2h). As expected, I175E and L178E substitutions within the PUMA TA disrupted subcellular membrane targeting (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 2h)42. The A221R substitution, which loosens BCL-xL membrane anchoring, increased complex sensitivity to BH3m antagonism12. Similarly, I175E and L178E substitutions in PUMA or PUMA-BIDBH3 also enhanced sensitivity to BH3m (Fig. 2b, c), and correlated with enhanced MOMP (Supplementary Fig. 2i). Of note, cells expressing RPUMA I175E L178E/YBCL-xL or RPUMA/YBCL-xLdC complexes also displayed significantly higher spontaneous cytochrome C release. This argues that the membrane anchoring property of PUMA TA contributes to resistance of PUMA/BCL-xL complexes to BH3m antagonism.

To investigate how BCL-xL and PUMA membrane anchoring influences BH3-dependent complex formation, we conducted MD simulations. Two model conformations, BCL-xL bound to PUMABH3 domain or dNPUMA, both anchored in a palmitoyl oleyl phosphatidylcholine (POPC) membrane, were constructed and compared. As the N-terminal region of PUMA’s BH3 domain did not affect BH3m antagonism (Fig. 2b, c), we modeled PUMA from its BH3 domain to the C-terminus (130–193). In both models, the BH3 domain was nestled between BCL-xL’s hydrophobic groove and the membrane’s upper layer, with a similar initial orientation relative to the membrane (Fig. 3a). The PUMA linker, bridging its TA to the BH3 domain, was positioned beneath the globular domain of BCL-xL. The MD simulations of PUMABH3 or dNPUMA with BCL-xL over a period of 2000 ns reveal distinct conformational dynamics (Supplementary Movies 1 and 2). In both simulations, PUMA’s BH3 domain always remained tightly bound, while BCL-xL’s globular part adopted different orientations relative to the membrane (Fig. 3a). The PUMABH3/BCL-xL complex showed greater mobility, causing the BH3 domain to lose membrane contact and become more solvent-exposed (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Similar dynamics were also observed in replicate simulations (Supplementary Movies 3 and 4) and in simulations with different membrane system size and ion concentrations (Supplementary Movies 5 and 6). To further characterize these dynamics, we computed roll and tilt angles to describe BCL-xL groove orientation relative to the membrane (Fig. 3b). Net differences were observed with or without the PUMA TA: in dNPUMA/BCL-xL, roll and tilt angles remained globally stable, whereas in PUMABH3/BCL-xL, a drastic change around 500–600 ns coincided with BH3 domain exposure to solvent. After 600 ns, PUMABH3/BCL-xL showed tilt and roll angles of 76° ± 8 and 114° ± 11, compared to 132° ± 7 and 96° ± 5 for dNPUMA/BCL-xL (over the 600–2000 ns interval), indicating that PUMABH3 anchoring, via its TA, alters BH3-in-groove orientation relative to the membrane.

a Representative snapshots from the supplementary Movies 1 and 2 illustrating the results of molecular dynamics simulations over time performed to study the behavior of BCL-xL complexes interacting with PUMABH3 or dNPUMA. Phosphatidyl choline headgroups are represented in van der Waals representation and lipid tails are displayed in blue lines to provide a clear view of TA. The helical structure of TA is depicted in Cartoon representation. The simulations were carried out for 2 μs. At t = 0, the initial orientations of the PUMABH3/BCL-xL and dNPUMA/BCL-xL complexes are depicted. During the simulation, the PUMABH3/BCL-xL globular part moves away from the membrane, while this phenomenon was less pronounced for the dNPUMA/BCL-xL complex. b Dynamics of the globular part of the PUMABH3/BCL-xL and dNPUMA/BCL-xL complexes relative to the membrane over a 2000 ns timespan. BCL-xL tilt was defined as the angle between the BCL-xL α5 helix and the membrane plane (left panel). BCL-xL roll was defined as the angle between a plane formed by BCL-xL α5 and α6 helices and the membrane plane (right panel).

We then focused on the dynamic conformation of BCL-xL TA alone (in PUMABH3/BCL-xL complex) or near PUMA TA (in dNPUMA/BCL-xL complex). To avoid modeling bias, we first determined the initial TA orientation using protein-protein docking methods. In the dNPUMA/BCL-xL complex, both TAs were predicted to adopt an almost parallel orientation with N-terminal sides close together (Supplementary Fig. 3b), without specific residue pairs driving the interaction. We first analyzed BCL-xL’s α9 helix (TA) geometry43: its bend remained stable without PUMA TA but increased in its presence, suggesting a constraining effect (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Upon assembly and virtually heating to room temperature, the PUMA TA helix partially unfolded at the start of the simulation, a kink formed at 200 ns and was subsequently adopted by the BCL-xL TA at 825 ns (Supplementary Fig. 3b and Supplementary Movie 7). Once this double-kinked conformation formed, both TAs remained close, keeping the BH3-in-groove binding interface oriented toward the membrane. In contrast, in the PUMABH3/BCL-xL complex, the helix stayed mostly straight (Supplementary Movie 1), allowing greater freedom of movement for the globular part and BH3-in-groove to be away from the membrane. Remarkably, as the BCL-xL TA becomes more orthogonal to the membrane, the BH3-in-groove interface moves away from it, subtly in the dNPUMA/BCL-xL complex (600 ns) and more stably in the PUMABH3/BCL-xL complex. Overall, our MD studies indicate that the PUMA TA confines the BH3-in-groove interface to the lipid membrane by restricting the dynamics of the BCL-xL TA.

Double tail anchoring allosterically regulates the BH3-in-groove interface

To determine whether and how BCL-xL and PUMA TAs might regulate BH3 binding, we performed interaction energy profiling. We calculated the free energy of ligand binding to proteins using the MM/GBSA solvation method44. Our MD trajectories enabled per-residue decomposition of binding enthalpies for dNPUMA or PUMABH3 with BCL-xL, including membrane anchoring, considering residues with energies below −1.5 kcal/mol as significant contributors. We mapped mean per-energy contributions for the 600–2000 ns interval of stimulation onto surface complexes and primary structures of BCL-xL and its ligand PUMABH3 or dNPUMA, when the complexes were most conformationally stable.

As expected, the PUMABH3 binding to BCL-xL primarily involved residues lining the BCL-xL groove (α4 and α5 helices on one side, α2 and α3 helices on the other—Supplementary Fig. 4a), where hydrophobic residues H1–H4 (I137, L141, M144, L148) engage in van der Waals contacts (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Additionally, charged residues E129 and R139 in BCL-xL, along with R135, R142, D146 in PUMABH3 domain, also contribute to the interaction through canonical electrostatic bonds (Fig. 4a)27,37. Notably, residues F97, E129, L130, N136, and R139, previously identified as important for PUMABH3 peptide binding under soluble conditions in vitro, also emerge as significant contributors in our MM/GBSA calculations45. Therefore, membrane anchoring of BCL-xL per se does not drastically alter the BH3-in-groove interface.

a PUMABH3/BCL-xL (upper panels) and dNPUMA/BCL-xL (bottom panels) complexes structures: representative structures (t = 1000 ns) are colored according to the average per-residue energy contributions, calculated using MM/GBSA from their molecular dynamic trajectories. Only residues with significant binding energy contributions (below −1.5 kcal/mol or above 1.5 kcal/mol) are displayed and annotated according to the color index. Specific residues within the BH3-in-groove of BCL-xL interacting with PUMABH3 or dNPUMA are annotated in bold with a thick arrow (middle and right panels). The underlying numerical values are given in Supplementary Table 3. The C-terminal domains are omitted at the bottom for better readability. b Dose-response antagonism by A-1331852 of YBCL-xL wt, E96A, F105A, and E129A variants complexed with either RPUMA or RPUMABH3 in MCF-7 cells. Note that for ease of comparison, the data for the response of the RPUMA/YBCL-xL and RPUMABH3/YBCL-xL complex shown in Fig. 1b have been reproduced. The representation is as described in Fig. 1b. c dNPUMA/BCL-xL E96A complex structure: average per-residue energy contributions, calculated using MM/GBSA from the 1000 ns trajectory, are projected onto the structure of dNPUMA/BCL-xL. Only residues with significant binding energy contributions (below −1.5 kcal/mol or above 1.5 kcal/mol) are displayed and annotated according to the color index. The underlying numerical values are given in Supplementary Table 3. Only residues with significant binding energy contributions (below −1.5 kcal/mol or above 1.5 kcal/mol) are displayed and annotated according to the color index. Specific residues within the BH3-in-groove of BCL-xL interacting with PUMABH3 or dNPUMA are annotated in bold with a thick arrow (middle and right panels). The underlying numerical values are given in Supplementary Table 3. The C-terminal domains are omitted at the bottom for better readability.

More BCL-xL residues contribute to dNPUMA binding (21 vs. 14), yielding a higher overall binding energy (−134 kcal/mol) than for PUMABH3 (−80 kcal/mol). Both complexes engage the same key regions (BCL-xL α2–α5 helices and the PUMA BH3 domain), but dNPUMA binding also involves additional residues from both protein’s TAs (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). BCL-xL residues (L108, I114, Q125, L130, D133, R139), which contribute to PUMABH3 binding45, are not involved in the dNPUMA interaction (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Instead, BCL-xL residues L99, Y101, F105, and T118 in the globular domain specifically engage dNPUMA, expanding the binding interface. Conversely, the relative contribution of specific BCL-xL residues (E96, F97, S122, V126, N136, W137) and BH3 residues (W133, R142, M144, A145, L148) varies depending on whether the PUMA TA is present or not (Fig. 4a). To ensure that conclusions were drawn independently from the choice of MM-GBSA parameters, we evaluated the binding energies in relative terms rather than absolute values. The contribution of BCL-xL helices to binding depends on PUMA membrane anchoring: with PUMABH3, α2 (12% of the overall binding energy of BCL-xL), α3 (9%), α4 (47%), α5 (16%); with dNPUMA, α2 (21%), α3 (13%), α4 (20%), α5 (4%), and α9 (18%). As previously reported, conserved BCL-xL residues account for >50% of binding energy with PUMABH3 but only 26% with dNPUMA (Supplementary Fig. 4c)37. Notably, BCL-xL residues that bind A-1155463 and A-1331852 BH3m, exhibit higher binding energy with dNPUMA compared to PUMABH3 (Supplementary Fig. 4d). This argues that an allosteric regulation of the BH3-in-groove interface by the TAs of BCL-xL and PUMA underlies the differences in competitive BH3m inhibition efficacy observed in our cellular models (Fig. 1b).

These results suggest that certain amino acids may selectively influence the PUMA/BCL-xL binding interface in a PUMA TA-dependent manner. We focused on residues E96, F105, and E129 of BCL-xL, which exhibit the highest binding energy with dNPUMA (Fig. 4a). We first analyzed the antagonism of BCL-xL variants carrying alanine substitutions using A-1331852 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4e). While the E129A mutation did not affect the response, F105A conferred resistance, and E96A enhanced sensitivity. Dose-response analysis with the PUMABH3 ligand revealed that the F105A effect was independent of PUMA TA, likely reflecting its direct critical role in binding BH3m ligand46. In contrast, the effect of the E96A mutation was PUMA TA dependent. Comparison of MD simulations of the three BCL-xL variants showed that the E96A substitution substantially alters BCL-xL’s membrane orientation, shifting its roll toward the membrane and displacing the engaged BH3 domain away from it (Supplementary Fig. 4f). MM/GBSA analysis further indicated that loss of E96 modulates the binding interface between the BH3 domain and the BCL-xL groove, by engaging alternative residues (D95 and Q125) (Fig. 4c). This highlights the strong connection between BCL-xL’s membrane orientation and the effectiveness of BH3 mimetic antagonism when bound to a membrane-anchored BH3 ligand.

Overall, our analysis indicates that membrane anchoring of PUMA generates distinct BCL-xL binding sites and alters both the dynamics of the interface and its orientation relative to the membrane.

Double tail anchoring promotes higher-order complex organization

We investigated how BCL-xL binding to membrane-anchored PUMA influences localization and interactome using HCT116 and MCF-7 cells expressing bicistronic constructs (using P2A «self-cleaving» peptide sequence47) for a flagged PUMA with (FPUMA) or without TA (or FPUMAdC) and GBCL-xL, ensuring comparable expression (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 5a). GBCL-xL–only cells served as controls.

a Evaluation of BCL-2 family proteins expression in GBCL-xL, FPUMA/GBCL-xL and FPUMAdC/GBCL-xL wild-type cells and FPUMA/GBCL-xL baxCRISPR−/−bak1 CRISPR−/− HCT116 cells. The blots are representative of four independent experiments. b Subcellular fractionation of BCL-2 family members in heavy membranes (HM) and cytosol (C) from HCT116 cells. HSP70 and COXIV serve as controls for cytosolic and mitochondrial markers, respectively. The blots are representative of five independent experiments, except for MCL-1 (n = 3). c Analysis of complexes involving GBCL-xL, FPUMA, or MCL-1 by blue-native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of heavy membranes extracted from GBCL-xL, FPUMA/GBCL-xL, and FPUMAdC/GBCL-xL HCT116 cells. The SDHA protein serves as a loading control. On the right side of the BN-PAGE blots, line scan analyses illustrate the migration profiles and relative intensities of the GBCL-cL, FPUMA complexes, as well as the SDHA protein. The presented blots are representative of three independent experiments. d Comparative interactome analysis of GBCL-xL with or without FPUMA in HCT116 cells. Venn diagram shows shared and unique interactants; red and blue panels list interactants identified under a single cell line. e Volcano plot displays fold changes in the amount of detected interactants of GBCL-xL with and without FPUMA: red/green denote significantly up- and down-interacting proteins, respectively, gray for non-significant changes (two-sided t-test). Data are the mean of four independent IP experiments with mass spectrometry. Mitochondrial and ER proteins are consistently highlighted in yellow and green. f Kinetics of single cell apoptosis induction in GBCL-xL, FPUMA/GBCL-xL, and FPUMAdC/GBCL-xL, treated with a concentration range 1:4 serial dilution of A-1331852 (0–10 μM, black curves) with and without S-63845 (0.5 μM, brown curves). Involvement of BAX and BAK were evaluated in FPUMA/GBCL-xL HCT116 cells. Apoptosis was assessed by AnnexinV staining over 13 h using live cell imaging with the Incucyte S3 imager. The data presented are representative of five independent experiments. All antibodies specifically target the indicated proteins, except FPUMA and FPUMAdC, detected via anti-FLAG antibody. Uncropped blots are available in the Source Data file.

Cellular fractionation revealed that GBCL-xL expressed alone was distributed between cytosol and heavy membrane fractions, whereas co-expression with FPUMA led to both proteins to localize almost exclusively in the heavy membrane fraction (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). Co-expression of FPUMAdC, which was present in both soluble and membrane fractions, failed to increase GBCL-xL membrane localization, indicating that FPUMA’s TA drives GBCL-xL enrichment at membranes. We performed native gel electrophoresis BN-PAGE to compare protein complexes in membrane fractions. Membranous GBCL-xL expressed alone migrated with an apparent molecular weight corresponding to that of monomers, whereas with FPUMA, heterodimers and also higher-order complexes were formed (Fig.5c and Supplementary Fig. 5d). In contrast, FPUMAdC co-expression yielded only heterodimers, indicating that FPUMA anchoring is required for higher-order complex organization.

To further investigate BCL-xL complexes, we immunoprecipitated GBCL-xL from engineered HCT116 cell lysates with an anti-GFP antibody, followed by mass spectrometry–based identification and quantification of co-precipitated proteins. We dubbed as potentially aspecific binders and removed them from any further analysis: (i) proteins that we identified by mass spectrometry in parallel control assays (anti-GFP pull-downs from GFP cells); (ii) proteins identified in a CRAPome48 with a frequency of more than 15%. After applying this counter-selective filter, 71 and 84 proteins were identified as interactors in GBCL-xL and FPUMA/GBCL-xL HCT116 cells, respectively (with 62 in common, 9 and 22 specifically in GBCL-xL and FPUMA/ GBCL-xL cells, Fig. 5d). We identified the mitochondrial outer membranous proteins TOM40 and BID, in addition to vesicle and ER proteins, in GBCL-xL pull-downs only when FPUMA was coexpressed. Moreover, fold change analysis of the 62 shared interactants revealed that FPUMA co-expression enhanced interaction between GBCL-xL and 23 proteins (Fig. 5e), including the executioners BAX and BAK (investigated further below). A substantial number of these proteins were found to be mitochondrial or ER proteins according to gene ontology classifications (Supplementary Fig. 5e).

Altogether, these results argue that membrane-anchored FPUMA promotes GBCL-xL association with additional mitochondrial partners, forming complexes larger than FPUMA/GBCL-xL heterodimers.

BCL-xL BH3m antagonism fails independently of MCL-1 compensation

We explored how double anchoring affects cell fate regulation by FPUMA/GBCL-xL complexes under BH3m antagonism. Engineered HCT116 and MCF-7 cells were exposed to increasing doses of A-1331852, and cell death was monitored by annexin V live imaging and cytochrome C release by flow cytometry. Compared to GBCL-xL alone, FPUMA co-expression significantly sensitized cells to A-1331852, triggering death at lower doses and with faster kinetics at higher concentrations (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 5f). CRISPR double invalidation of BAX and BAK1 genes abrogated this response, confirming their executioner role (Supplementary Fig. 5g). Notably, FPUMAdC expression conferred even greater sensitivity than FPUMA (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 5f). Co-immunoprecipitation of GBCL-xL confirmed that the greater sensitivity of FPUMAdC versus FPUMA to A-1331852 correlated with more efficient displacement from GBCL-xL (Supplementary Fig. 5h, i). Thus, BH3m sensitivity measured by BRET and co-IP and cell death initiation in response to the compound are linked.

We investigated MCL-1’s role in FPUMA/GBCL-xL resistance. Endogenous MCL-1 levels were similarly elevated in FPUMA and FPUMAdC co-expressing cells versus GBCL-xL alone (Fig. 5a), possibly due to reduced proteasomal degradation upon PUMA-BH3 binding. Endogenous MCL-1 co-immunoprecipitated with FPUMA regardless of its TA (Supplementary Fig. 5h, i). Fractionation and BN-PAGE also showed MCL-1 localized to heavy membranes in higher-order complexes when FPUMA, but not FPUMAdC, was co-expressed with GBCL-xL (Fig. 5b, c). Cell death assays with 0.5 µM S-63845 highlighted synergy with A-1331852 in GBCL-xL–only cells (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 5j), confirming that MCL-1 compensates for BCL-xL antagonism by sequestering pro-MOMP factors. Strikingly, co-expression of FPUMA or FPUMAdC with GBCL-xL abolished the synergy with S-63845. FPUMA/GBCL-xL cells required higher A-1331852 doses and showed lower death than FPUMAdC/GBCL-xL cells, indicating that PUMA membrane anchoring limits BCL-xL antagonist–induced cell death, even when combined with MCL-1 antagonism.

BAX sensitizes doubly anchored PUMA/BCL-xL to BH3m antagonism by its TA

BCL-xL binding partners in the presence of PUMA may influence complex dynamics and BH3m response. We focused on BAX and BAK, which were enriched in GBCL-xL pull-downs with FPUMA (Fig. 5e). Proximity ligation assays (PLA) between endogenous BAX and GBCL-xL, combined with flow cytometry, quantified PLA signals and GBCL-xL (GFP) expression in single cells expressing FPUMA, FPUMAdC, or none (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Flow cytometry quantified BAX/GBCL-xL proximity events (marked by PLA fluorescent signals) and GBCL-xL levels (marked by GFP fluorescence) in single cells, revealing a positive correlation between PLA signals and GBCL-xL expression in both FPUMA-expressing and FPUMA-free populations (Supplementary description). However, FPUMA expression increased the mean intensity and reduced the distribution of PLA signals, an effect also observed with PUMAdC, likely due to BH3-mediated BAX activation (through conformational change and concomitant MOM translocation) (Supplementary Fig. 6a), and/or inhibition of its BCL-xL–dependent retrotranslocation49. Moreover, and most importantly, FPUMA-expressing cells consistently showed significantly higher BAX/GBCL-xL PLA signals than FPUMA-free cells expressing the same range of GBCL-xL levels (Fig. 6a). Thus, across the GBCL-xL expression spectrum, FPUMA increased the proportion of BAX molecules proximal to BCL-xL.

a Proximity ligation assay of BAX/GBCL-xL as a function of PUMA. HCT116 cells expressing either GBCL-xL alone or together with FPUMA were stained for BAX/GFP interaction. To ensure comparability, five gates with homogeneous GBCL-xL expression were defined, and PLA signal was analyzed in each rainbow-colored gate (see Supplementary description in Supplementary information). The graph illustrates violin plots of the PLA signal (RL1 med - neg: median value of RL1 corrected by the RL1 value of “no-antibody” control cells) within gates of GBCL-xL expression in three independent experiments. P values from two-sided unpaired Student’s t tests comparing the two cell lines are reported for each gate. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus control. Source data are available in the Source Data file. b–d Dose-response antagonism of YBCL-xL, YBCL-xLdC, YBCL-xL G138A proteins complexed with either RPUMA, RPUMA-BIDBH3, RtBID, RPUMAdC, as a function of BAX and BAK expression. A-1331852 BH3m antagonism of the indicated complexes is compared between wild-type and baxCRISPR−/− bak1 CRISPR−/− MCF-7 cells. Note that for ease of comparison, the data for the responses of the RPUMA/YBCL-xL, RtBID/YBCL-xL, RPUMAdC/YBCL-xL, RPUMA/YBCL-xLdC, RPUMA-BIDBH3/YBCL-xL complexes shown in Figs. 1b, 2c, and Supplementary Fig. 2f have been reproduced. The representation follows the description provided in Fig. 1b.

BN-PAGE of FPUMA/GBCL-xL cells with or without BAX/BAK showed that executioners are dispensable for forming high-molecular-weight FPUMA/GBCL-xL membrane complexes (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 5d). We then invalidated BAX and/or BAK1 genes by CRISPR in MCF-7 cells to investigate their consequence on BRET signals and their response to BH3m antagonism (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Double invalidation had no drastic effect on donor saturation assays of YBCL-xL interactions with either RPUMA, RtBID, RPUMA-BIDBH3 or RBIM, suggesting that endogenous BAX and BAK do not effectively compete with the donors for acceptor YBCL-xL binding. However, BAX loss, and to a lesser extent BAK, reduced BH3m antagonism of RPUMA/YBCL-xL, while double knockout abolished A-1331852 response. It also significantly reduced BH3m sensitivity of RPUMA-BIDBH3/YBCL-xL and RBIM/YBCL-xL, but not RtBID/YBCL-xL (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 6c–e). Moreover, BAX and BAK1 invalidation did not promote resistance to BH3m of RPUMAdC/BCL-xL or RPUMA/YBCL-xLdC BRET signals (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 6f). Of note, these results imply that low BH3m responses for PUMA and BIM BRET signals are not due to cell death related donor and/or acceptor loss. Thus, BAX and BAK interferences with PUMA/BCL-xL complexes, increase their sensitivity to displacement by BH3m, and it does so only for doubly anchored complexes.

Since BAX and BAK are recruited near BCL-xL upon PUMA co-expression, we sought for BCL-xL motifs potentially mediating this effect. Using the groove-defective BCL-xL G138A variant, which cannot bind BAX/BAK but retains interaction with PUMA and PUMA-BIDBH3 (Supplementary Fig. 6g)50,51, we probed canonical binding contributions to BH3m sensitivity. BAX/BAK1 loss resulted in decreased BH3m antagonism of PUMA/BCL-xL G138A and PUMA-BIDBH3/BCL-xL G138A (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 6h), indicating that their effects may rely on a BCL-xL interaction site outside the groove. This rules out competition with PUMA for binding to this site. BAX TA interacts with BCL-xL and its TA alone in biological membranes51,52. To test whether this noncanonical binding mediates BAX-dependent sensitization of doubly anchored complexes to BH3m, we first swapped BCL-xL’s TA with TOM20’s (Supplementary Table 2), which cannot interact with BCL-2 family TAs23. BAX/BAK loss did not affect BH3m response of PUMA/BCL-xL-CTOM20 BRET signals (Supplementary Fig. 7a), consistent with the requirement for BCL-xL TA/BAX TA interaction. In a second set of experiments, we replaced BCL-xL’s TA with BAX’s TA (Supplementary Table 2). The resulting chimeric protein was shown to robustly associate with the BAX TA52. The sensitivity to BH3m of BCL-xL-CBAX interaction with PUMA or PUMA-BIDBH3 was enhanced compared to that of BCL-xL (compare Figs. 6b and 7a) and lost when the BAX and BAK1 genes were invalidated (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 7b). This sensitization was also lost when BCL-xL-CBAX carried G222I A226I substitutions, which prevent BAX TA interaction (Supplementary Table 2; Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 7b). We note that no effect of this double substitution is observed in the BH3-mimetic dose-response of the complex with PUMAdC. Thus, modulating BCL-xL/BAX TA interactions only modifies BH3m sensitivity of doubly anchored PUMA/BCL-xL complexes.

a Dose-response antagonism of YBCL-xL-CBAX, YBCL-xL-CBAX G222I A226I chimeric proteins complexed with either RPUMA, RPUMA-BIDBH3, RtBID, RPUMAdC, as a function of BAX and BAK expression. A-1331852 BH3m antagonism of the indicated complexes is compared between wild-type and baxCRISPR−/− bak1 CRISPR−/− MCF-7 cells. The representation follows the description provided in Fig. 1b. b Evaluation of the interaction between MBCBAX and GBCL-xL expressed with FPUMA or FPUMAdC in HCT116 cells using the BirA in situ proximal biotinylation assay. Input and labeled (i.e., biotinylated) proteins isolated with biotin affinity beads were analyzed by Western blotting for GBCL-xL, FPUMA, and TOM20. All antibodies specifically target the indicated proteins, except FPUMA and FPUMAdC, detected via anti-FLAG antibody. The presented blots are representative of three independent experiments. Uncropped blots are available in the Source Data file. c Single cell apoptosis analysis in FPUMA/GBCL-xL and FPUMAdC/GBCL-xL HCT116 cells with or without expression of MBCBAX, treated with a concentration range 1:4 serial dilution of A-1331852 (0–10 μM). Apoptosis was analyzed over 13 h for AnnexinV staining by live cell imaging using the Incucyte S3 imager. The heatmap summarizes the Log2 ratio of the percentage of cell death in cells expressing MBCBAX compared to the control vector (pLVX). Data are mean of five independent experiments. Significant difference in overall kinetics were assessed using permutation-based two-sided p values, calculated with the comparegrowthcurve function from the statmod R package. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To investigate the impact of BAX TA on BH3m-induced cell death, we constitutively expressed BAX TA fused to the MYC-tagged biotin ligase BirA (MBCBAX) within HCT116 cells co-expressing PUMA/BCL-xL or PUMAdC/BCL-xL (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Biotinylation of GBCL-xL was observed (as judged by pull-down assays in Fig. 7b), indicating that the proximity between the BAX TA and BCL-xL19,23,52, is maintained when PUMA is co-expressed. No biotinylation of TOM20 and FPUMA, both of which are present at the mitochondrial membrane, was detected, suggesting the specificity of the interaction between GBCL-xL and BAX TA. Remarkably, expression of the BAX TA resulted in enhanced cell death rates upon BH3m treatment of PUMA/BCL-xL but not PUMAdC/BCL-xL cells (Fig. 7c).

Collectively, these results argue that BAX modulates BH3m sensitivity of doubly anchored PUMA/BCL-xL complexes through BAX TA/BCL-xL TA interactions.

Discussion

This study was motivated by the observation that some membrane-localized initiator/BCL-xL complexes resist BH3m antagonism12. We confirm that BH3-in-groove binding critically determines BCL-xL complex formation in cells, and reveal that it is allosterically modulated by partner TAs, endowing initiators with a competitive advantage over soluble BH3m. This interplay likely explains why membranes and BCL-xL TA bias interaction preferences24 and enhance membrane-anchored BCL-xL pro-survival activity1,9,18. As tBID is membrane-anchored within MOM and interacts with BCL-xL in a BH3m-sensitive manner, the mode of membrane insertion (rather than anchoring alone) may be key to BH3m antagonism resistance. BH3 helix binding to the cryptic BCL-xL site follows an induced-fit mechanism that stabilizes the groove31, highlighting the requirement to consider conformational dynamics. Our MD analysis confirms that the BH3-binding site is highly dynamic and can adopt alternative conformations. We unravel an allosteric effect of membrane anchoring on BH3 binding at three distinct coordinated levels (Fig. 8): (i) binding to membrane-anchored dNPUMA maintains towards the membrane the hydrophobic groove of BCL-xL, potentially constraining induced-fit BH3 binding; (ii) it adjusts BCL-xL’s TA within the membrane, with MD and MM/GBSA analysis indicating an influence BCL-xL TA’s topology and suggesting potential TA/TA interactions as part of an ancillary binding site to the groove, as proposed in the “double-bolt locks” model41,42; (iii) it alters BH3-in-groove engagement when both BCL-xL and PUMA are membrane-anchored. Binding energies comparisons with and without PUMA TA reveal changes in BCL-xL groove residues and in hydrophobic and charged BH3 domain residues. Notably, L148 shows distinct interactions, potentially due to dNPUMA’s TA enabling additional contacts with BCL-xL (Fig. 4a). Membrane anchoring thus supports a distinct BH3-in-groove conformation, reduces BH3m antagonism, and reshapes the importance of specific residues in doubly anchored complexes. Consequently, this allostery yields a BH3-in-groove conformation distinct from that used for BH3m design. We hypothesize that the allosteric interplay between BCL-xL and PUMA TAs guides BH3 positioning in the groove with E96 (outside the groove) playing a critical role, as its loss enhances BH3m sensitivity while altering BCL-xL’s membrane positioning and BH3 domain engagement.

The orientation of the BH3-binding interface towards the membrane is driven by the curvature of the BCL-xL TA within the membrane (top panel) and further stabilized by the presence of PUMA TA (middle panel), which maintains a double-kinked conformation of both TA helices. BCL-xL and PUMA TA allosterically modify the BH3-binding interface (see the enlarged interfaces in the top and middle panels) and also favors the formation of high-molecular-weight protein complexes, in a situation where BH3m is less competitive for binding antagonism. Potential mitochondrial proteins associated with PUMA/BCL-xL high-molecular-weight complexes are not shown. In addition, PUMA binding to BCL-xL increases the proximity of BAX to BCL-xL complexes (bottom panel), which may limit high-molecular-weight assembly. BAX promotes the sensitivity of PUMA/BCL-xL to BH3m antagonism through its own TA and its ability to interact with BCL-xL TA. Note that the conformational consequences of this functional relationship remain to be determined.

Our biochemical analysis indicates that binding to membrane-anchored partners enriches BCL-xL at membranes, consistent with groove engagement stabilizing anchoring24 and reducing cytosol shuttling5. However, TA displacement from the BCL-xL groove by the PUMA BH3 domains15,53 cannot fully explain these changes, since only PUMA (not PUMAdC) alters BCL-xL localization. Our biochemical investigation of cells co-expressing PUMA and BCL-xL reveals that membrane-anchored ligands enrich and reorganize the BCL-xL interactome into more complex assemblies. Subject to any potential changes induced by used detergents, mass spectrometry (with CHAPS) and BN-PAGE (with digitonin) consistently reveal increased membrane anchoring and complexity despite potential detergent effects. The high-molecular-weights of PUMA/BCL-xL complexes support previous findings that initiators/BCL-xL complexes extend beyond simple heterodimer20,25, involving additional proteins that now warrant characterization. Higher-order BCL-xL complexes, due to the TA of BCL-xL were already observed24. Doubly membrane-anchored complexes might allow currently underestimated binding interfaces in PUMA or BCL-xL to be manifest, possibly favored by the conformational constraints described above. We note that our mass spectrometric analysis identified, in BCL-xL pull-downs in the presence of PUMA, TOM40 and several components of the mitochondrial inner membrane (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Due to the pull-down method used here, further studies are required to confirm that these candidate proteins are involved in direct interactions. Membrane-anchored PUMA binding also promotes mitochondrial assembly of MCL-1 into high-molecular-weight protein complexes. Consistent with this, PUMA interaction with BCL-xL and MCL-1 in cells resist to BH3m treatments14. Thus, the synergistic effects of dual inhibition of BCL-xL and MCL-1 by BH3m may be limited when membrane anchoring prevents ligand displacement.

Co-expression of PUMA and BCL-xL enhances BAX/BAK recruitment near BCL-xL, as observed both in pull-down assays (using CHAPS to avoid artificial BAX activation) and in PLA using whole cells. This challenges the idea that executioners simply compete with initiators54. Instead, complex formation appears to shift BCL-xL complexes toward a new steady state where other pro-MOMP proteins are dynamically recruited. Activation of BAX by PUMA might account for an induced proximity to BCL-xL. PUMA/BCL-xL complexes may also stabilize BCL-xL at membranes and prevents BAX retrotranslocation, which depends on canonical BAX/BCL-xL binding and BCL-xL TA21,49. BAX/BAK molecules might thus accumulate in the proximity of mitochondrial BCL-xL through activation and/or aborted retrotranslocation, fostering non-canonical contacts. Reciprocally, this recruitment may mitigate the assembly of high-molecular-weight PUMA/BCL-xL complexes, as this tends to increase in baxCRISPR−/− bak1CRISPR−/− cells (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 5d).

Homo- and heterodimerization of BAX and guardian TAs add a regulatory layer to the BCL-2 network6,22. Our evidence pleads that this TA interplay, rather than groove competition, underlies BAX regulation of PUMA/BCL-xL BH3m sensitivity. We found that the BAX TA localizes near BCL-xL in PUMA/BCL-xL cells and sensitizes doubly anchored PUMA/BCL-xL complexes to BH3m-induced cell death. Swapping the BCL-xL TA with that of TOM 20 (non-interacting with BCL-2 family TAs) dampens the contribution of endogenous BAX on BH3m sensitivity, whereas swapping with BAX TA (self-associating and interacting with BCL-xL TA) enforces it. We propose that BAX TA interferes with BCL-xL TA adjustment in the membrane, promoting BH3m antagonism of doubly anchored complexes and impeding higher molecular weight assembly (Fig. 8). Endogenous BAK has a weaker effect, likely due to its TA’s lower affinity for BCL-xL55. The influence of BAX on PUMA/BCL-xL sensitivity to BH3m reveals unexpected feedback within the BCL-xL network and defines BAX as a major antagonist of BCL-xL at different steps, akin to a dominant negative form as initially stated in the «rheostat» model of death/survival decisions56. Our observations suggest that transcriptional regulation of executioner proteins can influence susceptibility to MOMP-induced cell death, as exemplified by c-Myc-driven BAX/BAK expression in developing tissues57, and p53-regulated BAX expression in multiple myeloma, correlating with BH3m-induced cell death58. Such a role, which implies that low noise BAX activation might be associated with BCL-xL dependency and BH3m efficiency, is consistent with the major impact of transcriptional regulation of BAX on MOMP susceptibility. Consistent with this, investigation using the Dependency Map portal shows that CRISPR-mediated BAX loss strongly inversely correlates with the impact of CRISPR invalidation of BCL-xL on cell fitness across diverse cell lines and tends to positively correlate with sensitivity to WEHI-539, which itself tracks with BCL-xL dependency (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Our findings prompt a re-evaluation of how BCL-2 family proteins are understood, especially when conclusions rely on soluble systems, TA-deficient proteins, or cells lacking BAX/BAK. Furthermore, they advocate for the development of new experimental strategies targeting BCL-xL interactions to better control cell survival. It supports designing BH3-in-groove antagonists guided on TA-induced allosteric regulation, explains the synergy between BAX activators and BCL-xL antagonists59, and suggests that mimics of BCL-xL, PUMA, or BAX TAs could modulate BH3m efficiency30,55.

Method

Cell culture

The MCF-7 line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and the HCT-116 line was a gift from Bert Vogelstein. All cell lines (MCF-7, HCT116 wild type and derivatives) were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in RPMI 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) + 1% penicillin-streptomycin and split 1 in 10 every 3–4 days. Cells were subjected to regular mycoplasma testing. baxCRISPR−/− and bakCRISPR−/− denote the inactivation of endogenous genes using virally delivered CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Lentivirus were produced from HEK 293 T cells transfected with the pLentiCRISPRV2-Puro plasmid containing the guide sequences AGTAGAAAAGGGCGACAACC and GCCATGCTGGTAGACGTGTA, respectively (a gift from Jonathan Lopez while he was working in Steven Tait’s lab). Cells were selected using 1 μg/ml puromycin and gene invalidation were confirmed by Western blot for the absence of detectable BAX and/or BAK compared to the parental cells. GBCL-xL, FPUMA/GBCL-xL, FPUMAdC/GBCL-xL denote stable cell lines obtained after infection with lentivirus produced from LZRS plasmid encoding GBCL-xL, FLAG-PUMA-2A-GFP-BCL-xL or FLAG-PUMAdC-2A-GFP-BCL-xL, respectively. Infected cells were selected with 1 mg ml−1 zeocin for 2 weeks and then sorted by Facs ARIA III to ensure homogenous GFP expression. This approach allows semi-equimolar co-expression of each transgene RNA from a 2A «self-cleaving» peptide sequence47. MBCBAX denote stable cell lines obtained after infection with lentivirus produced from pLVX-EF1α-IRES-Puro-Myc-BirA-CBAX plasmid encoding Myc-BirA-CBAX (BAX last 23 amino acids) and puromycin selection (1 μg/ml). The expression of each transgene was verified by Western blot. For transient expression, cells were transfected at 70–80% confluence using Opti-MEM reduced serum medium with Lipofectamine 2000, according supplier recommendations.

DNA constructs

The plasmids used in this study are listed in the key resources table. Cloning details will be provided upon request. All proteins are expressed from human cDNA and, for tBID, also from mouse cDNA. Plasmids for transient expression of untagged protein or domain were cloned into the pcDNA3 backbone, RLuc and YFP fused to the BCL-2 family member were assembled into the peYFP-C1 and pRLuc-C1 backbones, respectively. Substituting YFP with mCherry or GFP in the pEYFPC1 plasmid resulted in mCherry or GFP-fused proteins, respectively. In the plasmid for full-length or truncated PUMA expression, we exchanged its BH3-binding domain with the BH3 sequence of BID (Supplementary Table 1) using in-Fusion HD cloning. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to introduce mutations described in the study. All DNA manipulations and plasmids were confirmed by sequencing before use. To generate stable cell lines, transgenes were cloned into LZRS retroviral with P2A « self-cleaving » peptide sequence (a gift from Jonathan Lopez while he was working in Steven Tait’s lab) or pLVX-EF1α-IRES-Puro lentiviral backbones.

The nomenclature used throughout this study indicates proteins fused with R-Luciferase by a subscripted R, with YFP by a subscripted Y, with GFP by a subscripted G, with Flag by a subscripted F, with mCherry by the subscripted mC, and with MycBirA by the subscripted MB. Generated plasmids in this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

BRET saturation curve and dose-response

BRET experiments were performed as described in Pécot et al.12. Briefly, cells were plated in 24-well plates and transfected with increasing amounts (25–500 ng/well) of plasmids coding for a BRET acceptor (protein fused to YFP), and constant amounts (25 ng/well) of plasmid expressing a BRET donor (protein fused to R-Luciferase). BRET measurement was performed using the lumino/fluorometer Mithras LB 940 (or LB 943 model) Berthold Technologies, France after washing once with PBS and injection of coelenterazine H substrate in wells in PBS at a final molarity of 5 μM (Interchim). BRET signal corresponds to the emission signal values (530 nm) divided by the emission signal values (485 nm). The BRET ratio was calculated by subtracting the BRET signal value obtained with co-expressed donor and acceptor from that obtained with the donor protein co-expressed with the untagged donor protein. Data shown are representative of at least two independent experiments for saturation curves. For dose-response analysis, transfected cells were harvested and seeded in triplicate in 96-well white plates. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with a concentration range 1:2 serial dilution of BH3m (0.0006–10 μM) for 16 h, and BRET was measured as described above. Data are presented as the results of at least three independent experiments.

Imaging

Cells cultured on the glass side were transfected with mCherry-fused PUMA, and then loaded with MitoTracker Deep Red for 30 min in culture medium at 37 °C. They were then washed twice with PBS, fixed in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde/4% sucrose for 15 min, and mounted with ProLong Diamond Antifade Reagent. Fluorescence images were acquired with a Nikon A1R inverted confocal microscope (Nikon France, Champigny-sur-Marne) equipped with a 60×/1.4 oil immersion objective. Images were recorded according to the Nyquist criterion to ensure accurate resolution.

Modelling of BCL-xL structure in complex with PUMABH3 or dNPUMA

Membrane-anchored BCL-xL was obtained by merging the known NMR BCL-xL structure (PDB Id: 2LPC) with an ideal alpha helix model for BCL-xL α9 helix (residues S203 to K233)2. PUMABH3 domain-bound membrane-anchored BCL-xL was derived from the structure of globular BCL-xL in complex with PUMABH3 peptide (PDB Id: 2M0433). In the NMR structure 2M04, PUMABH3 (residues E130 to R154) is already adjusted to BCL-xL, we added the tail anchor part of BCL-xL with an ideal alpha helix model for BCL-xL α9 helix (residues S203 to K233) to obtain BCL-xL. Finally, the doubly anchored dNPUMA/BCL-xL was modeled in four steps: (i) 2M04 was taken as a starting structure for the globular part, (ii) the two TA (BCL-xL: S203 to K233, PUMA: S166 to N193) relative orientation was studied by protein-protein docking methods60, (iii) BCL-xL was reconstituted in membrane context, which allowed to orient PUMA TA relative to PUMABH3, and (iv) and by merging to the remaining linker between PUMABH3 and PUMA TA (155RRQEEQQRHRP165). PUMA linker made of 11 amino acids showed no structure preference using standard secondary structure prediction or protein-protein analysis on BCL-xL, it was thus modeled as a coil structure. Note that this structure lacks the N-terminal (for which no structural data exist), which we found to have no direct effect on BH3m sensitivity. Each system was inserted in a POPC membrane.

At the beginning of the simulation, both TA were tilted in the membrane (about 15°15) and TA were parallel according to our modeling procedure. Charges and protonation states of the model were assessed using PROPKA61 at pH 7. Insertion in a POPC membrane was performed using packmol-memgen62. The details of the system are given in Table 1.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed using AMBER 2063, generating trajectories spanning at least 2 μs using ffSB14 force field for proteins64 and lipids17 force fields for lipids, TIP3P water model65, employing the recommended settings as described in Dickson et al.66. Briefly, systems were modeled under periodic conditions, employing Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) electrostatics calculations, ffSB14 force field with a 10 Å cutoff and Langevin thermostat with a thermostat coefficient frequency of 1.0 ps−1. Upon protein insertion into the membrane, the system underwent minimization, comprising 5000 steps of steepest descent followed by 5000 steps of conjugate gradient, with a constraint of 2 kcal mol−1 Å−2 applied to both proteins and lipid atoms. System heating was performed in NVT conditions where a constraint of 10 kcal mol−1 Å−2 was applied to the atomics positions of proteins and lipids during the transition from 0 to 100 K over 50 ps and with a constraint of 5 kcal mol−1 Å−2 from 100 to 303 K for 100 ps. System volume was equilibrated in NVT conditions for 100 ps using a restraint of 5 kcal mol−1 Å−2, followed by a further equilibration period of 500 ps in NPT conditions under the same restraints conditions. Unrestrained simulations were then computed unrestrained for 2 μs. Starting from the initial structures described above, we performed the calculation of dNPUMA interacting with the BCL-xL WT and substitution mutants using PACKMOL-Memgen62 with the lipids21 force field66 and an ionic concentration of 0.15 M of NaCl, as recently recommended67.

Molecular dynamics analysis

All simulations were visualized using PyMOL (https://pymol.org) and VMD. Data analysis was performed using XmGrace (https://plasma-gate.weizmann.ac.il/Grace/), Python68, and matplotlib69.

Detailed energetic contribution analysis

System trajectories were analyzed using the MM/GBSA single-trajectory free energy calculations using MMPBSA.py44. The 600–2000 ns interval of the trajectories was considered with a calculation every 10 frames using IGB 5 and the LCPO method for surface calculation. Per-residue energy decomposition was obtained by adding 1–4 interactions to electrostatics and Van Der Waals energies. Further analyses were performed using in-house Python programs and plotted using matplotlib.

Subcellular fractionation

The heavy membrane and cytosol fractions from MCF7 and HCT116 cells were prepared by subcellular fractionation based on differential centrifugation. Cells were scraped, centrifuged, and washed twice at 1000 g for 10 min at 4 °C with ice-cold PBS. They were then resuspended in volume-per-volume cell extraction buffer (MB-EDTA) containing 210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.5), 1 mM PMSF, and 1 tablet of protease inhibitor. Cells were lysed using a Dounce homogenizer on ice, and sequential centrifugation (500 × g for 5 min, 2 × 2000 g for 5 min, and 13,000 × g for 10 min) resulted in pelleting the crude heavy membrane fraction. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant is the supernatant fraction. The crude heavy membrane pellet was washed once in cold MB-1mM EDTA (pH 7.5) buffer and centrifuged at 500 × g for 3 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the resulting pellet, containing mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, was solubilized in MB-EDTA buffer.

Western blot and BN-PAGE analysis

Proteins were obtained by lysing cells with RIPA buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS). Protein samples were subjected to Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ Precast Protein Gels, 4–20% and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using Trans-BlotR Turbo™ Transfer System Cell system (Bio-Rad). The membrane was then blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk TBS 0.05% Tween 20 and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C (listed in the key resource table). Blots were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature and visualized using the FUSION-FX 7 (Vilber).

Analysis of native protein complexes in membranes was performed by blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) following the supplier’s instructions (Life Technologies). Briefly, heavy membrane fractions were solubilized in 1% digitonin NativePAGE sample buffer from the supplier (50 mM BisTris, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.2 adjusted with 6 N HCl, 10% glycerol, 0.001% Ponceau S) for 10 min on ice. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (20,000 × g, 20 min, 4 °C). After the addition of NativePAGE G-250 Sample Additive, the heavy membrane extracts were applied to blue native PAGE Novex 4–16% Bis-Tris gels and subsequently blotted onto a PVDF membrane for Western blot analysis.

Incucyte imager-based videomicroscopy analysis

Cell death analysis was determined using an Incucyte Zoom imaging system (Sartorius). Cells were plated in 96-well plates and then treated with a concentration range 1:4 serial dilution of A-1331852 (0–10 μM) with and without S-63845 (0.5 μM) and AnnexinV-CF®594 Conjugate dye was then added. Plates were imaged every 60 min during 13 h. The quantitative analysis was done using Incucyte cell-by-cell analysis software module (Sartorius).

Immunoprecipitation assay

Protein lysates were obtained by lysing cells with IP buffer (TRIS 20 mM pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% CHAPS, 1 mM PMSF supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors) for 45 min on a roller in the cold room and clarified at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitation was performed on 500 µg protein lysates incubated with 5 µL anti-FLAG® M2 magnetic beads or ChromoTek GFP-trap® magnetic agarose for 45 min on a cold roller, followed by washing on a magnetic separator. Pulled-down proteins were analyzed by Western blot or mass spectrometry.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Beads containing protein complexes were re-suspended in 50 mM NH4HCO3, pH8 10 mM DTT were added for 15 min at 50 °C for reduction, and then 10 mM MMTS were added at room temperature for alkylation during 10 min. Trypsin was added at the protein/trypsin ratio of 50:1. Digestion was performed overnight at 37 °C. Peptides were acidified to a final concentration of 1% formic acid (FA), followed by desalting using C18 StageTips. Micro BCA assay was performed, and peptides were vacuum-dried in a SpeedVac concentrator and stored at −20 °C until measured by LC-MS/MS. Immediately prior to micro-LC, the fractions were resuspended in H2O with 0.1% v/v formic acid at a concentration of 1 µg µL−1.

Each sample (5 µg) was separated into a micro 2D-LC 425 system (Eksigent) using a ChromXP C18CL column (3 μm, 120 A, 15 × 0.3 cm, Sciex) at a flow rate of 5 μL/min. Water and acetonitrile, both containing 0.1% formic acid, were used as solvents A and B, respectively. The following gradient of solvent B was used: 0 to 5 min 5% B, 5 to 75 min 5% to 35% B, then 10 min at 95% B, and finally 10 min at 5% B for column equilibration. As the peptides eluted, they were directly injected into a hybrid quadrupole-TOF mass spectrometer Triple TOF 5600+ (Sciex, Redwood City, CA, USA) operated with a “top 30” data-dependent acquisition system using positive ion mode. The acquisition mode consisted of a 250-ms survey MS scan from 400 to 1250 m/z, followed by an MS/MS scan from 230 to 1500 m/z (75 ms acquisition time, 350 mDa mass tolerance, rolling collision energy) of the top 30 precursor ions from the survey scan. Two independent GFP pull-down samples were analyzed in separate mass spectrometry runs. For the relative quantification by SWATH-MS acquisition, each sample (5 µg) was analyzed using the LC-MS equipment and LC gradient described above for building the spectral library, but using a SWATH-MS acquisition method. The method consisted of repeating the whole gradient cycle, involving the acquisition of 32 TOF MS/MS scans of overlapping sequential precursor isolation windows (25 m/z isolation width, 1 m/z overlap, high-sensitivity mode) covering the 400 to 1200 m/z mass range, with a previous MS scan for each cycle. The accumulation time was 50 ms for the MS scan (from 400 to 1200 m/z) and 100 ms for the product ion scan (230 to 1500 m/z), giving a 3.5 s total cycle time. Peak extraction of the SWATH data was performed using Spectronaut® Pulsar X 13 software (Biognosys AGn Schlieren, Switzerland) with default analysis settings. Retention time prediction type was set to dynamic iRT, and calibration mode was set to automatic. These settings also included mutated decoy method and cross-run normalization enabled. The FDR was estimated with the mProphet approach, and Q value cut-off for both precursor and protein was set to 1%. Interference correction was enabled for quantification, which required a minimum of 2 precursor-ions and 3 fragment-ions. The term protein refers to protein groups as determined by the algorithm implemented in SpectronautTM. The quantitative SWATH scores were processed by dividing the SWATH score by the GFP score in each sample to normalize the measurements against immunoprecipitated GFP-BCL-xL and to perform statistical comparative analyses of differentially interacting proteins using the t.test function (stats R package). Volcano Plots were generated using the corresponding R package, and ggplot2 was used to produce boxplot figures.

Proximity ligation assay (PLA) flow cytometry experiment

GBCL-xL and FPUMA/GBCL-xL cells were collected by trypsinization and centrifugation, followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at RT. Subsequently, cells were rinsed with PBS and permeabilized using 0.5% saponin in PBS for 25 min at RT. PLA staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma Aldrich #DUO92002 #DUO92004 #DUO94004). The primary antibodies used were anti-BAX (Enzo #4F11, 1/500) and anti-GFP (Abcam #ab290, 1/2000). In negative control cells, primary antibodies were omitted. Flow cytometry analysis was conducted on an Attune Nxt instrument (Thermo Fischer Scientific) in BL1 and RL1 channels for GBCL-xL expression and PLA signal, respectively. Data acquisitions and analyses were performed using the Attune Cytometric Software, and statistical analyses were performed by Prism software.

Flow cytometry analysis

Cytochrome C release in MCF-7 cells was evaluated using the recombinant Alexa Fluor 488 (560263, BD Biosciences) or Alexa Fluor 647 (558709, BD Biosciences) Mouse anti-Cytochrome C after fixation/permeabilization using the FOXP3 Fix/Perm Buffer (Ebioscience, Thermofisher Scientific). For experiments involving cells expressing YBCL-xL or YBCL-xLdC complexes, FACS analysis was restricted to YFP-positive cells to ensure accurate assessment of successfully transfected populations. Flow cytometry analysis was performed on FACS Accuri C6 plus (BD Biosciences).

BirA-CBAX interaction partner identification

FPUMA/GBCL-xL MBCBAX and FPUMAdC/GBCL-xL MBCBAX HCT116 express the C-terminal sequence BAX fused to Myc-tagged BirA. Cells were grown in culture medium supplemented with 50 mM Biotin for 24 h, and protein lysates were obtained by lysing cells with RIPA buffer. Total extracts were incubated with streptavidin agarose beads overnight at 4 °C. Input and bead samples were resolved on a Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ Precast Protein Gels, 4–20% and analyzed by Western blot for the indicated proteins.

Statistical analysis

Statistical details of the experiments are provided in the respective figure legends.

P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Key resource table

The list of sources and identifiers for the reagents and resources used in this study can be found in the Supplementary Information file.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The LC-SWATH DIA MS data generated in this study have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange via the PRIDE database repository70 under the dataset identifier PXD066303; [https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD066303]. We have deposited the coordinates in PDB format for the initial structure and at time = 1000 ns, discussed in the article, of dNPUMA/BCL-xL and PUMABH3/BCL-xL in the Model Archive repository (https://www.modelarchive.org). PUMABH3/BCL-xL at the initial step of the simulation: PUMABH3/BCL-xL after 1000 ns of simulation: https://www.modelarchive.org/doi/10.5452/ma-k8uq8 dNPUMA/BCL-xL at the initial step of the simulation: https://www.modelarchive.org/doi/10.5452/ma-3ggc4 PUMABH3/BCL-xL after 1000 ns of simulation: https://www.modelarchive.org/doi/10.5452/ma-rm2rh The authors declare that all other source data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Python scripts to perform the mapping of MM/GBSA energies on the molecular dynamics simulation snapshots are available upon request.

References

Czabotar, P. E. & Garcia-Saez, A. J. Mechanisms of BCL-2 family proteins in mitochondrial apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-023-00629-4 (2023).

Lee, E. F. & Fairlie, W. D. The structural biology of Bcl-xL. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2234 (2019).

Juin, P., Geneste, O., Gautier, F., Depil, S. & Campone, M. Decoding and unlocking the BCL-2 dependency of cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 455–465 (2013).

Kalkavan, H. et al. Sublethal cytochrome c release generates drug-tolerant persister cells. Cell 185, 3356–3374.e22 (2022).

King, L. E. et al. Apoptotic priming is defined by the dynamic exchange of Bcl-2 proteins between mitochondria and cytosol. Cell Death Differ. 29, 2262–2274 (2022).

Beigl, T. B. et al. BCL-2 and BOK regulate apoptosis by interaction of their C-terminal transmembrane domains. EMBO Rep. 25, 3896–3924 (2024).

Todt, F. et al. Differential retrotranslocation of mitochondrial Bax and Bak. EMBO J. 34, 67–80 (2015).

Vuillier, C. et al. E2F1 interacts with BCL-xL and regulates its subcellular localization dynamics to trigger cell death. EMBO Rep. 19, 234–243 (2018).

Kale, J., Osterlund, E. J. & Andrews, D. W. BCL-2 family proteins: changing partners in the dance towards death. Cell Death Differ. 25, 65–80 (2018).

Soderquist, R. S. et al. Systematic mapping of BCL-2 gene dependencies in cancer reveals molecular determinants of BH3 mimetic sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 9, 3513 (2018).

Popgeorgiev, N., Jabbour, L. & Gillet, G. Subcellular localization and dynamics of the Bcl-2 family of proteins. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 6, 13 (2018).

Pécot, J. et al. Tight sequestration of BH3 proteins by BCL-xL at subcellular membranes contributes to apoptotic resistance. Cell Rep. 17, 3347–3358 (2016).

Aranovich, A. et al. Differences in the mechanisms of proapoptotic BH3 proteins binding to Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 quantified in live MCF-7 cells. Mol. Cell 45, 754–763 (2012).

Osterlund, E. J. et al. Efficacy and specificity of inhibitors of BCL-2 family protein interactions assessed by affinity measurements in live cells. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm7375 (2022).

Yao, Y. et al. Conformation of BCL-XL upon membrane integration. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 2262–2270 (2015).

Chi, X. et al. The carboxyl-terminal sequence of Bim enables Bax activation and killing of unprimed cells. eLife 9, e 44525 (2020).

Kaufmann, T. et al. Characterization of the signal that directs Bcl-xL, but not Bcl-2, to the mitochondrial outer membrane. J. Cell Biol. 160, 53–64 (2003).

Wilfling, F. et al. BH3-only proteins are tail-anchored in the outer mitochondrial membrane and can initiate the activation of Bax. Cell Death Differ. 19, 1328–1336 (2012).

Zhang, Z. et al. BH3-in-groove dimerization initiates and helix 9 dimerization expands Bax pore assembly in membranes. EMBO J. 35, 208–236 (2016).

Bogner, C. et al. Allosteric regulation of BH3 proteins in Bcl-xL complexes enables switch-like activation of Bax. Mol. Cell 77, 901–912.e9 (2020).

Todt, F., Cakir, Z., Reichenbach, F., Youle, R. J. & Edlich, F. The C-terminal helix of Bcl-xL mediates Bax retrotranslocation from the mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 20, 333–342 (2013).

Andreu-Fernández, V. et al. Bax transmembrane domain interacts with prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins in biological membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 310–315 (2017).

García-Murria, M. J. et al. Viral Bcl2s’ transmembrane domain interact with host Bcl2 proteins to control cellular apoptosis. Nat. Commun. 11, 6056 (2020).

Bleicken, S., Hantusch, A., Das, K. K., Frickey, T. & Garcia-Saez, A. J. Quantitative interactome of a membrane Bcl-2 network identifies a hierarchy of complexes for apoptosis regulation. Nat. Commun. 8, 73 (2017).

Singh, P. K. et al. Dynein light chain 1 induces assembly of large Bim complexes on mitochondria that stabilize Mcl-1 and regulate apoptosis. Genes Dev. 31, 1754–1769 (2017).

Follis, A. V. et al. Regulation of apoptosis by an intrinsically disordered region of Bcl-xL. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-018-0011-x (2018).

Sora, V. & Papaleo, E. Structural details of BH3 motifs and BH3-mediated interactions: an updated perspective. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 864874 (2022).

Rautureau, G. J. P., Day, C. L. & Hinds, M. G. Intrinsically disordered proteins in Bcl-2 regulated apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 11, 1808–1824 (2010).

Liu, X., Beugelsdijk, A. & Chen, J. Dynamics of the BH3-only protein binding interface of Bcl-xL. Biophys. J. 109, 1049–1057 (2015).

Mizukoshi, Y. et al. Targeting the cryptic sites: NMR-based strategy to improve protein druggability by controlling the conformational equilibrium. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd0480 (2020).

Bekker, G.-J., Araki, M., Oshima, K., Okuno, Y. & Kamiya, N. Mutual induced-fit mechanism drives binding between intrinsically disordered Bim and cryptic binding site of Bcl-xL. Commun. Biol. 6, 349 (2023).

Rajan, S., Choi, M., Baek, K. & Yoon, H. S. Bh3 induced conformational changes in Bcl-Xl revealed by crystal structure and comparative analysis: structure of Bcl-XL BID BH3/BIM BH3 Complexes. Proteins 83, 1262–1272 (2015).