Abstract

Kinetic-scale electromagnetic fluctuations are frequently observed in the reconnection electron diffusion region. However, their potential to accelerate magnetic reconnection through anomalous effects remains a topic of debate, with a lack of direct in-situ observational evidence. Using the unprecedented high-resolution data from Magnetospheric Multiscale mission, we directly and systematically calculate the secular field-particle energy exchange rate and anomalous electric fields associated with electromagnetic fluctuations within 13 electron diffusion regions observed in Earth’s magnetotail. Our findings reveal that the electromagnetic anomalous viscosity is the primary contributor to the anomalous electric field induced by electromagnetic fluctuations within the electron diffusion region. The maximum contribution of the anomalous viscosity can account for up to ~ 20% of the fast reconnection electric field, though it is typically less than 5% in most cases. We further find that locally growing electromagnetic fluctuations tend to accelerate reconnection, while locally damping electromagnetic fluctuations inhibit it. These results offer insights into the coupling between kinetic-scale electromagnetic fluctuations and magnetic reconnection in collisionless plasmas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic reconnection is a fundamental process responsible for fast energy conversion in astrophysical, space, and laboratory plasma systems1,2,3. It is implicated in explosive phenomena such as fast radio bursts and X-ray bursts4,5,6, solar flares7,8, and planetary substorms9,10. A long-standing question in magnetic reconnection is how the plasma decouples from magnetic fields in the electron diffusion region (EDR). In collisional plasmas, Coulomb collisions provide the resistivity necessary for the decoupling of magnetic fields and plasmas, and for energy dissipation within the diffusion region11,12,13. However, in collisionless plasmas, Coulomb collisions between particles are negligible due to the large mean free path compared to the characteristic system size14,15,16,17. Therefore, alternative dissipation mechanisms must be considered in collisionless magnetic reconnection.

The electron pressure gradient and electron inertial effect in the electron momentum equation are two candidate mechanisms for breaking magnetic field lines in collisionless EDR18,19. Recent particle-in-cell (PIC) simulations have shown that the electron pressure gradient term can support the reconnection electric field in fast collisionless reconnection20,21. This finding has been corroborated by high-resolution spacecraft observations22,23,24. In addition, wave-particle interactions have been proposed as another possible dissipation mechanism. Field-particle interactions associated with electromagnetic (EM) fluctuations can participate in reconnection via effective particle scattering and diffusion, providing anomalous resistivity resembling Coulomb collisions25. These interactions, termed anomalous effects, include anomalous drag, viscosity, and transport, and are proposed to affect the temporal behavior of fast reconnection in collisionless plasmas26,27,28,29,30. The relevant waves or instabilities that contribute to anomalous effects involve lower-hybrid drift instabilities31,32, whistler waves28,29,33,34, drift kink instabilities35, Buneman instabilities36, electron Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities37,38,39, and plasmoid-induced turbulence40,41.

Fluctuations near the lower-hybrid frequency (LHF) have drawn considerable attention as a candidate responsible for anomalous effects42. Electrostatic (ES) LHF fluctuations are typically observed at boundaries with a strong density gradient, both in symmetric and asymmetric reconnection. These ES fluctuations primarily emerge in the low plasma β region away from the EDR. Although ES LHF fluctuations can also survive at the center of reconnecting current sheets when a large guide field reduces the β value therein32,43, EM LHF fluctuations are more frequently detected near and within the EDR28,29,39,44,45,46,47,48. It is commonly recognized that anomalous electric field contributed by LHF fluctuations are negligible compared to the electron pressure gradient term within the EDR21,49. However, there are still some studies that suggest that an anomalous electric field arising from LHF fluctuations is significant28,29,30,32,50,51. One of the reasons for the emergence of these different viewpoints is that the PIC simulations are constrained by artificial parameters, making it difficult to achieve realistic ion-to-electron mass ratios and large electron plasma to gyrofrequency ratios (ωpe/ωce)42,52. Although the anomalous effects have been quantified in asymmetric reconnection by in-situ observation53, comparable evidence for their importance within the EDR of symmetric reconnection is still lacking. Therefore, it is essential to directly quantify and systematically assess the anomalous effects within the EDR of symmetric reconnection using high-resolution in-situ measurements, in order to better understand the role of EM fluctuations in reconnection.

Here, we use data from the Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission54 (see Methods section) to directly characterize the secular field-particle energy exchange rate and anomalous effects of EM fluctuations within 13 EDRs of symmetric reconnection observed in the Earth’s magnetotail. These EM fluctuations appear near the local LHF range. The results show that the EM fluctuations can provide anomalous effects within EDRs and are primarily through the EM anomalous viscosity term \({{{\boldsymbol{T}}}}_{{\mathrm{EM}}}=-\frac{ < \delta (n{{\bf{V}}})\times \delta {{\bf{B}}} > }{ < n > }\). The maximum contribution of \({{{\boldsymbol{T}}}}_{{\mathrm{EM}}}\) is up to approximately 20% of the reconnection electric field, while it is less than 5% inside most EDRs. The positive/negative effects of these EM fluctuations on the reconnection electric field are closely related to the growing/damping state of these EM fluctuations.

Results

Observations of electromagnetic fluctuations inside EDR

Table 1 presents 13 EDR events associated with EM fluctuations in the magnetotail (see Methods section)55. An EDR of magnetotail reconnection was encountered by the MMS spacecraft at approximately 20:24:07 UT on June 17, 2017, when the spacecraft were positioned around [−19.3, −11.1, 3.6] RE in Geocentric Solar Magnetospheric (GSM) coordinates56,57,58. Figure 1b–i illustrate MMS2 observations during this reconnecting current sheet crossing in the local current sheet (LMN) coordinate system. The reversal of BL from negative to positive (Fig. 1b) and the positive electron jet VeL (Fig. 1c) suggest that MMS crossed the reconnecting current sheet from the +L side of the reconnection X-line, as depicted in Fig. 1a. The reconnection electric field ER is directed along the +M direction in this LMN coordinate system, and a large out-of-plane electron jet was observed along the −M direction with VeM ~−1800 km/s. The magenta rectangle marks the EDR of this reconnection event (see Methods section), where the electron frozen-in condition is broken, i.e., \({{{\bf{E}}}}^{{\prime} }={{\bf{E}}}+{{{\bf{V}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}}\times {{\bf{B}}}\ne 0\), and concomitant observed non-zero energy dissipation \({{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\bf{E}}}{\prime}\), crescent-shaped electron velocity distribution56, the enhancement of electron agyrotropy and thermal Mach number59.

During this interval, the four MMS spacecraft formed a tetrahedron with a quality factor of ~0.984. The average spacing among the four spacecraft was about 26 km ~4 de, where 1 de is 7 km given an average electron density of 0.56 cm−3. a illustrates the spacecraft trajectory and propagating of EM fluctuations, b three components of magnetic field, c electron bulk velocity, d electric field fluctuations, e spectrum of E, f magnetic field fluctuations, g spectrum of B, h ellipticity, i electron beta \({\beta }_{e}\). The vectors are shown in local boundary normal (LMN) coordinates, refer to Wang et al.55, and references therein, where L is along the reconnecting magnetic field direction, N is the normal direction of the current sheet, M is the out-of-plane direction of the current sheet, and N = L × M completes the right-hand coordinate system. To perform statistical analysis, we uniformly adjust the +M of all EDR events to the direction of the reconnection electric field, i.e., ER > 0 in all EDR events in this work. The second and third columns: estimated frequency-wave number (f-k) power spectrum of EM fluctuations in the vicinity of the reconnection site. j–l show the f-kL, f-kM, and f-kN of EM fluctuations in the BL < 0 side (20:24:03-20:24:07 UT) of the reconnecting current sheet, while m–o show the f-kL, f-kM, and f-kN of EM fluctuations in the BL > 0 side (20:24:07-20:24:11 UT). The wave number k has been normalized by \(\sqrt{{\rho }_{e}{\rho }_{i}}\), where \({\rho }_{e}\) and \({\rho }_{i}\) are the electron and ion gyration radii, respectively. The dashed lines denote the fit of the linear dispersion relation \(f=\frac{{V}_{{ph}}}{2\pi }{{\bf{k}}}\).

EM fluctuations with frequencies between ~1 and 16 Hz, near the local LHF, were enhanced in the vicinity of the EDR (Fig. 1e, g). The electric field fluctuations \({{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}}\) are dominated by \(\delta {E}_{N}\) with a maximum amplitude of ~5 mV/m (Fig. 1d), while the magnetic field fluctuations \({{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{B}}}\) show similar amplitudes in three directions with a maximum amplitude of ~1 nT (Fig. 1f). These EM fluctuations are mainly inclined to right-handed circular polarization (Fig. 1h), indicating they may be whistler-branch waves. The EM fluctuations primarily exist in the center of the reconnecting current sheet, where \({\beta }_{e}\) is greater than 1 (Fig. 1i). These features are consistent with the EM turbulence in the EDR observed in three-dimensional PIC simulations29 and laboratory plasmas28.

Figure 1j–o presents the estimated dispersion relation (f-k) spectra of the EM fluctuations using spectral phase differences analysis based on multiple spacecraft measurements34,47,60,61,62. Figure 1j–l displays the estimated f-k spectra and phase velocity Vph of EM fluctuations on the −N (BL < 0) side of the current sheet along the L, M, and N directions, respectively. Figure 1m–o has the same format as Fig. 1j–l except for the +N (BL > 0) side of the current sheet. These results show that EM fluctuations primarily propagate in the −N (+N) direction on the BL < 0 (BL > 0) side with VphN ~−1500 km/s (VphN ~ 800 km/s) as shown in Fig. 1a. Additionally, there is another weaker wave mode at a higher frequency range (f ~ 6–15 Hz, marked by a red dashed line), suggesting that EM fluctuations are composed of several wave modes or the phase speeds may be quite uncertain. The wavenumber \(k\sqrt{{\rho }_{i}{\rho }_{e}} \sim 1\) (Fig. 1j–o) of these EM fluctuations indicates they are long-wavelength LHF wave modes47,63. Furthermore, the EM fluctuations propagate along the +L and −M directions, matching the direction of the outflow and out-of-plane electron jets, respectively. The phase velocity of EM fluctuations along the −M direction, VphM ~−2500 km/s, is close to the ion-electron relative drift velocity in the −M direction, Vd ~ VeM ~−2000 km/s (Fig. 2b), which implies a possible interaction between the EM fluctuations and the out-of-plane electron jet28.

a three components of the magnetic field, b electron bulk velocity, c total secular field-particle energy exchange rate, d spectrum of secular field-particle energy exchange rate \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t,f\right)\), e spectrum of secular field-particle energy exchange rate \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t,f\right)\), f secular filed-electron energy exchange rate. g–i distribution functions of secular field-electron energy exchange in velocity phase space in L, M, and N directions, respectively.

Secular field-particle energy exchange

To elucidate the field-particle interaction, we calculated the secular field-particle energy exchange rate between the EM fluctuations and plasma, denoted as \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t,f\right)\) (see Methods section). This metric helps determine whether these EM fluctuations are growing or damping in the EDR64,65,66. Figure 2d, e present the spectra of \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t,f\right)\), estimated from the current density derived via the curlometer technique, \({{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}}}=\nabla \times {{\bf{B}}}/{\mu }_{0}\), and from plasma moments, \({{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}={en}({{{\bf{V}}}}_{{{\rm{i}}}}-{{{\bf{V}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}})\), respectively. Both spectra show significantly negative \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t,f\right)\) values associated with EM fluctuations in the 1–16 Hz range. Figure 2c displays the secular field-particle energy exchange rates, \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t\right)\) (red curve) and \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t\right)\) (black curve), integrated from 1 to 16 Hz, derived from the \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t,f\right)\) and \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t,f\right)\) spectra, respectively. Both the black and red curves exhibit negative values with a peak around −5 pW/m³, which indicates that the plasma moments data and results are reliable, and the EM fluctuations gain energy from the plasma. Wang et al.55 proposed that these EM fluctuations, initially generated along the direction of the electric current (the Y direction in the GSM coordinates), propagate toward a tilted current sheet with the normal direction of the current sheet points primarily along YGSM, hence the waves appear to propagate along this local normal direction. In contrast, our results show that the LHF EM fluctuations grow locally within the EDR, suggesting that they originate from the center of the reconnecting current sheet and then propagate outward (Fig. 1a). This local growth may be related to the pinching of the current sheet as proposed by Yoon et al.67, which could act as a source of fluctuating energy.

The integrated secular field-electron energy exchange rates, \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t\right)\) (green curve in Fig. 2c, f), estimated from the electron current density \({{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}}\), align well with the black curve, as the current density in the EDR is primarily carried by electrons, \({{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\approx {{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}}\). This means that the EM fluctuations gain energy directly from electrons rather than ions in the EDR. To identify electrons in which phase space are involved in these interactions, Fig. 2g–i shows the distributions of the secular energy exchange rates in one-dimensional electron velocity phase space along the L, M, and N directions (see Methods section). We see that intense secular field-electron energy exchange occurs within a broad range of \([-{\mathrm{3.5,3.5}}]\times {10}^{4}\) km/s in all three directions in velocity phase space. This contrasts with the classical resonance interaction scenario, where energy exchange occurs only around resonance velocities; hence, we suggest that non-resonant interactions are important in the EDR68. The intense field-electron energy exchange in the EDR may result in efficient electron scattering and associated anomalous effects in reconnection28,29,39.

Anomalous effects of electromagnetic fluctuations

The anomalous effects induced by wave-particle interactions can be quantified by examining ensemble averaged second-order terms in the electron momentum equation, which can be written as34,53,69:

where D, \({{\bf{T}}}={{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{ES}}}}+{{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{EM}}}}\), and I are the anomalous drag (resistivity), anomalous viscosity (momentum transport), and anomalous Reynold’s stress, respectively. These quantities are defined as:

The contributions of I are neglected in our analyses since it is generally much smaller than D and T due to it being related to the specific charge of the electron42. The anomalous viscosity T is split into two components \({{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{ES}}}}\) and \({{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{EM}}}}\), here. \({{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{ES}}}}\) (the ES anomalous viscosity term) is the anomalous Lorentz force due to the background magnetic field \( < {{\bf{B}}} > \) and this term exactly cancels with D for frozen-in electrons, such as in the ES lower hybrid drift waves53,70. \({{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{EM}}}}\) (the EM anomalous viscosity term) corresponds to the anomalous Lorentz force due to fluctuating magnetic field \({{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{B}}}\), i.e., the classical EM anomalous viscosity term41. The total anomalous electric field is defined as \({{\bf{R}}}={{\bf{D}}}+{{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{ES}}}}+{{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{EM}}}}\).

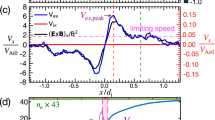

Figure 3 illustrates the anomalous effects of EM fluctuations along the out-of-plane direction (M direction), estimated using the spectral average method (see Methods section). The EM anomalous viscosity term \( < {n}_{e} > {T}_{{EM},M}\) (Fig. 3e) exhibits significant positive values corresponding to EM fluctuations in the EDR, whereas \( < {n}_{e} > {D}_{M}\) (Fig. 3c) and \( < {n}_{e} > {T}_{{ES},M}\) (Fig. 3d) do not show clear enhancement. Figure 3b presents the anomalous electric fields in the M direction, which are integrated from the spectra within the 1–16 Hz frequency range (see Table 1). The total anomalous electric field RM reaches a positive peak of approximately 0.025 mV/m inside the EDR. It is in the same direction as the out-of-plane reconnection field; however, its magnitude is only 3% of the reconnection electric field (see Table 1). The increase in RM is primarily contributed by TEM,M of EM fluctuations at frequencies near the lower hybrid frequency (fLH). The anomalous drag DM and the ES anomalous viscosity term TES,M are negligible in comparison to TEM,M. This is different from previous observations of ES fluctuations53 in asymmetric reconnection at the magnetopause. Notably, DM and TES,M show an anti-correlated change within the EDR, even though electrons are not entirely frozen-in, similar to the ideal electron-magnetohydrodynamic nature seen in PIC simulations70 and recent observations53.

a three components of the magnetic field, b total anomalous electric fields RM (black), anomalous drag DM (blue), anomalous viscosity \({T}_{{ES},M}\) (red) and \({T}_{{EM},M}\) (green) in M direction. The colored shaded regions associated with the anomalous terms represent the uncertainty in the calculation based on the uncertainties in the particle moments and electric field. The values of \({T}_{{EM},M}\) within this EDR are larger than its uncertainty (see Methods section). c Spectra of anomalous drag term \( < {n}_{e} > {D}_{M}\), d ES anomalous viscosity term \( < {n}_{e} > {T}_{{ES},M}\), e EM anomalous viscosity term \( < {n}_{e} > {T}_{{EM},M}\).

Figure 4 details the other two EDRs (events 7 and 10 in Table 1), which are associated with strong EM fluctuations near the LHF observed in the magnetotail on 2018-08-27 (Fig. 4a–h) and 2017-07-11 (Fig. 4i–p), respectively. The secular field-particle energy exchange \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t,f\right)\) in EDR 7 is predominantly negative at the central region and slightly positive at the edges (Fig. 4c, d), indicating that the EM fluctuations are growing within this EDR. The total anomalous electric field in the M direction RM during EDR 7 shows a positive peak of ~0.371 mV/m at the center, with smaller negative peaks at the edges of the EDR (Fig. 4e). This feature resembles the anomalous electric fields observed in recent three-dimensional simulations41,48. The positive peak magnitude of RM is up to 18% of the reconnection electric field in this EDR, much larger than that of EDR 2. Figures 4f–h present the time-frequency spectra of the anomalous effects, with the positive peak of TEM,M attributed to EM fluctuations around the LHF.

a, i three components of the magnetic field, b, j electron bulk velocity, c, k total secular filed-particle energy exchange rate corresponding to fluctuations, d, l spectra of \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{{\bf{J}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t,f\right)\), e, m total anomalous electric fields RM (black), anomalous drag DM (blue), anomalous viscosity \({T}_{{ES},M}\) (red) and \({T}_{{EM},M}\) (green) in M direction. The colored shaded regions associated with the anomalous terms represent the uncertainty in the calculation based on the uncertainties in the particle moments and the electric field. f–h, n–p spectra of anomalous effects.

In contrast, the secular field-particle energy exchange \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \left(t,f\right)\) for EDR 10 is positive (Fig. 4k, l), hence the EM fluctuations are damping within this EDR. The anomalous electric field in the M direction RM for EDR 10 shows a positive peak of ~0.036 mV/m, only ~1% of the reconnection electric field, at the center and negative values at the EDR edges as well (Fig. 4m). One can see that fluctuations in the anomalous electric fields are observed both inside and outside the EDR. The intense secular field-particle energy exchange and associated larger anomalous electric field occur outside the EDR in this event, differing from the above two EDRs. Interestingly, in these events, RM is predominantly contributed by TEM,M, while DM is small and counterbalanced by TES,M in most regions.

Statistical results

Columns 5 and 6 of Table 1 display the maximum total anomalous electric field RM,max and the maximum average non-ideal electric field \({ < {E}^{{\prime} } > }_{M,\max }\) in the M direction for all EDR events, where \( < {{{\bf{E}}}}^{{\prime}} > = < {{\bf{E}}} > + < {{{\bf{V}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}} > \times < {{\bf{B}}} > \). In all events, the EM fluctuations contribute a positive anomalous electric field in the +M direction, which can support the reconnection electric field. To assess the relative significance of the anomalous electric field to the reconnection electric field, we calculate the ratio of RM,max to \({ < {E}^{{\prime} } > }_{M,\max }\), denoted as \({P={R}_{M,\max }/ < {E}^{{\prime} } > }_{M,\max }\), as shown in Column 7 of Table 1. The maximum contribution of the anomalous electric field associated with EM fluctuations can reach up to ~20% of the reconnection electric field, but it is less than 5% in approximately 70% of the events.

For each event, we normalize \({R}_{M}\), \({T}_{{EM},M}\), \({T}_{{ES},M}\) and \({D}_{M}\) by the maximum absolute values of the total anomalous electric field \({|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\). Figure 5a shows the statistical results of the normalized anomalous electric field \({R}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\) and the normalized anomalous viscosity term \({T}_{{EM},M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\) for all EDRs. All data points are clustered around the line of \({R}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }={T}_{{EM}}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\) (black line), with a positive correlation coefficient of approximately r = 0.98, indicating that the anomalous electric fields within all EDRs are mainly contributed by the EM viscosity term TEM. Figure 5b shows the normalized anomalous drag \({D}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\) and the normalized ES viscosity term \({T}_{{ES},M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\). These two terms are smaller than TEM,M and nearly cancel each other out within the EDRs, with a correlation coefficient of approximately r = −0.64 between them.

a relation between anomalous electric field \({R}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\) and anomalous viscousity \({T}_{{EM},M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\), b the relation between anomalous drag \({D}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\) and anomalous viscosity \({T}_{{ES},M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\). Data points in a, b are from all 13 EDRs. The black lines in (a, b) denote \({R}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }={T}_{{EM}}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\) and \({T}_{{ES},M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }=-{D}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\), respectively. c, d show the correlation between the normalized secular field-particle energy exchange and anomalous electric field, i.e., \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > /{| < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > |}_{\max }\) and \({R}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\). Data points in c are from EDR events 1–9, while data points in d are from EDR events 10–13. Different colors and markers are used to represent different EDR events.

Does the evolution stage (growing or damping) of these EM fluctuations correlate with their roles in the reconnection process? Fig. 5c, d examines the statistical relationship between \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \) and RM across all EDR events. For each event, we normalize \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > \) and RM by their maximum absolute values, \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > /{| < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > |}_{\max }\) and \({R}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\). Figure 5c shows a scatter plot of \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > /{| < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > |}_{\max }\) and \({R}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\) from events 1–9. A clear inverse correlation is observed, with a correlation coefficient of approximately −0.68. In these events, negative (positive) secular field-particle energy exchange correlates with a positive (negative) anomalous electric field in the M direction, and the intensity of \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > /{| < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > |}_{\max }\) can influence the magnitude of \({R}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\). This suggests that the growing or damping state of EM fluctuations is a key factor in determining whether they contribute to or inhibit the reconnection electric field. In contrast, Fig. 5d shows the scatter plot of \( < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > /{| < {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}\cdot {{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}} > |}_{\max }\) and \({R}_{M}/{|{R}_{M}|}_{\max }\) from events 10–13, where no clear correlation is evident. These findings indicate that while the growing or damping state of EM fluctuations significantly influences their anomalous effect on the reconnection electric field, it is not the sole determinant.

Discussion

In this work, we employed a spectral average method to accurately determine the secular field-particle energy exchange and the anomalous electric field associated with EM fluctuations from in-situ data. This method provides a perspective on understanding the coupling between kinetic-scale fluctuations and symmetric reconnection in collisionless plasmas. The results directly demonstrate that EM LHF fluctuations can locally grow and damp within the EDR. The anomalous electric fields of EM fluctuations within the EDR are mainly contributed by the EM anomalous viscosity term TEM,M, rather than by anomalous drag DM or the ES anomalous viscosity term TES,M. Additionally, although electrons are not entirely frozen-in within the EDR, the anomalous drag DM and the ES anomalous viscosity TES,M are mutually restrained, similar to the effects induced by ES lower-hybrid drift waves in asymmetric reconnection, where electrons are approximately frozen-in53,70.

The guide field Bg and the normal component of the magnetic field BN in reconnection are two additional potential factors influencing the role of anomalous effects. In these EDRs, BN is much smaller than the asymptotic inflow magnetic field B0 (i.e., BN < 0.1 B0) and can therefore be neglected. The guide fields Bg in these events range from 0 to 0.5 B0, as shown in Column 8 of Table 1, yet the ratio P = RM,max/<E’ > M,max (Column 7 of Table 1) appears uncorrelated with Bg, with a correlation coefficient r ~ −0.02. Another possible factor is the asymmetry across the current sheet. For instance, intense ES LHF waves are driven by strong density gradients across the magnetopause reconnecting current sheet, where the anomalous drag \({{\bf{D}}}\) is approximately balanced by \({{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{ES}}}}\), while \({{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{EM}}}}\) can be neglected53. Here we find that the EDR of symmetric reconnection in the magnetotail is mainly characterized by EM LHF fluctuations rather than ES fluctuations, and the dominant contribution to the anomalous electric field is the EM viscosity term \({{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{EM}}}}\). The asymmetry of the current sheet primarily affects the type of waves generated, but may not directly change the magnitude of the anomalous electric field. Further investigations are required to identify and quantify other contributing factors.

The maximum contribution of anomalous electric fields provided by EM anomalous viscosity can be up to about 20% of the fast reconnection electric field. This maximum contribution in low guide field (Bg ~ 0.05) symmetric reconnection is comparable to the role played by the anomalous drag of ES lower-hybrid drift waves reported in laboratory symmetric reconnection with a large guide field (Bg ~ 0.7 B0)32. However, the contribution of anomalous electric fields is less than 5% in most events. This is consistent with the prevailing consensus that anomalous effects generally do not significantly influence the reconnection rate49. The proportion of anomalous electric field varies significantly across different EDRs and appears to be independent of the guide field strength, which may suggest that the role of anomalous effects driven by kinetic-scale EM fluctuations may evolve over time during reconnection. For example, the viscosity term may become important at later stages of reconnection29,51,71. However, spacecraft observations cannot continuously monitor the full temporal evolution of a single reconnection event or clearly distinguish the different stages among separate events. Therefore, future work should include detailed comparisons between in-situ observations and simulations performed under more realistic parameters.

Methods

MMS data

The data used in this study are from the following instruments onboard MMS: the Fluxgate Magnetometer (FGM)72; the Fast Plasma Investigation (FPI)73; the Electric Double Probes (EDP)74,75. Since the frequency ranges of these EM fluctuations in the EDR events are mainly less than 16 Hz, the burst mode magnetic fields from FGM with a sampling rate of 128 Hz, the fast mode electric fields from EDP with a sampling rate of 32 Hz, and the burst mode electron data from FPI with the resolution of 0.03 s–33 Hz are used in this paper.

The magnetic fields, electric fields, and plasma moments used to calculate the spectra of the time-averaged quantities in this study have been averaged over multiple spacecraft. Note that not all four MMS spacecraft have valid data for each event. For example, the FPI on MMS4 was out of order after June 2018, resulting in a lack of electron moments data from MMS4 after June 2018. Therefore, for events 1, 2, 5, 10, 11, and 12, the fields and plasma moments were averaged over all four MMS spacecraft, while for the other events, the average values are calculated using the data from only three MMS spacecraft.

In the magnetotail, the electron counts are low, and internal photoelectrons may significantly affect the reliability of the plasma moments. The L2 electron moments data from MMS have been corrected to eliminate photoelectron contamination. The L2 data are deemed reliable in events 1–5 and 8–12, as the electron moments data are almost identical to the partial moments data, which excludes low-energy electrons that are likely influenced by photoelectrons. For these events, both the electron moments and the corresponding uncertainty data are used. However, the L2 data for events 6, 7, and 13 are considered unreliable. Therefore, partial moments data with energy greater than 50 eV are used for these events to enhance the quality of the electron moments. One should be noted that there is no uncertainty data available in the partial moments data product.

Definition and time window of EDRs

Most EDR events in our list have been reported in previous studies, as shown by Wang et al.55, and the references therein. In this paper, we employ six parameters to identify the EDR: (1) electron agyrotropy as defined by Swisdak76; (2) agyrotropy of the measured electron pressure tensor based on Scudder et al.59; (3) electron thermal Mach number following Scudder et al.59; (4) energy dissipation as proposed by Zenitani et al.77; (5) energy gain per cyclotron period based on Scudder et al.59; and (6) the relative strength of electric and magnetic forces in the electron fluid rest frame, also based on Scudder et al.59. Although not every case exhibits increase in all of the six parameters, at least three parameters show significant enhancements. These observations indicate that all the analyzed events correspond to EDR crossings.

Moreover, we find that the electron thermal Mach number increases significantly in all EDR events. Therefore, we primarily use the enhancement of this parameter to determine the time windows for each EDR. Considering that the EM fluctuations near the EDRs typically have a minimum frequency close to 1 Hz, we determine the EDR windows (i.e., begin and end time) with a temporal resolution of 1 s.

Calculate the spectrum of the time-averaged quantities

The spectral average method

The spectrum of secular filed-particle energy exchange rate as a function of time and frequency is defined as64,65,66

where \({{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}(t,f)\), \({{{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{J}}}(t,f)}^{*}\), \({{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}}(t,f)\), \({{{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}}\left(t,f\right)}^{*}\) represent the wavelet spectra and corresponding conjugate counterparts of the current density \({{\bf{J}}}(t)\) and electric field \({{\bf{E}}}(t)\), respectively.

The secular energy exchange rates in one-dimensional electron velocity phase space

The time series of the reduced one-dimensional (1D) electron velocity distribution functions are expressed as \({f}_{e}\left(t,{V}_{k}\right)=\iint {f}_{e}\left(t,{{\bf{V}}}\right){{dV}}^{2}\), where \(k=L,M,N\) denotes the directions in the LMN coordinate system. Based on the definition of electron current density, \({J}_{e,k}=-{en}{V}_{e,k}\), the time series of 1D electron current density distribution in velocity phase space can be expressed as

Taking \(k=M\) as an example, for each velocity VM = V0, we have an associated electron current density \({J}_{e,M}\left(t,{V}_{0}\right)\) and its wavelet spectrum \(\delta {J}_{e,M}\left(t{,V}_{0},f\right)\). Using Eq. (6) in the main text, we derive the secular energy conversion spectrum corresponding to this current density, \( < \delta {J}_{e,M}\delta {E}_{M} > \left(t,{V}_{0},f\right)\). Integrating this spectrum over the frequency range of the EM fluctuations yields the secular energy conversion rate \( < \delta {J}_{e,M}\delta {E}_{M} > (t,{V}_{0})\), representing the contribution from electrons with velocity VM = V0.

Repeating the above process across all velocities in the 1D velocity phase space yields the 1D distribution of field–electron secular energy exchange rates in the 1D velocity phase space, \( < \delta {J}_{e,M}\delta {E}_{M} > (t,{V}_{M})\), as shown in Fig. 2h. The same computational procedure is applied to the \(k=L,N\) to obtain \( < \delta {J}_{e,L}\delta {E}_{L} > \left(t,{V}_{L}\right)\) and \( < \delta {J}_{e,N}\delta {E}_{N} > \left(t,{V}_{N}\right)\) as shown in Fig. 2g, i, respectively.

Spectra of anomalous terms

The quantities of anomalous effects in Eq. (1) are computed from an ensemble average ideally. In this work, we use the four-spacecraft average and the spectra time-average method provided in Eq. (6) to estimate the spectra of anomalous terms. First, we calculate the four-spacecraft average fields and plasma moments, i.e., E, B, ne, Ve, and (neVe). Second, we calculate their wavelet spectra, i.e., \({{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}}\), \({{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{B}}}\), \(\delta {n}_{e}\), \({{\rm{\delta }}}{{{\bf{V}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}}\), and \({{\rm{\delta }}}({n}_{e}{{{\bf{V}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}})\) and corresponding conjugate counterparts, i.e., \({{{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{E}}}}^{*}\), \({{{\rm{\delta }}}{{\bf{B}}}}^{*}\), \({\delta {n}_{e}}^{*}\), \({{{\rm{\delta }}}{{{\bf{V}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{*}\), and \({{{\rm{\delta }}}({n}_{e}{{{\bf{V}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}})}^{*}\). Then, calculate the spectra of anomalous terms via

where \( < {n}_{e} > \) and \( < {{\bf{B}}} > \) are the background electron density and magnetic field calculated via the low-pass filter below the frequency of EM fluctuations53, for example, it is 1 Hz for event 2.

The uncertainties of anomalous terms are estimated using the spectral average method as well, which incorporates uncertainties from the electron moments and assumes a 10% uncertainty in the gain of the electric field53. The results indicate that the uncertainty of \({{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{EM}}}}\) is generally smaller than that of \({{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{ES}}}}\) and \({{\bf{D}}}\) terms, as shown in Figs. 3b and 4e, m. The values of \({{{\bf{T}}}}_{{{\rm{EM}}}}\) within the EDR are greater than their associated uncertainties, suggesting that the results are reliable.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. MMS data were available at https://lasp.colorado.edu/mms/sdc/public/about/browse-wrapper/. Source data required to generate the figures in this paper can be found at https://zenodo.org/records/1724773078.

Code availability

All figures and data analyses were performed using the IRFU-Matlab data analysis package, which is available at https://github.com/irfu/irfu-matlab.

References

Dungey, J. W. Interplanetary magnetic field and the auroral zones. Phys. Rev. Lett. 6, 47–48 (1961).

Deng, X. H. & Matsumoto, H. Rapid magnetic reconnection in the Earth’s magnetosphere mediated by whistler waves. Nature 410, 557–560 (2001).

Hesse, M. & Cassak, P. A. Magnetic reconnection in the space sciences: past, present, and future. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 125, e2018JA025935 (2020).

Bransgrove, A., Ripperda, B. & Philippov, A. Magnetic hair and reconnection in black hole magnetospheres. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 055101 (2021).

Most, E. R. & Philippov, A. A. Reconnection-powered fast radio transients from coalescing neutron star binaries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 245201 (2023).

Xie, Y. et al. Origin of FRB-associated X-ray burst: QED magnetic reconnection. Sci. Bull. 68, 1857–1861 (2023).

Gary, S. P. & Madland, C. D. Electromagnetic electron temperature anisotropy instabilities. J. Geophys. Res. 90, 7607–7610 (1985).

Yan, X. et al. Fast plasmoid-mediated reconnection in a solar flare. Nat. Commun. 13, 640 (2022).

Angelopoulos, V. et al. Tail reconnection triggering substorm onset. Science 321, 931–935 (2008).

Shay, M. A., Drake, J. F., Eastwood, J. P. & Phan, T. D. Super-Alfvénic propagation of substorm reconnection signatures and poynting flux. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 065001 (2011).

Cassak, P. A. & Shay, M. A. Scaling of asymmetric magnetic reconnection: general theory and collisional simulations. Phys. Plasmas 14, 102114 (2007).

Daughton, W. et al. Transition from collisional to kinetic regimes in large-scale reconnection layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 065004 (2009).

Zhao, Z. et al. Laboratory observation of plasmoid-dominated magnetic reconnection in hybrid collisional-collisionless regime. Commun. Phys. 5, 247 (2022).

Burkhart, G. R., Drake, J. F. & Chen, J. Magnetic reconnection in collisionless plasmas: prescribed fields. J. Geophys. Res. 95, 18833 (1990).

Biskamp, D., Schwarz, E. & Drake, J. F. Ion-controlled collisionless magnetic reconnection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 3850–3853 (1995).

Øieroset, M., Phan, T. D., Fujimoto, M., Lin, R. P. & Lepping, R. P. In situ detection of collisionless reconnection in the Earth’s magnetotail. Nature 412, 414–417 (2001).

Bessho, N. & Bhattacharjee, A. Collisionless reconnection in an electron-positron plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 245001 (2005).

Torbert, R. B. et al. Estimates of terms in Ohm’s law during an encounter with an electron diffusion region: ESTIMATES OF TERMS IN OHM’S LAW. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 5918–5925 (2016).

Hesse, M., Neukirch, T., Schindler, K., Kuznetsova, M. & Zenitani, S. The diffusion region in collisionless magnetic reconnection. Space Sci. Rev. 160, 3–23 (2011).

Liu, Y.-H., Daughton, W., Karimabadi, H., Li, H. & Roytershteyn, V. Bifurcated structure of the electron diffusion region in three-dimensional magnetic reconnection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 265004 (2013).

Le, A. et al. Drift turbulence, particle transport, and anomalous dissipation at the reconnecting magnetopause. Phys. Plasmas 25, 062103 (2018).

Egedal, J. et al. Spacecraft observations of oblique electron beams breaking the frozen-in law during asymmetric reconnection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 055101 (2018).

Egedal, J. et al. Pressure tensor elements breaking the frozen-in law during reconnection in earth’s magnetotail. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 225101 (2019).

Genestreti, K. J. et al. MMS observation of asymmetric reconnection supported by 3-D electron pressure divergence: OHM’S law for new MMS EDR event. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 123, 1806–1821 (2018).

Papadopoulos, K. A review of anomalous resistivity for the ionosphere. Rev. Geophys. 15, 113–127 (1977).

Huba, J. D., Gladd, N. T. & Papadopoulos, K. The lower-hybrid-drift instability as a source of anomalous resistivity for magnetic field line reconnection. Geophys. Res. Lett. 4, 125–128 (1977).

Aparicio, J., Haines, M. G., Hastie, R. J. & Wainwright, J. P. Fast reconnection due to localized anomalous resistivity. Phys. Plasmas 5, 3180–3186 (1998).

Ji, H. et al. Electromagnetic fluctuations during fast reconnection in a laboratory plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 115001 (2004).

Che, H., Drake, J. F. & Swisdak, M. A current filamentation mechanism for breaking magnetic field lines during reconnection. Nature 474, 184–187 (2011).

Price, L. et al. The effects of turbulence on three-dimensional magnetic reconnection at the magnetopause. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 6020–6027 (2016).

Silin, I., Büchner, J. & Vaivads, A. Anomalous resistivity due to nonlinear lower-hybrid drift waves. Phys. Plasmas 12, 062902 (2005).

Yoo, J. et al. Anomalous resistivity and electron heating by lower hybrid drift waves during magnetic reconnection with a guide field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 145101 (2024).

Cao, D. et al. MMS observations of whistler waves in electron diffusion region: whistlers in electron diffusion region. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 3954–3962 (2017).

Zhong, Z. H. et al. Evidence for whistler waves propagating into the electron diffusion region of collisionless magnetic reconnection. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097387 (2022).

Moritaka, T., Horiuchi, R. & Ohtani, H. Anomalous resistivity due to kink modes in a thin current sheet. Phys. Plasmas 14, 102109 (2007).

Che, H. How anomalous resistivity accelerates magnetic reconnection. Phys. Plasmas 24, 082115 (2017).

Fermo, R. L., Drake, J. F. & Swisdak, M. secondary magnetic islands generated by the kelvin-helmholtz instability in a reconnecting current sheet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 255005 (2012).

Zhong, Z. H. et al. Evidence for secondary flux rope generated by the electron kelvin-helmholtz instability in a magnetic reconnection diffusion region. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 075101 (2018).

Fujimoto, K. & Sydora, R. D. Electromagnetic turbulence in the electron current layer to drive magnetic reconnection. ApJL 909, L15 (2021).

Daughton, W. et al. Role of electron physics in the development of turbulent magnetic reconnection in collisionless plasmas. Nat. Phys. 7, 539–542 (2011).

Fujimoto, K. & Sydora, R. D. Plasmoid-induced turbulence in collisionless magnetic reconnection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 265004 (2012).

Khotyaintsev, Y. V., Graham, D. B., Norgren, C. & Vaivads, A. Collisionless magnetic reconnection and waves: progress review. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 6, 70 (2019).

Zhou, M. et al. Magnetospheric multiscale observations of an ion diffusion region with large guide field at the magnetopause: current system, electron heating, and plasma waves. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 123, 1834–1852 (2018).

Zhou, M. et al. Observation of waves near lower hybrid frequency in the reconnection region with thin current sheet: lower hybrid waves with reconnection. J. Geophys. Res. 114, A02216 (2009).

Roytershteyn, V., Daughton, W., Karimabadi, H. & Mozer, F. S. Influence of the lower-hybrid drift instability on magnetic reconnection in asymmetric configurations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 185001 (2012).

Roytershteyn, V. et al. Electromagnetic instability of thin reconnection layers: comparison of three-dimensional simulations with MRX observations. Phys. Plasmas 20, 061212 (2013).

Cozzani, G. et al. Structure of a perturbed magnetic reconnection electron diffusion region in the earth’s magnetotail. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 215101 (2021).

Fujimoto, K. & Sydora, R. D. The electron diffusion region dominated by electromagnetic turbulence in the reconnection current layer. Phys. Plasmas 30, 022106 (2023).

Liu, Y.-H. et al. ohm’s law, the reconnection rate, and energy conversion in collisionless magnetic reconnection. Space Sci. Rev. 221, 16 (2025).

Rogers, B. N., Drake, J. F. & Shay, M. A. The onset of turbulence in collisionless magnetic reconnection. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 3157–3160 (2000).

Price, L. et al. Turbulence in three-dimensional simulations of magnetopause reconnection. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 122, 11,086–11,099 (2017).

Ng, J., Yoo, J., Chen, L.-J., Bessho, N. & Ji, H. Kinetic simulations underestimate the effects of waves during magnetic reconnection. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, L042072 (2024).

Graham, D. B. et al. Direct observations of anomalous resistivity and diffusion in collisionless plasma. Nat. Commun. 13, 2954 (2022).

Burch, J. L., Moore, T. E., Torbert, R. B. & Giles, B. L. magnetospheric multiscale overview and science objectives. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 5–21 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. Lower-hybrid wave structures and interactions with electrons observed in magnetotail reconnection diffusion regions. JGR Space Phys. 127, e30109 (2022).

Lu, S. et al. Magnetotail reconnection onset caused by electron kinetics with a strong external driver. Nat. Commun. 11, 5049 (2020).

Huang, S. Y. et al. Observations of the electron jet generated by secondary reconnection in the terrestrial magnetotail. ApJ 862, 144 (2018).

Farrugia, C. J. et al. An encounter with the ion and electron diffusion regions at a flapping and twisted tail current sheet. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 126, e2020JA028903 (2021).

Scudder, J. D. et al. First resolved observations of the demagnetized electron-diffusion region of an astrophysical magnetic-reconnection site. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 225005 (2012).

Graham, D. B., Khotyaintsev, Y.uV., Vaivads, A. & André, M. Electrostatic solitary waves and electrostatic waves at the magnetopause. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 121, 3069–3092 (2016).

Graham, D. B. et al. Universality of lower hybrid waves at earth’s magnetopause. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 124, 8727–8760 (2019).

Yoo, J. et al. Whistler wave generation by anisotropic tail electrons during asymmetric magnetic reconnection in space and laboratory. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 8054–8061 (2018).

Daughton, W. Electromagnetic properties of the lower-hybrid drift instability in a thin current sheet. Phys. Plasmas 10, 3103–3119 (2003).

He, J. et al. Direct measurement of the dissipation rate spectrum around ion kinetic scales in space plasma turbulence. ApJ 880, 121 (2019).

Hull, A. J. et al. Energy transport and conversion within earth’s supercritical bow shock: the role of intense lower-hybrid whistler waves. JGR Space Phys. 129, e2023JA031630 (2024).

Swanson, D. G. Plasma Waves (Institute of Physics Pub, 2003).

Yoon, Y. D., Yun, G. S., Wendel, D. E. & Burch, J. L. Collisionless relaxation of a disequilibrated current sheet and implications for bifurcated structures. Nat. Commun. 12, 3774 (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. Quantifying wave–particle interactions in collisionless plasmas: theory and its application to the alfvén-mode wave. ApJ 930, 95 (2022).

Mozer, F. S., Wilber, M. & Drake, J. F. Wave associated anomalous drag during magnetic field reconnection. Phys. Plasmas 18, 102902 (2011).

Price, L., Swisdak, M., Drake, J. F. & Graham, D. B. Turbulence and transport during guide field reconnection at the magnetopause. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 125, e2019JA027498 (2020).

Le, A. et al. Three-dimensional stability of current sheets supported by electron pressure anisotropy. Phys. Plasmas 26, 102114 (2019).

Russell, C. T. et al. The magnetospheric multiscale magnetometers. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 189–256 (2016).

Pollock, C. et al. Fast plasma investigation for magnetospheric multiscale. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 331–406 (2016).

Ergun, R. E. et al. The axial double probe and fields signal processing for the mms mission. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 167–188 (2016).

Lindqvist, P.-A. et al. The spin-plane double probe electric field instrument for MMS. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 137–165 (2016).

Swisdak, M. Quantifying gyrotropy in magnetic reconnection. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 43–49 (2016).

Zenitani, S., Hesse, M., Klimas, A. & Kuznetsova, M. New measure of the dissipation region in collisionless magnetic reconnection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 195003 (2011).

Zhong, Z. zhihongzhong_NCOMMS-24-74477A. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.17247730 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the entire MMS team and MMS Science Data Center for providing high-quality data for this study. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) grants 42525404 (M.Z.), 42474213 (Z.H.Z.), 42130211 (X.H.D.), 42104156 (Z.H.Z.), and 42074197 (M.Z.), and the Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation grant 20224BAB211021 (Z.H.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H.Z. and M.Z. conceived the idea of this study, carried out the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. D.B.G., Y.P., Y.V.K., L.J.S., H.M.L., R.X.T., and X.H.D. participated in the interpretation of the data and the preparation of the manuscript. All the authors made significant contributions to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Homa Karimabadi, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhong, Z.H., Zhou, M., Graham, D.B. et al. Electromagnetic viscosity supported anomalous electric field in the electron diffusion region of collisionless magnetic reconnection. Nat Commun 16, 10519 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65535-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65535-z