Abstract

Ordered nanostructured magnetic networks offer a versatile platform for studying magnetic frustration, reconfigurable magnonics, and neuromorphic computing. Their fabrication, however, often relies on complicated and expensive nanolithography. Here, we demonstrate an electrochemical strategy for growing large-area magnetic networks composed of self-organized triangular motifs separated by periodic parallel ridges. The ridges arise deterministically from voltage-controlled electrodeposition, while the regions between them undergo self-organization: cobalt nucleates, bifurcates, and assembles into either solid or hollow triangular units depending on the growth conditions. The global network morphology is dictated by the waveform of the applied voltage. These triangular structures host diverse magnetic states, including vortex-like and macro-spin-like configurations, and exhibit nonlinear responses to external magnetic fields. Our approach combines macroscopically controlled, deterministic growth and microscopic self-organization, providing a scalable pathway for fabricating complex nanostructures. The resulting magnetic networks show potential as physical reservoirs for neuromorphic computing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interconnected magnetic networks have been intensely studied to explore dynamic behaviors of magnetic domain textures, domain wall automotion, reconfigurable magnonics, and artificial “spin-ice,” etc1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. The effective magnetic charges in the networks, induced by domain walls or magnetic frustrations at the network intersections, may serve as information carriers. Propagation of magnetic charges in the networks can be driven by the magnetic field, spin-polarized current, or radio frequency electromagnetic fields9,10,11, enabling device concepts to memorize, encode, and process information with low energy cost and high efficiency12,13,14. For example, magnetic Kagome lattices have been fabricated to explore domain nucleation/propagation and annihilation processes under magnetic field cycling6,15. Three-dimensional artificial spin ice systems have been constructed to investigate magnetic charge dynamics7. The nanostructured magnetic networks may serve as a promising platform for investigating reconfigurable logic5,12, magnonic devices13,14, or platforms for neuromorphic computing9. The dynamic complexity of magnetic networks yields highly nonlinear responses to inputs, while their non-volatility enables the storage of previous inputs. These characteristics make them candidates for physical reservoirs, potentially replacing the algorithmic implementation of reservoir computation in software to achieve more energy-efficient computation9,16,17.

Traditionally, nanoscale magnetic network fabrication relies on sophisticated top-down nanolithography, which involves multiple steps that are often costly and time-consuming18,19,20. In contrast, bottom-up self-organized growth can generate nanostructures cost-effectively over large areas21,22,23; however, it often lacks strict long-range order23,24,25,26,27. As one of the widely used bottom-up techniques, electrochemical deposition has been applied in nanostructure fabrication owing to its flexible, inexpensive, and versatile performance20,28. However, if the electrodeposit grows in free space, the mass transport of the ions in the electrolyte, controlled by the electric field and other factors such as gravitational convection or electroconvection, could be highly complex, and the morphology of the deposit can vary dramatically29,30,31,32. To confine the space for electrodeposition, various types of templates, such as anode aluminum oxide, close-packed polymer spheres, and customizable two-photon polymerization structures, have been introduced to assist electrodeposition33,34,35. With these templates, magnetic nanostructures ranging from hexagonally packed nanowires, helical nanowires, to tetrapod structures have been fabricated, where abundant magnetic charge dynamics and their applications have been explored33,34,35,36. However, these bottom-up strategies critically rely on the fabrication of templates. An approach that bridges the gap between top-down lithography and bottom-up self-organization is highly desirable to achieve ordered nanostructures over macroscopic scales to address these challenges.

Here, we report on the direct electrochemical growth of two-dimensional magnetic networks without introducing any template, achieved within a trapped electrolyte layer37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. The resulting networks consist of periodic ridges with their longitudinal direction perpendicular to the direction of interfacial growth. Along the ridges, cobalt electrodeposits nucleate and develop into bifurcated branches via self-organization. Depending on the growth conditions, these bifurcated branches eventually evolve into hollow or solid triangular patterns. The spatial periodicity, including the size and shape of the triangular patterns, as well as the height of the ridges, can be modulated by the applied voltage in electrodeposition. On the triangular pattern, magnetic force microscopy reveals vortex-like magnetic flux-closure configurations and macro-spin-like configurations in the initial and remanent magnetic states. The discrete changes of the magnetic states under the applied magnetic field demonstrate the nonlinear dependence of the magnetization of the network on the external field. Furthermore, micromagnetic simulations show the potential of the magnetic network to serve as a physical reservoir. Owing to the intrinsic randomness introduced by self-organization, these magnetic networks offer a compelling platform for exploring complex magnetization dynamics and hold promise for neuromorphic applications.

Results

Electrochemical growth of magnetic networks

The electrochemical growth is carried out in a layer of concentrated electrolyte trapped between the boundary of the electrodeposition cell and the ice of electrolyte CoSO4 using a method reported in refs. 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45 with modification. Initially, the aqueous solution of CoSO4 (0.02 M) in the electrodeposition cell is carefully solidified by decreasing the temperature with a Peltier element and a circulating thermostat underneath serving as the heat sink. Great care is taken in nucleating and solidifying the electrolyte to guarantee that the electrolyte ice is single-crystalline. Due to the partitioning effect during solidification44,45, CoSO4 is partially expelled from the ice into the aqueous electrolyte solution in front of the solid-liquid interface. Thus, the concentration of the remaining electrolyte continues to increase. When equilibrium is reached at the set temperature, a highly concentrated CoSO4 electrolyte layer with a thickness of a few hundred nanometers is formed between the ice and the substrate37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45, where our electrodeposition will be carried out.

We apply a sinusoidal voltage signal (0.7 V, 2 Hz) superimposed on a constant voltage (1.4 V) to electrodeposit cobalt nanostructures, which initiate from the cathode and extend on the substrate towards the anode, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. The growth direction of the electrodeposit is illustrated by the white arrow in Fig. 1b. During this lateral extension of electrodeposit, the preferred nucleation site is the concave corner of the electrodeposit and the substrate38,40. Hence, the electrodeposit develops firmly on the substrate surface. An enlarged micrograph of the cobalt electrodeposit reveals that its morphology changes periodically from a triangular pattern to a straight ridge, resulting in a network pattern (Fig. 1b). The waveform of the voltage signal is shown in Fig. 1c. Figure 1d shows an atomic force microscopy (AFM) scan of a typical morphology of the network. The height profiles in Fig. 1e indicate that the ridge thickness is about 180 nm, whereas the thickness of the triangular pattern is about 70 nm. Figure 1f, g shows a transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of the network and the corresponding selected area electron diffraction, indicating that the network is polycrystalline and the crystallites possess an hcp structure.

a The illustration of the setup for voltage-controlled electrochemical growth in the trapped thin layer of electrolyte. The Peltier element and the heat sink are used to control the temperature of the cell to freeze the electrolyte or melt the ice of the electrolyte. The signal generator and the laptop program a specific voltage pattern for electrodeposition. b SEM micrographs of the network deposited in the trapped thin layer of electrolyte. The white arrow indicates the direction of network growth. The right panel is the enlarged micrograph of the orange dotted box in the left panel. c The programmed altering voltage applied to deposit the network shown in (b). d The surface plot of the network obtained by AFM measurement. e The height profiles corresponding to the purple and cyan dotted lines in (d). f Bright-field TEM micrograph of the electrodeposited network. g, The electron diffraction pattern of the selected area X, as marked in (f). The diffraction obtained in the triangular pattern shows the same structure, as shown in the Supplementary Note 7. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To identify how the cobalt network develops at different stages of applied electric voltage, we intentionally terminate the interfacial growth at specific stages. Figure 2a shows the waveforms of the applied voltages with different colors, and the corresponding electrodeposit morphologies are illustrated in Fig. 2b–f. At the rising edge of an electric voltage, the metal starts to nucleate (Fig. 2c) and gradually develops into triangular patterns (Fig. 2d, e). The applied voltage increases during this process, causing more cations to be driven to the growing interface. Hence, the triangle pattern becomes wider until the applied voltage reaches its maximum, as illustrated in Fig. 2e. After that, as the applied voltage drops, the Co nucleation rate decreases, yet the existing cobalt nuclei generated earlier at the higher voltage continue to grow. Meanwhile, the lateral extension of the electrodeposit essentially stops, although the existing nuclei continue to grow larger. Consequently, the foremost growing interface is thickened (Fig. 2b, f). A ridge eventually forms once the neighboring triangles coalesce. Corresponding to the dropping of the applied voltage, the deposit interface does not move forward. Instead, the growth front becomes thicker and forms a ridge. Once the applied voltage increases again, the next nucleation cycle begins, as shown in Fig. 2c. Repeating this process forms a network of triangular patterns separated by thicker ridges. Figure 2 confirms that the ridges are formed at the falling edges of the voltage, and the triangular patterns are nucleated on the ridges at the rising edge of the applied voltage signal.

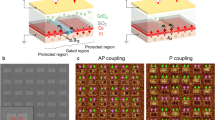

Morphology modulation on the networks

We can modulate the spatial separation of the neighboring ridges by changing the frequency of the applied voltage. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, the spatial separation of the neighboring ridges varies from about 440 to 1550 nm as the frequency of the applied voltage drops from 4 to 1 Hz. Meanwhile, the other parameters are kept unchanged (initial electrolyte concentration: 0.02 M; temperature: −0.5 °C; applied voltage: 1.4 ± 0.7 V, sinusoidal). Figure 3b–d shows the micrographs of the networks when the frequency of the applied voltage is set to 3, 2, and 1.33 Hz, respectively. We observe that when the frequency is set to 3 Hz, the triangular patterns between neighboring ridges are primarily solid, as shown in Fig. 3b. As the frequency decreases to 2 Hz, some of the triangular patterns become hollow. When the frequency drops to 1.33 Hz, hollow triangular patterns are observed more frequently (Fig. 3d).

a The relationship between the spatial periodicity and the frequencies of the alternating voltage. The inset defines the spatial periodicity. The error bars signify standard deviations. A total of 21 periods were measured for each frequency. b–d The SEM images of the magnetic network deposited by the sinusoidal voltage with 3 Hz, 2 Hz, and 1.33 Hz frequencies, respectively. e The relationship between the distance of the neighboring nucleation sites and the temperatures. The inset shows the typical length of two adjacent nucleation sites in the measurement. The error bars signify standard deviations. A total of 72 triangular patterns were measured for each temperature. f–h SEM micrographs of the network electrodeposited at −0.5, −0.9, and −1.8 °C, respectively. The yellow dashed circles in (f) illustrate the grown hollow triangular patterns. The cyan dashed circles in (g) demonstrate the solid triangular patterns. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The cobalt network morphology is highly sensitive to temperature during electrodeposition. We conducted the experiment at temperatures of −0.5, −0.9, −1.3, and −1.8 °C, respectively, while keeping all other experimental conditions unchanged (initial electrolyte concentration: 0.02 M, applied voltage: 1.4 ± 0.7 V, sinusoidal signal frequency: 2 Hz). Figure 3e–h shows the typical electrodeposit morphologies grown in different conditions. The statistics indicate that the average separation of adjacent nucleation sites of the triangular pattern decreases with decreasing temperature (Fig. 3e). Accordingly, the overall morphology of the networks becomes more compact. When the temperature reaches -1.8 °C, a compact film instead of triangular patterns appears between the ridges45.

Magnetic characterization of the networks

Magnetic domain structures on the cobalt networks are investigated by magnetic force microscopy (MFM), which detects the out-of-plane magnetic stray field above the sample surface. Figure 4a, b shows the typical AFM and the corresponding MFM micrograph of an as-grown cobalt network. The network was electrodeposited at −0.5 °C with a sinusoidal voltage (amplitude: 0.7 V, frequency: 2 Hz) superimposed on a constant voltage of 1.4 V. The green, yellow, and magenta rectangular dashed boxes in Fig. 4b are labeled for comparison with the other magnetic states later. Figure 4c, e is the enlarged MFM micrographs of the corresponding marked regions in Fig. 4b. In Fig. 4c, the stronger bright and dark MFM signals are detected on the bottom and top parts of the triangular pattern, suggesting that the magnetic state corresponds to a macro-spin-like configuration9,46,47. Figure 4d presents the corresponding macro-spin-like pattern obtained from micromagnetic simulation. The alternating bright and dark regions in Fig. 4e, known as the Landau pattern, correspond to a vortex-like spin texture9,46,47. Figure 4f illustrates the corresponding vortex-like pattern obtained from micromagnetic simulation, where the size and geometry are set based on the AFM measurement.

a Topographic micrograph of the network measured by AFM. b, The corresponding magnetic domain patterns of the network measured by MFM in the as-grown state. The green, yellow, orange, cyan, and magenta boxes are provided in comparison with other magnetic states. c, e Magnified views of the dotted square regions in (b). The macro-spin-like and vortex-like magnetic configurations obtained from micromagnetic simulation by relaxing magnetizations saturated magnetized in -y directions (d) and randomly distributed magnetizations (f). The size and geometry of the simulated network are set according to the AFM measurement. g–j The illustration of the configurations of the external magnetic field applied to the network. The three magnetic field profiles are applied to magnetize or demagnetize the network. k The magnetic domain pattern at remanence after exposure to a 0.02 T magnetic field, as indicated by the magnetic field profile above. The colored boxes are provided for comparison with those shown in (b) as a visual guide. l The magnetic domain at remanence after exposure to a 0.05 T magnetic field. m The magnetic domain pattern after ac demagnetization with a maximum magnetic field of 0.1 T, as shown in (j) above. The dotted circles in (l, m) illustrate that vortex-like magnetic patterns reappear after AC demagnetization. While the dotted boxes in (l,m) show that the macro-spin-like configurations have been switched by the external magnetic field. The MFM images in (c, e, k, l, m) share the same color bar as that inserted in (b).

To study the response of the magnetic domain textures to the variation of the magnetic field, we magnetize the sample by applying an external magnetic field in the configuration shown in Fig. 4g. Three magnetic field profiles in Fig. 4h–j are applied to magnetize or demagnetize the network. The morphology and spin textures of the same area at remanence after being magnetized by a 0.02 T magnetic field are illustrated in Fig. 4a,k. By comparing the green boxed region in Fig. 4b, k, we observe that the vortex-like domain pattern has been replaced by a macro-spin-like one. However, as marked by the green, yellow, and magenta rectangular dashed boxes in Fig. 4b, k, the magnetic configurations in these regions remain unchanged. We further increase the magnetization field to 0.05 T. The remanent magnetic state of the same region is illustrated in Fig. 4l. Most domain textures have been switched to macro-spin-like configurations. To revolve the vortex-like configurations, we demagnetize the same network with an AC magnetic field, as illustrated in Fig. 4j. The demagnetization process was accomplished by a homemade Helmholtz coil with a maximum homogeneous magnetic field of 0.1 T. Figure 4m shows the demagnetized state of the network. The dotted circles in Fig. 4l, m illustrate that vortex-like magnetic patterns reappear after AC demagnetization. Furthermore, the macro-spin-like configurations, highlighted by the dotted boxes in Fig. 4l, m, have been switched with a flipped contrast. Figure 4 confirms that both vortex-like and macro-spin-like magnetic states coexist on the network of solid triangles. The overall magnetic configuration of the network can be controlled by applying an external magnetic field, providing the basis for an analog platform to study the integrated multi-state memristor8,48.

Transport measurements of magnetic networks further reveal that various magnetic states can be distinguished by their magnetoresistance features and the nonlinear magnetoresistance response to the applied magnetic field. Distinct plateaus emerge in magnetoresistance at specific field strengths (Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating variations of the magnetic domain at different magnetic field magnitudes.

Programmable engineering of magnetic networks

Moreover, we can obtain a specific network structure by modulating the applied voltage waveform to encode the network morphology. Figure 5a illustrates the electrodeposited network morphology obtained through a programmed voltage. The network consists of three types of triangular patterns in a spatial period. The red curve represents the AFM height profile along the dotted line indicated underneath. The applied voltage for electrodeposition is illustrated at the bottom of Fig. 5a. The dotted arrows correlate the signals and growth patterns. We find that the thinner triangular patterns are deposited corresponding to the 0.3 s rising edge, while the larger triangle is formed in the 0.5 s rising edge. For the thinner triangle patterns, the ridge at the end of the pattern possesses a low height due to the sharp falling edge of the electric voltage. In contrast, for the voltage with a 0.5 s falling edge, the generated ridge has a height of 200 nm, as shown in Fig. 5a. This allows us to design and grow a desired magnetic network with specific triangular patterns and ridge heights by controlling the waveform of the applied voltage.

a The SEM image of the cobalt network electrodeposited by the programmed voltage. The superimposed red curve is the height profile measured by AFM. The dotted blue and red arrows indicate the correlation between signals and growth patterns. b The macroscopic SEM view of the network. c, Topographic micrograph of the network measured by AFM. d The corresponding magnetic domain patterns of the network in the as-grown state. e The enlarged MFM of the dotted square in d superposed with topography information as indicated by the dotted square in (c). f, Topographic micrograph of the network measured by AFM of the same network. g The magnetic domain patterns at remanence after exposure to a 0.1 T magnetic field along the direction as shown by the white arrow in (f). h The enlarged MFM of the dotted square in (g) superposed with topography information as indicated by the dotted square in (f). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We characterize the magnetic states of the network grown via the programmed voltage, as illustrated in Fig. 5c–h. Figure 5c, d shows the topography of the network and the as-grown magnetic state. To achieve a more direct connection between the topography and the magnetic signals, we superimpose the topography of the network to the MFM image (boxed region in Fig. 5c, d), as demonstrated in Fig. 5e. In the dotted circles in Fig. 5e, the bright and dark textures are mirror symmetric in contrast, suggesting that the vortex-like textures possess opposite chirality. On the other hand, in the dotted rectangular box in Fig. 5e, dark and bright spots exist at the intersections of the thinner magnetic patterns. The strong brightness of the MFM signal in the center of the dotted box suggests a maximum local positive effective magnetic charge there. The alternating dark and bright spots suggest that macro-spin-like configurations exist on the thinner patterns due to the shape anisotropy.

The directions of the magnetization on the thinner patterns point from the dark region to the bright region, as indicated by the white arrows in Fig. 5e. Therefore, both vortex-like and macro-spin-like configurations coexist in the network.

To switch the magnetic states of the networks, we apply a 0.1 T magnetic field to magnetize the sample and then reduce the magnetic field slowly to zero. The morphology and spin textures of the sample at remanence are illustrated in Fig. 5f, g, respectively. We select the same region and superimpose the topography and magnetic information in Fig. 5h. By comparing the MFM in the dotted circles in Fig. 5e, h, we observe that the initial vortex-like configuration has evolved into a macro-spin-like configuration. The magnetization direction of the thinner magnetic patterns is illustrated by the white arrows in the dotted box in Fig. 5h. Compared with the MFM micrograph in the dotted box in Fig. 5e, the magnetic signal sensed by the MFM tip after magnetization at the intersection of the three bar magnets is much weaker than that in the as-grown state, suggesting that the external magnetic field has removed the maximum positive effective magnetic charge. In the magnetic network grown by a programmed voltage, vortex-like and macro-spin-like magnetic configurations prefer to exist in the broadened and thinner triangles, respectively. The huge number of magnetic states in the network can be introduced by encoding the network with triangles of various sizes, and external magnetic fields can subsequently modify the magnetic states. This feature makes the network a potential platform for exploring magnetization dynamics and neuromorphic computing concepts such as reservoir computing8,9.

Simulation of magnetic network reservoirs

Reservoir computing framework exploits the dynamics of a nonlinear system as a computational resource for processing time-dependent data. The reservoir transforms an input signal into a high-dimensional representation via its intrinsic dynamics, while only the output layer (a simple linear readout) is trained. The abundance of magnetic states and the nonlinear response of magnetization switching to external magnetic fields make the magnetic network a potential platform for reservoir computing. The history-dependent behavior of the magnetic state (Supplementary Fig. 2) provides the fading memory required in reservoir computing in dealing with temporal information. Here, we demonstrate the potential application of magnetic networks as physical reservoirs via micromagnetic simulation.

Figure 6a illustrates the schematic of the magnetic network reservoir computing with three layers: an input layer, a reservoir layer, and an output layer. In the input layer, the raw data \({{{\bf{u}}}}(t)\) is encoded into a series of external magnetic fields with varying strengths \({{{\bf{H}}}}(t)\). The encoded external magnetic field is applied to magnetize the magnetic network. The magnetic network is retrieved from a SEM micrograph of a self-organized electrodeposit, as shown in Fig. 6a. Its magnetic state (Fig. 6b) is characterized by exciting spin waves in an alternating magnetic field and then measuring the corresponding ferromagnetic resonance spectrum49. The amplitudes of the different frequency bins are used as independent outputs \({x}_{i}(t)\). In this way, the magnetic network reservoir nonlinearly maps the input data into a high-dimensional space to isolate and capture potential features. The high-dimensional signal is then sent to the output layer for offline training of the output weights by using ridge regression. The dataset is divided into a training set and a test set. We fit the weights on the training set and compare the mean squared error (MSE) of the predicted output and the target output on the test set to evaluate the performance. As a control experiment, the performance of neural networks trained with the raw data, i.e., bypassing the reservoir, is also evaluated.

a Schematic of the magnetic network reservoir computing scheme. Input values from −1 to 1 are mapped to the field range of −100 to 100 mT as the input to the reservoir. The ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) spectra corresponding to the different magnetic states of the magnetic nanonetwork are used as the output of the physical reservoir. The network pattern of the simulation is retrieved from the SEM micrograph of a self-organized network. b Distribution of the magnetization of the magnetic network at different moments of the magnetic field signal input. Transformation of sine wave input datasets to target waveforms of sawtooth wave (c, d), square wave (e, f), sin2(t) wave (g, h). Future prediction of t + 15(i, j) and t + 20 (k, l) for a Mackey-Glass chaotic differential time series. In both tasks, the training results of applying the magnetic network reservoir exhibited superior alignment with the target waveform and had a smaller MSE than the training results of bypassing the reservoir. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We first evaluate the performance of the magnetic network reservoir for the fundamental task of performing nonlinear signal transformation. The training targets of the neural network are to convert the periodic input waveform to different target signals. This requires the reservoir to transform the input signal nonlinearly into a higher-dimensional feature space. The results of transforming a sine wave input dataset into target outputs of sawtooth, square, sin2(t) waves are shown in Fig. 6c–h. The magnetic network reservoir accurately performs all three nonlinear transformations on the input sequence of the test set, yielding lower MSE values than those predicted by neural networks trained on the raw data. The latter fails to predict nonlinear waveform transformations, merely reproducing the input waveform.

Next, we evaluate the temporal signal processing capability of the magnetic network reservoir in predicting the Mackey–Glass system. Mackey–Glass equation is a time-delay differential equation that exhibits complex dynamic behavior, including chaos, due to its time-delay term. This equation is widely utilized as a benchmark for assessing reservoir performance. The target of the task is to predict the time series at the moment t + τ from the time series at the moment t, with τ as the time span. Figure 6i, j, as well as Fig. 6k, l demonstrate the predictions for t + 15 and t + 20. The projections of the magnetic network more accurately align with the target waveform compared to those predicted by neural networks trained with the raw data. The projections via the magnetic network also exhibit a lower MSE, demonstrating the potential of magnetic networks for application in physical neuromorphic computing.

Discussion

It is essential to understand the growth mechanism of the cobalt network. Once electrodeposition begins, cobalt atoms at the anode lose electrons, forming cations that diffuse or migrate toward the cathode. These cations are reduced at the cathode surface and complete the electrodeposition process. In our system, electrodeposition takes place in a trapped, highly concentrated electrolyte layer, where reduced cobalt atoms preferentially nucleate on the substrate via a concave-corner-mediated mechanism38,39,40. The network formation thus results from an interplay between deterministic growth and self-organization. Under sinusoidal voltage, the nucleation rate oscillates, increasing sharply during voltage rises. Guided by the coupled electric and concentration fields, electrodeposits extend from the nucleation sites toward the anode.

In a two-dimensional electrodeposition system, it has been well established that a pair of vortices may exist between neighboring electrodeposit branches29,30,31,32. Experimentally, it has been observed that due to electroconvection between neighboring growing tips, part of the cations move towards the growth front from both sides of the tip, leading to the gradual widening of the growth front. Driven by this effect, the neighboring branches approach each other and eventually form a loop pattern29. In our electrodeposition system, electroconvection could remain active and affect the interfacial growth behavior. The reason is that the electrolyte concentration is very high in our trapped electrolyte layer, and the electric charges around the electrodeposit tips are sufficiently high to initiate electroconvection without requiring extra H3O+29. This effect broadens the tips and enables neighboring branches to meet, forming connected triangular motifs (yellow dashed circles in Fig. 2d, e).

Electroconvection also establishes a higher local cation concentration near the two upper corners of each triangle. During subsequent voltage cycles, new nucleation preferentially occurs at these corners. As a result, a periodic network of triangular meshes emerges, even though the electrolyte layer is only a few hundred nanometers thick42.

The morphology of the triangular units depends on the strength of electroconvection. Under strong convection—arising from high electrolyte concentration or elevated temperature30,31—cation transport to the corners greatly exceeds that to the central region, causing branches to broaden or bifurcate rapidly (Fig. 3f). This imbalance favors hollow triangular patterns (yellow dashed circles, Fig. 3f). In contrast, when cation transport remains balanced, the front expands laterally and yields solid triangular motifs (cyan dashed circles, Fig. 3g). Most growth conditions lie between these extremes, producing hybrid morphologies in which the triangle’s center is concave while the edges are elevated (white dashed boxes, Fig. 4a). Such variations indicate that local growth conditions are spatially inhomogeneous in electrodeposition.

Conventionally, convection diminishes when the thickness of the liquid layer shrinks. For example, buoyancy-driven convection is usually characterized by the Rayleigh number; this dimensionless parameter is proportional to the third power of the solution layer thickness50. Electroconvection is primarily controlled by the electric field29. In the trapped electrolyte layer, adhesion on the electrolyte at the boundaries further suppresses convection, reducing cation delivery to the tips. As indicated in Fig. 3f–h, the formation of a network with well-defined triangular meshes occurs only when the temperature is above −0.5 °C. At –0.9 °C, the thinner electrolyte film suppresses tip broadening, and new nucleation arises almost directly in front of existing branches. At –1.8 °C, an even thinner film produces compact deposit film between ridges (Fig. 3h). Meanwhile, a parallel periodic array of nanowires can be achieved if we gently etch away the connecting film connecting the ridges42,43.

The electrolyte concentration in this system is governed by temperature through the partitioning effect44,45. Meanwhile, the nucleation rate depends on the collision frequency of reduced atoms at the cathode, which increases with higher electrolyte concentration. Thus, as temperature decreases and electrolyte concentration rises, the nucleation density increases evidently, consistent with the dense deposit structures observed at low temperatures (Fig. 3f–h).

Beyond growth mechanisms, the resulting magnetic cobalt networks provide a promising platform for exploring dynamic magnetic textures1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. As illustrated in Fig. 4, vortex-like and macro-spin-like textures coexist in both the initial and remanence states. Each triangular pattern may possess a different magnetic state, which can define 1 or 0 in a binary system, serving as the basis for information storage based on the existence/absence of the vortex-like state at each triangular pattern. Moreover, the network can serve as a platform for integrated multistate memristors7,8. By incorporating both vortex chirality and macro-spin polarity, the system could extend from binary to quaternary encoding, greatly enhancing the capacity for multistate information storage9,10,11,12,13,14.

In addition to information storage, the magnetic network also offers opportunities for neuromorphic computing. Modern artificial intelligence largely relies on graphics processing units, which, while powerful, consume enormous amounts of electrical energy and may become a significant bottleneck for future development. As an alternative, recent studies have shown that the magnetic states in networks, together with their nonlinear responses to external magnetic fields, make them promising candidates for reservoir computing components, capable of operating with reduced training cost and power consumption8,9,17,51. In a reservoir computing framework, time-varying external magnetic fields can encode input signals derived from images, audio, or text9,51. The nanostructured magnetic network acts as the reservoir, exhibiting nonlinear and history-dependent responses to the varying fields. Output signals can then be extracted through measurements of magnetoresistance or ferromagnetic resonance spectra, which will require additional fabrication steps to integrate the necessary electrodes or waveguides.

Traditionally, periodic nanostructures for such purposes are fabricated using lithography-based top-down approaches, which are both time-consuming and costly. Self-organized magnetic networks offer a bottom-up alternative that is inherently scalable and efficient to achieve. Note that the network formation presented in this work combines deterministic growth and self-organization processes. The separation of the ridges is directly controlled by the applied voltage, which is precisely periodic. Yet, the triangular pattern is self-organized, exhibiting various widths and different inter-triangle separations (Fig. 3e). Consequently, each triangular pattern may possess different coercivity and respond differently to an external magnetic field. For this reason, when the external magnetic field applied to magnetize the sample is set at 0.02 T, the magnetization textures of some of the networks remain unchanged, as indicated by the blue, yellow, and magenta boxes in Fig. 4b, k. Yet some regions have turned from vortex-like spin textures to macro-spin-like configurations (e.g., the green squares in Fig. 4b,k). In other words, the triangles respond differently to the external magnetic field. When the magnetic field is enhanced to 0.05 T, the magnetic texture of the triangle patterns becomes more uniform, as indicated in Fig. 4l. Further increasing the magnetic field to 0.1 T, the MFM micrograph remains almost the same as Fig. 4l, suggesting that a magnetic field of 0.05 T has already saturated magnetization of the network along its growth direction.

Moreover, the size of the triangles may vary based on the waveform of the applied voltage (Fig. 5). This feature can generate networks with complex structures, thereby enhancing their capability to respond nonlinearly to external magnetic fields. We expect that our magnetic network, characterized by a certain degree of geometrical randomness stemming from the self-organization of the triangles, may serve as a platform to explore abundant magnetic charge dynamics and be applied to construct multistate memory and memristors as neuromorphic computing components7,8,17,51.

In summary, we demonstrate a distinctive electrodeposition strategy for fabricating magnetic metallic networks, where the ridge periodicity is governed by the frequency of the applied oscillating voltage, and the separation of Co triangles is self-organized and dependent on temperature. The growth processes of the network can be flexibly programmed by encoding the applied voltage with different increasing/falling edges. We observe vortex-like magnetic flux-closure configuration and macro-spin-like flux-open configuration on the magnetic networks. This growth behavior bridges the gap between top-down lithography and bottom-up self-organization. The emergent nonlinear response of the magnetic networks to external magnetic fields provides a spintronic/magnonic platform with potential applications in neuromorphic computing.

Methods

Electrochemical growth

Sample fabrication is carried out in an electrodeposition cell at a temperature below the freezing point of the electrolyte solution. The electrolyte solution is prepared by dissolving analytical regent CoSO4 (Alfa Aesar, 99.5%) in deionized water (Millipore, electric resistivity 18.2 MΩ cm). The initial concentration of the CoSO4 aqueous electrolyte is 0.02 M. A 40 μL electrolyte solution is sandwiched between two rigid boundaries, made of a microscope cover glass and a polished silicon wafer. Two parallel, straight cobalt wires (0.1 mm in diameter, Alfa Aesar, 99.995%) are used as the cathode and anode. The horizontal separation of the electrodes is fixed at 6 mm. The electrodeposition cell is placed in a chamber made of copper. The chamber temperature is controlled by a thermostat circulator (temperature range: −20 °C to 100 °C, accuracy: 0.01 °C, Cole Parmer, Polystat 12108-35). Details of the chamber design can be found in refs. 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. A Peltier element (size: 23 mm × 23 mm × 3.7 mm, with a maximum power of 14.7 W) is placed underneath the electrodeposition cell to stimulate nucleation in solidifying the electrolyte. An optical microscope (Leitz, Orthoplan-Pol) is used to observe the nucleation and growth of the electrolyte ice and the electrodeposition process, utilizing a long-working-distance lens.

In the experiment, the temperature of the circulating refrigerant (50 vol% glycol and 50 vol% deionized water) in the thermostat circulator is set to −1 °C. An electric current is applied to the Peltier element to stimulate the nucleation of electrolyte ice. By carefully controlling the electric current applied to the Peltier element, nucleation and melting of nuclei can be controlled. By repeating this process, we keep only one nucleus of the electrolyte ice in the viewing field of the microscope. After that, the chamber temperature is slowly decreased (at a rate of 0.1 °C h−1) to the target temperature, and the ice nucleus grows stably. Eventually, a flat, uniform, single-crystalline ice of electrolyte is generated. When the equilibrium is reached, a layer of electrolyte is trapped between the ice and the substrates due to the partitioning effect in the solidification process. We carry out electrodeposition in this electrolyte layer.

We use a signal generator (Sony, AFG320) to apply a specific voltage pattern across the electrodes. The applied voltage varies from a constant voltage to a constant voltage superposed with a sinusoidal, triangular, or rectangular voltage. The shape and frequency of the voltage can be programmed. Usually, the electrodeposit nucleates on the silicon substrate or a glass surface. The electrodeposit grows from the cathode towards the anode in the layer of electrolyte trapped between the ice and the substrates. After the electrodeposition, the sample is rinsed with deionized water and dried in a vacuum chamber for further analysis.

Sample characterization

The morphology of the nanostructured electrodeposit is characterized by a field-emission scanning electron microscope (Zeiss, ULTRA 55). The crystalline structure of the material is analyzed by a transmission electron microscope (FEI TEM, Tecnai F20). The height profiles are obtained by a multimode atomic force microscope (Digital Instruments, Nanoscope IIIa). The magnetic state of the magnetic network is characterized by the magnetic force microscopy mode with a lift height of 50 nm. The cantilevers for MFM are commercially purchased from NanosensorTM (force constant 2.8 N m−1, coercivity of ≈250 Oe, effective magnetic moment in the order of 10−13 emu). Micromagnetic simulations are conducted using the OOMMF52 code. The geometrical parameters of the filament in the simulation are based on AFM measurements. The height of the triangle is set to 60 nm. Periodic boundary conditions are applied on the plane of the network. For the cobalt networks, the material parameters are selected as follows: saturation magnetization Ms = 1.4 × 106 A m−1, exchange stiffness Aex = 2.3 × 10−11 J m−1, and uniaxial anisotropy constant Ku = 3.0 × 104 J m−3. The cell size is set as 5 × 5 × 5 nm3, and the dimensionless damping is chosen as 0.5.

Reservoir computing

In the micromagnetic simulations, we constructed a cobalt network with a thickness of 20 nm and an overall size of 3 µm as a reservoir. The pattern of the network is retrieved from the SEM micrograph of a self-organized electrodeposit. The input signal \({{{\bf{u}}}}(t)\) is linearly mapped to a range that is appropriately smaller than the coercive field of the network, thus taking advantage of the nonlinear dependence of magnetization on the magnetic field input.

After applying the input magnetic field along the y direction at each time step, the magnetization distribution of the network is determined. For each magnetic state, a broadband sinc function pulse with a cutoff frequency of 25 GHz is applied along the z direction to excite the spin wave. The pulses lasted for 20 ns, and the magnetization was recorded every 20 ps. The magnetization intensity in the z-direction was then fast Fourier transformed along the time axis to generate the spectrum. This spectrum is then discretized at specific frequency intervals to yield 50 output signals \({{{\bf{x}}}}(t)\) from the reservoir. \({{{\bf{x}}}}(t)=f[{{{{\bf{W}}}}}_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}{{{\bf{u}}}}(t)+{{{{\bf{W}}}}}_{{{{\rm{res}}}}}{{{\bf{x}}}}(t-1)]\) represents the state of the reservoir, where f is a non-linear function, \({{{{\bf{W}}}}}_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\) and \({{{{\bf{W}}}}}_{{{{\rm{res}}}}}\) are input weights and reservoir weights, respectively. The output layer weights are gained by offline training using ridge regression. \({{{{\bf{W}}}}}_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}={{{\bf{Y}}}}{{{{\bf{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}{({{{\bf{X}}}}{{{{\bf{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}+\lambda {{{\bf{I}}}})}^{-1}\), where \({{{\bf{X}}}}\) is a series of inputs, \({{{\bf{Y}}}}\) is a series of target values, and \(\lambda\) is the regularization factor. The reservoir prediction is determined by \(\widetilde{{{{\bf{y}}}}}(t)={{{{{\bf{W}}}}}_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}{{{\bf{x}}}}(t)\). We calculated the MSE of the target series and reservoir prediction to assess reservoir performance according to \({{{\rm{MSE}}}}=\frac{{\sum }_{i=0}^{N-1}{({{{{\bf{y}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}-{\widetilde{{{{\bf{y}}}}}}_{{{{\bf{i}}}}})}^{2}}{N}\), where N is the number of input data points. Mackey-Glass time series are computed from the Mackey-Glass delayed differential equation, where n = 10, time delay τ = 17, a = 0.2, b = 0.1, and the initial condition for the time series \(x(t=0)\) = 1.2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Burks, E. C., Gilbert, D. A., Murray, P. D., Flores, C. & Liu, K. 3D nanomagnetism in low-density interconnected nanowire networks. Nano Lett. 21, 716–722 (2020).

Skjærvø, S. H., Marrows, C. H., Stamps, R. L. & Heyderman, L. J. Advances in artificial spin ice. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 13–28 (2020).

Morgan, J. P., Stein, A., Langridge, S. & Marrows, C. H. Termal ground-state ordering and elementary excitations in artificial magnetic square ice. Nat. Phys. 7, 75–79 (2011).

Skoric, L. et al. Domain wall automotion in three-dimensional magnetic helical interconnectors. ACS Nano 16, 8860–8868 (2022).

Grundler, D. Reconfigurable magnonics heats up. Nat. Phys. 11, 438–441 (2015).

Sun, L. et al. Magnetization reversal in kagome artificial spin ice studied by first-order reversal curves. Phys. Rev. B 96, 144409 (2017).

May, A. et al. Magnetic charge propagation upon a 3D artificial spin-ice. Nat. Comm. 12, 3217 (2021).

Bhattacharya, D. et al. 3D interconnected magnetic nanowire networks as potential integrated multistate memristors. Nano Lett. 22, 10010–10017 (2022).

Gartside, J. C. et al. Reconfigurable training and reservoir computing in an artificial spin-vortex ice via spin-wave fingerprinting. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 460–469 (2022).

Parkin, S. & Yang, S.-H. Memory on the racetrack. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 195–198 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Magnetization switching by magnon-mediated spin torque through an antiferromagnetic insulator. Science 366, 1125–1128 (2019).

Manipatruni, S. et al. Scalable energy-efficient magnetoelectric spin-orbit logic. Nature 565, 35–42 (2019).

Han, J., Zhang, P., Hou, J. T., Siddiqui, S. A. & Liu, L. Mutual control of coherent spin waves and magnetic domain walls in a magnonic device. Science 366, 1121–1125 (2019).

Koerner, C. et al. Frequency multiplication by collective nanoscale spinwave dynamics. Science 375, 1165–1169 (2022).

Shim, W. et al. Hard-tip, soft-spring lithography. Nature 469, 516–520 (2011).

Hu, W. et al. Distinguishing artificial spin ice states using magnetoresistance effect for neuromorphic computing. Nat. Commun. 14, 2562 (2023).

Vidamour, I. T. et al. Reconfigurable reservoir computing in a magnetic metamaterial. Commun. Phys. 6, 1–11 (2023).

Le, B. L. et al. Understanding magnetotransport signatures in networks of connected permalloy nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 95, 060405(R) (2017).

Sun, K. et al. Three-dimensional direct lithography of stable perovskite nanocrystals in glass. Science 375, 307–310 (2022).

Wang, Y., Fedin, I., Zhang, H. & Talapin, D. V. Direct optical lithography of functional inorganic nanomaterials. Science 357, 385–388 (2017).

Li, S. et al. Self-regulated non-reciprocal motions in single-material microstructures. Nature 605, 76–83 (2022).

Jishkariani, D. et al. Dendron-mediated engineering of interparticle separation and self-assembly in dendronized gold nanoparticles superlattices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10728–10734 (2015).

Altomare, M. et al. Molten o-H3PO4: A new electrolyte for the anodic synthesis of self-organized oxide structures—WO3 nanochannel layers and others. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 5646–5649 (2015).

Ozel, T., Bourret, G. & Mirkin, C. Coaxial lithography. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 319–324 (2015).

Wang, H. et al. Hierarchical self-assembly of nanowires on the surface by metallo-supramolecular truncated cuboctahedra. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 5826–5835 (2021).

Guo, B. et al. Vertically aligned porous organic semiconductor nanorod array photoanodes for efficient charge utilization. Nano Lett. 18, 5954–5960 (2018).

Yang, H. et al. Significant Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction at graphene–ferromagnet interfaces due to the Rashba effect. Nat. Mater. 17, 605–609 (2018).

Imtaar, M. A. et al. Nanomagnet Fabrication Using Nanoimprint Lithography and Electrodeposition. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 12, 547 (2013).

Wang, M., Enckevort, W. J. P., Ming, N. B. & Bennema, P. Formation of a mesh-like electrodeposit induced by electroconvection. Nature 367, 438–441 (1994).

Fleury, V., Chazalviel, J. N. & Rosso, M. Theory and experimental evidence of electroconvection around electrochemical deposits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 2492–2495 (1992).

Fleury, V., Chazalviel, J. N. & Rosso, M. Coupling of drift, diffusion, and electroconvection, in the vicinity of growing electrodeposits. Phys. Rev. E 48, 1279–1295 (1993).

Chazalviel, J. N. Electrochemical aspects of the generation of ramified metallic electrodeposits. Phys. Rev. A 42, 7355–7367 (1990).

Xu, L. et al. Synthesis and magnetic behavior of periodic nickel sphere arrays. Adv. Mater. 15, 1562 (2003).

Noori, F. et al. Current density-induced emergence of soft and hard magnetic phases in Fe nanowire arrays. Nanotechnology 34, 075701 (2022).

Zeeshan, M. A. et al. Hybrid helical magnetic microrobots obtained by 3D template-assisted electrodeposition. Small 10, 1284 (2014).

Sahoo, S. et al. Ultrafast magnetization dynamics in a nanoscale three-dimensional cobalt tetrapod structure. Nanoscale 10, 9981 (2018).

Wang, M. et al. Nanostructured copper filaments in electrochemical deposition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 3827–3830 (2001).

Zhang, M. Z. et al. Formation of copper electrodeposits on an untreated insulating substrate. J. Phys. Cond. Matter 16, 695–704 (2004).

Zhang, M. Z. et al. Regular arrays of copper wires formed by template-assisted electrodeposition. Adv. Mater. 16, 409–413 (2004).

Zhang, B. et al. Creating in-plane metallic-nanowire arrays by corner-mediated electrodeposition. Adv. Mater. 21, 3576–3580 (2009).

Huang, X. P. et al. Formation of regular magnetic domains on spontaneously nanostructured cobalt filaments. Adv. Mater. 22, 2711–2716 (2010).

Chen, F. et al. Periodic magnetic domains in single-crystalline cobalt filament arrays. Phys. Rev. B 93, 054405 (2016).

Chen, F. et al. Construction of 3D metallic nanostructures on an arbitrarily shaped substrate. Adv. Mater. 28, 7193–7199 (2016).

Chen, F. et al. Formation of magnetic nanowire arrays by cooperative lateral growth. Sci. Adv. 8, eabk0180 (2022).

Weng, Y. Y. et al. Self-templating growth of copper nanopearl-chain arrays in electrodeposition. Phys. Rev. E 81, 051607 (2010).

García, J. M. et al. Quantitative interpretation of magnetic force microscopy images from soft patterned elements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 656–658 (2001).

Soldatov, I. V. & Schäfer, R. Selective sensitivity in Kerr microscopy. Rev. Sci. Inst. 88, 073701 (2017).

Kou, X. et al. Memory effect in magnetic nanowire arrays. Adv. Mater. 23, 1393–1397 (2011).

Arroo, D. M., Gartside, J. C. & Branford, W. R. Sculpting the spin-wave response of artificial spin ice via microstate selection. Phys. Rev. B 100, 214425 (2019).

Cross, M. C. & Hohenberg, P. C. Pattern formation outside of equilibrium. Rev. Mod. Phys. 65, 851–1112 (1993).

Yokouchi, T. et al. Pattern recognition with neuromorphic computing using magnetic field-induced dynamics of skyrmions. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq5652 (2022).

Donahue, M. J., Porter, D. G. OOMMF User’s Guide, Version 1.0. NISTIR 6376 (1999) http://math.nist.gov/oommf/

Acknowledgements

M.W. and R.P. thank the financial support from the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA1404303 and 2020YFA0211300), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12234010, 11974177, and 61975078), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20233001). R.P. also acknowledges the support of Nanjing University International Collaboration Initiative. K.L. acknowledges support from the US National Science Foundation (DMR−2005108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W. and R.P. conceived and advised the project. F.C., M.W., and R.P. designed the methodology of the fabrication process. F.C. and J.S. fabricated the sample with the help of J.L., F.J., F.W., and ZY. F.C. performed SEM and MFM characterization. X.W. performed the TEM characterization. F.C. and J.S. performed the micromagnetic simulation. J.S. performed the neuromorphic computing tasks. K.L. advised the neuromorphic computing scheme and helped with the data analysis. F.C. and M.W. wrote the original draft. The manuscript was written through the contributions of all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ian Vidamour and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, F., Shan, J., Wang, X. et al. Electrodeposition of magnetic nanonetworks featuring triangular motifs and parallel ridges on a macroscopic scale. Nat Commun 16, 9965 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65589-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65589-z