Abstract

In genetic disease, an accurate expression landscape of disease genes and faithful animal models can facilitate genetic diagnoses and therapeutic advances respectively. Previously, we found that variants in NOS1AP, the gene that encodes nitric oxide synthase 1 adaptor protein, cause monogenic nephrotic syndrome. Here, we determine that an intergenic splice product of NOS1AP/Nos1ap and neighboring C1orf226/Gm7694, which prevents NOS1AP from binding to nitric oxide synthase 1, is the predominant isoform in mammalian kidney transcriptional and proteomic data. Gm7694−/− mice, whose allele exclusively disrupts the intergenic product, develop nephrotic syndrome phenotypes. In two male human subjects with nephrotic syndrome, we identify causative NOS1AP splice variants, including one predicted to abrogate intergenic splicing but initially misclassified as benign based on the canonical transcript. Finally, by modifying genetic background, we generate a faithful mouse model of NOS1AP-associated monogenic nephrotic syndrome that responds to anti-proteinuric treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a leading cause of chronic kidney disease in children1. NS presents with edema, hypoalbuminemia, and proteinuria, arising from disruption of the glomerular filtration barrier comprised primarily of interconnected podocytes2. Treatment-resistant NS (steroid-resistant NS or SRNS) frequently progresses to end-stage kidney disease concomitant with podocyte loss1,2,3. Mendelian genetic forms represent the most severe subset of NS4,5,6,7.

Monogenic NS genes are predominantly expressed in glomerular podocytes8, encoding proteins essential for podocyte development or homeostasis2,9. Patient variants in disease proteins impair podocyte structure and function2,8, causing podocytopathies. For example, variants in >10 genes encoding actin cytoskeleton regulators have been shown to cause nephrotic syndrome in humans and mice10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Despite the interconnected nature of these genetic etiologies, specific treatments are lacking.

Causative genetic variants are detected in 11–30% of SRNS cases4,5,6,7. For families lacking a genetic diagnosis, variant classification can be hindered by transcript annotation based on non-kidney tissues. Understanding kidney-specific isoform expression will facilitate the discovery of additional disease variants and genes, broadening our mechanistic understanding of NS and impacting clinical care for kidney disease patients with an established genetic diagnosis.

We previously discovered that recessive variants in NOS1AP/Nos1ap, affecting N-terminal domains, caused early-onset NS in human subjects and a podocytopathy in C57BL/6-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice20. This locus, which is in synteny between humans and mice, encodes nitric oxide synthase 1 adaptor protein (NOS1AP) (Figs. S1–2)21,22,23. NOS1AP contains an N-terminal phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domain and a C-terminal PDZ binding domain (PDZ-BD), through which it interacts with NOS1 (Figs. S1–4)24,25,26,27,28,29. While NOS1AP is most highly expressed in the central nervous system in humans and rats (Fig. S3)26,27,29, querying of kidney scRNA sequencing data revealed it is highly expressed in podocyte clusters in the kidney20,30,31. We determined that NOS1AP co-localized with actin-based filopodia in podocytes and with podocyte marker nephrin in kidney sections. NS patient variants, which were all within the PTB domain, impaired filopodia formation and podocyte migration20. NOS1AP acted upstream of the NS-associated CDC42/formin pathway, supporting its key role in the actin regulatory network20.

While the C-terminal NOS1AP-NOS1 interaction is important for neuronal NO signaling and required for hippocampal neuron-mediated anxiolysis32,33, impairing NOS1 function did not disrupt NOS1AP-dependent actin remodeling in podocytes in our study20, suggesting an NOS1-independent role for NOS1AP in NS.

We previously described an additional intergenic Nos1ap transcript in rat tissues generated from splicing between the 5’ region of canonical exon 10 and two coding exons of the neighboring open reading frame LOC100361087 (C1orf226 in humans and Gm7694 in mice) that was most highly expressed in olfactory bulb tissue26,27,29. This alternative transcript encodes a distinct C-terminal domain lacking the PDZ-BD that mediates NOS1 interactions26,27,28,29. The human and murine NOS1AP/Nos1ap orthologs are, similarly, in a common synteny block with C1orf226/Gm7694 (Fig. S1) and encode multiple independent transcripts with varying tissue-specific expression (Figs. S2 and S3). It is intriguing that deletion of Nos1ap in mouse cardiac tissue resulted in downregulation of Gm7694 transcripts34, suggesting co-regulation of these neighboring loci in mice. However, it remains unclear if contiguous intergenic NOS1AP-C1orf226 transcripts are expressed in these species and if the intergenic isoform plays a role in kidney physiology and disease.

In the current study, we aimed to further delineate the role of NOS1AP in podocyte disorders by (i) dissecting the biologically relevant Nos1ap isoforms using transcriptional, protein, and genetic studies, (ii) faithfully modeling NOS1AP-associated podocytopathies using multiple mouse alleles and backgrounds, and (iii) validating treatments of this podocytopathy. We first characterized an intergenic splice isoform of NOS1AP/Nos1ap and neighboring locus C1orf226/Gm7694 by multiple transcriptional and protein approaches in cells and kidney tissue from humans and rodents. The intergenic form predominates over the canonical transcript in adult kidney tissue. We next hypothesized that additional variants in NOS1AP/Nos1ap cause NS and expand the genotype-phenotype relationship between this locus and kidney disease. Gm7694−/− mice, predicted to exclusively disrupt the intergenic NOS1AP splice product, developed a podocytopathy. These findings were mirrored in Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mice with an early out-of-frame deletion and consistent with our published Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- in-frame deletion mouse model. Supporting the role of the NOS1AP C-terminus in humans, we identified two additional recessive variants in NOS1AP, predicted to impair splicing of the penultimate coding exon and the intergenic product, in two cases of pediatric-onset NS. Collectively, this suggests that variants, which impact more C-terminal regions and splice isoforms of NOS1AP/Nos1ap, lead to kidney disease. To evaluate the impact of genetic modifying factors, the Nos1apEx3- allele was bred from a C57BL/6 background onto the FVB/N background. FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice exhibited 10-fold higher albuminuria than C57BL/6-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice and developed kidney dysfunction, supporting the relevance of genetic background for Nos1ap-variant associated disease. Finally, FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice were treated with Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone-System (RAAS) inhibitor lisinopril, which reduced albuminuria and prevented premature death. Overall, our findings demonstrate that variants in the intergenic NOS1AP-C1orf226 locus cause a podocytopathy responsive to pharmacologic treatment.

Results

Intergenic splice products of NOS1AP/Nos1ap are predominant in human and mouse kidneys

We previously described an intergenic splice product of the rat ortholog Nos1ap across multiple tissues, with the highest levels in olfactory bulb tissue and low expression in brain cortex and hippocampus26,27,29. This alternative transcript encodes a distinct C-terminal domain lacking the PDZ-BD that mediates experimentally confirmed NOS1 interactions26,27,28,29 (Fig. 1A; S2 and S4). We, here, sought to further study this splice isoform in mammalian kidneys, as (i) its product may mediate distinct protein interaction partners and biological roles than the canonical protein, and (ii) interpretation of genetic variants in individuals could be dramatically altered in light of tissue-specific isoforms. In mouse and human tissues, we used (a) qualitative targeted RT-PCR and long-read RNA-sequencing data to assess the existence of contiguous intergenic NOS1AP/Nos1ap isoforms, (b) quantitative RT-PCR to compare expression of canonical and intergenic isoforms between tissues, and (c) bulk RNA-sequencing data to compare the expression of canonical and intergenic isoforms within tissues.

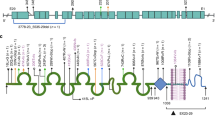

A Cartoon depicting the syntenic NOS1AP/Nos1ap genomic locus in humans and mice is shown (left). Exons are indicated that contribute to the canonical and a non-canonical (intergenic) transcript. The latter results from intergenic splicing that joins 153 nucleotides from exon 10 of NOS1AP/Nos1ap to coding exons 1 and 2 of C1orf226/Gm7694 (NM_001085375/NM_001198955). Some annotated transcripts include a non-coding exon, which is here labeled as “1*”. Arches symbolize splicing events in the Sashimi plot style. The intergenic splice junction is highlighted by a red line. mRNA transcription and processing yield two classes of transcripts (canonical and intergenic) seen in the middle, which are then translated to produce two classes of proteins (right). Both canonical and intergenic proteins contain the phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domain, while only the canonical protein bears the NOS1 enzyme-binding PDZ domain (PDZ-BD). Exons/protein regions coded in blue arise from the canonical NOS1AP/Nos1ap locus, while those in green are generated from the C1orf226/Gm7694 locus. See Fig. S2 for further details of the repertoire of transcripts and protein products. B Cartoon depicting the murine Nos1ap intergenic splice product is shown. Exons are indicated that arise from the canonical Nos1ap (blue) or adjacent Gm7694 (green) loci. The non-canonical transcript results from intergenic splicing that joins the first 153 nucleotides from exon 10 of Nos1ap to coding exons 1 and 2 of Gm7694. An amplicon spanning from early Nos1ap into coding exon 2 of Gm7694 was identified by RT-PCR in adult C57BL/6 J mouse kidney total RNA. Aligned Sanger sequencing reads are shown below the transcript diagram. C Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the PCR amplicon in (B) was aligned to the intergenic splice transcript, demonstrating a contiguous transcript with the expected in-frame continuation from Nos1ap exon 10 to Gm7694 coding exon 1 ( = exon 11 of the intergenic transcript). The dashed gray box shows the nucleotides contributing to the UTR of the non-intergenic Gm7694 transcript NM_001198955. D Quantitative RT-PCR was performed from cerebrum and kidney total RNA of 5 individual adult C57BL/6J mice. Consistent with human and rat studies, relative levels of Nos1ap early exons reflecting both long canonical and intergenic transcripts (normalized to Actb) were expressed at higher levels in brain compared to kidney tissue (median 2.4-fold, p = 0.0079). Relative levels of canonical-specific exons (Nos1ap exon 9 to late canonical exon 10) were expressed at even higher levels in brain relative to kidney tissue (median 32.3-fold, p = 0.0079). In contrast, relative levels of intergenic-specific exons (Nos1ap exon 9 to Gm7694 coding exon 1) were increased in the kidney relative to brain levels (median 9.3-fold, p = 0.0079). Bar represents median values. Mann–Whitney test performed (**p < 0.01). E Bulk short-read RNA-sequencing data from four 8-week-old mice (NCBI GEO dataset GSE145053, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE145053) were evaluated to quantify reads spanning the intergenic splice junction (GRCm38/mm10 chr1:170,318,737-170,318,738; representing canonical transcript) versus those split between exon 10 of Nos1ap and coding exon 1 of Gm7694 (GRCm38/mm10 chr1:170,302,842; representing intergenic transcript). The percentage of canonical and intergenic reads (total of 66 reads from four mice) is shown using a 5 bp sliding window approach and demonstrates that reads reflecting the intergenic transcript predominate (94.5%). F Cartoon is shown depicting the human NOS1AP intergenic splice product. Exons are indicated that arise from the canonical NOS1AP (blue) or adjacent C1orf226 (green) loci. The non-canonical transcript results from intergenic splicing that joins the first 153 nucleotides from exon 10 of NOS1AP to coding exons 1 and 2 of C1orf226 (NM_001085375). The lower image shows aligned Sanger sequencing reads spanning nearly the full-size amplicon (1943 bp), which was identified by RT-PCR from adult human kidney tissue. This product starts within the 5’ UTR of NOS1AP and ends close to the stop codon within coding exon 2 of C1orf226. G Sanger sequencing plot resulting from the 1943 bp amplicon in (F) is shown, demonstrating a contiguous transcript with the expected in-frame continuation from NOS1AP exon 10 to C1orf226 coding exon 1 ( = exon 11 of the intergenic transcript). The dashed gray box shows the nucleotides contributing to the UTR of the non-intergenic C1orf226 transcript NM_001085375. H Histogram displays percentage of NOS1AP transcripts reflecting canonical versus intergenic splice products by tissue in ENCODE long-read RNA-sequencing data. The total number of issue samples (t) and reads (r) is noted above each bar. I Violin plot displays percentage of NOS1AP transcripts reflecting canonical versus intergenic splice products from short-read RNA-sequencing data of glomerular samples from the NEPTUNE cohort. Red bar representing median values. Only samples with >5 reads at the intergenic splice junction in NOS1AP exon 10 were included. J Bulk short-read RNA-sequencing data from human fetal kidney (ENCODE) were evaluated to quantify reads spanning the intergenic splice junction versus those split between exon 10 of NOS1AP and coding exon 1 of C1orf226. The percentage of canonical and intergenic reads (r) was assessed, demonstrating that reads reflecting the intergenic transcript predominate in a fetal kidney from 20- and 24-weeks of gestation.

First, by qualitative RT-PCR of total RNA from 8-week-old mouse C57BL/6 kidneys, both contiguous canonical (blue only) and intergenic Nos1ap transcripts (blue and green) were detected (Fig. 1B, C; S5A–D). The intergenic splice product arises from joining 153 nucleotides from exon 10 of Nos1ap to the two coding exons of predicted gene Gm7694 (Fig. 1A–C; S2–4).

To quantify the relative abundance of these isoforms by qPCR, three different Nos1ap amplicons were evaluated: 1. Nos1ap exon 2 to 5 present in both canonical and intergenic isoforms; 2. Nos1ap exon 9 to late exon 10 present in canonical isoforms only; 3. Nos1ap exon 9 to Gm7694 coding exon 1 (“exon 11” of the intergenic transcript) exclusively represents intergenic isoforms (Fig. S5E). Consistent with studies in human and rat tissue26,27,29 (Fig. S3), expression levels of all Nos1ap isoforms (exon 2–5) were relatively higher in brain compared to kidney tissue (median 2.4-fold) (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, this expression level difference was more pronounced for canonical transcripts (exon 9-10) in brain compared to kidney tissue (median 32.3-fold) (Fig. 1D). In contrast, evaluation of the intergenic isoforms (exon 9–11) showed higher levels in kidney compared to brain tissue (median 9.3-fold) (Fig. 1D). Of note, qPCR studies in kidney tissue from neonates, adult 2-month-old mice, and aged 11–12 month old mice did not detect any significant changes in canonical or intergenic transcript levels across age (Fig. S5E, F).

Next, bulk RNA-sequencing data from four adult 8-week-old C57BL/6 mouse kidney was interrogated (Data S1). Sashimi plots were generated to visualize Nos1ap splice junctions and demonstrate intergenic splicing between Nos1ap exon 10 and the first coding exon of Gm7694 (Fig. S6). The intergenic splice junction in Nos1ap exon 10 was further evaluated to determine the ratio of intergenic to canonical reads by their alignment to the canonical or intergenic transcript within a 5 bp sliding window around the splice junction (GRCm38/mm10 chr1:170,318,737-170,318,738) (S7A–C). Intergenic reads were more prevalent relative to canonical reads across the four pooled datasets (94.5%) (Fig. 1E), suggesting intergenic isoforms predominate in adult mouse kidney.

In an independent dataset from neonatal to aged C57BL/6 mouse kidneys (Data S1), sashimi plots of the pooled data, similarly, demonstrated intergenic splicing (Fig. S6) although low read-depth limited quantitative analyses from this dataset (Fig. S7D).

We next evaluated intergenic splicing in the human NOS1AP locus. Qualitative RT-PCR studies, similarly, observed contiguous intergenic transcripts at the identical orthogonal splice junction (GRCh37 chr1:162336994-162336995) in adult human kidney tissue (Fig. 1F, G). This splicing, again, links the first 153 nucleotides of NOS1AP exon 10 to the first coding exon of C1orf226 (NM_001085375) (Fig. 1G; S2, S3). This observation was confirmed in human brain and kidney cell lines (SH-SY5Y, immortalized podocytes, HEK cells) (Fig. S8B–F). As a side note, inclusion of an additional 15 nucleotides in NOS1AP exon 4 (encoding LLLLQ), which we previously found in rat adult brain29, was detected in RT-PCR products from human cell lines but not a human kidney tissue sample (Fig. S8A, S8F).

To examine contiguous NOS1AP transcripts in adult kidney or other tissues (age of acquisition 40 to >90 years), long-read sequencing from the ENCODE project was interrogated and demonstrated contiguous intergenic transcripts in adult heart (n = 11), brain (n = 9), colon (n = 2) and kidney (n = 1) specimens (Fig. 1H; S9, Data S2) to varying degrees relative to contiguous canonical transcripts. For example, the canonical NOS1AP transcript predominated across brain tissues (96%), while the ratio of canonical to intergenic transcript was more variable in heart tissues (48.4%) (Fig. 1H; S9).

As low read count in the single kidney sample from long-read ENCODE data only allowed for a qualitative analysis, we next performed a quantitative evaluation of short-read RNA-sequencing data from (i) human kidney samples in the NEPTUNE cohort (living donor biopsy, nephrectomy, and NS patient biopsy) covering 244 samples of individuals from 2 to >90 years (ii) human fetal kidney samples from ENCODE (20- and 24-weeks of gestation). Sashimi plots of the NOS1AP locus generated from these datasets qualitatively confirmed the presence of intergenic splicing between NOS1AP exon 10 and the first coding exon of C1orf226 (NM_001085375) (Fig. S10A, B and S11). Quantifying reads that crossed the human splice junction, we found that qualifying reads corresponding to the intergenic splice product predominated relative to canonical reads (69.6–93.8%) in all sample groups within RNA isolated from either glomerular or tubular compartments of pediatric and adult human kidney samples (Fig. 1I, S10C–E). Similarly, the intergenic transcript predominated over the canonical in fetal kidney samples (86.20–90%) (Fig. 1J; S11).

Overall, the findings indicated that intergenic NOS1AP/Nos1ap transcripts predominate over canonical isoforms in human and mouse kidney.

Proteins corresponding to intergenic splice products of NOS1AP/Nos1ap were identified in cells and kidney tissue from humans and rodents

We next assessed whether the detected transcripts are successfully translated into detectable protein products. For this, we used immunoprecipitation (IP), immunoblotting, immunofluorescence staining, and proteomics in immortalized cell lines, primary cells, tissues from humans and rodents.

While immunoblotting for NOS1AP in mouse brain tissue lysates has been previously successful34, we have found that immunoblotting with multiple commercially available antibodies could not successfully detect NOS1AP isoforms in kidney cell and tissue lysates. We, therefore, generated multiple custom antibodies against rat NOS1AP (Fig. 2A). As these also did not sensitively detect Nos1ap isoforms in non-neuronal cells and tissues from humans and mice by immunoblotting, we used these antibodies to perform immunoprecipitation (IP) of Nos1ap. We first interrogated lysates of primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from wild-type and transgenic Nos1ap mouse models to identify select isoforms. Performing the IP and immunoblotting of the eluate with an antibody that detects C-terminal regions of both canonical and intergenic Nos1ap isoforms (“2093”), two prominent protein bands were detected in the wildtype (WT) eluate. The upper 95–100 kDa species was consistent with the intergenic isoform (I), and a lower 65–70 kDa species was at the expected size of the canonical isoform (Fig. 2B; S12A). In eluates from homozygous Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- MEFs, whose allele is predicted to cause early truncation of all Nos1ap isoforms (Fig. S14), both protein bands were absent as expected (Fig. 2B; S12A). In contrast, in the homozygous Gm7694−/− MEF eluates, whose allele would selectively lead to loss of intergenic isoforms (Fig. S14), only the upper intergenic band (I) was absent, supporting this band is comprised of the intergenic isoform. The lower band (C + L) persisted, suggesting this residual band contains only canonical protein in these Gm7694−/− knockout eluates and canonical protein must contribute to the lower band in wildtype MEF eluates (Fig. 2B; S12A).

A Cartoon is shown depicting a schematic overview of the canonical and intergenic Nos1ap proteins (left and right). Both contain the phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domain, while only the canonical protein contains a NOS1 binding PDZ domain (PDZ, reflecting the last 13 amino acids of the canonical NOS1AP protein). To help with the interpretation of the immunoblots (B–G), approximate positions of immunogens (mapped against murine proteins) against which custom and commercial antibodies were raised are shown and differentially color coded, with lighter colors for R300 and 2093 representing regions not binding. Cartoon created with BioRender.com. B Immunoprecipitation (IP) using a rabbit polyclonal antibody (“2093”) raised against Nos1ap was performed in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) isolated from wild-type and homozygous Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- and Gm7694−/− mice. Immunoblotting performed on IP eluates using the same antibody showed multiple protein bands representing Nos1ap isoforms in the wild-type eluate. The upper 95–100 kDa species, consistent with the intergenic isoform (I), was absent in eluates from Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- and Gm7694−/− MEF lines. A 65–70 kDa species, at the expected size of the canonical isoform (C + L), was absent from the Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- MEF eluates but still present in Gm7694−/− MEF eluates. The IgG Heavy Chain band (h) was detected in all eluates. Pre-immune eluate from WT MEFs is shown as a negative control (P.I.). C IP was performed as in (B). Immunoblotting was performed on IP eluates using an antibody specific to the intergenic Nos1ap isoform (“GST Long”). This showed multiple protein bands, including a 95–100 kDa band, consistent with the full-length intergenic isoform (I), and a lower species (L) at ~65–70 kDa in eluates from multiple wildtype MEF lines. These species were absent in eluates from two independent Gm7694−/− MEFs lines. The IgG Heavy Chain band (h) was also present in all eluates. Pre-immune eluate from WT MEFs is shown as a negative control (P.I.). D IP performed using GST Long antibody specific to the intergenic isoform in MEFs isolated from wildtype and homozygous Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- and Gm7694−/− mice as well as human embryonic kidney cells (HEKs). Immunoblotting was performed on IP eluates using the same antibody. This showed multiple protein bands, including a 95–100 kDa band consistent with the full-length intergenic isoform (I) and a lower species (L) at ~65–70 kDa in an eluate from a wild-type MEF line. These species were absent in eluates from Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- and Gm7694−/− MEF lines. A 95–100 kDa band consistent with the full-length intergenic isoform (I) was present in HEK cell eluates as well. The IgG Heavy Chain band (h) was also present in all eluates. Pre-immune eluates are shown as negative controls (P.I.). E Western blotting was performed on clarified lysates from MEFs isolated from wild-type, Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- and Gm7694−/− mice as well as HEK cells using an antibody specific to the intergenic isoform (“Proteintech”). This showed a 95–100 kDa band consistent with the full-length intergenic isoform (I) in wildtype MEF lysate that was absent in eluates from homozygous Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- and Gm7694−/− MEF lysates. A 95–100 kDa band consistent with the full-length intergenic isoform (I) was present in HEK lysate. Tubulin staining is shown as a loading control. F Immunoprecipitation (IP) using a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against Nos1ap (“R300”) was performed in neonatal mouse kidney lysates from heterozygous and homozygous Nos1apEx4- mice. Nos1ap immunoblotting was performed on IP eluates and showed multiple protein bands consistent with Nos1ap isoforms that were absent in mutant kidney IP eluates, including a 95–100 kDa species, consistent with the intergenic isoform (I), and a lower 65–70 kDa species (C + L). The IgG Heavy Chain band (h) was present in all eluates. G Immunoprecipitation (IP) using the intergenic isoform-specific GST Long antibody was performed in neonatal mouse kidney lysates from wild-type as well as heterozygous and homozygous Gm7694- mice. NoS1ap immunoblotting was performed on IP eluates and showed multiple protein bands, including a 95–100 kDa band, consistent with the full-length intergenic isoform (I), and a lower species (L) at ~65–70 kDa. The IgG Heavy Chain band (h) was also present in all eluates. H Indirect immunofluorescence staining of rat kidney sections was performed with intergenic-specific GST Long antibody (red) and podocyte slit diaphragm marker nephrin (green). Confocal microscopy imaging demonstrated partial co-localization of the intergenic Nos1ap isoform with slit diaphragm marker nephrin in podocytes. (Scale bars: 50 μm; 10 μm for inset.) Cartoon created with BioRender.com. I Peptide mapping from proteomics data of human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells, newborn mouse kidney, adult mouse kidney glomeruli, and adult mouse brain was analyzed with an amended list for sequences of the canonical and intergenic Nos1ap isoforms. Schematic overview showing rectangles representing either NOS1AP/Nos1ap or C1orf226/Gm7694 protein sequences (row 1), sequence unique to canonical Nos1ap (row 2, black rectangle), sequence of non-canonical intergenic product (row 3), mapping of the identified peptides in each dataset (rows 4–7). J Heatmap comparing mean intensity scores for Nos1ap and Gm7694-associated peptides as well as multiple glomerular marker proteins from adult mouse kidney dataset (row 4 in I) subdivided by glomerular cell type (podocyte or other). Heatmap based on z-scores. Nephrin, podocin, synaptopodin, and WT1, podocytic markers; Pecam1, endothelial cell marker; Alpha smooth muscle antigen, mesangial cell marker.

Next, the IP in MEFs was performed with 2093, but immunoblotting was conducted with an antibody specific to the intergenic isoforms (“GST Long”) (Fig. 2A). We observed a prominent upper 95–100 kDa band, consistent with the intergenic isoform (I), and a 65–70 kDa lower band (L) in WT MEF eluates while both were absent in Gm7694−/− MEF eluates (Fig. 2C; S12B). This supports that the upper 95–100 kDa species reflects the full-length intergenic isoform, while the lower 65–70 kDa species in MEFs is more complex and contains both the canonical isoform and, additionally, a protein of similar molecular weight derived from the intergenic locus.

Subsequently, the IP and immunoblotting were performed in MEFs with GST Long (Fig. 2D), again revealing a strong 95–100 kDa band in WT MEF and a lower band at 65–70 kDa in WT MEFs. Both were absent in Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- and Gm7694−/− MEF eluates (Fig. 2D). These observations were confirmed by performing the IP and immunoblotting with another antibody specific to intergenic Nos1ap (“PPIT”) (Fig. S12C). These findings, similarly, support that the upper 95–100 kDa species is consistent with the full-length intergenic isoform and that protein derived from the intergenic locus also contributes to the 65–70 kDa species. This lower species was previously observed in rat lysates as well and is similar in molecular weight to the canonical isoform29. We interpret this lower band to potentially represent either protein generated from an additional alternative intergenic splice product (e.g., lacking exons prior to or after exon 4) or a cleavage product of the full-length intergenic isoform (e.g., with cleavage occurring before the region encoded by exon 4).

We next employed these IP approaches in other kidney cell lines. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with the pan-NOS1AP antibody (2093) detected the 95–100 kDa intergenic band and the 65–70 kDa band in lysates from both human embryonic kidney (HEK293T) and human immortalized podocyte (HsPd) cell lines (Fig. S12D). Immunoprecipitation with the same pan-NOS1AP antibody and immunoblotting with a NOS1AP intergenic-specific antibody (GSTLong) consistently identified the 95–100 kDa intergenic band in both HEK293T and HsPd cell lysates (Fig. S12E). Using only the NOS1AP intergenic-specific antibody for IP and immunoblotting revealed the same band pattern in HEK293T and HsPd cell lysates (Fig. S12F), and similar observations were made in HEK293T cell lysates using a second intergenic-specific antibody (PPIT) (Fig. S12C). Overall, this indicated that the multiple NOS1AP isoforms, including the full-length intergenic isoform, are present in human kidney cells. We, additionally, evaluated these species within MCF7 human breast cancer cells, where NOS1AP has a reported role35, and observed multiple NOS1AP isoforms as well (Fig. 12D–F).

Given the lack of sensitivity of NOS1AP-specific antibodies in western blotting, we evaluated a commercial antibody raised against C1ORF226 for use in immunoblotting. Immunoblotting alone (without prior IP) of WT MEF cell lysates showed a prominent 95–100 kDa band, consistent with the intergenic isoform, that was absent in both Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- and Gm7694−/− MEF lysates (Fig. 2E). In HEK293T, HsPd and MFC7 cell lysates, a 95–100 kDa band, consistent with the intergenic isoform, was similarly observed (Fig. 2E; S12G). Overall, these protein-level findings provided qualitative evidence of Nos1ap intergenic protein in mouse fibroblasts and multiple human kidney cell lines.

To assess kidney tissue for the existence of the intergenic protein, we, next, performed Co-IP using two different antibodies: 1) The intergenic-specific GST Long antibody and 2) R300, an antibody, that was raised against a C-terminal fragment of canonical Nos1ap isoform (~ 199 aa) which is partially present in the intergenic Nos1ap isoform (111 aa) (Fig. 2A, F, G). Using R300 for Co-IP and immunoblotting, an upper 95–100 kDa intergenic band and a lower band at 65–70 kDa were detected in heterozygous Nos1apEx4-/+ eluates but were absent in Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- eluates (Fig. 2F). The lower band may represent a combination of canonical and intergenic locus-derived protein as observed in Fig. 2B and lower band seen in Fig. 2C, D. Using GST Long for Co-IP and immunoblotting, an upper 95–100 kDa intergenic band and a lower band at 65–70 kDa were detected in WT and heterozygous Gm7694+/- eluates but not in homozygous Gm7694−/− MEF eluates (Fig. 2G). Overall, this supports that the intergenic protein and, potentially, the canonical isoform are qualitatively present in mouse kidney tissue.

To evaluate the localization of the intergenic Nos1ap isoform within kidney tissue, we next used the GST Long antibody to perform immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy imaging in rat kidney sections. Co-staining with an antibody against slit diaphragm marker protein nephrin revealed substantial co-localization within podocytes of rat kidney glomeruli (Fig. 2H).

In a last step, we sought to assess whether peptides mapping to regions specific to the different NOS1AP/Nos1ap isoforms can be identified using proteomics approaches. For this, we both re-analyzed publicly available datasets and performs additional proteomics studies using mass spectrometry. We first re-analyzed proteomics data from FACS-sorted primary adult mouse glomerular cells36. After standard trypsin digestion and mass spectrometry, 21 unique peptides specific to either Nos1ap or Gm7694 were identified (Fig. 2I row 4, 2J; Data S3). Interestingly, no peptides aligning to the unique C-terminus of canonical Nos1ap were identified, even though theoretical trypsin cleavage sites could result in at least five detectable peptides of 7 to 25 amino acids in length (Note S2). Similarly, no peptides spanning the junction from Nos1ap to Gm7694 could be detected either (Note S2). However, this was not expected as the only predicted digestion product, including the Nos1ap-Gm7694 junction site, has a peptide length of 54 amino acids and would thus be precluded from detection by the employed mass spectrometry method (Note S2). Since proteomics for adult mouse kidney glomeruli was conducted after separation of podocytes from other glomerular cells, we could further perform semi-quantitative comparison of protein abundance for Nos1ap, Gm7694, and other glomerular marker proteins. In three independent mouse samples, Nos1ap and Gm7694 were predominantly detected in podocytes, similar to podocytic markers nephrin, podocin, synaptopodin, and WT1 (Fig. 2J).In contrast to mouse kidney glomeruli, proteomics data from adult mouse brain revealed peptides mapping throughout canonical Nos1ap but not Gm7694 (Fig. 2I row 5; Data S4)37.

To complete these studies in adult mouse tissue, we performed liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and analysis for proteome and phosphoproteome in the kidneys of newborn mice (n = 5). This analysis essentially confirmed findings from adult mouse glomeruli with 16 peptides mapped to the region of Nos1ap common to both isoforms, 5 peptides mapped to Gm7694, and none mapped to the canonical-specific region in Nos1ap (Fig. 2I row 6).

Finally, we re-analyzed proteomics data from HEK293 cells with exceptionally high coverage of protein species. This analysis revealed peptides mapping to both NOS1AP prior to the canonical-specific region as well as to C1ORF226, and interestingly, also included a peptide spanning the intergenic transition from NOS1AP to C1ORF226. Of note, this junctional peptide resulted from a cleavage event consistent with trypsin/P specificity. This supported the existence of an intergenic protein species containing this specific peptide. In contrast, no peptides mapping to the specific C-terminal region of canonical NOS1AP were detected.

These proteomics data, in sum, provided orthogonal evidence that the intergenic isoform is present in kidney cells and tissues. Intriguingly, unlike brain tissue, no canonical isoform-specific peptides were detected in proteomic data from kidney cells or tissue, which mirrors the differential transcript expression we observed in mouse tissues (Fig. 1D).

It remained unclear if this intergenic protein was functional. In our previous study, we had shown that NOS1AP induces filopodia formation in podocytes in vitro, a function impaired by patient variants20. To determine whether the intergenic isoform has a similar effect, we expressed GFP-labeled constructs for both isoforms in immortalized human podocytes and performed live cell imaging (Fig. S13A, B). We employed automated quantification of cell circularity and convexity (quotient of total over convex cell area), as these metrics would decrease as filopodia-forming cells become less round and less convex. Interestingly, expression of both tagged isoforms caused significantly reduced circularity and convexity when compared to GFP-only expressing cells, indicating both isoforms induce filopodia (Fig. S13B, D).

Taken together, these observations indicate that the intergenic NOS1AP/Nos1ap isoform is a functional protein, which is present in kidney cells and tissues across humans and rodents, with expected localization to the podocyte.

Variants impacting the Nos1ap-Gm7694 locus cause murine podocytopathy

We previously described the kidney phenotype of Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice on a C57BL/6 background20. These mice bear a homozygous deletion of Nos1ap exon 3, causing an in-frame deletion within the N-terminal PTB domain (Fig. 2A; S14A–D). Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice developed moderate albuminuria (1-3 g albumin/g creatinine) accompanied by podocyte foot process effacement at an ultrastructural level. Here, we characterized two additional Nos1ap mouse models to (i) evaluate the biological relevance of the intergenic product and (ii) further establish the association between this locus and NS.

We first studied a mouse model affecting both canonical and intergenic transcripts. Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mice bear a homozygous out-of-frame deletion in Nos1ap exon 4, predicted to cause early truncation within the PTB domain (c.271_329del; p.91_110delfs*7) (Fig. 3A; S14A–D), thereby preventing successful translation of both canonical and intergenic Nos1ap isoforms (Fig. 2B, D–F; S12).

A Nos1apEx4- allele causes a frameshift and subsequent early termination, leading to the absence of both canonical and intergenic proteins in homozygous Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mice, as shown in studies in Fig. 2. B Urine samples serially collected from 4-12-month-old C57BL/6 Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mice (n = 5) show ACR levels that are significantly elevated relative to control mice (n = 7). Graph shows dot plots with median bars for each genotype and time point. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test performed to compare groups at each timepoint (**p = 0.005051, *p = 0.035714, nsp = 0.609524). C Urine samples from 10–12-month-old Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mice and wildtype controls were interrogated by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mice exhibited marked albuminuria (69 kDa protein band) above physiological levels observed in wildtype mice. D Densitometry of albumin bands in (C) was performed, and band volume was normalized to urine creatinine. Normalized albumin abundance was significantly increased in 10–12-month-old Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mouse urine samples (n = 4) relative to control mouse urine (n = 3). The graph shows dot plots with median bars for each genotype. Two-tailed unpaired t-test; **p = 0.0017. E Representative transmission electron microscopy images are shown for Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mice (n = 4) and control wildtype mice (n = 3). Red arrowheads point to tertiary foot processes. Scale bar 2 μm. F In TEM images from (E), semi-quantification of podocyte foot process density per µm of glomerular basal membrane (GBM) was performed, showing reduced foot process density in homozygote mice. Graph shows dot plots with median bars for each genotype. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; ****p < 0.0001. G In TEM images from (E), quantification of GMB thickness in µm was performed, showing increased GBM thickness in homozygote mice. Graph shows dot plots with median bars for each genotype. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; ****p < 0.0001. H The Gm7694- leads to a selective knockout of the intergenic Nos1ap isoform in Gm7694−/− mice, as shown in studies in Fig. 2. I Urine samples serially collected from 4–12-month-old Gm7694−/− mice (n = 10) show increased ACR levels compared to control mice urine samples (n = 12). Graph shows dot plots with median bars for each genotype and time point. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test performed to compare groups at each timepoint (**p = 0.009667, *p = 0.041958, nsp = 0.071154). J Urine samples from 10-12-month-old Gm7694−/− mice (n = 5) and wildtype controls (n = 4) were interrogated by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. Homozygotes exhibited albuminuria (69 kDa protein band) above physiologic levels observed in wild-type mice. K Densitometry of albumin bands in (J) was performed, and band volume was normalized to urine creatinine. Graph shows dot plots with median bars for each genotype. Normalized albumin abundance was significantly increased in 10–12-month-old Gm7694−/− mouse urine samples (n = 5) relative to control mouse urine (n = 4). Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; *, p = 0.0159. L Representative transmission electron microscopy images are shown for Gm7694−/− mice (n = 4) and control wildtype mice (n = 3). Red arrowheads point to tertiary foot processes. Scale bar 2 μm. M In TEM images from (L), semi-quantification of podocyte foot process density per µm of glomerular basal membrane (GBM) was performed, showing reduced foot process density in homozygote mice. Graph shows dot plots with median bars for each genotype. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; ****p < 0.0001. N In TEM images from (L), quantification of GMB thickness in µm was performed, showing increased GBM thickness in homozygote mice. Graph shows dot plots with median bars for each genotype. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; ****p < 0.0001.

Albuminuria was assessed in Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mice between 4–12 months of age. Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratios (ACR) were significantly elevated in homozygous mice relative to wildtype controls at ages 7–9 months and 10–12 months (median ACR 1227 mg/g creatinine versus 492 mg/g in controls at 10–12 months) (Fig. 3B). These differences were observed for both males and female homozygotes at 10–12 months (S15A, B). Analysis of urine samples from 10 to 12-month-old mice by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining revealed albuminuria that was significantly elevated above the basal physiologic levels observed in control mice using band densitometry and normalization to urine creatinine across all homozygotes, males and females (Fig. 3C, D; S15C–F). Kidneys from approximately 10 to 12-month-old mice were evaluated for ultrastructural changes at the glomerular filtration barrier by electron microscopy. Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mouse kidney sections exhibited reduced podocyte foot process density (median 1.36 foot processes/µm versus 2.34 in controls) and glomerular basement membrane thickening (median 335 nm versus 257 nm in controls) (Fig. 3E–G). Overall, these observations supported that this recessive variant causes a murine podocytopathy, consistent with our published observations in Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice20.

Next, we investigated an allele that exclusively affects the intergenic splice isoform but not the canonical Nos1ap transcript. Specifically, we generated Gm7694−/− mice, which bear a complete deletion of predicted gene Gm7694 (Fig. 3H; S14A–D) and prevent the successful translation of the intergenic while not affecting the canonical isoform of Nos1ap (Fig. 2C–F, G).

Albuminuria was assessed, showing significantly increased ACR levels in Gm7694−/− mice relative to controls between 4–6 months and 10–12 months (Fig. 3I) (median ACR 647 mg/g creatinine in Gm7694−/− mice versus 397 mg/g in controls at 10–12 months). These differences were observed for both male homozygotes, but not female homozygotes, at 10–12 months (S15A, B). Analysis of urine samples from 10 to 12-month-old mice by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining similarly demonstrated albuminuria, which showed modest but significantly elevated above basal levels observed in control mice by densitometry and normalization to urine creatinine across all homozygotes (Fig. 3J, K, S15A, B) as well as when separately comparing male (Fig. S15G, H) and female animals (Fig. S15I, J). Kidneys from approximately 10- to 12-month-old mice were evaluated for ultrastructural changes by electron microscopy. Similar to Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mice, Gm7694−/− mouse kidney sections exhibited reduced podocyte foot process density (median 1.47 foot processes/µm versus 2.16 in controls) and glomerular basement membrane thickening (median 300 nm versus 234 nm in controls) (Fig. 3L–N). These findings suggest that Gm7694 and the intergenic Nos1ap splice product play an important role in murine podocyte homeostasis and disease.

C-terminal recessive variants in NOS1AP are associated with human SRNS

We previously discovered that two recessive variants in NOS1AP cause very early-onset NS in humans20. These variants were predicted to impact the N-terminal PTB domain of NOS1AP (Fig. 4A–C and Table 1). To discover additional disease-causing recessive variants in NOS1AP or the adjacent C1orf226 loci in humans, exome data generated after completion of our initial study were interrogated from an additional 985 families with NS.

A Cartoon is shown depicting the NOS1AP genomic locus. Exons are indicated that contribute to the canonical and an intergenic transcript. The latter results from intergenic splicing that joins 153 nucleotides from exon 10 of NOS1AP to the two coding exons of C1orf226 (NM_001085375) (junction noted by red line). Human variants associated with nephrotic syndrome are shown as arrowheads. Shading distinguishes the previously published human variants (black) from human variants reported in this article (red). The subjects, their alleles, and phenotypes are summarized below. The specific splice positions impacted by the variants is displayed. B The mRNA transcriptional products are shown with the canonical transcript NCBI accession number. Human variants are shown as described in (A). C The resulting protein products are shown containing the PTB (phosphotyrosine binding) domain and, in the case of the canonical protein, NOS1 binding PDZ domain (PDZ-BD). Human variants are shown as described in (A). D Pedigree of family B4606 is shown. Shaded symbols indicate the affected individual has SRNS, while open symbols indicate an unaffected status. Sanger tracings for affected subject B4606_21 carry the homozygous NOS1AP variant c.1105+5 G > C, while parents and unaffected siblings are heterozygous at this position. E Panel shows results of a MIDI GENE assay in the form of agarose gel electrophoresis, depicting the results of RT-PCR performed on RNA extracted from podocytes transfected with the following constructs: pCI-empty cassette (red), pCI_NOS1AP Ex9_WT (green), and pCI_NOS1AP Ex9_c.1105+5 G > C based on the variant in family B4606 (purple). F Sanger sequencing of RT-PCR product from podocytes transfected with pCI_NOS1AP Ex9_WT is shown. This confirmed the expected splicing of wildtype NOS1AP Exon 9 between Rho Exon 3 and Rho Exon 5 of the cassette. A portion of the chromatogram is shown, depicting the boundary of NOS1AP Exon 9 and Rho Exon 5. The purple arrow indicates the position of a cryptic donor splice site, and the green arrow indicates the position of the endogenous splice site. G Sanger sequencing of RT-PCR product from podocytes transfected with pCI_NOS1AP Ex9_c.1105+5 G > C is shown. A portion of the chromatogram is shown demonstrating mRNA splicing between Exon 9 in NOS1AP at the cryptic splice junction shown in (F) and Rho Exon 5 of the cassette. This is predicted to cause a frameshift and early truncation (p.Gln357Glyfs*21). H Sanger sequencing of RT-PCR product from podocytes transfected with pCI-empty cassette is shown. A portion of the chromatogram is shown demonstrating direct splicing of Rho Exon 3 into Rho Exon 5 as a negative control.

This revealed a rare, homozygous splice site variant (NM_014697:c.1105+5 G > C) in NOS1AP in family B4606 (Table 1; Fig. 4A–D). No competing variants were detected in an additional 83 nephrotic syndrome disease genes or phenocopy genes (e.g., monogenic nephritis disease genes) (Data S5). B4606_21 is a male subject, born from a consanguineous union. He developed edema at age 3 years. Consistent with the clinical diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome, his initial laboratory evaluation revealed microscopic hematuria, nephrotic-range proteinuria (19 g protein/day), hypoalbuminemia (2.2 g/dL), reduced serum total protein levels (4 g/dL), and elevated serum triglyceride levels (9.98 mmol/L). His proteinuria was resistant to corticosteroids but partially responsive to the calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine. Sanger sequencing confirmed the variant was present homozygously in the proband and heterozygously in unaffected parents and siblings, consistent with a recessive mode of inheritance (Fig. 4D). The variant was predicted to strongly impair splicing of the penultimate exon 9 by four independent algorithms (Table 1 and Fig. 4A–C). Skipping of exon 9 is predicted to create an out-of-frame deletion and loss of NOS1AP or NOS1AP-C1orf226 C-terminal domains. Furthermore, the variant was absent from control genome databases ExAC and gnomAD (Table 1). To further assess how this variant affects splicing, we performed a midigene assay38. For this, we performed PCR amplification on genomic DNA of the subject and a healthy parent to generate amplicons containing exon 9 and adjacent intronic sequence (~ 500 bp) with the wildtype sequence or the single nucleotide variant (c.1105+5 G > C). Each amplicon was then subcloned into the pCI vector in between Rho exon 3 and 5, and the resulting constructs were then expressed in immortalized human podocytes to perform RT-PCR on extracted RNA with confirmation of product identity by Sanger sequencing. Transfection with the empty vector plasmid yielded a PCR product consistent with a transcript joining exon 3 and 5 (Fig. 4E, H), while the vector containing the wildtype NOS1AP exon 9 sequence yielded products including an additional 166 bp from exon 9 (Fig. 4E, G). Interestingly, expression of the vector containing the splice variant in family B4606 yielded a shorter than the expected band size (Fig. 4E). When interrogating exon 9 sequence, an alternative splice site (score 0.54) 40 bp upstream of annotated splice site (score 0.85) was found39 (Fig. 4F). Sanger sequencing confirmed the alternative splice junction in transcript generated by the vector containing the subject’s variant (Fig. 4G). The resulting variant is predicted to cause a frameshift and an early truncation after 21 amino acids (p.Gln357Glyfs*21). We, thus, concluded the recessive NOS1AP variant identified in family B4606 is pathogenic by ACMG criteria40 and the likely cause of SRNS in this subject (Table 1), highlighting the importance of the NOS1AP C-terminus in human podocyte homeostasis.

In addition, we analyzed all NOS1AP or C1orf226 variants in the ClinVar genomic variation database41 for deleteriousness under the hypotheses that (i) recessive variants in these loci are associated with nephrotic syndrome and (ii) variants were misclassified based on the canonical transcript alone. Focusing on non-structural variants (< 50 bp in size), we observed 67 reported variants, of which 14 variants were deemed deleterious based on rare prevalence and predicted impact on protein coding or splice effect. Of these 14 variants, we previously published two (Fig. 4A–C and Table 1)20. We were unable to obtain further clinical genetic data for three variants. 8 additional variants were found in heterozygous states. A final variant was observed in a subject (VCV001333195), where, upon request, detailed genotype and phenotype data were available. Exome sequencing had been performed, identifying a homozygous variant in NOS1AP exon 10 that was absent from the gnomAD database (Table 1). This single-nucleotide variant was predicted to cause a missense in the canonical product (NM_014697: c.1259 G > C; p.G420A) with weak in silico prediction scores and, therefore, was not deemed deleterious. However, in the context of the alternative NOS1AP-C1orf226 transcript, the variant alters the +1 position of the intergenic splice site within NOS1AP exon 10 (c.1258+1 G > C). Multiple prediction scores strongly indicate impaired splicing and thus deleteriousness. Of note, no competing variants were detected, including in >71 genes associated with Mendelian genetic nephrotic syndrome and/or nephritis7. Interestingly, reverse phenotyping of the subject revealed the most severe NS phenotype, congenital nephrotic syndrome, which had progressed to end-stage kidney disease at age 3 years, requiring dialysis. The subject had passed away at the age of 5 years. He also had a unilateral cystic kidney and a healthy appearing contralateral kidney—anomalies that are unlikely to be sufficient for his early-onset kidney failure. Collectively, this data supports that this essential splice site variant is pathogenic by ACMG criteria (Table 1), supporting that intergenic splicing of NOS1AP and C1orf226 is critical in human podocyte homeostasis and corroborates our findings in mouse model studies (Fig. 3).

Recessive Nos1ap variants cause severe albuminuria and kidney dysfunction on FVB/N genetic background

Our current and published data established that bi-allelic variants in the NOS1AP-C1orf226 locus, affecting N-terminal or C-terminal regions of the encoded protein, cause a severe podocytopathy in humans (Table 1 and Fig. 4). In contrast, Nos1ap-deficient mice exhibited a more moderate phenotype. Specifically, we previously showed that Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice on a C57BL/6 background developed albuminuria and ultrastructural changes in the glomerular filtration barrier, but not persistent hypoalbuminemia, kidney dysfunction, or reduced survival20—features frequently observed in human SRNS. The additional mouse models described here (Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- and Gm7694−/− mice) similarly had modest albuminuria and normal survival into late adulthood on a C57BL/6 background (Fig. 3). This suggested that additional loci may modify the phenotype caused by Nos1ap deficiency.

Because genetic background can modify the severity of murine podocytopathies42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51, we posited that the kidney phenotype in C57BL/6-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- could be similarly altered by genetic background to enable more faithful modeling of human SRNS and the establishment of an optimal model for evaluating potential therapies. Therefore, C57BL/6-Nos1apEx3-/+ mice were bred with FVB/N or 129/sv mice for more than six generations. This would yield Nos1apEx3-/+ mice with a genetic background reflecting >98% of the outcrossed strain (Fig. 5A). Of note, transcriptional levels of all long and intergenic Nos1ap isoforms were not significantly different in adult kidney samples across C57BL/6, FVB/N, and 129/sv adult mice, while the canonical Nos1ap isoforms was significantly higher expressed in C57BL/6 compared to FVB/N mice (3-fold) (Fig. S5G). Resulting FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/+ or 129/sv-Nos1apEx3-/+ were in-crossed to yield wildtype, heterozygote, and homozygote mice of the same background.

A Diagram depicting the breeding of the Nos1apEx3- allele from the C57BL/6 background to FVB/N or 129/sv backgrounds in order to determine if this modifies the podocytopathy phenotype. Cartoon created with BioRender.com. B Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice on an FVB/N background show significantly elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratios (ACR) beginning at weanling age and increasing through 4–5 months of age compared to control animals. Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- group consists of 9 male and 7 female mice. Control mice consisted of 11 Nos1apEx3-/+ heterozygous mice (6 male, 5 female) as well as 3 wildtype littermates (1 male, 2 female). Graph shows dot plots with mean bars for each genotype and time point. Red, homozygous animals; Black, wild type and heterozygous littermate controls. Mann–Whitney test performed to compare groups at each timepoint (*p < 0.05; from ages 1–6: p = 0.00002, p < 0.000001, p < 0.000001, p < 0.000001, p < 0.000001, p = 0.000006). C Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- on an FVB/N background (n = 14 mice) show ACR levels that are one order of magnitude above ACR levels detected in the originally studied C57BL/6 (p = 10 mice) as well as 129/sv background (n = 3 mice). Graph shows dot plots with mean bars for each genotype and time point. Red triangles, FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3-; Black dots, C57BL/6-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3-; Blue diamonds, 129/sv-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3-. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test performed to compare groups at each timepoint (*p < 0.05; 3–4 months: p = 0.000002, p = 0.002941; 5–6 months: p = 0.000011, p = 0.10989). D Serum albumin levels were quantified using the VetScan VS2 system and “Comprehensive Diagnostic Profile” rotors. Graph shows dot plots with median bars for each genotype. Homozygous animals (n = 17 mice) showed significantly reduced levels of serum albumin relative to control mice (n = 9 mice). Red triangles, homozygous animals; Black dots, wild type and heterozygous littermate controls; mo, months. Mann–Whitney test performed to compare groups at each timepoint (****p = 0.000011, ***p = 0.000123, **p = 0.001166, *p = 0.046465). E Serum BUN levels were quantified in homozygotes (red) or littermate controls (green) from 3–6 months of life. Graph shows dot plots with median bars for each genotype. A subset of homozygotes (17/29 measurements) showed elevated BUN levels above 30 mg/dL at 3–6 months of life, while no control samples did (0/21 measurements). (****p < 0.0001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05; from 3–6 months: p = 0.046465, p = 0.004079, p = 0.022798, p = 0.000054). F Animal numbers were assessed of FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice and littermate controls (WT, Nos1apEx3-/+), which underwent minimal interventions, at 1 month of life at the time of weaning and at 6–8 months of life. Homozygotes showed increased mortality between 6–8 months of life that was not observed in littermate controls.

We previously established that the Nos1apEx3- variant causes an in-frame deletion at the transcriptional level, but wanted to confirm this occurs at the protein level using newer reagents not previously available at the time of our initial study. For immunoblotting, we used the pan-NOS1AP 2093 antibody and SDS-PAGE on a high percentage (15% Bis-Tris) gel to assess neonatal brain lysates from wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous Nos1apEx3- mice, as has been described in global Nos1ap knockout mice34. In WT and heterozygous animals, a ~ 60–65 kDa band was detected, which was absent in homozygotes, and consistent with the wildtype protein. A lower band at ~55-60 kDa was detected in heterozygous and homozygous animals, which was absent in WT animals (Fig. S16A). This likely indicates that a stable, shorter Nos1ap protein is produced by the in-frame deletion Nos1apEx3- allele.

FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice developed albuminuria at weaning age with a median ACR of 1.9 g/g, which increased to 13.8-15.7 g/g at 4–6 months of life (Fig. 5B) and consistently for both male and female animals (Fig. S17A, B). In contrast, ACR levels in 129/sv-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice were more modestly elevated relative to wildtype or heterozygote littermate controls (1–3 g/g during the first six months of life) (Fig. 5C; S16B). Overall, FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice exhibited markedly elevated albuminuria relative to 129/sv-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- and C57BL/6-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice between 3–6 months of life (Fig. 5C), indicating the FVB/N background uniquely modifies this kidney phenotype.

FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice were further analyzed for serum markers of nephrotic syndrome. In association with marked albuminuria, male and female FVB/N homozygous mice developed significantly reduced serum albumin levels in serial measurements at 3–6 months of life relative to littermate controls (median albumin levels 3.0–3.5 g/dL versus 3.7-4.1 g/dL) (Fig. 5D; S17C). Serum BUN levels, a marker of declining kidney function, at 3–6 months were significantly elevated in FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice relative to littermate controls (median BUN levels 30-37 mg/dL versus 20-25 mg/dL), more frequently in males than females (Fig. 5E; S16C and S17D). Serum creatinine was not significantly changed (Fig. S16D), but it is not a sensitive marker of renal function in mice52. In correlation with reduced kidney function, homozygotes also exhibited reduced survival between 6–8 months of life relative to control mice (Fig. 5F). Thus, in contrast to C57BL/6-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice20, FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice develop persistent hypoalbuminemia, kidney dysfunction, and increased mortality, faithfully recapitulating features of human SRNS.

FVB/N-Nos1ap Ex3-/Ex3- mice exhibit histologic and ultrastructural features of a severe podocytopathy

Given the urinary and serum abnormalities in FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice, we hypothesized that homozygous mice develop glomerular changes consistent with a podocytopathy. Kidney tissue sections from 6–8 months old mice were Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) stained and analyzed by light microscopy. Measurement of PAS-positive matrix within glomerular tufts revealed significantly increased mesangial matrix deposition, indicative of chronic glomerular injury, in FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice relative to heterozygote controls (Fig. 6A). Kidney tissue sections from FVB/N homozygotes, furthermore, showed tubular dilation, reminiscent of human congenital nephrotic syndrome53, in contrast to heterozygote controls (Fig. 6B).

A Periodic acid-Schiff-stained sections of kidneys from 6-month-old Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- and Nos1apEx3-/+ mice were generated. 40x images of glomeruli were evaluated through an automated ImageJ pipeline to determine glomerular matrix deposition in a blinded manner. Both male and female Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice showed significantly increased glomerular matrix deposition. 6 control and 7 Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice per sex group were analyzed (glomeruli count from left to right: 151, 177, 153, 177). Graph shows dot plots with median bars for each genotype. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; ***p < 0.0001; Red triangles, Nos1apEx3-/Ex3-; Black dots, Nos1apEx3-/+ littermate controls; Scale bar μm. B Kidneys were processed at in (A). Representative overview images (stitched from 2X fields) and inset images (20X) are shown for Nos1apEx3-/+ controls and Nos1ap Ex3-/Ex3- mice. Tubular dilation is observed in homozygous mice as quantified in the dot plot (right). Red triangle, n = 12 Nos1apEx3-/Ex3-; Black dots, n = 14 Nos1apEx3-/+ littermate controls. Five 20X fields per mouse for quantification; Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; ***p = 0.0004. Scale bar 100 μm. C Representative transmission electron microscopy images are shown for the heterozygous control Nos1ap+/Ex3- and homozygous Nos1ap Ex3- /Ex3- mice (5 animals per genotype analyzed). Red arrowheads point to tertiary foot processes. Semi-quantification of podocyte foot process density per µm of glomerular basal membrane (GBM) and quantification of GMB thickness in nm (left and right panel, respectively). Dot plot of all data points shown for each genotype with box plot overlayed representing span of 25 to 75th percentiles, center line 50th percentile, and minima to maxima whiskers. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; ***p < 0.0001; Red triangles, Nos1apEx3-/Ex3-; Black dots, Nos1apEx3-/+ littermate controls; Scale bar 2 μm.

Kidney sections were also examined by electron microscopy at weaning age (3–4 weeks of life) to assess early ultrastructural changes when albuminuria was first detected in FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice (Fig. 5B). Homozygotes exhibited podocyte foot process effacement and thickening of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) (Fig. 6C), relative to heterozygote glomeruli exhibiting appropriate rhythmicity of foot process formation and GBM thickness. We, then, also assessed ultrastructure in weanling C57BL/6-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice, who did not yet show markedly elevated albuminuria at this early age. Interestingly, C57BL/6 homozygotes exhibited reduced foot process density, but no thickening of the GBM was observed compared to heterozygous control animals (Fig. S18).

Finally, to determine if these phenotypic differences between genetic backgrounds may be secondary to transcriptional differences in isoform expression, we assessed canonical and intergenic Nos1ap transcript levels in kidney tissue from C57BL/6-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- and FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice but found no significant differences (Fig. S5H).

Overall, FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice exhibited biochemical and structural kidney abnormalities consistent with human SRNS and modified by genetic background.

FVB/N-Nos1ap Ex3-/Ex3- mice respond to RAAS blockade

Having established a more faithful model of NOS1AP-associated podocytopathy in FVB/N- Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice, we next sought to evaluate the impact of potential therapies given the lack of effective options in SRNS. RAAS blockade is widely employed in acquired proteinuric diseases to reduce proteinuria and preserve renal function54,55,56. In children with genetic or primary SRNS/FSGS, RAAS blockade similarly reduces proteinuria57,58,59,60,61. However, it remains unclear whether this therapeutic approach can preserve GFR or promote survival in monogenic glomerular disorders outside of COL4A3/4/5-variant associated Alport syndrome62,63. This includes those caused by variants in podocyte-specific actin regulatory genes such as NOS1AP10,19,20,64,65,66,67. Therefore, we evaluated the impact of RAAS blockade in Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice using an ACE inhibitor, lisinopril.

FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice were treated at weaning age with oral lisinopril. To assess the impact on proteinuria, urine ACRs were measured every two weeks for 14 weeks of treatment (Fig. 7A). FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice treated with 100 mg/L and 200 mg/L lisinopril exhibited significantly reduced albuminuria relative to vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 7A), indicating RAAS ameliorates the proteinuric phenotype in this model.

A FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice with comparable baseline ACRs received drinking water with either vehicle (water), 100 mg/L lisinopril, or 200 mg/L lisinopril starting at 6 weeks of age. Urine was collected biweekly, and albumin as well as creatinine were quantified to determine albumin-to-creatinine ratios (ACR) as in Fig. 1. In both treatment groups (100 mg/L lisinopril or 200 mg/L lisinopril,) albuminuria progression was significantly reduced by non-parametric ANOVA Friedman test (p = 0.0035 for vehicle versus 100 mg/L, p = 0.0179 for vehicle versus 200 mg/L, p > 0.9999 for 100 mg/L v.s 200 mg/L). Dot plot shown with median values connected by line segments. Pink, Vehicle control, n = 9 (5 male, 4 female); Red, 100 mg/L lisinopril group, n = 10 (5 male, 5 female); Blue, 200 mg/L lisinopril group, n = 9 (4 male, 5 female). B FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice from (A) treated with lisinopril were followed up past urine collections for a total of 140 days of treatment. During the observed period, none of the lisinopril-treated mice died (0/11) while only 20% of untreated mice survived (4/5 died). Kaplan-Meier curves are shown. Pink dashed, vehicle control, n = 5; Red, 100 mg/L lisinopril group, n = 6; Blue, 200 mg/L lisinopril group, n = 5. Statistically significant by Mantel-Cox test (p = 0.0014).

Serum markers were measured at early (4–8 weeks of treatment) and late (12–16 weeks of treatment) time-points. Serum albumin and total protein were significantly elevated in homozygous mice treated with 100 mg/L lisinopril relative to those receiving vehicle at the early timepoint (Fig. S19A, B), correlating with the improvement in albuminuria (Fig. 7A). FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice treated with 100 mg/L also showed reduced BUN levels relative to vehicle-treated animals at the late timepoint (Fig. S19C), indicating kidney dysfunction was blunted by this ACE inhibitor dose. In contrast, FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice treated with 200 mg/L did not have significantly different serum albumin, total protein, or BUN levels than vehicle-treated mice (Fig. S19).

Survival of FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice was monitored over 140 days of treatment. While only 20% (1/5) of vehicle-treated mice survived this time frame, all (11/11) of the homozygotes treated with lisinopril survived (Fig. 7B). These results indicate that RAAS blockade using lisinopril not only reduces proteinuria but also prevents mortality in a mouse model of human SRNS caused by defective actin remodeling.

FVB/N-Nos1ap Ex3-/Ex3- mice do not respond to Dynamin Activator Bis-T-23

Dynamin stimulates actin bundling and, like NOS1AP, promotes filopodia formation20,26,68,69,70. Dynamin activating compound Bis-T-23 reduced albuminuria and normalized podocyte ultrastructural defects in multiple murine podocytopathies71. We hypothesized that Bis-T-23 would, similarly, improve proteinuria in FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice. However, we did not observe altered albuminuria with daily Bis-T-23 treatment in 4-week-old FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice, including when collecting urine 1–3 h after treatment to assess for a transient reduction in albuminuria (Fig. S20).

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to further delineate the role of the NS disease gene NOS1AP by (i) dissecting its biologically relevant isoforms using multi-omic approaches, (ii) establishing additional mouse models that strengthen the association between this locus and podocytopathies and faithfully recapitulate human disease, and (iii) validating treatment options for this podocytopathy.

In summary, we demonstrate that variants impacting the NOS1AP-C1orf226/Nos1ap-Gm7694 locus can cause podocytopathy in humans and mice (Figs. 1–4), supporting an important role for the, here described, NOS1AP intergenic splice product in kidney disease. We, furthermore, demonstrate that genetic background of Nos1ap mouse models can modify the severity of this genetic podocytopathy (Figs. 5, 6), which resulted in the generation of a more faithful model of human NS and suggests that variants in additional loci can modify the nephrotic syndrome trait in mammals. Lastly, we provide evidence that in a genetic mouse model of NOS1AP-associated podocytopathy RAAS blockade is effective in reducing proteinuria and preventing early mortality in this genetic form of nephrotic syndrome (Fig. 7).

The NOS1AP alleles in humans and mice identified in this study (Figs. 3, 4, S14; Table 1) not only expand the genotype-phenotype correlation between this locus and NS but also underscore the impact of C-terminal domains and alternative splice isoforms of NOS1AP/Nos1ap in monogenic nephrotic syndrome. We present in vitro experiments on morphological changes of podocytes caused by both isoforms, suggesting they may play similar roles in regulating the cytoskeleton. However, much more detailed analyses are warranted to determine whether canonical and intergenic isoforms of NOS1AP play redundant or independent roles in podocyte biology. Future studies will have to functionally compare both isoforms, including assessing whether the different C-termini of these isoforms engage distinct interaction partners (e.g. through comparative interactome analyses). It will also be important to contrast these interaction partners with those disrupted by N-terminal PTB domain NS variants, which we previously determined impair NOS1AP-dependent actin remodeling and podocyte homeostasis in humans and mice20.

Our previous studies indicate that NOS1AP-dependent actin remodeling in podocytes is independent of its neuronal binding partner NOS120. It remains possible that the canonical NOS1AP protein may mediate its actin remodeling effects through a key interaction partner other than NOS1. In addition, our current findings lead us to posit that NOS1AP may regulate podocyte homeostasis through interactions mediated by the altered C-terminal domain created through the intergenic splice product. In any case, the previously experimentally established NOS1 interaction domain resides within the C-terminal part of NOS1AP that is only included in the canonical but not the intergenic isoform. Future studies should, therefore, compare isoform-specific interaction partners and determine if an in-frame deletion allele, only affecting the NOS1-binding domain, causes a podocytopathy in mice.

Human subject VCV001333195 received CLIA-certified genetic testing to explain his diagnosis of congenital nephrotic syndrome. However, due to interpretation based on the canonical transcript, the identified homozygous variant in NOS1AP was misclassified as benign. This case underscores the importance of tissue- and condition-specific isoform expression for correct variant interpretation, especially as recent studies indicate that >10 alternative transcripts exist for human coding genes while only an average of 4 transcripts per gene are annotated72,73,74.

Transcriptional studies suggest predominance of an intergenic over the canonical transcript in human and mouse kidneys of different ages (Figs. 1 and 2). One limitation of our protein analyses was the lack of a sensitive antibody to detect all NOS1AP isoforms and compare their relative abundance in kidney lysates by immunoblotting. The proteomics strategies used were also technically limited in their capacity to detect junctional peptides specific to the intergenic long isoforms. However, it should be noted that qualitative proteomics studies detected canonical-specific peptides only in mouse brain tissue datasets, while intergenic-specific regions were only identified in human kidney cell and mouse kidney tissue datasets (Fig. 2I, J). It will be important in future studies to evaluate high coverage proteomics data from human glomerular samples to confirm the presence of these protein isoforms in native human tissue and, especially, those studies employing alternative protocols to standard trypsin digestion (such as chymotrypsin) to increase the likelihood of detecting peptides at the NOS1AP-C1orf226 protein junction. It also remains unclear whether potential additional short NOS1AP-C1orf226 transcripts, not distinguished by short-read RNA-sequencing data, play an important role in disease.

Genetic background is, next, established to modify the phenotype of Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice, thereby yielding a more faithful model of steroid-resistant NS observed in human subjects and platform for evaluating potential therapies (Figs. 5, 6; S16–18). In fact, the FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice develop profound albuminuria, kidney dysfunction, and histologic kidney damage reminiscent of human congenital nephrotic syndrome caused by genetic variants in NPHS153. These mice, furthermore, develop ultrastructural damage to the glomerular filtration barrier at an early time point not observed in C57BL/6 homozygotes. The increased susceptibility of the FVB/N mouse strain to glomerular injury in genetic and acquired models of glomerular disease has been previously established42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been performed but revealed distinctly associated loci depending on the kidney disease model, none including the Nos1ap locus on chromosome 142,47,48,49. It will be important, in future studies, to identify loci associated explicitly with modification of the Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- albuminuria and kidney dysfunction traits (e.g., through array-based approaches), as these genetic factors could reveal modifying factors that mitigate or aggravate the actin dysregulation caused by Nos1ap deficiency. We would also want to consider whether genetic background has a similar impact on the other murine alleles evaluated in this study.

Although this locus has not been implicated in GWAS of mouse glomerular disease phenotypes, we did consider whether genetic background in wildtype and homozygous mutant mice alters Nos1ap transcript isoform expression specifically. The only significant difference was a 3-fold lower expression of the canonical isoform in wildtype FVB/NJ mouse kidney relative to wildtype C57BL/6 J mouse kidney, while there was no difference in this isoform between wildtype 129svJ and FVB/NJ kidney tissue (Fig. S5G). It is unclear how this difference would explain the lower albuminuria observed in both C57BL/6 J and 129svJ homozygous mice relative to FVB/NJ mice (Fig. 5B). Moreover, neither canonical nor intergenic isoform expression was significantly different in FVB/NJ and C57BL/6 J Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice (Fig. S5H), suggesting that differential Nos1ap transcript isoform expression cannot explain the differential kidney traits in these mice.

Genetic background may also explain differences in the survival phenotypes of Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mice. A previous study reported that global Nos1apEx4-/Ex4- mice on a pure C57BL/6 J background exhibited lethality during fetal development34. In contrast, homozygotes in our study were bred on a mixed C57BL/6J-6N background and were viable through adulthood, consistent with reported data from the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC)75,76. This, similarly, supports that genetic background can influence Nos1ap-associated phenotypes.

Treatment options are very limited in genetic forms of NS. RAAS blockade is widely employed in acquired proteinuric diseases, providing a reduction of proteinuria and preservation of GFR54,55,56. Some case reports and a recent meta-analysis report proteinuria reduction from RAAS blockade in children with genetic or primary SRNS/FSGS57,58,59,60,61. However, strong evidence for clinical or experimental benefits in terms of preservation of renal function and reduction in mortality has not been demonstrated for any form of monogenic proteinuric disease other than COL4A3/4/5-variant associated Alport syndrome62,63. Our findings, that lisinopril ameliorates Nos1ap-associated podocytopathy in mice, suggest that this benefit extends to other Mendelian genetic pathways and should be considered in other forms caused by variants in podocyte-specific actin regulatory genes10,19,20,64,65,66,67 and assessed in a systematic manner.

On the other hand, Bis-T-23 did not alter the proteinuria in FVB/N-Nos1apEx3-/Ex3- mice despite the related roles that NOS1AP and dynamin proteins play in actin-based filopodia formation20,26,68,69,70. It should be noted that there were, in fact, only modest transient effects of Bis-T-23 on proteinuria in a mouse model of ACTN4-associated nephropathy71, indicating that enhancing Dynamin oligomerization may not be sufficient to restore normal podocyte physiology in some forms of genetic NS.

Overall, these findings (i) further establish an essential role of NOS1AP for podocyte biology and podocytopathies, (ii) provide evidence for pharmaceutical treatment options in genetic podocytopathies, and (iii) underline the importance of understanding tissue-specific isoform expression for interpreting genetic testing results.

Methods

Ethics: Study design, conduct, approval, and Human Genetics Study Subject recruitment

The study design and conduct complied with all relevant regulations regarding the use of human study participants and was conducted in accordance with the criteria set by the Declaration of Helsinki as well as the SAGER guidelines.