Abstract

Vision begins with conformational changes in photopigments. The associated electrical signature, called an early receptor potential (ERP), in rods is limited to contribution of a small fraction of rhodopsin embedded in plasma membrane. Optoretinography (ORG), using phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography, detects nanoscale deformations of retinal cells associated with physiological processes. In previous ORG studies, focused primarily on cones, deformation related to ERP was largely obscured by osmotic swelling and long stimuli. Here, we demonstrate a robust electromechanical signature of photoisomerization in rods. A green flash induces a sub-millisecond contraction of the outer segments by hundreds of nanometers, while a subsequent UV flash reverts the activated molecules, producing an opposite response of similar magnitude. ORG surpasses the sensitivity of electrical methods by integrating the response across all the discs in rod outer segments and it opens the door to fundamental studies of visual transduction in-vivo and to more specific clinical diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vision begins with the absorption of photons in photoreceptors, triggering photoisomerization of photopigments and subsequent phototransduction, ultimately hyperpolarizing the cells and modulating their neurotransmitter release1. After photon capture, rhodopsin undergoes a series of isomerization intermediates, including lumirhodopsin and metarhodopsin I (Meta I), before reaching the biochemically active metarhodopsin II (Meta II) state2,3, a process involving charge transfer across the membrane, primarily in the outer segment discs4,5,6. Patch clamp electrophysiological recordings in photoreceptors, a very invasive technique applicable only ex vivo, revealed a rapid electrical signal, called the early receptor potential (ERP)6,7,8: a brief depolarizing phase (R1) corresponding to the formation of Meta I, and a dominant hyperpolarizing phase (R2) reflecting the conversion from Meta I to Meta II8. Previous electrical recordings in living rat eyes demonstrated that a 400-nm flash delivered to photoreceptors fully bleached by green light can elicit a rapid electrical signal of opposite polarity, indicating that near-UV photons can revert the activated rhodopsin into another isoform9, subsequently shown to be Metarhodopsin III (Meta III), which can again absorb green photons10.

In vivo observation of these processes is critical for understanding the biophysics of vision in real physiological conditions and for more specific clinical diagnosis of multiple forms of photoreceptors’ dysfunction. Indeed, a reduction in ERP amplitude has been noted in electroretinography (ERG) recordings from patients with diabetic retinopathy and retinitis pigmentosa11. The ERP originates from charge transfer across the cell membrane5,6. Even though rods constitute the vast majority of photoreceptors in most mammalian retinas12, such electrical recordings from rods are more challenging than from cones due to the distinct membranous organization of their outer segments. Specifically, most of rhodopsin is embedded in the sealed disc membranes, which are isolated and electrically decoupled from the plasma membrane of the outer segment (Fig. 4A)3,13. In contrast, cone discs are direct infoldings of the plasma membrane itself14. As a result, rod signals are overshadowed by cone responses in primate and human retinas15,16.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a powerful imaging modality in biomedical optics that enables non-invasive, depth-resolved imaging with micron-level resolution17. While the amplitude component of OCT signals reveals microstructural features, phase-sensitive measurements allow motion detection with nanometer-scale sensitivity18,19. In particular, by monitoring the phase difference between two retinal layers20, phase-sensitive OCT has detected deformations in photoreceptors associated with metabolic events, such as photoisomerization and phototransduction21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. This technique, termed optoretinography (ORG), enabled the observation of a rapid (few milliseconds) contraction and slow (hundreds of milliseconds) expansion of the cone outer segments (COS) immediately following a light stimulus21,23,24. Contractile deformations were attributed to electromechanical coupling30—changes in the surface tension associated with the changes of transmembrane voltage induced by charge transfer across the membrane. In contrast, the slower expansion of COS was linked to osmotic influx of water, swelling of the cone opsin and disc membrane27,31, and conformational changes in phosphodiesterase (PDE6) during phototransduction29. Typically, the swelling in cones obscures the rapid contractile signal related to ERP, and relatively long light stimuli used in earlier ORG studies21,23,24 could not resolve the sub-ms dynamics of the rhodopsin isomerization2,3,9.

In this study, we investigated ORG signatures associated with rhodopsin dynamics in the living rat eye, where ~99% of photoreceptors are rods32, making it an ideal model for studying rod ORG signals. By employing ultrafast (10-kHz B-scan rate) OCT recordings and microsecond-scale light stimuli, we observed a sub-ms fast contraction of the rod outer segments (ROS) by hundreds of nanometers that persisted for hundreds of milliseconds. About a thousand ROS disc membranes collectively contributed to this robust electromechanical effect, surpassing the sensitivity of electrical measurements. Furthermore, a UV (385 nm) flash delivered after extensive bleaching by green (520 nm) light reversed the contraction and enabled further absorption of green photons, indicating a transition from Meta II to Meta III. This imaging method with microsecond-scale temporal resolution opens the door to fundamental studies of visual transduction in vivo and to more specific clinical diagnosis of the photoreceptors’ dysfunction, with a possibility of single-cell spatial resolution.

Results

Dynamics of the ROS contraction

To assess the dynamics of the ROS contraction, we applied green (520 nm) flashes to retinas of wild-type rats while acquiring repeated B-scans at a 10 kHz frame rate using a custom-built ultrafast line-scan OCT system. To investigate the impact of pulse duration on the waveform of the rapid contractile response (Fig. 1), we employed pulse durations of 50, 100, 200, 500 μs, and 1 ms (see Fig. S4 for temporal profiles) and adjusted the power to maintain a consistent pulse energy of −50.6 ± 0.2 μJ, measured in front of the cornea. Considering a transmittance of 0.77 through the anterior segment of the eye at 520 nm33,34 and an illumination area on the retina of 1.88 mm2, this corresponds to approximately 5.4 × 107 photons/μm2 incident on the retina. We also explored the stimulus strength dependence of the rapid contraction by fixing the pulse duration at 100 μs and adjusting the flash energy in approximately two-fold increments (Fig. 2).

A Averaged structural image of a wild-type (WT) rat retina (n = 100). The orange curve represents the intensity profile, and segments in cyan highlight two retinal bands—IS/OS and ROST—utilized for calculating the optical path length (OPL) along the rod outer segment (ROS). Scale bars: 50 μm. For a single frame, the SNR for pixels in the IS/OS and ROST is approximately 15 dB and 20 dB, respectively. IS/OS inner segment/outer segment junction, ROST rod outer segment tips, RPE retinal pigment epithelium. B ΔOPL traces extracted from ROS and averaged across 4–5 animals for each flash duration. The purple band represents the standard deviation (SD) range for the 0.2 ms pulse duration. The rapid contraction amplitude was extracted by averaging ΔOPL within the 3–4 ms temporal window after the stimulus onset. C Enlarged view of ΔOPL traces within the first 3 ms after the stimulus onset. D Time derivatives of ΔOPL traces. E Amplitude of the ROS rapid contraction. Scatter plot of all individual data points, with error bars indicating one standard deviation around the average for each pulse duration (n = 5). F Latency of the maximum contraction rate. Statistical distribution of the time points corresponding to the maximum contraction rate in various animals (n = 5) for each pulse duration, with error bars representing one standard deviation around the average. Green bars represent varying pulse durations for comparison.

A ΔOPL traces in response to 100-μs pulses with varying energies. Semitransparent band represents the standard deviation range (n = 5). B ΔOPL traces within the first 3 ms after the flash onset. C Contraction rate—the time derivative of ΔOPL traces. D Amplitude of the rapid contraction. Scatter plot of all individual data points, with error bars indicating one standard deviation around the average for each pulse energy (n = 5). E Latency of the maximum contraction rate: data points of individual animals (n = 5), with error bars representing one standard deviation around the average.

Changes in the phase difference between two retinal bands reflect variations in the optical path length (ΔOPL) between them. As illustrated in Fig. 1A, to assess the light-evoked response of the ROS, we computed the phase difference between the inner segment/outer segment (IS/OS) junction and the rod outer segment tips (ROST, the top of the thick hyperreflective band consisting of ROST and the retinal pigment epithelium28,35). The ΔOPL traces presented in Fig. 1B for each pulse duration were extracted from ROS and averaged across 4–5 rats. Since similar photon densities were delivered to the retina, the resulting rapid contraction amplitudes of the outer segments were comparable, although response to the 1-ms flash was noticeably slower and its contraction amplitude was slightly larger than those with shorter pulses. This is likely due to a more pronounced photoreversal effect of shorter pulses, resulting in fewer activated rhodopsins (see section Modeling the ROS contraction). Amplitudes of the rapid contraction were extracted by averaging ΔOPL at the first 3–4 ms temporal window after the stimulus onset, and their statistical distributions are shown in Fig. 1E.

In stark contrast to the fast recovery (<20 ms) from the rapid contraction observed in COS responses24, the ROS remained in a contracted state throughout the 400-ms acquisition window. As can be seen in Fig. 1C, the contraction process begins almost immediately after the flash onset, but continues for about 3 ms, even with the 50-μs flash. The contraction rate, shown in Fig. 1D, was calculated by taking a time derivative of each trace. Latency of the maximum contraction rate was extracted and compared to pulse durations in Fig. 1F. Interestingly, for flashes shorter than 0.5 ms, latency of the maximum contraction rate remains almost the same—about 0.45 ms, and it starts increasing for longer pulses.

While a short, intense flash revealed the impulse response of the rapid contraction process, its strength dependence provides additional insights into the underlying mechanisms. Figure 2A displays the ΔOPL traces in response to 100-μs flashes with varying energy levels. As expected, amplitude of the rapid contraction increases with incident photon density. With the lowest pulse energy, OPL significantly recovered during the 400 ms after the flash, while at higher energy levels, contraction remained steady and even slowly increased over time. Dynamics of the rapid contraction within the first 3 ms is shown in Fig. 2B. The contraction amplitudes, determined by the same procedure as in Fig. 1, are shown in Fig. 2D, revealing a saturating trend. Latency of the maximum contraction rate, shown in Fig. 2C, E, decreases with increasing pulse energy from about 0.55 ms and saturates at around 0.45 ms.

Modeling the ROS contraction

Early photoproducts, up to Meta I, can absorb a second photon and restore either rhodopsin or isorhodopsin, a process called photoreversal36,37,38. Therefore, if a large number of photons are delivered while a substantial portion of rhodopsin isoforms have not yet decayed to Meta II, photoreversal of the rhodopsin bleaching cannot be neglected. Given that the flash durations in our experiments are comparable to the thermal decay time constant from Meta I to Meta II (a few hundred microseconds in rodents5,9), we considered all critical light-driven and thermal processes involved in flash photolysis to determine the bleach levels (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Information: Bleach level calculation). The calculations showed that rapid contraction amplitude ΔOPL increased logarithmically with the estimated bleach levels (Fig. 3B).

A Rhodopsin isomerization pathways include photon-driven transitions (green arrows) and thermal decay processes (red arrows). γXY: quantum efficiency of the photoisomerization from X to Y. KXY: reaction rate of the thermal decay from X to Y. B Rapid contraction amplitude, measured in Fig. 2D (n = 5), increased logarithmically with the estimated bleach level. Colored dots represent individual measurements, error bars indicate one standard deviation around the average, and the gray line denotes the logarithmic fitting.

The rapid contraction measured in COS was previously explained using the voltage-dependent membrane tension model30. In brief, the charge shift during the R2 phase of the ERP leads to hyperpolarization of the disc membranes. Increase of charge density in the Debye layer increases the repulsion of ions39,40,41, resulting in lateral stretching of the disc membrane. Due to conservation of the discs’ volume during millisecond-scale dynamics, this lateral expansion leads to the axial contraction of the discs. The cumulative contraction of approximately a thousand discs results in the contraction of the photoreceptor OS by tens or even hundreds of nanometers. As detailed in Supplementary Information, these considerations yield a good match between the modeled and measured contraction amplitude across varying bleach levels (see Fig. S1). At the best fit, we obtained an initial membrane tension τ0 of 0.59 μN m−1 and a bending modulus κc = 0.23 × 10−19N m—within the ranges of the membrane surface tension and bending modulus in the literature: 0.1–1 μN m−1 and 0.5–2 × 10−19 N m30, respectively.

However, this quasistatic model failed to capture the latency of the contraction (see blue curves in Fig. 4B, C), indicating a potential involvement of viscous effects. One factor that could dampen the response, as proposed in our previous study30, is the viscous force exerted by surrounding fluid when individual discs expand laterally. Another mechanism, proposed in this study, arises from the friction when discs move axially in the cytoplasm. Axial shrinkage of each disc results in stretching of the spacers connecting adjacent discs31,42,43, which then causes discs and ROST to move axially. The viscous force induced by the surrounding cytoplasm during this axial movement dampens the contraction process.

A Diagram of a rod photoreceptor. The top right inset illustrates lateral disc expansion upon light absorption. The bottom inset depicts the inter-disc spacers connecting the discs. IS/OS inner segment/outer segment junction, ROST rod outer segment tips, RPE retinal pigment epithelium. B Experimentally measured ΔOPL response to a 1-ms flash and predictions of the quasistatic model and the planar & axial viscoelastic model. C Contraction rate obtained by time derivatives of the traces in (B). D The best-fit model and experimental data for latency of the maximum contraction rate with varying pulse durations (n = 5, see Fig. 1F). E Similar comparison as in (D) for varying pulse energies (n = 5, see Fig. 2E). Error bars in (D, E) indicate one standard deviation around the average.

A combined model considering both, the lateral and axial viscous and elastic forces applied to each disc, enabled a better fit to experimental results (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Information: Computational Model for ROS Contraction). As shown in Fig. 4B, C, using the 1-ms pulse measurement as an example, the model provides a better fit for the temporal evolution of ΔOPL than its quasistatic approximation. The best fit yielded damping coefficients of 4.0 × 105 N s m−3 for the lateral expansion of disc membranes and 4.4 × 104 N s m−3 for the axial movement of the discs. These damping coefficients correspond to the linear damping behavior caused by cytoplasmic sheets of approximately 10 nm and 100 nm in thickness, respectively44, which is reasonable for the membranous structure of ROS42,43. As shown in Fig. 4D, E, the viscoelastic model accurately predicts the latency of the maximum contraction for various pulse durations and energy levels, whereas the quasistatic model exhibits much faster dynamics (blue curves in Fig. 4B, C).

Reversed isomerization with UV flash

Previous studies have demonstrated that a near-UV flash delivered to Meta II can elicit an electrical signal of opposite polarity compared to typical ERP9,45. While the hyperpolarizing phase of the ERP is associated with the transition from Meta I to Meta II, near-UV photons can induce a reversed conformational change from Meta II to Meta III10. To assess the ORG response related to this process, a 1-ms flash at 385 nm was applied after the rhodopsin bleaching by a 1-ms green flash. Pulse energy of the green flash was sufficiently high (340 μJ, 3.6 × 108 photons/μm2 on the retina) to bleach nearly all rhodopsin, as validated by the very small residual response to the second green flash 200 ms later (Fig. 5A). At this pulse energy, thermal effects were still negligible compared to ORG signals (see “Discussion”).

A Control experiment: ORG responses elicited by two green flashes (1 ms, 340 μJ measured in front of the cornea, corresponding to 3.6 × 108 photons/μm2 on the retina) delivered 200 ms apart. B Response to a flash sequence of green-UV-green-UV, with a UV flash of 1 ms, 112 μJ. Given a transmittance of 0.54 through the anterior segment of the eye at 385 nm33,34 and an illumination area on the retina of 1.56 mm2, this corresponds to approximately 7.5 × 107 photons/μm2 incident on the retina. Insets show the first 10-ms temporal window. Red arrows indicate the amplitudes plotted in (C–E). C The first elongation amplitude as a function of UV pulse energy. D The second contraction amplitude as a function of UV pulse energy. E The second elongation amplitude as a function of UV pulse energy. Dots in (C–E) show measurements in individual rats (n = 5), and error bars represent one standard deviation (SD) around the average. F ORG responses to two UV pulses (3 ms, 336 μJ, 200-ms apart, n = 5). Insets show the first 30-ms temporal window.

UV flashes were delivered 100 ms after each green pulse at UV energy levels of 30, 70, 112, and 224 μJ, measured in front of the cornea. As shown in Fig. 5B, the first UV flash (1 ms, 112 μJ, 7.5 × 107 photons/μm2 on the retina), applied to an extensively bleached retina, elicited a pronounced elongation of the ROS (with ~10 ms time constant), suggesting a reversed response relative to the contraction induced by the first green flash. The second green flash, applied 100 ms after the UV pulse, induced stronger contraction compared to the control (Fig. 5A), implying partial recovery of photopigment, restoring its ability to respond to green photons. The final UV flash elicited another elongation, similar in amplitude to the first UV pulse.

Amplitude of the elongation produced by the first UV flash exhibited a saturating trend with pulse energy, as shown in Fig. 5C. As anticipated, higher energies of the first UV flash increased the contraction amplitude for the second green flash (Fig. 5D) since more photopigments sensitive to green photons were regenerated by more intense UV light, although this effect saturated beyond 112 μJ. Amplitude of the elongation induced by the final UV flash followed a pattern similar to that of the first one (Fig. 5E).

Remarkably, the UV flash evoked different ORG responses in light-adapted (Fig. 5B) and dark-adapted retinas (Fig. 5F). When delivered to a dark-adapted retina without a preceding green pulse, the UV flash elicited a rapid contraction by 200 nm (Fig. 5F), similar to the response observed with a green flash. After the rapid contraction, however, the ROS briefly expanded by a few tens of nm before undergoing a secondary, slow contraction. The second UV flash, 200 ms later, produced a small additional contraction (like the second green flash in Fig. 5A), but followed by a more pronounced elongation (~10 ms time constant), lasting for hundreds of ms.

Discussion

The measured ΔOPL in ROS can stem from a variation in the refractive index, a mechanical deformation, or a combination of both. To quantify the refractive index change due to isomerization of photopigments, the Kramers-Kronig transform was applied to their absorption spectra. Following photoisomerization, rhodopsin is converted to Meta II, leading to a pronounced shift of its absorption peak from 500 to 380 nm3,46,47, as shown in Fig. S5A. Assuming the other peaks in UV range do not change, the resulting refractive index change at the OCT center wavelength (840 nm) is on the order of 10−5, corresponding to ΔOPL < 1 nm along the ROS (Fig. S5B).

Light absorption in pigmented retinal layers, such as photoreceptor OS, retinal pigment epithelium, and pigmented choroid, also results in heating, which can change refractive index and induce thermal deformations48. Our thermo-mechanical model49 shows that the dominant effect is thermal expansion of the retinal layers. At the highest bleach level in our experiments, temperature rise is <0.5 °C and the associated thermal expansion of the outer segments is <10 nm (Fig. S6). This thermal effect is of the opposite sign and of a negligible amplitude compared to hundreds of nanometers of the ROS contraction observed in our experiments.

In COS, the rapid contraction (<20 ms) is followed by an expansion lasting several hundred milliseconds24, which has been attributed to osmolarity-driven water influx, swelling of cone opsins and disc membranes, and conformational changes in PDE6 during phototransduction27,29,31. Amplitude of both the rapid contraction and slow expansion increase with light intensity24. Like the temporal overlap between ERP and late receptor potential (LRP) in electrical recordings7,8, the expansion phase in cone ORG obscures part of the contraction.

In rod ORG, expansion is much weaker and slower, and hence it does not obscure the contraction. This could contribute to the significantly larger contraction amplitude observed in rat ROS (>200 nm, Fig. 2D) compared to that in human COS (~50 nm24). In fact, slow expansion was observed only at very low bleach levels (<3%), as can be seen in Figs. 2A and S7. At higher bleach levels, ROS remains contracted for at least 400 ms. One reason for small expansion could be structural: except for a few nascent disc membranes, ROS is primarily composed of densely packed, sealed discs enclosed within a tight plasma membrane3,13, which has very limited room for expansion, unlike COS, where the discs are infoldings of the common plasma membrane, providing plenty of room for expansion14. Lack of expansion and even a secondary contraction during the first 100 ms at higher bleach levels in ROS (Figs. 1B and 2A) indicate another potential contraction mechanism, which counterbalances the osmotic swelling at higher bleach levels.

The large difference between time constants of rod and cone disc membranes may also contribute to the much slower recovery of contraction in ROS. Patch clamp-recorded ERP in cones recovers within a few ms due to the passive discharge through the plasma membrane, governed by its resistance and capacitance7,8. The time constant of Meta II formation in human M-cone visual pigment, which induces the hyperpolarizing phase of the ERP, is approximately 6 ms50. This value is in the same range as the typical membrane time constant8, indicating that a passive discharge of the disc membrane in COS reduces the transmembrane potential change and the associated contraction amplitude. However, unlike plasma membrane, rod disc membrane has exceptionally high specific membrane resistance (on the order of MΩ cm2) due to the absence of ion channels51,52, yielding a much larger membrane time constant—on the order of seconds (with a typical specific membrane capacitance of 1 μF cm−2)6. Consequently, the very slow passive discharge of the disc membrane in rods maintains the hyperpolarization induced by the initial photoisomerization, as well as the associated mechanical contraction, for a long time.

Previous electrical recordings demonstrated that an intense 400-nm stimulus applied to a fully bleached retina induces electrical response opposite in polarity to the typical ERP9,45. Moreover, a second green flash following the 400-nm pulse elicits again an ERP response with the same shape as that of the pre-bleached retina (albeit with a lower amplitude), suggesting that photopigment was regenerated by the near-UV flash. The diagram of the photoisomerization and thermal relaxation pathways in rhodopsin shown in Fig. 6 suggests that (near-)UV light can trigger 15-anti/15-syn isomerization in Meta II, leading to formation of reverted-Meta (R-Meta), which is followed by Schiff base protonation, resulting in formation of Meta III3,46. When illuminated by green light, Meta III undergoes a 15-syn/15-anti isomerization around the Schiff base C=N bond, reverting to Meta I, which is then followed by Schiff base deprotonation, forming Meta II again. Hence, the Meta III photointermediate, though structurally different from the ground state rhodopsin, can absorb green light and induce similar state transitions (Fig. 6). We conjecture that the rapid (sub-ms) contraction of rod discs arises from the transition of Meta I to Meta II via Schiff base deprotonation (in hundreds of microseconds in rodents)5,9, while the reverse process—transition from R-Meta to Meta III via Schiff base re-protonation (~ms to s in various in vitro preparations)47—induces slower (~10 ms) ROS elongation.

As shown in Fig. 5F, when a UV flash is applied to a dark-adapted retina, the ROS undergoes a rapid contraction, similar to that observed with a green stimulus (Fig. 5A). Given that S-cones constitute only a small fraction (~0.05%) of photoreceptors in rats32, and that rhodopsin absorption at 385 nm is still approximately 20% of its peak absorption in the green range53, interference from S-cones should be minimal. Therefore, the rapid contraction in Fig. 5F is more likely to originate from the transition from rhodopsin to Meta II. As a result, prior to the second UV flash, the ROS harbors a mixture of rhodopsin, Meta II, and a small fraction of Meta III. Upon the second UV flash, three concurrent reaction pathways can be activated: (i) rhodopsin transitions through Meta I to Meta II, (ii) Meta II transitions to Meta III, and (iii) Meta III transitions back to Meta II through Meta I (see Fig. 6). The first and third pathways induce the ROS contraction, while the second pathway elicits elongation. The dynamic interplay of these processes governs the morphological response of the ROS in Fig. 5F.

ERG is widely used in basic studies of retinal physiology and for ophthalmic diagnostics54. ERP, which reflects the pigment isomerization processes, can provide information about the visual pigment mutations and visual retinoid cycle. The following slower component of the LRP or a-wave helps diagnose the issues associated with phototransduction. Since the rod surface membrane contains significantly fewer visual pigments than the isolated disc membranes enclosed within the plasma membrane5, the ERP amplitude, which reflects the charge shift across the plasma membrane, is much smaller in rods than in cones15,16. In contrast, the optical signature of photoisomerization in rods is much stronger than in cones and provides a very convenient label-free non-invasive alternative to ERG for retinal diagnostics. Due to cumulative motion of the isolated discs in rods, optical approach is far more sensitive than electrical recordings, reducing the need for multiple intense stimuli, and providing functional information, co-registered with structural OCT imaging, potentially down to single-cell resolution when combined with adaptive optics (AO)23,25,26. Different signatures of the isomerization (ERP, contraction of the OS) and phototransduction (LRP, expansion of OS in cones and under low stimuli in rods) enable differential diagnostics of the various aspects of photoreceptor’s dysfunction.

While the rod-dominant rat retina serves as an ideal model for investigating rod ORG responses, measurements in the hybrid human retina face additional challenges, such as differentiating cone and rod responses and dealing with larger head and eye movements. Nevertheless, a recent study in human subjects employed AO line-scan OCT to identify rod photoreceptors at 10° eccentricity and successfully measured rapid contraction in human rod OS55. Interestingly, the duration of this rapid contraction (~100 ms at 3.3% bleach level and ~300 ms at 39.4% bleach level) is much shorter than that observed in rodent rod OS. Although the exact reasons underlying this difference remain to be explored, this finding reconciles the absence of rapid contraction in previously reported human rod ORG signals, which were acquired at relatively low temporal resolution (6 Hz25 or 8 Hz56,57) and under relatively low bleach levels (≤1%57 and ≤4%25), or used seconds-long low power visual stimulation56. One possible explanation for the much shorter contraction duration in human rod OS is that the elongation of surrounding cones may affect the rod OS responses. In future studies, it would be interesting to measure human rod OS responses in peripheral retina, where cone density is much lower58, to further investigate potential crosstalk between rods and cones. In this case, resolving photoreceptors may not be necessary, which could allow non-AO OCT systems to detect the rapid OS contraction in human rods. Additionally, several efforts—including improved post-processing algorithms59,60,61, active eye-tracking62, and new OCT recording protocols63—are being explored to mitigate signal decorrelation during ORG measurements and facilitate the clinical translation of ORG techniques.

Methods

Phase-sensitive OCT imaging

The high-speed line-scan spectral-domain OCT was assembled according to the optical layout shown in Fig. 7. The OCT beam from the supercontinuum laser (FIR-9, NKT Photonics, Denmark) was collimated using lens CL1 (AC254-060-B, Thorlabs) and filtered through two spectral filters (Semrock: FF01-776/LP-25, Thorlabs: FESH0900), producing a bandwidth with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of about 120 nm centered at 840 nm.

A Top view (y-z plane) of the setup. CL collimating lens, SPF short pass filter, LPF long pass filter, CYL achromatic cylindrical lens doublet, L achromatic lens doublet, M mirror, RM reference mirror, BS beamsplitter, GS galvo scanner, DCM dichroic mirror, FM flippable mirror, PH pinhole, DPSS diode-pumped solid-state laser, FIR-9 NKT FIR-9 OCT laser. The effective focal lengths: CL1 = 60 mm, CYL1 = CYL1R = CYL2 = L4 = L8 = 250 mm, L0 = 150 mm, L1 = L1H = L7 = 100 mm, L2 = CYL3 = 75 mm, L3 = L1R = L2R = L2H = L6 = 200 mm, CL2 = L5 = 30 mm. (I): conjugate image planes. (P): conjugate pupil planes. Not to scale. B Unfolded x-z view of the OCT illumination path showing line-field on the retina. C Optical paths for green (520 nm) and UV (385 nm) stimulation. DCM1-2 Dichroic mirrors 1 and 2, R retinal plane. The effective focal lengths: LG2 = 30 mm, LUV1 = 100 mm, LUV2 = 35 mm.

The beam then passes through a cylindrical lens (CYL1), which forms a line image along the y-axis at the focal plane. Following optical conjugation through the afocal telescope L0-L1, the beam was divided into reference and sample arms using a non-polarizing beamsplitter (BSS11, Thorlabs) with a 30:70 (R:T) ratio. Two more afocal telescopes in the sample arm, L2-L3 and L4-L5, conjugate the one-dimensional galvo scanning (GS) mirror (8310K Series Galvanometer, Cambridge Technology) to the system pupil plane. The lens L5 and the animal fixation stage were mounted on a Badal platform, such that translating the platform alters the vergence of the beam entering the eye, enabling compensation for subject-induced defocus. The incident power on the cornea was 2.8 mW. The irradiated line length on the retina was estimated to be 330 μm, and the diffraction-limited resolution (FWHM) was estimated to be 3.6 μm. The elliptical reference beam after the beamsplitter was re-collimated by a cylindrical lens (CYL1R), followed by an afocal telescope (L1R-L2R). A prism pair (#43-649, Littrow Dispersion Prism, Edmund Optics) was used to balance the dispersion mismatch between the reference and sample arms. In the detection path, an anamorphic telescope (L2-CYL2-CYL3) was used to conjugate image planes for optimizing the spatial and spectral resolution simultaneously. An adjustable slit was placed at the image plane to minimize stray light or back-reflections from the contact lens.

The backscattered sample beam and reflected reference beam were diffracted by a 600 l/mm grating (WP-600/840-35 × 45, Wasatch Photonics), and the image was finally conjugated to the detector of the high-speed camera (Phantom v641) via the telescope (L6-L7), yielding a raw image size of 768 × 512 pixels (spectral × spatial). In this arrangement, each frame of the camera generated a B-scan of the retina. Data acquisition and real-time processing were implemented in a desktop client application developed using C# on the Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) framework (XAML 1.0) in Visual Studio 16.0, utilizing the National Instruments API version 19.0. The line-scan ophthalmoscope (LSO) camera (spL4096-140 km, Basler) was aligned to be parfocal with the OCT camera. LSO imaging was used for finding a focal plane of the retina, while adjusting the Badal platform, prior to OCT imaging.

Optical paths of retinal stimulation

The green flash path was coupled with the OCT illumination path using a dichroic mirror (NFD01-532-25 × 36, Semrock). The output of the green laser (520 nm semiconductor laser, Civillaser) was coupled into an optical fiber (MHP200L02 - Ø200 μm Core, 0.22 NA, Thorlabs) using an objective lens LG1 (Fig. 7C). The output of the fiber was optically conjugated to the system pupil plane via an afocal telescope (LG2-L5). The illuminated area on the retina was estimated to be 1.88 mm2, based on a standard rat eye model64.

For UV stimulus, the collimated output of a high-power LED (385 nm, SOLIS-385C, Thorlabs) was focused by LUV1 and illuminated a 2.5-mm pinhole (P2500K, Thorlabs) at an intermediate image plane, which was conjugated to the system pupil plane using an afocal telescope (LUV2-L5). At the pupil plane, the beam size was about 2 mm, ensuring that the beam will not be cropped by the rat pupil on its way to the retina. The illuminated area on the retina was estimated to be 1.56 mm2. The UV light was coaxially aligned with the OCT beam using DCM2 (FF495-Di03-25 × 36, Semrock).

Animal preparation

All experimental procedures were approved by the Stanford Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care and conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines and conformed to the Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO). Long Evans rats (male = 8, female = 7, age: 11–17 weeks) were used, with details provided in Table S2. Animal colonies were maintained at the Stanford Animal Facility in 12-h light/dark cycles with food and water ad libitum.

For all the ORG experiments, animals were dark-adapted more than 12 h overnight. Animals were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (75 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) injected intraperitoneally. The pupils were dilated with a mixture of 2.5% Phenylephrine Hydrochloride and 0.5% Tropicamide (Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY) ophthalmic solution and a zero-power contact lens (base curvature 3.00 mm, diameter 6.00 mm, optical power 0.00 D; Lakewood, CO 80226) was placed on the eye for imaging. The ORG recordings were performed in the inferonasal region. To minimize motion artifacts caused by respiration and heartbeat, rat’s head was stabilized using a custom-built fixation stage equipped with a bite bar and ear bars.

Data processing

MATLAB (2021a and 2022b, MathWorks, MA, USA) was used for OCT image processing, registration, and phase signal analysis. Python (3.9.2) was used for plotting figures.

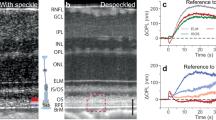

The complex-valued OCT signals were reconstructed following the conventional processing pipeline, i.e., k-linearization and discrete Fourier transform of the spectral interferogram captured by the camera. Subpixel-level bulk displacements between the first and subsequent B-scans were estimated by locating the peak of upsampled cross-correlation maps65, then each B-scan was registered to the first B-scan using our custom image registration algorithm61. The registered B-scans were flattened along the IS/OS band. The structural image displayed on a dB scale (Fig. 1A) was obtained by applying 20 × log10 to the amplitude component of complex-valued OCT images.

To extract ORG signals, we first calculated the temporal change of phase signals by computing the multiplication of each B-scan with the complex conjugate of the first B-scan,

where \(\tilde{I}(x,z,t)\) represents the complex-valued OCT images after registration and flattening. x, z, and t denote indices along the lateral, axial, and temporal dimensions, respectively. \({\tilde{I}}^{{{\rm{Tref}}}}\) is the time referenced complex-valued OCT signal.

The residual bulk phase errors were canceled out by calculating phase difference between two retinal layers. For each pixel in the target layer, denoted by (xtar, ztar), we selected a reference region from the reference layer—IS/OS in this study. The reference region was centered at xtar and spanned across adjacent 11 A-lines. The temporal phase change in the reference region, φref(xtar, t), can be calculated by,

where zu and zb denote the upper and lower boundaries of the reference layer, ∡ denotes the argument operator. Note that, to reduce SNR-dependent phase fluctuations when computing phase signals from speckle patterns, we used a two-dimensional reference region instead of a single pixel to calculate φref(xtar, t).

Finally, ORG signals can be obtained by

where j is the imaginary unit. We then applied the same process to every pixel in the target layer (3 pixels in depth and 512 pixels along the line direction), and calculated the average of extracted phase traces across different pixels, yielding φtar/ref(t). The phase signal can be converted into changes in OPL by,

where λc is the center wavelength of OCT imaging beam (840 nm).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and the Supplementary Information. An example dataset, comprising a 400-ms recording acquired at a frame rate of 10 kHz, can be downloaded from Zenodo66 or via the GitHub repository at https://github.com/optoretinography/ORG-signal-extraction67. The complete raw experimental data are too large to be publicly shared, yet they are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Requests will be fulfilled within 2 months. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The algorithm demo for the ORG signal extraction can be found at https://github.com/optoretinography/ORG-signal-extraction67.

References

Arshavsky, V. Y., Lamb, T. D. & Pugh Jr, E. N. G proteins and phototransduction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 153–187 (2002).

Birge, R. R. Nature of the primary photochemical events in rhodopsin and bacteriorhodopsin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1016, 293–327 (1990).

Hofmann, K. P. & Lamb, T. D. Rhodopsin, light-sensor of vision. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 93, 101116 (2023).

Sakmar, T. P. Rhodopsin early receptor potential revisited. Biophys. J. 77, 1189–1191 (1999).

Kessler, C., Tillman, M., Burns, M. E. & Pugh Jr, E. N. Rhodopsin in the rod surface membrane regenerates more rapidly than bulk rhodopsin in the disc membranes in vivo. J. Physiol. 592, 2785–2797 (2014).

Makino, C. L., Taylor, W. R. & Baylor, D. A. Rapid charge movements and photosensitivity of visual pigments in salamander rods and cones. J. Physiol. 442, 761–780 (1991).

Murakami, M. & Pak, W. L. Intracellularly recorded early receptor potential of the vertebrate photoreceptors. Vis. Res. 10, 965–XV (1970).

Hodgkin, A. L. & Obryan, P. M. Internal recording of the early receptor potential in turtle cones. J. Physiol. 267, 737–766 (1977).

Cone, R. A. & Cobbs, W. H.3rd Rhodopsin cycle in the living eye of the rat. Nature 221, 820–822 (1969).

Bartl, F. J. & Vogel, R. Structural and functional properties of metarhodopsin III: recent spectroscopic studies on deactivation pathways of rhodopsin. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 9, 1648–1658 (2007).

Müller, W. & Töpke, H. The early receptor potential (ERP). Doc. Ophthalmol. 66, 35–74 (1987).

Peichl, L. Diversity of mammalian photoreceptor properties: adaptations to habitat and lifestyle? Anat. Rec. A Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 287, 1001–1012 (2005).

Volland, S. et al. Three-dimensional organization of nascent rod outer segment disk membranes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 14870–14875 (2015).

Mustafi, D., Engel, A. H. & Palczewski, K. Structure of cone photoreceptors. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 28, 289–302 (2009).

Goldstein, E. B. Contribution of cones to the early receptor potential in the rhesus monkey. Nature 222, 1273–1274 (1969).

Goldstein, E. B. & Berson, E. L. Cone dominance of the human early receptor potential. Nature 222, 1272–1273 (1969).

Izatt, J. A, Choma, M. A & Dhalla, A.-H. Theory of Optical Coherence Tomography 65–94 (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

Choma, M. A., Ellerbee, A. K., Yang, C., Creazzo, T. L. & Izatt, J. A. Spectral-domain phase microscopy. Opt. Lett. 30, 1162–1164 (2005).

Makita, S., Hong, Y., Yamanari, M., Yatagai, T. & Yasuno, Y. Optical coherence angiography. Opt. Express 14, 7821–40 (2006).

Jonnal, R. S., Kocaoglu, O. P., Wang, Q., Lee, S. & Miller, D. T. Phase-sensitive imaging of the outer retina using optical coherence tomography and adaptive optics. Biomed. Opt. Express 3, 104–124 (2012).

Hillmann, D. et al. In vivo optical imaging of physiological responses to photostimulation in human photoreceptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 13138–13143 (2016).

Azimipour, M., Migacz, J. V., Zawadzki, R. J., Werner, J. S. & Jonnal, R. S. Functional retinal imaging using adaptive optics swept-source OCT at 1.6 MHz. Optica 6, 300–303 (2019).

Zhang, F., Kurokawa, K., Lassoued, A., Crowell, J. A. & Miller, D. T. Cone photoreceptor classification in the living human eye from photostimulation-induced phase dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 7951–7956 (2019).

Pandiyan, V. P. et al. The optoretinogram reveals the primary steps of phototransduction in the living human eye. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc1124 (2020).

Azimipour, M. et al. Optoretinogram: optical measurement of human cone and rod photoreceptor responses to light. Opt. Lett. 45, 4658–4661 (2020).

Lassoued, A. et al. Cone photoreceptor dysfunction in retinitis pigmentosa revealed by optoretinography. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2107444118 (2021).

Pandiyan, V. P., Nguyen, P. T., Pugh Jr, E. N. & Sabesan, R. Human cone elongation responses can be explained by photoactivated cone opsin and membrane swelling and osmotic response to phosphate produced by RGS9-catalyzed GTPase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2202485119 (2022).

Tan, B. et al. Light-evoked deformations in rod photoreceptors, pigment epithelium and subretinal space revealed by prolonged and multilayered optoretinography. Nat. Commun. 15, 5156 (2024).

Tomczewski, S. et al. Photopic flicker optoretinography captures the light-driven length modulation of photoreceptors during phototransduction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2421722122 (2025).

Boyle, K. C. et al. Mechanisms of light-induced deformations in photoreceptors. Biophys. J. 119, 1481–1488 (2020).

Zhang, P. et al. In vivo optophysiology reveals that g-protein activation triggers osmotic swelling and increased light scattering of rod photoreceptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E2937–E2946 (2017).

Szél, A. & Röhlich, P. Two cone types of rat retina detected by anti-visual pigment antibodies. Exp. Eye Res. 55, 47–52 (1992).

Gorgels, T. G. M. F. & Norren, D. V. Spectral transmittance of the rat lens. Vis. Res. 32, 1509–1512 (1992).

Merriam, J. C. et al. An action spectrum for UV-B radiation and the rat lens. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 2642–2647 (2000).

Berger, A. et al. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the rodent eye: highlighting layers of the outer retina using signal averaging and comparison with histology. PLoS ONE 9, e96494 (2014).

Williams, T. P. Photoreversal of rhodopsin bleaching. J. Gen. Physiol. 47, 679–689 (1964).

Pugh, E. N. Rhodopsin flash photolysis in man. J. Physiol. 248, 393–412 (1975).

Gupta, B. D., Goyal, I. C. & Ghatak, A. K. Flash photolysis of rhodopsin in rabbit. Biophys. Struct. Mech. 4, 129–138 (1978).

Ling, T. et al. High-speed interferometric imaging reveals dynamics of neuronal deformation during the action potential. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 10278–10285 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Imaging action potential in single mammalian neurons by tracking the accompanying sub-nanometer mechanical motion. ACS Nano 12, 4186–4193 (2018).

You, H., Li, H. & Ling, T. Electromechanical deformation of biological neurons: an intrinsic marker for label-free functional neuroimaging. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 58, 053002 (2025).

Pöge, M. et al. Determinants shaping the nanoscale architecture of the mouse rod outer segment. eLife 10, e72817 (2021).

Nickell, S., Park, P. S.-H., Baumeister, W. & Palczewski, K. Three-dimensional architecture of murine rod outer segments determined by cryoelectron tomography. J. Cell Biol. 177, 917–925 (2007).

Ashmore, J. Cochlear outer hair cell motility. Physiol. Rev. 88, 173–210 (2008).

Cone, R. A. Early receptor potential: photoreversible charge displacement in rhodopsin. Science 155, 1128–1131 (1967).

Ritter, E., Zimmermann, K., Heck, M., Hofmann, K. P. & Bartl, F. J. Transition of rhodopsin into the active metarhodopsin II state opens a new light-induced pathway linked to Schiff base isomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48102–48111 (2004).

Ritter, E., Elgeti, M., Hofmann, K. P. & Bartl, F. J. Deactivation and proton transfer in light-induced metarhodopsin II/metarhodopsin III conversion. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 10720–10730 (2007).

Veysset, D., Zhuo, Y., Hattori, J., Buckhory, M. & Palanker, D. Interferometric thermometry of ocular tissues for retinal laser therapy. Biomed. Opt. Express 14, 37–53 (2023).

Zhuo, Y. et al. Retinal thermal deformations measured with phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography in vivo. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 1–10 (2025).

Dhankhar, D., Salom, D., Palczewski, K. & Rentzepis, P. M. Ultrafast spectra and kinetics of human green-cone visual pigment at room temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2214276120 (2023).

Uhl, R., Kuras, P. V., Anderson, K. & Abrahamson, E. W. A light scattering study on the ion permeabilities of dark-adapted bovine rod outer segment disk membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 601, 462–477 (1980).

Rebrik, T. I., Kalamkarov, G. R. & Ostrovskiĭ, M. A. [The absence of channel structures in the photoreceptor membrane of the rod disc]. Biofizika 31, 985–989 (1986).

Sakai, K., Shichida, Y., Imamoto, Y. & Yamashita, T. Creation of photocyclic vertebrate rhodopsin by single amino acid substitution. eLife 11, e75979 (2022).

Perlman, I. The electroretinogram: ERG. in Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System (eds Kolb, H., Fernandez, E. & Jones, B. et al.) (University of Utah Health Sciences Center, 2001).

Li, H. et al. Optoretinography reveals rapid rod photoreceptor movement upon photoisomerization. (2025) in press.

Pfäffle, C. et al. Simultaneous functional imaging of neuronal and photoreceptor layers in living human retina. Opt. Lett. 44, 5671–5674 (2019).

Pfäffle, C. et al. Unraveling the functional signals of rods and cones in the human retina: separation and analysis. Front. Ophthalmol. 4, 1340692 (2024).

Curcio, C. A., Sloan, K. R., Kalina, R. E. & Hendrickson, A. E. Human photoreceptor topography. J. Comp. Neurol. 292, 497–523 (1990).

Spahr, H. et al. Phase-sensitive interferometry of decorrelated speckle patterns. Sci. Rep. 9, 11748 (2019).

Vienola, K. V., Valente, D., Zawadzki, R. J. & Jonnal, R. S. Velocity-based optoretinography for clinical applications. Optica 9, 1100–1108 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Phase-restoring subpixel image registration: enhancing motion detection performance in Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 58, 145102 (2025).

Wong, J. H., Luo, S., Hosseinaee, Z., Feroldi, F. & Roorda, A. Optoretinography with actively stabilized adaptive optics optical coherence tomography. Biomed. Opt. Express 16, 3222–3236 (2025).

Gong, Z., Shi, Y., Liu, J., Sabesan, R. & Wang, R. K. Light-adapted flicker-optoretinography based on raster-scan optical coherence tomography towards clinical translation. Biomed. Opt. Express 15, 6036–6051 (2024).

Campbell, M. C. & Hughes, A. An analytic, gradient index schematic lens and eye for the rat which predicts aberrations for finite pupils. Vis. Res. 21, 1129–1148 (1981).

Guizar-Sicairos, M., Thurman, S. T. & Fienup, J. R. Efficient subpixel image registration algorithms. Opt. Lett. 33, 156–158 (2008).

Li, H. Example dataset for optoretinography (ORG) signal extraction. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17193984 (2025).

Li, H. optoretinography/org-signal-extraction: Version 1.0.0. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17197765 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. David Veysset for fruitful discussions of the ROS modeling and Dr. Mohammad Asif Zaman for help with the data verification. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (U01 EY032055, D.P.), Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-20-1-0186, D.P.), and Research to Prevent Blindness (D.P.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z., H.L. and D.P. designed research; Y.Z. and H.L. built the optical setup; Y.Z., M.B. and D.P.H. performed experiments; Y.Z. and H.L. processed the experimental data; H.L. and Y.Z. performed computational modeling; Y.Z., H.L. and D.P. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Daniel Hammer, Ravi Jonnal, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuo, Y., Li, H., Bhuckory, M. et al. Interferometric imaging of the reversible rhodopsin dynamics in the living rat eye. Nat Commun 16, 10730 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65759-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65759-z