Abstract

The development of robust, practical, and chemoselective methods for introducing the difluoromethyl (CF₂H) group into organic molecules is highly sought after in the fields of pharmaceutical and agrochemical design. Herein, we report a Fe/Ni dual-transition-metal electrocatalytic strategy for difluoromethylation of (hetero)aryl halides, using difluoroacetate—the most abundant source of the CF₂H group—as an effective difluoromethylating reagent. A diverse array of aryl and heteroaryl halides, bearing synthetically useful functional groups, can be readily converted into the corresponding difluoromethylated products with good efficiency. This difluoromethylation protocol is readily scalable and is successfully applied to the preparation and late-stage functionalization of bioactive molecules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

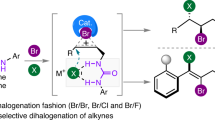

Owing to the unique stability, physicochemical, and biological properties of fluorinated compounds, the development of new and efficient approaches for the installation of fluorinated alkyl groups into organic molecules remains highly desirable in the synthetic community1,2,3,4,5,6,7. In this context, the CF2H group has recently attracted considerable attention in medicinal chemistry8,9,10. The highly polarized C–H bond within the CF2H group endows it with a potent capacity to participate in hydrogen bonding interactions, making it a viable bioisostere for alcohol, thiol, and amino groups in drug molecular design. Moreover, the CF2H group can also modulate lipophilicity and influence the conformation of molecules containing this functionality. As a consequence, the CF2H group could be found in various biologically active compounds, such as drug candidates6 and agrochemicals7, and there is a growing demand to develop sustainable and practical protocols for the introduction of the CF2H group with readily available difluoromethylating agents11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. As an elegant example, Xu and co-workers devised a new difluoromethylating reagent, CF2HSO2NHNHBoc, which is air-stable and can be readily obtained in one synthetic step from commercially available reagents. Under electrochemical ferrocene-catalyzed conditions, CF2H radical can be generated without the need for chemical oxidants and has been successfully applied in an alkyne addition followed by a challenging 7-membered ring-forming homolytic aromatic substitution reaction for the synthesis of fluorinated dibenzazepines18. Indeed, difluoromethylation with CF2H radical constitutes an attractive strategy, and recent advances in this direction have led to the invention of a wide range of new difluoromethylating agents, enabling mild and selective ways to construct C(sp3)–CF2H and C(sp2)–CF2H bonds23,24,25,26. However, these methods are often constrained by the requirement for stoichiometric redox reagents to produce CF2H radicals via single-electron oxidation or reduction reactions, which might decrease functional group compatibility and lead to the generation of wasteful and often environmentally hazardous byproducts (Fig. 1A).

Difluoroacetic acid is a chemical feedstock that can be considered the most promising source of the CF2H group due to its availability and stability. However, the demanding oxidation potential of CF2HCOO– [Ep/2 = 2.09 V versus Ag/AgCl, MeCN] substantially hampers its application in radical difluoromethylation [Fig. 1B, eq. (1)]27. Indeed, direct radical decarboxylation of difluoroacetate for the generation of CF2H radicals typically necessitates harsh reaction conditions, such as strong chemical oxidants or large operating cell potentials, which would limit the reaction efficiency and restrict the substrate scope and functional group tolerance28,29,30. Recently, photoredox iron catalysis has been demonstrated in hydrofluoroalkylation of alkenes with diverse fluoroalkyl carboxylic acids as fluoroalkyl radical precursors through an inner-sphere electron transfer activation mechanism31,32, in which a weakly oxidizing iron catalyst could facilitate the radical decarboxylation of redox-reticent alkyl carboxylic acids under mild reaction conditions [Fig. 1B, eq. (2)]33,34,35. While decarboxylative arylation of aliphatic carboxylic acids has garnered considerable interest in recent years36,37,38,39,40,41,42, achieving direct decarboxylative arylation of difluoroacetate with aryl halides for the synthesis of difluoromethylarenes is still an elusive goal in the synthetic chemistry community [Fig. 1B, eq. (3)]. Given the pronounced significance of C(sp2)–CF2H motif in medicinal chemistry43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53, the direct and efficient use of cost-effective and atom-economic difluoroacetate as the CF2H source for the preparation of difluoromethylarenes would be a significant advancement in synthetic chemistry.

Electrophotocatalysis has recently emerged as a powerful synthetic platform, unlocking radical transformations beyond the reach of photochemistry or electrochemistry alone54,55,56,57,58,59. For instance, this strategy has been successfully applied in chemoselective and stereoselective C(sp3)–H functionalization in a more sustainable manner60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69. In particular, studies on decarboxylative functionalization of alkyl carboxylic acids have shown that the corresponding alkyl radicals could be generated electrophotochemically under mild and environmentally friendly conditions70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77. Furthermore, their subsequent interaction with transition metal catalysis, such as nickel powered by cathode reduction, can be effectively harnessed for the development of radical-based redox-neutral coupling reactions78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86.

Here, we show a Fe/Ni dual-transition-metal electrocatalytic protocol for difluoromethylation of (hetero)aryl halides using readily available potassium difluoroacetate as the difluoromethylating reagent. Specifically, electrophotochemical Fe-catalyzed decarboxylation of difluoroacetate is applied for the generation of highly reactive CF2H radical at the anode. Concurrently, electrochemical Ni catalysis, driven by cathode reduction, has been utilized for the activation of aryl halides. This catalytic system allows the construction of C(sp2)–CF2H bonds from a broad spectrum of aryl and heteroaryl halides along with potassium difluoroacetate with high reaction efficiency (Fig. 1C).

Results and Discussion

Reaction discovery and optimization

We began our investigation by a strategic combination of iron and nickel catalysis under electrophotochemical conditions. Achieving the desired difluoromethylation of aryl halides using our dual-transition-metal electrocatalytic strategy would necessitate the simultaneous activation of two transition metal catalysts at both electrodes, in which each catalyst independently operates on its respective redox event78,79. Therefore, the reaction was carried out in a straightforward, undivided cell setup, equipped with two carbon-felt electrodes and maintained at an applied cell potential (Ecell) of 2.3 V (corresponding to an initial anodic potential of ca. 0.50 V versus the ferrocenium ion/ferrocene redox couple) while being irradiated with 400 nm light-emitting diodes (LEDs). The use of phthalimide as an additive was believed to stabilize the putative arylnickel(II) species, thus improving the reaction efficiency of radical-based convergent paired electrolysis39,42,81,82. With 4,4´-di-tert-butyl-2,2´-bipyridine (tBubpy) as ligand to the nickel center, the reaction of ethyl 4-bromobenzoate 1 with potassium difluoroacetate was able to yield the desired decarboxylative coupling product 2 with 80% isolated yield (Table 1, entry 1). As expected, reaction in the absence of phthalimide led to a dramatically diminished yield (entry 2). Although electrolyte could be replaced with TBABF4 or even be omitted from the reaction system, the addition of TBABr as electrolyte was essential for high reaction efficiency (entries 3 and 4). The applied cell potential of the reaction could be lowered to 2.0 V, yet still giving the coupling product in 51% yield (entry 5). Other iron salts, such as FeCl2 and FeBr2, also proved to be competent catalyst precursors in this catalytic system (entry 6). A series of control experiments was conducted by omitting each component, thereby elucidating the pivotal roles of iron, nickel, electrical energy, and light irradiation in facilitating the desired transformation (entries 7–10).

Substrate scope

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, we then evaluated the generality of the aryl halide component in this dual transition metal-catalyzed electrophotochemical difluoromethylation protocol. As summarized in Fig. 2, a broad range of aryl halides with different substituents were found to be suitable coupling partners in the reaction, generating the desired difluoromethylarenes in moderate to good yields (Fig. 2A, 2–25, 48–80% yield). Aryl bromides with both electron-withdrawing and electron-neutral groups performed well to furnish the decarboxylative coupling products with good reaction efficiency (2 and 3, 80 and 77% yield, respectively). In addition, aryl iodides were also found to be competent substrates for the reaction, giving the corresponding difluoromethylarenes with good reaction yields (4 and 5, 74 and 78% yield, respectively). Importantly, the very mild reaction conditions imparted by electrophotochemical transition metal catalysis made accessible a broad scope of difluoromethylarenes with a diverse range of functional groups, including esters (2, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, and 13), ketones (9, 10, and 11), and halides (12 and 13). In particular, the halide functional handles might be subsequently elaborated using orthogonal technologies, e.g., aromatic substitution and cross-coupling reactions to produce more synthetically important molecular structures. In addition, medicinally relevant sulfonamide could be smoothly incorporated into the substrates, with no significant effect on the reaction efficiency (14 and 15). We further expanded the reaction scope to various other heteroarenes including dibenzothiophenes (16 and 17), indazoles (18 and 19), and pyridines (20–25) given their widespread prevalence in pharmaceutical chemistry. All of these aryl bromides were successfully transformed into the corresponding difluoromethylarenes with synthetically useful reaction efficiency. Notably, activated aryl chlorides could also be employed as coupling partners in the reaction to yield the desired products with comparable yields (24 and 25).

A Synthesis of difluoromethyl arenes and heteroarenes. B Synthesis of difluoromethyl derivatives of bioactive molecules. All yields are of isolated products. Unless otherwise noted, reaction conditions were as follows: Aryl halides (0.2 mmol, 1.0 eq.), CF2HCO2K (1.0 mmol, 5.0 eq.), Fe(OTf)2 (0.03 mmol, 15 mol%), NiBr2·diglyme (0.03 mmol, 15 mol%), tBubpy (0.03 mmol, 15 mol%), TBABr (0.3 mmol, 1.5 eq.), phthalimide (0.2 mmol, 1.0 eq.), DMSO (4.0 mL), carbon felt anode, carbon felt cathode, under N2, undivided cell, 400 nm 10 W for 12 h.

The versatility of this method was further highlighted by its capability for late-stage difluoromethylation, providing streamlined access to molecules of pharmaceutical relevance (Fig. 2B). First, difluoromethylated derivatives generated from bioactive molecules including citronellol (26), abietic acid (27), oxaprozin (28), menthol (29), naproxen (30), and ibuprofen (31) could be readily obtained. Notably, functionalities that are susceptible to radical addition, such as alkene (26) and diene (27), can be successfully engaged in this radical decarboxylative arylation. Further, CF2H-containing analogs of indometacin (32), sulfadimethoxine (33), meclizine (34), and celecoxib (35) were successfully synthesized from the corresponding aryl bromides. Finally, direct difluoromethylation of phenylalanine-derived aryl bromide led to the formation of product 36 in 61% yield without erosion of the stereoselectivity; due to the capacity of the CF2H group to serve as a lipophilic hydrogen bond donor, it could potentially function as a tyrosine analog in medicinal chemistry. These reaction results, together with those depicted in Fig. 2A, clearly demonstrated the promising application of this dual transition metal-catalyzed electrochemical decarboxylative difluoromethylation method, especially considering the exceptional compatibility with functionally diverse groups that are significant in the context of medicinal chemistry.

Mechanistic studies and reaction scale-up in flow

Cyclic voltammetry studies of potassium difluoroacetate with TBABF4 as the supporting electrolyte indicated that no redox event could be observed between 0 and 0.8 V (Supplementary Fig. S4). However, with TBABr as the electrolyte, a distinct anodic event was observed with an onset potential of 0.12 V, due to the oxidation of the bromide anion in the reaction system (Fig. 3A, B). The iron catalyst showed a quasi-reversible redox feature at – 0.20 V, which we attributed to the FeIII/FeII redox couple of the iron catalyst itself (Fig. 3A, B, red line). Further addition of potassium difluoroacetate resulted in a cathodic shift of the redox wave. This shift likely arose from the formation of Fe(II) carboxylate, and the generation of Fe(III) species was facilitated by the coordination of the carboxylate to the Fe center (Fig. 3A, B, blue line). The formation of the CF2H radical was supported by the radical trapping experiment; in the presence of the radical scavenger 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO), the desired decarboxylative difluoromethylation of aryl bromide 1 was completely inhibited, with the TEMPO-trapped adduct 37 being formed in 8% yield (Fig. 3B). The electrophotochemical Fe-catalyzed mechanism allows the radical decarboxylation of difluoroacetate to occur in a manner that is much more controlled than those through direct voltage-gated pathways, leading to the observed mild reaction conditions with high chemoselectivity. To support this hypothesis, we designed and performed a controlled potential electrolysis experiment, in which the application of a – 0.20 V anodic potential proved sufficient in promoting the difluoromethylation/cyclization reaction of 38, giving the difluoromethylated oxindole 39 in 20% yield (Fig. 3C).

To confirm the formation of arylnickel(II) species in the reaction, we synthesized an arylnickel(II) complex 40 and performed a series of stoichiometric experiments. First, reactions of potassium difluoroacetate with nickel complex 40, in the presence of a stoichiometric amount of Fe(OTf)3, revealed that the difluoromethylated product 10 can only be generated upon light irradiation (Fig. 3D). These results clearly indicated the essential role of light irradiation for the reaction. When the reaction was performed in the anode compartment at a controlled potential of – 0.2 V, utilizing a setup that isolated the anode from the cathode with a sintered glass frit to prevent bulk mixing of liquids within both compartments, the desired product 10 was obtained with 18% yield (Fig. 3E). This experimental result is in accordance with our mechanistic hypotheses that the arylnickel(II) species formed at cathode is able to transfer into the bulk solution and productively react with the CF2H radical generated by electrophotochemical Fe-catalyzed decarboxylation in the anode compartment, thus achieving a challenging radical-based convergent paired electrocatalytic system81,82.

Finally, we endeavored to showcase the synthetic utility of this dual transition metal electrocatalytic approach for the difluoromethylation of aryl halides by establishing a gram-scale procedure. However, initial attempts to scale up the reaction to 5 mmol using batch cells resulted in a significantly lower isolated yield compared to that obtained from the small-scale reaction (54 vs 80%). We speculated that the reduced reaction efficiency might stem from limitations in light absorption, which could impact the photoredox process. Consequently, a continuous flow electrochemical setup featuring a larger photochemical chamber was designed to enhance the kinetics of the photoredox step in the catalytic cycle. After optimizing several reaction parameters, the reaction yield was improved to 71%. Notably, applying this continuous flow protocol enabled the reaction to be readily scaled up to 10 mmol scale without further optimization of the reaction conditions by using 5% mmol loading of the Fe catalyst, yet maintaining comparable reaction efficiency (Fig. 3F). The success of the continuous flow electrophotochemical protocol further confirms that the electrochemically generated transition metal complexes are sufficiently stable to migrate into the bulk solution, thereby enabling subsequent photoredox processes for radical decarboxylative difluoromethylation of aryl halides. More importantly, it is also consistent with our proposed stepwise energy input activation mechanism for the reaction.

Collectively, our experimental observations and mechanistic data support the mechanistic scenario proposed in Fig. 4. The electrophotochemical Fe-catalyzed radical decarboxylation of difluoroacetate at the anode produced the CF2H radical 41 in a controllable and homogeneous fashion. The coordination of the carboxylate to the Fe center makes the generation of photoredox-active iron carboxylates 42 more feasible. Concurrently, catalytically active Ni(I) species 43, produced by cathode reduction, would react with aryl halide via oxidative addition to give 44. After gaining one electron from the cathode, the generated arylnickel(II) species 45 would be sufficiently stable to migrate into the bulk solution. The phthalimide additive (Phth) may act as a ligand to stabilize the presumed arylnickel(II) species 45. At this stage, radical addition of the CF2H radical 41 to nickel complex 45 delivered the desired difluoromethylation product upon reductive elimination and regenerated Ni(I) species 43 for the next catalytic cycle.

In summary, we have successfully developed a practical electrophotocatalytic method for the difluoromethylation of (hetero)aryl halides, using readily available potassium difluoroacetate as the CF2H radical precursor. This dual transition metal electrocatalytic system exhibits exceptional functional group compatibility and has been effectively demonstrated through the late-stage functionalization of pharmaceutically relevant molecules. Additionally, a continuous flow electrochemical setup has been devised for gram-scale synthesis, showing promise for practical synthetic applications. Given the widespread applicability of the CF2H group in medicinal chemistry, we anticipate that researchers in both laboratory and process would find this work to be of high synthetic value.

Methods

General procedure for decarboxylative difluoromethylation of aryl halides

Pre-catalyst solution

A pre-catalyst solution was prepared by combining NiBr2•diglyme (10.6 mg, 15 mol%) and 4,4’-di-tert-butyl-2,2’-bipyridine (8.0 mg, 15 mol%) in 4 mL of anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), stirred for 30 min under a nitrogen atmosphere before use.

Reaction setup

An oven-dried two-neck tube was equipped with a stir bar, a rubber septum, a threaded Teflon cap fitted with electrical feedthroughs, two carbon felt anodes (0.8 × 1.7 cm2, connected to the electrical feedthrough via a 9.0 cm in length, 2.0 mm in diameter graphite rod). Under nitrogen atmosphere, aryl halide (0.2 mmol, 1.0 eq.), CF2HCO2K (134.1 mg, 1.0 mmol, 5.0 eq.), TBABr (96.7 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.5 eq.), phthalimide (29.4 mg, 0.2 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and Fe(OTf)2 (10.6 mg, 0.03 mmol, 15 mol%) were added, followed by subsequent addition of the pre-catalyst solution. The reaction mixture was then sparged with nitrogen for 5 minutes and maintained under nitrogen atmosphere with a balloon. The reaction was irradiated with LEDs (10 W, 400 nm, 1.0 cm away) under the vessel and electrolysis was initiated at a constant cell potential of 2.3 V. After 12 h at room temperature, the photolysis and electrolysis were terminated, the tube cap was removed, and the electrodes were rinsed with ethyl acetate (EtOAc), which was combined with the crude mixture. The organic layers were further washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude material was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to give the desired product.

Data availability

Materials and methods, optimization studies, experimental procedures, mechanistic studies, 1H NMR spectra, 13C NMR spectra and mass spectrometry data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information. Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Kirsch, P. Modern fluoroorganic chemistry. (Wiley, 2013).

Ni, C., Hu, M. & Hu, J. Good partnership between sulfur and fluorine: sulfur-based fluorination and fluoroalkylation reagents for organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 115, 765–825 (2015).

Alonso, C., Martínez de Marigorta, E., Rubiales, G. & Palacios, F. Carbon trifluoromethylation reactions of hydrocarbon derivatives and heteroarenes. Chem. Rev. 115, 1847–1935 (2015).

Ni, C. & Hu, J. The unique fluorine effects in organic reactions: recent facts and insights into fluoroalkylations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 5441–5454 (2016).

Szpera, R., Mosley, D. F. J., Smith, L. B., Sterling, A. J. & Gouverneur, V. The fluorination of C−H bonds: developments and perspectives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 14824–14848 (2019).

Inoue, M., Sumii, Y. & Shibata, N. Contribution of organofluorine compounds to pharmaceuticals. ACS Omega 5, 10633–10640 (2020).

Ogawa, Y., Tokunaga, E., Kobayashi, O., Hirai, K. & Shibata, N. Current contributions of organofluorine compounds to the agrochemical industry. iScience 23, 101467 (2020).

Sap, J. B. I. et al. Late-stage difluoromethylation: concepts, developments and perspective. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 8214–8247 (2021).

Sessler, C. D. et al. CF2H, a hydrogen bond donor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9325–9332 (2017).

Yerien, D. E., Barata-Vallejo, S. & Postigo, A. Difluoromethylation reactions of organic compounds. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 14676–14701 (2017).

Xie, Q. & Hu, J. A journey of the development of privileged difluorocarbene reagents TMSCF2X (X=Br, F, Cl) for organic synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 57, 693–713 (2024).

Fujiwara, Y. et al. A new reagent for direct difluoromethylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 1494–1497 (2012).

Lin, Q.-Y., Xu, X.-H., Zhang, K. & Qing, F.-L. Visible-light-induced hydrodifluoromethylation of alkenes with a bromodifluoromethylphosphonium bromide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 1479–1483 (2016).

Rong, J. et al. Radical fluoroalkylation of isocyanides with fluorinated sulfones by visible-light photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 2743–2747 (2016).

Noto, N., Koike, T. & Akita, M. Metal-free di- and tri-fluoromethylation of alkenes realized by visible-light-induced perylene photoredox catalysis. Chem. Sci. 8, 6375–6379 (2017).

Miao, W. et al. Iron-catalyzed difluoromethylation of arylzincs with difluoromethyl 2-pyridyl sulfone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 880–883 (2018).

Merchant, R. R. et al. Modular radical cross-coupling with sulfones enables access to sp3-rich (fluoro)alkylated scaffolds. Science 360, 75–80 (2018).

Xiong, P., Xu, H.-H., Song, J. & Xu, H.-C. Electrochemical difluoromethylarylation of alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2460–2464 (2018).

Kim, S. & Kim, H. Cu-electrocatalysis enables vicinal bis(difluoromethylation) of alkenes: unraveling dichotomous role of Zn(CF2H)2(DMPU)2 as both radical and anion source. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 22498–22508 (2024).

Kim, S. et al. Radical hydrodifluoromethylation of unsaturated C−C bonds via an electroreductively triggered two-pronged approach. Commun. Chem. 5, 96 (2022).

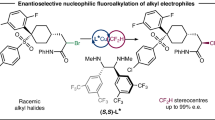

Zhao, X., Wang, C., Yin, L. & Liu, W. Highly enantioselective decarboxylative difluoromethylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 29297–29304 (2024).

Ding, D. et al. Enantioconvergent copper-catalysed difluoromethylation of alkyl halides. Nat. Catal. 7, 1372 (2024).

Li, X. & Song, Q. Introduction of difluoromethyl through radical pathways. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 27, e202400423 (2024).

Kisukuri, C. M. et al. Electrochemical installation of CFH2−, CF2H−, CF3−, and perfluoroalkyl groups into small organic molecules. Chem. Rec. 21, 2502–2525 (2021).

Lemos, A., Lemaire, C. & Luxen, A. Progress in difluoroalkylation of organic substrates by visible light photoredox catalysis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 361, 1500–1537 (2019).

Koike, T. & Akita, M. New horizons of photocatalytic fluoromethylative difunctionalization of alkenes. Chem 4, 409–437 (2018).

Qi, J. et al. Electrophotochemical synthesis facilitated trifluoromethylation of arenes using trifluoroacetic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 24965–24971 (2023).

Arai, K., Watts, K. & Wirth, T. Difluoro- and trifluoromethylation of electron-deficient alkenes in an electrochemical microreactor. ChemistryOpen 3, 23–28 (2014).

Tung, T. T., Christensen, S. B. & Nielsen, J. Difluoroacetic acid as a new reagent for direct C−H difluoromethylation of heteroaromatic compounds. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 18125–18128 (2017).

Meyer, C. F., Hell, S. M., Misale, A., Trabanco, A. A. & Gouverneur, V. Hydrodifluoromethylation of alkenes with difluoroacetic acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 8829–8833 (2019).

de Groot, L. H. M., Ilic, A., Schwarz, J. & Wärnmark, K. Iron photoredox catalysis–past, present, and future. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 9369–9388 (2023).

Abderrazak, Y., Bhattacharyya, A. & Reiser, O. Visible-light-induced homolysis of earth-abundant metal-substrate complexes: a complementary activation strategy in photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21100–21115 (2021).

Bian, K.-J. et al. Photocatalytic hydrofluoroalkylation of alkenes with carboxylic acids. Nat. Chem. 15, 1683–1692 (2023).

Qi, X.-K. et al. Photoinduced hydrodifluoromethylation and hydromethylation of alkenes enabled by ligand-to-iron charge transfer mediated decarboxylation. ACS Catal. 14, 1300–1310 (2024).

Jiang, X. et al. Iron photocatalysis via Brønsted acid-unlocked ligand-to-metal charge transfer. Nat. Commun. 15, 6115 (2024).

Zuo, Z. et al. Merging photoredox with nickel catalysis: coupling of α-carboxyl sp3-carbons with aryl halides. Science 345, 437–440 (2014).

Zuo, Z. et al. Enantioselective decarboxylative arylation of α-amino acids via the merger of photoredox and nickel catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 1832–1835 (2016).

Luo, J. & Zhang, J. Donor–acceptor fluorophores for visible-light-promoted organic synthesis: photoredox/Ni dual catalytic C(sp3)–C(sp2) cross-coupling. ACS Catal. 6, 873–877 (2016).

Kullmer, C. N. P. et al. Accelerating reaction generality and mechanistic insight through additive mapping. Science 376, 532–539 (2022).

Palkowitz, M. D. et al. Overcoming limitations in decarboxylative arylation via Ag–Ni electrocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17709–17720 (2022).

Xie, K. A. et al. A unified method for oxidative and reductive decarboxylative arylation with orange light-driven Ir/Ni metallaphotoredox catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 25780–25787 (2024).

Nsouli, R. et al. Decarboxylative cross-coupling enabled by Fe and Ni metallaphotoredox catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 29551–29559 (2024).

Fier, P. S. & Hartwig, J. F. Copper-mediated difluoromethylation of aryl and vinyl iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 5524–5527 (2012).

Prakash, G. K. S. et al. Copper-mediated difluoromethylation of (hetero)aryl iodides and β-styryl halides with tributyl(difluoromethyl)stannane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 12090–12094 (2012).

Gu, Y., Leng, X. & Shen, Q. Cooperative dual palladium/silver catalyst for direct difluoromethylation of aryl bromides and iodides. Nat. Commun. 5, 5405 (2014).

Xu, L. & Vicic, D. A. Direct difluoromethylation of aryl halides via base metal catalysis at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2536–2539 (2016).

Lu, C., Gu, Y., Wu, J., Gu, Y. & Shen, Q. Palladium-catalyzed difluoromethylation of heteroaryl chlorides, bromides and iodides. Chem. Sci. 8, 4848–4852 (2017).

Bacauanu, V. et al. Metallaphotoredox difluoromethylation of aryl bromides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 12543–12548 (2018).

Xu, C. et al. Difluoromethylation of (hetero)aryl chlorides with chlorodifluoromethane catalyzed by nickel. Nat. Commun. 9, 1170 (2018).

Fu, X.-P. et al. Controllable catalytic difluorocarbene transfer enables access to diversified fluoroalkylated arenes. Nat. Chem. 11, 948–956 (2019).

Zou, Z. et al. Electrochemical-promoted nickel-catalyzed oxidative fluoroalkylation of aryl iodides. Org. Lett. 23, 8252–8256 (2021).

Du, W. et al. Switching from 2-pyridination to difluoromethylation: ligand-enabled nickel-catalyzed reductive difluoromethylation of aryl iodides with difluoromethyl 2-pyridyl sulfone. Sci. China Chem. 66, 2785–2790 (2023).

Chi, B. K. et al. Sulfone electrophiles in cross-electrophile coupling: nickel-catalyzed difluoromethylation of aryl bromides. ACS Catal. 14, 11087–11100 (2024).

Lamb, M. C. et al. Electrophotocatalysis for organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 124, 12264–12304 (2024).

Huang, H., Steiniger, K. A. & Lambert, T. H. Electrophotocatalysis: combining light and electricity to catalyze reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 12567–12583 (2022).

Barham, J. P. & König, B. Synthetic photoelectrochemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 11732–11747 (2020).

Wu, S., Kaur, J., Karl, T. A., Tian, X. & Barham, J. P. Synthetic molecular photoelectrochemistry: new frontiers in synthetic applications, mechanistic insights and scalability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202107811 (2022).

Liu, J., Lu, L., Wood, D. & Lin, S. New redox strategies in organic synthesis by means of electrochemistry and photochemistry. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 1317–1340 (2020).

Xiong, P. & Xu, H.-C. Molecular photoelectrocatalysis for radical reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 58, 299–311 (2025).

Huang, C., Xiong, P., Lai, X.-L. & Xu, H.-C. Photoelectrochemical asymmetric catalysis. Nat. Catal. 7, 1250–1254 (2024).

Cai, C.-Y. et al. Photoelectrochemical asymmetric catalysis enables site- and enantioselective cyanation of benzylic C–H bonds. Nat. Catal. 5, 943–951 (2022).

Fan, W. et al. Electrophotocatalytic decoupled radical relay enables highly efficient and enantioselective benzylic C–H functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21674–21682 (2022).

Xu, P., Chen, P.-Y. & Xu, H.-C. Scalable photoelectrochemical dehydrogenative cross-coupling of heteroarenes with aliphatic C−H bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 14275–14280 (2020).

Capaldo, L., Quadri, L. L., Merli, D. & Ravelli, D. Photoelectrochemical cross-dehydrogenative coupling of benzothiazoles with strong aliphatic C–H bonds. Chem. Commun. 57, 4424–4427 (2021).

Tan, Z., He, X., Xu, K. & Zeng, C. Electrophotocatalytic C−H functionalization of N-heteroarenes with unactivated alkanes under external oxidant-free conditions. ChemSusChem 15, e202102360 (2022).

Wan, Q., Wu, X.-D., Hou, Z.-W., Ma, Y. & Wang, L. Organophotoelectrocatalytic C(sp2)–H alkylation of heteroarenes with unactivated C(sp3)–H compounds. Chem. Commun. 60, 5502–5505 (2024).

Zou, L., Xiang, S., Sun, R. & Lu, Q. Selective C(sp3)–H arylation/alkylation of alkanes enabled by paired electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 14, 7992 (2023).

Zou, L., Zheng, X., Yi, X. & Lu, Q. Asymmetric paired oxidative and reductive catalysis enables enantioselective alkylarylation of olefins with C(sp3)−H bonds. Nat. Commun. 15, 7826 (2024).

Cao, Y., Huang, C. & Lu, Q. Photoelectrochemically driven iron-catalysed C(sp3)−H borylation of alkanes. Nat. Synth. 3, 537–544 (2024).

Lai, X.-L., Shu, X.-M., Song, J. & Xu, H.-C. Electrophotocatalytic decarboxylative C−H functionalization of heteroarenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 10626–10632 (2020).

Niu, K. et al. Photoelectrochemical decarboxylative C–H alkylation of quinoxalin-2(1H)-ones. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 16820–16828 (2021).

Wang, Y., Li, L. & Fu, N. Electrophotochemical decarboxylative azidation of aliphatic carboxylic acids. ACS Catal. 12, 10661–10667 (2022).

Yang, K., Wang, Y., Luo, S. & Fu, N. Electrophotochemical metal-catalyzed enantioselective decarboxylative cyanation. Chem. Eur. J. 29, e202203962 (2023).

Lai, X.-L., Chen, M., Wang, Y., Song, J. & Xu, H.-C. Photoelectrochemical asymmetric catalysis enables direct and enantioselective decarboxylative cyanation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 20201–20206 (2022).

Yuan, Y., Yang, J. & Zhang, J. Cu-catalyzed enantioselective decarboxylative cyanation via the synergistic merger of photocatalysis and electrochemistry. Chem. Sci. 14, 705–710 (2023).

Campbell, B. M. et al. Electrophotocatalytic perfluoroalkylation by LMCT excitation of Ag(II) perfluoroalkyl carboxylates. Science 383, 279–284 (2024).

Motornov, V. et al. Photoelectrochemical iron(III) catalysis for late-stage C–H fluoroalkylations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202504143 (2025).

Li, L., Yao, Y. & Fu, N. Trinity of electrochemistry, photochemistry, and transition metal catalysis. Chem. Catal. 4, 100898 (2024).

Zhang, R., Li, L., Zhou, K. & Fu, N. Radical-based convergent paired electrolysis. Chem. Eur. J. 29, e202301034 (2023).

Li, L. & Fu, N. Taming challenging radical-based convergent paired electrolysis with dual-transition-metal catalysis. Synlett 34, 1549–1553 (2023).

Yang, K., Lu, J., Li, L., Luo, S. & Fu, N. Electrophotochemical metal-catalyzed decarboxylative coupling of aliphatic carboxylic acids. Chem. Eur. J. 28, e202202370 (2022).

Lu, J., Yao, Y., Li, L. & Fu, N. Dual transition metal electrocatalysis: direct decarboxylative alkenylation of aliphatic carboxylic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 26774–26782 (2023).

Wu, Y., Wang, X., Wang, Z. & Chen, C. Redox-neutral decarboxylative coupling of fluoroalkyl carboxylic acids via dual metal photoelectrocatalysis. Chem. Sci. 15, 18497–18503 (2024).

Li, W., Zhang, R., Zhou, N., Lu, J. & Fu, N. Dual transition metal electrocatalysis enables selective C(sp3)–C(sp3) bond cleavage and arylation of cyclic alcohols. Chem. Commun. 60, 11714–11717 (2024).

Zou, L. et al. Photoelectrochemical Fe/Ni cocatalyzed C−C functionalization of alcohols. Nat. Commun. 15, 5245 (2024).

Liu, Z.-R. et al. Synergistic use of photocatalysis and convergent paired electrolysis for nickel-catalyzed arylation of cyclic alcohols. Sci. Bull. 69, 1866–1874 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22471276, N.F. and 22071252, N.F.) and the Chinese Academy of Sciences for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N. F. conceived and directed the project. N. Z performed the experiments and developed the reactions. M. C. helped collecting some experimental data. N. F. wrote the manuscript. N. Z and M. C. prepared the supplementary information and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mingyou Hu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, N., Chai, M. & Fu, N. Dual transition metal electrocatalysis for difluoromethylation of Aryl halides using potassium difluoroacetate. Nat Commun 16, 10734 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65763-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65763-3