Abstract

RAS proteins control cell proliferation and activating mutations are collectively the most frequent oncogenic event observed in cancer patients, justifying investments into multiple drug discovery efforts. While RAS-directed therapeutic agents targeting either the inactive GDP-bound or the active GTP-bound state have entered the clinic, invariably resistance is observed. Mutations at drug binding sites represent a common resistance mechanism indicating the need to discover new targetable pockets in RAS. Such efforts are hindered by the small globular size of the protein, for long considered undruggable. Here we perform macrocyclic peptides mRNA and nanobody yeast display screens and discover a targetable ligand-induced pocket in RAS. In vitro and cellular experiments with the KM12 and KM12-AM nanobodies show RAS inhibition via displacement of cRAF, by affecting their protein-protein interaction via the less studied cRAF CRD domain. Further, we provide orthogonal functional validation for the discovered binding pocket via mutagenesis experiments. Notably, the discovered RAS-targeting approach enables simultaneous targeting of both GTP-bound active and GDP-bound inactive states and leaves the SwII pocket unaltered, opening possibilities of combinatorial approaches with clinically approved SwII pocket inhibitors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amongst the well described genetic alterations observed in cancers, RAS genes and KRAS particularly are amongst the most frequently mutated1,2 within the three most deadly cancer types3. RAS proteins are involved in essential cellular cues such as survival and proliferation, and oncogenic events at RAS loci are critically required for initiation and maintenance of tumorigenic phenotypes, making RAS proteins high value targets in oncology4,5.

Despite undisputed clinical benefits observed in patients treated with experimental and approved covalent KRASG12C selective inhibitors6,7,8, multiple questions remain for long-term and sustained efficacy against KRAS mutant tumors. Current inhibitors target and sequester KRAS via the so-called Switch II (SwII) pocket when in the inactive form, hence relying on KRAS’ intrinsic hydrolytic activity to cycle back from the active, GTP-loaded state, in which it mostly resides in oncogenic settings9,10.

As observed for RAF or MEK inhibitors, KRAS and other MAPK pathway addicted tumors will try as much as possible to escape KRAS inhibitor treatment to preserve their growth and survival advantage11,12. KRASG12C SwII pocket inhibitors also suffer, as many other targeted therapies against the MAPK pathway components, from mutations, amongst other resistance mechanisms, affecting the compound binding mode, as proven from biopsies as well as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) genetic analyses from patients, causing relapse from treatment after initial tumor shrinkage and disease control13,14,15,16.

Being able to inhibit KRAS with modalities orthogonal from SwII pocket binders could, in principle, provide the basis for treatment alternatives upon resistance emergence, highlighting the importance to discover other ligandable pockets. Together with others16, WarpDrive Bio17 and Revolution Medicine18,19,20 have harnessed the conformational plasticity of protein chaperones to identify small molecules acting as molecular glue between Cyclophilin A and active, GTP-loaded RAS proteins, precluding effector recruitment by steric hindrance, leading to strong antiproliferative and antitumor effects against RAS addicted models. The addition of reactive warheads has further extended the potential of these molecular glues toward selectivity for KRAS oncogenic proteins such as KRASG12C or KRASG12D. These molecular entities are currently being tested clinically, with efficacy already documented for the pan-RAS asset RMC-623621.

RAS proteins are globular GTPases requiring GDP/GTP co-factor nucleotide binding as a basis for defining its functional states. Inhibiting RAS through nucleotide competition is highly challenging due the picomolar affinity and millimolar concentrations of GDP and GTP. Described by NMR studies first22, and more recently by using a cysteine-tethering approach23, the discovery of the SwII pocket allowed an unprecedented selective and covalent drugging approach for KRASG12C, and more recently for KRASG12D 24. By extension, a systematic tethering approach across the complete RAS coding sequence might be informative of distinct pockets, but introduction of cysteine residues is unlikely to be tolerated at each residue.

In this work, we thought to interrogate RAS proteins ligandability using libraries of cyclic peptides and of small biologic (nanobodies) to identify high affinity binders capable of unveiling induced-fit conformations, opening unprecedented drug discovery opportunities on this high value oncology target.

Results

Discovery of KM12, a distinct VHH with affinity to RAS

To probe RAS proteins for alternative druggable pockets we used a two-pronged approach taking advantage of mRNA25 and yeast26 display technologies using large and diverse libraries encoding either macrocyclic peptides and nanobody (VHHs) libraries, respectively (Fig. 1A) against a panoply of RAS proteins, representative of oncogenic mutations prevalence in human cancer (KRASG12D, KRASG12V and NRASQ61R) and of RAS nucleotide states (inactive GDP-loaded KRASG12D and KRASG12V, and active GMPPnP- (KRASG12D)/GTP- (NRASQ61R) loaded states (Supplementary Fig. 1a and Supplementary Methods).

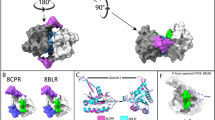

A Schematic representation of the display technologies applied to RAS proteins, for identification of RAS-selective macrocyclic peptides and nanobodies. Illustration created using BioRender (Maira, M., 2025): https://BioRender.com/lk2zlor. B Illustration of the binding sites of the three macrocyclic peptides MPB1, MPB2 and MPB3 identified in the mRNA display screens and obtained upon co-crystallization studies either with GDP-loaded KRASG12D (MPB1, PDB code 9GLU) or GTP-loaded NRASQ61R (MPB2, PDB code 9GLW; MPB3, PDB code 9GLX). C Illustration of the binding site for the KM12-AM nanobody, identified from a yeast display screen using a lama naive library, and solved upon co-crystallization studies with GMPPnP-loaded KRASG12D (PDB code 9GLZ). The “back-pocket” induced by KM12-AM binding is further emphasized in the included inlets, when omitting the nanobody from the complex structure (inlet 1) in comparison to the same region of KRAS in the apo form when not bound to KM12-AM present in the crystal (inlet 2, PDB code 5USJ). The lower inlet (inlet 3) shows an overlay of both structures as ribbon diagrams (KM12-AM and PDB code 5USJ structures shown in gray and orange, respectively) with a semitransparent surface of inlet 1. The side chains of Tyr157 and Lys42 are shown as stick model.

Overall, the mRNA display campaigns utilizing Flexizyme-based technology reprogrammed codon tables to generate cyclic peptides (Supplementary Table 1) led to the successful identification of three different types of macrocyclic peptides binders, MPB1, MPB2 and MPB3 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). These peptides were therefore profiled by SPR for affinity determination against RAS proteins (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1c) and to X-Ray crystallography studies to determine their binding modes to RAS (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1g). MPB1 preferentially binds GDP-loaded KRAS within the well-described SwII pocket and MPB2 active KRAS or NRAS, at the region corresponding to the effector binding domain (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, MPB3 was found to bind NRAS, but not H- and K-RAS, at a distal site from MPB2, encompassing α4, β5 and α5 RAS motifs, reminiscent to the binding site of the K/H-RAS selective NS1 monobody27 and potentially suggestive of a distinct protein-protein interface (PPI) surface. However, while being confirmed as differentiated RAS-binders to common SwII interactors, both MBP-2 and −3 binding modes were deemed as challenging for potential identification of low molecular weights therapeutics, as their affinity to RAS relies mostly on the interaction with large and flat surfaces rather than well-defined ligandable pockets.

Regarding the second screening approach, a total of three panning rounds against KRASG12V were performed by yeast display upon transformation of the constructed naive VHH library representing 2 × 107 unique sequences (Supplementary Fig. 2a), from which 12 clones (KM1 to KM12) were picked and further characterized. Selective binding to KRASG12V versus the unrelated control protein ARNT was validated by FACS (Supplementary Fig. 2b, f). Sequencing of their corresponding cDNAs revealed surprisingly high diversity within the CDR3 motifs (Supplementary Fig. 2c). From these 12 candidates, 6 were selected based on their FACS binding profile and further characterized. ELISA assays using VHH-huFc fusion from transfected HEK293 cell supernatants, demonstrated specific and similar binding capacity toward recombinant and biotinylated KRASWT, KRASG12D and KRASG12V proteins for at least 5 clones (KM1, KM4, KM5, KM9 and KM12) that could be produced at sufficient titers (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e), suggesting that the nucleotide CDR3 diversity does not translate into distinct biological profiles. Extended SPR profiling using purified recombinant KM12 further confirmed the lack of selectivity across RAS proteins with affinity (KD) ranging from 190 nM (GDP-loaded KRASWT) to 2 μM (GTP-loaded NRASQ61R) and qualifies KM12 as a pan-RAS binder (Table 1).

To see if we could improve our tool, we first generated and screened a KM12-based cDNA error-prone PCR library by yeast display to identify higher affinity RAS VHHs binders. Four clones (KM108, KM109, KM110 and KM111) with enhanced FACS binding profile compared to KM12 were identified (Supplementary Figs. 2f, 3a, b). Further profiling of KM110 (called KM12-AM thereafter) by SPR and ITC confirmed an at least 20-fold increase in affinity with KD’s ranging from 7 to 22 nM across the panel of RAS proteins tested (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 3d, e), in line with the pan-RAS binding profile already observed for KM12. As for the 3 other clones, KM12-AM cDNA contains the same Tyr 102 and Tyr 104 to Phe substitutions in CDR3, likely to be the main drivers of the improved affinity toward KM12 (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Interestingly, X-Ray crystallographic studies (Supplementary Table 3 Supplementary Fig. 1g) revealed a binding mode distinct from MPB1, MPB2 and MPB3 (Supplementary Figs. 1d, 3c), unravelling a large cryptic pocket (referred thereafter as the RAS back-pocket) induced by the binding of CDR3, with an important role for Phe102 and Phe104 in mediating critical contacts resulting in cavity “opening”. KM12-AM binding opens the RAS back-pocket by reorganizing residues Tyr157 and Lys42, which adopt different conformations, and shifting the interconnecting switch region composed of β-strands 2 and 3, including Val44 and Ile46, by about 1.5 Å. (Fig. 1C). These conformational changes in Ras result in an exposure of a hydrophobic pocket lined up by the side chains of Ras residues Leu23, Ile24, Val44, Ile46, Phe156 and Tyr157 which is occupied by residues Phe102 and Phe104 of the CDR3 of KM12-AM. In addition to these hydrophobic interactions at the core of the Ras back-pocket, the backbone amide groups of Ras residues Val45 and Asp47 of β-strand 2, form the beginning of an extended β-sheet with the backbone amide groups of Asn101 and Tyr103, immediately before and in-between the two critical Phe residues 102 and 104 of KM12-AM. An additional charged interaction is formed between the Ras side chain Lys42 and the side chain of Glu107 of KM12-AM. (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

KM12-AM influences RAS function in vitro without interfering with SwII pocket occupancy

These interesting findings have prompted us to investigate further the importance of the KM12-AM interacting region by interrogating RAS interactions and functions. The CRD domain previously thought to be mostly important for Raf recruitment to the plasma membrane upon RAS activation28, does also play, together with the Ras Binding Domain (RBD) an important role in RAF recruitment and activation by RAS29,30. SPR studies confirmed that whereas the CRD domain alone has, in the conditions tested, no affinity to KRASG12D, its presence does positively influence RAFRBD binding (KD: 16 nM vs 130 nM, Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6b). Interestingly, KM12 and CRD binding sites on RAS do superimpose (Fig. 2A). To assess if indeed KM12-AM and cRAF compete for binding to RAS, we developed and used a TR-FRET assay between KRASG12D and KM12-AM (see Methods for details). The TR-FRET signal could essentially be fully inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by cRAFRBD-CRD and cRAFCRD (low affinity for cRAFCRD did allow for testing at saturating concentration), but not by cRAFRBD for which only a partial displacement was observed (Fig. 2B).

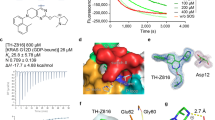

A Overlay and overlap of KM12-AM (PDB code 9GLZ) and cRAF1RBD-CRD (PDB code 6QUU) binding modes on RAS (left panel) and cRAF constructs used in this study (right panel). B cRAF proteins mentioned in (A) were tested in the GMPPnP loaded KRASG12D/KM12-AM TR-FRET assay and potential competition determined by quantification of IC50 (concentration needed for 50% maximal inhibition achieved with the respective proteins tested) and Ainf (maximum amplitude of the effect) values, as described in Methods. While CRD-containing constructs appear to result in (close to) complete competition with binding of KM12-AM, RBD alone results in only partial displacement (~50%). The assay is validated by titration of untagged KM12-AM or GMPPnP-loaded KRASG12D that both fully displace with IC50 (Ki) in range with their affinity as measured by SPR (see Tables 1 and 2). TR-FRET curves, Ki and Ainf values shown (n = 2 biological independent replicates) are derived from one representative experiment. This experiment was repeated at least two times with similar results. Source Data is provided as a source Data file. C A-B-A SPR experiment studies using MRTX1133 (right panels) or not (DMSO, left panels) as a switch II pocket binder during A-step, for KD determination of either cRafRBD (by steady-state affinity measurement, top panels) or KM12 (by kinetic affinity measurement, bottom panels) added in B-Step, on immobilized GMPPnP-loaded KRASG12D, as described in Methods. For steady-state affinity measurements, insets representing the corresponding Req versus concentration curves have been incorporated. For kinetic affinity measurements, sensorgrams are reported as overlay of fitted (in black for each concentration) and experimental (one color per concentration) curves. KD, Rmax and Chi2 values derived from one representative experiment are reported on the right side of each panel.

RAS proteins cycle between inactive and active states thanks to their ability to exchange GDP by GTP, a reaction regulated by SOS1 and SOS2 Guanine Exchange Factors (GEFs). The GDP to GTP intrinsic rate of exchange was measured in vitro and found to be reduced (with an IC50 of 26 or 28 nM, n = 2) when KM12-AM is co-incubated (Supplementary Fig. 4a), suggesting that biochemically, interaction to RAS at the back-pocket location can impair RAS functions by at least two different mechanisms of action, one for both active and inactive states.

Finally, to check whether binding at the back-pocket might influence SwII pocket binders, A - B - A SPR studies were performed with MRTX1133, a highly optimized potent and selective KRASG12D reversible inhibitor31,32. As expected, the presence of MRTX1133 prevented cRAFRBD binding, demonstrating that MRTX1133 is readily bound to GTP-loaded KRASG12D leading to Switch regions allosteric changes precluding cRAFRBD (Fig. 2C) or cRAFRBD-CRD (Supplementary Fig. 4b) binding. However, the presence of MRTX113 did not alter KM12 (Fig. 2C) or KM12-AM binding (Supplementary Fig. 4b) to KRASG12D.

KM12-AM inhibits MAPK signaling selectively in cells

To check whether KM12-AM would also bind RAS in cells, KRASWT HEK293 cells stably expressing LgBit-KRASG12D fusions6 were transfected with expression vectors encoding HA-tagged and stabilized (Ser50 mutated to Ala) of either KM12-AM (referred as HA-KM12*) or KM12-AM-AA (referred as HA-KM12*-AA), a mutant variant in which both critical Phe102 and Phe104 are replaced by Ala residues. Anti-HA immuno-precipitation studies did reveal binding of both endogenous KRASWT and exogenously expressed LgBit-KRASG12D for KM12-AM or for the NS1 monobody positive control27, but not for KM12-AM-AA or for the unrelated Myc-GFP-Nanoluciferase (Myc-GFP-Nluc) fusion protein (Fig. 3A), confirming in cells, specific and KRAS status agnostic RAS binding.

A HEK293 cells stably expressing LgBit-KRASG12D were transiently transfected with expression vectors containing either with the cDNAs of the mentioned proteins or not (mock control). Cells were then lysed, cell extracts used for anti-HA co-immuno-precipitations and bound RAS proteins revealed by western blotting (anti-HA Pull-down panels), as described in Methods. Straight western blots (Input panels) with the same cell extracts were also performed to estimate expression levels across conditions. Both GFP-NLuc and HA-Myc-GFP-NLuc constructs are Nanoluciferase fusions used as unrelated controls, that can be revealed with anti-LgBit antibodies. a and b labels refer to endogenous RASWT and LgBit-KRASG12D exogenous proteins, respectively. This experiment has been repeated at least three times with similar results. B LgBit-KRASG12V and SmBit-cRAF knock-in engineered PATU8988 cells were transiently transfected or not (mock control) with expression vectors encoding either KM12-AM*, its binding deficient mutant (KM12-AM*-AA) or with the NS1 monobody. Cells were then either incubated with NanoGlo LiveTM substrate, and bioluminescence determined (left panel) or lyzed and analyzed by straight western blots to estimate expression levels across conditions (right panel), as described in methods. Bioluminescence data are represented as mean values ± SD of n = 6 biological independent replicates. p-values were determined using two-tailed t-test. This experiment has been repeated three times with similar results. C HCT116 cells were transiently transfected or not (mock control) with expression vectors encoding either with GFP alone, GFP-fused KM12-AM* or its binding deficient mutant KM12-AM*-AA. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, nuclei stained with Hoechst and then analyzed by confocal microcopy High Content Imaging using anti-pERK antibodies to reveal nuclei (blue fluorescence) and pERK levels (red fluorescence) in cells expressing GFP or GFP-fused KM12-AM*/KM12-AM*-AA express (green fluorescence) or not as described in Methods. Representative examples are shown in the left panel and quantification of multiple fields is shown in the right panel. Quantification data are presented as violin plot of the distribution of the log value of pERK intensity. Dots represent scoring for individual cells, boxplots represent median and first and third quartiles, and whiskers extend to 95th percentile, statistical significance was calculated using welch-corrected T-test. (Control n = 3745, KM12-AM*-AA n = 5582, KM12-AM* n = 582). This experiment has been repeated two times with similar results. For (A–C), Source Data are provided as a source Data file.

Patu8988T cells engineered to stably express endogenous levels of SmBit-KRASG12V and LgBiT-cRAF proteins is a mechanistic system in which the emitted bioluminescence from the reconstituted nanoluciferase reflects endogenous RAS/cRAF interaction33. In these settings, expression of KM12*-AM but not KM12*-AM-AA significantly impaired bioluminescence output, suggestive of active RAS/RAF complex disruption in cells (Fig. 3B), To further demonstrate RAS functions perturbation, effects on pERK levels upon KM12-AM expression were determined. Western-blotting studies upon transfection of KM12*-AM in HEK293 cells did result in reduction of the pERK levels (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Moreover, immunofluorescence by confocal microscopy in transfected HCT116 cells (KRASG13D) further demonstrated that pERK1/2 levels (red staining) were strongly modulated in KM12*-AM (green staining) expressing cells, but not in mock-transfected, control cells. As expected, transfection of KM12*-AM-AA lead to little effects on pERK levels (Fig. 3C). Similar observations were made in KRASG12V PATU8988T cells (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Discrete mutagenesis perturbations within the back-pocket alter RAS oncogenic properties

As nanobodies cannot easily be used against intracellular targets such as RAS, to further demonstrate that RAS back-pocket targeting could lead to RAS inhibition, we decided to first investigate the relevance of residues important for RAF recruitment within this pocket by testing selected mutations in functional rescue studies. RAS residues Leu23 (mutated to Glu), Val44 (mutated to Trp) and Val45 (mutated to Asp or Glu) were selected based on their described interaction with cRAF CRD domain (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 1d). All these KRASG12D mutant proteins were first characterized for their ability to interact, in vitro, with cRAF-CR1 constructs (cRAFRBD-CRD, cRAFRBD, cRAFCRD). KD determination by SPR revealed that all mutations had little impact to cRAFRBD binding, but effects were more severe for cRAFRBD-CRD, as expected, with 4- to 6-fold-decrease in affinity (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6b). Of note, KRASG12D/L23E and KRASG12D/V44W proteins produced SPR sensorgrams characterized by lower binding efficiencies, likely reflective of their reduced thermal stability as assessed by Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF), indicative of potential partial misfolding (Supplementary Fig. 6a).

A Representation of the KRAS/KM12-AM structure highlighting the critical back-pocket residues (left panel) that were mutated to generate the RAS back-pocket mutant constructs used in (B) and Table 2. B VP16 fusions of the KRASG12D constructs described in (A) and Gal4 fusions of the cRAF constructs described in Fig. 2A were transfected in HEK293 cells together with a Gal4-Luciferase reporter vector to score for RAS/RAF interaction in mammalian duo hybrid format (left panel). Cells were then washed, incubated with NanoGlo LiveTM substrate, and Bioluminescence representative of RAS/RAS interaction determined (right panel), as described in Methods. Bioluminescence data are represented as mean values ± SD of n = 3 biological independent replicates. Illustration on the left created using BioRender Maira, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ftqjwng. Source Data are provided as a source datafile.

To check whether these effects hold true in cells, the same RAS constructs were tested in a mammalian duo-hybrid Gal4-controled Luciferase reporter gene (M2H) assay, as C-terminal fusions to VP16 transactivation domain, together with the same cRaf CR1 motif as fusion to the yeast Gal4 DNA binding domain (Fig. 4B, left panel). None of the individual components produced significant bioluminescence, and Gal4 N- or C-terminal positioning had no statistical influence (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d), suggesting that the activity of the reporter reflects RAS/RAF interactions in cells. Most notably, and in agreement with the SPR data, cRAFRBD was found to be 10-fold less efficient than cRAFRBD-CRD in interacting with KRASG12D and interacted similarly amongst all KRASG12D back-pocket mutant constructs tested. However, all back-pocket mutants did reduce to different extent the interaction with cRAFRBD-CRD, with KRASG12D/V45D and KRASG12D/V45E producing almost complete abolition of the binding (Fig. 4B, right panel) while not affecting KRASG12D folding in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 6a, right panel), hence suited to interrogate importance for KRAS signaling and dependency in KRAS mutant cancer cells.

For that purpose, we first generated homozygote KRASG12D SW1990 cells stably expressing inducible KRAS selective shRNAs. In this cell line, constitutive and stable expression of N-terminally Flag-tagged KRASG12D (FKG12D) lead to strong increase in pMEK and pERK levels, even when endogenous KRAS expression was silenced upon exposure to doxycycline. However, at similar expression levels, the FKG12D/V45D construct was incapable of producing substantial pMEK and pERK levels induction (Fig. 5A). Pull-down experiments using the same cell extracts suggested similar ability for both proteins to interact with cRAFRBD (Fig. 5B), demonstrating that the lack of pMEK levels cannot be accounted for general misfolding or protein aggregation. Effects obtained with the KRASG12D/V45D/L23E double mutant (FK KG12D/V45D/L23E) were comparable to the ones obtained with FKG12D/V45D suggesting that the Leu23 to Glu substitution does not add much to the effects. This is further substantiated when tested on its own, as KRASG12D/L23E only produced a partial rescue on pMEK and pERK levels, in good agreement with the M2H datasets. Altogether these datasets strongly suggest that the V45D back-pocket mutation impacts KRASG12D protein ability to recruit and/or activate efficiently Raf proteins which are the main upstream activators of MEK1 and MEK234.

A–D SW1990 cells stably engineered for doxycycline-inducible regulatable sh236 KRAS-specific shRNA expression and CMV-driven constitutive expression of the various flag-tagged KRASG12D alleles without (FKG12D) or with discrete mutations within the back-pocket (FKG12D/L23E or FKG12D/V45D or FKG12D/V45D/L23E) were treated for 72 h with doxycycline, lyzed and cell extracts further analyzed either by straight western-blot for the indicated read-outs (A and C), or by GST-cRaf-RBD pull-down to quantify GTP-loaded exogenously expressed KRAS binding (B, upper panel), or by anti-flag co-immuno-precipitation for endogenous proteins (D, upper panel). For (B, D), Input (lower panels) refer to straight western blots to assess expression levels across the conditions tested. E, F SW1990 cells stably engineered for doxycycline-inducible regulatable non targeting shNT control or sh236 KRAS-specific shRNA expression and Ubc-driven constitutive expression of the various flag-tagged KRASG12D and KRASG12D/V45D alleles were treated with doxycycline for either 14 days in a colony formation assay (left panel), or for 3 days only at which stage cells were lyzed and cell extracts analyzed by western-blot for the mentioned read-outs. Con.: control cells engineered from CMV-driven empty vector; SE: Short Exposure; LE: Long Exposure; a: endogenous KRASG12D; b: flag-tagged exogenously expressed KRAS. For (A–F), a minimum of three repeats has been performed with similar results; Source Data are provided as a Source Data file.

Straight western-blot analyses of all three RAF proteins revealed that in contrast to ARAF and cRAF, BRAF migration is significantly shifted, suggestive of potential post-translational modifications (Fig. 5C). Treatment with MRTX113 significantly impaired the migration shift, demonstrating a KRAS-dependent phenomenon. Furthermore, Lambda-phosphatase treatment of immunoprecipitated BRAF completely abolished this behavior, suggestive of modification by phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Finally, the well described Ser 259 and Ser 388 phosphorylation sites for cRAF were also checked, but no major differences could be detected (Supplementary Fig. 7b). We hence postulated that BRAF might be the main RAS partner, but anti-flag immune-precipitation studies (Fig. 5D) could not confirm that, as both endogenous cRAF and BRAF proteins could be readily recruited for FKG12D, in a KRAS-dependent manner. FKG12D/V45D however, displayed little ability to recruit either protein, suggesting that the main mechanism at play is the reduced ability of back-pocket mutants in recruiting Raf effectors.

Finally, expression of FKG12D/V45D was, upon exposure to doxycycline, unable to rescue endogenous KRASG12D silencing effects on colony formation, whereas FKG12D could (Fig. 5E, F and Supplementary Fig. 7c), confirming the importance of Raf recruitment through CRD domain interaction for KRAS oncogenic potential. These datasets therefore raise the possibility for an unprecedented therapeutic modality of intervention for KRAS addicted tumors and strongly suggest that small molecules that would have the ability to bind within this identified back-pocket would perturb RAF effector recruitment and KRAS oncogenic potential.

Discussion

Our approach to systematically probe RAS proteins plasticity and ligandability using stabilization with external binding partners has allowed the discovery of KM12, a RAS-specific nanobody with a unique binding mode. Amongst already described biologics, small-biologics, and DARPIns interacting with RAS35, KM12 is to our knowledge, the only asset contacting residues within the region interacting with the cRAFCRD domain, referred in this study as the backpocket. Biophysical and cellular characterization studies unambiguously demonstrated that KM12 (and KM12-AM) perturbs RAF/RAS interactions by principally impairing cRAF CRD- but not cRAF RBD-mediated interactions to RAS. Recently, Weng et al. applied an unbiased deep mutational scanning approach scoring for effects on RAS effector interactions, to map RAS proteins allosteric landscape36. Interestingly, the region encompassing the back-pocket did not score in these settings. The likely explanation for this might lie within the fact that cRAFRBD was used and not the complete CR1 (RBD-CRD) motif or full-length cRAF, further strengthening our data and proposed model. Molecular Dynamics simulation and FRET studies have also suggested an important role for this region in regulating RAS orientation at the plasma membrane37,38.

Strikingly, binding of KM12 to RAS unravels a unique pocket, by inducing important side chains movement of residues Tyr157, Lys 42, Ile46, Val44, and Val45 that would otherwise obstruct it. The ligandability of the back-pocket has been assessed by SiteMap (Schrodinger, 2023 − 4) and by visual inspection. The SiteMap score (Dscore) of 0.92 indicates good ligandability, with a good balance of hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity regions and a volume of 112 Å3, twice bigger than SwI/II Indole pocket but smaller than the SwII pocket (Supplementary Fig. 1f and Table 3). The pocket is not identified by SiteMap when considering a KRASG12D protein structure in complex with GMPPcP (PDB code 6QUU). This unique feature potentially unlocks an unprecedented therapeutic intervention for RAS mutant tumors. Rescue studies using mutations demonstrate the importance of key residues within the pocket for RAS oncogenic potential. Based on these data, one prediction would be that pharmacological intervention with low molecular weight compounds, yet to be identified, able to bind within the back-pocket might produce similar outputs. In principle, such a molecule could block RAS functions by multiple mechanisms, cumulating the effects on lowering GDP to GTP exchange on the GDP-loaded species, and impairing RAF proteins recruitment on the GTP-loaded species. This profile would be unique amongst known RAS inhibitors: SwII pocket binders are overall more effective by sequestering the inactive GDP-loaded form and Ras/Cyclophilin glues are uniquely active against the GTP-loaded form. Our data demonstrate that KM12 or KM12-AM is non-competitive to SwII pocket binding, suggesting that on-RAS double targeting with SwII pocket binders, already in the clinic, might be possible, potentially allowing for extremely efficient acute RAS inhibition, such as that observed for the Bcr-Abl inhibitors ABL001 (Asciminib/Scemblix) and Nilotinib for the treatment of CML39. Our strategy focused on optimizing KM12 toward affinity improvement towards pan-RAS conditions (i.e. not mutant-selective). Given the high homology at the back-pocket, it is unlikely, however, that such compounds could be optimized for paralog (e.g., pan-KRAS) or onco-allele (e.g., KRASG12D) selectivity. Our strategy was centered on enhancing KM12 affinity for RAS, potentially at the cost of mutant-RAS selectivity. Employing KRASWT as a primary target for the KM12-based error-prone PCR library screen might have potentially compromised the possibility, even if unlikely given the conditions used, of favoring the identification of mutant-RAS selective VHHs, which conceptually should result in maximizing tumor efficacy while minimizing target-related adverse events. Consequently, further yeast display investigations using differentiated and error-prone PCR libraries aiming at targeting different oncogenic RAS alleles are warranted.

Methods

Protein production and analytics

Biotinylated and non-biotinylated RAS and RAF proteins expression and purification

The codon-optimized cDNAs encoding human KRAS (1–169), NRAS (1–169), HRAS (1–169), cRAF-RBD (51–131), cRAF-RBD-CRD (51–188) and cRAF-CRD (135–188) fused to an amino-terminal cleavable poly-histidine tag and, for biotinylated proteins, a carboxy-terminal Avi tag, were synthetized and inserted in a pET-derived vector. Point mutations were then introduced by site-directed mutagenesis. Expression was performed overnight at 16 °C in E. coli BL21(DE3) strain transformed with the RAS expression vectors either with (for avi-tagged constructs) or without the BirA ligase, after induction with IPTG, in medium supplemented (for avi-tagged constructs) or not with 135 µM d-biotin (Sigma).

Cell pellets were resuspended in buffer A (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 2 mM TCEP, 10% glycerol, pH 8.0) supplemented with Turbonuclease (Merck) and cOmplete protease inhibitor tablets (Roche). The cells were lysed through a homogenizer (Avestin) at 800–1000 bar, and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 40 min. The lysate was loaded onto a HisTrap HP column (Cytiva). The resin was washed with buffer A and bound protein was eluted with a linear gradient to buffer B (buffer A supplemented with 200 mM imidazole).

Proteins without poly-histidine tag were obtained by proteolytic cleavage over night during dialysis against buffer A, either by TEV or HRV3C protease, recognizing the corresponding proteolytic cleavage site inserted between the poly-histidine tag and the protein sequence. The protein solution was re-loaded onto a HisTrap column and the flow through containing the target protein was collected. Finally, proteins with or without poly-histidine tag were loaded onto a Superdex 75 size exclusion column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated with SEC Buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2).

RAS proteins nucleotide loading

Nucleotide exchange was performed by incubating the RAS proteins during 1 h at room temperature with a 24-molar excess of nucleotide (GMPPnP from Jena Bioscience, GTP from Sigma or GDP from Sigma) in presence of 25 mM EDTA. The mixture buffer was then exchanged using a PD-10 column (Cytiva) against nucleotide loading buffer (40 mM Tris pH 8.0, 200 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 mM ZnCl2). A fresh 24-molar excess of nucleotide was again added. Ten units of Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase (New England Biolabs) were added to the samples containing GMPPnP. After 1 h incubation at 4 °C, MgCl2 was added to a concentration of 30 mM. After nucleotide exchange the RAS proteins were further purified over a Superdex 200 size exclusion column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated with final SEC buffer (20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM TCEP, pH 7.5). Nucleotide exchange was verified by ion-pairing chromatography40.

KM12, KM12-AM and KM12-AM* (S50A) VHHs production and purification

The cDNAs encoding KM12, KM12-AM or KM12-AM* (containing the stabilizing Ser50 to Ala mutation) VHHs, fused to PelB periplasmic signal at the amino-terminal end and TEV-cleavable poly-histidine tag at the carboxy-terminal end were inserted in a pET derived vector. In the case of biotinylated VHHs the carboxy-terminal end is tagged with avi-tag followed by poly-histidine tag. Expression was performed overnight at 18 °C in E. coli BL21(DE3) strain transformed with the expression vector, after induction with IPTG. Lysis was carried out by cold osmotic shock. The cell pellet was resuspended in hypertonic buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 20 % w/v sucrose) and incubated with slight agitation for 30 min. The suspension was centrifuged at 7200 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was put aside, and the cell pellet was resuspended in hypotonic buffer (5 mM Tris pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2). The suspension was incubated for 30 min. Following a centrifugation step at 7200 × g for 15 min, the supernatant was removed. Hypertonic and hypotonic fractions were pooled and NaCl concentration was adjusted to 150 mM. The solution was then passed through a 0.45 µm filter equipped with a glass fibre prefilter. The filtered solution was loaded onto a HisTrap HP column (Cytiva). The resin was washed with buffer A (50 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, pH 7.8) and bound protein was eluted with a linear gradient to buffer B (buffer A supplemented with 270 mM imidazole).

Constructs without His-tag were obtained by TEV protease cleavage during dialysis over night against buffer A supplemented with 0.5 mM TCEP and 0.1 mM EDTA. After addition of MgCl2 at 1 mM concentration the protein solution was loaded onto Ni Advance column and the flow through containing the target protein was collected. Both tagged and untagged proteins were finally purified over a Superdex 75 pg column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated with SEC buffer (20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, pH 7.4).

Biochemical and biophysical assays

GMPPnP-loaded KRASG12D/KM12-AM TR-FRET assay

His-tagged recombinant human GMPPnP-loaded KRASG12D (construct corresponding to amino acids 1–169) was incubated with europium-labeled anti-6X His antibody (Lance Eu W1024 anti-6xHis, Revvity) for 30 min. Following addition of protein serial dilutions prepared in assay buffer (50 mM Tris pH7, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 μM GMPPNP, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.005% Tween-20), the plate was incubated 30 min at room temperature. After pre-coupling with Cy5-Streptavidin (Amersham PA45001), KM12-AM was added to the assay plate and incubated for another 2 h at room temperature. Final assay concentrations are 10 nM GMPPnP-loaded His-KRASG12D, 2 nM anti-His-Europium, 5 nM KM12-AM-Avi, 1.25 nM Streptavidin-Cy5). Following incubation, plates were read in a Pherastar FSX (BMG Labtech) via TR-FRET dual wavelength detection (excitation at 337 nm, Europium emission at 620 nm, Cy5 emission at 665 nm). TR-FRET ratios (emission at 665 nm/emission at 620 nm) were normalized to percent of control (POC) relative to control wells without test compound (100%) and in absence of KRASG12D (0%). Dose-response curves are fit with a four-parameter nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism version 10.4.2.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) binding studies

SPR affinity studies were carried out at 25 °C either on a Biacore 8 K (Cytiva), or Biacore T200 (Cytiva) or ProteOn XPR36 (BioRad) device.

All SPR experiments performed on Biacore devices used streptavidin sensor chips. In these cases, 0.04 up to 0.5 μg/mL biotinylated RAS-Avi isoforms prepared in assay buffer, were immobilized on the sensor chip at a flow rate of 5 μL/min. When using Biacore T200 device, ligand immobilization was manually stopped when an appropriate response, based on analyte molecular weight, was reached. When using Biacore 8 K device, ligand immobilization was performed for 600 s and injections of 50 μM biotin solution for 60 s at 50 μL/min were performed to reduce unspecific binding. All SPR experiments performed on the ProteOn device used a neutravidin covalent immobilization strategy on GLM sensor chips. The sensor chip surface was first activated with a 20 mM EDC/5 mM NHS mixture prepared in water, for 6 min at 25 μL/min. 50 μg/mL neutravidin in 10 mM NaOAc pH5.5 was then immobilized on the activated chip for 6 min at 25 μL/min. The surface was then deactivated by the addition of 1 M Ethanolamine pH8 for 6 min at 25 μL/min. The biotinylated avi-tagged RAS proteins were then captured on the neutravidin-immobilized chips.

For all SPR studies, test items were prepared in the same running buffer (50 mM HEPES pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20, 10 μM nucleotide - GDP, GTP or GMPPnP - depending on the RAS protein nucleotide-state proteins to be assessed, with a maximal final DMSO concentration of 2% according to the analytes evaluated) and tested as multi cycle runs of 12- (for peptides) or 8- (for proteins) concentrations series when using Biacore devices, or 5-concencentrations series when using a ProteOn device, in a 1:2.5 serial dilution manner. Association and dissociation times were of 150 s and 150 s up to 800 s, respectively, with a flow rate of 30 μL/min and a data collection rate of 10 Hz.

SPR analyses (steady state or 1:1 binding model with global fitting parameters) were done with the software recommended by the device vendor (Biacore Insight Evaluation Software 4.0.8.20368 or ProteOn Manager Software for Biacore and ProteOn devices, respectively). DMSO solvent correction was applied when necessary and double-referencing method was used for the analysis.

SPR competition (A-B-A setup) experiments between SwII pocket binder and KM12-AM experiments were carried using the A-B-A feature of the Biacore 8 K. Experiments were run in the same running buffer as described above, containing 2% DMSO and GMPPnP as nucleotide. GMPPnP-loaded and biotinylated KRASG12D-avi prepared at 0.5 μg/mL in running buffer was immobilized for 600 s at 10 μL/min to reach 1500 RU. In “solution A”, the running buffer supplemented with DMSO or 50 nM MRTX1133 was floated onto the chip for 250 s at 30 μL/min flow rate. Then (step “B”), a 12-concentration range of the test items (cRAF constructs, KM12 or KM12-AM) dissolved in “solution A” was floated for 200 s. The system is put back in solution A for the dissociation phase. Data was analyzed for steady-state affinity or kinetic 1:1 binding when appropriate after double-referencing, in presence and absence of SwII pocket binder using Biacore evaluation software (Biacore Insight Evaluation Software 4.0.8.20368).

MPB1, MPB2, MPB3 and KM12-AM X-Ray co-crystallographic studies

For crystallization, KRAS and NRAS protein constructs included residues 1–169, lacking the C-terminal hypervariable region. Cys51, Cys80 and Cys118 were mutated to Ser, Leu and Ser, respectively. All crystallization trials were performed using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method at room temperature. Equal volumes (0.2 µl) of protein-peptide/nanobody solution and reservoir solution were mixed and equilibrated against 80 μL reservoir solution. Peptides were added to the protein solution using a 100 mM DMSO stock solution. Crystals grow typically within a few days.

Co-crystals of GDP-loaded KRASG12D in complex with MPB1 were obtained by mixing 0.2 μL protein-peptide solution containing 19.2 mg/ml GDP-loaded KRasG12D in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM MPB1 with 0.2 μL reservoir solution (25% PEG 3350, 0.1 mM Bis-Tris pH 5.5) and equilibrating against 80 μL reservoir solution.

Co-crystals of GTP-loaded NRasQ61R in complex with the peptides MPB2 or MPB3 were obtained by mixing 0.2 μL protein-peptide solution containing 20.5 mg/ml GTP-loaded NRASQ61R, 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 and either 8 mM MPB2 or 8 mM MPB3 with 0.2 μL reservoir solution (30% PEG 1000, 0.2 M Na2HPO4 for MPB2 and 20% PEG 4000, 0.2 M Lithium Acetate for MPB3) and equilibrating against 80 μL reservoir solution.

Co-crystals of GMPPnP-loaded KRASG12D in complex with the nanobody KM12-AM were obtained by mixing 0.2 μL protein-nanobody solution containing 24 mg/ml GMPPnP-loaded KRasG12D, 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, 5 mM MgCl2 and KM12-AM in a 1:1.15 stoichiometry of KRAS to KM12-AM with 0.2 μL reservoir solution (30% PEG 1000, 0.2 M LiNO3) and equilibrating against 80 μL reservoir solution.

For data collection, crystals were flash cooled in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected from single crystals at the Swiss Light Source, beamline X10SA equipped with a Pilatus Pixel detector for the KRAS and NRAS peptide complexes and beamline X06SA equipped with an Eiger Pixel detector for the KRAS nanobody complex. The diffraction data were processed and scaled with XDS/XSCALE41 and the autoPROC toolbox42. The structures were solved by molecular replacement with PHASER43 for the N/KRas-peptide complexes and MOLREP44 for the KRas-KM12-AM nanobody complex using the coordinates of internally solved KRAS and NRAS structures. The first internal KRas structure was solved using the PDB code 4LRW as search model and PDB code 5LZ0 was used as search model for the nanobody. The software programs COOT45 and BUSTER (https://www.globalphasing.com) were used for iterative rounds of model building and structure refinement. Images were generated using the program PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org). Omit electron density contoured maps for MPB1, MPB2, MPB4 and KM12-AM are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 1g.

mRNA-display technology for the identification of macrocyclic peptides

The coding region of the peptide library was designed as follows: After the constant T7- promoter and Shine Dalgarno motifs, the initiator 5’ initiator ATG codon was followed by 8–12 fully randomized positions comprising of NNT oligonucleotide mixtures. The NNT scheme codes for 15 natural amino acids except for Gln, Glu, Lys, Met and Trp which have an A/G or G at their 3rd codon position. The degenerate region was followed by a fixed TGG codon, a sequence for the defined spacer peptide (Gly-Gly-Gly-Gly-Ser-Ser) and finally an amber stop codon (TAG). To generate cyclic peptide, the initiation amino acid Met was exchanged for N-chloroacetyl L-Phe using the previously described Flexizyme technology46. Additionally, to allow for controlled cyclization through a Cys at the C-term of the degenerate region and to incorporate tryptophane (known as a key aa in protein-peptide interactions) at the randomized positions, the codons for Cys (TGT) and Trp (TGG) were exchanged. For elongator positions, all available natural amino acids were used. Applying this reprogrammed translation system to the mRNA template affords a 10–14 amino acid thioether macrocyclic peptide library with each peptide containing a C-terminal Gly-Ser linker47. Starting with an initial round containing >1012 unique cyclic peptides, K- or NRAS specific binders were enriched using the Avi-tagged soluble GDP-loaded KRASG12D and GTP-loaded NRASQ61R immobilized onto streptavidin conjugated magnetic beads. Non-specific binders were removed using the streptavidin conjugated magnetic beads only before incubation with beads presenting the target protein. The binding-stringency was increased in latter rounds through longer incubation times and prolonged washing steps. All selections rounds were submitted for NGS to analyze enriched peptides sequences and about ten different sequences with sufficient high enrichment were picked for chemical synthesis.

Yeast display technology for the identification of KRAS selective nanobodies

To display nanobodies on the yeast surface, we created an internal yeast display vector. The display cassette includes the Aga2 leader sequence, the nanobody sequence, the Aga2 anchor protein, and Myc and His tags, all under the control of a GAL1 promoter. The plasmid carries the tryptophan nutrition marker gene TRP1. Our internal S. cerevisiae yeast display strain NYD2011 is derived from BJ5465 (ATCC 208289). This strain was generated by integration of an AGA1 cassette with a geneticin resistance marker into the TRP1 locus. The tryptophan auxotrophy is stable and can be used for plasmid selection in addition to uracil marker.

Mammalian expression vectors generation

Mammalian-2-hybrid vectors

KRASG12D-NLS-v5, RBD-NLS-HA (cRAFRBD), CRD-NLS-HA (cRAFCRD) and RBD-CRD-NLS-HA (cRAFRBD-CRD) CDS were obtained by gene synthesis (Twist Biosciences) and cloned into custom lentiviral vectors under an EF1α promoter via golden-gate cloning. cRAFRBD-CRDm (containing the K179A mutation), KRASG12D, KRASG12D/L23E, KRASG12D/V44W, KRASG12D/V45D and KRASG12D/V45E were obtained by site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent QuickChange Lightning). Vectors were validated by Sanger Sequencing.

Nanobody constitutive expression vectors

cDNAs encoding KM12-AM-mEGFP-HA, KRAS KM12-AM*-mEGFP-HA (S50A) and HA-mEGFP-NS1 were cloned into a custom vector featuring the strong synthetic CAG promoter to drive high expression VHH levels.

Constitutive rescue allele expression vectors

cDNAs encoding the following proteins EGFP-T2A-Flag (labeled Con.), EGFP-T2A-FLAG-KRASG12D (labeled FKG12D), EGFP-T2A-FLAG-KRASG12D/V45D (labeled FKG12D/V45D), EGFP-T2A-FLAG-KRASG12D/L23E (labeled FKG12D/L23E) and EGFP-T2A-FLAG-KRASG12D/V45D/L23E (labeled FKG12D/V45D/L23E) were obtained by gene synthesis (GeneArt) within the Gateway compatible pENTR vector. LR reactions were then performed between these entry vectors and destination retroviral vectors containing either a CMV or an Ubc promoter. The resulting CMV promoter-containing expression vectors containing were called respectively pC-ET-FS, pC-ET-FKG12D, pC-ET-FKG12D/V45D, pC-ET-FKG12D/L23E, and pC-ET-FKG12D/V45D/L23E. The resulting Ubc promoter-containing expression vectors containing were called respectively pU-ET-FS, pU-ET-FKG12D, pU-ET-FKG12D/V45D, pU-ET-FKG12D/L23E, and pU-ET-FKG12D/V45D/L23E. Vectors were validated by Sanger sequencing and sequences are available on request.

Lentiviral inducible shRNA expression vectors

pLKO-Tet-ON lentiviral48 vectors containing either a non-targeting sequence (shNT: 5′ GGATAATGGTGATTGAGATGG 3′, pLKO-shNT) or a KRAS selective sequence (5′-GATACAGCTAATTCAGAATC-3’, pLKO-sh236) have already been described49.

Cell culture, cell-line generation and cell-based assays

PATU8988T-SmBit-KRASG12V/LgBiT-cRAF33 and HCT116 (ATCC #CCL-247) cells were cultured in DMEM and McCoy’s 5A respectively, supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2. HEK293A-SmBiT-cRAF-LgBiT/KRASG12D cells6 were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 + GlutaMax (Gibco, 61870) supplemented with 10% FBS (Corning, 35-015-CV), 1% penicillin–streptomycin (BioConcept, #4-01F00-H), 1 mM Sodium pyruvate (BioConcept, #5-60F00-H), 10 mM HEPES (BioConcept, #5-31F00-H). SW1990 (ATCC #CRL-2172) and all the engineered lines from the SW1990 parental cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media with Glutamax, supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM Sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

RAS/KM12-AM co-immunoprecipitation studies

Transfection was performed using Fugene HD reagent (Promega E2311) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After 24 h, the cells were harvested and lysed in an NP40/RIPA lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche #11836153001). Lysates were then incubated with Pierce Anti-HA Magnetic beads (Thermo Scientific #88836) at 4 °C for 1 h with gentle rotation. Following incubation, the beads were washed five times with IP washing buffer (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 1% NP40) and eluted with 0.1 M glycine buffer (pH 2.0) on a shaker for 10 min. The eluate was neutralized with 1 M Tris-buffer (pH 8.5). Immunoprecipitated (IP) and input samples were boiled at 96 °C with SDS and reducing agent for 10 min and analyzed by western blotting.

RAS/cRAF NanoBit Endobind assay

PATU8988T-SmBit-KRASG12V-LgBiT-cRAF cells33 were plated at a density of 10’000 cells per well in 100 µL of DMEM without phenol red and without antibiotics in a white 96-well plate with white bottom (Nunc, #136102). The plate was incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Plasmid DNA coding for the nanobodies or the monobody NS1 targeting KRAS was diluted to 250 µg/mL in sterile water. Transfection mixture was prepared by mixing 8 µL DNA with 6 µL of Dharmafect kb Transfection Reagent (Horizon, #T-2006-01) in 200 µL of Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium (Thermo Fisher, #31985062). The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20 min before adding 10 µL per well on top of the cells. EndoBind signal was determined 24 h post transfection.

pERK/GFP-KM12 and NS1 high content imaging studies

HCT116 and PATU8988T-SmBit-KRASG12V-LgBiT-cRAF cells were plated at a density of 7000 cells per well in 100 µL of media without antibiotics in a black 96-well cell carrier ultra-plate with clear bottom (PerkinElmer, #6055302). The plate was incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Plasmid DNA coding for the nanobodies or the monobody NS1 targeting KRAS was diluted to 250 µg/mL in sterile water. Transfection mixture was prepared by mixing 8 µL DNA with 6 µL of Dharmafect kb Transfection Reagent (Horizon, cat no. T-2006-01) in 200 µL of Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium (Thermo Fisher, #31985062). The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20 min before adding 10 µL per well on top of the cells. 24 h after transfection, cells have been fixed by adding 100 µL of 7.4% formaldehyde for 10 min followed by a 15 min permeabilization step with 0.5% Triton X-100. After washing the plates three times with PBS (with Ca/Mg), 100 µL Odyssey blocking buffer (Licor, cat no. 927-40000) was added and the plates were incubated for one hour at room temperature. Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary anti-pErk1/2 antibody (CST, #4370) diluted 1:300 in Odyssey blocking buffer. After some washing steps, the secondary anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 647 conjugate antibody (Invitrogen, #A-21245) diluted 1:1000 in Odyssey blocking buffer with 1 µg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Sigma, #B2261) has been added to the plates for one hour. GFP, Alexa647 and Hoechst signals have been captured and analyzed with the Phenix Opera high content imager (Perkin Elmer).

Mammalian 2 hybrid assay

HEK293A-M2H-Nluc cells were generated through lentiviral transduction using a custom vector containing 5× GAL4 motifs positioned before a minimal promoter and the open reading frame (ORF) of the NanoLuciferase gene. Cells were seeded at a density of 4000 cells/well in white transparent-bottom 96-well plates and transfected the next day with combinations of cRAF-GAL4 and KRAS G12D-VP16 constructs using X-tremeGENE 9 (Roche) at a ratio 1:3 (DNA:transfection reagent). After 72 h of transfection, the Nluc signal was measured by adding Nano-Glo reagent (Promega) and recorded using the Infinite M-plex (Tecan). HEK293A-M2H-Nluc cells were seeded at a density of 100,000 cells/well in a 6-well plates and transfected the next day with expression vectors for Nluc (cloned into a custom vector named pXP1510), HA-KM12-AM, HA-KM12-AM* (see above), and HA-NS1 or not (mock control) using X-tremeGENE 9 (Roche) at a ratio 1:3 (DNA:transfection reagent). After 72 h of transfection, cells were harvested for protein extraction and WB analysis.

Generation of shRNA inducible and constitutive KRAS rescue allele expression in SW1990

shNT and sh236 lentiviral particles were first produced by transfecting HEK293FT cells with the TransIT®−293 Transfection Reagent (Mirus) containing a mix of pVPRΔ8.71, pVSVg and pLKO-Tet-ON vectors. Viral particles were then harvested 72 h later, filtered and titrated. SW1990 cells were spinfected at 1300 rpm for 1h30 in medium containing 8 µg/ml polybrene. Medium was changed 16 h post-infection, and puromycin selection was started and maintained at 1 µg/ml to generate SW1990-shNT and SW1990-sh236 resistant pools. For the expression of the KRAS rescue alleles retroviral particles were first produced by transfecting HEKGP2-293 were transfected with the TransIT®−293 Transfection Reagent (Mirus), containing, pVSVG and the CMV- or Ubc-driven EGFP-T2A-Flag or EGFP-T2A-Flag-KRAS retroviral vectors (see above). Viral particles were harvested 72 h later, filtered and viral titers determined. SW1990 shNT and SW1990 KRAS sh236 cell lines were then spinfected at 1300 rpm for 1h30 in medium containing 8 µg/ml polybrene with the produced retroviral particles. Medium was changed 16 h post-infection, at which point neomycin selection was started and maintained at 400 µg/ml, to produce SW1990-shNT-based pools (named SNT-C-FS, SNT-C-FKG12D, SNT-C-FKG12D/V45D, SNT-C-FKG12D/L23E and SNT-C-FKG12D/V45D/L23E when using CMV promoter-driven expression and SNT-U-FS, SNT-U-FKG12D, SNT-U-FKG12D/V45D, SNT-U-FKG12D/L23E and SNT-U-FKG12D/V45D/L23E when using Ubc-promoter driven expression) and SW1990-sh236-based pools (named S236-C-FS, S236-C-FKG12D, S236-C-FKG12D/V45D, S236-C-FKG12D/L23E and S236-C-FKG12D/V45D/L23E when using CMV promoter-driven expression and S236-U-FS, S236-U-F-KG12D, S236-U-FKG12D/V45D, S236-U-FKG12D/L23E and S236-U-FKG12D/V45D/L23E when using Ubc-promoter driven expression). In all cases, NT- and sh236 KRAS knock-down induction was performed by adding 100 ng/mL of doxycyclin. For effects on downstream signaling, cells were lyzed 3 days post doxycycline addition (see below). For effects on colony formation, cells were seeded at a density 3000 cells/well of 6 well plate. 24 h after seeding, doxycyclin was added in the appropriate wells, and media was refreshed every 3 days for a total of 15 days. Cells were then washed with PBS and fixed using a solution of 20% Glutaraldehyde for 1 h and stained using a crystal violet solution for 30 min followed by 3 washes with water. Quantification was performed by adding 1 mL of 10% acetic acid (v/v) until all crystal violet has dissolved (10–15 min incubation generally), and photometric measurement at 590 nm.

Cell lysate preparation and immunoblotting

Cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were centrifuged for 20 min at 13,000 rpm to remove cellular debris, and the protein concentration was determined using Pierce BCA Protein assay. Samples were loaded onto a precast gel (4–12% Bis-Tris). Western blotting was done on Nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad 170-4156) membrane using PBS/Tween (0.1%) milk (5%) and using BioRad Trans Blot Turbo system. Blots were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and then treated with the corresponding secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Detection was performed using the WesternBright ECL kit (Advansta K-12045-D20) with a Fusion Fx device.

The following antibodies were used: ARAF (rabbit mAb clone D2P9P, CST #7580), BRAF (rabbit mAb clone D9T6S CST #14814S and clone E3T5C, CST #77622), cRAF (BD Transduction laboratories #610152), KRAS (clone 3B10-2F2, Abnova #H00003845-M01 and 12063-1-AP, Proteintech), KRASG12D (rabbit mAb clone D8H7, CST #14429), Ser259 phospho-cRAF (CST, #9421), Ser338 phospho-cRAF (Ser338) (clone 56A6, CST, #9427), Ser217/Ser221 phospho-MEK1/2 (rabbit mAb clone 41G9, CST #9154), Thr202/Tyr204) phospho-p44/42 ERK1/2 (rabbit mAb clone D13.14.4E, CST #4370), FLAG (Invitrogen, #MA1-91878-HRP), HA Tag (clone C29F4, CST #3724), β-actin (clone 8H10D10, CST #3700), Vinculin (Sigma, #V9131), and LgBit (Promega N7710A).

GST-cRAFRBD pull down assay

Cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed using lysis buffer from the kit: Ras activation assay biochem kit (Cytoskeleton, #BK008-S) and adding protease inhibitor cocktail. Lysates were centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 × g to remove cellular debris, and the protein concentration was determined using Pierce BCA Protein assay. An equal number of lysates for each sample were incubated with beads on a rotator for 1 h at 4 °C. Beads were collected and washed once with the washing buffer from the kit. The beads were collected and washed using wash buffer. Finally, the proteins were eluted in Laemmli sample buffer, boiled at 95 °C for 2 min and visualized by Western blotting.

Flagged KRAS/endogenous RAF plate co-immunoprecipitation studies

SW1990-shNT-CMV-FStop, SW1990-shNT-CMV-FKRASG12D and SW1990-sh236-CMV-FKRASG12D/V45D cells were seeded in 15 cm dish and treated for 2 h either with DMSO or MRTX1133 (100 nM). Cells were then washed twice with PBS and lyzed with 750 uL of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 120 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 25 mM NaF, 40 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 100 μM Na3VO3, 1 mM DTT, 100 mM PMSF, 1 mM Benzamidine, 1 μM microcystin). Cell extracts were then transferred and incubated for 2 h at room temperature in anti-Flag antibody (Merck Millipore mAb #F3165) pre-coated MaxiSorp Nunc plates (Thermo #437111). Plates were then washed twice with 200 μL/well of lysis buffer, immune complexes eluted with 50 μL of 1× reconstituted Laemmli sample buffer (BioRad #161-0747) and loaded on NuPage 4–12% gels (Invitrogen #NP0336BOX) for western-blotting analyses.

Statistics and reproducibility

All experiments were repeated two or more times independently, unless otherwise specified in the figure legends, with similar results.

Data availability

Source Data are provided with this paper as a Source data file. All atomic coordinates for the crystallographic structures discovered and shown in this manuscript are deposited at the Protein Data Bank under the following accession codes: 9GLU, 9GLW, 9GLX and 9GLZ. Other previously described crystallographic structures mentioned in this manuscript are deposited at the Protein Data Bank under the following accession codes: 6QUU, 4LRW, 5LZ0 and 5USJ. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Prior, I. A., Hood, F. E. & Hartley, J. L. The frequency of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 80, 2969–2974 (2020).

Scharpf, R. B. et al. Genomic landscapes and hallmarks of mutant RAS in human cancers. Cancer Res. 82, 4058–4078 (2022).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Moore, A. R., Rosenberg, S. C., McCormick, F. & Malek, S. RAS-targeted therapies: is the undruggable drugged? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 19, 533–552 (2020).

Hofmann, M. H., Gerlach, D., Misale, S., Petronczki, M. & Kraut, N. Expanding the reach of precision oncology by drugging all KRAS mutants. Cancer Discov. 12, 924–937 (2022).

Weiss, A. et al. Discovery, preclinical characterization, and early clinical activity of JDQ443, a structurally novel, potent, and selective covalent oral inhibitor of KRASG12C. Cancer Discov. 12, 1500–1517 (2022).

Skoulidis, F. et al. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 2371–2381 (2021).

Janne, P. A. et al. Adagrasib in non-small-cell lung cancer harboring a KRAS(G12C) mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 120–131 (2022).

Lito, P., Solomon, M., Li, L. S., Hansen, R. & Rosen, N. Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. Science 351, 604–608 (2016).

Patricelli, M. P. et al. Selective inhibition of oncogenic KRAS output with small molecules targeting the inactive state. Cancer Discov. 6, 316–329 (2016).

Xue, J. Y. et al. Rapid non-uniform adaptation to conformation-specific KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Nature 577, 421–425 (2020).

Ryan, M. B. et al. KRAS(G12C)-independent feedback activation of wild-type RAS constrains KRAS(G12C) inhibitor efficacy. Cell Rep. 39, 110993 (2022).

Tanaka, N. et al. Clinical acquired resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition through a novel KRAS Switch-II pocket mutation and polyclonal alterations converging on RAS-MAPK reactivation. Cancer Discov. 11, 1913–1922 (2021).

Awad, M. M. et al. Acquired resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 2382–2393 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Diverse alterations associated with resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Nature 599, 679–683 (2021).

Guo, Z. et al. Rapamycin-inspired macrocycles with new target specificity. Nat. Chem. 11, 254–263 (2019).

Shigdel, U. K. et al. Genomic discovery of an evolutionarily programmed modality for small-molecule targeting of an intractable protein surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 17195–17203 (2020).

Schulze, C. J. et al. Chemical remodeling of a cellular chaperone to target the active state of mutant KRAS. Science 381, 794–799 (2023).

Wasko, U. N. et al. Tumour-selective activity of RAS-GTP inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Nature 629, 927–936 (2024).

Holderfield, M. et al. Concurrent inhibition of oncogenic and wild-type RAS-GTP for cancer therapy. Nature 629, 919–926 (2024).

Jiang, J. et al. Translational and therapeutic evaluation of RAS-GTP inhibition by RMC-6236 in RAS-driven cancers. Cancer Discov. 14, 994–1017 (2024).

Ganguly, A. K. et al. Interaction of a novel GDP exchange inhibitor with the Ras protein. Biochemistry 37, 15631–15637 (1998).

Ostrem, J. M., Peters, U., Sos, M. L., Wells, J. A. & Shokat, K. M. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature 503, 548–551 (2013).

Zheng, Q., Zhang, Z., Guiley, K.Z. & Shokat, K.M. Strain-release alkylation of Asp12 enables mutant selective targeting of K-Ras-G12D. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 1114–1122 (2024).

Richardson, S. L., Dods, K. K., Abrigo, N. A., Iqbal, E. S. & Hartman, M. C. In vitro genetic code reprogramming and expansion to study protein function and discover macrocyclic peptide ligands. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 46, 172–179 (2018).

Cherf, G. M. & Cochran, J. R. Applications of Yeast Surface Display for Protein Engineering. Methods Mol. Biol. 1319, 155–175 (2015).

Spencer-Smith, R. et al. Inhibition of RAS function through targeting an allosteric regulatory site. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 62–68 (2017).

Bondeva, T., Balla, A., Varnai, P. & Balla, T. Structural determinants of Ras-Raf interaction analyzed in live cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 2323–2333 (2002).

Tran, T. H. et al. KRAS interaction with RAF1 RAS-binding domain and cysteine-rich domain provides insights into RAS-mediated RAF activation. Nat. Commun. 12, 1176 (2021).

Cookis, T. & Mattos, C. Crystal structure reveals the full Ras-Raf interface and advances mechanistic understanding of Raf activation. Biomolecules 11, 996 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Identification of MRTX1133, a Noncovalent, Potent, and Selective KRAS(G12D) Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 65, 3123–3133 (2022).

Hallin, J. et al. Anti-tumor efficacy of a potent and selective non-covalent KRAS(G12D) inhibitor. Nat. Med. 28, 2171–2182 (2022).

Bill, A. et al. EndoBind detects endogenous protein-protein interactions in real time. Commun. Biol. 4, 1085 (2021).

Lavoie, H. & Therrien, M. Regulation of RAF protein kinases in ERK signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 281–298 (2015).

Whaby, M., Khan, I. & O’Bryan, J. P. Targeting the “undruggable” RAS with biologics. Adv. Cancer Res. 153, 237–266 (2022).

Weng, C., Faure, A. J., Escobedo, A. & Lehner, B. The energetic and allosteric landscape for KRAS inhibition. Nature 626, 643–652 (2024).

Abankwa, D. et al. A novel switch region regulates H-ras membrane orientation and signal output. EMBO J. 27, 727–735 (2008).

Vatansever, S., Gumus, Z. H. & Erman, B. Intrinsic K-Ras dynamics: a novel molecular dynamics data analysis method shows causality between residue pair motions. Sci. Rep. 6, 37012 (2016).

Wylie, A. A. et al. The allosteric inhibitor ABL001 enables dual targeting of BCR-ABL1. Nature 543, 733–737 (2017).

Eberth, A. & Ahmadian, M.R. In vitro GEF and GAP assays. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. Chapter 14, Unit 14 9 (2009).

Kabsch, W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 (2010).

Vonrhein, C. et al. Data processing and analysis with the autoPROC toolbox. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 293–302 (2011).

McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007).

Vagin, A. & Teplyakov, A. Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 22–25 (2010).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Goto, Y., Katoh, T. & Suga, H. Flexizymes for genetic code reprogramming. Nat. Protoc. 6, 779–790 (2011).

Ishizawa, T., Kawakami, T., Reid, P. C. & Murakami, H. TRAP display: a high-speed selection method for the generation of functional polypeptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5433–5440 (2013).

Wiederschain, D. et al. Single-vector inducible lentiviral RNAi system for oncology target validation. Cell Cycle 8, 498–504 (2009).

Hofmann, I. et al. K-RAS mutant pancreatic tumors show higher sensitivity to MEK than to PI3K inhibition in vivo. PLoS One 7, e44146 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following colleagues for their technical support, guidance throughout the study and/or helpful discussions and critical review of the manuscript: Patrizia Fontana, Marco Meyerhofer, Svenya Groebke, Catherine Zimmermann, Paul Westwood, Frédéric Baysang, Michelle Fodor, Ralf Boesch, Richard Felber, Sébastien Ripoche, Dr Dirk Erdmann, Dr Claudio Thoma, Dr Seth Carbonneau, Dr Thomas Huber, Dr Lauren Monovich, Dr Andreï Golosov, Dr Patrick Chène, Dr Tobias Schmelzle and Dr Shiva Malek.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S.B., S.C., N.O., S.M.B. and S.M.M. conceived and supervised the study. C.E.D., L.L., O.E., L.M. and A.M. designed and/or performed and analyzed the mRNA display screens, and/or provided peptide synthesis support. R.C. and K.M. designed and/or performed and analyzed the yeast display studies. K.S.B., S.K., K.P. and A.G. designed and/or performed and analyzed the biochemical and/or biophysical studies. WAR provided the purified proteins used in this study. N.O. and F.Z. designed and/or performed and analyzed the crystallographic studies. J.K., P.W., M.L., D.G., J.D., M.H., D.B., M.B., G.G.G. and S.M.M. designed and/or performed and analyzed the cell-based studies. W.J., S.M.B., G.G.G. and L.T. provided critical intellectual input. S.M.M. was the main writer of the manuscript with input from K.S.B. and L.T.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.S.B., J.K., S.K., P.W., M.L., D.G., K.P., A.G., M.B., J.D., M.H., W.A.R., F.Z., N.O., W.J., C.E.D., L.L., O.E., L.M., A.M., R.C., K.M., G.G.G., L.T., S.C., S.M.B. and S.M.M. are employees and shareholders of Novartis Pharma. D.B. is a former employee of Novartis Pharma.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Anders Friberg, Roman Hillig and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beyer, K.S., Klein, J., Katz, S. et al. Identification and characterization of binders to a cryptic and functional pocket in KRAS. Nat Commun 16, 10836 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65844-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65844-3