Abstract

Urea electrosynthesis through CO2 and NO3- coupling presents a promising alternative to energy-intensive industrial processes. However, intricate catalytic mechanisms and competitive reactions impede achieving high-efficiency C-N coupling. Herein, we constructed analogous rectifying interfaces in AgCu biphasic aerogels, by leveraging electronegativity difference to derive stable Cuδ+ active sites, which simultaneously promoted *NOH adsorption and *CO coverage, thereby improving C-N coupling dynamics, confirmed by both operando technique and theoretical calculations. Specifically, notable urea yield (54.8 mmol h-1 gcat.−1) with Faradaic efficiency (FE, 36.6%) at a low potential (−0.52 V vs. RHE) was achieved using Ag67Cu33 in a flow-cell. As a proof-of-concept demonstration for practicability, Ag67Cu33 exhibited bifunctional electrosynthesis for urea (FE: 56.07%, yield: 104.6 mmol h-1 gcat.−1) and HCOOH (FE: over 90%) at 40 mA cm-2 in two-electrode system, with durability over 60 h. This work provides an indicative rationale to construct active sites for C-N coupling, facilitating the development of urea electrosynthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, global research on greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction strategies has intensified, with a focus on finding innovative solutions for sustainable development. Approximately 12% of anthropogenic GHG emissions are attributed to agricultural production, particularly the synthesis of nitrogen fertilizers such as urea1,2,3,4. Traditionally, urea synthesis is dominated by the Bosch-Meiser process, which operates under extreme conditions (å 180 °C, ~150 bar) and accounts for 2% of global energy consumption and 1.44% of CO2 emissions5,6. Therefore, it is crucial to explore sustainable methods for urea synthesis. With the rapid advancement of renewable energy technologies, electrocatalytic coupling of excess CO2 and harmful NO3- driven by renewable energy presents a promising alternative3,7,8. In 1995, Furuya et al. achieved a significant breakthrough by synthesizing urea for the first time using a Cu-supported gas diffusion electrode with CO2 and NO2- or NO3-9. Subsequently, Wang et al. successfully combined NO3- and CO2 into urea via a Vo-CeO2-750 catalyst, reaching a high yield of 943.6 mmol g-1 h-1 10. Recently, Liao et al. developed a PcNi-Fe-O catalyst and effectively obtained 0.164 g of high-purity urea in a scaled-up flow cell, achieving urea yield of 2.03 g h-1 gcat-1 11. He et al. employed pulsed electrolysis on the synthesized Fe-TPP/CNTs catalyst, reaching a peak FE of 27.70%, rendering urea electrosynthesis more cost-effective and energy-efficient12. Despite considerable efforts, achieving optimal urea synthesis remains challenging due to complex catalytic mechanisms and multiple parallel competitive reactions (Supplementary Table 1)3, underscoring the need to develop high-efficiency electrocatalysts.

Copper (Cu)-based materials are widely recognized as highly effective catalysts for both CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) and NO3- reduction reaction (NO3RR) due to their suitable binding energies with C-intermediates and N-intermediates4,13,14. Consequently, Cu is regarded as one of the most promising materials for facilitating electrocatalytic urea synthesis5, whereas its poor selectivity in intermediate adsorption hinders C-N coupling efficiency13. To address this issue, substantial efforts have been made to improve the selectivity of Cu-based catalysts for specific products5,15,16. For example, by introducing amino substitutions, Wang et al. successfully optimized the electronic structure of CuPc-Amino catalyst, achieving great activity and stability in urea synthesis17. Therefore, modulating the electronic structures of Cu centers through techniques such as structuring interfaces18, incorporating dopants19, introducing defects20 has been suggested as a valuable strategy to effectively control the adsorption/desorption behavior of intermediates. Notably, previous studies have indicated that electron-deficient Cu plays a critical role in enhancing CO2RR and NO3RR by tuning the binding strength of intermediates21. For instance, Li et al. demonstrated that the Cu⁺-rich ultrathin 2D Cu2O nanosheets could effectively increase the adsorption capacity of *CO, facilitating the production of C2+ products15; Niu et al. designed a Cu2O/Cu NRs/CF electrode that achieved rapid *NO3- adsorption, fast reduction of *NO2- to *NO, and highly selective conversion of *NO to *NOH22. Based on these findings, designing catalysts featuring Cuδ+ active sites has great potential to improve urea synthesis performance. However, Cuδ+ sites are easily reduced to Cu0 during electrolysis, resulting in catalyst deactivation, so there is an urgent need to develop strategies to stabilize Cuδ+ sites under negative potentials16. The rectifying interface effect in metal-semiconductor heterojunctions23 can cause charge redistribution and retain it near heterointerfaces by creating a built-in electric field driven by differences in work functions24, which provides a feasible approach for designing Cuδ+-based catalysts18.

However, fabricating catalysts with appropriate rectifying heterointerfaces requires careful consideration of many factors such as work functions, band structures, and dielectric constants, which are highly intricate and sensitive, presenting challenges in effectively controlling electron redistribution even through theoretical methods24. To address these challenges, we proposed using a second metal instead of the semiconductor to construct an analogous rectifying interface effect, which establishes a built-in electric field by utilizing electronegativity differences to induce electron transfer across interfaces. In addition, from the perspective of the material structure, metal aerogels, particularly bimetallic aerogels (e.g., BiSn25, PdAg26, etc.) emerge as promising candidates due to their three-dimensional porous structure, large surface areas, abundant active sites, and excellent structural durability27. Among these, Ag stands out as an ideal secondary metal due to its great electrical conductivity, thermodynamic immiscibility with Cu28,29 and its potential to induce electron-deficient Cu. Overall, the construction of AgCu biphasic aerogels with the analogous rectifying interface effect provides a feasible method to generate stable Cuδ+ sites and enhance electrocatalytic performance in urea formation.

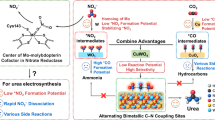

Herein, we fabricated a series of AgxCu100-x biphasic aerogels featuring analogous rectifying interfaces via a one-step reduction using NaBH4. The analogous rectifying interface effect successfully generated stable Cuδ+ active sites near the interfaces, enhancing the critical C-N coupling dynamics, which resulted in an impressive urea yield of 54.8 mmol h-1 gcat.−1 with a high Faradaic efficiency (FE) of 36.6% using Ag67Cu33 catalyst at a low potential (−0.52 V vs. RHE) in a three-electrode flow cell, showing significant stability for 24 h, while also exhibiting great activity (yield: 22.59 mmol h-1 gcat.−1, FE: 32.4%) in an H-cell. Operando synchrotron radiation-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (SR-FTIR) and density functional theory (DFT) calculations revealed that the C-N coupling between *CO and *NOH constituted a pivotal step in urea electrosynthesis, while Cuδ+ sites effectively accelerated the reaction by simultaneously facilitating *NOH adsorption and improving *CO coverage. Specifically, compared to Cu0 sites, Cuδ+ sites exhibited a greater affinity for *NOH adsorption over *NHO, enabling successful C-N coupling with *CO to form *NOHCO through a thermodynamically spontaneous and kinetically accessible process, while *NHO was more prone to protonation, inhibiting the C-N coupling. Furthermore, Cuδ+ sites reduced the free energy barrier for CO₂RR and stabilized *CO intermediate, which might increase *CO coverage on the surface for subsequent C-N coupling (Fig. 1). Additionally, to assess industrial feasibility, Ag67Cu33 was employed as a dual-function catalyst in a two-electrode flow cell that integrated cathodic urea synthesis with anodic formaldehyde oxidation reaction (FOR), which showcased great performance for both urea (FE: 56.07%, yield: 104.6 mmol h-1 gcat.−1) and HCOOH production (FE: above 90%) at a high current density of 40 mA cm-2, maintaining satisfactory durability over 60 h. Our research highlighted the significant role of the analogous rectifying interface effect in AgCu biphasic aerogels and uncovered the crucial coupling reactions that enabled impressive urea synthesis, ultimately demonstrating the practical applicability of our catalyst in a two-electrode system.

a The formation of stable Cuδ+ sites through the analogous rectifying interface effect in AgCu biphasic aerogels. b The electron-deficient Cuδ+ enhances the affinity adsorption of *NOH, facilitating successful coupling to urea, while the ineffective adsorption of *NHO on conventional Cu0 prevents further coupling.

Results

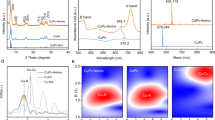

As depicted in Fig. 2a, a series of biphasic aerogel catalysts, AgxCu100-x (where x represented the theoretical mole fraction of Ag), were fabricated using a simple reduction method by introducing NaBH4 into a mixed solution of silver nitrate and copper nitrate (details were provided in the Methods section). The actual Ag and Cu content was determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), and the results (Supplementary Table 2) aligned with the expected stoichiometric ratios, indicating the complete reduction of metal ions. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of Ag67Cu33 (Fig. 2b) closely matched the standard reference patterns for pure Ag (PDF#04-0783) and Cu (PDF#04-0836), suggesting no oxide formation. No shifts in XRD peaks were observed in all catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that AgxCu100-x existed as distinct metallic Ag and Cu rather than forming an alloy30.

a Illustration for the preparation of AgxCu100-x (the blue, red, yellow, green, gray and white balls represented Cu, Ag, O, N, C, H atoms, respectively). b XRD pattern of Ag67Cu33. TEM (the inset is the corresponding SAED pattern) image (c) and HAADF-STEM image (d) of Ag67Cu33. STEM-EDX image with Cu (blue) and Ag (red) elemental mapping (e) and corresponding EDX line scanning from yellow box area (f) of Ag67Cu33. g Comparison of high-resolution Ag 3 d XPS spectra of Ag and Ag67Cu33. h Comparison of high-resolution Cu 2p XPS spectra of Cu and Ag67Cu33. Source data for Fig. 1 are provided as a Source Data file.

The morphology and structure of AgxCu100-x catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 2), as characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), exhibited a typical aerogel with a three-dimensional porous network structure, which remained consistent across different molar ratios. Additionally, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of Ag67Cu33 (Fig. 2c) showed a network composed of interconnected nanoparticles, with each particle approximately 40 nm in diameter. High-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) image of Ag67Cu33 (Supplementary Fig. 3a) provided direct evidence for the separation of crystallized Ag and Cu along with the formation of Ag-Cu biphasic interfaces. The two distinct lattice spacings (Supplementary Fig. 3d-e), approximately 0.209 nm and 0.236 nm, corresponded to Cu(111) and Ag(111) planes, respectively, consistent with the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern and XRD data. Furthermore, energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) mapping (Supplementary Fig. 3b) revealed the phase-separated components in Ag67Cu33, with Ag and Cu concentrations of 61.62% and 38.38%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

Subsequently, scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) combined with EDX spectroscopy, was utilized to investigate the Ag-Cu interfaces in more detail. The high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF-STEM) image (Fig. 2d), obtained by magnifying the white box in Fig. 2e, revealed a well-defined interface and atomic structures of metallic Cu and Ag with a crystallographic zone axis of [100], while the lattice spacings of 0.208 nm and 0.237 nm corresponded to cubic Cu(111) and cubic Ag(111), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4). STEM-EDX mapping (Fig. 2e) and the line scan profile (Fig. 2f) further confirmed the distinct distribution of Ag and Cu, with a well-defined interface in biphasic aerogel, rather than the formation of an Ag-Cu alloy28, as expected based on the limited miscibility of Ag and Cu according to the binary phase diagram29. The surface elemental compositions and chemical states, analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) revealed the presence of Ag, Cu, O, and C (Supplementary Fig. 5). In the high-resolution spectra of the Ag 3 d region (Fig. 2g), the peaks at 368.31 eV and 374.30 eV in Ag67Cu33 corresponded to Ag 3d5/2 and Ag 3d3/2 of Ag0, exhibiting a slight shift to lower binding energy compared to pure Ag (368.46 eV and 374.45 eV)26. Meanwhile, in the Cu 2p spectra (Fig. 2h), the Cu0/Cu+ peaks in Ag67Cu33, located at 952.46 eV (Cu 2p1/2) and 932.61 eV (Cu 2p3/2), shifted to higher binding energy compared to pure Cu (952.35 eV and 932.51 eV)14,31, indicating electron transfer from Cu to Ag and confirming the successful establishment of an analogous rectifying interface effect in AgCu biphasic aerogel. Although two peaks corresponding to Cu 2p1/2 and 2p3/2 of Cu2+ were present in both Ag67Cu33 (954.55 eV and 934.76 eV) and pure Cu (954.44 eV and 934.64 eV)32, the partial oxidation was attributed to surface exposure to air during ex-situ measurements30.

The urea synthesis efficiency of AgxCu100-x catalysts was evaluated in an H-cell with a three-electrode system (Fig. 3a) using controlled potential electrolysis, where the applied potentials ranged from -0.22 V to -0.62 V versus RHE (unless otherwise specified, all potentials were referenced to the reversible hydrogen electrode). Gas products (H2, CO) and liquid products (urea, NH3, NO2-) were detected using gas chromatograph (GC) and UV visible photometer (UV-Vis), respectively (see Methods section for details)6,14,18. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves for AgxCu100-x (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 6) showed that these catalysts exhibited activity for both CO2RR and NO3RR in CO2-saturated 0.5 M KHCO3 and Ar-saturated 0.5 M K2SO4 of 2000 ppm KNO3, respectively. Notably, AgxCu100-x demonstrated that higher current densities when CO2 and NO3- were introduced simultaneously, indicating a potential coupling reduction process8. Additionally, increasing the Cu content led to higher current densities, as shown in the i-t curves for AgxCu100-x (Supplementary Fig. 7), suggesting that Cu might be the active sites of the reactions. Figs. 3c, d illustrated the urea yield rate and FE of AgxCu100-x at various applied potentials (Supplementary Fig. 8), where Ag67Cu33 achieved the highest urea yield rate of 22.59 mmol h-1 gcat.-1 with a corresponding FE of 32.4% at -0.52 V. Notably, all AgCu catalysts exhibited better urea performance compared to pure Cu, confirming the critical role of the analogous rectifying interface effect in enhancing urea synthesis. Furthermore, the poor urea yield of pure Ag suggested that the improved performance was not due to the introduction of Ag alone. The FE of all possible products during the electrochemical urea synthesis on AgxCu100-x were measured (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Table 3), showing higher FE of NO2- and NH3 with increased Cu content or more negative potentials, which indicated that increased competition from NO3RR reduced urea FE33. In addition, AgCu catalysts exhibited lower FE for N-bearing by-products and H2 than pure Cu, especially Ag67Cu33, suggesting analogous rectifying interface effect might suppress competitive reactions.

(catholyte: CO2-saturated 0.5 M KHCO3 with 2000 ppm KNO3, catalyst loading: 0.5 mg cm-2, pH: 7.4 ± 0.3; temperature: 25 °C; measured resistance: 4 ± 0.5 Ω, without IR compensation) (a) Schematic diagram for an H-cell (WE, RE and CE were working electrode, reference electrode and counter electrode). b LSV curves over Ag67Cu33. Urea yield rate (from left to right, the sequence was from Ag100Cu0 to Ag0Cu100) (c) and corresponding FE (d) on AgxCu100-x at various applied potentials. e Stability tests of Ag67Cu33 at −0.52 V for 6 h. f The comparison of 1H NMR spectra of the electrolyte after the electrolysis obtained in 15N- and 14N-isotope labeling experiments. g Comparison of 1H-NMR and diacetyl monoxime test results. h Urea yield rate in different cathode electrolytes (the inset represented the actual colored solution used for UV-Vis measurement). Source data for Fig. 2 are provided as a Source Data file.

Additionally, stability was another important parameter for evaluating catalyst performance. Recycling tests conducted on Ag67Cu33 at -0.52 V (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 10) revealed no significant decrease in current density, and the urea yield rate remained above 20.05 mmol h-1 gcat.-1 with an FE of over 27.8% after 6 continuous cycles. This great stability was corroborated by TEM, HRTEM, and XPS results after the stability experiments (Supplementary Fig. 11), which showed no obvious change throughout the electrolysis process. Moreover, post-test SEM (Supplementary Fig. 12) and XRD (Supplementary Fig. 13) analyses displayed no noticeable morphology and structural change in AgxCu100-x catalysts, except for pure Cu. The presence of Cu2O in Supplementary Fig. 13e likely resulted from air exposure after testing34, as the small size and high surface area of the pure Cu aerogel made it more susceptible to oxidation, while the introduction of Ag appeared to enhance the resistance to oxidation35. To further investigate the electrocatalytic activity of AgxCu100-x catalysts, the electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) was measured, as it played a crucial role in enhancing electrocatalytic performance36 (Supplementary Fig. 14). Despite the similar microstructures, Ag67Cu33 exhibited the largest ECSA, indicating a greater number of active sites available for catalytic reactions. Additionally, the turnover frequency (TOF) of AgxCu100-x, which signified the rate of electron consumption per unit time at an individual active site, was evaluated to gain deeper insights into their intrinsic catalytic activity37. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, the calculated n values for Ag, Ag80Cu20, Ag67Cu33, Ag50Cu50, and Cu were 4.09 × 10-10, 1.07 × 10-9, 1.21 × 10-9, 1.03 × 10-9 and 6.61 × 10-10, respectively, indicating that Ag67Cu33 possessed the highest number of active sites, which was consistent with the ECSA results. Moreover, Ag67Cu33 demonstrated the highest TOF value across the entire applied potential range, confirming its better intrinsic catalytic activity and thereby enhancing urea synthesis performance.

Isotope-labeling experiments were conducted in CO2-saturated 0.5 M KHCO3 electrolytes containing 2000 ppm K15NO3 or K14NO3 to verify the origin of the urea produced via the CO2 and NO3- coupling reaction. As shown in Fig. 3f, the 1H-NMR spectrum2 of the electrolyte with K15NO3 after electrochemical testing exhibited characteristic double peaks at 5.70 ppm and 5.55 ppm, consistent with the standard 15NH2CO15NH2. In contrast, a single peak at 5.63 ppm corresponded to the formation of 14NH2CO14NH2 within the electrolyte containing K14NO3, confirming that the urea produced in this work originated from the electrocatalytic coupling of NO3- and CO2. Moreover, the absence of urea in electrolytes lacking either CO2 or KNO3 (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Fig. 16) further supported that the urea synthesis was driven by the co-reduction of CO2 and NO3-, ruling out any potential impurities. Subsequently, the 1H-NMR method1 was also used to validate the accuracy of the urea yield determined by the diacetyl monoxime method. Based on the standard urea curve (Supplementary Fig. 26), the comparable urea yields from both methods confirmed the reliability of our results (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 17). Compared with previously reported catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 18 and Table 4), our work demonstrated great performance, with an impressive urea yield rate and high FE at low potentials.

To enhance the catalytic performance for electrochemical urea synthesis, we conducted electrochemical tests in a three-electrode flow cell (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 19a) under applied potentials ranging from −0.22 V to −0.62 V. Previous studies showed that flow cells significantly improved electrocatalytic performance in reactions such as NO3RR and CO2RR38. Due to the more competitive CO2RR in flow cells39, a higher concentration of NO3- was required to facilitate the C-N coupling reaction. As the concentration of KNO3 increased (Supplementary Fig. 19), Ag67Cu33 achieved a higher urea yield rate along with an increased FE, reaching its optimum at 0.5 M KNO3. However, excessively high KNO3 concentrations inhibited CO2 adsorption by promoting NO3- adsorption, thereby favoring competitive NO3RR and resulting in a decline in both urea yield rate and FE40. Thus, 0.5 M KNO3 was selected for subsequent electrochemical tests in the flow cell.

(catholyte: CO2-saturated 0.5 M KHCO3 with 0.5 M KNO3, catalyst loading: 1.0 mg cm-2, pH: 7.4 ± 0.3; temperature: 25 °C; measured resistance: 1.5 ± 0.2 Ω, without IR compensation) (a) Schematic diagram for a three-electrode flow cell (WE, RE and CE were working electrode, reference electrode and counter electrode). b LSV curves over Ag67Cu33. c Urea yield rate and FE on Ag67Cu33 at different applied potentials. d FE for all products on Ag67Cu33 (from the bottom up, the sequence was NO2-, NH3, Urea, CO and H2). e Comparison of the urea yield rate of our work with the latest literatures in the flow cell. f Chronoamperometric curves, urea yield rate and FE of Ag67Cu33 at -0.52 V for 24 h. Source data for Fig. 3 are provided as a Source Data file.

As shown in Fig. 4b, the significantly increased current density confirmed enhanced CO2RR activity. When CO2 and NO3- were introduced simultaneously, there was a notable increase in current density, although NO3RR became increasingly competitive at potentials beyond -0.62 V. Remarkably, Ag67Cu33 achieved a maximum urea yield rate of 54.8 mmol h-1 gcat.-1 with an FE of 36.6% at -0.52 V through potentiostatic tests (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 20), surpassing previously reported results (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 5). Additionally, as more negative potentials were applied, an increasing production of NO2- and NH3 was observed (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 21), consistent with the LSV curves. A long-term stability test (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 22) was conducted at -0.52 V to assess the intrinsic stability of Ag67Cu33. Notably, both the urea yield rate and FE remained above 50.1 mmol h-1 gcat.-1 and 36.9%, respectively, over a 24-hour period, while the SEM image and XRD pattern (Supplementary Fig. 23) of Ag67Cu33 after 24 h of electrocatalysis confirmed that the catalyst maintained its morphology and structural integrity. Furthermore, ICP-MS was utilized to analyze the dissolution conditions of the catalyst. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 24, trace amounts of Ag and Cu were detected in the post-electrolytes, with the final catalyst mass on carbon paper stabilizing at 0.97 mg (closely aligning with the calculated loss of 0.95 mg from the electrolytes). Notably, given the higher molar ratio (Ag:Cu = 71.9:28.1) of the post-test catalyst and the greater loss of Cu in the post-electrolytes, the slight catalyst loss could be attributed to surface oxidation at OCP when refreshing the electrolytes and subsequent dissolution under reductive potentials41. Despite a minor leaching during the stability tests, the catalyst remained largely intact after testing, confirming its satisfactory electrochemical and structural stability.

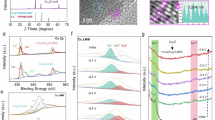

To gain mechanistic insights into the high activity of Ag67Cu33 in electrocatalytic urea synthesis, we employed synchrotron radiation X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectroscopy, operando Raman spectroscopy and synchrotron radiation-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (SR-FTIR). In regards to the XPS analysis results of Ag67Cu33 (Supplementary Fig. 11), it was evident that Ag existed in a zero-valent state, while Cu showed minor oxidation. Therefore, ex-situ synchrotron radiation XANES (Supplementary Fig. 31a) was employed to assess the chemical state of Cu in Ag67Cu33 following LSV activation and potentiostatic tests (from -0.22 V to -0.62 V). In the XANES spectrum of Cu L-edge at OCP (Supplementary Fig. 31b), the peaks at 931.9 eV and 951.8 eV were assigned to the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 states of metallic Cu, while a minor peak indicative of Cu-O bonding was also observed33, likely arising from surface oxidation during the catalyst loading process. Notably, after electrochemical treatment, the spectral features exclusively exhibited metallic Cu peaks, without oxide signatures. Furthermore, operando Raman spectroscopy was utilized to further investigate this transformation. As shown in Fig. 5a, several vibrational modes observed at OCP were attributed to CuO (319 and 614 cm-1)16 and Cu2O (217 and 635 cm-1)22, resulting from surface oxidation following air exposure. During continuous LSV measurements to activate the catalyst, these peaks gradually diminished and disappeared after 10 min, indicating the complete reduction of CuO and Cu2O to metallic Cu. Furthermore, no peaks corresponding to either Ag or Cu oxides were detected during subsequent potentiostatic tests, suggesting Ag67Cu33 retained its metallic Cu and Ag composition throughout the electrochemical process (Supplementary Fig. 33), aligned well with the XANES results (Supplementary Fig. 31b).

a Operando Raman spectroscopy curves of Ag67Cu33 during its electrochemical activation for different times. Infrared signals in the range of 1,000-2,200 cm-1 from -0.22 V to -0.62 V (b) and control experiments in different electrolytes at −0.52 V(c) obtained from operando SR-FTIR measurements during Ag67Cu33 electrolytic process (OCP was open circuit potential). d Bader charge for Ag(111)-Cu(111). The red color and the blue color respectively indicated charge accumulation and depletion (Arrow was used to indicate the transition from charge accumulation to depletion). e Free energy diagram of urea production on Ag(111)-Cu(111) (RDS was rate-determining step). f Charge density distributions of adsorbed *NOH on Ag(111)-Cu(111). The cyan and purple areas display the electron gain and loss, respectively (Isosurface = 0.005 e/Å3). The blue, red, yellow, green and white balls represent Cu, Ag, O, N, H atoms, respectively. Free energy diagram of CO2RR (g) and projected density of states (PDOS) of d orbitals (h) on Ag(111), Ag(111)-Cu(111) and Cu(111). Source data for Fig. 4 are provided as a Source Data file and Supplementary Data 1.

Subsequently, operando SR-FTIR measurements (Supplementary Fig. 34) were conducted to monitor the evolution of reaction intermediates during the electrochemical process, with infrared signals collected between -0.22 V and -0.62 V using post-background subtraction for accuracy. At OCP, there was no significant interference from electrolytes or other species, which facilitated the detection of chemical signals. As illustrated in Fig. 5b, peaks observed at 1984 cm-1 and 2148 cm-1 corresponded to the stretching modes of *NO and *CO respectively42, indicating the successful absorption and co-activation of NO3- and CO2 on the catalyst. Additionally, the band at 1178 cm-1 was attributed to C-O stretching vibrations, suggesting CO2RR was occurring1,5. Moreover, a stretching vibration band associated with C-N emerged at 1452 cm-1 alongside -NH2 rocking vibrations at 1090 cm-17,43, peaking at -0.52 V, which was consistent with experimental results, providing crucial evidence for successful urea formation. It was noteworthy that an evident infrared band around 1686 cm-1 could be ascribed to *COOH and *CONH intermediates1,42,44, whose variation pattern with applied potentials agreed well with experimental observations, indicating that these intermediates, particularly *CONH, played a critical role in subsequent urea generation. Additionally, an infrared band associated with H2O vibration45 appeared within the range of 1640-1670 cm-1; thus control experiments using various electrolytes were performed via SR-FTIR to detect generated intermediate species while minimizing interference from H2O (Fig. 5c). Combined with electrocatalytic experiment results (Supplementary Fig. 16), when no CO2 gas was present, the infrared band at 1643 cm-1 should be assigned to H-O-H vibration; however, upon injecting CO2 gas, which led to the synthesis of either CO or urea, the infrared band broadened slightly while exhibiting a minor blue shift but retained a shoulder peak around 1643 cm-1, which further corroborated the band at 1686 cm-1 belonged to *COOH and *CONH intermediates38. Meanwhile, infrared vibrations associated with other products in CO2RR or NO3RR, including CO, NO2- and NH346,47,48, were also successfully tracked.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the intrinsic mechanisms underlying urea synthesis and the role of analogous rectifying interface effect in AgCu biphasic aerogels for C-N coupling, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed (Supplementary Data 1). Given that Ag67Cu33 exhibited phase separation with well-defined interfaces and distinct Ag(111) and Cu(111) orientations, as indicated by the experimental results (Fig. 2), an Ag(111)-Cu(111) model with an interface was constructed (Supplementary Fig. 35). The Bader charge analysis of the Ag(111)-Cu(111) model was conducted to assess electron redistribution around the Ag-Cu interface (Fig. 5d). As predicted by the analogous rectifying interface effect, a built-in electric field arose between Ag and Cu due to their differences in electronegativity, resulting in the transfer of electrons from Cu to Ag, which led to the formation of stable electron-deficient Cuδ+ sites near the interface, consistent with the XPS results. Notably, Cuδ+ was identified as an active site for electrocatalytic urea synthesis, as well as for CO2RR19 and NO3RR20, based on previous studies and our computational results. The free-energy diagram for urea synthesis on Ag67Cu33 (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Fig. 36-39 and Table 6) showed that CO2 and NO3- could be adsorbed and activated with a low energy barrier. Importantly, compared to pure Cu0 (Supplementary Fig. 40-42 and Table 7), *NO tended to undergo protonation to form *NOH rather than *NHO on Cuδ+ sites, which played a key role in successful urea generation. Specifically, on Ag67Cu33, *NOH preferentially coupled with *CO to form the key intermediate *NOHCO via a thermodynamically spontaneous process (ΔG = -0.63 eV), and the transition state (TS) energy barrier (Supplementary Fig. 37) for the first C-N coupling (0.67 eV) was significantly lower compared to that required for the formation of *CO + *NHOH (0.95 eV), making C-N coupling more favorable from both thermodynamic and kinetic perspectives than the alternative route involving *NOH protonation. Following the second NO3- adsorption, the system successfully enabled the second C-N coupling and yielded the intermediate *H2NCONO through an energetically downhill step (ΔG = -0.38 eV) with a relatively low TS energy barrier (0.87 eV), ultimately facilitating the efficient synthesis of urea. In contrast, on pure Cu surfaces, *NHO protonated to *NHOH more easily than undergoing C-N coupling due to the higher free energy barrier for the latter. Unfortunately, C-N coupling still failed to occur in subsequent reaction steps, resulting in poor urea production with CO and NH3 by-products instead (Supplementary Fig. 9q). To further investigate the impact of electron deficiency in Cu on intermediate adsorption, we calculated charge density distributions (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 46) and performed Bader analysis (Supplementary Table 10) for adsorbed species (*NO, *NHO, and *NOH) on Ag67Cu33 as well as pure Cu. Considering the electronegativity difference between H (2.2) and Cu (1.9), N and O were more likely to accept electrons from Cu, leading to the formation of the *NHO intermediate, where both N and O were in direct contact with Cu. However, it might be challenging for Cuδ+ sites to supply enough electrons, so another combination was adopted to form a more stable *NOH intermediate where H atom could transfer more electrons to O and N. Additionally, Cuδ+ sites not only reduced the energy barrier for CO2 conversion to *CO (ΔG = 0.44 eV), but also exhibited a higher endothermic barrier for *CO desorption (ΔG = 0.46 eV), enhancing CO2 activation and stabilizing *CO on the surface to improve its coverage36, which could promote further C-N coupling and facilitate urea synthesis, as indicated by Gibbs free energy changes in fundamental steps during CO2RR towards CO (Fig. 5g, Supplementary Fig. 47 and Table 9). Subsequently, the projected density of states (PDOS) of d orbitals further supported these conclusions (Fig. 5h), which exhibited that the d-band center of Cuδ+ sites shifted towards the Fermi level compared with pure Cu or pure Ag. According to d-band center theory49, an upshifted Ed of metal surface could enhance the binding strength between metal surface and adsorbed species, consistent with Gibbs free energy change results. Additionally, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 43-45 and Table 8, the free-energy diagram of urea synthesis on Ag(111) revealed that although *NHO readily coupled with *CO at a low energy barrier to form the first C-N bond (*CONHO), the high adsorption energy of CO2 and the weak binding strength of *CO (Fig. 5g) would result in insufficient *CO surface coverage. Furthermore, the limited active sites led to the poorest intrinsic catalytic activity (Supplementary Fig. 14-15), thereby collectively contributing to the restricted current densities and urea yield rates observed for Ag (Supplementary Fig. 7-8). To further verify the importance of the analogous rectifying interface effect, we physically blended pure Ag and pure Cu aerogels to create an Ag-Cu catalyst (Ag2Cu1) without interfaces (Supplementary Fig. 53). However, its urea synthesis performance (Supplementary Fig. 54) was significantly inferior to that of Ag67Cu33, with no notable enhancement observed, thereby emphasizing the essential importance of the analogous rectifying interface effect within Ag-Cu biphasic aerogels. Furthermore, by employing DFT calculations on NO3RR (Supplementary Fig. 48a, 49 and Table 11), HER (Supplementary Fig. 48b, 50 and Table 12), and CO2-to-C2+ (Supplementary Fig. 51-52 and Table 13), a comprehensive comparison was carried out among these potential competing reactions, which demonstrated that Cuδ+ active sites possessed a pronounced preference for C-N coupling, thereby promoting the formation of urea with satisfactory selectivity. Overall, the analogous rectifying interface effect (Supplementary Fig. 55) facilitated the formation of stable electron-deficient Cuδ+ active sites in AgCu biphasic aerogels, which might not only increase the affinity for *NOH and promote C-N coupling with *CO but also enhance the surface coverage of *CO through facile CO2 activation and *CO stabilization, ultimately accelerating C-N coupling dynamics and improving urea synthesis efficiency.

In order to further investigate the industrial potential of our catalyst, we designed a two-electrode flow cell that integrated urea synthesis with formaldehyde oxidation reaction (FOR), as Ag-Cu catalysts showed promising performance in FOR50. Thus, Ag67Cu33 was employed as a dual-function catalyst at both the cathode and anode in this system (Fig. 6a). This approach not only reduced the onset potential of the anode by replacing the sluggish oxygen evolution reaction (OER, å 1.23 V vs. RHE) with a low thermodynamic potential process (HCHO + 2OH− → HCOO− + 1/2H2 + H2O + e−, E = -0.22 V vs. RHE)3,51, but also enabled the conversion of excess CO2 and waste NO3- into sustainable urea while producing high-value HCOOH. UV-vis spectroscopy and 1H NMR spectroscopy were employed to detect urea (Supplementary Fig. 25) and HCOOH (Supplementary Fig. 30), respectively. As shown in Fig. 6b, the LSV curves exhibited two distinct oxidation peaks in the absence of HCOH, corresponding to the Cu0/CuI and CuI/CuII oxidation processes50. Notably, when a high concentration of HCOH (0.6 M) was introduced into the anolyte, these oxidation peaks diminished due to the preferential oxidation of HCOH (-0.22 VRHE), occurring at lower potentials than Cu0/CuI and CuI/CuII transitions (approximately 0.4 and 0.7 VRHE, respectively). Furthermore, incorporating 0.6 M HCOH in the anode and 0.5 M KNO3 in the cathode resulted in a significant increase in current density, reaching 10 mA cm-2 at 0.34 V, a drop of approximately 1.5 V compared to OER | | CO2RR, confirming the successful implementation of this two-electrode system.

(anolyte: 1 M KOH with 0.6 M HCOH, catalyst loading: 0.5 mg cm-2; catholyte: CO2-saturated 0.5 M KHCO3 with 2000 ppm KNO3, catalyst loading: 0.5 mg cm-2, pH: 7.4 ± 0.3; temperature: 25 °C; measured resistance: 2 ± 0.2 Ω, without IR compensation) (a) Scheme of the two-electrode flow cell coupling cathodic urea synthesis/Ag67Cu33 and anodic FOR/Ag67Cu33 (AEM was anion exchange membrane). b LSV curves for various conditions in the electrolyzer (OER | | CO2RR: 1 M KOH | | 0.5 M KHCO3 with CO2; OER | |Urea synthesis: 1 M KOH | | 0.5 M KHCO3 with CO2 and NO3-; FOR | |Urea synthesis:1 M KOH with 0.6 M HCOH | | 0.5 M KHCO3 with CO2 and NO3-; FOR | | HER: 1 M KOH with 0.6 M HCOH | | 0.5 M K2SO4). The yield rate and FE on Ag67Cu33 of urea in the cathode(c) and HCOOH in the anode(d) at various current densities in the two-electrode flow cell. e The potential-time curves, urea yield rate and HCOOH FE of two-electrode electrolyzer at 40 mA cm-2 by 10 cycles, with each cycle presenting 1 h. f The yield rates and FE of long-term electrolysis at 40 mA cm-2 for 60 h. Source data for Fig. 5 are provided as a Source Data file.

After activization in an H-cell, Ag67Cu33 was directly employed as both the cathode and anode for subsequent constant current experiments (ranging from 15 to 45 mA cm-2). Specifically, as the current density increased (Supplementary Fig. 56), both the yield rate and FE of urea gradually rose (Fig. 6c), reaching maximum values at 40 mA cm-2 (104.6 mmol h-1 gcat.-1 and 56.07%, respectively). Concurrently, the yield rate of HCOOH continued to increase, achieving 3.09 mmol h-1 mgcat.-1 at 45 mA cm-2, although its FE experienced a slight decline, remaining above 90% (Fig. 6d). Additionally, SEM images and XRD results of both the anodic and cathodic catalysts after testing (Supplementary Fig. 57) demonstrated Ag67Cu33 maintains its aerogel morphology, along with metallic Ag and Cu phases, aligning well with the LSV curves. Further cycling tests were conducted at 40 mA cm-2 to assess the stability of Ag67Cu33 (Supplementary Fig. 58). The results indicated that both urea yield rate and HCOOH FE exhibited slight fluctuations, but consistently remained above 95.3 mmol h-1 gcat.-1 and 90.6%, respectively, over ten cycles (Fig. 6e). Although there was a minor increase in potential during each cycle, likely due to reactant depletion, the potential could be restored to its initial value by refreshing the electrolytes, demonstrating strong stability. Based on these findings, a current density of 40 mA cm-2 was selected to investigate the industrialization potential through a long-term stability test (Supplementary Fig. 59-60), with electrolyte refreshment every 10 h. As depicted in Fig. 6f, Ag67Cu33 exhibited well stability in both urea synthesis and FOR throughout the experiment. SEM images, XRD results and XPS spectra obtained after 60 hours of testing (Supplementary Fig. 61) were nearly identical to those before testing. Furthermore, the catalyst leaching at the cathode (maintaining 0.44 mg) was comparable to that observed in a three-electrode flow cell41, while the anode (retaining 0.43 mg) exhibited slightly higher Ag loss, which were attributed to the slight oxidation and dissolution processes occurring under anodic conditions50 (Supplementary Fig. 62). Owing to the intrinsic robust structure of metal aerogels and the enhanced oxidation resistance provided by Ag27, there was no rapid or extensive dissolution of the catalyst, thereby preserving its performance throughout the stability tests. All these findings further corroborated the great electrocatalytic activity and stability of our catalyst. In conclusion, the dual-functional Ag67Cu33 catalyst demonstrated significant electrocatalytic performance and stability for both urea synthesis and FOR within our two-electrode system at low cell voltages, significantly highlighting its potential for practical application.

In summary, we developed three-dimensional porous Ag-Cu biphasic aerogels with well-defined analogous rectifying interfaces, enabling efficient urea production via the co-electrolysis of NO3- and CO2. Ag67Cu33 catalyst exhibited satisfactory catalytic performance, achieving a maximum urea yield rate of 22.59 mmol h-1 gcat.-1 in an H-cell and 54.8 mmol h-1 gcat.-1 in a three-electrode flow cell, surpassing most reported catalysts. Both experimental results and DFT calculations highlighted the crucial role of the analogous rectifying interface effect, which successfully generated stable electron-deficient Cuδ+ active sites near the interfaces, thus enhancing C-N coupling efficiency and promoting urea synthesis. Compared to Cu0 sites, Cuδ+ sites possessed a strong affinity for *NOH adsorption, thereby enabling effective coupling with *CO to form the crucial intermediate *NOHCO through a thermodynamically spontaneous and kinetically accessible process rather than direct protonation. Furthermore, Cuδ+ sites lowered CO2RR barriers to facilitate CO2 activation while stabilizing *CO on the surface, increasing *CO coverage and further promoting C-N coupling. Additionally, the investigation of a two-electrode system employing Ag67Cu33 as a dual-function catalyst demonstrated its potential for practical applications. It showcased great bifunctional performance for both urea (FE: 56.07%, yield: 104.6 mmol h-1 gcat.-1) and HCOOH electrosynthesis (FE: over 90%) at a high current density of 40 mA cm-2, while maintaining significant durability over 60 h. This work provides an indicative rationale to construct active sites for C-N coupling, offering insights for future applications of C-N coupling systems in the production of high-value chemicals.

Methods

Chemical and materials

Copper nitrate trihydrate (Ⅱ) (Cu(NO3)2·3H2O, AR), silver nitrate (Ⅰ) (AgNO3, 99.8%), sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 98%), potassium bicarbonate (KHCO3, 99.5%), potassium sulfate (K2SO4, 99%), potassium chloride (KCl, 99.8%), nitrate of potash (KNO3, 99%), Nafion solution (5 wt.%), urea (CO(NH2)2, 99%), iron chloride (Ⅲ) (FeCl3·6H2O, 99%), thiosemicarbazide (MTSC, 98.5%), diacetyl monooxime (DAMO, >98%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95%-98%), phosphoric acid (H3PO4, >85 wt.% in H2O), potassium nitrate-15N (K15NO3, 99%), 15N-urea (CO(15NH2)2, 99%), dimethylsulfoxide-d6 (d6-DMSO, 99.9% D.), sodium nitrite (NaNO2, 99%), sulfonamide (C6H8N2O2S, 99%), N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (NETH, 98%), ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, 99.8%), potassium sodium tartrate tetrahydrate (C4H4KNaO6·4H2O, 99%), Nessler Reagent, ethyl alcohol (C2H5OH, 99.9%), nitric acid (HNO3, 65%-68%), potassium hydroxide (KOH, 90%), formaldehyde solution (36 wt.% in H2O), deuteroxide (D2O, 99.9% D.), dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). All reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Corporation and used without further purification. Carbon papers were purchased from Hesen company (Shanghai, China). High-purity deionized water (resistance 18 MΩ cm-1) were used to prepare aqueous solutions in all experiments.

Synthesis of the AgxCu100-x aerogels

The AgxCu100-x aerogels were prepared via a NaBH4-induced in situ reduction process. Taking the synthesis of Ag67Cu33 aerogel as an example, NaBH4 (50 mM, 25 mL) was homogeneously dissolved in deionized water in the ice-water bath, then the mixed aqueous solutions of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O (50 mM, 1.67 mL) and AgNO3 (50 mM, 3.33 mL) were rapidly dropped into the NaBH4 solution, and the color of the solution turned black instantly. After keeping stirring in the ice-water bath for 1 hour, Ag67Cu33 aerogel was collected by centrifugation and washed with water and ethanol for three times, and finally obtained by freeze-drying procedure. The AgxCu100-x aerogels were acquired using the aforementioned synthetic procedures by varying the molar ratio of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O and AgNO3 (Supplementary Table 2). The pure Ag and pure Cu aerogel catalysts synthesized using the identical method, with the only difference being the addition of either AgNO3 or Cu(NO3)2·3H2O.

The Ag2Cu1-mixture catalyst was synthesized by physically blending pure Ag and pure Cu aerogel (obtained from the aforementioned method) in a molar ratio of 2:1, ensuring a homogeneous distribution.

Materials Characterizations

The morphologies of the prepared electrocatalysts were characterized by cold field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, SU8220), transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL, JEM-2010). The high-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) images and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping images were recorded using a Talox F200X (Thermo Fisher Scientific, America). Atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM was acquired using an aberration-corrected JEM-ARM300F operated at 300 kV. Powder X-ray diffractor (XRD, TTR-III), X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS, Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi) with an X-ray source (Al Kα, hν = 1486.6 eV, all the peaks were calibrated with the C 1 s spectrum at a binding energy of 284.8 eV), synchrotron radiation X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and Raman spectrometer (LabRamHR) with a 532 nm excitation laser were performed to study the structures and chemical compositions of electrocatalysts. Inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (ICP AES, iCAP 7400) was conducted to determine the element ratios of the catalysts. UV visible photometer (UV-Vis, UV3600), nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR, AVAVCE III HD400 and JNM-ECZ600R/SI) and gas chromatograph (GC, GC7900) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector and TDX-01 column were used for products quantification.

Electrochemical Characterization

The electrochemical measurements were conducted at 25 °C using the CHI 660E electrochemical workstation, with continuous injection of CO2 into the electrolyzer or gas chamber during the electrocatalytic process. Data collection and processing were carried out using the Chi660e software. Furthermore, potentiostatic electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was utilized to quantify the resistance of the electrochemical cell, ranging from 0.1 Hz to 200 kHz with an applied signal amplitude of 10 mVpp. The pH value of the catholyte was measured using a precision pH meter, revealing that its pH remained consistently at 7.4 ± 0.3 throughout the testing process. Prior to commencing the tests, we prepared the electrolytes (with the precise concentration detailed below) utilizing an electronic scale, beaker, graduated cylinder, and volumetric flask. The mixture was then thoroughly stirred to ensure complete dissolution, achieving a homogeneous solution. Subsequently, it was carefully transferred into a sealed container and stored at ambient room temperature (25 °C) for subsequent experimental use. And the measurements were only performed once. Reference electrode calibration required the immersion of the reference electrode in a buffer solution (pH 7), alongside a glass electrode that had been rigorously calibrated. The open-circuit potential was subsequently measured with high accuracy using pH meter. Calibration was considered successful, and the reference electrode was deemed ready for use only if the deviation between the measured potential and the theoretical reference value (relative to the standard hydrogen electrode at 25°C with saturated KCl, SCE: +244 mV, Ag/AgCl: +199 mV) was less than 5 mV.

Electrochemical tests in an H-cell

The electrochemical tests in the H-cell were conducted using a three-electrode system, which was separated by a treated Nafion 117 membrane (size: 2 × 2 cm2, thickness: 183 μm). Before use, Nafion 117 membrane must undergo a pretreatment process: immerse it in a 5% hydrogen peroxide solution at 80 °C for 1 h; rinse it thoroughly with deionized water for 30 min; then soak it in a 5% sulfuric acid solution at 80 °C for 1 h; finally, wash it again with deionized water for 30 min. The catalyst (2 mg) was dispersed in 360 μL of mixture water and ethanol solution (Vwater: Vethanol = 1:1), along with 40 μL of Nafion (5 wt% aqueous solution), through sonication for 20 minutes to form a homogeneous ink. Then 100 μL of the catalyst ink was loaded onto carbon paper and naturally dried to obtain the working electrode. The geometric area of the working electrode was 1×1 cm2, with a catalyst loading of 0.5 mg·cm-2. The anode electrolyte was 0.5 M KHCO3 (35 mL), and a platinum plate electrode served as the counter electrode, while the cathode electrolyte (35 mL) for coupling reactions was CO2-saturated 0.5 M KHCO3 with 2000 ppm KNO3 (Ar-saturated electrolyte was composed of 0.5 M K2SO4 with 2000 ppm KNO3). Hg/Hg2Cl2 electrode containing saturated KCl solution was used as the reference electrode. To convert applied potentials to RHE reference scale, ERHE = ESCE + 0.0591×pH+0.241 formula was utilized, where the pH value was set to 7.4. Before conducting electrochemical tests, the cathode electrolyte was purged with CO2 for 30 min. Subsequently, linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) measurements were performed in CO2-saturated electrolyte with KNO3 at a sweep rate of 10 mV/s within the potential range of -0.5 V to -1.5 V (vs. SCE) for 20 min to ensure complete activation of the catalysts. Throughout all electrochemical tests, constant magnetic stirring and CO2 flow rate were maintained. Urea electrocatalytic synthesis was carried out via controlled potential electrolysis at various potentials for 1 h. The stability test involved continuous controlled potential electrolysis at an applied potential over multiple cycles, with each cycle lasting for 1 hour and refreshing the electrolyte at the beginning of each cycle. Additionally, isotope labeling experiments utilized K15NO3 as a replacement for K14NO3. The electrochemical active surface areas (ECSA) were estimated by calculating the double-layer capacitances (Cdl) from cyclic voltammograms (CV) at scan rates ranging from 40−140 mV/s in a solution of 0.5 M KHCO3 with 2000 ppm KNO3. The differences in current density (Δj = ja−jc) were plotted as a function of the scan rates, and it was determined that the linear slope corresponds to twice the value of Cdl. ECSAs were calculated using the following equation: ECSA = Cdl/Cs, where Cs was the smooth plane capacitance for metal surface (40 μF cm-2)36. The turnover frequency (TOF) of catalysts were calculated using the following formula: TOF = jurea / (16Fn), where jurea was the current density for urea synthesis (A cm-2), F was the Faraday constant (96485 C mol-1), and n was the number of moles of active sites (mol cm-2). CV measurements were conducted at a scan rate of 50 mV/s within the potential range of 0-0.5 V (vs. RHE) in a 0.5 M CO2-saturated KHCO3 solution containing 2000 ppm KNO3. The value of n was determined using: n = Qs / F, where Qs was the surface charge density (C cm-2). By integrating the charge of CV curves, Qs was obtained as half of the integrated value.

Electrochemical tests in a three-electrode flow cell

For the electrochemical tests in a three-electrode flow cell separated by an anion exchange membrane (size: 2 × 2 cm2, thickness: 100 μm), Ag67Cu33, Nickel foam, Ag/AgCl filled with saturated KCl were employed as the working, counter, and reference electrodes, respectively. Notably, the anion exchange membrane must be subjected to a pretreatment process, which involves sequentially immersing it in 1 M HCl for 1 h, followed by rinsing with deionized water until neutrality. Subsequently, it should be immersed in 1 M NaOH for 1 h, followed by a thorough rinse with deionized water. 4 mg of catalyst was dispersed in a mixture of 360 μL water and ethanol solution (Vwater: Vethanol = 1:4), along with 40 μL of Nafion (5 wt% aqueous solution). The working electrode (1 × 1 cm2), loaded with 1 mg·cm-2 was prepared following the same procedure as before. The anode electrolyte remained as 0.5 M KHCO3, but the cathode consisted of 0.5 M CO2-saturated KHCO3 with 0.5 M KNO3 (Ar-saturated electrolyte comprised of 0.5 M K2SO4 with 0.5 M KNO3). And electrolytes (35 mL) were continuously injected into their respective compartments during the electrocatalytic process using a peristaltic pump. The applied potentials were converted to the RHE reference scale by ERHE = EAg/AgCl + 0.0591×pH+0.197, where the pH value was 7.4. LSV measurements and controlled potential electrolysis remained consistent with those used in the H-cell. The long-term stability test consisted of continuous controlled-potential electrolysis under an applied potential for specific cycles; each cycle lasted 3 h and involved refreshing the electrolyte at the beginning of the cycle.

Electrochemical tests in a two-electrode flow cell

For the FOR/urea synthesis systems, Ag67Cu33 was utilized as the working electrode in both the cathode and anode of the two-electrode flow cell. Subsequently, 35 mL of 1 M KOH (with 0.6 M HCOH) and 35 ml of 0.5 M CO2-saturated KHCO3 (with 0.5 M KNO3) were introduced into the anode and cathode compartments at a flow rate of 16 rpm min-1 by a peristaltic pump, respectively, with separation provided by an anion exchange membrane (size: 2 × 2 cm2, thickness: 100 μm). A catalyst dispersion consisting of 4 mg dispersed in a mixture solution of water and ethanol (Vwater: Vethanol = 1:4), along with 40 μL of Nafion (5 wt% aqueous solution) was prepared. The working electrode (1 × 1 cm2) loaded with 0.5 mg·cm-2 was obtained using the same procedure as before. Subsequently, both the cathode and anode electrodes required full activation through LSV measurement in the H-cell using previously mentioned methods. Then LSV curves under different conditions in the two-electrode flow cell was measured from 0 V to 2 V at a sweep rate of 50 mV/s. The performance of Ag67Cu33 as a dual-function catalyst was evaluated through constant-current electrolysis at various current densities for 30 min. The cycling tests were conducted at 40 mA cm-2 by ten continuous electrocatalytic experiments, where each cycle lasted 1 h. Subsequently, a long-term stability test was carried out for 60 h at 40 mA cm-2, with the electrolyte being refreshed every 10 h. In all electrochemical tests, after each electrolysis cycle, the electrolytes in the anode and cathode compartments were completely removed via pumping and subsequently replaced with fresh electrolytes before initiating the next cycle.

In-situ Raman measurements

In-situ Raman spectroscopy measurements were conducted with a Renishaw inVia Confocal Raman Microscope equipped with a 532 nm laser (2.5 mW) and an 1800 lines/mm grating, using an Olympus 50X long working distance objective lens (N.A. = 0.5). The electrochemical cell (Supplementary Fig. 32) employed Ag67Cu33 (loaded on 1 × 1 cm2 carbon paper) as the working electrode, with Pt wire and Ag/AgCl serving as counter and reference electrodes, respectively. A CHI 660E electrochemical workstation controlled the system under CO2-saturated 0.5 M KHCO3 with 2000 ppm KNO3, with continuous injection of CO2 during the process. Initially, to simulate the activation process, time-dependent Raman spectroscopy measurements were conducted for 20 min using Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV). Subsequently, programmed applied potentials were applied for 300 seconds. Simultaneous spectral acquisition (100−1800 cm-1 range) was performed with 15 accumulations per spectrum to monitor any changes occurring within the catalyst material.

In-situ SR-FTIR measurements

In-situ SR-FTIR measurements were performed at National Synchrotron on Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) BL01B beamline using a test reflector with ZnSe window. The equipment setup integrated a KBr beam splitter-equipped FTIR spectrometer with liquid nitrogen-cooled MCT detectors, coupled to a Bruker Hyperion 2000 microscope with a × 15 magnifying objective lens. Initially, a micrometer-thick gap between the catalyst electrode and the ZnSe window allowed for reflection observation mode to precisely locate the sample’s surface. Subsequently, measurements were performed using vertically incident infrared light in reflection mode. Spectra were acquired with 128-scan averaging at 4 cm-1 resolution, when the source’s beam current exceeded 400 mA.

Background spectrum was first recorded at open circuit potential (OCP). Electrocatalytic measurements applied sequential potentials from -0.22 to -0.62 V vs. RHE (0.1 V increments) and maintained for 200 s. Importantly, the instrument would automatically subtract OCP-derived backgrounds from test results.

Product quantification

The liquid product analysis employed UV-vis spectrophotometry and 1H NMR spectroscopy, while gas-phase quantification was conducted via GC. The specific detection methods are detailed as follows:

Determination of urea

The urea products were determined using the diacetyl monoxime method. Firstly, 60 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid and 20 mL of concentrated phosphoric acid were slowly added to 120 mL of deionized water. Then 33 mg of FeCl3·6H2O was added and the solution was stirred to form a homogeneous solution (Solution A). Secondly, 500 mg of diacetyl monooxime (DAMO) and 10 mg of thiosemicarbazide (MTSC) were dissolved in 100 mL of deionized water to create a uniform solution (Solution B). Thirdly, 950 μL of deionized water, 50 μL of electrolyte, 2 mL of Solution A and 1 mL of Solution B were sequentially added into a glass bottle. The covered glass bottle containing the mixed solution was then heated to 100 °C for 30 min. After cooling down to 25 °C, the absorbance at 525 nm was measured. Notably, the electrolytes in the H-cell were measured directly, whereas the electrolytes in the flow cells were analyzed following appropriate dilution (350 µL of electrolyte diluted to a final volume of 950 µL) to ensure the concentrations fell within the standard curve range. The principle and standard curves of diacetyl monoxime method were shown in Supplementary Fig. 25.

The equation of urea yield rate and Faradic efficiency:

where Curea = generated urea concentration, V = electrolyte volume, t = reaction time, m = catalyst mass, F = Faraday constant (96485.34) and Q = applied electric quantity.

Determination of NH3-N

Ammonia (NH3) concentration was determined using Nessler’s reagent spectrophotometry. Briefly, 1 g of potassium sodium tartrate (C4H4KNaO6) was dissolved in 2 mL of deionized water to form homogeneous solution. Then 4.9 mL of deionized water, 100 μL of electrolyte, 0.1 mL of potassium sodium tartrate solution and 0.1 mL of Nessler reagent were added to a glass bottle, respectively. Keeping the mixture at 25 °C for 20 min, its absorbance was then measured at a wavelength of 420 nm, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 27. The equation for the Faradic efficiency of NH3 was as follows:

where CNH3 = generated NH3 concentration, V = electrolyte volume, F = Faraday constant (96485.34) and Q = applied electric quantity.

Determination of NO2 --N

Nitrite (NO2-) was detected via N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (NETH) spectrophotometric method. The chromogenic reagent was prepared by dissolving 0.4 g of sulfanilamide, 0.02 g of NETH and 1 mL phosphoric acid (ρ = 1.70 g·mL-1) in 5 mL of deionized water. Then a mixture comprising 4.9 mL of deionized water, 100 μL of a 1:10 diluted electrolyte solution, and 0.1 mL of chromogenic reagent was prepared in a glass bottle and kept at 25 °C for 20 min. The UV-Vis absorption spectra were obtained at a wavelength of 540 nm, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 28. The equation for the Faradic efficiency of NO2-:

where CNO2- = generated NO2- concentration, V = electrolyte volume, F = Faraday constant (96485.34) and Q = applied electric quantity.

Determination of HCOOH and CH3OH

The identification and quantification of formic acid (HCOOH) and methyl alcohol (CH3OH) were performed using 1H NMR spectroscopy. A mixture containing 300 μL of electrolyte, 200 μL of D2O and 100 μL of DMSO (used as an internal standard) was thoroughly blended and subsequently analyzed using the Ascend 400 NMR spectrometer with accumulating 16 scans, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 30. In view of the disproportionation reaction of HCOH (Cannizzaro Reaction, 2HCHO + OH- → CH3OH + HCOO-) occurring in the presence of OH-, which resulted in the spontaneous formation of HCOOH, the concentration of HCOOH generated through the Ag67Cu33-catalyzed FOR at the anode was calculated using the following formula:

where CHCOOH-t and CCH3OH-t represented the concentrations of HCOOH and CH3OH in the post-electrolyte as determined by 1H NMR analysis, and CCH3OH-0 denoted the initial concentration of CH3OH in a 0.6 M HCOH solution (without any treatment). By quantifying the amount of CH3OH generated, we could deduce the quantity of HCOOH formed via the spontaneous decomposition of HCOH based on the chemical equation, which allowed for the accurate calculation of the HCOOH produced via the FOR process catalyzed by Ag67Cu33. Notably, commercial HCOH solutions inherently contained a predetermined concentration of CH3OH to inhibit the spontaneous polymerization of HCOH, which must be measured beforehand.

Subsequently, the yield rate and Faradaic efficiency of HCOOH achieved using the Ag67Cu33 catalyst via the FOR process were calculated based on the following equations:

where CHCOOH represented the concentration of HCOOH produced by Ag67Cu33 catalyst at the anode, V denoted the volume of the electrolyte solution, t indicated the reaction time, m referred to the mass of the catalyst, F was the Faraday constant (96485.34), and Q signified the applied electrical charge.

Determination of H2 and CO

Gas-phase products (H2, CO) were analyzed using GC employing high-purity N2 as the carrier gas, with quantification based on calibration-derived conversion factors from standard reference gases (Supplementary Fig. 29). The equation for the Faradic efficiency of H2 and CO:

where CH2 = generated H2 concentration, CCO = generated CO concentration, V = total volume of the collected gas, F = Faraday constant (96485.34) and Q = applied electric quantity.

1H NMR method and 15N isotope-labeling experiment

The quantification and identification of urea were accomplished via 1H NMR method and 15N isotope-labeling experiment, respectively. For 1H NMR analysis, 400 μL post-test electrolyte (−0.52 V vs. RHE) was mixed with 200 μL dimethylsulfoxide-d6 (internal standard), and analyzed on an Ascend 600 NMR spectrometer (accumulation of 512 scans). Additionally, various concentrations of 14NH2CO14NH2 mixed uniformly with 200 μL dimethylsulfoxide-d6 were used to construct a standard curve for urea quantification. For the 15N isotope-labeling experiment, CO2-saturated electrolyte with 2000 ppm 15KNO3 was utilized, followed by collecting post-test electrolyte at -0.52 V vs. RHE. The isotope-labeled products were detected through the aforementioned 1H NMR method, with 15NH2CO15NH2 solutions serving as isotopic reference.

Computational detail

All calculations in this study were performed using the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP) based on density functional theory (DFT)52. Projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials and the semi-local generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional were employed53. An empirical dispersion-corrected DFT method (DFT-D3) was applied to accurately describe weak long-range van der Waals (vdW) interactions54. The kinetic energy cutoff for the plane-wave expansion was set to 500 eV, and the convergence threshold for the self-consistent field (SCF) iteration was set to 10-5 eV. Geometry optimization was performed using the conjugate gradient method, with forces on each atom being less than 0.03 eV Å-1. A 1 × 1 × 1 Gamma k-point mesh was used for k-space integration. For the adsorption model, a vacuum region of approximately 25 Å was added between slabs to prevent interaction between periodic images.

For the Cu(111) and Ag(111) models, 4 × 4 supercells with 4 atomic layers were used and two bottom layers were fixed. To simulate the interface between Ag(111) and Cu(111), a heterojunction structure of AgCu(111) was constructed, consisting of a (3 × 7) Ag(111) supercell with 4 atomic layers and a (3 × 8) Cu(111) supercell with 4 atomic layers. After fixing the z-axis to optimize the lattice and atomic coordinates, the resulting configuration was considered the final structure of the AgCu(111) model, which was then used to study its C-N coupling properties.

To investigate the effect of electrode potential on the C-N coupling process, the CP-VASP code55,56was employed, with an external potential of -0.96 V (vs. SHE) and a pH of 7.4. Using the conversion relationship between RHE and SHE, the potential relative to RHE was calculated to be -0.52 V, which aligned with the voltage used in the experiment. Since the TARGETMU value corresponding to the vacuum level was -4.57, the applied voltage and pH conditions led to setting TARGETMU to -3.61, and FERMICONVERGE was set to 0.01.

Implicit solvation was treated using VASPsol + +57, which incorporated water solvation in a self-consistent continuous model. The relative permittivity was set to 78.4 to simulate the water electrolyte. The relationship between the Fermi level (EF) and the corresponding electrode potential, referenced to the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) scale U (V vs. SHE), was formulated as follows:

The grand canonical energy (GCE) was calculated using the formula below:

where E0 was the standard VASP output energy, CNNE was the charge-neutral electron number, n was the electron number, and U was the external electrode potential. The grand canonical energy (GCE) was expressed in terms of eV. Note that E0 did not account for changes in the electron number and was no longer an accurate representation of the system’s total energy.

The change in reaction free energy could be obtained using the following equation:

where ΔGCE was the total grand canonical energy difference before and after intermediate adsorption, ΔZPE represented the difference in zero-point energy, ΔS was the difference in entropy, kB was the Boltzmann constant, and T was the temperature, taken as 298.15 K. n1 was the number of proton transfers involved in the corresponding step, and n2 referred to the number of electron transfers. The pH value used in this study was set to 7.4, and USHE was -0.96 V. The zero-point energy and entropy of free molecules and adsorbates were obtained from vibrational frequency calculations. Since VASP could not accurately describe charged systems, the energy of NO3- needed to be measured according to this literature58.

Data availability

The raw data of the figures in the main manuscript have been deposited in the figshare with the identifier https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28705160.v2. The theoretical calculations including detailed CONTCAR files for catalysts and adsorbed intermediates have been deposited in the figshare with the identifier https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28636625.v2. Additional data related to this work can be requested from the authors.

References

Chen, C. et al. Coupling N2 and CO2 in H2O to synthesize urea under ambient conditions. Nat. Chem. 12, 717–724 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. High C-selectivity for urea synthesis through O-philic adsorption to form *OCO intermediate on Ti-MOF based electrocatalysts. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2400892 (2024).

Liu, C., Gao, Y. & Zhang, B. Organonitrogen electrosynthesis from CO2 and nitrogenous sources in water. Nat. Synthesis 3, 794–796 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Electrocatalytic synthesis of C-N coupling compounds from CO2 and nitrogenous species. SusMat 4, e193 (2024).

Wei, X. et al. Dynamic reconstitution between copper single atoms and clusters for electrocatalytic urea synthesis. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300020 (2023).

Xiong, H. et al. Urea synthesis via electrocatalytic oxidative coupling of CO with NH3 on Pt. Nat. Catal. 7, 785–795 (2024).

Lv, C. et al. Selective electrocatalytic synthesis of urea with nitrate and carbon dioxide. Nat. Sustain. 4, 868–876 (2021).

Fan, X. et al. Efficient electrochemical Co-reduction of carbon dioxide and nitrate to urea with high faradaic efficiency on cobalt-based dual-sites. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401221 (2024).

Shibata, M., Yoshida, K. & Furuya, N. Electrochemical synthesis of urea on reduction of carbon dioxide with nitrate and nitrite ions using Cu-loaded gas-diffusion electrode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 387, 143–145 (1995).

Wei, X. et al. Oxygen vacancy-mediated selective C-N coupling toward electrocatalytic urea synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 11530–11535 (2022).

Qiu, X.-F., Huang, J.-R., Yu, C., Chen, X.-M. & Liao, P.-Q. Highly efficient electrosynthesis of urea from CO2 and nitrate by a metal-organic framework with dual active sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202410625 (2024).

Hu, Q. et al. Pulsed co-electrolysis of carbon dioxide and nitrate for sustainable urea synthesis. Nat. Sustain. 7, 442–451 (2024).

Xiao, C. & Zhang, J. Architectural design for enhanced C2 product selectivity in electrochemical CO2 reduction using Cu-based catalysts: a review. ACS Nano 15, 7975–8000 (2021).

Gao, W. et al. Alloying of Cu with Ru enabling the relay catalysis for reduction of nitrate to ammonia. Adv. Mater. 35, 2202952 (2023).

Wang, P. et al. Sub-1 nm Cu2O nanosheets for the electrochemical CO2 reduction and valence state-activity relationship. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 26133–26143 (2023).

Wang, Y., Zhou, W., Jia, R., Yu, Y. & Zhang, B. Unveiling the activity origin of a copper-based electrocatalyst for selective nitrate reduction to ammonia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 5350–5354 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Ligand engineering towards electrocatalytic urea synthesis on a molecular catalyst. Nat. Commun. 15, 8858 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Low-coordinated copper facilitates the *CH2CO affinity at enhanced rectifying interface of Cu/Cu2O for efficient CO2-to-multicarbon alcohols conversion. Nat. Commun. 15, 5172 (2024).

Lv, X. et al. Electron-deficient Cu sites on Cu3Ag1 catalyst promoting CO2 electroreduction to alcohols. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001987 (2020).

Gu, Z. et al. Intermediates regulation via electron-deficient Cu sites for selective nitrate-to-ammonia electroreduction. Adv. Mater. 35, 2303107 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Modulating the localized electronic distribution of Cu species during reconstruction for enhanced electrochemical CO2 reduction to C2+ products. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 15082–15089 (2024).

Zhou, J. et al. Achieving efficient and stable electrochemical nitrate removal by in-situ reconstruction of Cu2O/Cu electroactive nanocatalysts on Cu foam. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 317, 121811 (2022).

Li, Y., Zhang, J., Chen, Q., Xia, X. & Chen, M. Emerging of heterostructure materials in energy storage: a review. Adv. Mater. 33, 2100855 (2021).

Xu, D., Zhang, S.-N., Chen, J.-S. & Li, X.-H. Design of the synergistic rectifying interfaces in mott–schottky catalysts. Chem. Rev. 123, 1–30 (2023).

Wu, Z. et al. Engineering bismuth–tin interface in bimetallic aerogel with a 3D porous structure for highly selective electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to HCOOH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 12554–12559 (2021).

Abdinejad, M. et al. Capture and electroreduction of CO2 using highly efficient bimetallic Pd–Ag aerogels paired with carbon nanotubes. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 12870–12877 (2021).

Jiang, X., Du, R., Hübner, R., Hu, Y. & Eychmüller, A. A roadmap for 3D metal aerogels: materials design and application attempts. Matter 4, 54–94 (2021).

Huang, J., Mensi, M., Oveisi, E., Mantella, V. & Buonsanti, R. Structural sensitivities in bimetallic catalysts for electrochemical co2 reduction revealed by Ag-Cu nanodimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2490–2499 (2019).

Clark, E. L., Hahn, C., Jaramillo, T. F. & Bell, A. T. Electrochemical CO2 reduction over compressively strained CuAg surface alloys with enhanced multi-carbon oxygenate selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 15848–15857 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Weak CO binding sites induced by Cu-Ag interfaces promote CO electroreduction to multi-carbon liquid products. Nat. Commun. 14, 698 (2023).

Zhou, M. et al. High-performance Ag-Cu nanoalloy catalyst for the selective catalytic oxidation of ammonia. ACS. Appl. Mater. & Inter. 11, 46875–46885 (2019).

Dou, Q., Li, Y., Wong, K. W. & Ng, K. M. Facile synthesis of nearly monodisperse AgCu alloy nanoparticles with synergistic effect against oxidation and electromigration. J. Mater. Res. 34, 2095–2104 (2019).

Zhang, B. et al. Defect-induced triple synergistic modulation in copper for superior electrochemical ammonia production across broad nitrate concentrations. Nat. Commun. 15, 2816 (2024).

Lei, Q. et al. Investigating the origin of ehanced C2+ selectivity in oxide-/hydroxide-derived copper electrodes during CO2 electroreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 4213–4222 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 toward C2 valuables on Cu@Ag core-shell tandem catalyst with tunable shell thickness. Small 17, 2102293 (2021).

Wei, D. et al. Decrypting the controlled product selectivity over ag-cu bimetallic surface alloys for electrochemical CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217369 (2023).

Cheng, M. et al. Rectifying heterointerface facilitated C-N coupling dynamics enables efficient urea electrosynthesis under ultralow potentials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202413534 (2024).

Sun, W. et al. V-doped Cu2Se hierarchical nanotubes enabling flow-cell CO2 electroreduction to ethanol with high efficiency and selectivity. Adv. Mater. 34, 2207691 (2022).

Li, M., Wang, T., Zhao, W., Wang, S. & Zou, Y. A pair-electrosynthesis for formate at ultra-low voltage via coupling of CO2 reduction and formaldehyde oxidation. Nano Micro Letters 14, 211 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Photoelectrocatalytic synthesis of urea from carbon dioxide and nitrate over a Cu2O photocathode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202406515 (2024).

Gao, X. et al. Intermediate-regulated dynamic restructuring at Ag-Cu biphasic interface enables selective CO2 electroreduction to C2+ fuels. Nat. Commun. 15, 10331 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Identifying and tailoring C-N coupling site for efficient urea synthesis over diatomic Fe-Ni catalyst. Nat. Commun. 13, 5337 (2022).

Keuleers, R., Desseyn, H. O., Rousseau, B. & Van Alsenoy, C. Vibrational analysis of urea. J. Phys. Chem. A 103, 4621–4630 (1999).

Gao, Y. et al. Tandem catalysts enabling efficient C-N coupling toward the electrosynthesis of urea. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202402215 (2024).

Bouilloud, M. et al. Bibliographic review and new measurements of the infrared band strengths of pure molecules at 25 K: H2O, CO2, CO, CH4, NH3, CH3OH, HCOOH and H2CO. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 451, 2145–2160 (2015).

Zhang, G. et al. Tandem electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia on MBenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202300054 (2023).

Hadjiivanov, K. I. Identification of neutral and charged NxOy surface species by IR spectroscopy. Catal. Rev. 42, 71–144 (2000).

Firet, N. J. & Smith, W. A. Probing the reaction mechanism of CO2 electroreduction over ag films via operando infrared spectroscopy. ACS Catal. 7, 606–612 (2017).

Wei, C. et al. Surface composition dependent ligand effect in tuning the activity of nickel-copper bimetallic electrocatalysts toward hydrogen evolution in alkaline. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 7765–7775 (2020).

Li, G. et al. Dual hydrogen production from electrocatalytic water reduction coupled with formaldehyde oxidation via a copper-silver electrocatalyst. Nat. Commun. 14, 525 (2023).

An, S. et al. Multi-functional formaldehyde-nitrate batteries for wastewater refining, electricity generation, and production of ammonia and formate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318989 (2024).

Hafner, J. Ab-initio simulations of materials using VASP: Density-functional theory and beyond. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 2044–2078 (2008).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

S. Grimme, J. Antony, S. Ehrlich, H. Krieg. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Zhao, X. & Liu, Y. Origin of selective production of hydrogen peroxide by electrochemical oxygen reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 9423–9428 (2021).

Yu, S., Levell, Z., Jiang, Z., Zhao, X. & Liu, Y. What is the rate-Limiting step of oxygen reduction reaction on Fe-N-C catalysts?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 25352–25356 (2023).

S. M. R. Islam, F. Khezeli, S. Ringe, C. Plaisance. An implicit electrolyte model for plane wave density functional theory exhibiting nonlinear response and a nonlocal cavity definition. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 234117 (2023).

Niu, H. et al. Theoretical insights into the mechanism of selective nitrate-to-ammonia electroreduction on single-atom catalysts. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2008533 (2021).

Acknowledgements

G.Q. Z. acknowledges the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52472262). The numerical calculations in this work have been done in the Supercomputing Center of University of Science and Technology of China. The authors are grateful to the infrared beamline (BL01B) in National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) for the experimental beamtime support, and to the BL10B beamline in NSRL for the support provided for the characterization experiments using Synchrotron Radiation. This work was partially carried out at the Instruments Center for Physical Science, University of Science and Technology of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceiving the idea: G. Q. Zhang and F. Q. Huang. Supervision: G. Q. Zhang. Conducting the project: P. Feng. DFT calculations: S. Wang and Y. Chen. Characterization and analysis of spherical aberration corrected HADDF-STEM: J. Xia. Materials synthesis and electrochemical tests: B. Zhang and B. Ke. Characterization and data processing: Z. Dai and M. Cheng. Writing the manuscript: G. Q. Zhang and F. Q. Huang. P. Feng, S. Wang, Z. Dai contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations