Abstract

Single-pixel microscopy is a computational imaging approach that produce images with a bucket detector by illuminating the sample with a sequence of micro-structured light patterns. In particular, Hadamard-based single-pixel microscopy (HSPM) is a leading implementation that uses Hadamard-basis patterns typically encoded on a digital-micromirror-device (DMD). Ultimate image quality and resolution depend on accurate demagnification of the patterns onto the sample, often requiring subwavelength projection resolution. However, aberrations introduced by DMDs, which are designed for consumer displays, together with sample scattering, constrain the HSPM maximum achievable performance under practical imaging conditions. In this work, the aberrations effects on HSPM are addressed, both theoretically and experimentally, thereby enabling HSPM near-diffraction-limited operation. The use of a multi-actuator adaptive lens to correct the aberrations effect on the projected patterns in HSPM is reported. A sensor-less method is developed to achieve aberration-free HSPM, leveraging direct frequency information from the sample Hadamard spectrum in a reconstruction-free approach. The proposed method is validated by correcting not only optical system but also sample’s induced aberrations, achieving near-diffraction-limit resolution. Consolidating the presented work as a framework that could play a major role in the development of single-pixel microscopy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Active single-pixel microscopy (SPM) profiles a versatile emerging imaging technique1,2,3,4,5. Unlike conventional imaging systems, in SPM, a scanning basis is projected over the sample using a spatial light modulator (SLM). This process is often performed by employing high-speed digital micromirror devices (DMD), due to their achievable frame rates and wide spectral range6,7. The technique adaptability has attracted attention across applications8,9,10, ranging from polarization state studies11 to imaging outside the visible spectrum, covering wavelengths from terahertz12 to X-ray regions13,14. Between the multiple alternatives for the SPM sampling, deterministic approaches like Hadamard-based, and Fourier-based SPM have been broadly implemented15,16,17. The performance under noise and low intensity sensing conditions15 profiles the Hadamard approach as a suitable implementation for microscopy techniques, where the signals are often weak intensity and sensible to environmental variations.

In Hadamard-based single-pixel microscopy (HSPM), a set of patterns of the Hadamard basis, the rows in Fig. 1a, is projected over the sample as two-dimensional rectangular functions, as shown in panel (b). As is illustrated in panel (c), the pointwise product between each Hadamard pattern\(\,{H}_{k}\left(x,y\right)\) and the sample \(s(x,y)\) is integrated by a bucket detector, generating an intensity vector \({I}_{v}(k)\). The operation can be written as \({I}_{v}=H(s)\), being \(H\left(\cdot \right)\) the Hadamard transform. The collected intensity vector contains the Hadamard frequency spectrum (HS) of the imaged sample. This intensity vector can be reshaped onto the Walsh order or the 2D representation16, as seen in panel (d), to define a more interpretable representation of the HS. The coordinates\(\,{f}_{x},{f}_{y}\) are determined by the frequency of the rectangular waves that compose the Hadamard basis. The maximum available frequency for each axis corresponds to \(M/(n\Delta )\), where \({n}\) is the binning factor, corresponding to the number of the DMD pixels used to codify a pixel from the Hadamard patterns along each axis, \(\Delta\) is the DMD square pixel pitch, and M is the magnification of the microscope system. After the full spectrum is recovered, the sample image can be obtained just by applying the inverse Hadamard transform \({H}^{-1}\left(\cdot \right)\), as seen in panel (e).

Each pattern of the Hadamard basis (a), is projected over the sample in 2D form (b), to create an intensity vector (c), that can be reshaped onto an interpretable representation using the Walsh 2D order as it is shown in (d). The image is then recovered by applying the inverse Hadamard Transform \(H-1\), as shown in (e). Panel (b) CAD render based on Thorlabs, Inc., RMS20X-PF model available via manufacturer website (https://www.thorlabs.com/).

The spatial resolution in HSPM is dictated by the maximum between the geometrical demagnification and the optical system resolution. The geometrical limit, \(\Delta {r}_{{geo}}=(n\Delta )/M\), is given by the size of the smaller pixel of the projected Hadamard pattern, demagnified by the optical system. The diffraction resolution limit is given by the well-known Abbe criteria \(\Delta {r}_{{dif}}=0.5\lambda /{NA}\), where \(\lambda\) is the illumination wavelength, and \({NA}\) is the numerical aperture of the system. If binning factor \(n\ge 2\), typically \({\Delta r}_{{geo}}\gg {\Delta r}_{{dif}}\), under this scenario the light patterns are projected correctly, the field of view is larger since the pattern size is binned. Nevertheless, the system is not limited by diffraction and the image spatial resolution is reduced times the binning factor. If \({\Delta r}_{{geo}}\ll {\Delta r}_{{dif}}\), the higher frequency content of the patterns won’t be correctly projected over the sample plane due to the diffraction limitation of the system. If this is the case, the blurred patterns projected over the sample plane would compromise the measurement, jeopardizing the image quality17,18 and the capability of resolve objects due to an unproper pattern projection. When both resolutions are closely the same, we have a good compromise between field of view and spatial resolution. However, the patterns will be affected not only by the diffraction limit of the imaging system, but also by the DMD induced aberrations19,20,21,22. In this work we propose the introduction of recently developed plug and play adaptive optical elements23 combined with a wavefront sensor-less approach to reach optimized efficiency in HSPM and to remove the presence of the DMD aberration effects.

The use of deformable lenses24 is chosen over traditionally implemented deformable mirrors and phase only SLMs. The latter two operate in a reflective manner, demanding the use of additional optical elements. Further, phase-only SLM devices are constrained by their response time, polarization dependence, and reflectance. By contrast, deformable lenses, capable of correcting aberrations up to the 4th order of Zernike polynomials, offer a streamlined solution with straightforward integration into existing microscope system25. The presented work not only addresses, the detrimental effects of DMD-induced aberrations in HSPM but also lays the groundwork for a broader implementation of adaptive optics (AO) in single-pixel microscopy systems. By doing so, it establishes a versatile and practical framework that enhances imaging performance and sets the stage for further advancements in the field.

The pattern blur is typically avoided in most of the HSPM just by binning the patterns by a factor \(n\) bigger than 2, compromising \(\Delta {r}_{{geo}}\) to deal with the unfavorable projection conditions2,26,27,28,29. An ideal HSPM system should be designed to take the maximum advantage of the available DMD spatial sampling. That will configure a scenario where \({\Delta r}_{{geo}}\cong {\Delta r}_{{dif}}\). To reach the above-mentioned condition the binning factor should be avoided and each pixel \(\Delta\), typically around 10 \(\mu m\) must be demagnified over the sample according to the system magnification, \(M.\) For example, a 20X magnification requires the patterns to be projected with a subperiod around 0.5 μm. However, under the above imaging conditions, the high frequency patterns will be modulated not only by the system diffraction but by the DMD aberrations itself. DMD aberrations have been recently studied and reported for different applications19,20,21. They should be taken into account particularly when the codified patterns are closely reaching the wavelength value20. This is not the case of the commonly reported binned patterns implemented in SPM, where the final spatial resolution is so strongly limited by the geometrical resolution that the aberration effect over the reconstruction is negligible. A similar scenario is found over Fourier based SPM approaches where spatial dithering is applied at expense of the system resolution26.

In such manner, for a HSPM pattern \({H}_{k}\) projected over the sample in conditions near to the resolution limit, the sample will be scanned by a aberrated demagnified pattern \({\check{H}}_{k}\), as described in Eq. (1) due to the DMD induced aberrations,

where \(\widetilde{p}(\cdot )\) represents the Fourier transform of the pupil function \({p}(\cdot )\) that carries DMD induced aberrations. This is critical, since sampling with these aberrated patterns leads onto an equally aberrated recovered image of the sample. This can be easily demonstrated, as it is illustrated in Eq. (2) using 1D functions for simplicity. In the equation is described that the integration of the pointwise product of a sample \(s(y)\) scanned by an aberrated pattern \({H}_{k}\) is completely analogue to scan with a perfect pattern but having an aberrated sample by the conjugated of the original pupil.

From this description one can see that any DMD induced aberration will produce an equally aberrated image. As well one can conclude that is possible to correct the sample aberrations just by modifying the pupil plane in the DMD projection system. In the following sections, firstly the DMD aberrations will be identified and corrected with a deformable lens and, second, a method to correct them automatically will be described.

Results and discussions

Aberration effects in HSPM

In recent literature, DMD induced aberrations are found to be primarily astigmatic21 and have been identified especially for the tilting DMD axis, as detailed by Lee et al.19. Additionally, Popoff et al.20,22 observed the existence of other significant DMD induced aberrations that should be considered, especially for wavefront shaping applications. To correct these aberration effects in HSPM, we propose the use of a multi-actuator adaptive lens (M-AL)30. M-ALs are plug-and-play transmissive active optical elements that modulate specific wavefronts by independently adjusting Zernike coefficients, \({C}_{j}\). for each Zernike polynomial, \({Z}_{j}\)23,30,31. Therefore, the DMD induced aberrations can be minimized in the system by introducing a phase function

at the pupil aperture of the optical system. The implemented M-AL in this work was provided by CNR-IFN and manufactured by Dynamic Optics srl, Italy. In reviewing the literature, this paper shows the earliest use of a transmissive multi-actuator adaptive lens (M-AL) in DMD-based HSPM, placing the M-AL at projection pupil plane for correction of both optical systema and specimen induced aberrations.

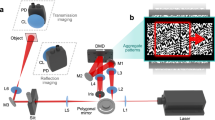

The experimental setup schematic used to validate and correct the aberrations effects in HSPM is illustrated in Fig. 2. In panel (a) a render of the system shows in zoomed inset the M-AL location, as well a detailed schematic of the built HSPM is shown in panel (b).

In (a) a render of the implemented HSPM is shown, the M-AL, detailed in the yellow zoomed inset is placed into the imaging system conjugated aperture plane. In (b), adapted from Ref32, a detailed schematic of the optical set-up is provided, the built system is configured by the imaging modules, the illumination coupling module M-Ⓐ ensures the DMD incident angle, the projection module M-Ⓑ configures the microscope setup needed to demagnify the encoded Hadamard patterns on the DMD over the sample plane, finally the reflection module M-Ⓒ ensures a proper collection of the scattered light by the sample. A detailed list of materials and step by step construction of the implemented HSPM can be found. The detailed element in the schematics corresponds to Api aperture ith, Mi mirror ith, Li lens ith, M-AL Deformable lens, FD field diaphragm, TLi tube lens ith, BSi beam splitter ith, MOi microscope objective ith, BD bucket detector.

The HSPM system was built following the detailed guide presented in Ref. 32 ensuring a telecentric configuration to avoid any presence of parabolic aberrations related to optical set-up. The implemented HSPM is configured by three modules, illumination alignment module M-Ⓐ, projection module M-Ⓑ and reflected-light collection module M-Ⓒ, which are described in the methods section alongside all the HSPM setup detailed information. Using the module M-Ⓐ, the light from a 650 nm diode is reflected by a Vialux V-650L DMD which encode the patterns. The M-AL lens is then introduced at the aperture plane of the optical system to directly compensate for any DMD induced aberration by adjusting the lens induced wavefront. Details about the implemented M-AL and its operational characteristics can be found in the attached supplementary file. Once modified by the M-AL induced wavefront, the patterns projected over the sample using M-Ⓑ interact with the sample. Then the light reflected by the sample is measured by the bucket detector using collection module M-Ⓒ. The bucket detector refers to an avalanche photodiode (APD410A/M), and its voltage signal is digitalized using a NI-DAQ USB 6341 at an acquisition rate of 300k samples per second. The DMD speed was set to 10 kHz.

Once the system is built, the first step in aberration correction was to measure the DMD aberrations using a Dynamic Optics Shack-Hartman wavefront sensor (WFS). The WFS can be completed outside of the HSPM setup to measure the wavefront illumination modifications due to the DMD using the micromirrors off-state33. A comparison between our measured values and those reported in Ref. 22 are presented in Fig. 3. As expected, the values follow a similar trend, and astigmatism is the leading contributor. This is in agreement with previously mentioned works19,21,22 while different higher order aberrations persist with a lower contribution.

Literature reported DMD induced aberrations22 are presented in blue vs the measured induced aberrations by our DMD presented in orange. \({Zj}\) are numbered in Noll order. Additionally, a normalized phase map of the corresponding wavefront is presented for both the literature and the measured aberrations.

Knowing the exact value of the DMD induced aberrations one can correct them by using the M-AL. In Fig. 4 we show the HSPM image of a high-resolution chart using the proposed system with and without aberration compensation. Both HSPM images utilize the DMD without binning. Each pixel of the DMD was projected over the sample plane with a size of approximately\(\,0.55\,\mu m\). Resulting in a scenario where the geometric limit \({\Delta r}_{{geo}}\) = 0.55 \(\mu m\) is smaller than the diffraction limit \({\Delta r}_{{diff}}=0.75\,\mu m\). Ideally, when reaching sampling limit under a no binning approach, the high frequency patterns are only modulated by the system diffraction limit. However, the DMD induced aberration effects over the projected patterns will be seen over the Hadamard basis.

In the described experiment, the initial HSPM image is shown in in Fig. 4a. The image inherits the effect of the DMD induced aberrations, as described in Eq. (2). Since astigmatism in the y-axis is the biggest contributor, a notable blur in this direction is observed in the recovered image. Panel (b) shows the corresponding HSPM reconstruction with the measured aberrations compensated, by introducing the conjugate field using the M-AL. The blur reduction and the image contrast enhancement are visible immediately. Validating the feasibility of the proposed correction just by implementing a versatile plug and play transmissive adaptive optics element. Our proposal minimizes the incorporation of additional optical elements such as the one required by SLM’s23,24,34 and take advantage of the M-AL versatility. Regardless the M-AL lens control the Zernike values can be set one by one using the corresponding software or by implementing an USB communication protocol using the corresponding drivers.

Automatic wavefront sensor-less approach

Despite the noticeable improvement in recovered image quality when only correcting the DMD aberrations, the optical system and the sample itself introduce different aberrations. A search of the literature revealed for HSPM the only addressed aberration in the technique has been defocus17,18. To avoid incorporation of a WFS or other phase measurement device to measure both the DMD and sample induced aberrations, one can take advantage of the direct access of the sample frequency information acquired in the Hadamard spectrum (HS). As well as it happens in conventional image systems with the Fourier spectrum (FS)35,36, the HS frequency content will be the maximum when the aberration presence is the minimum18,37. Any aberration presence in the system will impact directly in the measured HS frequency components. Wavefront sensor-less aberration (WSL) correction approaches commonly take advantage of this relation23,34,38, by iteratively modifying the introduced correction wavefront and computing different merit functions over the captured spectrum of the sample under study. This implies that, typically, an image must be captured and then processed. However, in HSPM we are directly measuring the frequency content of the imaged sample in the Hadamard basis16. This releases the need to recover a complete image to generate a descriptor based on the frequency content for induced aberration value. Several studies have recently illustrated the use of this relation for the correction of defocus in SPM [16,17]. Based on these recent discoveries, a merit function over an intermediate frequency region of interest (ROI) was used as a descriptor of the aberrations presence in the system. We implement a function similar to that reported in18 for defocusing correction, detailed in Eq. (4).

In this way, the sum of the absolute value (ABS) of the imaged sample HS, over the ROI encircled in area defined by \({\frac{1}{4}f}_{\max }\le \,\root{2}\of{{({f}_{x}-({\frac{1}{4}f}_{\max }))}^{2}+{({f}_{y}-({\frac{1}{4}f}_{\max }))}^{2}}\), will reach its maximum when the aberration presence in the system reaches its minimum. This allows computation of the merit function without actually retrieving any image, alternatively, sampling around the 5% of the HS. A detailed description of the sensorless algorithm can be found in supplementary note 4. To perform the WSL correction, we propose an automatic iterative approach as it is detailed in the flow chart, Fig. 5. Firstly, a random value near to zero is set for all the aberrations \({Z}_{n}\) to be corrected using the M-AL. This ensures that the lens itself is not introducing any aberration to the pattern or to the system itself. Then we start to compute the merit function for each \({Z}_{n}\), scanning the available coefficient \({C}_{j}\) values for each independent \({Z}_{j}\) introduced by the lens. The range for each \({Z}_{j}\) depends on the M-AL achievable ranges, and is reduced for higher aberration orders which do not have a significant contribution in our case. Once the range is measured for each \({Z}_{j}\), the \({C}_{j}\) value where Eq. (4) reaches its maximum is set. This approach takes advantage of the possibility of independently adding any desired aberration using M-AL.

This methodology has been shown to be more efficient than trying to apply iterative algorithms, due to the possibility of finding an optimal maximum just by scanning 15 points over the dynamic range for each aberration allowed by the lens. However, a second iteration around the initial solutions can be applied to ensure a more optimal value. A detailed comparison in terms of time between an iterative method and the proposed sensor-less approach can be found in supplementary file. To test the proposed method, the sample was slightly defocused using a translation stage to induce not only the DMD aberrations but also a slight defocus. In Fig. 6 the results of applying the proposed correction routine for the first order aberration, \({Z}_{3}\) to \({Z}_{5}\), are shown. In panel (a) the initial reconstruction is shown. The result of applying the proposed method is shown in panel (b). In panel (c), the curves for the astigmatism in \({x}\)\(({Z}_{3})\), defocus \(({Z}_{4})\) and astigmatism in \(y\) \(({Z}_{5})\) are shown. The normalized wavefront codified in the pupil plane by the M-AL is shown in the left-bottom corner panel (c) for a visual reference of the corrected aberration.

In (a) the calibration test original HSPM image is shown. The sample is slightly defocused to add an additional aberration. In (b) the initial reconstruction after applying the method is shown. In (c) the merit function evolution for Zernike’s coefficients \({Zn}\) from 3 to 5 is shown. Additionally, in the left-bottom corner of (c) the normalized phase map codified in the lens is shown.

In previous SPM systems with conventional binning approaches the reached resolution limit is around of 1.95 µm27,29, despite of implementing bigger magnification objectives and lower wavelengths. Those literature reported values are strongly surpassed using the proposed method just for the first order aberrations, which configures the DMD biggest aberration contributors. The presented low-aberration HSPM allows to reach 550 lp/mm, corresponding to a distance between lines of 0.9 µm. Considering an Abbe resolution limit of 0.81 µm, given by the system \({NA}=0.4\), we can measure a distance just 0.09 µm away from the diffractive system resolution. The proposed methodology not only allows the correction of aberrations with a minimal system intervention by introducing a plug-and-play transmissive M-AL. Also allows the aberration correction without performing any wavefront measurement, just by applying a merit function over a HS subsampling area, relieving the need of projecting all the Hadamard basis and retrieving any intermediate image. A comprehensive comparation between the reached performance and different reported SPM solutions is provided in supplementary file.

Sample-induced aberrations

Finally, the proposed method was tested by imaging a biological sample. We use a thick biological sample, composed of cotton tissue. This kind of sample introduces aberrations itself. The pattern projection through the cotton jeopardizes the periodic structures due to sample induced aberrations. From Eq. (2) one can conclude that the aberration induced by a sample \({{\rm{s}}}({{\rm{y}}})\) can be compensated by imaging with a pattern convolved with the said aberrations. \(s\left(y\right)\left({H}_{k}\otimes \widetilde{p}\right)\left(y\right){dy}=\,{H}_{k}\left(-y\right)\left(s\otimes \widetilde{p}\right)\left(y\right)\). By applying the proposed method not only the DMD induced aberrations but also the sample induced ones are corrected.

In Fig. 7a the initial HSPM of the cotton tissue is shown. All the cotton fiber borders are blurred and there are no appreciable high frequency structures. In panel (b) the retrieved image after applying the method is shown. Only the first order aberration where corrected demonstrating an achievable image enhancement without correct the higher order aberrations as well as with high resolution target. The final values are shown in the gray label placed in the panel (b) bottom. By applying the proposed method a significant improvement is reached as is highlighted in the zoomed insets. The mlp-inferno look up table was applied to have a better visualization of the reached improvement.

In the corresponding yellow and black encircled insets, high resolution details are only resolved by performing the proposed method. An intensity plot profile is added to better detail how the achievable resolution is improved in the finest image structure details. The results validate the method performance not only for calibrated slides but also for biological samples.

As in the previous figures, in panel (b) a visualization of the normalized wavefront encoded by the M-AL at the pupil plane is provided for graphic reference. The recovered wavefront is predominantly determined by sample-induced aberrations, which are compensated by the proposed procedure. Showing the feasibility of the method to correct both optical aberrations created by the specimens being imaged or by the imaging system itself. This profiles a novelty solution to operate near to resolution limit in HSPM just by adding a phase correction to the DMD projected patterns. Allowing the correcting not only the DMD but also the optical system and sample aberrations compromised in the M-AL range of operation.

In conclusion, in this work, the detrimental effects of digital micromirror device (DMD)-induced aberrations on the performance of Hadamard-based single-pixel microscopy (HSPM) have been addressed both theoretically and experimentally for the first time. These aberrations have been quantified and compared to recent reports in the literature, allowing a deeper understanding of their impact to be established. To correct these aberrations, a plug-and-play multiactuator deformable lens (M-AL) has been implemented without requiring significant modifications to the traditional HSPM setup. The proposed M-AL solution has been seamlessly integrated, avoiding complex alignment procedures or additional optomechanical components. Effective optical correction has been enabled by conjugating the DMD-induced aberrations with the deformable lens at the microscope pupil plane. Through this approach, the system has been allowed to operate near the diffraction limit, free from aberration effects, constituting the earliest reported structured illumination HSPM operating in an aberration-free manner.

Furthermore, an automated, wavefront sensor-less method has been proposed to correct both DMD-induced and sample-induced aberrations. Sample aberrations are corrected by systematically introducing additional aberrations using the AO thus improving image quality and providing information about the sample aberrations. This method has been shown to correct not only DMD-induced aberrations but also those caused by the sample itself, as demonstrated using a thick biological sample of cotton tissue. By fully addressing the limitations imposed by DMD aberrations, a higher base resolution for HSPM has been achieved, rendering the binning techniques commonly employed in the field unnecessary.

Overall, this study has not only provided the first optical correction of DMD-induced aberrations in HSPM but also established a robust framework for the integration of adaptive optics (AO) into single-pixel microscopy systems with minimal modifications. By doing so, imaging performance has been enhanced, the versatility of HSPM has been broadened, and a pathway has been paved for future innovations in high-resolution, multimodal microscopy.

Methods

Optical microscope set-up

All the presented results were produced by following the guide reported guides for design, assembly, alignment and application of single-pixel microscope reported in Ref. 32. All the required materials and an expanded protocol for the implemented HSPM construction can be found in repository contained in Ref. 39. Regarding the operational conditions for the implemented setup shown in Fig. 2. the light from a 650 nm diode was aligned into the system by implementing the illumination alignment module. Then after interacting Vialux V-650L DMD, with a pixel pitch of \(10.8\,\mu m\), passes through the HSPM setup until reaching the sample plane, where a demagnified image of the DMD is projected. The HSPM projection module configures a telecentric imaging system with a Mitutoyo 20X microscope objective (MO), \({NA}=0.4\), and a 200 mm Nikon tube lens (TL). The DMD is conjugated with both the object plane and the field diagram. A relay 4 F system, with lenses L1 and L2 of focal length 75 mm, offers direct access to the microscope aperture plane, which is directly conjugated with the pupil imaging system. In this plane the M-AL is placed to introduce an user define wavefront achieving the correction of both the optical system and the specimen induced aberrations. The projected pattern over the sample light is collected by the reflection module imaging system, which is configured by a second tube lens (TL2) and a microscope objective that condense the light over a bucket detector.

Data availability

The data regarding the corresponding HSPM optical design, alignment and application instructions can be found in publicly available format the repository https://osf.io/zgyv3/, cited in Ref. 39.

References

Radwell, N. et al. Single-pixel infrared and visible microscope. Optica 1, 285 (2014).

Ghezzi, A. et al. Computational based time-resolved multispectral fluorescence microscopy. APL Photonics 8, (2023).

Santos-Amador, A. & et. Phase and amplitude reconstruction in single-pixel transmission microscopy: a comparison of Hadamard, cosine, and noiselet bases. Appl. Opt. 60, 6935 (2021).

Pian, Q., Yao, R., Sinsuebphon, N. & Intes, X. Compressive hyperspectral time-resolved wide-field fluorescence lifetime imaging. Nat. Photonics 11, 411–414 (2017).

Yoneda, N., Saita, Y. & Nomura, T. Common-path off-axis single-pixel holographic imaging. Opt. Express 30, 18134 (2022).

Studer, V. et al. Compressive fluorescence microscopy for biological and hyperspectral imaging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 109, E1679–E1687 (2012).

Calisesi, G. et al. Compressed sensing in fluorescence microscopy. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 168, 66–80 (2022).

Wu, D. et al. Imaging biological tissue with high-throughput single-pixel compressive holography. Nat. Commun. 12, (2021).

Edgar, M. P., Gibson, G. M. & Padgett, M. J. Principles and prospects for single-pixel imaging. Nat. Photonics 13, 13–20 (2019).

Zapata Valencia, S., Tobón, H., Matoba, O., Lancis, J. & Tajahuerce, E. Quantitative phase imaging in Hadamard-based active single-pixel microscopy by motionless transport of intensity equation. Opt. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.566044 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Microscopic single-pixel polarimetry for biological tissue. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, (2023).

Ndagijimana, A., Conde, M. H. & Urzainqui, I. E. Performance Evaluation of Spatial Modulation Patterns in Compressive Sensing Terahertz Imaging. in 2022 IEEE Sensors 1–4 https://doi.org/10.1109/SENSORS52175.2022.9967090 (2022).

Stantchev, R. I., Yu, X., Blu, T. & Pickwell-MacPherson, E. Real-time terahertz imaging with a single-pixel detector. Nat. Commun. 11, 2535 (2020).

Sefi, O., Klein, Y., Strizhevsky, E., Dolbnya, I. P. & Shwartz, S. X-ray imaging of fast dynamics with single-pixel detector. Opt. Express 28, 24568 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Wang, X., Zheng, G. & Zhong, J. Hadamard single-pixel imaging versus Fourier single-pixel imaging. Opt. Express 25, 19619 (2017).

Pratt, W. K., Kane, J. & Andrews, H. C. Hadamard transform image coding. Proc. IEEE 57, 58–68 (1969).

Deng, Z., Qi, S., Zhang, Z. & Zhong, J. Autofocus Fourier single-pixel microscopy. Opt. Lett. 48, 6076 (2023).

Tobón-Maya, H. et al. Autofocusing method for active Hadamard single-pixel microscopy using gradient descent algorithms. Opt. Lasers Eng. 185, 108699 (2025).

Lee, B.-R., Marichal-Hernández, J. G., Rodríguez-Ramos, J. M., Venkel, T. & Son, J.-Y. Compensation of wavefront aberration introduced by DMDs’ operation principle. Opt. Mater. (Amst.). 140, 113863 (2023).

Popoff, S. M., Gutiérrez-Cuevas, R., Bromberg, Y. & Matthés, M. W. A practical guide to digital micro-mirror devices (DMDs) for wavefront shaping. J. Phys. Photonics 6, 43001 (2024).

Scholes, S., Kara, R., Pinnell, J., Rodríguez-Fajardo, V. & Forbes, A. Structured light with digital micromirror devices: a guide to best practice. Opt. Eng. 59, 1 (2019).

Sébastien M. Popoff. Setting up a DMD/SLM: Aberration effects. https://www.wavefrontshaping.net/post/id/23.

Bueno, J. M., Skorsetz, M., Bonora, S. & Artal, P. Wavefront correction in two-photon microscopy with a multi-actuator adaptive lens. Opt. Express 26, 14278 (2018).

Kim, H. et al. Modal focal adaptive optics for Bessel-focus two-photon fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Express 33, 680 (2025).

Furieri, T., Bonora, S. & Bortoli Saygashev, A. V. Sensorless multi-conjugated adaptive optics with free form deformable lenses. in Adaptive Optics and Wavefront Control for Biological Systems X (eds. Tian, L., Bifano, T. G. & Ji, N.) 18 (SPIE, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3001534.

Zhang, Z., Wang, X., Zheng, G. & Zhong, J. Fast Fourier single-pixel imaging via binary illumination. Sci. Rep. 7, 12029 (2017).

Rodríguez, A. D., Clemente, P., Tajahuerce, E. & Lancis, J. Dual-mode optical microscope based on single-pixel imaging. Opt. Lasers Eng. 82, 87–94 (2016).

Liu, Y., Suo, J., Zhang, Y. & Dai, Q. Single-pixel phase and fluorescence microscope. Opt. Express 26, 32451 (2018).

Zhao, Y.-N. et al. Single-pixel dual-mode microscopy for simultaneous acquisition of magnitude and wrapped phase images. Opt. Laser Technol. 182, 112017 (2025).

Pozzi, P. et al. Plug-and-play adaptive optics for commercial laser scanning fluorescence microscopes based on an adaptive lens. Opt. Lett. 45, 3585 (2020).

Furieri, T. et al. Aberration measurement and correction on a large field of view in fluorescence microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express 13, 262–273 (2022).

Zapata-Valencia, S. I. et al. Design, assembly, alignment and application of a versatile, open-source, single-pixel microscope. Sci. Rep. 15, 17802 (2025).

Lee, B. Introduction to ±12 Degree Orthogonal Digital Micromirror Devices (DMDs). (2018).

Ávila, F. J. & Bueno, J. M. Spherical Aberration and Scattering Compensation in Microscopy Images through a Blind Deconvolution Method. J. Imaging 10, 43 (2024).

Mahajan, V. N. & Díaz, J. A. Comparison of geometrical and diffraction imaging in the space and frequency domains. Appl. Opt. 55, 3241 (2016).

Hopkins, H. H. The frequency response of a defocused optical system. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 231, 91–103 (1955).

Guo, L., Cao, X. & Liu, L. A Novel Autofocus Measure Based on Weighted Walsh-Hadamard Transform. IEEE Access 7, 22107–22117 (2019).

Tehrani, K. F., Xu, J., Zhang, Y., Shen, P. & Kner, P. Adaptive optics stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (AO-STORM) using a genetic algorithm. Opt. Express 23, 13677 (2015).

Zapata-Valencia, S. I. et al. Single-Pixel Microscope Repository. at https://osf.io/zgyv3/?view_only=75b2899e3ac54e51ae7094f4647dee3b (2025).

Acknowledgements

Funded by the European Union (GA 101072354). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. Acknowledgment is also made to Grant PID2022−142907OB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and “ERDF/EU” and grant CIPROM/2023/44 funded by Generalitat Valenciana.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.T., L.W., S.Z., S.B., E.T. and J.L conceptualized the assembly methodology. They designed and constructed the optical setup. S.Z., H.T., and L.W. conceived and conducted the experiments. L.W prepare all the M-AL controlling routines. S.B., J.L., and E.T. conceptualized the research goals and supervised, advised, and reviewed the research progress. They also administrated the project and acquired funding. H.T. prepared the main manuscript and figures. All the authors discussed the methodology and results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S. Bonora acknowledges a financial interest in Dynamic Optics s.r.l. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mengchao Ma and Yuan-Jin Yu for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tobón-Maya, H., Willstatter, L., Zapata-Valencia, S.I. et al. Hadamard based single-pixel microscopy using sensor-less adaptive optics supported by multi-actuator adaptive lens. Nat Commun 16, 10933 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65940-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65940-4