Abstract

Avalanche photodiodes (APDs) demand multiplication materials with low ionization coefficient ratio (k) for high-speed and high-sensitivity photodetection. Germanium/Silicon (Ge/Si) APDs have been preferred for a decade, leveraging the exceptional multiplication property of Si and inherent complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) compatibility. However, the bandwidth remains tens of gigahertz, fundamentally limited by unexpected dual-carrier multiplication in high-k Ge. Here, we transcend this material limitation by introducing a uni-multiplication-carrier concept. Through a separated absorption-charge-cliff-multiplication structure, we elaborately tailor the electric field to gradient distribution within a thin Ge region, establishing electron-dominated multiplication with a significantly reduced k. Experimentally, the device achieves a record-high bandwidth of 105 GHz at a gain of 7. This enables 8×260 Gb/s signal reception, previously only achieved by gainless photodetectors, while providing 9 dB sensitivity improvement. This work paves the way for amplifier-free optical communications, ultra-precise optical sensing, and large-scale optical computing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-speed and high-sensitivity photodetectors constitute cornerstones of numerous optical systems and applications1,2,3,4. Traditional photodetectors operating without gain have demonstrated bandwidths of several hundred gigahertz, while exhibiting limited sensitivity5,6,7. In low-power scenarios ranging from ubiquitous fiber-to-the-home networks8, consumer-electronic optical sensors9 to emerging inter-chip optical interconnects for intelligent computing10, avalanche photodiodes (APDs) have emerged as indispensable solutions to offer orders-of-magnitude higher sensitivity, due to internal carrier multiplication mechanism11,12. However, the bandwidth is typically inferior to gainless photodetectors, due to the need of time for avalanche build up process13. As elucidated by pioneering works14,15, avalanche multiplication is a stochastic process involving both electrons and holes. The hole/electron ionization ratio (k) of multiplication material largely governs high-speed characteristics. A low k is desirable for a more deterministic process closer to single-type carrier multiplication, diminishing average avalanche build-up time for a target gain. This consequently enhances bandwidth and correspondingly, gain-bandwidth product (GBP). Commercial APDs use Indium-Phosphide (InP, k = 0.4)16 or Indium-Aluminum-Arsenic (InAlAs, k = 0.2)17,18 for multiplication, achieving bandwidths up to 42 GHz and GBPs limited to 270 GHz. Although several Antimony (Sb)-doped III-V materials with very low k have been investigated19,20, the complex fabrication and technological immaturity have precluded substantial experimental validation. Moreover, deep concerns regarding cost and integration density hinder the widespread adoption of these III-V devices, due to incompatibility with complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology.

These technological impasses have driven intense interest in Germanium/Silicon (Ge/Si) APDs based on Si photonic platform, leveraging low k of Si (0.02-0.05) and inherent CMOS compatibility21,22. They mainly operate in optical communication bands near 1.3/1.5 μm through Ge absorber with large optical absorption coefficient. However, unintended carrier multiplication readily occurs in Ge when a high electric field is applied to trigger Si multiplication, due to the much lower multiplication threshold than Si23,24. Unfortunately, Ge (k ~ 0.9) is very undesirable multiplication material, resulting in near-equal electron and hole multiplication. This ultimately limits the high-speed performance of Ge/Si APDs. To address this issue, separated absorption-charge-multiplication (SACM) structures are typically utilized25,26,27,28,29,30,31. The charge layer is carefully optimized to maintain a low electric field within the Ge region for preventing Ge multiplication. Additionally, the sizes of Ge/Si junctions are scaled to several hundred nanometers to shorten carrier transit paths and to narrow the impact ionization probability distribution function. The latter alleviates the uncertainty of carrier multiplication, known as the dead-space effect32,33,34. Through these efforts, GBPs exceeding 3000 GHz have been reported35,36. However, in SACM structures, the weakened electric field in Ge reduces carrier drift velocity, thus limiting bandwidth in the range of 10−67 GHz. Nowadays, the insatiable demand for high-speed optical transmission toward multi-terabit capacities creates an urgent need for APDs that can transcend conventional performance boundaries.

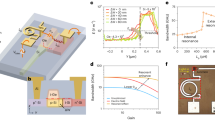

Here, we introduce a strategy, namely electric field gradient engineering, to transform Ge into an ordered uni-multiplication-carrier (UMC) medium. By incorporating a cliff layer to construct a separated absorption-charge-cliff-multiplication (SAC²M) structure, we elaborately tailor a gradient-distribution electric field within a thin Ge region to enhance electron multiplication and suppress hole multiplication along their opposite motions, thereby establishing electron-dominated asymmetric multiplication. Meanwhile, we locate the high electric field in a very narrow region to exploit the dead-space effect and optimize resistance-capacitance (RC) delay to enable a leap in bandwidth. Experimentally, the UMC-APD shows a record-high bandwidth of 105 GHz at a gain of 7, and bandwidth of 100 GHz at a high gain of 13.4, representing the breakthrough in exceeding 100 GHz bandwidth among all reported APDs17,18,19,21,27,28,29,30,31,35,36,37,38, reaching the level of state-of-the-art Ge/Si PIN photodiodes operating without gain39,40 (Fig. 1a). Thanks to the low noise, the device achieves a GBP as high as 4800 GHz, under optical power of −31 dBm (Fig. 1b). Data reception of 260 Gb/s four-level pulse amplitude modulation (PAM4) signal demonstrates 9 dB sensitivity improvement over bandwidth-matched PIN photodiode. This work is expected to establish a paradigm for photodetectors in optical communication, sensing, and computing.

Results

Device concept and design

The bandwidth of an APD is determined by avalanche built-up time, carrier transit time and resistance-capacitance (RC) delay41. Primarily, the UMC-APD concept substantially reduces the k-dependent avalanche build-up time. The schematic of the UMC-APD is depicted in Fig. 2a, showing the cross-section of the Ge/Si junction region and the theoretical electric field distribution. In traditional SACM structure, intrinsic Ge (i-Ge) is used for optical absorption, while intrinsic Si (i-Si) serves as the multiplication region. The intermediate charge layer regulates the electric field in the Ge and Si regions through doping concentration. Given that the gradient of the horizontal component of electric field is proportional to the doping concentration at that location, the electric field in the Ge region is uniform and should be maintained below the threshold electric field of Ge (Eth) to prevent multiplication. However, this condition is easily disrupted as the applied voltage increases or the charge layer doping concentration is lower than the design value, leading to nearly equal multiplication of electrons and holes. In contrast, in the proposed SAC2M structure, a lightly doped charge layer beneath i-Ge is utilized to generate a gradient electric field that varies linearly with spatial position. Meanwhile, a thin and higher doped cliff layer positioned under the Ge region forms a localized electric field cliff. Although the charge layer and cliff layer are located beneath the Ge region, we leverage the natural expansion of electric field into Ge absorber to precisely engineer a graded electric field profile in the Ge region. The proposed structure allows for a high electric field to achieve a large bandwidth, while the k is reduced even when multiplication occurs in Ge, primarily due to the following reasons. (1) The gradient electric field forces electrons and holes to experience opposing multiplication dynamics: electrons are rapidly accelerated into high-field region for impact ionization, while holes are steered toward low-field region where the ionization is suppressed, resulting in electron-dominated asymmetric multiplication. (2) Due to the cliff layer, the high electric field is localized in a very narrow region, benefiting from the dead-space effect. This effect narrows the probability density distribution of impact ionization, drastically reducing the variation in ionization path lengths. Therefore, it minimizes the avalanche build-up time jitter and enables a faster and more deterministic multiplication process.

a The cross-section of junction region and the theoretical electric field distribution in the uni-multiplication-carrier avalanche photodiode and conventional avalanche photodiode. A, absorption. C, charge. M, multiplication. Pcon, P connect. Ncon, N connect. b The three-dimensional structure of the uni-multiplication-carrier avalanche photodiode. c The simulated electric field under different charge layer doping concentrations at −8 V. d The simulated bandwidth under various geometrical dimensions with optimal inductances. e The simulated bandwidth as a function of inductance.

Fig. 2b presents the three-dimensional structure of the proposed UMC-APD with a SAC2M junction. The device is designed and fabricated on a silicon-on-insulator (SOI) platform. The detailed fabrication process can refer to Methods. A waveguide-coupled structure is adopted wherein input light propagates via a 420 × 220 nm2 single-mode Si waveguide and evanescently couples into the upper Ge region of 150 nm thickness. Typically, Ge length over 10 μm is required to ensure sufficient optical absorption >90% at 1550 nm42. Here, a reduced 5.8 μm Ge length is used to nearly halve the junction capacitance to enhance bandwidth. To compensate the resulting reduced responsivity, a Si-based distributed Bragg reflector (DBR) facilitates secondary optical absorption43,44. Additionally, suppressed dark current combined with the compensated responsivity yields slightly improved sensitivity. The DBR design and relevant optical simulations are detailed in Supplementary Note 1. The electric field gradient in the Ge region is engineered by the doping concentration of the charge layer. Fig. 2c shows the simulated electric field along the red dashed line (in Fig. 2b) under different charge layer doping concentrations, with a fixed cliff layer doping concentration of 1 × 1018 cm-3. The widths of the charge layer and cliff layer are 240 and 60 nm, respectively. The detailed optimization process can refer to Methods. The charge layer doping concentration is optimized to 2 × 1017 cm-3 for the favorable gradient-distributed electric field profile. When the doping concentration is lower, the electric field in the Ge region becomes nearly uniform and exceeds the threshold, resulting in equal multiplication of electrons and holes. When a higher doping concentration is used, the electric field becomes very low and is unable to support carrier saturation velocity. The simulated 2D electric field distributions for both the proposed SAC²M and conventional SACM APDs are provided in the Supplementary Note 2. Given the reduced k, an on-electrode inductance is implemented to enhance bandwidth by optimizing RC delay. Fig. 2d shows the simulated bandwidth versus i-Si and i-Ge region widths, with each point matching its optimal inductance, at the gain of 10. The k of the device is assumed to approach that of the Si (~0.05). Supplementary Note 3 presents the comprehensive bandwidth model of the Ge/Si APD incorporating an inductance. A configuration with 100 nm-wide i-Si and 130 nm-wide i-Ge achieves a theoretical maximum bandwidth of 142 GHz. However, such a narrow Ge region will result in a sharp degradation in responsivity. Consequently, a 300 nm-wide i-Ge region is selected, still possible to achieve a bandwidth of over 100 GHz. Fig. 2e presents simulated bandwidth under different inductances at this junction size. The bandwidth initially increases and then decreases with the introduced inductance, and the optimal inductance is 360 pH for a simulated bandwidth of ~110 GHz. Detailed structural parameters and design of the inductance are provided in Supplementary Note 3.

Device Performance

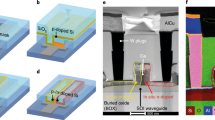

Firstly, the static performance of the fabricated UMC-APD is measured (see Methods). The light is coupled into the device using a Transverse Electric (TE)-polarized grating coupler with the coupling loss of 3.5 dB at 1550 nm. Although the grating coupler itself is polarization-sensitive, the UMC-APD is intrinsically polarization-insensitive, due to the isotropic optical absorption of Ge. Fig. 3a shows the measured dark current and photocurrent under different optical power at 1550 nm. Under low voltages, the photocurrent increases proportionally with optical power, and the proportionality changes under high voltages due to the varying gain. The unity gain is obtained at -1.5 V, determined by the photocurrent of a reference photodiode on the same chip, which lacks the charge layer and multiplication effect21,22. The optical responsivity near -1.5 V is shown in Supplementary Note 4. It is clear that -1.5 V is the boundary that differentiates the no-gain from the notable-gain areas, demonstrating that the unity gain occurs at -1.5 V. Figure 3b shows the net photocurrent (the difference between photocurrent and dark current) as a function of optical power at -1.5 V with and without DBR, indicating that the introduction of the DBR enhances the primary responsivity from 0.3 to 0.51 A/W. The responsivity refers to internal responsivity, excluding the coupling loss. Considering the coupling loss, the external responsivity is 0.23 A/W. Fortunately, optical couplers with loss as low as 1 dB have been demonstrated45,46, which could potentially increase the external responsivity to ~0.4 A/W, making the device highly competitive for practical applications. After obtaining the primary responsivity, the gains under other voltages are shown in Fig. 3c. The breakdown voltage is determined to be as low as -7.2 V, according to 1/Gain-voltage curves under different optical power shown in Supplementary Note 4. These gains increase with voltage until reaching a maximum value after -7.2 V across different optical power. As optical power increases, the gain decreases due to the space charge effect34,47. The maximum gains reach 20.6, 30.2, and 40.9 under optical power of -22, -25, and -28 dBm, respectively. The measured dark current is 37 nA at -1.5 V, and it reaches 19 μA at -6.5 V (90% of the breakdown voltage).

a The measured current-voltage characteristics in dark state and under optical power of −28 to −22 dBm. b The measured net photocurrent as a function of optical power at unity gain with/without the distributed Bragg reflector. c The measured gains under different voltages and optical power. d The measured S21 responses from −5 to −7 V under −22 dBm. e The measured bandwidth and corresponding gain-bandwidth product with different gains under −22 dBm. f The measured bandwidth with different inductance.

The bandwidth of the UMC-APD is analyzed by measuring the S21 frequency response from 10 MHz to 110 GHz. Fig. 3d shows the normalized S21 responses from -5 to -7 V under -22 dBm. At the same voltage, the normalized S21 responses and 3-dB bandwidths are almost unchanged under different optical power. The bandwidth first increases and then decreases with the voltage, and the maximum bandwidth is 105 GHz at -6 V. The frequency responses show an obvious resonance phenomenon, with a peak appearing at the frequency of ~90 GHz. The S21 response is not flat even at low frequencies, maybe attributed to the diffusion component of the photocurrent. While the RC time constant does not contribute to roll-off in this low-frequency regime, and carriers drift at saturated velocities in the high-field regions, a portion of the photocurrent is generated via a slower diffusion process48. The bandwidths and corresponding GBPs with different gains under -22 dBm are shown in Fig. 3e. When the gain is <7, the bandwidth gradually increases with the gain due to the depletion of Ge region and reduced carrier transit time. Then, the bandwidth gradually decreases to 100 GHz at the gain of 13.4 (at -6.8 V), and to 84 GHz at the gain of 21.6 (at the breakdown voltage of -7.2 V), due to the gain-bandwidth trade-off, corresponding to a GBP of 1814 GHz. Due to the weaker SCE, the GBP increases with reduced optical power. The measured GBPs under different optical power and related analysis are provided in Supplementary Note 5. The GBP increases to as high as 4800 GHz under optical power of -31 dBm. The measured bandwidths of the UMC-APD with inductance from 0 to 600 pH are shown in Fig. 3f. The results are consistent with the simulation. With the introduced inductance of 360 pH, the bandwidth is enhanced from 50 to 105 GHz with about 2-fold.

High-speed optical interconnect demonstration

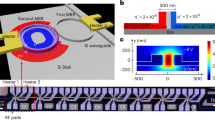

We conduct signal reception experiments to validate the performance of the UMC-APD in ultra-high-speed optical interconnects (see Methods), with the setup shown in Supplementary Note 6. Fig. 4a shows the microscope image of fabricated 8-channel UMC-APD array. The devices operate at -6.8 V to achieve a 100 GHz bandwidth and high gain. Firstly, the single channel is tested. As shown in Fig. 4b, we obtain clear eye diagrams and bit error rate (BER) for 130/150 Gb/s on-off keying (OOK) signals by setting the optical power to -11 dBm. Moreover, high-order pulse amplitude modulation is used to increase capacity. The device successfully receives 224/260 Gb/s PAM4 and 270/285 Gb/s eight-level pulse amplitude modulation (PAM8) signals with open eye diagrams under -7.2 dBm.

a The microscope image of fabricated 8-channel uni-multiplication-carrier avalanche photodiode array. The ground-signal-ground electrode is used. b The measured eye diagrams of high-speed on-off keying, four-level pulse amplitude modulation, and eight-level pulse amplitude modulation signals. c The measured bit error rate results for the on-off keying and four-level pulse amplitude modulation signals under different received optical power. d The measured bit error rate results for the on-off keying and four-level pulse amplitude modulation signals with different bitrates.

The sensitivities of the UMC-APD for high-speed OOK and PAM4 signals are quantified, as shown in Fig. 4c. The soft-decision forward error correction threshold (SD-FEC, BER = 2 × 10-2) is used to estimate the performance. This suggests that error-free operation can be facilitated through digital signal processing algorithms. At the SD-FEC threshold, the sensitivities are -16.3 and -14.2 dBm for 130 and 150 Gb/s OOK signals, respectively. For 224 and 260 Gb/s PAM4 signals, the UMC-APD exhibits sensitivities of -10.9 and -10.1 dBm, respectively. This suggests a ~ 9 dB sensitivity improvement compared to the reference PIN photodiode with a bandwidth of 103 GHz operating at 260 Gb/s PAM4. The detailed information of the PIN photodiode is previously reported in ref. 39. Fig. 4d shows the measured BER under different bitrates of these modulation formats. The device is capable to receive up to 200 Gb/s OOK and 284 Gb/s PAM4 signals with BER lower than SD-FEC threshold. Finally, the 8-channel UMC-APD array is utilized to receive 8 × 260 Gb/s (2.08 Tb/s) wavelength-multiplexing PAM4 signals, with open eye diagrams and BERs presented in Supplementary Note 6. An off-chip commercial wavelength demultiplexer is implemented. The eight wavelengths range from 1543.6 to 1554.8 nm with a channel spacing of 1.6 nm. The demultiplexed optical signals are then coupled into the photonic chip using a grating coupler array designed for TE polarization. These results position the UMC-APD as a highly competitive solution to meet the demands of large-capacity optical interconnects.

Discussion

Table 1 benchmarks the performance of state-of-the-art high-speed III-V and Si-based APDs in literature. This work demonstrates a record-high bandwidth of 105 GHz and an ultra-high GBP. Consequently, the highest data reception bitrate has been achieved. Particularly, this marks a breakthrough in exceeding the 100 GHz bandwidth level in APDs, reaching the level of state-of-the-art PIN PDs without gain. This indicates that APDs are able to have more opportunities in ultra-high-speed occasions. Due to the inherent avalanche buildup time during impact ionization, higher gain requires more ionization cycles and longer time, which lengthens the process and reduces bandwidth. This is influenced by the k, where a lower k can reduce avalanche buildup time. Therefore, the good performance is attributed to the gradient-distributed electric field induced by SAC2M structure—the key distinction from previous Ge/Si APDs. This is an approach to overcome the inherent limitations of Ge multiplication. Although it is demonstrated using Ge/Si APDs, it can be naturally extended to other material systems. By tailoring the field profile to promote single-carrier multiplication, the effective k can be minimized, irrespective of the base material. In terms of device geometry, the concept is also highly adaptable. When the device size changes, k can still be reduced as the doping concentration is adjusted accordingly to optimize the gradient of electric field. As shown in Supplementary Note 7, the fitting results of excess noise (equivalent to the BER measured under the same conditions) and gain indicate that the device exhibits k of as low as 0.06. Compared to the values of 0.1–0.3 reported in previous Ge/Si APDs and 0.7 in pure-Ge APDs, it has been significantly reduced. In addition, the low breakdown voltage of -7.2 V is suitable for the integration with electronic circuit used for emerging co-package optics and chiplet optical interconnects49. The primary trade-off in the device is the fundamental responsivity-bandwidth trade-off. To achieve higher bandwidth, we reduce the volume of the Ge absorption region, which in turn lowers the total optical absorption and thus the responsivity.

The temperature stability of APD is important. As temperature increases, enhanced phonon scattering reduces carrier ionization coefficients, thereby decreasing the multiplication gain for a fixed bias voltage. To maintain constant gain, a higher bias should be applied, leading to an increased breakdown voltage. This behavior is captured by the temperature coefficient of breakdown voltage, ΔVBD/ΔT50. The simulations show a high temperature stability with a ΔVBD/ΔT of 10.1 mV/°C, which is comparable to typical Ge/Si APDs51 and better than that of conventional III-V APDs52,53. This indicates that the gain can be effectively stabilized against temperature variations with only minor adjustments to the operating voltage. As temperature increases, gain decreases and dark current increases, resulting in higher excess noise. The simulations confirm that the excess noise increases modestly with temperature while remaining at acceptably low levels due to the low k. These results are presented in Supplementary Note 8.

In conclusion, we present the demonstration of APD featuring a bandwidth over 100 GHz. The device supports data reception of over 2.08 Tb/s assisted by wavelength division multiplexing, enabling 9 dB sensitivity improvement compared to gainless photodetectors with the same bandwidth. The waveguide-coupled structure, low operating voltage and CMOS-compatible fabrication render the device highly promising to promote the future development of amplifier-free optical communications, ultra-precise sensing, and large-scale optical computing.

Methods

Device optimization

The widths of the multiplication and absorption regions are first determined through bandwidth simulation. The cliff layer width is then designed to be larger than the dead-space distance in Ge, ensuring that carriers gain sufficient energy to initiate impact ionization. This physical requirement sets the lower bound for the cliff layer width. The charge layer width is consequently determined as the remainder of the total Ge region. With the geometries being fixed, the doping concentrations of both layers are co-optimized using semiconductor device simulations. The key criterion is to minimize the k within the Ge region to achieve electron-dominated multiplication, by evaluating the ionization integrals related to electric field profile for a range of doping combinations.

Device fabrication

The UMC-APD is fabricated on a silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafer with a 220 nm top Si layer, a buried oxide layer, and a Si substrate. The initial step involves patterning the top Si layer into rib waveguides and slabs using 193 nm deep ultraviolet (DUV) photolithography followed by dry etching techniques. The Si slab is then doped with boron of concentrations of 2 × 1017 cm-3 and 1 × 1018 cm-3 designated for the charge and cliff charge layers, respectively. For establishing ohmic contacts on Si, distinct masks are employed for the implantation of heavily doped boron and phosphorus with a concentration of ~1020 cm-3. The dopants are subsequently activated through rapid thermal annealing at 1030 °C for a duration of 5 seconds. High-quality Ge epitaxy is achieved via a two-step process involving low and high-temperature growth. Initially, the substrate is maintained at 350 °C to grow a thin SiGe buffer layer on the Si slab. In the subsequent step, a 150 nm thick high-quality pure Ge layer is selectively grown on the buffer layer using ultra-high vacuum chemical vapor deposition (UHVCVD) at 550 °C, followed by high-temperature annealing. The device is completed with the fabrication of the first and second Al metal layers to form the on-chip inductance and bonding pads.

Device measurements

The I-V characteristics are measured utilizing a source meter (Keithley 2601B), a probe station, and a tunable laser. The photocurrent is measured at 1550 nm, after accounting for the coupling loss of the optical coupler (3.5 dB). Dark current measurements are conducted in the absence of incident light. The operating voltage is swept from 0 to -7.5 V. The voltage at unity gain is ascertained from the photocurrent of a reference photodiode integrated on the same chip, which lacks the charge layer and multiplication effect. The multiplication gain is then calculated as the ratio of the net photocurrent to that measured at the unity gain point. The breakdown voltage is determined based on 1/Gain-voltage curves under varying optical power conditions. The intersection of the 1/Gain curves at a common point on the voltage axis signifies the onset of infinite gain, indicative of avalanche multiplication.

Small-signal RF measurements are performed using a 110 GHz vector network analyzer (VNA, Keysight N5227B) in a frequency range from 10 MHz to 110 GHz. The RF signal emitted by the VNA is employed to drive a lithium niobate electro-optic modulator (NOEIC MZ135-LN60), enabling the frequency response of the APD to be measured. An Impedance Standard Substrate is utilized to calibrate the bias-tee, cables, and GSG-microprobe, with subsequent correction applied to the S21 response of the electro-optic modulator for the measurement data. Reverse bias voltages are supplied to the UMC-APD via the source meter (Keithley 2601B) and a bias-tee.

In high-speed signal experiments, digital OOK, PAM4, and PAM8 signals with a pattern length of 215-1 are generated by an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG, Keysight M9502A) and amplified by a high-speed electrical driver. The modulator (NOEIC MZ135-LN60) is used to modulate continuous-wave light. The optical signal is fed into the chip, and the output RF signal is captured by a real-time digital storage oscilloscope with a 256 GSa/s sampling rate (Keysight UXR0134A). Offline post-compensation is conducted to deduct the distortion of high-speed electrical signals through the cables and the transmitter. This post-compensation involves the use of adaptive feedforward equalization (FFE) and adaptive maximum likelihood sequence estimation (MLSE) to achieve channel estimation and mitigate inter-symbol interference.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the figures and from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Zhang, X. et al. A large-scale microelectromechanical-systems-based silicon photonics LiDAR. Nature 603, 253–258 (2022).

Pai, S. et al. Experimentally realized in situ backpropagation for deep learning in photonic neural networks. Science 380, 398–404 (2023).

Rizzo, A. et al. Massively scalable Kerr comb-driven silicon photonic link. Nat. Photonics 17, 781–790 (2023).

Lecocq, F. et al. Control and readout of a superconducting qubit using a photonic link. Nature 591, 575–579 (2021).

Koepfli, S. M. et al. Metamaterial graphene photodetector with bandwidth exceeding 500 gigahertz. Science 380, 1169–1174 (2023).

Lischke, S. et al. Ultra-fast germanium photodiode with 3-dB bandwidth of 265. GHz. Nat. Photonics 15, 925–931 (2021).

Ishibashi, T. et al. Ito, Uni-travelring-carrier photodiodes. J Appl. Phys. 127, 031101 (2020).

Zhang, D. et al. Progress of ITU-T higher speed passive optical network (50G-PON) standardization. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 12, D99–D108 (2020).

Shi, Q. et al. Progress in wearable electronics/photonics—Moving toward the era of artificial intelligence and internet of things. InfoMat 2, 1131–1162 (2020).

Wade, M. et al. TeraPHY: a chiplet technology for low-power, high-bandwidth in-package optical I/O. IEEE Micro 40, 63–71 (2020).

Huang, M. et al. Germanium on silicon avalanche photodiode. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. 24, 1–11 (2017).

Na, N. et al. Room temperature operation of germanium–silicon single-photon avalanche diode. Nature 627, 295–300 (2024).

Wang, B. & Mu, J. High-speed Si-Ge avalanche photodiodes. PhotoniX 3, 1–22 (2022).

Emmons, R. Avalanche-photodiode frequency response. J. Appl Phys. 38, 3705–3714 (1967).

David, J. et al. Material considerations for avalanche photodiodes. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. 14, 998–1009 (2008).

Zhao, Y. et al. Impact ionization in absorption, grading, charge, and multiplication layers of InP/InGaAs SAGCM APDs with a thick charge layer. IEEE T Electron Dev. 60, 3493–3499 (2013).

Nada, M. et al. Responsivity-bandwidth limit of avalanche photodiodes: Toward future ethernet systems. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. 24, 1–11 (2017).

Nada, M. et al. A 42-GHz bandwidth avalanche photodiodes based on III-V compounds for 106 Gbit/s PAM4 applications. J. Lightwave Technol. 37, 260–265 (2019).

Yi, X. et al. Extremely low excess noise and high sensitivity AlAs0.56Sb0.44 avalanche photodiodes. Nat. Photonics 13, 683–686 (2019).

Jones, A. et al. Low-noise high-temperature AlInAsSb/GaSb avalanche photodiodes for 2-μm applications. Nat. Photonics 14, 559–563 (2020).

Kang, Y. et al. Monolithic germanium/silicon avalanche photodiodes with 340 GHz gain-bandwidth product. Nat. Photonics 3, 59–63 (2009).

Huang, Z. et al. 25 Gbps low-voltage waveguide Si-Ge avalanche photodiode. Optica 3, 793–798 (2016).

Duan, N. et al. 310 GHz gain-bandwidth product Ge/Si avalanche photodetector for 1550 nm light detection. Opt. Express 20, 11031–11036 (2012).

Michel, J. et al. High-performance Ge-on-Si photodetectors. Nat. Photonics 4, 527–534 (2010).

Martinez, N. J. et al. High performance waveguide-coupled Ge-on-Si linear mode avalanche photodiodes. Opt. Express 24, 19072–19081 (2016).

Zeng, X. et al. Silicon-germanium avalanche photodiodes with direct control of electric field in charge multiplication region. Optica 6, 772–777 (2019).

Srinivasan, S. et al. 27 GHz silicon-contacted waveguide-coupled Ge/Si avalanche photodiode. J. Lightwave Technol. 38, 3044–3050 (2020).

Xiang, Y. et al. High-speed waveguide Ge/Si avalanche photodiode with a gain-bandwidth product of 615 GHz. Optica 9, 762–769 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. Avalanche photodiode with ultrahigh gain-bandwidth product of 1,033 GHz. Nat. Photonics 18, 610–616 (2024).

Zou, M. et al. Ultra-large bandwidth and ultra-high sensitivity germanium/silicon avalanche photodiode. Laser Photonics Rev. 19, 2401574 (2025).

Cao, H. et al. Waveguide Ge/Si avalanche photodetector with ultra-high gain-bandwidth product of 1440 GHz. In 2023 Asia Communications and Photonics Conference/2023 International Photonics and Optoelectronics Meetings (ACP/POEM). 1−3 (ACP/POEM, 2023).

Saleh, M. et al. Impact-ionization and noise characteristics of thin III-V avalanche photodiodes. IEEE T Electron Dev. 48, 2722–2731 (2001).

Assefa, S. et al. Reinventing germanium avalanche photodetector for nanophotonic on-chip optical interconnects. Nature 464, 80–84 (2010).

Virot, L. et al. Germanium avalanche receiver for low power interconnects. Nat. Commun. 5, 4957 (2014).

Cao, H. et al. Ultrahigh gain-bandwidth product Ge/Si avalanche photodetector assisted by nonuniform electric field distribution. In ECOC 2024; 50th European Conference on Optical Communication. 1964−1967 (VDE, 2024).

Cheng, C. et al. A 112 Gbps silicon-germanium avalanche photodiode with ultra-high gain-bandwidth product. In 2025 Optical Fiber Communications Conference and Exhibition (OFC). 1−3 (IEEE, 2025).

Hu, X. et al. High-performance germanium avalanche photodetector for 100 Gbit/s photonics receivers. Opt. Lett. 46, 3837–3840 (2021).

Peng, Y. et al. An 8 × 160 Gb s-1 all-silicon avalanche photodiode chip. Nat. Photonics 18, 928–934 (2024).

Shi, Y. et al. 103 GHz germanium-on-silicon photodiode enabled by an optimized U-shaped electrode. Photonics Res. 12, 1–6 (2024).

Lischke, S. et al. Ge Photodiode with -3 dB OE Bandwidth of 110 GHz for PIC and ePIC Platforms. In 2020 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM). 7.3.1-7.3.4. (2014).

Wang, B. et al. A compact model for Si-Ge avalanche photodiodes over a wide range of multiplication gain. J. Lightwave Technol. 37, 3229–3235 (2019).

Chen, G. et al. High speed and high power polarization insensitive germanium photodetector with lumped structure. Opt. Express 24, 10030–10039 (2016).

Cui, J. et al. High-performance Ge-on-Si photodetector with optimized DBR location. Opt. Lett. 42, 5141–5144 (2017).

Wang, B. et al. 64 Gb/s low-voltage waveguide SiGe avalanche photodiodes with distributed bragg reflectors. Photonics Res. 8, 1118–1123 (2020).

He, A. et al. Low loss, large bandwidth fiber-chip edge couplers based on silicon-on-insulator platform. J. Lightwave Technol. 38, 4780–4786 (2020).

Zhu, X. et al. Low-loss fiber-to-chip edge coupler for silicon nitride integrated circuits. Opt. Express 31, 10525–10532 (2023).

Dai, D. et al. Resonant normal-incidence separate-absorption-charge-multiplication Ge/Si avalanche photodiodes. Opt. Express 17, 16549–16557 (2009).

Gao, J. et al. Carrier transport dynamics in high speed black phosphorus photodetectors. ACS Photonics 5, 1412–1417 (2018).

Tan, M. et al. Co-packaged optics (CPO): status, challenges, and solutions. Front. Optoelectron. 16, 1 (2023).

Zhou, X. et al. Thin Al1−xGaxAs0.56Sb0.44 diodes with extremely weak temperature dependence of avalanche breakdown. R. Soc. open Sci. 4, 170071 (2017).

Yuan, Y. et al. 64 Gbps PAM4 Si-Ge waveguide avalanche photodiodes with excellent temperature stability. J. Lightwave Technol. 38, 4857–4866 (2020).

Goh, Y. L. et al. InAlAs avalanche photodiode with type-II absorber for detection beyond 2 μm. In Infrared Technology and Applications XXXV. 1204−1213 (SPIE, 2009).

Zhao, Y. et al. Temperature dependence simulation and characterization for InP/InGaAs avalanche photodiodes. Front. Optoelectron. 11, 400–406 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFB2807601 received by Y.Y.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (62525505, 62135004 received by Y.Y.), Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2025AFA039 received by Y.Y.), Innovation Project of Optics Valley Laboratory (0VL2024ZD003 received by Y.Y.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S., and Y.Y. jointly conceived the idea. Y.S. conducted simulation and designed the chip. Y.S., M.Z., and Z.L. performed the experiments. All authors contributed to the discussion of experimental results. Y.S., and Y.Y. wrote the manuscript with co-authors. Y.Y. and X.Z. supervised and coordinated all the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Y., Zou, M., Li, Z. et al. Ultrafast avalanche photodiode exceeding 100 GHz bandwidth. Nat Commun 16, 11058 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66047-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66047-6