Abstract

We investigate the two- and many-body physics of ultracold polar molecules dressed by dual microwaves with distinct polarizations. Using Floquet theory and multichannel scattering calculations, we identify a regime with the largest elastic-to-inelastic scattering ratio, which is favorable for performing evaporative cooling. Furthermore, we derive and subsequently validate an effective interaction potential that accurately captures the dynamics of microwave-shielded polar molecules (MSPMs). We also explore the ground-state properties of the ultracold gases of MSPMs by computing physical quantities such as gas density, condensate fraction, momentum distribution, and second-order correlation. It is shown that the system supports a weakly correlated expanding gas state and a strongly correlated self-bound gas state. Since the dual-microwave scheme introduces an additional control knob and is essential for creating ultracold Bose gases of polar molecules, our work pave the way for studying the two- and many-body physics of the ultracold polar molecules dressed by dual microwaves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The realization of ultracold molecular gases has become a cornerstone for harnessing the potential of quantum technologies, including advancements in precision measurements1,2,3,4,5,6, ultracold chemistry7,8,9, quantum computing10,11,12,13,14,15, and quantum simulation16,17,18. Recent advances in microwave shielding techniques19,20,21,22,23,24,25 have enabled the creation of stable degenerate Fermi gases of NaK molecules26,27 and Bose-Einstein condensates (BECs) of NaCs molecules28. These breakthroughs highlight the transformative potential of microwave-shielded polar molecules (MSPMs) in both fundamental and applied quantum science.

For fermionic molecules such as NaK, a circularly polarized (σ+) microwave field generates tunable dipole-dipole interactions (DDIs) and creates a robust shielding potential that suppresses losses via the formation of four-body complexes. With Pauli blocking effectively reducing three-body losses, this shielding facilitates evaporative cooling to achieve ultracold NaK tetramers29,30. This opens avenues for realizing p-wave superfluidity31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, a critical component for topological quantum computing41,42. In contrast, bosonic molecules encounter significant challenges due to strong attractive dipolar interactions under a σ+-polarized microwave field, which intensify three-body losses and impede BEC formation24. This obstacle has been successfully overcome experimentally using a dual-microwave approach, where an additional linearly polarized (π) microwave field reduces the attractive forces, substantially suppressing three-body losses43 and enabling the formation of stable NaCs molecular BECs28. In addition, the ground-state properties of the ultracold Bose gases of MSPMs have been theoretically investigated44,45.

Despite these experimental successes, the underlying shielding mechanism remains incompletely understood since, in the presence of the second microwave, the time dependence of DDIs cannot be eliminated through rotations, which poses a serious challenge to theoretical treatments. Furthermore, dual microwave fields enable molecules to absorb photons from one field and emit photons to the other, resulting in an energy-exchange process that drives inelastic scattering and heating. Thus, the dual-microwave scheme may jeopardize evaporative cooling. To achieve an optimal balance between suppressing inelastic losses while preserving elastic scattering and shielding, it is necessary to perform a detailed Floquet theoretical analysis of scattering dynamics governed by a time-dependent Hamiltonian.

In this study, we develop a universal theoretical framework to explore the scattering and many-body physics of polar molecules under dual microwave fields. By integrating Floquet theory with multichannel scattering calculations for time-dependent interactions, we compute (in)elastic scattering rates and identify regimes where the elastic-to-inelastic scattering ratio is maximized. In this regime, the evaporative cooling efficiency can be significantly enhanced, in agreement with the experimental choice. Moreover, to elucidate the shielding mechanism and characterize the key interaction dynamics of MSPMs, we analytically derive the effective potential between MSPMs by taking into account all second-order contributions in the Floquet formulation. The validity of the effective potential is thoroughly checked via the multi-channel scattering calculations. Finally, we explore the ground-state properties of an ultracold NaCs gas by employing a variational wave function incorporating the Jastrow correlation44. By tuning the Rabi frequency of the π-polarized microwave, we find, in analogy to the states found in ultracold NaRb gases44,45, a weakly correlated expanding gas state and a strongly correlated self-bound gas state. Here, when the confining potential is switched off, the gas undergoes a continuous expansion in the former state, while it remains self-bound in the latter. The condensate fractions and momentum distributions of both states are also computed. In a recent work46, the authors theoretically study the two-body problems of the same system using the second-quantized approach where microwave fields are treated as quantized modes. Their results agree with ours.

Results

Model for a single molecule dressed by dual microwaves

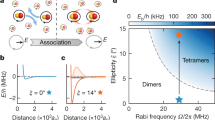

We consider an ultracold gas of NaCs molecules in the 1Σ(v = 0) state which can be treated as a rigid rotor. Under ultracold temperature, we may focus on the lowest (\(\left\vert \, J\,,{M}_{J}\right\rangle=\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle\)) and the first excited (\(\left\vert\, J=1,{M}_{J}=1,0,-1\right\rangle\)) rotational manifolds, which are split by energy ℏωe. Each molecule possesses an electric dipole moment \(d\hat{{{{\bf{d}}}}}\) that couples to the external fields. Here, d = 4.6 Debye is the permanent dipole moment in the molecular frame and \(\hat{{{{\bf{d}}}}}\) is the unit vector along the internuclear axis of the molecule. To achieve shielding with dual microwaves, a σ+- and a π-polarized microwaves are applied to couple the transitions \(\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left\vert 1,1\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left\vert 1,0\right\rangle\), respectively (see Fig. 1a). The frequencies of the σ+ and π microwaves, i.e., ω+ and ωπ, respectively, are blue detuned from the transition frequency ωe. As a result, both detunings, δ+ ≡ ωe − ω+ and δπ ≡ ωe − ωπ, are negative. In the frame co-rotating with microwave fields, the internal-state Hamiltonian for a single molecule is time-independent and takes the form

where Ω+ and Ωπ are the Rabi frequencies of the σ+ and π microwaves, respectively. It should be noted that in Eq. (1), we have neglected the hyperfine states of the molecules, as they are suppressed by the magnetic field typically presented in experiments28.

a Level structure for a single molecule dressed by dual microwaves. b Two-molecule states in the symmetric subspace. Mν is the quantum number associated with the two-molecules states [see Eq. (18)].

The single-molecule Hamiltonian \({\hat{h}}_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\) can be analytically diagonalized by a unitary transformation U1(α, β, γ) which is conveniently parameterized by three Euler angles α, β, and γ [see Section S1 in Supplementary Information (SI) for details]. The columns of U1 are the eigenvectors of \({\hat{h}}_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\) which, from left to right, are denoted as \(\left\vert+\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert -1\right\rangle (\equiv \left\vert 1,-1\right\rangle )\), \(\left\vert -\right\rangle\), and \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) (see Fig. 1a). The corresponding eigenenergies are denoted as E+, E−1 = δ+, E−, and E0, respectively. We note that in the limit Ωπ → 0 the eigenstates and eigenenergies can be expressed explicitly as \(\left\vert+\right\rangle \to \cos \alpha \left\vert 0,0\right\rangle+\sin \alpha \left\vert 1,1\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert -\right\rangle \to \sin \alpha \left\vert 0,0\right\rangle -\cos \alpha \left\vert 1,1\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle \to \left\vert 1,0\right\rangle\), E± → (δ+ ± Ωeff)/2, and E0 → δπ, where \({\Omega }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}=\sqrt{{\delta }_{+}^{2}+{\Omega }_{+}^{2}}\) and the Euler angles are known analytically, i.e., \((\alpha,\beta,\gamma )=\left(\arccos {[(1-{\delta }_{+}/{\Omega }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}})/2]}^{1/2},0,0\right)\).

In the presence of double microwave fields, we assign quantum numbers to the internal states based on both the angular momentum of internal states projected along the z-axis and microwave polarizations. The quantum number for the state \(\left\vert 1,-1\right\rangle\) is −1, as no microwave photon is involved. For the state \(\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle\), the quantum number is + 1, since both a σ+- and a π-polarized microwave field are applied. A transition from \(\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle\) to the state \(\left\vert 1,0\right\rangle\) occurs by the absorption of a π-polarized photon, with a σ+-polarized photon still present, resulting in the quantum number +1 for \(\left\vert 1,0\right\rangle\). In the transition from \(\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle\) to \(\left\vert 1,1\right\rangle\), the polarization of the σ+ microwave field is transferred to the angular momentum of \(\left\vert 1,1\right\rangle\), giving it the quantum number +1. Therefore, we assign the quantum numbers {1, −1, 1, 1} to the states \(\left\vert+\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert 1,-1\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert -\right\rangle\), and \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\), respectively.

To simplify the scenario, the Rabi frequency and detuning of the σ+-polarized microwave are fixed, throughout this work, at Ω+ = 2π × 7.9 MHz and δ+ = − 2π × 8 MHz, respectively. And, unless otherwise specified, the detuning of the π-polarized microwave is chosen as δπ = −2π × 10MHz. These setups leave the Rabi frequency of the π-polarized microwave Ωπ as a free parameter.

Model for two interacting molecules dressed by dual microwaves

For two molecules with dipole moments \(d{\hat{{{{\bf{d}}}}}}_{1}\) and \(d{\hat{{{{\bf{d}}}}}}_{2}\), the inter-molecular DDI is

where \(\eta=\sqrt{8\pi /15}\,{d}^{2}/{\epsilon }_{0}\) with ϵ0 being the electric permittivity of vacuum, r = ∣r∣, \({Y}_{2m}(\hat{{{{\bf{r}}}}})\) are spherical harmonics, and Σ2,m are components of the rank-2 spherical tensor defined as \({\Sigma }_{2,0}=({\hat{d}}_{1}^{+}{\hat{d}}_{2}^{-}+{\hat{d}}_{1}^{-}{\hat{d}}_{2}^{+}+2{\hat{d}}_{1}^{0}{\hat{d}}_{2}^{0})/\sqrt{6}\), \({\Sigma }_{2,\pm 1}=({\hat{d}}_{1}^{\pm }{\hat{d}}_{2}^{0}+{\hat{d}}_{1}^{0}{\hat{d}}_{2}^{\pm })/\sqrt{2}\), and \({\Sigma }_{2,\pm 2}={\hat{d}}_{1}^{\pm }{\hat{d}}_{2}^{\pm }\) with \({\hat{d}}_{j}^{\pm }={Y}_{1,\pm 1}({\hat{{{{\bf{d}}}}}}_{j})\) and \({\hat{d}}_{j}^{0}={Y}_{1,0}({\hat{{{{\bf{d}}}}}}_{j})\). In the rotating frame, \({\hat{d}}_{j}^{\pm }\) and \({\hat{d}}_{j}^{0}\) become time-dependent. In fact, in the basis \(\left\vert\, J\,,{M}_{J}\right\rangle\), these operators can be written explicitly as

After substituting the above spherical components of the vector into Σ2m, we find

where, according to the rotating-wave approximation, we have retained the time-dependent terms with the lower frequency ω = ω+ − ωπ (typically ranging from kHz to MHz), while neglecting those with higher frequencies ω+ and ωπ (on the order of GHz), as ω+,π are much larger than all other energy scales in the system.

To proceed further, the Hamiltonian for the relative motion of two molecules is

where M is the mass of the molecule and \({\hat{h}}_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}(j)\) denotes the internal-state Hamiltonian of the jth molecule. And we have explicitly expressed Vdd as a function of t in the rotating frame. Since \({\hat{H}}_{2}\) possesses a parity symmetry, the symmetric and antisymmetric two-particle internal states are decoupled in the Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}_{2}\). We shall only focus on the ten-dimensional symmetric subspace in which the microwave shielded two-molecule state \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle \equiv \left\vert +\right\rangle \otimes \left\vert +\right\rangle\) lies. Further simplification can be made by noting that \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) only couples to the following eight two-molecule states (see the schematic plot in Fig. 1b): \(\vert 2 \rangle \equiv { \vert +,-1 \rangle }_{{{{\rm{sys}}}}}\), \(\left\vert 3\right\rangle \equiv {\left \vert +,-\right\rangle }_{{{{\rm{sys}}}}}\), \(\left\vert 4\right\rangle \equiv {\left \vert +,0\right\rangle }_{{{{\rm{sys}}}}}\), \(\left\vert 5\right\rangle \equiv {\left \vert -1 ,-\right\rangle }_{{{{\rm{sys}}}}}\), \(\left\vert 6\right\rangle \equiv {\left\vert -1,0\right\rangle }_{{{{\rm{sys}}}}}\), \(\left\vert 7\right\rangle \equiv \left\vert -\right\rangle \otimes \left\vert -\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert 8\right\rangle={\left\vert -,0\right\rangle }_{{{{\rm{sys}}}}}\), and \(\left\vert 9\right\rangle \equiv \left\vert 0\right\rangle \otimes \left\vert 0\right\rangle\), where \({\vert i,j }_{{{{\rm{sys}}}}}=(\left\vert i\right\rangle \otimes \left\vert\, j\right\rangle+\left\vert\, j\right\rangle \otimes \left\vert i\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) represents the symmetrized two-molecule state. The corresponding energies of these two-particle states are denoted as \({E}_{\nu }^{(\infty )}\). As a result, these nine two-molecule states form a 9-dimensional (9D) symmetric subspace, \({{{{\mathcal{S}}}}}_{9}\equiv {{{\rm{span}}}}{\{\left\vert \nu \right\rangle \}}_{\nu=1}^{9}\). Now, since we focus on system with all molecules being prepared in the microwave shielded \(\left\vert +\right\rangle\) state, we may project the interaction Vdd(r) onto the two-molecule subspace \({{{{\mathcal{S}}}}}_{9}\).

In an attempt to eliminate the time dependence of \({\hat{H}}_{2}\), we introduce, in \({{{{\mathcal{S}}}}}_{9}\), a unitary transformation defined by the diagonal matrix

A straightforward calculation shows that the Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}_{2}\) is transformed into

where \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{(\infty )}\) is a diagonal matrix with elements being the energies of the asymptotical state \(\left\vert \nu \right\rangle\) with respect to that of the \(\left\vert \nu=1\right\rangle\) state, i.e., \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\nu {\nu }^{{\prime} }}^{(\infty )}=({E}_{\nu }^{(\infty )}-2{E}_{+}){\delta }_{\nu {\nu }^{{\prime} }}-i{({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{2}^{{{\dagger}} }{\partial }_{t}{{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{2})}_{\nu {\nu }^{{\prime} }}\). Moreover, the two-body interaction in the basis \(\{\left\vert \nu \right\rangle \}\) is

which is decomposed into components according to the time dependence eisωt. In particular, the components satisfy \({{{{\mathcal{V}}}}}_{-s}({{{\bf{r}}}})={{{{\mathcal{V}}}}}_{s}^{{{\dagger}} }({{{\bf{r}}}})\) and

where \({\Sigma }_{2,m}^{(s)}\) are the terms in \({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{2}^{{{\dagger}} }(t){\Sigma }_{2,m}{{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{2}(t)\) associated with the time dependence eisωt. For completeness, the matrix elements of Σ2,m are listed in Section S2 of SI, which satisfy \({\Sigma }_{2,-m}^{(s)}={(-1)}^{m}{\Sigma }_{2,m}^{(-s){{\dagger}} }\).

Although the expression for the interaction Hamiltonian \({{{\mathcal{V}}}}\) may appear very complicated, each term has a clear physical interpretation. To see the physical processes associated with the interaction, we explicitly write the interaction Hamiltonian in the basis \(\{\left\vert \nu \right\rangle \}\), namely,

Next, we note that, under the transformation in Eq. (10), the state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) acquires a phase factor \({e}^{-i\omega t}={e}^{-i{\omega }_{+}t}{e}^{i{\omega }_{\pi }t}\), corresponding to the annihilation of a σ+-polarized photon and the creation of a π-polarized photon. As a result, the quantum number of \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) is reduced by 1. Therefore, we assign the quantum numbers {1, − 1, 1, 0} to the states \(\{\left\vert +\right\rangle,\left\vert -1\right\rangle,\left\vert -\right\rangle,\left\vert 0\right\rangle \}\), representing the z-component of the angular momentum for both the internal states and the microwave fields. Then the quantum numbers associated with the two-molecule states \(\left\vert \nu \right\rangle\) are Mν = 2, 0, 2, 1, 0, − 1, 2, 1, and 0 for ν = 1 to 9, respectively (see Fig. 1b). Now, by inspection, we find that the matrix element \({\left({\Sigma }_{2,m}^{(s)}\right)}_{\nu {\nu }^{{\prime} }}\) is nonzero only when the selection rule

is satisfied. To proceed further, we interpret the phase factor \({e}^{is\omega t}={e}^{is{\omega }_{+}t}{e}^{-is{\omega }_{\pi }t}\) in Eq. (17) as the creation of s σ+-microwave photons and the annihilation of s π-microwave photons. As a result, the net change of the quanta associated with the polarization of the microwave photons is s. It is now clear that the selection rule (18) explicitly represents a change in internal angular momenta (i.e., \({M}_{{\nu }^{{\prime} }}\to {M}_{\nu }\)) during the transition from the state \(\left\vert {\nu }^{{\prime} }\right\rangle\) to the state \(\left\vert \nu \right\rangle\) via the emission of s circular polarizations and the absorption of m angular momentum quanta from the orbital motion. Thus, the selection rule (18) reveals a conservation of the total angular momentum, i.e., the sum of microwave polarizations, the angular momentum of internal states \(\left\vert \nu \right\rangle\), and the orbital angular momentum, projected along the z axis.

Effective potential between MSPMs

Within the framework of the Floquet theory (see Methods), we may derive a time-independent effective intermolecular potential between microwave-shielded \(\left\vert +\right\rangle\) molecules. The effective potential offers a precise description of the two-body interaction between MSPMs at ultracold temperatures, providing an intuitive framework for understanding key physical phenomena, e.g., the cancellation of dipolar interactions and the dependence of the scattering length on Rabi frequencies. For two-body problems, using the effective potential is more efficient in studying elastic scattering, as it circumvents the computational complexity of full multi-channel calculations. This approach is particularly useful for guiding experiments focused on shape resonances and two-molecule bound states27,29, as well as for preparing stable molecular BECs28. Moreover, in many-body physics, employing the full time-dependent multi-channel interaction becomes computationally intractable. The effective potential thus offers a compact and universal framework for describing interactions between MSPMs, enabling systematic studies of their many-body physics.

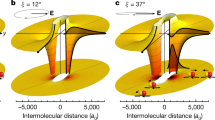

To this end, we first note that the internal-state dynamics is much faster than the center-of-mass motion of the molecules, which allows us to employ the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. Then, for a given r, we diagonalize, in the Floquet space (see Methods), the potential matrix V (i.e., the Floquet Hamiltonian H with the kinetic energy being neglected), giving rise to

where \(\left\vert {V}_{n,\nu }^{({{{\rm{ad}}}})}({{{\bf{r}}}})\right\rangle\) is the eigenstate and \({V}_{n,\nu }^{({{{\rm{ad}}}})}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) is the eigenenergy with n being the index for the Floquet sector. Physically, \(\left\vert {V}_{n,\nu }^{({{{\rm{ad}}}})}({{{\bf{r}}}})\right\rangle\) is the state that adiabatically connects to the asymptotical state \(\left\vert n,\nu \right\rangle\), i.e., the two-molecule state \(\left\vert \nu \right\rangle\) in the n-th Floquet sector. In particular, we focus on the eigenstate adiabatically connecting to \(\left\vert ++\right\rangle\) with n = 0 as r → ∞. The corresponding eigenenergy \({V}_{0,1}^{({{{\rm{ad}}}})}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) is then the effective potential between two microwave-shielded molecules.

Alternatively, we may analytically derive a highly accurate effective potential, Veff(r), through second-order perturbation theory. For this purpose, we note that the first-order correction to the energy of the \(\left\vert ++\right\rangle\) state in the sector n = 0 is

where

For fixed δ+, Ω+, and δπ, the Euler angle β increases with Ωπ. As Ωπ increases to the threshold value Ωc, β reaches \({\beta }_{c}=\arccos (1/3)/2\), resulting in complete cancellation of the effective DDI, i.e., C3 = 0. Next, the second-order correction can be formally expressed as

where the primed sum excludes the term with (n, ν) = (0, 1), \({\left({{{\bf{H}}}}\right)}_{(0,1),(n,\nu )}\) is the matrix element between the channels (0, 1) and (n, ν), and \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\nu \nu }^{(\infty )}-n\omega\) is the unperturbed energy of the channel (n, ν). Using Eq. (32), \({\left({{{\bf{H}}}}\right)}_{(0,1),(n,\nu )}\) reduces to \({\left({{{{\mathcal{V}}}}}_{n}({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}})\right)}_{1\nu }\). By carefully examining the matrix elements of \({{{{\mathcal{V}}}}}_{n}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) as shown in Eq. (17) and in Section S2 of SI, it turns out that, in Eq. (22), only a finite number of terms contribute. Moreover, the angular dependence of the second-order corrections must be of the forms: \({\left\vert {Y}_{20}(\hat{{{{\bf{r}}}}})\right\vert }^{2}\), \({\left\vert {Y}_{21}(\hat{{{{\bf{r}}}}})\right\vert }^{2}\), and \({\left\vert {Y}_{22}(\hat{{{{\bf{r}}}}})\right\vert }^{2}\). After collecting all terms contributing to the second-order correction, the effective potential can now be approximated as

where C6 = 15η2w2/(32π) and w0, w1, and w2 [see Section S3 in SI for analytical expressions] measure the relative contributions from the terms \({\left\vert {Y}_{20}(\hat{{{{\bf{r}}}}})\right\vert }^{2}\), \({\left\vert {Y}_{21}(\hat{{{{\bf{r}}}}})\right\vert }^{2}\), and \({\left\vert {Y}_{22}(\hat{{{{\bf{r}}}}})\right\vert }^{2}\), respectively. It is instructive to consider the limiting case with the π-polarized microwave being switched off. In fact, in the limit Ωπ → 0, it can then be analytically shown that \({C}_{3}\to {d}^{2}/[48\pi {\epsilon }_{0}(1+{\delta }_{+}^{2})]\), \({C}_{6}\to {d}^{4}/[128{\pi }^{2}{\epsilon }_{0}^{2}{(1+{\delta }_{+}^{2})}^{3/2}]\), w1/w2 → 2 and w0/w2 become negligibly small, which leads to exactly the effective potential derived in ref. 40.

As shown in Eq. (23), the effective potential is completely specified by the parameters characterizing the strength, i.e, C3 and C6, and the parameters characterizing the anisotropy of the shielding core, i.e., w0/w2 and w1/w2. Figure 2a plots the Ωπ dependence of C3 and C6. As can be seen, C3 is a monotonically decreasing function of Ωπ, indicating that the π-polarized microwave indeed lowers the attraction of the negated dipolar interaction on the xy plane. In particular, the dipolar interaction is completely canceled out at \({\Omega }_{\pi }={\Omega }_{\pi }^{(c)}\) ( ≈ 2π × 6.65 MHz). Further increasing Ωπ then leads to a conventional dipolar interaction (C3 < 0) that is repulsive in the xy plane and attractive along the z axis. In contrast, C6 is a monotonically increasing function of Ωπ and, as a result of second-order perturbation, the value of C6 is always positive, clearly indicating that, similar to the σ+-polarized microwave, the π-polarized microwave also gives rise to shielding.

a C3 and C6 as functions of Ωπ. b w0 and w1 as functions of Ωπ. c Comparison of Veff (r) with \({V}_{0,1}^{({{{\rm{ad}}}})}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) at θ = π/2 for Ωπ/(2π) = 6.5, 5.9, and 4 MHz (for three sets of curves in descending order). The dashed lines are obtained by numerically fitting \({V}_{0,1}^{({{{\rm{ad}}}})}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) using Eq. (23).

In Fig. 2b, we plot the ratios w0/w2 and w1/w2 as functions of Ωπ. At the limit Ωπ → 0, w0/w2 becomes negligibly small such that the effective potential (23) reduces to that derived in ref. 40. However, the w0 term plays an important role at large Ωπ. To see this, we consider the effective potential along the z axis, i.e.,

where only the w0 term contributes to the 1/r6 shielding. Therefore, for negative C3, the w0 term is the only source providing shielding.

Finally, we compare, in Fig. 2c, the effective potential Veff(r) (dash-dotted lines) with the adiabatic potential \({V}_{0,1}^{{{{\rm{(ad)}}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) (solid lines) in the xy plane for various Ωπ’s. Here, for convenience, we have introduced the length unit r0 = 103a0 with a0 being the Bohr radius. Apparently, very good agreement is achieved for large Ωπ. Although the discrepancy seems to increase as Ωπ is lowered, the quality of the effective potential, as shown by the dashed lines in Fig. 2c, can be improved by numerically fitting the adiabatic potential according to Eq. (23). As a result, one can always obtain the analytic expression for a highly accurate effective potential which plays an important role in studying the two- and many-body physics.

Scattering properties

We solve the two-body scattering problem within the framework of the Floquet theory (see “Methods”), which allows us to compute the elastic and inelastic scattering rates of particular importance in experiments. In Fig. 3a, we map out the s-wave scattering cross section \({\sigma }_{010,010}^{(0)}\) in the Ωπ-δπ plane, where \({\sigma }_{n\nu l,{n}_{0}{\nu }_{0}{l}_{0}}^{({m}_{0})}\) denotes the scattering cross section from the incident channel (n0ν0l0m0) to the outgoing channel (nνlm0). The dashed line marks the cancellation Rabi frequency \({\Omega }_{\pi }^{(c)}\) along which the effective dipolar interaction is completely canceled out. As a result, molecules only experience a repulsive shielding potential during scattering, and \({\sigma }_{010,010}^{(0)}\) along the cancellation line forms a small ridge. More interestingly, on the Ωπ-δπ plane, there also exist four other ridges with much larger heights where the scattering cross section \({\sigma }_{010,010}^{(0)}\) is peaked. As shall be shown in Fig. 4a, these ridges represent the shape resonances due to the formation of bound states.

a Scattering cross section \({\sigma }_{010,010}^{(0)}\) as a function of Ωπ and δπ. DDI is completely canceled along the black dashed line. b \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{el}}}})}\), \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{inel}}}})}\), and γ versus Ωπ with δπ/(2π) = 10 MHz. The vertical dotted lines mark the positions of the resonances and the vertical dashed line marks the position of \({\Omega }_{\pi }^{(c)}\). The narrow peak at Ωπ/(2π) ≈ 11 MHz is due to the m0 = ± 1 resonances.

a \({a}_{0,0}^{(0)}\) and \({a}_{010,010}^{(0)}\) versus Ωπ. The inset is the zoom-in plot for the s-wave scattering length in the vicinity of \({\Omega }_{\pi }^{(c)}\). b \({a}_{2,2}^{(1)}\), \({a}_{012,012}^{(1)}\), and \({a}_{012,012}^{(-1)}\) versus Ωπ. The inset is the zoom-in plot around the scattering resonance with m0 = ± 1. c \({a}_{2,2}^{(2)}\), \({a}_{012,012}^{(2)}\), and \({a}_{012,012}^{(-2)}\) versus Ωπ.

Next, we plot, in Fig. 3b, the elastic scattering rate \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{el}}}})}\), the inelastic scattering rate \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{inel}}}})}\), and the ratio \(\gamma \equiv {\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{el}}}})}/{\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{inel}}}})}\) as functions of Ωπ for δπ/(2π) = 10MHz. Because the s wave makes the largest contribution to the total elastic cross section, \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{el}}}})}\) is roughly proportional to \({[{a}_{010,010}^{(0)}]}^{2}\). Consequently, \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{el}}}})}\) peaks at the shape resonances and at the cancellation point. For the inelastic scatterings, since the two-molecule bound states imply stronger couplings between the incident channel (n, ν) = (0, 1) and other interaction channels, it is seen that \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{inel}}}})}\) is also peaked at the shape resonances. Interestingly, \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{inel}}}})}\) is minimized at the cancellation point due to the purely repulsive intermolecular potential. Finally, for the good-to-bad collision ratio γ, since \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{el}}}})}\) is at least one order of magnitude larger than \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{inel}}}})}\), γ reaches its local maxima at the shape resonances. However, the global maximum of γ is achieved at the cancellation point where \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{inel}}}})}\) is minimized. Thus, we identify a regime where it is most efficient for performing evaporative cooling. Remarkably, this regime is in good agreement with the choice of the experiment28.

The scattering calculations also allow us to further justify the effective potential. For this purpose, we compare, in Fig. 4, the scattering lengths computed with the single- and multi-channel models for various m0. More specifically, Fig. 4a plots the s-wave scattering lengths, \({a}_{0,0}^{(0)}\) and \({a}_{010,010}^{(0)}\), as functions of Ωπ. Close to the dipole cancellation point, very good agreement is achieved between the single- and multi-channel calculations. The difference then increases as Ωπ moves away from the cancellation point. In particular, the discrepancy becomes pronounced either in the strong attractive dipolar interaction regime (small Ωπ) or in the vicinity of scattering resonances. Interestingly, the Ωπ dependence of the s-wave scattering lengths can be readily understood using the effective potential. For this purpose, we start with the cancellation point, i.e., \({\Omega }_{\pi }={\Omega }_{\pi }^{(c)}\), where only the C6/r6 shielding potential survives. Consequently, the s-wave scattering length at \({\Omega }_{\pi }^{(c)}\) is always positive, and, in particular, it is around 2.2r0 in Fig. 4a. As Ωπ deviates from \({\Omega }_{\pi }^{(c)}\), the C3 term is turned on. Since the dipolar interaction is always partially attractive, the s-wave scattering length decreases on both sides of \({\Omega }_{\pi }^{(c)}\). Eventually, as Ωπ deviates sufficiently far away from \({\Omega }_{\pi }^{(c)}\), scattering resonances are experienced on both sides of \({\Omega }_{\pi }^{(c)}\), indicating the formation of the bound states. As Ωπ is further varied, more resonances can be encountered.

For a more comprehensive validation, we further compare the scattering lengths corresponding to the partial wave with l0 = 2 and ∣m0∣ = 1 in Fig. 4b. As can be seen, the agreement achieved here is even better than that in the m0 = 0 case as all curves are now visually indistinguishable. Indeed, the discrepancy can only be found in the zoomed-in plot of the scattering resonance at Ωπ/(2π) ≈ 11 MHz (see the inset of Fig. 4a). As ∣m0∣ further increases to 2 in Fig. 4c, the discrepancies between \({a}_{2,2}^{(2)}\) and \({a}_{012,012}^{(\pm 1)}\) completely disappear.

On the other hand, the level of agreement achieved between \({a}_{{l}_{0},{l}_{0}}^{({m}_{0})}\) and \({a}_{01{l}_{0},01{l}_{0}}^{({m}_{0})}\) also justifies neglecting the induced gauge potential, which combined with the adiabatic potential gives rise to a higher-order approximation, Vtot, for the intermolecular potential between MSPMs. Indeed, as shown in Section S4 of SI, the leading contributions from the gauge potential scale as 1/r8, indicating that the gauge potential only plays a role at short distances. As a result, one can hardly see the contribution of the gauge potential to the low-energy scatterings in Fig. 4. Moreover, because the gauge potential breaks the time-reversal symmetry, Vtot explicitly depends on the magnetic quantum number m0 (see Section S4 in SI for details) such that the deviation of Vtot − Veff increases as ∣m0∣ increases. However, from the scattering calculations we see that the discrepancy between \({a}_{{l}_{0},{l}_{0}}^{({m}_{0})}\) and \({a}_{01{l}_{0},01{l}_{0}}^{({m}_{0})}\) diminishes as m0 increases. The above observations can be understood by noting that incident molecules with large ∣m0∣ also possess a large angular momentum (l0 ≥ ∣m0∣). As a result, they experience a strong centrifugal potential, l0(l0 + 1)/r2, which keeps the molecules far apart and reduces the influence of the gauge potential for low-energy scatterings. More importantly, the scattering calculations clearly indicate that the gauge potential barely plays a role in the low-energy scatterings between MSPMs.

Here we would like to remark on a recent work47 in which the authors find that the gauge potential is essential for trapped polar molecules with trap frequency as high as (2π) × 1 MHz. From our analyses, this is not unexpected since, given such a high trap frequency, the corresponding incident energy allows two molecules to get sufficiently close to each other where the discrepancy between Veff and Vtot is significant (see Supplementary Fig. 1. and the analysis in Section S4 of SI). However, such a strong confinement induces a small distance between molecules, leading to a dramatic increase in loss and significantly shortening the lifetime of the molecular gas.

Many-body properties

To perform a quantitative comparison with the experimental measurements28, we investigate the many-body properties of an ultracold gas of N NaCs molecules trapped in a harmonic potential \(V({{{\bf{r}}}})=M[{\omega }_{\perp }^{2}({x}^{2}+{y}^{2})+{\omega }_{z}^{2}{z}^{2}]/2\), where ω⊥ and ωz are the transverse and axial trap frequencies, respectively. This study not only allows us to validate the effectiveness of the effective potential and our many-body framework, but also provides insights into exotic many-body phases, ranging from weak to strong DDIs, by tuning Ωπ, which may be observed in upcoming experiments.

For the results presented below, we choose N = 100 and ωz = 2π × 58 Hz. These setups reduce the control parameters of the system to Ωπ and ω⊥. We focus on two typical Rabi frequencies Ωπ = 2π × 5.9 and 2π × 6.5 MHz which, as shall be shown, give rise to self-bound and expanding gas states, respectively. The radial harmonic trap is switched on only for the expanding states and the frequency is set to ω⊥/(2π) = 33.6 Hz. Finally, for convenience, we introduce \({\varepsilon }_{0}\equiv {\hslash }^{2}/(M{r}_{0}^{2})\) as the unit of energy.

Figure 5 a,b plot the total and condensate densities for the expanding and self-bound states, respectively. Here, the condensate density can be obtained by diagonalizing the first-order correlation function, i.e., \({G}_{1}({{{\bf{r}}}},{{{{\bf{r}}}}}^{{\prime} })=\left\langle {\Psi }_{N}\right\vert {\hat{\psi }}^{{{\dagger}} }({{{{\bf{r}}}}}^{{\prime} })\hat{\psi }({{{\bf{r}}}})\left\vert {\Psi }_{N}\right\rangle={\sum }_{\ell \ge 0}{N}_{\ell }{\bar{\varphi }}_{\ell }({{{\bf{r}}}}){\bar{\varphi }}_{\ell }^{*}({{{{\bf{r}}}}}^{{\prime} })\), where \(\hat{\psi }({{{\bf{r}}}})\) is the field operator, \(\left\vert {\Psi }_{N}\right\rangle\) is the N-body wave function (see Methods), and Nℓ (sorted in descending order) is the occupation number in the normalized mode \({\bar{\varphi }}_{\ell }({{{\bf{r}}}})\). Then N0 is the number of molecules in the condensation, \({n}_{c}({{{\bf{r}}}})={N}_{0}| {\bar{\varphi }}_{0}({{{\bf{r}}}}){| }^{2}\) is the corresponding condensate density, and fc = N0/N is the condensate fraction.

For the expanding state, the radial and axial widths of the total density are, respectively, σρ = 43.2r0 and σz = 25.3r0, which, due to the repulsive nature of the interaction, are larger than the corresponding harmonic oscillator widths a⊥ = 26.2r0 and az = 19.8r0 of the trap. Here, the radial and axial widths of the density are defined according to \({\sigma }_{\rho }={\left[2\pi {N}^{-1}\int\,d{\rho} dz{\rho }^{3}n({{{\bf{r}}}})\right]}^{1/2}\) and \({\sigma }_{z}={\left[4\pi {N}^{-1}\int\,d{\rho} dz\rho {z}^{2}n({{{\bf{r}}}})\right]}^{1/2}\), respectively. Given that the peak density of the gas is np = 1.5 × 1012cm−3 and the scattering length is as = 2.16 × 103a0, it can be estimated that \(n{a}_{s}^{3}=2.3\times 1{0}^{-3}\) ( ≪1), indicating that the gas is in the weak interaction regime. As a result, the condensation fraction can be as high as fc = 0.94.

For the self-bound state, due to the stronger attractive DDI in the xy plane, the widths of the gas dramatically reduce to σρ = 22.8r0 and σz = 5.1r0 even in the absence of the external trap. More interestingly, by examining the aspect ratios σρ/σz, it is found that the self-bound state is significantly flattened radially. This phenomenon is quite common in dipolar quantum gases. In fact, to reduce the interaction energy, dipolar gases always get stretched along the attractive direction of the dipolar interaction48,49,50. Moreover, as the peak density, np = 5.6 × 1013 cm−3, becomes dramatically higher than that of the expanding state, the condensate fraction reduces to fc = 0.53, indicating that the self-bound state corresponds to a more strongly correlated gas.

To measure many-body correlation, we calculate the normalized second-order correlation function

where \({G}_{2}({{{\bf{r}}}},{{{{\bf{r}}}}}^{{\prime} })=\left\langle \Psi \right\vert {\hat{\psi }}^{{{\dagger}} }({{{\bf{r}}}}){\hat{\psi }}^{{{\dagger}} }({{{{\bf{r}}}}}^{{\prime} })\hat{\psi }({{{{\bf{r}}}}}^{{\prime} })\hat{\psi }({{{\bf{r}}}})\left\vert \Psi \right\rangle\). Figure 6a,b plot, for two different Ωπ’s, g2(ρ, 0) and g2(0, z), respectively, where \({g}_{2}(\rho,z)\equiv {g}_{2}({{{\bf{r}}}},{{{{\bf{r}}}}}^{{\prime} }=0)\) due to the cylindrical symmetry. Generally, g2 vanishes at short distances due to the strong shielding potential and approaches unity at a large distance. This anti-bunching behavior reveals that each molecule is surrounded by holes at a short distance. Consequently, coherence can only be established as the distance between molecules is sufficiently large, which results in a reduced condensate fraction. Next, to understand the behaviors of g2 presented in Fig. 6, we recall that the dipolar interaction is much stronger with Ωπ/(2π) = 5.9 MHz and, in particular, the long-range interaction is nearly canceled for Ωπ/(2π) = 6.5 MHz. Then, it is natural to see (Fig. 6a) that g2(ρ, 0) approaches unity more rapidly for smaller Ωπ since it corresponds to a stronger attraction along the radial direction at a large distance. Moreover, although the interactions along the z axis are purely repulsive in both cases, a smaller Ωπ has a stronger interaction strength and a longer interaction range. Consequently, g2(0, z) with smaller Ωπ approaches unity more slowly (Fig. 6b). More interestingly, at ρ ≈ 20r0 where the density of the gases becomes negligibly small, we even observe the Friedel-like oscillation which, in contrast to the statistics origin in fermionic systems, appears due to the strong correlation.

For the experimental detection of the molecular condensates, we explore the momentum distribution of the gas. For all and condensed molecules, the momentum distributions are, respectively,

Figure 7a, b plot the momentum distributions \(\tilde{n}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) and \({\tilde{n}}_{c}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) of total and condensed molecules for Ωπ/(2π) = 6.5 and 5.9MHz. For larger Ωπ/(2π), \(\tilde{n}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) and \({\tilde{n}}_{c}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) are nearly identical along all directions due to the large condensate fraction; while for smaller Ωπ, discrepancy emerges between two distributions on the xy plane. In particular, condensed molecules dominate the low-k region, while uncondensed molecules (depletion) populate large k, leading to a bimodal momentum distribution \(\tilde{n(k)}\) even at zero temperature. It should be noted that, although \(\tilde{n}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) can be directly measured via time-of-flight imaging, the experimental observation of \({\tilde{n}}_{c}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) is highly nontrivial. Unlike atomic condensates whose \({\tilde{n}}_{c}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) can be derived from \(\tilde{n}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) by subtract the distribution of the thermal gas with temperature obtained through fitting the tail of \(\tilde{n}({{{\bf{k}}}})\), the momentum distribution of the uncondensed molecules at low k region cannot be deduced from that at large k, since its analytic expression is unknown. Particularly, the situation becomes more complicated at finite temperature.

Finally, we consider the integrated second-order correlation function

which is measurable in experiments. Particularly, we are interested in \({\bar{g}}_{2}(\rho )\equiv {\bar{g}}_{2}({{{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}},0)\) which possesses an axial symmetry. Figure 7c shows \({\bar{g}}_{2}(\rho )\) for two different Ωπ’s. As can be seen, although anti-bunching behaviors are observed, \({\bar{g}}_{2}(0)\) remains finite, which is in stark contrast to the three-dimensional g2(0, 0) presented in Fig. 6. By carefully examining Eq. (28), we find that the nonzero \({\bar{g}}_{2}(0)\) is clearly contributed by the second-order correlation of the form \({G}_{2}({{{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}},z;{{{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}},{z}^{{\prime} })\). Moreover, due to the stronger repulsion at short distances and the smaller width along the z axis, the gas with the smaller Ωπ experiences a stronger anti-bunching.

Discussion

We have studied the two- and many-body physics rotating polar molecules subjected to a σ+- and a π-polarized microwaves. With such a dual microwave configuration, the two-body interaction is periodically dependent on time, although the single-molecule Hamiltonian is time-independent under a suitable rotating frame. Consequently, we have to treat the two-body physics within the framework of Floquet theory. In particular, we compute (in)elastic scattering rates through the multi-channel scattering calculations, which allows us to identify regimes where the elastic-to-inelastic scattering ratio is optimized for evaporative cooling, in good agreement with the choice of the experiments. Moreover, we have analytically derived an effective potential between two MSPMs which, when applied to scattering problems, provides intuitive insights for the multi-channel scattering calculations. From many-body perspectives, our studies on the ground-state properties position MSPMs as a highly tunable platform for exploring novel many-body phenomena, transcending the paradigms of dilute atomic BECs51,52 and superfluid helium53,54.

Methods

Floquet formalism for multi-channel scatterings

The time periodicity of the Hamiltonian \(\hat{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}(t)\) suggests that we may tackle two-molecule physics using the Floquet theory. Specifically, the solution of the Schrödinger equation,

takes the “Floquet-Fourier” form

where ε is the quasi-energy of the state and \(\left\vert {\psi }_{n}\right\rangle\) is the time-independent harmonic component defined in the 9D Hilbert space \({{{{\mathcal{S}}}}}_{9}\). It follows from Eq. (29) that \(\left\vert {\psi }_{n}\right\rangle\) satisfy the time-independent eigenvalue equation:

where the Floquet Hamiltonian is

Introducing the vector \(\left\vert {{{\boldsymbol{\Psi }}}}\right\rangle={(\cdots,\left\vert {\psi }_{-1}\right\rangle,\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle,\left\vert {\psi }_{1}\right\rangle,\cdots )}^{T}\) for the Floquet space wavefunction, Eq. (31) can be rewritten in a more compact form as

where, in terms of 9 × 9 block matrices, the Floquet Hamiltonian H is a hepta-diagonal matrix. Thus, one may easily visualize the structure of the Schrödinger Eq. (31) through H.

With Eq. (31), the advantage of performing the transformation \({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{2}(t)\) is now understandable. Specifically, in the absence of the π-field, \({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{2}(t)\) leads to a time-independent \(\hat{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}\), i.e., \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{s}=0\) for all s ≠ 0, indicating that different Floquet sectors are decoupled and the eigenstates can be obtained directly by diagonalizing \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}\). Then, as the π-polarized microwave is gradually turned on to lower the attractive interaction on the xy plane, the transitions between different Floquet sectors are also switched on. Moreover, to maintain the shielding effect along all directions, the Rabi frequency of the π-polarized microwave has to be much smaller than that of the σ+-polarized microwave (see the discussion of the effective potential in Results). As a result, through the transformation \({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{2}\), we ensure that the transitions between different Floquet sectors in the presence of the π microwave are perturbation. This structure accelerates the convergence of numerical calculations.

In order to solve Eq. (31), we expand the eigenstate wavefunction \({\psi }_{n,\nu }({{{\bf{r}}}})=\left\langle \nu | {\psi }_{n}({{{\bf{r}}}})\right\rangle\) in the partial-wave basis as

where ϕnνl are the radial wavefunctions satisfying the boundary condition ϕnνl(0) = 0. Interestingly, due to the conservation of total angular momentum-encompassing internal states, microwave polarizations, and orbital motion-the quantum numbers mν of orbital angular momenta in different dressed-state channels ν = 2 ~ 9 are constrained by the condition mν + Mν = m0 + 2, where m1 = m0 represents the orbital angular momentum in the dressed-state channel \(\left\vert \nu=1\right\rangle\) of the Floquet sector n = 0. Explicitly, we obtain the following values for mν=2~9: m0 + 2, m0, m0 + 1, m0 + 2, m0 + 3, m0, m0 + 1, and m0 + 2, respectively, all determined by the single good quantum number m0. When two molecules absorb n σ+-polarized microwave photons and emit n π-polarized microwave photons, n quanta of microwave polarizations are transferred to the relative orbital motion. Consequently, the spherical harmonic \({Y}_{l,{m}_{\nu }+n}\) in Eq. (34) carries the index mν + n in the n-th Floquet channel. More importantly, since the sectors of \({\{{m}_{\nu }\}}_{\nu=1}^{9}\) labeled by different values of m0 are decoupled, we can drop the summation over mν in Eq. (34) and treat each sector with a fixed m0 separately. This observation significantly simplifies the numerical calculations.

For convenience, we introduce the column vector Φ(r) formed by the elements ϕnνl(r). The Schrödinger equation for the radial wavefunction can then be written as

where the matrix W is defined by the elements

with \({k}_{n\nu }={\left[M\left(\varepsilon -{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\nu \nu }^{(\infty )}+n\omega \right)\right]}^{1/2}\) being the incident momentum with respect to the νth interaction channel of the nth Floquet sector and

being the interaction matrix elements that can be evaluated analytically.

To solve the multi-channel scattering problem, we numerically evolve Eq. (35) from r = 0 to a sufficiently large value r∞ using Johnson’s log-derivative propagator method. We remark that to account for the short-range effects in scatterings, we also include, in numerical calculations, the universal van der Waals interaction through the replacement \({{{{\mathcal{V}}}}}_{0}({{{\bf{r}}}})\to {{{{\mathcal{V}}}}}_{0}({{{\bf{r}}}})-{C}_{{{{\rm{vdW}}}}}/{r}^{6}\), where CvdW is the strength of the universal van der Waals interaction55. Since CvdW is generally much smaller than the microwave shielding strength C656, the CvdW term only takes effect at short distances. Then, to obtain the scattering matrix, we compare ϕnνl(r∞) with the asymptotic boundary condition

where \({\hat{j}}_{l}(z)\) and \({\hat{n}}_{l}(z)\) are the Riccati-Bessel functions, and \({K}_{n\nu l,{n}_{0}{\nu }_{0}{l}_{0}}^{({m}_{0})}\) are elements of the K matrix, corresponding to the scattering from the incident channel (n0ν0l0) to the outgoing channel (nνl). Here, both channels are characterized by the same projection quantum number m0. Moreover, \({k}_{{n}_{0}{\nu }_{0}}\) and knν are the relative momenta for the incident and outgoing channels, respectively. In numerical calculations, we introduce a truncation ncut for the Floquet Hamiltonian such that ∣n∣≤ncut. Practically, it is found that for control parameters covered in this work, the scattering solutions converge when ncut = 5.

To proceed further, we denote the K matrix by \({{{{\bf{K}}}}}^{({m}_{0})}\), from which the scattering matrix \({{{{\bf{S}}}}}^{({m}_{0})}=(1+i{{{{\bf{K}}}}}^{({m}_{0})}){(1-i{{{{\bf{K}}}}}^{({m}_{0})})}^{-1}\) can be obtained. Now, the total elastic cross section for the incident channel (n0ν0) is

where \({S}_{n\nu l,{n}_{0}{\nu }_{0}{l}_{0}}^{({m}_{0})}\) are the elements of the scattering matrix and l and l0 are even (odd) for bosons (fermions). For elastic scattering, the outgoing channel of the molecules is the same as the incident channel (n0ν0) and the total kinetic energy of the molecules is thus conserved. Next, the total inelastic cross section can be calculated by subtracting the total elastic cross section from the total cross section, i.e.,

It is instructive to distinguish, depending on whether the total energy of the colliding molecules is conserved, the degenerate and nondegenerate inelastic scatterings, which are disguised in Eq. (40). Specifically, for degenerate inelastic scatterings, the outgoing molecules remain in the same Floquet sector n0 but transit to the lower dressed-state channel ν ( > ν0). Thus, the total energy of the colliding molecules is conserved. However, for nondegenerate inelastic scatterings, the outgoing molecules transit to a distinct Floquet sector n ( ≠ n0) by absorbing or emitting microwave photons and thus the total energy of the colliding molecules is not conserved. These energy-exchange processes mediated by the absorption and emission of dual microwaves lead to inelastic scattering and heating. The above analyses clearly indicate that the correct results for scatterings can only be obtained within the framework of the Floquet theory.

The experimentally more relevant quantities are the elastic and inelastic scattering rates, i.e., \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{el}}}})}={v}_{01}{\sigma }_{01}^{({{{\rm{el}}}})}\) and \({\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{inel}}}})}={v}_{01}{\sigma }_{01}^{({{{\rm{inel}}}})}\), where v01 = 2k01/M is the relative velocity. In addition, the ratio of the elastic to inelastic scattering rates, \(\gamma={\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{el}}}})}/{\beta }_{01}^{({{{\rm{inel}}}})}\) (the so-called good-to-bad collision ratio), is of particular importance for characterizing the efficiency of evaporative cooling. Finally, from the K matrix, we may compute for small k01 the scattering length matrix according to \({{{{\bf{a}}}}}^{({m}_{0})}=-\!\!{{{{\bf{K}}}}}^{({m}_{0})}/{k}_{01}\), whose element \({a}_{n\nu l,{n}_{0}{\nu }_{0}{l}_{0}}^{({m}_{0})}\) is the scattering length from the incident channel (n0ν0l0m0) to the outgoing channel (nνlm0). In particular, the s-wave scattering length for MSPMs is \({a}_{010,010}^{(0)}\).

Single-channel scatterings via effective potential

Armed with the effective potential, we may investigate the scattering properties between two MSPMs via single-channel scattering calculations. Here, the single-channel model for the relative motion of two MSPMs is governed by the Hamiltonian

Now, for the scatterings of two MSPMs, we solve the Schrödinger equation

where k01 is the incident momentum. Using the partial-wave expansion, \(\psi ({{{\bf{r}}}})={\sum }_{lm}{r}^{-1}{\phi }_{lm}(r){Y}_{lm}(\hat{{{{\bf{r}}}}})\), the radial wave functions satisfy

where the interaction matrix elements

are independent of the magnetic quantum number m. In analogy to the multichannel case, we numerically solve Eq. (43) with the effective potential (44), and compute the low-energy scattering length \({a}_{l,{l}_{0}}^{({m}_{0})}\) for the scattering from incident channel (l0m0) to outgoing channel (lm0). In particular, we focus on the s-wave scattering length \({a}_{0,0}^{(0)}\).

Variational approach for the many-body problem

We employ the variational approach to study the many-body properties of the gas. For this purpose, we first write the many-body Hamiltonian for a gas of N molecules:

where \(\hat{\psi }({{{\bf{r}}}})\) is the field operator. Unlike atomic condensates, strong many-body correlations may develop in ultracold molecular gases due to the large shielding core of inter-molecular potential. To incorporate the many-body correlation, we adopt the variational ansatz for the N-particle state44,57

where ϕ0(r) is the normalized single-particle wavefunction and J(ri, rj) [ = J(rj, ri)] is the Jastrow correlation factor. Both ϕ0(r) and J(ri, rj) are the variational parameters which can be determined by minimizing the total energy \(E[{\phi }_{0},J]=\left\langle {\Psi }_{N}\right\vert \hat{H}\left\vert {\Psi }_{N}\right\rangle\) calculated by the cluster expansion44,58. In numerical calculations, it is more convenient to replace ϕ0(r) by \(\sqrt{n({{{\bf{r}}}})}\) as the variational parameter, where \(n({{{\bf{r}}}})=\left\langle {\Psi }_{N}\right\vert {\hat{\psi }}^{{{\dagger}} }({{{\bf{r}}}})\hat{\psi }({{{\bf{r}}}})\left\vert {\Psi }_{N}\right\rangle\) is the total density.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All relevant data supporting this study are contained in the main manuscript and supplementary materials. Source data for Figs. 2-7 and Supplementary Fig. 1 are deposited in the Figshare database under accession code https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.3012168159.

Code availability

All numerical codes in this paper are available upon request to the authors.

References

Flambaum, V. V. & Kozlov, M. G. Enhanced sensitivity to the time variation of the fine-structure constant and mp/me in diatomic molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 150801 (2007).

Isaev, T. A., Hoekstra, S. & Berger, R. Laser-cooled RaF as a promising candidate to measure molecular parity violation. Phys. Rev. A 82, 052521 (2010).

Hudson, J. J. et al. Improved measurement of the shape of the electron. Nature 473, 493–496 (2011).

Collaboration, T. A. et al. Order of magnitude smaller limit on the electric dipole moment of the electron. Science 343, 269–272 (2014).

Andreev, V. et al. Improved limit on the electric dipole moment of the electron. Nature 562, 355–360 (2018).

Hutzler, N. R. Polyatomic molecules as quantum sensors for fundamental physics. Quantum Sci. Technol. 5, 044011 (2020).

Krems, R. V. Cold controlled chemistry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 4079–4092 (2008).

Hu, M.-G. et al. Direct observation of bimolecular reactions of ultracold KRb molecules. Science 366, 1111–1115 (2019).

Liu, Y. & Ni, K.-K. Bimolecular chemistry in the ultracold regime. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 73, 73–96 (2022).

DeMille, D. Quantum computation with trapped polar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 067901 (2002).

Sawant, R. et al. Ultracold polar molecules as qudits. N. J. Phys. 22, 013027 (2020).

Rabl, P. et al. Hybrid quantum processors: molecular ensembles as quantum memory for solid state circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 033003 (2006).

Tesch, C. M. & de Vivie-Riedle, R. Quantum computation with vibrationally excited molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 157901 (2002).

Wall, M. L., Maeda, K. & Carr, L. D. Realizing unconventional quantum magnetism with symmetric top molecules. N. J. Phys. 17, 025001 (2015).

Albert, V. V., Covey, J. P. & Preskill, J. Robust encoding of a qubit in a molecule. Phys. Rev. X 10, 031050 (2020).

Micheli, A., Brennen, G. K. & Zoller, P. A toolbox for lattice-spin models with polar molecules. Nat. Phys. 2, 341–347 (2006).

Altman, E. et al. Quantum simulators: architectures and opportunities. PRX Quantum 2, 017003 (2021).

Lahaye, T., Menotti, C., Santos, L., Lewenstein, M. & Pfau, T. The physics of dipolar bosonic quantum gases. Rep. Prog. Phys. 72, 126401 (2009).

Karman, T. & Hutson, J. M. Microwave shielding of ultracold polar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 163401 (2018).

Lassablière, L. & Quéméner, G. Controlling the scattering length of ultracold dipolar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 163402 (2018).

Marco, L. D. et al. A degenerate fermi gas of polar molecules. Science 363, 853–856 (2019).

Duda, M. et al. Transition from a polaronic condensate to a degenerate Fermi gas of heteronuclear molecules. Nat. Phys. 19, 720–725 (2023).

Anderegg, L. et al. Observation of microwave shielding of ultracold molecules. Science 373, 779–782 (2021).

Lin, J. et al. Microwave shielding of Bosonic NaRb molecules. Phys. Rev. X 13, 031032 (2023).

Bigagli, N. et al. Collisionally stable gas of bosonic dipolar ground state molecules. Nat. Phys. 19, 1579–1584 (2023).

Schindewolf, A. et al. Evaporation of microwave-shielded polar molecules to quantum degeneracy. Nature 607, 677–681 (2022).

Chen, X.-Y. et al. Field-linked resonances of polar molecules. Nature 614, 59–63 (2022).

Bigagli, N. et al. Observation of Bose-Einstein condensation of dipolar molecules. Nature 631, 289–293 (2024).

Chen, X.-Y. et al. Ultracold field-linked tetratomic molecules. Nature 626, 283–287 (2024).

Deng, F. et al. Formation and dissociation of field-linked tetramers https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.13645. 2405.13645 (2024).

You, L. & Marinescu, M. Prospects for p-wave paired Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer states of fermionic atoms. Phys. Rev. A 60, 2324–2329 (1999).

Baranov, M. A., Mar’enko, M. S., Rychkov, V. S. & Shlyapnikov, G. V. Superfluid pairing in a polarized dipolar Fermi Gas. Phys. Rev. A 66, 013606 (2002).

Shi, T., Zhang, J.-N., Sun, C.-P. & Yi, S. Singlet and Triplet Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer pairs in a gas of two-species fermionic polar molecules. Phys. Rev. A 82, 033623 (2010).

Zhao, C. et al. Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov theory of dipolar Fermi Gases. Phys. Rev. A 81, 063642 (2010).

Wu, C. & Hirsch, J. E. Mixed triplet and singlet pairing in ultracold multicomponent fermion systems with dipolar interactions. Phys. Rev. B 81, 020508 (2010).

Levinsen, J., Cooper, N. R. & Shlyapnikov, G. V. Topological px + ipy superfluid phase of fermionic polar molecules. Phys. Rev. A 84, 013603 (2011).

Baranov, M. A., Dalmonte, M., Pupillo, G. & Zoller, P. Condensed matter theory of dipolar quantum gases. Chem. Rev. 112, 5012–5061 (2012).

Shi, T., Zou, S.-H., Hu, H., Sun, C.-P. & Yi, S. Ultracold Fermi gases with resonant dipole-dipole interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 045301 (2013).

Qi, R., Shi, Z.-Y. & Zhai, H. Fermion pairing across a dipolar interaction induced resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 045302 (2013).

Deng, F. et al. Effective potential and superfluidity of microwave-shielded polar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 183001 (2023).

Read, N. & Green, D. Paired states of fermions in two dimensions with breaking of parity and time-reversal symmetries and the fractional Quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 61, 10267–10297 (2000).

Ivanov, D. A. Non-Abelian statistics of half-quantum vortices in p-Wave superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 268–271 (2001).

Stevenson, I. et al. Three-body recombination of ultracold microwave-shielded polar molecules https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.04901. 2407.04901 (2024).

Jin, W.-J., Deng, F., Yi, S. & Shi, T. Bose-Einstein condensates of microwave-shielded polar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 233003 (2025).

Langen, T. et al. Dipolar droplets of strongly interacting molecules https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.09391 (2024).

Karman, T. et al. Double microwave shielding. PRX Quantum 6, 020358 (2025).

Xu, B., Yang, F., Qi, R., Zhai, H. & Zhang, P. Synthetic mutual gauge field in microwave-shielded polar molecular gases https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.10806 (2024).

Yi, S. & You, L. Trapped atomic condensates with anisotropic interactions. Phys. Rev. A 61, 041604 (2000).

Santos, L., Shlyapnikov, G. V., Zoller, P. & Lewenstein, M. Bose-Einstein condensation in trapped dipolar gases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 1791–1794 (2000).

Yi, S. & You, L. Trapped condensates of atoms with dipole interactions. Phys. Rev. A 63, 053607 (2001).

Cornell, E. A. & Wieman, C. E. Nobel lecture: Bose-Einstein condensation in a dilute gas, the first 70 years and some recent experiments. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 875–893 (2002).

Pethick, C. J. & Smith, H. i-iv (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

de Boer, J. & Michels, A. Contribution to the quantum-mechanical theory of the equation of state and the law of corresponding states. determination of the law of force of helium. Physica 5, 945–957 (1938).

de Boer, J. & Michels, A. The influence of the interaction of more than two molecules on the molecular distribution-function in compressed gases. Physica 6, 97–114 (1939).

Idziaszek, Z. & Julienne, P. S. Universal rate constants for reactive collisions of ultracold molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 113202 (2010).

Lepers, M., Vexiau, R., Aymar, M., Bouloufa-Maafa, N. & Dulieu, O. Long-range interactions between polar alkali-metal diatoms in external electric fields. Phys. Rev. A 88, 032709 (2013).

Shi, T., Demler, E. & Ignacio Cirac, J. Variational study of fermionic and Bosonic systems with Non-Gaussian States: theory and applications. Ann. Phys. 390, 245–302 (2018).

Aviles, J. B. Extension of the Hartree method to strongly interacting systems. Ann. Phys. 5, 251–281 (1958).

Deng, F., Hu, X., Jin, W.-J., Yi, S. & Shi, T. Data for “Two- and Many-Body Physics of Ultracold Molecules Dressed by Dual Microwave Fields”. Figshare, 30121681 https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30121681 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFA0718304), by NSFC (Grants No. 12135018 and No. 12274331), and by CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (Grant No. YSBR-057).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S. and S.Y. initiated this work. T.S., F.D., and X.H. derived the effective potential. F.D. and X.H. performed the scattering calculations. T.S. and W.J. performed the many-body calculations. T.S. and S.Y. analyzed the data, conducted theoretical analysis, and prepared the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, F., Hu, X., Jin, WJ. et al. Two- and many-body physics of ultracold molecules dressed by dual microwave fields. Nat Commun 16, 11219 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66067-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66067-2