Abstract

Excitons in Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (TMDs) acquire a spin-like quantum number, a pseudospin, originating from the crystal’s discrete rotational symmetry. Here, we break this symmetry using a tunable uniaxial strain, effectively generating a pseudomagnetic field acting on exciton valley degree of freedom. Under this field, we demonstrate pseudospin analogs of spintronic phenomena such as the Zeeman effect and Larmor precession and determine fundamental timescales for pseudospin dynamics in TMDs. Finally, we uncover the bosonic – as opposed to fermionic – nature of many-body excitonic species using the pseudomagnetic equivalent of the g-factor spectroscopy. Our work is the first step toward establishing this spectroscopy as a universal method for probing correlated many-body states and realizing pseudospin analogs of spintronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Counterparts of magnetic phenomena arise in non-magnetic systems with two degenerate yet distinct states. A quantum number associated with this degeneracy can be treated as a spin analog, or “pseudospin”, while the external perturbation lifting the degeneracy acts as a “pseudomagnetic field”1,2,3,4. Pseudomagnetic fields in systems ranging from photonic crystals5,6 to inhomogeneously strained graphene7,8 have been used to study topological phenomena, flat-band physics, and unconventional superconductivity9,10,11,12,13,14. In all these cases, the language of pseudomagnetic fields offers intuitive parallels to familiar magnetic phenomena, but applied to degrees of freedom that may remain unaffected by real magnetic fields.

One particularly appealing system for exploring pseudomagnetic phenomena is monolayers of Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (TMDs)15,16,17. There, a broken inversion symmetry gives rise to two energy-degenerate valleys at the K and K’ points of the Brillouin zone that host tightly bound excitons (Fig. 1a). The pseudospin associated with this degeneracy can be initialized and read out optically: σ+ (σ−)-polarized light couples to excitons at the K (K’) valleys (pseudospin up and down, respectively), whereas linear polarization couples to a coherent superposition of K and K’ excitons, corresponding to an in-plane pseudospin2,15,16,17,18. The optical Stark effect has been used to lift the K/K’ valley degeneracy, effectively acting as a pseudomagnetic field19,20. Nevertheless, the high intensity of light pulses required to lift the degeneracy makes it challenging to study low-energy excitonic phenomena. In contrast, theory suggests that uniaxial mechanical strain produces a continuous, tunable in-plane pseudomagnetic field splitting states with dipole moments parallel (\({{\mathrm{X}}}_{b}^{0}\)) and orthogonal (\({{\mathrm{X}}}_{b}^{0}\)) to the strain axis (Fig. 1b)1,2,17. In this field, valley pseudospin is expected to exhibit analogs of magnetic Zeeman and Larmor effects. This raises a natural question: must pseudomagnetic phenomena always mirror those of real magnetic fields?

a Different superpositions of excitons in K and K' valleys are excited by light with distinct polarizations. Circularly polarized light, σ+ or σ−, couples to K or K' excitons, respectively (red and blue arrows), whereas linearly polarized light (purple and orange arrows) generates superpositions of these excitons. b Uniaxial strain ε produces an in-plane pseudomagnetic field Ω(ε) that lifts the degeneracy of neutral excitons with dipole moments parallel and orthogonal to the straining axis. Under the same field, trions remain locked by time-reversal symmetry, while Fermi polarons split in energy, enabling pseudomagnetic g-factor spectroscopy. c Bloch sphere representation of pseudospin. Each coherent superposition of K and K' excitons corresponds to a pseudospin vector S on the Bloch sphere. The σ+ or σ− circularly polarized light couples to the states at the poles, while linearly polarized light excites the states in the equatorial plane. In the presence of uniaxial strain, S undergoes damped Larmor-like precession around the strain-induced pseudomagnetic field Ω. d Straining technique: an applied gate voltage (VG) induces tensile strain ε (pink arrows) in suspended MoSe2 or WSe2 monolayer (blue) via electrostatic force. e Optical image of a suspended MoSe2 monolayer. f COMSOL simulation of strain uniaxiality U in a typical device.

Unlike the conventional magnetic field, the strain-induced pseudomagnetic field preserves time-reversal symmetry and therefore affects only bosonic quasiparticles21,22. In contrast, the degeneracy of a fermionic Kramers pair cannot be lifted by a time-reversal-invariant perturbation. For example, neutral excitons (X0), composite bosons formed by bound electron-hole pairs, are expected to split in a pseudomagnetic field (Fig. 1b). An intriguing situation occurs in doped TMDs when novel quasiparticles, charged excitons (X+/−), arise. These quasiparticles can be described in two alternative ways, leading to different responses to the field (Fig. 1b). In the trion picture, they are fermionic three-particle states composed of a neutral exciton bound to a hole (electron)15,23,24. Such a state is Kramers protected and can only exhibit splitting in a real magnetic field. In the second “Fermi-polaron” (FP) or Suris tetron picture, a charged exciton is a neutral exciton correlated with the electron-hole pair inside the Fermi sea24,25,26,27,28,29. This state is a composite boson that can be split by a pseudomagnetic field21,22. Despite their different statistics, no measurement so far could conclusively distinguish between the Fermi-polaron and trion pictures.

Here, we resolve the debate about the nature of charged excitons using pseudomagnetic g-factor spectroscopy. To accomplish this, we introduce a method to generate a strong tunable strain-induced pseudomagnetic field in suspended monolayer TMDs at cryogenic temperatures. We take advantage of the time-independent nature, low disorder, and high magnitude of strain in TMDs to explore the effect of a pseudomagnetic field on various excitonic species. We first employ the pseudospin analogs of the Zeeman and Larmor effects to establish the strength of the pseudomagnetic field and obtain previously unattainable material parameters. We then determine the symmetry of many-body excitonic states by measuring their pseudomagnetic g-factors. Our measurements show that both neutral and charged excitons can only be described as bosonic quasiparticles.

Results

Pseudospin in strained TMDs

The spatial symmetry of TMDs dictates that a linearly polarized photon in a state \(\alpha \left\vert {\sigma }^{+}\right\rangle+\beta \left\vert {\sigma }^{-}\right\rangle\), with ∣α∣2 = ∣β∣2 = 1/2, creates a coherent superposition of bright excitons with wavefunctions residing in K and K’ valleys, \(\Psi=\alpha \left\vert {X}_{{{{\rm{K}}}}}\right\rangle+\beta \left\vert {X}_{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}^{{\prime} }}\right\rangle\). The spinor χ = (α, β) then determines the pseudospin S in a similar way as the electron spin is defined in quantum mechanics: \({{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}=\left(\,{\mbox{Re}}\,(\alpha {\beta }^{*}),\,\,{\mbox{Im}}\,({\alpha }^{*}\beta ),\,| \alpha {| }^{2}-| \beta {| }^{2}\right)\). The application of mechanical strain breaks the underlying symmetries of TMDs, thereby affecting the pseudospin degree of freedom, see Supplementary Note S11,2. The effect of strain on the exciton’s pseudospin in the limit of zero exciton momentum is described by the following Hamiltonian:

where εxx, εyy, εxy = εyx are the components of the strain tensor, and A, B are material-specific parameters. The diagonal terms describe the well-known energy shift of the excitons under biaxial strain at a rate A ≈ − 100 meV/%30,31,32. It is evident that K and K’ excitons, related by time-reversal symmetry, always remain energetically degenerate. However, the off-diagonal terms suggest that an application of uniaxial (εxx ≠ εyy) or shear (εxy ≠ 0) strain mixes excitons in K and K’ valleys. This effect becomes apparent if we rearrange the Hamiltonian in the form \(H={H}_{0}+\frac{\hslash }{2}\left({{{{\mathbf{\Omega }}}}}\cdot {{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}\right),\) where \({H}_{0}=A\left({\varepsilon }_{xx}+{\varepsilon }_{yy}\right){\sigma }_{0}/2\) is the diagonal part of Eq. (1), Ω = (B/ℏ)(εxx − εyy, 2εxy, 0), σ0 is the identity matrix, and σ = (σx, σy, σz) is the vector of Pauli matrices acting in the pseudospin basis. This Hamiltonian is formally equivalent to that of a spin in a magnetic field, with the vector Ω playing the role of the pseudomagnetic field. We therefore expect the presence of analogs of magnetic phenomena in strained devices.

Generation of pseudomagnetic field and detection of a pseudospin

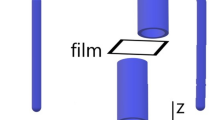

We induce a strong pseudomagnetic field at cryogenic temperatures using a technique based on tensioning of a suspended monolayer with electrostatic force (Fig. 1d) that we recently developed30. Our approach overcomes the limitations of previous methods that function only at elevated temperatures, leaving pseudomagnetic phenomena largely unexplored33,34. Moreover, our clean samples ensure a long lifetime and low decoherence rate of excitons. We focus on two materials representative of the TMDs family: monolayer MoSe2, chosen for its well-understood and rather simple excitonic spectrum35, and WSe2, selected for its long coherence time of excitons comparable to their lifetime36,37,38,39.

Our device consists of a TMD monolayer suspended over a trench in an Au/SiO2/Si stack (Fig. 1d, e). A gate voltage, VG, applied between the Si substrate and the sample induces an electrostatic pressure and strains the TMD, with the strain distribution defined by the trench geometry (see Note S2 for the calibration of applied strain). For an elliptical trench with major axis a and minor axis b (a ≫ b), a predominantly uniaxial strain is induced along b, which we quantify via the degree of uniaxiality, U = (εbb − εaa)/(εbb + εaa). Specifically, we use an ellipse with a = 8 μm and b = 3 μm, which ensures high uniaxiality U ≈ 80% (Fig. 1f), while maintaining strain uniformity \(\frac{\Delta \varepsilon }{\varepsilon } < 10\%\) within the laser spot of ~1 μm (Fig. S1a–c). Conversely, a device with a circular trench experiences uniform biaxial strain (U ≈ 0) in the center of the membrane (Supplementary Fig. S1e–g).

In a prototypical experiment, the uniaxial strain generates a pseudomagnetic field, Ω, along the x-axis in pseudospin space (Fig. 1c). In analogy to the Zeeman effect, we expect the exciton energy to depend on the orientation of its pseudospin S with respect to Ω, being minimal when the two vectors are aligned. To study this effect, we use the fact that the pseudospin orientation on the Bloch sphere determines the polarization of a photon coupled to this pseudospin. Specifically, we access the energy of the states with pseudospin along the equator of the Bloch sphere by recording the linear polarization-resolved photoluminescence (PL) spectra.

In analogy to the Larmor effect, the pseudospin along the y-axis in pseudospin space — that is, excited by light polarized along a direction at 45° with respect to the strain axis — undergoes damped precession around Ω (red cloud in Fig. 1c). Such precession is signaled by the appearance of the pseudospin component Sz, while the damped nature of the precession leads to the development of a pseudospin component aligned with the field, S∥. We experimentally determine the components of pseudospin from polarization-resolved PL spectra as \({S}_{z}=\frac{I({\sigma }^{+})-I({\sigma }^{-})}{I({\sigma }^{+})+I({\sigma }^{-})}\) and \({S}_{\parallel }=\frac{I(a)-I(b)}{I(a)+I(b)}\), where I(σ+) and I(σ−) are the intensities of σ+ or σ− polarized light; I(a) and I(b) are intensities polarized along and perpendicular to the strain axis, respectively40.

We begin by studying an analog of the Zeeman effect to characterize the achievable field strength. Subsequently, we investigate the Larmor effect in this field. The characteristic time scales extracted from these measurements provide insights into the mechanisms of pseudospin polarization loss and strategies to suppress it. We finally develop a counterpart of g-factor measurements to uncover the nature of many-body states.

Zeeman splitting in pseudomagnetic field

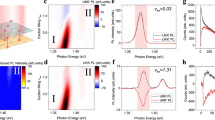

Figure 2 a shows the polarization-resolved PL spectra of X0 emission energy in an unstrained MoSe2 (“Methods”). The orange and purple spectra, corresponding to the polarization along the major (a) and minor (b) axes, respectively, show the expected nearly identical emission energy, Ea = Eb. However, a relative energy shift emerges when uniaxial strain is applied (ε = εbb − εaa = 0.4%; Fig. 2b). Indeed, a false-color map of the polarization-resolved PL spectra of the strained sample (left panel in Fig. 2c) reveals a clear sinusoidal dependence of the X0 emission energy on the detection polarization direction. The minimum and maximum of the X0 emission energy correspond to S oriented along and opposite to Ω, respectively (see schematic in Fig. 2c). This strain-induced energy splitting between the two orthogonal polarization directions is, in fact, analogous to the Zeeman effect for pseudospins; hence, we term it pseudo-Zeeman splitting.

a, b Polarization-resolved PL spectra at near-zero strain (top panel) and under 0.4% uniaxial strain (bottom panel) in the region of neutral exciton X0 in MoSe2. The emission energy of X0 becomes polarization-dependent under strain, with higher energy along the direction of uniaxial strain b (purple) than orthogonal to it (orange). Polarizations of both excitation and detection are linear and co-polarized. c Normalized PL spectra for the same device as a function of the analyzer angle at 0.4% strain, along with the simulations (circles mark the extracted peak position). Note, that the angle φ between the probed pseudospin S and Ω is twice the angle between the polarizer (analyzer) axis and the strain direction b (side panel). d The energy splitting between the excitons with pseudospin aligned along or opposite to the pseudomagnetic field, interpreted as pseudo-Zeeman splitting, extracted from (c). The shaded area represents the uncertainty.

To quantify the established pseudo-Zeeman effect, we fit the data in Fig. 2c using \(E(\varphi )={E}_{0}+(\hslash \Omega /2)\cos \varphi\), where the term E0 = A(εxx + εyy)/2 describes the strain-induced redshift in X0 energy compared to the unstrained state (see Eq. 1) and φ is the angle between the exciton pseudospin and pseudomagnetic field. The extracted pseudomagnetic field grows linearly at small strain level (< 0.4%) at a rate of B = 24.6 ± 2.5 T/% in MoSe2 (solid line in Fig. 2d) and 16.1 ± 1.8 T/% in WSe2 (Supplementary Fig. S2) corresponding to 2.9 ± 0.3 meV and 1.9 ± 0.2 meV, respectively. Following an established convention7,41,42, we used the free-electron gyromagnetic g-factor g = 2 (corresponding to 2μB = 0.116 meV/T, with μB being the Bohr magneton) to convert the measured splitting into an equivalent pseudomagnetic field in Tesla solely for easier comparison with conventional magnetic effects. To emphasize the difference between pseudomagnetic and real magnetic fields, we also provide the exciton splitting corresponding to the field in units of energy, whenever appropriate. At higher strain level, the apparent dependence of exciton splitting becomes sublinear (Supplementary Fig. S3), which we attribute to a reduced intensity of the higher energy pseudo-Zeeman-split state when the energy separation exceeds the thermal energy (kBT ≈ 1 meV). The model based on this mechanism closely aligns with the observed behavior of X0 (simulation in Fig. 2c, Supplementary Note S7) and the extracted splitting (dotted line in Fig. 2d). In addition, the splitting is close to the expected value in the optical reflectivity measurements (Supplementary Fig. S4). Therefore, in the following, we assume a linear dependence of Ω on strain, with Ω reaching 43 ± 6 T (5.0 ± 0.7 meV) in MoSe2 at our highest applied strain of 1.6% (Fig. S3). Finally, we note that the pseudo-Zeeman effect is absent in biaxially strained devices (Ω = 0), an experimental situation realized in circular trenches (Supplementary Fig. S5). This finding further confirms that the observed behavior in Fig. 2 results from the pseudospin Zeeman effect and rules out artifacts related to, e.g., spurious plasmonic effects, biaxial strain, etc.

Strain control of pseudospin dynamics

Our next objective is to gain control over pseudospin dynamics; to this end, we explore the pseudospin analog of Larmor precession and quantify the characteristic pseudospin relaxation times. A hallmark of Larmor precession is the emergence of circularly polarized PL emission under linearly polarized excitation (Fig. 3a). Figure 3b shows circular polarization-resolved PL spectra of WSe2 at Ω = 8 T (0.9 meV) corresponding to ε = 0.5%. Under the strain-induced pseudomagnetic field, a prominent asymmetry between the I(σ+) and I(σ−) intensities at the X0 emission energy (red and blue, respectively) emerges, whose sign depends on the excitation polarization direction (Supplementary Figs. S6 and S7). This observation is striking, as a circularly polarized emission under linear excitation can only be caused by the breaking of either time-reversal or spatial symmetries. Since the magnetic field is absent in our experiments and the asymmetry is detected only when a pseudomagnetic field is induced (Supplementary Fig. S8), we conclude that the pseudomagnetic field alone is responsible for the observed Larmor-like effect.

a Schematics of the expected Larmor-like dynamics of pseudospin in a pseudomagnetic field. b Circular-polarization-resolved PL spectra of WSe2 under 8 T (0.9 meV) pseudomagnetic field, excited by linearly polarized light. The rotation of the exciton’s pseudospin is manifested as an asymmetry between σ− and σ+ emission of the neutral exciton (X0). c The \({S}_{z}^{*}\) component of the pseudospin vs. the pseudomagnetic field strength in WSe2 (red points) and fit to the model Eq. (2) (red line), top and bottom x-axes are the pseudomagnetic field strength and the corresponding excitonic splitting, respectively. The shadow represents uncertainty. d The component of the pseudospin along the field, S∥, vs. field strength in MoSe2 and WSe2 and fit to our theoretical model Eq. (2). Inset: the dependence of T∥ on the pseudomagnetic field strength in MoSe2 and WSe2 (dark and bright orange lines, respectively).

To gain insight into the mechanism of pseudospin dynamics and relaxation, we develop a theory of pseudo-Larmor precession. The full model is provided in Supplementary Note S1, we illustrate the concept here with an example based on the Bloch equation for population-averaged pseudospin dynamics

where G is the pseudospin generation rate defined by the excitation intensity and polarization, S0 describes the quasi-equilibrium (thermal) pseudospin induced by the pseudomagnetic field (Fig. 3a). The characteristic times are: exciton lifetime (τ ≈ 2 ps)37,38,43,44,45,46,47,48, period of Larmor precession (T⊥ = 2π/Ω), Tcoh is the coherence time that determines relaxation of the pseudospin components transverse to the field, and T∥ characterizes the time over which thermal equilibrium between the split sublevels is established (for the relation of Eq. (2) to the microscopic model, see Supplementary Notes S1, S3, and S4). The microscopic model accounts for the exciton longitudinal-transverse splitting caused by the electron-hole exchange interaction. This splitting induces an effective wavevector-dependent pseudomagnetic field ΩLT, which is present even in an unstrained monolayer and leads to the loss of pseudospin coherence by the Dyakonov-Perel mechanism18,49. A strain-induced pseudomagnetic field suppresses ΩLT-induced depolarization, which significantly increases both Tcoh and T∥ (Supplementary Note S3). Our goal is to experimentally determine these two timescales that define pseudospin dynamics yet remain unknown.

In a simple case of unitary excitation along the y pseudospin axis, Gτ⊥ = (0, 1, 0), the steady-state solution of Eq. (2) is \({S}_{z}={\tau }_{\perp }\Omega /\left[1+{\left({\tau }_{\perp }\Omega \right)}^{2}\right]\), where 1/τ⊥ = 1/Tcoh + 1/τ, note that Ω in this equation has units of rad/s (Supplementary Note S1). Intuitively, ensemble averaged Sz probed by PL grows linearly with Ω when the average rotation angle for pseudospins during their lifetime is small, τ⊥Ω ≪ 1. At higher field strengths, the pseudospin undergoes multiple rotations around the Bloch sphere during the exciton lifetime, reducing the average pseudospin polarization similar to the Hanle effect in real magnetic fields. To experimentally realize the scenario of unitary excitation, we consider the reduced pseudospin \({S}_{z}^{*}(\Omega )\), normalized to the measured generation rate at the corresponding field G(Ω) (Supplementary Note S3).

Figure 3c shows the experimentally obtained dependence of \({S}_{z}^*\) on the pseudomagnetic field in WSe2, along with a fit using the solution of Eq. (2). This fit yields Tcoh = τ⊥τ/(τ − τ⊥) = 1.0 ± 0.2 ps in the regime of high field strength, which is longer than the coherence time measured in the unstrained samples (Tcoh ~ 0.5 ps37,38) due to the influence of the pseudomagnetic field (Supplementary Note S3). Finally, the large pseudospin polarization, \({S}_{z}^{*}=50\%\), demonstrates the strong potential of the pseudomagnetic field for manipulating the exciton pseudospin.

To determine T∥, we examine Eq. (2) under unpolarized excitation conditions, which are experimentally realized at high detuning of the excitation energy from the X0 resonance so that all induced polarization is lost. In this case, G → 0 and only field-induced S appears in the form \({S}_{\parallel }=\tau /(\tau+{T}_{\parallel })\times \tanh \left[\hslash \Omega /(2{k}_{B}T)\right]\) (Supplementary Note S1).

This expression suggests that the initially unpolarized pseudospins tend to align along Ω, acquiring a pseudospin polarization within a thermal distribution. The induced polarization saturates when the pseudo-Zeeman splitting exceeds the thermal energy (kBT ≈ 1 meV), with its maximum value determined by the ratio of the relaxation time T∥ to the lifetime τ.

The experimentally observed S∥vs.Ω (Fig. 3d) matches these expectations. At low field strengths (Ω < 10 T (1.2 meV)), we observe a linear increase in S∥. At higher fields, the polarization reaches the expected plateau, \({S}_{\parallel }\left(\hslash \Omega \gg {k}_{B}T\right)=\tau /(\tau+{T}_{\parallel })\). From the value of S∥ ≈ 20% at the plateau in both MoSe2 and WSe2, we find the pseudospin relaxation time T∥ ~ 10 ps (Supplementary Note S3), significantly longer than the exciton coherence Tcoh ~ 0.5 ps and lifetime τ ≈ 2 ps in these samples50,51. This slowdown of the relaxation time arises because the pseudomagnetic field suppresses pseudospin decay dominated by ΩLT (see Supplementary Note S3). Using a model that accounts for this effect (Supplementary Note S1), we fit S∥ and find that the relaxation time increases from 1 to 8 ps over the studied range of field strengths (inset in Fig. 3d). Furthermore, this analysis allows us to extract the field responsible for loss of pseudospin coherence, yielding the root-mean-square values \({\Omega }_{{{\mbox{WSe}}}_{2}}^{{\mbox{LT}}\,}=10.4\pm 1.3\) T (1.2 meV) in WSe2 and \({\Omega }_{{{\mbox{MoSe}}}_{2}}^{{\mbox{LT}}\,}=12.0\pm 1.1\) T (1.4 meV) in MoSe2 in reasonable agreement with the model predictions (Supplementary Note S4). To the best of our knowledge, this constitutes the first measurement of this fundamental parameter.

Many-body states under pseudomagnetic field

Our ultimate goal is to investigate complex many-body states beyond neutral excitons under the pseudomagnetic field and to showcase the unique capacity of our technique to reveal their intrinsic structure. Two critical aspects remain experimentally unexplored. First, recent theoretical studies have suggested that trions and FPs show contrasting behaviors under a pseudomagnetic field due to the distinct response to time-reversal symmetry21,22. That suggests a possibility of a g-factor-like measurement to distinguish the two descriptions of charged excitons. We define the pseudomagnetic g-factor (gp) as \(\Delta E=\frac{{g}_{p}}{2}\hslash \Omega\), where ΔE is pseudo-Zeeman splitting, with gp = 0 signifying a trion and gp ≠ 0 indicating a Fermi polaron nature of the charged exciton. Second, since the nature of trions and FPs are strongly affected by the density of charge carriers (Fig. 1b), the magnitude of gp is expected to depend on the Fermi energy (EF). Specifically, gp can be expressed as gp(EF) = 2ΔEFP(EF)/ΔEX, where ΔEX = ℏΩ, and \(\Delta {E}_{{{{\rm{FP}}}}}=\frac{{g}_{p}({E}_{F})}{2}\hslash \Omega\). In our devices, an applied gate voltage varies the Fermi energy together with strain, enabling measurement of the pseudomagnetic g-factor.

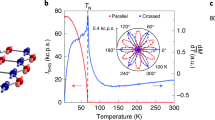

To test these predictions, we probed the response of charged excitons in MoSe2 and WSe2 under an applied pseudomagnetic field (Fig. 4a–c). We used the same experimental configuration and analysis as in the study of the pseudo-Zeeman effect of neutral excitons. Figure 4a shows the pseudomagnetic-field-induced energy splitting of the negatively charged excitons (X−) in doped MoSe2 (ne > 1 × 1012 cm−2) with pseudospins aligned along and opposite to the pseudomagnetic field. The observed finite energy splitting for X− is similar to what was seen previously for neutral excitons (Fig. 2d), although with a much lower magnitude (Fig. 4b). The observation of pseudo-Zeeman splitting of the X− state provides conclusive evidence of their Fermi polaron nature and establishes their bosonic statistics.

a False-color map of polarization-resolved PL of the charged exciton (X−) in monolayer MoSe2. Under a strain-induced pseudomagnetic field, a prominent pseudo Zeeman splitting appears. b Splitting of the negatively charged exciton as a function of pseudomagnetic field strength in doped MoSe2. The observed splitting is consistent with the polaronic character of the charged exciton. c Peak splitting of bright (X−) and dark (\({{{{\rm{X}}}}}_{d}^{+}\), \({{{{\rm{X}}}}}_{d}^{-}\)) charged excitons in WSe2 as a function of pseudomagnetic field strength. d The dependence of pseudospin g-factor gp of bright FP on Fermi energy in WSe2 (red points) and MoSe2 (blue points), alongside theoretical predictions21 (red and blue solid lines, respectively). The size of each point is proportional to strain, and color shades mark different experimental runs with different initial carrier densities.

In contrast to MoSe2, WSe2 hosts a plethora of additional many-body states (Supplementary Fig. S2), including positively and negatively charged bright excitons (X+ and X−), neutral and charged dark excitons (Xd, \({\,{\mbox{X}}\,}_{d}^{+}\), and \({\,{\mbox{X}}\,}_{d}^{-}\)), biexcitons (XX), and phonon replicas (Xp)52,53. We observe a considerable strain-dependent energy splitting of X−, \({\,{\mbox{X}}\,}_{d}^{+}\), and \({\,{\mbox{X}}\,}_{d}^{-}\) in that material (Fig. 4c), which confirms their Fermi polaronic nature. The dark species demonstrate lower splitting and an overall lower pseudomagnetic g-factor, \({g}_{p}({\,{\mbox{X}}\,}_{d}^{+/-})\approx 0.8\), compared to the bright ones, gp(X−) ≈ 2.0 for the same doping level. We note that the low intensity of biexcitons and phonon replicas prevents us from extracting their splitting, while X+ is only visible at low pseudomagnetic fields (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Finally, we use the pseudomagnetic g-factor to explore the effect of Fermi energy (charge density) on the character of charged excitons. The pseudomagnetic g-factor of FPs vs. Fermi energy is plotted in Fig. 4d; the size of each point is proportional to the uniaxial strain (see Supplementary Note S5 for Fermi energy estimation). We find that for low Fermi energy, gp is nearly zero despite a large pseudomagnetic field, which is consistent with the convergence of Fermi polaronic and trionic pictures in this regime. Meanwhile, at a larger EF, the splitting of the charged exciton approaches that of a neutral exciton. This behavior is expected, as the attractive Fermi polaron splitting inherits the neutral exciton splitting and saturates at this value. Indeed, theory predicts21 that the attractive polaron g-factor depends linearly on Fermi energy EF (Supplementary Note S6). Moreover, the predicted value of gp for charged excitons in WSe2 (red line in Fig. 4d) is higher than that in MoSe2 (blue line in Fig. 4d) for the same doping level, due to the mixing of the intervalley and intravalley states21. A close match between the experimental results and theoretical predictions further supports the tuning of FP character by induced charge density. Overall, our results establish the pseudo-Zeeman splitting as a tool to assess the symmetry and statistics of excitonic states.

Discussion

Our technique to study and manipulate pseudospin opens multiple new possibilities. First, the interplay between magnetic and pseudomagnetic fields in the same device is promising to reveal unique effects54. The presence of strongly coupled spin and valley pseudospin degrees of freedom with distinctive timescales should cause complex and hitherto unstudied dynamics. Second, our results indicate a rotation of the pseudospin during pseudo-Larmor precession. The pseudospin dynamics can be probed in the time domain by observing an oscillating signal in, e.g., time-resolved Kerr rotation microscopy51,55,56. Third, the coupling between the pseudospin and momentum can lead to the pseudomagnetic counterparts of spin-orbit phenomena such as the anomalous Hall, quantum spin Hall, and Rashba-like effects54,57,58,59,60. The complex nature of momentum/pseudospin coupling should significantly alter these effects compared to their classical counterparts9,10,61. Finally, the effects studied above suggest several potential applications. For example, the Larmor precession of pseudospin should generate THz emission with the frequency controlled by the amount of strain, potentially enabling a broadly tunable THz emission source62,63. If the coherence time could be extended, e.g., in TMD heterostructures48,64,65, pseudospin-based devices could be considered as qubits potentially suitable for the effective transduction of mechanical and optical information.

Methods

Sample fabrication

The devices were fabricated by dry transfer of mechanically exfoliated TMD flakes onto elliptical (8 × 3 μm) or circular trenches (diameter ~ 5 μm), which were wet-etched via hydrofluoric (HF) acid in an Au/Cr/SiO2/Si stack30,31. The strain in the membrane was induced by applying a gate voltage (typically up to ± 210 V) between the TMD flake (electrically grounded) and the Si back gate of the chip. The strain in the center was characterized using laser interferometry (see Supplementary Note S2).

Optical measurements

The devices were measured inside a cryostat (CryoVac Konti Micro) at a base temperature of 10 K. Photoluminescence (PL) measurements were carried out using a Kymera 193i spectrograph and continuous-wave (CW) lasers with either λ = 685 nm (8 μW) for quasi-resonant excitation or λ = 532 nm (6 μW) for detuned excitation. The lasers were tightly focused at the center of the membrane with a spot diameter of approximately 0.8 μm. The excitation polarization was controlled using a half-wave plate (RAC 4.2.10, B. Halle) placed before the objective (Olympus LMPlan 50x, 0.5 NA) to reduce polarization loss. The detection polarization was set using a combination of either a half-wave plate or a quarter-wave plate (for linear and circular detection, respectively) and an analyzer (GL 10, Thorlabs) before the spectrometer. To minimize the influence of coherent effects on pseudo-Zeeman splitting, we maintained excitation and detection co-polarized. The Fermi polaron splitting was measured in a Cryostation s100 cryostat (Montana Instruments) with an Isoplane 320 spectrometer (Teledyne Princeton Instruments), using a 532 nm CW laser focused to a diffraction-limited spot with an objective (Zeiss Epiplan 100x, 0.75 NA).

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available on Zenodo (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14844313). Additional data can be provided by the corresponding author upon request.

References

Glazov, M. M. et al. Exciton fine structure splitting and linearly polarized emission in strained transition-metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 106, 125303 (2022).

Yu, H., Liu, G. B., Gong, P., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Dirac cones and dirac saddle points of bright excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–7 (2014).

Glazov, M. M. & Golub, L. E. Spin and transport effects in quantum microcavities with polarization splitting. Phys. Rev. B 82, 085315. (2010).

Ilan, R., Grushin, A. G. & Pikulin, D. I. Pseudo-electromagnetic fields in 3D topological semimetals. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 29–41 (2020).

Rechcińska, K. et al. Engineering spin-orbit synthetic Hamiltonians in liquid-crystal optical cavities. Science 366, 727–730 (2019).

Ren, J. et al. Nontrivial band geometry in an optically active system. Nat. Commun. 12, 689 (2021).

Levy, N. et al. Strain-induced pseudo-magnetic fields greater than 300 tesla in graphene nanobubbles. Science 329, 544–547 (2010).

Georgi, A. et al. Tuning the pseudospin polarization of graphene by a pseudomagnetic field. Nano Lett. 17, 2240–2245 (2017).

Barsukova, M. et al. Direct observation of landau levels in silicon photonic crystals. Nat. Photon. 18, 580–585 (2024).

Barczyk, R., Kuipers, L. & Verhagen, E. Observation of Landau levels and chiral edge states in photonic crystals through pseudomagnetic fields induced by synthetic strain. Nat. Photon. 18, 574–579 (2024).

Khalaf, E., Chatterjee, S., Bultinck, N., Zaletel, M. P. & Vishwanath, A. Charged skyrmions and topological origin of superconductivity in magic-angle graphene. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf5299 (2021).

Bistritzer, R. & MacDonald, A. H. Moiré bands in twisted double-layer graphene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12233–12237 (2011).

Oh, M. et al. Evidence for unconventional superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 600, 240–245 (2021).

Hao, Z. et al. Electric field–tunable superconductivity in alternating-twist magic-angle trilayer graphene. Science 371, 1133–1138 (2021).

Wang, G. et al. Colloquium : Excitons in atomically thin transition metal dichalcogenides. Rev. Modern Phys. 90, 021001 (2018).

Manzeli, S., Ovchinnikov, D., Pasquier, D., Yazyev, O. V. & Kis, A. 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17033 (2017).

Xu, X., Yao, W., Xiao, D. & Heinz, T. F. Spin and pseudospins in layered transition metal dichalcogenides Nat. Phys.10,343–350 (2014).

Glazov, M. M. et al. Exciton fine structure and spin decoherence in monolayers of transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 89, 201302 (2014).

Ye, Z., Sun, D. & Heinz, T. F. Optical manipulation of valley pseudospin. Nat. Phys. 13, 26–29 (2017).

Kim, J. et al. Ultrafast generation of pseudo-magnetic field for valley excitons in WSe2 monolayers. Science 346, 1205–1208 (2014).

Iakovlev, Z. A. & Glazov, M. M. Fermi polaron fine structure in strained van der waals heterostructures. 2D Mater. 10, 035034 (2023).

Iakovlev, Z. A. & Glazov, M. M. Longitudinal-transverse splitting and fine structure of fermi polarons in two-dimensional semiconductors. J. Lumin. 273, 120700 (2024).

Ross, J. S. et al. Electrical control of neutral and charged excitons in a monolayer semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 4, 1474 (2013).

Glazov, M. M. Optical properties of charged excitons in two-dimensional semiconductors. J Chem. Phys. 153, 034703 (2020).

Suris, R. A. Optical Properties of 2D Systems with Interacting Electrons, 111–124 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2003).

Sidler, M. et al. Fermi polaron-polaritons in charge-tunable atomically thin semiconductors. Nat. Phys. 13, 255–261 (2017).

Efimkin, D. K., Laird, E. K., Levinsen, J., Parish, M. M. & MacDonald, A. H. Electron-exciton interactions in the exciton-polaron problem. Phys. Rev. B 103, 075417 (2021).

Rana, F., Koksal, O. & Manolatou, C. Many-body theory of the optical conductivity of excitons and trions in two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. B 102, 085304 (2020).

Rana, F., Koksal, O., Jung, M., Shvets, G. & Manolatou, C. Many-body theory of radiative lifetimes of exciton-trion superposition states in doped two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. B 103, 035424 (2021).

Hernández López, P. et al. Strain control of hybridization between dark and localized excitons in a 2D semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 13, 7691 (2022).

Kumar, A. M. et al. Strain fingerprinting of exciton valley character in 2d semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 15, 7546 (2024).

Carrascoso, F., Li, H., Frisenda, R. & Castellanos-Gomez, A. Strain engineering in single-, bi- and tri-layer MoS2, MoSe2, WS2 and WSe2. Nano Res. 14, 1698–1703 (2021).

Kovalchuk, S. et al. Neutral and charged excitons interplay in non-uniformly strain-engineered ws2. 2D Mater. 7, 035024 (2020).

Kovalchuk, S., Kirchhof, J. N., Bolotin, K. I. & Harats, M. G. Non-uniform strain engineering of 2d materials. Isr. J. Chem. 62, e202100115 (2022).

Liu, E. et al. Exciton-polaron rydberg states in monolayer MoSe2 and WSe2. Nat. Commun. 12, 6131 (2021).

Hao, K. et al. Direct measurement of exciton valley coherence in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Phys. 12, 677–682 (2016).

Dufferwiel, S. et al. Valley coherent exciton-polaritons in a monolayer semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 9, 4797 (2018).

Boule, C. et al. Coherent dynamics and mapping of excitons in single-layer MoSe2 and WSe2 at the homogeneous limit. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 034001 (2020).

Jakubczyk, T. et al. Radiatively limited dephasing and exciton dynamics in MoSe2 monolayers revealed with four-wave mixing microscopy. Nano Lett. 16, 5333–5339 (2016).

Schmidt, R. et al. Magnetic-field-induced rotation of polarized light emission from monolayer WS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 077402 (2016).

Robert, C. et al. Measurement of the spin-forbidden dark excitons in MoS2 and MoSe2 monolayers. Nat. Commun. 11, 4037 (2020).

Jamadi, O. et al. Direct observation of photonic landau levels and helical edge states in strained honeycomb lattices. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 144 (2020).

Madéo, J. et al. Directly visualizing the momentum-forbidden dark excitons and their dynamics in atomically thin semiconductors. Science 370, 1199–1204 (2020).

Bange, J. P. et al. Ultrafast dynamics of bright and dark excitons in monolayer WSe2 and heterobilayer WSe2/MoS2. 2D Mater. 10, 035039 (2023).

Godde, T. et al. Exciton and trion dynamics in atomically thin MoSe2 and WSe2 : Effect of localization. Phys. Rev. B 94, 165301 (2016).

Chow, C. M. et al. Phonon-assisted oscillatory exciton dynamics in monolayer MoSe2. NPJ 2D Mater. Appl. 1, 33 (2017).

Wang, G. et al. Polarization and time-resolved photoluminescence spectroscopy of excitons in MoSe2 monolayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 112101 (2015).

Yagodkin, D. et al. Probing the Formation of Dark Interlayer Excitons via Ultrafast Photocurrent. Nano Lett. 23, 9212–9218 (2023).

Glazov, M. M. Coherent spin dynamics of excitons in strained monolayer semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 106, 235313 (2022).

Robert, C. et al. Exciton radiative lifetime in transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 93, 205423 (2016).

Raiber, S. et al. Ultrafast pseudospin quantum beats in multilayer WSe2 and MoSe2. Nat. Commun. 13, 4997 (2022).

Rivera, P. et al. Intrinsic donor-bound excitons in ultraclean monolayer semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 12, 871 (2021).

He, M. et al. Valley phonons and exciton complexes in a monolayer semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 11, 618 (2020).

Chen, F.-W. & Wu, Y.-S. G. Theory of field-modulated spin valley orbital pseudospin physics. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013076 (2020).

Sim, S. et al. Ultrafast quantum beats of anisotropic excitons in atomically thin ReS2. Nat. Commun. 9, 351 (2018).

Kumar, A. M. et al. Strain control of valley polarization dynamics in a 2d semiconductor via exciton hybridization. Nano Lett. 42, 15164–15172 (2025).

Bercioux, D. & Lucignano, P. Quantum transport in rashba spin–orbit materials: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 78, 106001 (2015).

Plotnik, Y. et al. Analogue of rashba pseudo-spin-orbit coupling in photonic lattices by gauge field engineering. Phys. Rev B 94, 020301 (2016).

Rong, K. et al. Photonic Rashba effect from quantum emitters mediated by a Berry-phase defective photonic crystal. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 927–933 (2020).

Mittenzwey, H. et al. Ultrafast optical control of rashba interactions in a tmdc heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 026901 (2025).

Plotnik, Y. et al. Analogue of rashba pseudo-spin-orbit coupling in photonic lattices by gauge field engineering. Phys. Rev. B 94, 020301 (2016).

Yagodkin, D. et al. Ultrafast photocurrents in mose2 probed by terahertz spectroscopy. 2D Mater. 8, 025012 (2021).

Ma, E. Y. et al. Recording interfacial currents on the subnanometer length and femtosecond time scale by terahertz emission. Sci. Adv. 5, (2019).

Zhai, D. & Yao, W. Layer pseudospin dynamics and genuine non-abelian berry phase in inhomogeneously strained moirê pattern. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 266404 (2020).

Kumar, A. et al. Spin/valley coupled dynamics of electrons and holes at the mos2-mose2 interface. Nano Lett. 21, 7123–7130 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The Berlin groups acknowledge the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for financial support through the Collaborative Research Center TRR 227 Ultrafast Spin Dynamics (project B08), Project GZ: BO 5142/4-1, the Priority Program SPP 2244, the German Excellence Strategy - EXC3112/1 - 533767171 (Center for Chiral Electronics), and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, project 05K22KE3). The Saint Petersburg group acknowledges financial support by the RSF Project 23-12-00142 (theory); Z.A.I. gratefully acknowledges the BASIS foundation. K.I.B. acknowledges illuminating discussions with Christiane Koch, Robert Bittl, and Stephanie Reich.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Y. and K.I.B. conceived the project. Z.A.I. and M.M.G. developed the theory. D.Y., A.M.K., A.D., and C.G. designed the experimental setup. D.Y., K.B., A.M.K., and B.H. prepared the samples. D.Y., K.B., A.M.K., and A.D. performed the optical measurements. O.Y. performed mechanical simulations. D.Y. and K.B. analyzed the data. D.Y. and K.I.B. wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yagodkin, D., Burfeindt, K., Iakovlev, Z.A. et al. Fermi polarons under strain-induced pseudomagnetic fields. Nat Commun 16, 10232 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66192-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66192-y