Abstract

The technological revolution driven by artificial intelligence has significantly improved the hardware performance, but energy consumption remains a critical bottleneck. The state-of-the-art retinomorphic devices, as core components of artificial intelligence hardware, excel in feature extraction but are constrained by passive attention mechanisms that lack flexibility of actively extracting additional features. Inspired by the human visual system, this work introduces a volitional neuromorphic device with active volitional attention regulation. By leveraging gate-voltage-tunable photoconductance to generate adjustable differential spectral response and employing neural networks to evaluate spectral reconstruction accuracy, the device achieves selective task perception. Experimental results demonstrate a data compression ratio of 1.17% and an extreme information energy efficiency of 0.625 pJ/bit. This advancement not only advances retinomorphic hardware design but also provides a sustainable pathway for energy-efficient hyperspectral imaging and next-generation neuromorphic computing systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The current landscape of technological revolution, featured by the astonishing achievements of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, is ushering in a groundbreaking epoch1,2,3. State-of-the-art AI hardware, rooted in the classic Von Neumann architecture, showcases unparalleled performance but at a considerable energy cost4,5,6. For instance, cutting-edge H100 GPUs are projected to consume over 13 terawatt-hours of energy annually7,8, underscoring a critical concern for energy efficiency, particularly in data-driven era.

Human visual system, renowned for its remarkable efficiency in perceiving, transducing, and interpreting information at approximately 1.0 pJ/bit9,10,11,12, provides a promising avenue to tackle the aforementioned concern. This efficiency stems from the intricate mechanisms of visual attention, encompassing both passive autonomic attention (PAA) and active volitional attention (AVA)13,14. As illustrated in Fig. 1a, PAA, naturally attracted by external stimuli, preferentially dominates the process of forming ideology directly from significant signal attention. It involves the fundamental light signal receiving, converting and pre-processing, realizing the primary motion detection. The AVA is further intervened as the subjective selecting command is sent to the brain’s central thinking region guided by prior knowledge and objectives. Accordingly, visual attention is directed through priority maps to efficiently focus on key information while ignoring irrelevant stimuli, which facilitates selective feature extraction and thus an extreme energy efficiency. Leveraging insights from the human visual system holds immense significance in the development of intelligent devices15,16,17,18.

Schematic representation for a active volitional attention (AVA) modulation of and b the proposed volitional neuromorphic devices. Three key operations are included, incident light receiving for photoelectric conversion, neural network training for spectral reconstruction, and a feedback mechanism for error calibration. c The TEM image and EDX mapping for the vertical cross-section of MoSe2/h-BN/MoS2 heterostructure. d The Raman spectra of MoS2, h-BN and MoSe2/h-BN/MoS2 heterostructure. The shadings represent the characteristics Raman peaks for clarity. e Resolved XPS of Mo, Se, S, B and N core levels.

Encouragingly, the integration of visual attention into two-dimensional materials-based retinomorphic vision devices has demonstrated milestone breakthroughs, navigating versatile and complicated scenarios, such as intelligent imaging, in-sensor computing, all-in-one hardware and etc19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Nevertheless, they predominantly rely on PAA, constraining their capacity for efficient feature extraction. This results in redundant sensory data and heightened power consumption, especially in multi-sport scenarios such as road tracking, biology follows, adaptive cruise control, etc27. which highlights the critical necessity of developing volitional neuromorphic devices with exceptional energy efficiency28.

Here, we demonstrate volitional neuromorphic devices with extreme energy efficiency of sub-picojoules per bit by emulating the hierarchical functions of the human visual system. In addition to PAA for dynamic feature extraction, AVA empowers our devices to precisely target specific objects and track their trajectories based on spectral features with an average accuracy over 93%. Such high precision originates from the active feedback and correction attained by optimizing gate-tunable differential spectral photo-response, inspired by biological transsaccadic memory. As a result, the volitional neuromorphic devices exhibit a data compression ratio of 1.17%, minimizing redundant data while approaching the IEE of the human visual system at 0.625 pJ/bit. This advancement is poised to redefine the landscape of AI hardware development, emphasizing brain-like energy efficiency in non-Von Neumann architecture-based systems.

Results

Design of volitional neuromorphic devices

Given that the participation of AVA enables a high operation efficiency and low power consumption, we proposed volitional neuromorphic devices with extreme energy efficiency by simulating the fovea response to regions of interest, configured with a van der Waals heterostructure of MoSe2/h-BN/MoS2 (Fig. S1). The structural, interfacial, morphological and elementary characteristics are evaluated by conducting transmission electron microscope (TEM), Raman, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), atomic force microscope (AFM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), respectively. As shown in Fig. 1c, clear interfaces and hierarchical element distribution are observed in the vdWs heterostructure. The corresponding characteristic E2g (383 cm−1, 233 cm–1 and 1350 cm–1) and A1g (408 cm–1) peaks are identified for few-layer MoS2 flakes (as floating gate), MoSe2 flakes (as conduction channel) and h-BN flakes (as potential barrier), respectively (Fig. 1d)29,30,31. To further evaluate the interfacial characteristics, the resolved XPS spectra of Mo 3d, Se 3d, S 2p, B 1s and N 1s core levels are analyzed in Fig. 1e29,30,31, and the symmetric peak profiles of h-BN suggest that vdWs interactions predominantly govern the interfacial characteristics32. In addition, the morphology profile and element distribution are recorded in Fig. S2, S3, further confirming the successful fabrication of proposed heterostructure with floating gate. As the aforementioned AVA in human visual system (Fig. 1a), the fovea reflects the polarity peak change of the cone photoreceptor, ensuring the fundamental information pre-processing. When an attention is focused on a region of interest, the corresponding neuronal potential activity is immediately enhanced and feeds back to the cone photoreceptors, promoting selective task perception and cognition. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 1b, the device-level AVA is proposed by introducing an active spectral feedback circulation, which progressively manipulates voltage feedback until outputs optimal spectral reconstruction accuracy. Specifically, MoSe2 photoactive channel receives optical signals and simulates the weight of synapse, and MoS2 conduction channel maintains the persistent current to realize the memory function. Subsequently, programmable gate voltage (Vg) pulses, serving as electrical stimulus, are applied to modulate the photoconductance, which generate both non-volatile positively and negatively photoconductive photocurrent (PPC and NPC) over visible spectrum to achieve polarity regulation (similar to cone cells). The differential operation between NPC and PPC photoconductive currents enables polarity-regulated spectral reconstruction by synergistically suppressing interference and amplifying target signals. For the same reason, to observe specific objects within all spectral information, the input voltage is carefully adjusted in the manner of designated optimal Vg for each wavelength, referring to the specific wavelength with the maximum reconstructed accuracy. Accordingly, only the spectral signal of specific interest can be emphasized instead of another irrelevant spectrum. This aligns with the natural way human processes and prioritizes visual information, ultimately enabling the targeting and localization of objects (e.g., a runner wearing a blue shirt). This can maintain 93% spectral recognition accuracy even under 1.17% data compression by dynamically balancing noise suppression and feature retention. Such operation guarantees an intelligent detection with subjective feature selections, which significantly reduces irrelevant redundant sensory data while effectively allocates processing resources to reduce energy consumption. As a result, AVA-involved volitional neuromorphic device adheres to the intelligent philosophy of the human brain that prioritizes appointed spectral sensory inputs over others, leading to an extreme energy efficiency, which provides an innovative way to establish autonomous selection of targeting and tracking.

Versatile characteristics of volitional neuromorphic devices

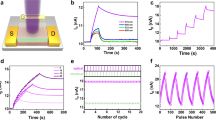

The AVA-involved sensing, memory, and computing capabilities are essential prerequisites in volitional neuromorphic devices, which ensure accurate targeting and tracking with extreme energy efficiency33,34. The intrinsic responsive characteristics are priorly examined under illumination with primary colors, as shown in Fig. 2a. The as-fabricated device demonstrates an obvious photoresponse that over two orders of magnitude larger than dark current, accompanied by exceptional responsivity, detectivity and noise-equivalent-power with a low incident light power of 0.1 mW (Figs. S4–S6). The photoconductive behaviors are subsequently evaluated by applying programmable Vg pulses (Fig.2b, c). A single Vg pulse is initially applied for 1 s, and the light is simultaneously switched on once disconnecting the gate voltage. It is clear that both PPC and NPC are of progressive output, good uniformity and reproducibility. Notably, their response are much more prompt (rise time <160 μs, Fig. S7) than HVS (~50 ms), which effectively protects from capturing ghost images, especially in the scenario of high-speed motion recognition35,36. Good photoresponsive characteristics and floating gate effect are also validated in the manner of pulse number and bias voltage (Figs. S8–S10). Meanwhile, this device possesses a linear memory window of ~80 V with a large stored charge density of 5.65 × 1012 cm–2, and maintains a good non-volatile stability (Fig. S11), which is beneficial for successive differential operation. These attractive data-perceiving and storing capabilities are originated from the appropriate arrangement of vdWs heterojunction that allows an efficient Fowler-Nordheim tunneling. The corresponding band alignment and carrier dynamics are elucidated in Fig. S12. Briefly, electrons and holes initially undergo accumulating (MoSe2 conduction channel) and trapping (MoS2 modulation channel) processes as applying negative Vg. The electrons subsequently tunnel to MoS2 followed by the recombination with the trapped holes upon light illumination. Accordingly, the decreased number of electrons weakens the photoconductivity, resulting in a reduced photocurrent (i.e., NPC) and vice versa for PPC37.

a Logarithmic I–V curves measured in dark and under illumination of primary colors with the same intensity of 0.1 mW/cm2. Cumulative b positive and c negative photoconductivity measurements with progressive multilevel states. The pulse width and interval of incident light are programmed as 200 ms and 10 s, respectively. d Photocurrent mapping as a function of gate voltage within the spectrum ranging from 450 to 800 nm. The gate voltage ranges from −40 to 40 V with a step size of 2 V and a bias voltage of 1 V. e The histogram of the optimal gate voltage corresponding to the minimum differential photoresponse. Each color represents its corresponding wavelength.

The corresponding spectral response database is established via adequately mapping the photoresponse as functions of spectrum (450–800 nm) and gate voltage (−40 to 40 V), laying a foundation for the proposed device-level AVA feedback. As shown in Fig. 2d, PPC clearly transforms to NPC as tuning the direction of in-vertical electric field by switching Vg from positive to negative, which is consistent with aforementioned device physics. Notably, both PPC and NPC possess a gradual response to both distinctive wavelength and gate voltage, indicating effective photoconductive modulation that enables the subsequent differential operation and thus spectral reconstruction. As mentioned earlier, differential current (Idiff) obeying Kirchhoff’s law is essential for realizing visual attention, and the smaller Idiff, the better object contour clarity, as evidenced in Fig. S1323,38. Meanwhile, differential signals can suppress common-mode noise and lead to a higher information compression ratio39,40. In addition, spatial-temporal operations (edge enhancement and extraction) of static and dynamic objects are validated by manipulating PPC/NPC characteristics of the device (Figs S14–S17). In this case, the distribution of optimal gate voltages (\({V}_{{{\rm{g}}}}^{{I}_{{{\rm{diff}}}-\min }}\)) corresponding to each wavelength with an interval of 10 nm is recorded as the differential current reaches its minima (Idiff-min), as shown in Fig. 2e. It is worth noting that each color equips its corresponding optimal set of gate voltage, e.g., blue (4 and −14 V), green (8 and −32 V) and red (10 and −34 V). By legitimately analyzing the statistics of \({V}_{{{\rm{g}}}}^{{I}_{{{\rm{diff}}}-\min }}\) distribution, it is reasonably believed derived operation condition of primary colors can facilitate the subsequent implementation of AVA with adjustable feedback.

Spectral active feedback mechanism

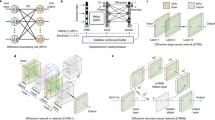

With the aforementioned differential current response for different wavelengths in the volitional neuromorphic devices, the device-level AVA with spectral active feedback is conceptualized. This operation leverages the dynamic modulation capabilities of neuromorphic devices to enhance the accuracy of motion spectra and thus focus on objects. Therefore, the crucial aspect of implementation lies in the reconstruction of the object spectrum. The reconstruction process is briefly outlined in Fig. 3a–c. The single differential photocurrent matrix (Idiff-pc) with different Vg and wavelength is inputted, and each unknown reflection image input yields a reconstructed spectrum after neural network training via gradient descent, explained by the formula below:

where Г(Vpositive, Vnegative) is the spectral response matrix, Svector(λ) is a vector representing the spectrum, which is dependent on the wavelength resolution, and ν denotes noise. By performing a comparative analysis between the reconstructed spectra Svector(λ) and the corresponding reference spectra Svector(λ) within the training dataset, the neural network undergoes optimization through the resolution of Eq. 2:

a Parameter input. By employing nonlinear transformation expansion, the dimensionality of the input space is increased to 16 dimensions. b Residual neural networks (ResNet) training. c Spectral reconstruction of white light. d Average reconstruction accuracy for all voltage combinations under 450–800 nm. e The corresponding voltage combination for 733 nm light signals. The optimal voltage combinations marked as red squares are assigned to the minimum value of Idiff-pc. f The accuracy change curve for the three primary colors (460 nm, 554 nm, and 697 nm) and the selected 733 nm. The shadings represent the corresponding error bars for each color, and the “star” symbols suggest the optimal gate voltage for achieving maximum spectral reconstruction accuracy.

During training, a combination of Mean Squared Error and L1 norm was used as the loss function. After only 79 rounds of training, the model ultimately stabilized, minimizing convergence issues and restricting the solution space (Figs. S18, S19)41,42. Utilizing the preferred light source (xenon lamp), simulative reconstruction of different transmission spectra can be obtained in Fig. 3c and Fig. S20. We observed that the spectrum reconstructed from the optimized neural network agrees well with the measured reference spectrum. To further evaluate the model performance, the reconstruction error of the model at various wavelengths is recorded, as presented in Fig. 3d. Across the entire dataset, the model achieved an accuracy rate of 92.2% with a spectral resolution of approximately 0.24 nm.

The accuracy of spectral reconstruction hinges on voltage and the resulting Idiff-pc, and the lower Idiff-pc can enhance the effectiveness of motion recognition. By optimizing the voltage corresponding to Idiff-pc, accuracy can be improved for specific wavelengths, thereby modulating signals from desired motion targets. This approach effectively suppresses non-target spectral signals, highlighting signals from spectral motion target, the corresponding process is illustrated in Fig. 3d–f. To begin, we establish the average reconstruction accuracy as the baseline for each wavelength across all voltage combinations in Fig. 3d. Taking the spectral information at 733 nm as an example, the Vg mapping for this wavelength can be derived (Fig. 3e). By sorting the differential currents, the minimum differential photocurrent and the corresponding optimal set of gate voltages are obtained. Multiple minima of Idiff-pc values are identified, guiding the subsequent spectral reconstruction process for each voltage combination. By subtracting the established average accuracy curve from the accuracy spectrum obtained under the voltage combination corresponding to the minimum Idiff-pc, we reveal the accuracy variation across the spectrum. This comparison aids in assessing whether the wavelength achieves optimal improvement in spectral reconstruction accuracy. As depicted in Fig. 3e, spectral reconstruction accuracy peaks at 733 nm when utilizing the specific voltage combination of (–20, 38 V). This optimal voltage configuration is determined through iterative optimization, reflecting the device’s learning process and serving as a crucial condition for subsequent operational “consciousness” formation of the device. Furthermore, the same procedure demonstrates maximum reconstruction accuracy in red, green, and blue light (Fig. 3f), further validating the effectiveness of this method across different wavelengths.

Active target demonstration

The device-level AVA is believed to easily demonstrate its advantages in numbers of scenarios to actively identify the desired target among multiple moving objects. Building upon feature extraction, it can achieve fusion and superposition of features through accumulation and averaging. This operation is beneficial for obtaining trajectories of multispectral moving objects captured in the images. The proof-of-concept demonstration is illustrated in Fig. 4a–c, sustained attention is illustrated for individuals moving in red, green, and blue colors. The 3D plots effectively display each person’s trajectory in a distinct color, with the backdrop of a tiled floor for spatial reference. The figures clearly delineate the paths of the individuals, demonstrating the system’s ability to track them accurately amidst potential distractions. It is evident that the information captured in these images is clear and precise, offering a stark contrast to the data obtained through PAA, which appears cluttered and chaotic (Fig. S21). In addition, the extraction of moving objects and color tracking were demonstrated through single device whiskbroom scanning system in Figs. S22, S23. Figure 4d–f illustrates the recognition accuracy of the device over time at different wavelengths. For all frame rates, the recognition accuracy often exceeds 93%, with small fluctuations and relatively few outliers, indication of reliable recognition performance. The AVA significantly enhances image compression by prioritizing areas with high informational content, thereby optimizing storage and improving the efficiency of data transmission without sacrificing key visual details. Dividing the pixels in the grayscale range of 0–256 into 20 equally spaced statistical units. The spectral reconstruction mechanism achieves high-efficiency data compression by selectively preserving the target object’s characteristic spectral channels. Key principles include: (1) A threshold comparator filters pixels with effective edges in Fig. 4g (lower part). (2) The original image spectrum is compressed to only the color channel of the target object in Fig. 4g (upper part). Static backgrounds and irrelevant moving objects are ignored, which can significantly reduce data volume, ultimately achieving a compression ratio of 1.17%, which outperforms other neuromorphic devices as summarized in Table S4 (Detailed calculations in Supplementary Information). In addition, the AVA mechanism contributes to low energy consumption by selectively processing only relevant information. The information-energy efficiency (IEE) is comprehensively evaluated through the power consumption aspect of human like visual information processing, quantified in joules per bit(J/bit)10,43,44. Utilizing an evaluation method based on the resting state and action potential of human brain neurons (Fig. S24), the IEE of our volitional neuromorphic device can be as low as 0.625 pJ/bit. This efficiency is comparable to the energy consumption of neurons in the human retina, which is approximately 0.714 pJ/bit, and is slightly higher than the energy consumption observed in the neurons of mouse and Drosophila, as shown in Fig. 4h10,45,46. Meanwhile, IEE demonstrates obvious advantages compared to other neuromorphic devices (Table S5). This comparison highlights the potential of the AVA mechanism to approach near-biological levels of energy efficiency in AI systems. Notably, a good device-to-device repeatability has been substantiated via additional validations on vdWs heterostructure, device performance and accuracy simulation (Figs. S25–29). By employing AVA, a more comprehensive and refined understanding of the scene was achieved, facilitating effective tracking and analysis of moving objects with multispectral features.

a Red, b green and c blue moving object and their motion trajectories. The box plots denoting the distributions of recognition accuracy of device over time for moving objects in (d) red, (e) green and (f) blue. All box plots include median line, mean values, outliers and interquartile range (25–75%). g The fundamental of data compression after AVA mechanism. The color channel only selects objects and discards background data, and the pixel brightness distribution of the original image and AVA mechanism is normalized. h Comparison of information-energy efficiency for different objects: 0.625 pJ/bit of volitional neuromorphic devices (VND), 0.714 J/bit of human brain, 0.574 pJ/bit of mouse and 0.329 pJ/bit of Drosophila.

We have successfully demonstrated a sub-picojoule-per-bit volitional neuromorphic device by introducing an AVA. The intervened AVA operation with active feedback and real-time correction, leveraging gate-tunable differential spectral characteristics, enables our device precisely identify and track specific objects with an impressive accuracy over 93%. As a result, the volitional neuromorphic device boasts a data compression ratio of 1.17%, which significantly reduces redundant data and achieves an extreme information energy efficiency of 0.625 pJ/bit. These advancements mark a major breakthrough in neuromorphic engineering, highlighting the potential to redefine the future of AI hardware with brain-like efficiency.

Methods

Materials: Heavily p-doped Si substrates coated with SiO2 layer (90 nm) were purchased from Corning Inc. The MoSe2, h-BN and MoS2 were supplied by MaiTa Corp. (Nanjing, China). Acetone (IPA, anhydrous, 99.5%), isopropanol (anhydrous, 99.5%), ethanol (anhydrous, 99.9%) were purchased from Aladdin.

Device fabrication: Thoroughly clean the SiO2/Si substrate in acetone, IPA, and ethanol using ultrasonic treatment for 10 min. Use Scotch tape to mechanically exfoliate off MoS2 flakes, h-BN, and MoSe2 flakes, and sequentially transfer them onto a SiO₂/Si substrate with PDMS assistance, heating to 75 °C, 65 °C, and 75 °C, respectively, during each transfer. The electrode patterning was carried out by ultraviolet lithography of the MoSe2/h-BN/MoS2. Then, the Cr/Au (10/60 nm) contact pads were deposited by electron beam evaporation, followed by a standard lifted-off process in acetone. In order to improve the ohmic contacts between Au electrodes and MoSe2, the as-fabricated devices were annealed at 300 °C in the argon atmosphere. Furthermore, we have successfully fabricated a 3 × 3 array device (Figs. S30, S31). Despite slight device-to-device variations (Fig. S32), the essential functional switching mechanism remains consistently robust. Future work will therefore focus on refining heterostructure fabrication process to enhance device-to-device reproducibility and fabrication variability, which represents one of the critical steps for scaling towards intelligent systems.

Material and device characterizations: Raman, PL, and AFM (Atomic Force Microscope) of MoSe2/h-BN/MoS2 were measured by a Raman-atomic force system (Alpha300RA, WITec) under 532 nm excitation laser diode (2 mW). TEM and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDX) of MoSe2/h-BN/MoS2 were represented by Electron microscope Talos F200S and Spectrum SUPER X, respectively. The morphology and elemental mapping were measured by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM, ZEISS EV0MA15) and Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (EDS, SDD type 80T), respectively. XPS spectra of heterojunctions were measured using Thermo Scientific K-Alpha with an Al ka (hv = 1486.8 eV) emission source. The optoelectronic properties of the photoelectric memory were measured with the SemiProbe probe station and a semiconductor parameter analyzer (Keithley 4200), and Platform Design Automation (PDA, FS-Pro). The lasers of 450, 520 and 635 nm were emitted and controlled by a Programmable DC Power Supply (Itech Electronic, IT6100B), a function generator and an irradiatometer. The combined control of a supercontinuum light source (SuperK Compact) and tunable fiber filter (WLTF-NM-P-1550) is used to emit lasers of different wavelengths and light with varying linewidths. The noise spectral density was measured using a semiconductor parameter analyzer equipped with a noise testing module (FS-Pro, Primarius). All the measurements for devices were operated 4 ambient conditions.

Implementation of ResFCNet: In the AVA simulation framework, the neural network consists of an input layer accepting 16-dimensional feature vectors, followed by a sequence of residual blocks with progressively increasing dimensionality (256, 512, and 1024 units, respectively). Each residual block is composed of multiple dense layers with regularization and ReLU activation functions, with skip connections to preserve gradient flow in deep network configurations. The output layer is designed to produce 1650-dimensional vectors for spectral reconstruction. For a comprehensive guide on how to reproduce the specific results and figures presented in this work, including the model training (Fig. S19) and spectral reconstructions (Fig. 3c–f and Fig. S20), please refer to the Appendix: Implementation and Utilization of the ResFCNet Architecture in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

The data that support the conclusions of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper. To ensure full transparency and reproducibility of our work, the primary dataset of ResFCNet has been deposited in the Hugging Face repository (https://huggingface.co/datasets/IFFS-ODS/SpectrumReconstruction_Diff).

Code availability

The codes used for simulation and data plotting are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. The core implementation code of ResFCNet is publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/IFFS-ODS/SpectrumReconstruction_ResFCN), with specific access details available in the Supplementary Information.

References

Krenn, M. et al. On scientific understanding with artificial intelligence. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 761–769 (2022).

Allen, R. C. Reboot for the AI revolution. Nature 550, 324–327 (2017).

Klinger, J., Mateos-Garcia, J. C. & Stathoulopoulos, K. A narrowing of ai research? SSRN Electron. J. 379, 884–886 (2020).

Mark Horowitz. Computing’s energy problem (and what we can do about it). In Proc. IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference, 10–14 (IEEE, 2014).

Xu, X. et al. Scaling for edge inference of deep neural networks. Nat. Electron. 1, 216–222 (2018).

Gholami, A. et al. AI and memory wall. IEEE Micro 44, 33–39 (2024).

Wiecha, P. R. Deep learning for nano-photonic materials—the solution to everything!? Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 28, 101129 (2024).

Uddin, M. G. et al. Broadband miniaturized spectrometers with a van der Waals tunnel diode. Nat. Commun. 15, 571 (2024).

Eldred, K. C. et al. Thyroid hormone signaling specifies cone subtypes in human retinal organoids. Science 362, 1–7 (2018).

Harris, J. J., Jolivet, R., Engl, E. & Attwell, D. Energy-efficient information transfer by visual pathway synapses. Curr. Biol. 25, 3151–3160 (2015).

Gollisch, T. & Meister, M. Eye smarter than scientists believed: neural computations in circuits of the retina. Neuron 65, 150–164 (2010).

Mehonic, A. & Kenyon, A. J. Brain-inspired computing needs a master plan. Nature 604, 255–260 (2022).

Theeuwes, J. Top–down and bottom–up control of visual selection. Acta Psychol. 135, 77–99 (2010).

Connor, C. E., Egeth, H. E. & Yantis, S. Visual attention: bottom-up versus top-down. Curr. Biol. 14, R850–R852 (2004).

Gu, L. et al. A biomimetic eye with a hemispherical perovskite nanowire array retina. Nature 581, 278–282 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Perovskite-based color camera inspired by human visual cells. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 43 (2023).

Li, Q., van de Groep, J., Wang, Y., Kik, P. G. & Brongersma, M. L. Transparent multispectral photodetectors mimicking the human visual system. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–8 (2019).

Zhu, Y. et al. Non-volatile 2D MoS2/black phosphorus heterojunction photodiodes in the near- to mid-infrared region. Nat. Commun. 15, 6015 (2024).

Li, T. et al. Reconfigurable, non-volatile neuromorphic photovoltaics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1303–1310 (2023).

Huang, P.-Y. et al. Neuro-inspired optical sensor array for high-accuracy static image recognition and dynamic trace extraction. Nat. Commun. 14, 6736 (2023).

Liao, F. et al. Bioinspired in-sensor visual adaptation for accurate perception. Nat. Electron. 5, 84–91 (2022).

Lee, S., Peng, R., Wu, C. & Li, M. Programmable black phosphorus image sensor for broadband optoelectronic edge computing. Nat. Commun. 13, 1485 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. All-in-one two-dimensional retinomorphic hardware device for motion detection and recognition. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 27–32 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Networking retinomorphic sensor with memristive crossbar for brain-inspired visual perception. Natl. Sci. Rev. 8, nwaa172 (2021).

Mennel, L. et al. Ultrafast machine vision with 2D material neural network image sensors. Nature 579, 62–66 (2020).

Wang, C.-Y. et al. Gate-tunable van der Waals heterostructure for reconfigurable neural network vision sensor. Sci. Adv. 6, 1–7 (2020).

Jiménez-Bravo, D. M., Lozano Murciego, Á, Sales Mendes, A., Sánchez San Blás, H. & Bajo, J. Multi-object tracking in traffic environments: a systematic literature review. Neurocomputing 494, 43–55 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. All two-dimensional integration-type optoelectronic synapse mimicking visual attention mechanism for multi-target recognition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 1–16 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Fabry-Perot interference and piezo-phototronic effect enhanced flexible MoS2 photodetector. Nano Res. 15, 4395–4402 (2022).

Pan, S. et al. Light trapping enhanced broadband photodetection and imaging based on MoSe2/pyramid Si vdW heterojunction. Nano Res. 16, 10552–10558 (2023).

Fukamachi, S. et al. Large-area synthesis and transfer of multilayer hexagonal boron nitride for enhanced graphene device arrays. Nat. Electron. 6, 126–136 (2023).

Lin, Y. C. et al. Low-energy implantation into transition-metal dichalcogenide monolayers to form Janus structures. ACS Nano 14, 3896–3906 (2020).

Tang, C. et al. From brain to movement: wearables-based motion intention prediction across the human nervous system. Nano Energy 115, 108712 (2023).

Feng, G., Zhang, X., Tian, B. & Duan, C. Retinomorphic hardware for in-sensor computing. InfoMat 5, e12473 (2023).

Daly, S. et al. Temporal deployment of attention by mental training: an fMRI Study. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 20, 669–683 (2020).

Luo, W. et al. End-to-end active object tracking and its real-world deployment via reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 42, 1317–1332 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Negative photoconductance in van der Waals heterostructure-based floating gate phototransistor. ACS Nano 12, 9513–9520 (2018).

Wu, G. et al. Miniaturized spectrometer with intrinsic long-term image memory. Nat. Commun. 15, 676 (2024).

Ng, S. E. et al. Retinomorphic color perception based on opponent process enabled by perovskite bipolar photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 36, 2406568 (2024).

Han, J. et al. 2D Materials-based photodetectors with bi-directional responses in enabling intelligent optical sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2423360 (2025).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 770–778. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 (IEEE, 2016).

Kim, T., Oh, J., Kim, N. Y., Cho, S. & Yun, S.-Y. Comparing Kullback-Leibler Divergence and Mean Squared Error Loss in Knowledge Distillation. In Proc. Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2628–2635. https://doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2021/362 (International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 2021).

Strong, S. P., Koberle, R., de Ruyter van Steveninck, R. R. & Bialek, W. Entropy and information in neural spike trains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 197–200 (1998).

Dayan, P. & Abbott, L. F. Theoretical neuroscience: computational and mathematical modeling of neural systems. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 15, 154–155 (2001).

Niven, J. E., Anderson, J. C. & Laughlin, S. B. Fly photoreceptors demonstrate energy-information trade-offs in neural coding. PLoS Biol. 5, e116 (2007).

Berger, T. & Levy, W. B. A mathematical theory of energy efficient neural computation and communication. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 56, 852–874 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1401100, 2023YFB3611400), National Natural Science Foundation of China (52302164, 52202165 and 62304031, 62422410), Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (2024NSFSC0218), and Special Funding from Sichuan Postdoctoral Research Project (308324).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S., W.H., and J.W. conceived the idea and directed the collaboration and execution. Y.H. and Q.S. fabricated the devices and performed the measurements. Y.H., Q.S., F.D., F.W., L.L., Y.D., X.Z. Y. W., and C.H. analysed the experimental data. Y.H., Q.S. and Y.D. did the device simulation. Q.S., C.L., and W.R. collected the raw signals of motion images. Y.H., Q.S., F.D., F.W., L.L., W.R., and X.L. cowrote the manuscript with contributions from all the authors. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Baker Mohammad, Bowen Zhu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Sun, Q., Dai, F. et al. Sub-picojoule-per-bit volitional neuromorphic devices for precise targeting and tracking. Nat Commun 17, 339 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66295-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66295-6