Abstract

Oseltamivir, a neuraminidase (NA) inhibitor, is currently the most widely used antiviral drug for influenza worldwide. The emergence of primary oseltamivir-resistant mutations in NA protein of seasonally circulating viruses has been extensively monitored to evaluate drug efficacy. In addition to primary mutations in NA, mutations in the viral hemagglutinin (HA) protein have been observed to arise alongside NA mutations in previous laboratory selection experiments under neuraminidase inhibitor pressure, such HA mutations have not yet been reported in circulating viruses. Here, we present the experimental evidence that an A(H1N1)pdm09 virus can independently acquire oseltamivir-resistance mutations K130N or K130E in the HA receptor binding site (RBS) during serial passages under drug selection. Notably, HA-K130N mutation has been prevalent in currently circulating seasonal viruses worldwide since 2019. More importantly, we demonstrate that the HA-K130N can enhance the oseltamivir resistance conferred by the well-characterized NA-N295S mutation. Our study provides essential evidence that mutations in HA are closely associated with the occurrence of neuraminidase inhibitor resistance, highlighting the urgent need for global monitoring and assessment of oseltamivir-resistant mutations in the HA protein, in addition to NA, during the ongoing H1N1 epidemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Influenza viruses pose a significant global threat and have caused four pandemics since 19181. The viral envelope contains two glycoproteins: hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). HA mediates receptor binding to sialic acids (SAs) on the host cell membrane and facilitates membrane fusion to initiate infection, whereas NA possesses sialidase activity, cleaving SAs to promote progeny virus release and prevent HA-mediated virion aggregation2,3,4. The functional balance between HA and NA is crucial: during early infection, virus particles must penetrate the heavily sialylated mucus layer and attach to the host cell, while at later stages, newly produced virions must detach efficiently from the cell surface5,6,7,8,9.

Oseltamivir is a widely used antiviral drug for influenza treatment. It functions as a sialic acid analog, binding to the NA active site and preventing cleavage of SAs bound to HA10,11. By disrupting the functional balance between HA and NA, oseltamivir limits the efficient release of progeny virions and hinders viral penetration through the mucus layer, thereby reducing infectivity5,12. Mutations near the NA substrate-binding pocket, such as NA-H275Y, NA-R293K, and NA-N295S (N1 numbering; H274Y, R292K, and N294S in N2 numbering), have emerged in previously circulating viruses, weakening oseltamivir binding and conferring drug resistance12,13,14,15. The fitness of these NA mutant viruses is often compromised, which limits their infectivity and transmissibility10,15,16,17. However, during 2007 and 2008, oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 strains became predominant among human seasonal isolates12,18,19, probably due to “permissive” secondary mutations, such as NA-V234M and NA-R222Q, which compensated for the deleterious effects of NA-H275Y14,20. In addition to primary NA resistance mutations, compensatory HA mutations have been observed alongside NA mutations in laboratory neuraminidase inhibitor (NAI) selection experiments8,21,22,23,24,25. These HA mutations typically reduce viral binding affinity for sialic acid receptors, thereby decreasing dependence on NA activity during virion release.

The emergence of oseltamivir resistance in influenza viruses has prompted the consideration of combining two antivirals with distinct viral targets as a promising strategy to control the virus and improve antiviral efficacy compared to monotherapy. Favipiravir, a nucleoside analog, is a broad-spectrum antiviral that targets the viral RNA synthesis process and exhibits activity against a variety of RNA viruses, including influenza virus26,27. Currently, favipiravir is approved for the treatment of novel or re-emerging influenza viruses in Japan and China. Our previous clinical trial showed that the combining of favipiravir with oseltamivir may accelerate clinical recovery compared to oseltamivir monotherapy in the cases of severe influenza28. Since favipiravir can increase the mutation rate of the influenza virus and induce lethal mutagenesis29, its use in combination therapy could potentially accelerate virus evolution and promote mutations with resistance potential. However, our previous study found that combination therapy with oseltamivir and favipiravir had little effect on viral diversity compared to the untreated virus, possibly due to the short duration of viral evolution in vivo, as most viruses are rapidly eliminated in patients30. Nevertheless, it remains uncertain whether novel resistant strains might emerge if the virus survives longer under antiviral pressure, as observed in elderly or immunocompromised patients, where viral shedding is prolonged, and antiviral treatment durations are extended31,32.

In this study, we serially passaged the influenza virus under antiviral pressure and observed a progressive reduction in susceptibility to oseltamivir, both with and without prior favipiravir exposure. Whole-genome sequencing revealed that this resistance was driven not by mutations in neuraminidase (NA) but by point mutations K130N or K130E in hemagglutinin (HA), each of which independently conferred oseltamivir resistance. Notably, HA-K130N further enhanced the resistance conferred by the well-characterized NA-N295S mutation. Functional analyses demonstrated that these HA substitutions confer distinct levels of resistance, directly linked to altered receptor-binding properties caused by changes in amino acid charge. Importantly, the HA mutations identified here are already present in globally circulating seasonal influenza H1N1 viruses and may act synergistically with established NA resistance mutations.

Results

Screening for oseltamivir resistance mutations in A(H1N1)pdm09 virus

To evaluate the variation of the influenza virus in response to oseltamivir, we conducted two independent serial passages under different drug treatments. The influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus A/California/07/2009 (abbreviated as Cal09) was passaged seven times in the presence of increasing concentrations of oseltamivir (Fig. 1a). In another group, favipiravir, a nucleoside analog used in clinical treatment28,30, was applied during the first three passages. The virus population was then passaged four additional times under increasing concentrations of oseltamivir (Fig. 1b).

a, b Schematic representation of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus A/California/07/2009 (Cal09) passaged serially with oseltamivir alone (a) or initially with favipiravir followed by oseltamivir (b). c–f Plaque-reduction assay of the first (P1) and seventh (P7) passages of virus populations derived from serial passages in the presence of oseltamivir alone (c, d) or initially with favipiravir followed by oseltamivir (e, f). Plaque assay was conducted in the absence (0 μM) or presence of low concentrations (0.1 μM) or high concentrations (160 μM) of oseltamivir. Virus populations from the serial passages were subjected to two independent plaque-reduction assays. Each dot represents the diameter (mm) of a single plaque (n = 20). g, h Sequence changes in the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins after plaque purification on the P7 virus populations displaying clear resistance at 0.1 μM oseltamivir. The P7 virus populations derived from serial passages in the presence of oseltamivir alone (g) or initially with favipiravir followed by oseltamivir (h) were used for plaque purification, and the viral genomes were sequenced using deep sequencing or Sanger sequencing. i Amino acid changes in the HA and NA proteins after virus passage in the absence of oseltamivir as controls. Virion RNA was isolated from virus passages, amplified by RT-PCR, and subjected to Sanger sequencing. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We then conducted a classic plaque-reduction assay to assess drug resistance in P1 and P7 virus populations from both groups in the absence or presence of 0.1 μM or 160 μM of oseltamivir, respectively, using plaque size as the readout (Fig. 1c–f). Compared to viruses in the absence of oseltamivir, both P1 viruses showed significantly reduced plaque diameters at 0.1 μM oseltamivir, with further reductions observed at 160 μM. Notably, P7 viruses passaged with oseltamivir alone have significantly larger plaques than those exposed to favipiravir followed by oseltamivir (Fig. 1c–f). These findings indicate that both virus groups developed resistance to oseltamivir, with stronger resistance observed in P7 viruses from the group treated exclusively with oseltamivir (Fig. 1d, f).

To accurately evaluate adaptive mutations conferring oseltamivir resistance, we performed plaque purification on the P7 virus populations displaying clear resistance at 0.1 μM oseltamivir. Plaque purification was also conducted on P1 virus populations in the absence of oseltamivir as a control. After virus amplification, RNAs from individual plaques were extracted, and the viral genomes were sequenced using deep sequencing or Sanger sequencing. Genome alignment revealed that, compared to P1 viruses, P7 viruses under oseltamivir pressure consistently harbored an HA-K130E mutation (H1 numbering; K134E in H3 numbering) with a 100% mutation rate (Fig. 1g). Additionally, 66.6% of these viruses exhibited an NA-N21S mutation (N1/N2 numbering). In P7 viruses subjected to favipiravir followed by oseltamivir treatment, 83.3% carried a HA-K130N mutation (H1 numbering; K134N in H3 numbering) (Fig. 1h). Furthermore, a HA-K142N mutation (H1 numbering; K145N in H3 numbering) was identified in two plaques. In the NA segment, 50% of the viruses had the N295S mutation, a known oseltamivir resistance marker, along with a K331T mutation (N1/N2 numbering). Additionally, one plaque virus exhibited the R293K mutation, another known marker of oseltamivir resistance. In two independent DMSO-treated controls passaged without antiviral pressure, no HA or NA mutations were detected in one Cal09 passage, while a single NA-Y66C mutation emerged in the other (Fig. 1i). These distinct outcomes likely reflect the intrinsically error-prone nature of the influenza virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase.

HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutations confer oseltamivir resistance

Interestingly, in our oseltamivir resistance screening experiments, in addition to the well-characterized NA-H275Y and NA-N295S mutations, we identified two mutations in the HA protein, HA-K130E and HA-K130N, both at residue 130. To determine their specific effects on oseltamivir resistance, we generated Cal09-WT virus and HA-K130N or HA-K130E mutant viruses using reverse genetics. Plaque-reduction assays showed that plaque diameters of the WT virus were inhibited at 0.01 μM oseltamivir (Fig. 2a, b), whereas HA-K130N mutant plaques were only reduced at 0.1 μM and were significantly inhibited at 1 μM. Strikingly, HA-K130E mutant plaques remained large even at 100 μM oseltamivir. These results suggest that both HA-K130N and HA-K130E independently confer oseltamivir resistance. Notably, Cal09-WT and both HA mutants remained high sensitivity to baloxavir, a viral polymerase inhibitor (Fig. S1a, b).

a, b Plaque-reduction assay of the A/California/07/2009 wild-type (Cal09-WT) virus and HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutants. This assay was conducted in the absence (0 μM) or presence of 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 μM oseltamivir. Recombinant viruses generated from two independent rescue experiments were subjected to plaque-reduction experiments. Each dot represents the diameter (mm) of a single plaque (n = 20). c Time course of virus replication of the Cal09-WT virus, HA-K130N, and HA-K130E mutant viruses in MDCK cells infected at an MOI of 0.001 in the absence of oseltamivir. At the indicated time points, the virus titers in the culture supernatant were determined by a plaque assay. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM from n = 2 independent biological replicate experiments. d Virus replication of the Cal09-WT virus, HA-K130N, and HA-K130E mutant viruses in MDCK cells infected at an MOI of 0.001 in the presence of oseltamivir. The virus titers in the culture supernatant at 72 h postinfection were determined by a plaque assay. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM from n = 3 independent biological replicate experiments. e–g Competitive co-infection experiments between Cal09-WT (HA-130K) and HA-K130N mutant viruses (e), Cal09-WT (HA-130K) and HA-K130E mutant viruses (f), and HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutant viruses (g). Viruses were infected in MDCK cells with an MOI of 0.01 and serially passaged in the absence and presence of 0.1 and 160 μM oseltamivir. Virion RNA was isolated, amplified by RT-PCR, and sequenced. The sequence traces of residue 130 of HA from P1 and P2 viruses are shown. The illustrations of viruses were adapted from a royalty-free vector graphic sourced from pixabay.com. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We then evaluated the replication capacity of HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutant viruses using a classical plaque assay. Fig. 2c showed that both mutations imposed a significant fitness cost, with HA-K130E causing a more severe reduction in viral fitness. Next, we examined the effect of oseltamivir on virus replication by measuring viral titers at 72 h post-infection under the same conditions as in Fig. 2c. WT virus replication was significantly inhibited at 0.1 μM oseltamivir but not at 0.01 μM (Fig. 2d). Interestingly, the HA-K130N mutant replicated efficiently at 0.01–1 μM oseltamivir, comparable to WT virus replication in the absence of oseltamivir, but sharply declined at 10 μM. In contrast, the HA-K130E mutant showed enhanced replication at 0.01–10 μM oseltamivir, with a decline only at 100 μM. Virus growth kinetics under different oseltamivir concentrations corroborated these findings (Fig. S2a–c). It should be noted that in clinical settings, the average plasma concentration of oseltamivir with the standard 75 mg twice-daily regimen is 0.33 μM33,34. These data suggest that the HA-K130N mutant retains higher growth fitness at clinically relevant oseltamivir concentrations.

To evaluate the growth dynamics of WT and the two mutant viruses, we conducted competitive co-infection experiments at equal multiplicity of infection (MOI) in the absence and presence of oseltamivir (Fig. 2e–g). In the absence of oseltamivir, WT virus replication predominated over HA-K130N virus (Fig. 2e). However, HA-K130N demonstrated a significant replication advantage at both low and high oseltamivir concentrations. In the co-infection of WT and HA-K130E viruses, WT replication was dominant in the absence and at low oseltamivir concentrations, while HA-K130E became the dominant virus at high oseltamivir concentrations (Fig. 2f). When HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutants were co-cultured, HA-K130N was dominant in the absence and at low oseltamivir concentrations. However, HA-K130E gained dominance at high oseltamivir concentration (Fig. 2g). These findings confirm that both HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutations confer oseltamivir resistance. Notably, while HA-K130E exhibits greater resistance, it also incurs a high fitness cost, similar to common oseltamivir-resistance mutations occurred in the NA.

HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutations confer cross-resistance to multiple neuraminidase inhibitors

Oseltamivir is one of several clinically approved neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs), which also include zanamivir, laninamivir, and peramivir35,36,37. To assess whether HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutations confer cross-resistance to other NAIs, we performed plaque-reduction assays using zanamivir and peramivir. These drugs were selected because zanamivir exhibits a binding mode distinct from oseltamivir, whereas peramivir closely resembles oseltamivir36. As expected, the Cal09-WT virus remained fully sensitive to both drugs (Fig. 3a–d). The HA-K130N mutation reduced susceptibility, with significant plaque inhibition observed at 0.1–1 µM. Notably, the HA-K130E mutant displayed even stronger cross-resistance, maintaining substantial plaque-forming capacity at 10 µM of either drug. This resistance profile closely parallels the oseltamivir resistance observed in these HA mutants.

a Plaque-reduction assay of the A/California/07/2009 wild-type (Cal09-WT) virus and HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutants in the presence of zanamivir. This assay was conducted in the absence (0 μM) or presence of 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 μM zanamivir. b Plaque diameters (mm) corresponding to panel (a). c Plaque-reduction assay of the Cal09-WT virus and HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutants in the presence of peramivir. This assay was performed in the absence (0 μM) or presence of 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 μM peramivir. d Plaque diameters (mm) of the viral plaque in panel (c). Recombinant viruses generated from two independent rescue experiments were subjected to plaque-reduction experiments. Each dot represents the diameter (mm) of a single plaque (n = 20). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To complement these findings, we employed a standard fluorescence-based neuraminidase inhibition assay to determine IC50 values of oseltamivir and zanamivir for the HA mutant viruses. Known oseltamivir-resistant NA mutants, NA-N295S and NA-H275Y, which do not confer zanamivir resistance, were included as controls36,38. The IC50 of oseltamivir for Cal09-WT was 0.23 nM, whereas NA-N295S alone or combined with HA-K130N increased IC50 values to 22.94 nM and 30.54 nM, representing 100-fold and 133-fold increases, respectively (Table 1). In contrast, HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutants showed IC50 values largely comparable to those of the WT virus, and none of these mutations altered the IC50 for zanamivir. These results are consistent with the expectation that conventional neuraminidase inhibition assays fail to detect resistance mechanisms arising from HA mutations.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that HA residue 130 mutations (K130N and K130E) reduce susceptibility not only to oseltamivir but also to structurally distinct NAIs such as zanamivir, highlighting the broader impact of this novel HA-mediated resistance mechanism. Importantly, resistance conferred by HA mutations is detectable in biological assays but remains undetected by conventional neuraminidase inhibition assays.

HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutations affect receptor binding affinity

To gain the structural insight of HA-K130 mutations, we analyzed the crystal structure of HA from the A/California/04/2009 virus in complexed with a human receptor analog (Fig. 4a). HA-K130 is located within the 130-loop of the receptor binding site (RBS) and is positioned near sialic acid (Fig. 4b). Notably, HA-K142, another mutation observed during favipiravir and oseltamivir treatment, is also located in the 130-loop and interacts with sialic acid via a hydrogen bond. Substituting HA-K130 with N or E introduced one or two additional positively charged groups to the amino acid side chain, respectively (Fig. 4c, d). These changes alter the charge properties of RBS, potentially affecting receptor binding affinity (Fig. 4e–g).

a Crystal structure of influenza A/California/04/2009 (Cal09) virus hemagglutinin (HA) complexed with human receptor analog (PDB ID: 4JTV). b–d Ribbon representation of structural models of HA-WT (b), HA-K130N (c), and HA-K130E (d) in complex with the human receptor. The residues 130 and 142 of HA are shown. Potential interactions between the protein and the receptors are represented by broken lines. e–g Surface representation of structural models of HA-WT (e), HA-K130N (f), and HA-K130E (g) in complex with the human receptor, colored by electrostatic potential (red negative, blue positive). The locations of the HA 130 residue are indicated by a dotted circle. h, i BIAcore plots showing binding of Cal09 HA-WT, HA-K130N, and HA-K130E to α-2,6-linked sialylglycan human (h) and α-2,3-linked sialylglycan avian (i) receptors. The HA protein of avian H5 subtype virus acts as a positive control for specific binding to α-2,3-linked sialylglycan avian receptor. 200 μM of Cal09-WT or mutant proteins and 10 μM of H5 protein, were used for kinetics analysis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To assess receptor binding affinity, we prepared recombinant HA-WT and HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutant proteins of the Cal09 virus expressed in HEK293F cells. Using surface plasmon resonance (SPR), we measured binding affinities to canonical human α-2,6 glycans and avian α-2,3 glycans receptors, with H5 subtype HA as a control for avian receptor binding (Fig. 3h, i). HA-WT exhibited a strong preference for the human receptor (response unit: 102.4), whereas HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutants showed significantly reduced affinities, with response units of 15.2 and 2.9, respectively (Fig. 3h). We further evaluated receptor interactions using a hemagglutination-elution (HAE) assay with guinea pig red blood cells (RBCs) in the absence and presence of oseltamivir21,22. The HA-K130E mutant virus was excluded due to its low HA titer. The HA-K130N mutation resulted in a 10-fold increase in resistance to oseltamivir in the HAE assay (Fig. S3). Combining SPR and HAE results, we conclude that the HA-K130 mutations confer oseltamivir resistance by reducing receptor binding affinity.

HA-K130N has gradually become dominant among globally circulating human H1 strains since 2019

To assess the natural variation at residue 130 of the HA protein, we analyzed H1 subtype virus sequences in the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) database, covering the period from 2015 to May 2, 2024. Our analysis revealed that prior to 2019, HA-130K was the predominant residue among H1 viruses, with lower frequencies of HA-130R and HA-130-deletion mutations. However, a significant rise in the frequency of the HA-130N mutation has been observed, with a gradual transition from HA-130K dominance to HA-130N dominance between 2019 and 2024 (Fig. 5a). In contrast, H1 virus sequences isolated from swine predominantly exhibit HA-130K, HA-130R, and HA-130-deletion mutations (Fig. 5b). For avian H1 viruses, residue 130 is almost exclusively HA-130K in all available 1074 sequences as of May 2, 2024.

a Polymorphic signatures at HA residue 130 of all H1 subtype viruses from 2015 to 2024. b Polymorphic signatures at HA residue 130 of swine H1 subtype viruses from 2019 to 2024 and HA residue 130 of all available avian H1 subtype viruses. c Phylogenetic analysis of the HA gene of the currently dominant lineage circulating among human H1 isolates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Moreover, phylogenetic analysis revealed that the HA-K130N mutation is strongly associated with specific evolutionary clades, including clade 6B.1 A.5b and the more recently identified clade 6B.1 A.5a.2a.1. Notably, clade 6B.1 A.5a.2a.1 represents the currently dominant lineage circulating among human H1 isolates, including the current prevalent circulating H1 strains (Fig. 5c). This association suggests that the HA-K130N variation has undergone selective pressure, likely driven by its adaptive advantage in human hosts. These findings underscore the critical role of the HA-K130N mutation in shaping the evolution of H1 viruses. Importantly, the close linkage of this mutation to human drug resistance highlights its potential impact on antiviral treatment strategies and public health outcomes.

To evaluate whether circulating H1N1 strains carrying the HA-K130N variant exhibit oseltamivir resistance, we tested two recently isolated A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses harboring this mutation: A/Fujian-Licheng/SWL1661/2023 and A/Sichuan-Shunqing/SWL11211/2023. Viral replication was assessed by measuring 72 h post-infection under increasing oseltamivir concentrations. Both viruses remained oseltamivir-sensitive, showing a clear, concentration-dependent reduction in viral titers (Fig. S4a, b). The absence of resistance suggests that compensatory substitutions in HA or NA may counteract the resistance phenotype typically associated with HA-K130N. In line with recent analyses of H1N1 HA evolution39,40, our sequence analysis of HAs in these circulating strain isolates revealed multiple additional substitutions (Fig. S5), including HA-N156K (150-loop), HA-A186T and HA-Q189E (190-helix), and HA-E224A (220-loop). The co-occurrence of these mutations with HA-K130N supports the hypothesis that compensatory evolution has accompanied this mutation, preserving both viral fitness and oseltamivir sensitivity.

HA-K130N synergizes with NA-N295S to enhance oseltamivir resistance

In our initial serial passaging experiments, the HA-K130E mutation occurred both independently and in combination with NA-N21S. To evaluate potential synergistic or compensatory effects, we rescued viruses carrying HA-K130E or NA-N21S alone, as well as the combination. Plaque-reduction assays demonstrated that the NA-N21S alone did not confer oseltamivir resistance, nor did it enhance resistance in the HA-K130E background (Fig. 6a, b). Viral replication kinetics further confirmed that NA-N21S had no measurable impact on viral replication (Fig. S6a), suggesting that this substitution likely represents a random mutation acquired during passaging.

a Plaque-reduction assay of the A/California/07/2009 wild-type (Cal09-WT) virus, HA-K130E, NA-N21S, and combined HA-K130E and NA-N21S mutants. This assay was conducted in the absence (0 μM) or presence of 0.1 μM or 160 μM oseltamivir. b Plaque diameters (mm) corresponding to panel (a). c Plaque-reduction assay of the A/California/07/2009 wild-type (Cal09-WT) virus, HA-K130N, NA-N295S, and combined HA-K130N and NA-N295S mutants. This assay was conducted in the absence (0 μM) or presence of 0.1 μM or 10 μM of oseltamivir. d Plaque diameters (mm) of the viral plaque in panel (c). Recombinant viruses generated from two independent rescue experiments were subjected to plaque-reduction experiments. Each dot represents the diameter (mm) of a single plaque (n = 20). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The HA-K130N mutant virus population was accompanied by known resistance-associated NA mutations, including NA-N295S and NA-R293K, as well as the previously uncharacterized NA-K331T (Fig. 1h). To further investigate these functional interactions, we rescued each NA mutant individually and in combination with the HA-K130N. Plaque-reduction assay showed that NA-N295S alone tolerated oseltamivir concentrations of 0.01 to 0.1 μM, with inhibition at 1 μM, comparable to HA-K130N alone (Fig. 6c, d). Remarkably, the combination of HA-K130N and NA-N295S resulted in significantly enhanced resistance, as evidenced by larger plaque diameters even at 10 μM oseltamivir.

In contrast, NA-K331T had minimal effects on drug resistance in plaque-reduction assays (Fig. 6c, d) and conferred only a minor growth advantage in viral replication kinetics assays (Fig. S6b, c), consistent with a stochastic emergence during passaging. NA-R293K, both alone and combined with HA-K130N, conferred strong oseltamivir resistance (Fig. S7a, b), consistent with previous reports that this residue is part of a critical tri-arginyl cluster involved in substrate binding and catalysis, and that NA-R293K imparts strong resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir36,41,42. Taken together, these data suggest that HA-K130N synergizes with NA-N295S to enhance oseltamivir resistance. Notably, sequence surveillance identified five circulating strains since 2020 carrying both HA-K130N and NA-N295S mutations (Tables S1, S2).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that prolonged treatment with the neuraminidase inhibitor (NAI) oseltamivir can select for mutations at HA residue 130, which alone confer resistance to oseltamivir and cross-resistance to other NAIs, including zanamivir and peramivir, in an A(H1N1)pdm09 virus. Structural analysis revealed that HA-K130N and HA-K130E alter the charge properties of the HA receptor binding site (RBS), directly affecting receptor engagement. Despite the associated fitness cost, both HA-K130N and HA-K130E mutant viruses maintain high replication levels in the presence of oseltamivir. Notably, since 2019, the proportion of H1 subtype influenza viruses carrying HA-K130N has gradually increased, eventually becoming dominant in the human population. Furthermore, we demonstrate that HA-K130N synergizes with the known neuraminidase resistance mutation NA-N295S, greatly enhancing the virus resistance to oseltamivir.

Prolonged virus shedding is commonly observed in elderly and immunocompromised patients across a wide range of viral infections, including influenza virus43, SARS-CoV-244, and respiratory syncytial virus45. These patients are typically treated with a combination of antivirals over extended periods, which facilitates the emergence of antiviral-resistant mutations. In this study, we simulated prolonged antiviral pressure by serially viral passaging and observed that a single mutation at HA residue 130 can confer resistance to NAIs. In contrast, previously reported oseltamivir-resistant mutations typically occur in NA, often imposing a fitness cost that is mitigated by secondary “permissive” mutations14,46. HA mutations conferring NAI resistance have also been reported, though they often co-occur with NA mutations, suggesting a compensatory role22,25,32,47,48. For instance, in an immunocompromised child infected with the influenza B virus, prolonged zanamivir treatment led to a mutation in the HA receptor-binding site alongside a mutation in the NA active site, conferring a growth advantage in treated animals32. Similarly, in immunocompromised mice infected with influenza A virus, one variant carrying both NA-R293K and HA-G225E showed high-level oseltamivir resistance25, likely through modulation of the HA-NA functional balance between viral attachment and release5,21,47,49. In this study, a similar combination of HA-K130N and NA-N295S mutations was observed. However, the HA-K130E mutant virus, even in the absence of known NA resistance mutations, exhibited significant oseltamivir resistance. Although the HA-K130E imposes a high fitness cost, compensatory mutations could potentially emerge over time. Importantly, the HA-K130E mutant virus maintains high replication capability in the presence of elevated oseltamivir concentrations, highlighting the critical role of HA residue 130 in modulating oseltamivir resistance.

Previous studies have reported that the high incidence of influenza viruses is largely attributable to their ability to rapidly escape immune responses induced by prior infections or vaccinations50. This immune escape is primarily driven by the accumulation of mutations in the viral surface glycoprotein HA, with a lower frequency of mutations in NA. This process, known as antigenic drift, underlies the rapid evolution of influenza viruses51. A similar mechanism contributes to the development of antiviral resistance: treatment with NAIs may select for HA mutations that alter receptor-binding properties, facilitating viral escape from natural or vaccine-induced immunity52. Polymorphic variations at the HA residue 130 have been identified in H1N1 influenza viruses39,50,53. Since 1918, the HA residue 130 has been alternatively occupied by lysine (K) or arginine (R) in most H1N1 strains, and in some strains, the residue is absent53. Interestingly, since 2019, the HA-K130N mutation has become overwhelmingly dominant in currently circulating H1N1 strains. In our study, the HA-K130N mutation alone conferred mild oseltamivir resistance; however, when combined with NA-N295S, resistance was markedly enhanced. Notably, two virus strains isolated in 2023 carrying HA-130N remained sensitive to oseltamivir, likely due to compensatory mutations elsewhere in HA or NA. The global detection of HA-K130N likely reflects a combination of stochastic emergence and regionally variable selective pressures, rather than a direct consequence of widespread antiviral use. Selective pressures imposed by NAIs and acquired immunity may act together to accelerate the emergence of compensatory HA mutations that optimize receptor specificity, antigenicity, and functional compatibility with NA52.

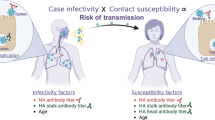

In summary, efficient influenza virus infections rely on a finely tuned balance between HA and NA functions (Fig. 7). Oseltamivir inhibits NA activity by binding its active site, disrupting this balance and suppressing viral replication10. Resistance typically arises through NA mutations that reduce drug binding and restore HA-NA balance. Here, we provide the evidence that oseltamivir-resistant mutations also arise in HA alone, reducing receptor binding to restore functional balance and facilitate effective infection (Fig. 7). Notably, HA resistance mutations can synergize with NA-N295S, further enhancing antiviral resistance (Fig. 7). Our findings underscore the importance of ongoing surveillance for oseltamivir resistance in influenza viruses, particularly with the rising prevalence of HA-K130N mutation. Given that this mutation can confer resistance alone and in combination with other resistance mutations, timely monitoring of HA mutations is essential for effective antiviral strategies. Collectively, our study demonstrates that mutations in HA are closely associated with neuraminidase inhibitor resistance and underscores the importance of including HA in resistance surveillance of circulating epidemic H1N1 viruses.

In the absence of oseltamivir, the binding of viral hemagglutinin (HA) and the cleavage by neuraminidase (NA) of wild-type (WT) virus are in balance, allowing the virus to be effectively released. When oseltamivir is present, the balance between HA binding and NA cleavage is disrupted due to inhibition of NA cleavage activity, resulting in the inability of the virus to be released. One of the mechanisms by which influenza viruses develop resistance to oseltamivir is mutations in the NA protein, such as H275Y, R293K, and N295S. These mutations reduce oseltamivir binding to the virus, restoring the NA cleavage activity and allowing the virus to be released. Conversely, mutations in the HA protein identified in this study, such as HA-K130N or HA-K130E, can reduce the binding affinity of HA to the receptor, re-establishing the balance between HA binding and NA cleavage, which ultimately allows the virus to be released. More importantly, the co-existence of the HA-K130N mutation with the documented NA-N295S mutation can enhance resistance to oseltamivir. The illustrations of viruses were adapted from a royalty-free vector graphic sourced from pixabay.com.

Methods

Cells

HEK-293T (ATCC, CRL-3216) and MDCK (ATCC, CCL-34) cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C.

Virus

The influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus A/California/07/2009 (Cal09) used in this research was described previously54. All laboratory procedures involving live viruses were performed in a biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) facility. The influenza viruses were cultured and propagated in MDCK cells.

Selection of oseltamivir-resistant variants

The initial passage of the A/California/07/2009 virus was conducted by infecting MDCK cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001 in the presence of 0.01 μM oseltamivir. Subsequently, the concentration of oseltamivir was gradually increased to 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 μM. For another group, favipiravir was introduced to enhance viral mutability during the first three passages. In this group, the first three passages were performed in the presence of favipiravir at concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 μM, followed by four additional passages incorporating oseltamivir at concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 μM. The MOI for all viral infections was maintained at 0.001–0.01. Viral supernatants from each generation of infection were collected and analyzed for drug resistance.

Generation and characterization of recombinant viruses

The influenza A/California/07/2009 recombinant virus was generated by pHW-2000 eight-plasmid reverse genetics55. The mutations were introduced into the HA or NA plasmids using the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (NEB). HEK-293T cells mixed with MDCK cells were co-transfected with the eight pHW-2000 plasmids derived from Cal09 (WT or mutant) using Lipofectamine 2000 for generating recombinant viruses. After 24 h, the supernatants were removed and cells were incubated in infection maintenance medium (DMEM containing 0.5% FBS and 0.5 μg/mL tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich)) for 48 h at 37 °C. The supernatants were collected, and the concentration of infectious viral particles (PFU per milliliter) was determined by a plaque assay in MDCK cells.

Plaque-reduction assays and plaque selection of resistant phenotypes

Different generations or variants of viruses were formed plaques in MDCK cells under an overlay of 1% agarose with 0.15% BSA, 0.5 μg/mL TPCK-treated trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich), and various concentrations or dosages of antivirals. At 72–96 h post-infection, the cells were fixed with 4% formalin (Sigma-Aldrich) and stained with 1% crystal violet. The plaque diameters were measured by ImageJ software through a standardized method. For plaque selection of resistant phenotypes, at 72–96 h post-infection, several large plaques of specific viruses were harvested to infect MDCK cells for propagation of viruses.

Virus yield reduction assay

To determine the relative sensitivities of the viruses to oseltamivir, the virus yield reduction assay was performed. MDCK cells were infected with the virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001 at room temperature for 1 h. The inoculum was removed and the cells were incubated in infection maintenance medium containing 0.01–100 μM of oseltamivir for 72 h at 37 °C. Virus yields were determined as the number of PFU/ml in MDCK cells.

Genomic sequencing of the viral competition experiment

MDCK cells were infected with mixed viruses (at a ratio of 1:1) at an MOI of 0.01 in infection maintenance medium for 48 h. The supernatants were collected and used for the next infection in MDCK cells at an MOI of 0.001–0.01. For sequencing of the HA segment, viral RNA was extracted using TRIzol LS reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and reverse transcribed using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen) with a universal influenza A virus reverse transcription (RT) primer56,57. The RT products were then amplified by PCR using primers (HA forward primer, 5’-CGTCTCGGGGAGCAAAAGCAGGGGAAAACAA-3’; HA reverse primer, 5’-CGTCTCTTATTAGTAGAAACAAGGGTGTTTTTCTC-3’). The PCR products were purified and sequenced by Sanger sequencing (Beijing Tsingke Biotech, China).

Whole genome sequencing

This technique has been previously described elsewhere30. Viral RNA was amplified using multiple RT-PCR strategies, which were offered by Ion AmpliSeq FluAB Research Panel (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA) for library preparation. Samples were sequenced using the Ion GeneStudioTM S5 Series Sequencer platform. Next-generation data was mapped to the influenza virus genome using BWA-MEM 0.7.5, and variants were identified by bcftools mpileup 1.15. The data were filtered by the parameters QUAL ≥ 20, DP ≥ 20, and variant type = SNP.

Viral replication kinetics

The Cal09 wild-type or mutant viruses infected MDCK cells at an MOI of 0.001 in DMEM supplemented with 0.5% FBS. At 24, 48, 72, and 96 h post-infection, the supernatants were collected. The virus titers were determined by plaque assay in MDCK cells.

Neuraminidase inhibition assay

The susceptibility of viruses to NAIs (oseltamivir and zanamivir) was determined using a fluorescence-based neuraminidase inhibition assay. This method quantifies NA activity by measuring the fluorescence of 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MU) released upon enzymatic cleavage of the substrate 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-D-N-acetylneuraminic acid (MUNANA). The assay was performed using the NA-FluorTM Influenza Neuraminidase Assay Kit (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) as previously described58.

Protein expression and purification

The pCAGGS-Cal09-HA-WT, pCAGGS-Cal09-HA-K130N, or pCAGGS-Cal09-HA-K130E were expressed in HEK293F cells. Each 500 mL cells were transfected with 500 μg plasmid and 2 mg polyethyleneimine (PEI). After 16–22 h post transfection, 3 g glucose and 25 ml supplement were added to the culture system. Cell culture supernatants were collected after a 6-day transfection. The HA proteins were purified using His-Trap HP columns (Cytiva), followed by the SuperdexTM 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (Cytiva). The HA proteins produced by HEK293F cells were used for SPR assay and stored in PBST buffer (PBS containing 0.005% Tween 20).

SPR measurements and affinity analysis

The SPR measurements were described previously59. The affinities and kinetics of HAs binding to α-2,6 and α-2,3 receptor analogs were analyzed on the BIAcore 3000 machine at 25 °C with streptavidin chips (SA chip, Cytiva). PBST buffer was used for the running buffer. The 6’S-Di-LN and 3’S-Di-LN, two biotinylated sialic acid receptor analogs, were immobilized on the chip and the blank channel as a negative control. 10 μM or 200 μM HAs were used for kinetics analysis. Sensorgrams were fitted globally with the BIAcore 3 K analysis software (BIAevaluation version 4.1), using the 1:1 Langmuir binding mode.

Hemagglutination and hemagglutination-elution assays

For hemagglutination assays60, the procedure involved serially diluting the viruses (25 μl) with 25 μl of PBS in V-bottom microtiter plates. Subsequently, 2% guinea pig erythrocytes (purchased from Beijing Hu Chi Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were added to each well. Then, the plates were incubated at 4 °C for 45 min.

For hemagglutination-elution assays21,22, serial tenfold dilutions of drug starting from 100 μM for oseltamivir were added in V-bottom microtiter plates first, 4 hemagglutinating units (HAU) of virus were then added to each well (one well contained virus without drug, which acted as the elution control). The drugs and viruses were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Afterwards, erythrocytes were added, and the plates were incubated at 4 °C for 45 min. The plated were photocopied immediately and then incubated at 37 °C to allow elution of the viruses. Until the elution was followed by the appearance of pelleted erythrocytes, the plates were photocopied again, and recorded the drug concentration at which virus was eluted.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All relevant data are available within the manuscript, Figures, and its Supporting Information files. The assembly genome sequences have been deposited in the GenBase in National Genomics Data Center under accession number from C_AA121817.1 to C_AA121888.1 that are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/genbase. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Gilbertson, B. & Subbarao, K. What have we learned by resurrecting the 1918 influenza virus? Annu Rev. Virol. 10, 25–47 (2023).

Gamblin, S. J. & Skehel, J. J. Influenza hemagglutinin and neuraminidase membrane glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 28403–28409 (2010).

Gamblin, S. J. et al. Hemagglutinin structure and activities. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a038638 (2021).

McAuley, J. L., Gilbertson, B. P., Trifkovic, S., Brown, L. E. & McKimm-Breschkin, J. L. Influenza virus neuraminidase structure and functions. Front. Microbiol. 10, 39 (2019).

de Vries, E., Du, W., Guo, H. & de Haan, C. A. M. Influenza a virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase-receptor balance: preserving virus motility. Trends Microbiol. 28, 57–67 (2020).

Kaverin, N. V. et al. Intergenic HA-NA interactions in influenza A virus: postreassortment substitutions of charged amino acids in the hemagglutinin of different subtypes. Virus Res. 66, 123–129 (2000).

Kaverin, N. V. et al. Postreassortment changes in influenza A virus hemagglutinin restoring HA-NA functional match. Virology 244, 315–321 (1998).

Wagner, R., Matrosovich, M. & Klenk, H. D. Functional balance between haemagglutinin and neuraminidase in influenza virus infections. Rev. Med. Virol. 12, 159–166 (2002).

Mitnaul, L. J. et al. Balanced hemagglutinin and neuraminidase activities are critical for efficient replication of influenza A virus. J. Virol. 74, 6015–6020 (2000).

Lakdawala, S., Koszalka, P., Subbarao, K. & Baz, M. Preclinical and clinical developments for combination treatment of influenza. PLOS Pathog. 18, e1010481 (2022).

Lee, N. & Hurt, A. C. Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in influenza: a clinical perspective. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 31, 520–526 (2018).

Moscona, A. Global transmission of oseltamivir-resistant influenza. N. Engl. J. Med 360, 953–956 (2009).

Leung, R. C., Ip, J. D., Chen, L. L., Chan, W. M. & To, K. K. Global emergence of neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses with I223V and S247N mutations: implications for antiviral resistance monitoring. Lancet Microbe https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(24)00037-5 (2024).

Bloom, J. D., Gong, L. I. & Baltimore, D. Permissive secondary mutations enable the evolution of influenza oseltamivir resistance. Science 328, 1272–1275 (2010).

Kiso, M. et al. Resistant influenza A viruses in children treated with oseltamivir: descriptive study. Lancet 364, 759–765 (2004).

Baz, M., Abed, Y. & Boivin, G. Characterization of drug-resistant recombinant influenza A/H1N1 viruses selected in vitro with peramivir and zanamivir. Antivir. Res 74, 159–162 (2007).

Tisdale, M. Monitoring of viral susceptibility: new challenges with the development of influenza NA inhibitors. Rev. Med. Virol. 10, 45–55 (2000).

Dharan, N. J. et al. Infections with oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1N1) virus in the United States. JAMA 301, 1034–1041 (2009).

Ciancio, B. C. et al. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1N1) viruses detected in Europe during season 2007-8 had epidemiologic and clinical characteristics similar to co-circulating susceptible A(H1N1) viruses. Euro Surveill. 14, 19412 (2009).

Holmes, E. C. Virology. Helping the resistance. Science 328, 1243–1244 (2010).

McKimm-Breschkin, J. L. et al. Generation and characterization of variants of NWS/G70C influenza virus after in vitro passage in 4-amino-Neu5Ac2en and 4-guanidino-Neu5Ac2en. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40, 40–46 (1996).

Samson, M. et al. Characterization of drug-resistant influenza virus A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) variants selected in vitro with laninamivir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 5220–5228 (2014).

Cohen-Daniel, L. et al. Emergence of oseltamivir-resistant influenza A/H3N2 virus with altered hemagglutination pattern in a hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipient. J. Clin. Virol. 44, 138–140 (2009).

Blick, T. J. et al. The interaction of neuraminidase and hemagglutinin mutations in influenza virus in resistance to 4-guanidino-Neu5Ac2en. Virology 246, 95–103 (1998).

Ison, M. G., Mishin, V. P., Braciale, T. J., Hayden, F. G. & Gubareva, L. V. Comparative activities of oseltamivir and A-322278 in immunocompetent and immunocompromised murine models of influenza virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 193, 765–772 (2006).

Furuta, Y. et al. In vitro and in vivo activities of anti-influenza virus compound T-705. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 977–981 (2002).

Furuta, Y., Komeno, T. & Nakamura, T. Favipiravir (T-705), a broad-spectrum inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase. Proc. Jpn Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 93, 449–463 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Comparative effectiveness of combined favipiravir and oseltamivir therapy versus oseltamivir monotherapy in critically ill patients with influenza virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 221, 1688–1698 (2020).

Baranovich, T. et al. T-705 (favipiravir) induces lethal mutagenesis in influenza A H1N1 viruses in vitro. J. Virol. 87, 3741–3751 (2013).

Mu, S. et al. The combined effect of oseltamivir and favipiravir on influenza A virus evolution in patients hospitalized with severe influenza. Antivir. Res 216, 105657 (2023).

Memoli, M. J. et al. The natural history of influenza infection in the severely immunocompromised vs nonimmunocompromised hosts. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 214–224 (2014).

Gubareva, L. V., Matrosovich, M. N., Brenner, M. K., Bethell, R. C. & Webster, R. G. Evidence for zanamivir resistance in an immunocompromised child infected with influenza B virus. J. Infect. Dis. 178, 1257–1262 (1998).

He, G., Massarella, J. & Ward, P. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the prodrug oseltamivir and its active metabolite Ro 64-0802. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 37, 471–484 (1999).

Davies, B. E. Pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir: an oral antiviral for the treatment and prophylaxis of influenza in diverse populations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65, ii5–ii10 (2010).

McKimm-Breschkin, J. L., Rootes, C., Mohr, P. G., Barrett, S. & Streltsov, V. A. In vitro passaging of a pandemic H1N1/09 virus selects for viruses with neuraminidase mutations conferring high-level resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir, but not to zanamivir. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 1874–1883 (2012).

Bai, Y., Jones, J. C., Wong, S. S. & Zanin, M. Antivirals targeting the surface glycoproteins of influenza virus: mechanisms of action and resistance. Viruses https://doi.org/10.3390/v13040624 (2021).

Lew, W., Chen, X. & Kim, C. U. Discovery and development of GS 4104 (oseltamivir): an orally active influenza neuraminidase inhibitor. Curr. Med Chem. 7, 663–672 (2000).

Tamiflu (oseltamivir phosphate) tablet [package insert]. In: South San Francisco, CA. Roche Laboratories Inc. 1999 (approved), https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/021087s071,021246s054lbl.pdf (2019).

Lourenco, J., Zinad, H., Kempton, J. & Gupta, S. Characteristics of epitopes of limited variability on the head of influenza H1 haemagglutinin. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.30.591841 (2024).

Decker, C. H., Rapier-Sharman, N. & Pickett, B. E. Mutation in hemagglutinin antigenic sites in influenza A pH1N1 viruses from 2015–2019 in the United States, Mountain West, Europe, and the Northern Hemisphere. Genes (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13050909 (2022).

McKimm-Breschkin, J. L. et al. Mutations in a conserved residue in the influenza virus neuraminidase active site decrease sensitivity to Neu5Ac2en-derived inhibitors. J. Virol. 72, 2456–2462 (1998).

Gubareva, L. V. et al. Drug susceptibility evaluation of an influenza A(H7N9) virus by analyzing recombinant neuraminidase proteins. J. Infect. Dis. 216, S566–S574 (2017).

Weinstock, D. M., Gubareva, L. V. & Zuccotti, G. Prolonged shedding of multidrug-resistant influenza A virus in an immunocompromised patient. N. Engl. J. Med 348, 867–868 (2003).

Nakajima, Y. et al. Prolonged viral shedding of SARS-CoV-2 in an immunocompromised patient. J. Infect. Chemother. 27, 387–389 (2021).

Cheng, F. W., Lee, V., Shing, M. M. & Li, C. K. Prolonged shedding of respiratory syncytial virus in immunocompromised children: implication for hospital infection control. J. Hosp. Infect. 70, 383–385 (2008).

Baek, Y. H. et al. Profiling and characterization of influenza virus N1 strains potentially resistant to multiple neuraminidase inhibitors. J. Virol. 89, 287–299 (2015).

Tang, J. et al. R229I substitution from oseltamivir induction in the HA1 region significantly increased the fitness of a H7N9 virus bearing NA 292K. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 13, 2373314 (2024).

Gubareva, L. V., Kaiser, L., Matrosovich, M. N., Soo-Hoo, Y. & Hayden, F. G. Selection of influenza virus mutants in experimentally infected volunteers treated with oseltamivir. J. Infect. Dis. 183, 523–531 (2001).

Du, R. et al. Revisiting the influenza A virus life cycle from a perspective of genome balance. Virol. Sin. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virs.2022.10.005 (2022).

McDonald, N. J., Smith, C. B. & Cox, N. J. Antigenic drift in the evolution of H1N1 influenza A viruses resulting from deletion of a single amino acid in the haemagglutinin gene. J. Gen. Virol. 88, 3209–3213 (2007).

Petrova, V. N. & Russell, C. A. The evolution of seasonal influenza viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 47–60 (2018).

Ilyushina, N. A. et al. Influenza A virus hemagglutinin mutations associated with the use of neuraminidase inhibitors correlate with decreased inhibition by anti-influenza antibodies. Virol. J. 16, 149 (2019).

Kim, J. I. et al. Genetic requirement for hemagglutinin glycosylation and its implications for influenza A H1N1 virus evolution. J. Virol. 87, 7539–7549 (2013).

Yu, J. et al. Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus causes abortive infection of primary human T cells. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 11, 1191–1204 (2022).

Hoffmann, E., Neumann, G., Kawaoka, Y., Hobom, G. & Webster, R. G. A DNA transfection system for the generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6108–6113 (2000).

Pan, M. et al. The hierarchical sequence requirements of the H1 subtype-specific noncoding regions of influenza A virus. Microbiol Spectr. 10, e0315322 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Twenty natural amino acid substitutions screening at the last residue 121 of influenza A virus NS2 protein reveals the critical role of NS2 in promoting virus genome replication by coordinating with viral polymerase. J. Virol. 98, e0116623 (2024).

Okomo-Adhiambo, M. et al. Neuraminidase inhibitor susceptibility surveillance of influenza viruses circulating worldwide during the 2011 Southern Hemisphere season. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 7, 645–658 (2013).

Zhang, W. et al. Molecular basis of the receptor binding specificity switch of the hemagglutinins from both the 1918 and 2009 pandemic influenza A viruses by a D225G substitution. J. Virol. 87, 5949–5958 (2013).

Organization, W. H. Manual for the laboratory diagnosis and virological surveillance of influenza. WHO Global Influenza Surveillance Network. (2011).

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dayan Wang and Dr. Weijuan Huang in the National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, for their work on the study of seasonal influenza viruses and the assessment of drug resistance activity. We thank Dr. Wei Zhang from the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for her assistance in SPR measurements. We thank Lizhe Hong in China-Japan Friendship Hospital for help with sample collection and sequencing data processing. This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFF1203200 to T.D.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82472248 to T.D., 82341113 to X.H.Z., and 32400123 to L.Z.), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (L242116 to T.D.), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20240813112504007 and JCYJ20250604180053068 to L.Z.), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M753454 to L.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.D., B.C., X.Z., and L.Z. conceived the study. L.Z., Y.S., Y.Z.C., S.D., Y.T.C., Q.W., S.M., and X.L. conducted biologic experiments. L.Z., X.Z., and Q.Y. performed bioinformatic analyses. L.Z. Y.S., X.Z., and T.D. analyzed the results. T.D., B.C., X.Z., and L.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in the discussion and manuscript editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Min-Suk Song and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Shao, Y., Zou, X. et al. A primary oseltamivir-resistant mutation in influenza hemagglutinin and its implications for antiviral resistance surveillance. Nat Commun 16, 11442 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66307-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66307-5