Abstract

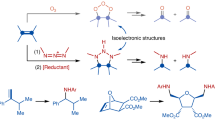

Carbanions are an important class of reactive species used as nucleophiles in C-C bond-forming reactions. Such reactive carbanions are generated by deprotonating relatively acidic C-H bonds using strong bases like sodium/potassium hydroxides or amides. Lochmann-Schlosser base, consisting of a mixture of alkyl lithium reagents and heavier alkali metal alkoxides, is widely used for the metalation of organic compounds via the deprotonation of weakly acidic C-H bond. The aggregation of alkoxides makes it challenging to understand the course of the reaction, demanding the consideration of molecular compounds as alternatives to sodium/potassium alkoxides. Here, we demonstrate the development of new organosodium reagents using molecular compounds as alternatives to oligomeric sodium/potassium alkoxides. Sodium tris(3,5-dimethylpyrazolyl)borate, along with mesityllithium in the presence of tris[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]amine (Me6TREN) deprotonates benzylic C-H bonds. The resulting carbanions generated in the reaction mixtures are trapped as [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2C6H3(3,5-CH3)]+, [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2Ph]+ and [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2C6H4(3-CH3)]+, which represent distinct examples of structurally characterised sodium benzyl cations. Preliminary reactivity studies on [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2Ph]+ indicate that it functions as an efficient alkylating reagent. Further, [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2Ph]+ is used to investigate the catalytic reduction of olefins in the presence of PhSiH3. Computational investigations on the catalytic hydrosilylative reduction infer that the reaction is mediated by a hypercoordinate hydridosilyl anion stabilised across two sodium centres. These investigations lead to new prospects in organoalkali metal chemistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Group 1 organometallic compounds are of importance in synthesis, primarily due to their utility and efficacy in facilitating carbon–carbon bond-forming reactions1. Among group 1 organometallic compounds, organolithium reagents are widely studied2. This increased interest is a result of the intriguing combination of their Brønsted basicity and solubility of organolithium compounds in organic solvents, in contrast to other organoalkali metal compounds3. The highly reactive sodium–carbon bonds in alkyl and aryl sodium reagents confer stronger Brønsted basicity, often exceeding the reactivity of analogous organolithium compounds4. While the first organosodium reagent was reported by James Alfred Wanklyn in the 1850s, investigations on the structural and reactivity aspects were hampered due to the associated synthetic difficulties5,6. Early synthesis of organosodium compounds relied on the use of toxic organomercury compounds or the direct metalation of alkyl halides, stalling progress in this field5,7. In recent years, however, there has been increasing interest in investigating organosodium complexes driven by a push towards sustainable alternatives to organolithium compounds4,8. In this context, the structural characterisation of alkyl sodium complexes is pivotal for elucidating their bonding interactions and reactivity profiles.

Schlosser and Lochmann utilised a mixture of nBuLi and tBuOM (M = Na, K) to generate a highly reactive Brønsted basic system that can deprotonate weakly acidic hydrocarbons, thus facilitating their metalation9,10,11. The mixture of nBuLi and tBuONa was thought to undergo a metathesis reaction, producing sodium alkyl—a theory confirmed by Schleyer in 1985 by trapping nBuNa in solution using N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA)12. While there are some reports on in situ generated alkyl sodium compounds for alkyl transfer, the structural nuances of these reagents are largely unexplored13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Employing a mixture of nBuLi/tBuONa, Mulvey and co-workers synthesised the first monomeric sodium benzyl complexes20,21. In 2021, Strohmann introduced the synthesis of THF-solvated polymeric sodium benzyl complex, [(PhCH₂Na)(THF)₂]∞, while Hevia and co-workers accomplished a gram-scale synthesis of nBuNa22,23. [Na(CH2SiMe3)(Me6Tren)] was reported individually and in parallel by Lu and Hevia in 202324,25. Most of these reports highlight the effective use of the nBuLi/tBuONa mixture for its exceptional efficiency as a deprotonating agent20,21,22,23,24,25. However, alkali metal alkoxides employed in this mixture have tendency to form aggregates posing synthetic challenges26,27,28. The potential of discrete, monomeric molecular compounds as an alternative to alkali metal alkoxides remains largely untapped. In this work, we demonstrate the use of sodium tris(3,5-dimethylpyrazolyl)borate as an alternative to sodium alkoxide, along with mesityllithium, to get a highly reactive sodium aryl compound that can deprotonate weakly acidic C-H bonds. The cationic sodium benzyl complexes isolated from the reaction mixtures represent unique examples of binuclear organoalkali compounds, showing remarkable reactivity.

Results and Discussion

To explore molecular compounds as alternatives to sodium alkoxides for generating carbanions of high Brønsted basicity, we considered the tri-coordinated sodium tris(3,5-dimethylpyrazolyl)borate (TpMe2Na), 1. While 1 has been widely used as a precursor in synthesising p-, d-, and f-block coordination and organometallic compounds, its reactivity with alkali metal compounds is rarely explored29,30,31. Working towards this end, we isolated 1 as an N-heterocyclic carbene adduct 2 (see Fig. 1). The X-ray structure of 2 reveals a long Na―C distance of 2.601(4) Å, within the sum of van der Waals radii of the sodium and the carbon atoms (see Fig. 1). 2 was further characterised by NMR spectroscopy and elemental analysis.

a Synthesis of 2 and 3. b Solid state structures of 2 and 3 represented with ellipsoids at 35% probability level. For clarity, the hydrogen atoms in the structures are omitted. Selected bong distances (Å) in 2: Na1―N1 2.394(3), Na1―N2 2.387(4), Na1―N3 2.451(3) Na1―C27 2.601(4); Selected distances (Å) in 3: Na1―N1 2.475(2), Na1―N2 2.406(2), Na2―N1 2.459(2), Na2―N2 2.433(2), Na1―C34 2.702(2), Na2―C13 2.692(2).

Having obtained 2, we set out to explore its reactivity in transmetalation reaction involving lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (LiN(SiMe3)2) (see Fig. 1) to gain insight into the metal exchange processes. The reaction between 2 and LiN(SiMe3)2 was analysed by 1H NMR spectroscopy, which indicated a significant shift in the TpMe2 proton signals compared to NaTpMe2 (see Supplementary Fig. 7). This reaction resulted in the formation of [(NHC)NaN(SiMe3)2]2 (NHC = 1,3-dimesitylimidazol-2-ylidene) (3) along with Li2(TpMe2)2 (4) as a secondary product (see Fig. 1). Compounds 3 and 4 were separated by fractional crystallisation, and their identities were confirmed by NMR spectroscopy. A single crystal X-ray diffraction experiment established the dimeric structure of 3 in the solid state (see Fig. 1).

The metal exchange process observed in the reaction between 2 and LiN(SiMe3)2 provides a possibility to employ 1 as one of the reagents along with organolithium compounds to generate reactive organosodium compounds. Hence, we investigated the metal exchange between 1 and mesityllithium in n-hexane (see Fig. 2). However, this reaction yielded a white precipitate whose characterisation was unsuccessful using direct methods. The reaction was repeated in C6D6 and monitored using NMR spectroscopy. A single peak at δ 3.43 ppm in the 7Li NMR spectrum, corroborating the formation of 4 confirms the Na/Li exchange completion (see Supplementary Fig. 8). Further, the mesityl anion was trapped by adding one equivalent of N-methyl-N-methoxybenzamide to the mixture of 1 and mesityllithium in n-hexane (see Fig. 2). The resulting product mesityl(phenyl)methanone (5) was isolated and characterised by 1H NMR spectroscopy and GC-MS.

The sparing solubility of the mixture of 1 and mesityllithium in hexane could not be addressed even after shifting to the more polar diethyl ether (Et2O). However, the addition of one equivalent of tris[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]amine (Me6TREN) to this sparingly soluble mixture in diethyl ether resulted in a clear orange coloured solution. Upon adding one equivalent of N-methyl-N-methoxybenzamide, this reaction mixture turned colourless. The organic product from the reaction mixture was identified as 2-(3, 5-dimethylphenyl)acetophenone (6) (see Fig. 2). This observation indicates the in situ generation of 3,5-dimethylbenzyl anion, which is not observed with the mesityllithium and Me6TREN alone. We speculated on the formation of a highly reactive Brønsted basic sodium mesityl species that promotes intramolecular deprotonation, leading to the rearrangement of the mesityl anion into a 3,5-dimethylbenzyl anion.

To gain insights into the intramolecular C-H deprotonation, we ventured into the isolation of the reactive intermediates. Storing the orange-coloured solution resulting from the reaction between 1, mesityllithium and Me6TREN at −30 °C afforded bright yellow crystals. Single crystal XRD studies revealed that the product was a cationic organosodium compound, [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2C6H3(3,5-CH3)][(TpMe2)2Na] (7) (see Fig. 3). The 3,5-dimethylbenzyl anion bridges the two sodium atoms with Na1―C1 and Na2―C1 distances of 2.843(3) and 2.610(3) Å respectively (see Fig. 4). The Na-C-Na angle is observed to be nearly linear. Each of the sodium centres are additionally coordinated by the tetradentate Me6TREN. The coordination geometry at the sodium centres can be described best as trigonal bipyramidal. Compound 7 was further characterised by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. The 1H NMR spectrum recorded in THF-d8 reveals that the characteristic benzyl protons appear at 1.90 ppm. In the 13C NMR spectrum, the anionic benzylic carbon appears at δ 40.2 ppm (see Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). 1H-13C HMQC 2D NMR spectrum also supports our observation (see Supplementary Fig. 11).

a Solid-state structures of cationic parts of 7, 8, and 9 are represented by ellipsoids at a 35% probability level. For clarity, the hydrogen atoms in the structures are omitted. Selected distances are provided in ESI (See Pages S50, S53, S56). b 3D depiction of HOMO (isocontour 0.03) for complex 7. c Laplacian of the density plot (blue dots are Bond Critical Points) for complex 7 calculated using DFT-(B3PW91/6-311 + + G** for sodium atoms and 6-31 G** for nitrogen, carbon, oxygen and hydrogen atoms).

The trapping of 3,5-dimethylbenzyl anion in 7 strengthens our proposition of C-H deprotonation with the involvement of the highly reactive mixture of 1 and mesityllithium. Our next task was to probe the effect of this reaction mixture towards toluene and chemically related solvents. Accordingly, the colourless precipitate obtained from the reaction between mesityllithium, 1 and Me6TREN, carried out in n-hexane, was dissolved in toluene. The colourless solution instantaneously turned to bright orange. Concentrating the toluene solution and storage at −30 °C afforded orange colour crystals of [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2Ph][(TpMe2)2Na] (8), which is isostructural to the cationic organosodium compound 7 (see Figs. 3, and 4). The proton abstraction from toluene is favoured over the internal proton transfer, leading to another cationic sodium benzyl complex 8. We extended the C-H deprotonation to meta-xylene and obtained [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2C6H4(3-CH3)][(TpMe2)2Na] (9), which is isostructural to 7 and 8 (see Figs. 3, and 4). To understand their solution state behaviour, 1H-DOSY NMR experiments were carried out for 7, 8, and 9 in C6D6, which suggests that their monomeric nature remains intact even in the solution (see Supplementary Figs. 18, 19, and 20). The successful isolation of the cationic organosodium species 7, 8, and 9 demonstrates the use of 1 for the generation of a reactive mixture for the deprotonation of the benzylic protons.

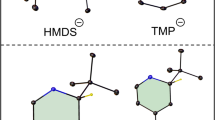

DFT calculations were carried out on 7-9 using B3PW91 functional, including dispersion corrections. The geometries were optimised in the absence of the counterion. The optimised geometries are satisfactorily reproduced by the computational method (See Supplementary Tables 9, 14 and 19). The electronic density was analysed using Natural Bonding Orbitals (NBO), Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) and Molecular Orbitals (MO) methods. The Na-C Wiberg Bond Indices (WBI) are very low in the range 0.01-0.02, indicating mainly non-covalent interactions between the alkali atom and the benzyl ligand. This is further corroborated by the inspection of the frontier orbitals of the different complexes, where the HOMO is the π* of the benzyl ligand without any contribution from the metal (see Fig. 4). This is in line with an ionic interaction as expected from the Natural Charges (Na:+0.9 and C:−0.9). There is a lack of orbital overlap and bonding interaction between the alkali cations and the benzyl anion. QTAIM analysis (see Fig. 4) indicates the presence of Na-C Bond Critical Points (BCP). The analysis of these bond critical points indicates that the density is low with a positive Laplacian and energy density with a negative Virial value (see Supplementary Table 13). This is in line with the ionic bonding model proposed by Lepetit et al., as well as Bianchi et al.32,33.

Having deprotonated toluene and xylene, the investigations were extended to ethylbenzene using 1/ mesityllithium/Me6TREN mixture. Competing C-H deprotonation of both the mesityl anion and ethylbenzene was observed, leading to the trapping of a remarkable ion pair, [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2C6H3(3,5-CH3)][(TpMe2)NaCH(CH3)C6H5] (10), bearing two different carbanions. While the 3,5-dimethylbenzyl anion resulting from the deprotonation of the mesityl anion is trapped between two Me6TRENNa moieties through its benzylic carbon reminiscent of the cationic moiety in 7 (see Fig. 5), the deprotonated ethyl benzene is bound to the sodium of NaTpMe2 unit in a η6-manner through its arene carbons. To sort out the competing deprotonation process, a less basic organolithium reagent - phenyllithium (PhLi), was employed instead of mesityllithium. To check the potency of PhLi, we revisited toluene deprotonation using PhLi/NaTpMe2/Me6TREN mixture and could successfully reproduce 8. But, the deprotonation of ethylbenzene using PhLi/NaTpMe2/Me6TREN did not yield any isolable crystals. However, quenching the reaction mixture with N-methoxy-N-methylbenzamide followed by an aqueous workup led to the quantitative isolation of 1,2-diphenylpropan-1-one, evidencing the generation of a single carbanion species from deprotonation at the benzylic C-H bond in ethylbenzene. Along the same lines, isopropylbenzene was deprotonated and reacted with N-methoxy-N-methylbenzamide to isolate 2-methyl-1,2-diphenylpropan-1-one in quantitative yields (see Fig. 6). The above observations underscore the efficacy of generating a strong basic mixture using PhLi.

Solid state structure of 10 is represented with ellipsoids at 35% probability level. For clarity, the hydrogen atoms in the structure are omitted. Selected bong distances (Å) in 10: Na1―N1 2.455(1), Na1―N2 2.548(2), Na1―N3 2.544(1), Na1―N4 2.471(2), Na2―N6 2.424(1), Na2―N8 2.456(2), Na2―N9 2.432(2) Na1―C7 2.610(2), Na3―C7 2.677(2).

To generate a cationic benzyl species of potassium and compare it sodium analogue 8, a reaction between mesityllithium, KTpMe2 and Me6TREN was carried out in toluene. This reaction led to the formation of an orange-red coloured solution, indicating the deprotonation. Keeping the reaction mixture at −30 °C afforded orange colour crystals. Single crystal-XRD revealed that the isolated complex, [(Me6TRENK)CH2C6H5·LiTpMe2] (11) is a mixed aggregate of Me6TREN supported potassium metallated benzyl and LiTpMe2 (see Fig. 7). The solid-state structure of 11 shows the benzyl anion being trapped in between the potassium and the lithium centres. The potassium centre interacts with the benzyl anion through π-arene interaction via η6-coordination of the arene ring and the lithium centre is bound to the benzylic carbon with a Li-C distance of 2.218(5) Å (see Fig. 7). While we did not end up with a cationic potassium compound similar to 8, the solid-state structure of 11 assumes importance as it is a rare example of a monomeric potassium/lithium mixed aggregate system.

Solid state structure of 11 is represented with ellipsoids at 35% probability level. For clarity, the hydrogen atoms in the structure are omitted. Selected bong distances (Å) in 10: K1―N7; 2.818(3), K1―N8 2.805(2), K1―N10; 2.797(3), K1―C17; 3.051(2), K1―C18; 3.070(3), K1―C19; 3.237(3), K1―C20; 3.368(3), K1―C21; 3.317(3), K1―C22; 3.160(3), Li1―N1; 2.077(5), Li1―N3; 2.049(5), Li1―N6; 2.058(5), Li1―C16; 2.218(5).

Compounds 7-9 are the rare examples of structurally characterised sodium benzyl cations. We tested the reactivity of these cations towards the carbonyl compounds - N-methoxy-N-methylbenzamide and an α, β unsaturated carbonyl, cinnamaldehyde. In both cases, immediate decolouration of 7-9 was observed, resulting in the benzylation of the carbonyls. The resulting benzylated products were isolated and characterised using NMR spectroscopy. The reaction with cinnamaldehyde yielded a kinetically controlled 1, 2- addition product rather than a thermodynamically controlled 1, 4-addition product, indicating high nucleophilicity of benzyl anion (see Fig. 8).

To check the potential of these cations 7, 8, 9 towards the generation of molecular sodium hydride complex34,35, we treated 8 with an excess amount of PhSiH3 in C6D6. The reaction mixture was monitored using 1H NMR spectroscopy. While there was no evidence for the formation of a “Na-H” species, we observed PhSiH3, Ph2SiH2, and SiH4 in the 1H NMR spectrum, which indicated the redistribution of PhSiH3 to a certain extent. Such silane redistributions usually involve the mediation of a hypercoordinated silylanion species36,37,38. Adding 1,1-diphenylethylene to this mixture initially did not lead to any reaction. However, heating this mixture at 80 °C resulted in PhSiH2CH2Ph2 and H3SiCH2Ph2 (see Fig. 9). We further observed that Ph2SiH2 formed during the reaction did not react with 1,1-diphenylethylene. Upon performing the reaction between PhSiH3 and 1,1-diphenylethylene at ambient temperature in the presence of 2 mol% of 8 in THF-d8, PhSiH2CH2PH2 was the only observed product, indicating that the redistribution gets arrested in a polar solvent. The reaction showed complete conversion within 35 min. While the reaction between Ph2SiH2 and 1,1-diphenylethylene was not observed in C6D6 even at elevated temperature, the reaction in THF-d8 at 80 °C resulted in the formation of Ph2SiHCH2Ph2 with 96% yield in 11 h (see Fig. 9). These observations indicate an ionic mechanism, proceeding possibly through a hydridosilyl anion pathway39.

DFT calculations were performed to understand the mechanistic details involving the reactivity of PhSiH3 with 8 (see Source Data for the geometric coordinates for all the species). We first attempted to compute cleavage of the cation, [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2Ph]+, into (Me6TREN)Na(CH2Ph) and [(Me6TREN)Na]+. This process was observed to be highly endothermic by 40.7 kcal.mol−1 and endergonic by 24.4 kcal.mol−1, thus ruling out this reaction pathway. However, [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2Ph]+ interacts with PhSiH3 to initially form a van der Waals adduct (Int1). A nucleophilic attack of the tolyl group occurs to the silane via TS1, leading to a hypervalent silyl anion [(Ph)H3Si(CH2Ph)]-, which is stabilised by the two [(Me6TREN)Na]+ cations forming Int2, in line with the recent literature reports on the generation of hydridosilyl anions from the reaction between s-block metal alkyls and silanes37,39,40.

The geometry around silicon in Int2 is a classical trigonal bipyramid with one hydrogen and the tolyl in the apical positions. The silyl anion interacts with one sodium through a hydrogen bond via hydrogen in the equatorial plane and the second via a phenyl Na π interaction through the tolyl substituent in the apical position. This coordination induces the activation of the apical Si−H bond while the equatorial ones remain undisturbed. This activated Si−H in the apical position is readily accessible to the 1,1-diphenylethylene for subsequent reaction. After forming a very stable van der Waals adduct of 1,1-diphenylethylene to Int2, resulting in Int3, a hydride transfer occurs from the silyl anion to the 1,1-diphenylethylene via TS2. At TS2, the hydride in the apical position of the silyl anion is transferred to the C2 of the 1,1-diphenylethylene (the most substituted one) while the C1 is interacting with sodium, allowing nucleophilic assistance to the hydride transfer since the relocalised negative charge at C1 is stabilised by the interaction with the sodium cation. Following the intrinsic reaction coordinate, it yields the stable silane adduct to the alkyl (CH2CHPh2) Int4, which readily replaces the formed (Ph)H2Si(CH2Ph) by PhSiH3 in Int5. Int5 then undergoes a similar reaction sequence as the one already described for [(Me6TRENNa)2CH2Ph]+ via a silyl anion formation followed by a hydride transfer to 1,1-diphenylethylene. This allows the regeneration of Int5, which is the catalyst of the hydrosilylation reaction, and the formation of (Ph)H2Si(CH2CHPh2). The highest barrier of the process is 24.0 kcal.mol−1 in enthalpy (26.4 kcal.mol−1 in Gibbs Free Energy), which aligns with kinetically accessible reactions (see Fig. 10).

After probing the 1,1-diphenylethylene reduction by experiments and computations, Hydrosilylation investigations were extended to α-methylstyrene, (Z)-prop-1-ene-1,2-diyldibenzene, and 2,3-dimethyl-1,3-butadiene. Unlike 1,1-diphenylethylene, the hydrosilylation of these olefins did not proceed at ambient temperature in THF-d8. Hence, they were performed at 60 °C in the presence of 10 mol% of 8. At this elevated temperature, silane redistribution was observed, further re-enforcing our hypothesis on the reaction pathway. Both PhSiH3 and SiH4, react with the respective olefinic substrates, leading to the corresponding hydrosilylated products (see Supplementary Table 1 and Pages S34-41 in SI).

In summary, the use of sodium tris(3,5-dimethylpyrazolyl)borate along with mesityllithium has not only provided a new and efficient route to access highly reactive organometallic mixture that can deprotonate benzylic C―H bonds, but also to facilitate the isolation of the distinct examples of cationic sodium benzyl species, which are otherwise not accessible by straightforward synthetic routes using the combination of RLi/NaOR. Tris(3,5-dimethylpyrazolyl)borate plays a crucial role in the reaction mixtures to form the stable anion [(TpMe2)2Na]− to charge balance the cationic sodium benzyl species opening new avenues in exploration of reactive organosodium compounds in chemical transformations.

Methods

Synthetic methods

All the manipulations were performed under inert conditions, either in vacuum or argon atmosphere, using Schlenk line techniques or argon argon-filled glove box41. The glassware used for the experiments was dried overnight at 200 °C prior to use. n-hexane was dried over CaH2, degassed, and stored over LiAlH4/3 Å molecular sieves before use. DEE and toluene were dried using Na, Ph2CO, degassed, and stored over LiAlH4. THF-d8 and C6D6 were dried using Na, Ph2CO, degassed and stored over Na/K alloy. Anhydrous LiNSiMe3 was procured from Sigma Aldrich without any purification. PhSiH3 and Ph2SiH2, were purchased from TCI Chemicals and dried before use. 1.6 M solution of PhLi in dibutylether was purchased from Otto Chemei Pvt. Ltd., India, and used without any further purification. 1,1-diphenylethylene, α-methylstyrene and 2,3-dimethyl-1,3-butadiene were dried over molecular sieves prior to use. (Z)-prop-1-ene-1,2-diyldibenzene was procured from BLD Pharmatech Ltd and dried under vacuum. All the synthesis was performed in greaseless glassware fitted with J Young joints.

Spectroscopic methods

NMR experiments were carried out in NMR tubes fitted with J. Young PTFE cap. Bruker Avance III 500 and 400 MHz spectrometer was used to record 1H, 13C, 7Li NMR at ambient temperature. Residual signals of the deuterated solvents were taken as reference for 1H, and 13C NMR, and chemical shift values are reported in ppm. GC-MS analyses of the isolated organic products were performed on an Agilent 5977 C GC/MSD system. Identification of the organic products were carried out by comparing their retention times, electron ionisation (EI) mass spectra.

Elemental analysis

Elemental Vario Micro Cube instrument was used for the elemental analysis of the well-dried samples at 1 × 10−3 mbar at ambient temperature.

Crystallograpic methods

All the crystals were coated with parabar oil before mounting them on the goniometer of the X-ray diffractometer. SC-XRD data for compound 2 was measured using Bruker Kappa Apex-II CCD diffractometer equipped with a CCD detector by using the APEX software package was used to perform single-crystal X-ray crystallography for structural analysis at 298 K under Mo-Kα radiation (wavelength-0.71073 Å). For the compounds 3,7, 8, 9, 10 and 11 data were collected on a Four-circle Kappa diffractometer Bruker D8 QUEST with a microfocus sealed tube using a multilayer mirror as monochromator and a Bruker PHOTON III C14 CPAD detector. The diffractometer used MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Additional details for data processing, structure refinement and graphic depictions are given in the Supplementary Information.

Computational methods

The DFT calculations were performed using Gaussian09 suite of programs42 by employing hybrid functional (B3PW91)43 along with Pople basis sets44,45 (6-311 + + G** for lithium, sodium atoms and 6-31 G** for nitrogen, carbon, oxygen and hydrogen atoms). Disperison corrections were included in our calculations by employing D3 version of Grimme’s dispersion with Becke-Johnson damping46. AIM analysis were carried out using Multiwfn software47. Natural bond analysis were performed using NBO 6.0 version implemented in Gaussian program48.

Data availability

The general methods, synthetic procedures, NMR, GC-MS and elemental analysis characterization data, single-crystal X-ray diffraction data and details about computational calculations are provided in the Supplementary Information. Crystallographic information files for 2 (2429099), 3 (2429100), 7 (2429101), 8 (2429102), 9 (2429103), 10 (2488925) and 11 (2488924) have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC). These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif or by emailing data_request@ ccdc.cam.ac.uk. Source Data are provided with this manuscript. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Bochmann, M. Organometallic Compounds of Main Group Elements. in Organometallics and Catalysis (Oxford University Press,). https://doi.org/10.1093/hesc/9780199668212.003.0001 (2014).

Luisi, R. & Capriati, V. Lithium Compounds in Organic Synthesis: From Fundamentals to Applications. (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2014).

Gentner, T. X. & Mulvey, R. E. Alkali-Metal Mediation: Diversity of Applications in Main-Group Organometallic Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9247–9262 (2021).

Anderson, D. E., Tortajada, A. & Hevia, E. New Frontiers in Organosodium Chemistry as Sustainable Alternatives to Organolithium Reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202313556 (2024).

XXII. On some new ethyl-compounds containing the alkalimetals. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 9, 341–345 (1859).

Seyferth, D. Alkyl & Aryl Derivatives of the Alkali Metals: Useful Synthetic Reagents as Strong Bases and Potent Nucleophiles. 1. Conversion of Organic Halides to Organoalkali-Metal Compounds. Organometallics 25, 2–24 (2006).

Benkeser, R. A., Foster, D. J., Sauve, D. M. & Nobis, J. F. Metalations With Organosodium Compounds. Chem. Rev. 57, 867–894 (1957).

Dilauro, G. et al. Introducing Water and Deep Eutectic Solvents in Organosodium Chemistry: Chemoselective Nucleophilic Functionalizations in Air. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202304720 (2023).

Klett, J. Structural Motifs of Alkali Metal Superbases in Non-coordinating Solvents. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 888–904 (2021).

Lochmann, L., Pospíšil, J. & Lím, D. On the interaction of organolithium compounds with sodium and potassium alkoxides. A new method for the synthesis of organosodium and organopotassium compounds. Tet. Lett. 7, 257–262 (1966).

Schlosser, M. Zur aktivierung lithiumorganischer reagenzien. J. Organomet. Chem. 8, 9–16 (1967).

Schade, C., Bauer, W. & Von Ragué Schleyer, P. n-Butylsodium: The preparation, properties and NMR spectra of a hydrocarbon- and tetrahydrofuran-soluble reagent. J. Organomet. Chem. 295, c25–c28 (1985).

Smith, W. T. & Nickel, D. L. The Utility Of Benzyl Sodium As A Reagent In Alcohol Synthesis. Org. Preparations Proced. Int. 7, 277–282 (1975).

Seyferth, D. Alkyl & Aryl Derivatives of the Alkali Metals: Strong Bases and Reactive Nucleophiles. 2. Wilhelm Schlenk’s Organoalkali-Metal Chemistry. The Metal Displacement and the Transmetalation Reactions. Metalation of Weakly Acidic Hydrocarbons. Superbases. Organometallics 28, 2–33 (2009).

Asako, S., Nakajima, H. & Takai, K. Organosodium compounds for catalytic cross-coupling. Nat. Catal. 2, 297–303 (2019).

Ito, S., Fukazawa, M., Takahashi, F., Nogi, K. & Yorimitsu, H. Sodium-Metal-Promoted Reductive 1,2- syn -Diboration of Alkynes with Reduction-Resistant Trimethoxyborane. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 93, 1171–1179 (2020).

Zhang, J.-Q., Ye, J.-J. & Han, L.-B. Selective P-C bond cleavage of tertiary phosphine boranes by sodium. Phosphorus, Sulfur, Silicon Relat. Elem. 196, 961–964 (2021).

Harenberg, J. H., Reddy Annapureddy, R., Karaghiosoff, K. & Knochel, P. Continuous Flow Preparation of Benzylic Sodium Organometallics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202203807 (2022).

Asako, S., Takahashi, I., Nakajima, H., Ilies, L. & Takai, K. Halogen–sodium exchange enables efficient access to organosodium compounds. Commun. Chem. 4, 76 (2021).

Davidson, M. G., Garcia-Vivo, D., Kennedy, A. R., Mulvey, R. E. & Robertson, S. D. Exploiting σ/π Coordination Isomerism to Prepare Homologous Organoalkali Metal (Li, Na, K) Monomers with Identical Ligand Sets. Chem. Eur. J. 17, 3364–3369 (2011).

Armstrong, D. R. et al. Monomerizing Alkali-Metal 3,5-Dimethylbenzyl Salts with Tris(N, N -dimethyl-2-aminoethyl)amine (Me6 TREN): Structural and Bonding Implications. Inorg. Chem. 52, 12023–12032 (2013).

Brieger, L., Unkelbach, C. & Strohmann, C. THF-solvated Heavy Alkali Metal Benzyl Compounds (Na, Rb, Cs): Defined Deprotonation Reagents for Alkali Metal Mediation Chemistry. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 17780–17784 (2021).

Tortajada, A., Anderson, D. E. & Hevia, E. Gram-Scale Synthesis, Isolation and Characterisation of Sodium Organometallics: n BuNa and NaTMP. Helv. Chim. Acta 105, e202200060 (2022).

Davison, N. et al. Li vs Na: Divergent Reaction Patterns between Organolithium and Organosodium Complexes and Ligand-Catalyzed Ketone/Aldehyde Methylenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6562–6576 (2023).

Anderson, D. E., Tortajada, A. & Hevia, E. Highly Reactive Hydrocarbon Soluble Alkylsodium Reagents for Benzylic Aroylation of Toluenes using Weinreb Amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218498 (2023).

Andrews, P. C., Fallon, G. D., Maguire, M. & Peatt, A. C. Crystal Structure of [(Ph(Me)C:N:C(H)Ph)K⋅(tBuOK)2⋅(thf)2]∞: A Unimetallic Mixed Anion Model for a “Superbase”? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 4516–4518 (2000).

Armstrong, D. R., Clegg, W., Drummond, A. M., Liddle, S. T. & Mulvey, R. E. A Remarkable Isostructural Homologous Series of Mixed Lithium−Heavier Alkali Metal tert -Butoxides [(t -BuO)8 Li4 M4] (M = Na, K, Rb or Cs). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 11117–11124 (2000).

Unkelbach, C., O’Shea, D. F. & Strohmann, C. Insights into the Metalation of Benzene and Toluene by Schlosser’s Base: A Superbasic Cluster Comprising PhK, PhLi, and t BuOLi. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 553–556 (2014).

Trofimenko, S. Recent advances in poly(pyrazolyl)borate (scorpionate) chemistry. Chem. Rev. 93, 943–980 (1993).

Trofimenko, S. Scorpionates: The Coordination Chemistry of Polypyrazolylborate Ligands. (Imperial College Press,). https://doi.org/10.1142/p148 (1999).

Reglinski, J. & Spicer, M. D. Chemistry of the p-block elements with anionic scorpionate ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 297–298, 181–207 (2015).

Bianchi, R., Gervasio, G. & Marabello, D. Experimental Electron Density Analysis of Mn2 (CO)10: Metal−Metal and Metal−Ligand Bond Characterization. Inorg. Chem. 39, 2360–2366 (2000).

Lepetit, C., Fau, P., Fajerwerg, K., Kahn, M. L. & Silvi, B. Topological analysis of the metal-metal bond: A tutorial review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 345, 150–181 (2017).

Roy, M. M. D. et al. Molecular Main Group Metal Hydrides. Chem. Rev. 121, 12784–12965 (2021).

Aldridge, S. & Downs, A. J. Hydrides of the Main-Group Metals: New Variations on an Old Theme. Chem. Rev. 101, 3305–3366 (2001).

Lipke, M. C. & Tilley, T. D. Stabilization of ArSiH4− and SiH62− Anions in Diruthenium Si-H σ-Complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 11115–11121 (2012).

Prince, P. D., Bearpark, M. J., McGrady, G. S. & Steed, J. W. Hypervalent hydridosilicates: synthesis, structure and hydride bridging. Dalton Trans. 271–282 https://doi.org/10.1039/B713427D (2008).

Schuhknecht, D. et al. Alkali Metal Triphenyl- and Trihydridosilanides Stabilized by a Macrocyclic Polyamine Ligand. Chem. Eur. J. 26, 2821–2825 (2020).

Schuhknecht, D., Leich, V., Spaniol, T. P. & Okuda, J. Hypervalent Hydrosilicates Connected to Light Alkali Metal Amides: Synthesis, Structure, and Hydrosilylation Catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 13424–13427 (2018).

Höllerhage, T. et al. Formation and Reactivity of a Hexahydridosilicate [SiH6]2− Coordinated by a Macrocycle-Supported Strontium Cation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202115379 (2022).

Lever, A. B. P. Advanced Practical Inorganic and Metalorganic Chemistry, Edited by Errington, R. J. Blackie Academic & Professional, New York, 1997. ISBN 0751402257; pp. 288; £25.00. Coord. Chem. Rev. 213, 329–330 (2001).

Gaussian ∼09 Revision D.01. Frisch M. J. et al. Fox Gaussian Inc., 2009, Wallingford CT.

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Blaudeau, J.-P., McGrath, M. P., Curtiss, L. A. & Radom, L. Extension of Gaussian-2 (G2) theory to molecules containing third-row atoms K and Ca. J. Chem. Phys. 107, 5016–5021 (1997).

Francl, M. M. et al. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XXIII. A polarization-type basis set for second-row elements. J. Chem. Phys. 77, 3654–3665 (1982).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

NBO 6.0Glendening, E. D. et al. (Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, 2013).

Acknowledgements

A.V. thanks the Science and Engineering Research Board, Government of India (CRG/2023/004024) for generous funding. L.M. is a senior member of the Institut Universitaire de France. We thank CalMip for a generous grant of computing time.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. and K.R. conducted experiments and analysed the data. A.P.A. deduced the X-ray structures. T.R. and L.M. performed DFT investigations. A.V. conceptualized and supervised the work. All the authors contributed towards the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Joaquín García-Álvarez and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kundu, S., Raj, K., Andrews, A.P. et al. Isolation and reactivity of sodium benzyl cations. Nat Commun 16, 11432 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66336-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66336-0