Abstract

The efficient discrimination of industrially relevant gases, particularly those with closely analogous physicochemical properties, remains a formidable challenge within the realm of adsorptive separation technologies. Achieving satisfactory separation efficiency poses stringent requirements on the precise control over the pore structures of adsorbents. Here we introduce a strategy for the precise modulation of pore structures in a carbonate-pillared Zn-triazolate framework, Zn2(datrz)2CO3 (datrz = 3,5-diamino-1,2,4-triazolate), through the straightforward adjustment of the solvothermal synthesis temperature. Utilizing this approach, we have successfully fabricated a series of Zn2(datrz)2CO3 materials with tunable pore structures while maintaining the framework composition and overall connectivity. These materials demonstrate selective recognition for challenging gas mixtures, including C3H6/C3H8, CO2/CH4, and CO2/N2. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations confirm that the precisely engineered pore environment plays a decisive role on selective gas adsorption. Further, the high reproducibility and scalability of this temperature-controlled synthesis method underscore its immense potential for industrial-scale applications in gas purification and separation processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The precise discrimination of gas molecules with similar physicochemical properties remains a persistent challenge in adsorptive separation technologies, yet it is critical for applications ranging from carbon capture to hydrocarbon purification1,2. The high degree of similarity in molecular dimensions, polarizability, and/or quadrupole moments among the target molecules imposes stringent demands on the pore structure and functionality of adsorbents. To achieve satisfactory separation efficiency, it is imperative that the adsorbent exhibits precise control over its pore shape, pore size, and pore surface chemistry3,4. However, this level of precision is often elusive with traditional porous solids such as zeolites and carbons, where fine-tuning of pore features can be difficult or even unattainable5. In contrast, emerging crystalline framework materials, exemplified by metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), offer a promising solution6. The pore characteristics of MOFs, which are defined by the self-assembly of preselected building blocks, can be precisely manipulated by adjusting the physical and chemical characteristics of these building units, the way they combine, and their geometric configurations within the integrated structures7.

The tunability of MOFs' pore structures has been primarily practiced through several strategies. The most widely adopted approach involves linker engineering, which entails modifying the skeletal structure, dimensions, configuration, and functional groups of organic linkers8,9,10. This directly influences the pore size, pore shape, and surface functionality of the resulting MOFs. Nevertheless, precise linker engineering can sometimes be challenging or even unfeasible using common organic synthesis reactions. Another strategy, known as pore space partition (PSP), involves creating tailored pores by post-synthetically subdividing existing larger pores using auxiliary ligands11,12. Effective PSP requires a precise match between the installed linker and the partitioned pores with respect to geometry, dimensions, and binding characteristics. Additionally, recent studies have demonstrated that pore engineering can also be achieved through the replacement of inorganic secondary building units (SBUs)13,14,15. For instance, substituting Zr6 nodes in Zr-MOFs with analogous Y6 clusters while preserving the overall framework topology can finely tune the accessible pore dimensions16. However, this strategy is limited to specific types of networks where isoreticular SBU displacement is possible.

Apart from the aforementioned pore engineering strategies that involve elaborate modifications of the building blocks and/or the overall networks, synthetic regulation of the solvothermal parameters offers a distinct yet straightforward method for tuning the structures and pore features of MOFs17,18. This is accomplished without additional pre- or post-modifications of the inorganic nodes or organic linkers. By employing the same building units, the topology and/or pore structures can be engineered through slight variations in solvothermal conditions (e.g., temperature, solvents, modulators), which alter the geometry/configuration of the building blocks or their connection modes19. Although extensive studies have been carried out on constructing different MOF structures from the same combination of building units through synthetic modifications, precise pore engineering through delicate solvothermal optimization remains undocumented, despite its crucial importance for efficient molecular discrimination.

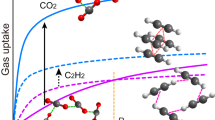

In this work, we present an approach for the precise regulation of the pore structure of a carbonate-pillared Zn-triazolate framework, Zn2(datrz)2CO3, by finely tuning its synthetic temperature. Systematic variation of the solvothermal temperature yielded four crystalline phases, all constructed from the same building units but exhibiting two types of topologies and varied pore geometries. In particular, three of these structures—Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180, 200, and 220—feature identical topology. However, subtle rotations of the datrz2− ligands along the channels resulted in the formation of sub-angstrom gradients in pore dimensions, enabling fine-tuning of their molecular recognition behaviors. Specifically, these structural variants demonstrate high discrimination efficiency for physicochemically similar yet industrially relevant mixtures, including CO2/N2, CO2/CH4, and C3H6/C3H8 (Fig. 1). Experimental validation has confirmed that these carbonated-pillared porous structures synthesized at precisely controlled temperatures exhibit excellent reproducibility, stability, and scalability. Unlike traditional pore engineering strategies that rely on modifying framework components, our approach offers a structurally minimalist yet functionally effective route to precisely tune pore structures and separation efficacy of MOFs by regulating solvothermal synthetic temperature.

Results

Synthesis and structure

A solvothermal reaction involving zinc nitrate hydrate, H2datrz, and a mixed solvent of water and N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) at four different temperatures (160, 180, 200, and 220 °C) yielded four distinct crystalline phases, denoted as Zn2(datrz)2CO3-160, -180, -200, and -220 (Fig. 2a). The structure of these four phases was exclusively analyzed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD). The asymmetric units and crystallographic data are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1, respectively. Structure analysis revealed that Zn2(datrz)2CO3-160 crystallizes in the orthorhombic crystal system with a space group of Pnma, while the remaining three analogs share the same space group of P21/c in the monoclinic crystal system. All four compounds exhibit a pillar-layered framework. Specifically, the structures consist of Zn2+ nodes coordinated with datrz2− ligands to form two-dimensional layers, which are subsequently pillared by carbonate anions, forming a three-dimensional architecture. It's worth noting that the carbonate anions in the structures originate from the thermal decomposition of DMF at high temperatures, as no carbonate salts were added to the starting materials20.

a Structure of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-160–220. b Rotation degree of datrz and the regulated pore size evolution of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180–220. c FT k3-weighted χ(k)-function of the EXAFS spectra at Zn K-edge. d Relative framework energy of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-160–220. (Color code: C, gray; N, blue; O, red; Zn polyhedron, magenta).

In the structure of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-160, the wave-shaped layers are arranged in an alternating manner (peak-to-valley), while the networks of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180–220 adopt a more parallel stacking configuration (Supplementary Figs. 2and 3). This structural transition resulted in two distinct topologies: {4 · 6 · 8} {4 · 62 · 83} for Zn2(datrz)2CO3-160 and a dma topology for Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180–220 (Supplementary Fig. 4). This leads to notable differences in their pore structure. In Zn2(datrz)2CO3-160, the stacking layers create interlayer voids that are enclosed by the layers and carbonate pillars. A potential through-layer channel defined by Zn-datrz connectivity exists, however, it remains closed due to the large angle between the datrz2− ligand and the channel direction (31.35°) (Supplementary Fig. 5). In contrast, the stacking mode in Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180–220 eliminating the interlayer channel observed in Zn2(datrz)2CO3-160 but preserved the through-layer channel (Supplementary Fig. 3). As the temperature increases, the angle between datrz2− and the channel direction systematically decreases from 24.84° at 180 °C to 12.41° at 220 °C, effectively modulating the pore size with sub-angstrom precision (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 5). To the best of our knowledge, this represents the demonstration of continuous and precise pore structure modulation in MOFs solely through tuning the solvothermal temperature, offering a feasible route for MOF pore engineering.

To further verify the influence of temperature on Zn coordination environment, the Zn oxidation state and local coordination environment were investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). In the XPS survey spectra, the peaks of C 1s, N 1s, O 1s, and Zn 2p are observed. High-resolution Zn 2p spectra consistently display the Zn2+ doublet at ~1019 and ~1042 eV, with negligible binding-energy shifts among the samples (Supplementary Fig. 6), confirming that Zn remains divalent regardless of synthesis temperature. Complementary Zn K-edge XAS was conducted on the dma phases (180–220 °C). The X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) shows absorption energies lying between Zn foil and ZnO references, closely matching ZnO, further verifying the Zn2+ oxidation state (Supplementary Fig. 7). The corresponding Fourier-transformed (FT) k3-weighted extended region (EXAFS) yields ~4 N/O neighbors at ~1.95–1.96 Å (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 8, and Supplementary Table 2), demonstrating an invariant Zn2+ coordination environment, in agreement with SCXRD results.

Since adsorbents are typically employed at ambient temperature and in the activated state, we further collected SCXRD data at room temperature (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180RT, -200RT, and -220RT) and for their activated analogs (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180A, -200A, and -220A) to confirm that the pore structure modulation persists under these conditions. The structures collected at RT show rotation angles of the datrz2− ligands that are essentially identical to those obtained at 193 K (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Table 3). Upon activation, all three analogs display slightly reduced rotation angles, yet the ordering remains unchanged (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180A > 200 A > 220 A), indicating that activation preserves the trend (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Table 4). Furthermore, a crystal synthesized at 190 °C (test at room temperature) shows an intermediate rotation angle (20.4°, Supplementary Fig. 9) between Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180RT and Zn2(datrz)2CO3-200RT, indicating that the aperture evolution follows a continuous rather than a discrete trend.

To delineate the onset of pillaring, we further conducted control hydrothermal reactions below the main temperature window. At 120 °C, only the layered Zn(datrz)(fa) (fa = formic acid, Supplementary Fig. 11) precursor was obtained. Near the phase boundary (140 °C), a partially transformed product was isolated, consistent with the coexistence of the layered precursor and the carbonate-pillared framework (Supplementary Fig. 11). These observations indicate that higher thermal input is required to generate carbonate in situ and to initiate the pillaring process. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) profiles of products collected at different reaction times at 180, 200, and 220 °C (Supplementary Figs. 12–14) further reveal that the layered intermediate initially coexists with the carbonate-pillared framework but is consumed more rapidly as the temperature increases. The characteristic reflections of the dma phase emerge earlier at 200 and 220 °C than at 180 °C, evidencing a shortened induction period and accelerated nucleation and growth of the thermodynamically favored framework.

These synthetic temperature-dependent structural evolutions in local coordination geometries have profound effects on the overall framework energetics. The total energy of the framework decreases as solvothermal temperature rises, suggesting that elevated synthetic temperatures facilitate the overcoming of energy barriers to access thermodynamically favored structures (Fig. 2d).

Stability and porosity

To assess the structural robustness, porosity, and thermal response of these compounds, a comprehensive set of characterizations was conducted. PXRD patterns of both the as-synthesized and activated samples of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180–220 are in good agreement with the simulated patterns, confirming their good stability during activation (Supplementary Fig. 15). It is worth noting that the relative PXRD peak intensities change after activation, although the peak positions remain unchanged. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images collected before and after activation (Supplementary Figs. 16–19) show partial fragmentation of the crystallites after solvent removal. Such breakage alters the preferred orientation of the crystals during PXRD measurement, thereby accounting for the variation in relative diffraction intensities. A notable phase transition occurs for Zn2(datrz)2CO3-160 upon activation. Specifically, new peaks associated with the dma topology appear at approximately 10.5, 13.5, 14.3, and 27.3°, indicating partial conversion of the original phase into a dma framework. This transition is consistent with the metastable nature of the intermediate phase formed at 160 °C, which transforms to the thermodynamically more favorable structure upon activation. Crystal of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180A was also heated at 220 °C under vacuum (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180VT) and in a DMF solvothermal environment (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180ST) for 12 h to probe possible phase transition. The resulting single-crystal structures exhibit rotation angles comparable to those of activated Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180A (Supplementary Fig. 20, and Table 4), thereby excluding the occurrence of a phase transition. Therefore, in the following sections, we focus on a detailed study of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180–220. Thermal stability was evaluated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) under a nitrogen atmosphere (Supplementary Fig. 21). All samples exhibit good thermal stability, with major weight loss occurring above 300 °C, which is associated with structural decomposition. This is further confirmed by variable-temperature PXRD (VT-PXRD) measurements (Supplementary Fig. 22), where no notable variations in PXRD patterns were observed up to 300 °C. Long-term stability of the materials was systematically evaluated under various conditions for one week. The samples were immersed in aqueous solutions with pH values ranging from 3 to 13, as well as in common organic solvents (methanol, ethanol, and acetone). PXRD patterns collected afterwards revealed no significant loss of crystallinity or peak shifts, indicating that the frameworks remain stable across pH 3–11 and in common organic solvents. Among all samples, only Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220 preserved its crystallinity under the harsher alkaline condition of pH 13, highlighting its enhanced chemical robustness. In addition, the samples maintained their crystallinity after exposure to a 150 °C atmosphere, confirming their good thermal robustness (Supplementary Figs. 23–25).

All three compounds take up negligible N2 at 77 K, which can be attributed to their limiting pore size (Supplementary Fig. 26). Thus, CO2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at 196 K were carried out to evaluate the BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) surface area and porosity (Supplementary Figs. 27–29). The samples exhibit reversible type-I adsorption profiles, indicative of permanent microporosity. The BET surface areas were calculated to be 198.83 m2/g for Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180, 212.59 m2/g for Zn2(datrz)2CO3-200, and 189.13 m2/g for Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220. Pore size distributions (PSD) derived from the CO2 isotherms using the Horvath–Kawazoe method provide further insight into the pore size evolution. The PSD graph shows ranges of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180, -200, and -220 partially overlap; however, their dominant PSD peaks (most-probable pore sizes) shift systematically from 3.59 Å to 4.06 Å and 4.23 Å with increasing synthesis temperature. In ultramicroporous systems, both molecular transport and adsorption affinity are primarily governed by the most-probable pore size rather than by the overall distribution range21,22. Therefore, subtle shifts in the most-probable pore size enable effective modulation of the adsorption and separation performance.

Gas adsorption and separation

The gas adsorption and separation capabilities of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180–220 for industrially relevant gases including C3H6, C3H8, CO2, CH4, and N2 were systematically evaluated using single-component isotherms (Fig. 3a, b) and ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST)23 selectivity calculations for equimolar and real-world conditions at 298 K (Supplementary Fig. 30, fitting parameters were listed in Supplementary Table 5). Among the three compounds, Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 possesses the smallest pore size (3.0 × 3.4 Å), which is close to the minimum cross-section of C3H6 (3.3 × 4.2 Å), however much smaller than that of C3H8 (3.8 × 4.1 Å)24. This leads to a pronounced molecular sieving effect for the C3H6 and C3H8. Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 exhibits a C3H6 uptake of 17.07 cm3/g at 298 K and 1 bar while completely excluding C3H8 (<1.0 cm3/g), yielding a C3H6/C3H8 IAST selectivity (50/50, v/v) exceeding 1 × 107 (Fig. 3a). This selectivity is among the highest for reported porous materials and surpasses that of most state-of-the-art adsorbents, including Co-gallate25, JNU-326, and KAUST-727. Notably, the selectivity is further enhanced under propylene-rich conditions, reaching 2.31 × 107 at a 95/5 feed composition, highlighting the robustness of the sieving effect at industrially relevant concentrations(Supplementary Table 6). The kinetic uptake profiles for C3H6 and C3H8 are shown in Supplementary Fig. 31. To quantify the diffusion rates, the profiles were fitted to obtain the diffusion time constants (D′ = D/r2). The D′ of C3H6 is determined to be 5.93 × 10−3/s, which is approximately twice that of C3H8 (2.90 × 10−3/s). Moreover, the C3H6 diffusion constant of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 is significantly higher than those reported for benchmark MOFs such as HAF-1 (3.0 × 10−5/s)28 and NCU-20 (2.32 × 10−5/s)29, further highlighting the good kinetics of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was employed to directly determine the adsorption heat. The heat of adsorption for C3H6 was 34.58 kJ/mol, while a low value was observed for C3H8 due to its negligible adsorption (Supplementary Fig. 32).

a C3H6 and C3H8 adsorption-desorption isotherms at 298 K. b CO2, CH4 and N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at 298 K. c The comparison of C3H6/C3H8 (50/50, v/v) IAST selectivity for Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 and other benchmark adsorbents25,26,27,49,50,51,52,53,54,55. d The comparison of CO2/N2 (15/85, v/v) IAST selectivity for Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220 and other benchmark adsorbents31,32,33,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63. Error bars represent the standard deviations from three independent measurements.

As the solvothermal temperature increases, the pore size of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-200–220 gradually increases. This structural evolution results in increased uptake of both C3H6 and C3H8; however, the molecular sieving effect is significantly diminished, highlighting the critical importance of precise pore size control for achieving effective molecular sieving. The enlarged pores (4.4 × 4.6 Å) in Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220 allow gases CO2 (3.3 × 3.2 Å), N2 (3.0 × 3.1 Å), and CH4 (3.8 × 3.9 Å) into the framework, where the values in parentheses denote the smaller cross-sectional dimensions of the respective molecules30. It is worth noting that the CO2 adsorption isotherm at low pressure becomes steeper, indicating a stronger affinity between CO2 and the framework. In contrast, the adsorption of CH4 and N2 was significantly suppressed with a minimal uptake (Fig. 3b). This can be attributed to the size-matching effect: as the pore size enlarges, the confinement weakens, leading to reduced CH4 uptake. The IAST selectivity values exceed 1.1 × 104 for CO2/N2 (15/85, v/v) and 3.4 × 105 for CO2/CH4(50/50, v/v), exceeding most state-of-the-art MOFs, including, MIP-202 (2129)31, In(aip)2 (2635)32, TYUT-ATZ-β (2031)33 for CO2/N2 separation, and ZUL-100 (3.2 × 105)34, Qc-5-Cu-sql-β (3300)35, ZU-66 (136)36 for CO2/CH4 separation. Under equimolar CO2/N2 conditions, the selectivity further rises to 9.41 × 105, while for CO2/CH4 mixtures with a CO2-lean feed (15/85, v/v), a high value of 5.7 × 103 is still maintained, underscoring the robustness of the separation performance across varying compositions. (Supplementary Table 6). The adsorption heats of CO2, CH4, and N2 by fitting isotherms using the Virial equation37 were 28.00, 22.42, and 11.67 kJ/mol, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 33–35), confirming the much stronger interaction between CO2 and the framework.

Notably, this temperature-directed pore structure tuning strategy exhibits excellent reproducibility and scalability. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 36 and37 and Table 7, independently synthesized three batches of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 and Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220 display highly reproducible gas adsorption and separation performance. The mean IAST selectivity values obtained from three independent measurements are presented in Fig. 3c, d and Supplementary Fig. 3834,35,36,38,39,40,41,42,43, together with literature benchmarks, demonstrating the excellent performance of the materials (Supplementary Tables 8–10). Furthermore, a 50-fold scale-up synthesis of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 yields products that not only retain structural integrity as confirmed by consistent PXRD patterns but also preserve their gas adsorption characteristics.

Computational studies

Inspired by the well-defined structure-function relationship, we use density functional theory (DFT) calculations to explore the molecular-level insights of the selective adsorption mechanisms44,45,46. As shown in Fig. 4, the diffusion barriers of C3H8 and C3H6 were calculated across the three Zn2(datrz)2CO3 series frameworks (Fig. 4a, b). The optimized structures and C3H6/C3H8 molecules served as the reference energy state (State I, Supplementary Fig. 39). A single molecule was then placed near the framework (State II), diffused through the channel aperture (State III), and entered the internal cavity (State IV). The energy barrier (ΔE) was calculated to assess the difficulty of gas diffusion. The results indicate that the ΔE for C3H6 is consistently lower than that for C3H8, implying that the pore sizes of all materials are suitable for the preferential diffusion of C3H6 over C3H8. Additionally, by analyzing the difference in ΔE for two gas molecules (Fig. 4c), we observed that the ΔE difference gradually decreases from Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 to Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220, which aligns well with the changes in pore size and the corresponding C3H6/C3H8 separation performance. Furthermore, the adsorption sites for C3H6 in Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 were also investigated using DFT calculations. The C3H6 molecule interacts with one oxygen atom from the CO32− ligands through CH···O interactions (1.78 Å) and one nitrogen atom from the datrz2− ligands through C–H···N interactions (1.79 Å) (Fig. 4d). The calculated binding energy was 32 kJ/mol, which is consistent with the adsorption heat.

DFT-calculated static energies for Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 (pink line), -200 (blue line), and -220 (orange line) on C3H8 (a) and C3H6 (b) diffusions. c The difference in ΔE for two gas molecules. The optimized binding sites for C3H6 (d) and CO2 (e) on Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180. f The optimized binding sites for CO2 on Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220. (Color code: C, gray; N, blue; O, red; Zn, magenta; H, white).

As shown in Fig. 4e, CO2 adsorption on Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 occurs through two NH···O hydrogen bonds (1.63 and 1.59 Å), each formed with amino groups from two datrz2− ligands, yielding a calculated binding energy of 27 kJ/mol. In contrast, on Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220 (Fig. 4f), the reduced rotation angle of the datrz2− ligands generates a confined pocket that allows CO2 to simultaneously interact with four amino groups via NH···O interactions (ranging from 1.92 to 2.68 Å). This multidentate interaction site significantly enhances the binding energy to 34 kJ/mol, which accounts for the steeper CO2 adsorption profile observed at low pressure. For CH4, both materials exhibit similar interaction modes, where the CH4 molecules interact with the amino groups via CH···N interactions and with the carbonate groups via CH···O interactions (Supplementary Fig. 40). However, the interaction distances in Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 (2.23 and 2.29 Å for CH···O and CH···N respectively) were shorter than Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220 (2.32 and 2.63 Å for CH···O and CH···N respectively). This leads to a markedly lower binding energy in Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220 (15 kJ/mol) compared to Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 (21 kJ/mol). The reduction can be attributed to the larger pore size in Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220, which weakens the confinement effect and thus decreases the interaction strength with CH4 molecules. For N2 in Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220, DFT locates a primary site in which the linear N2 molecule sits near the channel wall with an end-on orientation toward the amino groups of the datrz linker. The terminal N atom engages in an NH···N interaction (2.20 and 2.79 Å), but the number of simultaneous interactions is small, resulting in a binding energy of only 18 kJ/mol (Supplementary Fig. 40). Consequently, the uptake of N2 is lower than that of CO2. Together, these calculations highlight how subtle rotational changes in the datrz2− ligands influence both pore geometry and the local adsorption environment, which plays a crucial role in determining gas adsorption strength and selectivity.

Dynamic breakthrough experiments

The dynamic separation performance of the Zn2(datrz)2CO3 series was systematically evaluated via fixed-bed breakthrough experiments using C3H6/C3H8, CO2/CH4, and CO2/N2 binary mixtures at 298 K. Each gas pair was tested under both equimolar and dilute feed compositions to simulate realistic separation scenarios (C3H6/C3H8: 95/5; CO2/N2: 15/85; CO2/CH4: 15/85, v/v). Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 showed excellent separation performance for C3H6/C3H8, exhibiting well-defined separation windows (Fig. 5a, b). The desorption profiles revealed C3H6 recovery with high purity levels of 95.69% and polymer-grade purity of 99.53% under 50/50 and 95/5 compositions, respectively, with corresponding productivity of 13.32 and 13.69 L/kg (Supplementary Table 11). Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220 demonstrated high dynamic CO2 selectivity in both CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 separations, where a single adsorption-desorption cycle enabled the recovery of high-purity CO2 (96.82% at 50/50 and 95.33% at 15/85 for CO2/N2; 95.75% at 50/50 and 89.20% at 15/85 for CO2/CH4) and >99.99% purity of CH4 (Fig. 5c, d and Supplementary Fig. 41). The corresponding productivities further confirm the practical working capacity of the materials (Supplementary Table 11). For CO2/N2 mixtures, Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220 delivers CO2 productivities of 20.70 L/kg (50/50, v/v) and 14.59 L/kg (15/85, v/v). For CO2/CH4 mixtures, the CO2 productivities are 16.53 L/kg (50/50, v/v) and 12.62 L/kg (15/85, v/v), while the co-produced CH4 productivities reach 17.27 L/kg and 49.39 L/kg, respectively. This performance highlights the material’s potential for low-concentration natural gas/biogas purification and flue gas CO2 capture. To simulate realistic conditions, we have performed additional CO2/N2 (15/85, v/v) breakthrough experiments under humid conditions (relative humidity = 43%). The results (Supplementary Fig. 42) confirm that the separation performance of Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220 is well retained in the presence of water vapor, demonstrating good water resistance. All materials exhibited stable performance over four consecutive breakthrough-regeneration cycles and maintained consistent PXRD patterns (Supplementary Figs. 43 and44) afterwards, confirming the structural robustness and long-term durability of the Zn2(datrz)2CO3 series.

Dynamic breakthrough (left) and desorption (right) curves for C3H6/C3H8 mixtures on Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 with feed composition of 50/50, v/v (a) and 95/5, v/v (b). Dynamic breakthrough (left) and desorption (right) curves for CO2/N2 mixtures on Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220 with feed composition of 50/50, v/v (c) and 15/85, v/v (d).

Discussion

By optimizing the solvothermal temperature, we developed an approach for the fine regulation of MOF pore structures. The obtained Zn2(datrz)2CO3 series exhibits a precise pore gradient, demonstrating engineered gas separation performance for industrially relevant mixtures, including C3H6/C3H8, CO2/N2, and CO2/CH4. The scalability and reproducibility of Zn2(datrz)2CO3 validate the potential of the proposed solvothermal temperature-regulated pore structure engineering approach for practical applications. This synthetic temperature-guided strategy enriches the current pore engineering toolbox and may contribute to the development of MOFs with enhanced molecular recognition capabilities.

Methods

Materials and characterizations

All chemicals were commercially available and used without further purification. SCXRD data were collected on a Bruker D8 VENTURE diffractometer equipped with a PHOTON II CPAD detector. The crystal structures were solved using SHELXT (version 2018/2) and refined by full-matrix least-squares methods using SHELXL (version 2018/3) via the OLEX2 graphical interface. PXRD patterns were recorded on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer using Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) over a 2θ range of 3–40° at a scan rate of 5° min−1, with an operating voltage and current of 40 kV and 40 mA, respectively. TGA was performed under a static nitrogen atmosphere using a NETZSCH simultaneous thermal analyzer at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. The morphology of the compounds was collected using SEM (10 kV, JSM-IT800) and TEM (200 kV, JEOL JEM-F200). Surface chemical states were investigated by XPS using a Kratos AXIS SUPRA+ spectrometer. Transmission XAS measurements were performed on a laboratory device (easyXAFS300, easyXAFS LLC), which is based on Rowland circle geometries with spherically bent crystal analyzers (SBCA) and operated using an Ag X-ray tube source and a silicon drift detector (AXAS-M1, KETEK GmbH). Data reduction, data analysis, and EXAFS fitting were performed and analyzed with the Athena and Artemis programs of the Demeter data analysis packages that utilize the FEFF6 program to fit the EXAFS data47,48.

Synthesis of MOFs

Small-scale synthesis

Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (0.5 mmol) and 3,5-diamino-1,2,4-triazolate (0.5 mmol) were dissolved in DMF/H2O (3/3 mL). The mixture was transferred to a 20-mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and left in a 160, 180, 200, and 220 °C oven for 24 h to form crystals suitable for structure resolution by single-crystal X-ray crystallography. The as-synthesized products were harvested by filtration and washed with fresh hot DMF five times, and then exchanged with methanol by Soxhlet extraction overnight. Finally, the crystals were activated at 120 °C in dynamic vacuum for 12 h to yield an activated sample.

Large-scale synthesis

Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (25 mmol, 7.44 g) and 3,5-diamino-1,2,4-triazolate (25 mmol) were dissolved in a mixed solvent of DMF (150 mL) and deionized water (150 mL) under stirring. The solution was transferred into a 0.5 L Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and heated at 160, 180, or 220 °C for 24 h. After cooling to room temperature, the resulting colorless bulk crystals were collected by filtration and washed thoroughly with DMF. The as-synthesized products were then exchanged with methanol five times. Finally, the crystals were activated under dynamic vacuum at 120 °C for 12 h to yield the fully desolvated samples.

Multicomponent column breakthrough tests

Breakthrough tests were carried out in a homemade breakthrough apparatus. The adsorption bed was a stainless-steel column (inner diameter: 6 mm, 150 mm). The mass of adsorbents filled into the column was 1.20 g and 1.35 g for Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180 and -220, respectively. The humid gas stream was generated by passing the feed gas through a saturated potassium carbonate solution, corresponding to 43% relative humidity. The adsorbents were activated for 10 h under helium purging (10 mL/min). When the temperature cooled down to 298 K, helium flow was stopped, and the feed mixed gases at a flow rate of 5 mL/min were introduced to the adsorption column. The outlet gas was analyzed by using a mass spectrometer (HPR-20, Hiden). After the adsorption reached dynamic equilibrium, the column was purged with helium (10 mL/min) at 298 K for desorption.

The purity, using CO2/CH4 mixture as example, was calculated by the following method: the desorption gas amount (qi) was calculated by integrating the desorption curve f(t) as Eq. (1).

Where the m represents the adsorbent mass, Q represents the feed gas flow rate and ci represents the fraction of components in the feed gas mixture.

And then the purity (p) of desorption CO2 was calculated using the following Eq. (2).

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2447138 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220), 2447139 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-160), 2447140 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-200), 2447141 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180), 2491950 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180A), 2491951 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-200A), 2491952 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220A), 2491953 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180RT) 2491954 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-190RT), 2491955 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-200RT), 2491956 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-220RT), 2491957 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180ST) and 2491958 (Zn2(datrz)2CO3-180VT). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Li, J. R., Kuppler, R. J. & Zhou, H. C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1477–1504 (2009).

Wang, H., Luo, D., Velasco, E., Yu, L. & Li, J. Separation of alkane and alkene mixtures by metal–organic frameworks. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 20874–20896 (2021).

Lin, R. B., Zhang, Z. & Chen, B. Achieving high performance metal-organic framework materials through pore engineering. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 3362–3376 (2021).

Lin, R. B. et al. Molecular sieving of ethylene from ethane using a rigid metal-organic framework. Nat. Mater. 17, 1128–1133 (2018).

Wang, A., Ma, Y. & Zhao, D. Pore engineering of porous materials: effects and applications. ACS Nano 18, 22829–22854 (2024).

Ji, Z., Wang, H., Canossa, S., Wuttke, S. & Yaghi, O. M. Pore chemistry of metal–organic frameworks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2000238 (2020).

Gong, L., Pal, S. C., Ye, Y. & Ma, S. Nanospace engineering of metal–organic frameworks for adsorptive gas separation. Acc. Mater. Res. 6, 499–511 (2025).

Cmarik, G. E., Kim, M., Cohen, S. M. & Walton, K. S. Tuning the adsorption properties of UiO-66 via ligand functionalization. Langmuir 28, 15606–15613 (2012).

Xing, S. et al. Rational fine-tuning of MOF pore metrics: enhanced SO2 capture and sensing with optimal multi-site interactions. Adv. Funct. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202503013 (2025).

Hu, Z. et al. Combination of optimization and metalated-ligand exchange: an effective approach to functionalize UiO-66 (Zr) MOFs for CO2 separation. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 17246–17255 (2015).

Zhao, X., Bu, X., Zhai, Q.-G., Tran, H. & Feng, P. Pore space partition by symmetry-matching regulated ligand insertion and dramatic tuning on carbon dioxide uptake. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 1396–1399 (2015).

Hao, M. et al. Pore space partition synthetic strategy in imine-linked multivariate covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 1904–1913 (2023).

Brozek, C. & Dincă, M. Cation exchange at the secondary building units of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 5456–5467 (2014).

Yao, J. et al. Boosting trace SO2 adsorption and separation performance by the modulation of the SBU metal component of iron-based bimetal MOFs. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 14728–14737 (2023).

Kalmutzki, M. J., Hanikel, N. & Yaghi, O. M. Secondary building units as the turning point in the development of the reticular chemistry of MOFs. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat9180 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Tuning metal-organic framework (MOF) topology by regulating ligand and secondary building unit (SBU) geometry: structures built on 8-connected M(6) (M = Zr, Y) clusters and a flexible tetracarboxylate for propane-selective propane/propylene separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21702–21709 (2022).

Xia, H. L. et al. Customized synthesis: solvent- and acid-assisted topology evolution in zirconium-tetracarboxylate frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 61, 7980–7988 (2022).

Millange, F. et al. Time-resolved in situ diffraction study of the solvothermal crystallization of some prototypical metal–organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 763–766 (2010).

Cheetham, A. K., Kieslich, G. & Yeung, H. H. Thermodynamic and kinetic effects in the crystallization of metal-organic frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 659–667 (2018).

Basnayake, S. A., Su, J., Zou, X. & Balkus, K. J. Jr Carbonate-based zeolitic imidazolate framework for highly selective CO2 capture. Inorg. Chem. 54, 1816–1821 (2015).

Du, S. et al. Probing sub-5 Ångstrom micropores in carbon for precise light olefin/paraffin separation. Nat. Commun. 14, 1197 (2023).

Wang, S. M., Shivanna, M. & Yang, Q. Y. Nickel-based metal-organic frameworks for coal-bed methane purification with record CH4 /N2 selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201017 (2022).

Myers, A. L. & Prausnitz, J. M. Thermodynamics of mixed-gas adsorption. AIChE J. 11, 121–127 (1965).

Chen, Y. et al. Ultramicroporous hydrogen-bonded organic framework material with a thermoregulatory gating effect for record propylene separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17033–17040 (2022).

Liang, B. et al. An ultramicroporous metal-organic framework for high sieving separation of propylene from propane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 17795–17801 (2020).

Zeng, H. et al. Orthogonal-array dynamic molecular sieving of propylene/propane mixtures. Nature 595, 542–548 (2021).

Cadiau, A., Adil, K., Bhatt, P., Belmabkhout, Y. & Eddaoudi, M. A metal-organic framework–based splitter for separating propylene from propane. Science 353, 137–140 (2016).

Tian, Y.-J. et al. Pore configuration control in hybrid azolate ultra-microporous frameworks for sieving propylene from propane. Nat. Chem. 17, 141–147 (2024).

Deng, Z. et al. Green and scalable preparation of an isomeric CALF-20 adsorbent with tailored pore size for molecular sieving of propylene from propane. Small Methods 9, e2400838 (2024).

Geng, S. et al. Bioinspired design of a giant [Mn86] nanocage-based metal-organic framework with specific CO2 binding pockets for highly selective CO2 separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202305390 (2023).

Lv, D. et al. Ultrahigh CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 adsorption selectivities on a cost-effectively L-aspartic acid based metal-organic framework. Chem. Eng. J. 375, 122074 (2019).

Gu, Y.-M. et al. A two-dimensional stacked metal-organic framework for ultra highly-efficient CO2 sieving. Chem. Eng. J. 449, 137768 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Immobilization of H2O in diffusion channel of metal–organic frameworks for long-term CO2 capture from humid flue gas. Adv. Mater. 37, 2410500 (2025).

Jin, Y. et al. Ultra-high purity and productivity separation of CO2 and C2H2 from CH4 in rigid layered ultramicroporous material. ACS Cent. Sci. 10, 1885–1893 (2024).

Chen, K. J. et al. Tuning pore size in square-lattice coordination networks for size-selective sieving of CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 128, 10424–10428 (2016).

Yang, L. et al. Anion pillared metal–organic framework embedded with molecular rotors for size-selective capture of CO2 from CH4 and N2. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 3138–3144 (2019).

Nuhnen, A. & Janiak, C. A practical guide to calculate the isosteric heat/enthalpy of adsorption via adsorption isotherms in metal-organic frameworks, MOFs. Dalton Trans. 49, 10295–10307 (2020).

Burd, S. D. et al. Highly selective carbon dioxide uptake by [Cu(bpy-n)2(SiF6)] (bpy-1 = 4,4′-bipyridine; bpy-2 = 1,2-Bis(4-pyridyl)ethene). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3663–3666 (2012).

Gao, Q., Zhao, X.-L., Chang, Z., Xu, J. & Bu, X.-H. Structural stabilization of a metal–organic framework for gas sorption investigation. Dalton Trans. 45, 6830–6833 (2016).

Li, H.-P. et al. Tuning the pore surface of an ultramicroporous framework for enhanced methane and acetylene purification performance. Inorg. Chem. 59, 16725–16736 (2020).

Saha, D., Bao, Z., Jia, F. & Deng, S. Adsorption of CO2, CH4, N2O, and N2 on MOF-5, MOF-177, and zeolite 5A. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 1820–1826 (2010).

Chen, D.-L., Shang, H., Zhu, W. & Krishna, R. Reprint of: transient breakthroughs of CO2/CH4 and C3H6/C3H8 mixtures in fixed beds packed with Ni-MOF-74. Chem. Eng. Sci. 124, 109–117 (2015).

Yu, C. et al. Selective capture of carbon dioxide from humid gases over a wide temperature range using a robust metal–organic framework. Chem. Eng. J. 405, 126937 (2021).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133 (1965).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Zabinsky, S., Rehr, J., Ankudinov, A., Albers, R. & Eller, M. Multiple-scattering calculations of X-ray-absorption spectra. Phys. Rev. B 52, 2995 (1995).

Liu, P. et al. Immobilization of Lewis basic sites into a quasi-molecular-sieving metal–organic framework for enhanced C3H6/C3H8 separation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2406664 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Tailor-made microporous metal-organic frameworks for the full separation of propane from propylene through selective size exclusion. Adv. Mater. 30, e1805088 (2018).

Yu, L. et al. Pore distortion in a metal-organic framework for regulated separation of propane and propylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 19300–19305 (2021).

Lv, D. et al. Highly selective separation of propylene/propane mixture on cost-effectively four-carbon linkers based metal-organic frameworks. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 51, 126–134 (2022).

Huang, Y. et al. Delicate softness in a temperature-responsive porous crystal for accelerated sieving of propylene/propane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 24425–24432 (2023).

Tian, Y. J. et al. Pore configuration control in hybrid azolate ultra-microporous frameworks for sieving propylene from propane. Nat. Chem. 17, 141–147 (2024).

Xie, Y. et al. Optimal binding affinity for sieving separation of propylene from propane in an oxyfluoride anion-based metal-organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2386–2394 (2023).

Humby, J. D. et al. Host–guest selectivity in a series of isoreticular metal–organic frameworks: observation of acetylene-to-alkyne and carbon dioxide-to-amide interactions. Chem. Sci. 10, 1098–1106 (2019).

Li, N. et al. Specific K+ binding sites as CO2 traps in a porous MOF for enhanced CO2 selective sorption. Small 15, 1900426 (2019).

Chand Pal, S., Krishna, R. & Das, M. C. Highly scalable acid-base resistant Cu-Prussian blue metal-organic framework for C2H2/C2H4, biogas, and flue gas separations. Chem. Eng. J. 460, 141795 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Optimized pore nanospace through the construction of a cagelike metal–organic framework for CO2/N2 separation. Inorg. Chem. 62, 8058–8063 (2023).

Fan, L. et al. A series of metal–organic framework isomers based on pyridinedicarboxylate ligands: diversified selective gas adsorption and the positional effect of methyl functionality. Inorg. Chem. 60, 2704–2715 (2021).

Li, Y.-Z. et al. A moisture stable metal-organic framework for highly efficient CO2/N2, CO2/CH4 and CO2/CO separation. Chem. Eng. J. 484, 149494 (2024).

Tu, S. et al. Efficient CO2 capture under humid conditions on a novel amide-functionalized Fe-soc metal–organic framework. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 12240–12247 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Ultramicroporous zinc-aminotriazole MOF with customized alkaline pore environments for highly efficient capture of CO2 from flue gas. Chem. Eng. J. 498, 155338 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22478251 to H.W. and 22308238 to L.W.) and the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (202403021212044 to J. Liu) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W., H.W., and J.Li conceived the idea and supervised the project. J.Liu and Q.B. synthesized the compounds and conducted the characterization. J. Liu, T.L., X.B., and J.M. performed the gas separation test and analysis. J.Liu and L.W. wrote the first draft. H.W. revised the manuscript, and all authors participated in the discussion of the results and made comments on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yuzhu Ma, Yingxiang Ye, Weishen Yang, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Li, T., Bu, Q. et al. Temperature-regulated synthesis of carbonate-pillared zinc-triazolate frameworks for precise molecular recognition. Nat Commun 16, 11424 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66346-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66346-y