Abstract

The contribution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet to barystatic sea-level rise could be as high as eight metres around 2300 but remains deeply uncertain. Ice sheet retreat causes bedrock uplift, which can exert a stabilising effect on the grounding line. Yet, sea-level projections exclude bedrock adjustment, use simplified Earth structures or omit the uncertainty in climate response and Earth structure. We show that the grounding line retreat is delayed by 50 to 130 years and the barystatic sea-level contribution reduced by 9–23% when the heterogeneity of the solid Earth is included in a coupled ice – bedrock model under different emission scenarios till 2500. The effect of the solid Earth feedback in ice sheet projections can be twice as large as the uncertainty due to differences between climate models. We emphasise that realistic Earth structures should be considered when projecting the Antarctic contribution to barystatic sea-level rise on centennial time scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) has been identified as a critical tipping element, with its potential collapse being triggered if certain temperature thresholds are surpassed1. The contribution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet to barystatic sea-level rise over the coming centuries could be as high as eight metres around 2300, but contains an uncertainty in the order of metres1,2. Barystatic sea-level change is the change in the global mean sea level caused by adding or removing water mass to or from the ocean and is referred to in the remainder of this study solely by sea level change3. These uncertainties in sea-level rise have been partly attributed to unaccounted feedbacks between ice dynamics and the other components of the Earth system4. Among these, bedrock deformation due to future ice mass loss has been suggested to exert a stabilising effect on the ice sheet5,6, which depends on regional solid Earth properties7. This dependence has traditionally not been included in projections of ice sheet evolution8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. We integrate a heterogeneous solid Earth structure into an ice dynamic model to quantify the impact of the solid Earth effect on Antarctic ice retreat over the next 500 years under different global warming scenarios.

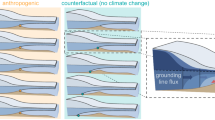

As an ice sheet melts, the load exerted on the underlying bedrock decreases (Fig. 1). Deformation in the Earth’s crust and mantle results in the uplift of the bedrock surface (brown lines in Fig. 1). This process is called glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA). A critical indicator of ice sheet stability is the retreat of the grounding line, which marks the transition between a grounded ice sheet and its fringing ice shelves21,22,23. As shown in Fig. 1, a retreat of the grounding line from its initial position purely due to ice shelf melt is partly counteracted by an accompanying bedrock uplift. As a consequence, the solid Earth response has the potential to slow down future grounding line retreat, giving rise to a negative feedback7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. In addition, the bedrock uplift can have an impact on ice sheet elevation, bedrock slope and water depth below the ice shelf which control basal melt rates. Finally, a decrease in ice mass leads to a reduction in the self-gravitation effect of the ice sheet, which results in a sea-level drop in its vicinity and a sea-level increase far away from it9.

The solid purple and brown lines represent the initial ice sheet/shelf and lithosphere, respectively. The lower solid brown line separates the elastic lithosphere and the viscoelastic mantle. The solid and dashed blue lines represent sea level before and after ice sheet melt and GIA, respectively. p1 is the initial grounding line position. The dashed purple line represents the ice sheet/shelf after retreat, while the dashed brown lines are the perturbed mantle elevation and bedrock surface. p is the expected grounding line position after retreat without considering any GIA effects. p2 is the grounding line position, including the GIA response. h1 is the initial surface elevation, h the surface elevation without GIA effects and h2 the surface elevation after the GIA response. Bedrock slope, λ, changes from λ1 to λ2 due to the bedrock response. b1 and s1 are the water depth and sea level, respectively, before GIA, while b2 and s2 are their counterparts after GIA. Modified from van Calcar et al.45.

The deformation of the solid Earth depends on changes in ice loading and the local mantle viscosity, which controls the response time of the bedrock. Several regions in West Antarctica, such as the Amundsen Sea Embayment, overlie relatively weak mantle structures where the mantle relaxes within decades to centuries24,25,26. Conversely, East Antarctica mostly consists of an old craton underlain by colder mantle, with response times that could reach beyond tens of thousands of years25. Thus, there is a large difference to be expected between the dynamical responses of the bedrock in West and East Antarctica to ice load variations. Current projections of the Antarctic Ice Sheet based on ice dynamical models typically use a rigid Earth structure, meaning the solid Earth does not deform14,18, implement a fixed bedrock response time based on the physically simplified so-called Elastic Lithosphere Relaxed Asthenosphere (ELRA) model12,14,17,20, use a variety of simplified representations of the Earth’s structure8,9,14,15, or when they do include lateral variations in the Earth’s structure, they do not explore the uncertainty range of lateral variations in the Earth’s structure and uncertainty in climate response to a given emission scenario7.

Studies comparing different radially varying Earth structures (hereafter called 1D Earth structures) have shown that ice sheet dynamics are sensitive to the choice of Earth structure, and emphasised the need for including heterogeneity in the Earth’s composition[]. Using a laterally varying relaxation time in an ELRA model resulted in a significant stabilising effect on the WAIS on multicentennial-to-millennial timescales for varying future emission scenarios16. However, in Coulon et al.16, the relaxation time is prescribed and constant over time, whereas in reality the relaxation time varies as it depends on the evolving size of the ice sheet and the associated mantle viscosity change with depth27,28.

Previous research has shown that a radially and laterally varying Earth structure (hereafter called 3D Earth structure) might not only lead to a reduction of the sea-level rise29, but also cause an increase in the contribution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet to far-field sea-level due to the water expulsion effect of uplifting regions30,31. However, in those studies, the ice sheet evolution is predefined rather than dynamically modelled, and any stabilising effects on grounding line migration and other ice sheet processes are therefore not accounted for.

Recent work incorporating lateral Earth structure variations on a dynamically modelled ice sheet evolution has demonstrated significant stabilisation of the Antarctic Ice Sheet7, but this finding is based on only a single climate model and Earth structure. Different climate models exhibit warming patterns in different regions between which the Earth structure varies, yielding a different response as observed Supplementary Fig. 1. Furthermore, the mantle viscosity for the 3D Earth structure is derived here, from seismic and geologic information on the structure of the Antarctic mantle, which exhibits large uncertainties leading to significantly different bedrock responses26. Assuming only a single Earth structure does not take the uncertainties into account. Finally, the mantle rheology is assumed to deform by a linear relation between stress and strain rate, whereas laboratorial experiments have shown that viscosity is stress-dependent for certain mantle conditions and deformation mechanisms32. In simulations for century-scale ice loss in the Amundsen Sea Embayment based on the laboratory-derived flow laws, the mantle viscosity can drop by an order of magnitude due to changes in stress.

Here, we quantify the stabilising effect of the nonlinear response of multiple 3D Earth structures on the Antarctic Ice Sheet. We employ a coupled ice-sheet—GIA model that incorporates 3D mantle viscosities (“Methods”) to simulate the Antarctic Ice Sheet evolution up to the year 2500 under two global warming scenarios: the low emission shared socio-economic pathway SSP1-2.6 and the high emission SSP5-8.5. For both scenarios, we force our simulations with products from two different climate models (“Methods”) to be able to compare the uncertainty in the choice of the climate model with the uncertainties in the GIA component. Finally, we assess the impact of this finding by comparing the sea-level contribution using different 3D Earth structures to the sea-level contribution using the currently used 1D and ELRA models. We thereby quantify the separate contributions of bedrock deformation and local sea-level fall due to self-gravitation.

Results and discussion

Sea-level rise reduction through bedrock uplift

The Earth structure can be inferred from seismic measurements when adopting experimental flow laws for mantle rock under the assumption of different parameters, such as water content and grain size in the Earth’s mantle. We varied the grain size and water content in the mantle to obtain two different 3D Earth structures, a stronger (hereafter called 3D Stronger) and a weaker (hereafter called 3D Weaker) structure (Supplementary Fig. 2). The Earth structures are based on seismic models and mantle flow laws and both result in local mantle viscosities that are close to those from regional studies of GIA due to past ice sheet variations24,33,34,35 (“Methods”). In the simulations presented here, the mantle viscosity is locally up to 3 orders of magnitude lower between present day and 2500 as a result of the ice load changes, since the viscosity in the Earth’s interior is nonlinearly related to stress (Supplementary Fig. 3). Using 3D Weaker leads to a reduction in sea-level rise of up to 23% in 2500 compared to the rigid Earth (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1). This corresponds to a sea-level rise reduction of 1 m. 3D Stronger results in less bedrock uplift compared to the 3D Weaker due to its higher mantle viscosity, but still reduces sea-level rise by up to 14% compared to a rigid Earth (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

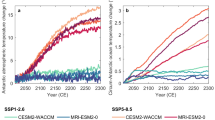

The barystatic sea-level contribution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet relative to present day using a rigid and the 3D Weaker structure for two different climate models (CESM and IPSL) and two different emission scenarios (SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5, panel a). Dashed lines correspond to using a rigid Earth and solid lines to the use of a 3D Earth structure. Red and orange lines correspond to scenario SSP5-8.5, and light and dark green lines to scenario SSP1-2.6. Panel (b) shows the absolute difference between the use of a 3D Earth structure and a rigid Earth structure when forcing from IPSL is applied (dashed lines) and the absolute difference between applying forcing from CESM and IPSL using a rigid Earth structure (dotted lines). IPSL contains warming mainly in the Amundsen Sea, and CESM contains warming mainly in the Weddell Sea.

Besides the 3D Earth structures and the rigid Earth, we also applied a commonly used 1D Earth structure with an upper mantle viscosity of 1021 Pa·s, and the ELRA model with a commonly used relaxation time (“Methods”). The 1D and ELRA models exert a smaller stabilising effect on the ice sheet than both 3D structures (Supplementary Fig. 4) since the 1D and ELRA models do not consider the weak zones in the Earth’s mantle that deform faster and provide more stability to the ice sheet. In agreement with previous studies, we found negligible differences in sea-level contribution between the ELRA model and the commonly used 1D Earth structure8,11,17. However, their impact had not been directly compared to that of a 3D Earth structure. Our results show that the 3D Stronger model reduces sea-level rise by up to 10%, and the 3D Weaker model by up to 20%, relative to the response from the 1D Earth structure and ELRA (Supplementary Fig. 4). Current projections using simplified Earth models might therefore overestimate sea-level rise over the next centuries.

Bedrock uplift delays ice sheet retreat

The solid Earth response to ice mass loss differs regionally due to the lateral variability of the Earth’s structure in combination with the location of ice sheet retreat. In Antarctica, present trends in ice mass loss are dominated by melt and discharge at the base and front of ice shelves36,37, which in turn can lead to an acceleration of upstream flow through reduced buttressing38,39,40. In our simulations, mass loss is strongly dependent on spatial and temporal variations in the ocean temperatures driving sub-shelf melt rates. This forcing is taken from a climate model (“Methods”) that exhibits particularly strong ocean warming in the Amundsen Sea Embayment (location indicated by AS in Fig. 3). The largest retreat therefore initiates from the Thwaites ice shelf in the Amundsen Sea Embayment, where the grounding line migrates hundreds of kilometres inland over approximately 350 years (Fig. 3). Here, this migration is strongly dependent on the choice of Earth structure, with the rigid Earth model showcasing a grounding line position up to 180 km further inland compared to 3D structures by year 2500. The latter provides up to 160 m of bedrock uplift over 500 years, slowing down the retreat. As a result, the grounding line positions reached by the 3D Weaker and Stronger structures in 2500 have been already reached by the rigid Earth by 2370 and 2420, respectively. Thus, 3D Earth structures delay grounding line retreat by 80–130 years (Supplementary Table 2).

The ice thickness of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet in years 2300, 2400 and 2500 using the 3D Weaker Earth structure and IPSL forcing under the low emission scenario SSP1-2.6 (panel a–c). AS in panel (a) indicates the Amundsen Sea, and WS indicates the Weddell Sea. Panel (d–f) show the ice thickness difference between using the 3D Weaker structure and the rigid Earth structure. Panel (g–i) show the difference in bedrock elevation between the application of the 3D Earth structure and the rigid Earth structure. IPSL corresponds to the climate model with most of the warming in the Amundsen Sea (“Methods”).

Acknowledging the significant uncertainties in ocean temperature variations between climate models20, which can include dissimilarities in the regions where ocean warming occurs, we run an experiment employing a different climate model that exhibits a strong warming in the Weddell Sea area instead of the Amundsen Sea (“Methods”). This choice initiates a retreat of the grounding line of the Ronne Ice Shelf region, leading to a significant mass loss and accompanying solid Earth rebound (Supplementary Fig. 5). In this region, and compared to a rigid Earth model, the use of 3D structures results in a delay of grounding line retreat by 50–70 years (Supplementary Table 2). This smaller impact and sensitivity of this region relative to the retreat modelled for the Amundsen Sea Embayment can be explained by the mantle viscosity in the Ronne Ice Shelf region, which is up to 2 orders of magnitude higher than that in the Amundsen Sea Embayment. The same holds in other regions with significant grounding line retreat, the Ross Ice Shelf and Wilkes Subglacial Basin (indicated by RS and WB in Supplementary Fig. 6a), where the mantle viscosity is higher in combination with a relatively small amount of ice mass loss compared to the Amundsen Sea Embayment. Even though there are relatively low viscosity regions at the grounding line of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, the grounding line is stable, because the climate warming is not strong enough to initiate a retreat in those regions on the time scales considered in the framework of the used climate models, except for the Wilkes Subglacial Basin, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6.

Although the uncertainties embedded in climate projections resulting from the use of output of different climate models as forcing in the ice sheet model can have a significant effect on the resulting sea-level contribution, we found that in the low emission scenario, even greater impact can arise from the choice of an Earth structure model. For example, the difference in modelled sea-level rise between rigid Earth simulations using two different climate models can reach 16% (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3). However, when warming occurs in the Amundsen Sea Embayment, the use of a 3D Weaker Earth structure can result in a reduction of 23% in the projected sea-level rise relative to its rigid-Earth counterpart (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Tables 1 and 3) due to delayed grounding line retreat fuelled by a relatively low mantle viscosity and quick bedrock uplift response.

The bedrock adjustment stabilises the ice sheet and reduces ice mass loss. The peak basal mass loss of 2.2·104 Gt/yr is reached around the years 2100 and 2240, corresponding to periods with the highest sub-shelf ocean temperatures (Fig. 4a and c). From 2250, basal melt rates decrease in the 3D-Earth structure experiments. The total basal mass loss is determined by the area of the ice shelves and the temperature at the depth of the shelf base. The ice shelf area is defined by the positions of the grounding line and the calving front. In the ice sheet model, calving occurs when the thickness of the ice shelf at the calving front is smaller than 100 m. The position of the calving front and the ice thickness at the front is similar between the rigid Earth and the 3D simulations because the effect of GIA on the ice thickness at the calving front is neglectable. Therefore, different calving schemes could produce more or less calving, but the calving front is expected to remain at the same location in both the 3D-Earth and rigid-Earth runs. In contrast, GIA directly affects the grounding-line position. The position of the grounding line differs significantly, by hundreds of kilometres, leading to a significant difference in ice shelf area between the rigid and the 3D Earth (Fig. 4b).

On the one hand, the total ice shelf area is smaller in the case of a 3D Earth because of the slower grounding line retreat, which decreases basal mass loss compared to a rigid Earth (Fig. 4b). On the other hand, the mean ice shelf thickness increases somewhat resulting in a draft in contact with warmer water, which increases basal melt rates (Fig. 4c). The effect of the decrease in ice shelf area is larger than the effect of shelf base depth. Hence, the main mechanism behind the stabilising effect is the reduction of ice shelf area growth due to delayed grounding line retreat.

The total sub-shelf basal melt rate and total ice shelf area when using a rigid Earth and a 3D Earth structure are shown in panel (a, b), respectively. Panel (c, d) show the mean ocean temperature and ice thickness over a subset of the ice shelf cells. This subset consists of all cells that are floating, at any given time, in both the rigid-Earth and the 3D-Earth structure simulations. Results are shown only for the experiments driven by IPSL forcing, but they are qualitatively similar under CESM forcing.

Implications for ice sheet projections

This study provides a significant advance by quantifying the impact of bedrock deformation relative to one of the largest sources of uncertainty in Antarctic sea-level projections: the choice of climate model. Furthermore, by incorporating a 3D GIA model with nonlinear mantle rheology, we improve upon traditional assumptions and evaluate the sensitivity of ice sheet evolution to Earth structure for the latest SSP scenarios. We compare our 3D GIA model to the commonly used ELRA and 1D GIA models. Finally, we isolate the separate contributions of bedrock deformation and local sea-level fall due to self-gravitation, which we will discuss in this section, together with the other implications of our results.

The timing and magnitude of ice mass loss determine the bedrock response, which in our experiments have been the result of a projected climate warming based on the low-emission SSP1-2.6. In order to account for the uncertainty in projected climate pathways, we also studied the effect of GIA for the high emission SSP5-8.5. We found that the emission scenario is the most important factor determining future sea-level rise, followed by the effect of bedrock deformation and the choice of climate model. By year 2500, sea-level rise is reduced by 29–59% under the low emission scenario compared to the high emission scenario, dependent on the combination of chosen climate model and 3D Earth structure (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 4). Using 3D Weaker instead of a rigid Earth reduces the sea-level contribution from Antarctica by 16–23% (0.7–1 m) under the low-emission scenario, and 12–17% (0.8–1.3 m) under the high emission scenario, dependent on the climate model (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 1). Some studies7,11 present a possible stronger reduction of sea level rise by fast bedrock uplift, but such strong reductions in sea level rise are only found when strong East Antarctic Ice Sheet retreat is occurring due to the inclusion of marine ice cliff instability, which is disputed41. In addition, we show that the widely used ELRA model and 1D Earth models with a relaxation time of 3000 years and an upper mantle viscosity of 1021 Pa·s, respectively, systematically underestimate the stabilising effect of bedrock uplift. The reduction of sea level rise when using these models is only 2–3% for the low emission scenario, and 3–5% for the high emission scenario, dependent on the climate model and Earth model.

Under the high emission scenario, the grounding line retreat leads to a WAIS collapse for both climate models, and the grounding line reaches the same position in 2500, independent from the Earth structure and climate model. The delay in grounding line retreat due to the 3D Earth structure is only 20–30 years, dependent on the Earth structure and climate model, because the bedrock uplift is too slow compared to the fast rate of ice loss under the high emission scenario. This stands in contrast to the results of the low emission scenario presented above, with up to 130 years of delay in grounding line retreat caused by the use of a weak 3D Earth structure. This can be explained by a much slower ice sheet retreat under the lower emission scenario, where the bedrock uplift is fast enough to stabilise the ice sheet. Thus, our results indicate that the impact of a 3D Earth structure is smaller for a high emission scenario than for a low emission one because, under a strong ocean warming, a collapse of WAIS cannot be prevented by bedrock uplift, supporting the findings of other studies using simpler ELRA and 1D Earth structures10,16, and a 3D Earth structure7.

To varying degrees, our experiments show that bedrock adjustment provides a stabilising effect in all configurations: the sea-level contribution using both 3D Earth structures is reduced at any time, relative to using a rigid Earth structure for all scenarios and applied climate models. Overall, we find that the delay in grounding line retreat for the WAIS covers a total range of 50–130 years among all combinations of Earth structure, the climate model and the emission scenario tested in our study.

The negative feedback of GIA on ice dynamics is not only caused by bedrock uplift. The ice mass change in combination with bedrock adjustment affects the gravitational potential surface that the sea level would follow when at rest, called the geoid. An increase of ice mass and bedrock elevation raises the geoid. Previous research that used a 1D Earth model included the self-gravitational effect of the ice sheet on the sea level and found that the near-field sea-level fall is the limiting factor of the retreat9,10, although these studies did not separate the effect of bedrock uplift and the effect of the self-gravitation of the ice sheet on sea level. Other studies, also including the self-gravitational effect of the ice sheet, have shown the bedrock uplift to be the dominant factor of the stabilising effect of the solid Earth13,16. The latter used a lower viscosity than the previously mentioned studies using a 1D Earth model, which could lead to faster bedrock uplift for a similar ice mass loss. Apart from the change in gravitational potential, the sea level will be affected by the contribution from the Greenland Ice Sheet, glaciers, land-water storage, and thermal expansion1. In our main results, the sea level is assumed to be spatially uniform and constant in time. We investigated the impact of this assumption on ice sheet dynamics by implementing a spatially and temporally varying sea-level where the geoid is computed by the GIA model with the Antarctica forcing using the 1D Earth structure, and the contribution from all other sources is added assuming it is uniform (“Methods”). We found that grounding line retreat in West Antarctica is delayed even further by about 20 years due to a local sea-level drop that peaks at 8 m. The ice thickness is regionally up to 500 m thicker and the total ice volume loss decreases by 5% in 2500 when regional sea-level variations are included in 2500 compared to keeping sea level fixed at present day (Supplementary Fig. 7). The local sea-level drop due to the effect of self-gravitation is significantly smaller than the bedrock uplift which occurs in the order of hundred metres in 2500. Hence, our results suggest that the main stabilising effect of GIA on Antarctic Ice Sheet evolution is through bedrock uplift, and local variations in the sea-level surface represent a smaller effect.

While our results demonstrate that GIA can play a role comparable to variations in climate response for a particular emission scenario, further work is needed to constrain sea level projections. Since 3D simulations are computationally expensive, simulations in this study share a large set of ice model parameters. This implies that for a complete characterisation of the model spread a wider region of the model parameter space should be explored, as well as variations in the methods to compute calving and basal hydrology, and the initialisation method. Since intercomparison experiments suggest that the uncertainty due to the choice of ice sheet model is in the order of several metres by 2300, experiments with other ice sheet models are also needed2.

The modelling setup in this study assumes an Earth in isostatic equilibrium at the start of the simulation and does not take into account already ongoing bedrock uplift at the present day. The bedrock displacement due to past ice mass loss should therefore be added to the projected bedrock displacement, which could potentially increase the stabilisation effect on ice dynamics. However, observed present-day uplift rates are, for example at the Amundsen Sea Embayment, in the order of tens of millimetres per year24, which is considerably lower than projected uplift rates in the order of tens of centimetres per year around 2400 under strong warming, even though GNSS observations of bedrock deformation are sparse and other regions of relatively fast uplift at present-day might be uncovered. Furthermore, the ice sheet model is calibrated to a present-day equilibrium state, which underestimates projected ice mass loss in areas with already ongoing ice loss, such as the Amundsen Sea Embayment42,43. The grounding line in this region is projected to retreat by 45 km over 500 years when including present-day mass changes under current climate conditions40. Taking into account present-day mass changes would enhance the effect of bedrock deformation on timescales shorter than 300 years, but the retreat is significantly less than the retreat projected under the applied emission scenarios, even in the low emission scenario. To improve the accuracy, future research on sea level projections should include an ice model that is initialised, including ongoing bedrock deformation and ice mass loss.

Finally, dissimilarities between different 3D Earth structures could be constrained if there would be more data on mantle viscosity. Improvements in seismic and geodetic infrastructure, as well as geologic findings, are instrumental in constraining mantle viscosity. Furthermore, we show that the commonly used 1D Earth structure and ELRA model are significantly overestimating sea level change compared to using a 3D Earth structure. Other 1D structures and relaxation times might be able to approximate the effect of a 3D structure on the barystatic sea level contribution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet44.

Despite the uncertainties, our results reinforce the notion that the solid Earth feedback cannot stop the fate of WAIS and the associated sea-level rise in the case of a high emission scenario, which argues for strong mitigation measures. If a low-emission scenario were to be followed, bedrock uplift significantly delays ice sheet retreat.

Methods

The model developed for this study is a coupled ice sheet – 3D GIA model developed for the last glacial cycle in van Calcar et al.45 and adjusted for this study to simulate future ice sheet evolution. We used the ice sheet model IMAU-ICE46 and a GIA finite element (FE) model45.

Ice sheet model

IMAU-ICE combines the shallow ice and the shallow shelf approximations to compute velocities of ice flow46,47,48on a 16 km grid resolution. The present-day geometry for ice and bedrock topography is taken from Bedmachine version 349. The surface mass balance is computed by a temperature and radiation parameterisation46. The basal sliding is determined according to the regularised Coulomb law50. The geothermal heat flux is taken from Shapiro and Ritzwoller51. Basal melt at the ice shelf is computed using the Favier quadratic method52. Calving is computed using the threshold-calving approach with a threshold of 100 m46. A detailed model description of IMAU-ICE can be found in Berends et al.46.

The barystatic sea level contribution is computed based on the volume above flotation following Eq. 153.

The volume above flotation is denoted by \({V}_{{af}}\), H is the ice thickness, b is the bedrock elevation, \({\rho }_{{ocean}}\) and \({\rho }_{{ice}}\) the density of water and ice, respectively, A is the area of the gridcell, and n the gridcell number. The sea level equivalent (SLE) is then computed using

The ocean area (\({A}_{{ocean}}\)) is assumed to be 3.611·1014 m2[54].

IMAU-ICE includes a module to compute bedrock surface deformation using the ELRA model. The ELRA model is a simplified representation of Earth’s viscoelastic response to surface loading changes54, commonly used in ice sheet models. It conceptualises the lithosphere as an elastic shell and the underlying asthenosphere as a uniform medium with a characteristic relaxation time, capturing the delayed viscous response of the mantle without explicitly solving equations of motion. The bedrock response is described using a relaxation equation for the bedrock elevation h:

where \({h}_{{eq}}\) is the equilibrium bedrock height dictated by isostatic balance, and \(\tau\) is the relaxation timescale, assumed to be 3000 years54. This approach provides an efficient way to approximate bedrock deformation in ice sheet models while maintaining computational efficiency.

Calibration of the ice sheet model

The Antarctic Ice Sheet is calibrated to an equilibrium state at the present day. In there, the difference between observed and modelled ice thickness is minimised by adjusting the basal friction coefficient and ocean temperature over a period of 10,000 years. During this time, there are no vertical displacements of the bedrock such that the ice sheet is in equilibrium with the present-day bedrock topography at the end of the calibration. Present-day ocean temperature and salinity from the World Ocean Atlas55 are extrapolated into the sub-shelf cavities and taken as the initial value for the calibration56.

The total ice volume at the end of the calibration deviates 20 mm sea-level equivalent from the present-day observed ice volume. The 95th percentile of the absolute difference between the modelled ice thickness at the end of the calibration and the observed ice thickness (Bedmachine version 3) is 50 m (Supplementary Fig. 8). The modelled grounding line mostly coincides with the observed grounding line. Where that is not the case, the modelled grounding line lies more towards the ocean, and the deviation from the observed grounding line never exceeds 16 km. When run for 2000 years under constant climate and ocean conditions after the calibrated equilibrium state, the model shows a negligible model drift.

Forcing scenarios

The ocean temperature, salinity and atmospheric temperature anomalies, and precipitation ratios result from two climate models: CESM2-WACCM (hereafter called CESM) and IPSL-CM6A-LR (hereafter called IPSL) for IPCC scenario SSP5-8.5 and SSP1-2.6 (Supplementary Fig. 1)20. These two models were selected from the climate model intercomparison project CMIP6 since they are two of the few models providing projections until 230020,57. In the high emission scenario, the ocean temperature anomaly is smaller in CESM than in IPSL, with a maximum difference of 1.2 °C at 2300. In the low emission scenario, the ocean temperature anomaly in CESM is smaller than in IPSL until 2100 and larger from 2100 onwards, with a maximum difference of 0.3 °C in 2200.

Up to 2300, ocean temperature and salinity anomalies from the climate models are added to the inverted ocean temperature from the calibration and to the extrapolated salinity values from the World Ocean Atlas. Atmospheric temperature anomalies and precipitation ratios are added to the present-day observed climate taken from ERA558. Between 2300 and 2500, the forcing is kept constant at the value of 2300 since no data from climate models exist on these time scales8,20.

Coupling to the GIA model

The ice sheet model and the GIA model are coupled following the method by van Calcar et al. who applied the coupling method to the last glacial cycle45. The ice sheet model IMAU-ICE was adjusted to output ice loading such that it can be used by an external GIA model and to use bedrock deformation provided by an external GIA model.

The total simulation time of 500 years is divided over coupling time steps of 5 years. The coupling time step is the time over which IMAU-ICE is run before the output is passed on to the GIA model and in turn, the time over which the GIA model is run before the output is passed back to IMAU-ICE. The coupling method is based on the following procedure. First, the ice sheet model is run over a period of 5 years using a smaller time step that varies between 1 month and 2 years. The resulting change in ice load is used as input for the GIA model, which is then run for the same period as IMAU-ICE. The GIA model uses time steps varying between hours and months to simulate the 5-year period. The GIA model provides the total bedrock deformation over the 5-year period, linearly interpolated to the time steps in IMAU-ICE. This deformation is then used to run the ice sheet model again for the same period. Then, the ice model moves on to the next period.

The coupling timestep can be chosen as short as needed because our method allows to stop the computation, save all important variables, and restart at any time step. We tested the effect of coupling time steps of 20, 10, 5 and 3 years. The effect of the length of the coupling time step and the number of coupling iterations on the total ice volume is in the order of mm sea level equivalent. The difference in ice thickness between a 5 and a 3 year coupling time step is 120 m on a small scale of approximately 1000 km2 (Supplementary Fig. 9). The shorter the coupling time step, the more time steps need to be performed to simulate 500 years in total. Each coupling time step has approximately the same runtime, independent of the length of the coupling time step.

We also tested the impact of running IMAU-ICE twice over the same time step as described above, where the second time includes the deformation computed by the GIA model over that same time step. The difference in ice thickness between iterating or not iterating for a 5 year coupling time step is 250 m on a small scale of approximately 1500 km2 (Supplementary Fig. 10). Iterating once over the coupling time step does not increase the computation time much since it only requires an extra simulation of the ice sheet model and not of the GIA model, whereas the GIA model is the main time consuming component. Our final choice is a coupling time step of 5 years with one iteration, which leads to a feasible runtime and acceptable differences with respect to smaller time steps and more iterations.

GIA model

The GIA model is developed by Blank et al.33 and adjusted for the coupling to an ice sheet model by van Calcar et al.45. The GIA model is a spherical model based on finite element software ABAQUS that can include self-gravity.

For this study, the GIA model contains a total of 9 layers with 1 layer for the core, 7 mantle layers and 1 surface layer. The lithospheric thickness follows from the assigned parameters determining the rheology and therefore varies locally and is not prescribed to follow a certain layer. The model is materially compressible, which includes compressible material but not the effect on buoyancy forces59. A et al.60 showed that present-day Antarctic uplift rates are reduced by about 5% when an incompressible model was used compared to a compressible model. The difference will be smaller for a material compressible model compared to a fully compressible model61. It is assumed that the Earth is in isostatic equilibrium at the present day.

In the main simulations, we exclude the effect of spatial variations in sea level to disentangle the effect between bedrock uplift and local sea-level variations. Due to the decrease in gravitational attraction of the shrinking ice sheet, the local sea level in a region around the ice sheet will drop. This will stabilise the ice sheet even further, besides the effect of bedrock uplift. In this study, we focus solely on the effect of bedrock uplift. However, we have tested the effect of including spatial variations in sea level. These are computed for each coupling time step as a result of bedrock deformation and changes in gravitational potential due to the ice load and the deformation using the GIA model. Then, background sea-level change is computed as the combination of projected contribution from thermal expansion and melt from Greenland, glaciers and land-water storage, which is then added to the sea-level variations (Table 5 in Supplementary Information). We assume that this contribution is uniform in space over Antarctica. This underestimates the contribution from Greenland because the actual sea-level contribution in Antarctica is higher due to the self-gravitational effect of the Greenland ice sheet. However, the effect of thermal expansion, Greenland glaciers and land-water storage on the local sea-level in Antarctica is small compared to the 8 m sea-level drop in Antarctica due to its loss of gravitational attraction (see main text).

The GIA model has a global resolution of 200 km and a higher resolution region of 30 km over Antarctica. Using a resolution of 15 km for Antarctica resulted in a negligible difference on ice volume and at most 6 metres difference in bedrock deformation (Supplementary Fig. 11), with significant larger computation time than using a resolution of 30 km. The viscoelastic bedrock response to changes in ice loading is a much smoother response than the change in ice loading itself. The resolution of IMAU-ICE is 16 km. Therefore, increasing the resolution of the GIA model without increasing the ice sheet model resolution is not useful. When the sea-level equation would have been solved, the topography should be included at high resolution separately from the resolution of the FE model, as done in Blank et al.33.

Including self-gravitation of the Earth in the GIA model has a negligible effect on ice volume change and results in a difference of 100 m in the ice thickness and 3 m in bedrock deformation on a local scale (Supplementary Fig. 12). However, including self-gravity doubles the computation time. We therefore decided to not include self-gravitation in the GIA model.

The GIA model used for this study does not include rotational effects. A change in Earth’s rotation caused by ice loss affects the equilibrium shape of the ocean surface and the deformation of the crust directly. This has been shown to be a significant effect in the far field sea level fingerprint of a West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse62. In our study, we don’t simulate the sea level fingerprint and only compute the sea level contribution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Signals are smaller for Antarctica due to its proximity to the rotational axis, where mass redistributions have a weaker influence on Earth’s rotation.

Earth structures

The projections are performed using three different Earth structures, one 1D structure and two 3D structures. The density and Young’s modulus are the same for each structure and shown in Table 1 in van Calcar et al.45. The 1D rheology contains an elastic lithospheric thickness of 100 km and an upper mantle viscosity 1021 Pa·s (hereafter referred to as 1D), similar other 1D GIA models for Antarctica8,9,11,14,15.

The 3D rheology of the mantle is computed using spatially varying seismic velocity anomalies from Lloyd et al.25 for Antarctica and from Becker and Boschi63 globally. The spatially varying mantle temperature can be derived from the seismic velocity anomalies, assuming seismic anomalies are caused by thermal anomalies64,65. The uncertainty rising from the interpretation of the seismic anomaly in terms of temperature and viscosity is taken into account by using different flow law parameters and constraining those with regional viscosity estimates65. The temperature, together with pressure for a hydrostatic Earth, is used to compute dislocation and diffusion parameters based on a flow law for olivine, as dislocation and diffusion creep are assumed to be the most important mantle deformation mechanisms66. The method to obtain dislocation and diffusion parameters from seismic velocities is discussed in van Calcar et al.45. As little information exists on grain size and water content, these parameters are kept spatially homogeneous67. To determine the water content and grain size, we consider three regions where significant ice mass loss occurs and for which the mantle viscosity is relatively well known from fitting different GIA models to GPS data, namely the Amundsen Sea Embayment with an upper mantle viscosity of 4·1018 Pa·s24, and the Weddell Sea Embayment and Palmer Land with a viscosity of 1-3·1020 Pa·s34,35,65. We computed the average mantle viscosity over depth intervals that align with these constraints and are considered sensitive to ice mass loss in each region. For the Amundsen Sea Embayment, Barletta et al.24 showed that both the shallow and deeper portions of the upper mantle, with a transition at ~ 200 km depth, respond to changes in ice loading. We therefore computed the average mantle viscosity between 150 and 250 km depth. To ensure the lithosphere was excluded from our calculation, we omitted viscosities above 1030 Pa·s. For the Weddell Sea and Palmer Land, mantle viscosity constraints are defined for the upper mantle between 120 and 660 km depth34,35. Accordingly, we calculated the average viscosity across the middle part of the upper mantle, from 350 to 450 km depth. All viscosity estimates were computed for a range of water contents from 0 to 800 ppm and grain sizes from 500 µm to 9.5 mm.

A characteristic stress of 0.1 MPa was used to compute the viscosities for each combination of water content and grain size65. The best fitted viscosity at the Amundsen Sea Embayment to the data is 5·1018 Pa·s with a water content of 800 ppm and a grain size of 2.5 mm. However, for this combination of parameters, the viscosity is approximately 1 and 1.5 orders of magnitude too low in the Weddell Sea Embayment and Palmer Land compared to their constraints, respectively. On the other hand, a water content of 400 ppm in combination with a grain size of 8.5 mm leads to the best fit viscosity of 3·1020 Pa·s for Palmer Land, but this leads to a viscosity in the Amundsen Sea Embayment of 1 and 0.5 orders of magnitude too high at the Amundsen Sea Embayment and the Weddell Sea Embayment, respectively. Even though the fit is very good for one of the regions, the combination of parameters leads to a large total misfit for the three regions together. To reduce the total misfit, we chose a combination that fits within half an order of magnitude at the Amundsen Sea Embayment and within one order of magnitude at the other regions, namely a water content of 400 ppm and a grain size of 2.5 mm (referred to as 3D Weaker). Furthermore, we chose a combination that fits within half an order of magnitude at the Weddell Sea and Palmer Land, and within one order of magnitude in the Amundsen Sea Embayment, namely a water content of 200 ppm and a grainsize of 4.5 mm (referred to as 3D Stronger). The average viscosities for each region for 3D Weaker and 3D Stronger are shown in Table 1. Both rheologies can be considered realistic based on other viscosity estimates and fit with GIA observations24,34,35,65. A water content of 400 ppm is within the range of water content found in Antarctic xenoliths68.

The mantle viscosities of the 3D experiments are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 at three depths. The 3D viscosities are up to 4 orders of magnitude lower at certain locations in West Antarctica and up to 3 orders of magnitude higher in East Antarctica compared to the 1D21 rheology. The viscosity of the 3D Stronger rheology is about 1 order of magnitude higher than the 3D Weaker rheology (Supplementary Fig. 3d–f).

Data availability

The data used in this study are available in the 4TU database under https://doi.org/10.4121/e7523ed4-c4ec-42a2-9522-66ae81313e38 [https://doi.org/10.4121/1adec1f9-7de4-4980-b4ee-f0e7a1ae436d]69.

Code availability

The source code used in this study is available in the 4TU database under https://doi.org/10.4121/1adec1f9-7de4-4980-b4ee-f0e7a1ae436d [https://doi.org/10.4121/e7523ed4-c4ec-42a2-9522-66ae81313e38]70.

References

Fox-Kemper, B. et al. Ocean, Cryosphere and sea level change. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2021).

Seroussi, H. et al. Evolution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet over the next three centuries from an ISMIP6 model ensemble. Earth’s Future, 12, e2024EF004561 (2024).

Gregory, J. M. et al. Concepts and terminology for sea level: mean, variability and change, both local and global. Surv. Geophys. 40, 1251–1289 (2019).

Fyke, J., Sergienko, O., Löfverström, M., Price, S. & Lenaerts, J. T. M. An overview of interactions and feedbacks between ice sheets and the Earth system. Rev. Geophys. 56, 361–408 (2018).

Whitehouse, P. L., Gomez, N., King, M. A. & Wiens, D. A. Solid Earth change and the evolution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Nat. Commun. 10, 503 (2019).

Greischar, L. & Bentley, C. Isostatic equilibrium grounding line between the West Antarctic inland ice sheet and the Ross Ice Shelf. Nature 283, 651–654 (1980).

Gomez, N. et al. The influence of realistic 3D mantle viscosity on Antarctica’s contribution to future global sea levels. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn1470 (2024).

Golledge, N. R. et al. The multi-millennial Antarctic commitment to future sea-level rise. Nature 526, 421–425 (2015).

Gomez, N., Pollard, D. & Holland, D. Sea-level feedback lowers projections of future Antarctic Ice-Sheet mass loss. Nat. Commun. 6, 8798 (2015).

Konrad, H. et al. Potential of the solid-Earth response for limiting long-term West Antarctic Ice Sheet retreat in a warming climate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 432, 254–264 (2015).

Pollard, D., Gomez, N. & DeConto, R. M. Variations of the Antarctic ice sheet in a coupled ice sheet-Earth-sea level model: Sensitivity to viscoelastic Earth properties. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 122, 2124–2138 (2017).

Bulthuis, K. et al. Uncertainty quantification of the multi-centennial response of the Antarctic ice sheet to climate change. Cryosphere 13, 1349–1380 (2019).

Kachuck, S. B., Martin, D. F., Bassis, J. N. & Price, S. F. Rapid viscoelastic deformation slows marine ice sheet instability at pine island glacier. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086446 (2020).

Levermann, A. et al. Projecting Antarctica’s contribution to future sea-level rise from basal ice shelf melt using linear response functions of 16 ice sheet models (LARMIP-2). Earth Syst. Dyn. 11, 35–76 (2020).

Rodehacke, C. B., Pfeiffer, M., Semmler, T., Gurses & Kleiner, T. Future sea level contribution from Antarctica inferred from CMIP5 model forcing and its dependence on precipitation ansatz. Earth Syst. Dyn. 11, 1153–1194 (2020).

Coulon, V. et al. Contrasting response of West and East Antarctic ice sheets to glacial isostatic adjustment. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf, 126, e2020JF006003 (2021).

DeConto, R. M. et al. The Paris Climate Agreement and future sea-level rise from Antarctica. Nature 593, 83–89 (2021).

Lipscomb, W. H. et al. ISMIP6-based projections of ocean-forced Antarctic Ice Sheet evolution using the Community Ice Sheet Model. Cryosphere 15, 633–661 (2021).

Book, C. et al. Stabilizing effect of bedrock uplift on retreat of Thwaites Glacier, Antarctica, at centennial timescales. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 597, 117798 (2022).

Coulon, V. et al. Disentangling the drivers of future Antarctic ice loss with a historically calibrated ice-sheet model. Cryosphere 18, 653–681 (2024).

Mercer, J. H. West Antarctic Ice Sheet and CO2 greenhouse effect: A threat of disaster. Nature 271, 321–325 (1978).

Joughin, I. & Alley, R. B. Stability of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet in a warming world. Nat. Geosci. 4, 506–513 (2011).

Schoof, C. Ice sheet grounding line dynamics: Steady states, stability, and hysteresis. J. Geophys. Res. 112, F03S28 (2007).

Barletta, V. R. et al. Observed rapid bedrock uplift in Amundsen Sea Embayment promotes ice-sheet stability. Science 360, 1335–1339 (2018).

Lloyd, A. J. et al. Seismic structure of the antarctic upper mantle imaged with adjoint tomography. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 124, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JB017823 (2019).

Nield, G. A. et al. Rapid bedrock uplift in the Antarctic Peninsula explained by viscoelastic response to recent ice unloading. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 397, 32–41 (2014).

Wu, P. & Peltier, W. R. Viscous gravitational relaxation. Geophys. J. Int. 70, 435–485 (1982).

Mitrovica, J. X. & Peltier, W. R. A complete formalism for the inversion of post glacial rebound data: resolving power analysis. Geophys. J. Int. 104, 267–288 (1991).

Hay, C. C. et al. Sea level fingerprints in a region of complex Earth structure: The case of WAIS. J. Clim. 30, 1881–1892 (2017).

Pan, L. et al. Rapid postglacial rebound amplifies global sea-level rise following West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse. Sci. Adv. 7, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abf7787 (2021).

Yousefi, M. et al. The influence of the solid Earth on the contribution of marine sections of the Antarctic Ice Sheet to future sea-level change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097525 (2022).

Hirth, G. & Kohlstedf, D. Rheology of the upper mantle and the mantle wedge: A view from the experimentalists. Geophys. Monogr. Ser. 138, 83–106 (2003).

Blank, B. et al. Effect of lateral and stress-dependent viscosity variations on GIA induced uplift rates in the Amundsen Sea Embayment. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 22, e2021GC009807 (2021).

Bradley, S. L. et al. Low post-glacial rebound rates in the Weddell Sea due to Late Holocene ice-sheet readvance. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 413, 79–89 (2015).

Wolstencroft, M. et al. Uplift rates from a new high-density GPS network in Palmer Land indicate significant late Holocene ice loss in the southwestern Weddell Sea. Geophys. J. Int. 203, 737–754 (2015).

Depoorter, M. et al. Calving fluxes and basal melt rates of Antarctic ice shelves. Nature 502, 89–92 (2013).

Rignot et al. Ice-Shelf Melting Around Antarctica. Science 341, 266–270 (2013).

Dupont, T. K. & Alley, R. B. Assessment of the importance of ice-shelf buttressing to ice-sheet flow, Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L04503 (2005).

Haseloff, M. & Sergienko, O. V. The effect of buttressing on grounding line dynamics. J. Glaciol. 64, 417–431 (2018).

Haseloff, M. & Sergienko, O. V. Effects of calving and submarine melting on steady states and stability of buttressed marine ice sheets. J. Glaciol. 68, 1149–1166 (2022).

Morlighem, M. et al. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet may not be vulnerable to marine ice cliff instability during the 21st century. Sci. Adv. 10, eado7794 (2024).

Rignot, E. et al. Four decades of Antarctic Ice Sheet mass balance from 1979–2017. PNAS 116, 1095–1103 (2019).

van den Akker, T. et al. Present-day mass loss rates are a precursor for West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse. Cryosphere 19, 283–301 (2025).

van Calcar, C. J., Whitehouse, P. L., van de Wal, R. S. W. & van der Wal, W. Approximating ice sheet – bedrock interaction in Antarctic ice sheet projections, EGUsphere. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-2982 (2024).

Van Calcar, C. J. et al. Simulation of a fully coupled 3D glacial isostatic adjustment – ice sheet model for the Antarctic ice sheet over a glacial cycle. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 5473–5492 (2023).

Berends, C. J. et al. Benchmarking the vertically integrated ice-sheet model IMAU-ICE (version 2.0). Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 5667–5688 (2022).

Morland, L. W. Unconfined ice-shelf flow. Dyn. West Antarct. Ice Sheet 4, 99–116 (1987).

Bueler, E. & Brown, J. Shallow shelf approximation as a “sliding law” in a thermomechanically coupled ice sheet model. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 114, F03008 (2009).

Morlighem, M. et al. Deep glacial troughs and stabilising ridges unveiled beneath the margins of the Antarctic ice sheet. Nat. Geosci. 13, 132–137 (2020).

Zoet, L. K. & Iverson, N. R. A slip law for glaciers on deformable beds. Science 368, 76–78 (2020).

Shapiro, N. M. & Ritzwoller, M. H. Inferring surface heat flux distributions guided by a global seismic model: particular application to Antarctica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 223, 213–224 (2004).

Favier, L. et al. Assessment of sub-shelf melting parameterisations using the ocean–ice-sheet coupled model NEMO(v3.6)–Elmer/Ice(v8.3). Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 2255–2283 (2019).

Goelzer, H. et al. Brief communication: On calculating the sea-level contribution in marine ice-sheet models. Cryosphere 14, 833–840 (2020).

Le Meur, E. & Huybrechts, P. A comparison of different ways of dealing with isostasy: examples from modelling the Antarctic ice sheet during the last glacial cycle. Ann. Glaciol. 23, 309–317 (1996).

Zweng, M. M. et al. World Ocean Atlas 2018, Volume 2: Salinity. https://data.nodc.noaa.gov/woa/WOA18/DOC/woa18-vol2.pdf (2019).

Jourdain, N. C. et al. A protocol for calculating basal melt rates in the ISMIP6 Antarctic ice sheet projections. Cryosphere 14, 3111–3134 (2020).

Meehl, G. A. et al. Context for interpreting equilibrium climate sensitivity and transient climate response from the CMIP6 Earth system models. Sci. Adv. 6, 1981 (2020).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Klemann, V., Wu, P. & Wolf, D. Compressible viscoelasticity: stability of solutions for homogeneous plane-Earth models. Geophys. J. Int. 153, 569–585 (2003).

A., G., Wahr, J. & Zhong, S. Computations of the viscoelastic response of a 3-D compressible Earth to surface loading: an application to Glacial Isostatic Adjustment in Antarctica and Canada, Geophys. J. Int. 192, 557–572 (2013).

Reusen, J. M., Steffen, R., Steffen, H., Root, B. C.& van der Wal, R. Simulating horizontal crustal motions of glacial isostatic adjustment using compressible Cartesian models. Geophys. J. Int. 235, 542–553 (2023)

Mitrovica, J. X. et al. The sea-level fingerprint of west Antarctic collapse. Science 323, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1166510 (2009).

Becker, T. W. & Boschi, L. A comparison of tomographic and geodynamic mantle models. Geochem. Geophy. Geosy. 3, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GC000168 (2002).

Karato, S. I., Jung, H., Katayama, I. & Skemer, P. Geodynamic significance of seismic anisotropy of the upper mantle: new insights from laboratory studies. Annu. Rev. Earth. Pl. Sc. 36, 59–95 (2008).

Ivins, E. R. et al. Antarctic upper mantle rheology. https://doi.org/10.1144/M56-2020-19 (2023).

Van der Wal, W., Wu, P., Wang, H. & Sideris, M. G. Sea levels and uplift rate from composite rheology in glacial isostatic adjustment modeling. J. Geodyn. 50, 38–48 (2010).

Van der Wal, W., Whitehouse, P. L. & Schrama, E. J. O. Effect of GIA models with 3D composite mantle viscosity on GRACE mass balance estimates for Antarctica. Earth. Planet. Sc. Let. 414, 134–143 (2015).

Martin, A. P. A review of the composition and chemistry of peridotite mantle xenoliths in volcanic rocks from Antarctica and their relevance to petrological and geophysical models for the lithospheric mantle. Geol. Soc. Mem. 56, 343–354 (2021).

van Calcar, C. J. Data underlying the publication: Bedrock uplift reduces Antarctic sea-level contribution over next centuries. Version 1. 4TU.ResearchData, dataset, https://doi.org/10.4121/e7523ed4-c4ec-42a2-9522-66ae81313e38.v1 (2025).

van Calcar, C. J. Model underlying the publication: Bedrock uplift reduces Antarctic sea-level contribution over next centuries. Version 1. 4TU.ResearchData, dataset, https://doi.org/10.4121/e7523ed4-c4ec-42a2-9522-66ae81313e38 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ann Kristin Klose and Violaine Coulon for preparing and providing the forcing data of the climate models. Work for this publication was performed in the framework of PROTECT, which received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 869304. This is PROTECT publication number 154. The study was also supported by the project 3D Earth, funded by ESA as a Support to Science Element (STSE). C.B. and J.B. received funding from NWO, grant OCENW.KLEIN.515.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The conceptualisation was done by C.v.C., W.v.d.W. and R.v.d.W. Model development was done by C.v.C., C.B. and J.B. C.v.C. conducted the model experiments and performed the data analysis with input from WvdW and RvdW. C.v.C., J.B., C.B., W.v.d.W. and R.v.d.W. contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Matt King and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Calcar, C.J., Bernales, J., Berends, C.J. et al. Bedrock uplift reduces Antarctic sea-level contribution over next centuries. Nat Commun 16, 10512 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66435-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66435-y