Abstract

Adult stem cells (SCs) transition between quiescent and active states to maintain tissue integrity, and dysregulation of this balance can lead to tissue degeneration, cancer, or premature aging. Both intrinsic factors and extrinsic niche signals influence these states; however, the molecular mechanisms that integrate extrinsic cues with intrinsic programs remain poorly understood. Here, we show that the conserved repressive histone mark, H2AK119ub, serves as a molecular switch linking inhibitory fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signals with the quiescent transcriptional program in hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs). Modulation of FGF signaling is associated with changes in H2AK119ub levels, thereby toggling HFSCs between quiescence and activation states. Mechanistically, H2AK119ub directly represses a proliferation-promoting transcriptional program preserving HFSC quiescence. Loss of H2AK119ub in HFSCs shortens the quiescent phase and induces repeated rounds of HFSC activation, ultimately leading to SC exhaustion – a hallmark of aging tissue. Analysis of other mammalian SC systems and Drosophila germline SCs confirms that H2AK119ub is a broadly conserved hallmark of quiescence and is dynamic upon SC activation. These findings reveal a signaling-epigenetic axis that controls SC quiescence and underscores the importance of the conserved role of H2AK119ub in maintaining tissue homeostasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adult resident stem cells (SCs) are defined by their long-lived nature, capacity to give rise to differentiating daughter cells, and their ability to retain their identity by undergoing self-renewal1,2. While in some tissues, SCs engage in repetitive regeneration events to allow for rapid tissue turnover, in other tissues, they remain in a prolonged state of quiescence3,4,5. Dysregulation of the balance between SC quiescence and activation leads to unfavorable outcomes, including SC depletion, tissue degeneration, accumulation of oncogenic mutations, and premature aging6,7. Recent insights have revealed that rather than being a default phenomenon, SCs actively adopt the quiescent state to downregulate fundamental intrinsic processes—such as the cell cycle, cellular metabolism, and transcriptional output—to withstand stress and prevent genomic instability8,9,10,11. There are several regulatory cues that dictate SC quiescence or activation states. Extrinsic signals from the SC niche play an important role in dictating the transition between quiescent and active states that are then facilitated by cell-intrinsic mechanisms12,13,14. How intrinsic mechanisms integrate and respond to extrinsic environmental changes to regulate SC states remains a largely unanswered question.

The adult hair follicle (HF) is a powerful model for probing the regulatory mechanisms that modulate SC quiescence and activation. The HF undergoes cyclical bouts of regeneration, called the hair cycle, that can be divided into three successive phases of tissue remodeling: telogen (rest), anagen (growth), and catagen (regression)15,16,17. The long-lived hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) that reside in a structurally defined “bulge” region of the HF are primarily quiescent but enter a brief period of activation during anagen onset to self-renew and generate progenitor cells that fuel hair regeneration18,19,20. The HFSC activation period is transient, and these cells quickly return to quiescence while the progenitor cells continue HF production. The quiescent and activation states of HFSCs are tightly governed by cell-intrinsic factors as well as extrinsic signals from the surrounding niche21,22,23,24. The temporal dynamics of HF regeneration offer a unique opportunity to dissect the mechanisms that establish and modulate the transcriptional programs governing HFSC quiescence and activation in response to niche signaling changes.

Histone modifications are plausible candidates for regulating HFSC states as they provide a higher-order control over gene expression25,26. Histone modifications, such as histone methylation, acetylation, or ubiquitination, modulate the overall structure of chromatin, determining the access of transcription factors and other regulatory proteins to their target genes27,28. Thus, histone modifications can simultaneously regulate large networks of genes, giving them the potential to globally control SC states. Unlike transcription factors, which often act transiently29,30, histone modifications that alter chromatin state can provide longer-term control of gene expression state but can also be rapidly remodeled to enable the regulation of gene expression in response to changes in extrinsic cues31,32,33, therefore making them critical effectors in the control of HFSC states, function, and identity over time.

Among the many histone modifications, histone H2A on lysine 119 ubiquitination (H2AK119ub) is a conserved mark that plays a central role in gene repression34,35,36. This modification is deposited by Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1), which exists in canonical and non-canonical forms, each defined by specific accessory subunits that influence its recruitment and function37,38. The catalytic core of PRC1 consists of the RING1A/B proteins, which act as E3 ubiquitin ligases to catalyze H2AK119ub39. Through this activity, PRC1 creates a repressive chromatin state by limiting transcriptional elongation, engaging additional silencing factors, and compacting chromatin structure40,41,42,43. Collectively, these activities allow PRC1 to establish gene repression programs that are stable yet remain flexible to respond to developmental and environmental signals. However, whether gene repressive functions mediated by PRC1/H2AK119ub govern SC state transitions in response to changing environmental cues remains largely unknown.

Here, we show that H2AK119ub acts as a key molecular switch that coordinates inhibitory signaling cues with intrinsic SC transcriptional programs to maintain HFSC quiescence and longevity. Additionally, we have observed that H2AK119ub exhibits similar dynamic changes between quiescent and activated SC states across various adult SC systems, highlighting its crucial role in maintaining quiescence, preventing premature exhaustion, and preserving the SC pool.

Results

Histone mark H2AK119ub is dynamic during HFSC quiescence and activation

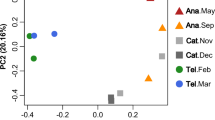

To identify whether key histone modifications that influence gene expression are dynamic in HFSCs, we used immunofluorescence (IF) analysis coupled with the incorporation of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) to mark the quiescent and the earliest activated stages of the HF bulge of the mouse dorsal skin. We found no prominent differences in the levels of tri-methylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3)44, a mark associated with active chromatin, between EdU(-) quiescent (Postnatal day (P) 21 and P55) and EdU(+) active (P23 and P26) HF bulges (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We next examined the distribution of Polycomb-mediated histone modifications, which are known to be associated with gene repression37,45,46. Like H3K4me3, Polycomb repressive complex (PRC) 2-dependent tri-methylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) remained steady between quiescent and active bulges (Supplementary Fig. 1b), but strikingly, PRC1-dependent H2AK119ub was diminished in active HF bulges in comparison to quiescent ones (Fig. 1a, b). Co-staining of H2AK119ub with an HFSC stem cell marker, CD3447, confirmed that the level of H2AK119ub was downregulated in activated HFSCs of early-anagen skin (P23, P26) (Supplementary Fig. 2a). We also conducted nuclear flow cytometry analysis of all three histone modifications in HFSCs identified as Sca-1− α6-integrinhigh CD34+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 2b) and confirmed that the distribution of H2AK119ub(+) HFSCs significantly changed during the transition from quiescence to activation (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3a–c). Collectively, these results identified that the repressive histone modification, H2AK119ub, is dynamic between HFSC quiescent and active states.

a Whole-mount IF analysis of H2AK119ub (green), EdU (red), and DAPI (blue) in telogen I (P21), early anagen (P23, P26), and telogen II (P55). EdU and H2AK119ub channels shown in grayscale. Yellow dashed line outlines the bulge region. b Violin plot shows H2AK119ub intensity in HFSCs from P21, P23, P26, and P55 mice (n = 3 biological replicates from independent litters/time point; a total of 220 (P21), 219 (P23), 214 (P26), and 210 (P55) HFSCs were quantified). The central line = median; upper/lower lines = 75th/25th percentiles. One-way ANOVA (Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, α = 0.05) on mean intensities from three biological replicates across all time points: F(3,8) = 13.9; P = 0.0018 (P21 vs. P23), 0.0001 (P21 vs. P26), and 0.0754 (P21 vs. P55). c Percentage of H2AK119ub(+) HFSCs in P21, P23, P26, and P55 skin measured by flow cytometry (n = 3 biological replicates from independent litters/time point). Bars, mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA (Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, α = 0.05): F(3,8) = 14.67; P = 0.0103 (P21 vs. P23), 0.0050 (P21 vs. P26), and 0.7395 (P21 vs. P55). Scale bar: 25 μm. (See also Supplementary Figs. 1–3).

H2AK119ub preserves HFSC quiescence in the adult skin

PRC1-mediated H2AK119ub has emerged as a key modification for maintaining stable Polycomb repressive domains and silencing target genes35,48. As we observed a significant decrease in H2AK119ub levels in HFSCs during early anagen (Fig. 1), we aimed to investigate the role of H2AK119ub in regulating HFSC states. We crossed K15-CrePR49 mice with Ring1a-null, Ring1bflox/flox mice to generate conditional-inducible PRC1-null mice (K15-CrePR: Ring1a−/−, Ring1bflox/flox = PRC1 i2KO), in which the catalytic core of PRC1, comprising the E3 ubiquitin ligases, RING1A/B, is ablated in the HF bulge (Supplementary Fig. 4a). We confirmed that the topical application of RU-486 to the shaved back skin of PRC1 i2KO mice during telogen II (Supplementary Fig. 4b) efficiently ablates H2AK119ub in the HF bulge, including the HFSCs (Supplementary Fig. 4c). We also confirmed that levels of H3K27me3 remain unchanged upon the loss of PRC1 function (Supplementary Fig. 4d), thereby establishing that loss of H2AK119ub does not globally affect the levels of PRC2-dependent H3K27me3 histone mark.

PRC1/H2AK119ub is a potent regulator of SC fate and represses pro-apoptotic genes to conserve SC function in different developing and homeostatic tissues50. However, IF analysis of control and PRC1 i2KO skin post-induction revealed that loss of PRC1/H2AK119ub does not alter HFSC fate, as expression of a key HFSC fate marker, SOX951, was comparable between control and PRC1-null HFSCs (Supplementary Fig. 4e). It also did not lead to the expression of either the pro-apoptotic marker P19 (ARF) (Supplementary Fig. 4f) or the programmed cell death marker activated Caspase 3 (Ac-CASP3) (Supplementary Fig. 4g).

While we did not observe any changes in HFSC identity upon H2AK119ub ablation, morphological analysis of control and PRC1 i2KO skin samples revealed striking differences. H&E analysis of PRC1 i2KO and control littermate skins revealed that while control HFs remained in telogen, the PRC1 i2KO HFs underwent premature anagen entry (Supplementary Fig. 5a), and PRC1 i2KO mice recovered their hair coat more rapidly than control littermates (Fig. 2a, b). As PRC1 i2KO mice exhibited precocious hair regeneration, we tested whether the loss of PRC1/H2AK119ub leads to premature activation of the HF bulge. Analysis of proliferation by EdU incorporation showed that by P73, ~53% of the HFs in PRC1 i2KO were EdU(+) and increased to ~72% by P75 (Fig. 2c, d). We also implemented a previously described fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS) strategy52 to isolate HFSCs (EpCAM+ Sca-1− α6-integrinhigh CD34+) from P70 control and PRC1 i2KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 5b) just prior to the onset of bulge proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 5c) and cultured them on fibroblast feeders. Notably, PRC1 i2KO HFSCs formed a significantly greater number of colonies, which also grew larger than control HFSC colonies (Fig. 2e), indicating that the loss of PRC1 in quiescent HFSCs intrinsically enhances their proliferative potential.

a (Left) Images of control and PRC1 i2KO mice at induction (P50), 25 days (P85), and 45 days (P105) after induction. a (Right) H&E analysis of P105 back skin sections. b Quantification of hair coat recovery (n = 5 biological replicates from independent litters/condition). Two-tailed Mann–Whitney t-test: U = 0, P = 0.0079). c Whole-mount IF of H2AK119ub (red), EdU (green), and DAPI (blue) in the HF bulge of P73 and P75 control and PRC1 i2KO mice. EdU shown in grayscale. Yellow dashed line outlines the bulge region. d Percentage of EdU(+) HFs in P73 and P75 control and PRC1 i2KO mice (n = 4 independent biological replicates/time point; 168 control and 168 PRC1 i2KO HFs were quantified/group). Welch’s two-tailed t-test: P73: t(6) = 3.83, P = 0.0086; P75: t(5) = 10.79, P = 0.0001. e HFSC colonies from P70 control and PRC1 i2KO mice were cultured for 12 days. Left, colony number (n = 3 biologically independent replicates/condition, each with 3 technical replicates). Welch’s two-tailed t-test: t(3.2) = 13.80, P = 0.0006. Right, colony size (n = 3 biologically independent replicates, each with 3 technical replicates). Welch’s unpaired two-tailed t-test: t(3.4) = 6.006, P = 0.0037. f HFSC colonies from P70 control and PRC1-I53A mice were cultured for 12 days. Left, colony number (n = 3 biologically independent replicates/condition, each with 3 technical replicates). Welch’s two-tailed t-test: t(3.1) = 3.86, P = 0.0288. Right, colony size (n = 3 biologically independent replicates/condition, each with 3 technical replicates. Welch’s two-tailed t-test: t(3.4) = 5.62, P = 0.0079). g HFSC colonies from P70 control and Bap1 iKO mice were cultured for 16 days. Left, colony number (n = 3 biologically independent replicates/condition, each with 3 technical replicates). Welch’s two-tailed t-test: t(3.8) = 7.9, P = 0.0017. Right, colony size (n = 3 biologically independent replicates/condition, each with 3 technical replicates). Welch’s two-tailed t-test: t(3.8) = 12.56, P = 0.0003. Error bars, mean ± SEM. Scale bar for IF = 25 μm; H&E = 50 μm. (See also Supplementary Figs. 4–6).

To determine if the phenotype observed in PRC1 i2KO mice was predominantly dependent on the loss of PRC1’s catalytic activity of depositing mono-ubiquitination34, we generated conditional-inducible PRC1 catalytic-inactive mice (K15-CrePR: Ring1a−/−,Ring1bI53A/flox = PRC1-I53A), in which the Ring1b gene carries an I53A point mutation that abolishes its E3-ligase activity, and thus the establishment of H2AK119ub, while maintaining all other PRC1 functions53 (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). Matching our observations with PRC1 i2KO mice, PRC1-I53A mice recovered their hair coat faster than control littermates (Supplementary Fig. 6c). In vitro, PRC1-I53A HFSCs not only formed significantly more colonies but also larger colonies compared to controls, thereby phenocopying PRC1 i2KO HFSCs (Fig. 2f).

Finally, we asked if inhibiting the dynamic regulation of H2AK119ub would impact HF regeneration and HFSC proliferative status. BAP1 is a ubiquitin hydrolase that works antagonistically to PRC1 to remove mono-ubiquitination from histone H2A lysine 11954. We generated conditional-inducible Bap1-null mice (K15-CrePR: Bap1flox/flox = Bap1 iKO) and confirmed the downregulation of Bap1 RNA in HFSCs by conducting RT-qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 6d, e). Remarkably, loss of Bap1 in HFSCs not only resulted in a delayed anagen entry compared to control littermates (Supplementary Fig. 6f) but also significantly compromised the proliferative potential of Bap1-null HFSCs, as evidenced by their formation of fewer and smaller colonies in vitro (Fig. 2g), opposite to the enhanced colony-forming capacity observed in PRC1 i2KO and PRC1-I53A HFSCs. Overall, these genetic studies highlight that H2AK119ub is an instructive regulator of HFSC quiescence, and the temporal modulation of this histone modification in HFSCs is essential for the timely transition from HFSC quiescence to activation to fuel HF regeneration.

Modulation of FGF signaling in the skin microenvironment alters H2AK119ub levels in HFSCs

HFSC quiescence and activation are extrinsically regulated by several niche signaling pathways, which are themselves dynamically modulated during the hair cycle23,55,56. In particular, inhibitory fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 18 signaling from the Keratin (Krt) 6+ niche cells, located adjacent to the HFSCs, plays an essential role in preserving HFSC quiescence and is downregulated prior to HFSC activation23,55,56. Notably, the conditional knockout of FGF18 in the epidermis, including in the Krt6+ cells, leads to rapid successive hair cycling57. Furthermore, mechanical removal of the FGF18-producing Krt6+ inner bulge cells via waxing (depilation) results in precocious HFSC activation and premature bulge proliferation56. Given that epigenetic mechanisms can respond to changes in the availability of signaling pathways to mediate gene regulation31,32,33, we speculated whether inhibitory FGF signaling within the HF microenvironment could influence H2AK119ub levels, thereby maintaining HFSC quiescence and restricting untimely HF bulge proliferation.

To test this, we first implemented pharmacological inhibition of endogenous FGF signaling by conducting intradermal injections of a selective fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) 1-3 inhibitor, AZD4547, or vehicle control (PBS+DMSO) in wild-type mice over a 5-day period during mid-telogen (P60) (Supplementary Fig. 7a) when the HFSC quiescence-maintaining FGF18 ligands are high and HFSC activating ligands, FGF7/10, are low55 and assessed for H2AK119ub levels and HF bulge activation. Remarkably, just 1 day after the completion of the injection regimen, HFSCs of the AZD4547-injected site exhibited drastic downregulation of H2AK119ub levels compared to HFSCs in the vehicle samples (Fig. 3a, left). 3 days post-injection regimen, we observed EdU(+) proliferative bulges in the AZD4547-injected site, while bulges in the vehicle-injected site remained quiescent (Fig. 3a, right). These observations highlighted that pharmacologic inhibition of FGF receptors in the skin is accompanied by reduced H2AK119ub levels, prior to proliferation, suggesting a link between FGF signaling and chromatin regulation in the HF niche. By day 7 post-injection, the AZD4547-injected site had visible darkening of the dermis, indicating an active anagen phase (Fig. 3b, top). This became even more prominent by day 10 post-injection regimen (Fig. 3b, bottom). Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining verified that while the HFs in the vehicle-injected site remained in telogen, the HFs at the AZD4547-injected site were in the anagen phase of the hair cycle (Fig. 3b, right). Subsequently, by day 14, we observed hair coat recovery at the inhibitor-injected site but not at the vehicle-injected site (Supplementary Fig. 7b). To rule out the possibility that inhibition of FGF signaling via AZD4547 affected other histone modifications and to confirm that the observed effects were specific to H2AK119ub, we assessed H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 levels in bulges of vehicle and AZD4547-injected site and confirmed that they remained unaffected by AZD4547 (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d).

a Whole-mount IF of H2AK119ub (red), CD34 (green), EdU (gray), and DAPI (blue) in vehicle- and AZD4547-injected site 1 day and 3 days post-injection (d.p.i). H2AK119ub and EdU channels shown in grayscale; CD34(+) HFSCs outlined with yellow dashed line. Violin plot shows H2AK119ub intensity in HFSCs from vehicle- and AZD4547-injected samples (n = 3 biologically independent replicates from separate litters/condition; a total of 221, 211, 222, and 216 HFSCs quantified/group). Welch’s two-tailed t-test was conducted on mean intensities for each time point. (For 1 d.p.i; t(2.8) = 19.45, P = 0.0001, for 3 d.p.i; t(2.9) = 25.7, P = 0.0001). b (Left) Representative images of the dermal side of skin 7 days (top) and 10 days (bottom) after AZD4547 injection from one of three independent biological replicates (individual mice from separate experiments) that yielded comparable results. b (Right) H&E analysis of skin sections from vehicle- and AZD4547-injected sites 7 days and 10 days post-injection. c Whole-mount IF of H2AK119ub (red), CD34 (green), EdU (gray), and DAPI (blue) in unwaxed control, vehicle-injected, and 2 days post-waxing (2 d.p.w), and FGF18-injected and 2 p.d.w skins. H2AK119ub and EdU channels shown in grayscale; CD34(+) HFSCs are outlined in yellow dashed line. Violin plot shows H2AK119ub intensity in HFSCs from each condition (n = 3 biologically independent animals from separate litters/condition; a total of 218, 221, and 215 HFSCs quantified/condition). Welch’s two-tailed t-test was conducted on mean intensities: unwaxed vs 2 d.p.w-vehicle, t(2.9) = 12.9, P = 0.0001; 2 d.p.w-vehicle vs 2 d.p.w-FGF18, t(2.9) = 10.8, P = 0.0001). All violin plots show the distribution of values; the central line = median; upper/lower lines = 75th/25th percentiles. Scale bars: IF = 25 μm; H&E = 100 μm. (See also Supplementary Fig. 7).

Since H2AK119ub was uniquely reduced upon FGFR inhibition, we next asked whether disruption of the PRC1 complex underlies this phenomenon. To address this, we assayed the levels of core PRC1 subunits, the catalytic RING1B ubiquitin ligase that deposits H2AK119ub39, and the stabilizing subunit BMI1, which enhances RING1 activity and promotes chromatin association to sustain this histone modification58,59,60. We performed immunostaining for BMI1 and RING1B in control and AZD4547-injected skin 1 day post-injection, when reduced H2AK119ub is observed before proliferation onset (Fig. 3a, left). This analysis revealed that RING1B levels were modestly decreased (Supplementary Fig. 7e), and BMI1 levels were significantly reduced (Supplementary Fig. 7f), suggesting that the loss of H2AK119ub is coupled with the destabilization of the PRC1 complex following FGFR inhibition. These findings support a potential link between FGF signaling and PRC1 composition, which may contribute to the regulation of HFSC quiescence and activation states.

To further test whether quiescence-maintaining FGF signaling is sufficient to regulate H2AK119ub in HFSCs, we first determined whether the removal of FGF18-producing Krt6+ cells via depilation impacts H2AK119ub levels. Therefore, we depilated the telogen HFs of P65 wild-type mice and assayed for EdU incorporation and H2AK119ub levels 2 days post-waxing (P67). We found that compared to the quiescent bulges of unwaxed control skin, which maintained H2AK119ub levels with no EdU incorporation, depilation led to drastic downregulation of H2AK119ub levels and bulge proliferation, as evidenced by a prominent increase in EdU(+) cells (Supplementary Fig. 7g). Finally, we tested whether the exogenous delivery of FGF18 to waxed skin could preserve H2AK119ub levels and prevent HFSC activation. We intradermally injected P60 wild-type mice with either vehicle (PBS) or recombinant FGF18 protein on opposite sides of the back skin for six consecutive days. On day 7 (P66), we waxed the back skin and collected samples 2 days post-waxing (P68) (Supplementary Fig. 7h). As expected, the bulges in vehicle-injected waxed skin were proliferative and exhibited a drastic downregulation of H2AK119ub compared to unwaxed control skin (Fig. 3c, top). Curiously, the bulges in FGF18-injected waxed skin remained non-proliferative and displayed significantly higher levels of H2AK119ub compared to vehicle-treated sites, consistent with a possible stabilizing influence of FGF18 on chromatin state of HFSCs (Fig. 3c, bottom).

Together, these studies suggest that FGF signaling in the HF microenvironment correlates with the changes in H2AK119ub levels associated with HFSC quiescence. Pharmacologic or exogenous modulation of the FGF pathway alters H2AK119ub dynamics, supporting a potential link between FGF activity and the chromatin-based regulation of HFSC states.

H2AK119ub directly represses the proliferation program in quiescent HFSCs

To identify the quiescence-maintaining intrinsic processes regulated by PRC1/H2AK119ub, we purified HFSCs from the back skin of P70 control and PRC1 i2KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 5b) prior to the onset of proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 5c) and conducted RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq). Differential gene expression analysis revealed significant downregulation of 176 genes and upregulation of 774 genes in PRC1-null HFSCs (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Data 1). The higher number of upregulated genes is consistent with H2AK119ub’s primarily repressive role in gene regulation, and we thus focused on these genes. Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed that genes upregulated in P70 PRC1-null HFSCs were associated with proliferation-promoting processes such as cell cycle and cell division (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Conversely, expression of known HFSC quiescence maintenance factors, including Nfatc161, Foxc162,63 and Bmp656 remained unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of a previously described anagen-enriched gene data set64 revealed that PRC1-null HFSCs are similar to activated HFSCs, with upregulation of 166 anagen-enriched genes (Fig. 4b). GO analysis of these genes revealed an overwhelming association with cell cycle, cell division, mitosis, and proliferation processes (Fig. 4c, left). Among these genes were epidermal SC activation regulators such as Wnt5a65, Ptch266, and MycN67, and cell cycle and cell division genes such as Ccna268, Ccnb269, Cdc770, Cdk171, Mki6772, Kif2373, and Top2a74 (Fig. 4c, right). Because the writing and erasure of histone modification is a labile process75 and robust changes in gene expression that are dependent on the removal of histone modifications may require additional time, we also conducted RNA-seq with HFSCs isolated from the back skin of P75 control and PRC1 i2KO mice. Differential gene expression analysis revealed even larger changes in PRC1-null HFSCs with 1546 upregulated genes (Supplementary Fig. 8c and Supplementary Data 2). Consistent with P70 upregulated genes, GO analysis revealed that the top biological processes associated with P75 upregulated genes were associated with cell cycle and cell division (Supplementary Fig. 8d). A comparison with the anagen-enriched data set revealed that 310 genes upregulated in P75 PRC1 i2KO HFSCs were also anagen-enriched (Supplementary Fig. 8e). Together, these transcriptional studies revealed that loss of H2AK119ub in HFSCs leads to a progressive establishment of a transcriptional landscape akin to that in activated HFSCs.

a Volcano plot of differentially expressed (DE) genes in FACS-purified HFSCs from P70 control and PRC1 i2KO mice. Genes with absolute fold change ≥1.5 and adjusted P < 0.05 were considered significantly up- or downregulated for further analysis. RNA-seq was performed on ≥2 biological replicates per group from two independent litters. Differential expression was assessed using DESeq2 (Wald test, two-sided) with Benjamini–Hochberg false-discovery-rate (FDR) correction for multiple gene-wise comparisons. b Gene-set enrichment analysis shows significant overlap between genes upregulated in PRC1 i2KO HFSCs and anagen-enriched genes (NES = 2.04, P < 1E−10). Venn diagram indicates 166 anagen-enriched genes are upregulated in PRC1 i2KO HFSCs. c Gene ontology (GO) terms associated with the 166 anagen-enriched genes upregulated in PRC1 i2KO HFSCs, with selected differentially expressed genes listed by fold change. d Stacked graph shows that 62% of anagen-enriched genes upregulated in P70 PRC1 i2KO HFSCs are H2AK119ub targets. Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) yielded P < 0.05. e Heatmap of H2AK119ub occupancy at promoters of the 166 anagen-enriched genes upregulated in P70 PRC1 i2KO HFSCs. CUT&RUN signal shown for P55 quiescent wild-type (top) and P68 PRC1 i2KO (bottom) HFSCs, with two biological replicates each. Color scale represents log2-normalized read density (red = higher occupancy, blue = lower occupancy) within ±10 kb of transcription start sites (TSS), normalized to sequencing depth. f IGV tracks show H2AK119ub occupancy at the proliferation-promoting and cell cycle genes in wild-type quiescent HFSCs and PRC1 i2KO HFSCs. Promoter regions highlighted with red dashed boxes. (See also Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9).

Next, we asked if H2AK119ub directly represses these anagen-enriched genes in quiescent HFSCs. To address this, we conducted Cleavage Under Targets & Release Using Nuclease (CUT&RUN) with antibodies against H2AK119ub in quiescent HFSCs isolated from the back skin of telogen II (P55) C57BL/6 wild-type mice. This analysis defined the genomic distribution of H2AK119ub in quiescent HFSCs and allowed us to directly compare its occupancy with transcriptional changes observed in PRC1-null HFSCs. Given H2AK119ub’s primary role in transcriptional repression, we focused on integrating our CUT&RUN data with upregulated genes in PRC1 i2KO HFSCs. This analysis revealed that 68.7% of the genes upregulated at P70 and 52.5% of the genes upregulated at P75 were demarcated by H2AK119ub in quiescent HFSCs (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b and Supplementary Data 3 and 4). Furthermore, analysis of the 166 anagen-enriched genes upregulated in P70 PRC1 i2KO HFSCs (Fig. 4b) showed that 62% of these genes showed an enrichment of H2AK119ub occupancy (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Data 5). To validate these findings, we also performed CUT&RUN with H2AK119ub in PRC1-null HFSCs isolated from P68 PRC1 i2KO mice prior to the onset of proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 5c). As predicted, we observed a global reduction, but not complete erasure, of this mark (Supplementary Fig. 9c), consistent with a knock-out efficiency of 80-90%. Importantly, when we compared H2AK119ub occupancy at the promoters of the 166 anagen-enriched genes between wild-type quiescent and PRC1 i2KO HFSCs, we found that H2AK119ub demarcation at these genes were markedly diminished (Fig. 4e). Genome browser (IGV) tracks at representative proliferation-associated and cell cycle genes, including Wnt5a, MycN, Ccna2, Cdk1, Ptch2, Cdc7 and Kif23 further illustrate robust H2AK119ub occupancy in wild-type quiescent HFSCs but reduced in PRC1-null HFSCs (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 9d). Collectively, these analyses demonstrate that, during quiescence, H2AK119ub functions as a barrier to HFSC activation by directly repressing a transcriptional landscape that promotes proliferation.

Dysregulation of H2AK119ub-dependent quiescence leads to repeated hair cycling and HFSC exhaustion

We next determined if loss of H2AK119ub-mediated repression of the quiescence-maintaining transcriptional landscape has long-term consequences on HFSC regulation. Our initial observations with control and PRC1 i2KO mice, post-induction, revealed premature anagen entry and rapid hair coat recovery in PRC1 i2KO mice (Fig. 2a, b). Further mapping of the hair cycle revealed that PRC1 i2KO mice not only successfully regrew their hair coat by P100, but also transitioned into the subsequent telogen phase, characterized by its pink hue, confirming the unperturbed completion of the hair cycle (Fig. 5a). Curiously, instead of remaining in telogen for an extended period, as observed in the control littermates, PRC1 i2KO mice initiated the next anagen phase and recovered their second hair coat by P130 (Fig. 5a). Therefore, to assess if the long-term timing of hair regeneration is altered in PRC1 i2KO mice, we tracked the hair cycle in control and PRC1 i2KO mice over a period of 8 months post-induction (Supplementary Fig. 10a). We observed that while control animals generally underwent two hair cycles during this time, PRC1 i2KO mice initiated anagen entry more than 4 times (Supplementary Fig. 10b, Fig. 5b). Together these data indicate that ablation of H2AK119ub in HFSCs and establishment of a proliferation-promoting transcriptional program shortens the quiescent phase of the hair cycle resulting in repeated hair cycling.

a Images of back skin from control and PRC1 i2KO mice at induction (P50), 40 days (P100), and 70 (P130) days after induction. b Quantification of hair cycle frequency over 8 months (M) (n = 5 biologically independent animals from separate litters/genotype). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant effects of genotype (F(1,8) = 373.8, P = 0.0001), time (F(2.373, 18.98) = 400.2, P = 0.0001), and genotype × time interaction (F(2.373, 18.98) = 60.24, P = 0.0001). Šidák’s multiple comparisons test: PRC1 i2KO vs control, 3 M (t(4) = 11), P = 0.0023, 4 M (t(8) = 8.083, P = 0.0002), 5 M (t(4) = 9.798, P = 0.0036), 6 M (t(4) = 17.96, P = 0.0003), 7 M (t(8) = 17.32, P < 0.0001), and 8 M (t(4) = 22.05, P = 0.0002). c (Left) Back-skin images of 10 M control and PRC1 i2KO mice. c (Right) Whole-mount IF of H2AK119ub (red), CD34 (green), and DAPI (blue) in HF bulges of 10 M control and PRC1 i2KO skin. H2AK119ub and CD34 channels shown in grayscale; CD34(+) HFSCs are outlined with yellow dashed lines. d Quantification of HF morphology (n = 3 biologically independent mice per genotype; a total of 150 HFs were analyzed/group). Welch’s two-tailed t-test: t(3.8) = 18.50, P = 0.0001. e Flow cytometry quantification of percentage of HFSCs (n = 4 biologically independent animals from separate litters/group). One-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, α = 0.05): F(6,12) = 33.69, P = 0.3136 (2 M control vs PRC1 i2KO), 0.0845 (2 M control vs 10 M control), and 0.0016 (10 M control vs PRC1 i2KO). f HFSC colonies from 10 M control and PRC1 i2KO mice were cultured for 16 days. Left, colony number (n = 3 biologically independent replicates/condition, each with 3 technical replicates). Welch’s two-tailed t-test: t(3.1) = 4.72, P = 0.017. Right, colony size (n = 3 biologically independent replicates/condition, each with 3 technical replicates). Welch’s two-tailed t-test: t(3.9) = 4.9, P = 0.007. Error bars, mean ± SEM. Scale bar: 25 μm. (See also Supplementary Fig. 10).

Notably, by 10 months, PRC1 i2KO mice presented a thinning hair coat, which is often the consequence of HFSC exhaustion (Fig. 5c, left). IF analysis showed that while control HFs exhibited uniform CD34 expression, in PRC1-null HFSCs, CD34 was grossly downregulated (Fig. 5c, right), and ~51% of the bulges in PRC1 i2KO skin exhibited defective morphology (Fig. 5d). Flow cytometry analysis showed that 10 M PRC1 i2KO mice had a significant reduction in their HFSC pool compared to corresponding controls, a phenotype not observed in 2-month-old (2 M) animals (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Fig. 10c). When cultured on fibroblast feeder cells, 10 M PRC1 i2KO HFSCs made significantly smaller and lower number of colonies than 10 M control HFSCs (Fig. 5f), highlighting that repeated activation events not only lead to premature exhaustion but also diminish the regenerative potency of these SCs.

Together, these findings highlight the essential role of PRC1/H2AK119ub-mediated quiescence in preserving SC longevity, as its disruption leads to repeated activation, premature exhaustion, and diminished regenerative capacity over time.

H2AK119ub is a broad and conserved marker of stem cell quiescence

Many SCs maintain quiescence to preserve SC longevity and initiate activation for tissue regeneration and repair2,11. Given that our studies have identified that H2AK119ub-mediated repression is dynamic in HFSCs to conserve quiescence, we sought to determine if H2AK119ub is similarly dynamic across other SC systems between quiescent and activated cell states. First, we examined H2AK119ub dynamics in melanocyte stem cells (MeSCs) that reside in the base of the adult HF76,77. Primarily quiescent, MeSCs get activated during early anagen when they proliferate and differentiate into melanocytes that produce melanin, providing pigment to the newly regenerating HF76,77. IF analysis using the MeSC marker, DCT, revealed that H2AK119ub is significantly higher in MeSCs of telogen HFs when compared to MeSCs of anagen HFs (Fig. 6a). Next, we examined H2AK119ub dynamics in muscle stem cells (MuSCs). Again, mostly quiescent, MuSCs get activated upon injury to proliferate and differentiate into myoblasts, which then fuse to form new muscle fibers78. Hence, we looked at H2AK119ub status in PAX7+ quiescent MuSCs in uninjured muscle fibers and MYOD+ activated MuSCs in injured fibers. Indeed, H2AK119ub levels were significantly higher in quiescent MuSCs when compared to activated MuSCs (Fig. 6b). Lastly, we examined whether H2AK119ub-mediated repression is equipped when quiescence is induced in otherwise actively cycling SCs. To investigate this, we utilized the x-ray-induced reversible cell cycle arrest model in Drosophila germline stem cells (GSCs)79. During oogenesis, GSCs continually undergo self-renewing divisions to give rise to differentiating daughters that further differentiate to give rise to an oocyte80. Upon X-ray irradiation, the GSCs cease self-renewal divisions and enter a reversible state of quiescence, while the differentiating progenies undergo apoptosis to ensure the survival of the GSCs79. Therefore, we asked if H2AK119ub (H2AK118ub in flies) levels differ between actively cycling and x-ray-induced quiescent GSCs. IF analysis revealed that while H2AK118ub levels were almost undetectable in unirradiated GSCs marked with germline marker Vasa and spectrosome marker 1B1, the levels of this histone mark sharply increased in GSCs 24 h post-irradiation (Fig. 6c).

a IF of H2AK119ub (red), DCT (green), and DAPI (blue) in P60 telogen and P95 anagen skin sections from C57BL/6 mice showing H2AK119ub dynamics between quiescent (q) and activated (a) melanocyte stem cells (MeSCs). DCT and H2AK119ub channels shown in grayscale; MeSCs outlined with yellow dashed lines. Violin plot shows H2AK119ub intensity in qMeSCs and aMeSCs (n = 3 biologically independent replicates from separate litters/condition; a total of 113 and 117 MeSCs quantified/group). Welch’s two-tailed t-test: t(2.9) = 6.05, P = 0.0100). b (Top) IF of H2AK119ub (red), WGA (gray), PAX7 (green), and DAPI (blue) in uninjured muscle showing quiescent muscle stem cells (qMuSCs, yellow arrows). PAX7 and H2AK119ub channels shown in grayscale. b (Bottom) IF of H2AK119ub (red), WGA (gray), MYOD (green), and DAPI (blue) in injured muscle showing activated muscle stem cells (aMuSCs, yellow arrows). WGA and H2AK119ub channels shown in grayscale. Violin plot shows H2AK119ub intensity in qMuSCs and aMuSCs (n = 3 biologically independent replicates from separate litters/condition; a total of 40 and 44 MuSCs quantified/group). Welch’s two-tailed t-test: t(4) = 10.48, P = 0.0009. c IF of H2AK118ub (red), 1B1 (green), Vasa (gray), and DAPI (blue) in germaria from unirradiated and 24 h post-irradiated Drosophila ovaries. Vasa and H2AK118ub channels shown in grayscale; Germline stem cells (GSCs) outlined with yellow dashed lines. Violin plot shows H2AK118ub intensity in cycling and quiescent GSCs (n = 3 independent biological trials totaling 25 pairs of ovaries; a total of 185 and 200 GSCs quantified/group). Welch’s unpaired two-tailed t-test: t(3.62) = 7.18, P = 0.0036. All violin plots show the distribution of values; the central line = median; upper/lower lines = 75th/25th percentiles. Scale bar: 25 μm.

Together, these findings establish that H2AK119ub is a compelling marker of quiescent SCs and underscore its conserved function in SC biology of facilitating the fine-tuned control of SC activation and maintenance.

Discussion

Adult SCs exist in a delicate balance between quiescence and activation to preserve long-term tissue homeostasis and regeneration2. Although previous studies have shown that quiescence is an actively maintained state rather than a dormant state8,9,10,11, the precise molecular mechanisms that integrate extrinsic niche signals with intrinsic programs of transcriptional repression to maintain quiescence are largely unknown. Here, we identify H2AK119ub, a conserved repressive histone mark, which is a critical regulator of quiescence that functions as a molecular switch linking external niche signals with intrinsic transcriptional activities to maintain SC quiescence and longevity. By leveraging the cyclical nature of HFSC quiescence and activation to fuel HF regeneration, we uncover that H2AK119ub is dynamic between quiescence and the activated SC state. Inhibitory FGF signaling in the skin microenvironment is associated with high levels of H2AK119ub that directly represses proliferation-promoting genes in quiescent HFSCs. Loss of H2AK119ub in HFSCs shortens the quiescent phase and induces repeated rounds of HFSC activation and hair regeneration, ultimately leading to SC exhaustion—a hallmark of aging tissue81,82,83. Importantly, our findings extend beyond HFSCs, as H2AK119ub oscillates between quiescent and activated states in diverse SC types, including MeSCs, MuSCs, and Drosophila GSCs. These observations underscore a broadly conserved role for H2AK119ub in maintaining a state of quiescence that is critical for long-term SC longevity and function.

Our transcriptional studies unveiled that H2AK119ub enforces SC quiescence independently of known HFSC quiescence factors, such as NFATc1 and FOXC161,62, as their expression does not alter upon H2AK119ub loss. Instead, H2AK119ub directly represses a subset of cell cycle and proliferation-promoting genes in quiescent HFSCs. The alleviation of H2AK119ub-mediated repression of these genes results in a domino effect that establishes a transcriptional landscape that initiates HFSC activation. Furthermore, while timely SC activation is essential for tissue regeneration, our data highlight that maintaining quiescence is equally important to preserve long-term SC function. Indeed, with long-term loss of H2AK119ub-dependent quiescence, HFSCs undergo repeated rounds of activation and hair regeneration, ultimately leading to the premature onset of several aging-associated phenotypes, including thinning of the hair coat, defective HF bulge morphology, HFSC exhaustion, and decreased proliferative potential81,82,83,84,85. Together, these observations demonstrate that H2AK119ub not only serves as an epigenetic checkpoint for SC proliferation but also safeguards HFSC longevity.

Concomitant with cell-intrinsic factors, HFSC states are also regulated by the temporal and spatial dynamics of extrinsic signaling pathways23,24. Specifically, FGF18, a ligand expressed by the Krt6+ bulge niche cells adjacent to HFSCs, is essential for maintaining HFSC quiescence, with its expression downregulated prior to HFSC activation55,56. Although niche-derived FGF18 signaling is known to be indispensable for quiescence, the mechanism by which FGF18/FGF signaling governs the quiescent transcriptional program has remained largely unclear. Our data indicate that modulation of FGF signaling is coupled to changes in H2AK119ub levels associated with quiescence. Pharmacological inhibition of the FGF signaling pathway not only led to the selective reduction in H2AK119ub levels in HFSCs but also induced premature hair regeneration. In contrast, supplementation with recombinant FGF18 protein, when endogenous niche signaling was removed, preserved H2AK119ub levels and delayed HFSC activation. It is important to note that both pharmacologic inhibition and exogenous ligand delivery via intradermal injections affect multiple cell types within the skin; thus, the observed effects on H2AK119ub likely reflect both HFSC-intrinsic and non-cell-autonomous influences of the HF niche. Our analyses also revealed that levels of PRC1 components, RING1B and BMI1, were reduced following FGFR inhibition, suggesting that FGF signaling may influence PRC1 complex stabilization. Together, these findings highlight an important connection between extrinsic signaling and Polycomb-mediated repression and raise future questions about how FGF signaling regulates RING1B and BMI1 levels and PRC1 stability.

Our investigations probing H2AK119ub dynamics in other adult SC systems have uncovered a striking phenomenon: the modulation of H2AK119ub levels between quiescent and activated SC states is not limited to the HFSC. Intriguingly, in mice, H2AK119ub levels are high in both quiescent MeSCs and MuSCs and are downregulated upon activation. Importantly, this histone modification is reinstated when quiescence is induced in otherwise actively cycling Drosophila GSCs, suggesting that H2AK119ub-mediated transcriptional regulation is recruited for establishing a quiescent state. Together, these findings establish H2AK119ub as a broad and conserved marker of SC quiescence and identify an epigenetic signature directly linked to quiescence in both vertebrate and invertebrate model systems. Whether H2AK119ub controls quiescent-maintaining transcriptional programs in these SC systems, similar to its role in HFSCs, and if extrinsic cues from the niche influence H2AK119ub dynamics in these SCs remains an important area of further investigation.

In conclusion, our studies build upon and expand our understanding of Polycomb’s role in tissue regeneration and SC control, which has predominantly been investigated in the contexts of development and lineage specification86,87,88,89,90,91,92. This work now places PRC1/H2AK119ub activity at the center of adult SC states, revealing its capacity to respond dynamically to extrinsic inputs and reinforce the quiescent state essential for long-term SC viability. This underscores a paradigm in which a Polycomb-dependent epigenetic signature serves as a molecular integrator of environmental signals, safeguarding adult SC activity and function over extended time scales. Furthermore, the parallels between HFSC exhaustion observed upon H2AK119ub loss and that observed in physiologically aged skin81,82,83 broaden our understanding of how Polycomb-dependent control of SC states can directly influence SC longevity. These insights pave the way for new approaches investigating tissue aging and offer potential strategies for therapeutic modulation of epigenetic states to aid SC function in aging tissues.

Methods

Research within this publication complies with relevant ethical regulations. All experimental protocols using animals were approved by and in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines (Protocol No. LA11-00020) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (ISSMS).

Mouse strains

All experiments were performed in mice (Mus musculus) maintained on a C57BL/6J genetic background. Mice were housed in the Center for Comparative Medicine and Surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (ISMMS) in accordance with institutional IACUC guidelines. K15-CrePR (stock no. 005249) and Bap1flox/flox (stock no. 031874) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Ring1a-null and Ring1bflox/flox mice were provided by Dr. Vidal, and Ring1bI53A mice were provided by Dr. Wendy Bickmore. C57BL/6J wild-type mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory or Charles River Laboratories. Mice carrying conditional alleles (Ring1a-null; Ring1bflox/flox, Ring1a-null; Ring1bI53A/flox, and Bap1flox/flox) were crossed with K15-CrePR driver mice to generate experimental animals. Cre-negative littermates or mice carrying only floxed alleles without Cre were used as controls. Mice were genotyped by PCR using ear skin DNA extracted with DirectPCR Lysis Reagent (Viagen Biotech Inc) following the manufacturer’s instructions. C57BL/6J wild-type mice were used to examine chromatin-mark dynamics during the hair cycle (postnatal day (P) 21, P23, P26, and P28) by immunofluorescence and nuclear flow cytometry, and for intradermal injection assays at P60. K15-CrePR; Ring1a-null; Ring1bflox/flox (PRC1 i2KO), K15-CrePR; Ring1a-null; Ring1bI53A/flox (PRC1-I53A), and K15-CrePR; Bap1flox/flox (Bap1 iKO) mice were used for hair cycle studies, immunofluorescence, and HFSC colony assays. K15-CrePR; Ring1a-null; Ring1bflox/flox (PRC1 i2KO) mice at P70 and P75 were used for RNA-seq, with age-matched littermates as controls. P55 C57BL/6 wild-type mice and P68 PRC1 i2KO mice were used for CUT&RUN experiments. Both male and female mice were used for all experiments, with sexes balanced across groups. Mice were analyzed at defined developmental and postnatal time points appropriate to each experiment, ranging from postnatal day 21 (P21) to 10 months of age.

Fly husbandry and strains

Drosophila melanogaster was grown on corn flour and agar media with brewer’s yeast at 25 °C. nosGAL4::NGT Drosophila strain was used as wild type in this study and was acquired from the Rangan Lab (ISSMS).

Intradermal injections and chemical induction

For intradermal injections, 5 mg of AZD4547 (Selleckchem, S2801) was dissolved in 1 mL DMSO and 4 mL of sterile PBS to reach a final concentration of 1 mg/mL. 100 μl of this solution was injected intradermally in the shaved dorsal skin of P60 C57BL6/J (wild type) for 5 consecutive days. The control side was injected with 100 μl of Vehicle (PBS+ 1% DMSO) solution. Samples were collected from P65 (1 day post-injection (d.p.i)), P67 (3 d.p.i), P71 (7 d.p.i), P74 (10 d.p.i), and P78 (14 d.p.i) animals. For FGF18 intradermal injection studies, 50 μg of recombinant human FGF18 protein (Biotechne, 8988-F18-050) was dissolved in 5 mL of sterile PBS to reach a final concentration of 10 μg/mL. 100 μl of this solution was injected intradermally in the shaved dorsal skin of P60 C57BL6/J (wild type) for 6 consecutive days. The control side was injected with 100 μl of sterile PBS. Animals were waxed 1 d.p.i on P66. Samples were collected from P68 (2 days post-waxing) and age-matched unwaxed control animals.

For RU-486 (Cayman Chemicals, 10006317) topical treatment to induce PRC1 ablation, I53A-mutation, and Bap1 ablation, RU-486 was dissolved in 100% ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) to a final concentration of 10 mg/ml. 100 μl of RU-486 was topically applied on shaved dorsal skin of P50 once per day for 10 days. Control mice were treated with the same amount of 100% ethanol.

Hair cycle analysis and depilation studies

Hair cycle progression was documented by standardized photographs at the start of each experiment and bi-weekly thereafter. For testing hair coat recovery, the back skin of mice was shaved with an electric clipper. Anagen onset was determined by darkening of the skin followed by hair growth as previously described76. Once the hair coat recovery reached ~90% of the back skin, the mice were shaved again to monitor the entry into next anagen. Days taken to recover hair coat were calculated after the induction treatment was completed at P60 and were observed in three to five biological replicates from at least two independent litters. If hair coat was recovered in 50% of the back skin, it was measured as half a hair cycle.

For depilation studies, back skin of telogen P65 C57BL6/J (wild type) mice was shaved and depilated using wax strips (Sally Hensen). Skin samples were collected 48 h (2 days post-waxing) after depilation for epidermal whole-mount IF assay.

X-ray irradiation of flies

Prior to X-ray-irradiation exposure, 2- to 3-day-old flies were kept on cornmeal–agar medium augmented with yeast for 24 h at 25 °C. On the day of irradiation, one-half of the females were transferred to empty plastic vials and treated with 50 Gy of X-ray irradiation using the XRad320 (Precision X-Ray Irradiation) instrument. After irradiation, the flies were flipped into a new vial with cornmeal–agar medium, and ovaries were dissected out from irradiated and unirradiated flies, 24 h post-irradiation.

Immunofluorescence staining and microscopy

For epidermal whole-mount immunofluorescence (IF), we followed an established protocol93 with a few variations as follows. Skin samples were collected, and the adipose layer from the dorsal side was scraped off using a surgical scalpel. The scraped skin sample was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before cut into 4 × 4 mm square sections and incubated for 5 h in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes with 1 mg/mL Dispase (Gibco, 17-105-041) and 20 mM EDTA (Corning, 46-034-CI) solution in Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS) (Fisher Scientific, MT21031CV) at 37 °C on a shaker set at 100 rotations per minute (rpm). After incubation, the epidermal layer was carefully peeled away from the dermis using an S-shaped tweezer and was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Electron Microscopy Sciences) in PBS on a nutator. After fixing, tissue samples were washed twice with PBS for 10 min. Samples could be stored for up to 3 weeks at 4 °C. If proceeding with the assay samples were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-X in PBS for 30 min on a nutator. Following permeabilization, samples were washed twice with PBS for 10 min and blocked for 2 h at RT with blocking solution [1% Triton-X-100, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.01% Gelatin, and 0.25% normal donkey serum]. Primary antibodies (listed below) were diluted in blocking solution, and incubations were carried out overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation in secondary antibodies for 2 h at RT. Slides were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma, 32670-5MG-F) and mounted using antifade mounting media.

For IF staining of skin sections, skin samples were collected and embedded into Tissue-Tek optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound blocks (Electron Microscopy Sciences, 62550-12) and cut into 9-μm sections using a Leica Cryostat (CM3050-S). Slides were either stored at 80 °C or used to proceed with the assay. Slides were fixed for 10 min in 4% PFA in PBS. Following couple of washes with PBS, the sections were outlined with a hydrophobic barrier pen (ImmEdge PAP Pen, Vector Laboratories, H-4000) and blocked for 2 h at RT or overnight at 4 °C in PBS with blocking solution. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution, and incubations were carried out for 1 h at RT or overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation in secondary antibodies for 2 h at RT. Slides were counterstained with DAPI and mounted using antifade mounting media. Primary antibodies were used as follows: Rabbit anti-H2AK119ub (Cell Signaling, 8240S, 1:500), Rabbit anti-H3K4me3 (Abcam, ab8580, 1:1000), Rabbit anti-H3K27me3 (Cell Signaling, 9733S, 1:500), Rat anti-CD34 (eBiosciences, 14-0341-82, 1:100), Rabbit anti-SOX9 (Abcam, ab185966, 1:200), Rabbit anti-Activated CASAPASE 3 (R&D systems, AF835, 1:100), Rabbit anti-P19ARF (Abcam, ab80, 1:200), Rabbit anti-RING1B (Cell Signaling, 5694S, 1:100), and Rabbit anti-BMI1 (Cell Signaling, 5856S, 1:100).

For IF staining of muscle sections, injured and uninjured whole muscles were isolated as previously described94. Whole muscles were mounted in 10% w/v tragacanth gum (Alfa Aesar, A18502) and snap frozen in 2-methylbutane (Fisher Scientific, O3551-4) before being transferred to a −80 °C freezer for storage. Frozen TA muscles were sectioned at 10 μm and collected on positively charged slides. The slides were fixed with 4% PFA and rinsed in PBS prior to being permeabilized in −20 °C methanol for 6 min and washed with PBS. Antigen retrieval was performed using 0.01 M citric acid buffer (pH 6.0) at 90 °C for 10 min. Slides were washed again in PBS, blocked in blocking solution for 2 h at RT, and primary antibodies were added to incubate overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation in secondary antibodies for 2 h at RT. Slides were counterstained with DAPI and mounted using antifade mounting media. Primary antibodies were used as follows: Rabbit anti-H2AK119ub (Cell Signaling, 8240S, 1:500), Mouse anti-Pax7 (DSBH, Pax7-c, 1:100), Mouse anti-MyoD (BD Biosciences, 554130, 1:100). The basal lamina was labeled with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)-488 (10 μg/ml; Invitrogen, W11261).

For IF staining of Drosophila ovaries, ovaries were dissected in cold PBS and fixed in 4% PFA for 20 min at RT. The ovaries were then permeabilized in 1 mL of PBST [PBS, 0.2% Tween-20, and 1% of Triton-X] followed by blocking solution (as above). Primary antibodies were diluted in 0.5 mL of blocking solution, and incubated overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation in secondary antibodies for 2 h at RT. The following steps were then carried out at RT. After incubation, ovaries were washed three times in PBST. An additional wash for 30 min was carried on by adding 2% Donkey serum to 1 mL of PBST. After the last wash 0.5 mL of secondary antibody in blocking solution was added, and ovaries were incubated for 2 h protected from light. After the incubation, ovaries were washed in 1 mL of PBST for five times. After the washes, one drop of Vectashield was added, and then the tissue was mounted on a glass slide, and a coverslip was placed on the slide. The primary antibodies used, and dilutions are listed as follows: Chicken anti-Vasa (1:500 dilution, Rangan Lab), Mouse anti-1B1 (DSHB, 528070, 1:20), Rabbit anti-H2AK119ub (Cell Signaling, 8240S, 1:500).

All secondary antibodies used were raised in a donkey host and used at 1:500 concentration and acquired from Jackson Immunoresearch Labs. The catalog numbers are as follows: Anti-rat Alexa Fluor 488 (712-545-150), Anti-rat Alexa Fluor 647 (712-605-150), Anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (711-545-152), Anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (711-585-152), Anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 (711-605-152), Anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 (715-605-150), and Anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (715-545-150).

Slides were imaged using Leica DM5500 slide microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) with 40× objective. Epidermal whole-mount samples and fly ovaries were imaged using the LAS X software (Leica Application Suite X 4.3.0.24308) on Leica Stellaris 8 (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) confocal microscope with the 40×/1.3 HC PlanApo oil immersion lens (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). Images were processed using the NIH ImageJ software (v2.14.0/1.54f) and are presented as maximum intensity projection images or a single Z stack. Images were further processed using Adobe Photoshop (v.20.0.3) and assembled into panels using Adobe Illustrator (v.24.0).

Immunofluorescence quantification

Confocal images were acquired under identical settings and processed in NIH ImageJ (v2.14.0/1.54f). Individual stem cell nuclei were outlined using DAPI signal, and mean gray values for histone modifications or other proteins were quantified after background subtraction. Intensity distributions for all cells were plotted as violin plots, while statistical analyses were performed on per-animal means (≥3 independent biological replicates). Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (v.9.5.1), with tests and sample sizes reported in the figure legends.

EdU pulse-chase experiment

Mice were injected with 125 μg of EdU (Thermo Fisher, E10187) in solution. Skin samples were collected 2 h after injection and were either embedded in OCT or collected for epidermal whole-mount IF. Slides or whole-mount samples were fixed and permeabilized as described above, followed by a 30-min incubation with a Click-iT reaction cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C10340 or C10637). Samples were washed twice with 3% BSA before proceeding with IF assay as described above. HFs positive for EdU incorporation in the bulge and hair germ region were considered activated, and the percentage of proliferative HFs was determined by counting 56 HFs in each biological replicate across all time points.

Nuclear flow cytometry

For detection of histone modifications in HFSCs of mice of different ages, P21, P23, P26, and P55, all time points were analyzed at the same time, and the experiment was repeated with three independent litters. The back skin from adult mice was collected, and the adipose layer from the dorsal side was scraped off using a surgical scalpel. The scraped skin sample was washed with PBS prior to incubation with 0.25% Trypsin/EDTA (Fisher, 25-053-CI) at 37 °C for 1 h on a rotation plate set at 60 rpm. After incubation, the epidermal cells, including the HFSCs, were scraped off from the trypsinized skin into the plate. 25 mL of E-media was added to the cell suspension and was then sequentially strained through 100 μm and 40 μm filters. The cell pellet was washed twice with DPBS. Cells were stained with Zombie Violet™ Fixable Viability Kit (Biolegend, 423114) for 10 min on ice. Cells were washed twice with DPBS prior to fixing using fresh solution with a final concentration of 1% formaldehyde (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 28906) for 10 min at RT. Crosslinking was stopped by the addition of Glycine (final concentration 125 mM). Cells were washed twice with DPBS before freezing in 90%FBS/10%DMSO. Once HFSCs from all experimental samples were collected, the frozen cell suspension was thawed on ice and washed with DPBS. Cells were first stained with PE-Sca-1 (1:200, Biolegend, 108108), APC/Cy7-α6-integrin (1:200, Biolegend, 313628), and FITC-CD34 (1:20, Thermo Fisher, 11-0341-82) in staining buffer (HBSS + 2% Fetal Bovine Serum) for 30 min on ice and then washed twice with DPBS. Cells were then permeabilized with 200 μl of permeabilization buffer (0.2% Triton-X-100 in DPBS) for 15 min at RT. Primary antibodies (histone modifications listed in the “Immunofluorescence staining and microscopy” section) were added directly at 1:1000 dilution into the permeabilized cells and further incubated for 25 min at RT. Cells were washed once with 2 mL of permeabilization buffer and centrifuged at 800 × g for 7 min, before resuspending in 200 μl of permeabilization buffer with secondary antibodies (Anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate) diluted at 1:500 concentration and incubated for another 25 min at RT. A fraction of the cells was also stained with just secondary (2°) antibodies to serve as a negative control. Cells were pelleted at 800 × g and washed twice with staining buffer before proceeding with analysis using a benchtop flow cytometer (BD) in the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at ISMMS. HFSCs were identified as Sca-1-, α6-integrinhigh, and CD34+. FACS strategy plots were generated using FlowJo portal (10.10.0), and the percentage of histone modification (+) HFSCs was identified.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

FACS isolation of HFSCs from the back skin of P70 control, P70 PRC1 i2KO, P70 PRC1-I53A, P70 Bap1 iKO, 10-month (M) control, and 10 M PRC1 i2KO mice was performed as follows. The back skin from adult mice was collected, and the adipose layer from the dorsal side was scraped off using a surgical scalpel. The scraped skin sample was washed with PBS prior to incubation with 0.25% Trypsin/EDTA at 37 °C for 1 h on a rotation plate set at 60 rpm. After incubation, the epidermal cells, including the HFSCs, were scraped off from the trypsinized skin into the plate. 25 mL of E-media was added to the cell suspension and was then sequentially strained through 100 μm and 40 μm filters and centrifuged at 300 × g. The cell pellet was washed twice with DPBS before proceeding with staining with cell surface markers. The cells were stained with 1:200 PerCP-Cy5.5-Sca-1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 45-5981-82), 1:200 FITC-α6-integrin (eBioscience, 11-0493-81), 1:100 APC-EpCAM (Biolegend, 324207), and 1:20 Alexa700-CD34 (eBioscience, 56-0341-82) in staining buffer (HBSS + 2% Fetal Bovine Serum) for 30 min on ice, centrifuged at 300 × g, and cell pellet was washed twice with DPBS before cell sorting. HFSCs were sorted by gating on EpCAM+, Sca-1-, α6-integrinhigh and CD34+. All cell isolations were performed on a FACS Influx instrument (BD) in the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at ISMMS. FACS strategy plots were generated using FlowJo portal (10.10.0). Additionally, percentage of HFSCs at different ages in control and PRC1 i2KO mice was determined.

Colony formation assay

FACS-purified HFSCs from back skin of P70 control, P70 PRC1 i2KO, P70 PRC1-I53A, P70 Bap1 iKO, 10-month (M) control, and 10 M PRC1 i2KO were plated on mitomycin C (Fisher Scientific, BP25312)-treated J2 fibroblast feeders at a density of 10,000 cells/well in 12-well plates in E-media supplemented with 15% (v/v) serum and 0.3 mM calcium as described as per established protocols95. After significant colonies were formed either in control or KO wells, cells were fixed and stained with 1% (wt/vol) Rhodamine B (Millipore Sigma, R6626). Colony analysis was performed in ImageJ (v2.14.0/1.54f). Colony numbers were quantified from scanned plate images, and colony area was determined by measuring colony diameters and calculating the percentage of plate area covered by colonies.

RNA purification, RT-qPCR, and RNA-sequencing library preparation

A total of 50,000 FACS-purified cells were collected directly into the RLT Plus buffer (QIAGEN, 1053393), and RNA was purified from these sorted cells with the RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (QIAGEN, 74034). DNase I treatment (QIAGEN, 79254) was performed during the purification step according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was reverse transcribed from total RNA using qScript cDNA Supermix (Quanta Biosciences, 101414-106) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were analyzed by RT-qPCR using LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche) on a Roche LightCycler 480 instrument. Primer information is available in Supplementary Table 1.

For RNA-seq library preparation, sample quality was measured using an Agilent Bioanalyzer. Only samples with RNA integrity numbers of >8 were used for library preparation. For generating RNA-seq libraries, 50 ng of total RNA was subjected to polyadenylate selection using Universal Plus mRNA-Seq with NuQuant (TECAN, 0520-A01). Following elution, mRNA was subjected to fragmentation at 94 °C for 8 min. First-strand, second-strand cDNA synthesis, end repair, adapter ligation, and amplification were carried out by following the manufacturer’s instructions.

RT-qPCR analysis and strategy

Fold change in mRNA levels of Ascl2, Lhx2, CD34, and Bap1 in HFSCs isolated from P70 control and P70 Bap1 iKO mice was calculated by first averaging the Ct values of technical replicates from each trial. ΔCt was calculated by subtracting Gapdh Ct average from the Ct average of AEGs. Then, the 2−ΔCt was calculated for each trial. Fold change was then calculated by dividing Bap1 iKO 2−ΔCt by control 2−ΔCt. Bar graph is presented as mean ± SD. Three animals for each group from at least two independent litters were used. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism software (v.9.5.1). Primer details are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA-seq analysis and data visualization

Paired-end RNA-seq reads were aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm39) using STAR aligner (v2.7.9a)96. Three samples each for control and PRC1 i2KO were processed but one control in P70 and one in P75 samples were excluded for further analysis due to low quality. Gene expression levels (from the Ensembl annotation v105, both coding and noncoding) were quantified using the RSEM software (v1.3.3) to estimate counts and TPMs (transcript per million)97. Differential expression analysis was performed for protein-coding genes using DESeq2 (v1.38.2)98 after excluding genes with TPM < 1 in all samples. Genes reaching P value < 0.05 and log2-transformed fold change >1.5 (or <−1.5) were considered to be significantly differentially expressed. Volcano plots were generated using the SRPlot web tool99.

Gene ontology and gene-set enrichment analysis

Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed using the database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery (DAVID) web-accessible tool100. For GSEA analysis of PRC1 i2KO HFSCs, all protein-coding genes were ranked by multiplication of their fold change direction with −log10(p value), and this pre-ranked gene list was used as input for the GSEA tool (GSEA_4.1.0). The gene set for GSEA was a previously defined Anagen-enriched gene list64.

Cleavage under targets and release using nuclease (CUT&RUN) analysis and data visualization

120,000 FACS-enriched quiescent HFSCs were isolated from the back skin of P55 C57BL/6 wild-type mice and P68 PRC1 i2KO mice. Two independent biological replicates were included for each condition, and IgG control was used to confirm the specificity of enrichment. CUT&RUN was conducted using the CUTANA™ ChIC/CUT&RUN Kit (Epicypher, 14-1048) following a previously described protocol optimized for FACS-isolated epidermal keratinocytes101. Sequencing libraries were generated using NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, E7645L) and NEBNext Multiplex Oligos (NEB, E6609L) for Illumina following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR-amplified libraries were purified using 1X ratio of Agencourt AMPure-XP Beads (Beckman) and eluted in 15 μl TE buffer.

All libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq using 150 bp paired-end reads. Reads were trimmed with Trim Galore (v0.6.7) and aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm10) using Bowtie2 (v.2.2.5). Deduplicated reads were removed using samtools (v.1.14). Peaks were identified using a sliding window method to determine genomic regions with >1.5 mapping read enrichment over IgG control and adjusted p < 0.05. CUT&RUN read density heatmaps were generated to show H2AK119ub signal intensity at promoters (±5 kb of transcription start sites) in both P55 wild-type and P68 PRC1-null HFSCs, and similarly for anagen-enriched genes that were upregulated in P70 PRC1-null HFSCs. Genes in the heatmaps were ordered by signal intensity in wild-type HFSCs. The BAM file for each replicate was converted to a TDF file for Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software, normalized by sequencing depths.

Statistical and reproducibility

All data from every experiment were included for analysis, unless explicitly noted (e.g., low-quality RNA-seq samples were excluded). Statistical methods were not used to predetermine sample size. Animals were randomly assigned to experimental groups, and measurements were taken from independent biological samples, unless otherwise stated. Graphs were generated and statistical analyses performed using GraphPad Prism (v9.5.1). Sample sizes, number of replicates, and specific tests are indicated in figure legends. Violin plots display all individual data points, whereas statistical analyses were performed on mean values from biological replicates, as reported in the legends.

Statistical tests included two-way ANOVA, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s or Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, Welch’s two-tailed t-tests, and Mann–Whitney tests, as appropriate. For ANOVA, F-values and degrees of freedom are reported in figure legends. A significance threshold of P < 0.05 was applied. Data are reported as mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated. Assumptions of normal distribution and equal variance were considered but not formally tested; Welch’s correction was applied when variances were unequal. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.001, *** indicates P < 0.0001, and **** indicates P < 0.00001.

Covariates such as mouse age and litter of origin were considered across experiments. Male and female mice were used interchangeably, and sex was not treated as a biological variable. Randomization was not applicable, as experimental groups were defined by age or genotype. For immunofluorescence quantifications, image thresholding and intensity measurements were performed using standardized settings to minimize bias. Whenever representative images are shown, comparable results were obtained from ≥3 independent biological replicates (from separate litters of mice or independent cell culture experiments performed on different days).

Graphical illustrations and figure assembly

All figure panels and graphical illustrations were generated by the authors. Schematic and model illustrations in Supplementary Figs. 4a and 6a, d were created using Apple Keynote to design shapes and layouts, which were then exported and refined in Adobe Illustrator (v.24.0) for final composition. The mouse and syringe graphical elements in Supplementary Fig. 7a, h were created in BioRender.com under an institutional license (Ezhkova, E. (2025) https://BioRender.com/91jrd3v). No other third-party, stock, or previously published images were used.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or in the Supplementary Data. The accession number for previously published bulk RNA-seq comparing telogen and anagen HFSCs to identify anagen-enriched genes is GSE172082. The accession numbers for the P70 and P75 HFSC bulk RNA-seq are GSE279012 and GSE279013, respectively. The accession number for the CUT&RUN data is GSE279014. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Simons, B. D. & Clevers, H. Strategies for Homeostatic stem cell self-renewal in adult tissues. Cell 145, 851–862 (2011).

de Morree, A. & Rando, T. A. Regulation of adult stem cell quiescence and its functions in the maintenance of tissue integrity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 334–354 (2023).

Fuchs, E. & Chen, T. A matter of life and death: self-renewal in stem cells. EMBO Rep. 14, 39–48 (2013).

Fuchs, E. & Blau, H. M. Tissue stem cells: architects of their niches. Cell Stem Cell 27, 532–556 (2020).

Barker, N., Bartfeld, S. & Clevers, H. Tissue-resident adult stem cell populations of rapidly self-renewing organs. Cell Stem Cell 7, 656–670 (2010).

Wodarz, D. Effect of stem cell turnover rates on protection against cancer and aging. J. Theor. Biol. 245, 449–458 (2007).

Tümpel, S. & Rudolph, K. L. Quiescence: good and bad of stem cell aging. Trends Cell Biol. 29, 672–685 (2019).

Cheung, T. H. & Rando, T. A. Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3591 (2013).

Marescal, O. & Cheeseman, I. M. Cellular mechanisms and regulation of quiescence. Dev. Cell 55, 259–271 (2020).

Urbán, N. & Cheung, T. H. Stem cell quiescence: the challenging path to activation. Development 148, dev165084 (2021).

van Velthoven, C. T. J. & Rando, T. A. Stem cell quiescence: dynamism, restraint, and cellular idling. Cell Stem Cell 24, 213–225 (2019).

Chacón-Martínez, C. A., Koester, J. & Wickström, S. A. Signaling in the stem cell niche: regulating cell fate, function and plasticity. Development 145, dev165399 (2018).

Cai, Y., Wang, S., Qu, J., Belmonte, J. C. I. & Liu, G.-H. Rejuvenation of tissue stem cells by intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 11, 231–238 (2022).

Morrison, S. J. & Spradling, A. C. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell 132, 598–611 (2008).

Paus, R. & Foitzik, K. In search of the ‘hair cycle clock’: a guided tour. Differentiation 72, 489–511 (2004).

Ji, S., Zhu, Z., Sun, X. & Fu, X. Functional hair follicle regeneration: an updated review. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 1–11 (2021).

Alonso, L. & Fuchs, E. The hair cycle. J. Cell Sci. 119, 391–393 (2006).

Gonzales, K. A. U. & Fuchs, E. Skin and its regenerative powers: an alliance between stem cells and their niche. Dev. Cell 43, 387–401 (2017).

Fuchs, E. Skin stem cells in silence, action, and cancer. Stem Cell Rep. 10, 1432–1438 (2018).

Hsu, Y.-C. & Fuchs, E. Building and maintaining the skin. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 14, a040840 (2022).

Tumbar, T. et al. Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science 303, 359–363 (2004).

Rompolas, P. & Greco, V. Stem cell dynamics in the hair follicle niche. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 0, 34–42 (2014).

Yi, R. Concise review: mechanisms of quiescent hair follicle stem cell regulation. Stem Cells 35, 2323–2330 (2017).

Lee, S. A., Li, K. N. & Tumbar, T. Stem cell intrinsic mechanisms regulating adult hair follicle homeostasis. Exp. Dermatol. 30, 430–447 (2021).

Li, G. & Reinberg, D. Chromatin higher-order structures and gene regulation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 21, 175–186 (2011).

Lawrence, M., Daujat, S. & Schneider, R. Lateral thinking: How histone modifications regulate gene expression. Trends Genet. 32, 42–56 (2016).

Bannister, A. J. & Kouzarides, T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 21, 381–395 (2011).

Liu, L., Jin, G. & Zhou, X. Modeling the relationship of epigenetic modifications to transcription factor binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 3873–3885 (2015).

Swift, J. & Coruzzi, G. A matter of time—How transient transcription factor interactions create dynamic gene regulatory networks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1860, 75–83 (2017).

Suter, D. M. Transcription factors and DNA play hide and seek. Trends Cell Biol. 30, 491–500 (2020).

Cheung, P., Allis, C. D. & Sassone-Corsi, P. Signaling to chromatin through histone modifications. Cell 103, 263–271 (2000).

Suganuma, T. & Workman, J. L. Signals and combinatorial functions of histone modifications. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 473–499 (2011).

Baek, S. H. When signaling kinases meet histones and histone modifiers in the nucleus. Mol. Cell 42, 274–284 (2011).

Cohen, I., Bar, C. & Ezhkova, E. Activity of PRC1 and histone H2AK119 monoubiquitination: revising popular misconceptions. Bioessays 42, e1900192 (2020).

Tamburri, S. et al. Histone H2AK119 mono-ubiquitination is essential for polycomb-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell 77, 840–856.e5 (2020).

Barbour, H., Daou, S., Hendzel, M. & Affar, E. B. Polycomb group-mediated histone H2A monoubiquitination in epigenome regulation and nuclear processes. Nat. Commun. 11, 5947 (2020).

Blackledge, N. P. & Klose, R. J. The molecular principles of gene regulation by Polycomb repressive complexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 815–833 (2021).

Flora, P., Dalal, G., Cohen, I. & Ezhkova, E. Polycomb repressive complex(es) and their role in adult stem cells. Genes 12, 1485 (2021).

de Napoles, M. et al. Polycomb group proteins Ring1A/B link ubiquitylation of histone H2A to heritable gene silencing and X inactivation. Dev. Cell 7, 663–676 (2004).

King, I. F. G., Francis, N. J. & Kingston, R. E. Native and recombinant polycomb group complexes establish a selective block to template accessibility to repress transcription in vitro. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 7919–7928 (2002).

Kundu, S. et al. Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 generates discrete compacted domains that change during differentiation. Mol. Cell 65, 432–446.e5 (2017).

Illingworth, R. S. Chromatin folding and nuclear architecture: PRC1 function in 3D. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 55, 82–90 (2019).

Dobrinić, P., Szczurek, A. T. & Klose, R. J. PRC1 drives Polycomb-mediated gene repression by controlling transcription initiation and burst frequency. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 28, 811–824 (2021).

Wang, H. & Helin, K. Roles of H3K4 methylation in biology and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 35, 115–128 (2025).

Di Croce, L. & Helin, K. Transcriptional regulation by Polycomb group proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 1147–1155 (2013).