Abstract

On November 1st, 2023, the Lucy spacecraft encountered the main-belt asteroid Dinkinesh, revealing the first confirmed contact binary moon, (152830) Dinkinesh I Selam. Here, we show that Selam likely formed through a series of low-velocity collisions of similarly sized moonlets that once orbited the primary. To gain insight into the processes that shape satellites in small binary systems, we simulate plausible formation scenarios for Selam. The mergers that form each lobe are consistent with collisions that occur beyond four primary radii at impact velocities between 1 and 1.5 times their mutual escape velocity and impact angles between 5 and 15∘. Similar collisions could also explain the oblate shape of asteroid Dimorphos, the secondary in the Didymos system and the target of NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), though further data from ESA’s Hera mission will provide additional insights. These results indicate that binary asteroid systems can undergo multiple moon-forming events and exhibit a wider diversity of satellite shapes than currently observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Previously, binary asteroids were assumed to comprise a top-shaped primary body and a prolate secondary body (e.g., ref. 1). However, recent space missions that imaged the Dinkinesh-Selam2 and Didymos-Dimorphos3 systems have revealed that the secondaries of these systems can exhibit a variety of shapes. Dinkinesh (about 719 m) and Didymos (about 730 m) are comparable in spectral type4,5,6 and size2,7. Both of the primaries of Didymos and Dinkinesh share the distinctive top-shape with other small asteroids (e.g., refs. 8,9,10,11), suggesting a history of mass shedding or dynamic processes shaping their surface12. However, Selam, a contact binary2 and Dimorphos, an oblate body7,13, deviate from the expected prolate shape of secondary bodies. These shapes are uncommon in previously investigated formation models (e.g., refs. 14,15), suggesting that other pathways must exist.

Here, we recreate the shapes and geological features of Selam and Dimorphos from low-velocity moonlet mergers, and explore their evolutionary histories. We combine findings from three-dimensional impact simulations with dynamical simulations to find the most likely scenarios consistent with these types of low-velocity mergers.

Results

We first show that both Selam and Dimorphos likely result from mergers between similarly-sized moonlets orbiting a larger primary asteroid16,17. The resulting shape following a collision depends on the angle (ϕ) and the relative velocity normalised by the mutual escape velocity (v/vesc) between the colliding moonlets, but also their initial mass, shape and structure. In our smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) simulations using the Bern SPH code, we assume that both merging moonlets have the same properties and structure, are initially spherical, and vary the impact angle and velocity. Assuming spherical initial bodies is a necessary simplification to reduce the number of impact scenarios explored. However, for moonlets with varying triaxial ellipsoid axis ratios (a/b ranging from 1 to 1.5), similar collision outcomes can be achieved by adjusting the impact speed and/or angle (see Supplementary Fig. 1).

Each moonlet in our impact simulations is modelled as a rubble pile, formed from the gravitational collapse of a cloud of spherical particles with a power-law size-frequency distribution (see Methods, subsection Moonlets structure). Due to resolution constraints, we explicitly model only boulders larger than 2.5 metres in radius. These boulders are modelled using a fracture model18,19 with a tensile strength of YT = 10 MPa. Smaller components are considered part of the matrix and represented as granular material, resulting in a boulder-to-matrix volume ratio of approximately 25%. The matrix material’s response to shear deformation is described by a simple pressure-dependent strength model20, with the shear strength at zero pressure (cohesion) set to Y0 = 0 Pa. This represents a lower-bound scenario, but our cohesion sensitivity analysis shows that the outcome of low-velocity mergers remains largely unchanged for small but non-zero cohesion values (e.g., Y0 ≲ 1 Pa). The coefficient of internal friction is set to f = 0.65, corresponding to an angle of repose of θ = 35∘, which is the best estimate derived for asteroid surfaces [e.g., refs. 21,22,23].

S/Sq-type asteroids such as Dinkinesh and Didymos are likely progenitors of L/LL-chondrite meteorites6,24,25, with grain densities of ρg = 3500 kg/m3 and microporosities around 8–10%26. The bulk density of Dinkinesh is estimated to be ρ = 2400 ± 350 kg/m32. We model Selam using the same bulk density as Dinkinesh, assuming a boulder porosity of 10% and a combined macro- and microporosity of 45% for the matrix.

The moonlet collisions are simulated in a co-rotating frame, incorporating self-gravity, tidal and rotational effects. We track outcomes up to 24 h post-impact using a low-sound speed deformation approach27,28,29.

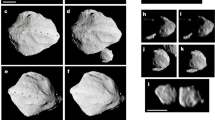

Selam’s two lobes (Fig. 1) are nearly identical in size, measuring approximately 210 metres and 230 metres in diameter, respectively, and they exhibit several distinctive geological features2.

Images of Dinkinesh and Selam from Lucy’s close-approach campaign2, taken at (a, b) −2.29 min (lor_0752129452_03580_00001_1 × 1_sci_03); (d, e) −0.21 min (lor_0752129590_03608_00001_1 × 1_sci_03); (g, h) 0.66 min (lor_0752129617_03613_00001_1 × 1_sci_03); and at departure j, 6.16 min (lor_0752129947_03679_00001_1 × 1_sci_03). The times are given relative to the close approach. c, f, i High resolution SPH simulation of Selam A at t = 24 h after merger. Selam B is shown for context only and was not included in these runs. k SPH simulations containing both Selam A and Selam B merged into a single body, at t = 24 h post-merger. In this case, the post-impact shapes of Selam A and Selam B were obtained from earlier moonlet collision simulations. The results demonstrate that geological features formed during prior mergers can be preserved through subsequent low-velocity collisions. In panels (c, f, i, k), yellow denotes highly strained and displaced material (total integrated strain > 1); grey indicates relatively unmodified regions. Images of asteroid Dinkinesh are courtesy of NASA and the NASA Planetary Data System (PDS).

The inner lobe, henceforth referred to as Selam A, features a pronounced ridge-like structure that wraps around more than half of the lobe (Fig. 1a–i). This ridge appears to demarcate the boundary between flat facets, and it is orientated at an angle of about 50 degrees with respect to the orbital plane and the ridge on Dinkinesh2.2 suggested that the ridge formed from the accretion of material from a Dinkinesh-centred disk, similar to the formation of the Saturnian small inner moons. However, this explanation does not fully account for the narrow, well-defined morphology of the ridge. In contrast to the Saturnian case, where the ring is likely composed of fine-grained material, the Dinkinesh system-generated ring would likely be composed of boulder-rich, heterogeneous debris, leading to a more irregular and diffuse accumulation. Here, we propose an alternative mechanism in which the ridge forms at the interface of low-velocity mergers between similarly sized moonlets.

We explore low-velocity impacts in a 1:2 mass ratio, with velocities ranging between 1 and 2.5 times the escape velocity (vesc), colliding at impact angles between ϕ = 0∘ (head-on) and ϕ = 15∘ (Fig. 2a). The collisions occur at radial positions of approximately 4.5 primary radii (Rprimary). This location was chosen to minimise the influence of tidal forces from the primary; however, similar outcomes could be achieved at smaller distances, provided that tidal effects are not strong enough to separate the post-impact moonlets. During the merger, for velocities exceeding about 1.5 vesc, material is pushed out from the contact between the colliding bodies, giving rise to a ridge (Fig. 1c–i). While detailed surface properties cannot be fully resolved in the current Lucy imagery, the ridge crest appears to exhibit a slightly rougher texture, with more pronounced surface irregularities than the adjacent facet, based on visual inspection. This morphology is broadly consistent with the ridge formed in simulations of Selam A (Fig. 1f, i, Supplementary Fig. 2), where small boulders are pushed towards the top of the ridge. This ridge-forming mechanism, including upward boulder transport, is a general outcome in simulations with v/vesc ≳ 1.5, particularly for low-cohesion surfaces. However, we find that the presence and prominence of the ridge are highly sensitive to the internal structure of the merging moonlets, as discussed below.

The outcomes of collisions between bodies with initial mass ratios of (a) m1/m2 = 0.5 and (b) m1/m2 = 1 are examined, covering a range of impact angles ϕ and velocities v/vesc. The moonlets are initially spherical, porous rubble-pile aggregates, with an initial bulk density of ρ = 2400 kg/m3. The yellow regions correspond to highly deformed/ejected material (total integrated strain > 1). The mergers were simulated for up to 24 h, at a radial position of 4.5 Rprimary. Following the collision, the merged moonlets with ϕ > 0∘ enter in a tumbling state. The merger outcomes that best match the shapes of Selam A and B are shown in orange. Outcomes with oblate shapes resembling Dimorphos (identified based on similarity in triaxial axis ratios, a/b and b/c), are shown in blue and further evaluated in Fig. 5.

Our investigations into the formation of Selam A suggest that its distinct shape is the product of specific merging scenarios (v/vesc = 1.5–1.75, ϕ = 2.5–10∘; Fig. 2a). These outcomes were selected based on a qualitative comparison with available Lucy data, with particular emphasis on the presence of a well-defined ridge, overall elongation, and overall shape asymmetry (i.e., the northern side of the lobe appears more tapered than the other). High resolution models of one of these scenarios (5 × 106 particles) allow us to further study various rubble-pile configurations (Fig. 3). In the case of homogeneous targets and targets with a low boulder packing (< 22 vol%; Fig. 3b, c), the merger results in overly oblate final shape, compared to the observed Selam A (Fig. 3a). In contrast, increasing the volume fraction of the boulder to 38 vol% yielded the necessary shape, but it lacked a defining ridge (Fig. 3c). These findings provide constraints for the surface and internal structure of the moon. To form a distinctive ridge, the surface and shallow subsurface material of the merging moonlets, down to approximately 10–15 metres, must have very little cohesion (less than about 1 Pa) and a relatively sparse boulder distribution (less than about 22 vol%; Fig. 3c). However, to retain its spherical shape, the moonlet’s interior must possess a degree of stiffness, which can be achieved through the interlocking of large boulders and/or cohesion greater than about 10 Pa.

a Selam imaged at close approach by L'LORRI onboard Lucy2. SPH simulation of mergers between 100 m spherical bodies at v = 1.5 vesc and ϕ = 5∘, between: (b) two homogeneous lobes; (c) two lobes with homogeneous distribution of boulders and 22 vol% packing; (d) homogeneous distribution of boulders and 38 vol% packing; and (e) two lobes with high interior boulder packing and low surface packing, resulting in 25 vol% bulk packing. Yellow denotes highly strained and displaced material (total integrated strain > 1); grey indicates relatively unmodified regions.

The outer lobe, henceforth referred to as Selam B, presents a less defined set of characteristics. However, its notable polygonal shape is divided by a distinct lineament, oriented at about 70 degrees with respect to the lobe’s long axis and equatorial plane of Dinkinesh (Fig. 1j, Supplementary Fig. 3). Additionally, large boulders are observed bulging from the surface. We explore simulations of low-velocity impacts in a 1:1 mass ratio, with velocities ranging between 1 and 2.5 vesc, colliding at impact angles between 0 and 15∘ (Fig. 2b). We find that the observed shape of Selam B (a/b ratio = 1.32), as well as the orientation of the lineament relative to the body’s long axis, is best reproduced by collision scenarios with impact velocities of v/vesc = 1 to 1.25 and impact angles of ϕ = 5∘ to 15∘ (Fig. 2b).

The precise conditions under which Selam A and Selam B merged remain somewhat undefined. While the Lucy images do not clearly resolve the neck’s thickness connecting the two lobes, it is assumed to be sufficiently thin to maintain the visual separation of the two lobes2. A critical requirement is that the final merger preserves distinctive pre-impact geological features, such as the ridge on Selam A and the lineament on Selam B. To investigate this, we performed a high-resolution simulation using the actual post-impact shapes of Selam A and Selam B as initial conditions, rather than idealised spheres (Fig. 1k). Due to the high computational cost, the broader parameter space (impact velocities and angles) was explored using lower-resolution simulations with spherical progenitors. Our results show that low-velocity mergers at a 1:1 mass ratio and velocities between 0.75 and 2 vesc across a range of impact angles commonly yield outcomes consistent with the bi-lobe aspect of Selam (Fig. 4).

Targets had a high internal boulder packing (38 vol%). Simulations ran for up to 24 h at a radial distance of 5.5 Rprimary. A range of configurations (highlighted within the orange box) produced stable contact binaries resembling Selam’s current shape, while oblique, higher-velocity impacts led to hit-and-run outcomes with unstable, short-lived shapes. Yellow denotes highly strained and displaced material (total integrated strain > 1); grey indicates relatively unmodified regions.

For collisions occurring at radial positions beyond = 4.5 Rprimary, tidal forces exert less influence, allowing nearly all impacts at velocities below vesc to successfully create the desired moon configuration. However, as the distance to the primary decreases, the range of parameters conducive to forming stable contact binaries becomes more restricted (Supplementary Fig. 4). Closer to the primary, collisions with high obliquity (> 45∘) cause the two lobes to become unbound and separate, resulting in hit-and-run events [e.g., ref. 30]. While it is possible that the two lobes might subsequently merge after one or more orbits, this scenario is not simulated here and is likely to result in further deformation that could erase previous surface features.

Dimorphos

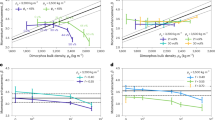

The shape of Dimorphos is also challenging to form via gravitational accumulation, which favours the formation of prolate objects [e.g., refs. 14,16]. Our findings indicate that oblate moons could also result from the low-velocity merger of two similarly-sized moonlets. Specifically, the shape of Dimorphos can be replicated through a merging collision at 2.25 vesc and ϕ = −15∘ (Fig. 5a), occurring beyond 3.3 Rprimary.

a Triaxial ellipsoid aspect ratios, a/b versus b/c, from impact simulations at 2 and 2.25 vesc, with impact angles ranging from −15 degrees (retrograde) to 15 degrees (prograde). Error bars represent 1σ uncertainties arising from shape measurement errors. Triaxial ellipsoid axis ratio that best matches Dimorphos [a/b = 1.06 ± 0.03; b/c = 1.47 ± 0.04;13] is plotted in blue. b The highest-resolution DRACO image (onboard DART) to contain all of Dimorphos (dart_0401930039_14119_01_iof. fits) with markings outlining the asteroid shape (blue). Image courtesy of NASA. c Dimorphos’s shape model13. d, e Bern SPH simulation that best matches Dimorphos’s outline and shape (v = 2.25 vesc and ϕ = − 15 degrees (retrograde)).

Unlike Selam, Dimorphos lacks distinct geological features, such as a ridge22, making its formation history more difficult to determine. If Dimorphos formed from a low-velocity merger similar to Selam’s lobes, the absence of prominent surface features could be due to its rugged terrain, where boulders relative to its size may prevent ridge formation (e.g., Fig. 3d). Previous impacts may have also erased any original features29. Although a comprehensive understanding of Dimorphos’s surface and formation history is still incomplete, ESA’s Hera mission is expected to provide valuable insights31.

Formation pathways of asteroid moons

Our findings suggest that some binary systems may originate from multi-moon systems in which similarly sized moons collide at velocities between approximately 0.75 to 2 vesc. This scenario complements those relying on the same Yarkovsky–O’Keefe–Radzievskii–Paddack (YORP) spin-up and/or collisional disruption event for satellite formation14,15,16,17,32,33.

Previous simulations of individual mass-shedding events [e.g., refs. 14,15] show that gravitational instabilities in the resulting disk can lead to the rapid formation of moonlets, which typically interact and merge at velocities near the mutual escape speed. However, these simulations often yield moonlets with highly unequal masses, and the resolution of current N-body models limits their ability to fully resolve individual moonlet properties, including shape and size distribution.

While it remains uncertain whether a single mass-shedding event can consistently produce multiple similar-mass moonlets, we note that such an outcome could plausibly arise from multiple, distinct shedding and moon-forming episodes34, as proposed in16,17.

Continuous YORP spin-up or impacts can trigger these episodes over time. For rubble-pile asteroids like Dinkinesh and Didymos, large-scale mass-shedding events are expected to occur over timescales exceeding 103 years12, significantly longer than the formation time of a single satellite14,15. In this scenario, each event could create a new satellite, surviving until the next instability. Over time, this process could evolve a single asteroid into a multi-satellite system, as proposed for Selam and Dimorphos.

Figure 6 shows the collision speed between equal-mass satellites, normalised to their mutual escape velocity, as a function of moonlet mass and distance from the primary. The orbital radius of these mergers is not limited to the current orbital radius of a body, as secondaries may migrate to their current orbits on longer timescales (e.g., Selam migrates to its current orbit in about 106 to 107 years35). The collision speeds were obtained by integrating the motion of two randomly-generated satellites using an N-body integrator up to the point of collision (See “Methods”, subsection Dynamical simulations). While some stochasticity arises due to specific impact conditions, gravitational interactions between low-mass satellites are weak, so their impact speeds are mainly governed by their Keplerian orbits. As satellite mass increases relative to the primary body, the normalised orbital velocity decreases, making collision speed less dependent on orbital distance. Most impacts occur at relative velocities around vesc, as satellites approach each other from a great distance at low speeds and are accelerated by mutual gravity. Our results indicate that mergers at approximately vesc (e.g., Selam B or between Selam A and B) are common, while 1.5 vesc, required for Selam A, can occur within 6 Rprimary but are less frequent.

The lobes that formed Selam are massive relative to the primary, meaning that their orbital velocity is small compared to their mutual escape velocity. In this regime, the collision velocity is weakly dependent on the orbital distance, and most collisions occur at about vesc owing to the mutual gravitational attraction of the two lobes, which increases their relative speed leading up to the collision. The mass of each satellite needed for the formation of Dimorphos is m = 5 × 10−3 × Mprimary.

However, we found that scenarios matching the conditions needed for Dimorphos’s formation (2 vesc) are unlikely, suggesting that if Dimorphos formed through moonlet merger, additional mechanisms to increase collision velocity are necessary.17 propose that the Lindblad resonance (LR) between merging satellites and an inner disk36 may enhance collision velocities. To test this hypothesis, we simulated two equal-mass satellites and a narrow ring of surface density of about \(0.1\,{M}_{{{{\rm{primary}}}}}/{R}_{{{{\rm{primary}}}}}^{2}\), centred at the 1:2 LR with the outer satellite, using a 1D hydrodynamical code. A narrow ring was adopted to isolate the specific effect of the 1:2 LR on the satellite (the main driver of migration), with similar results expected for an extended disk of equal mass concentrated at the resonance. Once the satellites entered each other’s Hill regions, we transitioned to a 3D N-body code to model the impact, incorporating the ring-induced torque from the hydrodynamical model (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The ring’s torque rapidly increases the speed of the outer satellite to nearly 2 vesc relative to the inner satellite. However, this requires implausibly specific conditions: a high-density ring near 2.15 Rprimary and torque acting only shortly before impact—sustained torques would otherwise cause divergent migration or ejection. Thus, despite its effectiveness in boosting velocities, this mechanism is very unlikely to explain Dimorphos’s formation. Other mechanisms that could increase the impact velocity include evection resonances37 or shape-induced increases in orbital speed38.

From this analysis, we suggest that Selam forms relatively easily, whereas the formation of Dimorphos might require additional conditions or mechanisms. If contact-binary satellites are indeed easy to form, given sufficiently massive satellites, why is Dinkinesh the first known system with such a satellite? Dinkinesh stands out due to the contact-binary nature of Selam and its relatively wide separation at 8Rprimary. This raises the possibility that systems like Dinkinesh are either common but overlooked due to observational biases or genuinely rare, and Lucy’s encounter was by chance.

It is plausible that Dinkinesh-like systems are indeed rare. Forming a wide, contact-binary satellite may require multiple spin-up and mass-shedding events within the primary’s collisional lifetime, along with convergent migration allowing satellite collisions. These factors may pose significant challenges to forming such systems efficiently. However, Lucy’s unexpected discovery of a contact-binary satellite around Dinkinesh, chosen as a typical main-belt asteroid, suggests that Dinkinesh-Selam systems might represent an unknown sub-population of small binaries. Lightcurve-based methods struggle to detect widely separated systems due to their long periods and rare mutual events39. Radar, while unaffected by this bias, has not detected a Dinkinesh-like system yet. However, radar observations are not fully representative of small binary populations due to selection effects, as they require asteroids to pass close to Earth.

Consequently, our current understanding of satellite shape diversity and formation mechanisms may be incomplete. To address this bias, more comprehensive observational campaigns and targeted missions are necessary to detect and study these binary asteroid systems in greater detail.

Method

Impact simulations

We conduct three-dimensional impact simulations using the shock-physics code Bern SPH18,19 to investigate the slow mergers of similarly-sized moonlets orbiting a larger primary. These simulations take into account a variety of assumed impact conditions, material properties, and interior structures of the moonlets. We then compute the resulting asteroid moon shapes.

The Bern Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (Bern SPH) code is a numerical tool developed to simulate shock physics and impact processes in planetary materials. Originating from early work on collisional fragmentation40,41, the code was later optimised for parallel computing42 and extended to include advanced material descriptions. The present version includes a porosity compaction model for porous material based on the P − α formulation18, a pressure-dependent strength model19,20,43, a tensile fracture model41, and self-gravity. The code has been applied to a wide range of impact studies, ranging from laboratory-scale experiments to large-scale planetary collisions. Code validation has been demonstrated through comparisons with experimental data, benchmark tests against other hydrocodes, and collaborative computational campaigns [e.g., refs. 19,44,45].

While originally developed for high-velocity impact scenarios, Bern SPH is also well suited for modelling the bulk behaviour of granular materials under low-velocity conditions, such as those relevant to the rubble-pile bodies investigated in this study. Its validity in this regime has been demonstrated through comparisons with laboratory experiments of granular cliff collapse19, showing good agreement with experimental run-out profiles and flow dynamics. Moreover, recent comparisons with Soft-Sphere Discrete Element Method (SSDEM) simulations28 confirm that Bern SPH reliably reproduces outcomes in the low-velocity regime like the ones addressed here.

That said, as a continuum method, SPH does not resolve individual grain contacts or frictional interactions explicitly, which can limit its ability to capture micro-scale phenomena such as contacts between individual boulders, inter-boulder friction, or boulder rearrangement. Frictional behaviour is approximated through bulk rheological models (see “Methods”, subsection Strength), which may underrepresent localised shear or grain interlocking. However, for the purposes of this study, which focuses on macroscopic material redistribution and global deformation, SPH offers a computationally efficient and sufficiently accurate approach. We therefore consider it an appropriate method, while acknowledging these limitations in the context of fine-scale contact dynamics.

Moonlets structure

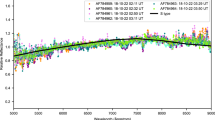

In our simulations, we assume that both merging moonlets have the same properties and structure. The moonlets are modelled as spherical rubble-piles, obtained from the gravitational collapse of a cloud of spherical particles. The boulder size–frequency distribution (SFD) in the cloud follows a power-law46,47. Under the assumption that Selam formed from the boulders accreted from the primary [as in the case of Didymos/Dimorphos;48], in our simulations of Selam’s formation, we adopt the same SFD slope of αs = −3, as derived from Dinkinesh’s surface49. This power-law slope best matches the boulder SFD on Itokawa [αs = −3.1 ± 0.147], while the boulders on Ryugu [αs = 2.65 ± 0.0550] and Bennu [αs = 2.9 ± 0.351] have a shallower slope. On the other hand, Didymos and Dimorphos have steeper SFD slopes, of αs = −3.6 ± 0.7 and αs = −3.4 ± 1.3, respectively48 (Fig. 7).

a Boulder SFD used in the Selam and Dimorphos SPH simulations compared to the SFD measured on the surface of asteroids (Didymos/Dimorphos48; Itokawa47; Ryugu50; Bennu51). b Boulder SFD used in the Selam and Dimorphos SPH simulations compared to power-law slopes between αs = −3.6 and −2.65. Vertical line at \({R}_{\min }=2.5\) m indicates the minimum boulder size included in the simulations.

Due to resolution constraints, we explicitly model only boulders larger than 2.5 metres in radius, with the spaces between them filled with matrix material. Consequently, components smaller than 2.5 metres are considered part of the matrix, which is represented as granular material. This approach results in a boulder-to-matrix volume ratio of approximately 25 vol%.

To model Dimorphos, we use the SFD defined by a Weibull distribution, as described in29, with a boulder-to-matrix volume ratio of approximately 30 vol%.

To resolve each colliding moonlet, we use 5 × 105 particles for our parameter studies, enabling us to explore various merging conditions and a broad parameter space. For specific impact scenarios of particular interest, we employ a higher resolution of 5 × 106 particles. This increased resolution allows for a more detailed and accurate modelling of the dynamics and outcomes of these specific collisions. The simulations were run until t = 24 h after the impact.

Material model

The material of both moonlet’s boulders and the matrix is modelled using the Tillotson equation of state (EOS) for basalt52, with a reduced bulk modulus of A = 2.5 × 105 Pa. For the impact velocities studied here (up to a few tens of cm/s), no significant heating occurs, and the bulk modulus, together with the porosity model parameters, are only defined to describe the material response to compression30.

Ground observations of asteroid Dinkinesh reveal a reflectance spectrum consistent with an Sq-type classification4,5, similar to measurements of Didymos and Dimorphos, which indicate an S-type classification6. Therefore, to model the asteroid moons, we assigned material properties that29 and22 found to be the best fit for the surface mechanical properties of Didymos/Dimorphos.

Strength

In all of our simulations, individual boulders are explicitly resolved and their mechanical response is described using the tensile damage formulation of18,19, assuming a nominal tensile strength of YT = 10 MPa.

However, the inter-particle cohesion, which governs the bulk structural behaviour of the rubble-pile moonlets, is treated as cohesionless (Y = 0 Pa). This approximation is supported by recent analyses of small-body surfaces, which suggest very low inter-granular cohesion in asteroid surfaces (e.g., ref. 22, and references therein). To model the strength of this cohesionless matrix, we adopt a simple pressure-dependent strength model20,43, in which the strength asymptotes to a certain shear strength at high pressures. For Y0 = 0 Pa, the yield strength is described as:

where P is pressure, f is the coefficient of internal friction, and Ydm is the limiting strength at high pressure.

Cohesion sensitivity analysis

To evaluate the effect of cohesion on shape formation in low-velocity mergers, a suite of simulations was conducted with matrix cohesion values ranging from 0 to 100 Pa. These simulations use a consistent 1:2 mass ratio and impact velocities between 1.5 and 2.5 vesc.

The results show that for cohesion values ≲ 1 Pa, the final shape, internal strain distribution, and shape axis ratios (a/b and b/c) of the merged body are nearly indistinguishable from the cohesionless case. Figures 8, 9 show that key morphological features, such as the equatorial ridge, are preserved across this range. Likewise, the cumulative distribution of material experiencing strain above a given threshold remains consistent (Fig. 10).

As cohesion increases, the required impact velocity is also increased to achieve merger. For cohesions lower than a few Pa, the characteristic equatorial ridge fails to form, indicating a very weak surface. Yellow shows highly strained and displaced material (total integrated strain > 1); grey indicates relatively unmodified regions.

a At 1.5 vesc, there is a negligible difference in strain between targets with 0 Pa and 1 Pa. However, as cohesion increases further, the material experiences significantly less deformation. b While increasing the impact velocity can partially compensate for this effect, it fails to reproduce the observed post-impact shape (see Figs. 1, 2).

As cohesion increases beyond a few Pa, however, the collision outcome changes substantially. The degree of deformation is reduced, the ridge structure fails to form, and the strain distribution becomes more localised (Fig. 10). While increasing the impact velocity can partially compensate for this effect (Fig. 10b, the resulting shapes diverge from those produced in the low-cohesion regime and no longer match the observed Selam A morphology.

Porosity

Based on the combined system mass and volume, the bulk density of Dinkinesh was estimated to be ρ = 2400 ± 350 kg/m32. It is assumed that Selam, its satellite, shares this bulk density. The observed bulk porosity stems from macroporosity, which occurs between individual rocks and boulders, as well as microporosity within the rocks themselves. Based on analysis of the reflectance spectra, S-type asteroids are likely the progenitors of L/LL-chondrite meteorites6,24,25, which have grain densities between approximately 3200 and 3600 kg/m3 and microporosities typically around 8–10%26.

In our simulations, we modelled both the boulders and the matrix material using the Tillotson equation of state (EoS) for basalt52, with modified initial grain densities of ρg = 3200 kg/m3. The initial microporosity within boulders was fixed at 10% and the combined macro- and microporosity of the matrix at 45%, as calculated by29. To replicate the porosity compaction behaviour, the porosity in both the boulders and the matrix was modelled using the P − α model18, with a single power-law slope, defined by the solid pressure, Ps, elastic pressure, Pe, exponent, n, and initial distension, α0:

The input parameters for the matrix and boulder materials are summarised in Supplementary Table 1.

Tidal effects

To account for tidal and rotational effects, we use the linearised equation of motion in a rotating Cartesian coordinate system53 orbiting around the primary. In order to reduce the number of free parameters to keep the simulations tractable, it is assumed that the colliding moonlets have a tidally locked rotation state, which means they have zero spin in the rotating coordinate system. In reality, however, the moonlets may not necessarily be tidally-locked, although previous work demonstrated that the moonlets may form at or near synchronous rotation, making this a reasonable assumption14. We use an x-axis pointing away from the primary, the y-axis tangential to the direction of motion, and the z-axis perpendicular to the orbital plane. This yields the following forces per unit mass, which are added as external accelerations in each time-step to the SPH particles30:

where \({\Omega }^{2}=\frac{G{M}_{{{{\rm{primary}}}}}}{{a}^{3}}\), G is the gravitational constant, Mprimary is the mass of the primary, and a is the distance to the primary.

Calculations of the strained material

To evaluate the degree of deformation experienced by different regions of the material during the collision, we tracked the total accumulated strain of each SPH particle throughout the simulation. This was achieved by integrating the second invariant of the strain-rate tensor over time, which quantifies the overall shear deformation imparted on the material. Regions exhibiting high integrated strain values (greater than 1) correspond to zones of high shearing, and are therefore expected to contain highly fragmented or fine-grained material. By contrast, particles with lower cumulative strain (less than 1) likely underwent limited deformation, preserving much of their original structure. Notably, material ejected during the collision and later reaccreted onto the merged remnant typically shows the highest cumulative strain values, often significantly exceeding 1.

v esc calculation

The mutual escape velocity of two moonlets of masses m1 and m2 is given by:

where r1 and r2 are the radii of the moonlets.

Dynamical simulations

Typical satellite collision speeds were determined by integrating their motion using the REBOUND N-body code with IAS15, a 15th-order Gauss-Radau integrator54,55. By determining collision speeds numerically, accounting for gravitational interactions between all three objects, the effect of gravitational focusing on the collision speeds can be easily quantified. The primary is a sphere with a radius of 360 m and a bulk density of 2400 kg m−3. The two satellites are assumed to be equal in size and mass and have the same bulk density as the primary. The satellite mass is randomly generated on a logarithmic scale between 10−5 and 10−1 primary masses. Then, the first satellite’s semimajor axis is randomly generated uniformly between 3 and 20 primary radii. The second satellite’s semimajor axis is then randomly selected to be within one Hill radius of the first satellite’s to ensure a reasonable probability of collision. The two satellites are assumed to be coplanar, but their initial eccentricities are randomly selected between 0.0 and 0.5. This relatively extreme upper bound on the eccentricity of 0.5 is to remain agnostic to the processes leading up the the merger, which is not fully modelled here. The orbit angles are randomised, and the system is integrated for 10 synodic periods. If the two satellites are initialised within 2 Hill spheres of each other, or if they don’t collide with each other within the simulation duration, then the simulation is rejected and the initial conditions of the second satellite are regenerated. A total of 100,000 simulations were integrated up to the moment of collision, and collision speed and distance from the primary were recorded.

Dynamical simulations under the presence of a narrow ring

Considering the ring’s effect on satellite evolution is complex, prompting us to adopt a hybrid methodology. We start with 1D hydrodynamic simulations using the HydroRings code17,56,57, which tracks ring evolution and satellite interaction using a bin-cell scheme (see58 for details). This code, however, does not compute mutual satellite interactions; instead relying on an analytical orbital integrator.

Our simulations were specifically designed to boost the impact speed between the merging bodies to values of 2 vesc, and include two satellites, each with half the mass of Selam’s lobe, placed at 2.4 Rprimary and 3.4 Rprimary in initially circular orbits. To maximise the effect of the disk torque on the impact velocity, we considered only the disk’s influence on the outer satellite, implemented as a uniform ring centred at 2.15 Rprimary, with a width of 0.04 Rprimary and represented by 100 bins. The ring’s centre corresponds to the 1:2 Lindblad resonance with the outer satellite, which is the dominant term responsible for satellite migration. The system is evolved until the satellites’ separation reaches less than one mutual Hill radius, at which point HydroRings simulations are stopped, and the semi-major axis, eccentricity, and instantaneous torque Γ from the ring on the satellites are saved.

The system then evolves to impact using the REBOUND code54,55 with IAS15. The semi-major axes and eccentricities are taken from HydroRings, while inclinations are randomly selected in the range 10−6 to e, and angular orbital elements are randomly assigned between 0 and 2π. The simulations include disk-induced acceleration on the satellites, calculated as \({\vec{a}}_{{{{\rm{disk}}}}}=\frac{\Gamma }{{M}_{s}r}\hat{T}\), where r is the orbital radius and \(\hat{T}\) is the tangential unit vector. From HydroRings, we get Γ = 0.06 N ⋅ m.

We performed simulations varying the initial ring’s surface density Σ in HydroRings. For each Σ value, we conducted 300 simulations in REBOUND with different orbital parameters. We observe that for \(\Sigma < 0.01{M}_{{{{\rm{primary}}}}}/{R}_{{{{\rm{primary}}}}}^{2}\), impact velocities approximate 1 vesc, while the best results are found for \(\Sigma=0.1{M}_{{{{\rm{primary}}}}}/{R}_{{{{\rm{primary}}}}}^{2}\), where impact velocities reach 2 vesc. An example of impact is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Data availability

Asteroid images used in this study are publicly available from NASA’s Planetary Data System (PDS) and associated mission archives. Specifically, Lucy L’LORRI Dinkinesh data are available as: Weaver, H., N. Dello Russo, O. Barnouin, H. Taylor, and J. Spencer, Lucy L’LORRI Dinkinesh Partially Processed Data Collection, urn:nasa:pds:lucy.llorri:data_dinkinesh_partially_processed::1.0, D. Kaufmann, M. K. Crombie, C. Gobat, and J. Wm. Parker (eds.), NASA Planetary Data System, 2024. DOI: 10.26007/kvc4-2t38. https://pdssbn.astro.umd.edu/holdings/pds4-lucy.llorri:data_dinkinesh_partially_processed-v1.0/DART DRACO data are available as: Ernst, C., Daly, T., Barnouin, O., Espiritu, R., Waller, C.D., Tinsman, C., DART Spacecraft Archive Bundle v3.0, urn:nasa:pds:dart::3.0, NASA Planetary Data System, 2023. DOI: 10.26007/5gcz-rb16. https://pdssbn.astro.umd.edu/holdings/pds4-dart:data_dracocal-v2.0/final/2022/269/Additional supporting information and input files for the model simulations used in this work are available in the Zenodo repository https://zenodo.org/records/17409456(https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17409456).

Code availability

A compiled version of the Bern SPH code, as well as the necessary input files, are available from the corresponding author upon request. The SPH data visualisation was produced using the National Centre for Atmospheric Research software Visualisation and Analysis Platform for Ocean, Atmosphere, and Solar Researchers (VAPOUR v.3.8.0) (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7779648). Simulations in this paper made use of the collisional N-body code REBOUND, which can be downloaded freely at https://github.com/hannorein/rebound. A compiled version of the HYDRORINGS is available upon request.

References

Walsh, K. J. & Jacobson, S. A. Formation and evolution of binary asteroids. In Asteroids IV, 375-393 (University of Arizona Press, 2015).

Levison, H. F. et al. A contact binary satellite of the asteroid (152830) Dinkinesh. Nature 629, 1015–1020 (2024).

Daly, R. T. et al. Successful kinetic impact into an asteroid for planetary defense. Nature 616, 443–447 (2023).

Bolin, B. T., Noll, K. S., Caiazzo, I., Fremling, C. & Binzel, R. P. Keck and Gemini spectral characterization of Lucy mission fly-by target (152830) Dinkinesh. Icarus 400, 115562 (2023).

León, J. D. et al. Characterisation of the new target of the NASA Lucy mission: Asteroid 152830 Dinkinesh (1999 VD57). Astron. Astrophys. 672, A174 (2023).

de León, J., Licandro, J., Duffard, R. & Serra-Ricart, M. Spectral analysis and mineralogical characterization of 11 olivine-pyroxene rich NEAs. Adv. Space Res. 37, 178–183 (2006).

Chabot, N. L. et al. Achievement of the planetary defense investigations of the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission. Planet. Sci. J. 5, 49 (2024).

Barnouin, O. S. et al. Shape of (101955) Bennu indicative of a rubble pile with internal stiffness. Nat. Geosci. 12, 247–252 (2019).

Watanabe, S. et al. Hayabusa2 arrives at the carbonaceous asteroid 162173 Ryugu–A spinning top-shaped rubble pile. Science 364, 268–272 (2019).

Lauretta, D. S. et al. The unexpected surface of asteroid (101955) Bennu. Nature 568, 55 (2019).

Tatsumi, E. et al. Global photometric properties of (162173) Ryugu. Astron. Astrophys. 639, A83 (2020).

Scheeres, D. J. Landslides and Mass shedding on spinning spheroidal asteroids. Icarus 247, 1–17 (2015).

Daly, R. T. et al. An updated shape model of Dimorphos from DART data. Planet. Sci. J. 5, 24 (2024).

Agrusa, H. F. et al. Direct N-body simulations of satellite formation around small asteroids: insights from DART’s encounter with the Didymos system. Planet. Sci. J. 5, 54 (2024).

Wimarsson, J. et al. Rapid formation of binary asteroid systems post rotational failure: a recipe for making atypically shaped satellites. Icarus 421, 116223 (2024).

Madeira, G., Charnoz, S. & Hyodo, R. Dynamical origin of Dimorphos from fast spinning Didymos. Icarus 394, 115428 (2023).

Madeira, G. & Charnoz, S. Revisiting Dimorphos formation: s pyramidal regime perspective and application to Dinkinesh’s satellite. Icarus 409, 115871 (2024).

Jutzi, M., Benz, W. & Michel, P. Numerical simulations of impacts involving porous bodies: I. Implementing sub-resolution porosity in a 3D SPH Hydrocode. Icarus 198, 242–255 (2008).

Jutzi, M. SPH calculations of asteroid disruptions: The role of pressure-dependent failure models. Planet. Space Sci. 107, 3–9 (2015).

Lundborg, N. The strength-size relation of granite. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 4, 269–272 (1967).

Perry, M. E. et al. Low surface strength of the asteroid Bennu inferred from impact ejecta deposit. Nat. Geosci. 15, 447–452 (2022).

Barnouin, O. S. et al. The geology and evolution of the near-earth binary asteroid system (65803) Didymos. Nat. Commun. 15, 6202 (2024).

Robin, C., Murdoch, N., Duchene, A. et al. Mechanical properties of rubble pile asteroids: insights from a morphological analysis of surface boulders. Nature Communications https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50147-w (2024).

Dunn, T. L., Burbine, T. H., Bottke, W. F. & Clark, J. P. Mineralogies and source regions of near-Earth asteroids. Icarus 222, 273–282 (2013).

Ieva, S. et al. Spectral rotational characterization of the Didymos system prior to the DART impact*. Planet. Sci. J. 3, 183 (2022).

Flynn, G. J., Consolmagno, G. J., Brown, P. & Macke, R. J. Physical properties of the stone meteorites: implications for the properties of their parent bodies. Geochemistry 78, 269–298 (2018).

Raducan, S. D. & Jutzi, M. Global-scale reshaping and resurfacing of asteroids by small-scale impacts, with applications to the DART and HERA missions. Planet. Sci. J. 3, 128 (2022).

Jutzi, M., Raducan, S. D., Zhang, Y., Michel, P. & Arakawa, M. Constraining surface properties of asteroid (162173) Ryugu from numerical simulations of Hayabusa2 mission impact experiment. Nat. Commun. 13, 7134 (2022).

Raducan, S. D. et al. Physical properties of asteroid Dimorphos as derived from the DART impact. Nat. Astron. 8, 445–455 (2024).

Leleu, A., Jutzi, M. & Rubin, M. The peculiar shapes of Saturn’s small inner moons as evidence of mergers of similar-sized moonlets. Nat. Astron. 2, 555–561 (2018).

Michel, P. et al. The ESA Hera mission: detailed characterization of the DART impact outcome and of the binary asteroid (65803) Didymos. Planet. Sci. J. 3, 160 (2022).

Walsh, K. J., Richardson, D. C. & Michel, P. Rotational breakup as the origin of small binary asteroids. Nature 454, 188–191 (2008).

Campo Bagatin, A. et al. Recent collisional history of (65803) Didymos. Nat. Commun. 15, 3714 (2024).

Dai, W.-Y., Yu, Y., Cheng, B., Baoyin, H. & Li, J.-F. Regolith resurfacing and shedding on spinning spheroidal asteroids: dependence on the surface mechanical properties. Astron. Astrophys. 684, A172 (2024).

Merrill, C. C., Kubas, A. R., Meyer, A. J. & Raducan, S. D. Age of (152830) Dinkinesh I Selam constrained by secular tidal-BYORP theory. Astron. Astrophys. 684, L20 (2024).

Meyer-Vernet, N. & Sicardy, B. On the physics of resonant disk-satellite interaction. Icarus 69, 157–175 (1987).

Cueva, R. H. et al. The secular dynamical evolution of the binary asteroid system (65803) Didymos post-DART. Planet. Sci. J. 5, 48 (2024).

Meyer, A. J. et al. The perturbed full two-body problem: application to post-dart Didymos. Planet. Sci. J. 4, 141 (2023).

Pravec, P. et al. Photometric survey of binary near-Earth asteroids. Icarus 181, 63–93 (2006).

Benz, W. & Asphaug, E. Impact simulations with fracture. I - Method and tests. Icarus 107, 98 (1994).

Benz, W. & Asphaug, E. Simulations of brittle solids using smooth particle hydrodynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 87, 253–265 (1995).

Nyffeler, B. Modelling of impacts in the solar system on a Beowulf cluster. (PhD thesis, University of Bern. 2004).

Collins, G. S., Melosh, H. J. & Ivanov, B. A. Modeling damage and deformation in impact simulations. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 39, 217–231 (2004).

Jutzi, M., Michel, P., Hiraoka, K., Nakamura, A. M. & Benz, W. Numerical simulations of impacts involving porous bodies: II. Comparison with laboratory experiments. Icarus 201, 802–813 (2009).

Ormö, J. et al. Boulder exhumation and segregation by impacts on rubble-pile asteroids. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 594, 117713 (2022).

Thomas, P. C., Veverka, J., Robinson, M. S. & Murchie, S. Shoemaker crater as the source of most ejecta blocks on the asteroid 433 Eros. Nature 413, 394–396 (2001).

Michikami, T. et al. Size-frequency statistics of boulders on the global surface of asteroid 25143 Itokawa. Earth Planets Space 60, 13–20 (2008).

Pajola, M. et al. Evidence for multi-fragmentation and mass shedding of boulders on rubble-pile binary asteroid (65803) didymos-dimorphos. Nat. Commun. 15, 6205 (2024).

Robbins, S. et al. The boulder population on asteroid (152830) Dinkinesh and Dinkinesh i selam based on the 2023 Lucy flyby. In 55th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. 2638 (2024).

Michikami, T. et al. Boulder size and shape distributions on asteroid Ryugu. Icarus 331, 179–191 (2019).

DellaGiustina, D. N. et al. Properties of rubble-pile asteroid (101955) Bennu from OSIRIS-REx imaging and thermal analysis. Nat. Astron. 3, 341–351 (2019).

Benz, W. & Asphaug, E. Catastrophic disruptions revisited. Icarus 142, 5–20 (1999).

Wisdom, J. & Tremaine, S. Local simulations of planetary rings. Astron. J. 95, 925 (1988).

Rein, H. & Liu, S. F. REBOUND: an open-source multi-purpose N-body code for collisional dynamics. Astron. Astrophys. 537, A128 (2012).

Rein, H. & Spiegel, D. S. IAS15: a fast, adaptive, high-order integrator for gravitational dynamics, accurate to machine precision over a billion orbits. Monthly Not. R. Astron. Soc. 446, 1424–1437 (2015).

Salmon, J., Charnoz, S., Crida, A. & Brahic, A. Long-term and large-scale viscous evolution of dense planetary rings. Icarus 209, 771–785 (2010).

Charnoz, S., Salmon, J. & Crida, A. The recent formation of Saturn’s moonlets from the viscous spreading of the main rings. Nature 465, 752–754 (2010).

Madeira, G. et al. Exploring the recycling model of phobos formation: rubble-pile satellites. Astron. J. 165, 161 (2023).

Acknowledgements

S.D.R. and M.J. acknowledge support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (project number 200021_207359). G.M. thanks Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris and European Research Council (101001282, METAL). H.A. was supported by the French government through the UCA J.E.D.I. Investments in the Future project managed by the National Research Agency (ANR) with the reference number ANR-15-IDEX-01, as well as CNES. F.F. and J.W. acknowledge funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation Ambizione grant number 193346.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D.R., G.M., H.F.A., S.C. and M.J. conceptualised the study. S.D.R. ran the impact simulations and analysed the data. G.M. and H.F.A. ran the dynamical simulations. S.D.R., G.M., H.F.A. and C.C.M. wrote the initial draft. S.D.R., G.M., H.F.A., C.C.M., R.M., F.F., J.W., S.C., P.M. and M.J. contributed to interpreting the results and to the revised manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bin Cheng, Fernando Roig, and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raducan, S.D., Madeira, G., Agrusa, H.F. et al. Multiple moonlet mergers as the origin of the Dinkinesh-Selam system. Nat Commun 16, 11033 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66484-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66484-3