Abstract

Statins are the most prescribed class of drugs and inhibit a key enzyme in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway. Many patients have reported mild to severe muscle related symptoms and a subset are at risk for rhabdomyolysis. Sequence variants in RyR1, the skeletal muscle Ryanodine Receptor, correlate with intolerance to statins, but whether RyR1 can bind statins directly has remained unclear. Here we report cryo-EM structures of RyR1 in the absence and presence of atorvastatin, firmly establishing RyR1 as an unintended off-target. Our results show an unusual binding mode whereby three atorvastatin molecules bind together in a cleft formed by the pseudo-voltage sensing domain, making extensive interactions with each other and with RyR1. Atorvastatin activates RyR1 in a sequential way, whereby one statin per subunit can bind to the transmembrane region of a closed RyR1, with small structural perturbations that prime the channel for opening. Binding of two additional statins per subunit is associated with a widening of the pseudo-voltage sensing domain that triggers opening of the pore. Comparison with atorvastatin binding to HMG-CoA reductase, its intended target, offers clues on how to modify the statin to reduce RyR1 binding, while leaving binding to HMG-CoA reductase unperturbed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Statins lower blood plasma cholesterol by inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMG-CoA-R), which converts HMG-CoA to mevalonic acid, an early step in the mevalonate pathway that produces cholesterol and isoprenoids. With >200 million users worldwide, statins have significantly reduced the risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke1,2. However, adverse effects are often reported, most of which relate to skeletal muscle function. These can range from muscle ache and fatigue to rhabdomyolysis, a life-threatening condition that can lead to renal failure3. Myotoxicity is readily observed through increased creatine kinase (CK) in the blood, and the issues are usually resolved after stopping statin treatment. Cerivastatin, approved by the FDA in 1997, was withdrawn from the market just four years later after 52 deaths as a result of severe rhabdomyolysis4. There are various risk factors associated with the muscle side effects, including other drugs that can affect the metabolism of statins by inhibiting cytochrome P450, but also increased physical activity, advanced age, physical frailty, and alcohol use5.

Severe muscle symptoms arise in 0.1%–0.5% of statin users, but a much higher number of patients report general muscle pain because of statin use. Observational studies suggest that such symptoms prevail in as high as 10–25% of the patients6,7. Whereas this latter number is heavily debated3, muscle-related effects, including the life-threatening rhabdomyolysis, are well-established and accepted as true statin side effects.

Ryanodine Receptors (RyRs) are large, ~2.2MDa ion channels that release Ca2+ from the endoplasmic (ER) and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)8. The human genome encodes three isoforms (RyR1-3), with RyR1 being predominant in skeletal muscle. RyR1 is activated through coupling with the L-type calcium channel CaV1.1, and the resulting Ca2+ release from the SR drives muscle contraction. Many mutations in RyR1 are known to cause susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia (MH), a potentially lethal condition that arises from halogenated anesthetics used during surgery9,10. MH can also arise from mutations in the CACNA1S gene, which encodes CaV1.1, or mutations in STAC3, which encodes a protein that enables coupling between CaV1.1 and RyR111,12,13. Other RyR1 mutations cause myopathies, including central core disease (CCD), a form of progressive muscle weakness14, and many patients with CCD are also susceptible to MH.

Several observations have hinted that RyR1 may be an unintended target for statins and that this underlies adverse muscle effects. Several case studies of patients with statin-induced myopathy showed that they also tested positive for MH sensitivity or are carriers of RyR1 mutations15,16,17,18. One study identified likely pathogenic variants within the RYR1 and CACNA1S genes for 16% of the investigated patients with statin-induced myopathy19. Other studies observed an increased release of Ca2+ from the SR or an altered function of RyR1 in muscle tissue from humans, rats and mice after statin treatment20,21. Mice carrying a gain-of-function RyR1 variant linked to MH were found to be more sensitive to simvastatin, with increased leak of Ca2+ from the SR22. Higher doses were also observed to create similar symptoms in wild-type muscle tissue. Muscle biopsies from pigs carrying an MH mutation showed muscle contractions in response to simvastatin or atorvastatin, while wild-type tissue did not23,24. More recently, electrophysiological recordings on RyR1 obtained from SR vesicles showed that several statins increased the open probability of RyR125,26.

Although these studies suggest RyR1 is affected by statins, ambiguity has remained on whether this is due to direct binding, by affecting an RyR1 binding partner (present in tissue and in SR vesicle preps), or by affecting signaling pathways that impinge on RyR1. In this work, we test whether atorvastatin can directly bind to and activate RyR1 using single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). Our structures reveal the unexpected binding of several atorvastatin molecules to the transmembrane region, triggering the opening of the pore. This binding occurs in a sequential manner, and a detailed investigation of the binding determinants directly provides clues on how to prevent RyR1 binding while preserving inhibition of HMG-CoA Reductase.

Results

Atorvastatin triggers opening of RyR1

We solved cryo-EM structures of rabbit RyR1 in activating conditions (Ca2+ and caffeine) and in the presence of atorvastatin (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Figs. 1–6 and Supplementary Table 1). Ca2+ alone has previously been shown to be insufficient to produce open RyR1 under cryo-EM conditions27, and we therefore included caffeine to further favor open-state RyR1. Although ATP is a known activator, we omitted this to allow for the possibility that atorvastatin binds to this site. Since atorvastatin was dissolved in DMSO, we also collected a control dataset containing the same concentrations of Ca2+, caffeine, and an equal final concentration of DMSO (2%). In the control dataset ( ~ 3.1 Å resolution), all RyR1 particles adopted a closed conformation, but in the presence of atorvastatin, ~64% displayed an open conformation (Supplementary Figs. 1, 3). We thus solved both open- and closed-state structures of RyR1 in the presence of atorvastatin, at ~3.4 Å and 3.6 Å, respectively. As the only difference with the control datasets is the presence of atorvastatin, this indicates that atorvastatin can directly cause activation and opening of RyR1. In a muscle context, this would lead to a leak of Ca2+ that may directly underlie statin-induced myopathy.

A chemical structure of atorvastatin, indicating the various constituent moieties. B Density for the three atorvastatin molecules per RyR1 protomer, contoured at 5.5σ. The three molecules are shown in stick representation (red: oxygen; blue: nitrogen; light green: fluorine; yellow/green/magenta: carbon for ator1,ator2 and ator3, respectively). C Side-view (top panel) of the open RyR1 bound to atorvastatin, with one of the protomers highlighted in orange. The inset shows a top view (facing the SR lumen) of the transmembrane region. Transmembrane helices (S1–S6) are labeled, and the statins are shown in colored sticks (yellow, green, magenta). D Density for the 3 atorvastatin molecules in relation to neighboring protein density. The density map is shown at a cut-off of 5.5σ. E–G. details of the chemical environments of the three statin molecules in the open-state RyR1. Blue dashed lines represent polar contacts, including H-bonds (3.5 Å distance cut-off) and salt bridges (4 Å cut-off). Black dashed lines represent additional van der Waals interactions (4 Å distance cut-off).

Multiple atorvastatin molecules bind to the pVSD

Inspection of the open RyR1 in the presence of atorvastatin showed unambiguous density for twelve atorvastatin molecules in the transmembrane region, corresponding to 3 molecules per protomer (Fig. 1B–D). The transmembrane region of RyRs follows a topology very similar to tetrameric voltage-gated channels, with 6 well-defined transmembrane helices per subunit (Fig. 1C). Helices S1–S4 are similar to the voltage-sensing domain of voltage-gated cation channels and together form a pVSD (pseudo-voltage-sensing domain) as they lack bona fide voltage sensing. Helices S5 and S6 contribute to the pore. A small helix that is parallel to the membrane, known as the S4–S5 linker helix, connects each pVSD to the pore domain. The pVSD and pore-forming helices adopt a domain-swapped topology, whereby the pVSD of one subunit contacts the pore-forming region of a neighboring subunit.

Surprisingly, the three atorvastatin molecules (Ator1-3) make extensive interactions with both RyR1 and with neighboring atorvastatin molecules. Together, they engage helices S1, S3, and S4 of the pVSD, the S4–S5 linker, the Thumb-and-Forefinger (TaF) domain and helix S5’ of the pore-forming region of a neighboring subunit (Fig. 1D–G).

Atorvastatin consists of multiple moieties, with a central pyrrole connecting four different substituents: a hydrophilic dihydroxy heptanoic acid group, and 4 predominantly hydrophobic moieties: a small propyl, a fluorophenyl, a phenyl, and a phenyl-carbamoyl group (Fig. 1A). For all three atorvastatin molecules, the bulk of the interactions are driven by the hydrophobic constituents, which bind to exposed hydrophobic surface of RyR1. Ator1 engages the S4 and S5’ helices with a single H-bond with the dihydroxy heptanoic acid group. Ator2 is located between the S1 and S4 helices, and its dihydroxy heptanoic acid group forms an ionic interaction with Arg4824 in the S4–S5 linker. Ator3 engages the S1, S3 and S4 helices, and its dihydroxy heptanoic acid group also forms an ionic interaction with the same Arg residue in the S4–S5 linker. It also makes interactions with the thumb-and-forefinger (TaF) domain, including a likely H-bond with Gln4216. Full details of the interactions are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7.

In addition to these drug-protein interactions, there is an appreciable interface between the three atorvastatin molecules, which is entirely driven by the hydrophobic moieties. The interactions mostly involve aromatic-aromatic interactions whereby one aromatic moiety is stacked perpendicular to another, allowing favorable interactions between partial positively charged hydrogens on one aromatic moiety with pi electrons in the other. In particular, the fluorophenyl group of Ator1 interacts with the pyrrole of Ator2, whereas the fluorophenyl group of Ator2 stacks against the phenyl group of Ator3.

Thus, the binding of atorvastatin to RyR1 is highly unusual, involving both drug-protein and drug-drug interactions.

Closed-state binding

We also observed clear density for one atorvastatin per protomer (four in a full RyR1) in the closed state structure (Fig. 2A). This molecule, AtorC (for ‘closed’), occupies a similar site to Ator1 in the open state (Fig. 2B). Just like Ator1, AtorC makes several interactions with the S4–S5 linker and the S4 and S5’ helices, but because these helices have different relative locations in the open and closed states, AtorC is tilted relative to Ator1 to avoid clashes with the S4–S5 linker and S4 helix in the closed state (Fig. 2C).

A experimental density for atorvastatin bound to closed RyR1, contoured at 5.5σ. The AtorC molecule is shown in sticks (carbon: yellow; nitrogen: blue; oxygen: red; fluor: green). B location of atorvastatin (yellow sticks) relative to closed RyR1 (cyan cartoon). C Superposition of open (orange) and closed (cyan) RyR1 bound to atorvastatin, zoomed in on Ator1/AtorC (sticks). The superposition is based on the S4–S5 linker and S5’ helix of a neighboring subunit. AtorC tilts relative to Ator1 to avoid clashes with the S4–S5 linker in the closed state. D Superposition of the closed control RyR1 (gray) and the closed Atorvastatin complex (cyan). The binding of Atorvastatin to the closed state results in small structural changes, with movements ~1.5 Å in the S4–S5 linker and the S5’ helix to accommodate the molecule. E Overall superposition of the closed atorvastatin complex (cyan) and the closed control structure (gray), showing downwards movements of the cytosolic cap towards the SR membrane upon binding atorvastatin. AtorC is shown in yellow spheres.

Comparing the closed atorvastatin-bound structure to the closed control structure, there are small rearrangements in the transmembrane region. Using the S1–S3 helices as a reference point, the binding of atorvastatin coincides with a ~ 1.5 Å movement of the S4–S5 linker helix and the S5’ helix (Fig. 2D). This translates into movements far away from the binding site. Based on a global superposition of the structures, there are 2–3 Å downward shifts of the bridging solenoid (BSol) region towards the SR membrane (Fig. 2E). Similar, but larger, movements are observed upon channel opening27, suggesting that the binding of a single atorvastatin (per protomer) to RyR1 in a closed conformation may prime the channel for opening.

Mechanism of opening

Fig. 3A shows a direct comparison of the pore dimensions in the open and closed atorvastatin complex structures, as well as for the control structure, which displays a closed conformation. A direct superposition of the open and closed states readily explains the mechanism by which atorvastatin opens the channel. Superposing the structures based on the S1–S3 helices of a single protomer, neither of the Ator1–3 molecules can fit in the closed-state structure. The clashes are the least pronounced for Ator1, which, as explained above, can still bind to the closed-state structure with some structural shifts. However, both Ator2 and Ator3 make major clashes with several residues in the S4 helix and the S4–S5 linker, and the binding cleft is simply too narrow to accommodate these (Fig. 3B, C). These clashes involve both side chain and main chain atoms and can therefore not be resolved by altered side chain conformations. As a result, it is as if these two atorvastatin molecules push the S4 helix and S4–S5 linker away from the rest of the pVSD (Fig. 3D), which leads to movements of the S5 and S6 helices, resulting in a widening of the pore (Fig. 3E).

A H.O.L.E. plot for the three structures. The corresponding pore radii are shown on the right, with the positions of I4937, Q4933, and G4894 indicated. B, C Surface representation of the closed RyR1+atorvastatin structure, showing the atorvastatins from the open RyR1+atorvastatin structure in sticks (red: oxygen; blue: nitrogen; light green: fluor; yellow/green/magenta: carbon for ator1,ator2 and ator3, respectively). The superposition is based on helices S1–S3. Shown are two different views that highlight major steric clashes, especially for Ator2 (green) and Ator3 (magenta). The latter forms a major clash with the side chain of M4818, but even if the side chain were to swing away, there still are clashes with main chain atoms. Thus, binding of these two molecules is not possible in the closed state. Select RyR1 residues are labeled for reference. D local conformational changes between the closed RyR1+atorvastatin (cyan) and the open RyR1+atorvastatin (orange), with the three atorvastatin molecules shown in sticks (colored as in panels (B, C)). This superposition is based on the S1–S3 helices of the pVSD, showing the relative movements of S4, the S4–S5 linker, and the S5’ helix of a neighboring subunit to accommodate the additional statins. E Superposition of the transmembrane regions of the closed and open state RyR1+atorvastatin.

In addition to conformational changes within the TM region, there is also a movement of a helix in the thumb-and-forefinger (TaF) domain. This helix moves downward towards Ator3 in the open state, with a possible hydrogen bond between Ator3 and Gln4216 in the ‘thumb’ helix of the TaF domain (Fig. 1G). This domain makes extensive interactions with the C-terminal domain (CTD), as well as the extension of the S6 helix, whose precise conformation dictates the state of the pore. Movement of the TaF domain can thus also influence pore opening. Altogether, the atorvastatin molecules may be using multiple allosteric mechanisms to open the channel pore, one involving movement of the S4–S5 linker, and another through TaF and CTD interactions.

In voltage-gated cation channels, movements within the VSDs are also known to cause shifts in the S4–S5 linker helix, triggering pore opening. Although the precise details differ, the mechanism through which atorvastatin causes channel opening is thus reminiscent of voltage sensing. In a previous study, we also analyzed the binding of diamide insecticides to RyR1 and insect RyRs and found them to occupy a site within the pVSD28,29, close to the position of Ator3 (Fig. 4A). Chlorantraniliprole, a common diamide insecticide, also pushes S4 away from the other pVSD helices, although to a smaller extent. This highlights the pVSD as an important allosteric site that can mediate channel opening when bound to particular ligands. Thus far, a physiologically relevant signaling molecule capable of binding the pVSD remains to be identified.

A Comparison of the pVSD region bound to chlorantraniliprole (CHL) and the third atorvastatin molecule (Ator3). The left diagram shows the structure of CHL for reference. The small molecules are shown in VDW sphere representation. Colors for CHL: blue, nitrogen; red, oxygen; purple, carbon; green, chlorine. Colors for Ator3: blue, nitrogen; red, oxygen; magenta, carbon; light green, fluorine. The right panel shows a direct superposition based on helices S1–3. This indicates that the S4 and S4–S5 linker helices move further away for Ator3 compared to CHL. B Structure of open RyR1 + atorvastatin with RyR1 residues that differ between RyR1 and RyR2 shown in red. RyR1 is shown in cartoon representation, and the Ator1–3 are shown as sticks. C Sequence alignment of the regions involved in atorvastatin binding. Residues in the binding interface that are conserved among the three isoforms are shaded in gray. Residues that are not conserved are shaded in red.

Isoform specificity

The three different human RyR isoforms share 66–70% sequence identity. If atorvastatin would bind and activate RyR2, the main isoform expressed in cardiac tissue, this could lead to dangerous arrhythmias similar to catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), frequently linked to gain-of-function mutations in RyR29,30. However, cardiac side-effects of statins are not usually reported, suggesting that RyR2 is likely not a target. A direct comparison of RyR1 and RyR2 shows that there are several differences in the atorvastatin binding sites (Fig. 4B, C). Ator2 makes substantial π-stacking interactions with Phe4564, but this is replaced by a Met in RyR2. RyR1 residue Val4820 is replaced by a Phe in RyR2, which would cause a large clash with Ator1 and AtorC in the open and closed-state structures. Thus, RyR2 would not be expected to bind atorvastatin in this region or would only do so with much lower affinity. Except for Phe4564, the same substitutions also occur in RyR3, suggesting that RyR3 is likely also less sensitive to atorvastatin.

ATP binding site

All RyRs are activated by ATP, which binds at the interface between the S6-extension helix, the CTD, and the TaF domain27 (Fig. 5). The same region can also bind smaller ATP fragments and cAMP31. In our study, we did not include ATP, allowing us to test whether atorvastatin could also occupy this binding site. In the open-state structure in the presence of atorvastatin, we observed weak density within the pocket. This density is absent in the closed-state structure and in the DMSO control structure and does not resemble the density for ATP as observed in many available RyR1:ATP structures31. The density may thus correspond to an additional atorvastatin molecule. Supplementary Fig. 8 shows a possible binding pose, but since lower thresholds are needed to cover the molecule, this pose is not unambiguous and suggests partial occupancy and/or conformational heterogeneity. Regardless, there are substantial structural changes around this pocket that are not observed when the site is unoccupied or when ATP is bound27. Using the CTD as a reference, one helix of the ‘thumb’ of the TaF domain moves away towards the transmembrane region, enlarging the pocket (Fig. 5D, E). It is unclear whether these conformational changes are due to atorvastatin binding to this site or the three molecules engaging the pVSD domain. Since the ATP binding site is conserved among all three RyR isoforms27,32,33, it would follow that atorvastatin may also bind to RyR2 and RyR3 at the same site, but this remains to be confirmed.

A Cartoon model of the ATP-binding region and the neighboring transmembrane region of RyR1. Shown is one protomer (colors) and the pore-forming region of a neighboring protomer (gray). B Cryo-EM density map for the open RyR1+atorvastatin structure, contoured at 5.5σ. C corresponding density map for an open RyR1 structure with ATP (purple) bound to the pocket. D Superposition of the ATP binding regions of closed and open RyR1, both in complex with atorvastatin. One helix of the TaF (thumb and forefinger) domain moves towards the transmembrane region, and the extension of the S6 helix moves laterally away. E Corresponding superposition of the same region for an open RyR1 in complex with ATP and open RyR1 in complex with atorvastatin. A helix in the ‘thumb’ and the S6 extension helix also move away relative to the ATP complex, indicating that the size of the ATP binding pocket is larger in the presence of atorvastatin.

Comparison with HMG CoA-reductase and other statins

Fig. 6 compares the binding mode of atorvastatin to HMG-CoA-R34 and RyR1. The dihydroxy heptanoic acid group of atorvastatin is bound deep within the active site of the enzyme, explaining why this moiety is strictly required to retain inhibition34. Although the hydrophobic portions of atorvastatin make interactions as well, a large proportion of these are exposed to solvent. In contrast, Ator1–3 mostly engage RyR1 using their hydrophobic portion. Although the dihydroxy heptanoic acid groups also contribute to interactions with RyR1, the total amount of surface buried is much higher for the hydrophobic portions of the molecules. Thus, altering the hydrophobic constituents may be able to reduce or prevent association with RyR1, while retaining inhibition of HMG-CoA-R.

A Chemical structure of atorvastatin showing the hydrophilic dihydroxy heptanoic acid group in blue, and the hydrophobic portion in magenta. The acid group is present in all statins that are in clinical use. B Surface representation of tetrameric HMG-CoA reductase and RyR1, with atorvastatin molecules shown in sticks. In all cases, the hydrophilic dihydroxy heptanoic acid group is shown in blue. This group is deeply buried within the active site cleft of HMG-CoA reductase. Conversely, most of the interactions between atorvastatin and RyR1 are mediated by the hydrophobic groups.

Could other statins engage RyR1 in a similar way? Experiments with SR vesicles have shown that at least six different statins can increase their open probability, albeit with differing potencies26. Among these, cerivastatin, atorvastatin, fluvastatin and rosuvastatin all contain a fluorophenyl moiety, which makes extensive hydrophobic interactions with RyR1 for all three atorvastatin molecules bound to the pVSD. However, the hydrophobic portion of simvastatin and pravastatin differs substantially, and it is thus unclear whether these can engage RyR1 in a similar fashion.

Gain-of-function disease mutations in RyR1

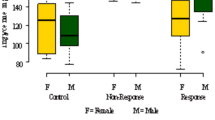

Mutations in RyR1 have been linked to MH, CCD, and other myopathies9. MH patients, as well as a subset of patients with RyR1-related myopathies, carry gain-of-function mutations, whereby RyR1 has increased sensitivity to triggering ligands like caffeine and volatile anesthetics9,35. Several reports have revealed RyR1 gain-of-function mutations in patients with statin-induced myopathy5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. This includes R614C, the first RyR1 variant to be associated with MH18,36. The equivalent mutation causes porcine stress syndrome in pigs homozygous for R615C RyR110 and is located in the cytosolic cap of RyR1 (Fig. 7A). A previous report observed that atorvastatin and simvastatin can induce contractures in muscle tissue from pigs carrying the R615C RyR1 variant, but not wild-type pigs24. The paralogous human R614C RyR1 mutation was also identified in a patient with severe statin-induced myopathy37. We therefore purified R615C pig RyR1 (pRyR1) directly from homozygous pig tissue, as we described before38. This allowed us to test whether atorvastatin has different structural effects on this mutant compared to wild-type (rabbit) RyR1. We collected a small cryo-EM dataset on this mutant in the presence of activating Ca2+, caffeine, and atorvastatin, which yielded both open ( ~ 3.4 Å) and closed ( ~ 4.1 Å) structures like wild-type RyR1 under the same experimental conditions (Fig. 7, Supplementary Figs. 9, 10 and Table 1). However, only 19% of the particles correspond to closed channels, nearly half compared to wild-type rabbit RyR1 in the same conditions (Fig. 7B). The R615C mutation affects an interface between the NSol and BSol regions38. During channel gating, there is a relative reorientation of the two domains, which can be described as a tilt with R615 located at the hinge point. As Arg615 is involved in multiple interactions with BSol residues, one likely explanation for the gain-of-function of R615C is that it destabilizes the closed state relative to the open state of the channel, resulting in a gain-of-function phenotype, manifesting as an enhanced sensitivity to activating ligands, including atorvastatin.

A Location of the R615C variant (red spheres) in the cytosolic shell of RyR1 (PDB: 9PWO) between the N-terminal domain (light blue) and the Bridging Solenoid Domain (light green). B Comparison of the particle distribution (open versus closed) for wild-type rabbit RyR1 without and with atorvastatin, and for R615C pig RyR1 with atorvastatin. C Two different views of the density map for open R615C pig RyR1 bound to atorvastatin, showing clear density for three atorvastatin molecules (Ator1–3; yellow, green, magenta) at locations identical to the ones observed for wild-type open rabbit RyR1. The map is contoured at 5.5σ. D Similar views of the corresponding closed R615C pig RyR1 bound to atorvastatin. As fewer particles are in this class, the resolution is lower, but there is still density visible for a single Atorvastatin (AtorC, yellow).

An inspection of the maps also shows clear atorvastatin binding to both the open and closed R615C pig RyR1, with 3 molecules per protomer for the open structure, and one molecule per protomer for the closed state (Fig. 7C, D). Thus, atorvastatin seems to engage R615C pig RyR1 in a manner similar to wild-type rabbit RyR1, but is able to produce a larger proportion of open state particles. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that this is due, in part, to species differences in sequence, this observation is in line with the increased contractility of muscle from pigs carrying this mutation24.

Discussion

Muscle-related symptoms are among the most common side effects of statin use. In extreme cases, it can cause rhabdomyolysis, often an issue in genetically predisposed individuals. Here we show that atorvastatin can directly engage RyR1 and trigger opening. We find that atorvastatin can bind to both closed and open RyR1 and shifts the distribution of conformations towards mostly open channels. Fig. 8 shows the sequence of events. A single atorvastatin molecule can bind per protomer of closed RyR1, at a location between the pVSD and the pore-forming domain. This causes small local changes in the binding site and movements in the cytosolic cap of the protein that are generally associated with priming of the channel27. In the open state, two additional atorvastatin molecules bind to the pVSD, whereby the statins make interactions with both RyR1 and neighboring atorvastatin molecules. In the presence of these additional molecules, the S4 transmembrane helix is shifted relative to the other pVSD helices (S1–S3), causing movement of the S4–S5 linker helix and triggering opening of the pore. In addition to these sites, a putative extra atorvastatin may bind to the ATP-binding site, as additional density is observed in this site, albeit only for the open state. The density in this site is of lower quality, which may indicate partial occupancy. In a physiological context, where ATP levels are at mM concentrations, this site is likely to be occupied by ATP instead, but this remains to be confirmed.

Binding of one atorvastatin (yellow) per protomer is observed with a small increase in the cleft between the pVSD (containing helices S1–S4) and the pore-forming region of a neighboring subunit (S5’–S6’). This is accomplished by a small shift of S5’ and the S4–S5 linker helix. This binding primes the channel for binding of two additional atorvastatins (green and magenta), whereby the S4 helix shifts relative to the S1–S3 helices, along with an additional large shift in the S4–S5 linker helix, and a widening of the pore by movement of the S6 helices.

It is currently unknown what concentration atorvastatin can reach in muscle cells, but concentrations in blood plasma have been found to be as high as ~334 nM for very high clinical doses (80 mg/day)39. To ensure saturation of the binding sites and to allow high-resolution density for atorvastatin, we used saturating concentrations well beyond this. However, based on previous ryanodine binding assays, the EC50 value of statins for RyR1 has been found to be in the range of 300 to 400 nM26, suggesting direct clinical relevance. With multiple atorvastatin molecules bound, there could be inherent affinity differences. Although this remains to be confirmed, one possibility is that Ator1, adjacent to the pore-forming domain, binds with the highest affinity, as it requires only minimal conformational changes in RyR1 to allow its binding. It is also the only atorvastatin molecule found to bind to closed RyR1. Meanwhile, the putative atorvastatin bound to the ATP site likely binds with the weakest affinity, as suggested by the much weaker density.

Interestingly, the cardiac RyR2 may not be activated strongly by statins despite its great similarity to RyR1. In fact, simvastatin was previously found to have a mild inhibitory effect on RyR2 at low concentrations25. Inspecting the binding sites, we note that there are three sequence differences that would mostly affect the binding of Ator2. As the binding of the statins also proceeds with direct statin-statin interactions, this may, in turn, affect the binding strength of Ator3. How exactly simvastatin can inhibit RyR2 remains to be found.

Overall, our study shows that multiple molecules of atorvastatin (Ator2 and Ator3) can only engage RyR1 in the open state, thus shifting the equilibrium from closed to open channels. It highlights the pVSD and adjacent area as a key region that is allosterically coupled to the gating of the pore, in a manner reminiscent of VSDs in voltage-gated cation channels. Interestingly, we previously found that diamide insecticides such as chlorantraniliprole also engage the pVSD, similar to the Ator3 molecule28,29. However, the details of the interactions differ appreciably, as chlorantraniliprole binds deeper into the pVSD and its structure is very different from atorvastatin. Although diamides have a much higher affinity for insect RyRs and are considered relatively safe for humans, RyR1 carrying gain-of-function disease mutations were found to be more sensitive to diamides40. Thus, patients with such sequence variants may generally be at increased risk for any molecule that engages the pVSD.

Various statins have been found to activate RyR1, but our study provides direct clues on how to modify atorvastatin. All statins contain a dihydroxy heptanoic acid group that is critical for inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, but which makes minimal contact with RyR1. This is confirmed in a crystal structure of HMG-CoA reductase in complex with atorvastatin, which shows that this group is deeply embedded into the active site34. The aromatic moieties also make interactions with the enzyme but effectively point away from the active site (Fig. 6). As these moieties mediate most of the interactions with RyR1, adding extra substituents onto these aromatic rings could abolish RyR1 binding through steric hindrance, while retaining binding to HMG-CoA reductase. Such analogs have the potential to abolish severe muscle-related side effects.

Methods

Expression and purification of GST-FKBP12.6

GST-tagged FKBP12.6 was expressed and purified from recombinant expression in E.coli41. In brief, a construct containing a His6-tag, GST, a cleavage site for tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease, and FKBP12.6 was expressed in NEBExpress E. coli (New England Biolabs). Cells were grown in 2xYT medium at 37 °C until an OD600 ~ 0.8 was reached, cells were cooled to 18 °C for an hour prior to induction with 0.4 mM IPTG and allowed to express for 16 h. Cell pellets, obtained by 8000 x g centrifugation, were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −20 °C. For purification, a cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 50 ug/ml DNase1, 50 ug/m lysozyme, 0.5 mM Benzamidine, 0.5 mM PMSF, and EDTA Free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), sonicated and debris removed by a 45-min centrifugation at 50,000 x g. After filtration through a 0.22-µm PES low-protein binding filter, imidazole was added to reach a concentration of 20 mM. The lysate was applied to a HisTrap column (Cytiva), washed with 10 column volumes (CV) of wash buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 50 mM Imidazole) and eluted with 5 CV of elution buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM Imidazole). The elution fractions were combined before overnight dialysis against 50 mM Tris pH 9, 500 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM Benzamidine, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM DTT. The dialyzed protein was concentrated in an Amicon ultra centrifugal concentrator to ~5 mg/ml and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage at −20 °C.

Skeletal muscle membrane preparation

Wild-type RyR1 was purified from rabbit skeletal muscle (purchased from Pel-Freeze Biologicals), and R615C RyR1 was purified from muscle from pigs homozygous for this mutant (purchased from Boyle Farms, Moorehead, Iowa) as described before38. Skeletal muscle (300 g) was chopped into ~1-cm3 pieces and kept at −20 °C for an hour prior to use. 100 g of chopped skeletal muscle was blended with ~400 ml of homogenization buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 0.5 mM PMSF) for 90 s and spun down for 7 min at 2000 x g. The supernatant was added to a second batch of 100 g chopped tissue and brought back up to a total 500 ml volume, repeating the blend and spin. This process was then repeated for the third batch of 100 g of tissue. The final supernatant was centrifuged at 200,000 x g for 30 min. The resulting membrane pellet was washed with homogenization buffer prior to flash freezing in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

Purification of RyR1

We purified RyR1 directly from the membrane pellets28,38,41. Rabbit or pig skeletal muscle membrane pellets were resuspended in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM Benzamidine, 0.5 mM PMSF, complete EDTA protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) at a ratio of 10% weight/volume membrane pellet to buffer, followed by homogenization with a dounce homogenizer. A 10x stock of detergent with solubilized lipids was added for a final concentration of 1.5% CHAPS and 0.6% soybean phosphatidylcholine (PC), and the mixture was stirred for 1 h to solubilize the membrane. Insoluble debris was removed by a 1 h centrifugation at 200,000 x g. The supernatant was diluted to achieve a final binding buffer of 0.5% CHAPS and 0.2% PC in 25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 0.5 M NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM Benzamidine, 0.5 mM PMSF. The solution was filtered through Whatman paper prior to the addition of the bait protein GST-FKBP12.6 at 5 mg of protein per 5 g of membrane pellet utilized. The mixture was stirred for 1 h, after which 2 ml of Glutathione Sepharose resin (GS4B, Cytiva) was added and incubated while stirring overnight. The GS4B resin was then applied to an empty gravity column and washed three times with 2 CV of binding buffer prior to elution with binding buffer supplemented with 40 mM reduced L-glutathione. The GS4B elution was concentrated in a 100 kDa MWCO, and TEV protease was added for 2 h to remove His6-GST from FKBP12.6. The sample was then applied to a Superose 6 column (Cytiva) to separate RyR1-FKBP12.6 from TEV protease, His6-GST and excess FKBP12.6. The running buffer consisted of 0.375% CHAPS, 0.001% DOPC, 25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, 0.5 mM Benzamidine, 0.5 mM PMSF. The peak fractions containing RyR1 were concentrated to 12–13 mg/ml for RyR1 and directly plunged or flash frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at −80 °C until plunging.

Cryo-EM sample preparation and acquisition

Purified rabbit or pig RyR1 was diluted with buffer to reach a final concentration of 9-10 mg/ml RyR1, ~36 µM free Ca2+ (buffered with 2 mM EGTA), 2 mM caffeine, 10 mM total atorvastatin and 2% DMSO. The caffeine was added to ensure a sufficiently high number of open-state particles, allowing for the possibility that atorvastatin may selectively bind to the open state. We note that atorvastatin has poor solubility despite the presence of DMSO and is presented as fibers on the cryo-EM grids. As such, the concentration in solution is likely substantially lower. A control sample was prepared to contain the same composition (including 2% DMSO) but without atorvastatin. 2 µL of sample was pipetted onto a copper holey carbon grid (Quantifoil, R2/2, 300 M) and blotted for 3–3.5 s at a force of +7–10 before flash-freezing in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI).

Grids were screened on a Glacios electron microscope prior to collection on a Titan Krios electron microscope equipped with a Falcon 4i detector operating at 300 kV. EER files were collected at a nominal magnification of 130,000x in electron-counting mode at 0.96 Å/pixel. Defocus ranged from −0.5 to −2 µm with a total dose of 50 e−/Å2. Three grids were collected during an over weekend collection with a total of 35,751 movies for the Atorvastatin dataset, a single grid with 4140 movies for the DMSO control dataset and a single grid with 5007 movies was collected for the R615C pig RyR1 dataset.

Cryo-EM data processing

All data for both wild-type rabbit RyR1 and R615C pig RyR1 were processed using Cryosparc 4.4.1. The movies were corrected using patch motion correction and patch CTF fitting. Particles were picked via blob picking using a circular radius of 250–450 Å42. Particles picked from 50 images were inspected at high and low defocus values to adjust the power for those particles with the highest and lowest contrast. Manual inspection was performed on these images to remove non-RyR particles and to pick missed particles. This set was then used to train Topaz (version 0.2.3) using a conv127 architecture with 16x downsampling for the 512 × 512 particle size. Multiple training jobs were performed, varying the expected particle per image at ± 5–10% the manually picked particle count43. The trained topaz model with the best picks on the manually curated dataset was then applied to the full dataset with outlier images removed. The total number of images used for picking were: wild-type rabbit RyR1 with atorvastatin (33,758 out of 35,751); wild-type rabbit RyR1 without atorvastatin (3774 out of 4140); R615C pig RyR1 with atorvastatin (4840 out of 5007). Particles were extracted and downsampled 2x for initial processing. 2D classification was performed to remove non-RyR like particles prior to multiple rounds of ab-initio and 3D heterogenous refinement in C1 symmetry to identify tetrameric RyR1 particles. Heterogenous classes were re-extracted at full box size and further refined via C4 non-uniform refinement. Particles were symmetry expanded and locally refined for the transmembrane/C-terminal domain, the β-solenoid domain, and N-terminal domains in C1 and the non-symmetry expanded particles were used with a transmembrane domain mask in C4. Maps generated from the local refinements were multiplied by their masks, and Chimera44 was used to create a composite map. The composite map and global map were subject to density modification using the program EMReady (version 1.1)45 to aid in visual interpretation. All maps depicted in the figures are raw cryo-EM maps unless for Supplementary Fig. 6 where it was density modified.

Model building

To build models for the WT rabbit RyR1, we started by docking PDB: 7TZC in the map, breaking the model up into local refined regions and rigid body fitting them. The models were refined using a combination of manual adjustments in COOT (version 0.9.8.7)46, automated real-space refinement in PHENIX (version 1.21)47 and semi-automated refinement using ISOLDE (version 1.7.1) in ChimeraX (version 1.7)48,49,50. To model regions of RyR1 with poor density, x-ray crystal structures of the Ry12 and Ry34 domains were utilized with alternative conformations removed and Cys/Ala mutations reverted to the highest probability rotamers51,52. Ligand parameters were generated with Phenix.elbow in Phenix and fit into the density using COOT and Rosetta Emerald53. Ligand contact analysis was performed with LigPlot+ (version 2.2.9)54. To build the R615C pig RyR1 open structure in complex with atorvastatin, we used the open rabbit RyR1:atorvastatin complex, modified by the program MODELER55 to update pig-specific side chains, followed by rigid body refinement and several rounds of PHENIX real space refinement and ISOLDE.

Pore radius calculations

Pore radii were calculated using the program H.O.L.E. (version 2.2.005)56. To generate the plot, we used part of the final RyR1 models containing the pore domain (S5, S6, and pore helix), along with the CTD and TaF domain. The radius plots were generated in Microsoft Excel.

Ethical statement

Animal muscle tissue was used, obtained commercially from vendors (Pel-Freez and Boyle Farms). Per institutional guidelines, no animal ethics is required for commercial tissue, but all experiments were performed according to the Biosafety guidelines of the University of British Columbia.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession codes 9OL5 (Closed RyR1+atorvastatin); 9OL4 (Open RyR1+atorvastatin); 9OL6 (closed RyR1 DMSO control); 9PWO (Closed R615C pig RyR1 + atorvastatin). The cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession codes EMD-70590 (Closed RyR1+atorvastatin); EMD-70589 (Open RyR1+atorvastatin); EMD-70591 (closed RyR1 DMSO control); EMD-71924 (Closed R615C pig RyR1 + atorvastatin); EMD-70600 (Open R615C pig RyR1+atorvastatin). The following PDB was used to guide model building: 7TZC The following PDB and corresponding cryo-EM map were used for ATP binding site comparison: 6M2W and EMD-30067.

References

Pinal-Fernandez, I., Casal-Dominguez, M. & Mammen, A. L. Statins: pros and cons. Med Clin. (Barc.) 150, 398–402 (2018).

Yang, C., Wu, Y. J., Qian, J. & Li, J. J. Landscape of statin as a cornerstone in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Rev. Cardiovasc Med 24, 373 (2023).

Adhyaru, B. B. & Jacobson, T. A. Safety and efficacy of statin therapy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15, 757–769 (2018).

Furberg, C. D. & Pitt, B. Withdrawal of cerivastatin from the world market. Curr. Control. Trials Cardiovasc. Med 2, 205–207 (2001).

Abd, T. T. & Jacobson, T. A. Statin-induced myopathy: a review and update. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 10, 373–387 (2011).

Bruckert, E., Hayem, G., Dejager, S., Yau, C. & Begaud, B. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients—the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 19, 403–414 (2005).

Cohen, J. D., Brinton, E. A., Ito, M. K. & Jacobson, T. A. Understanding Statin Use in America and Gaps in Patient Education (USAGE): an internet-based survey of 10,138 current and former statin users. J. Clin. Lipido. 6, 208–215 (2012).

Woll, K. A. & Van Petegem, F. Calcium-release channels: structure and function of IP(3) receptors and ryanodine receptors. Physiol. Rev. 102, 209–268 (2022).

Pancaroglu, R. & Van Petegem, F. Calcium channelopathies: structural insights into disorders of the muscle excitation-contraction complex. Annu Rev. Genet. 52, 373–396 (2018).

Fujii, J. et al. Identification of a mutation in porcine ryanodine receptor associated with malignant hyperthermia. Science 253, 448–451 (1991).

Horstick, E. J. et al. Stac3 is a component of the excitation-contraction coupling machinery and is mutated in Native American myopathy. Nat. Commun. 4, 1952 (2013).

Rufenach, B. et al. Multiple sequence variants in STAC3 affect interactions with CaV1.1 and excitation-contraction coupling. Structure 28, 922–932.e5 (2020).

Rufenach, B. & Van Petegem, F. Structure and function of STAC proteins: calcium channel modulators and critical components of muscle excitation-contraction coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 297, 100874 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. A mutation in the human ryanodine receptor gene associated with central core disease. Nat. Genet. 5, 46–50 (1993).

Guis, S. et al. Rhabdomyolysis and myalgia associated with anticholesterolemic treatment as potential signs of malignant hyperthermia susceptibility. Arthritis Rheum. 49, 237–238 (2003).

Krivosic-Horber, R., Depret, T., Wagner, J. M. & Maurage, C. A. Malignant hyperthermia susceptibility revealed by increased serum creatine kinase concentrations during statin treatment. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 21, 572–574 (2004).

Guis, S. et al. In vivo and in vitro characterization of skeletal muscle metabolism in patients with statin-induced adverse effects. Arthritis Rheum. 55, 551–557 (2006).

Vladutiu, G. D. et al. Genetic risk for malignant hyperthermia in non-anesthesia-induced myopathies. Mol. Genet Metab. 104, 167–173 (2011).

Isackson, P. J. et al. RYR1 and CACNA1S genetic variants identified with statin-associated muscle symptoms. Pharmacogenomics 19, 1235–1249 (2018).

Lotteau, S. et al. A mechanism for statin-induced susceptibility to myopathy. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 4, 509–523 (2019).

Inoue, R. et al. Ca2+-releasing effect of cerivastatin on the sarcoplasmic reticulum of mouse and rat skeletal muscle fibers. J. Pharm. Sci. 93, 279–288 (2003).

Knoblauch, M., Dagnino-Acosta, A. & Hamilton, S. L. Mice with RyR1 mutation (Y524S) undergo hypermetabolic response to simvastatin. Skelet. Muscle 3, 22 (2013).

Gonzalez, A., Iles, T. L., Iaizzo, P. A. & Bandschapp, O. Impact of statin intake on malignant hyperthermia: an in vitro and in vivo swine study. BMC Anesthesiol. 20, 270 (2020).

Metterlein, T. et al. Statins alter intracellular calcium homeostasis in malignant hyperthermia susceptible individuals. Cardiovasc Ther. 28, 356–360 (2010).

Venturi, E. et al. Simvastatin activates single skeletal RyR1 channels but exerts more complex regulation of the cardiac RyR2 isoform. Br. J. Pharm. 175, 938–952 (2018).

Lindsay, C., Musgaard, M., Russell, A. J. & Sitsapesan, R. Statin activation of skeletal ryanodine receptors (RyR1) is a class effect but separable from HMG-CoA reductase inhibition. Br. J. Pharm. 179, 4941–4957 (2022).

des Georges, A. et al. Structural basis for gating and activation of RyR1. Cell 167, 145–157 e17 (2016).

Ma, R. et al. Structural basis for diamide modulation of ryanodine receptor. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 1246–1254 (2020).

Lin, L. et al. Cryo-EM structures of ryanodine receptors and diamide insecticides reveal the mechanisms of selectivity and resistance. Nat. Commun. 15, 9056 (2024).

Roston, T. M. et al. The clinical and genetic spectrum of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: findings from an international multicentre registry. Europace 20, 541–547 (2018).

Cholak, S. et al. Allosteric modulation of ryanodine receptor RyR1 by nucleotide derivatives. Structure 31, 790–800.e4 (2023).

Chen, Y. S. et al. Cryo-EM investigation of ryanodine receptor type 3. Nat. Commun. 15, 8630 (2024).

Chi, X. et al. Molecular basis for allosteric regulation of the type 2 ryanodine receptor channel gating by key modulators. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25575–25582 (2019).

Istvan, E. S. & Deisenhofer, J. Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. Science 292, 1160–1164 (2001).

Riazi, S., Kraeva, N. & Hopkins, P. M. Malignant hyperthermia in the post-genomics era: new perspectives on an old concept. Anesthesiology 128, 168–180 (2018).

Gillard, E. F. et al. A substitution of cysteine for arginine 614 in the ryanodine receptor is potentially causative of human malignant hyperthermia. Genomics 11, 751–755 (1991).

MacLennan, D. H. & Phillips, M. S. Malignant hyperthermia. Science 256, 789–794 (1992).

Woll, K. A., Haji-Ghassemi, O. & Van Petegem, F. Pathological conformations of disease mutant Ryanodine Receptors revealed by cryo-EM. Nat. Commun. 12, 807 (2021).

Stern, R. H. et al. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships of atorvastatin, an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor. J. Clin. Pharm. 40, 616–623 (2000).

Truong, K. M. & Pessah, I. N. Comparison of chlorantraniliprole and flubendiamide activity toward wild-type and malignant hyperthermia-susceptible ryanodine receptors and heat stress intolerance. Toxicol. Sci. 167, 509–523 (2019).

Haji-Ghassemi, O. et al. Cryo-EM analysis of scorpion toxin binding to Ryanodine Receptors reveals subconductance that is abolished by PKA phosphorylation. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf4936 (2023).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Bepler, T. et al. Positive-unlabeled convolutional neural networks for particle picking in cryo-electron micrographs. Nat. Methods 16, 1153–1160 (2019).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

He, J., Li, T. & Huang, S.-Y. Improvement of cryo-EM maps by simultaneous local and non-local deep learning. Nat. Commun. 14, 3217 (2023).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D., Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Afonine, P. V. et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Struct. Biol. 74, 531–544 (2018).

Melville, Z. et al. A drug and ATP binding site in the type 1 ryanodine receptor. Structure 30, 1025–1034.e4 (2022).

Croll, T.I. ISOLDE: a physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 74, 519–530 (2018).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010).

Yuchi, Z., Lau, K. & Van Petegem, F. Disease mutations in the ryanodine receptor central region: crystal structures of a phosphorylation hot spot domain. Structure 20, 1201–1211 (2012).

Yuchi, Z. et al. Crystal structures of ryanodine receptor SPRY1 and tandem-repeat domains reveal a critical FKBP12 binding determinant. Nat. Commun. 6, 7947 (2015).

Muenks, A., Zepeda, S., Zhou, G., Veesler, D. & DiMaio, F. J. N. C. Automatic and accurate ligand structure determination guided by cryo-electron microscopy maps. Nat. Commun. 14, 1164 (2023).

Laskowski, R. A. & Swindells, M. B. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model 51, 2778–2786 (2011).

Sali, A. & Blundell, T. L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815 (1993).

Smart, O. S., Neduvelil, J. G., Wang, X., Wallace, B. & Sansom, M. S. J.J.o.m.g. HOLE: a program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 354–360 (1996).

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by an NIH grant (R01 HL170144) to H.V. and F.V.P. Cryo-EM datasets were screened and collected at the High Resolution Macromolecular Electron Microscopy (HRMEM) facility at the University of British Columbia (https://cryoem.med.ubc.ca). We thank Claire Atkinson and Natalie Strynadka. HRMEM is funded by the Canadian Foundation of Innovation and the British Columbia Knowledge Development Fund. We thank the late Rebecca Sitsapesan for useful discussions at the start of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.V.P. and H.V. supervised the work. S.M. and C.V. carried out experiments and data analysis. F.V.P. and S.M. wrote the manuscript and all authors edited the document.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Angela F. Dulhunty, Wayne Hendrickson and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Molinarolo, S., Valdivia, C.R., Valdivia, H.H. et al. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals sequential binding and activation of Ryanodine Receptors by statin triplets. Nat Commun 16, 11508 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66522-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66522-0

This article is cited by

-

Statins, skeletal muscle, and ryanodine receptor activation: resolving a 30-year mystery behind statin myotoxicity

Cardiovascular Diabetology – Endocrinology Reports (2025)