Abstract

The stratified structure of organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) confines much of the generated light within substrates or organic layers, limiting outcoupling to air. Macroscale half-ball lenses extract most substrate-trapped light but compromise the inherent planarity of OLEDs, while microlens arrays (MLAs), only tens of micrometres tall, preserve planarity yet provide only modest enhancements, particularly with limited lateral dimensions. Here, we introduce a systematic strategy to enhance outcoupling while maintaining near-planarity. By jointly tailoring the OLED device stack and the topography of near-planar outcoupling structures, we overcome the limited prompt extraction responsible for the modest performance of conventional MLAs. Our optimized devices reach an external quantum efficiency of 48.0% and a current efficiency of 192 cd A⁻¹, surpassing bare OLEDs (35.6%, 102 cd A⁻¹) and MLA-attached OLEDs (35.4%, 150 cd A⁻¹). This approach addresses trade-offs among intrusiveness, aperture ratio, and performance, providing a promising route to ultra-efficient, optical-crosstalk-free OLED displays.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) are electroluminescent devices with planarity capable of rendering a full-color gamut. There has been an array of endeavors to put its internal quantum efficiency (IQE) forward to unity through advances in materials science and chemistry1,2,3,4,5. This IQE approaching near unity is nonetheless shadowed by an external quantum efficiency (EQE) limited typically to ~ 20% due to a substantial portion of light subject to parasitic loss and total internal reflections at the interfaces in its stratified structure. Such losses include coupling into surface plasmon polariton (SPP) mode arising at metal-dielectric interfaces, waveguide, and substrate modes6. Many remedies to extract light coupled within the SPP and waveguide modes into the air mode have been reported and found effective7,8,9,10. For example, Jeong et al. completely eliminated the waveguide modes through systematic optical optimization11. Likewise, low-index and adequately thick electron transport layer in tandem with corrugated structures boils down to alleviation of the SPP loss6,12. However, not all the mitigated portions are converted into air mode but are redistributed to other modes, resulting in a modest reinforcement of outcoupling efficiency. One such excursion is the substrate mode arising from total internal reflection at the substrate–air interface. The substrate mode, which typically accounts for ~30% of the total power, has been outcoupled through macroscale half-ball lenses, scattering films, and microlens arrays (MLAs)7,13,14,15. Although the enhancement is the greatest with the former, the last two prevail in practice because the hemispheric lens is protrusive and large, thereby failing to keep the planarity of the OLED and hampering its applications towards display16,17. Preserving the near-planarity of the OLED, MLAs, or scattering films are broadly adopted as light extraction strategies18. Despite many efforts made to optimize its geometry, arrangement, and refractive index, however, the light outcoupling efficiency of MLAs or scattering films has remained substantially lower than that of the half-ball lens partly due to the rays reflecting back to devices13,19,20 (Fig. 1a). Moreover, they often require a large aperture ratio—the ratio of the area of an outcoupling structure to that of the OLED active area—to realize high light extraction efficiency. For example, the power emitted to the air could be enhanced by as much as 50% with MLA with an aperture ratio of 100, but the enhancement gets negligibly small, or even negative, with the aperture ratio of 421 (See Fig. 1b). When it comes to displays, MLAs or scattering layers covering an extended area degrade lucidity in pixel-to-pixel definition and are bound to incur optical crosstalk in displays, demanding an efficient in-pixel light extraction structure, which remains confined within the boundary of each pixel14.

a Conceptual illustration of light outcoupling properties of (i) macroscale half-ball, (ii) microlens array, and (iii) optical structure proposed in this work. Insets are ray diagrams thereof. b Enhancement of the external quantum efficiency (EQE) of OLEDs estimated by trans-scale optical simulation. Here, both the OLED stack and LOS designs are optimized together to maximize EQE for each of the cases. The aperture ratio is defined by the ratio of the area on which a light outcoupling structure is placed to the light-emitting area defined by the intersection of all layers from the anode to the cathode of an OLED. The \({t}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}\) is defined as the maximal height difference between two points at the outcoupling structure. c A comprehensive overview of the trans-scale optimization of the OLED structure and design strategy of the LOS topography.

Given these challenges, we herein explore a systematic optical design pathway to enable near-planar outcoupling structures with a finite aperture ratio that achieve high EQE and/or CE. To this end, we propose a two-step process comprised of (i) maximization of the inter-aperture radiant power delivery (\({\eta }_{{{{\rm{IAPD}}}}}\)) and (ii) design of low-profile light outcoupling optical structures (LOSs) tailored to yield the enhanced efficiency with almost no returning loss (See Fig. 1c). As such, we demonstrate OLEDs with their CE and EQE that approach those obtained with a half-ball lens, with the proposed LOS having the maximum height as small as 50 μm, when measured from the top of the substrate.

Results

Selection criteria for OLED stack design

A rationale often adopted to design an OLED stack when the LOS is placed on the substrate is to let the multilayer structure of the OLED maximize the power delivered to both air and substrate. In such approaches, the LOS is assumed to be large enough to be considered practically infinite in its lateral size. In practice, however, the size of the LOS can be limited by various constraints, making the assumption invalid. This discrepancy calls for alternative approaches that can take into account the subtlety associated with finite LOS dimensions.

To this end, we first define the angular transfer weight (ATW) determined by the geometrical relation between the emission aperture (EA)—the active region of an OLED—and the reception aperture (RA)—an imaginary region on which the LOS is assumed to be placed—as follows: (See Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Note 1)

where \(S\left({x}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}},\,{y}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}},\,{\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\right)\) refers to the circumference length of the cone constituted by the rays emanated from \(({x}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}},\,{y}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}})\) with a polar angle of \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) that reach the RA, and \(({x}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}},\,{y}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}})\) refers to in-EA spatial coordinates, respectively. (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) ATW is closely related to how well the rays emanating with the polar angle \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) convey their radiant power from the EA to RA. To be more specific, the power transferred from EA to RA is proportional to the overlap integral between \({{{\rm{ATW}}}}({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}})\) and to-substrate angular intensity \({I}_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\right),\) i.e., \(\int {I}_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\right){{{\rm{ATW}}}}\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\right)d{\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\,\left[\equiv {\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}\left({r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}},{r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}},\,{t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\right)\right],\) in which \({r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\), \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}\), and \({t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) are the radii of EA and RA and the vertical spacing between EA and RA, respectively. If \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}\gg {r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\), \({{{\rm{ATW}}}}\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\right)\) can be non-zero even for \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) approaching 90 degrees, making outcoupling possible for a wider range of angles but at the expense of the large LOS dimension; on the other hand, if \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}\) is comparable to \({r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\), \({{{\rm{ATW}}}}\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\right)\) can drop to zero even at a relatively small \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\), limiting the light extraction of the rays with large \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) (Refer to Fig. 2c for exemplary ATWs for several \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) ratios in the case of concentric circular apertures with \({t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) of 1.4 \({r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\)).

a Cones of rays emanating with a polar angle of \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) from different parts of the emission aperture. Here, \(S\) is the length of the overlap between the RA and the ray cone. b Cross-sectional view of the apertures, ray cones, and the OLED. c The ATW for systems with different aperture ratios. Here, \({t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) is fixed to 1.4 and both emission and reception apertures are assumed to be circular with an overlapped centrosymmetric axis. d–f Global optimization of the OLED structure that maximizes, \(\int {I}_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\right)\sin {\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}d{\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\) (d), \(\int {I}_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\right)\sin {\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}d{\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) (e), and \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}=\int {I}_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\right){{{\rm{ATW}}}}({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}})d{\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) (f), respectively. The stars indicate the (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\), \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\)) that maximizes each integral. g To-substrate angular emission intensity of the OLEDs with their (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\), \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\)) of (50 nm, 30 nm), (50 nm, 50 nm), and (70 nm, 140 nm), respectively. h The ratio of the power emitted from the EML to the radiant power received by the reception aperture in the geometry of \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}=2\) and \({t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}=1.4\). i Design rule of the optical structure cross-section comprised of C- and S-edges. j The cross-sections of optical structures designed with its weighting function of 30° lowpass (LP30-LOS) and constant functions (UH-LOS), respectively and optimized for the OLED with its (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}=50\,{{{\rm{nm}}}}\), \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}=50\,{{{\rm{nm}}}}\)).

When optimized for OLEDs based on an emitter of Ir(dmppy-ph)2tmd22 with dipole-embedded microcavity model23,24,25 for maximization of air mode or air plus substrate mode, the thicknesses of electron and hole transport layers (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\) and \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\), respectively) were found to be (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\), \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\)) = (50 nm, 30 nm) or (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\), \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\)) = (70 nm, 140 nm), respectively (Fig. 2d, e). When optimized for maximization of \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}\left({r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}},{r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}},\,{t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\right)\), on the other hand, they were found to be both 50 nm (Fig. 2f), in contrast to the aforementioned (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\), \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\)), which have been widely used in the field.

As shown in Fig. 2g, the OLED optimized for the maximal \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}\) turns out to exhibit emission concentrated in low-\({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) range so that most of the emitted light from EA meets the RA. This stronger low-\({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) emission of \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}\)-maximized OLED (i.e., \({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\) = \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\) = 50 nm) enabled the ratio of power emitted from the EML to the power reaching the RA (\({\eta }_{{{{\rm{IAPD}}}}}\)) to be higher than 47% despite its lower to-substrate power transfer (\({\eta }_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\)) than the OLED optimized for the maximal air plus substrate criteria (Fig. 2h). Likewise, trans-scale simulations for varying \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) ratios and \({t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) further corroborate that the pursuit of the largest \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}\) always leads to higher \({\eta }_{{{{\rm{IAPD}}}}}\) than that of the OLED optimized for the maximal \({\eta }_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) (See Supplementary Fig. 5). This makes the maximal \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}\) condition a preferred selection criterion for the optimization of OLEDs having a finite size of light extraction structures on substrates.

Optical design of low-profile LOSs

With the OLED stack designed to have the largest \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}\) and thus impart the highest radiant power delivered from EA to RA, we further propose the LOS design principle to extract light garnered within the RA into air with minimal loss and the smallest height of the LOS measured from the substrate surface (\({t}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}\)). To this end, we first suppose that the topography of the LOS consists of alternating curved edges (C-edges) and straight edges (S-edges), as shown in Fig. 2i (Supplementary Note 2 for details). The S-edges were set parallel to the rays emanating from the EA center to prevent them from being disturbed by the S-edges and not seeing the C-edges. (Supplementary Fig. 3) Then, the C-edges were designed to maximize the power output under a given weighting function \(W\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\right)\) [\(\equiv {\gamma }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}^{\left(W\right)}\)]:

The weighting function endows a degree of freedom in the design of the LOS topography according to the constraints set by applications. For example, \(W\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\right)\) given by a step-wise low-pass function with its cutoff angle (\({\theta }_{{{{\rm{cutoff}}}}}\)) results in the maximized EQE or PE for the light output confined within \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{cutoff}}}}}\) (\({{{{\rm{EQE}}}}}_{{\theta }_{{{{\rm{cutoff}}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{PE}}}}}_{{\theta }_{{{{\rm{cutoff}}}}}}\), respectively). With this \(W\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\right)\), the designed LOS would tend to maximize EQE or CE if \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{cutoff}}}}}\) is set as 90° or as a sufficiently small value, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). Two epitomes of the LOS cross-section [\({z}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}\left(r\right)\)] dictated by two weighting functions of (i) the stepwise lowpass with \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{cutoff}}}}}\) = 30° (LP30-LOS) and (ii) that with \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{cutoff}}}}}\) = 90° (UH-LOS) are shown in Fig. 2j. In each case, the power reaching the 30° cone and the total upper hemisphere is intended to be maximized, respectively.

It is noteworthy that the topography of the LOS in both cases is dissimilar to the LOS designed under a point source approximation. i.e., \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\gg 1\). The LOS for a point source (PS-LOS) is designed by radially compressing a macroscale half-ball toward the point source (Supplementary Fig. 7), thereby reducing \({t}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}\) to a significant degree. Contrary to the PS-LOS, whose optical refracting power (reciprocal of the focal length) is nearly equivalent to that of a macroscale half-ball lens (Supplementary Fig. 8), both the LP30-LOS and UH-LOS feature nearly flat surfaces in the vicinity of the centrosymmetric axis (Fig. 2j). This mesa-like structure at the central zone is essential in getting a stronger emission toward small \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\), especially when \({I}_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) is concentrated in low-\({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) regime to match with the finite size of RA (Supplementary Fig. 9).

It should also be noted that the proposed LOS design resorts to refraction and thus is limited by the critical angle at the LOS-air interface. Therefore, there exists a limit in \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) that can be directed into \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\le {\theta }_{{{{\rm{cutoff}}}}}\) through refraction, which delimits the maximal radius of LOS (\({R}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}\)) (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 10). In particular, \({R}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}\) may deviate from \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}\) for large aperture ratios (In this case, \({R}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}} < {r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}\); See Supplementary Note 3). Of note, \({R}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}\) tends to increase with \({n}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) as higher refractive power enables rays with a given \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) to be refracted into smaller \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\), leading to a higher performance enhancement as discussed later (Supplementary Fig. 11). In the same vein, \(\left|\frac{d{z}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}}{{dr}}\right|\) in the C-edges of the LP30-LOS is larger than that of the UH-LOS, as the former requires a larger incident angle to refract it into a smaller \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\) (Fig. 2j).

Device performance

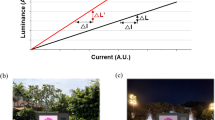

To demonstrate the outcoupling enhancements anticipated by optical simulations for the proposed approach, the LP30-LOS designed for \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\), \({t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\), and \({t}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) of 2, 1.4, and 0.05, respectively, was 3D-printed on a carrier glass through two-photon polymerization. The refractive index of the LP30-LOS was matched to that of the carrier glass and the substrate of the OLED (\({n}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) = 1.51 at \(\lambda\) = 589 nm) so that no tangible refraction occurs at the interface between the LP30-LOS and the carrier glass (Fig. 3a, b). The carrier glass and the glass substrate of the OLED were optically cemented through the index-matching fluid (See “Methods”). When applied onto an OLED with \({r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) of 1 mm, the LP30-LOS resulted in little or no optical artifact other than apparent pixel size expansion and blurring owing to the edges, contrary to the case of MLAs (See Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 12).

a A photo of the LP30-LOS 3D-printed onto a carrier glass through two-photon polymerization (2PP). Differed curvatures at each C-edge result in the absence of a single image formed. Scale bar, 5 mm. b A close-up image of the LP30-LOS. Scale bar, 1 mm. c The OLED and the LP30-LOS, whose structure is optimized to \({I}_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\left({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\right)\) thereof. d A bare (left) and MLA-attached (right) OLEDs. Scale bar, 5 mm. e–j, The angular emission intensity (e), \(J-V-L\) characteristics (f), CE (g), angle-resolved spectrum (h), EQE (i), and power efficiency (j) of the OLEDs with and without the LP30-LOS and with MLA.

The LOSs placed on top of the OLED extracted light that would otherwise be confined within the substrate into the air without any electrical modification (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 13). Both angular emission intensity profiles and CEs were in good agreement with the trans-scale optical simulations. Moreover, the LOS proposed herein effectively reduced the reflection at the LOS (or substrate)-air interface at no expense of beam uniformity (Supplementary Figs. 14–16). The former is especially important in that it promotes a portion of light that is outcoupled promptly without going through multiple reflections back to the OLED stack, which can incur optical power loss to parasitic absorption and to the light blocking structures (e.g., black matrix) that are often employed in displays to suppress optical crosstalk among adjacent pixels26.

The OLED with the LP30-LOS marked the peak EQE and CE of 48.0% and 192 cd A−1, which were greatly improved from 35.6% to 102 cd A−1 of the bare OLEDs and 35.4% and 150 cd A−1 of the OLED with an MLA defined within a circle with a radius of 2 mm (Fig. 3e–j and Supplementary Fig. 17). The relatively smaller increase in EQE compared to the CE implies that the LP30-LOS refracted light into small-\({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\) regime as intended, resulting in a sub-Lambertian angular emission pattern of the OLED beneficial to mobile or artificial reality (AR) -type display applications. Moreover, the ratios of the total number of photons collected within \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\le 30^\circ\) to the number of excitons injected into the emission layer (i.e., EQE30) were 16.4% and 9.30% for OLEDs with and without the LP30-LOS, respectively. It should be noted that the EQE exceeds \({\eta }_{{{{\rm{IAPD}}}}}\) because the non-LOS region may also contribute to radiant power extraction for small \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) of 2 (See Supplementary Fig. 18 and Ray 2 in Fig. 1c). Of note, the EQE, EQE30, and CE can go up to 57.2%, 18.4%, and 217 cd A−1, respectively, for a larger \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) of 3 (Supplementary Fig. 19 and Supplementary Table 1). It should also be highlighted that the proposed LOS design can achieve higher EQE and CE compared to other light outcoupling technologies harnessing refraction, interference, and scattering, despite being surprisingly compact in lateral dimension and thickness (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 20).

Given the improvements by the LOSs, we tested three candidate OLEDs, respectively designed to maximize \({\eta }_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{air}}}}}\), \({\eta }_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\), and \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}\) to corroborate the validity of the proposed optimization (Table 2 and Supplementary Figs. 17, 21, and 22). In the absence of LOS, the OLED with the maximized \({\eta }_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{air}}}}}\) (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\) = 50 nm and \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\) = 30 nm) marked the largest EQE and CE of 36.0% and 105 cd A−1, respectively. When the LP30-LOS was attached, however, the OLED optimized with \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}\) (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\,\)= \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\) = 50 nm) surpassed the others with the identical LP30-LOS. Moreover, a full trans-scale optical simulation indicates that the maximal EQE and EQE30 of OLEDs with their LOSs (\({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) = 2) optimized with \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}^{(W)}\) were observed in the vicinity of the \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}\)-optimized OLED stack structure of (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\) = 50 nm, \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\) = 50 nm) and vice versa (Supplementary Figs. 23 and 24). These results reaffirm the need for both steps: (i) OLED stack design to maximize \({\eta }_{{{{\rm{IAPD}}}}}\); and (ii) LOS design tailored to the efficient light outcoupling under a given constraint for angular distribution. It should also be noted that the angular emission intensity profile can vary depending on the LOS-attached onto the substrate (Table 2). It then leads to different Lambertian factors (\({f}_{{{{\rm{LB}}}}}\)) defined by:

where \({I}_{{{{\rm{LB}}}}}(\theta )\) refers to the angular intensity in air of a Lambertian source having the same intensity in the normal direction (=\(I(0)\)) as an OLED of interest. It is noteworthy that \({f}_{{{{\rm{LB}}}}}\), in addition to CE, can influence PE and EQE significantly; for example, the ratio of PE between two different light sources 1 and 2 (with the same device area) is given by [\({\eta }_{{{{\rm{CE}}}}1}/{\eta }_{{{{\rm{CE}}}}2}\)] [\({f}_{{{{\rm{LB}}}}1}/{f}_{{{{\rm{LB}}}}2}\)] [\({V}_{1}/{V}_{2}\)]−1. The ratio of EQE also follows the similar scaling behavior approximately.

Trans-scale optical simulations also countenance the rationality of both OLED stack and LOS design. First, the EQE of UH-LOS- and CE of LP30-LOS-attached OLEDs reached higher figures than those of MLA-attached and bare OLEDs for all combinations of (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\), \({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\)) as shown in Fig. 4 (See also Supplementary Figs. 25–29). Furthermore, an EQE of 87.2% and CE of 410 cd A−1, comparable to those of macroscale half-ball-attached OLEDs, are respectively attainable with UH-LOS and LP30-LOS, whereby MLA marks 56.5% and 193 cd A−1 for the maximum (Supplementary Figs. 30 and 31). It should be noted that the LOS height (\({t}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}\)) can be dwindled down to that of MLAs at no expense of the light outcoupling performance, always marking higher than those of MLAs, as long as the geometric optical approximation kept valid27,28 (Supplementary Figs. 32 and 33).

a, b, The EQE (a) and CE (b) of the OLEDs with LP30-LOSs with different \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) and \({t}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\). Here, \({n}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) and \({t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) are fixed to 1.51 and 1.4, respectively. c, d The EQE (c) and CE (d) of the OLEDs with LP30-LOSs with different \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) and \({t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\). Here, \({n}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) and \({t}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) are fixed to 1.51 and 0.05, respectively. e, f The EQE (e) and CE (f) of the OLEDs with LP30-LOSs with different \({n}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) and \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\). Here, \({t}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) and \({t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) are fixed to 0.05 and 1.4, respectively. g, h The impact of the in-plane misalignment to the EQE (g) and CE (h) of the OLEDs with LP30-LOSs. Here, \({t}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\), \({t}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\), and \({n}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) are fixed to 1.4, 0.05, and 1.51, respectively.

Second, the misalignment of the LP30-LOSs had a limited impact on both EQE and CE, which retained more than 95% of the initial value at large misalignments (\(\Delta r/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\)) of 35% and 15%, respectively, although the S- and C-edges were designed on the basis of concentric alignment of the two apertures and the LOS (See Fig. 4g, h for optical simulations and Supplementary Fig. 34 for experimental validation). Similarly, the performance enhancements by the UH-LOSs and PS-LOSs were virtually insensitive to a reasonable amount of horizontal misalignment (e.g., 10–20%), though asymmetrical angular intensity distribution becomes inevitable if misalignment gets larger (Supplementary Figs. 26 and 27). These margins are compatible with aligning modalities widely used in photo and nanoimprint lithographic processes and thus fully open up their industrial uses29,30,31.

Discussion

In summary, we developed a two-step methodology to enable OLEDs with their light outcoupling efficiency comparable to that of a macroscale half-ball lens and protrusion as thin as MLAs. The framework is comprised of dual steps: (i) OLED stack design to maximize the radiant power delivery (\({\eta }_{{{{\rm{IAPD}}}}}\)) between emitting and receiving apertures (EA and RA) and (ii) low-profile LOS design to maximize the outcoupling to air with a given preference to specific angular distribution (e.g., center-focused or widely distributed, etc.) The former was done by defining the ATW function between the EA of a source and the RA of a light outcoupling structure (LOS), both of which have finite lateral dimensions. The overlap integral (\({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{ATW}}}}}\)) of ATW and intensity for a given direction within a substrate was conceived and validated as a parameter to be maximized for optimization of thin-film OLED stacks to be coupled with LOS. As such, \({\eta }_{{{{\rm{IAPD}}}}}\) was maximized without demanding heavy computational resources for Monte-Carlo-type ray-tracing simulations. Then, the LOS was designed to efficiently extract substrate modes collected within the RA into the air in targeted angular characteristics. This framework provides the structures of an OLED and the associated LOS tailored to maximize the desired OLED performances, even when the lateral size of the LOS is limited. Combined with the generous misalignment margin compatible with currently used semiconductor technologies, the proposed LOSs offer exceptional performance enhancements comparable to a macroscale half-ball lens while maintaining near-planarity and small \({r}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) for in-pixel LOS configurations essential for optical crosstalk-free operation. Taking advantage of the degree of freedom in the LOS design enabled by the weighting function \(W({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}})\) to yield a desired \({I}_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}({\theta }_{{{{\rm{out}}}}})\), an ultrahigh EQE and CE of 48.0% and 192 cd A−1 were simultaneously achieved at the radius ratio of \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) = 2 (\({r}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) = 1.95). Moreover, they are boosted to 57.2% and 217 cd A−1 when it comes to slightly larger \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) = 3 (\({r}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) = 2.63).

The noteworthy enhancements by the LOSs differentiate them from conventional outcoupling structures in two major ways. First, the proposed LOS avoids the reflection back into the organic stack to minimize photon losses that can occur upon reflection through destructive interference in a cavity or during multiple passages via attenuation (Supplementary Fig. 14). Therefore, the strategy reported herein can be expanded to optoelectronic devices with layers having a relatively large absorption or those relying on strong cavity resonance. For instance, perovskite light-emitting diodes are known to exhibit relatively small Stokes shifts, enabling photon recycling. However, achieving a PLQY of 100% is typically challenging, and therefore, recursive photon recycling leads to additional optical losses32. The proposed LOS, which shows strength in prompt outcoupling, can therefore be applied to enhance performance by suppressing parasitic absorption33,34,35. Second, the proposed LOSs can work effectively even for small \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}/{r}_{{{{\rm{EA}}}}}\) ratio, making them suitable in various scales for both per-pixel cases in displays and large-area cases in lighting devices. The compatibility of the proposed LOS with in-pixel configuration and the suppressed reflection at LOS/air interfaces reduces optical artifacts and pixel-to-pixel cross-talks, opening up an effective yet controllable path towards highly efficient OLED displays.

Methods

Optical simulation

The optical simulations in this work are comprised of simulations in coherent and incoherent regimes. The optical simulations in a wave optics regime were performed with a custom-built MATLAB code based on the classical dipole model and the transfer matrix method previously reported23,24,25. The refractive indices of the layers, PL spectrum, and quantum yield of the EMLs, and emitting dipole orientations of the EMLs were taken into account. The emission zone was postulated to be positioned at the middle of the co-deposited EML (12.5 nm apart from each interface). The optical simulation itself considers the Purcell effect. The to-substrate emission profile \({I}_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}},\,\lambda,\,{{{\rm{polarization}}}})\) was collected by assuming a semi-infinite glass substrate. The reflectance of the OLED layer stack (\({R}_{{{{\rm{OLED}}}}}({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}},\,{{{\rm{polarization}}}})\)) was calculated using the transfer matrix method at the peak emission wavelength. The LOS topographies were calculated with polarization-averaged \({I}_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}({\theta }_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}})\) at the peak wavelength for computational brevity. Then, monochromatic ray-tracing simulations at the peak emission wavelength were performed by a commercial software (LightToolsTM), taking into account \({R}_{{{{\rm{OLED}}}}}\), \({I}_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\), \({z}_{{{{\rm{LOS}}}}}\), and polarization. The efficiencies and angular emission intensities were estimated by linearly interpolating those of s-/p-polarization with the ratio defined by the power fraction of each polarization mode, as simulations with polarization-averaged \({R}_{{{{\rm{OLED}}}}}\) and \({I}_{{{{\rm{to}}}}-{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) may result in an underestimation of \({I}_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}\) and the efficiencies accordingly. The ray-tracing simulations were performed with a ray number of at least 50,000,000.

Fabrication and characterization of OLEDs

An organic stack comprised of TAPC (\({d}_{{{{\rm{HTL}}}}}\)), TCTA (10 nm), TCTA:Ir(dmppy-ph)2tmd:B3PyMPM (25 nm, 4 wt% dopant, co-evaporation), B3PyMPM (\({d}_{{{{\rm{ETL}}}}}\)), LiF/Al (1 nm/100 nm) is thermally deposited onto 25 × 25 mm glass substrates with half-patterned 150-nm-thick ITO layers (AMG, South Korea) in a vacuum thermal evaporator with its pressure less than 5 × 10−7 Torr without breaking the vacuum. TAPC, TCTA, and B3PyMPM were purchased from Nichem Fine Technology Co. Ltd. The heteroleptic phosphorescent emitter Ir(dmppy-ph)2tmd was purchased from Lumtec. The LiF (99.99%) and Al pellets (99.999%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and Trading Ulet (Yongin, South Korea), respectively.

The active area of all devices was defined by the photoresist pattern and fixed to a 3.14 mm2. The current density, luminance, and angle-dependent electroluminescence intensity and spectrum were measured using a custom-built goniometer system comprised of a source meter (Keithley 2400), a calibrated Si photodiode (FDS100-Cal, Thorlabs, Inc.), and a fiber optic spectrometer (EPP2000, StellarNet Inc.) in a nitrogen-filled glovebox, respectively.

The LOSs were printed with a transparent resin with a refractive index of 1.51 (IP-S, Nanoscribe, Inc.) onto carrying glasses using two-photon polymerization by Jive Solutions (Hwaseong, South Korea). The MLA pattern was designed as an array of closest-packed hemispheric microlenses with a radius of 30 μm within the RA defined by \({r}_{{{{\rm{RA}}}}}\) = 2 mm. A macroscale half-ball with a radius of 2 mm made of N-BK7 (45-933, Edmund Optics) was optically attached to the carrier glass using NOA74 (Norland Products, Inc.). The side faces of the LOS-carrying glasses and the OLED substrate were blocked with a mixture of black ink (STSM-1N, Shachihata) and epoxy resin (EP-05, AXIA) to obviate any outcoupling of the substrate and waveguide mode, which might result in an overestimation of efficiencies (See Supplementary Fig. 35). The LOS-carrying glass and the OLED substrate (both with a refractive index of 1.51 and a thickness of 0.7 mm) are optically attached using an index-matching fluid (Refractive Index Liquid Series A 1.516, Cargille Laboratory) with a refractive index of 1.516. The EQE and \({{{\rm{EQ}}}}{{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{\theta }_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}}\) were calculated for the measured EL intensity and spectrum by fully considering the angular distribution.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code for angular transfer weight calculation is available on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17504835).

References

Adachi, C., Baldo, M. A., Thompson, M. E. & Forrest, S. R. Nearly 100% internal phosphorescence efficiency in an organic light-emitting device. J. Appl. Phys. 90, 5048–5051 (2001).

Uoyama, H., Goushi, K., Shizu, K., Nomura, H. & Adachi, C. Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 492, 234–238 (2012).

Hirata, S. et al. Highly efficient blue electroluminescence based on thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Nat. Mat. 14, 330–336 (2015).

Lin, T. et al. Sky-blue organic light emitting diode with 37% external quantum efficiency using thermally activated delayed fluorescence from spiroacridine-triazine hybrid. Adv. Mater. 28, 6976–6983 (2016).

Hamze, R. et al. Eliminating nonradiative decay in Cu(I) emitters: >99% quantum efficiency and microsecond lifetime. Science 363, 601–606 (2019).

Salehi, A., Fu, X., Shin, D. & So, F. Recent advances in OLED optical design. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1808803 (2019).

Möller, S. & Forrest, S. R. Improved light out-coupling in organic light emitting diodes employing ordered microlens arrays. J. Appl. Phys. 91, 3324–3327 (2002).

Sun, Y. & Forrest, S. R. Enhanced light out-coupling of organic light-emitting devices using embedded low-index grids. Nat. Photon. 2, 483–487 (2008).

Koo, W. H. et al. Light extraction from organic light-emitting diodes enhanced by spontaneously formed buckles. Nat. Photon. 4, 222–226 (2010).

Kim, J., Lee, J., Moon, C., Kim, S. & Kim, J. Highly enhanced light extraction from surface plasmonic loss minimized organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 25, 3571–3577 (2013).

Jeong, C., Park, Y.-B. & Guo, L. J. Tackling light trapping in organic light-emitting diodes by complete elimination of waveguide modes. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg0355 (2021).

Lin, B.-Y. et al. Effects of electron transport layer thickness on light extraction in corrugated OLEDs. Opt. Express 30, 18066 (2022).

Sun, Y. & Forrest, S. R. Organic light emitting devices with enhanced outcoupling via microlenses fabricated by imprint lithography. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 073106 (2006).

Song, J. et al. Lensfree OLEDs with over 50% external quantum efficiency via external scattering and horizontally oriented emitters. Nat. Commun. 9, 3207 (2018).

Wang, B.-K. et al. Realization of exceeding 80% external quantum efficiency in organic light-emitting diodes using high-index substrates and highly horizontal emitters. Org. Electron. 89, 106049 (2021).

Jeon, S. et al. High-quality white OLEDs with comparable efficiencies to LEDs. Adv. Opt. Mater. 6, 1701349 (2018).

Lee, J. et al. Synergetic electrode architecture for efficient graphene-based flexible organic light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 7, 11791 (2016).

Shin, H.-J. et al. Technical progress of OLED displays for premium TVs. SID Symposium Digest 53, 673–676 (2022).

Peng, H., Ho, Y. L., Yu, X.-J., Wong, M. & Kwok, H.-S. Coupling efficiency enhancement in organic light-emitting devices using microlens array—theory and experiment. J. Display Technol. 1, 278–282 (2005).

Sharma, R. K., Deepak & Katiyar, M. Effect of various microlens parameters on enhancement of light outcoupling efficiency of organic light emitting diode. Org. Electron. 38, 121–129 (2016).

Lin, H.-Y. et al. Patterned microlens array for efficiency improvement of small-pixelated organic light-emitting devices. Opt. Express 16, 11044 (2008).

Kim, K.-H., Ahn, E. S., Huh, J.-S., Kim, Y.-H. & Kim, J.-J. Design of heteroleptic Ir complexes with horizontal emitting dipoles for highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes with an external quantum efficiency of 38%. Chem. Mater. 28, 7505–7510 (2016).

Neyts, K. A. Simulation of light emission from thin-film microcavities. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 15, 962 (1998).

Furno, M., Meerheim, R., Hofmann, S., Lüssem, B. & Leo, K. Efficiency and rate of spontaneous emission in organic electroluminescent devices. Phys. Rev. B 85, 115205 (2012).

Moon, C.-K., Kim, S.-Y., Lee, J.-H. & Kim, J.-J. Luminescence from oriented emitting dipoles in a birefringent medium. Opt. Express 23, A279 (2015).

Huang, Y., Hsiang, E.-L., Deng, M.-Y. & Wu, S.-T. Mini-LED, Micro-LED and OLED displays: present status and future perspectives. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 105 (2020).

Tsai, C.-H. et al. Characterizing coherence lengths of organic light-emitting devices using Newton’s rings apparatus. Org. Electron. 11, 439–444 (2010).

Xie, G. et al. Measuring and structuring the spatial coherence length of organic light-emitting diodes. Laser Photonics Rev. 10, 82–90 (2016).

Takeishi, H. & Sreenivasan, S. V. Nanoimprint system development and status for high volume semiconductor manufacturing. In Alternative Lithographic Technologies VII. (eds Resnick, D. J. & Bencher, C.) Vol. 9423, 49–57 (SPIE, 2015).

Traub, M. C., Longsine, W. & Truskett, V. N. Advances in nanoimprint lithography. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 7, 583–604 (2016).

Jin, H. & Qi, Y. Review of overlay error and controlling methods in alignment system for advanced lithography. In Thirteenth International Conference on Information Optics and Photonics (CIOP 2022), (ed. Yang, Y.) Vol. 12478, 1002–1017 (SPIE, 2022).

Cho, C., Sun, Y., You, J., Cui, L. & Greenham, N. C. Enhanced photon recycling enables efficient perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2411556 (2024).

Cho, C. et al. The role of photon recycling in perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 11, 611 (2020).

Cho, C. & Greenham, N. C. Computational study of dipole radiation in re-absorbing perovskite semiconductors for optoelectronics. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003559 (2021).

Mei, G. et al. Microcavity design upping light extraction efficiency over 50% in high-index perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2300912 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00344386 and RS-2024-00416978), by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIR) (2410006837, HRD Program for Industrial Innovation), and by the Korea Planning & Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIR) (RS-2025-25452683). This work was also supported by the KAIST Undergraduate Research Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J.K. conceived the idea and designed the project. M.J.K. constructed a theoretical framework of the ATW and LOS design. M.J.K., J.K., and S.Y. designed the experiments together. J.K. performed wave-optics simulations and fabricated the OLEDs. M.J.K. set up and performed trans-scale ray-tracing simulations. M.J.K. and J.K. characterized the OLEDs. J.K. assisted M.J.K. in analyzing data acquired from the OLED measurements. M.J.K. wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures and illustrations. S.Y. supervised the project. All authors read and discussed the results of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, M., Kim, J. & Yoo, S. Near-planar light outcoupling structures with finite lateral dimensions for ultra-efficient and optical crosstalk-free OLED displays. Nat Commun 16, 11606 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66538-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66538-6