Abstract

Cambodia achieved the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets in 2017; however, clinic congestion, stigma, and mental health disparities continue to challenge sustained HIV care. This quasi-experimental study evaluated a community-based antiretroviral therapy delivery model compared with multi-month dispensing among people living with HIV across 20 clinics (N = 4,089) from 2021 to 2023. Baseline and endline surveys and clinical data assessed treatment adherence, viral suppression, retention in care, stigma, depressive symptoms, and quality of life. Both approaches achieved high retention in care (>97%) and viral suppression rates (>99%). The community-based model showed significantly improved adherence, reduced depressive symptoms, and higher physical health-related quality of life. Modest reductions in experienced stigma were observed, but effects on internalised and anticipated stigma were inconclusive. These findings indicate that community-based antiretroviral therapy delivery effectively sustains adherence and improves health outcomes, supporting its integration into Cambodia’s HIV care system alongside interventions targeting stigma reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cambodia has made significant strides in addressing the HIV epidemic. The prevalence of HIV among adults aged 15–49 years decreased from 1.7% in 1998 to 0.5% in 2023. It was also one of the three Asia-Pacific countries to achieve the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets in 2017, defined as 90% of all people living with HIV knowing their HIV status, 90% of those diagnosed receiving sustained antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90% of those on ART achieving viral suppression1,2. As of 2023, 89% of an estimated 76,000 people living with HIV in Cambodia had been diagnosed, 89% had received sustained ART, and 87% had achieved viral suppression3. Nonetheless, further progress is necessary for Cambodia to meet the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets and eventually eliminate HIV.

In Cambodia, HIV services are provided through 74 ART clinics managed by the government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) across 25 provinces4. These clinics face significant challenges, including congestion and shortages of human resources, which impede high-quality care, especially for unstable individuals who require regular follow-ups. People living with HIV also experience substantial psychological challenges, including stigma, which is closely associated with poorer mental health outcomes5 and can negatively affect ART adherence and retention in care6,7,8,9. Additionally, specific populations, particularly those with vulnerable socioeconomic or clinical statuses and inadequate social support, are at risk of being lost to follow-up in ART10. Other concerns include missed appointments and improper storage of antiretrovirals (ARVs) after dispensing11.

Since 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) has advocated for a client-centred approach using differentiated service delivery (DSD) models tailored to the needs of people living with HIV while lessening the burden on health systems12. DSD models, such as community-based ART distributions, as seen in Mozambique and Lesotho, have shown promising results in improving ART adherence, alleviating clinic congestion, and enhancing mental health for people living with HIV13,14.

In Cambodia, where community-based services are integral to the national HIV response, the National Centre for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology, and STD (NCHADS) initiated the multi-month dispensing (MMD) model in 2017. This model allows clinically stable individuals—typically those on ART for at least 1 year, with viral suppression and no significant clinical complications—to visit ART clinics every 3–6 months, thereby reducing travel burdens15. Building on this, a quasi-experimental study introduced a Community-based ART Delivery (CAD) model, further decentralising care by integrating ARV distributions within peer-led community networks16.

The CAD model represents a contextually adapted, peer-led approach to delivering differentiated HIV services in Cambodia. Building on earlier models, such as Community ART Groups, which leveraged the lived experiences of people living with HIV to strengthen adherence and peer solidarity, CAD advances this paradigm by introducing greater formalisation, professionalisation, and operational alignment with national HIV programme processes. Unlike rotational or volunteer-based peer delivery systems, CAD engages people living with HIV as formally trained and compensated Community Action Workers (CAWs) to lead monthly community-based group sessions. These sessions are not limited to ART distribution, but also incorporate structured health education, treatment adherence counselling, basic health monitoring, and peer-led psychosocial support. Psychosocial support in this context comprised emotional reassurance, informational guidance, and motivational engagement, provided through structured interactions between CAWs and group participants, as well as informal peer bonding among participants themselves.

This embedded design aims to address persistent structural and psychosocial barriers to care, particularly HIV-related stigma, social isolation, and mental health burden, among stable people living with HIV in rural and underserved communities. While psychosocial interventions have been integral to other differentiated models, including those implemented in Uganda and Zimbabwe17,18, the CAD model distinguishes itself through the routinisation and institutionalisation of these components within a formally supervised, peer-delivered platform. The intervention logic drew on behavioural theory, particularly constructs from social cognitive theory and the stress-buffering model of social support19,20, which posit that peer role-modelling, emotional validation, and perceived support can reduce psychological distress and reinforce treatment adherence. Rather than layering delivery support onto community health workers, the CAD model embeds these services as standard monthly functions, integrated with national referral, reporting, and supervision systems.

Although both CAD and MMD models require biannual clinic visits for clinical monitoring and prescription renewal, the CAD model decentralises many non-clinical functions—such as routine ARV refills, adherence counselling, and basic health assessments—into the community setting. This redistribution reduces the workload of healthcare providers and enhances patient experience by limiting in-facility interactions for stable clients, while also leveraging peer networks to sustain engagement in care. The CAD model shares structural similarities with adherence clubs in sub-Saharan Africa21,22; however, it is contextually adapted to the Cambodian health system. Unlike typical ART adherence clubs, which are managed by formal cadres under standard operating procedures23,24, the CAD model is implemented by formally trained and compensated CAWs employed by community-based implementing partners, operating under national supervision and reporting frameworks. A defining feature is structured monthly contact with every participant, ensuring medication dispensing, adherence counselling, health education, and psychosocial support—even for those unable to attend group sessions—thereby maintaining continuity of care in alignment with project protocols and national HIV programme priorities.

This quasi-experimental study estimated treatment effects while accounting for baseline differences and time-invariant confounding in non-randomised settings. The resulting evidence would inform CAD’s potential institutionalisation and scale-up within Cambodia’s national HIV response, offering policy-relevant insights into implementing peer-led, community-integrated service delivery. More broadly, this evaluation contributes to the global evidence base on differentiated HIV care and supports Cambodia’s strategic transition toward integrated, person-centred models that prioritise sustainability, service quality, and long-term well-being of people living with HIV.

Results

Participant characteristics

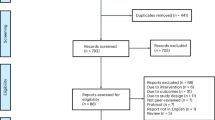

As shown in Fig. 1, 4089 people living with HIV were enroled in this study and completed baseline surveys, with 2040 (49.9%) in the CAD and 2049 (50.1%) in the MMD group. By the endline, 3977 participants (97.3%) were retained in HIV care; of those, 1626 (79.7%) in CAD and 1441 (70.3%) in MMD completed endline surveys. Among 85 participants who did not remain in HIV care, 42.4% were from CAD and 57.6% from MMD due to death, loss to follow-up, or transfer. Of those who were retained in care but did not complete endline surveys (22.9%), a higher percentage of participants were from MMD (61.6%) compared to CAD (35.2%).

Flowchart showing participant progression from enrolment to 18-month follow-up in the CAD and MMD groups. Boxes present numbers and percentages at each stage, including reasons for loss to follow-up. Arrows indicate the flow of participants. CAD community-based antiretroviral therapy delivery, MMD multi-month dispensing.

Table 1 shows that most participants were recruited from urban areas, with a higher proportion in the MMD group (75.5%) than in the CAD group (61.0%). Most participants were aged 15–49, predominantly female, married, and with a primary school education. Many were farmers, fishermen, self-employed individuals, or unemployed. MMD participants were nearly four times more likely than CAD participants to identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ+) (4.7% vs. 1.2%). Most had small families, and the median monthly household income was higher among MMD participants than in CAD participants (USD 216 vs. USD 192). A significantly higher proportion of CAD participants (25.9%) reported at least one comorbidity compared to MMD participants (17.9%). A significantly higher proportion of MMD participants were newly diagnosed with HIV (0–5 years) and newly on ART (0–5 years) compared to those in the CAD arm. Conversely, a significantly higher proportion of CAD participants had lived with HIV and received ART for 11 years or longer. However, most participants in both groups had lived with HIV and received ART for 11–20 years. Approximately half of the participants travelled less than 30 min to ART clinics, and the mean waiting time was slightly higher in the CAD group (2.2 h) than in the MMD group (1.6 h).

Implementation fidelity and group participation

As a measure of implementation fidelity, group attendance data recorded by CAWs were analysed for the period between November 2021 and March 2023. During this period, a total of 1,168 group sessions were conducted across 10 intervention sites, with a median of 79.5 sessions per site (interquartile range [IQR] = 85.5). Each site operated a median of eight groups (IQR = 5.5). The median number of participants per session was 158.6 (IQR = 161.0), corresponding to a median session attendance rate of 86.7% (IQR = 13.8%). Site-level attendance rates ranged from 71.4% to 119%, with values above 100% reflecting cumulative attendance counts across overlapping sessions. Importantly, all absentees were individually followed up and received ART refills and support through home-based or one-to-one contact. These attendance data demonstrate strong participant engagement and operational fidelity of the CAD model across all intervention sites. Detailed indicators are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

Treatment outcomes

Retention in HIV care was high in both groups, 98.2% in the CAD and 97.6% in the MMD group. More than 99.0% of participants maintained suppressed viral loads, with minimal differences between the two arms (Table 1).

The CAD and MMD groups demonstrated similar treatment outcomes, as evidenced by descriptive trends (Table 2) and robust intervention effects (Tables 3 and 4). At baseline, the CAD group had slightly lower self-reported ART adherence than the MMD group (87.0% vs. 90.3%, Table 2). By the endline, ART adherence declined modestly in both groups, but the CAD group maintained a superior trajectory (86.8% vs. 84.4% in MMD). As shown in Table 3, the CAD group had 64% higher odds of ART adherence (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.64; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.21–2.23). Table 4 confirmed a significant difference-in-difference (DiD) advantage of 5.5% (95% CI: 1.96–9.01). These findings substantiate CAD’s non-inferiority and superiority in maintaining adherence, even in the presence of baseline differences between groups.

HIV-related stigma

Table 2 shows that MMD participants were significantly more likely to report no stigma experienced at baseline than CAD participants (94.5% vs. 92.2%). At the endline, the CAD group showed a marginal improvement (92.4%), while the MMD group experienced a decline (91.3%). As shown in Table 3, adjusted models suggested a trend toward reduced stigma in the CAD group (AOR 1.48, 95% CI: 0.99–2.20), although DiD estimates were inconclusive (2.44%, 95% CI: −0.30 to 5.18, Table 4). Internal stigma increased sharply in both groups (CAD: 69.0%–80.3%, MMD: 63.4%–73.1%), while no significant differences were observed for fear of stigma.

Depressive symptoms

Both the CAD and MMD groups experienced a reduction in the proportion of participants reporting no depressive symptoms over time (CAD: 77.7%–72.7%, MMD: 83.8%–71.5%, Table 2). The decline was more pronounced in the MMD group; however, the between-group difference at the endline was not statistically significant. Adjusted models (Table 3) indicated that CAD participants had 54% higher odds of maintaining no depressive symptoms than those in the MMD group (AOR 1.54, 95% CI: 1.20–1.97). This advantage was corroborated by a significant DiD estimate of 6.8% (95% CI: 2.7–10.9; Table 4), indicating a smaller decline in the proportion of participants without depressive symptoms in the CAD group compared to the MMD group.

Quality of life (QoL)

Table 2 shows that the MMD group reported better physical health (54.6% in CAD vs. 69.7% in MMD) at baseline. By endline, both groups experienced a decline in physical health-related QoL (49.6% in the CAD group; 51.7% in the MMD group), but the CAD group demonstrated striking superiority in the DiD estimate for physical health-related QoL (11.6%, 95% CI: 6.6–16.5, Table 4), supported by robust intervention effects (AOR 1.70, 95% CI: 1.37–2.11, Table 3). Despite the MMD group’s superior baseline mental health-related QoL (CAD 76.3% vs. MMD 84.2%), CAD narrowed this gap at endline (CAD: 82.1% vs. MMD: 77.6%). No significant difference was observed regarding mental health-related QoL (AOR 1.20, 95% CI: 0.92–1.57, Table 3). Adjusted models consistently outperformed crude models, as reflected in lower Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values (Table 3), which reinforces the validity of the estimates. All outcomes met prespecified non-inferiority margins, with superiority established for ART adherence and mental health- and physical health-related QoL.

Sensitivity analyses

Table 5 shows that the CAD model maintained similar outcomes to MMD in all tested scenarios, with effect estimates remaining stable or strengthening under conservative assumptions. Under the missing-at-random assumption, the CAD model was associated with a 6.6% improvement in ART adherence (95% CI: 5.2–7.8). For mental health outcomes, the CAD model showed a 6.9 percentage-point advantage (95% CI: 5.5–8.5) in maintaining no depressive symptoms compared to the MMD model and clinically meaningful improvements in physical health-related QoL (11.9%, 95% CI: 10.6–13.3). The consistency between imputed and complete-case estimates underscores the legitimacy of the missing-at-random assumption in this context.

There was minimal impact on estimates when accounting for potential differential loss to follow-up by adjusting key sociodemographic variables by 50%. ART adherence remained robust at 6.4% (95% CI: 5.0–7.8), as did CAD’s advantage in sustaining no depressive symptoms (6.7 percentage points [pp], 95% CI: 5.2–8.3) and physical health-related QoL gains (11.6%, 95% CI: 10.1–13.1). Notably, mental health-related QoL scores increased slightly (3.9%, 95% CI: 2.5–5.2 vs. 3.5%, 95% CI: 2.2–4.9 in Scenario 1).

Under a conservative missing-not-at-random assumption, where the loss to follow-up systematically underperformed, CAD’s superiority persisted or even strengthened. ART adherence gains increased to 8.1% (95% CI: 6.7–9.6), while the advantage in maintaining no depressive symptoms rose to 8.3% (95% CI: 6.9–10.0), and physical health improvements remained stable at 11.9% (95% CI: 10.5–13.3). However, stigma-related outcomes exhibited differential patterns. Although the CAD model continued to improve non-stigma experiences (6.3%, 95% CI: 4.5–8.0, compared to 4.9%, 95% CI: 3.3–6.6 in Scenario 1), the lower bounds of the 95% CIs for internal stigma (−0.32) and fear of stigma (−0.66) did not exclude 0, indicating non-inferiority but a lack of superiority in these areas.

Bias-adjusted DiD estimates were consistently positive (6.71 pp, range 0.92–7.13 pp). A conservative stress test that lowered CAD specificity at endline attenuated the effect to 5.95 pp (Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the CAD model in maintaining ART adherence, improving mental health, and enhancing physical health outcomes compared to the MMD model over the 18-month intervention period. Retention in HIV care was high in both groups, with 98.2% of CAD participants and 97.6% of MMD participants retained at endline, indicating that the CAD model did not compromise care continuity with its decentralised and peer-led design. Viral suppression rates exceeded 99% in both arms, with marginal differences favouring the CAD model, underscoring the overall robustness of Cambodia’s HIV programme in sustaining virologic control across models.

While self-reported ART adherence declined over time in both groups, the decline was smaller in the CAD arm. Adjusted models confirmed significantly higher odds of ART adherence among CAD participants relative to MMD, consistent with existing literature supporting the role of community-based models in enhancing treatment engagement25,26. However, the absolute difference in ART adherence between arms was modest (86.8% vs. 84.4%) and must be interpreted within the context of high baseline adherence and likely ceiling effects. These results suggest that, while the CAD model may buffer against structural and psychosocial disruptions (e.g. stigma, migration), its additive impact on ART adherence may be constrained by already-strong performance in the control group.

In such high-performing systems, statistically significant differences should not be conflated with substantive clinical or programmatic gains. With large sample sizes, small effect sizes may reach statistical significance even when their practical impact is limited. In this case, the lower bound of the CI exceeding zero does indicate a consistent directional benefit. Yet, a 2.4 percentage-point advantage, though statistically significant, should be interpreted in relation to the system’s maturity, the model’s scalability, and its potential to prevent disengagement in harder-to-reach populations. The CAD model’s ability to sustain ART adherence under real-world implementation constraints, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, may reflect both effectiveness and operational resilience and alignment with Cambodia’s shift from access-based targets toward sustainable, person-centred HIV care in the post-90-90-90 era.

Beyond ART adherence, psychosocial outcomes showed patterns consistent with a protective effect on mental health in the CAD arm. While mental health improved modestly in the CAD arm and declined in the MMD arm, adjusted models indicated 54% higher odds of maintaining no depressive symptoms among CAD participants, with a significant DiD improvement of 6.8%. Notably, despite poorer baseline mental health in CAD, the disparity between groups narrowed by endline, suggesting a buffering effect of CAD on mental health inequities27. Given the non-random, opt-in design, we interpret these contrasts as associations rather than definitive causal effects. Physical health-related QoL outcomes also favoured the CAD model, showing clinically meaningful gains (DiD: +11.6%, 95% CI: 9.75–13.36). However, the impact of the CAD model on mental health-related QoL remained inconclusive. Because three prespecified outcomes met the superiority criterion, we controlled the family-wise error rate across these claims using the Holm–Bonferroni step-down procedure (α = 0.05); each remained significant after adjustment.

The CAD model showed promise in reducing externalised stigma, with non-stigma experiences improving in the CAD group but declining in the MMD group. However, internal stigma increased in both groups, and adjusted models did not confirm the CAD model’s superiority. While all stigma-related outcomes met non-inferiority thresholds, these results align with evidence that CAD models alone cannot address deeply internalised stigma without structural interventions28. Integrating peer-led education, community engagement, and policy reforms, guided by frameworks such as the Modified Socio-Ecological Model, could enhance the CAD model’s potential to mitigate stigma29.

To support policy-relevant interpretation, we prespecified validated threshold-based endpoints for stigma, depression, and quality of life, reporting the proportion of participants in favourable states. This approach reduces model dependence in high-performing cohorts, where score distributions are typically right-skewed with ceiling compression30,31,32, and aligns effect estimates with service targets expressed as absolute risks. We reported endline levels by arm alongside DiD contrasts that accounted for baseline imbalance and common time trends. Recognising that thresholding reduces within-scale granularity, we interpreted magnitudes cautiously and noted that complementary continuous analyses could be informative in future work.

To evaluate the robustness of our findings in the context of incomplete outcome data, we employed a structured sensitivity analysis framework using the Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) method, supplemented by exploratory nonparametric approaches. This framework encompassed three analytically distinct scenarios, each reflecting a different set of assumptions about the missing data mechanism, ranging from conventional missing at random (MAR) to more contextually grounded missing not at random (MNAR) conditions.

Scenario 1 assumed that observed covariates fully explained missingness, with participant characteristics remaining stable between baseline and endline. This represents the classical MAR assumption often used in applied analyses. Under this scenario, the CAD model demonstrated consistent improvements in ART adherence (6.6%, 95% CI: 5.22–7.81), the probability of maintaining no depressive symptoms (6.9%, 95% CI: 5.54–8.50), and physical health-related QoL scores (11.9%, 95% CI: 10.55–13.25). These estimates are closely aligned with those derived from complete-case analyses, reinforcing the internal consistency of findings under idealised assumptions. Scenario 2 retained the MAR framework but introduced potential deviations in participant characteristics among those lost to follow-up, simulating differential attrition by modifying covariates for 50% of individuals with incomplete data. Treatment effects remained directionally stable, with only marginal attenuation in magnitude, suggesting that moderate covariate drift over time was unlikely to introduce substantial bias into the observed effects.

Given that MAR is a strong and untestable assumption, particularly in real-world HIV programmes where loss to follow-up is often associated with unmeasured declines in health or psychosocial well-being, we further evaluated an MNAR scenario (Scenario 3). In this case, outcome probabilities were systematically reduced by 5% among participants with missing endline data, reflecting a plausible mechanism wherein individuals with poorer outcomes are more likely to disengage from care. The persistence—and in some cases amplification—of CAD’s estimated benefits under this assumption provides strong support for the robustness of intervention effects to outcome-dependent attrition.

To complement these parametric approaches, we also explored missForest, a nonparametric, machine learning-based imputation algorithm that does not rely on explicit distributional assumptions. While point estimates were directionally consistent, the associated CIs were considerably wider and less stable, likely due to greater estimator variance and the algorithm’s incompatibility with model-based estimators such as DiD. For these reasons, and in alignment with Rubin’s rules for inference, MICE was retained as the primary approach for handling missing data.

The convergence of estimates across complete-case, MAR, and MNAR scenarios, combined with directional consistency under a nonparametric framework, enhances the credibility of the findings. Although the actual mechanism of missingness remains unverifiable, this triangulated analytical strategy strengthens the internal validity of the reported intervention effects. It mitigates concerns that the observed benefits of CAD are attributable to systematic biases arising from differential loss to follow-up.

Our study has several notable strengths. It is the first of its kind in Cambodia and the region, providing critical insights into community-based interventions for stable people living with HIV. With approximately 2000 participants per arm and coverage of 20 ART clinics across both rural and urban areas, the study achieved strong statistical power and broad representativeness. These features make the findings directly relevant to national health policy and to improvements in HIV care delivery. Internal validity was strengthened through multiple sensitivity analyses, which demonstrated that the results were robust to plausible mechanisms of missing data. Situated within the DSD literature, our findings extend evidence from adherence clubs—voluntary, group-based refill models that have shown high retention and viral suppression among stable clients33,34,35,36. Unlike club models, the CAD approach guaranteed monthly scheduled contact, actively traced absentees, and integrated peer psychoeducation with outreach for non-attendees. Despite COVID-19 service disruptions, CAD sustained near-universal virologic control and conferred advantages on selected psychosocial outcomes. These results broaden person-centred DSD options and align with international guidance emphasising flexible, context-appropriate models for people living with HIV37,38.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the quasi-experimental design, while pragmatic and policy-relevant, lacked the protection against confounding that randomisation affords. Clinics were matched on observable features; however, unmeasured differences, such as leadership, staffing, or local engagement, may still have influenced outcomes. We applied covariate adjustment and DiD estimation to mitigate this risk, acknowledging the methodological challenges of interpreting interaction terms and ensuring valid inference in nonlinear DiD models39,40,41, but the absence of a midline assessment prevented empirical validation of the parallel-trends assumption.

Second, allocation was non-random, and CAD enrolment was voluntary. DiD cannot remove time-varying, unmeasured differences, such as motivation, readiness to switch, or caregiver support, that may influence trajectories independently of the intervention. These issues are most salient for psychosocial outcomes, which are particularly vulnerable to selection and reporting biases. Monthly peer contact in CAD may also have influenced self-report, creating arm-differential measurement error that is not fully addressable by DiD. Furthermore, as social support was not prespecified as a primary or secondary analytic endpoint, the findings are reported descriptively to contextualise the model’s social-support mechanism rather than as a directly measured outcome, and no causal inferences are drawn. For this reason, we interpret psychosocial findings as adjusted associations compatible with a buffering effect of CAD, rather than definitive causal estimates. Randomised or stepped-wedge designs may be preferable for future evaluations.

Third, delivery fidelity was monitored through agendas, CAW reports, supervisory checklists, and follow-up for absentees, but session-level attendance was not aggregated as a prespecified outcome and thus could not be included in the impact analysis. Moreover, CAWs operated as a project-supported rather than a civil-service cadre, so workforce absorption cannot be inferred from this study. Any institutionalisation of CAD will require separate decisions from Cambodia’s Ministry of Health on policy and financing.

Fourth, retention in care was defined as being in treatment at 18 months, as documented in routine clinic records. While aligned with programme practice, this binary measure may overestimate retention compared to more stringent definitions (e.g. two visits at least 90 days apart within a year)42. Transient care interruptions were not captured, potentially obscuring patterns relevant for intervention design. Furthermore, viral load monitoring was performed through routine 6-monthly testing, which was not harmonised with the study time points. While this enhances external validity, it reduces attribution precision. We retained the programmatic <1000 copies/mL threshold per WHO and national guidance. Given that >90% of participants were recorded as ‘virologically undetected’ (<40 copies/mL) and only a small fraction fell between 50–1000 copies/mL, alternative cut-offs would have yielded sparse categories without materially affecting inference.

Fifth, ART adherence was measured by self-report, vulnerable to recall and social-desirability bias, and potentially influenced by CAD’s monthly peer contact. To mitigate this, data were collected privately by independent staff with neutral scripts, and operational checks (pill counts, refill logs) were used within CAD to prompt follow-up when discrepancies arose. These operational data, however, were unsuitable as analytic endpoints due to unsynchronised refill cycles. We therefore interpreted adherence cautiously, triangulating with objective programme measures (viral suppression and retention), which were uniformly high. Quantitative bias analysis indicated that plausible reporting bias would not reverse the observed effects; however, the magnitudes should be viewed as bounded rather than point-identified.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic curtailed the intervention from 24 to 18 months, eliminating the planned midline and weakening the internal validity of the DiD. Both arms experienced disruptions in access, ARV distribution, clinic consultations, and staffing, which contributed to declines in adherence, mental health, and stigma. CAD was adapted to these conditions with individualised and telehealth-based delivery, which may have attenuated community-building effects. Nevertheless, outcomes in CAD participants remained more stable than in MMD, particularly for mental health and stigma, consistent with a buffering effect. In Cambodia, where HIV-related stigma remains entrenched, this relative protection may be of particular significance.

These findings underscore the distinct added value of the CAD model, which extends beyond decentralised ART delivery to actively cultivate psychosocial resilience through peer-led engagement. Unlike facility-based or other differentiated care approaches, the CAD model embeds people living with HIV at the centre of service delivery, fostering mutual trust, psychological safety, and emotional solidarity within the community. By creating a stigma-free environment for ARV distribution, the model facilitates meaningful peer connections and leadership, reinforcing identity, agency, and social reintegration. The structured roles and supportive peer networks likely enhanced participants’ sense of belonging and purpose, protective factors known to buffer against the adverse mental health impacts of chronic illness and systemic disruption. These findings suggest that CAD offers a scalable, context-appropriate solution to address both clinical and psychosocial dimensions of HIV care, particularly in settings vulnerable to future public health shocks. This buffering effect—evident in CAD’s more stable mental health and stigma-related outcomes despite pandemic disruptions—highlights its potential to foster community resilience in ways that conventional service delivery cannot.

Building on these strengths, this study shows that the CAD model is a promising strategy for improving ART adherence, mental health, and physical health outcomes among stable people living with HIV in Cambodia. With a 5.5% advantage in ART adherence and an 11.6% improvement in physical health-related QoL compared to MMD, CAD’s benefits align with global evidence on the value of community-based HIV programmes in optimising care resilience. High retention rates in HIV care (98.2%) and viral suppression rates (>99%) in both arms confirm the robustness of Cambodia’s HIV care system. Still, CAD’s superior capacity to sustain ART adherence, promote mental health, and reduce stigma positions it as a holistic, patient-centred alternative to clinic-based MMD. For policymakers, scaling up CAD in Cambodia and similar settings is warranted, particularly given its adaptability to telehealth and minimal implementation barriers during the COVID-19 pandemic. To maximise impact, however, scale-up efforts should integrate targeted stigma-reduction and mental health interventions to address persistent internalised stigma and improve the quality of life of people living with HIV.

Future research should address the limitations and refine the implementation of CAD to enhance its effectiveness. First, extending follow-up under non-pandemic conditions would clarify CAD’s long-term effectiveness and capture potential declines in retention, using continuous metrics (e.g. treatment gaps, visit frequency) consistent with established guidelines43. Second, mixed-methods approaches that integrate qualitative evaluations are needed to examine contextual barriers, such as migration, telehealth access, and stigma, in resource-limited settings. Concurrently, health system assessments should evaluate scalability, including its effects on the workload of healthcare providers. A cost-effectiveness analysis will inform decisions on scale-up. Third, adapting CAD to integrate targeted mental health and stigma-reduction components could enhance its holistic impact. Replication studies across diverse health system contexts (e.g. decentralised vs centralised) are also needed to test generalisability. Finally, findings from these efforts should guide the development of evidence-based guidelines for community-based HIV care, ensuring alignment with pandemic-resilient strategies and global best practices44.

Methods

Study design

This quasi-experimental study was conducted between November 2021 and April 2023 in 10 provinces with high HIV burden. Within these provinces, 10 ART clinics were purposefully selected to implement the CAD intervention, each matched with a control site that implemented the standard MMD model. Site selection was guided by programmatic feasibility and comparability in routine service delivery.

Sites were selected through consultation with the Database Management officers of NCHADS and other stakeholders involved in the national HIV programmes. The matching process considered three primary criteria: (1) sufficient numbers of stable people living with HIV, particularly those residing in geographically dispersed areas; (2) clinic accessibility and operational readiness to implement CAD; and (3) contextual similarity across arms, including urban/rural location, clinic infrastructure, and catchment population size. Site proposals were validated through stakeholder meetings and field visits. The CAD group included six urban clinics and four rural sites across Phnom Penh, Kampong Thom, Kampot, Koh Kong, and Takeo. The MMD group included seven urban and three rural sites in Phnom Penh, Kampong Cham, Pailin, Preah Sihanouk, Siem Reap, and Prey Veng. The study protocol details have been published elsewhere16.

In the CAD arm, 82 CAWs were recruited and trained to lead monthly group-based community ART delivery. Groups were formed by clinic catchment area and neighbourhood proximity and often built on existing peer networks supported by implementing NGOs. Participants could indicate preferences for membership. Once established, groups were closed to preserve continuity, and members who withdrew or transferred were not replaced. CAWs were selected for their proximity to the clinic and typically resided in the same communities as participants, thereby enhancing access and trust. Each CAW was assigned one group of approximately 20 to 30 members and remained with that group throughout the 18-month intervention. Sessions were convened monthly and typically lasted about 2 h at a consistent venue, such as the CAW’s home or a private community space. When required, programme staff provided temporary coverage to ensure continuity. Attendance was primarily limited to enroled participants; caregivers, family members, or programme staff occasionally joined to provide support, particularly when sessions were hosted at home. CAWs were engaged as a project-supported community cadre contracted via the implementing partner for part-time engagement and received a standardised stipend.

CAWs completed a 2-day initial training programme, combining a core induction and a field practicum. The curriculum, delivered by NCHADS trainers and implementing-partner staff with input from ART clinic personnel, covered ART dispensing and storage, vital-sign assessment and documentation, referral mechanisms, group facilitation, adherence counselling, and psychosocial domains, including stigma, mental health, and sexual and reproductive health. The training integrated didactic sessions, role-plays, interactive discussions, and supervised fieldwork to build practical competency. The practicum confirmed readiness prior to deployment. CAWs subsequently received structured support comprising monthly operational coaching by implementing-partner field officers, quarterly clinical supervision by ART-clinic personnel, and periodic mentoring by NCHADS delivered in person or remotely. Given this embedded supervision and continuous performance monitoring, formal post-training certification and refresher courses were not required during the study period.

Each session followed a standard agenda, including registration, a basic health screening such as blood pressure and temperature taking, group treatment adherence counselling, ART refills when due, peer-led health education, and ART adherence monitoring through pill counts. Education modules addressed ART adherence, HIV and opportunistic infections, COVID-19 prevention, reproductive health, mental well-being, hygiene, and community financial self-help. Fidelity was maintained through the use of structured tools, routine documentation, and multi-level supervision. CAWs submitted monthly reports via the project database, capturing attendance, dispensing, pill counts, vital-sign assessments, and referrals. Supervisors reviewed submissions using a standard checklist assessing completeness, timeliness, and follow-through on referrals. Session delivery was supported by treatment record books and standard guides containing scripts, checklists, and referral forms. When participants were unable to attend, CAWs conducted individual follow-ups and delivered ART at home to prevent treatment interruptions. Process indicators were routinely communicated to ART clinics through established reporting channels to ensure alignment with national service-delivery protocols. Pill counts and refill logs were used operationally to verify recall and to prompt counselling or home follow-up when discrepancies were observed. Because refill cycles were not synchronised across participants, these operational data were not analysed as endpoints.

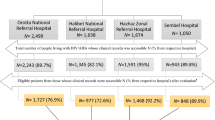

In the MMD arm, participants collected and refilled their ARV prescriptions at the ART clinics every three to 6 months. People living with HIV in both arms visited ART clinics as needed for consultations and routine clinical check-ups every 6 months. Clinical management was conducted by trained personnel at ART clinics, in accordance with national guidelines and protocols. A schematic comparison of the CAD and MMD care pathways is presented in Fig. 2.

Community engagement and co-creation

The CAD model was developed and implemented with the active involvement of people living with HIV who served as CAWs, drawing on their lived experiences to ensure the intervention’s relevance and effectiveness. CAWs played a vital role in site selection, intervention design, and implementation through a stakeholder participatory approach, ensuring that the model addressed community needs and aligned with national priorities. Furthermore, CAWs directly applied their personal experiences to enhance the delivery of the intervention. This involvement of individuals with lived experiences was crucial in fostering trust, reducing stigma, and tailoring the intervention to the realities faced by people living with HIV in Cambodia. Additional details on collaboration, stakeholder engagement, and capacity-building efforts are presented in the Inclusion and Ethics Statement.

Participants

People living with HIV were eligible for inclusion based on the following criteria: (1) aged 15 or older, (2) on first-line ART for at least 1 year, (3) not reporting ART-related adverse reactions or drug interactions requiring regular monitoring, (4) free from tuberculosis and other opportunistic infections at the time of baseline assessment, (5) not receiving prophylactic treatment, (6) having at least two consecutive undetectable viral loads or CD4 counts above 200 cells/mm3, and (7) assessed by their healthcare providers as having a solid understanding of lifelong treatment and medication adherence. Pregnant or breastfeeding women were excluded from the study.

All participants in the control arm were enroled from clinics already implementing the MMD model, which continued standard operations throughout the study. In the intervention arm, eligible clients receiving either MMD or standard monthly ART care were offered CAD; those who declined remained in their existing modality. Participants who had previously received MMD services had been on that model for at least 2 years before the study’s initiation. Those transitioning from standard monthly care were required to meet the same eligibility criteria, ensuring that all participants were clinically stable at enrolment. Recruitment in both arms followed a census-based approach at each of the 20 participating ART clinics. Allocation to study arms was non-random, and CAD enrolment was voluntary for eligible clients.

The published study protocol details the sample size, power assumptions, and design parameters and is included in the Supplementary16. The final analytic sample comprised 2040 participants in the CAD arm and 2049 in the MMD, achieving the target required for evaluating meaningful differences in primary outcomes under pragmatic implementation conditions.

Data collection procedures

Quantitative data were collected at baseline in October 2021, prior to the introduction of the CAD intervention in November, and at the endline in April 2023, following the completion of the 18-month intervention. The questionnaire included sociodemographic and self-reported medical history, including comorbidities. Sex and gender data were self-reported and included options for male, female, and LGBTQ+ identities. Viral loads and CD4 counts were captured from the clinics’ medical records.

A total of 27 trained personnel were involved in data collection, comprising 24 field data collectors and three field supervisors. All individuals were selected based on prior experience in HIV-related research and expertise in public health, social science, or healthcare data collection. To ensure neutrality, these data collectors operated independently of the CAD intervention team and had no affiliation with CAWs delivering the intervention. Interviews were conducted in private settings using standardised, neutral scripts. Individual survey responses were kept confidential and not shared with CAWs or clinic staff; they had no influence on CAD eligibility or continued participation. CAWs, caregivers, and family members were not involved in the interviews. The same team was deployed across both CAD and MMD arms, following a site-by-site approach to ensure consistency and minimise inter-arm bias.

Data collectors participated in a comprehensive 3-day training workshop before each data collection wave. The workshops were led by the Principal Investigator (S.Y.) and co-investigators from Khmer HIV/AIDS NGO Alliance (KHANA) and NCHADS. Training sessions covered key topics including the HIV care cascade, data collection protocols, ethical considerations, confidentiality, and quality assurance. Gender matching between data collectors and participants was also considered to facilitate comfort during interviews. Responsibilities of data collectors included mapping data collection procedures at each site, contacting CAWs (in the CAD arm) to schedule participant interviews, conducting face-to-face interviews with selected people living with HIV, safeguarding participant confidentiality, recording responses accurately, ensuring data quality through real-time validation and quality control checks, documenting field team progress, reporting operational challenges or protocol deviations, and maintaining the security of KHANA equipment and their safety. Supervisors monitored adherence to protocol and addressed any emergent field issues.

Outcome variables

The primary outcomes assessed included (i) retention in HIV care, (ii) viral load suppression, and (iii) ART adherence. Retention in HIV care was defined as whether people living with HIV were documented in clinical records as actively receiving ART at the 18-month follow-up. Viral load suppression was defined as achieving a viral load of fewer than 1000 RNA copies/mL in the most recent measurement during the study period, as documented in clinical records. ART adherence was defined as a binary outcome based on self-reported responses to five questions assessing medication practices over the prior 2 months: missed any ARV doses in the past 2 months, had trouble remembering to take ARVs, stopped taking ARVs when feeling better, missed ARV doses in the past 4 days, and stopped taking ARVs when feeling worse. Participants were classified as adherent only if they answered ‘no’ to all five questions, prioritising specificity over sensitivity. This method reduces the risk of misclassifying non-adherent individuals as adherent. While pill counts or pharmacy refill data were considered, they were deemed unreliable due to inconsistencies in participants’ pill quantities during surveys (e.g. some had recently collected ARVs, while others were due for refills).

Secondary outcomes included (i) HIV-related stigma, (ii) mental health, and (iii) quality of life. We prespecified dichotomous endpoints reflecting favourable states, defined using validated thresholds for each instrument. Dichotomisation was selected to provide programme-relevant, directly interpretable proportions and to minimise sensitivity to skewness and ceiling effects.

HIV-related stigma was assessed in three dimensions, which included experienced stigma, internal stigma, and fear of stigma, using the People Living with HIV Stigma Index, which was validated for people living with HIV in Cambodia45,46. Experienced stigma was defined as having experienced exclusion, harassment, or adverse events across social, familial, or institutional settings, with a composite score of less than 3 indicating the absence of experienced stigma. Internal stigma reflected negative self-perceptions, with a score of less than 5 indicating low internal stigma. Fear of stigma captured concerns about rejection or discrimination, with a score of less than 2 indicating no fear of stigma. Composite scores were generated by summing binary variables. Thresholds were prespecified based on the Cambodia validation, corresponding to the ‘none/low’ categories for each domain, to ensure construct fidelity and facilitate direct interpretability for programme decision-making.

Mental health was assessed using the 10-item Centre for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10), with scores below 10 indicating no depressive symptoms31. This cut-point follows instrument guidance and regional validation studies to maximise specificity for the absence of clinically meaningful depressive symptoms. QoL was measured using the Short-Form 12 (SF-12) survey, which included 12 items across eight health domains: physical function, social function, role limitations due to physical health, role limitations due to emotional problems, mental health, vitality, bodily pain, and general health47. Responses were scored with the instrument’s published factor weights to derive Physical (PCS) and Mental (MCS) Component Summary scores, then transformed to norm-based T-scores (mean 50, SD 10; higher values indicate better health). In accordance with the prespecified analysis plan and established SF-12 conventions, we applied validated thresholds to create clinically interpretable positive-state endpoints (PCS ≥ 50; MCS ≥ 42). The CES-D scale and the SF-12 have been widely used in various Asian populations, including those in Cambodia, India, Japan, and Singapore48,49,50,51.

Covariate selection

Candidate covariates were identified a priori through a structured, consultative process informed by Cambodia’s national HIV programme priorities, the Boosted Integrated Active Case Management framework, and a synthesis of empirical evidence from the HIV implementation science literature. KHANA led this process in collaboration with representatives of people living with HIV, civil society partners, and technical advisory groups. Covariates reflecting sociodemographic, clinical, and structural domains were selected based on their theoretical salience and contextual relevance to HIV-related outcomes. These variables were consistently applied across all primary and secondary models to adjust for potential confounding. Covariate inclusion was evaluated via the change-in-estimate approach described in the ‘Statistical analysis’ section.

Statistical analyses

To estimate the impact of the CAD model, this study employed a DiD analytical framework to assess changes in clinical and psychosocial outcomes between intervention and control groups over two time points. This quasi-experimental method is well-suited for non-randomised evaluations, as it controls for unobserved time-invariant confounding by differencing out baseline group differences and secular time trends. The DiD effect was derived from the interaction term between treatment group and time (baseline vs. endline) within a logistic regression model, adjusting for relevant covariates. The estimator can be expressed as:

Y denotes the predicted probability of the outcome.

Complete case analyses were done for participants who were retained in HIV care and completed baseline and endline surveys. Descriptive analyses summarised the sociodemographic characteristics of participants. The Pearson’s Chi-square test assessed differences between ordinal data, while the Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables when the normality assumption was met; otherwise, the Mann–Whitney U-test was applied. Variables were categorised pragmatically to account for low cell counts.

The effects of the intervention on treatment outcomes were modelled using logistic regression with robust standard errors to account for potential heteroskedasticity. A structured covariate selection strategy minimised bias and improved model precision. This process consisted of four stages: evaluating potential confounders using the change-in-estimate criterion, constructing an initial adjusted model, refining the model through backward elimination guided by the BIC, and validating the final specification via nonparametric bootstrapping.

Each candidate covariate was assessed individually for its potential confounding effect. This entailed comparing a crude model, comprising treatment, time, and their interaction, with an adjusted model that included the covariate of interest. The influence of the covariate was quantified as the percentage change in the treatment coefficient:

Covariates that resulted in a change exceeding 10% were considered confounders and retained in subsequent adjusted models. This criterion was applied separately at baseline and endline to account for potential differences in confounding structure over time. At baseline, the impact of each covariate on the main effect of treatment (i.e. the cross-sectional comparison between CAD and MMD arms before intervention exposure) was evaluated. At endline, the covariate’s influence was assessed on the combined effect of treatment and its interaction with the timeline variable, as this interaction term captures the differential change over time between groups and forms the basis of the DiD estimate. This approach ensured that only covariates with a meaningful influence on the estimated intervention effects were included in the final models, thereby enhancing the validity of causal inference in the absence of randomisation.

Once potential confounders were identified, an adjusted logistic regression model was estimated. This model included all significant confounders identified in the previous step, as well as essential demographic variables (i.e. age and gender), regardless of their potential impact on the treatment effect. The inclusion of age and gender was necessary due to their fundamental roles in influencing health outcomes and their ability to enhance model interpretability and generalisability. This step ensured that the treatment effect estimates were not biased by minimising variable confounding, providing a more accurate representation of the intervention’s impact.

To further refine the model and achieve parsimony, backward selection using BIC was performed. The BIC prioritises simpler models while ensuring adequate fit to the data. The procedure began with the fully adjusted model and iteratively removed covariates based on their statistical significance. Covariates with the highest P values not part of the primary treatment effect were excluded first. For categorical covariates, the overall significance was assessed using the Wald test. A covariate was retained if its P value was below 0.05 or if its removal caused a change of more than 10% in the treatment effect, indicating its potential role as a confounder. The process continued until only statistically significant or theoretically justified covariates remained, ensuring that the model was both parsimonious and robust.

Once the final covariates were selected, the logistic regression models were specified for each treatment outcome. Predicted probabilities were computed using the margins command to estimate the DiD effect. Nonparametric bootstrapping with 500 replications was employed to estimate percentile-based 95% CIs, improving the precision and empirical reliability of the DiD estimates. Bootstrapping involved repeatedly resampling from the dataset, fitting the logistic regression model each time, and calculating the DiD estimate for each sample. The distribution of these estimates provided CIs, which were used to assess the non-inferiority and superiority of the intervention, ensuring the observed treatment effects were not driven by sample variability.

A prespecified non-inferiority margin of −10% was applied to assess whether the CAD model was not unacceptably worse than MMD across all evaluated outcomes. This margin was selected based on clinical judgement, prior evidence from HIV care studies, assumptions outlined in the study protocol, and the programmatic tolerance for modest differences in effectiveness16,52. Given its potential implementation advantages, it reflects the maximum acceptable difference at which the CAD model would still be considered a viable alternative. Statistical evaluation of non-inferiority was based on the 95% CI of the DiD estimate. Non-inferiority was concluded if the lower bound of the CI exceeded −10%, indicating that the observed difference remained within the predefined acceptable range. Superiority was concluded if the lower bound exceeded 0%, demonstrating statistically significant advantages of CAD over MMD.

ART adherence was measured by self-report, which is susceptible to recall and social-desirability bias that may differ by study arm. We therefore implemented a quantitative bias analysis (QBA) to assess differential misclassification53,54. Observed adherence proportions were corrected using the Rogan–Gladen estimator55,\({\,\left(3\right)p}_{{{\mathrm{bias}}}-{{\mathrm{adjusted}}}}=({p}_{{{\mathrm{observed}}}}+{{\mathrm{Sp}}}-1)/({{\mathrm{Se}}}+{{\mathrm{Sp}}}-1)\), truncated to [0,1] with the constraint Se + Sp > 1. Scenario-specific values of sensitivity (Se) and specificity (Sp) were prespecified for the Rogan–Gladen correction; the resulting quantities are deterministic bounds under these assumptions and are therefore reported without p values or 95% CIs.

Guided by empirical evidence that self-report tends to overestimate adherence and acknowledging that monthly peer contact in CAD could plausibly increase social-desirability bias relative to MMD, we prespecified sensitivity ranges from 0.75 to 0.95 and arm-specific specificity ranges (CAD: 0.60–0.90; MMD: 0.80–0.95). We also implemented a conservative stress test that reduced CAD specificity at endline while holding MMD parameters constant56,57,58,59. For each scenario, we recalculated bias-adjusted adherence by arm and time and derived the DiD on the risk-difference scale using model-based marginal probabilities as previously described.

To rigorously address missing data due to loss to follow-up, multiple imputation was conducted using the MICE method to prepare data for DiD analysis. The primary analyses assumed data were MAR, where missing treatment outcomes were imputed via logistic regression imputation, incorporating outcome-specific covariates. To ensure robustness, 10 imputed datasets were generated. Three sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the potential impact of different missing data mechanisms: (1) Scenario 1 (MAR, primary analysis), where missing outcomes were imputed based on observed covariates without altering baseline characteristics60; (2) Scenario 2 (differential missingness in covariates), where the baseline characteristics of 50% of the loss to follow-up individuals were systematically modified before outcome imputation to account for potential differential attrition, adjusting covariates plausibly affected by the intervention; and (3) Scenario 3 (MNAR adjustment), where missing outcomes were first imputed under MAR assumption and subsequently adjusted to account for unobserved confounding by reducing the predicted probabilities of loss to follow-up individuals by 5%, followed by restimulating their outcomes using a Bernoulli distribution, thereby modelling a scenario in which loss to follow-up individuals systematically exhibited lower probabilities in outcomes. In each scenario, the DiD estimate was derived from a logistic regression model that incorporated an interaction term between treatment and timeline, with the final estimates pooled using Rubin’s rules. Nonparametric bootstrapping (500 replications) was applied to quantify uncertainty, computing 95% CIs using the percentile method.

Data analyses were conducted using STATA 18 software61 and R Studio (version 2024.04.1 + 748), employing the MICE and boot packages62.

Safety and adverse events

An independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board periodically reviewed the study’s progress and safety in consultation with the CAD Project Steering Committee. Interim analyses were conducted to assess the potential benefits and harms associated with the study’s outcomes. Any adverse events were immediately reported to the study principal investigators, site co-principal investigators, and NCHADS. The CAD Project Steering Committee held ad-hoc meetings to review and address these events as necessary.

Study registration and protocol deviations

The quasi-experimental study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04766710) on 23 February 2021, and the first participant was enroled on 1 April 2021. The ClinicalTrials.gov registration record was prepared before enroling participants, in compliance with the National Institutes of Health policy on clinical trial registration. While the study was registered for transparency, it is not a randomised controlled trial in the traditional sense; the registration aimed to ensure adherence to ethical standards and transparency in reporting.

The study faced significant protocol deviations due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Initially planned for 24 months, the CAD intervention was shortened to 18 months due to project start-up delays and social restrictions that disrupted its implementation. These unforeseen challenges affected the study timeline, resource availability, and operational capacity, preventing the completion of key assessments. As a result, the midterm quantitative survey and the endline qualitative process evaluation could not be conducted, limiting the depth of insights into participant experiences and the effectiveness of the intervention. While adaptations were made, these deviations must be taken into account when interpreting the study’s findings and conclusions.

Inclusion and ethics statement

The CAD project is a collaboration between the National University of Singapore, KHANA, and NCHADS, building on over a decade of partnership. KHANA, a key player in Cambodia’s HIV response since 1996, and NCHADS, which leads the national HIV programme, developed a standard operating procedure for the CAD model, endorsed by the Ministry of Health. The project was designed using a stakeholder participatory approach, involving HIV communities, key populations, NGOs, government agencies, and development partners in the selection of sites, the design of interventions, and their implementation. KHANA, NCHADS, and three community-based NGOs, along with representatives of people living with HIV, led the development of the intervention, guided by formative studies and national HIV programme evaluations. Regular stakeholder workshops, project advisory board meetings, and consultations with the National HIV Technical Working Group ensured the intervention was relevant, sustainable, and aligned with national priorities. Clear roles and responsibilities were established before the study, with the study PI and local PIs serving as co-leaders in all decisions. The project also prioritised capacity building, providing staff training, continuing education, and advanced scholarly training to strengthen local expertise and ensure the long-term sustainability of the CAD model within Cambodia’s HIV response framework.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the National Ethics Committee for Health Research (Ref. 258/NECHR) of Cambodia’s Ministry of Health. All participants, including people living with HIV, CAWs, and healthcare workers, provided written informed consent before data collection. Privacy and confidentiality were strictly upheld, with all personal identifiers removed to ensure anonymity. Given the inclusion of sensitive questions related to stigma, mental health, and psychosocial well-being, trained data collectors employed trauma-informed, non-judgmental interviewing techniques. They were instructed to refer participants to appropriate support services in cases of distress. Interviews were conducted in private settings to ensure participant comfort and psychological safety. Participation was entirely voluntary, and participants were free to decline or withdraw from the study at any stage without penalty. In recognition of their time and travel, all participants received transport compensation of USD 5 to participate in baseline and endline surveys. Additionally, during routine clinical follow-ups, NCHADS provided transportation stipends ranging from USD 5 to USD 15, based on the travel distance. These safeguards aimed to minimise risk, uphold ethical standards, and ensure respectful and equitable engagement with all study participants.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

De-identified participant-level data are publicly available on Code Ocean under accession number 10.24433/CO.1562099.v1 (complete-case analysis capsule) and mirrored for reproducibility under 10.24433/CO.6352452.v1 (sensitivity-analysis capsule). The raw identifying data are protected and not publicly available due to data privacy and ethical restrictions governed by the National Ethics Committee for Health Research, Cambodia.

Code availability

All analysis code and the full computational environment are available in Code Ocean at the same DOIs above.

References

National Center for HIV/AIDS. D.a.S. Strategic Plan for HIV/ AIDS and STI Prevention and Control in the Health Sector 2016–2020 (National Center for HIV/AIDS, 2016).

National AIDS Authority. The Fifth National Strategic Plan for a Comprehensive, Multi-Sectoral Response to HIV/AIDS (2019–2023) (National AIDS Authority, 2019).

Global AIDS Monitoring. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (2022).

National Center for HIV/AIDS. D.a.S. Summary Quarterly Report on HIV-AIDS and HCV-HIV Co-infection (National Center for HIV/AIDS, 2019).

Yi, S. et al. AIDS-related stigma and mental disorders among people living with HIV: a cross-sectional study in Cambodia. PLoS ONE 10, e0121461 (2015).

Sweeney, S. M. & Vanable, P. A. The association of HIV-related stigma to HIV medication adherence: a systematic review and synthesis of the literature. AIDS Behav. 20, 29–50 (2016).

Katz, I. T. et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 16, 18640 (2013).

Kane, J. C. et al. A scoping review of health-related stigma outcomes for high-burden diseases in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med. 17, 17 (2019).

IN DANGER: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (2022).

Frijters, E. M. et al. Risk factors for loss to follow-up from antiretroviral therapy programmes in low-income and middle-income countries. AIDS 34, 1261–1288 (2020).

Angkor Research. Diffirentiated Model of Care: Survey of ART Staff Perceptions About Multi-month Dispencing (MMD) (Angkor Research, 2020).

World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on Person-centred HIV Strategic Information: Strengthening Routine Data for Impact. Policy Brief on Integrating and Strengthening Monitoring of Differentiated ART Service Delivery (World Health Organization, 2023).

Decroo, T. et al. Effect of Community ART Groups on retention-in-care among patients on ART in Tete Province, Mozambique: a cohort study. BMJ Open 7, e016800 (2017).

Faturiyele, I. O. et al. Outcomes of community-based differentiated models of multi-month dispensing of antiretroviral medication among stable HIV-infected patients in Lesotho: a cluster randomised non-inferiority trial protocol. BMC Public Health 18, 1069 (2018).

National Center for HIV/AIDS. D.a.S. Standard Operating Procedure on Appointment-spacing and Multi-Month Dispensing (MMD) in Cambodia (National Center for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology and STD, 2020).

Tuot, S. et al. Community-based model for the delivery of antiretroviral therapy in Cambodia: a quasi-experimental study protocol. BMC Infect. Dis. 21, 1–9 (2021).

Chang, L. W. et al. Impact of a community health worker HIV treatment and prevention intervention in an HIV hotspot fishing community in Rakai, Uganda (mLAKE): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 18, 494 (2017).

Ferrand, R. A. et al. The effect of community-based support for caregivers on the risk of virological failure in children and adolescents with HIV in Harare, Zimbabwe (ZENITH): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 1, 175–183 (2017).

Bandura, A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. in Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. xiii, 617-xiii, 617 (Prentice-Hall, Inc, 1986).

Cohen, S. & Wills, T. A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310 (1985).

Wilkinson, L. et al. Expansion of the Adherence Club model for stable antiretroviral therapy patients in the Cape Metro, South Africa 2011-2015. Trop. Med. Int. Health 21, 743–749 (2016).

Grimsrud, A., Sharp, J., Kalombo, C., Bekker, L. G. & Myer, L. Implementation of community-based adherence clubs for stable antiretroviral therapy patients in Cape Town, South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 18, 19984 (2015).

National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. Standard Operating Procedures: Adherence Guidelines for HIV, TB and NCDs. (2020).

World Health Organisation. Updated Recommendations on Service Delivery for the Treatment and Care of People Living with HIV (World Health Organisation, 2021).

Eshun-Wilson, I. et al. Effects of community-based antiretroviral therapy initiation models on HIV treatment outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 18, e1003646 (2021).

Wouters, E., Van Damme, W., van Rensburg, D., Masquillier, C. & Meulemans, H. Impact of community-based support services on antiretroviral treatment programme delivery and outcomes in resource-limited countries: a synthetic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 12, 194 (2012).

Wu, L. & Li, X. Community-based HIV/AIDS interventions to promote psychosocial well-being among people living with HIV/AIDS: a literature review. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 1, 31–46 (2013).

Kimera, E., Alanyo, L. G., Pauline, I., Andinda, M. & Mirembe, E. M. Community-based interventions against HIV-related stigma: a systematic review of evidence in Sub-Saharan Africa. Syst. Rev. 14, 8 (2025).

Baral, S., Logie, C. H., Grosso, A., Wirtz, A. L. & Beyrer, C. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health 13, 482 (2013).

Ware, J., Ma, K., Tuner-bowker, D. & Gandek, B. Version 2 of the SF12 health survey. (2002).

Radloff, L. S. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401 (1977).

People Living with HIV Stigma Index: User Guide. (International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF); Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+); International Community of Women Living with HIV (ICW), 2009).

Tsondai, P. R. et al. High rates of retention and viral suppression in the scale-up of antiretroviral therapy adherence clubs in Cape Town, South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 20, 21649 (2017).

Flämig, K., Decroo, T., van den Borne, B. & van de Pas, R. ART adherence clubs in the Western Cape of South Africa: what does the sustainability framework tell us? A scoping literature review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 22, e25235 (2019).

Limbada, M., Zijlstra, G., Macleod, D., Ayles, H. & Fidler, S. A systematic review of the effectiveness of non- health facility based care delivery of antiretroviral therapy for people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa measured by viral suppression, mortality and retention on ART. BMC Public Health 21, 1110 (2021).

Hanrahan, C. F. et al. The impact of community- versus clinic-based adherence clubs on loss from care and viral suppression for antiretroviral therapy patients: Findings from a pragmatic randomized controlled trial in South Africa. PLoS Med. 16, e1002808 (2019).

Updated recommendations on service delivery for the treatment and care of people living with HIV. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570385/ (World Health Organisation, 2021).

International AIDS Society. Differentiated CAre for HIV: A Decision Framework for Antiretroviral Therapy Delivery (International AIDS Society, 2016).

Puhani, P. A. The treatment effect, the cross difference, and the interaction term in nonlinear “difference-in-differences” models. Econ. Lett. 115, 85–87 (2012). volpages.

Karaca-Mandic, P., Norton, E. C. & Dowd, B. Interaction terms in nonlinear models. Health Serv. Res. 47, 255–274 (2012).

Ai, C. & Norton, E. C. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Econ. Lett. 80, 123–129 (2003).

Ramachandran, A. et al. Predictive analytics for retention in care in an urban HIV clinic. Sci. Rep. 10, 6421 (2020).

Spach, D. H. Core Concepts—Retention in HIV Care—Basic HIV Primary Care (National HIV Curriculum, 2025).

Hoover, K. W. et al. HIV services and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, 2019–2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 71, 1505–1510 (2022).

The People Living with HIV Stigma Index 2.0 Cambodia: Research Report. (2019).

GNP+. 2021. Implementation Guidelines, a handbook to support network of PLHIV to conduct the PLHIV Stigma Index.

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M. & Keller, S. D. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 34, 220–233 (1996).

Wada, K. et al. Validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale as a screening instrument of major depressive disorder among Japanese workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 50, 8–12 (2007).

Ngin, C. et al. Social and behavioural factors associated with depressive symptoms among university students in Cambodia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 8, e019918 (2018).

Tan, M. L. et al. Validity of a revised short form-12 Health Survey Version 2 in different ethnic populations. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 45, 228–236 (2016).

Pyo, E. et al. Construct validity of the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) version 2 and the impact of lifestyle modifications on the health-related quality of life among Indian adults with prediabetes: results from the D-CLIP trial. Qual. Life Res. 33, 1593–1603 (2024).

81 FR 78605 - Non-Inferiority Clinical Trials To Establish Effectiveness; Guidance for Industry; Availability. (Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, 2016).

Greenland, S. Basic methods for sensitivity analysis of biases. Int. J. Epidemiol. 25, 1107–1116 (1996).

Lash, T. L. et al. Good practices for quantitative bias analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 1969–1985 (2014).

ROGAN, W. J. & GLADEN, B. Estimating prevalence from the results of a screening test. Am. J. Epidemiol. 107, 71–76 (1978).

Simoni, J. M. et al. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: a review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav. 10, 227–245 (2006).

Berg, K. M. & Arnsten, J. H. Practical and conceptual challenges in measuring antiretroviral adherence. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 43, S79–S87 (2006).

Smith, R. et al. Accuracy of measures for antiretroviral adherence in people living with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 7, Cd013080 (2022).

Thirumurthy, H. et al. Differences between self-reported and electronically monitored adherence among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in a resource-limited setting. AIDS 26, 2399–2403 (2012).

Xi, W., Pennell, M. L., Andridge, R. R. & Paskett, E. D. Comparison of intent-to-treat analysis strategies for pre-post studies with loss to follow-up. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 11, 20–29 (2018).

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. (StataCorp LLC, 2023).

van Buuren, S. & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–67 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The French Government’s L’Initiative funded this study through Expertise France (Grant No. 19-SB0765, S.Y). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, statistical analysis, data interpretation, or report writing. The statements and conclusions presented in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of L’Initiative or Expertise France. The research was technically supported by the National Centre for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology, and STD, the Khmer HIV/AIDS NGO Alliance, the Cambodian People Living with HIV Network, the ARV Users Association, Partners in Compassion, and participating ART clinics. The authors sincerely thank the CAWs and community members for their invaluable support of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.T. developed the data analysis plan, conducted data analyses, and wrote the initial draft. P.C. and S.T. contributed to the study design, supervised project implementation, led data collection efforts, and provided feedback on the draft. E.L.Y.Y., M.N.-H., and M.Z. supported the data analyses and offered input on the draft. S.C.C., S.S., B.N., and V.O. provided strategic advice on intervention development, implementation, and evaluation, and reviewed the manuscript for accuracy. A.K.J.T. and K.P. played critical roles in study design, contributed to the data analysis plan, and provided feedback on the draft. S.Y. secured funding, led the study design, and oversaw project implementation, data collection, analyses, and manuscript writing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript and held ultimate responsibility for the decision to submit it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions