Abstract

Optical spectrometers are indispensable tools across various fields, from chemical and biological sensing to astronomical observations and quantum technologies. However, the integration of spectrometers onto photonic chips has been hindered by the low spectral resolution or large device footprint with complex multiple channel operations. Here, we introduce a chip-integrated spectrometer by leveraging the acoustically-stimulated Brillouin scattering in a hybrid photonic-phononic chip. The Brillouin interaction provides a dynamic reflection grating with a high reflectivity up to 50% and a fast switching time on the microsecond scale, achieving a spectral resolution of 0.56 nm over a 110 nm bandwidth using just a single 1 mm-long straight waveguide. This performance approaches the fundamental limit of resolution for a given device size, validating the potential of the hybrid photonic-phononic device for efficient and dynamically-reconfigurable spectral analysis, and thus opens up the avenues for advanced optical signal processing and sensing applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photonic integrated circuits (PICs) have emerged as a powerful platform1,2,3,4,5,6, which has the potential to revolutionize the way we generate, process, and manipulate light. By integrating various optical components onto a single chip, PICs enable the realization of sophisticated optical systems that offer unparalleled scalability, low power consumption, high stability, and enhanced light-matter interaction. In recent years, significant progress has been made in the development of PIC technologies, leading to notable achievements in various fields, such as ultra-high data transmission rates in optical communications7, ultra-sensitive biosensors8, and quantum photonic devices for secure communication and computation9. To further unlock the capability of PIC in spectroscopic analysis for astronomy measurements10,11, medical diagnostics12, environmental monitoring13, and chemical analysis14,15, high-performance optical spectrometers are indispensable16,17,18.

However, the full integration of spectrometers onto photonic chips faces a fundamental trade-off between spectral resolving capability and device footprint16. Conventional spectrometers mostly rely on static dispersive elements, which could be directly extended to PICs19,20,21. For example, the grating shown in Fig. 1a separates light of different colors into distinct channels. While the grating offers a wide detection wavelength range, achieving high spectral resolution necessitates a large device length and a dense array of collection channels. The spectral resolution of a grating-based spectrometer is approximately given by \({\Delta }_{\lambda }={\lambda }^{2}/{n}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}L\left(\sin {\theta }_{1}+\sin {\theta }_{2}\right)\), where L is the grating length, neff is the effective refractive index of the guided optical mode, λ is the light wavelength, and θ1(2) is the angle between the input (output) optical beam and the grating. An alternative approach is to employ dynamically tunable dispersive devices, such as Mach-Zehnder interferometers22,23,24 shown in Fig. 1b. These devices offer potential advantages including higher optical throughput, reduced device footprint, and requirement of fewer detection channels. Nonetheless, the resolution of this approach is limited by the device’s tuning capability. The spectral resolution of a tunable interferometer-based spectrometer is given by Δλ = λ2/neffΔL with ΔL is the tuning path difference of the interferometer. The requirement for a large tuning length δnΔL ≫ λ, where δn is the variation of the material refractive index. This requirement imposes a practical limitation of the spectrometer size L, limiting it to the order of centimeters, even with the enhancement provided by microrings25. Consequently, there is a pressing need for an approach that combines the advantages of both static and dynamic dispersive elements, enabling the realization of compact, single-channel on-chip spectrometers.

a–b Conventional on-chip spectrometers based on linear processes. a A static planar grating enables dispersive optics to separate light with different wavelengths. b Wavelength of the input light can be derived through a Fourier-transform approach by dynamically tuning a microring resonator or a Mach-Zehnder interferometer. c The proposed spectrometer is based on nonlinear process that employs the phase-matching condition of acoustically-stimulated Brillouin scattering to achieve wavelength-dependent optical reflection. The input laser (ω1) and phonon drive (Ω) propagate in opposite directions, and the reflected light (ω2) satisfies both momentum and energy conservations.

Here, we introduce a fundamentally different approach to integrated spectroscopy that leverages acoustically-stimulated backward Brillouin scattering, a nonlinear optical interaction between photons and acoustic phonons in a medium (Fig. 1c). By harnessing the strong interaction between guided optical and acoustic modes in a carefully engineered lithium niobate (LN) waveguide, we demonstrate a high-resolution, compact, and fully integrated spectrometer with an intrinsic spectral resolution of 0.56 nm over a wavelength range exceeding 110 nm, while maintaining a compact footprint of just 1 mm in length. Our approach provides a coherent interface between the optical spectrometer and radio frequency (RF) control, allowing fast spectral sweeping, with a typical sweep duration of 0.1 seconds and could potentially be even faster. Furthermore, our demonstration of a hybrid photonic-phononic circuit can be extended to incorporate other photonic, electronic, and phononic devices on a single chip, paving the way for fully integrated and multi-functional spectroscopic systems and also for a wide range of photonic-phononic hybrid devices.

Results

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual schematics of conventional integrated spectrometers and the principle of the proposed approach based on Brillouin scattering9,26,27,28,29. Traditional on-chip spectrometers typically rely on linear optical processes, such as dispersive elements in Fig. 1a or Fourier-transform techniques in Fig. 1b. In contrast, our spectrometer exploits the nonlinear Brillouin interaction between guided photonic and phononic modes in a compact waveguide platform (Fig. 1c)30. At the heart of our device is a straight waveguide that supports both optical and acoustic modes, which are coupled primarily through the photoelastic effect. The waveguide is integrated with a compact interdigital transducer (IDT) for RF-to-acoustic wave conversion and with grating couplers that enable efficient excitation and detection of the optical response. When operating the spectrometer, an input optical signal (ω1) is coupled into the waveguide and interacts with a counter-propagating acoustic wave (Ω) generated by the IDT.

The Brillouin scattering process manifests as a coherent three-wave mixing (TWM) interaction, leading to a wavelength-dependent coupling between forward and backward optical signals stimulated by acoustic wave fields. This coherent TWM results in a frequency-shifted output signal (ω2) that satisfies both the energy and momentum conservation conditions: ω2 = ω1 + Ω and k2 = k1 + β, where k1(2) and β are the wavevectors of the input (output) optical signal and acoustic wave, respectively. In a simpler picture, the acoustic wave modulates the refractive index along the waveguide through the photoelastic effect, and thus the waveguide can be understood as a dynamic optical grating. Therefore, our spectrometer resembles a linear grating spectrometer (Fig. 1a) with the corresponding input and output angles θ1 = θ2 = π/2, allowing us to achieve a spectral resolution approaching the theoretical upper bound of λ2/2neffL for a given interaction length L. Moreover, our single-channel device can resolve a wide spectral range through dynamically reconfigurable β by simply sweeping the external RF drive frequency.

To experimentally validate our ultra-compact spectrometer, we fabricate the hybrid phononic and photonic circuits using thin-film LN on a sapphire substrate. The combination single-crystal LN and sapphire allows for low-loss photonic and phononic waveguides, while LN’s strong piezoelectric and photoelastic properties facilitate efficient interfacing among the RF, acoustic, and optical signals, making it an ideal material platform for our spectrometer. The device, shown in Fig. 2b, features a straight waveguide with a width of 1.2 μm, a thickness of 400 nm, and a wedge step of 180 nm. This carefully designed geometry supports both optical modes at telecom wavelengths and acoustic modes around 8.5 GHz, with a phase-matched phonon wavelength of 400 nm. The corresponding mode profiles of the photonic and phononic modes are shown in Fig. 2d and g. To excite and focus the acoustic wave into the waveguide, we employ a fan-shaped IDT (Fig. 2c) driven by a RF signal from a vector network analyzer (VNA). The RF S11 parameter of the transducer, as shown in Fig. 2f, exhibits a resonance frequency of 8.5 GHz, indicating the efficient generation of high-frequency guided phonons into the waveguide.

a–b Experimental setup for characterizing the spectrometer. The phononic mode in the waveguide is driven by a vector network analyzer (VNA) through an interdigital transducer (IDT, c). The optical input signal is reflected through the Brillouin process when the phase-matching condition is fulfilled. The reflected light is measured by the VNA through a heterodyne detection or directly detected by the photodiode (PD) under high signal-to-noise ratio conditions. The Brillouin interaction region is around 1 mm. EDFA erbium-doped fiber amplifier, PC polarization controller. d and g Displacement and electrical field distributions at the waveguide cross-section for the quasi-Rayleigh phononic mode and the fundamental transverse electric photonic mode, respectively. All these simulations were performed using the finite element method (COMSOL Multiphysics). c, e Scanning electron microscope pictures of the IDT and phononic-photonic mode multiplexing device. f S11 parameter of IDT which exhibits a resonance frequency of 8.5 GHz. h Measured reflected optical signal against the input RF frequency, with the input optical wavelength fixed at 1576 nm.

To efficiently couple phonons and photons into the same waveguide for Brillouin interaction, while protecting the electrodes from potential damage caused by direct interaction between the input laser and the IDT, we have designed a hybrid phononic-photonic multiplexing device, as shown in Fig. 2e. This device exploits the tighter confinement of the phononic mode, allowing it to propagate through the waveguide with minimal coupling to adjacent waveguide due to the weak evanescent acoustic field. In contrast, the photonic mode can be efficiently transferred between the two waveguides when passing through the coupling region. Optical input and output couplings are achieved using grating couplers for high signal-to-noise ratio or using side couplings to avoid the sensitivity of coupling efficiency to wavelength and achieve a large wavelength bandwidth couple (A more detailed discussion provided in the Supplementary Information II.)

The experimental setup for characterizing the Brillouin scattering is depicted in Fig. 2a. A tunable laser, amplified by an erbium-doped fiber amplifier (EDFA) and with its polarization controlled, is coupled into the waveguide. The reflected optical signal at the selected wavelength, which satisfies the phase-matching condition of Brillouin scattering in the spectrometer, is collected and directed to a photodetector. To investigate the spectrometer’s performance, we fixed the input optical wavelength at 1576 nm and scanned the input RF signal supplied by the VNA, measuring the reflected light intensity with an interaction length L = 1 mm. The result, shown in Fig. 2h, demonstrates the remarkably reflection of the acoustically-induced dynamic grating. The spectrum exhibits a narrow linewidth, with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of just 3.4 MHz, validating the highly selective spectral response and also sub-μs switching time for high-resolution on-chip spectral analysis. Moreover, with an RF drive power of only 20 mW, as shown in Fig. 3a, the grating achieves a peak reflectivity of 50%, which highlights the efficient Brillouin interaction enabled by the carefully engineered hybrid photonic-phononic waveguide.

a Separate spectral line response with different pump wavelengths, with an RF drive power is 20 mW. Inset: the relationship between the reflected optical power and the input power; Dispersion relationship between the beat frequency of the output light and the input optical wavelength. The slope is 6.03 MHz/nm. b Top: RF response spectrum with two pump lasers at 1550.5 nm and 1550 nm. The red line represents a double-Lorentz fitting for the measured data, which is the sum of two Lorentz distributions displayed in yellow. Bottom: Reconstructed optical spectrum. c We use a standard commercial dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) as a filter to generate the spectrum by tuning the spontaneous radiation of our EDFA without any laser input. The blue line represents the reflection power from our device via sweeping microwave frequency and detected by a PD directly, and the orange line comes from a commercial spectrometer.

Figure 3 demonstrates the broadband performance of our spectrometer. In Fig. 3a, the responses for monochromatic optical input signals are measured for different wavelengths ranging from 1514 to 1624 nm, with an experimental wavelength of 110 nm limited by the spectral range of our testing optical source. The linear dependence between the input and reflected optical powers, as shown in the left inset of Fig. 3a, verifies the coherent TWM process of acoustically-stimulated Brillouin scattering. The right inset of Fig. 3a depicts the linear dispersion relationship between the frequency shift of the output light and the input optical wavelength, with a slope of 6.03 MHz/nm. Combined with the narrow bandwidth of the RF response [Fig. 2h], we derive an optical intrinsic spectral resolution of 0.56 nm. The envelope of the varying peak values represents the frequency-dependent RF-phonon conversion efficiency, which is determined by the bandwidth of the IDT. It is worth noting that the observed fluctuations on this envelope reflect the complete, wavelength-dependent system transfer function, which includes not only the IDT response but also factors such as the intrinsic acousto-optic coupling strength and on-chip polarization effects. This entire repeatable response is captured in the calibration matrix used for spectral reconstruction. Although the experimental data is acquired over a 110 nm range, our analysis (Supplementary Information) indicates that the spectrometer can operate over a significantly broader wavelength range. Based on the characteristics of the current IDT design, we estimate that the dynamic range of the spectrometer exceeds 150 nm. Furthermore, by employing advanced broadband IDT designs or cascaded IDTs on a single waveguide, the operating range can potentially be extended to 300 nm or more.

To directly demonstrate the sub-nanometer resolution of our spectrometer, we perform a spectral measurement using a source consisting of two laser tones as input, with a wavelength interval of only 0.5 nm. By scanning the RF drive frequency, we obtain the spectral information shown in Fig. 3b. The raw data clearly shows two distinctly resolved peaks. We fit the data using a double-Lorentzian function, which is the sum of two Lorentzian distributions displayed in red. Furthermore, by using the spectral response for monochromatic light in Fig. 3a, we reconstruct the input spectrum with respect to the optical wavelength. The retrieved wavelength data are consistent with our input laser wavelengths, proving that the projected resolution of our spectrometer can be much better than 0.5 nm.

To further demonstrate the fluorescence measurement capability of our spectrometer and its potential in telecom applications, we use an EDFA to generate a broadband spectrum and utilize a dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) filter to synthesize a broadband light source. The DWDM filter allows us to selectively switch on and off specific bandpass channels (e.g., C23-C26) to create controlled spectral features. As shown in Fig. 3c, the spectrum is first measured using a commercial spectrometer as a reference and delivered to our device. In contrast to the heterodyne detection scheme mentioned in Fig. 2a, the output signal from our device is directly detected by a PD. The response spectrum in Fig. 3c (blue line) reveals a frequency-independent background noise floor, which we attribute to reflections of the input signal in our system, primarily due to the backward scattering from the coupler. By mapping the RF response to the optical domain, we derive the optical spectrum, which exhibits excellent agreement with the reference spectrum measured by a commercial spectrometer (orange line). This measurement result demonstrates that our spectrometer possesses the capability to resolve fluorescence spectra and is well-suited for DWDM, which is widely used in the telecom technology.

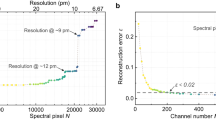

In Fig. 4a, we compare the performance of our device with state-of-the-art demonstrations reported in the literature19,20,21,22,23,25,31,32,33,34,35, focusing on the intrinsic spectral resolution of the devices. The intrinsic spectral resolution is governed by the dispersive path of the device, which is determined by its inherent optical response bandwidth, regardless of the input signal strength, detection noises, and the reconstruction algorithms36,37,38,39,40. Our device exhibits high performance in terms of resolution and footprint. According to the coherent mode conversion in an ideal uniform waveguide, the intrinsic resolution is determined by the phase-matching condition in the coupled mode equations41 (Supplementary Information). For a fixed RF frequency, the reflected light has a bandwidth corresponding to the FWHM of the wavevector Δβ ≈ 5.56/L, which implies a fundamental trade-off relation between resolution and footprint. Considering the dispersion relation of the photonic mode as ∂β/∂λ = 1.2 × 104 rad/(m ⋅ nm), the fundamental limitation of resolution is given by

For an interaction length L = 1 mm in our device, the resolution limit for an ideal lossless waveguide is 0.46 nm, indicating that our experimental result of 0.56 nm approaches this fundamental limit with a small discrepancy attributed to the losses. Also, we find that the practical resolution of our spectrometer does not improve with further increases in L, revealing the constraints imposed by the propagation loss of the phononic mode in the waveguide. As shown by the red lines in Fig. 4b, the resolution considering the phonon attenuation is calculated for given equivalent phononic quality factors (Q), and a Q = 3000 explains our observations of the saturated resolution for L > 1 mm. Furthermore, the potential imperfections of non-uniform waveguide cross-section can introduce variations in the mode wavevectors, which can be treated as a phase-matching diffusion process in the mode conversion and reduce the resolution. The dependence of the phase mismatching Δβ on the variation of the waveguide width (Δw) and film thickness (Δt) is shown in Fig. 4c, demonstrating that the two geometry parameters independently contribute to the mismatching. By assuming a random walk of Δβ and the accumulated mismatch in the interaction region following a normal distribution, we numerically simulate the influence of the phase-matching diffusion with a standard deviation σ = 1500 rad/m for different phonon Q (Supplementary Information). The results are plotted in Fig. 4b as dots, with the shaded area representing the standard deviation. These results show that the impact of phase-matching diffusion becomes more pronounced for higher Q. Therefore, a resolution of 0.1 nm with an interaction length under 6 mm is feasible by improving phonon Q by one order of magnitude42 and suppressing the variation of Δβ through compensating for film thickness variations via specially designed modulations in the waveguide width43.

a A plot comparing the resolution, detection channel, and footprint scale for selected device demonstrations in the literature. The footprint scale includes the elements in the device that are active in resolving and detecting light, excluding the accessory components. Reference numbers are indicated within square brackets. b Simulation results of the device resolution performance improved by the interaction length (L). The red line represents the result based on the current material and fabrication level with a phonon Q ~ 3000. The blue line shows the resolution with an improvement of phonon Q ~ 20000 in future experiments. The dots represent the simulation results with the impact from the phase-matching diffusion and the shadow part represents the standard deviation of the resolution. The standard deviation of the random diffusion value added in simulation is about 1500 rad/m, which represents the standard derivation of waveguide width (Δw) around 4 nm and film thickness (Δt) around 0.5 nm. c The heatmap represents the relationship between mismatching value Δβ and variation error on Δw and Δt. The cyan line corresponds to the diffusion value in b.

Discussion

Our demonstration of the acoustically-stimulated Brillouin scattering introduces a paradigm for on-chip spectroscopy by leveraging the unique properties of hybrid photonic-phononic circuits. The spectrometer presented in this work holds great promise for its simplicity, robustness, and ease of fabrication, as well as its potential for large-scale integration with other photonic and electronic components1,44. The absence of moving parts or suspended structures makes our device inherently stable and reliable, offering a compact, stable, and cost-effective solution for spectral analysis without the need for any free-space optical components. The performance of our spectrometer, particularly in terms of resolution and bandwidth, can be further enhanced by optimizing the device design and fabrication.

Our work validates a hybrid photonic-phononic platform, which not only provides a approach for dispersion manipulation on a chip but also serves as the foundation for a chip architecture. We term this platform as “Zhengfu" hybrid chip architecture, and it can be extended to other material platforms, such as scandium aluminum nitride (ScAlN) on sapphire45 and lithium tantalate (LiTaO3) on sapphire46, offering flexibility in material choice for specific applications. This architecture enables an efficient interface between RF and optical signals, opening up the possibilities for optoelectronic devices, and offering a complementary paradigm to electro-optic modulation for optical information processing. For instance, dynamically reconfigurable lasing on a chip can be realized by simply controlling the RF drive amplitude and frequency. This can enable fast frequency sweeping or multiple laser emission, paving the way for advanced on-chip laser sources with enhanced functionality and versatility. Moreover, the Zhengfu architecture is compatible with superconducting quantum devices, such as SNSPD, superconducting resonators, and qubits, thereby presenting exciting opportunities for future quantum information processing.

Methods

Device fabrication process

We fabricate the hybrid phononic and photonic circuits using LN-on-sapphire structure. In this work, we use x-cut LN-on-sapphire wafer featuring 400 nm LN layer on a 400 μm thick sapphire substrate. The fabrication process of the LN-on-sapphire chip involves two main steps. First, we define the optical waveguides using hydrogen silsesquioxane (HSQ) as the resist using electron beam lithography (EBL). The structures are then etched using argon etching. The optical wedge waveguides are formed by partially etching the LN layer by 220 nm, leaving a 180 nm-thick slab layer. Second, an interdigital transducer (IDT) structure are defined in another EBL step using polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) resist. A layer of 20 nm Aluminum is then deposited on the top of LN using an electron beam evaporator, followed by a liftoff process.

Spectrometer characterizing

In our experiment, we designed different optical coupling structures and testing setups for various application scenarios. Regarding optical coupling, we utilized different coupling methods. We employed both grating coupling and side coupling to achieve efficient input-output relationships. Meanwhile, we implemented two distinct testing methods: one is the heterodyne detection method mentioned in Fig. 2(a), and the other directly measures the intensity of the reflected signal via a photodiode shown in Fig. 3c. Side coupling is typically combined with heterodyne detection due to its advantage in enabling broadband signal measurement without the coupling efficiency being affected by wavelength. However, side coupling tends to introduce significant background reflection noise, which can lower the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) when directly reading the reflected signal power. To address this, heterodyne detection is employed to enhance the SNR, as demonstrated by the data in Fig. 3a.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Further source data will be made available on request.

Code availability

The code used to solve the equations presented in the Supplementary Information will be made available on request.

References

Elshaari, A. W., Pernice, W., Srinivasan, K., Benson, O. & Zwiller, V. Hybrid integrated quantum photonic circuits. Nat. Photon. 14, 285 (2020).

Wang, J., Sciarrino, F., Laing, A. & Thompson, M. G. Integrated photonic quantum technologies. Nat. Photon. 14, 273 (2020).

Shekhar, S. et al. Roadmapping the next generation of silicon photonics. Nat. Commun. 15, 751 (2024).

Pelucchi, E. et al. The potential and global outlook of integrated photonics for quantum technologies. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 194 (2022).

Kippenberg, T. J. & Vahala, K. J. Cavity optomechanics: back-action at the mesoscale. Science 321, 1172 (2008).

Wang, C. et al. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at cmos-compatible voltages. Nature 562, 101 (2018).

Corcoran, B. et al. Ultra-dense optical data transmission over standard fibre with a single chip source. Nat. Commun. 11, 2568 (2020).

Shen, M.-Y., Li, B.-R. & Li, Y.-K. Silicon nanowire field-effect-transistor based biosensors: From sensitive to ultra-sensitive. Biosens.Bioelectron. 60, 101 (2014).

Eggleton, B. J., Poulton, C. G., Rakich, P. T., Steel, M. J. & Bahl, G. Brillouin integrated photonics. Nat. Photon. 13, 664 (2019).

Jovanovic, N. et al. 2023 astrophotonics roadmap: pathways to realizing multi-functional integrated astrophotonic instruments. New J. Phys. Photon. 5, 042501 (2023).

Yu, M. et al. Silicon-chip-based mid-infrared dual-comb spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 9, 1869 (2018).

Kong, K., Kendall, C., Stone, N. & Notingher, I. Raman spectroscopy for medical diagnostics-from in-vitro biofluid assays to in-vivo cancer detection. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 89, 121 (2015).

Ho, C. K., Robinson, A., Miller, D. R. & Davis, M. J. Overview of sensors and needs for environmental monitoring. Sensors 5, 4 (2005).

Kneipp, K., Kneipp, H., Itzkan, I., Dasari, R. R. & Feld, M. S. Ultrasensitive chemical analysis by Raman spectroscopy. Chem. Rev. 99, 2957 (1999).

Harper, N. A., Hwang, E. Y., Kocheril, P. A., Lam, T. K. & Cushing, S. K. Subtleties of nanophotonic lithium niobate waveguides for on-chip evanescent wave sensing. Opt. Express 32, 27931 (2024).

Yang, Z., Albrow-Owen, T., Cai, W. & Hasan, T. Miniaturization of optical spectrometers. Science 371, eabe0722 (2021).

Bacon, C. P., Mattley, Y. & DeFrece, R. Miniature spectroscopic instrumentation: applications to biology and chemistry. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 75, 1 (2004).

Crocombe, R. A. Portable spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 72, 1701 (2018).

Calafiore, G. et al. Holographic planar lightwave circuit for on-chip spectroscopy. Light Sci. Appl. 3, e203 (2014).

Faraji-Dana, M. et al. Compact folded metasurface spectrometer. Nat. Commun. 9, 4196 (2018).

Cheng, R. et al. Broadband on-chip single-photon spectrometer. Nat. Commun. 10, 4104 (2019).

Kita, D. M. et al. High-performance and scalable on-chip digital Fourier transform spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 9, 4405 (2018).

Pohl, D. et al. An integrated broadband spectrometer on thin-film lithium niobate. Nat. Photon. 14, 24 (2020).

Finco, G. et al. Monolithic thin-film lithium niobate broadband spectrometer with one nanometre resolution. Nat. Commun. 15, 2330 (2024).

Zheng, S. N. et al. Microring resonator-assisted Fourier transform spectrometer with enhanced resolution and large bandwidth in single chip solution. Nat. Commun. 10, 2349 (2019).

Liu, Q., Li, H. & Li, M. Electromechanical Brillouin scattering in integrated optomechanical waveguides. Optica 6, 778 (2019).

Ye, K. et al. Integrated Brillouin photonics in thin-film lithium niobate. Science Advances 11, eadv4022 (2025).

Rodrigues, C. C. et al. Cross-polarized stimulated Brillouin scattering in lithium niobate waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 113601 (2025).

Wiederhecker, G. S., Dainese, P. & Mayer Alegre, T. P. Brillouin optomechanics in nanophotonic structures. APL Photon. 4, 7 (2019).

Wang, W. et al. High-acoustic-index-contrast phononic circuits: Numerical modeling. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 18 (2020).

Cheben, P. et al. A high-resolution silicon-on-insulator arrayed waveguide grating microspectrometer with sub-micrometer aperture waveguides. Opt. Express 15, 2299 (2007).

Koshelev, A. et al. Combination of a spectrometer-on-chip and an array of young’s interferometers for laser spectrum monitoring. Opt. Lett. 39, 5645 (2014).

Zou, J., Lang, T., Le, Z. & He, J.-J. Ultracompact silicon-on-insulator-based reflective arrayed waveguide gratings for spectroscopic applications. Appl. Opt. 55, 3531 (2016).

Nedeljkovic, M. et al. Mid-infrared silicon-on-insulator Fourier-transform spectrometer chip. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 28, 528 (2015).

Nie, X., Ryckeboer, E., Roelkens, G. & Baets, R. Cmos-compatible broadband co-propagative stationary fourier transform spectrometer integrated on a silicon nitride photonics platform. Opt. Express 25, A409 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Single-shot on-chip spectral sensors based on photonic crystal slabs. Nat. Commun. 10, 1020 (2019).

Redding, B., Liew, S. F., Sarma, R. & Cao, H. Compact spectrometer based on a disordered photonic chip. Nat. Photon. 7, 746 (2013).

Yang, Z. et al. Single-nanowire spectrometers. Science 365, 1017 (2019).

He, X. et al. A microsized optical spectrometer based on an organic photodetector with an electrically tunable spectral response. Nat. Electron. 7, 694–704 (2024).

Li, A. & Fainman, Y. On-chip spectrometers using stratified waveguide filters. Nat. Commun. 12, 2704 (2021).

Sipe, J. & Steel, M. A Hamiltonian treatment of stimulated Brillouin scattering in nanoscale integrated waveguides. New J. Phys. 18, 045004 (2016).

Bajak, I., McNab, A., Richter, J. & Wilkinson, C. Attenuation of acoustic waves in lithium niobate. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 69, 689 (1981).

Chen, P.-K. et al. Adapted poling to break the nonlinear efficiency limit in nanophotonic lithium niobate waveguides. Nat. Nano. 19, 44 (2024).

Xu, X.-B., Wang, W.-T., Sun, L.-Y. & Zou, C.-L. Hybrid superconducting photonic-phononic chip for quantum information processing. Chip 1, 100016 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Scandium-doped aluminum nitride for acoustic wave resonators, filters, and ferroelectric memory applications. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 5, 612 (2022).

Bartasyte, A., Margueron, S., Baron, T., Oliveri, S. & Boulet, P. Toward high-quality epitaxial LiNbO3 and LiTaO3 thin films for acoustic and optical applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 4, 1600998 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Prof. Yeteng Zhong for discussions and to Wen Liu for the assistance in fabrication. This work was funded by the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (Grant Nos.~2024ZD0301500 and 2021ZD0300203), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 92265210, 123B2068, 12104441, 92165209, 12293053, 11925404, 12374361, 92365301, and 92565301). We also acknowledge the support from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and USTC Research Funds of the Double First-Class Initiative. The numerical calculations in this paper were performed on the supercomputing system in the Supercomputing Center of University of Science and Technology of China. This work was partially carried out at the USTC Center for Micro and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-L.Z. and L.S. conceived the experiments. J.-Q.W., Y.-H.Y. and Z.-X.Z. designed and fabricated the devices, built the experimental setup, carried out the measurements, and analyzed the data with the assistance from X.-B.X., L.S., Z.-X.Z., J.-J.L., X.P., C.M., L.X., B.Z., W.W., and C.-H.D. M.L. provided theoretical support. J.-Q.W. and C.-L.Z. wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors. G.-C.G., L.S., and C.-L.Z. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Duk-Yong Choi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, JQ., Yang, YH., Zhu, ZX. et al. Compact and high-resolution spectrometer via Brillouin integrated circuits. Nat Commun 17, 68 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66638-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66638-3