Abstract

Near-infrared (NIR) organic photodetectors (OPDs) offer a promising platform for skin-integrated optical communication systems, but achieving high-speed operation under mechanical stress remains a central obstacle. Here, we report a skin-conformable OPD with a 3 μm total thickness that achieves a specific detectivity calculated from noise-equivalent power of 0.84 × 1014 Jones at 790 nm and a − 3 dB cut-off frequency exceeding 1 MHz, maintained under 66% compressive strain and sub-5 μm bending radius. This performance is enabled by an engineered Br-functionalized PACz hole transport layer, which facilitates efficient charge extraction without compromising mechanical resilience. When conformally mounted on human skin, the device supports angle-independent responsivity across a 0–90° range and enables wireless reception of audio-modulated signals from a 100 m distant source with a bit-error rate of 10−3. These results define a new performance regime for ultrathin, deformable NIR photodetectors by overcoming the trade-off between speed and flexibility, and demonstrate their scalable integration into skin-mounted, interactive communication systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Near-infrared organic photodetectors (NIR-OPDs) have emerged as key components for next-generation wireless communication systems, offering high-speed, energy-efficient data transmission through direct optical modulation1,2,3. Unlike conventional inorganic photodetectors that rely on rigid device architectures and require high-intensity optical signals for high-speed operation, NIR-OPDs leverage tunable optoelectronic properties through molecular engineering to achieve superior sensitivity under low-light conditions while maintaining rapid response times4,5. Their mechanical compliance ensures stable operation under deformation6,7, and their compatibility with lightweight, conformal substrates enables seamless integration into wearable systems8,9. In addition, their low-energy operation10, use of invisible and biocompatible signals11, and resilience against electromagnetic interference12,13 make them particularly suited for human-centric applications, including real-time sensors and interactive interfaces14. These advantages position NIR-OPDs as ideal candidates for skin-integrated communication platforms, enabling reliable performance under dynamic conditions and paving the way for advanced optical wireless communication technologies.

Recent advances in high-speed NIR-OPDs have demonstrated −3 dB cut-off frequencies (f−3dB) exceeding 1 MHz on rigid or bendable substrates, allowing rapid data transmission15,16. Moreover, key strategies for achieving high-speed performance involve optimizing the photoactive layer geometry to minimize resistance by reducing the thickness. In parallel, parasitic capacitance can be suppressed through area scaling. In addition, molecular-level engineering of photoactive materials can enhance their charge transport efficiency and accelerate their carrier dynamics17. Keeping flexibility as a key criterion, NIR-OPDs have demonstrated stable photoresponsivity over 10,000 bending cycles tested under a 7.5-mm bending radius18. Although high-speed NIR-OPDs with micrometer-scale bending radiuses have not been demonstrated yet, their potential use as fast, flexible photodetectors for NIR wireless communication suggests feasibility in wearable systems requiring both mechanical durability and optical speed.

However, simultaneously achieving high-speed responsivity and high detectivity in NIR photodetectors under mechanical deformation remains a fundamental challenge. High crystallinity in the photoactive layer enhances carrier mobility and enables rapid charge extraction, yet it can compromise mechanical flexibility, often leading to cracking or delamination under strain19. To mitigate this trade-off, device architectures incorporating charge transport layers with well-aligned stepped energy barriers have been developed to support fast carrier extraction without relying on rigid crystalline domains20. Furthermore, smooth and precisely engineered interfaces with minimal trap states and low roughness are critical for suppressing charge trapping and minimizing noise while also alleviating stress concentrations that can undermine mechanical reliability21,22. Consequently, the realization of flexible, high-performance NIR photodetectors requires co-optimizing their charge transport efficiency and structural resilience.

In this study, we developed ultrathin (3 μm) skin-conformal NIR-OPDs that simultaneously achieved high detectivity, MHz-level speed through a Br-functionalized PACz interlayer, and angle-independent responsivity, enabling wireless data reception from a light source 100 m away. By employing Br-functionalized carbazole-based phosphonic acid (PACz) as a hole-selective charge transport layer, the device achieved a specific detectivity calculated from noise-equivalent power (DNEP*) of 0.84 × 1014 Jones at 790 nm and an f−3dB exceeding 1 MHz, even under 66% mechanical compression, ensuring seamless skin-conformal adhesion and exceptional mechanical resilience with a low bending radius of 4.90 μm (Supplementary Table 1). This low bending radius allows the fabricated devices to conform intimately to highly curved and wrinkled regions such as fingertips or finger joints, thereby enabling stable operation even under repeated deformation21. Notably, our NIR-OPDs established a new benchmark by combining their extreme flexibility with their high-speed photoresponse (Supplementary Fig. 1). These advances enabled stable, high-speed data reception over a wide range of incident angles (0–90°), supporting reliable long-range operation on complex geometries.

Results

Impact of PACz interfacial layers on optoelectronic and charge transport properties

A schematic of the ultraflexible organic NIR wireless communication receiver is shown in Fig. 1a. The inverted OPD structure was fabricated in Parylene-C (1 μm)/SU-8 layer (500 nm)/indium tin oxide (ITO, 100 nm)/zinc oxide (ZnO, 40 nm)/photoactive layer (150 nm)/ PACz layer (5 nm)/molybdenum trioxide (MoO3, 5 nm)/Ag (100 nm). A bulk heterojunction (BHJ) based on a PM6 and Y6 mixture served as the photoactive layer. Three different PACz materials—that is, 2PACz, 3-Br-4PACz, and 3,6-Br-4PACz—were strategically selected to fine-tune the energy band and surface energy between the photoactive layer and the MoO3 hole transport layer (HTL). Different PACz materials were specifically chosen because their phosphonic acid groups ensure strong interfacial binding and work function tuning, while their ultrathin and transparent nature minimizes optical loss and enhances device stability. The chemical structures and detailed chemical information, including the molecular formulas and systematic nomenclature, of the photoactive layer components and PACz materials are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Through these three distinct PACz variants, we aim to investigate the effect of alkyl chain length and the addition of halogen substituents of PACz on the device performance23.

a Schematic of the ultraflexible near-infrared organic photodiode (NIR-OPD) architecture. b Energy band diagram of each layer. c Y6 distribution of the bulk-heterojunction components between the MoO3 and 3-Br-4PACz/MoO3 samples. The surface energy (γ) trend is represented by a blue-to-green gradation arrow. d Dipole moments along the x, y, and z axes, as well as the total dipole moment for each PACz material. e External quantum efficiency (EQE, solid line) and responsivity (dashed line) of the devices with different PACz layers. f J–V characteristics under forward-bias. g J–V characteristics under 1-Sun illumination (AM 1.5 G, solid line) and under dark conditions (dashed line). h Spectral specific detectivity (D*Dark) of the devices. i Decay profile of the charge current after turn-off of the irradiation light. The inset graph is the magnified decay profile in the range from 7 to 11 μs. j Number of remaining charges (RCs) depending on the carrier mobility was determined using the time-delayed collection field (TDCF) method. Inset image is the integration range of the charge current for the RCs.

The energy band alignment of the ZnO, PM6:Y6, PACz materials, and MoO3 are shown in Fig. 1b. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) levels of the individual layers were unveiled through spectroscopic analysis, involving ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2) and Tauc plots from ultraviolet–visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy24 (Supplementary Fig. 4). For the PACz layer to effectively mediate between the BHJ and MoO3 layer, a sequential and balanced energy band alignment is essential for efficient and stable hole transport25. All three PACz layers exhibited a deeper HOMO level than standard MoO3 but a shallower HOMO level than standard PM6 (Supplementary Fig. 5). In 2PACz—a well-investigated material in organic photovoltaics26—the energy difference between it and the donor material (PM6) is 0.18 eV, whereas that between it and the MoO3 layer is −0.07 eV. This asymmetric energy level configuration at the interface between the PM6 and 2PACz creates an unfavorable energy alignment, increasing charge recombination and limiting efficient hole extraction. Similarly, in 3,6-Br-4PACz, the additional Br substitution in the carbazole benzene ring further disrupts the cascade alignment, leading to excessive energy offsets with MoO3 and deteriorating the hole transport pathway. By contrast, 3-Br-4PACz—in which the terminal hydrogen at the third position of the carbazole benzene ring is substituted with Br and the alkyl chain length is extended to modulate the HOMO energy level23—exhibits a more balanced energy alignment. With energy level differences of 0.12 eV with PM6 and 0.13 eV with MoO3, 3-Br-4PACz effectively facilitates hole transport while minimizing carrier accumulation at the interfaces. This optimized energy cascade enhances charge extraction efficiency and reduces recombination losses, thereby improving overall device performance.

In addition to a well-balanced energy cascade, the uniform BHJ morphology is crucial for the stable formation of exciton and efficient charge dissociation. Poor phase distribution creates localized energy barriers, increasing charge trapping and reducing device performance27,28,29. To address this, controlling the surface energy to ensure uniform dispersion of mobile Y6 within the BHJ is crucial for enhancing the photoelectric efficiency and achieving high-speed signal reception. Without the PACz layer, the high surface energy contrast leads to an uneven phase distribution, with Y6 domains locally aggregated near the MoO3 side and insufficient extension toward the ITO interface, thereby causing inhomogeneous BHJ morphology and degraded device performance30. Contact-angle measurements31 revealed that 3-Br-4PACz-treated MoO3 exhibited the lowest surface energy (35.30 mN/m), whereas the surface energies for 2PACz and 3,6-Br-4PACz-treated MoO3 were 45.14 and 45.40 mN/m, respectively (Supplementary Table 3). Figure 1c illustrates the interfacial arrangement of Y6 molecules in the BHJ as a conceptual schematic. The minimal surface energy difference between the 3-Br-4PACz layer and Y6 enhanced miscibility, resulting in a more favorable interfacial contact and improved near-surface molecular packing of Y6 at the ITO/BHJ layer interface. This effect was further confirmed through depth profiling of the cyanide (CN‒) group, which corresponded to the Y6 concentration. Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry spectra, normalized to the total detected ion count (Supplementary Fig. 6), revealed a progressive weakening of the CN− signal in the sequence of 2PACz, pristine, 3,6-Br-4PACz, and 3-Br-4PACz samples, indicating a more balanced vertical distribution of Y6 with signals extending more clearly toward the ITO interface. Consequently, the results demonstrated that the most favorable interfacial morphology and reduced interfacial accumulation of Y6 were achieved in the 3-Br-4PACz sample.

In addition to modulating surface energy, the molecular orientation and intrinsic dipole characteristics of PACz derivatives play a pivotal role in governing interfacial charge transport between the photoactive layer and HTL. Benefiting from their amphiphilic molecular architecture, PACz molecules spontaneously adopt a vertically aligned orientation at the interface. The electron-rich carbazole moiety preferentially interacts with the hydrophobic PM6:Y6 surface through π–π stacking and van der Waals forces, while the phosphonic acid headgroup forms covalent bonds with the overlying MoO3 layer32. This orientation gives rise to a net dipole directed from the photoactive layer toward the HTL, thereby establishing an interfacial electric field that promotes directional hole extraction33. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Fig. 1d) further elucidate the dipolar behavior of these molecules. Among the derivatives, 3-Br-4PACz exhibits the strongest dipolar characteristics, with a total dipole moment of 4.77 Debye and an orientation angle of 45.0° relative to the phosphonic acid axis, corresponding to an x-axis projection of 3.37 Debye. This favorable orientation is instrumental in establishing an interfacial dipolar field aligned with the vertical transport direction. In contrast, 3,6-Br-4PACz and 2PACz exhibit lower overall dipole magnitudes of 4.35 and 2.51 Debye, respectively, reflecting a diminished ability to promote interfacial polarization. The superior dipolar alignment of 3-Br-4PACz is attributed to its asymmetric bromine substitution34 and extended alkyl side chain35, which synergistically enhance intramolecular charge separation and promote vertical alignment at the interface36,37,38. This strong molecular polarization, coupled with optimal surface energy compatibility with the Y6 domain, promotes a more favorable vertical distribution of acceptor molecules. The combined effect of molecular dipole orientation and interfacial energy alignment enhances charge transport dynamics, thereby improving device efficiency.

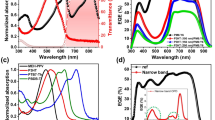

To align the physicochemical studies, the steady-state response of organic photodiodes with different PACz materials was evaluated. Figure 1e presents the external quantum efficiency (EQE) and responsivity of the devices across wavelengths spanning the Vis-to-NIR range. For the 3-Br-4PACz-based device, the relatively homogeneous distribution of Y6 molecules in the BHJ facilitated efficient hole generation and transport through the HTL, benefiting from the balanced energy barriers and a strong dipole moment. Consequently, the 3-Br-4PACz device achieved an EQE of up to 74.17% and a responsivity of 0.47 A/W at 790 nm under −0.25 V biased conditions, outperforming the other PACz-based and pristine devices.

The enhanced photogeneration capability of the 3-Br-4PACz device is further reflected in its superior photovoltaic performance, as demonstrated by the current density–voltage (J–V) characteristics (Fig. 1f). The device exhibited the highest short-circuit current density (JSC), open-circuit voltage (VOC), and fill factor (FF) among the tested PACz materials, indicative of the most efficient separation and extraction of photogenerated charge carriers. When measuring and calculating the photovoltaic parameters over eight different devices, the 3-Br-4PACz device exhibited the highest average power conversion efficiency of 15.22% under 1-Sun illumination (AM 1.5G), whereas the other samples failed to surpass 15% (Supplementary Table 4). To further investigate this performance, the linear characteristics of JSC and VOC were evaluated under varying illumination conditions. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7 the J–V characteristics were recorded while extracting JSC and VOC under light intensity (L) variations from 10−2 to 102 mW/cm2 (AM 1.5 G). According to the power-law relationships—that is, JSC ∝ Lα and VOC ∝ βkbT/q ln L, where α and β denote dimensionless coefficients, and kb, T, and q denote the Boltzmann constant, absolute temperature, and elementary charge, respectively39,40—JSC exhibited power-law dependence on L, while VOC showed logarithmic dependence on L. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, the calculated slopes of JSC versus L were 0.930, 0.922, 0.935, and 0.943 for the pristine, 2PACz, 3,6-Br-4PACz, and 3-Br-4PACz samples, respectively. The α value approached unity in the 3-Br-4PACz device, indicating reduced bimolecular recombination, attributed to enhanced photogeneration. Similarly, in the VOC versus L plot (Supplementary Fig. 9), the 3-Br-4PACz sample exhibited the lowest β value of 1.15, whereas the pristine, 2PACz, and 3,6-Br-4PACz samples exhibited β values of 1.51, 1.56, and 1.50, respectively. These results confirmed that the incorporation of the 3-Br-4PACz layer suppressed the photoelectron loss, thereby enhancing the charge flow efficiency compared to the other PACz devices (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Another important performance factor of OPD is the specific detectivity (D*), a key performance metric widely employed in photodetector studies. This method directly links the spectral responsivity and noise current under dark conditions. Figure 1g presents the photocurrent densities under 1-Sun illumination and the dark current densities of organic light receivers incorporating different types of PACz. Notably, in the ultralow-current regime, the minimum dark current density does not always coincide with 0 V, which we attribute to capacitive displacement currents and small offsets in the measurement circuit rather than intrinsic diode leakage41,42. The 3-Br-4PACz device exhibited the lowest dark current density of 0.03 nA/cm2 at −0.25 V bias, whereas its photocurrent was slightly higher than that of the other PACz-based devices. The improved performance could be attributed to the reduced surface roughness of the photoactive layer in 3-Br-4PACz compared to the other PACz materials (Supplementary Fig. 11), which minimized interfacial trap sites that could degrade the device performance22. This smoother morphology enhanced device efficiency while simultaneously contributing to prolonged operational stability, as evidenced by the 3-Br-4PACz-based devices retaining their performance for more than 168 h (7 days) under ambient conditions (Supplementary Fig. 12). As the D*Dark is inversely proportional to the dark current density, the 3-Br-4PACz device demonstrated the highest detectivity, reaching 1.56 × 1014 Jones at 790 nm under −0.25 V biased conditions (Fig. 1h). Remarkably, it maintained the D*Dark at more than 1014 Jones across a broad spectral range of 510–850 nm, demonstrating exceptional broadband sensitivity. However, calculating D* based on JD can yield unrealistically high values by neglecting noise sources other than shot noise. To resolve potential controversies regarding dark current-based overestimation, we conducted noise-equivalent power (NEP, Supplementary Fig. 13)-based validation (D*NEP). The peak D*NEP value (0.84 × 1014 Jones) exhibited excellent agreement with the D*Dark calculated from the dark current density, validating the consistency and reliability of our detectivity assessment.

To further investigate the photogeneration efficiency and recombination dynamics, we evaluated the field-driven mobility of photogenerated charges and their collection efficiency using time-delayed collection field (TDCF) analysis43,44. As shown in Fig. 1i, the transient photocurrent time—defined as the time required for the current to decay from 90% to 10% of its maximum value—was extracted to assess the charge extraction speed. The inset graph, magnified in the range of 7–11 μs, highlights the fastest photocurrent transient of 2.93 μs for the 3-Br-4PACz sample, compared to slower transients of 3.23, 3.62, and 3.05 μs for the pristine, 2PACz, and 3,6-Br-4PACz samples, respectively (Supplementary Table 5). The charge carrier mobility (μ) was calculated using the equation μ = d2/(V ∙ t0), where d, V, and t0 denote the thickness of the layer between the electrodes, collection voltage (fixed at −2 V in this study), and time at the maximum transient photocurrent, respectively. This mobility is closely correlated with the number of remaining charge carriers (RCs). As shown in Fig. 1j, the 3-Br-4PACz device exhibited the highest charge carrier mobility of 3.84 × 10−5 cm2/V·s, surpassing that of the pristine device (3.18 × 10−5 cm2/V·s), leading to reduced RCs through three mechanisms: (i) optimized HOMO level alignment at interface between PM6 abd MoO3, (ii) formation of a homogeneous BHJ morphology with vertically uniform Y6 distribution, and (iii) enhanced hole extraction driven by the pronounced dipole moment of 3-Br-4PACz. Consequently, the improved charge transport and suppressed recombination losses enabled the 3-Br-4PACz device to achieve superior performance at higher frequencies with minimal signal distortion, demonstrating its potential for high-speed optoelectronic applications in the NIR region.

Optoelectronic performance under NIR illumination

For further verification of the high-speed responsivity in the NIR region, devices with different PACz layers were evaluated under 850-nm illumination, the standard NIR wavelength for high-speed data communication45. The J–V characteristics measured under 102 mW/cm2 of 850-nm illumination showed no major performance degradation compared to those obtained under 1-Sun conditions (Figs. 1g and 2a). Variations in the dark current density suggest that the 3-Br-4PACz sample could detect lower light intensities more effectively than the other samples.

Device performance is compared based on (a–d) PACz material variation and (e–h) active area scaling (based on 3-Br-4PACz) under 850 nm LED illumination. a J–V characteristics under 102 mW/cm2 light intensity, illuminance and in the dark. b Linear dynamic range (LDR) and dark current density (dashed line) at −0.25 V bias. c Normalized frequency response with different PACz interfacial layers. d Transient response measurement at 100 kHz light modulation. e Current-voltage (I–V characteristics under 102 mW/cm2 and in the dark for five different device areas (red: 4 mm2, orange: 1 mm2, green: 0.25 mm2, blue: 0.04 mm2, and purple: 0.01 mm2). f LDR measured at −0.25 V bias. g Normalized frequency response with varying device areas. h Transient response at 100 kHz with varying device areas.

As shown in Fig. 2b, the linear dynamic response was analyzed under light intensities ranging from 10−3 to 102 mW/cm2 at −0.25 V bias, based on the J–V characteristics in Supplementary Fig. 14. Although all four devices exhibited an effective dynamic range of 100 dB under actual experiments, the 3-Br-4PACz sample showed the highest linear dynamic range (LDR) of 168 dB when calculated based on the dark current baseline. The LDR values derived from the dark current for the pristine, 2PACz, and 3-Br-4PACz samples were 151, 147, and 162 dB, respectively. These results reveal that the 3-Br-4PACz device operates efficiently over a broad dynamic range of NIR illumination, with effective photoelectric conversion and minimal leakage current.

To assess the high-speed data reception performance under NIR illumination, frequency response (up to 10 MHz, the compliance limit of the measurement setup) and response time (at 100 kHz of pulsed light) measurements were conducted, as shown in Fig. 2c and d. Benefiting from its high carrier mobility, the 3-Br-4PACz device exhibited the highest f−3dB and fastest response times among all tested samples. As shown in Fig. 2c, only the 3-Br-4PACz sample achieved an f−3dB of 1.06 MHz, whereas the other samples were limited to response frequencies in the few hundred kHz range, with an effective device area of 4 mm2. Notably, to the best of our knowledge, achieving 1 MHz operation solely by introducing a 3-Br-4PACz layer at the BHJ/HTL interface—without modifying the photoactive layer—has not been previously reported.

Additionally, the rise time (τr) and fall time (τf) were measured under a 100-kHz light pulse (Fig. 2d), the values of which are summarized in Supplementary Table 6. The 3-Br-4PACz sample exhibited the shortest response times, with τr = 777.0 ns and τf = 751.6 ns, whereas the pristine, 2PACz, and 3,6-Br-4PACz samples exhibited considerably longer τr values (1435.7, 1598.9, and 897.3 ns, respectively) and τf values (1062.1, 1252.3, and 814.4 ns, respectively). These results confirm the high suitability of 3-Br-4PACz in high-speed NIR wireless communication applications.

Beyond the interfacial modulation introduced by PACz, minimizing the active area of OPDs is also critical for reducing junction capacitance. Since the device capacitance scales down with the active area, decreasing the lateral dimensions effectively lowers the resistance–capacitance time constant (tRC), thereby enhancing the temporal response. The f−3dB of the device is fundamentally limited by the slower of two processes: the tRC or the carrier transit time (τ), This relationship can be expressed as46:

where tRC = RC, with R representing the total series resistance, including both the intrinsic resistance of the device and contributions from the external circuitry and C denoting the total capacitance, which includes both intrinsic and parasitic components introduced by the measurement setup. The carrier transit time τ is primarily governed by the intrinsic properties of the photoactive layer but can also be influenced by interfacial effects such as those induced by PACz. Importantly, when the intrinsic device resistance is much smaller than the external circuit resistance (e.g., 50 Ω), the total resistance R becomes dominated by the external load, thereby limiting the response speed. While reducing the thickness of the photoactive layer can improve the frequency response by decreasing both τ and R, this approach introduces trade-offs, including reduced light absorption efficiency and increased leakage current47. Therefore, under a fixed active layer thickness, reducing the device area remains an effective strategy to lower the capacitance, decrease the tRC, and enhance the temporal response of the device.

To determine the minimum device size capable of enhancing the f−3dB without compromising the detection ability, 3-Br-4PACz samples were evaluated with five different active areas—that is, 4, 1, 0.25, 0.04, and 0.01 mm2. Figure 2e shows the current–voltage (I–V) characteristics of the devices with varying active areas under 102 mW/cm2 of 850-nm illumination and dark conditions. A systematic decrease in total current could be observed with decreasing active area, primarily owing to the reduced optical absorption within the device. To further understand the dependence of the photocurrent on the optical power, Fig. 2f presents the photocurrent response as a function of L, as derived from the measurements shown in Supplementary Fig. 15. As the active area decreases, the total photocurrent scales accordingly due to reduced optical absorption. Under high-intensity illumination, however, a more pronounced reduction in photocurrent is observed, which reflects limitations in charge extraction. When the rate of photogenerated carriers exceeds the extraction capacity, space-charge accumulation and internal electric field screening can occur, thereby suppressing carrier transport and leading to photocurrent saturation48. Consequently, the 0.01-mm2 device exhibited an α value of 0.880, in contrast to the 0.943 value for the 4-mm2 device. The charge transport in the smaller devices could also have been influenced by the increased series resistance and a more nonuniform carrier distribution. Within the photocurrent-dominant regime—where the signal remained sufficiently above the dark current level—the 0.01-mm2 device maintained a usable detection performance, despite exhibiting a slightly reduced photoresponse compared to the 4-mm2 device. The smaller device area led to a reduced capacitance, thereby minimizing the tRC—a critical advantage for high-speed photodetection. These results demonstrated that reducing the device area effectively improved the response speed while maintaining detection capability, with 0.01 mm2 being identified as the optimal minimum size. However, further miniaturization beyond this point is constrained because the reduced absorption area lowers the photocurrent and signal-to-noise ratio, thereby limiting practical applicability despite the faster intrinsic response49.

Figure 2g demonstrates the enhancement of the frequency response with decreasing device area, confirming the expected increase in f−3dB. As the device area decreased from 4 to 0.01 mm2, f−3dB increased from 1.06 to 3.04 MHz owing to the sequential reduction in C. Similarly, as summarized in Supplementary Table 7, both τr and τf decreased with device area reduction, with their respective response times extracted from the time-resolved photocurrent transients shown in Fig. 2h. Specifically, for the 4-mm2 device, τr and τf were 777.0 and 751.6 ns, respectively, whereas for the 0.01-mm2 device, they decreased to 333.45 and 313.81 ns, respectively. These results demonstrated that reducing the device area effectively improved the response speed while maintaining detection capability, with 0.01 mm2 being identified as the optimal minimum size.

Device performance under mechanical deformation in NIR conditions

To realize high-speed wireless communication on the skin, the mechanical reliability of ultraflexible NIR-OPDs must be systematically evaluated under dynamic deformation. Wrinkle-scale bending imposes stringent requirements; this includes the incorporation of soft materials, stable electrical coupling between functional layers, and reliable charge transport to ensure consistent optoelectronic performance (despite variations in the effective light-absorbing area under mechanical deformation). Additionally, intimate skin conformity—facilitated by an ultrathin device architecture with reduced flexural rigidity— helps ensure stable signal acquisition by reducing motion-induced artifacts and minimizing mechanical decoupling over time.

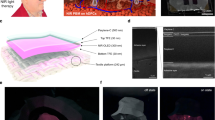

For ultraflexible device fabrication and mechanical deformation testing, NIR-OPDs were constructed on a Parylene-C/SU-8 substrate supported by a glass substrate and encapsulated by the 1-µm-thick Parylene-C layer. After gentle lamination onto a pre-stretched acrylic elastomer (VBH 4910, 3 M), the freestanding devices were detached and transferred onto a 200% pre-stretched polymeric elastomer. The devices then underwent repeated compression and relaxation cycles, released to the “100%-strained” (33% compressed) and “0%-strained” (66% compressed) states, as shown in Fig. 3a. Confocal microscopy (Fig. 3b) revealed multiple wrinkles on the device surface, whereas SEM imaging (Fig. 3c) confirmed wavy wrinkles with a bending radius of 4.90 μm under 33% compression. The formation of fine wrinkles suggested that the device exhibited sufficient mechanical adaptability to conform to natural skin wrinkles50, enabling stable operation under dynamic conditions.

a Image of the ultraflexible OPD under tensile (compressive) strain. b Confocal microscopy and c scanning electron microscopy images of the device under 100% strain. d–f Device performance comparison before and after peeling from the supporting glass substrate. d J–V characteristics under NIR illumination (solid line) and dark (dashed line), e spectral EQE (solid line) and responsivity (dashed line), and f specific detectivity D*. g Decay profile of the charge current after turn-off of the irradiation light. Inset graph shows the dependence of the number of RCs on the carrier mobility. h VOC and JSC variations with tensile strain variations. i Transient response characteristics under varying tensile strain from 0 to 200%. Inset shows the measured rise (τr) and fall (τf) times with different tensile strain. j Mechanical durability test under repeated 33% compressive strain for 1000 cycles.

The J–V characteristics under 1-Sun illumination and dark conditions (Fig. 3d) show no major differences before and after delamination, indicating that the OPD remained well-positioned near the neutral plane with 1-µm-thick Parylene-C encapsulation, minimizing the mechanical strain during delamination. Consequently, both JSC and the VOC remained unchanged. Similarly, the spectral EQE and responsivity across the 300–1000 nm wavelength range exhibited consistent values before and after delamination. At 850 nm, the peeled-off device exhibited an EQE of 72.5% and a responsivity of 0.49 A/W (Fig. 3e). As shown in Fig. 3f, the D*Dark remained above 1014 Jones at 850 nm before and after delamination. This stability could be attributed to preserving the responsivity and suppressing the dark current, indicating that the delamination process did not compromise the charge extraction efficiency. Transient photocurrent measurements (Fig. 3g) further support this conclusion, revealing minimal change in the charge carrier dynamics before and after delamination. The charge decay times were 2.93 μs before and 3.01 μs after peeling-off, and the extracted carrier mobilities were 3.84 × 10−5 and 3.74 × 10−5 cm2/V·s, respectively, indicating that the delamination process did not adversely affect the charge transport properties.

To further assess the electrical stability under mechanical deformation, the J–V characteristics were measured under sequential inward (compressive) and outward (tensile) deformation, with the 25% tensile strain step (Fig. 3h). During tensile strain, JSC decreased owing to the reduction in the effective light-absorbing area, whereas VOC remained unchanged throughout the deformation process. This indicated that the nanoscale morphology and charge extraction ability of the device were preserved despite the mechanical strain.

The frequency response (Fig. 3i) and response time under 100-kHz-pulsed light conditions (inset of Fig. 3i) were evaluated under tensile strain variations from 200 to 0% in 50% decrements. The reduction in f−3dB under mechanical deformation primarily stemmed from the diminished effective photoactive area, as the compressive strain created shaded regions that prevented complete light absorption. This geometric constraint increased the tRC through elevated series resistance. Despite these effects, the devices maintain remarkable frequency response stability, preserving f−3dB within the 1-MHz range even at maximum 66% compression (0% tensile strain). Only devices with an area of 0.01 mm2 sustained this high response rate across all strain states, whereas larger-area devices exhibited similar performance only under the uncompressed state (Supplementary Fig. 16). Although f−3dB decreased to one-third of its value at 200% tensile strain, the measured rise and fall times under a 100 kHz light pulse remained practically unchanged, indicating the minimal impact of the mechanical deformation on the dynamic performance. Notably, a similar trend in frequency response to L variations (Supplementary Fig. 17) suggests that the reduction in f−3dB during compression resulted from the decreased incident L. The reduced photon flux lowered the carrier density and increased the resistance, resulting in longer transit times and a slight increase in the tRC, limiting the high-frequency response48. In addition to these geometric effects, the incorporation of 3-Br-4PACz further contributed to maintaining stable performance by suppressing interfacial recombination and stabilizing charge extraction pathways under strain, thereby minimizing electrical degradation despite mechanical deformation

Evaluating long-term stability under continuous mechanical deformation is crucial for ensuring the reliability of ultraflexible, freestanding NIR-OPDs in practical applications. To evaluate the mechanical durability under repeated deformation, the device was subjected to 1,000 cycles of 100% tensile strain (33% compression), as shown in Fig. 3j. Even after prolonged mechanical stress, no major degradation in JSC and VOC was evident, confirming excellent mechanical resilience and operational stability. This mechanical resilience, along with stable electrical performance and frequency response under cyclic deformation, highlights the potential of the device for skin-attachable NIR wireless communication receivers.

Angle-independent, long-range wireless NIR communication on skin

Building on the results presented in Figs. 1–3—which demonstrate the enhanced charge transport enabled by the PACz layer, high-efficiency and rapid NIR photoresponse achieved through the optimized effective area design and maximized skin conformability through an ultrathin device architecture—we explored the feasibility of using the device for NIR wireless communication on the skin. As shown in Fig. 4a, the ultraflexible OPD was integrated into a system that received high-speed pulsed NIR signals carrying voice data and converted them into audible sound. The experimental setup for audio data transmission via pulsed light is detailed in Supplementary Fig. 18. By conformally adhering to the curved surface of the index fingertip (Fig. 4b), the device ensured stable skin contact and enabled angle-independent operation. Leveraging its high f−3dB and high D*, we developed a skin-attachable wireless communication system capable of long-distance optical transmission.

a Schematic illustration and b photograph of a skin-conformal NIR wireless receiver attached to human skin. c Schematic of data transmission under varying LED incidence angles for devices placed on glass and skin. d Eye diagram and e output photocurrent amplitude (top), bit-error-rate (BER, bottom) as a function of LED angle. f Schematic image (left) and real photograph image under room light (right, top) and dark (right, bottom) condition for the demonstration of long-distance NIR wireless communication using an 850-nm laser diode, with the device attached to skin surface. g Photocurrent amplitude and h corresponding Fast Fourier transform amplitude versus distance under bright (red) and dark (blue) conditions.

As the ultraflexible NIR-OPD conformed to the natural curvature of the skin upon attachment, it received incident light from a broader range of angles, mimicking a hemispherical light reception profile. This allowed enhanced data reception, making it more suitable for wide-field vision and object positioning applications51. Figure 4c compares the two scenarios, highlighting the enhanced angular responsiveness of the skin-attached device. While a flat device on glass struggles to detect high-angle incident light, the skin-attached device efficiently captures light from a wider angular range, up to 90°. To evaluate its performance, a 1-Mbps PN7 signal—a standard pseudo-random binary sequence for communication testing—was transmitted to a 0.01 mm2 size 3-Br-4PACz sample using a light-emitting diode (LED), and the resulting eye diagrams were analyzed to assess the bit-error rate (BER) of the OPD52. As shown in Fig. 4d, the eye diagrams remained similar for both configurations at angles below 30°, but at angles exceeding 60°, the central opening of the eye diagram shrank considerably for the on-glass device compared to that of the on-skin device. Notably, at 90°, the on-glass device failed to generate an eye diagram owing to communication failure, whereas the on-skin device successfully reconstructed a clear eye diagram, indicative of reliable data reception. The signal amplitude (Fig. 4e, top) and bit-error rate (BER; Fig. 4e, bottom) of each device were also systematically evaluated under varying incident angles. Signal amplitude reflects the strength of the detected optical input, whereas the BER quantifies data transmission fidelity. In this study, transmission accuracy was assessed by comparing the received bitstream with the original data across different angles of illumination. This angular dependence is crucial for assessing the directional robustness of photodetectors in practical optical communication systems. The skin-mounted OPD retained over 60% of its initial photocurrent amplitude across incident angles ranging from 0° to 90°, demonstrating high angular tolerance. In contrast, the on-glass device exhibited a gradual decline in photocurrent with increasing angle, primarily due to diminished absorption under oblique illumination. Importantly, the skin-mounted device maintained a bit-error rate (BER) below the forward error correction (FEC) threshold across all tested angles, enabling stable and reliable data transmission under wide angular conditions. By comparison, the on-glass device showed a sharp rise in BER beyond 60°, surpassing the FEC limit with communication failure. These findings establish the ultraflexible NIR-OPD as a high-performance wireless communication receiver capable of maintaining functionality across a broad range of incidence angles. To demonstrate its angle-insensitive signal reception ability, an experiment was performed in which an ultraflexible NIR-OPD was conformally attached to a human fingertip to receive classical music transmitted from a near-infrared LED array. The finger with the integrated device was operated within the region irradiated by the array. As shown in Supplementary Movie 1 (dark condition, background room light intensity: 1.35 mW/cm2) and Supplementary Movie 2 (500 lux illuminance, background room light intensity: 2.16 mW/cm2), the ultraflexible NIR-OPD consistently received music signals from the LED without interruption, even during finger stretching, rotation, and shaking while mounted on the hand.

As a final demonstration of long-range wireless communication, Fig. 4f presents a skin-attached NIR communication system evaluated across a full 100-m indoor distance, where an 850-nm laser diode transmitted signals to an OPD positioned at the opposite end of a hallway. Notably, this distance exceeded the typical operating range of conventional short-range wireless technologies in indoor settings, thereby demonstrating the potential of optical wireless systems for extended-range communication in constrained environments. To evaluate compatibility with human auditory perception, an NIR-based optical signal sweeping from 20 Hz to 20 kHz was generated, corresponding to the full range of human hearing (Fig. 4g, top). We opted for a 4 mm2 3-Br-4PACz device, rather than the 0.01 mm2 sample, in order to obtain stronger photocurrent output and more stable audio signal reception in a practical wireless setup. The larger-area device, while slower than the smaller counterpart, still provided sufficiently fast response for the tested 1-Mbps PN7 transmission, as the maximum audio frequency lies well below the f₋3dB threshold. The middle and bottom traces in Fig. 4g show the audio signals received by the on-skin device under dark conditions at a distance of 100 m and under bright ambient lighting (80 m at 500 lux), respectively. These results confirm the robustness of the optical audio transmission under varying environmental conditions. The reduced transmission distance under bright conditions could be attributed to optical interference from the fluorescent lighting, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 19. Nevertheless, even under 500 lux ambient illuminance at a distance of 80 m, the received signal accurately reproduced the full frequency sweep of the original audio (20 Hz–20 kHz), indicating that the skin-mounted OPD maintained high-fidelity detection despite the strong ambient light. These results highlight the ability of the device for reliable long-range NIR wireless communication, even in optically noisy environments. Fast Fourier transform (FFT) analysis (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 20) showed that while the signal amplitudes remained comparable under both dark and bright conditions, ambient illumination (e.g., hallway lighting) introduced elevated background noise, which reduced the effective signal-to-noise ratio. At a distance of 80 m under 500 lux illumination, the FFT spectra preserved the peak frequencies of the original audio, indicating that essential frequency components remained intact despite optical interference. The transmission failure evident at 100 m under bright conditions is not attributed to limited photodetector sensitivity. Rather, elevated ambient light increased the baseline noise level by approximately 5 dB compared to that under the dark condition, obscuring the signal53 (Supplementary Fig. 21). These results suggest that the degradation in audio transmission performance under bright conditions was primarily due to the increased background noise rather than reduced detection capability. The robustness of long-distance audio communication is further demonstrated in Supplementary Movies 3, 4. Supplementary Movie 3 shows successful music transmission over 100 m in the dark (background room light intensity: 1.35 mW/cm2), while Supplementary Movie 4 demonstrates stable performance at 80 m under 500 lux illuminances (background room light intensity: 2.16 mW/cm2), despite the presence of considerable ambient optical noise.

Discussion

This study demonstrated the development of skin-conformal, ultraflexible NIR-OPDs that enabled MHz-speed wireless communication with wide angular tolerance and extended long-range operation. Incorporating 3-Br-4PACz at the PM6:Y6/MoO3 interface optimized energy level alignment and promoted efficient charge extraction, thereby improving the NIR detection ability—1.56 × 1014 Jones of D*Dark and 0.84 × 1014 Jones of D*NEP at 790 nm—by suppressing recombination and enhancing the overall device performance. Moreover, by minimizing the device area, the device achieved high-speed operation with a f−3dB of 3.04 MHz. Beyond their high-frequency performance, the devices exhibited remarkable mechanical resilience, maintaining stable operation under 66% compression and adhering conformally to skin with micrometer-scale wrinkle-level curvature. Unlike intrinsically stretchable devices, our ultrathin OPDs are not designed to elongate under tensile strain; instead, their mechanical robustness stems from conformal adhesion to curved skin surfaces, which ensures reliable operation during body movements without requiring device stretching. We focused on cyclic compression testing because it imposes substantial mechanical stress while avoiding fracture of the brittle ITO electrodes, which are known to limit durability under more severe tensile or bending conditions. Within this range, the devices maintained stable operation over 1000 cycles. Importantly, the skin-mounted NIR-OPDs reliably detected MHz-scale signals across a full angular range (0–90°) and sustained signal reception over distances of up to 100 m. This long-range performance arises not only from the external illumination conditions but also from the intrinsic capability of the devices. The low-noise current and high D* reduce the minimum detectable optical power, enabling stable operation even when the received signal approaches the level of ambient background light. Under dark conditions, the NIR-OPDs can reliably detect light pulses as weak as ~1 mW/cm2, which highlights their excellent signal-to-noise ratio and intrinsic sensitivity. Further improvements in long-term stability could be achieved by replacing ITO with thinner or softer compliant electrodes, which represents a promising direction for extending durability in future device generations54. These capabilities are particularly advantageous for practical scenarios such as wearable healthcare monitoring and human–machine interfaces, where stable, long-range, and body-conformal communication is essential. Such a combination of angular independence, long-range communication, and mechanical adaptability marks a balanced advance, realizing a level of integration not previously achieved in NIR-OPDs. This study thus paves the way toward skin-integrated wireless communication platforms that complement conventional free-space NIR systems and expand their applicability to real-world wearable and biomedical technologies.

Methods

Materials

Zinc oxide nanoparticle (ZnO, NCT-10) was purchased from Nano Clean Technology. Poly[[4,8-bis[5-(2-ethylhexyl)-4-fluoro-2-thienyl]benzo-[1,2-b:4,5-b’]dithiophene-2,6-diyl]-2,5-thiophenediyl-[5,7-bis(2-ethylhexyl)-4,8-dioxo-4H,8H-benzo[1,2-c:4,5-c’]-dithiophene-1,3-diyl]-2,5-thiophenediyl] (PM6) and 2,2’-((2Z,2’Z)-((12,13-Bis(2-ethylhexyl)-3,9-diundecyl-12,13-dihydro-[1,2,5]thiadiazolo[3,4-e]thieno-[2”,3”:4’,5’]thieno[2’,3’:4,5]pyrrolo[3,2-g]thieno-[2’,3’:4,5]thieno[3,2-b]indole-2,10-diyl)bis(methanylylidene))-bis(5,6-difluoro-3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-indene-2,1-diylidene))dimalononitrile (Y6) were purchased from Derthon. 2PACz was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry CO., LTD, while 3-Br-4PACz and 3,6-Br-4PACz were purchased from innoproject CO., LTD.

Fabrication and characterization of organic photodiodes

To fabricate a skin-attachable organic NIR wireless communication receiver, glass substrates were sequentially cleaned using detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropyl alcohol via ultrasonic treatment for 5 min each, followed by nitrogen blow-drying. Residual surface chemicals were removed through oxygen plasma treatment for 10 min. A fluorinated polymer blended solution (Novec 1700:7100, 1:10 vol%, 3MTM) was spin-coated onto the cleaned glass substrate at 2000 rpm for 60 s. Subsequently, a 1-µm-thick Parylene-C film was deposited onto the fluorinated polymer/glass substrate using chemical vapor deposition (CVD). The substrates were thermally annealed at 120 °C in ambient conditions for 1 h. A 600-nm-thick epoxy layer (SU-8 3005, MicroChem) was spin-coated at 5000 rpm for 60 s to planarize the Parylene-C film. This was annealed at 95 °C for 2.5 min, exposed to ultraviolet light (λ ≈ 365 nm) for 4 min, and subsequently annealed at 150 °C in a nitrogen atmosphere for 1 h. A 100-nm-thick indium tin oxide (ITO) layer was sputtered without substrate heating, patterned through photolithography, and etched using a wet etching process. A ZnO nanoparticle layer was spin-coated at 3000 rpm for 30 s and annealed at 120 °C for 30 min. The PM6:Y6 mixed solution was then deposited inside an argon glove box at 3000 rpm for 30 s, followed by an annealing at 110 °C for 10 min. After cooling the device to below 40 °C, PACz-based materials dissolved in methanol were spin-coated at 3000 rpm for 30 s and annealed at 100 °C for 10 min. Finally, MoO3 (5 nm) and Ag (100 nm) layers were sequentially deposited via thermal evaporation under high vacuum (<2.0 × 10−6 Torr). To form a passivation layer on the top of the device, a 1-µm-thick Parylene-C passivation layer was deposited via CVD once again.

Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS)

ToF-SIMS analysis was performed using a TOF.SIMS 5 instrument (ION-TOF, Germany) in negative mode to investigate the surface composition and depth profiling of the sample. The primary ion beam consisted of Bi⁺ ions (30 keV, 1 pA) and Cs⁺ ions (1 keV, 75 nA) were used for the sputtering/etching process. The analysis area was set to 100 × 100 μm2, and the etching area was set to 500 × 500 μm2 to ensure accurate depth profiling. A flood gun was used to maintain charge neutrality during the analysis to prevent surface charging. Depth profiling was performed by sequentially sputtering the sample at a controlled etching rate.

Dipole moment analysis

DFT calculations were performed to determine the dipole moments of the molecules using the Avogadro software for molecular structure preparation and ORCA (Version 5.0.1) for electronic structure analysis. The exchange-correlation functional B3LYP, a hybrid functional known for its accuracy in predicting molecular properties, was used. The def2-TZVP basis set was employed to ensure high accuracy in the calculations. The convergence criteria were set to “TightSCF” to achieve precise solutions for the electronic structure. The dipole moment μ of the molecule was computed using the following equation:

qi is the partial charge on the ith atom, ri is the position vector of the ith atom relative to the center of mass of the molecule. The B3LYP density functional method provides a balanced approach for electronic structure calculations, and the def2-TZVP basis set offers a detailed representation of the molecular orbitals to capture subtle interactions. The results of the DFT calculations were analyzed to understand the electronic distribution, polarizability, and overall dipole moment of the molecules in their optimized geometries.

Surface characterization

The contact angle was measured using the seo Contact Angle Analyzer Phoenix300 equipment. The conditions of PM6, Y6, ZnO, MoO3 single sheet and MoO3/2PACz, MoO3/3-Br-4PACz, MoO3/3,6-Br-4PACz, MoO3 were set, and the contact angle was measured using distilled water (polar) and dichloromethane (nonpolar) on the solid surface. The surface energy through the contact angle was calculated using the Owens-Wendt–Rabel–Kaelble (OWRK) equation below.

In the above equation, γS represents the surface energy, γSd is the dispersion component of the surface, and γSp is the polar component of the surface. γSd and γSp were calculated using

θ is the contact angle, \({\gamma }_{{ld}}\) and \({\gamma }_{{lp}}\) are the dispersion and polar components of the liquid. The \({\gamma }_{{ld}}\) was 51 for distilled water and 18.4 for dichloromethane, while the \({\gamma }_{{lp}}\) was 21.8 for distilled water and 2.3 for dichloromethane.

Carbazole-based phosphonic acid (PACz) material energy bandgap analysis

The energy bandgap of the PACz materials were measured by Tauc plot. The optical absorption coefficient (α) was first derived from the measured UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectra using the relation:

where A is the absorbance, and d is the thickness of the material. The Tauc relation for allowed direct and indirect transitions is expressed as:

where \(h\upsilon\) is the photon energy, Eg is the optical bandgap, B is a proportionality constant, and n depends on the electronic transition type (n = 2 for direct transitions and n = 1/2 for indirect transitions). To construct the Tauc plot, (αhν) was plotted as a function of photon energy, and the linear portion of the curve was extrapolated to intersect the photon energy hν axis. The intersection point corresponds to the optical bandgap Eg of the material.

Energy level analysis

Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) measurements were conducted using a Nexsa (Thermo Fisher) instrument. Work functions (Φ) were determined based on the following relations:

where hν is the photon energy (21.22 eV in this experiment Evac is the vacuum level, and EF is the Fermi level. Eg was derived from UV-Vis spectra, and the lowest unoccupied molecule orbital (LUMO) level was estimated by combining the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and Eg. Thin films of ZnO, PM6, Y6, 2PACz, 3Br-4PACz, 3,6-Br-4PACz, and MoO3 were analyzed for these parameters.

Atomic force microscopy analysis

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was conducted using a Park Systems instrument in non-contact mode. The AFM measurements were performed under ambient conditions to characterize the surface topography and phase distribution of thin films. The scan area was set to 2.5 × 2.5 μm2, and the resolution was optimized for detailed imaging. Height and phase images were acquired simultaneously to investigate surface roughness and material distribution. The images were processed and analyzed using Park Systems’ proprietary XEI software to calculate surface roughness parameters such as root-mean-square (RMS) roughness

Electrical characterization of organic NIR wireless communication receiver

J−V curves were obtained using a semiconductor analyzer (Keithley 2400) under dark conditions and under 1-Sun illuminance (AM 1.5G, 100 mW/cm2. The intensity was calibrated using a silicon reference diode.) or 850 nm LED illuminance (TSHG6210 IR emitter DH 850-nm). The external quantum efficiency (EQE) data were measured using a Spectral QE Measurement System (TNE TECH CO., LTD, Korea). The EQE values were obtained as a function of wavelength in the range of 300–1000 nm using a 300 W Xe lamp as the light source, and the calibration was performed using a Si photodiode in 300–960 nm wavelength range, and GaAs photodiode in 960 ~ 1000 nm wavelength range. The time-delayed collection field (TDCF) method was measured by a photoresponse system (TNE TECH CO., LTD, Korea) supported by NFEC (No. NFEC-2025-02-303576), illuminating the 625 nm light pulse on the device and plotting the charge current variation in the time domain. The number of remaining charge carriers was calculated by the program of the photoresponse system. The spectral noise current was measured by a dynamic signal analyzer (35670A, Alignment) connected to the device through a preamplifier (SR 570). The detectivity based on the noise-equivalent power (NEP) is D*NEP = (A Δf)0.5R/inoise, where R is the responsivity, A is the effective photodetector area for the devices, Δf is the detection bandwidth (set to 1 Hz in this experiment), and inoise is the noise current measured under dark conditions.

Dynamic response characterization of an organic NIR wireless communication receiver

The frequency response, response times, and eye diagram were measured by a digital oscilloscope (MSO64B, Tektronix). A 3-mm-diameter (larger than the OPD photoactive area) 850 nm LED (VSLY3850, VISHAY) connected with a function generator (33600 A, Keysight) was used as a light source. The output signal extracted from the organic NIR wireless communication receiver was amplified by a low-noise transimpedance amplifier (DHPCA-100, © FEMTO). When measuring both frequency response and response times, the frequency was modulated by the function generator. When measuring the eye diagram, the pulse was set as a pseudo-random binary signal (PRBS) PN7 and tilted the angle between the LED and the OPD from 0–90°.

Mechanical property measurements

Freestanding ultraflexible organic photodiodes (OPDs) were laminated onto pre-stretched acrylic elastomer substrates (VHB Y-4905J, 3MTM) prior to measurement. To ensure accurate electrical signal recording, gold external wirings were employed as the electrical contact for the freestanding devices. The gold wirings were fabricated by depositing 5/450 nm patterned Cr/Au layers onto 12.5-µm-thick polyimide films using a shadow mask. Electrical contact between the devices and the gold wiring was established via electrically conductive adhesive tape (ECATT 9703, 3MTM). The gold wirings were further connected to the measurement equipment using alligator clips. The degree of substrate stretching was controlled using a custom-built screw machine, with measurements performed under ambient conditions. A ruler was employed to precisely monitor the stretching deformation. Electrical data during the stretching tests were recorded using a Keithley 2400 sourcemeter.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within this article and its Supporting Information. Additional data is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Zhang, Y. et al. High-speed transition-metal dichalcogenides based Schottky photodiodes for visible and infrared light communication. ACS Nano 16, 19187–19198 (2022).

Chow, P. C. Y. & Someya, T. Organic photodetectors for next-generation wearable electronics. Adv. Mater. 32, 1902045 (2020).

Clark, J. & Lanzani, G. Organic photonics for communications. Nat. Photonics 4, 438–446 (2010).

Huang, J. et al. A high-performance solution-processed organic photodetector for near-infrared sensing. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906027 (2020).

Eun, H. J. et al. Strain-durable dark current in near-infrared organic photodetectors for skin-conformal photoplethysmographic sensors. iScience 25, 104194 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Semitransparent near-infrared organic photodetectors: flexible, large-area, and physical-vapor-deposited for versatile advanced optical applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2313689 (2024).

Xiong, S. et al. Waterproof and ultraflexible organic photovoltaics with improved interface adhesion. Nat. Commun. 15, 681 (2024).

Du, B. et al. A water-resistant, ultrathin, conformable organic photodetector for vital sign monitoring. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp2679 (2024).

Lee, H. et al. Stretchable organic optoelectronic devices: design of materials, structures, and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 146, 100631 (2021).

An, C. et al. Efficient near-infrared organic light-emitting diodes with emission peak above 900 nm enabled by enhanced photoluminescence quantum yields and out-coupling efficiencies. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2313353 (2024).

Chen, G. et al. Advanced near-infrared light for monitoring and modulating the spatiotemporal dynamics of cell functions in living systems. Adv. Sci. 7, 1903783 (2020).

Shetty, S., Smitha, A. B. & Rai, R. Modeling and Optimization of Optical Communication Networks. (eds Chandra S., Rathishchandra R. G., K.V.S.S.S.S. Sairam, and Ashish S.) Ch. 20 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2023).

Cao, Z. et al. Reconfigurable beam system for non-line-of-sight free-space optical communication. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 69 (2019).

Wang, C., Zhang, X. & Hu, W. Organic photodiodes and phototransistors toward infrared detection: materials, devices, and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 653–670 (2020).

Jang, W., Luong, H. M., Kim, M. S., Nguyen, T.-Q. & Wang, D. H. Enhancing detection frequency and reducing noise through continuous structures via release-controlled transfer toward light-based wireless communication. Adv. Mater. 36, 2406316 (2024).

Lou, Z. et al. Near-infrared organic photodetectors toward skin-integrated photoplethysmography-electrocardiography multimodal sensing system. Adv. Sci. 10, 2304174 (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. High-speed flexible near-infrared organic photodiode for optical communication. Natl Sci. Rev. 11, nwad311 (2024).

Xia, Y. et al. High-speed flexible near-infrared organic photodetectors for self-powered optical integrated sensing and communications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2412813 (2025).

Kim, Y. et al. A strong regioregularity effect in self-organizing conjugated polymer films and high-efficiency polythiophene:fullerene solar cells. Nat. Mater. 5, 197–203 (2006).

Yao, J. et al. Cathode engineering with perylene-diimide interlayer enabling over 17% efficiency single-junction organic solar cells. Nat. Commun. 11, 2726 (2020).

Park, S. et al. Ultraflexible near-infrared organic photodetectors for conformal photoplethysmogram sensors. Adv. Mater. 30, 1802359 (2018).

Weng, K. et al. Optimized active layer morphology toward efficient and polymer batch insensitive organic solar cells. Nat. Commun. 11, 2855 (2020).

Han, P. & Zhang, Y. Recent advances in carbazole-based self-assembled monolayer for solution-processed optoelectronic devices. Adv. Mater. 36, 2405630 (2024).

Klein, J. et al. Limitations of the Tauc plot method. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2304523 (2023).

Suganuma, N. et al. High speed response organic photodetectors with cascade buffer layers. Adv. Electron. Mater. 8, 2100539 (2022).

Lin, Y. et al. Self-assembled monolayer enables hole transport layer-free organic solar cells with 18% efficiency and improved operational stability. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 2935–2944 (2020).

Huang, L. et al. Vertical stratification engineering for organic bulk-heterojunction devices. ACS Nano 12, 4440–4452 (2018).

Bulliard, X. et al. Enhanced performance in polymer solar cells by surface energy control. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 4381–4387 (2010).

Kosco, J. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from organic semiconductor heterojunction nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 19, 559–565 (2020).

Lin, Y. et al. 18.73% efficient and stable inverted organic photovoltaics featuring a hybrid hole-extraction layer. Mater. Horiz. 10, 1292–1300 (2023).

Tang, H. et al. Interface engineering for highly efficient organic solar cells. Adv. Mater. 36, 2212236 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Charge injection engineering at organic/inorganic heterointerfaces for high-efficiency and fast-response perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 14, 6441 (2023).

Yu, X. et al. Self-assembled molecules with asymmetric backbone for highly stable binary organic solar cells with 19.7 % efficiency. Angew. Chem. 136, e202401518 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Asymmetric modification of carbazole based self-assembled monolayers by hybrid strategy for inverted perovskite solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202416188 (2025).

Chen, Q. et al. Effects of alkyl spacer length in carbazole-based self-assembled monolayer materials on molecular conformation and organic solar cell performance. Adv. Sci. 12, 2410277 (2025).

Jeong, S. et al. New ternary blend strategy based on a vertically self-assembled passivation layer enabling efficient and photostable inverted organic solar cells. Adv. Sci. 10, 2206802 (2023).

Kim, T. H. et al. Record indoor performance of organic photovoltaics with long-term stability enabled by self-assembled monolayer-based interface management. Nano Energy 112, 108429 (2023).

Ling, Z. et al. 20.5 % efficient ternary organic photovoltaics using an asymmetric small-molecular acceptor to manipulate intermolecular packing and reduce energy losses. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 163, 100922 (2025).

Xu, Y. et al. Ambient processable and stable all-polymer organic solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806747 (2019).

You, J. et al. A polymer tandem solar cell with 10.6% power conversion efficiency. Nat. Commun. 4, 1446 (2013).

Ma, X. et al. Identification of the origin of ultralow dark currents in organic photodiodes. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209598 (2023).

van Breemen, A. J. J. M. et al. A thin and flexible scanner for fingerprints and documents based on metal halide perovskites. Nat. Electron. 4, 818–826 (2021).

Bartesaghi, D. et al. Competition between recombination and extraction of free charges determines the fill factor of organic solar cells. Nat. Commun. 6, 7083 (2015).

Saggar, S. et al. Response speed of organic photodiodes as a function of incident optical intensity. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12, 2302916 (2024).

Osório, J. H. et al. Hollow-core fibers with reduced surface roughness and ultralow loss in the short-wavelength range. Nat. Commun. 14, 1146 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. High-performance filterless blue narrowband organic photodetectors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2308719 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Visible to near-infrared photodetection based on ternary organic heterojunctions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1808948 (2019).

Park, Y. et al. Skin-like low-noise elastomeric organic photodiodes. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj6565 (2021).

Zheng, J. et al. An ultrafast organic photodetector with low dark current for optical communication systems. ACS Photonics 10, 1382–1388 (2023).

Lee, G. et al. User-interactive thermotherapeutic electronic skin based on stretchable thermochromic strain sensor. Adv. Sci. 7, 2001184 (2020).

Feng, X. et al. Spray-coated perovskite hemispherical photodetector featuring narrow-band and wide-angle imaging. Nat. Commun. 13, 6106 (2022).

Wu, Y. et al. Tbps wide-field parallel optical wireless communications based on a metasurface beam splitter. Nat. Commun. 15, 7744 (2024).

Lee, G. H. et al. Light-mediated photomultiplication via cascade energy transfer in organic photodiode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2423993 (2025).

Lee, H. et al. Ultra-flexible semitransparent organic photovoltaics. Npj Flex. Electron. 7, 27 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) (Grant No. 2022R1A2C2007784, RS-2023-00213089, RS-2024-00403639, RS-2024-00411904, RS-2024-00403163, RS-2024-00411764, 2021M3H2A1038042, and IITP-2023-2020-0-01461). This work was funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea) (Grant No. P0017805, RS-2024-00417909, and RS-2022-00154781). This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. JP22K21343 and JP22H04949).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors contributed equally: J.-H.K., H.C., and K.F. S.P. conceived and designed the experiments. J.-H.K. and H.C. fabricated and characterized near-infrared organic photodiodes (NIR-OPDs). J.-H.K., H.C., and K.F. conducted electrical and mechanical properties measurements. J.-H.K., J.J., and K.F. conducted NIR wireless communication experiments and data analysis. H.C. and H.K. performed and interpreted DFT calculations, contact-angle measurements, and ToF-SIMS analysis. H.C., K.F., and H.K. conducted morphological characterization (AFM and SEM) and energy level alignment studies (UPS). J.H. synthesized PACz materials and supported material purity validation. J.-G.C., S.M.W., J.K., Y.H.J., J.H., and S.S. contributed to device fabrication scaling and experimental support. J.-H.K., H.C., K.F., and S.P. wrote the manuscript. J.-G.C., S.H.L., T.Y., S.M.W., J.K., Y.H.J., J.H., T.S., H.K., and S.J. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, JH., Choi, H., Fukuda, K. et al. Skin-conformal MHz-speed organic photodetectors for angle-free and long-range near-infrared communication. Nat Commun 16, 11041 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66649-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66649-0