Abstract

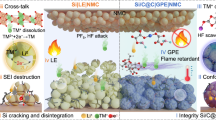

Silicon stands out as promising negative electrode for future lithium-ion batteries owing to its high specific capacity. However, drastic volume change during cycling results in significant loss of electronic/ionic conduction and poor cycling life, necessitating external stack pressure to confine volume expansion. In this work, we develop a gel polymer electrolyte by in situ co-polymerizing methyl methacrylate and 2-(3-(6-methyl-4-oxo-1,4-dihydropyrimidin-2-yl)ureido)ethyl methacrylate to enable pressure-free and energy-dense silicon-based lithium-ion batteries. Benefiting from the crosslinked polymer structure and self-healing property, the SiOx particles experience limited volume expansion and maintain robust interfacial contact with the gel electrolyte, leading to a capacity retention of 90.2% after 400 cycles (0.3 C, 500 mA g-1). Additionally, the gel electrolytes effectively supress electrode swelling and the formation of “dead silicon”, endowing 1000 cycles (0.5 C, 0.8 A) for Ah-scale silicon-based pouch cells free from external stack pressure. Such gel electrolytes also demonstrate safety superiority to conventional liquid electrolytes, which promotes the commercial viability of high-energy-density silicon-based batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Silicon and SiOx materials, with theoretical capacities of 3650 mAh g−1 and 1800 mAh g−1 respectively, are considered as promising negative electrodes for future high-energy-density batteries1,2,3,4,5. Additionally, the relatively high potential of Li-Si alloying process at 0.3 V (vs. Li/Li+) prevents lithium nucleation and dendrites formation, thereby avoiding lithium plating during fast charging and enhancing safety over graphite and lithium negative electrodes6,7. Unfortunately, silicon-based materials suffers from severe volume change during lithiation and de-lithiation8, resulting in uncontrollable solid-electrolyte-interphase (SEI) formation, rapid electrolyte consumption, loss of electronic and ionic conduction, the emergence of “dead silicon” and eventual electrode-level failure2,3,9,10. Numerous material-scale modifications on silicon have been reported over the years, such as carbonaceous coating11,12, polymer coating13,14, nanosizing15, and increasing electrode porosity16,17, etc. However, electrode engineering solely is inadequate to address the inherent challenges associated with liquid electrolytes, as liquid electrolytes can always penetrate into silicon particles with continuous consumption during cycling10. In this context, electrolyte additives such as fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC) have been widely used to improve the cycling life of Si-based negative electrodes18,19. Unfortunately, FEC also undergoes rapid consumption during cycling and poses severe risk in gas generation, leading to degradation in high temperature cycling and calendaring life20,21. As a result, developing new electrolyte systems for silicon-based negative electrodes with minimized volume change, long cycling life, low gas generation and high safety is in urgent need.

Solid-state electrolytes (SSEs) offer suppressed reactivity with Silicon and improved safety compared to conventional organic liquid electrolytes22,23. However, inorganic SSEs exhibit minor deformation and lack the flexibility to tolerate the volume changes, resulting in poor solid-solid contact with silicon negative electrodes24,25. Consequently, current all-solid-state batteries with silicon negative electrodes require high cell stacking pressure (50–150 MPa) to maintain close contact between electrodes and inorganic SSEs26,27,28, in which external pressure device is indispensable, unfortunately reducing overall energy density2,29. Notably, even for silicon-based battery with liquid electrolytes, external pressure is still essential to confine the volume change and ensure stable cycling30.

Compared to rigid ceramic SSEs, polymer-based gel electrolytes formed by in situ polymerization, also known as quasi-solid electrolytes, offer great flexibility and better interfacial contact with electrodes31. They also possess improved mechanical strength to restrict silicon’s volume change and maintain electrode integrity, preventing electrode pulverization and subsequent loss of electronic/ionic conduction23,32,33,34,35,36. Ether-based ring-opening polymerization (ROP) and acrylate-based radical polymerization remain predominantly employed in gel electrolyte synthesis due to their compatibility with battery manufacturing protocols. However, lithium salt-initiated ROP of cyclic ethers (e.g., tetrahydrofuran [THF] and 1,3-dioxolane [DOL]) exhibits poor controllability owing to either too rapid or too sluggish reaction kinetics37,38. Furthermore, the narrow electrochemical stability window (ESW) of ethers substantially restricts their applications in high-voltage positive electrodes. Consequently, acrylate monomers emerge as preferred candidates for in situ polymerization, offering both precise polymerization regulation and enhanced compatibility with high-voltage electrodes39. However, the widely used polyacrylate gel still faces problems including limited deformation, fragility, and loss of contact with electrode surface, especially in high-content silicon negative electrode where tremendous volume change occurs. High mechanical strength, deformation tolerance, and self-healing property are strongly desirable40,41,42.

In this work, an elastic quasi-solid electrolyte is prepared by in situ co-polymerizing methyl methacrylate (MMA) and 2-(3-(6-methyl-4-oxo-1,4-dihydropyrimidin-2-yl)ureido)ethyl methacrylate (UPyMA) in a carbonate-based electrolyte to enable pressure-free and high-loading Si-based pouch cells. As a comparison of liquid electrolyte (noted as LE), it is found that the quasi-solid electrolyte with 15 wt.% poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), which is noted as QSE, can indeed reduce the volume change of silicon negative electrodes and maintain electrode-scale integrity. However, the detachment of solid-solid interface and crack of PMMA gel still exists especially with high silicon content, leading to unsatisfactory performance. By replacing a certain amount of MMA with UpyMA, the electrolyte (noted as Upy-QSE) can form multiple Si-OH-X (X = N or O) hydrogen bonds with the terminal hydroxyl groups on silicon’s surface, as validated by the density functional theory (DFT) calculation and molecular dynamic (MD) simulation. Such multiple hydrogen bonds not only provide strong adhesion force with silicon surface but also maintain robust resilience to prevent electrolyte cracking throughout the cycling process, mitigating interface loss and ensuring robust Li+ transport. The mechanism analysis reveals that, compared to LE, the gel polymer can effectively confine electrode expansion, preserve the electrode structural integrity and reduce the generation of “dead silicon”, delivering high reversible capacity and long cycle life.

Consequently, Li||SiOx half cell (2.4 mAh cm–2) with Upy-QSE delivered a capacity of 1255 mAh g–1 after 400 cycles at 0.3 C/0.3 C (1 C = 1800 mA g–1) at room temperature (30 ± 1 °C), corresponding to 90.2% of initial capacity, and a 1.6 Ah SiOx@Gr (450 mAh g–1)||LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM811) pouch cell with Upy-QSE demonstrates capacity retention of 82.2% after 1000 cycles at 0.5 C/0.5 C at 30 °C. Notably, all the pouch cells with quasi-solid electrolytes are evaluated with no external stacking pressure, while those with liquid electrolyte suffer rapid capacity drop if no pressure is applied. Moreover, the gassing and high-temperature performance of Si-based pouch cells are notably improved, thanks to the presence of multiple amide groups in UpyMA units that effectively scavenge PF5 and HF generated from LiPF643,44. Lastly, the Ah pouch cell incorporating Upy-QSE also demonstrates reliable safety in nail-penetrating and thermal abusing tests, showcasing promising potential to be applied in commercial LIBs market.

Results

Properties of Upy-QSE and functions in Li||SiOx battery

The UpyMA monomer was synthesized based on a polyurea reaction formed by isocyanate and amide group (details can be seen in Methods). The 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of reactants 6-methylisocytosine and 2-isocyanatoethyl methacrylate are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a. The concurrent appearance of urea hydrogen (peak a, b) and C=C double bond Hydrogen (peak d, f) indicates the successful synthesis of UpyMA (Supplementary Fig. 1b), which is in accordance with previous reports45,46. After blending 3 wt.% UpyMA with 12 wt.% MMA in the electrolyte precursor and polymerizing with heat-treatment, the liquid precursor becomes transparent elastic gel (Supplementary Fig. 1d). The disappearance of C=C H peaks and linked methyl H peak in 1H NMR spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 1c) confirms the complete co-polymerization of methacrylate. Furthermore, the Upy-QSE demonstrates strong self-healing property (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

To better understand how Upy-QSE functions in the silicon-based battery, the failure mechanisms of silicon electrode at both particle and electrode levels are depicted in Fig.1a, b respectively. In conventional LE (Fig. 1a), the silicon particles crack due to the uneven stress distribution during the expansion and shrinkage process. LE easily penetrates the newly exposed interface and generates insulated SEI layer which isolates Li-Si alloy from electrons, forming “dead silicon” and causes permanent lithium inventory loss. Additionally, the HF generated in LiPF6-based electrolyte would further etch Si and SiOx47, reducing active material and causing serious capacity loss. In QSE, the silicon’s cracking could be alleviated by the polymer gel due to the homogenized stress distribution48, and the solid gel would not penetrate into cracked silicon. However, due to highly fragile nature and low deformability of PMMA, the QSE loses contact with Si electrode in the de-lithiation process when silicon particles intensively shrink, thus blocking the pathway for Li+ transport. This results in “inactive silicon”, which means it cannot fully release lithium due to blocked interface and sluggish Li+ transport kinetics. In the case of Upy-QSE, the polar groups form multiple hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl groups on silicon’s surface, providing robust adhesive force and self-healing property. Consequently, it maintains close contact with silicon particles even at de-lithiation stage, ensuring sufficient Li+ pathway during repeated charge/discharge (the silicon in this case is thus defined as “active silicon”). From a view of electrode-level, as the silicon content increases, the volume effect would be more pronounced. As displayed in Fig. 1b, since PMMA is a fragile and tough polymer, electrode-level cracks would appear in the case of QSE due to the stress accumulation caused by repeated volume change. In contrast, Upy-QSE exhibits a significantly higher elasticity modulus to withstand a greater degree of deformation as silicon expands and contracts. The self-healing property of the UpyMA units further allows the electrode to repair itself even if cracks emerge, maintaining a robust and resilient Li+ conductive network.

a Schematic depicting the failure mechanisms of silicon electrodes in LE, QSE, and Upy-QSE. b Schematic depicting the Li+ transportation in QSE and Upy-QSE. c Nanoindentation tests on QSE and Upy-QSE. d 180° peeling tests on silicon electrode sheets adhered by QSE and Upy-QSE. In this test, the electrolyte precursor was injected between two identical silicon electrode pieces. After fully polymerized, the two silicon electrode sheets were peeled apart by a tensile monitor. e Binding energies between silicon surface and QSE, Upy-QSE respectively. f FT-IR spectra of pristine silicon particles, QSE-coated silicon particles and Upy-QSE coated silicon particles.

A nanoindentation test was carried out to evaluate the mechanical strength of the different gel electrolytes (Fig. 1c). The force-distance curve of Upy-QSE displays an obviously steeper slope compared to that of QSE, indicating a significantly higher elastic modulus. Upon retraction of the tip sensor, Upy-QSE recovers 40% of its deformation, while QSE only recovers 6.5%. This difference highlights the superior mechanical strength and resilience of Upy-QSE over QSE, attributed to the multiple hydrogen bond effect. To simulate the compressive forces exerted on gel electrolytes during silicon expansion, compressive stress tests were performed on both QSE and Upy-QSE, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 2. Upy-QSE exhibits a compressive modulus exceeding 11.2 MPa and fully recovers its original configuration upon pressure release (Supplementary Movie 1). In contrast, QSE fractures into pieces at 62% deformation, corresponding to a critical compressive modulus of only 0.46 MPa (Supplementary Movie 2). This distinctive mechanical property of Upy-QSE enables silicon electrode to maintain structure integrity and Li+ conductive network within bulk electrolyte (as depicted in Fig. 1b).

The interfacial adhesion force was quantitatively assessed through 180° peeling test (as shown in Fig. 1d), which reveals a significantly higher adhesion force (Fmax = 3.5 N) of Upy-QSE compared to QSE (Fmax = 0.48 N). This increased force is not only attributed to the strong hydrogen bonds between the silicon surface and the UpyMA unit, but also to the Upy-Upy intermolecular hydrogen bonds within the bulk electrolyte. MD simulations show that the binding energy of Si-OH-Upy (–1.16 eV) is 2.5 times greater than that of Si-OH-MMA (–0.46 eV) (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 1–2, 9–10). The Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) results (Fig. 1f) showcase that the peak (3500 cm−1) of hydroxyl group on silicon electrode becomes significantly weaker and broader, accompanied with a red shift after being coated with Upy-QSE, which is a strong evidence of weakened -OH molecular vibration caused by hydrogen bonding49. Apart from physical properties, the conductivity of Upy-QSE is slightly smaller than that of QSE (Supplementary Fig. 4) because hydrogen bonds would enhance mechanical strength of polymer and increase glass transition temperature (Tg)50, hampering Li+ transport. The room temperature (30 ± 1 °C)−2 conductivity follows the order of LE (12.3 mS cm–1) > QSE (4.37 mS cm–1) > Upy-QSE (3.79 mS cm–1), and the activation energy has the reverse trend: LE (0.14 eV) < QSE (0.21 eV) <Upy-QSE (0.22 eV).

Failure mechanism of micronized SiOx electrode in different electrolytes

To evaluate the electrochemical performance, Li||SiOx (1800 mAh g–1) coin cells with different electrolytes were assembled and tested. The average particle size of used SiOx material is around 5–10 μm, and the voltage profiles during 1st cycle are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. Benefiting from the improved solid-solid interface and self-healing property, the Upy-QSE cell exhibits the best cycling performance, showcasing 90.2% capacity retention after 400 cycles at 0.3 C/0.3 C@RT. This performance significantly surpasses that of the cells utilizing LE and QSE (Fig. 2a). Although LE lacks the mechanical constraints necessary to accommodate electrode volume changes, it provides sufficient charge transfer area due to thorough infiltration, resulting in a gradual capacity loss during cycling. In contrast, for QSE, once interface degradation and intra-cracks emerge, the cell is prone to suffer complete battery failure due to the compromised structural integrity and hindered transport pathways.

a 0.3C/0.3C cycling performance of Li||SiOx (1800 mAh g–1) with different electrolytes at room temperature (30 ± 1 °C). b Cross-sectional FIB-SEM and planar-view image of SiOx electrodes after 400 cycles with LE, QSE and Upy-QSE, the electrodes are de-lithiated with small current before sample preparation. c Li+ diffusion coefficients of Li||SiOx (1800 mAh g–1) cells with different electrolytes after 400 cycles calculated by GITT. d U-t curves of Li||SiOx (1800 mAh g–1) cells with different electrolytes obtained from GITT measurements. e Atomic force microscopy images and 3D Young’s modulus distribution of SiOx (1800 mAh g–1) electrodes cycled with different electrolytes. f Statistical distribution of Young’s modulus of SiOx (1800 mAh g–1) electrodes cycled with different electrolytes. (The AFM characterization is conducted after 400 cycles with 0.3 C/0.3 C, at de-lithiated state).

The SiOx electrode after 400 cycles were fully de-lithiated and diagnosed with focused ion beam-scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM). As shown in Fig. 2b, SiOx particles cycled with LE are coated with a thick passivation layer (gray region), which is attributed to extensive electrolyte decomposition during continuous particle pulverization. On the contrary, no obvious passivation layer can be observed in the other two groups, indicating the polymer gel could inhibit the electrolyte consumption during cycling. The corresponding 3D reconstruction mapping and depth profile obtained via time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6. Consistent with the FIB-SEM results, a substantial accumulation of SEI components resulting from electrolyte decomposition is observed on the negative electrode of LE. The secondary ion LiF2– fragments indicate the presence of LiF generated from LiPF6 and FEC, while PO3– and C2HO– correspond to Li3PO4 and organic SEI components formed by LiPF6 and carbonate solvents, respectively. Although the Si– signal increases progressively in all three negative electrodes with increasing sputtering depth—indicating the approach towards the bulk SiOx—the LE system consistently exhibits the weakest Si signal and the strongest SEI signal throughout the sputtering process. In contrast, both the QSE and Upy-QSE systems display obviously stronger Si signals and significantly thinner SEI layers, suggesting that electrolyte decomposition at the interface is substantially inhibited.

As observed in Fig. 2b, besides the thick SEI accumulation, large voids are observed among the particles in LE, which is caused by the loose compact and uncontrolled volume expansion. In the case of QSE, despite less SEI formation, numerous cracks and voids are still observed and solid-solid interface loss can be observed. Meanwhile, the planar view revealed extensive crack propagation on the cycled electrode with QSE, resembling the pattern of dried riverbed, leading to particle aggregating into isolated islands that impede Li+ transport. This is primarily due to the fragility and low compressive modulus of PMMA gel, which fails to withstand the stress generated by silicon expansion. By contrast, no visible cracks and voids are observed in the cycled negative electrode with Upy-QSE. All particles are compactly stacked, and no fracture appears in the planar view due to the high resilience and self-healing property of Upy-QSE. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements before and after 400 cycles (Supplementary Fig. 7) show that the QSE cell demonstrates the largest charge transfer resistance (Rct) after one cycle due to both interface loss and electrolyte cracks, while the Upy-QSE cell almost maintains comparable Rct value with the LE cell, crediting to the intact solid-solid interface and unblocked Li+ transfer. After 400 cycles, the Rct of the QSE cell evolves to a significantly larger value (621.2 Ω) than that of the LE cell (205 Ω) and the Upy-QSE cell (141.6 Ω).

Galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT, Fig. 2c) result show that the Upy-QSE enable almost one order of magnitude higher diffusive coefficient that of QSE at all lithiation states. Interestingly, although the cell with QSE delivers nearly zero capacity when cycled at 0.3/0.3 C (Fig. 2a), it releases almost comparable capacity with the Upy-QSE cell in the GITT measurement at a very small current density (Fig. 2d), where overpotential is diminished and compensated at each relaxation stage. However, the cell with LE still demonstrates much lower capacity as it does in the 0.3 C/0.3 C cycling. This variation reflects the different capacity loss mechanisms of these cells. To summarize, the LE cell mainly loses capacity by permanently losing active silicon due to unrestricted continuous swelling and shrinkage, and the “dead silicon” cannot contribute to capacity even under the thermodynamic equilibrium condition. On the contrary, the QSE cell loses capacity mainly due to interface loss and increased Rct (forming “inactive silicon”). When the current density is small enough, the Li+ can transport via limited interface area and thus provide capacity. In other words, LE suffers from thermodynamic capacity loss, whereas QSE experiences capacity loss due to kinetic limitations. For the Upy-QSE cell, the polymer with multiple hydrogen bonds not only prevent the loss of Li inventory but also maintains interfacial contact by strong binding effect along the whole cycle process, thus offering considerable kinetics performance at 0.3 C. Such phenomenon prevails not only in SiOx material, but also in silicon nanoparticles (SiNPs). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, the QSE demonstrates the lowest 1st Coulombic efficiency (55.7%) in the Li | |SiNP coin cells among the three electrolytes and can barely work at the same cycle condition, delivering almost zero capacity. By contrast, the Upy-QSE cell exhibits much higher CE than the QSE cell and identical cycling performance with the LE cell, owing to the preserved charge transfer interface.

To detect the mechanical strength of SEI cycled with different electrolytes, Young’s modulus was investigated by atomic force microscopy (AFM) in a region of 3×3 μm, conducted on cycled SiOx (1800 mAh g–1) electrodes. As shown in Fig. 2e, f, the SEI generated by LE has the lowest Young’s modulus (averagely 1.25 Gpa) due to large decomposition of organic solvents. By contrast, the rigidity of PMMA boosts the SEI modulus of QSE to averagely 2.0 Gpa, while the Upy-QSE exhibits the highest Young’s modulus up to 4.26 Gpa, owing to the high mechanical strength provided by multiple hydrogen bonds, which ultimately results in better particle integrity and stable cycling.

Pressure-free Ah-level Silicon-based pouch cells

To evaluate the practical feasibility of Upy-QSE, ampere hour-scale commercial pouch cells using NMC811 positive electrode and SiOx@Gr negative electrode with different specific capacities were assembled and tested at room temperature ((30 ± 1 °C). It should be noted that SiOx@Gr (450 mAh g–1) refers to an electrode composed of graphite mixed with 5 wt.% SiOx, whereas SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1) denotes an electrode containing graphite blended with 15 wt.% SiOx. Due to the differences in SiOx content and cell configuration, the electrolytes exhibit distinct performance in coin cells versus pouch cells. To ensure stable SEI formation, all pouch cells were charged under an external pressure of 100 kPa if no special mention, which was consistently maintained during subsequent C-rate performance testing. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, both SiOx@Gr (450 mAh g–1)||NCM811 and SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cells exhibit improved 1st Coulombic efficiency with an order of LE <QSE <Upy-QSE. The C-rate test of SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cells further show that the Upy-QSE cell maintains a capacity of 1497 mAh (94.7% of the capacity at 0.1 C) at 1 C, which is close to the LE cell (Supplementary Fig. 10). By contrast, despite higher conductivity, QSE exhibits much inferior C-rate performance compared to Upy-QSE, which can only be attributed to interfacial degradation and an increased charge transfer resistance (Rct).

Afterwards, the cycling performance of the cells with different electrolytes were evaluated at room temperature (30 ± 1 °C) without applying external pressure. Interestingly, the LE cell fails to support stable cycling and undergoes rapid capacity drop in the first 200 cycles in both pouch cells even with relatively low Si content (Fig. 3a, b, black curve), indicating the crucial role of stack pressure in maintaining the mechanical contact. By contrast, in SiOx@Gr (450 mAh g–1), the QSE and Upy-QSE deliver capacity retentions of 78.0% and 82.1%, respectively at 1000th cycle, exhibiting stable cycling performance with zero external pressure. Differing from the situation in Li||SiOx (1800 mAh g–1) half cells, the QSE exhibits a higher 1st CE than LE and much more stable cycling in SiOx@Gr (450 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cells. This is because that the interface loss and electrolyte crack problem mentioned previously are mitigated when SiOx content is quite low (5%) and volume change is mild. However, in SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 where SiOx content increases to 15%, the QSE exhibits significantly lower initial capacity compared to Upy-QSE due to intensified interface loss and mechanical failure. This phenomenon would be more pronounced with further increasing SiOx content, as will be discussed later in SiOx@Gr (900 mAh g–1) electrode. In stark contrast, the Upy-QSE cell not only matches the initial capacity of the LE cell at 1 C but also exhibits good cycling stability, retaining 83.0% of its capacity by the 600th cycle. Notably, even when the LE cells are subjected to sufficient external pressure (100 kPa, shown in Supplementary Fig. 11), their cycling performance, as indicated by the gray curves in Fig. 3a, b, remains inferior to that of the Upy-QSE in both pouch cells. The EIS of the cells before and after cycling without pressure are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 12. Both the Ohmic resistance and the charge transfer resistance of the LE cell increase by one magnitude of order after cycling, while the QSE and Upy-QSE cells maintain small resistance during the whole cycling process.

a Room temperature (30 ± 1 °C) cycling performance of SiOx@Gr (450 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cells with different electrolytes. b Room temperature (30 ± 1 °C) cycling performance of SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cells with different electrolytes. c Room temperature (30 ± 1 °C) cycling performance of SiOx@Gr (450 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cells with intermittent external pressure. d Charge/discharge curves of SiOx@Gr (450 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cell with LE during intermittent-pressure cycling. e-f Cross-sectional CT images of SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cells with e LE and f Upy-QSE after 600 cycles. (The CT imaging is conducted after completely CC discharging batteries to 2.5 V with small current of 0.05 C, 80 mA).

To determine the real-time impact of external pressure on batteries’ behavior, the pouch cells underwent cycling test with an intermittent 100 kPa external pressure (Fig. 3c). When the stack pressure is removed, the capacity of the LE cell drops to almost zero rapidly. Figure 3d displays the corresponding charge/discharge curves of the LE cell during the cycling process, large overpotential can be observed when the stack pressure is removed. Though the overpotential can be diminished when the pressure is re-applied, significant irreversible capacity loss occurs during the pressure-free cycling process, attributed to the emergence of “dead silicon”. In stark contrast, both the QSE and Upy-QSE cells exhibit complete independence of external pressure, delivering nominal capacity regardless of whether external pressure is applied or not.

After 600 cycles without external pressure, it is observed that the SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cell with LE demonstrates a drastic thickness swelling from 2.91 mm to 4.16 mm (Supplementary Fig. 13), while both the QSE and Upy-QSE cells remain to be thin pieces (from 2.94 mm to 3.147 mm for QSE, and from 2.897 mm to 3.036 mm for Upy-QSE, respectively). The cells were further diagnosed with non-destructive computed tomography (CT) imaging test (Fig. 3e, f). In the cross-sectional view of the pouch cell containing LE, the voids caused by the shrinkage of silicon electrode is prominently visible, and the electrodes are loosely stacked. Conversely, in the cell utilizing Upy-QSE, there is no apparent expansion of the electrodes; instead, all electrodes are compactly stacked. In addition, the cycled QSE and Upy-QSE cell preserve a better electrode morphology in the observation after cell disassembly (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Note 1). It is notable that almost no LE remains in the cycled LE battery, because the continuous SEI formation consumes electrolyte and finally leads to electrolyte depletion. The mechanism behind such phenomenon is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 15. Specifically, when silicon expands and contracts within liquid electrolytes, binders may fail to restore particles to their original positions, causing the electrode to irreversibly transition from a compact structure to a pulverized state. During this degradation, silicon particles undergo permanent displacement, losing contact with both conductive carbon and current collector. This creates electrically isolated “dead silicon,” a primary contributor to capacity loss and thickness growth. Applying external pressure during cycling mechanically realigns displaced particles, maintaining structural integrity. By preserving ionic and electronic pathways, this mechanical intervention inhibits capacity decay. In contrast, integrating a gel polymer into the electrode creates a crosslinked network that confines silicon particles. As silicon expands, the polymer chains stretch and store elastic potential energy. Upon contraction, this stored energy is released, dynamically restraining particle displacement and preserving electrode cohesion. Much like elastic rubber bands, the polymer network continuously counteracts mechanical stress without requiring external pressure, ensuring long-term structural and functional stabilities.

Quantification of “dead silicon” in pressure-free cells

To further confirm the failure mechanism of pressure-free silicon-based pouch cells, the SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cells were subjected to in situ thickness monitoring and differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) titration measurements. As shown in Fig. 4a, the thickness of the LE cell expands and shrinks drastically during 0.2 C/0.2 C charging and discharging, due to the unrestricted silicon particle volume change. The peak thickness arises from the volume expansion of silicon particles and particle displacement. Conversely, the minimum (valley) thickness reflects the reversibility of the Li–Si alloying process. Interestingly, the thickness of the LE cell fails to revert to initial value even after being completely discharged. Such irreversible thickness increment evolves at each cycle and rapidly accumulates to 741 μm after 5 cycles, indicating that the silicon is not fully de-lithiated due to the insulated “dead silicon” (therefore still occupying large volume). In comparison, the cell with QSE demonstrates merely 157 μm swelling (1/5 of that in LE cell) during charge, and the irreversible thickness increment is only 105 μm after 5 cycles. Thanks to the robust polymer chemistry, the thickness fluctuation of the Upy-QSE cell, is even less (within 95 μm), and the cell completely recovers to the initial thickness after 5th discharge (ΔT = 0 μm), indicating the Li+ insertion and extraction is highly reversible in Upy-QSE.

a In situ thickness monitoring of pouch cells’ first 5 cycles with different electrolytes. The current applied in the thickness monitoring is 0.2 C/0.2 C (320 mA), and the temperature is set to be 30 ± 2 °C. b Planar, cross-sectional SEM and FIB-SEM images of SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1) negative electrodes after 5 cycles. c Quantification of Li-Si alloy by DEMS titration measurements on different negative electrodes after 5 cycles. d-f TEM and FFT images of cycled SiOx (600 mAh g–1) with d LE, e QSE and f Upy-QSE after after 5 cycles. (Characterizations in (b–f) are all conducted after completely CC discharging batteries to 2.5 V with small current of 0.05 C, 80 mA).

The SEM images of the cycled negative electrodes after de-lithiation unveil the internal battery structure change (Fig. 4b): Severe electrolyte deposition is observed on the negative electrode cycled with LE, while for those with QSE and Upy-QSE, resilient polymer gel is coated on the particles instead, which is responsible for restricting the particle expansion. The cross-sectional SEM images provide crucial insights into the performance of the negative electrodes cycled with different electrolytes. In the case of the LE, the electrode exhibits severe destruction and particle detachment, with both graphite and silicon particles losing contact with the current collector. By contrast, the QSE manages to effectively inhibit active material pulverization, despite the presence of some observable cracks in the electrode structure, which is similar to those depicted in Fig. 2c. Conversely, the Upy-QSE group showcases a perfectly preserved electrode structure, with all particles compactly stacked and no voids or cracks present. The FIB-SEM images offer a clearer visualization of the cracks and voids present in the LE and QSE systems, whereas in Upy-QSE, all particles are compactly stacked, confirming the integrity of the conductive network. Elemental mapping results corresponding to the FIB-SEM images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, which reveal that silicon and oxygen are co-located, representing the SiOx particles. The fluorine element is predominantly distributed along the periphery of these particles, indicating the presence of the SEI passivation layer. Compared to LE and QSE, the exceptional structural integrity provided by Upy-QSE ensures an unobstructed Li⁺ transport pathway, resulting in significantly enhanced overall performance.

After cycling for 5 cycles, equal mass of negative electrode powder was collected in DEMS apparatus after complete discharging and titrated with deionized water to quantify the remaining Li in the negative electrodes. As shown in Fig. 4c, the negative electrode cycled with LE generates large amount of hydrogen gas in several minutes soon after the water is injected (6.5 × 10–2 nmol min–1 at maximum rate and 0.68 nmol by integration), which indicates that large amount of Li is remained in the negative electrode as “dead LixSi alloy”, due to the loss of electronic or ionic conduction. By contrast, the negative electrodes cycled with QSE and Upy-QSE generate only tiny amount of H2 (0.15 nmol and 0.11 nmol, respectively in total) at relatively slow rates, indicating minimal residue of “dead LixSi alloy” after cycling. The Upy-QSE generates the lowest amount of H2 because of enhanced interface and de-lithiation kinetics. In Fig. 4d, transmission electron microscope (TEM) image clearly detects the remained crystal Li15Si4 alloy in the negative electrode cycled with LE, which is a detrimental phase mainly contributing to the irreversible volume increment in silicon51,52,53. The fast Fourier transformation (FFT) image displays clear (431) lattice plane of Li15Si4 (d spacing = 0.21 nm) and (111) of LiF in the negative electrode cycled with LE. Notably, the negative electrodes cycled with QSE (Fig. 4e) and Upy-QSE (Fig. 4f) demonstrate disordered structure in wide range based on the FFT diffraction pattern, indicating that only amorphous silicon remains after de-lithiation compared to the crystalline phase observed in the LE-cycled negative electrode9,53.

Improved high temperature performance with high Si content negative electrode

It is widely known that scavenging the acidic substance HF and PF5 is essential for improving battery performance, especially for battery with high silicon and high nickel contents at high temperature20,21,54,55,56. UpyMA units with multiple urea and amide groups are Lewis base, which can neutralize HF and PF5 in the electrolyte. The three electrolytes were stored at 45 °C for 7 days to evaluate their thermal stability. The LE becomes complete black liquid and generates precipitation due to the polymerization of FEC, the QSE displays relatively shallower color than the LE, while the Upy-QSE maintains transparent and colorless state even storing for long time (Supplementary Fig. 17). The corresponding 19F NMR spectra (Fig. 5a) indicate that significant amount HF is generated in the LE (peak at –158 ppm), accompanied by numerous byproducts from decomposition of LiPF6, including PF5, POF3, PO2F2, etc (from –95 ppm to –80 ppm). It is obvious that less HF and other PxOyFz compounds are observed in the QSE, while all these peaks disappear completely in the Upy-QSE, demonstrating the great acid-scavenging ability of UpyMA and its extraordinary thermal stability at high temperature. According the DFT calculation (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 18 and Supplementary Data 3–14), HF and PF5 have binding energies of –4.24 eV and –4.023 eV with UpyMA, respectively, while they are only –2.39 eV and –2.3 eV with MMA unit, suggesting UpyMA’s affinity to coordinate and neutralize the detrimental acidic components in electrolyte.

a 19F NMR spectra of different electrolytes after 7 days storage at 45 °C. b Binding energies of HF and PF5 with QSE or Upy-QSE, respectively. c Cycling performance of SiOx (900 mAh g–1)||Ni90 pouch cells with different electrolytes at 45 °C. d Gas generation of SiOx (900 mAh g–1)||Ni90 pouch cells after cycling at 45 °C. e Gas components generated in (d). f Mechanism illustration of CO2 evolution in FEC-based electrolyte.

Inspired by the fact that UpyMA unit may play more important role with higher silicon content, we assembled 346.3 Wh kg–1 SiOx@Gr (900 mAh g–1)||LiNi0.9Co0.05Mn0.05O2 (Ni90) pouch cells (3.4 Ah) with high mass loading (6.73 mAh cm–2). As shown in Fig. 5c, the cell with Upy-QSE demonstrates 83.1% retention after 400 cycles at 45 °C without external pressure, delivering average CE up to 99.95%. However, the cell with LE only has much lower retention of 73% after 400 cycles, even with external pressure (100 kPa) applied. The QSE cell is also cycled without pressure, however, it delivers much lower initial capacity and exhibits quick capacity fade (56.3% at 400th cycle) compared to the Upy-QSE cell. Similarly, the drawback of lacking self-healing property and corresponding Li+ conduction loss in QSE electrolyte is magnified with increased silicon content in the electrode.

Interestingly, UpyMA not only improves the polymer chemistry of PMMA, but also enables self-healing property to other polymers when co-polymerizing with other monomers. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 19, QSE-PBA gel electrolyte was obtained with identical method as QSE, apart from replacing MMA with equal amount (15 wt.%) of butyl acrylate (BA). Similarly, when 3 wt.% of BA is replaced by UpyMA and co-polymerized in LE (noted as Upy-QSE-PBA), the gel becomes more robust and resilient than QSE-PBA. The electrochemical performances also follow a similar trend in the SiOx@Gr (900 mAh g–1) || Ni90 battery system: the QSE-PBA cell containing 15% PBA suffers from a low initial capacity and rapid capacity degradation, achieving only 60.8% capacity retention by the 400th cycle. In contrast, the Upy-QSE-PBA cell demonstrates a significantly higher initial capacity and stable cycling behavior, maintaining 72.5% capacity after 400 cycles.

The volume of gas generated during cycling was measured based on Archimedes principle (Fig. 5d, e). The cell with LE severely swells and evolves 32.5 mL of gas after 400 cycles, while the QSE cell releases 23 mL and the Upy-QSE cell only has 1.2 mL gas generation during the whole cycling process. Based on the gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) results, most of the gas generated in the Upy-QSE cell is CO2, which originates from FEC decomposition at high temperature. Similar phenomenon is also observed in SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cells, where gas generation also follows the order of LEå QSEå Upy-QSE (Supplementary Fig. 20). The corresponding gassing mechanism is explained in Fig. 5f: After LiPF6 is decomposed at high temperature, PF5 attacks the carbonyl oxygen of FEC, facilitating the ring-opening reaction accompanied by CO2 release, after which the continuous polymerization of FEC results in more HF and CO2 generation. As for the Upy-QSE cell, since HF and PF5 can be captured by urea and amide groups of Upy unit, the polymerization of FEC is interdicted and CO2 release is greatly inhibited.

The structure of the cycled positive electrodes was further characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and TEM (Supplementary Fig. 21). The peak intensity ratio of (003)/(104) indicates the extent of crystallization for R-3m layered structure57,58,59. As can be seen, the positive electrode cycled with LE demonstrates a weak (003) peak intensity, with I(003)/I(104) of only 1.187, indicating poor layered structure caused by serious Li+/Ni2+ cation mixing. In contrast, the positive electrodes cycled with QSE and Upy-QSE demonstrate I(003)/I(104) values of 1.263 and 1.381, respectively, in which the latter exhibits a strong and sharp (003) peak, indicating well-preserved layered structure with less Li+/Ni2+ cation mixing. According to the FFT analysis of the TEM images, large amounts of rock salt phase with Fm3m space group are observed in the near surface of the positive electrode cycled with LE. For the positive electrode cycled with Upy-QSE, besides the amorphous CEI layer, only well-ordered (003) lattice plane with typical d-spacing 0.47 nm can be observed. The result is in good accordance with XRD, proving that the Upy-QSE has great ability to inhibit Li+/Ni2+ mixing and preserve positive electrode’s layered structure, thus delivering high capacity and stable cycling.

Improved safety performance

To discover the intrinsic safety of the gel polymer electrolytes, we conducted self-distinguish-time (SET) measurements on different electrolytes. As depicted in Fig. 6a, the LE ignites immediately upon contact with the flame, demonstrating a lengthy SET of 26 s g–1. In contrast, the QSE necessitates an extended ignition period to sustain combustion and showcases a significantly shorter SET (8.3 g s–1). The Upy-QSE remains unignited even after exposure to flame for 30 s and extinguishes immediately once the flame is removed, exhibiting superior flame-retardant properties and enhanced safety. This is because amide and ureal groups in the Upy unit can generate N· free radical at high temperature and can quench the H· radical in the chain reaction occurring in the firing process, functioning as reported nitrogen-based flame retardants60,61.

a Ignition tests for LE, QSE and Upy-QSE. b DSC curves of fully charged NCM811 powder mixed with different electrolytes. c Optical photos of pouch cells when nail-penetrating test is conducted. d V-t and T-t curves of pouch cells when nail-penetrating test is conducted. e In situ infrared thermal images of pouch cells when thermal abusing test is conducted. The cells were placed in the oven where the temperature was escalated from 30 °C to 130 °C with a constant rate of 5 °C min–1, then maintained at 130 °C for 30 min. f V-t and T-t curves of pouch cells when thermal abusing test is conducted.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were then conducted to evaluate the stability of the electrolytes with fully-delithiated NCM811. As shown, the LE group displays an intensive exothermal peak at around 220 °C (Fig. 6b), which corresponds to the oxygen release from NCM811 lattice and subsequent electrolyte oxidation62,63. In comparison, the intensity of oxygen releasing peak is greatly reduced in the QSE group, and the onset temperature of O2 release is also delayed due to the polymer coating effect of PMMA64. Interestingly, an exothermal peak appears between 175 and 210 °C in the Upy-QSE group and the subsequent O2 releasing peak is inhibited to a larger extent. This could be attributed to the decomposition of Upy unit and generation of N· radical, responsible for quenching the oxygen radical generated by NCM811, which is detrimental to battery health and safety65.

The SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 pouch cells were again assembled and fully charged to 4.3 V for estimation of the electrolytes’ safety under practical circumstances. As shown in Fig. 6c, d, the LE pouch cell expands and explodes violently within several seconds under nail-penetration tests, demonstrating tremendous heat generation that raises the temperature to 565 °C. Simultaneously, the voltage drops immediately from 4.3 V to 0 V in one second. Though likewise being totally short circuited by the steel nail, the cell with QSE does not explode but only emits large amount of smoke with minor flame, behaving much milder and less dangerous. The temperature is raised up to 394 °C, considerably lower than that of LE, and the voltage drops much slower than LE (in 4 s), indicating milder energy release from the cell. As a strong contrast, the cell with Upy-QSE shows no signs of fire or smoke even after being penetrated by a steel nail for over 5 min. The temperature rises only from 30 °C to 46.7 °C, while the voltage experiences minor fluctuations but remains stable throughout the penetration process, underscoring its reliable safety performance. In the thermal abuse test (Fig. 6e, f), the in situ infrared thermal imaging and T-t curve show that the temperature of the LE cell rises obviously faster than that of the cells with QSE and Upy-QSE in the first 20 min, then exhibits uncontrollable self-heating to 145 °C at 43 min even when the external temperature is kept 130 °C. The ongoing-rising temperature is attributed to the cell self-heating intrigued by the SEI decomposition, separator shrinkage and electrolyte reduction66, ultimately the cell with LE suffers explosion and temperature skyrockets to over 800°C with voltage suddenly dropping to zero. In contrast, the two cells with QSE and Upy-QSE demonstrate slower temperature rising in heating process and invariable temperature during the constant 130 °C region, which means that no thermal runaway reaction occurs at this temperature, therefore the cells with QSE and Upy-QSE do not catch fire along the whole process with a stable OCV.

In conclusion, conventional liquid electrolyte may not fundamentally resolve the systematic challenges in silicon-based LIBs. The loss of active lithium, gas evolution, intensive volume change and requirement for high external stack pressure all restrict the application of silicon-based electrodes. In this work, we proposed a solution from a different perspective to solve these problems simultaneously. By in situ solidifying the electrolyte and enabling it with strong self-healing property, the “dead LixSi alloy” can be minimized due to enhanced electrode integrity and unblocked Li+ transport pathway. As a result, the Ah-scale quasi-solid-state pouch cells with high silicon content deliver superior cycling stability than liquid-state counterparts even without external stack pressure, the elimination of pressure devices not only simplifies the design but also enhances the overall energy density at the packing level. Additionally, we emphasize that the effect of self-healing polymer is more pronounced as the silicon content increases. The Lewis basicity of UpyMA also scavenges acid in the electrolyte at high temperature, reducing gas generation and enhances battery safety. Considering that the in situ polymerization technique demonstrates high feasibility and compatibility with the current battery manufacturing industry, along with the low cost of polymer materials, we believe that our findings hold significant potential for the ultimate commercialization of silicon-based high-energy-density batteries.

Methods

Synthesis of UpyMA

The synthesis of UpyMA follows the previous literature report45. First, 6 g of 6-methylisocytosine (Sigma-Aldrich; 99%) was added into 150 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich; AR), and stirred for 30 min at 150 °C. Then the solution was cooled to ambient temperature and 11.88 g of 2-isocyanatoethyl methacrylate (Sigma-Aldrich; 98%) was added to the flask, which precipitated a white solid when the mixture was cooled using an ice bath. Then the precipitate was collected by washing and centrifuging in acetone for 5 times to remove residual solvent. The UpyMA monomer was obtained after being dried under a vacuum at 30 °C for 4 h.

Synthesis of LE, QSE and Upy-QSE

FEC, dimethyl carbonate (DMC), LiPF6 were obtained from Shenzhen Capchem Technology Co., Ltd. (China) with purities of >99.5%. MMA, UpyMA, poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) and azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) were purchased from Aladdin Co., Ltd. with purities of >99%. The LE was prepared by adding 1.0 M LiPF6 in FEC/DMC mixture solvent at a weight ratio 1/2. For the synthesis of QSE, 15 wt.% of MMA monomer was added into LE, note that the salt concentration was maintained 1.0 M in the precursor. To ensure a self-standing gel with elasticity, PEGDA as the crosslinker was added into the solution with the mass corresponding to 5 wt.% of PMMA. After totally mixing monomers with LE, 0.2 wt.% of AIBN as the initiator was added, then the mixture was injected into cell and placed at 60°C for 8 h for a full polymerization. The preparation processes of Upy-QSE were identical except for replacing 3 wt.% MMA with UpyMA.

Physical characterizations

1H and 19F NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury 400 MHz NMR spectrometer. XRD was carried out by SmartLab 3 KW with a Cu Kα radiation source in a 2θ range of 10°–90°. The morphology of cycled electrodes was characterized by using field-emission SEM (TESCAM MIRA3). TEM images were obtained by Hitachi HT7700 operated at 200 kV. DSC was conducted by Hitachi STA300 with a scanning rate of 5 °C min–1 from 30 °C to 300 °C. Nanoindentation test was conducted by TI-950, NHT under the maximum force of 1 mN. All the electrode and electrolyte samples in this work are prepared in 99.99% Ar gas atmosphere in the glovebox.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements for Li||SiOx coin cells

SiOx electrodes were prepared by mixing micron-sized SiOx (1800 mAh g–1) powder, super P and polyacrylic acid (PAA) at a weight ratio of 8:1:1 in deionized water to form homogenous slurry (SiOx material, super P and PAA are all obtained from Guangdong Canrd New Energy Technology Co.,Ltd.). The slurry was ball milled for half an hour and painted onto a copper foil, and the thickness of coated layer was controlled to be 100 μm by a blade caster. The electrodes were dried in a vacuum oven to remove the water. The SiOx electrodes were punched into pieces with 12 mm diameter, and the mass loading of each electrode was ≈1.4 mg cm–2.

2025-type coin cells (obtained from Guangdong Canrd Technology Co. Ltd.) were assembled using 500 μm Li foil as the negative electrode and glass fiber as the separator. The LE injection volume was controlled to be 120 μL for each cell. For the QSE and Upy-QSE groups, 120 μL of liquid precursor was injected instead while other assembly procedures were controlled to be identical. Note that the pressing pressure for coin cell assembly was controlled to be 500 kPa, however, the remaining pressure inside the coin cells was around 10–50 kPa according to previous reports67. After assembly, the cells with QSE and Upy-QSE were aged at 60 °C for 8 h in the oven for complete gelation. All the coin cells assembled in this work utilize one piece of PP Celgard 2500 separator with 19 mm diameter and 25 μm thickness, the porosity of the separator is around 43%, and the pore size is around 0.1 ~ 0.3 μm.

Li||SiOx cells were discharged/charged between 2.0 V and 0.01 V at 0.05 C/0.05 C (1 C = 1800 mA g–1) for one cycle as the activation process. The rate capability was measured by discharging/charging at 0.1 C/0.1 C, 0.2 C/0.2 C for three cycles sequentially. Then the rate was set to be 0.3 C/0.3 C for following long cycles. The battery test system is provided by Neware Technology Co.Ltd, Shenzhen.

Electrochemical measurements for SiOx@Gr||NCM811 pouch cells

SiOx@Gr (450 mAh g–1)||NCM811 (1600 mAh) and SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 (1600 mAh) pouch cells were obtained from Shenzhen Capchem Technology Co., Ltd. (China), and SiOx/Gr (900 mAh g–1)||Ni90 (3440 mAh) pouch cells were provided by CALB Technology Co., Ltd. (China). First, the pouch cells were opened and dried at 85 °C for 24 h to remove residual water. Then, the cells were injected with 2.5 g Ah–1 of LE or QSE precursors and sealed under vacuum in a glove box (O2, H2O < 0.01 ppm, Mikrouna, China). Then the sealed pouch cells with QSE or Upy-QSE precursor were placed at 60°C for 8 h for full polymerization. The LE groups were placed at room temperature (30 ± 1 °C) instead of 60°C. For the SEI formation, the cells were charged at 0.02 C for 3 h (1 C = 1600 mA). The pouch cells were charged to 4.25 V at 0.1 C via a CC/CV procedure with 80 mA as the limiting current, and then were CC discharged to 2.75 V at 0.1 C, then all cells underwent a 0.5 C/0.3 C, 0.5 C/0.5 C,0.5 C/1 C charging/ discharging process, for the evaluation of C-rate performance. Finally, the pouch cells were subjected to long-term cycling at 0.5 C/0.5 C under room temperature (30 ± 1 °C) with or without external pressure. At least wo cells were selected for parallel experiments.

The electrochemical measurements of SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 and SiOx/Gr (900 mAh g–1)||Ni90 pouch cells were identical with above process, except for these following differences: The voltage range was set between 2.5 V and 4.3 V, and the cycling condition of SiOx@Gr (600 mAh g–1)||NCM811 was 1 C/1 C at 30°C, while for the SiOx@Gr (900 mAh g–1)||Ni90, it was 0.33 C/0.33 C at 45°C.

Ionic conductivity measurements

A concentric circle polyimide ring was manually prepared by punching the polyimide membrane with a thickness of 0.25 mm into pieces with external diameter 19 mm and internal diameter 12 mm. Then the polyamide ring was used as a separator in a stainless steel (SS)||SS coin cell, and the LEs or QSE precursors were injected into the hollow space created by polyimide ring separated between the two SS electrodes. After assembly, the SS||SS cells with QSE precursors were placed at 60 °C for 8 h to ensure full polymerization. The conductivity of the electrolyte was calculated by the following Eq. (1) 68:

where L is the thickness of the electrolyte, which equals to 0.25 mm. A is the contact area, which is 1.13 cm2. R is the ohmic resistance measured by EIS using electrochemical working station 1470E Solartron system with frequency ranging from 106 Hz to 0.01 Hz.

GITT and calculation of Li+ diffusion coefficients

The lithium-ion diffusion coefficients (DLi+) were studied by GITT according to the following formula:

The galvanic titration time is denoted by τ. The parameters mB, MB, and Vm are the mass, molar mass, and molar volume of the SiOx electrode, respectively, while S is the electrode’s surface area. ΔES signifies the voltage change in a single titration step, and ΔEτ is the total voltage change over the entire titration period, excluding the IR drop. A low current pulse of 0.05 C was administered to the battery for 10 min to measure the closed-circuit voltage (CCV), followed by a 30-min relaxation period to determine the open-circuit voltage (OCV).

EIS measurement

Before the EIS measurements, all the cells were precisely set to 50% SOC according to their last cycle’s capacity if not intentionally adjusted. The measurements were conducted by working station 1470E Solartron system with frequency ranging from 106 Hz to 0.01 Hz. The EIS measurement utilizes potentiostatic mode, the amplitude of the polarization voltage applied is 0.01 V. The data collection is 10 steps/decade, all the EIS measurements are conducted after 5 min’ open circuit resting.

DFT calculation and MD simulation

The investigation combined DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6-311 G(d,p) level for electronic structure analysis (geometry optimization criterion: forces <4.5 × 10⁻⁴ Hartrees/Bohr)69,70 and MD simulations with the COMPASS force field to analyze molecules distributions. Non-bonded interactions (Lennard-Jones and Coulomb) were treated with a 12 Å cutoff, and long-range electrostatics were managed by the PPPM method. All MD simulations were performed under NPT conditions (303 K, 1 atm) with periodic boundaries, using a Nose–Hoover thermostat (5 ns relaxation time) and a 1 fs timestep. Silicon (001) surface with one layer of hydroxyl groups was selected to calculate the binding energy between polymer unit and silicon. The binding energy between HF& polymer unit or PF5& polymer unit were calculated based on the interaction with -CH3 of QSE and -NH- of Upy-QSE, respectively.

Safety test for pouch cells

For the nail-penetrating test: The pouch cells were charged to 4.3 V by CC/CV protocol and placed into the nail-penetrating test box. The steel nail with diameter of 3 mm penetrated the geometric center of the cell, and was kept for at least 5 min, during which the voltage and temperature were monitored by the electrochemical workstation and temperature sensor, respectively. For the thermal abusing test (or hotbox test): The pouch cells were charged to 4.3 V by CC/CV protocol and placed into the hotbox. The environment temperature was firstly raised to 130°C from room temperature (30 °C) at rate of 5 °C min–1, then was kept at 130 °C for 30 min, during which the voltage and temperature were monitored by the electrochemical workstation and temperature sensor, respectively.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed and generated during the current study are included in the paper and its Supplementary Information file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Choi, J. W. & Aurbach, D. Promise and reality of post-lithium-ion batteries with high energy densities. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16013 (2016).

Kim, N., Kim, Y., Sung, J. & Cho, J. Issues impeding the commercialization of laboratory innovations for energy-dense Si-containing lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 921–933 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Research progress of SiOx-based anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 473, 145294 (2023).

Ma, J. et al. Strategic pore architecture for accommodating volume change from high Si content in lithium-ion battery anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1903400 (2020).

Son, I. H. et al. Silicon carbide-free graphene growth on silicon for lithium-ion battery with high volumetric energy density. Nat. Commun. 6, 7393 (2015).

Franco Gonzalez, A., Yang, N.-H. & Liu, R.-S. Silicon anode design for lithium-ion batteries: progress and perspectives. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 27775–27787 (2017).

Jetybayeva, A., Aaron, D. S., Belharouak, I. & Mench, M. M. Critical review on recently developed lithium and non-lithium anode-based solid-state lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 566, 232914 (2023).

Sun, L. et al. Recent progress and future perspective on practical silicon anode-based lithium ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 46, 482–502 (2022).

Choi, I., Lee, M. J., Oh, S. M. & Kim, J. J. Fading mechanisms of carbon-coated and disproportionated Si/SiOx negative electrode (Si/SiOx/C) in Li-ion secondary batteries: Dynamics and component analysis by TEM. Electrochim. Acta 85, 369–376 (2012).

He, Y. et al. Progressive growth of the solid–electrolyte interphase towards the Si anode interior causes capacity fading. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1113–1120 (2021).

Dimov, N., Kugino, S. & Yoshio, M. Carbon-coated silicon as anode material for lithium ion batteries: advantages and limitations. Electrochim. Acta 48, 1579–1587 (2003).

Huang, Z. et al. A low-cost and scalable carbon coated SiO-based anode material for lithium-ion batteries. ChemistryOpen 10, 380–386 (2021).

Qi, S. et al. Electrode design from “internal” to “external” for high stability silicon anodes in lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 14142–14149 (2019).

Shi, W. et al. Covalently bonded Si–polymer nanocomposites enabled by mechanochemical synthesis as durable anode materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 39127–39134 (2020).

Wu, H. & Cui, Y. Designing nanostructured Si anodes for high energy lithium ion batteries. Nano Today 7, 414–429 (2012).

Cheng, Z. et al. Fundamental understanding and facing challenges in structural design of porous Si-based anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2301109 (2023).

Jia, H. et al. Hierarchical porous silicon structures with extraordinary mechanical strength as high-performance lithium-ion battery anodes. Nat. Commun. 11, 1474 (2020).

Jin, Y. et al. Identifying the structural basis for the increased stability of the solid electrolyte interphase formed on silicon with the additive fluoroethylene carbonate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 14992–15004 (2017).

Kang, Y. et al. Multifunctional fluoroethylene carbonate for improving high-temperature performance of LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2||SiOx@graphite lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 9989–10000 (2020).

Kim, K. et al. Understanding the thermal instability of fluoroethylene carbonate in LiPF6-based electrolytes for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 225, 358–368 (2017).

Schiele, A. et al. The critical role of fluoroethylene carbonate in the gassing of silicon anodes for lithium-ion batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 2228–2233 (2017).

Huo, H. & Janek, J. Silicon as emerging anode in solid-state batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 4005–4016 (2022).

Guo, Y. et al. Solid-state lithium batteries: safety and prospects. eScience 2, 138–163 (2022).

Huo, H. et al. Chemo-mechanical failure mechanisms of the silicon anode in solid-state batteries. Nat. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-023-01792-x (2024).

Zhao, M. et al. Unveiling challenges and opportunities in silicon-based all-solid-state batteries: thin-film bonding with mismatch strain. Adv. Mater. 36, 2308590 (2024).

Cao, D. et al. Unveiling the mechanical and electrochemical evolution of nanosilicon composite anodes in sulfide-based all-solid-state batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203969 (2023).

Huang, Y., Shao, B., Wang, Y. & Han, F. Solid-state silicon anode with extremely high initial coulombic efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 1569–1580 (2023).

Tan, D. H. S. et al. Carbon-free high-loading silicon anodes enabled by sulfide solid electrolytes. Science 373, 1494–1499 (2021).

Wu, Z. et al. Fabrication pressures and stack pressures in solid-state battery. eScience 4, 100247 (2024).

Cui, J. et al. Effect of continuous pressures on electrochemical performance of Si anodes. Mater. Today Energy 20, 100632 (2021).

Liu, F. et al. Polymer-ion interaction prompted quasi-solid electrolyte for room-temperature high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2409838 (2024).

Huang, Q. et al. Supremely elastic gel polymer electrolyte enables a reliable electrode structure for silicon-based anodes. Nat. Commun. 10, 5586 (2019).

Bok, T. et al. An effective coupling of nanostructured Si and gel polymer electrolytes for high-performance lithium-ion battery anodes. RSC Adv. 6, 6960–6966 (2016).

Chen, J. et al. Multiple dynamic bonds-driven integrated cathode/polymer electrolyte for stable all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202307255 (2023).

Cho, Y.-G. et al. Organogel electrolyte for high-loading silicon batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 8005–8009 (2016).

Li, X. et al. A dual-functional gel-polymer electrolyte for lithium ion batteries with superior rate and safety performances. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 18888–18895 (2017).

Du, W. et al. Cyclic ethers-based solid electrolyte derived from in situ ring-opening polymerization strategy. Green Energy Environ. 10, 1359–1376 (2024).

Peng, S., Fu, J., Wei, L. & Guo, X. In situ polymerized ether-based polymer electrolytes towards practical lithium metal batteries. Chem. Commun. 61, 868–880 (2025).

Barner-Kowollik, C. Acrylate free radical polymerization: from mechanism to polymer design. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 30, 1961–1963 (2009).

Wang, C. et al. Self-healing chemistry enables the stable operation of silicon microparticle anodes for high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Chem. 5, 1042–1048 (2013).

Wu, H. et al. Stable Li-ion battery anodes by in-situ polymerization of conducting hydrogel to conformally coat silicon nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 4, 1943 (2013).

Zhang, G. et al. A quadruple-hydrogen-bonded supramolecular binder for high-performance silicon anodes in lithium-ion batteries. Small 14, 1801189 (2018).

Han, J.-G., Kim, K., Lee, Y. & Choi, N.-S. Scavenging materials to stabilize LiPF6-containing carbonate-based electrolytes for Li-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 31, 1804822 (2019).

Yim, T. et al. Effect of acid scavengers on electrochemical performance of lithium–sulfur batteries: Functional additives for utilization of LiPF6. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 53, 08NK01 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. A strongly complexed solid polymer electrolyte enables a stable solid state high-voltage lithium metal battery. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 5149–5158 (2022).

Zhou, B. et al. A flexible, self-healing and highly stretchable polymer electrolyte via quadruple hydrogen bonding for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 11725–11733 (2018).

Ha, Y. et al. Effect of water concentration in LiPF6-based electrolytes on the formation, evolution, and properties of the solid electrolyte interphase on Si anodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 49563–49573 (2020).

Bai, M. et al. An in-situ polymerization strategy for gel polymer electrolyte Si||Ni-rich lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 15, 5375 (2024).

Jeong, D., Yook, J., Kwon, D.-S., Shim, J. & Lee, J.-C. Interweaving elastic and hydrogen bond-forming polymers into highly tough and stress-relaxable binders for high-performance silicon anode in lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 10, 2302027 (2023).

Kuo, S.-W. & Tsai, H.-T. Self-complementary multiple hydrogen bonding interactions increase the glass transition temperatures to supramolecular poly(methyl methacrylate) copolymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 123, 3275–3282 (2012).

Chevrier, V. L., Zwanziger, J. W. & Dahn, J. R. First principles study of Li–Si crystalline phases: charge transfer, electronic structure, and lattice vibrations. J. Alloy. Compd. 496, 25–36 (2010).

Liu, X. H. et al. Anisotropic swelling and fracture of silicon nanowires during lithiation. Nano Lett. 11, 3312–3318 (2011).

Obrovac, M. N. & Christensen, L. Structural changes in silicon anodes during lithium insertion/extraction. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 7, A93 (2004).

Amatucci, G., Du Pasquier, A., Blyr, A., Zheng, T. & Tarascon, J. M. The elevated temperature performance of the LiMn2O4/C system: failure and solutions. Electrochim. Acta 45, 255–271 (1999).

Shin, Y. & Manthiram, A. Factors Influencing the Capacity Fade of Spinel Lithium Manganese Oxides. J. Electrochem. Soc. 151, A204 (2004).

Zhan, C., Wu, T., Lu, J. & Amine, K. Dissolution, migration, and deposition of transition metal ions in Li-ion batteries exemplified by Mn-based cathodes – a critical review. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 243–257 (2018).

Liu, W. et al. Boosting cycle stability of NCM811 cathode material via 2D Mg-Al-LDO nanosheet coating for lithium-ion battery. J. Alloy. Compd. 867, 159079 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Unraveling the degradationmechanismofLiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 atthe highcut-offvoltage for lithium ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 77, 428–437 (2023).

Zhao, W. et al. Extending the high-voltage operation of Graphite/NCM811 cells by constructing a robust electrode/electrolyte interphase layer. Mater. Today Energy 34, 101301 (2023).

Horacek, H. & Grabner, R. Advantages of flame retardants based on nitrogen compounds. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 54, 205–215 (1996).

Morgan, A. B. & Klatt, M. in Non-Halogenated Flame Retardant Handbook 236–270 (Wiley, 2021).

Noh, H.-J., Youn, S., Yoon, C. S. & Sun, Y.-K. Comparison of the structural and electrochemical properties of layered Li[NixCoyMnz]O2 (x = 1/3, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8 and 0.85) cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 233, 121–130 (2013).

Yang, L. et al. Anomalous Thermal Decomposition Behavior of Polycrystalline LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2 in PEO-Based Solid Polymer Electrolyte. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200096 (2022).

Rui, X. et al. In situ polymerization facilitating practical high-safety quasi-solid-state batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402401 (2024).

Jiang, Z. et al. Quenching singlet oxygen via intersystem crossing for a stable Li-O2 battery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2202835119 (2022).

Feng, X., Ren, D., He, X. & Ouyang, M. Mitigating thermal runaway of lithium-ion batteries. Joule 4, 743–770 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Internal pressure regulation enables reliable electrochemical performance evaluation of lithium-ion full coin cell. J. Power Sources 600, 234235 (2024).

Feng, J. et al. Hollow nanotubular clay composited comb-like methoxy poly(ethylene glycol) acrylate polymer as solid polymer electrolyte for lithium metal batteries. Electrochim. Acta 340, 135995 (2020).

Lu, J., Chen, Z., Pan, F., Cui, Y. & Amine, K. High-performance anode materials for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 1, 35–53 (2018).

Placke, T., Kloepsch, R., Dühnen, S. & Winter, M. Lithium ion, lithium metal, and alternative rechargeable battery technologies: the odyssey for high energy density. J. Solid State Electrochem. 21, 1939–1964 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22078144 and 92472115), the Guangdong Special Support Program (2021TX06L775), the Shenzhen-Hong Kong-Macao Science and Technology Innovation Project (Category C, SGDX20220530111004028), the Innovation and Technology Commission of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (MHP/028/21, ITC-CNERC14EG03), the Research Grant Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (R6011-23F, CRS_HKUST604/22, JLFS/P-602/24), Guangzhou Nansha Science & Technology Bureau (2024ZD009) and Guangzhou Science and Technology Bureau (2024A03J0609). Sincere acknowledgement to the Shenzhen Capchem Technology Co., Ltd., for providing pouch cells and electrolytes for the accomplishment of the experiment, and the technique support for the nail-penetration test.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.L., Y.D., J.W. and M.S. conceived the idea. F.L. and Y.Z. conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Y.L. contributed to the theoretical calculations. Z.L. helped with the DEMS titration test as well as the CT imaging, Y.J. helped conducted TEM characterizations. X.C. contributed to the FIB-SEM characterizations. X.X., H.S., J.G. and F.P. contributed to data discussion. J.W., Y.D. and M.S. supervised this work. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiang Han, Yuju Jeon and Jang Wook Choi for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, F., Zeng, Y., Li, Z. et al. A gel polymer electrolyte with multiple hydrogen bonding for pressure-free Ah silicon-based pouch cells. Nat Commun 16, 11708 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66757-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66757-x