Abstract

Practical electrolyzer-level hydrogen production, exemplified by alkaline anion exchange membrane (AEM) ones, typically operates at harsh conditions, e.g., high-current densities (> 1 A cm−2) and long-term duration, which present significant challenges for the durability of catalysts. These challenges are amplified in atomically dispersed catalysts due to their weak point-to-point interactions. Here, we present an atom-ordering strategy to fabricate Co triangular orders that enable the activation of the substrate for durable AEM electrolyzers. We demonstrate that Co atoms thermodynamically favor triangular arrangements within the VN lattice, which are successfully synthesized via a photo-induced self-assembly method. This Co-triangular order enables the activation of adjacent V atoms, driving the exponential propagation of active sites for hydrogen production under high currents. Notably, this catalyst exhibits an extended linear region in the Tafel slope and performs stably at a current density of 1 A cm–2. The assembled AEM water electrolyzer achieves a cell voltage of 1.97 V with long-term operational durability. Our work provides a strategy for designing atom-ordered catalysts that strike a balance between activity and long-term stability under industrial operating conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrochemical water electrolyzers powered by sustainable energies such as solar, wind, and tidal energy offer a promising route for green hydrogen production1,2. In particular, alkaline anion exchange membrane (AEM) electrolyzers that utilize cost-effective non-noble-metal catalysts at both anode and cathode under alkaline conditions are gaining considerable interest for industrial-level hydrogen production3,4. However, the current fact is that most reported catalysts have been evaluated in solution-based three-electrode methods, that is, low current densities (10–100 mA cm−2), room temperature (~25 °C), and limited cycling times (several to tens of hours)5. Those conditions are also far less stringent than those encountered in AEM electrolyzer-level operation, where the current densities reach 1000 mA cm−2 with a cell voltage of 1.7–2.5 V, operating temperature range from 50 to 80 °C, and the system must sustain at least 100 hours at 500–1000 mA cm–2 6,7. Consequently, the high activity of a catalyst measured by the above solution-based methods does not accurately reflect the demands of a practical AEM electrolyzer. Therefore, designing a catalyst for practical applications must prioritize both tolerance and activity to ensure optimal performance under the more challenging and demanding conditions of real-world operations.

Emerging atomically-dispersed catalysts, such as single-atom catalysts, offer well-defined active sites, nearly complete atom utilization, cost-effectiveness, and tunable metal atom-support interaction, providing a model platform for mechanisms investigations8,9,10. Despite their notable performance in solution-based systems above, most single-atom catalysts suffer from limited durability in practical AEM full cells due to weak point-to-point metal–support interactions. Recent studies have demonstrated that constructing atomically ordered structures within a lattice, e.g., atomic array11,12,13 and intermetallic compounds14,15,16, offers a promising strategy to: i) stabilize single atoms via enhanced leaching tolerance17; ii) create synergistic catalytic sites18,19, and iii) optimize the electronic structure of the metallic center20. For example, ordered transition metal (TM = Pd, Rh, Ir, or Pt) single-atom sites within a Mg lattice (Mg24TM4) have demonstrated improved catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability in catalytic hydrogenation reactions14. However, the potential application of atomically ordered catalysts in AEM cells remains largely unexplored.

Herein, we present an atom-ordering strategy to synthesize a triangular cobalt-based catalyst that achieves a balance between catalytic activity and operational durability, enabling its practical integration into a full AEM electrolysis cell. First, our density functional theory (DFT) calculations suggest that ordered Co atoms (O-Co) may posses higher structural stability than conventional surface-supported Co (SS-Co) single atoms or clusters. Subsequently, we developed a photo-induced self-assembly method to fabricate Co triangular orders, characterized by complementary methods, including atomic-resolution aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) and electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS). Next, our electrochemical measurements show that O-Co/VN delivers enhanced alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) activity compared to SS-Co/VN and Pt/C catalysts, particularly at higher overpotentials. More importantly, our ex-situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), and on-chip total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, combined with DFT calculations, provide evidence that the Co triangular orders facilitate the activation of adjacent V atoms in the substrate, thereby enabling a catalytic surface on the VN substrate. Finally, the assembled AEM water electrolyzer exhibited a lower cell voltage (1.97 V) alongside stable operation (over 600 hours with a degradation rate of 0.13 mV h–1).

Results

Principle of atom-ordering catalysts

To investigate whether Co-atom orders would be more stable than conventional SS Co single-atoms or nanoclusters, we first conducted DFT calculations to examine the binding energies of Co atoms either on the surface of VN or within its lattice (Fig. 1a, b). The reason we choose this Co-VN system is based on two points: i) VN can serve as effective support for anchoring single atoms due to its abundant unsaturated defective sites (exceeding N-doped graphene), metallic conductivity, and appropriate porosity for gas escape21; ii) Co atoms were selected due to their similar radii with favorable affinity to V vacancies as well as their optimized hydrogen binding energy in alkaline electrolyte22. Unlike randomly distributed N bonds in the VN surface, V vacancies in the VN lattice show a naturally ordered arrangement that could facilitate the formation of ordered Co atoms. It is worth noting that similar-radii Ni and Fe atoms, as well as larger Pt atoms, were also studied in our work as potential in-lattice substitutes.

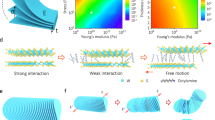

Schematic illustration of two types of structures: surface-supported Co (SS-Co) (a) and ordered Co (O-Co) atoms (b). In the SS-Co structure, Co atoms are randomly absorbed on the surface of VN support, whereas in the O-Co structure, Co atoms substitute V sites within the VN lattice. c Binding energy of SS-Co/VN and O-Co/VN configurations as a function of the number of Co atoms ranging from one to five (denoted as 1 O-Co, 2 O-Co, 3 O-Co, 4 O-Co, and 5 O-Co, respectively). The O-Co configuration shows lower binding energies than those of their SS-Co counterparts. Inset: the corresponding atomic structures of SS-Co/VN and O-Co/VN under various configurations. d Schematic illustrating the migration of Co atoms from the VN surface or lattice in the configurations of SS-Co1, LS-Co1, SS-Co3, and O-Co3. The blue and yellow balls represent V and Co atoms, respectively. e Calculated migration energy barriers for the configurations in (d), revealing that the O-Co3 motif exhibits the highest energy barrier with enhanced structural stability. Source data for the (c, e) are provided as a Source Data file.

Our calculations examined the binding energies of O-Co and SS-Co structures via one-by-one increasing Co atoms from one to five (Fig. 1c). In O-Co/VN configurations, Co atoms within the lattice tend to adopt ordered arrangements—namely dimer, trimer, tetramer, and pentamer—as suggested by the minimum-energy principle (see details in Supplementary Fig. 1–4). To evaluate the intrinsic structural stability, we calculated migration energy barriers for the detachment of a Co atom from the VN lattice based on a series of configurations (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 5–6, and Note S1)23. Among surface-supported single Co (SS-Co1), lattice-substituted single-atom Co (LS-Co1), surface-supported triangular Co (SS-Co3), and ordered triangular Co (O-Co3), the migration barrier follows the trend of SS-Co1 (1.0 eV) < LS-Co1 (2.0 eV) < SS-Co3 (2.1 eV) < O-Co3 (3.1 eV). This finding suggests that lattice substitution may enhance the single-atom stability and that ordered triangular Co3 is likely to be more resistant to migration and leaching. It is also worth mentioning that higher-order configurations tend to exhibit lower migration barriers within the VN lattice (O-Co4: 1.9 eV; O-Co5: 1.3 eV; Supplementary Fig. 7–8), indicating a possible tendency to migrate and eventually transform into the relatively more stable O-Co3 configuration. These calculations highlight O-Co3 as a structurally robust configuration for AEM full cells under demanding harsh conditions.

Fabrication and characterization of Co triangular order

The O-Co/VN can be fabricated using VN supports with deep-level V vacancies through a photo-induced self-assembly approach (see Fig. 2a). Specifically, the synthesis of O-Co/VN relies on two key factors: i) Deep-level V vacancies. This VN support, fabricated using in-situ conversion of VOx precursor followed by an ammonia annealing (Supplementary Fig. 22), exhibits abundant metal V vacancies, as confirmed by the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 9). Those deep-level V vacancies exhibit a stronger affinity for Co atoms than that of shallow-level N vacancies, thereby forming a stable in-lattice doping structure; ii) In-lattice migration. Under high-power UV irradiation, those Co atoms would migrate within the VN lattice and then assemble into an ordered structure, in line with our calculation (Supplementary Figs. 7–8). In contrast, the VN substrate with shallow-level vacancies only surface-adsorbs Co atoms, which are prone to agglomeration into larger clusters through Ostwald ripening24 during the photochemical process (Fig. 2b).

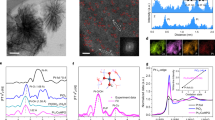

Schematic illustration of the photo-induced in-lattice self-assembly and out-of-lattice adsorption for O-Co/VN (a) and SS-Co/VN (b), respectively. Note that three key points guide the precise synthesis of triangular Co orders: deep-level vacancies, the strong affinity of Co atoms to deep-level vacancies, and in-lattice migration. εd denotes the d-band center. c 3D atomic model with random-depth-doped-Co in the VN supports viewing from direction of <110>. d The pristine STEM-HAADF image of the O-Co/VN sample after the denoised process. e Pixelated intensity distribution analysis of (d). f Atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM image of O-Co/VN processed with Wiener filtering. Green rectangle highlights the region for atomic EELS mapping. g EELS spectra of Co L-edge (top) and V L-edge (bottom). h Elemental maps of Co species acquired from the green square region in (f), confirming the presence of the Co-triangular orders in VN support. Source data for the panel g are provided as a Source Data file.

Then, we employed the aberration-corrected STEM-HAADF to characterize the detailed atomic structures of those samples. It was found that nearly all Co atoms were single-atomically dispersed within the VN-supporting substrate, and Co atoms occupy original V sites in the lattice (Supplementary Fig. 10). Note that the incorporation of Ni and Fe atoms into the VN lattice also presents a lattice-substituted characteristic (Supplementary Figs. 11–14 and Note S2), while nearly all Pt atoms are found to be exclusively supported on the VN surface (Supplementary Fig. 15). Next, two questions regarding Co configurations were raised: (i) Are the Co atoms situated within the VN bulk or on its surface? and (ii) Do the Co atoms in the lattice adopt a triangular arrangement?

For the first question, we developed a 3D atomic model viewed along the <110> direction of a VN doped with Co atoms (Fig. 2c) and performed pixel intensity distribution analysis (see Methods). Our model predicts that Co doping within the bulk alters the column intensity, demonstrating the distinct profile intensities between the red and olive lines (Supplementary Fig. 16). This model was experimentally verified by our pixelated intensity analysis of HAADF-STEM (Fig. 2d, e), further confirming that Co atoms could substitute V sites below the near-surface of the VN supports. In contrast, control experiments in the SS-Co/VN sample show that the Co atoms exhibit a disordered distribution on the VN surface (Supplementary Fig. 17).

For the second question, we performed STEM-EELS elemental analysis of the samples (Fig. 2f), and the corresponding atom-mapping analysis procedure was introduced in Supplementary Fig. 18 and Note S3. Clearly, Co and V atoms present distinct L-edge spectra (approximately 780 eV for Co L edge25 and 516 eV for V L3 edge26), as shown in Fig. 2g, allowing us to distinguish their locations precisely. After mapping the samples (Supplementary Fig. 18), we are able to visualize the spatial distribution of Co and V at the atomic scale, confirming that most Co atoms form triangular arrangements within the VN lattice (Fig. 2h). Furthermore, we also conducted HAADF-STEM image simulations based on DFT-derived atomic models of triangular Co configurations, which closely match our experimental observations above (see Supplementary Fig. 19 for details). Unlike previously reported dimer18 and Ru-atom-array11, this ordered structure exhibits a more complicated coordination environment, in which a triangular configuration is rarely observed in similar atom-ordering system.

Catalytic activity

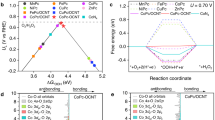

Figure 3a shows the linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) polarization curves of Pt/C, O-Co/VN, SS-Co/VN, and VN catalysts at a scan rate of 5 mV s–1 in 1 M KOH solution after iR correction (Supplementary Fig. 20). Their corresponding Tafel slopes are presented in Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 20b. First, O-Co/VN shows a lower onset potential (347 mV versus RHE) and a smaller Tafel slope (63 mV dec–1) than those of SS-Co/VN (372 mV, 110 mV dec–1), elucidating the enhanced activity of the triangular atom orders. Next, O-Co/VN gives a comparable Tafel slope to commercial Pt/C, with nearly 100% Faradaic efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 21 and Note S4), implying a similar Volmer–Tafel mechanism in HER. Importantly, its current increases exponentially with overpotential, even at a high-current density, indicating a broader linear region of Tafel slopes than that of Pt/C (Fig. 3b). After examining tens of samples in our work, we found that O-Co/VN outperforms commercial Pt/C in alkaline electrolytes, particularly at a high-current density (Fig. 3c).

a 100% iR-corrected LSV polarization curves of various catalysts measured in 1 M KOH electrolyte (pH = 14.0 ± 0.1) at 298 K with a catalyst loading of 1.4 mg cm–2, a scan rate of 5 mV s−1 under continuous Ar flow. The solution resistance (Rs) used for iR correction was 1.9 ± 0.1 Ω (n = 3). b Tafel slope of O-Co/VN and Pt/C catalysts, indicating that O-Co/VN has a larger linear region at high-current densities compared to Pt/C catalysts. c Statistical analysis of Tafel slope and overpotential (vs. RHE) at a current density of 100 mA cm–2 for various catalysts. X and Y error bars denotes the standard deviation of four independent measurements. d Chronopotentiometry measurements of O-Co/VN under stepped current densities ranging from 10 to 1000 mA cm–2 across two cycles. The iR correction was not applied in this measurement. e Chronopotentiometry measurements at high-current densities (500 and 1000 mA cm–2) for 100 h. All potentials were 100% iR-corrected to compensate the solution resistance. Inset is the photograph of O-Co/VN catalysts during hydrogen production at a current density of 500 mA cm–2, showing continuous hydrogen bubbles released from the surface. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next conducted chronopotentiometric measurements to evaluate the durability of the O-Co/VN catalyst at various step current densities—10, 100, 300, and 500 mA cm−2. As shown in Fig. 3d, the catalyst remained stable at each specified potential step, indicating its capability across startup or shutdown operational conditions. It also exhibits good operational stability for 100 hours at 10 mA cm−2 and 1000 mA cm−2, as shown in Fig. 3e, Supplementary Figs. 23–24, and Video 1, 2. In contrast, the SS-Co/VN catalyst exhibits a rapid potential dropping from –1.59 to –3.35 VRHE within two hours at a current density of 500 mA cm−2, as shown in the inset of Fig. 3e. This pronounced degradation is likely attributable to the loss of Co active sites (Supplementary Fig. 25).

Substrate activation mechanism

To gain insights into the above mechanism, we investigated the catalytic activity of ordered Co atoms and their possible influence on adjacent V atoms within the VN substrate. For Co single atoms, we observed an electron transfer process from Co to neighboring V atoms (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 26a), leading to charge redistribution around adjacent V atoms27. Next, we screened all possible ΔGH* values across various sites, which revealed a distance-dependent trend in activity (that is, –0.24 eV of the Co site, –0.59 eV of the adjacent V site, and 0.35 eV of the non-adjacent V site, Fig. 4b). More importantly, this effect appears to be further enhanced in Co-triangular orders. As shown in Fig. 4c, these configurations exhibit a more pronounced electron transfer from Co-triangular orders to adjacent V sites (consistent with XPS analysis in Supplementary Fig. 27), with a distance of up to ~2.8 Å (Supplementary Fig. 30a). As a result, the ΔGH* of adjacent V sites decreases to approximately –0.12 eV, suggesting a possible activation of the V sites within the VN substrate (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 29, and Note S5). Those activated V sites in the substrate, together with the highly-active Co sites (–0.01 eV), are likely to collectively contribute to the enhanced alkaline HER activities observed at high currents in our experiment (see more discussions in Note S6). In stark contrast, in SS-Co/VN catalyst systems, the isolated Co sites exhibit a higher ΔGH* of –0.48 eV and do not appear to effectively activate adjacent V sites (Supplementary Fig. 28).

a Differential charge density plots of the Co single-atom configuration, showing electron aggregation on adjacent V sites. b Schematic distribution of ΔGH* for different metal sites (Co and V) in the Co single-atom configuration. c Differential charge density plots of the Co triangular order, demonstrating increased electron aggregation on adjacent V sites compared with the Co single-atom configuration. d Schematic distribution of ΔGH* for Co and V sites within the Co-triangular order configuration. e Ex-situ EXAFS spectra of O-Co/VN catalyst at –0.509 V and –0.709 V vs. RHE during the HER process. f The exponential increase of electrochemical surface area (ECSA) of O-Co/VN catalysts with the proportion of Co-triangular orders. Inset: the fitted equation relating ECSA to Co atomic fraction. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent measurements. g Schematic illustrating the expansion of the catalytically active surface with an increasing fraction of Co-triangular order, showing the potential to develop a fully active surface on the substrate. h Schematics depicting the nanobubble imaging with the on-chip TIRF microscopy, where the fluorescence probe (R6G) was used to pinpoint the nanobubbles formed onto the O-Co/VN catalyst. Super-resolution images for the VN (i) and O-Co/VN (j) catalysts, where the green dots denote the formed nanobubbles on their respective surfaces. Inset: the corresponding bright-field images. The red dashed rectangles mark the regions used for nanobubble density analysis in subsequent steps. k Calculated nanobubble densities for the VN and O-Co/VN at the boxed region in (i, j), revealing a significantly higher density of O-Co/VN than pristine VN. Source data for the panel e, f, and k are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, we carried out ex-situ XAS to verify this activation behavior of V sites in the substrate, as shown in Fig. 4e. Besides initial Co–N coordination, the O-Co/VN catalyst exhitits an additional Co–V coordination at a radial distance of approximately 2.6 Å at –0.509 and –0.709 VRHE. This N5–Co–V2 coordination was further corroborated through extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) fitting analysis (Supplementary Fig. 34 and Table 2). Its specific coordination pattern around the Co-triangular site can be clearly visualized in wavelet transform spectra (Supplementary Fig. 33). Such Co-V coordination likely arises from strong electronic interactions between the Co triangular motifs and adjacent V sites, enabling electrochemically induced coordination reconfiguration28. This finding suggests that the Co-triangular order can effectively modulate the coordination environment of adjacent V atoms, contributing to the adjacent activation effect described above.

It is compelling to see how this adjacent activation behavior enlarges the number of V active sites. By progressively increasing the Co atomic fractions, we leveraged DFT calculations (top panel of Fig. 4f) to screen all possible V active sites generated in the O-Co/VN catalyst. Notably, the number of activated V sites was found to increase exponentially with the Co ratio, which agree well with the experimental trends observed from electrochemical surface area (ECSA) analysis (bottom panel of Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 31, and Table 4). These results suggest the potential feasibility of constructing a fully catalytic surface of the VN substrate, as illustrated in Fig. 4g. In contrast, the SS-Co/VN catalyst shows a linear increase in active site density, indicating that Co atoms likely serve as the primary active sites in the alkaline HER process.

To verify the Co-activated surface of VN, we employed our recently developed on-chip total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy system29,30. Briefly, it integrates super-resolution TIRF imaging with single-entity, synchronized electrochemical control in a microcell (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 36). Under applied bias, in-situ generated nanobubbles adsorb R6G fluorophores and produce photo-switchable fluorescence bursts within the evanescent field (Supplementary Fig. 37a, b), thereby capable of probing catalytic sites on O-Co/VN thin films (~5 nm thick, Supplementary Fig. 39). This approach achieves a temporal of 16.7 ms and spatial resolution of ±29 nm (Supplementary Fig. 37c). For pristine VN, we observed minimal nanobubble formed on its surface, reveals only sparse active sites (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Fig. 40). In contrast, O-Co/VN exhibited dense, homogeneous nanobubble formation (Fig. 4j and Supplementary Fig. 41) with ~600-fold higher density than VN (Fig. 4k), indicating that triangularly ordered Co sites transform the VN surface into a highly active catalytic interface.

Full cell in operational conditions

We next fabricated an AEM water-electrolyzer full cell with O-Co/VN as the cathode (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 42a). Figure 5b and Supplementary Fig. 42b present the cells’ Nyquist plots and the corresponding fitted data at an applied potential of 1.6 V at 60 °C. Note that Rs, Rct,anode, and Rct,cathode denote the impedance of the electrolyte, anode, and cathode31, and constant phase elements CPEanode and CPEcathode as the anode and cathode capacitances, respectively32. The O-Co/VN cell exhibits an Rs of 0.05 Ω and an Rct,cathode of 0.23 Ω (Supplementary Table 3). Figure 5c presents the IV outputs of the assembled cell at 60 °C, achieving a voltage as low as 1.97 V at a current density of 500 mA cm–2. Notably, this performance surpasses that of the Pt/C-based cell (2.19 V) and is competitive with previously reported systems (Supplementary Fig. 43 and Table 5)33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. More importantly, the long-term tests demonstrated a stable operation for over 660 h, with a slight degradation rate of 0.13 mV h–1, demonstrating stable operation of this cell (Fig. 5d).

a Schematic representation of the AEM electrolyzer. The cathode and anode catalysts are O-Co/VN and IrO2, respectively. b Schematic of the equivalent circuit used for fitting the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data, along with the corresponding EIS fitting parameters of the assembled cells. c IV outputs of the assembled cell operating at 60 °C. d Chronopotentiometry measurement of the assembled cells at 500 mA cm−2 at 60 °C, showing slight voltage loss for long-term working. e, EDX elemental map of after-cycling O-Co/VN catalyst, indicating the Co sites are well preserved after long-term cycling. f Left panel: HAADF-STEM images of post-cycling the O-Co/VN catalyst. The blue dashed rectangle marks the zoomed-in region. Right panel: Zoomed-in HAADF-STEM views and corresponding 3D surface plots for the regions of Pos 1 and 2. The blue dashed triangulars highlight the Co-triangular motifs. Source data for the panel c and d are provided as a Source Data file.

Finally, we examined the atomic and electronic structures of the post-operation O-Co/VN catalyst. Figure 5e and Supplementary Fig. 44 show the elemental mapping of post-operation samples, confirming that Co species remain well dispersed. The high-magnification STEM and corresponding 3D surface renderings (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 45) verified the preservation of triangular orders in the post-operation samples. The XRD pattern (Supplementary Fig. 47a) shows only VN diffraction peaks with no Co signals. The high-resolution Co 2p XPS (Supplementary Fig. 47b) exhibits no Co0 species, indicating the absence of Co–Co bonding formed during operation. Taken together, those results demonstrated that in-lattice Co triangular orders and the activated VN support could sustain the harsh conditions in practical applications.

Discussion

We have developed a Co triangular order catalyst using a lattice-substitution atom-ordering strategy and successfully applied it to a practical AEM. Our calculations revealed that these in-lattice Co-atom orders exhibit enhanced structural stability than conventional surface-supported single atoms or nanoclusters. The precisely controlled triangular arrangement of Co atoms serves two critical functions: i) it activates adjacent V atoms, optimizing hydrogen-binding energy to enhance alkaline HER activity, particularly at high overpotentials; ii) it enables the in-lattice Co atoms and their surrounding activated VN support to sustain industrial-level alkaline HER conditions (≥1000 mA cm–2 over 100 hours). Finally, thanks to those advantages, the assembled AEM full cell achieved a lower cell voltage (i.e., 1.97 V at 500 mA cm–2) and comparable long-term stability to Pt/C-based cells. This work provides insight into the role of atom ordering in catalytic reactions and its interaction with supporting materials, paving the way for designing active and durable catalysts under practical operating conditions.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

NH4VO3 (≥99.9%), oxalic acid dihydrate (≥ 99%), commercial Pt/C (20 wt% Pt, and 40 wt% Pt), Co(NO3)2·6H2O ( ≥ 99%), H2PtCl6·6H2O (≥99.9%), KOH (≥95%), and Fe(NO3)2·9H2O (≥99.9%) were purchased from Macklin Reagent. Hexamethylene tetramine, isopropyl alcohol, and Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (≥99%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. The 5 wt% Nafion 117 solution (Reagent Grade) and commercial vanadium nitride powerder (≥99.5%) were purchased from Shanghai Adamas Reagent Co., Ltd. Commercial IrO2 was purchased from Suzhou Sinero Technology Co., Ltd.

Preparation of VN supporting substrate

VN support was obtained by a two-step method as reported by our previous publication21,44. First, the VOx precursor was fabricated through a hydrothermal method. 2.52 g NH4VO3, 6.30 g Oxalic acid dihydrate, and 0.70 g hexamethylene tetramine were dissolved in 50 mL deionized water (DI) water (10 MΩ) and continuously stirred for 15 min to form a uniform dark-green solution. The above solution was transferred into an autoclave. The reaction was continued for 1 h at 150 °C, and the powders were collected by vacuum filtration and dried in an oven at 60 °C. Next, the VOx precursor was annealed under an ammonia atmosphere to in-situ convert to VN materials. Specifically, the products were annealed at 500 °C for a long time of 4 h in the Ar (100 standard cubic centimeter per minute, sccm) and NH3 (100 sccm) atmosphere.

Preparation of O-Co/VN, Pt SA/VN, LS-Ni/VN, and LS-Fe/VN

The transition-metal-based atomically dispersed catalysts were synthesized via a photochemical method45,46,47. In a typical process, firstly, the 20 mmol L–1 Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 1 mmol L–1 H2PtCl6·6H2O, 5 mmol L–1 Fe(NO3)2·9H2O and 5 mmol L–1 Ni(NO3)2·6H2O were dissolved into a mixed solution containing DI water and alcohol with a volume ratio of 1:19, 1:19, 1:3, and 1:3 as the precursor of O-Co/VN, surface-supported Pt (Pt SA/VN), lattice-substituted Fe (LS-Fe/VN), and lattice-substituted Ni (LS-Ni/VN) catalysts, respectively. Then, ~30 mg VN powder was dispersed into 5 mL precursor solution and ultrasonically dispersed for 5 min at a power of 500 W to form a uniform solution. Next, the obtained solution was irradiated by UV light (wavelength: 365 nm) for 1 h at a power density of 4.8 mW cm–2 (determined by UV intensity meter ST-513 purchased from SENTRY OPTRONICS CORP.). After that, the products were collected by centrifugation and further dried in an oven at 60 °C overnight. Note that O-Co/VN with different Co loadings were also synthesized by varying the concentration of the Co precursor. Specifically, 1 mmol L–1, 5 mmol L–1, and 10 mmol L–1 Co(NO3)2·6H2O precursors were used.

As a comparison, VN materials synthesized at 900 °C and commercial VN were also utilized as supporting substrates to prepare Co-ordered catalysts. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 22, these materials exhibited inferior catalytic activities compared to the O-Co/VN catalyst, underscoring the crucial role of supports in the self-assembly process. Notably, the Co metal mass loading is well-controllable in our experiment, such as 1.00 wt%, 1.67 wt%, 2.52 wt%, and 4.42 wt%, as examined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) and X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) measurement, as shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Preparation of SS-Co/VN catalyst

The process of SS-Co/VN preparation is as follows: first, defect sites on the support are crucial for substitutional Co formation, so in order to prepare SS-Co/VN catalysts, we chose the commercial VN with fewer defects as the support. Second, in order to avoid the Co precursor absorbing UV energy embedded in the VN lattice during the light irradiation process, we used ice photoreduction to increase the single-atom Co amount in precursor solution during the UV irradiation process, as previously reported45. The specific procedure was as follows: i) 20 mM Co(NO3)2 ∙ 6H2O precursor aqueous solution was rapidly frozen into ice with liquid nitrogen. ii) the above ice containing Co precursor was placed in a dark environment in an ultra-low-temperature refrigerator at –40 °C, and UV irradiation was carried out for 1 h at a power density of 4.8 mW cm–2 (same as the preparation of O-Co/VN sample). iii) The ice was naturally melted to obtain the Co single-atom solution after the end of irradiation. After that, we fully mixed and dispersed the above Co single-atom solution with commercial VN supports, and further obtained the SS-Co/VN by centrifugal filtration procedure.

Theoretical simulation

The calculations were performed within the framework of density-functional theory (DFT) with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional48, and the vacuum space was set to 20 Å to eliminate spurious interactions between the two surfaces in the neighboring period images. The lattice parameters of the supercell are a = 17.16 Å, b = 17.16 Å, c = 20.00 Å. The core electron-ion interactions were described by projected broadening wave potentials with the cutoff energy of the plane wave base set to 450 eV48,49. The Brillouin zone integrals were optimized using 4 × 4 × 1 k points for structure optimization, and 16 k points for electron calculations. Atomic positions were optimized until the maximum force on each atom was less than 0.01 eVÅ–1. All computational atomic models in DFT calculations are provided in Supplementary data 1.

Calculation of ∆G H

Gibbs free energy (∆G) for the HER reaction was also calculated using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof generalized gradient approximation. In this set of calculations, the kinetic energy cutoff for plane-wave expansion was set to 500 eV. For the HER reaction, ∆G at 300 K was calculated as:

where ∆E is the energy of adsorption of hydrogen atoms on the system with respect to the gas phase, T is the temperature, ΔS is the entropy of the H atoms adsorbed on the substrate, and ∆EZPE is the zero-point vibrational energy. The vibrational analysis of the adsorbate was performed using the harmonic approximation, with the gas-phase reference molecule as the ideal.

Calculation of migration energy barriers

The migration energy barriers were calculated using the climbing image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method50,51. A plane-wave energy cutoff of 450 eV was applied. The convergence criterion for the electronic self-consistent loop was set to 1 × 10–5 eV. Geometry optimizations were carried out using the quasi-Newton algorithm in conjunction with the CI-NEB method, employing the Limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (LBFGS) optimization scheme. A spring force constant of –5 eV Å–2 was used, and one intermediate image was inserted between the initial and final states. The Brillouin zone was sampled using a 3 × 3 × 1 Monkhorst–Pack k-point grid.

Implicit solvent modeling

To investigate solvation effects, calculations were performed using the implicit solvation model implemented in VASPsol52,53. An energy cutoff of 450 eV and a convergence threshold of 1 × 10–5 eV were adopted. Ionic relaxation was carried out using the conjugate gradient algorithm. The solvation model was enabled, with a dielectric constant of 78.4 to mimic water. The Brillouin zone was sampled using a 3 × 3 × 1 k-point mesh.

Calculation of differential charge density

The differential charge density of O-Co/VN with Co single atom and triangle order was calculated using the equation below:

where ρtotal, ρVN, and ρCo are the differential charge density of O-Co/VN, VN substrate, and individual Co single atom/triangular order, respectively.

Calculation of binding energy

The binding energy (Eb) was calculated as:

where Etotal is the total energy of the Co/VN system, Eslab is the energy of the VN substrate, and ECo-atoms is the energy of free-standing Co atoms.

Electrochemical measurement

Three-electrode measurement

The HER performance was evaluated by using a conventional three-electrode configuration on an electrochemical workstation (Wuhan Corrtest Instrument Corp., Ltd) in Ar-saturated 1 M KOH solution (pH = 14.0 ± 0.1). Note that 1 M KOH solution was freshly prepared before each electrochemical test by dissolving KOH pellets (≥95%) in deionized water (18 MΩ·cm) at room temperature (298 K) and stored in a tightly sealed polypropylene container to minimize CO2 contamination. The pH value corresponds to the theoretical value of a 1 M strong base assuming complete dissociation of KOH. A Hg/HgO (1 M KOH) electrode and a carbon rod were employed as the reference and counter electrode. In a typical fabrication procedure of a working electrode, the catalytic ink was first prepared via dispersing 10 mg O-Co/VN (or LS-Ni/VN, or LS-Fe/VN) catalyst into a 1 mL mixed solution containing isopropyl alcohol and DI water with a volume ratio of 4:1, with 30 μL 5 wt% Nafion solution as a binder. After ultrasonication for 1 h, the 10 μL catalytic ink was dropped on the glass carbon electrode (diameter: 3 mm) or carbon cloth substrate (35.7 μL, 0.25 cm2) and dried in the air at 298 K (mass loading = 1.4 mg cm–2). For further XAS characterization, the catalytic ink was dropped onto the carbon cloth electrode with a mass loading of 2 mg cm–2. LSV curves were tested in the potential range from 0 to –0.75 V versus RHE at a scan rate of 5 mV s–1 for HER. The employment of such a low scan rate is beneficial for approaching steady state and mitigating the mass transfer limitations at the catalyst–electrolyte interface54,55,56. And the LSV curves were corrected using the equation below:

where Rs refers to the solution impedance, Epristine is the measured potential in the LSV curves. The Hg/HgO electrode was calibrated by using the Pt wire and carbon rod as working and counter electrodes to measure the open circuit potential under a continuous H2 atmosphere57. It worth noting that the Rs of the electrochemical cell was determined by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) at open-circuit potential in the frequency range of 0.1 Hz–100 kHz. The Rs value was obtained from the high-frequency intercept of the Nyquist plot and was measured to be 1.9 ± 0.1 Ω (n = 3). Data analysis and plotting were performed using OriginPro (OriginLab, USA).

In 1 M KOH, the potential can be calibrated using this Equation:

where ERHE and EHg/HgO are the potential of the RHE and Hg/HgO electrode, respectively. The EIS measurement was conducted at different constant potentials (versus RHE) and a frequency range of 0.1–100 kHz with an amplitude of 5 mV.

The HER durability of catalysts was firstly evaluated through a stepwise chronoamperometry method for 100 h in Ar-saturated 1 M KOH electrolyte at a current density range from –10 mA cm–2 to –500 mA cm–2. To avoid interfacial disturbances associated with current density transitions, a one-hour holding period was introduced when the current density was reduced back to –10 mA cm–2 after high-current operation. Concerning the long-term stability under industrial current density, the chronoamperometry method was also conducted for 100 h at different constant current densities, including –10, –300, –500, and –1000 mA cm–2, where the measurement at both –500 and –1000 mA cm–2 is an indicator to evaluate the catalyst lifetime under ampere-level operational conditions. To ensure that the stability performance corresponds accurately with the activity curves in LSV measurements, an 100% iR correction (Supplementary Fig. 23) was applied to the stability curves of O-Co/VN. Notably, the rapid hydrogen production will result in massive consumption of electrolytes at the industrial current density. Thus, the electrolyte must be continuously pumped into the electrolytic cell using a peristaltic pump (United Zhongwei Technology Co., Ltd.).

ECSA measurement

In an argon gas-saturated 1 M KOH electrolyte, cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves were recorded across a potential range of 1.1–1.2 VRHE at varying scan rates (10, 20, 50, 100, and 200 mV s–1). The absence of Faraday processes dictated the chosen potential range. Utilizing the middle potential of this range as a reference and the average of the anode and cathode currents to define the double-layer capacitance current (iC), a plot of iC versus the scan rate v illustrates a direct linear relationship, that is:

where the slope corresponds to Cdl. The value of Cdl is directly proportional to the catalyst’s ECSA.

Given that an ideal flat electrode’s electric double-layer capacitance (Cs) ranges from 20 to 60 μF cm–2, ECSA can be deduced from Cdl using the Equation below, with Sgeo representing the electrode’s geometric area.

AEM full cell measurement

The anion exchange membrane (AEM) water electrolyzer was assembled with two bipolar plates, two Ti substrates, and a membrane electrode assembly (MEA). The effective electrode area is about 2 × 2 cm2. The cell was equipped with an H2O inlet, an H2/H2O outlet, and an O2 outlet to facilitate the supply of the electrolyte (1 M KOH) and the collection of H2 and O2, respectively. The MEA was composed of an anode, a cathode catalyst, and an anion exchange membrane (Alkymer, W-75, 75 µm thick, 3 × 3 cm2, EVE Energy Co., Ltd.). Commercial IrO2 (2.5 mg cm–2) and O-Co/VN (or 40 wt% Pt/C, 1.0 mg cm–2) served as the anode and cathode catalysts, respectively. Prior to cell assembly, the anion exchange membrane was pretreated by soaking in 1 M KOH for 24 h. The electrolyte is a 1 M KOH solution, and all of the measurements were conducted at a temperature of 60 °C. The EIS measurement of the AEM electrolyzer was conducted at an applied voltage of 1.6 V, and the range of frequency varied from 0.1 to 1 × 105 Hz.

Material characterizations

STEM imaging

The scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM, JEOL ARM-300F equipped with a CEOS CESCOR aberration corrector operated at 300 kV and ThermoScientific Themis Z operated at 300 kV) was used to examine the single-disperse characteristics of our samples. A nonlinear filtering script (NLFilter) was utilized to enhance the contrast of single atoms in the STEM-HAADF images58.

XPS

XPS measurement was carried out on Thermo SCIENTIFIC ESCALAB 250XiV instrument, with an energy range of −10 to 5000 eV, a spatial resolution of 3 μm, and an energy resolution of 0.45 eV.

XAS

The synchrotron XAFS spectroscopy measurements were conducted at the QAS beamline (8-BM) of the National Synchrotron Light Source II. Co K-edge XAS spectra of O-Co/VN, Co foil, CoPc, and Co3O4 were obtained in transmission mode. The XAS spectra for Co were captured in the range of 7550 to 8350 eV, employing a Si(111) monochromator. To improve the signal-to-noise ratio, the spectra were averaged from about 25 individual spectra. All XAS spectra were normalized and analyzed using the Athena and Artemis software packages59. Notably, the fitting process includes the following steps60,61,62,63: i) Fourier-transformed EXAFS spectra were first obtained in R-space from the raw Co K-edge data; ii) The fitting was conducted in both R-space and k-space using standard EXAFS fitting procedures via Artemis software. iii) The fitting models were constructed based on the following coordination possibilities: Co–N, Co–Co, and Co–V; iv) The fitting parameters—including coordination number (CN), bond distance (R), Debye–Waller factor (σ2), and energy shift (ΔE0)—were optimized within physically reasonable limits. The wavelet transform of EXAFS spectra was conducted using the hamaFortran software.

ICP-OES

The accurate metal mass loading was determined by ICP-OES characterization on Agilent ICP-OES 725 ES. In a typical procedure, the different catalysts (about 20 mg) were dissolved in the boiling aqua regia for 10 min to digest all the moieties (including VN supports) and further to form the homogeneous solution.

Ex-situ TEM

The ex-situ TEM was conducted on JEM-ARM 300 F at an operating voltage of 300 kV. The aqueous dispersion solution of O-Co/VN catalysts was dropped onto the TEM Au grid coated carbon film (300 mesh, purchased from Beijing Zhongjingkeyi Technology Co., Ltd.), which is immobilized by a hollow polytetrafluoroethylene cap on the surface of a glass carbon electrode. The accelerated degradation tests were carried out by using a continuous CV scan for 5000 cycles at an overpotential range from 0.027 to –0.423 V versus RHE in Ar-saturated 1 M KOH electrolyte at 298 K.

Atomic-image simulation and processing

The simulations of the HAADF-STEM images were performed with the Dr.Probe software64, and the simulation parameters were fixed based on the experimental conditions. The intensity values of the atomic column in the simulated HAADF-STEM images and experimental images were determined with the help of the CalAtom package65, in which the thermally colored 3D intensity distribution maps were derived.

EPR

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) measurements were conducted using Bruker A300 instrument with a central magnetic field of 3500 G, a field scan width of 200 G, a scan duration of 30 s, microwave power of 19.45 mW, modulation amplitude of 1.00 G, transition time of 40 ms, and operating frequency of 9.85 GHz.

AFM

The surface height profile of the O-Co/VN thin film was obtained using an Atomic Force Microscope (AFM, Park Systems NX10) at a scan rate of 0.5 Hz and a resolution of 256 × 256 pixels.

In-situ nanobubble visualization

Super-resolution imaging

In-situ nanobubble visualization was achieved through on-chip TIRF microscopy, which integrates a total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti-U) with electrochemical measurements (Supplementary Fig. 36). The TIRF setup enabled super-resolution imaging, while the on-chip microcell facilitated electrochemical stimulation. As depicted in O-Co/VN thin films (or VN thin films) were transferred onto indium tin oxide-coated coverslips (thickness: #1.5, 22 × 22 mm, 15–30 Ω, SPI Supplies) using a PMMA-assisted wet-transfer method as the imaging catalysts66. The standard experimental protocol is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 38. Super-resolution imaging relied on the photo-switchable properties of the R6G fluorophore via the Point Accumulation for Imaging in Nanoscale Topography (PAINT) technique. A 532 nm laser (100 W max) excited R6G molecules on nanobubbles formed at the catalyst surface. A translation stage adjusted the laser beam to achieve wide-field TIR illumination, creating an evanescent field extending several tens of nanometers into the electrolyte—key for selectively visualizing near-surface fluorophores with minimal background67. A band-pass emission filter (ET605/70 m, Chroma) reduced background noise. Emissions were captured using an oil-immersion objective (f = 75 mm, Nikon Plan Apo λ 100×, NA 1.45), and videos were recorded by an electron multiplying charge-coupled device (EMCCD) camera (Andor iXon3) cooled to –70 °C, with gain = 300, 60 Hz frame rate (16.7 ms resolution), and 256 × 256 pixels (160 nm per pixel).

Electrochemical coupling

Simultaneously, chronoamperometry (–0.329 V vs. RHE for 180 s), LSV (0.221 to –0.479 V at 10 mV s–1), and CV (same range and rate) were performed to drive the HER. The electrolyte used was 1 M KOH with 5 nM R6G.

Image analysis

Raw imaging data were analyzed using custom-written software to construct super-resolution maps. Stage drift was corrected using MATLAB-based scripts68. A signal threshold slightly above background noise was set to identify single-molecule fluorescence events.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the conclusions of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kang, X. et al. A corrosion-resistant RuMoNi catalyst for efficient and long-lasting seawater oxidation and anion exchange membrane electrolyzer. Nat. Commun. 14, 3607 (2023).

Seh, Z. W. et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: insights into materials design. Science 355, eaad4998 (2017).

Du, N. et al. Anion-exchange membrane water electrolyzers. Chem. Rev. 122, 11830–11895 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Advances of layered double hydroxide electrocatalysts for high-current-density alkaline water/seawater splitting. Coord. Chem. Rev. 510, 215832 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Oriented transformation of Co-LDH into 2D/3D ZIF-67 to achieve Co–N–C hybrids for efficient overall water splitting. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1803918 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. Anion-exchange membrane water electrolyzers and fuel cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 9620–9693 (2022).

Lazaridis, T., Stühmeier, B. M., Gasteiger, H. A. & El-Sayed, H. A. Capabilities and limitations of rotating disk electrodes versus membrane electrode assemblies in the investigation of electrocatalysts. Nat. Catal. 5, 363–373 (2022).

Wang, C.-M., Wang, Y.-D., Ge, J.-W. & Xie, Z.-K. Reaction: industrial perspective on single-atom catalysis. Chem 5, 2736–2737 (2019).

Zhu, W. & Chen, C. Reaction: open up the era of atomically precise catalysis. Chem 5, 2737–2739 (2019).

Li, X., Huang, Y. & Liu, B. Catalyst: single-atom catalysis: directing the way toward the nature of catalysis. Chem 5, 2733–2735 (2019).

Lin, C. et al. In-situ reconstructed Ru atom array on α-MnO2 with enhanced performance for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Catal. 4, 1012–1023 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Periodic one-dimensional single-atom arrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15999–16005 (2022).

Qi, K. et al. Single-atom cobalt array bound to distorted 1T MoS2 with ensemble effect for hydrogen evolution catalysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 5231 (2019).

Lu, X. et al. Ordered single active sites for cascade hydrogenation and hydroformylation reactions. Nat. Catal. 8, 536–547 (2025).

Chen, L.-W. et al. Structurally ordered intermetallic Ir3V electrocatalysts for alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Nano Energy 81, 105636 (2021).

Yin, P. et al. Machine-learning-accelerated design of high-performance platinum intermetallic nanoparticle fuel cell catalysts. Nat. Commun. 15, 415 (2024).

Saravanan, G., Nanba, K., Kobayashi, G. & Matsumoto, F. Leaching tolerance of anodic Pt-based intermetallic catalysts for formic acid oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 99, 15–21 (2013).

Lin, C. et al. Creating atomic ordering in electrocatalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2212827 (2023).

Ren, Y. et al. Locally Ordered Single-Atom Catalysts for Electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. 136, e202315003 (2024).

Xiao, W., Lei, W., Gong, M., Xin, H. L. & Wang, D. Recent Advances of Structurally Ordered Intermetallic Nanoparticles for Electrocatalysis. ACS Catal. 8, 3237–3256 (2018).

Ma, M. et al. Role of N in transition-metal-nitrides for anchoring platinum-group metal atoms toward single-atom catalysis. Small Methods 6, 2200295 (2022).

Greeley, J. & Mavrikakis, M. Alloy catalysts designed from first principles. Nat. Mater. 3, 810–815 (2004).

Kumar, A. et al. Iridium single-atom-ensembles stabilized on Mn-substituted spinel oxide for durable acidic water electrolysis. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401648 (2024).

Hu, S. & Li, W.-X. Sabatier principle of metal-support interaction for design of ultrastable metal nanocatalysts. Science 374, 1360–1365 (2021).

Jin, H. et al. Unprecedentedly high activity and selectivity for hydrogenation of nitroarenes with single atomic Co1-N3P1 sites. Nat. Commun. 13, 723 (2022).

Kim, S. J. et al. New insights into the reaction mechanism of sodium vanadate for an aqueous Zn ion battery. Chem. Mater. 32, 2053–2060 (2020).

Dai, J. et al. Single-phase perovskite oxide with super-exchange induced atomic-scale synergistic active centers enables ultrafast hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 11, 5657 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Rapid complete reconfiguration induced actual active species for industrial hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 13, 5785 (2022).

Guo, S. et al. Nanoscale identification of local strain effect on TMD catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 31920–31926 (2024).

Guo, S. et al. Separating nanobubble nucleation for transfer-resistance-free electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 16, 919 (2025).

Vincent, I., Lee, E.-C. & Kim, H.-M. Comprehensive impedance investigation of low-cost anion exchange membrane electrolysis for large-scale hydrogen production. Sci. Rep. 11, 293 (2021).

Gateman, S. M. et al. On the use of a constant phase element (CPE) in electrochemistry. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 36, 101133 (2022).

Zeng, L. & Zhao, T. S. Integrated inorganic membrane electrode assembly with layered double hydroxides as ionic conductors for anion exchange membrane water electrolysis. Nano Energy 11, 110–118 (2015).

Thangavel, P. et al. Graphene-nanoplatelets-supported NiFe-MOF: high-efficiency and ultra-stable oxygen electrodes for sustained alkaline anion exchange membrane water electrolysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 3447–3458 (2020).

Pavel, C. C. et al. Highly efficient platinum group metal free based membrane-electrode assembly for anion exchange membrane water electrolysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 1378–1381 (2014).

Thangavel, P. et al. Immobilizing low-cost metal nitrides in electrochemically reconstructed platinum group metal (PGM)-free oxy-(hydroxides) surface for exceptional OER kinetics in anion exchange membrane water electrolysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203401 (2023).

Qian, S. et al. Tailoring coordination environments of single-atom electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution by topological heteroatom transfer. Nat. Commun. 15, 2774 (2024).

Park, E. J. et al. How does a small structural change of anode ionomer make a big difference in alkaline membrane fuel cell performance? J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 25040–25046 (2019).

Wang, K. et al. Kinetically accelerating elementary steps via bridged Ru-H state for the hydrogen-evolution in anion-exchange membrane electrolyzer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2212321 (2023).

Ul Hassan, N. et al. Understanding recoverable vs unrecoverable voltage losses and long-term degradation mechanisms in anion exchange membrane fuel cells. ACS Catal. 12, 8116–8126 (2022).

Zeng, L. et al. Anti-dissolution Pt single site with Pt(OH)(O3)/Co(P) coordination for efficient alkaline water splitting electrolyzer. Nat. Commun. 13, 3822 (2022).

Ngo, Q. P., Nguyen, T. T., Le, Q. T. T., Lee, J. H. & Kim, N. H. Unveiling the synergistic effect of atomic iridium modulated zirconium-doped pure phase cobalt phosphide for robust anion-exchange membrane water electrolyzer. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301841 (2023).

Lim, W.-G. et al. Toward feasible single atom-based hydrogen evolution electrocatalysts via artificial ensemble sites for anion exchange membrane water electrolyzer. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 343, 123568 (2024).

Ma, M. et al. High-performance 3 V “water in salt” aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors based on VN nanowire electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 4827–4835 (2020).

Wei, H. et al. Iced photochemical reduction to synthesize atomically dispersed metals by suppressing nanocrystal growth. Nat. Commun. 8, 1490 (2017).

Li, T., Liu, J., Song, Y. & Wang, F. Photochemical solid-phase synthesis of platinum single atoms on nitrogen-doped carbon with high loading as bifunctional catalysts for hydrogen evolution and oxygen reduction reactions. ACS Catal. 8, 8450–8458 (2018).

Wei, H. et al. Ultralow-temperature photochemical synthesis of atomically dispersed Pt catalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Sci. 10, 2830–2836 (2019).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978–9985 (2000).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Mathew, K., Sundararaman, R., Letchworth-Weaver, K., Arias, T. A. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit solvation model for density-functional study of nanocrystal surfaces and reaction pathways. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 084106 (2014).

Mathew, K., Kolluru, V. S. C., Mula, S., Steinmann, S. N. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit self-consistent electrolyte model in plane-wave density-functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 234101 (2019).

Anantharaj, S., Noda, S., Driess, M. & Menezes, P. W. The pitfalls of using potentiodynamic polarization curves for Tafel analysis in electrocatalytic water splitting. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 1607–1611 (2021).

Zhang, S.-N. et al. Ampere-level reduction of pure nitrate by electron-deficient Ru with K+ ions repelling effect. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–12 (2024).

Du, D. et al. Mesoporous PdBi nanocages for enhanced electrocatalytic performances by all-direction accessibility and steric site activation. Chem. Sci. 13, 3819–3825 (2022).

Lee, J. G. et al. A new family of perovskite catalysts for oxygen-evolution reaction in alkaline media: BaNiO3 and BaNi0.83O2.5. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 3541–3547 (2016).

Du, H. A nonlinear filtering algorithm for denoising HR(S)TEM micrographs. Ultramicroscopy 151, 62–67 (2015).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Wang, P. et al. Atomically dispersed cobalt catalyst anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon nanosheets for lithium-oxygen batteries. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–11 (2020).

Yin, P. et al. Single cobalt atoms with precise N-coordination as superior oxygen reduction reaction catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 10800–10805 (2016).

Koningsberger, D. C., Mojet, B. L., van Dorssen, G. E. & Ramaker, D. E. XAFS spectroscopy; fundamental principles and data analysis. Top. Catal. 10, 143–155 (2000).

Sarma, B. B., Maurer, F., Doronkin, D. E. & Grunwaldt, J.-D. Design of single-atom catalysts and tracking their fate using operando and advanced X-ray spectroscopic tools. Chem. Rev. 123, 379–444 (2023).

Barthel, J. Dr. Probe: a software for high-resolution STEM image simulation. Ultramicroscopy 193, 1–11 (2018).

Zhang, Q., Zhang, L. Y., Jin, C. H., Wang, Y. M. & Lin, F. CalAtom: a software for quantitatively analysing atomic columns in a transmission electron microscope image. Ultramicroscopy 202, 114–120 (2019).

Pham, P. V. et al. Transfer of 2D films: from imperfection to perfection. ACS Nano 18, 14841–14876 (2024).

Fish, K. N. Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. Curr. Protoc. 2, e517 (2022).

Chan, J. X., Wu, S., Lee, J.-K., Ma, M. & Zhang, Z. Effect of strain on the photocatalytic reaction of graphitic carbon nitride: insight from single-molecule localization microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 851–861 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Y. He acknowledges the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1500900), the open research fund of Songshan Lake Materials Laboratory (2023SLABFN08), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023A1515012648), the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities (531119200209), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China (2023JJ10004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52203354 and 22272048). Z.L. acknowledges the support from French National Program France 2030, under the French National Research Agency (ANR), project ADVANCE n°23-PEXD-0001, and Singapore Ministry of Education AcRF Tier 2 (MOE2019-T2-2-105, MOE-T2EP10224-0005). This work was also supported by the Hundred Talents Program (B) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (E2XBRD1) and Science and Technology Commission Foundation of Shanghai (25ZR1401378). This research used the QAS beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source II, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H. and M.M. conceived and designed the project. M.M., Z.S., Z.X., and X.S. fabricated the electrocatalysts. M.M., S.G., and H.X. carried out the physicochemical characterizations. M.M. and M.Q. conducted the conventional three-electrode electrocatalytic measurement. H.G., Y.Z., M.Q., C.H., and S.W. carried out the assembly and measurement of an anion exchange membrane water splitting electrolyzer. B.Z., S.X., Z.Y., C.G., Ž.Š., and L.L. performed all the DFT calculations. J.F., Y.Z., and P.T. performed the atomic-resolution STEM characterization. E.X., Z.L., and Y.H. supervised this study and the writing of this manuscript. M.M. and B.Z. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all the co-authors. Z.Z. provided the instrumental support for the TIRF imaging platform. F.S. and H.W. fabricated the VN thin films.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, M., Zhao, B., Gao, H. et al. Triangular-ordered Co atoms activate substrates for ampere-level durable hydrogen production. Nat Commun 17, 144 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66837-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66837-y