Abstract

From bees to blue whales, it has long been assumed that brain size scales with body size according to a simple log-linear relationship – with differences in the slope and intercept observed amongst different groups of animals. However, recent analyses in mammals contradict this view, revealing size dependency in the form of curvature in the brain and body mass relationship. Here, we use data from 4679 species across seven animal classes and spanning nearly 12 orders of magnitude to uncover near universal curvilinearity. We demonstrate that this body size dependence is a metaphenomenon emerging from a pattern of diminishing allometry within species with increasing body mass. This has fundamental implications for how we interpret macroevolutionary patterns – which can arise as a consequence of within-lineage dynamics. Our integration of inter- and intra-specific allometries reshapes perspectives on morphological evolution by providing a broader framework for understanding how microevolutionary within-species dynamics shape macroevolutionary phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

From bees to blue whales, how and why variation in brain size among animal species arose has received a lot of attention over the years e.g.1,2,3,4,5,6. It is widely recognized that the strong correlation with body size is a key consideration in understanding macroevolutionary patterns in brain size. For nearly a century, the relationship between brain and body size has been almost universally described as a simple log-linear relationship with variability in slope and intercept amongst major clades, taxonomic or otherwise3,4,7. The entrenched assumption of log-linearity underpins all contemporary empirical research and theoretical models seeking to understand brain size evolution as well as that of many other traits. However, there are indications that some biological traits scale with body size on a log-curvilinear scale such as metabolic rate8,9,10,11, ingestion rate12, and offspring size and number13. Recent evidence has found that log-curvilinearity also characterizes the relationship between brain and body size amongst mammals and birds5, with profound implications for studying relative brain size. A macro-evolutionary size-dependency in the brain and body size relationship is a significant finding that resolves several long-standing puzzles surrounding brain size evolution in mammals, including the taxon-level effect, apparent brain to body size lag effects, and apparent differences in scaling parameters7,14,15,16. These artefacts of fitting linear models are size-dependent phenomena: complex statistical models and elaborate biological explanations are obviated by fitting a simple quadratic relationship. Two outstanding questions arise, however: how widespread is this pattern across taxonomic groups and what is its underlying cause?

Here, we demonstrate an unprecedented and striking size-dependency that holds across the animal tree of life. Using phylogenetic comparative approaches and a comprehensive brain size dataset spanning 4679 species across nine major animal classes, we find a single curvilinear relationship between brain and body size. Through hierarchical modelling incorporating individual-level variation, we then demonstrate that this curvature emerges as a metaphenomenon driven by diminishing allometry within individual species as body size increases. This previously overlooked size dependency reveals a mechanistic bridge between within-species dynamics and large-scale macroevolutionary patterns.

Results and discussion

A near universal size-dependency in the brain-body mass relationship

Using a dataset spanning nine major groups of animals (mammals, birds, testudines, squamates, crocodilians, amphibians, bony fish, cartilaginous fish, and insects) and nearly 12 orders of magnitude in brain and body size (Fig. 1a), we seek to determine whether curvilinearity in the brain and body mass (BBM) relationship is ubiquitous or even universal across the tree of life. To do this, we use a phylogenetic comparative approach, the variable rates regression model17,18, to study the BBM relationship across a comprehensive time-scaled phylogenetic tree encompassing all species in the sample (n = 4679). This model allows us to simultaneously estimate the slope (and/or curvature) of the BBM relationship alongside rate heterogeneity – using a Bayesian reversible jump MCMC procedure to automatically identify lineages of the phylogenetic tree in which relative brain size has evolved more rapidly or more slowly relative to body size.

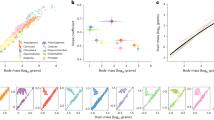

a The eight major animal classes (those listed above, excluding crocodilians owing to their small sample size) are shown in the central phylogeny with clades collapsed to triangles sized proportionally to the number of species. Each clade is expanded to show finer phylogenetic structure, with bars at the tips proportional to body size (pale) and brain size (dark). b The predicted relationships estimated in our global curve model across all 4679 species with the median prediction superimposed upon a random sample (n = 100) of the posterior. The median prediction from our global slope model is shown for comparison with a dashed line. c The posterior distribution of estimated curvature (quadratic parameters) for each of the eight non-crocodilian classes (n = 4676) compared to the global (grand mean) curvature outlined with a black dashed line. All groups substantially overlap the grand mean and are thus not significantly different from a global curve estimated across all species. Silhouettes are not proportional to size and are shown for illustrative purposes only. The major animal clades are indicated by the coloured silhouettes; the colour scheme is used throughout the manuscript to facilitate quick comparisons between results.

We first estimated a global curve model across all species. Across all of the major animal groups listed above (henceforth referred to as classes for simplicity), there is an overall curvature in the BBM comparable to that found in mammals5, with a significantly negative quadratic parameter (median = −0.014, px = 0.000) and a positive slope (median = 0.614, px = 0.000). The global curve model is significantly supported (in terms of Bayes Factors19, BF, see methods) over both a global slope model estimating only a single slope and intercept across all taxa (BF = 70.52) as well as a class slope model estimating a separate intercept and slope for each class, considering non-avian reptiles as a single group (BF = 69.28). The global curve relationship is depicted in Fig. 1b. We then further test the possibility that mammals drive the observed relationship and ascertain whether any class displays fundamental differences in the BBM relationship – as recently suggested for bony fish owing to their indeterminate growth20,21. To do this, we ran an additional model estimating a separate quadratic curve for each class (class curve model, N = 4679, see methods). In this model, we find that no class shows any significant departure from the grand mean, i.e. a global curvature estimated across all species (using deviation contrast coding, all px > 0.05). In terms of Bayes Factors, there is no improvement to be gained from estimating separate curves for each class (BF = 0.112). Repeating this analysis on a dataset removing crocodilians (N = 3) and treating squamates and testudines as separate classes reaches identical conclusions – with no individual class demonstrating curvature that differs from the global curvature (N = 4676; see Fig. 1c). From these results, we can infer a surprisingly invariant general scaling rule across diverse animal classes.

To further investigate the scale of this phenomenon, we ran an additional subclade curve model in which we estimated a separate quadratic effect for each of fifty-one monophyletic taxonomically derived subclades with N > = 20 (mostly represented by orders and families, see Materials & Methods). These models are restricted to taxa to which we could reliably assign to subclades (N = 4457); there is still significant global curvature in this subset of data. As with our class curve model, there is extraordinarily little departure from global curvature in any subclade. We find significant deviation in only 5 subclades which each only represent a small portion of the range of brain and body size data being studied (Fig. 2A-B). Despite a potentially steeper curve (i.e., a more negative quadratic parameter), three of these groups – Urodela (salamanders), Falconiformes (falcons), and Labriformes (parrotfish/wrasses) – show qualitatively the same pattern of negative curvature as the global BBM relationship, even after considering potential outliers and differences amongst monophyletic groupings within each subclade (Figs. S1–S6).

a The posterior distribution of the estimated global quadratic parameter – dashed black line –observed across n = 51 subclades. The posterior distribution of quadratic parameters for each subclade are shown in the colour of the class they belong to and are outlined where they diverge from the grand mean (and indicated by corresponding silhouettes). Atlantogenata (consisting of both Afrotheria and Xenarthra together) substantially differs from the grand mean (purple outline, no fill) – but neither of the subgroups differ after removing sirenians and elephants (grey-outlined purple distributions). b The expected change in relative brain size \(\left(\frac{\Delta {\log }_{10}{brain}}{\Delta {\log }_{10}{body}}\right)\), calculated over the full range of observed body sizes for each subclade (separating Atlantogenata into Xenartha and Afrotheria excluding elephants and sirenians) for a random 100 samples of the posterior distribution, with a median estimate overlaid. Lines are solid for the four subgroups which show significant deviations after considering potential outliers and sub-groupings. c A negative relationship between linear slope parameters (from a subclade slope model) and body size for animal subclades, obtained using PGLS regression, is significant (two-tailed test). Percentiles of the posterior distribution of slope parameters and body mass ranges are shown as transparent lines for each group. The animal classes are indicated by the coloured silhouettes; the colour scheme is used throughout the manuscript to facilitate quick comparisons between results.

The other two groups, Atlantogenata (African mammals, sloths, and armadillos) and Charadriiformes (shorebirds) show positive curvature. However, within Atlantogenata, when elephants and sirenians – members of relatively disparate orders separated by millions of years of evolution22,23 – are removed from the analysis, there is no longer any deviation from the grand mean (see Supplementary Note 1, Figs. S4 and S6). Amongst Charadriiformes, the positive curvature seems to largely be driven by the sub-clade Charadrii (N = 35, Supplementary Note 1, Figs S5 and S6), a group mostly represented by plovers. This clade has been noted to have unusually high sexual dimorphism24 and sexual selection has been suggested to influence brain size amongst Charadriiformes as a whole25. Whether this is the cause of why plovers seem to deviate from the expectations derived from all other animal species is an intriguing question that warrants further investigation – along with why elephants and sirenians appear to be outliers, and why some groups seem to have steeper curves.

However, even considering these few deviations (Figs. S1–S6), our results reveal a remarkable ubiquity of curvature in the BBM relationship across all animal life. The same curvature is identified to fit over most animals included in our study – and is therefore not simply a product of fitting a quadratic term over a dataset spanning nearly twelve orders of magnitude. Whilst the parameter of curvature itself may seem only small (median quadratic coefficient = −0.014), not only is it significant (Supplementary Note 2), but it can also result in important implications for our interpretation of brain size scaling. For example, if we were to ignore the observed curvature in the BBM, a sperm whale (Physeter catodon) is predicted to have a brain size of ~12 kg – much too large compared to observed values (~7.8 kg). However, curvilinearity substantially improves this prediction – reducing it more than 43% to a value of ~7 kg and far closer to reality. These results thus have crucial implications for understanding the brain size relative to body size of individual species. In order to visualize how this curvature can be interpreted across different taxa, we calculated the expected change in brain and body size (\(\frac{\Delta {\log }_{10}{brain}}{\Delta {\log }_{10}{body}}\)) over the full sample of estimated parameters for each of the subgroups in our analysis (Fig. 2B). If there was no curvature, the expected change in brain and body size would be equivalent for animals of all sizes – yet we see that on a log-scale that large-bodied animals of most subgroups have proportionally less change in brain mass per unit body mass.

In all analyses reported here, we find substantial support for variable rates (see methods, Fig. S7 and Supplementary Note 3). However, the curvilinearity that we identify is supported in the absence of rate heterogeneity. Overall, our results remain qualitatively unchanged when we use a model that assumes a constant rate of evolution. Confirming this, we find further support for a consistent curvature in the BBM relationship in the form of a significant negative association between the slope of the BBM relationship from the subclade slope model and the average body size across all fifty-one subclades (Fig. 2C; α = 0.590, β = −0.031, all p-values < 0.001). This relationship still persists to the exclusion of the small-bodied insects (α = 0.591, β = −0.034, all p-values < 0.001) as well as sharks and testudines (the two other groups with relatively small sample size, Fig S8; α = 0.590, β = −0.034, all p-values < 0.001); see Supplementary Note 4 for more details. It is also upheld in the absence of rate heterogeneity (Supplementary Note 5). Together, this universal body size dependency underpins the fascinating prospect that heterogeneity in slopes previously attributed to diverse selection pressures or scaling rules can be explained simply as a size-dependent effect5. This obviates the need for special explanations for distinct patterns in diverse taxa and has major implications for understanding brain evolution. For example, this moves us beyond the concept of testing for lineage-specific scaling patterns and suggests that some previously identified correlates of relative brain size might be size-dependent artefacts. Across all animals – from bees to blue whales - there is a size-dependency in the BBM (Fig. 2B) that requires an explanation.

Curvature as a macroevolutionary metaphenomenon

Comparative phylogenetic approaches to studying evolutionary relationships – including those we carry out here – seek to identify a so-called “evolutionary regression coefficient”26 that describes the covariation of two or more traits along the branches of a phylogenetic tree (i.e., an evolutionary slope parameter). The interpretation of such parameters is implicitly linked to underlying within-species variation26,27 – whether this arises through measurement error or observational variability including population differences26,27,28. That is, the patterns we are observing at the macro-evolutionary scale are essentially averages of those acting across individual lineages26 and thus on the variability upon which natural selection acts. This view is reflected in earlier studies of metabolic rates which linked macro-evolutionary metabolic scaling to variation in the intercepts amongst species29. However, in the context of the BBM relationship, a curvilinear model implies that the evolutionary regression coefficient (slope) along individual branches is itself linked to body size in a biased fashion. In such a scenario, variation in species-level brain allometries would be linked to body size. That is, we would predict not just simple variability in intercepts, but an explicit bias wherein within-species slopes will be lower at larger body mass (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 6).

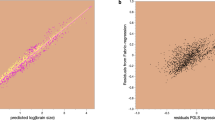

A curved relationship between brain and body size across species can arise from differential allometries observed within individual taxa. If species-level allometries vary with size (inset), this results in a general tendency for the slope in the BBM relationship to become shallower with increasing size (orange lines). When we study the data across species, this gives rise to a macroevolutionary metaphenomenon of curvature (purple dashed line).

Here, we investigated the possibility that heterogeneity in the microevolutionary allometry observed within individual species4 shows a directional association with body size in such a way that it gives rise to a macroevolutionary metaphenomenon of curvature (Fig. 3). To do this, we used brain and body size data from Tsuboi et al.4, spanning a total of 376 vertebrate species with at least 10 individual measurements– note that this dataset does not include any insects or cartilaginous fish. Consistent with our hypothesis, using phylogenetic generalized least squares models30, we identify a strongly significant negative relationship between the within-species slopes of the BBM relationship and the average body size of each species (Fig. 4a, α = 0.37 [p < 0.001]; β = −0.04 [p = 0.008]; λ = 0.13). This is not owing to a reduction in the strength of association in larger species: there is no association of body size with the significance, mean-squared error, or R2 value (Supplementary Note 7) – that is, there is truly a body size dependency in these within-species allometries.

The patterns depicted in Fig. 3 are reflected in real data from 376 vertebrates. a There is a significant negative relationship between slope parameter and average species-level body size. b There is significant curvature in the relationship across species – shown as the predictions from a global curve model (N = 376) accounting for within-species variability in both brain and body size as a random effect in a PGLMM. The median prediction is overlaid on top of a random sample of 100 lines from the posterior. The major animal clades are indicated by the coloured silhouettes; the colour scheme is used throughout the manuscript to facilitate quick comparisons between results.

Whilst it is recognized that within-species allometries tend to be shallower than those observed across higher taxa4, we note that many of the slopes within individual species are close to zero – with some of these even being negative. It is difficult – though not impossible31 – to envisage a scenario in which an increase in body size would lead to a reduction in brain size and so the relationships within these species may warrant further investigation. However, our results stand even when we study only those species with positive slopes (N = 313, α = 0.43 [p < 0.001]; β = −0.05 [p < 0.001]; λ = 0.12, R2 = 0.04).

In order to distinguish the nature of individual-level variability from macroevolutionary patterns and thus formalise the notion presented in Fig. 3, we can use a statistical technique known as within-group centring32. This approach accounts not only for variation in trait values, but also the heterogeneity observed amongst individual species-level allometries. However, before being able to implement these approaches, we first ensured that the curvature was still apparent in the subset of data for which we have individual-level variation (N = 376). Using phylogenetic generalized linear mixed models33 (PGLMMs) to account for individual-level variation in both brain and body size, we recover a significant negative quadratic parameter across species (median = −0.039, px = 0.000) as well as a significant positive slope (median = 0.55, px = 0.000) (Fig. 4b). That is, we can explicitly demonstrate the expectations laid out in Fig. 3 using empirical data.

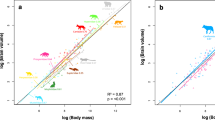

We therefore proceeded to run a PGLMM model using within-group centring32 – referred to as our hierarchical model. Our hierarchical model estimates two main components: (i) a BBM relationship across species including curvature (using species-level means); and (ii) an average effect of within-species allometric variability (using species-level slopes as a random effect). In this hierarchical model, we no longer find any curvature across species (mean β = 0.004, px = 0.475), indicating that intraspecific patterns of brain size variation are the driving force behind the macroevolutionary curvature (Figs. 3–4). The relationship acting within individual species is generally much shallower (mean β = 0.41, px = 0.000) than that observed across species (mean β = 0.59, px = 0.000) as depicted in Fig. 5 a,b. Whilst this is in line with early observations of intraspecific vs. interspecific brain allometry amongst mammals34, it is important to note that this within-species slope is derived from the true variability in slope observed within individual species (Fig. 5a, inset). An alternative way of parameterizing this model – with identical interpretation – would be to estimate curvature in the within-species component of the model rather than allowing intra-specific variability (i.e. not including species-level slopes as a random effect). This model, shown in Fig. 6, still removes the across-species curvature while the significant within-species negative quadratic effect (mean β = -0.02, px = 0.000) again emphasizes the general tendency for a reduction in slope values for individual species with increasing size – as shown in Fig. 3. Previous suggestions that there may be a low correlation between brain and body size within individual species e.g.35,36,37 may be associated with the fact that the most well-studied taxa tend to be larger. In any case, the factors driving such body size dependency as well as additional variability in the within-species BBM relationship remains to be fully elucidated.

a The predicted relationship between brain and body size from the hierarchical model separated into within-species effects (orange) and across-species effects (purple). The average within-species slope is derived from the species-level variability in slope depicted in (b, inset). In (b, c), we plot the posterior distributions of estimated parameter estimates from our hierarchical model. We also include the posterior distribution of parameter estimates from the across species global curve model (from Fig. 4b) for comparison (grey).

a The predicted relationship between brain and body size from an alternative hierarchical model separated into within-species effects (orange) and across-species effects (purple). In this model, we do not incorporate a random effect for species-level slopes (as we did for our main hierarchical model depicted in Fig. 5). The overall curvature in the average within-species slopes is owing to the pattern of diminishing slope value with increasing body size. In (b, c), we plot the posterior distributions of estimated parameter estimates from our alternative hierarchical model. We also include the posterior distribution of parameter estimates from the across species global curve model (from Fig. 4b) for comparison (grey). In this alternative hierarchical model, there is no significant curvature across species.

Widespread curvilinearity in metabolic scaling e.g.8, has previously been linked to differences amongst scaling-exponents at lower taxonomic levels10,38,39. Along with previous evidence from mammals and birds5, our results demonstrate similarly widespread curvilinear scaling for brain size – but go one step further by explicitly examining the effects of both within-species and across-species relationships with body size. In doing so, we reveal that it is only by understanding the relationship within individual species that we can actually begin to explain the observed curvature across species. The factors driving variation within species, including genetic factors, fundamentally differ from processes shaping evolutionary diversity which often involve associations with other traits or environmental factors40,41,42. In line with this, several factors commonly reported to be important brain size correlates at the species level have no apparent effect on the size-dependency caused by variability amongst individuals. Variation in neither metabolic rates43,44 nor neuron number45,46 affect the curvature across mammals5, and neither environmental temperature47 nor diet48 have any effect on size-dependency amongst endothermic vertebrates (see Supplementary Note 8). Instead, our results imply a mechanistic explanation in which the global curvature in the animal BBM relationship is a manifestation of the change in brain and body size within individual species along a body size gradient. Simply put, within-species variation explains the size dependency in the BBM relationship.

Concluding remarks

Our results provide unprecedented insight into what exactly it is we are studying when we use phylogenetic regression. By studying traits such as relative brain size at multiple scales – from individuals to species – we can reveal profoundly different patterns and provide crucial insights into how we measure relative brain size – and how macroevolutionary patterns can arise from within-species variation. For example, Puschel et al.35 recently revealed that hominin encephalization resulted from increases in brain size within individual species and an accelerating pattern of increase through time. Whilst an increase in the rate of brain expansion during hominin evolution has been repeatedly demonstrated49,50,51, it is only by the separation of within- and between- species evolutionary dynamics that we can truly begin to understand how these patterns have arisen. It may not always be enough to simply study species-level averages whilst accounting for variation in trait values, i.e. Figure 6a, refs. 52,53,54. Instead, we need to understand how differences in the BBM arise through evolutionary processes acting at different hierarchical levels4,32. That is, there is a necessity to understand how microevolutionary variation can give rise to macroevolutionary patterns.

The universal curvilinearity in the brain and body size relationship observed across species is a metaphenomenon driven by microevolutionary within-species processes. This raises questions about studying brain size evolution in relation to behavioural-ecological factors – wherein incorporating body size dependency or within-species dynamics may affect our conclusions about the drivers of brain evolution. Furthermore, this size dependent phenomenon is unlikely to be unique to brain size.

It is already well-established that non-linearity and curvature exists in the relationship between metabolic rate and body size across a wide range of organisms8,9,10,11,12 and authors have noted a potential size-dependent effect11 similar to that observed here for animal slopes. Curvature in fundamental biological traits has profound implications for the interpretation of many biological phenomena such as biological scaling55,56,57. For instance – and given the importance of metabolism in almost all biological variation and processes58,59 – it follows that we should perceive curvature in other biological traits12. Indeed, along with brain size, non-linearity has been demonstrated in a suite of other traits including, ingestion rate12, locomotion costs12, maternal energy intake60, and offspring size and number13. Our results for brain size indicate that we need to look to variation within individual species in order to be able to explain these patterns. This is in line with observations made for metabolic rates in which curvilinearity can be attributed – at least to some degree – to ontogenetic variation within individual species as well as to interspecific relationships55,56.

To the extent that such patterns are true, our approach reveals a way to more clearly understand the underlying causes of enduring and controversial macroevolutionary phenomena such as Cope’s rule61 and Bergmann’s rule62 - using a simple separation of microevolutionary and macroevolutionary processes. A deeper understanding of what exactly we are studying when we use phylogenetic regression provides a broader framework for understanding how microevolutionary within-species dynamics can shape macroevolutionary phenomena.

Methods

Species-Level Data

The brain and body sizes of animal species were collated from the literature. The full dataset and all references are provided as Supplementary Data 1. We chose to use only whole-brain mass and excluded species where brain masses were reported excluding the olfactory bulb e.g.63,64. Where measurements were explicitly noted to come from juvenile specimens e.g.4, we did not include these measurements. We preferred sources which provided paired brain and body size estimates, and those which reported brain size as masses rather than volumes. Where only endocranial volumes were available, we converted these to masses in line with a 1 g = 1 cm3 conversion, ensuring consistency with conversions used in several major sources3,65,66. However, the pattern is upheld even in groups where data is primarily derived directly from masses (e.g. Chiroptera, Amphibians, cartilaginous fish). Where duplicate entries occurred for species given these criteria, we preferred the earliest source after removing extreme outliers by eye. In all cases, we record the source from which we obtained the data used in our analysis in Supplementary Data 1.

In some cases, we modified values or used values from an alternative source. We excluded the brain mass for the blue whale Balaenoptera musculus in several sources owing to a misrepresentation derived from a dehydrated sample67. Rodentia and Lagomorpha brain sizes from several sources2,4,68 were adjusted as outlined by66,69 in order to correct a systematic bias in the original source from which they were obtained70. For fish and sharks obtained from the BRAINS table in Fishbase71, we used the average reported brain and body size per species (although analyses using the maximum made no difference).

Our final dataset contained brain and body size data for a total of 4679 species that were also found in the animal-wide phylogenetic tree (see below). The full dataset is provided as Supplementary Data 1. All data were logged (log10) before analysis.

Phylogenetic Tree

For all our phylogenetic analyses, we use the time tree of life72,73,74. We downloaded a phylogenetic tree for Chordata from the time tree of life website in February 202475. Species names were matched to the time tree; only species found in the tree were retained for analysis. We ensured the tree was ultrametric (all tips terminated at the present) and collapsed all polytomies to multifurcations (also referred to as hard polytomies). Finally, owing to numerical issues associated with estimating evolutionary parameters along trees with very short terminal branches, we removed randomly all but one member of any species group descending from a single node with a branch length of less than 0.25 (250 Ky). To do this, we used a custom R function, which we provide as Supplementary Code 1.

Class-level and subclade assignments

We separated species into major phylogenetic and taxonomic clades: amphibians, mammals, bony fish, cartilaginous fish, reptiles, and birds. As reptiles comprise several major taxonomic groups: birds (N = 1327), squamates (N = 251), testudines (N = 25), and crocodilians (N = 3), we divided these taxa into two major monophyletic clades: birds and non-avian reptiles. Our analyses are conducted both considering non-avian reptiles and birds separately (in which the phylogenetic structure amongst the different reptilian groups are incorporated) and additionally studying testudines and squamates as separate groups. In the latter, crocodilians are removed owing to their small independent sample size. All major animal clades are referred to as classes for simplicity and consistency.

We then assigned species to a lower-level taxonomic designation (henceforth subclade) based on major taxonomic resources76,77,78,79,80,81 and original references (see Supplementary Data 1). For the most part, these subclades are represented by taxonomic orders. In some cases, subclades were paraphyletic or too small for further study and so to maximize species inclusion, we combined subclades to form larger monophyletic groups. For example, ten different groups of fish (a mix of order and family level) as defined by the NCBI taxonomy database77 form a single monophyletic clade (Ovalentaria) in the time tree of life and so were here included as a single group. We studied marsupials as a single group as it included several small orders which would be otherwise excluded and similarly studied Afrotheria and Xenarthra within mammals as a single magnorder, Atlantogenata (though see results and Supplementary Note 1 for more information about the division of this group). The major bird clade Aequorlitornithes as described by Prum et al.81 comprises two large monophyletic groups which we here study as two separate subclades: the shorebird order Charadriiformes (N = 140), and another clade containing various other waterbird orders such as loons, penguins, herons, and seabirds (N = 66). We retained only subclades large enough for further study (N ≥ 20) – with one exception. We include bees (N = 14) in order to enable comparison between insect subclades (bees and ants). N = 220 species belonging to all other smaller groups were removed from our subclade-level analyses for a total of N = 4457 species across 51 subclades.

Within-Species Data

The brain and body sizes for individual vertebrates were obtained from Tsuboi et al.4,82. Using code associated with and described in the original paper4,82, we centred data according to sex (male, female, or unreported) and measurement method (volume or mass). We then linked the names in this dataset to the names in the time tree of life and removed species where N < 10, resulting in a dataset of 376 species. Results using uncentred data produced the same major conclusions (Supplementary Note 9).

Analysis

The brain and body size relationship across species

We performed a series of phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS) analyses to model the relationship between brain and body size across animal species. Here, we estimate curvature using a quadratic parameter – which is likely to be a good approximation of the curvilinearity observed over the range of observed body masses5. Note also that this would essentially be identical in interpretation to a linear threshold model that estimates different slopes for different size classes – with infinite thresholds. Our global curve model estimated a single intercept, slope, and quadratic parameter across all N = 4679 species. Our class curve models estimated a separate intercept, slope, and quadratic parameter for each of the major animal classes and were conducted both across all N = 4679 species (considering all non-avian reptiles as a single group) and across N = 4676 species (considering each reptile clade separately, to the exclusion of crocodilians). Our subclade curve models estimated a separate intercept, slope, and quadratic parameter for each of 51 subclades and is performed on only a subset of N = 4457 species (see above). Repeating the class curve model and global curve model on the limited dataset resulted in only negligible differences and so we report the full results here.

All analyses were performed using a Bayesian reversible jump MCMC procedure implemented in BayesTraits83. Chains were run for a total of 10 billion iterations, removing the first 100 million as burn-in and retaining every 500 thousand samples. We used a wide and uninformative normal prior centred on zero with a standard deviation of 2.5 for all regression parameters. Convergence was assessed visually, and multiple replicates were run to ensure repeatability of results and that our posterior distributions differed from the prior. Our results did not differ across replicates. We assessed parameter significance using the proportion of the posterior distribution overlapping zero (px). Where the posterior distribution of a parameter value had px < 0.05, it means that less than 5% of the distribution crosses zero and could therefore be considered substantially different from zero. We compared differences amongst classes and subclades using sum contrast (or deviation) coding – a coding system for categorical variables in regression analyses that allows for the comparison of a group-level parameter (e.g. class-level curvature) to an overall mean across all species (grand mean curvature). This method returns parameter estimates interpretable as the difference between each group and the grand mean. Therefore, where the posterior distribution of difference parameters significantly overlaps zero (px > 0.05), there is no substantial difference between that group and the grand mean.

We implement our PGLS models using the variable rates regression model, which simultaneously estimates the regression parameters alongside heterogeneity in the rate of evolutionary change17,18. This method automatically identifies lineages (branches) of the phylogenetic tree in which relative brain size has evolved at a faster or slower rate relative to body size17,18. It does this by estimating a set of rate scalars r defining the rate of evolution on each branch of the phylogenetic tree: where r > 1, a branch is evolving faster than the background rate of change, and where 0 ≤ r < 1, it is evolving slower.

We assessed whether rate heterogeneity was supported in each of our models by calculating Bayes Factors with the equation BF = -2loge(m1/m0), where m0 is the marginal likelihood of a model with only a single underlying rate of evolutionary change and m1 is the marginal likelihood of a variable rates model that estimates rate heterogeneity. Where BF > 2, it is considered to be positive support for rate heterogeneity19. All marginal likelihoods were estimated using stepping-stone sampling84, sampling 100,000 iterations for each of 1000 stones after convergence was reached. All PGLS analyses reported in the main text show substantial support for variable rates – all having Bayes Factors > 500. A summary of the estimated rate for each branch of the phylogenetic tree is provided in Supplementary Data 2. However, it is not possible to estimate rate heterogeneity in all downstream analyses (e.g. mixed models, see below). Therefore, we also replicated all our PGLS analyses using models that assumed a constant rate of evolution (i.e. no rate heterogeneity). Our conclusions remain qualitatively unchanged (see Supplementary Note 5 and Figs. S9-S14) and we therefore only present the results from the variable rates models in the main text.

Size-dependency in the brain-body relationship across species

To determine the size dependency effect on brain and body size slopes, we ran two additional PGLS models in the same way described above. These models estimated a separate intercept and slope for each class (class slope model) or each subclade (subclade slope model) respectively. We then estimated a relationship between the median slope value and median body size for each group (class or subclade) using maximum likelihood PGLS models implemented in caper30, estimating phylogenetic signal using Lambda85.

Analyses incorporating within-species variation

To investigate the possibility that heterogeneity in the brain and body size relationship observed amongst individual species could give rise to the observed curvature across species, we conducted a series of analyses using phylogenetic generalized linear mixed models (PGLMMs) implemented in MCMCglmm33. In these models, we incorporate phylogenetic information as a random effect using the phylogenetic variance-covariance matrix. Species-level variation is incorporated by the inclusion of all values for species with at least 10 individual measurements and an additional random effect allocating each point to a given species.

Prior to our PGLMMs, we first ran a reduced global curve model, replicating our global curve model using only the sample of species for which we had within-species data, and the brain and body size measurements as reported in Supplementary Data 1, ensuring that we still recovered significant curvature in this reduced dataset. This reduced sample of taxa still displays significant negative curvature (mean β = -0.04, px = 0.02). We then ran a global curve with species-level variation PGLMM on the same reduced sample of species but this time including all individual measurements. This model included both body size and a second order quadratic term as fixed effects along with the phylogeny and species association as random effects. Phylogenetic signal was assessed using heritability. For all continuous fixed effects, we used a normally distributed diffuse prior as in the default options33. For random effects we used non-informative parameter-expanded priors (V = 1, nu = 1, alpha.mu = 0, alpha.V = 1000).

We then used within-group centering32 to separate body size into two components: across-species body size (a species-level average of body size) and within-species body size (calculated as the difference between each species and the species-level mean). In doing so, it becomes possible to estimate both the brain and body size relationship (including curvature) across all species alongside an average effect of within-species allometric variability – within a single statistical model. We refer to this as our hierarchical model, which includes three fixed effects (across-species body size and its second order quadratic term as well as within-species body size) and three random effects (the phylogenetic variance-covariance matrix, a species identifier, and within-species slopes). Including species-level slopes as a random effect allows us to incorporate the variability in slope observed across individual species4.

It is not currently possible to estimate rate heterogeneity in a PGLMM (see above); all PGLMM analyses were therefore performed on the time tree of life limited to the species included within the analysis, where branch lengths were proportional to time. However, our conclusions remained qualitatively identical when we use a tree where branch lengths have been scaled to reflect the median rate of evolution given the global curve model (i.e. branch lengths = r x t).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data analysed in this study are available in the main text or the supplementary materials, along with the original sources from which they were obtained (Supplementary Data 1). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

We provide code developed as a part of this work in the supplementary material (Supplementary Code 1), but all other analyses were performed using publicly available, published and peer-reviewed programs which are cited appropriately in the text.

References

Aiello, L. C. & Wheeler, P. The expensive-tissue hypothesis: the brain and the digestive system in human and primate evolution. Curr. Anthropol. 36, 199–221 (1995).

Boddy, A. et al. Comparative analysis of encephalization in mammals reveals relaxed constraints on anthropoid primate and cetacean brain scaling. J. Evolut. Biol. 25, 981–994 (2012).

Burger, J. R., George, M. A. Jr., Leadbetter, C. & Shaikh, F. The allometry of brain size in mammals. J. Mammal. 100, 276–283 (2019).

Tsuboi, M. et al. Breakdown of brain–body allometry and the encephalization of birds and mammals. Nat. Ecol. Evolution 2, 1492–1500 (2018).

Venditti, C., Baker, J. & Barton, R. A. Co-evolutionary dynamics of mammalian brain and body size. Nat. Ecol. Evolution 8, 1534–1542 (2024).

Jerison, H. J. The theory of encephalization. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 299, 146–160 (1977).

Smaers, J. B. et al. The evolution of mammalian brain size. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe2101 (2021).

Kolokotrones, T., Savage, V., Deeds, E. J. & Fontana, W. Curvature in metabolic scaling. Nature 464, 753–756 (2010).

Zeuthen, E. Oxygen uptake as related to body size in organisms. Q. Rev. Biol. 28, 1–12 (1953).

Hayssen, V. & Lacy, R. C. Basal metabolic rates in mammals: taxonomic differences in the allometry of BMR and body mass. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Physiol. 81, 741–754 (1985).

Mori, S. et al. Mixed-power scaling of whole-plant respiration from seedlings to giant trees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1447–1451 (2010).

Bueno, J. & López-Urrutia, Á Scaling up the curvature of mammalian metabolism. Front. Ecol. Evolution 2, 61 (2014).

Glazier, D. S. Age-specific mortality predicts body-mass scaling of offspring mass and number. Evolut. Ecol. 38, 513–535 (2024).

Ksepka, D. T. et al. Tempo and pattern of avian brain size evolution. Curr. Biol. 30, 2026–2036.e2023 (2020).

Bertrand, O. C. et al. Brawn before brains in placental mammals after the end-Cretaceous extinction. Science 376, 80–85 (2022).

Dembitzer, J., Castiglione, S., Raia, P. & Meiri, S. Small brains predisposed Late Quaternary mammals to extinction. Sci. Rep. 12, 3453 (2022).

Baker, J., Meade, A., Pagel, M. & Venditti, C. Positive phenotypic selection inferred from phylogenies. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 118, 95–115 (2016).

Venditti, C., Meade, A. & Pagel, M. Multiple routes to mammalian diversity. Nature 479, 393–396 (2011).

Raftery, A. E. In: Markov Chain Monte Carlo in practice (eds Gilks, W. R. Richardson, S. & Spiegelhalter, D. J.) 10, 163–187 (Chapman & Hall, 1996).

Triki, Z. Scaling up the mammalian brain. Nat. Ecol. evolution 8, 1389–1390 (2024).

Triki, Z., van Schaik, C. & Bshary, R. The Fish Challenge to Vertebrate Cognitive Evolution, (2024).

Heritage, S, Seiffert, E & Borths, M Recommended fossil calibrators for time-scaled molecular phylogenies of Afrotheria. Afrotherian Conservation 17 https://www.afrotheria.net/newsletter.php (2021).

Liu, G. et al. Phylogenomics of Afrotherian mammals and improved resolution of extant Paenungulata. Mol. Phylogenetics Evolution 195, 108047 (2024).

Székely, T., Reynolds, J. D. & Figuerola, J. Sexual size dimorphism in shorebirds, gulls, and alcids: the influence of sexual and natural selection. Evolution 54, 1404–1413 (2000).

García-Peña, G. E., Sol, D., Iwaniuk, A. N. & Székely, T. Sexual selection on brain size in shorebirds (Charadriiformes). J. Evolut. Biol. 26, 878–888 (2013).

Pagel, M. Seeking the evolutionary regression coefficient: an analysis of what comparative methods measure. J. Theor. Biol. 164, 191–205 (1993).

Adams, D. C. & Collyer, M. L. Extending phylogenetic regression models for comparing within-species patterns across the tree of life. Methods Ecol. Evol. n/a https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14438.

Hansen, T. F. & Bartoszek, K. Interpreting the evolutionary regression: the interplay between observational and biological errors in phylogenetic comparative studies. Syst. Biol. 61, 413–425 (2012).

Heusner, A. A. Size and power in mammals. J. Exp. Biol. 160, 25–54 (1991).

R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, (2024).

Mann, M. D., Frank, L. G., Glickman, S. E. & Towe, A. L. Brain and Body Size Relations among Spotted Hyenas (Crocuta crocuta). Brain Behav. Evol. 92, 82–95 (2018).

van de Pol, M. & Wright, J. A simple method for distinguishing within-versus between-subject effects using mixed models. Anim. Behav. 77, 753–758 (2009).

Hadfield, J. D. MCMC methods for multi-response generalized linear mixed models: the MCMCglmm R package. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22 (2010).

Lande, R Quantitative genetic analysis of multivariate evolution, applied to brain: body size allometry. Evolution, 402–416 (1979).

Püschel, T. A., Nicholson, S. L., Baker, J., Barton, R. A. & Venditti, C. Hominin brain size increase has emerged from within-species encephalization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2409542121 (2024).

Holloway, R. L. Within-species brain-body weight variability: A reexamination of the Danish data and other primate species. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 53, 109–121 (1980).

Sholl, D. The quantitative investigation of the vertebrate brain and the applicability of allometric formulae to its study. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B-Biol. Sci. 135, 243–258 (1948).

Clarke, A., Rothery, P. & Isaac, N. J. B. Scaling of basal metabolic rate with body mass and temperature in mammals. J. Anim. Ecol. 79, 610–619 (2010).

Ehnes, R. B., Rall, B. C. & Brose, U. Phylogenetic grouping, curvature and metabolic scaling in terrestrial invertebrates. Ecol. Lett. 14, 993–1000 (2011).

Hulshof, C. M. et al. Intra-specific and inter-specific variation in specific leaf area reveal the importance of abiotic and biotic drivers of species diversity across elevation and latitude. J. Vegetation Sci. 24, 921–931 (2013).

Fine, P. V. Ecological and evolutionary drivers of geographic variation in species diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol., Evolution, Syst. 46, 369–392 (2015).

Weller, A. K., Chapman, O. S., Gora, S. L., Guralnick, R. P. & McLean, B. S. New insight into drivers of mammalian litter size from individual-level traits. Ecography 2024, e06928 (2024).

McNab, B. K. & Eisenberg, J. F. Brain Size and Its Relation to the Rate of Metabolism in Mammals. Am. Nat. 133, 157–167 (1989).

Isler, K. & Van Schaik, C. P. Metabolic costs of brain size evolution. Biol. Lett. 2, 557–560 (2006).

Kverková, K. et al. The evolution of brain neuron numbers in amniotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2121624119 (2022).

Beaulieu-Laroche, L. et al. Allometric rules for mammalian cortical layer 5 neuron biophysics. Nature 600, 274–278 (2021).

Gillooly, J. F. & McCoy, M. W. Brain size varies with temperature in vertebrates. PeerJ 2, e301 (2014).

DeCasien, A. R., Williams, S. A. & Higham, J. P. Primate brain size is predicted by diet but not sociality. Nat. Ecol. evolution 1, 0112 (2017).

Pagel, M. In Morphology, shape and phylogeny (eds MacLeod, L. & Forey, P.) 269–286 (CRC Press, 2002).

Diniz-Filho, J. A. F., Jardim, L., Mondanaro, A. & Raia, P. Multiple Components of Phylogenetic Non-stationarity in the Evolution of Brain Size in Fossil Hominins. Evolut. Biol. 46, 47–59 (2019).

Miller, I. F., Barton, R. A. & Nunn, C. L. Quantitative uniqueness of human brain evolution revealed through phylogenetic comparative analysis. eLife 8, e41250 (2019).

Revell, L. J. & Graham Reynolds, R. A new Bayesian method for fitting evolutionary models to comparative data with intraspecific variation. Evolution 66, 2697–2707 (2012).

Teo, B., Rose, J., Bastide, P. & Ané, C. Accounting for intraspecific variation in continuous trait evolution on a reticulate phylogeny. Bull. Soc. Syst. Biologists 2, 1–29 (2023).

Venditti, C., Baker, J., Benton, M. J., Meade, A. & Humphries, S. 150 million years of sustained increase in pterosaur flight efficiency. Nature 587, 83–86 (2020).

Glazier, D. S. Multiphasic allometry: the reality and significance of ontogenetic shifts in the body-mass scaling of metabolic rate. Academia Biology 2 (2024).

Glazier, D. S. Beyond the ‘3/4-power law’: variation in the intra-and interspecific scaling of metabolic rate in animals. Biol. Rev. 80, 611–662 (2005).

Glazier, D. S. Variable metabolic scaling breaks the law: from ‘Newtonian’to ‘Darwinian’approaches. Proc. R. Soc. B 289, 20221605 (2022).

Brown, J. H., Gillooly, J. F., Allen, A. P., Savage, V. M. & West, G. B. Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology 85, 1771–1789 (2004).

Glazier, D. S. Is metabolic rate a universal ‘pacemaker’ for biological processes? Biol. Rev. 90, 377–407 (2015).

Douhard, F., Lemaître, J.-F., Rauw, W. M. & Friggens, N. C. Allometric scaling of the elevation of maternal energy intake during lactation. Front Zool. 13, 1–12 (2016).

Alroy, J. Cope’s rule and the dynamics of body mass evolution in North American fossil mammals. Science 280, 731–734 (1998).

Blackburn, T. M., Gaston, K. J. & Loder, N. Geographic gradients in body size: a clarification of Bergmann’s rule. Diversity Distrib. 5, 165–174 (1999).

Dos Santos, S. E. et al. Cellular scaling rules for the brains of marsupials: Not as “primitive” as expected. Brain, Behav. evolution 89, 48–63 (2017).

Herculano-Houzel, S., Catania, K., Manger, P. R. & Kaas, J. H. Mammalian brains are made of these: a dataset of the numbers and densities of neuronal and nonneuronal cells in the brain of glires, primates, scandentia, eulipotyphlans, afrotherians and artiodactyls, and their relationship with body mass. Brain, Behav. Evolution 86, 145–163 (2015).

Isler, K. & van Schaik, C. P. Allomaternal care, life history and brain size evolution in mammals. J. Hum. evolution 63, 52–63 (2012).

Isler, K. & van Schaik, C. P. The Expensive Brain: A framework for explaining evolutionary changes in brain size. J. Hum. Evolution 57, 392–400 (2009).

Ridgway, S. H. & Van Alstyne, K. R. The blue whale brain misrepresented by an alcohol dehydrated brain of 3,636 grams. Mar. Mammal. Sci. 33, 386–388 (2017).

Kverková, K. et al. Sociality does not drive the evolution of large brains in eusocial African mole-rats. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–14 (2018).

Isler, K. & Van Schaik, C. P. Why are there so few smart mammals (but so many smart birds)? Biol. Lett. 5, 125–129 (2009).

Mace, G. M., Harvey, P. H. & Clutton-Brock, T. Brain size and ecology in small mammals. J. Zool. 193, 333–354 (1981).

Froese, R. & Pauly, D. FishBase, http://www.fishbase.org (2012).

Hedges, S. B., Dudley, J. & Kumar, S. TimeTree: a public knowledge-base of divergence times among organisms. Bioinformatics 22, 2971–2972 (2006).

Hedges, S. B. & Kumar, S. The timetree of life. (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Hedges, S. B., Marin, J., Suleski, M., Paymer, M. & Kumar, S. Tree of life reveals clock-like speciation and diversification. Mol. Biol. evolution 32, 835–845 (2015).

Kumar, S. et al. TimeTree 5: An Expanded Resource for Species Divergence Times. Mol. Biol. Evolution 39, msac174 (2022).

IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Vol. Version 2016-1). https://www.iucnredlist.org (2016).

Federhen, S. The NCBI taxonomy database. Nucleic acids Res. 40, D136–D143 (2012).

AmphibiaWeb. AmphibiaWeb: information on amphibian biology and conservation v2.0, <http://amphibiaweb.org/> (2005).

Roskov, Y. et al. (Naturalis, Leiden, the Netherlands, 2016).

Gill, F., Donsker, D. & Rasmussen, P. IOC world bird list. Vol. 11 (IOC, 2021).

Prum, R. O. et al. A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature 526, 569–573 (2015). http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v526/n7574/abs/nature15697.html#supplementary-information.

Tsuboi, M., Shoji, J., Sogabe, A., Ahnesjö, I. & Kolm, N. Within species support for the expensive tissue hypothesis: a negative association between brain size and visceral fat storage in females of the Pacific seaweed pipefish. Ecol. evolution 6, 647–655 (2016).

Pagel, M., Meade, A. & Barker, D. Bayesian estimation of ancestral character states on phylogenies. Syst. Biol. 53, 673–684 (2004).

Xie, W., Lewis, P. O., Fan, Y., Kuo, L. & Chen, M.-H. Improving marginal likelihood estimation for Bayesian phylogenetic model selection. Syst. Biol. 60, 150–160 (2010).

Pagel, M. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature 401, 877–884 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the University of Reading Evolutionary Biology Research Group and George Butler for helpful discussions about this work. CV was funded by a Leverhulme Trust Leadership Award RL-2019-012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JB, RB, and CV conceptualized the study and developed the methodology. JB performed the investigation under the supervision of CV. JB wrote the original draft and generated the visualizations. JB, RB, and CV were responsible for reviewing and editing successive drafts of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Douglas Glazier, and the other anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baker, J., Barton, R.A. & Venditti, C. Macroevolutionary brain scaling is a microevolutionary metaphenomenon. Nat Commun 17, 136 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66843-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66843-0