Abstract

Single-shot hyperspectral wavefront sensing is essential for applications like spatio-spectral coupling metrology in high-power laser or fast material dispersion imaging. Under broadband illumination, traditional wavefront sensors assume an achromatic wavefront, which makes them unsuitable. We introduce a hyperspectral wavefront sensing scheme based on the Hartmann wavefront sensing principles, employing a multicore fiber as a Hartmann mask to overcome these limitations. Our system leverages the angular memory effect and limited spectral correlation width of the multicore fiber, encoding wavefront gradients into displacements and the spectral information into uncorrelated speckle patterns. This method retains the simplicity, compactness, and single-shot capability of conventional wavefront sensors, with only a slight increase in computational complexity. It also allows a tunable trade-off between spatial and spectral resolution. We demonstrate its efficacy for recording the hyperspectral wavefront cube from single-pulse acquisitions at the Apollon multi-petawatt laser facility, and for performing multispectral microscopic imaging of dispersive phase objects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wavefront sensing and quantitative phase imaging are widely used for beam metrology, adaptive optics1 and biomedical imaging2. A wavefront sensor (WFS) typically measures the wavefront of a single monochromatic beam. For broadband beams, it is assumed that the wavefronts are achromatic, otherwise, the WFS can only measure a meaningless spectrally-averaged wavefront. Spectrally resolved WFS is typically required to quantify spatio-spectral coupling in high power laser metrolgy3, to study light matter interaction in plasma4, to image material dispersion5 or to measure hemoglobin concentration in living organisms6. In these applications, single-shot measurements are preferable or even required, especially to monitor fast events like in flow cytometry7, in pump probe experiments4, in light matter interaction8, or to characterize single laser pulses8,9. Assisted by a chirped pulse, ultrafast events can be acquired4,8. Also, the performances of ultrafast and high-power laser systems critically suffer from non-linear optical aberrations10. While scanning techniques can arguably characterize the spatiotemporal pulse profiles in high repetition rate systems3, they are incompatible with low repetition rate systems, such as petawatt and multi-petawatt-class lasers, due to potential drift with time and limited pulse-to-pulse reproducibility. The key challenge in this context lies in the spectral discrimination of wavefronts. In this manuscript, we distinguish between “multispectral” and “hyperspectral” techniques – referring, respectively, to approaches that resolve wavefronts over discrete spectral lines versus those spanning contiguous spectra, following the criterion established by Goetz11. This distinction is justified by the increased difficulty of sensing wavefronts across contiguous spectra compared to a discrete set of wavelengths. To manage continuous spectra, a spectrum-sampling Fabry–Perot interferometer was proposed in combination with a pair of gratings, which splits the spectral lines onto a conventional WFS, thereby enabling single-shot multispectral wavefront sensing over four spectral lines9. Although spectral sampling using a Fabry–Perot interferometer is efficient, the transmitted spectrum is sensitive to local wavefront tilt. Multispectral phase imaging could also be achieved by digital holography by encoding spectral information in the k-space12 or even without the need for a reference arm by combining a wavefront sensor with a multispectral camera13. Low-resolution (12 sampling points) and low-throughput single-shot hyperspectral wavefront sensing can be achieved using a coded aperture in combination with a phase retrieval algorithm14. More recently, hyperspectral phase maps could be rebuilt experimentally by combining a hyperspectral camera (so-called CASSI) with a phase diversity technique4. In a very recent publication, hyperspectral phase imaging could also be demonstrated by combining a diffraction grating with a micro-lens array15. So far, hyperspectral high-resolution WFS has only been investigated through numerical simulations combining a CASSI with a lateral shearing interferometer16. As a general principle, cascading existing techniques for achieving multiplexed optical sensing results in increased experimental complexity and spatial footprints, so hindering practical use and dissemination of the technique.

Here, we propose a single-shot hyperspectral wavefront sensing scheme that combines both spectral discrimination and wavefront sensing functionalities into a single mask imaged at a close distance from a camera sensor. Our approach thus builds on the same principles underlying conventional WFS17,18 in which the local wavefront tilts are encoded as local translations of the intensity pattern after propagation to the camera. This design has become one of the most widely used approaches in metrology and quantitative phase imaging19,20,21 because of its simplicity, compactness, single-shot capability, robustness to vibrations, and compatibility with broadband light sources. The application of this same principle to the multispectral/hyperspectral working regime has faced the challenge of spectral discrimination when dealing with broad spectra13.

Specifically, our system leverages both the so-called “angular memory effect”22 and the limited spectral correlation width23 occurring at a short distance from the output of a multicore fiber bundle (MCF). The angular memory effect encodes wavefront gradients in intensity pattern displacements24, while the limited spectral correlation width ensures distinct pattern encoding. The proposed instrument thus inherits the advantages of conventional WFS with only a modest increase in computational post-processing complexity and no need for regularization. We demonstrate the quantitative nature of our approach on well-defined optical systems. Next, we demonstrate the practical usability of our instrument by characterizing the hyperspectral wavefront cube from a single-pulse beam of multi-PW laser line at the Apollon laser facility, captured in a single-shot image acquisition. Finally, since our system relies on Hartmann deflectometry, it enables tuning the trade-off between spatial resolution and phase sensitivity24. We thus show that our implementation also enables single-shot, multispectral, quantitative phase microscopy with a high spatial resolution.

Results

Conceptual framework

Suitable optical mask for single-shot hyperspectral WFS

In the quest for instrument simplification, spectrally resolved wavefront sensing calls for a single optical element that simultaneously provides both spectral discrimination and wavefront sensitivity.

Several masks can be placed in the close vicinity of a camera that result in wavefront-sensitive intensity patterns: arrays of holes, microlens arrays17, meta-micro-lens arrays25, thin diffuser24, diffraction gratings26. A key characteristic for wavefront reconstruction is that a local tilt of the wavefront is transmitted through the mask, such that a wavefront tilt at the entrance of the mask results in a local translation of the intensity pattern at the camera plane. This principle, generalized in the context of scattering media and coined “memory effect”22, is satisfied by optical elements whose transmission matrix is diagonal in the canonical basis.

The spectral sensitivity of a mask is characterized by the spectral correlation width of the intensity patterns at the camera. All the masks listed above provide highly achromatic WFS properties. Spectral decorrelation may arise from chromatic dispersion within the mask itself or from free-space propagation over the distance d between the mask and the camera. However, axial dilation of intensity patterns due to free-space propagation27,28 contributes only marginally to spectral sensitivity when the mask is positionned at millimeter-scale distances24. To achieve hyperspectral WFS, the use of spectrally dispersive optics is therefore required. For interference effects to be wavelength-sensitive, these optics must involve a diversity of large optical path lengths. Nanometer-scale spectral sensitivity is typically achieved using complex media, such as multiply scattering samples29 or multimode fibers30. Notably, diffraction gratings are achromatic at short distances19 and thin diffusers – which we have previously shown to enable effective WFS – are only weakly dispersive24. Furthermore, complex media have been shown to be well suited for multiplexed spectral31,32 and polarimetric33 imaging, and even for multiplexed wavefront sensing in a single spectral channel34.

Therefore, optics that satisfy both spectral and angular properties required for achieving spectrally resolved wavefront sensing are not numerous. For instance, thick multiply scattering diffusers exhibit improved spectral sensitivity at the expense of degraded angular memory effect as thickness increases, drastically limiting the applicability to WFS22. In contrast, MCF exhibit both large angular memory effect35 and narrowband spectral correlation properties36. MCF exhibit a diagonal transmission matrix if fibers are perfectly monomode and uncoupled. In practice, many bundles are composed of few-modes fibers, so limiting the angular range of the memory effect. The physical mechanism behind the limited spectral correlation width in these fibers is still unclear but involves statistical dispersion in longitudinal wavenumbers in individual fibers due to variations in their diameters and potentially coupling between fibers. This dispersion is not specified by manufacturers and probably results from a lack of control in the fabrication process.

Image formation

The speckle pattern created by a scattering medium exhibiting an angular memory effect22 encodes the incident wavefront gradients into local speckle grains displacements at a short distance d24,34,37,38,39,40. For a monochromatic light beam, the relationship between a reference speckle pattern R(x, y) obtained under plane wave illumination and a speckle pattern M(x, y) obtained with unknown beam wavefront and intensity profile is:

where α(x, y) is the beam intensity and u(x, y), v(x, y) the components of the vector displacement map induced by the wavefront gradient. The spatial-phase gradient ∇⊥φ is related to u(x, y) and v(x, y) according to:

Measuring the displacement map (u, v) thus enables the reconstruction of the wavefront φ by a numerical integration step41,42,43.

In addition, the propagation through a complex medium encodes spectral information into uncorrelated speckle patterns23. The possibility to unmix such statistically independent speckle patterns under broadband illumination enables spectroscopy29,30 and even hyperspectral intensity imaging31,32. In these systems, the spectral resolution is determined by the number of interfering spatial modes, which typically scales with the spectral correlation width of the scattering medium, δλmedium, defining the spectral detuning necessary for speckle decorrelation to occur44.

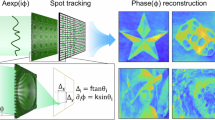

As argued above, to achieve single-shot spectrally resolved wavefront sensing, the Hartmann mask must be carefully chosen. Here we suggest using a MCF which demonstrated both a wide angular memory effect35 and a limited spectral correlation width36,45. The latter can be tuned by adjusting the length of the MCF (see Supplementary Fig. S4). As illustrated in Fig. 1a, b, when a broadband light beam illuminates such a complex medium having angular memory effect, a speckle intensity pattern M(x, y) is created at a distance d from the medium output, which can be imaged on a camera. This speckle is the sum, over the beam spectrum, of the monochromatic reference speckle intensity patterns R(x, y, λ), weighted by the spatially-dependent power spectrum amplitude of the beam intensity α(x, y, λ), and distorted according to the incident hyperspectral phase gradients:

where u(x, y, λ), v(x, y, λ) are the displacements induced by the phase gradients \(\left(\frac{\partial \varphi }{\partial x},\frac{\partial \varphi }{\partial y}\right)\) according to Eq. (2) (Fig. 1b). Therefore, because of the spectral diversity of speckles, both the spectro-spatial phases and amplitudes information of the incident field are encoded and multiplexed in the single speckle pattern image M(x, y). Since spectral information is spatially encoded in the speckle patterns captured by the camera, increasing spectral resolution requires allocating more camera pixels to each sampling point, which in turn reduces the number of spatial sampling points on the wavefront sensor. Ultimately, this trade-off between the number of spectral and spatial modes is made with the contraint that the total number of modes is limited by the number of camera pixels (see Supplementary Section S2).

a Unknown multispectral wavefronts are imaged onto the input facet of a multicore fiber. A plane at a distance d from the output facet is imaged onto a camera using a ×10, 0.3NA microscope objective and a f = 300 mm tube lens. b A multiplexed image (i) consists of a sum of locally translated reference intensity patterns (ii) according to the model (iii). The set of reference patterns (ii) are sequentially measured under monochromatic and plane wave illumination. The wavefronts (iv) and the intensities are then reconstructed by solving the inverse problem. c Angular correlation of the wavefront sensor measured at four wavelengths. d Spectral correlation width of the wavefront sensor as a function of the wavelength.

Reconstruction algorithm

The inverse problem in Eq. (3), summarized in Fig. 1b, is solved doing the two following assumptions: (i) the displacements u(x, y, λ) and v(x, y, λ) are sufficiently small, relative to the speckle grain size, to justify a first-order Taylor expansion of Eq. (3). (ii) Both the beam amplitude α and wavefront gradient (i.e. (u, v)) can be considered as constant within a given neighborhood. This latter assumption is at the basis of the Lucas–Kanade optical flow algorithm46, a variant of which we use here. Over this neighborhood, Eq. (3) can be re-written in the discretized matrix formalism as

where \(\widetilde{R}=[{R}_{i},{\partial }_{x}{R}_{i},{\partial }_{y}{R}_{i}]\) is the matrix composed of all the reference speckles Ri measured at wavelengths \({({\lambda }_{i})}_{i\in [1:{N}_{\lambda }]}\) together with their partial derivatives (∂xRi, ∂yRi) along x and y coordinates, respectively. \(X={[{\alpha }_{i},{u}_{i}{\alpha }_{i},{v}_{i}{\alpha }_{i}]}^{T}\) is the sought-for vector containing both the displacements (ui, vi) and the beam amplitudes αi at each λi wavelength.

For a discrete set of wavelength (i.e. for multipsectral imaging), the matrix Eq. (4) is solved over a sliding Gaussian window based on a least square minimization by computing the Moore–Penrose pseudo-inverse \({X}^{*}={({\widetilde{R}}^{T}\widetilde{R})}^{-1}\widetilde{R}M\). When a contiguous spectrum is considered (i.e. for hyperspectral imaging), Eq. (4) is solved over a set of patches covering the camera surface, using a truncated singular value decomposition (SVD) estimation47 where the low singular values are filtered out with a half-Gaussian function of width σSVD48.

The first order Taylor expansion performed to linearize Eq. (3) is only valid over displacements of the order of one speckle grain size (Supplementary Fig. S5b). To make the resolution robust to larger displacements, we implemented an iterative multi-scale registration algorithm49. The principle of the multi-scale approach consists in adjusting the speckle grain size at each iteration by Gaussian-filtering all images (M and R), thereby ensuring the first order approximation remains valid at each step by distorting the reference images according to the estimated larger-scaled displacement maps. The filter width σscale is then progressively decreased to measure finer displacement structures while preserving robustness to noise (Supplementary Fig. 5c). The detailed description of the inversion process, including the definition of the neighborhood and wavelength sampling, can be found in the Methods section and the algorithm workflow is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S6.

After solving Eq. (4) over a dense set of patches, a numerical integration of the displacement maps (ui, vi) is achieved in the Fourier domain. To avoid artifacts associated with periodic boundary conditions, Fourier integration is achieved after symmetrizing the gradient vector field42.

Experimental results

Optical characteristics of our system

The built-up hyperspectral wavefront sensor consists of a few-mode MCF (FIGH-100-1500N, Fujikura, Japan), a relay imaging system (×10, 0.3NA microscope objective and a 300 mm tube lens), and a camera (PCO Panda 4.2) that image the output facet of the MCF at a distance d. MCFs exhibit both angular memory effects and a limited spectral correlation width simultaneously. The spectral sensitivity results from the statistical dispersion of optical path lengths between cores, which is an inherent characteristic of MCF45. In our case, the angular correlation of the few-mode MCF, measured by tilting a collimated beam at the entrance of its input facet, exhibits a ≃ 30% drop for a tilt of 20 mrad (See Fig. 1c and Sec. for technical details). This limited angular memory effect reduces our ability to recognize speckles and reconstruct wavefronts. Our experiments were conducted within this range, thereby validating this lower bound of the dynamic range for our wavefront sensor implementation. This limited angular correlation is attributed to the fact that the MCF is made of few-modes fibers (≃4) and not monomode fibers.

As detailed in the Supplementary Information, once interference occurs between even a few cores, the spectral correlation width is determined solely by the intrinsic properties of the fiber (see Supplementary Fig. S4). For a distance d = 88 mm between the fiber image plane and the camera, we experimentally measured correlation widths on the order of 2 nm across the entire 500−800 nm spectral range (Fig. 1d). Both the angular memory effect and the resulting spectral correlation widths are well suited for hyperspectral wavefront sensing applications.

The experimental parameters must then be chosen based on the desired measurement characteristics. In particular, the required wavefront sensitivity defines the optimal distance d between the MCF and the camera. Given that our algorithm can reliably detect displacements as small as 1/50 of a pixel (see Supplementary Fig. S5b), increasing d enhances sensitivity. However, due to free-space propagation, this same distance also sets the spatial resolution of the wavefront sensor, which scales as NA ⋅ d, where NA is the numerical aperture of the MCF. Finally, the number resolvable spectral channels is linked to the ability to solve the inverse problem, which depends on the rank of the calibration matrix that encodes the reference patterns across the desired spectral range. According to the Marchenko-Pastur law for random matrices (See Supplementary Section S2), the distribution of singular values is governed by the ratio r = Nλ/M, where Nλ is the number of desired spectral channels and \(M={\left(\frac{{{{\rm{NA}}}}}{\pi {k}_{0}P}\right)}^{2}\) is the number of independent spatial modes sampled within a given patch, with k0 the central wavenumber and P the patch size that should match the spatial resolution NA × d. The upper bound for the condition number κ, which reflects the invertibility and stability of the problem, is given by

as detailed in Supplementary Section S2.2.1. To ensure a well-conditioned system, the number of spectral channels Nλ must be chosen such that κ remains sufficiently small, depending on the desired reconstruction fidelity and tolerance to noise.

Here, we demonstrate two implementations of our instrument corresponding to two trade-offs between spatial and spectral resolutions:

-

1.

One hyperspectral wavefront sensing modality measuring the first few Zernike wavefront modes over ≃20 spectral contiguous channels over a continuous 100-nm-wide spectrum.

-

2.

One quantitative multispectral and high-resolution wavefront imaging modality (220 × 220 pixels) performed at three discrete wavelengths in a microscopic imaging configuration.

Quantitative hyperspectral wavefront sensing

To verify the instrument’s quantitativity, a first setup was implemented to perform hyperspectral wavefront sensing over a continuous spectrum using simple test optical systems. The test optical systems under consideration were: three wedge prisms made of NBK7 material (with deviation angles of 2∘, 4∘, and 6∘ at 633 nm), and two afocal lens-pair systems (f = 50 mm) in NBK7 and SF11 materials. A supercontinnum laser coupled with a computer-controled filter box was used as a light source. The output plane of the optical system under test was imaged onto the MCF facet using a 1: 3 demagnifying telescope. The distance d ≃ 90 mm between the fiber output image plane and the camera was finely calibrated over the whole 100-nm-wide spectrum of interest, so taking into account chromatic aberrations of relay optics. For numerical reconstruction, the patch size at the camera was qualitatively adjusted to match the diffraction pattern of a single fiber after free space propagation, resulting in the reconstruction of phase and intensity maps of resolution 16 × 16-patches across a 100 nm spectral range with a spectral resolution of 5 nm. Next, the wavefronts were reconstructed both from the single broadband multiplexed images and from sequential images acquisition while scanning the spectrum. Throughout the article, we use the following terminology: multiplexed acquisition refers to a single-shot measurement of the spectrally resolved wavefront datacube, while sequential acquisition refers to a series of quasi-monochromatic wavefront measurements obtained by scanning the spectrum. More details about the experiment and data processing are given in the Methods section. An illustration of the reconstructed multiplexed and sequential wavefronts is shown in Fig. 2b for the 2∘ prism at 640 nm, while Fig. 2d similarly provides an illustration for the SF11 afocal system at 560 nm. The wavefront accuracy evaluated by computing the root mean square error (RMSE) between the expected and measured wavefronts over the whole spectrum reconstructed from the prisms experiments, is 1.3 nm (i.e.λ/450 at 600 nm) for the sequential reconstruction and 9.1 nm (i.e.λ/65 at 600 nm) for the multiplexed reconstruction.

a Comparison of the differential deviation angle induced by various prisms (2∘, 4∘ and 6∘) as a function of the wavelengths, using sequential measurements, single-shot multiplexed measurements and expected values. b Reconstructed tilted wavefronts at 640 nm comparing sequential reconstruction (S), single-shot multiplexed reconstruction (M), and the residual difference between them (R). c Comparison of the spectral defocus measured for two afocal systems (f1 = f2 = 50 mm) in NBK7 (in cyan) and SF11 (red) as a function of the wavelengths, with sequential measurements, single-shot multiplexed measurements and calculated expected values. d Reconstructed defocus wavefronts from the SF11 afocal system at 560 nm comparing sequential measurements (S), single-shot multiplexed (M), and the residual difference between them (R).

Finally, we extracted the tip/tilt and defocus components from the wavefronts, for the prisms and afocal systems, respectively, and measured the differential chromatic contribution, taking 600 nm as an arbitrary reference wavelength. These results are shown in Fig. 2a for the prisms, and in Fig. 2c for the afocal systems. Results obtained from multiplexed measurements exhibit excellent agreement with the ones obtained from sequential data. These experimental results were further compared with values expected from numerical simulations (based on the geometrical specifications of optics and the tabulated refractive indices of the materials). The theoretical spectral defocus induced by the afocal systems were computed within the frame of the thin lens approximation. All measurements show excellent agreement with one another and together with theoretical expectations and demonstrate the quantitative nature of our hyperspectral wavefront sensing approach.

Single pulse reconstruction at the Apollon laser facility

Next, we installed our single-shot hyperspectral wavefront sensor in the Long Focus Area (LFA) at the Apollon multi-PW laser facility50 (Saint-Aubin, France). The full footprint of our wavefront sensor does not exceed 100 cm2 and could be directly integrated into the diagnostics setup of the Apollon laser in a few hours only. Wavefront measurements were carried out through the 1PW beam-line, using a test laser beam having 50 mJ pulse energies at 10 Hz repetition rate (activating 2 amplification stages out of 5). Since following the very same optical path as in the full-energy configuration (nominal pulse-energy of 15J at a rate of \(1\,{{{\rm{shot/min}}}}\)), the laser beam was carrying the main static residual spatiotemporal coupling aberrations of the system. The 140 mm diameter laser beam was demagnified down to a beam diameter of 0.7 mm at the input facet of the MCF with achromatic telescope relay systems. The hyperspectral wavefront sensor was calibrated in situ over the spectral range 650−1000 nm with a resolution of 1 nm. More details about the system and its calibration can be found in the Methods section.

The multiplexed speckle image is shown in Fig. 3a. The beam exhibits a central hole resulting from the sampling mirror of the current LFA configuration (see Methods). From this single image, the ≃40-nm-wide spectrum of the laser is retrieved (Fig. 3b) together with hyperspectral intensity beam profiles (Fig. 3c) showing very good agreement with the real Apollon beam characteristics. The hyperspectral optical path differences (OPD) are also retrieved (see illustration of the OPD in Fig. 3d for the wavelength 825 nm). Before integration of wavefront gradients, the missing information in the central zero-intensity region was filled in using a median filter. The measured wavefronts (Fig. 3d) mostly present low order aberrations. The differential chromatic aberrations between 785 nm and 825 nm, shown in Fig. 3e, mostly exhibits chromatic defocus but negligible spectral tilt, so demonstrating the excellent alignement of the Apollon laser system (up to a few μrad at the WFS plane). The residual spectral tilt and defocus are plotted in Fig. 3f, g. The chromatic defocus is measured to be about 50 nm PtV (λ/16) over the FWHM-bandwidth of the Apollon pulses, corresponding to a ± zR /8 longitudinal depth of focus, with zR the Rayleigh length of the focused beam. This value is also in good agreement with the theoretically expected longitudinal chromatism of the Apollon beam transport system employing in its front-end part relay imaging telescopes based on simple singlet fused silica lenses for an aperture up to 18 mm in diameter51.

a Multiplexed speckle captured by the camera. b Reconstructed power spectrum derived from the multiplexed data. c Intensity profiles reconstructed at 805 nm and 825 nm. d Wavefront measured at 825 nm. e Wavefront difference between 785 nm and 825 nm. f Spectral deviation angles across the pulse spectrum. g Peak-to-valley spectral defocus variation across the pulse spectrum. h Intensity at the focal plane computed from the measured pupil electric field. The colormap’s maximum value is scaled according to the peak intensity of an unaberrated focus. i Reconstructed ideal electric fields (dark) and actual electric fields (red-yellow) at the two positions indicated by the arrows in (h), assuming a flat spectral phase at the center of the focus. The gray lines represent the real part of the electric field.

To characterize laser pulses in the temporal domain, measuring the spectral phase is required, at least within a sub-aperture of the near-field beam50. In the Apollon laser system, the spectral phase is routinely measured and optimized for the central portion of the beam. This enables pulse compression nearly to the Fourier transform limit (FTL). The resulting focus at the focal plane and the electric field time traces at the center of the focus and on one lobe are presented in Fig. 3h, i assuming a flat spectral phase at the center of the focus and preserving the missing hole in the amplitude pupil data. The power spectrum was apodized with a Tukey window with α = 0.35. The measurements realized in this study are in agreement with previous multi-shot characterization campaigns and indicate negligible peak intensity losses in the order of 15% compared to an ideal focus. In contrast to multi-shot acquisition systems, our instrument now enables the characterization of potential non-linear spatio-temporal coupling at the single-pulse level.

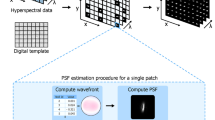

Multispectral quantitative phase microscopy

Single-shot multispectral imaging is also of interest for microscopy applications. We thus implemented our system in high-spatial resolution working regime by reducing the distance d down to ≈ 6mm between the image of the fiber-bundle output and the camera. The distances d were accurately measured over the full field of view (Supplementary Fig. S7). The sample was illuminated in transmission mode with a custom-built source based on three dielectric bandpass filters (480/20 nm, 580/10 nm and 690/10 nm), and imaged onto the PCF using a ×20 magnification and 0.4NA microscope objective. The PSF sampling factor by the MCF is dictated by the 4.5 μm mean nearest-neighbor distance between fiber cores and varies in the range between 2.7 (at 480 nm) and 3.8 (at 690 nm). Eq. (4) was solved using a Moore–Penrose pseudo-inversion over a sliding Gaussian window with standard deviation σGauss = 4pixels. The sample was prepared, consisting in 5.2 μm PMMA beads immersed in an aqueous solution. Sucrose was added to the solution to reduce the refractive index mismatch between water and PMMA. A chromophore (BlueBrillant FCF) was also added in order to introduce a controled amount of spectral dispersion52. All details regarding the optical system, the sample preparation and the algorithm can be found in the Methods section. Then, multiplexed and sequential multispectral wavefront imaging of the sample was carried out.

The single-shot multispectral intensities and OPDs are shown in Fig. 4a. Noteworthy, the imaging system between the sample and the WFS exhibits a slight chromatic aberrations since the red channel (690 nm) appears unfocused. Based on both the measured intensity and OPDs, numerical refocusing is performed (Supplementary Fig. S8). Comparison of OPD profiles obtained by sequential and multiplexed measurements can then be done and confronted to theoretical expectations based on the solution composition and the specified geometric characteristics of the beads (Fig. 4b). The only missing parameters, the exact sucrose and chromophore concentrations, were fitted from experimental data. The dispersion of the sample clearly appears in the images shown in Fig. 4c where the difference in OPD at 480 nm and 690 nm is displayed. Finally, the peak OPDs are plotted in Fig. 4d both from sequential and multiplexed data, demonstrating very good agreement between experimental results and the spectral dispersion expected from theoretical modeling. The scattering observed in the measurements of refractive indices is due to the dispersion in the sizes of the micro-beads (Supplementary Fig. S9).

a Intensity and OPD measurements captured at the three wavelengths in single-shot. Scale bar = 10 μm. b OPD cross-sections of the bead located at the center of the field of view (white arrow in (a)), after numerical refocusing from sequential (dashed line) and multiplexed (solid line) reconstructions. For comparison, theoretical expectation is shown as the gray strip. c Differential OPD between the blue (480 nm) and red (690 nm) channels. d Measured peak OPDs, fitted by a dispersion model considering the contribution of both PMMA and the solution (made of water, sucrose, and FCF chromophore).

Discussion

In summary, we have introduced a hyperspectral wavefront sensor with an accuracy of approximately λ/60 and a tunable spatio-spectral resolution. The sensitivity, defined as the minimum measurable angle, is proportional to the minimal detectable displacement using the implemented optical flow algorithm, which is about 1/50th pixel (Supplementary Fig. 5b). For the two proposed implementations, the sensitivity is 7.5 μrad and 0.35 μrad for the high spatial resolution and high spectral resolution experiments, respectively.

The maximum achievable spectral resolution is determined by the spectral correlation width of the MCF (δλmedium ≈ 2 nm), and can therefore be changed by tuning the fiber length. Practically, the effective spectral resolution is controlled by the width of the half-Gaussian filter σSVD used to truncate the singular values. The number of recovered spectral channels is then qualitatively given by 3 σlaser/σSVD, where σlaser is the beam bandwidth, and the factor 3 accounts for the three independent information recovered: the amplitude and the phase gradient components. Based on our experimental results, we assess that the spectral resolution of the hyperspectral wavefront sensor instrument can be qualitatively estimated as Nλ = 6 σlaser/σSVD ≈ 20.

The spatial resolution is limited by the free-space propagation distance d between the output facet of the MCF and the camera sensor. At short distances, in the high-spatial resolution microscopy implementation, the spatial resolution is limited by the mean inter-core distance equal to 4.5 μm. In the high-sensitivity mode used for laser and optics metrology where the distance d is large, the spatial resolution is 66 μm at the output facet of the MCF. For quantitative phase microscopy, the point spread function of the incoming beam (after magnification) should be properly sampled by the fiber cores. In our current setup, the speckle grains measured on the camera are oversampled (12 × 12 pixels), suggesting that a larger field of view could be achieved with a bundle containing more fibers. Moreover, the small size of the current MCF (0.7 mm in diameter) required a relay imaging system, which introduces chromatic aberrations that must be taken into account through an accurate calibration of the system.

The post-processing time to unmix the spectral components and compute the intensity and wavefront images was 5 min. in the laser and optics metrology experiments, and 50 s. per scale for the high spatial resolution implementation, with the matrix inversion being the most time-consuming step (on laptop equipped with an Intel Core i7-10710U CPU). In this latter configuration involving large dynamics of the wavefront gradient, the multiscale processing algorithm, requiring multiple matrix inversions, is required for phase imaging to be quantitative. However, for qualitative real-time monitoring, image processing can be achieved on a single scale wherein the matrix inversion step, only requiring the calibration patterns, can be performed once for all and in advance. Optimizing the reconstruction speed, combined with the use of a full-field spatial light modulator53,54,55, could enable real-time adaptive optics to correct chromatic aberrations and spatio-temporal coupling.

As a perspective, the hyperspectral wavefront sensor presented here appears as perfectly suited for characterizing the spatio-temporal coupling effects of single pulses in ultrashort laser installations like Apollon. Single-pulse metrology is especially critical in this case since Apollon operate at a rate of only 1 shot per minute at full power (both for the 1 PW and 10 PW beam-lines). Our instrument now enables the investigation of potential nonlinear chromatic effects56, and a more precise and comprehensive estimation of the on-the-target focused intensity. Furthermore, the system could be extended with additional multiplexing capabilities, such as polarimetric measurements15,57, enabling even richer characterization of complex light fields. Additionally, the high spatial resolution system could be combined with tomographic microscopes58 to extract not only the optical path delay dispersion but also the refractive index dispersion of a sample.

Methods

Optical design of the wavefront sensor

The output facet of a 1-cm-long multicore few-mode fiber (FIGH-100-1500N, Fujikura, Japan) is imaged at a distance d from a camera (PCO Panda 4.2) with a microscope objective (×10, NA = 0.3) on a translation stage and a tube lens (f = 300 mm and f = 200 mm for the hyperspectral system and multispectral system respectively), as illustrated in Fig. 1a. The fraction of transmitted light energy through the MCF is 95%.

Light sources

For hyperspectral WFS, the optical system is illuminated using narrow linewidth collimated beams generated by broadband laser sources and filtered using computer-driven filter boxes. For the prism/afocal experiment, the supercontinuum source (Leukos, Electro Vis) and the filter box (Leukos, Bepop) provided a minimum bandwidth of ≃5 nm in the spectral range between 500 nm and 800 nm. At the Apollon laser, a Ti:Sa laser (Rainbow, Femtolasers Produktions GmbH, Austria) covering the spectral range 650−1000 nm was used for calibration, in association with a custom-built monochromator. The monochromator consisted of a pair of blazed gratings, an afocal telescope and a slit mounted on a motorized translation stage. After the monochromator, the beam had a linewidth of ≃2 nm over the spectral range 730−860 nm. The calibration of the monochromators was completed, and their performance was evaluated using a spectrometer (Ocean, ST VIS-25). At the output of the monochromators the beams were spatially filtered using single mode fibers and re-collimated before being sent on the input facet of the MCF or the test optics. The reference speckle patterns Ri were then sequentially recorded over the given spectral ranges by steps of 1 nm. Broadband illumination could be obtained by tuning the linewidth up to 100 nm for the commercial filter box, and simply by removing the slit from the custom-built monochromator.

For the multispectral wavefront imaging experiment, a white halogen lamp, spatially filtered by a pinhole and collimated, was split into three optical paths. The three illuminating wavelengths were obtained by inserting off-the-shelf available bandpass filters (480/20 nm, 580/10 nm and 690/10 nm), placed in each path before recombination using beam-splitters.

Spectral calibration of the hyperspectral WFS

Multicore fibers (MCFs) exhibit a limited spectral correlation width due to the inherent statistical dispersion of optical path lengths between cores45. The spectral correlation width of the MCF was measured over the full spectrum by measuring the speckle contrast C as a function of the central wavelength of the 5-nm-wide laser line. The contrast is directly related to the number of independent speckles Nλ present in the image as: Nλ = 1/C2 23,59. The speckle contrast decreases as the number of independent spectral speckles increases. We thus conventionally define the spectral correlation width of the MCF as δλmedium = σlaser/Nλ where σlaser is the linewidth of the laser used. We initially purchased a 50-cm-long MCF which we shortened down to 1 cm to tune its spectral correlation width in accordance with the requirements of our applications (see Supplementary Fig. S4). As shown in Fig. 1d, we measured correlation widths of the order of 2 nm over the full spectrum in between 500 nm and 800 nm. The spectral width of the MCF ultimately determines the maximum spectral resolution of our hyperspectral WFS.

Angular memory effect & calibration of the distance d

Multicore fibers (MCFs) exhibit an angular memory effect. The angular correlation, limited by the number of modes in individual fibers, was measured experimentally. The tilt angle of a collimated beam was scanned at the input facet of the MCF. The tilt angle was controlled by translating the output of a monomode fiber in the focal plane of a fixed collimating lens (f = 30 mm) and the output of the lens was then conjugated with the input facet of the MCF using a Gin = 1 : 6 magnification afocal telescope. The output speckle measured at a distance d on the camera were then digitally cross-correlated to measure the angular memory effect. The results shown in Fig. 1c exhibit a ≃ 30% drop in correlation after a 20 mrad tilt, over the full spectrum of interest. This limited angular memory effect reduces our ability to recognize speckles and reconstruct wavefronts, thereby restricting the number of accessible spectro-spatial modes.

The described system also allowed an accurate measurement of the distance d between the output facet image and the camera, accounting for potential chromatic defocus in the relay imaging system. The distance d was measured using Eq. (2), relying on tilt-angle conservation between the input and the output facets of the MCF, and within the range of the angular memory effect. Considering the magnification Gin and Gout of the relay imaging system before and after the MCF, respectively, the distance d is measured according to:

where \(\langle \delta {u}_{{{{\rm{cam}}}}} \rangle\) is the mean displacement measured over the camera and δusource the known displacement amount of the monomode fiber used as a point source. For the hyperspectral experiments, an average distance d across the field of view was measured. In the multispectral experiments, to achieve metrology-grade phase imaging, the distance d was estimated individually for each camera pixel. The resulting d-maps obtained for each wavelength were fitted using low-order (N = 3) 2D polynomials, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S7.

Description of the hyperspectral wavefront sensing experiments

The metrological measurements on the prisms and afocal systems where carried out by imaging the test optics with afocal imaging telescope with de-magnification 1 : 3, onto the MCF. Special care was taken to align the test beams with the calibrating beams at the entrance of the MCF. The imaged field of view corresponded to an area of 2.4 × 2.4 mm2 of the test optics. The distance d between the output facet image plane and the camera was accurately measured, and was observed to vary from 88 mm to 97 mm over the spectrum of interest (550–650 nm). This relatively large mean distance was intentionally chosen to enhance sensitivity to small wavefront distortions, such as those produced by chromatic optical elements that simulate spatio-temporal coupling in typical ultrashort laser facility systems.

Description of the Apollon laser beam metrology

For hyperspectral WFS acquisitions, the 140 mm diameter Apollon laser beam was sampled after the focal plane of the end-chain focusing optic (F = 6 m) and collimated to 7 mm diameter beam using afocal telescopes within the interaction chamber of the LFA. Relay imaging systems, composed of achromatic lenses both in vacuum and in air, were employed to transfer the image plane (defined at the entrance of the experimental chamber) to the input of the hyperspectral WFS. The overall demagnification factor of the imaging system was 1: 200, reducing the beam diameter to 0.7 mm at the input facet of the MCF. The corresponding field of view at the MCF facet is 0.8 × 0.8 mm2.

Description of the multispectral wavefront microscope

Poly(methyl methacrylate) beads of 5.2 μm (PMMA-R-5.2, microparticles GmbH) were deposited on glass microscope slides. The dry beads were then covered with a solution consisting in blue brilliant absorber FCF in water (E133 in water, Vahine, Avignon, France) mixed with sucrose (2 g/ml) and then sealed with a cover glass. A description of the model used to describe our sample refractive index can be found in Supplementary Materials. The beads sample was imaged onto the input plane of the wavefront sensor by a microscope imaging system, consisting of a ×20, 0.4NA microscope objective and a 180 mm tube lens. The resulting field of view was 120 × 120 μm2. The distances d between the output facet image and the camera were accurately measured over the full field of view and varied in the range between 4 mm and 8 mm (see Supplementary Fig. S7) after taking into account the magnification after the MCF.

Data processing

For multispectral reconstruction involving a limited number of wavelengths with spectral shifts exceeding several δλmedium, Eq. (4) can be addressed using the Moore–Penrose pseudoinverse: \({X}^{*}={({\widetilde{R}}^{T}\widetilde{R})}^{-1}\widetilde{R}M\) applied over a neighborhood defined by a Gaussian sliding windows. The full width at half maximum of the gaussian sliding window is selected to ensure that the condition number of the matrix \(\widetilde{R}\) remains below 10. Typically, for reconstruction using three discrete wavelengths, this size corresponds to the average distance between two speckle grains observed at the camera plane.

For hyperspectral wavefront reconstruction over a continuous (and contiguous) spectrum, the references are captured for a discrete set of wavelengths having a step smaller than the spectral correlation width of the MCF. We found that good performances were obtained for a spectral step equals to δλmedium/3. We solved Eq. (4) for a dense set of square patches covering the full camera surface. To solve Eq. (4) for a given patch, the corresponding matrix \(\widetilde{R}\) is inverted through a truncated singular value decomposition (SVD)47. The truncation aims at canceling the contribution of low singular values that dominates after inversion. They are thus filtered out by multiplying inverted singular values by a (half-)Gaussian function of width σSV D48. In practice, the value of σSV D is set empirically in order to reduce the oscillation-like artefacts appearing during the matrix inversion60. Furthermore, to speed up the processing time, a sparse SVD routine is used. The number of singular values conserved after SVD filtering (the σSV D value) will, in fine, drive the maximum spectral resolution of the system. Three singular values are needed per wavelength-band λi ± δλi/2 to reconstruct all the information: one singular value for the amplitude αi and two for the displacements (ui, vi). With our optical instrument, we used σSV D = 30 nm for a full spectral range spanning over 100 nm.

Both for multispectral and hyperspectral phase imaging, the first order Taylor expansion performed to linearize Eq. (3) is only valid over displacements of the order of one speckle grain size. For larger displacements, we implemented an iterative multi-scale version49. The principle of the multi-scale approach consists in adjusting the speckle grain size at each iteration by Gaussian-filtering all images (M and R). At each iteration, the reference images are distorted according to the estimated large-scaled displacement maps. The filter width σscale is then progressively decreased to measure finer displacement structures.

For the images acquired with the Apollon laser facility, an initial registration step was achieved by patches by digital image cross-correlation between the acquired multiplexed speckle and a synthetic broadbrand reference (i.e. the sum of the measured reference intensities) to compensate a displacement offset between the reference speckles and the multiplexed ones. This offset was due to a residual non co-linearity error between the Apollon laser beam and the calibrating beam.

A summary of the parameters used for the reconstructions, along with the resulting imaging characteristics, is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Image processing for multispectral microscopy

Additional post-processing was necessary to evaluate the dispersion of the PMMA bead sample in a BlueBrillant solution. Due to chromatic aberrations in the microscope imaging system, all three channels could not be simultaneously focused. Furthermore, air flow fluctuations in the experimental room introduced low-frequency background variations in the reconstructed optical path delays, with amplitudes comparable to the spectral dispersion. Defocus was corrected using the angular spectrum method within the Fresnel approximation. Assuming that the objects are transparent, the optimal numerical propagation distance was determined by minimizing the standard deviation of intensity images. The slowly-varying wavefront background was estimated by segmenting the image. At the bead positions, an interpolation was performed. This measured background was then filtered using a Gaussian low-pass filter with a full-width half-maximum of 5 pixels, and then subtracted from the optical path delay images. The complete reconstruction workflow is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S8. Finally the peak values of OPDs were measured at the center of each bead by averaging over a disk with a radius of 10 pixels (=0.6 μm).

Data availability

The data generated in the quantitative dispersion microscopy experiments and their related post-processing algorithms have been deposited in the Zenodo repository under accession code: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17523847.

Code availability

The post-processing algorithms used in the quantitative dispersion microscopy experiments have been deposited in the Zenodo repository under accession code: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17523847.

References

Hampson, K. M. et al. Adaptive optics for high-resolution imaging. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 1, 68 (2021).

Park, Y., Depeursinge, C. & Popescu, G. Quantitative phase imaging in biomedicine. Nat. Photonics 12, 578–589 (2018).

Jeandet, A. et al. Survey of spatio-temporal couplings throughout high-power ultrashort lasers. Opt. express 30, 3262–3288 (2022).

Tang, H. et al. Single-shot compressed optical field topography. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 244 (2022).

Song, J. et al. Triple-wavelength quantitative phase imaging with refractive index measurement. Opt. Lasers Eng. 156, 107110 (2022).

Park, Y., Yamauchi, T., Choi, W., Dasari, R. & Feld, M. S. Spectroscopic phase microscopy for quantifying hemoglobin concentrations in intact red blood cells. Opt. Lett. 34, 3668–3670 (2009).

Lee, K. C. et al. Quantitative phase imaging flow cytometry for ultra-large-scale single-cell biophysical phenotyping. Cytom. Part A 95, 510–520 (2019).

Wang, P., Liang, J. & Wang, L. V. Single-shot ultrafast imaging attaining 70 trillion frames per second. Nat. Commun. 11, 2091 (2020).

Kim, Y. G. et al. Single-shot spatiotemporal characterization of a multi-pw laser using a multispectral wavefront sensing method. Opt. Express 29, 19506–19514 (2021).

Danson, C. N. et al. Petawatt and exawatt class lasers worldwide. High. Power Laser Sci. Eng. 7, e54 (2019).

Goetz, A. F. Three decades of hyperspectral remote sensing of the Earth: a personal view. Remote Sens. Environ. 113, S5–S16 (2009).

Grace, E. et al. Single-shot complete spatiotemporal measurement of terawatt laser pulses. J. Opt. 23, 075505 (2021).

Dorrer, C. & Bahk, S.-W. Spatio-spectral characterization of broadband fields using multispectral imaging. Opt. Express 26, 33387–33399 (2018).

Smartsev, S. et al. Simple few-shot method for spectrally resolving the wavefront of an ultrashort laser pulse. Opt. Lett. 49, 1900–1903 (2024).

Howard, S. et al. Single-shot spatiotemporal vector field measurements of petawatt laser pulses. Nat. Photonics 19, 898–905 (2025).

Howard, S., Esslinger, J., Wang, R. H., Norreys, P. & Döpp, A. Hyperspectral compressive wavefront sensing. High. Power Laser Sci. Eng. 11, e32 (2023).

Platt, B. C. & Shack, R. History and principles of shack-hartmann wavefront sensing. J. Refract. Surg. 17, S573–S577 (2001).

Rouzé, B. et al. Extracting more than two orthogonal derivatives from a shack-hartmann wavefront sensor. Opt. Express 29, 5193–5204 (2021).

Bon, P., Maucort, G., Wattellier, B. & Monneret, S. Quadriwave lateral shearing interferometry for quantitative phase microscopy of living cells. Opt. Express 17, 13080–13094 (2009).

Baffou, G. Wavefront microscopy using quadriwave lateral shearing interferometry: from bioimaging to nanophotonics. ACS Photonics 10, 322–339 (2023).

Berto, P., Gachet, D., Bon, P., Monneret, S. & Rigneault, H. Wide-field vibrational phase imaging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 093902 (2012).

Feng, S., Kane, C., Lee, P. A. & Stone, A. D. Correlations and fluctuations of coherent wave transmission through disordered media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 834 (1988).

Goodman, J. W. Speckle Phenomena in Optics: Theory and Applications (Roberts and Company Publishers, 2007).

Berto, P., Rigneault, H. & Guillon, M. Wavefront sensing with a thin diffuser. Opt. Lett. 42, 5117–5120 (2017).

Go, G.-H. et al. Meta shack–hartmann wavefront sensor with large sampling density and large angular field of view: phase imaging of complex objects. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 187 (2024).

Primot, J. & Sogno, L. Achromatic three-wave (or more) lateral shearing interferometer. J. Optical Soc. Am. A 12, 2679–2685 (1995).

Vesga, A. G. et al. Focusing large spectral bandwidths through scattering media. Opt. Express 27, 28384–28394 (2019).

Zhu, L. et al. Chromato-axial memory effect through a forward-scattering slab. Optica 7, 338–345 (2020).

Metzger, N. K. et al. Harnessing speckle for a sub-femtometre resolved broadband wavemeter and laser stabilization. Nat. Commun. 8, 15610 (2017).

Redding, B., Popoff, S. M. & Cao, H. All-fiber spectrometer based on speckle pattern reconstruction. Opt. Express 21, 6584–6600 (2013).

French, R., Gigan, S. & Muskens, O. L. Speckle-based hyperspectral imaging combining multiple scattering and compressive sensing in nanowire mats. Opt. Lett. 42, 1820–1823 (2017).

Li, X., Greenberg, J. A. & Gehm, M. E. Single-shot multispectral imaging through a thin scatterer. Optica 6, 864–871 (2019).

Kohlgraf-Owens, T. & Dogariu, A. Spatially resolved scattering polarimeter. Opt. Lett. 34, 1321–1323 (2009).

Wu, T., Guillon, M., Tessier, G. & Berto, P. Multiplexed wavefront sensing with a thin diffuser. Optica 11, 297–304 (2024).

Porat, A. et al. Widefield lensless imaging through a fiber bundle via speckle correlations. Opt. Express 24, 16835–16855 (2016).

Andresen, E. R. et al. Measurement and compensation of residual group delay in a multi-core fiber for lensless endoscopy. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 32, 1221–1228 (2015).

Wang, C., Dun, X., Fu, Q. & Heidrich, W. Ultra-high resolution coded wavefront sensor. Opt. Express 25, 13736–13746 (2017).

Sun, J. et al. Quantitative phase imaging through an ultra-thin lensless fiber endoscope. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 204 (2022).

Bérujon, S., Ziegler, E., Cerbino, R. & Peverini, L. Two-dimensional x-ray beam phase sensing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 158102 (2012).

Wu, T. et al. 3d nanoparticle superlocalization with a thin diffuser. Opt. Lett. 47, 3079–3082 (2022).

Huang, L. et al. Comparison of two-dimensional integration methods for shape reconstruction from gradient data. Opt. Lasers Eng. 64, 1–11 (2015).

Bon, P., Monneret, S. & Wattellier, B. Noniterative boundary-artifact-free wavefront reconstruction from its derivatives. Appl. Opt. 51, 5698–5704 (2012).

Wu, T., Berto, P. & Guillon, M. Reference-less complex wavefields characterization with a high-resolution wavefront sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 251102 (2021).

Redding, B., Liew, S. F., Sarma, R. & Cao, H. Compact spectrometer based on a disordered photonic chip. Nat. Photonics 7, 746–751 (2013).

Accanto, N. et al. A flexible two-photon fiberscope for fast activity imaging and precise optogenetic photostimulation of neurons in freely moving mice. Neuron 111, 176–189 (2023).

Lucas, B. D. & Kanade, T. An iterative image registration technique with an application to stereo vision. Int. Jt. Conf. Artif. Intell. 2, 674–679 (1981).

Hansen, P. C. The truncated svd as a method for regularization. BIT Numer. Math. 27, 534–553 (1987).

Malone, J. D., Aggarwal, N., Waller, L. & Bowden, A. K. Diffuserspec: spectroscopy with scotch tape. Opt. Lett. 48, 323–326 (2023).

Weber, J. & Malik, J. Robust computation of optical flow in a multi-scale differential framework. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 14, 67–81 (1995).

Papadopoulos, D. et al. The apollon 10 pw laser: experimental and theoretical investigation of the temporal characteristics. High. Power Laser Sci. Eng. 4, e34 (2016).

Ranc, L. Etude et amélioration spatio-temporelles de l’intensité et du contraste dans les lasers PW. PhD thesis, Université Paris-Saclay (2022).

Sai, T., Saba, M., Dufresne, E. R., Steiner, U. & Wilts, B. D. Designing refractive index fluids using the kramers–kronig relations. Faraday Discuss. 223, 136–144 (2020).

Mounaix, M. et al. Time reversed optical waves by arbitrary vector spatiotemporal field generation. Nat. Commun. 11, 5813 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. Synthesizing ultrafast optical pulses with arbitrary spatiotemporal control. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq8314 (2022).

Cruz-Delgado, D. et al. Synthesis of ultrafast wavepackets with tailored spatiotemporal properties. Nat. Photonics 16, 686–691 (2022).

Zou, J. P., Coïc, H. & Papadopoulos, D. Spatiotemporal coupling investigations for ti:sapphire-based multi-pw lasers. High. Power Laser Sci. Eng. 10, e5 (2022).

Blochet, B., Lelu, G., Alonso, M. A. & Guillon, M. Quantitative polarimetric wavefront imaging. Optica 12, 907–913 (2025).

Sung, Y. Hyperspectral three-dimensional refractive-index imaging using snapshot optical tomography. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 014064 (2023).

Curry, N. et al. Direct determination of diffusion properties of random media from speckle contrast. Opt. Lett. 36, 3332–3334 (2011).

Shinn, M. Phantom oscillations in principal component analysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2311420120 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknoweldge the support from the team responsible for the Apollon laser facility. They also acknowledge Dan Oron, Ori Katz and Fabrice Harms for stimulating discussions and Christophe Tourain for helping with the preparation of MCFs. The authors acknowledge support from the French National Agency (MaxPhase, ANR-ANR-20-CE42-0006). P.B. and M.G. acknowledge support for the Insitut Universitaire de France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.B. built up the wavefront sensing systems and did experiments and data processing. N.L. and D.P. contributed to experiments. P.B. and D.P. contributed to experimental designs. M.G. designed and supervised the project. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.B., D.P. and M.G. are authors on a patent related to this work filed by Université Paris Cité, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Sorbonne Université, École Polytechnique and Comissariat à l’Énergie Atomique [no. EP3948191 (B1), filed on February 21, 2020, published on Sept 30th, 2020, and granted on March, 22, 2023]. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Spencer Jolly and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blochet, B., Lebas, N., Berto, P. et al. Single-shot hyperspectral wavefront imaging. Nat Commun 17, 137 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66847-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66847-w