Abstract

While solid electrolyte-excluded Si electrodes can form in situ lithiated monolithic structures with minimal side reactions, their poor performance at low operating pressures remains a formidable challenge for all-solid-state batteries. Herein, we propose an electrically conductive binder—poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly((styrene sulfonic acid)x-co-(maleic acid)y) (PEDOT:P(SSx-co-MAy))—that is scalable, fluorine-free, and water-processable. This binder offers sufficient e−-conductivity to eliminate carbon additives, while ensuring strong adhesion and electrochemical stability in contrast to conventional liquid electrolyte systems. Ex situ measurements reveal disrupted e-connectivity during delithiation at 5 MPa, resolved by employing PEDOT:P(SSx-co-MAy). The improved electrochemical performance of Si electrodes comprising PEDOT:P(SSx-co-MAy), compared with those using conventional polyvinylidene fluoride, is validated in (Li-In) | Li6PS5Cl | Si half cells and Si | Li6PS5Cl | LiNi0.70Co0.15Mn0.15O2 full cells at 30 °C and 5 MPa, achieving 134 mAh g−1 at 0.5 C with 86% capacity retention after 100 cycles. Finally, 233 mAh pouch-type Si || LiNi0.83Co0.12Mn0.05O2 ASSBs are demonstrated, highlighting the potential of PEDOT:P(SSx-co-MAy) as a practical binder platform for high-energy ASSBs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Owing to its high theoretical capacity (3580 mAh g−1 (Li15Si4)) and abundant availability, Si stands as a key anode material to increase the energy density of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) on a practical scale1,2,3. However, the substantial volume change during cycling ( > 300%) presents formidable challenges2,4,5. These changes lead to electrical contact loss and continuous electrolyte decomposition on freshly exposed surfaces, resulting in rapid capacity fading. Despite considerable progress achieved through diverse strategies, such as nanostructuring Si and electrolyte engineering4,6,7,8,9,10,11, liquid electrolytes (LEs) still face limitations, including electrolyte depletion12,13,14.

By replacing LEs with sulfide solid electrolytes (SEs), the initial development of Si electrodes for all-solid-state batteries (ASSBs) has closely followed the trajectory of LIBs15,16. Benefiting from their mechanical deformable properties17,18,19, compacted three-dimensional (3D) composite structured Si electrodes in ASSBs have been fabricated via a simple cold-pressing process with materials such as sulfide (e.g., Li6-xPS5-xCl1+x) and hydride SEs (e.g., LiBH4-LiI)18,20,21. However, these composite designs incorporating SEs face limitations due to degradation in interparticle contacts upon volume changes and the limited electrochemical stabilities of SEs22,23,24,25,26,27. A recent design of Si electrodes that excludes SEs has considerable potential, offering a solution unattainable with LEs28,29,30,31. Specifically, the exclusion of SEs from within the electrodes enables the mechanical sintering of Si particles upon lithiation. The resulting monolithic electrode forms a minimal 2D contact with separating SE layers. Consequently, electronic/ionic contacts are maintained while detrimental electrolyte decomposition can be limited. These attributes resulted in a stable performance of Si/polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) electrodes with a weight ratio of 99.9:0.1 in Si || LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 cells, achieving 80% capacity retention after 500 cycles under an operating pressure of 50 MPa29.

Despite their demonstrated positive potential, monolithic Si electrodes without SEs require further elaboration. Specifically, when operating at practically relevant pressures, a few megapascals at most, these Si electrodes exhibit much poorer performances32,33,34. Under these low operating pressures, several degradation modes are exacerbated. First, the Si electrodes tend to delaminate from the separating SE layer, leading to rapid capacity fading33. Our group has demonstrated that introducing Li+-conductive and adhesive Li-alloying metal interlayers, such as Ag, can mitigate this issue33. Second, despite the deformable properties of lithiated Si, its mechanical degradation cannot be completely avoided, as evidenced by the formation of vertical cracks after cycling34. This necessitates the incorporation of advanced binders, as witnessed in the advancements in LIB technology35,36,37,38. Finally, the e− conductivity of micron-sized Si alone is insufficient for acceptable rate performance, requiring the addition of carbon additives33. However, this demand also necessitates the inclusion of a considerable amount of binders, which disrupt ionic/electronic contacts and reduce energy density. These considerations strongly suggest the need for the development of advanced binders customized for Si electrodes in ASSBs, specifically those with e−-conductive and mechanically fortified binding properties. Along with these technical needs, it is also crucial to address the environmental impacts associated with binder development and adaptation39,40. Recent regulations targeting F-based polymers include conventional LIB binder PVDF within their scope41. In addition, the use of the harmful organic solvent N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP) poses environmental and safety concerns42.

Herein, we demonstrate e−-conductive binders with reinforced mechanical properties tailored for Si negative electrodes in ASSBs. These binders are conductive polymers, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly((styrene sulfonic acid)x-co-(maleic acid)y) (PEDOT:P(SSx-co-MAy) (PPMA). By controlling the ratio of PSS and PMA in the copolymers, we achieve both good electrical conductivity and binding property. In these polymers, PEDOT:PSS (PP) provides the e−-conducting pathways, while PMA enhances the binding ability. Notably, although PEDOT:PSS has been regarded as electrochemically unstable in the negative electrode potential range within LE systems, it demonstrates electrochemical and structural stability when applied to Si electrodes in ASSBs, owing to the solid-solid interfacial nature. Moreover, these binders are F-free and water-processable. Ex situ e− conductivity measurements using three-electrode cells reveal that the deployment of these e−-conductive binders increases the e− conductivity of Si electrodes in their pristine state by 36,000 times, from 5.5 × 10−9 to 2.0 × 10−4 S cm−1. In addition, these binders substantially mitigate the degradation of e− conductivity during delithiation compared to Si electrodes with conventional PVDF binders, accounting for the much higher capacity and its retention when tested in Li-In | (Li6PS5Cl (LPSCl)) | Si half cells at 5 MPa. The effects of varying ratios of PMA in PPMA are also investigated, highlighting the significance of binding properties. The Si | LPSCl | LiNi0.70Co0.15Mn0.15O2 (NCM) ASSB full cells with PPMA (and prelithiation) exhibited high capacities of 179 and 134 mAh gNCM−1 at 0.05 C and 0.5 C, respectively, with 72% capacity retention after 200 cycles at 30 °C and 5 MPa. Finally, 233 mAh pouch-type Si || LiNi0.83Co0.12Mn0.05O2 (NCM83) ASSBs are demonstrated.

Results

For Si electrodes with a Si/PVDF composition in a weight ratio of 97:3 in (Li-In) | LPSCl | Si half cells, reducing the operating pressure from 70 to 5 MPa resulted in a decrease in rate capability (Supplementary Fig. 1). For example, the capacity at 0.2 C and 70 MPa dropped from 2490 to 1820 mAh g−1 at 5 MPa, which is attributed to the increased e− resistance due to contact loss between particles32,33. Figure 1a shows a schematic of the lithiation–delithiation processes for Si electrodes utilizing the conventional insulating binder PVDF and e−-conductive binder. During lithiation, the Si particles undergo volume expansion and merge, forming monolithic structures. Upon delithiation, the volume decreases, and if the external pressure is low, cracks or voids may form. In contrast to insulating binder PVDF, e−-conductive binder helps to maintain electrical contact, thereby mitigating degradation. This mechanism is thoroughly investigated in subsequent sections.

Syntheses and characterization of PEDOT:P(SSx-co-MAy) (PPMA)

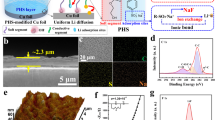

The synthetic process of the e−-conductive binders PP (PEDOT:PSS) or PPMA (PEDOT:P(SSx-co-MAy)) is illustrated in Fig. 1b. A precursor compound of PSS (poly(styrene sulfonic acid)) copolymerized with PMA (poly(maleic acid)) at different ratios, i.e., P(SSx-co-MAy), was prepared through the free-radical polymerization of styrene sulfonic acid sodium salt hydrate (NaSS) and MA. Subsequently, the EDOT monomer was polymerized with P(SSx-co-MAy) via an oxidation reaction to yield a PPMA dispersion. PP was synthesized in the same manner using PSS (Supplementary Fig. 2). Figure 1c demonstrates the large-scale polymerization reaction using a 1-L double-jacketed reactor for producing 750 g conductive polymers. Detailed synthetic procedures are described in the Supplementary Information.

Precursor samples of P(SSx-co-MAy) (PSS and P(SS-co-MA)) with PSS-to-PMA molar ratios of 1:0, 5:1, 2:1, and 1:1 were characterized by complementary analyses. First, the functional groups of PSS and PMA were identified using proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectroscopy, as shown in Fig. 2a. The chemical shifts ranging from 6.1 to 7.8 ppm correspond to the para-substitution on the benzene ring, while those between 2.3 and 2.9 ppm are attributed to the carboxylic acid43,44. The detailed information on the synthesized P(SSx-co-MAy) are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Figure 2b presents the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of P(SSx-co-MAy), signifying peaks at 1170 cm−1 for the –SO3 asymmetric stretching vibration and at 1118 and 1000 cm−1 for the –SO3 symmetric stretching vibration. These peaks were present in the spectra of PSS and P(SS-co-MA), confirming the presence of –SO3 groups in both compounds. In addition, the peaks at 1710 cm−1, assigned to the C = O stretching vibration, indicate the carboxyl group in P(SS-co-MA). The average molecular weights are provided in Supplementary Fig. 3. Overall, these results confirm the successful syntheses of P(SSx-co-MAy). Subsequently, these materials were reacted with the EDOT monomer, creating the e−-conductive polymers of PPMA or PP. Depending on the PSS-to-PMA molar ratio, the final product samples were named: PEDOT:PSS (PP), PEDOT:P(SS5-co-MA1) (PPMA51), PEDOT:P(SS2-co-MA1) (PPMA21), and PEDOT:P(SS1-co-MA1) (PPMA11). Large-scale production (1 L) and the synthesized solutions are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 4.

a, b Molecular structure and 1H-NMR spectra (a), and FTIR spectra of P(SSx-co-MAy) (b). c, d 2D GIWAX patterns of PP and PPMAs films (c) and their corresponding out-of-plane intensity profiles (d). e Cyclic voltammograms between 0.01 and 1.00 V (vs. Li/Li+) at 0.1 mV s−1 and 30 °C. f e− conductivities before and after the CV measurements in LE and SE cells. g Ex situ S 2p XPS spectra before and after the CV measurements from the same electrodes as in Fig. 2c.

To obtain detailed structural information of the PEDOT chain packing in PP and PPMA, grazing-incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering (GIWAXS) measurements were conducted for the polymer film. This well-established protocol can analyze the inter- and intrachain correlation of polymers on the surface and basal layers of PP and PPMAs45,46. Figure 2c shows typical 2D GIWAXS patterns of the PP and PPMA films. To interpret the structural changes, the scattering intensities were scanned along the out-of-plane direction, as illustrated in Fig. 2d. Four characteristic peaks at q = 0.31 Å−1 (d = 20.27 Å calculated with d = 2π/q), 0.62 Å−1 (d = 10.13 Å), 1.26 Å−1 (d = 4.99 Å), and 1.77 Å−1 (d = 3.55 Å) are attributed to the two different types of alternating stacking arrangements of PEDOT, the amorphous halo of PSS, and the π–π stacking of PEDOT, respectively, which were common in both PP and PPMA films47,48. Thus, we concluded that PPMAs have the same characteristics in terms of the molecular arrangement and π–π stacking of PEDOT as well-known PP. A more detailed discussion is available in the Supplementary Information. Because these materials were intended for use in Si electrodes, the polymer samples were cast onto a Cu current collector and subjected to atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements to check for phase separation according to the PMA ratio (Supplementary Fig. 5). Consequently, no distinct difference in surface roughness between Cu and PP was observed, and no phase separation was detected.

The electrochemical stability of PP and PPMAs was assessed via cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests using (Li-In) | LPSCl | Ti | (polymer film (38 µm)) cells between 0.01 and 1.00 V (vs. Li/Li+) at 0.1 mV s−1 and 30 °C. The corresponding CV curves in Fig. 2e exhibited irreversible cathodic peaks in the first cycle, prompting further electrochemical analysis using e⁻-conductive binder films. Moreover, given that PEDOT:PSS is known to be electrochemically stable within the 2.5–4.0 V (vs. Li/Li⁺) range but unstable at negative electrode potentials49, we systematically assessed the electrochemical stability of e⁻-conductive binder films in both LE and SE systems within the potential window relevant to Si electrodes (Supplementary Notes 2 and Supplementary Figs. 6–15). In LE cells, irreversible reduction peaks were observed below 1.0 V, attributed to reactions with the LEs and solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation. In contrast, SE cells showed lower current responses and distinct electrochemical behaviors, arising from the solid-solid interfacial nature and limited Li⁺ diffusion. Cycling stability also showed a clear contrast: while LE cells showed persistent irreversible reactions (Supplementary Fig. 8), SE cells displayed stabilized current densities and reversible redox behavior after the 5th cycle (Supplementary Fig. 9). Due to the absence of post-treatments for increasing e− conductivity, the pristine PP and PPMA11 films retained a benzoid-dominant structure49,50. Raman spectroscopy confirmed that this structure was well preserved after lithiation and delithiation (Supplementary Fig. 10). Open-circuit voltage (OCV) monitoring revealed Li⁺ doping into the polymer bulk in LE cells, whereas such doping was absent in SE cells, further supporting a reaction mechanism confined to the interface (Supplementary Fig. 11). Consistently, time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOFSIMS) analysis confirmed Li⁺ incorporation in LE cells but not in SE cells, reinforcing the suppression of decomposition in the solid-state system (Supplementary Fig. 12). In line with this, peel-off tests on PPMA11 films revealed a pronounced loss of adhesion after cycling in LE cells, whereas films cycled in SE cells retained comparable adhesion (Supplementary Fig. 13). Collectively, these results highlight the fundamental differences in redox behavior, ion accessibility, structural stability, and adhesion characteristics of PEDOT:PSS-based binders between LE cell and SE cell environments.

In addition, the e− conductivity of PP and PPMA samples were obtained through four-point-probe measurements in LE cells and DC method in SE cells51, and the results are shown in Fig. 2f. For SE cells (referred to as “Binder-SE (ASSB)”), to replicate conditions similar to the binder distribution within a Si electrode, composite electrodes were fabricated by mixing dried e⁻-conductive binder with electronically insulating SEs. This configuration allowed evaluation of e⁻ conductivity trends under conditions with sufficient Li sources. Detailed experimental procedures are provided in the Supplementary Information, Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15. In the pristine films, the highest e− conductivity was observed in PP (10.6 S cm−1), which decreased with increasing PMA content, reaching 5.8 S cm−1 for PPMA11. These values were obtained without the addition of well-known solvents such as ethylene glycol and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), unlike previous reports that used solvents such as DMSO and consequently reported higher values of 450 S cm−1 52,53. The absence of additive solvents in our samples is because of their relevance for ASSB applications. In LE cells (referred to as “Film (LIB)”), the decrease in e⁻ conductivity of the binder films after CV cycling was comparable to that observed in the binder–SE composite in SE cells (Fig. 2f). Accordingly, the e⁻ conductivity of the binder itself within the Si electrode in ASSB cells is estimated to fall within the range of 10⁻1 to 10⁻2 S cm⁻1. Given the insulating property of Si particles at pristine state (with a measured e− conductivities of ≈10−6 S cm−1, Supplementary Fig. 16), the e− conductivity values of PP and PPMA in this study are sufficiently high to serve as effective electrical wiring for insulating Si particles within electrodes for ASSB cells. The preserved e⁻ conductivity of the e⁻-conductive binder was further confirmed by the CV and e⁻ conductivity measurements of Si/e⁻-conductive binder composite electrodes before and after cycling (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Owing to its insoluble yet dispersive nature in slurry processing solvents, the PPMA binder is primarily located in the interstitial voids between Si particles rather than forming conformal coatings, allowing interparticle contact and promoting monolithic structural evolution. This distribution preserves Li⁺ diffusion pathways even under low operating pressure. Effective Li+ conductivity (σion-eff) measurements of lithiated Si/PVDF and Si/PPMA11 electrodes in (Li-In) | SE | Si | SE | (Li-In) symmetric cells revealed that Si/PPMA11 electrodes exhibited conductivity comparable to Si/PVDF (7.4 vs. 25.5 mS cm−1) (Supplementary Fig. 18), confirming that Li⁺ transport is not severely hindered by the binder.

In Fig. 2e, the higher the PMA content, the larger the cathodic peak, indicating that protons in the carboxyl group (–COOH) were replaced by Li+, as evidenced by the evolution of the Li 1 s X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) peak from the corresponding cycled electrode (Supplementary Fig. 19)54,55. When the potential was scanned back towards the positive up to 1 V, the absence of anodic currents suggests that the reaction is irreversible. However, an ex situ XPS analysis of the polymer film samples after the CV tests revealed only marginal changes compared with the spectra of pristine samples, specifically in the S 2p3/2 peaks for PSS and PEDOT at 168 and 164 eV, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2g. These results indicate the intactness of the backbone structures of these e⁻-conductive polymers, consistent with the Raman results shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. The XPS fitting details of the pristine states of samples are shown in Supplementary Fig. 20. Consistently, the decreases in e− conductivity after the CV tests were only approximately an order of magnitude. These results confirm the electrochemical stability of PP and PPMA.

Effects of e−-conductive binder PPMA vs. PVDF on Si electrodes

Figure 3a, b compare the electrochemical performance of Si electrodes in (Li-In) | LPSCl | Si half cells at 0.2 C (0.84 mA cm−2), 30 °C, and 5 MPa, using different binders–PPMA (PPMA11) and PVDF. The electrodes were fabricated without incorporating carbon additives, with Si/binder compositions of 90:10 and 97:3, respectively. PPMA11 was used as an e−-conductive binder and is referred to simply as PPMA in this section. At the beginning of lithiation, Si electrodes with PVDF exhibited a sharp potential drop far below 0 V (vs. Li/Li+), indicating a large overpotential. By contrast, this pronounced overpotential was absent in the electrodes with PPMA, which exhibited a smooth lithiation voltage profile. This observation suggests that the e− conductivity of PPMA contributes to the observed behavior. Correspondingly, the initial delithiation capacity for electrodes using PPMA was higher (2380 mAh g−1) compared to those using PVDF (2010 mAh g−1). Moreover, electrodes using PPMA demonstrated superior capacity retention over those using PVDF (80 vs. 45% after 50 cycles, Fig. 3b).

a, b Initial lithiation–delithiation voltage profiles (a) and corresponding cycling performance at 0.2 C (1 C = 3500 mA g-1) (b). c Schematic of the ex situ e− conductivity measurement setup. d, e Initial lithiation–delithiation voltage profiles at 0.05 C (1 C = 3500 mA g−1) with relaxation time measured every 350 mAh g−1 (d) and corresponding e− conductivity plots (e). A schematic of the microstructural changes in Si electrodes is shown in the inset of (e).

The changes in e− conductivity within the electrodes during initial lithiation and delithiation were traced by ex situ measurements using custom-made three-electrode cells56,57, with the results presented in Fig. 3c–e. Specifically, constant currents were applied until a capacity of 350 mAh g−1 was reached, followed by resting for 2 h in a repeated cycle. In between these cycles, e− conductivity measurements were conducted ex situ by applying a potential step between the current collector of Si electrodes at the top and a Ni mesh placed between the Si electrodes and separating SE layer. The corresponding voltage profiles are presented in Fig. 3d. Before cycling, Si electrodes with PVDF exhibited an insulating property with an e− conductivity of 5.5 × 10−9 S cm−1 (Fig. 3e). By contrast, Si electrodes with PPMA demonstrated over a 36,000-fold increase in e− conductivity (2.0 × 10−4 S cm−1), suggesting effective electrical wiring of Si particles with PPMA. However, as lithiation began, both electrodes with PVDF and PPMA exhibited rapid increases in e− conductivity, reaching similar values of over 2.0 × 10−3 S cm−1, with the PPMA electrodes displaying slightly higher conductivities. These observations are attributed to the formation of lithiated Si phases, which possess e−-conducting properties and merge to form a monolith58. The initial large overpotential with the sharp potential drop observed in Si/PVDF electrodes is thus explained by the drastic transition from an insulating to an e−-conductive phase (Fig. 3a). However, a distinct difference in e− conductivity was observed during delithiation. While electrodes with PVDF exhibited a sharp decline in e− conductivity, from 2.0 × 10−3 to 4.3 × 10−5 S cm−1, the electrodes with PPMA maintained their conductivity, exhibiting a marginal decrease towards the very end (Fig. 3e). The delithiation induces volume shrinkage of Si, which opposes monolith formation. Under a low operating pressure of 5 MPa, this process causes degraded contacts within the electrodes due to the formation of voids and cracks, as demonstrated in the top-view and cross-section-view scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of pristine and cycled Si/PVDF and Si/PPMA electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 21). While PPMA cannot fully suppress the intrinsic >300% volume change of Si, it provides mechanically robust interparticle cohesion and stable e⁻-conductive pathways that mitigate electrical degradation. After delithiation, PVDF electrodes exhibited delamination at both the SE and current collector interfaces, whereas no such interfacial separation was observed in PPMA electrodes.

Effects of the PMA fraction in PPMA on performance

In the design of PPMA, despite the slight decrease in e− conductivity, the incorporation of PMA enhances the binding ability, helping to maintain contact between Si particles that undergo severe volume changes during cycling. Thus, the effects of the PMA fraction in PPMA on the performance of Si electrodes were thoroughly investigated.

Prior to electrode-level evaluation, the intrinsic mechanical properties of PP, PPMA51, PPMA21, and PPMA11 were assessed by nanoindentation (Supplementary Fig. 22), revealing hardness and Young’s modulus values comparable to those of conventional binders such as PVDF and polyacrylic acid (PAA). The physical properties of the Si electrodes with different PMA fractions were evaluated using 180° peel-off tests, with the results summarized in Supplementary Fig. 23. The peeling force with PP was approximately 1 N cm−1, resulting in complete exposure of the Cu current collector. Si electrodes employing PMA-incorporated binder PPMA51 exhibited a higher peeling force of 1.5 N cm−1. When the PMA fraction was further increased to PPMA11, the peeling force increased to 2.2 N cm−1. By contrast, the Si/PVDF electrode showed a very low peeling force ( < 0.1 N cm−1), falling below commercial standards33.

The Si electrodes with four different binders, PP and PPMA (PPMA51, PPMA21, and PPMA11), were prepared with binder weight fractions of 5%, 10%, and 15%, resulting in a total of twelve electrodes. The sheet resistance of the Si electrodes was measured using four-point probe measurements, and the results are plotted in Supplementary Fig. 24. The results indicate decreases in sheet resistance as the binder weight fraction increased, especially at 10 wt% (e.g., from 1420 kΩ sq−1 at 5 wt% to 110 kΩ sq−1 at 10 wt% for PPMA11). These electrodes were also subjected to electrochemical tests using (Li-In) | LPSCl | Si half cells at 0.2 C, 30 °C, and 5 MPa, and the results are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 25. The corresponding first delithiation capacity and initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE) results are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 26. The optimal performance was achieved with the electrodes containing 10 wt% binder, yielding a highest delithiation capacity of 2380 mAh g−1 for PPMA11. The initial voltage profiles of Si electrodes with the four different e−-conductive binders (10 wt%) and corresponding long-term cycling performances with CEs are shown in Fig. 4a, b. The corresponding rate capabilities were comparable (Supplementary Fig. 27). Si electrodes with a higher fraction of PMA, specifically PPMA11 and PPMA21, showed more stable capacity retention compared with those with PP or PPMA51 (Fig. 4b). Given that the sheet resistance of PPMA11 (110 kΩ sq−1) was much higher compared to those of other samples (e.g., 15 kΩ sq−1 for PP), its better electrochemical performance indicates that this level of e− conductivity (or sheet resistance) is sufficient and highlights the significance of its binding ability beyond just the e−-conductive property. Furthermore, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 28, the Si/PPMA11 (90:10) electrodes showed better performance than Si/PAA electrodes—which also contain the same carboxylic acid group—owing to its e⁻ conductivity, underscoring the combined importance of binding ability and electronic pathways.

a, b Initial lithiation–delithiation voltage profiles (a) and corresponding cycling performances (b) in the potential range of 0.01–1.00 V (vs Li/Li+). c, d Nyquist plots after first and 50th cycles (c) and corresponding Rbulk and Rint values (d). Bar tops indicate the data values. e Top-view SEM images of Si electrodes after 50 cycles. Ex situ characterizations were performed under the same conditions as the cycling tests (c–e).

Figure 4c shows the Nyquist plots of the cells after the first and 50th cycles, signifying depressed semicircles at high frequency, followed by low-frequency constant-phase behavior. These spectra were fitted using the equivalent circuit model shown in Supplementary Fig. 29, with the corresponding fitted results plotted in Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table 2. Specifically, Rbulk, corresponding to the intercept value on the x axis at high frequency, represents the bulk SE resistance, while Rint, corresponding to the amplitude of the semicircle, represents the interface resistance, particularly at the SE-electrode interfaces28,34, and potentially involving electrical connectivity within the electrodes. Rbulk showed minimal differences between samples and only small changes after 50 cycles. However, Rint increased substantially after cycling, especially in the PP and PPMA51 samples that include no or smaller amounts of PMA. The carboxyl groups of PMA improved binding within the electrodes through interactions with the –Si–OH silanol groups. In this regard, the mitigated increases in Rint after 50 cycles for PPMA21 and PPMA11 (19.6 and 17.5 Ω, respectively) compared with those for PP and PPMA51 (29.6 and 34.4 Ω, respectively) are attributed to the adhesive silanol groups that can withstand mechanical stresses caused by the repeated volume changes of Si particles.

Following the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements conducted on the electrodes after 50 cycles, the surface morphology of the electrodes was investigated using SEM. Their top-view images are presented in Fig. 4e. Pronounced cracks were observed in samples with PP or PPMA51, which aligns with the higher increase in Rint. Consistently, ex situ e− conductivity results for the electrodes with PP demonstrated a gradual decrease in e− conductivity during delithiation, in contrast to the results for PPMA11 (Supplementary Fig. 30). These findings indicate that the reinforced binding properties, enabled by the incorporation of PMA, counteract the volume-change-induced contact disruption, thereby maintaining e− connectivity within electrodes. A control experiment revealed that Si electrodes with a simple blended mixture of individual PP and PMA binders resulted in much poorer electrochemical performance compared with those using the copolymer PPMA11 (Supplementary Fig. 31). Specifically, the electrodes with the PP/PMA mixture binder exhibited distinct phase segregation in the SEM images and corresponding energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDXS) elemental maps, accounting for the corresponding poorer performance. In addition, when the electrochemical performance of Si electrodes with PPMA11 (Si/PPMA11 in a weight ratio of 90:10) was compared with those utilizing PVDF and C (Si/PVDF/C (Super C65) in a weight ratio of 90:5:5), the latter showed far inferior performance, as presented in Supplementary Fig. 32. These results emphasize the importance of a uniform distribution of binding and e−-conductive components at the nanoscale, which was achieved via copolymerization.

Si || LiNi0.70Co0.15Mn0.15O2 full cells

The potential of Si electrodes with PPMA11 was evaluated using Si || NCM all-solid-state full cells with NCM and Si mass loadings of 11.0 and 1.2 mg cm−2, respectively. The areal capacity balance of negative-to-positive electrodes (np balances) was 1.6, which was designed to utilize 63% of the full charge (lithiation) capacity of the Si negative electrodes, based on the results obtained from (Li-In) || NCM (Supplementary Fig. 33) and (Li-In) || Si half cells. The initial lithiation–delithiation voltage profiles of Si electrodes with PPMA11 in (Li-In) || Si half cells, partially lithiated to 63% state-of-charge (SOC) to simulate the Si electrodes in Si || NCM full cells, are shown in Supplementary Fig. 34, indicating an ICE of 69%. These profiles are compared with those of NCM electrodes in (Li-In) || NCM half cells, which exhibited an ICE of 82%. These results indicate that the end of discharge in Si || NCM full cells is determined by the termination from Si negative electrodes.

The Si || NCM full cells utilizing Si electrodes with PVDF or PPMA11 were cycled in the voltage range of 2.00–4.29 V at 30 °C and 5 MPa. The corresponding initial charge–discharge voltage profiles and cycling performances are presented in Fig. 5a and b. At a low C rate of 0.05 C, the discharge capacities and ICEs were almost identical for both cells: 158 mAh gNCM−1 with 72% for PPMA11 vs. 157 mAh gNCM−1 with 73% for PVDF. However, the rate capability tests in Fig. 5c show a marked performance advantage for the PPMA11 electrodes over their PVDF counterparts. For example, at the first cycle at 0.5 C during the cycling test (Fig. 5b), the cells with PPMA11 exhibited a much higher capacity compared to those with PVDF: 105 vs. 76 mAh gNCM−1, respectively (Fig. 5d). Notably, under an excessively high operating pressure of 70 MPa, the discharge capacity difference became nullified, even showing an opposite trend: 131 vs. 142 mAh gNCM−1 for PPMA11 and PVDF, respectively. The corresponding voltage profiles and cycling performance data compared to those at 5 MPa are shown in Supplementary Fig. 35. The contrasting performances between PPMA11 and PVDF, distinct under the lowered operating pressure at the high C-rate, highlight the beneficial effect of the e−-conductive binders for the practically relevant operating conditions of ASSBs.

a–c Initial charge–discharge voltage profiles at 0.05 C (1 C = 196 mA g−1) for using PVDF or PPMA11 between 2.0 and 4.29 V (a), corresponding cycling performances (b) and rate capability (c). d, Discharge capacities at 70 MPa and 5 MPa at 0.5 C (1 C = 196 mA g-1). e Initial charge–discharge voltage profiles of prelithiated Si electrodes (PreLi-Si) using PPMA11 between 2.0 and 4.25 V compared with those of pristine Si electrodes using PPMA11. f Cycling performance of PreLi-Si/PPMA11 electrodes at 5 MPa compared with that of Si/PVDF electrodes at 70 MPa. g Comparison of performance based on capacity as a function of C rate normalized by operating pressure (benchmarking parameters in Supplementary Table 3). h–l, Cross-sectional SEM image (h), corresponding photograph of a 233 mAh (Si/PPMA11) || NCM83 pouch cell (i), initial charge–discharge voltage profiles (j), and cycling performance at 0.2 C (1 C = 200 mA g−1) (k). l Comparison of cycling performance with pouch-type Si ASSBs (benchmarking parameters in Supplementary Table 6).

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 36, long-term full-cell cycling revealed that PVDF-based electrodes suffered from increasing overpotential, attributed to e⁻ pathway disruption caused by the volume changes of Si. In contrast, PPMA11 electrodes maintained a more stable voltage profile, reflecting improved mechanical integrity. A comparison between 70 MPa and 5 MPa stack pressures confirmed that the observed overpotential behavior is predominantly governed by external pressure, rather than intrinsic instability of the PPMA11 binder. To further elucidate the electrochemical and mechanical advantages of PPMA11 as a binder for Si electrodes, operando electrochemical pressiometry (OEP) measurements were performed33. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 37, PPMA11 electrodes exhibited more consistent pressure responses than PVDF electrodes, particularly under 0.3 C cycling. Notably, despite delivering higher capacity, PPMA11 maintained a stable pressure baseline, suggesting more reversible electrochemo-mechanical features and, correspondingly more uniform electrochemical reactions. These findings highlight the role of PMA-containing binders in mitigating SOC inhomogeneity by sustaining stable e⁻ conductivity under low-operating pressure, as further supported by Supplementary Fig. 33, which shows negligible differences between 70 MPa and 5 MPa.

In addition to utilizing the e−-conductive binders, prelithiation was applied to Si electrodes to further enhance cycling retention33,59. This approach serves two purposes. First, it provides an excess Li reservoir to counteract Li loss during each cycle. Second, maintaining lithiated phases even at the end of discharge ensures high Li+ diffusivity, e− conductivity, and mechanical ductility. Prelithiation of the Si electrodes with PPMA11 was conducted through Li metal deposition using a thermal evaporation process33. The thickness of the deposited Li metal on the Si electrodes was 4.0 µm, corresponding to ≈23% SOC of Si. The 7Li magic angle spinning NMR (MAS-NMR) results confirmed a spontaneous alloying reaction between Si and the deposited Li, forming lithiated phases (Supplementary Fig. 38). Figure 5e shows a comparison of the initial charge–discharge voltage profiles for Si electrodes utilizing PPMA11, both with and without prelithiation, in Si || NCM full cells at 30 °C and 5 MPa in the voltage range of 2.0–4.25 V. The prelithiated Si electrodes with PPMA11 are denoted as “PreLi-Si”. The initial lithiation–delithiation voltage profiles of Si and PreLi-Si half cells at 0.1 C, along with their corresponding half cell simulations, are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 39a. Specifically, the ICE increased from 66% to 79% after prelithiation (Supplementary Fig. 39b). Consequently, the full cell results in Fig. 5e showed an increase in ICE from 73% to 83%, with a corresponding increase in capacity from 157 to 179 mAh gNCM−1. Moreover, the cycling retention of full cells was enhanced: from 72% to 86% after 100 cycles, compared to cells without prelithiation (Fig. 5f). The performance for PreLi-Si with PPMA11 achieved at 5 MPa was comparable to that for Si with PVDF obtained under the conventional excessive operating pressure of 70 MPa. Moreover, PreLi-Si with PVDF exhibited substantially poorer cycling performance compared with PPMA11-based PreLi-Si (Supplementary Fig. 40). These result highlights the synergistic role of the e−-conductive binder and prelithiation. Furthermore, plotting the capacity as a function of C rate normalized by operating pressure (i.e., C-rate/operating pressure) demonstrates that cells with Si/PPMA11 electrodes deliver capacities comparable to previous reports (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Table 3)18,20,29,33,34,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66, highlighting the enhanced rate capability achieved at low pressures.

Finally, to assess the practical adaptability of Si electrodes with PPMA11, 233 mAh pouch-type (Si/PPMA) | LPSCl | NCM83 ASSBs were fabricated and tested at 0.05 C, 30 °C, and 5 MPa. The results are shown in Fig. 5h–l. The pouch cells were assembled with a high-capacity NCM83 positive electrode (16.5 mg cm−2, 7 × 10 cm2), LPSCl membrane, and Si negative electrode using PPMA11. The compact microstructures of the sequentially stacked positive electrode (62 μm) | LPSCl (38 μm) | negative electrode (8 μm) within the full cells are visualized by a cross-sectional SEM image and photograph in Fig. 5h, i. The initial charge–discharge voltage profiles at 0.05 C are shown in Fig. 5j, revealing a charge and discharge capacity of 297 and 233 mAh (256 and 201 mAh gNCM83−1), with an ICE of 78.3% and an average cell voltage of 3.43 V. The higher specific capacity of pouch-type cells compared with those of pellet-type cells come from the higher capacity of NCM83 than that of NCM70, as detailed in in Supplementary Figs. 41-43 and Supplementary Table 4. The cycling performance with CE for the pouch-type cells at 0.77 mA cm−2 (0.2 C), after the 0.19 mA cm−2 (0.05 C) formation cycle, is displayed in Fig. 5k. It exhibits an improved capacity retention at 0.2 C. The achieved capacity values translated into specific energy and volumetric energy densities of 226 Wh kg−1 and 792 Wh L−1, respectively, calculated by including inactive components (current collectors) and using a total stack thickness of 141 µm with an areal mass of 49.3 mg cm⁻2 (see Supplementary Table 5 for details). These figures are nearly on par with those of the state-of-the-art anode-less pouch cell utilizing a C-Ag interlayer67, demonstrating the high competitiveness of cells with Si/PPMA11 electrodes for high-energy ASSB applications68. Furthermore, compared to previously reported pouch-type Si ASSBs, our results demonstrate enhanced capacity (mAh) and cyclability, even with the thinner SE membrane and without the use of prelithiation, as shown in Fig. 5l and Supplementary Table 628,65,66,69,70,71,72,73.

Discussion

The binders PPMA, which offer both e−-conducting and binding properties, as well as eco-friendliness, can address the chronic issues in Si electrodes in ASSBs operating at low pressures, while also eliminating the need for carbon additives. Along with its scalable synthesis, the sufficiently high e− conductivities and electrochemical stability of PPMA were successfully validated in ASSBs, enabling performance not attainable in LE systems due to its limited electrochemical stability therein. The electrochemo-mechanical degradation modes of Si electrodes in ASSBs at low operating pressures, specifically the degradation in e− connectivity within electrodes during delithiation, were identified through ex situ e− conductivity measurements using three-electrode cells. This degradation was substantially mitigated by the application of PPMA. Furthermore, the adhesive role of PMA in PPMA to reinforce the mechanical integrity of Si electrodes was found to further enhance the electrochemical performance. Using the optimized PPMA binders, Si || NCM ASSB full cells at 5 MPa showed better performance than those using the conventional PVDF binder both in capacity and cycling retention (105 vs. 76 mAh gNCM−1 at 0.5 C). In addition, the synergistic application of prelithiation resulted in further improved performances: 179 mAh gNCM−1 at 0.05 C and 134 mAh gNCM−1 at 0.5 C with 72% capacity retention after 200 cycles, which is comparable with current state-of-the-art. Finally, a 233 mAh pouch-type Si || NCM83 ASSB with specific and volumetric energy densities of 226 Wh kg−1 and 792 Wh L−1 was demonstrated. We believe that our findings on the degradation/enhancement mechanisms of Si electrodes in ASSBs and the established design principles for advanced binders provide invaluable guidance for the development of high-energy ASSB technologies on a practical scale.

Methods

Preparation of materials

Si powders with a size of 1–5 µm (99.9% metal basis) were purchased from Alfa Aesar. PVDF binders obtained from Arkema (KUREHA CORPORATION, KF9300) were used. Argyrodite LPSCl powders, obtained from POSCO JK Solid Solution (South Korea), were used, exhibiting a Li+ conductivity of 4.2 mS cm−1 at 30 °C, which was determined using the alternating current (AC) method with Ti | SE | Ti symmetric cells. The NCM70 powders (Landf Ltd., South Korea) were coated with 1.4 wt% LiNbO3 using a wet-chemical method employing lithium ethoxide (99.95%, Sigma Aldrich) and niobium ethoxide (99.95%, Sigma Aldrich), as described in a previous study74. Conductive carbon additives (Super C65) were purchased from TIMCAL Ltd. The Li metal rod with a diameter of 3 mm (99.9% metal basis) used for prelithiation through thermal evaporation was purchased from Alfa Aesar. The detailed synthesis procedures of PSS, PEDOT:PSS, P(SSx-co-MAy), and PEDOT:P(SSx-co-MAy) are described in Supplementary Information.

Fabrication of electrodes

The Si electrodes with e−-conductive binders were prepared by mixing Si powders and PP or PPMA without conductive carbon additives in a certain ratio using deionized water as a processing solvent. The slurries were cast onto a Cu foil (18 μm) and dried in a vacuum oven at 80 °C. The Si electrodes with conventional PVDF were prepared by mixing Si powders and PVDF at a target ratio using NMP (anhydrous 99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich) as a processing solvent. All Si electrodes targeted a loading of 1.2–1.3 mg cm⁻2. Detailed information on the electrodes is provided in Supplementary Table S7. For the prelithiation of Si electrodes, Li metal was deposited to the Si electrodes using a thermal evaporator (WOOSUNG HI-VAC Co.) housed in an Ar-filled glove box. A piece of solid Li was placed inside a Ta boat within the evaporator. To prepare Li0.5In-SE counter electrodes, Li0.5In (nominal composition) powders were initially produced by blending Li powders (FMC Lithium Corp.) and In powders (Aldrich, 99%) using vortex mixer for 15 s. Subsequently, these Li0.5In powders were blended with LPSCl powders in a THINKY mixer with a single ZrO₂ ball for 20 s, repeated three times at 25 °C in an Ar-filled glove box. To prepare composite positive electrodes for pellet-type cells, NCM, LPSCl, and super C65 were mixed in a weight ratio of 70:30:3 using a mortar and pestle. The NCM70 and NCM83 sheet-type electrodes (SK On Ltd., South Korea) were fabricated using a wet slurry method, where a slurry consisting of NCM, LPSCl, binder, and super C65, in a weight ratio of 75.0:22.0:1.5:1.5 and 80:18:1:1 with benzyl acetate as the processing solvent, was cast onto Al foil (15 μm) and subsequently dried under vacuum at 80 °C. Powder-type NCM70 electrodes were prepared with a target areal loading of 11 mg cm⁻2. Sheet-type NCM70 and NCM83 electrodes were prepared with target areal loadings of 14 and 16 mg cm⁻2, respectively. Similarly, the LPSCl membrane was fabricated using a wet slurry method, with a composition of LPSCl and binder in a weight ratio of 97:3 with p-xylene and butyl butyrate as the processing solvent. All sheet-type electrodes were coated on one side.

Material characterization

The GIWAXS experiments were conducted at beamline 9 A at the Pohang Accelerator Research Center in Korea. The operating conditions were set to a wavelength of λ = 1.240 Å, a sample-detector distance of 0.2 m, an exposure time of 1–10 s, and an incident angle of 0.120°. The scattering intensity data were collected using a 2D detector (MX 170HS, Rayonix Ltd.) located at the end of a vacuum guide tube. 1H-NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III HD 300 spectrometer operating in a polymer solution in D2O. Chemical shifts are expressed in parts per million (ppm) on the δ scale. Then, 7Li magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance spectra were obtained at room temperature on a 400 MHz Advance II+ system (Bruker Solid-state NMR) at the Korea Basic Science Institute (KBSI) Seoul Western Center. LixSi specimens were stored and transported using an airtight capsule in an Ar-filled glove box to prevent exposure to ambient air. FTIR spectra were recorded using a Bruker ALPHA 2 spectrophotometer using the KBr pellet method. The Raman spectra were acquired using an Alpha300R confocal Raman microscope with a 532 nm excitation wavelength (power = 1.0 mW). A 100× objective lens with a 10 s acquisition time was used for data collection. TOFSIMS was performed on a TOF SIMS 5 (ION-TOF GmbH, Münster, Germany). A pulsed 30 keV Bi⁺ primary ion beam was used for analysis, and sputtering was conducted under the same beam conditions. Images were collected from 10 × 10 µm2 areas for the PP and PPMA samples. The base pressure in the analysis chamber was <5.0 × 10⁻10 Pa throughout. Samples were transferred from an Ar-filled glovebox to the instrument using an airtight shuttle to avoid ambient exposure. Samples were transferred from an Ar-filled glovebox to the instrument using an airtight shuttle to avoid air exposure. Electrode adhesion was quantified by a 180° peel test on a multi-axis micro-texture analyzer (TXA Texture Analyzer, YEONJIN S-Tech) at a peel rate of 0.5 mm s⁻1. Adhesive tape was pressed onto each electrode with a 2 kg hand roller to ensure uniform contact. The peeling force was averaged from just after the first maximum to a displacement of 30 mm. Cross-sectional SEM specimens were prepared by cold polishing at 6.0 kV for 6 h, followed by 1.5 kV fine milling for 1 h at –50 °C (JEOL IB19510CP). SEM images and corresponding EDXS maps were acquired on an AURIGA scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss). SEM imaging used a beam current of 2 nA with accelerating voltages of 3 or 10 kV; EDXS spectra were collected at 2 nA and 10 kV. Samples were stored and transferred in an Ar-filled glovebox using an airtight shuttle to prevent air exposure. Ex situ XPS was performed with a monochromatic Al Kα source (1486.6 eV) at 12 kV and 6 mA on a K-Alpha+ instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were mounted in the glovebox and mounted to the XPS chamber without ambient exposure. To remove interfacial byproducts, surfaces were etched at 500 eV for 120 s. The average molecular weight and polydispersity index of the resulting polymers were measured using gel permeation chromatography. The samples were analyzed using an Ultimate 3000 system from Korea (Dionex). The Ultimate 3000 system utilized an Ultrahydrogel column, and the relative molecular weight was determined using specialized GPC software. Standards were assessed using Pullulan (molecular weight = 100,000–800,000).

Electrochemical characterization

CV measurements were conducted within a voltage range of 0.01 to 1.00 V at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1 (for Si/e⁻-conductive binder composite electrode, 0.01 mV s−1). For the liquid-electrolyte cell tests, 2032 coin cells were used. 2320 (Celgard) was used as the separator. 1 M LiPF6 dissolved in ethylene carbonate and dimethyl carbonate in a volume ratio of 1:1 was used as the liquid electrolyte (Panax etec, South Korea) and a volume of 0.5 mL was provided sufficiently. Electrodes were cut using a hand-punching tool (Welcose, South Korea). For LE cells, the counter electrode consisted of 30 μm thick Li metal, while for SE cells, the counter electrode was a Li0.5In-SE composite with a mass loading of 45 mg cm−2. Ex situ e− conductivity measurements were conducted using two channels. On one channel, galvanostatic cycling was applied between the working electrode (WE, Si electrode) and counter electrodes (CtE, Li-In electrode). The electrical conductivity of the WE was measured using a DC method through a separate channel that connects the wire between a Ni mesh, located between the WE and the SE layers, to the WE. After galvanostatic cycling, followed by a relaxation time of 1 h, DC conductivity measurements were performed by applying a 0.1 or 0.01 V potential step for 30 min. All-solid-state cells (13 mm diameter) used Ti rods as current collectors and a polyaryletheretherketone mold. To fabricate (Li–In) || Si half-cells, an LPSCl layer was prepared by pelletizing 150 mg LPSCl to a thickness of ~700 µm under 70 MPa for 3 min using a hydraulic press. Subsequently, a WE (NCM electrode for full cells or Si electrode for half cells, 11 mg cm−2, 55 µm and 1.2 mg cm−2, 8 µm, respectively) was attached to one side of the SE layer (LPSCl), whereas a 200 mg Li0.5In-LPSCl CE (270 µm) was placed on the other side. The entire assembly was pressed at 370 MPa. In both coin cells and all-solid-state cells, a 12.7 mm-diameter electrode was used. The all-solid-state cells were tested at targeted pressures using a pressure sensor (load cell, BONGSHIN). For OEP measurements, a pressure sensor with a resolution of 0.1 kg (load cell, BONGSHIN) was placed in the pressurized cell. Pressure evolution during charge and discharge was recorded with in-house software. The capacity-normalized pressure-change difference, Δ(ΔPQ), was defined as Δ(ΔP)/Qdischarge, where Qdischarge is the discharge capacity in the corresponding cycle. The all-solid-state cells were assembled in an Ar-filled glovebox (MSIT-24-0100) at the Institute for Battery Research Innovation (RS-2023-00261543). For the fabrication of pouch cells, a prepared NCM83 sheet-type positive electrode with transferred LPSCl membrane and Si electrode were stacked in sequence. This assembly was vacuum-sealed in an Al-laminate pouch, then subjected to warm isostatic pressing at 450 MPa and 80 °C for 5 min to complete fabrication. For pouch cells, detailed information (size, composition ratio, and thickness) on the electrodes and separators is provided in Supplementary Table S3 and S4. AC impedance data were collected on a VMP3 (Bio-Logic) in potentiostatic mode with a 14.1 mV sinusoidal perturbation over 7 MHz–10 mHz (10 points per decade and 5 measurements per frequency). For ASSB half cells, spectra were acquired after charging to the terminal potential and resting at open circuit for 1 h at 30 °C. To ensure reproducibility, at least two cells were used in each electrochemical test. Coulombic efficiency (CE) in Si half-cells was calculated for each cycle as the ratio of the charge (delithiation) capacity divided by the discharge (lithiation) capacity.

Synthesis of PSS and P(SS-co-MA)

Styrene sulfonic acid, sodium salt hydrate (NaSS), maleic acid, 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene (EDOT), iron(III) sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3), and sodium persulfate (NaPS) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich and used without further purification. The cation and anion exchange resins were supplied from Samyang Company (South Korea). Free radical polymerization was employed to synthesize PSS. The polymerization process was carried out in a double-jacketed reactor in an aqueous environment. Initially, NaSS monomer (30.000 g, 0.145 mol) was dissolved in 260 mL of deionized water, and this solution was stirred mechanically in the reactor for 30 min. To eliminate any dissolved oxygen, the solution was degassed with N2 gas for 3 h (Step 1 in Fig. 1b). Subsequently, NaPS (650 mg, 2.73 mmol) dissolved in 10 mL deionized water was introduced into the reactor post-degassing (Step 2). The polymerization process unfolded at 80 °C for 20 h under a N2 atmosphere. Post-polymerization, a HCl solution was added to transform PSSNa into acidic PSS by removing Na+ ions. The resulting acidic polymer, PSS, was precipitated in tetrahydrofuran, leading to the formation of a dark yellow powder, which was collected through filtration and dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C overnight. The synthesis of P(SSx-co-MAy) was performed using the free radical polymerization method with the desired ratio of NaSS and MA monomers according to the same synthesis process for the PSS.

Synthesis of PEDOT:PSS and PEDOT:P(SS-co-MA)

In separate reactors, 160 g each of PSS and P(SSx-co-MAy) were dispersed in 600 mL of deionized water and stirred at 150 rpm. The quantities of the PSS and P(SSx-co-MAy) copolymers were adjusted to equal 2.5 mass equivalents of the EDOT monomer. Then, 0.078 g Fe2(SO4)3 and 1.532 g NaPS were sequentially added to the reactor, followed by the introduction of the EDOT monomer to begin the reaction (Step 3). After completing polymerization, the solution underwent ion exchange resin treatment to eliminate residual ions at room temperature. The polymer solution was then sonicated to ensure a well-dispersed polymer solution.

Data availability

All data produced or analyzed in this study are available within this article and its supplementary information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Obrovac, M. N., Christensen, L., Le, D. B. & Dahn, J. R. Alloy Design for Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 154, A849 (2007).

Choi, J. W. & Aurbach, D. Promise and reality of post-lithium-ion batteries with high energy densities. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16013 (2016).

Sun, Y., Liu, N. & Cui, Y. Promises and challenges of nanomaterials for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Nat. Energy 1, 16071 (2016).

Su, X. et al. Silicon-Based Nanomaterials for Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review. Adv. Eng. Mater. 4, 1300882 (2014).

Jin, Y., Zhu, B., Lu, Z., Liu, N. & Zhu, J. Challenges and Recent Progress in the Development of Si Anodes for Lithium-Ion Battery. Adv. Eng. Mater. 7, 1700715 (2017).

Szczech, J. R. & Jin, S. Nanostructured silicon for high capacity lithium battery anodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 56–72 (2011).

Yao, Y., Liu, N., McDowell, M. T., Pasta, M. & Cui, Y. Improving the cycling stability of silicon nanowire anodes with conducting polymer coatings. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 7927–7930 (2012).

Jia, H. et al. High-Performance Silicon Anodes Enabled By Nonflammable Localized High-Concentration Electrolytes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 9, 1900784 (2019).

Kwon, H. J. et al. Nano/Microstructured Silicon–Carbon Hybrid Composite Particles Fabricated with Corn Starch Biowaste as Anode Materials for Li-Ion Batteries. Nano Lett. 20, 625–635 (2020).

Chen, J. et al. Electrolyte design for LiF-rich solid–electrolyte interfaces to enable high-performance microsized alloy anodes for batteries. Nat. Energy 5, 386–397 (2020).

Tian, Y.-F. et al. Tailoring chemical composition of solid electrolyte interphase by selective dissolution for long-life micron-sized silicon anode. Nat. Commun. 14, 7247 (2023).

Cheng, X.-B., Zhang, R., Zhao, C.-Z. & Zhang, Q. Toward Safe Lithium Metal Anode in Rechargeable Batteries: A Review. Chem. Rev. 117, 10403–10473 (2017).

Liu, W., Liu, P. & Mitlin, D. Review of Emerging Concepts in SEI Analysis and Artificial SEI Membranes for Lithium, Sodium, and Potassium Metal Battery Anodes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 10, 2002297 (2020).

He, Y. et al. Progressive growth of the solid–electrolyte interphase towards the Si anode interior causes capacity fading. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1113–1120 (2021).

Huo, H. & Janek, J. Silicon as Emerging Anode in Solid-State Batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 4005–4016 (2022).

Lewis, J. A., Cavallaro, K. A., Liu, Y. & McDowell, M. T. The promise of alloy anodes for solid-state batteries. Joule 6, 1418–1430 (2022).

Lau, J. et al. Sulfide Solid Electrolytes for Lithium Battery Applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 8, 1800933 (2018).

Kim, D. H. et al. Sheet-type Li6PS5Cl-infiltrated Si anodes fabricated by solution process for all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 426, 143–150 (2019).

Cao, D. et al. Unveiling the Mechanical and Electrochemical Evolution of Nanosilicon Composite Anodes in Sulfide-Based All-Solid-State Batteries. Adv. Eng. Mater. 13, 2203969 (2023).

Huang, Y., Shao, B., Wang, Y. & Han, F. Solid-state silicon anode with extremely high initial coulombic efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 1569–1580 (2023).

Sakuda, A., Hayashi, A. & Tatsumisago, M. Sulfide Solid Electrolyte with Favorable Mechanical Property for All-Solid-State Lithium Battery. Sci. Rep. 3, 2261 (2013).

Zhu, Y., He, X. & Mo, Y. First principles study on electrochemical and chemical stability of solid electrolyte–electrode interfaces in all-solid-state Li-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 3253–3266 (2016).

Richards, W. D., Miara, L. J., Wang, Y., Kim, J. C. & Ceder, G. Interface Stability in Solid-State Batteries. Chem. Mater. 28, 266–273 (2016).

Banerjee, A., Wang, X., Fang, C., Wu, E. A. & Meng, Y. S. Interfaces and Interphases in All-Solid-State Batteries with Inorganic Solid Electrolytes. Chem. Rev. 120, 6878–6933 (2020).

Schwietert, T. K. et al. Clarifying the relationship between redox activity and electrochemical stability in solid electrolytes. Nat. Mater. 19, 428–435 (2020).

Liang, Z. et al. Understanding the failure process of sulfide-based all-solid-state lithium batteries via operando nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 14, 259 (2023).

Son, J. P. et al. Five-volt-class high-capacity all-solid-state lithium batteries. Nat. Energy 10, 1334–1346 (2025).

Cangaz, S. et al. Enabling High-Energy Solid-State Batteries with Stable Anode Interphase by the Use of Columnar Silicon Anodes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 10, 2001320 (2020).

Tan, D. H. S. et al. Carbon-free high-loading silicon anodes enabled by sulfide solid electrolytes. Science 373, 1494–1499 (2021).

Yan, W. et al. Hard-carbon-stabilized Li–Si anodes for high-performance all-solid-state Li-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 800–813 (2023).

Ye, L., Lu, Y., Wang, Y., Li, J. & Li, X. Fast cycling of lithium metal in solid-state batteries by constriction-susceptible anode materials. Nat. Mater. 23, 244–251 (2024).

Cao, Q. et al. Stacking pressure homogenizes the electrochemical lithiation reaction of silicon anode in solid-state batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 67, 103246 (2024).

Jun, S. et al. Interlayer Engineering and Prelithiation: Empowering Si Anodes for Low-Pressure-Operating All-Solid-State Batteries. Small 20, 2309437 (2024).

Huo, H. et al. Chemo-mechanical failure mechanisms of the silicon anode in solid-state batteries. Nat. Mater. 23, 543–551 (2024).

Kovalenko, I. et al. A Major Constituent of Brown Algae for Use in High-Capacity Li-Ion Batteries. Science 334, 75–79 (2011).

Wang, C. et al. Self-healing chemistry enables the stable operation of silicon microparticle anodes for high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Chem. 5, 1042–1048 (2013).

Choi, S., Kwon, T. -w, Coskun, A. & Choi, J. W. Highly elastic binders integrating polyrotaxanes for silicon microparticle anodes in lithium ion batteries. Science 357, 279–283 (2017).

Zhu, T. et al. Formation of hierarchically ordered structures in conductive polymers to enhance the performances of lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 129–137 (2023).

Rensmo, A. et al. Lithium-ion battery recycling: a source of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to the environment? Environ. Sci.: Process. Impacts 25, 1015–1030 (2023).

Liu, T. et al. Recycled micro-sized silicon anode for high-voltage lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Sustainability 7, 1057–1066 (2024).

Guelfo, J. L. et al. Lithium-ion battery components are at the nexus of sustainable energy and environmental release of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Nat. Commun. 15, 5548 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Fluorination in advanced battery design. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 119–133 (2024).

Neira-Carrillo, A. et al. Electrospun Poly(acrylic acid-co-4-styrene sulfonate) as Potential Drug-Eluting Scaffolds for Targeted Chemotherapeutic Delivery Systems on Gastric (AGS) and Breast (MDA-Mb-231) Cancer Cell Lines. Nanomaterials 12, 3903 (2022).

Höhne, S. et al. Polyacrylic Acid Copolymers as Adhesion-Adapted Model Materials for Cleaning Tests. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 224, 2200309 (2023).

Müller-Buschbaum, P. The Active Layer Morphology of Organic Solar Cells Probed with Grazing Incidence Scattering Techniques. Adv. Mater. 26, 7692–7709 (2014).

Li, X. et al. Deciphering the superior thermoelectric property of post-treatment-free PEDOT:PSS/IL hybrid by X-ray and neutron scattering characterization. npj Flex. Electron 6, 6 (2022).

Palumbiny, C. M. et al. The Crystallization of PEDOT:PSS Polymeric Electrodes Probed In Situ during Printing. Adv. Mater. 27, 3391–3397 (2015).

Kee, S. et al. Controlling Molecular Ordering in Aqueous Conducting Polymers Using Ionic Liquids. Adv. Mater. 28, 8625–8631 (2016).

Gribble, D. A. et al. Mechanistic Elucidation of Electronically Conductive PEDOT:PSS Tailored Binder for a Potassium-Ion Battery Graphite Anode: Electrochemical, Mechanical, and Thermal Safety Aspects. Adv. Eng. Mater. 12, 2103439 (2022).

Adilbekova, B. et al. Enhancing the Electrical Conductivity and Long-Term Stability of PEDOT:PSS Electrodes through Sequential Treatment with Nitric Acid and Cesium Chloride. Adv. Mater. 36, 2405094 (2024).

Lim, Y.-G. et al. Incorporation of conductive polymer into soft carbon electrodes for lithium ion capacitors. J. Power Sources 299, 49–56 (2015).

Yoo, D., Kim, J. & Kim, J. H. Direct synthesis of highly conductive poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(4-styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS)/graphene composites and their applications in energy harvesting systems. Nano Res 7, 717–730 (2014).

Lee, I., Kim, G. W., Yang, M. & Kim, T.-S. Simultaneously Enhancing the Cohesion and Electrical Conductivity of PEDOT:PSS Conductive Polymer Films using DMSO Additives. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 302–310 (2016).

Hays, K. A. et al. What makes lithium substituted polyacrylic acid a better binder than polyacrylic acid for silicon-graphite composite anodes? J. Power Sources 384, 136–144 (2018).

Nguyen, C. C., Yoon, T., Seo, D. M., Guduru, P. & Lucht, B. L. Systematic Investigation of Binders for Silicon Anodes: Interactions of Binder with Silicon Particles and Electrolytes and Effects of Binders on Solid Electrolyte Interphase Formation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 12211–12220 (2016).

Quemin, E. et al. An Advanced Cell for Measuring In Situ Electronic Conductivity Evolutions in All-Solid-State Battery Composites. Adv. Eng. Mater. 13, 2301105 (2023).

Kim, K. et al. Interfacial Degradation Mechanism of Nanostructured LiCoO2 for Li6PS5Cl-Based All-Solid-State Batteries. Chem. Mater. 36, 5215–5227 (2024).

Pollak, E., Salitra, G., Baranchugov, V. & Aurbach, D. In Situ Conductivity, Impedance Spectroscopy, and Ex Situ Raman Spectra of Amorphous Silicon during the Insertion/Extraction of Lithium. J. Phys. Chem. C. 111, 11437–11444 (2007).

Ham, S.-Y. et al. Overcoming low initial coulombic efficiencies of Si anodes through prelithiation in all-solid-state batteries. Nat. Commun. 15, 2991 (2024).

Cao, D. et al. Long-Cycling Sulfide-Based All-Solid-State Batteries Enabled by Electrochemo-Mechanically Stable Electrodes. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200401 (2022).

Yamamoto, M. et al. Slurry mixing for fabricating silicon-composite electrodes in all-solid-state batteries with high areal capacity and cycling stability. J. Power Sources 402, 506–512 (2018).

Yamamoto, M. et al. Effects of volume variations under different compressive pressures on the performance and microstructure of all-solid-state batteries. J. Power Sources 473, 228595 (2020).

Fan, Z. et al. In-situ prelithiation of electrolyte-free silicon anode for sulfide all-solid-state batteries. eTransportation 18, 100277 (2023).

Zhou, L. et al. Li3–xZrx(Ho/Lu)1–xCl6 Solid Electrolytes Enable Ultrahigh-Loading Solid-State Batteries with a Prelithiated Si Anode. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 3102–3111 (2023).

Chen, Y.-T. et al. Enabling Uniform and Accurate Control of Cycling Pressure for All-Solid-State Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2304327 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Large-Scale Fabrication of Stable Silicon Anode in Air for Sulfide Solid State Batteries via Ionic-Electronic Dual Conductive Binder. Adv. Mater. 36, 2405025 (2024).

Lee, Y.-G. et al. High-energy long-cycling all-solid-state lithium metal batteries enabled by silver–carbon composite anodes. Nat. Energy 5, 299–308 (2020).

Wang, C., Kim, J. T., Wang, C. & Sun, X. Progress and Prospects of Inorganic Solid-State Electrolyte-Based All-Solid-State Pouch Cells. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209074 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. A High-Capacity Polyethylene Oxide-Based All-Solid-State Battery Using a Metal–Organic Framework Hosted Silicon Anode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 24798–24805 (2022).

Grandjean, M. et al. Low pressure cycling of solid state Li-ion pouch cells based on NMC – Sulfide – Nanosilicon chemistry. J. Power Sources 585, 233646 (2023).

Jing, S. et al. High-Performance Sheet-Type Sulfide All-Solid-State Batteries Enabled by Dual-Function Li4.4Si Alloy-Modified Nano Silicon Anodes. Adv. Mater. 36, 2312305 (2024).

Pan, H. et al. A solid-state lithium-ion battery with micron-sized silicon anode operating free from external pressure. Nat. Commun. 15, 2263 (2024).

Qin, X. et al. Self-pressure silicon–carbon anodes for low-external-pressure solid-state Li-ion batteries. ACS Nano 19, 17760–17773 (2025).

Ohta, N. et al. LiNbO3-coated LiCoO2 as cathode material for all solid-state lithium secondary batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 9, 1486–1490 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00343349 and RS-2025-25441254 to Y.S.J.), by the technology innovation program (No. RS-2024-00404166 to J.K.) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea), Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) grant funded by the Korea Government (MOTIE) (RS-2024-00420590, HRD Program for Industrial Innovation) (to J.K. and Y.S.J.), and by SK On (to J.K. and Y.S.J.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Jun and Y.S.J. conceived the concept and designed the experiments. J.K. and Y.S.J. supervised the work. M.J., S.Jung, and J.P. performed the syntheses and characterization of materials. S.Jun, B.J., Y.J.P., and Y.B.S. carried out the electrochemical characterization. S.Jo and D.Y.R. performed the synchrotron X-ray characterization. H.K., S.K., and J.L. fabricated and tested pouch cells. Y.S.J., S.Jun, J.K., and M.J. wrote the manuscript with discussion from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Pascale Chenevier, Mengjin Jiang who co-reviewed with Yuanyuan Yu and the other anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jun, S., Jeong, M., Jang, B. et al. Electron-conductive binder for silicon negative electrode enabling low-pressure all-solid-state batteries. Nat Commun 17, 156 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66851-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66851-0