Abstract

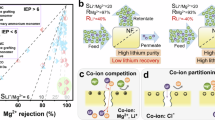

Nanofiltration (NF) membranes with high Li+/X2+ (Co2+, Mn2+, etc.) selectivity are crucial for cost-effective Li+ recovery, addressing the global lithium shortage. However, conventional positively charged NF membranes typically exhibit Janus structure, conferring low Li+ penetration and permeability, and are negatively affected by the electrostatic shielding effects. Inspired by the internal electrical structure of dust storms, where positive-negative mosaic-like charge structure generates strong electric fields to facilitate particle transport, this study proposes a discrete micro-nano isolated island strategy to regulate the charge distribution within the NF membrane. A quaternary ammonium electrolyte was designed to modify the NF membrane, enabling the development of anti-Janus membranes with mosaic-like charge structure. The resulting anti-Janus membranes demonstrated an exceptional Li+/X2+ selectivity, exceeding that of conventional PIP-TMC membranes by 647%-904%, with Li+ penetration at 84.99% and permeability at 20.72 LMH/bar. Furthermore, this study introduces an evaluation metric, Critical Efficiency Product (CEP), for specifically assessing Li⁺ recovery performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The continuous development of lithium-based energy technologies is essential for advancing key fields, such as electronic devices, electric vehicles, and reliable clean energy systems1,2. The global lithium shortage underscores the urgent requirements for cost-effective Li+ recovery technologies3,4. To address these challenges, various advanced fine chemical separation technologies have been explored to separate Li⁺ from lithium-ion batteries (LIB) leachate containing multivalent cations X2+ (Co²⁺, Ni²⁺, etc.), including electrochemical leaching5,6, stepwise crystallization7, and membrane-based technology8,9. Among these, nanofiltration (NF) endowed with inherent advantages of cost-effectiveness, chemicals free, and scalability, has emerged as a promising Li⁺ recovery treatment process from waste LIB leachate10.

Compared to the conventional NF membranes, Janus charge (JC) NF membranes with positively charged surfaces prepared through secondary acylation have been promisingly used in the Li+ recovery field owing to their excellent Li+/X2+ separation performance11. However, the relatively low Li⁺ penetration (<60%) and water permeability (<10 LMH/bar) limit its Li+ recovery efficiency12,13. The related explanations were attributed to: i) an additional positively charged dense layer was mounted on the surface of JC NF membrane to obviously increase the resistance of both Li+ penetration and water permeation, resulting in a lower Li+ penetration and membrane permeability14,15; ii) in JC NF membrane, the special structure of positive charge layer-by-negative charge layer would cause the excessive accumulation of counterions between the Janus charge layers, and led to the “so-called” electrostatic shielding effect to susceptibly cause the local positive charge field cancellation, resulting in the reduction of multivalent cations removal16,17. Therefore, how to regulate the special microstructure of positive charge layer-by-negative charge layer to adjust the distribution of positive and negative charges in JC NF membranes to avoid the adverse electrostatic shielding effect, as well as to reduce the filtration resistance caused by the additional fabrication of a positively charged dense layer, are expected to the future development direction for the JC NF membrane with both excellent Li+ selective separation and high permeability.

To address the aforementioned challenges, we turn to nature to seek inspiration regarding the regulation of ion transport. Dust storms are known as a phenomenon of simultaneous movement of both wind and sand18. Why the sand particles can be moved together with the wind? It has been found that a positive-negative mosaic-like charge distribution structure exists in the internal dust storms, which could generate a strong electric field to provide pathways for the rapid movement and transport of charged sand particles19. In the Li+ recovery from the LIB leachate using NF technology, the charged Li+ ion and water were analogous to the charged sand particles and wind in the dust storms, respectively. Under such inspiration, this study proposed a discrete micro-nano isolated island strategy to artificially regulate the positive and negative charge distribution in the NF membrane, that transforming the typically layer-by-layer charge structure of the conventional JC NF membrane into the innovatively positive-negative mosaic-like charge structure, thereby engineering a novel anti-Janus (AJ) NF membrane to provide specific pathways for the rapid motion and transport of Li+.

This strategy designed a quaternary ammonium electrolyte, 4-amino-N,N,N-trimethylpiperidinium bromide (ATPB), characterized by a monosubstituted amine and short-chain conformation. These structural features enabled ATPB to modify the polyamide (PA) membrane in a point-to-point manner, thereby restructuring the electronegative PA layer into a mosaic-like charged membrane with discrete domains of positively and negatively charged islands. Advanced characterization and theoretical simulations were introduced to reveal the micro-electric fields generated by these discrete micro-nano isolated islands and their function to facilitate low-energy-barrier ion partitioning, as well as their contributions to the rapid transport of Li⁺. Simultaneously, the effects of point-to-point manner on the decoupling of secondary acylation from secondary crosslinking, as well as on the simultaneous enhancement of ion selectivity and water permeability, were revealed. Furthermore, a Critical Efficiency Product (CEP) model was developed to systematically assess the Li+ recovery performance of NF membrane. This study is expected to provide theoretical and technical insights into the developments of advanced NF membranes capable of achieving both high permeability and Li⁺ recovery.

Results

Design and characterizations of ATPB and AJ NF membrane

To realize the discrete micro-nano isolated island modification of the PA layer, a specialized monomer, 4-amino-N,N,N-trimethylpiperidine bromide (ATPB), was designed. This monomer features a positive charge, a single secondary amine, and a short-chain conformation (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). ATPB was synthesized through Hofmann alkylation, which imparted a significantly higher positive charge to ATPB (21.85 mV). XPS analysis verified the formation of ATPB, with a new N1s core-level peak appearing at 401.5 eV, characteristic of quaternary ammonium groups (Fig. 1b)20. These results confirmed the successful synthesis of ATPB quaternary ammonium electrolyte (Supplementary Figs. 7–9).

a A Chemical structure of ATPB and its synthesis process. b XPS spectra of ATPB. c Charge distribution of internal cross-section characterized by TOF-SIMS. d Mean square displacement (MSD) and diffusion rate comparison of PIP and ATPB in n-hexane. e Electrostatic potentials of N, Cl, C, and O atoms in ATPB and TMC. f Gibbs free energy profile for the reaction of ATPB and TMC to form an amide. g Molecular structure of control NF and AJ NF membranes. Charge distribution of both h the membrane surface monitored by KPFM and i the internal cross-section characterized by TOF-SIMS, respectively. j Consistent zeta potential values on the top and bottom layers of AJ NF membrane. k Zeta potential of the top and bottom layers of control NF and AJ NF membranes at pH = 7, respectively.

Subsequently, ATPB was employed to modify the nascent PA layer through the discrete micro-nano isolated island strategy (Supplementary Fig. 2). Specifically, ATPB diffused into the nascent PA layer, and then anchored to the active acyl chloride sites via an acylation reaction, forming an anti-Janus (AJ) NF membrane with discrete charged island domain structure (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 10), and the grafting density of ATPB was 141.24 nm−1 (Supplementary Figs. 11–12). The resulting NF membrane was termed as AJ NF. During this process, two key reactions occurred: the primary reaction was the Schotten–Baumann reaction between ATPB and TMC, and the secondary reaction was the hydrolysis of remaining acyl chloride groups. Among these, the diffusivity and reactivity of amine monomers were critical for successfully constructing the discrete micro-nano isolated island structure and ensuring membrane stability21,22,23. In this study, ATPB exhibited a diffusivity of 3.82 × 10-10 m2/s in n-hexane, surpassing that of conventional piperazine (PIP) (3.67 × 10-10 m2/s) (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 13). This elevated diffusivity facilitated the rapid penetration of ATPB through the n-hexane phase, ensuring its efficient anchoring within the PA layer24.

To further investigate the acylation reactivity of ATPB, the reaction mechanism and primary reactive sites between ATPB and Trimesoyl chloride (TMC) monomers were examined using the density functional theory (DFT) and average local ionization energy (ALIE) analyses (Fig. 1e)25,26. The ESP analysis revealed that the nitrogen atom in ATPB showed a negative potential of −0.78 kcal/mol, whereas the carbon atom in the acyl chloride group of TMC displayed a highly positive potential of 0.51 kcal/mol, indicating its vulnerability to nucleophilic attack by ATPB. As shown in Fig. 1f, ATPB underwent nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl group of TMC through transition state TS1 (ΔG‡ = 20.1 kcal/mol), to form an ion-pair intermediate M1. This step followed an SN2-type activation mechanism, accompanied by a direct dissociation of the chloride anion. Subsequently, the chloride anion in M1 acteds as a base to abstract a proton via transition state TS2 (ΔG‡ = −1.3 kcal/mol), yielding the final product and releasing one molecule of HCl. The overall reaction was exothermic, with energy of 7.7 kcal/mol. This reactivity ensured the efficient anchoring of ATPB within the PA layer (Fig. 1g). Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) analysis further confirmed the presence of discretely and uniformly distributed positive charge domains (blue dots) and negative charge domains (yellow dots) on the AJ NF membrane surface (Fig. 1h, Supplementary Figs. 14–16). Time of flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) was employed to dissect the charge distribution through the depth of AJ NF membrane. As illustrated in Fig. 1i and Supplementary Fig. 15, the secondary ion signal representing the positively charged quaternary ammonium segments and negatively charged carboxyl segments were relatively uniformly distributed throughout the spatial depth of the PA layer, mainly owing to the rapid diffusivity and reactivity of ATPB. Therefore, it can be inferred that the discrete micro-nano isolated island charge structure was successfully engineered in the whole cross-section of PA layer of AJ NF membrane. Consequently, AJ NF membrane exhibited a consistent and significant increase in the positive charge density on both the top and bottom surfaces (Fig. 1j, k, Supplementary Fig. 17). These results confirmed that ATPB enabled effective anchoring throughout the PA layer in a point-to-point manner. This represented an advancement over the traditional secondary acylation approach which only modified the surface layer. FTIR spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 18) confirmed the ATPB successful crosslinking. These findings verified the formation of discrete micro-nano isolated island structure and preservation of the crosslinked structure.

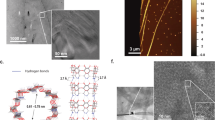

As shown in Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Figs. 21–22, the surface morphology of the control NF and AJ NF membranes was characterized. Remarkably, after introducing ATPB, the AJ NF membrane with surface roughness (Ra) and thickness measured at 15.9 nm and 218 nm, respectively, was comparable to the control NF membrane (Ra = 14.1 nm; thickness = 192 nm). This observation indicated that ATPB was embedded within the interior of the PA layer rather than forming an additional surface layer. This result differed from the previous findings where the secondary acylation routinely led to a significant increase in active layer thickness. This difference was attributed to the unique point-to-point anchoring of ATPB at active sites within the PA layer, which successfully decoupled the secondary acylation process and secondary crosslinking, namely, just secondary acylation occurred, but secondary crosslinking process disappeared, to effectively avoid the increase in the thickness and density of PA layer.

Surface and cross-sectional SEM images of a control NF and b AJ NF membranes. c Permeability and salt rejection of control NF and AJ NF membranes. d Intrinsic water permeability and volumetric flux of control NF and AJ NF membranes. e Schematic illustration of segmental structures (top), water transport mechanisms (middle), and water-binding energies (bottom) for segments I (PIP-TMC), II (ATPB-TMC), and III (carboxyl), respectively. f Hydrogen bond statistics for segments I and II during water transport. g RDF between water molecules and segments I and II. h Overall performance comparison between control NF and AJ NF membranes. Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicated experiments.

Crossflow filtration tests using five salt solutions were conducted to evaluate the impact of ATPB anchoring on NF membrane performance. As shown in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 23, the AJ NF membrane achieved rejection rates above 93% of divalent cation salt (MgCl₂ and CoCl₂), while rejection for monovalent salts LiCl and NaCl remained rather low, at 15.01% and 19.18%, respectively, indicating enhanced Li⁺/X²⁺ selectivity compared to the control NF membrane. Notably, the water permeability of AJ NF membrane was retained at 20.72 L m⁻² h⁻¹ bar⁻¹, demonstrating that the proposed modification successfully overcame the conventional trade-off between permeability and selectivity. Furthermore, AJ NF membrane exhibited operational stability (Supplementary Fig. 24). To more precisely assess the membrane permeability, the intrinsic permeability and volumetric flux were calculated (Fig. 2d). Surprisingly, the AJ NF membrane showed higher intrinsic permeability (1.92 × 10⁻⁹ m²s−1) and volumetric flux (5.03 × 10⁻6 L m⁻1 h⁻¹ bar⁻¹) than the control NF membrane. This unexpected increase challenged the conventional notion that secondary acylation would reduce the water permeability.

Water absorption at the membrane surface and diffusion within the membrane matrix were key mechanisms that governed the overall permeability. The aforementioned findings suggested that the ATPB anchoring process involved the hydrolysis of acyl chloride groups, generating carboxyl groups with a negative charge that would influence both surface hydrophilicity and charge density. Accordingly, the key reaction parameters, such as temperature and reaction time, were optimized in this study to control the extent of acyl chloride hydrolysis, thereby tuning the balance between surface hydrophilicity and charge density in the AJ NF membrane. The resulting ATPB-modified membrane displayed both improved hydrophilicity and increased surface free energy (Supplementary Fig. 25), which promoted faster wetting and water uptake. Additionally, to investigate the water diffusion within membrane matrix, molecular dynamic (MD) simulation was performed to analyse the energy changes during water transport across the membranes. Models were constructed for PA segments derived from PIP-TMC (segment I), ATPB-TMC (segment II), and the carboxyl groups formed on the membrane surface (segment III) (Fig. 2e, bottom). The calculated water-binding capacity of segments I, II, and III were −147.3311 kJ/mol, −132.9632 kJ/mol, and −378.7797 kJ/mol, respectively. These results indicated that the carboxyl groups (segment III) on the membrane surface conferred the strongest affinity for water molecules, suggesting that a rational design of carboxyl content by regulating the hydrolysis process can enhance the membrane hydrophilicity and water uptake. Additionally, hydrogen bonding analysis revealed that segment II formed fewer hydrogen bonds (3.8) with surrounding water molecules compared to segment I (4.5) (Fig. 2f). Radial distribution function (RDF) analysis also showed that fewer water molecules clustered around segment II than around segment I (Fig. 2g). These findings suggested that ATPB-TMC segments (II) interacted weaker with water, thereby lowering the internal resistance of water diffusion through the AJ NF membrane. Together, these simulation results supported the hypothesis that ATPB anchoring improved the water adsorption by the membrane surface and water diffusion through the internal membrane, ultimately contributing to the ultrafast water permeability of AJ NF membrane.

Highly ion-selective separation mechanism

To verify the potential mechanism of the strong selectivity of AJ NF membrane, the ion separation performance was evaluated using binary salt mixtures. These combinations of salt mixtures mainly simulated the ion compositions found in LIB leachate, salt lake brines and industrial wastewater. As shown in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 26, compared to the control NF membrane, the selective separation factors of various salt mixtures by AJ NF membrane increased by 647%-904%, e.g., 730% for Li+/Co²⁺ and 873% for Li+/Mg²⁺, respectively. To further distinguish the effects of Donnan exclusion and steric hindrance, the rejection behaviors of both NF membranes were tested using cations and neutral solutes. As shown in Fig. 3b, AJ NF membrane consistently exhibited high rejection of divalent ions, independent of ion size. In contrast, both control NF and AJ NF exhibited similar rejection profiles for neutral molecules. These observations suggested that steric exclusion is not the primary factor governing the improved separation of divalent cations by the AJ NF membrane.

a Ion selectivity separation factors of control NF and AJ NF membranes. b Rejection performance of control NF and AJ NF membranes for metal salts and neutral solutes with varying molecular sizes. c MWCO and pore size distribution of the control NF and AJ NF membranes. d MD simulation of FFV in the pore structures of control NF (left) and AJ NF (right) membranes. e Zeta potential profiles of control NF and AJ NF membranes. f Binding free energy decomposition analysis for Co2+ and Li+ ions interacting with functional segments of control NF and AJ NF membranes. g RDF and PMF of Co²⁺ ions around NF membranes. Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicated experiments.

NF membrane selectivity is governed by the energy barriers of ion transport process, which are modulated by steric hindrance, dielectric repulsion, and Donnan exclusion. The microporous structure of AJ NF membrane was compared with that of the control NF membrane (Supplementary Figs. 19–20, and Supplementary Table 1). As shown in Fig. 3c, the average pore radius of AJ NF membrane was 0.206 nm, nearly identical to that of the control NF membrane (0.204 nm), indicating that both NF membranes maintained a sub-nanometer pore structure. The fractional free volume (FFV) of AJ NF and control NF membranes was calculated by MD simulations as 21.06% and 22.98%, respectively (Fig. 3d), confirming that the internal microporosity of AJ NF was comparable to that of the unmodified membrane. These results highlighted that AJ NF membrane preserved the intrinsic sub-nanometer pore structure of the original control NF membrane; parameters such as pore size, dielectric constant, and related steric and dielectric exclusion effects, all remained unchanged27. According to the classic pore-flow model for NF membranes, this confirmed that size-based exclusion was not the main contributor to the observed increase in Li+/X2+ selectivity. Moreover, these results highlighted that the point-to-point anchoring of ATPB prevented the additional large-area crosslinking or lamellar growth.

To further examine the influence of membrane charge density on the ion rejection, zeta potential measurements were conducted (Fig. 3e). AJ NF membrane exhibited a near-neutral zeta potential, with a measured surface potential of −7.01 mV at pH = 7, compared to −23.14 mV for the control NF membrane. This shift was due to the anchoring of ATPB, which introduced positively charged quaternary ammonium groups. Even at pH 9.5, the zeta potential of AJ NF membrane remained relatively higher (−10.83 mV) than that of the control NF membrane (−33.27 mV). These results demonstrated that the Donnan exclusion, governed by the membrane charge density, was a key determinant of the superior ion-selective separation performance achieved in AJ NF membrane.

To better understand the ion-membrane interactions before and after ATPB modification, the interactions between typical cations and functional segments within NF membranes decomposition analysis was performed using DFT calculations. As shown in Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 27, electrostatic interactions were identified as the primary driving force for the cation rejection or penetration. The divalent cations faced a 174% greater free energy barrier when diffusing through the AJ NF membrane than through the control NF membrane, which was in agreement with the experimental results. This finding was further supported by RDF and potential of mean force (PMF) analyses for Co²⁺, Mn²⁺, and Ni²⁺ ions around functional segments of both NF membranes (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Figs. 28, 29). In contrast, both membranes exhibited minimal interaction energies with Li+. The experimental and simulation results collectively suggested that the elevated positive surface potential of AJ NF membrane, enabled the effective Li⁺/X²⁺ selectivity and high LiCl permeability. These findings highlighted the success of discrete micro-nano isolated island strategy in enhancing the divalent cation (X2+) rejection while enabling the selective transport of monovalent ions (Li+), thereby overcoming the “so-called” trade-off between ion penetration and selectivity.

NF membranes are inherently constrained by the trade-off among water permeability, Li+/X2+ selectivity, and Li+ penetration. An ideal membrane for resource recovery should combine high Li+/X2+ selectivity to ensure the high-purity Li+ recovery, high water permeability to minimize specific energy consumption and efficient Li+ penetration to maximize Li+ recovery efficiency. To further evaluate the performance of AJ NF membrane, its selectivity, permeability, and Li+ penetration were benchmarked against those reported in previous studies, including laboratory-scale and commercially available alternatives. Figure 4a illustrates widely accepted evaluation frameworks for NF membranes performance: water permeability-Li+/X2+ selectivity. Meanwhile, the Li+ penetration-Li+/X2+ selectivity of NF membrane was also evaluated (Fig. 4b). In these plots, the top-performing materials are positioned in the upper right quadrant of each plot. The incorporation of ATPB enabled the AJ NF membrane to achieve a high dual performance in both Li+/X2+ selectivity-permeability and Li+/X2+ selectivity-Li+ penetration. Though these 2D trade-off plots could provide a convenient and intuitive assessment on the performance of NF membrane, two significant limitations still existed: i) limited to qualitative comparisons of two performances (unless more complex trade-off plots are drawn); and ii) ion selectivity refers to the ratio of concentration of divalent cation X2+ (e.g., Co2+, Mg2+, Ni2+) to Li+ before and after NF treatment, representing the purity of Li+ in the permeate; in contrast, the penetrated Li+ concentration in the permeate represents the available recovery rate of Li+. Based on the typical calculation formula, even slight changes in the value of X2+ removal efficiency (RX2+), would significantly influence the value of the ion-selective separation factor (Fig. 4c)28,29. For example, when the X2+ rejection rate increases from 98% to 99% (RLi+ = 50%), the Li+/X2+ separation factor would increase 100%. In such case, though a high Li+/X2+ separation factor was achieved, the actual Li+ recovery efficiency exhibited almost no significant improvements, indicating that the Li+/X2+ separation factor loses its inherent function in reflecting the Li+ recovery. In practical industrial applications, the main purpose was Li+ recovery, thus, such a “so-called” ion-selective separation factor does not meet the requirements for Li+ recovery. To address such problems, an evaluation model, the CEP evaluation index, has been proposed with the expectations to provide a comprehensive assessment of Li+ recovery performance of NF membranes (ion-selective separation, Li+ recovery rate, and water permeability). As shown in Fig. 4d, in addition to the control NF and AJ NF membrane, 6 typical types of commercially available NF membranes were also adopted to carry out the experiment under the same operational conditions; furthermore, some previously reported results using different NF membranes were also estimated using this CEP model. It can be found that the CEP model could effectively reflect the Li+ recovery efficiency and correspond well with the reported studies but with a much higher accuracy. Especially, the AJ NF membrane demonstrated the highest Li+ recovery efficiency, ranking as one competitive candidates for efficient and scalable Li+ recovery.

a Trade-off relationship between Li+/X2+ selectivity and water permeability. b Trade-off relationship between Li+/X2+ selectivity and Li+ penetration. c Illustration of the amplification effect in rejection of X2+ assessment based on the conventional calculation methods for Li+/X2+ separation factors. d Comprehensive evaluation of Li+ recovery efficiency of different NF membranes using the CEP metric.

Li+ recovery from waste LIB

Laboratory-scale experiments were conducted to evaluate the effect of the discrete micro-nano isolated island charge structure of AJ NF membrane on the Li+ recovery efficiency from the real LIB leachate under varying operation conditions. The main ion compositions of LIB leachate, e.g., Li+, Co2+, Mn2+ and Ni2+, were analyzed (Supplementary Table 2), and the selective separation factors of Li+/X2+ of NF membranes were investigated systematically. As shown in Fig. 5a, AJ NF membrane consistently exhibited higher rejection of X2+ across a range of pH values while maintaining a high penetration for Li+. Ion rejection efficiency increased with driven pressure and closely approached the asymptotic limit at higher driven pressure levels30,31. As shown in Fig. 5b, AJ NF membrane demonstrated a 210%-380% improvement in Li+/X2+ selectivity over the control NF membrane, particularly under acidic conditions (pH=4). Meanwhile, at pH values of 6, 5, and 4, the Li+ proportion (16.94% in the feed solution) in the permeate of AJ NF membrane also increased to 77.38%, 78.56%, and 81.42%, respectively (Fig. 5c). These results further highlighted that the discrete micro-nano isolated island strategy endowed the AJ NF membrane with consistently high X2+ rejection and Li+ penetrance, even under the conditions of either high concentration or complex ion conditions as the real LIB leachate, confirming the practical applicability of AJ NF membrane for efficient and scalable Li+ recovery.

a Ion rejection performance of AJ NF membrane as a function of solution pH and driven pressure during treatment of LIB leachate. b Li+/X2+ separation factors of control NF and AJ NF membranes at varying water flux and pH conditions. c Li+ concentration in the permeate after NF treatment using control NF and AJ NF membranes. d Schematic illustration of a two-stage NF process for Li+ recovery from LIB leachate. e Ion composition in the permeate of the first and second NF stages, respectively. f All LIB leachate ions rejection of control NF and AJ NF membrane membranes. g Anti-fouling tests for NF membrane in treating BSA solution. h Li+/X2+ separation factors of AJ NF membranes and commercial membranes (PRO-XS2, Fortilife XC-N, and NF270). Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicated experiments.

As a proof of concept, the potential improvements of Li+ recovery efficiency in industrial NF treatment processes of waste LIB enabled by the AJ NF membrane design were quantified (Fig. 5d)32. The initial leachate exhibited a high osmotic pressure of 56.97 kPa, which decreased by 64.88% after the first NF stage, accompanied by a stabilized water flux of approximately 92.05 LMH (Supplementary Fig. 30). After the second stage NF treatment, the Li+ purity increased to 95.3% in the final permeate (Fig. 5e), as well as a stable and efficient performance was achieved during continuous 96-hour operation by the two-stage NF system (Supplementary Fig. 39). This high-purify Li+ output is advantageous for downstream purification and recovery of lithium, which aligned well with the mainstream industrial Li+ recovery processes such as chemical precipitation and re-crystallization. Similarly, compared to the control NF membrane, the AJ NF membrane also conferred significant improvements in the removals of other trace multivalent ions (e.g., Fe2+, Al3+, Cu2+), and also maintained a high rejection of particulates in the LIB leachate (Fig. 5f, Supplementary Fig. 31). Importantly, unlike the conventional NF membrane, AJ NF membrane just conferred a lower removal of organics (56.43%), which endowed AJ NF membrane higher capacities in alleviating the organics-caused membrane fouling to ensure a more steady filtration performance of Li+ recovery (Supplementary Fig. 32). Furthermore, compared to the control NF membrane, AJ NF membrane exhibited superior anti-fouling and anti-scaling performance, as well as desired hydraulic cleaning efficiency (Fig. 5g, Supplementary Fig. 33), attributing to the stronger hydration and electrostatic repulsive to effectively prevent the adsorption of pollutant onto the AJ NF membrane surface. Moreover, even under high operating pressure conditions (Supplementary Figs. 34–36), the AJ NF membrane could also constantly maintain a stable and efficient performance. As displayed in Fig. 5h, compared with the commercial NF membranes (e.g., PRO-XS2, Fortilife XC-N, and NF270), AJ NF membrane demonstrated the highest Li+/X²⁺ separation factor, with improvements by 100%-500%. Therefore, the AJ NF membrane with uniquely engineered discrete micro-nano isolated island structure conferred highly promising practical feasibility for effective Li+ recovery from real LIB leachate.

Discrete charged island domain structure

To gain molecular-level insights into the selective ion-separation mechanism of AJ NF membrane and how the discrete charged island domains structure overcame the excessive shielding and electrostatic shielding effect, MD simulation was employed33,34,35. Idealized models of two membrane types were constructed: an AJ membrane featuring positive-negative mosaic-like charge structure (representing the AJ NF membrane) and a conventional Janus charge (JC) NF membrane with layer-by-layer charge structure, respectively (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 37). Both models had comparable fractional free volumes (FFVs), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 38, ensuring that pore structure differences did not influence the interpretation of charge-related effects. MD simulations were then used to examine the interactions between these membrane and feed ions (CoCl₂, LiCl) in a binary electrolyte solution. Further details regarding the model assumptions, boundary conditions, and algorithms are provided in Supplementary Information. To track ion transport, under canonical ensemble (NVT) simulations were run for 100 ns.

a Snapshots of AJ membrane (top) and JC membrane (bottom). b1-b4, c1-c4 Spatial distributions of feed ions in the XZ plane at b1, c1 0 ns, b2, c2 10 ns, b3, c3 40 ns, and b4, c4 100 ns for b AJ and c JC membrane systems. d Diffusion coefficients and e mean square displacements (MSD) values of Co²⁺, Li⁺, and Cl⁻ ions along the X directiont for AJ and JC membranes. Quantity density of Co²⁺, Li⁺, and Cl⁻ ions distribution in the X direction at 100 ns for f AJ and g JC membrane systems. Error bars represent the standard deviation from triplicated experiments.

Figure 6b, c illustrates the spatial distributions of all feed ions projected onto the XZ plane at four different time points. Due to the strong influence of both ion-ion and ion-membrane on ion partitioning, the three ion types (Cl⁻, Li⁺, and Co²⁺) exhibited varied diffusivities in the AJ and JC membrane systems.

At 10 ns (Fig. 6b2, c2), Cl⁻ and Li+ ions have already begun to penetrate into the membrane in AJ and JC systems. At 40 ns (Fig. 6b3, c3), many Cl⁻ and Li+ ions have reached the permeate side in the AJ system. However, in the JC system, due to the strong electrostatic repulsion between the positively charged membrane surface and Li+, Li+ hardly reached the permeate side. Furthermore, in the JC system, the special structure of positive charge layer-by-negative charge layer would cause the excessive accumulation of Cl− between the Janus layers (Fig. 6c4) due to the electrostatic repulsion between Cl⁻ and the negatively charged layer, which was susceptible to cause local positive charge field cancellation and result in the “so-called” electrostatic shielding effect (Supplementary note 1), resulting in the increase of Co2+ diffusivity (DJC,Co = 1.48 × 10⁻⁹ m²/s) (Fig. 6d, e) and decrease of Co2+ removal rate. In contrast, in the AJ membrane featuring with discrete micro-nano isolated island charge structure, Cl− and Li+ exhibited fast diffusivity (DAJ,Cl = 6.53 × 10⁻⁹ m²/s, DAJ,Li = 5.43 × 10⁻⁹ m²/s) and could rapidly penetrate though the NF membrane without excessive accumulation, and thus breakthrough the “so-called” electrostatic shielding phenomena (Fig. 6f, g). Consequently, both higher rejection rate of Co²⁺ and penetration of Li+ were achieved in the AJ membrane system. The aforementioned results further supported the initial hypothesis that the discrete micro-nano isolated island charge structure in AJ NF membrane could effectively breakthrough the electrostatic shielding effect to promote Li+ transport and recovery.

At the end of the 100 ns simulation, 38.33% of Cl⁻ ions had reached the permeate side in the AJ system, whereas just 26.67% in JC system. Meanwhile, 85.00% of Co²⁺and 70.00% of Li⁺ ions remained in the feed side and membrane interior in the AJ system, whereas in the JC system, 80.00% of both Co²⁺ and Li⁺ remained in these regions. This resulted in a temporary net positive charge on the feed side and a net negative charge on the permeate side due to an artifact of the limited simulation duration. Over longer timescales, charge neutrality will eventually be restored on both sides30.

In contrast to the JC membrane, the AJ membrane featured a unique, discrete micro-nano isolated island charge structure. Specifically, the positively charged domains exhibited an electrostatic potential gradient which decreased radially from the center of each domain toward the surrounding negatively charged domains, forming the structural basis for the development of localized micro-electric fields. Similar to the transport of charged sand particles in dust storms, when Li+ entered the negatively charged region, it could penetrate into the membrane through the electrostatic attraction, completing the transmembrane transport. When Li⁺ entered the positively charged region, it experienced a tangential electrostatic force that guided its lateral movement along the field lines toward the adjacent negatively charged domain. Subsequently, it transported through the membrane via a combination of convection, diffusion, and electromigration (Fig. 7a, b). Thus, the spatially discrete micro-nano isolated island charge structure of AJ NF membrane established efficient transport pathways for Li⁺, significantly improving the Li⁺ transmembrane transport efficiency.

a Schematic illustration of the local electric field distribution at the central and peripheral junctions of charged island domains on the membrane surface. b Conceptual illustration of the ion separation mechanisms in the AJ and JC membranes. c Geometric distribution of charged island domains and the corresponding interfacial packing density.

In contrast, for divalent cations, such as Co2+, the discrete micro-nano isolated island charge structure of AJ NF membrane conferred little influence on its removal, because the larger ionic radius, higher charge and shorter Debye length of divalent co-ions would result in a stronger electrostatic repulsion, greater steric hindrance, and a narrower peripheral region.

Furthermore, based on the Donnan partitioning theory, it's also found that the spatial distribution of charge island domains of NF membranes served a fundamental role in governing ion partitioning and transmembrane transport. Specifically, the larger the peripheral region was, the rapider the transport of monovalent ions achieved. To quantitatively assess this effect, the interfacial packing density (σ) was investigated (Supplementary note 2). This parameter represents the total length of the junction edges between oppositely charged domains per unit membrane area and serves as a metric for evaluating the density and distribution of charge-domain interfaces. As shown in Fig. 7c, a denser geometric arrangement of charged islands resulted in a higher σ value, corresponding to a larger peripheral region and broader surface coverage of low-energy-barrier zones14,15. These findings suggested that future advancements in membrane design should focus on the nanoscale control over the spatial arrangement of charged island domains in the horizontal plane of NF membrane. In particular, fabricating mixed-charge membranes with higher interfacial packing densities is key to achieve a more efficient ion selectivity.

Discussion

Inspired by the positive-negative mosaic-like charge structure of dust storms, this study proposed a discrete micro-nano isolated island charge structure design strategy for NF membranes to enable rapid ion transport driven by electric field forces to promote Li+ penetration and overcome the “so-called” electrostatic shielding effect typically observed in conventional JC membranes. A quaternary ammonium electrolyte monomer, ATPB, was designed with high diffusivity and reactivity to restructure the electronegative PA layer into a positive-negative charge mosaic AJ NF membrane. The resulting AJ NF membrane achieved improvements in the Li⁺/X²⁺ selectivity of 647%-904%, Li+ penetration at 84.99% and permeability at 20.72 LMH/bar. To enable a more comprehensive evaluation of AJ NF membrane performance, a metric model, the Critical Efficiency Product (CEP), was proposed. Compared with the typical model, the two key limitations in current membrane evaluation practices: (i) the reliance on simple two-metric graphical comparisons, and (ii) neglecting the important parameter of Li+ penetration caused by conventional separation factor calculations, were successfully addressed in the CEP model. In summary, the discrete micro-nano charge isolated island charge structure strategy provides a significant advancement in overcoming the traditional permeability-selectivity trade-off in NF membranes, and indicated a transformative direction for developing next-generation NF technologies for Li+ recovery and LIB recycling applications.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

4-bromopiperidine hydrobromide (≥98%), piperazine (>99.0%), n-hexane (≥99%), glycerol (≥99%), sucrose (≥99.5%), glucose (≥98%), D(+)-raffinose pentahydrate (99%), cobalt chloride (≥99.7%), magnesium chloride (≥98%), lithium chloride (≥99%), manganese chloride (≥98%), nickel chloride (≥99.99%), sodium sulphate (≥98%) and sodium chloride (≥99.5%), were purchased from Aladdin Industrial Corporation Co., Ltd. Trimethylamine solution (31-35 wt% in ethanol, 4.2 M) was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich Trading Co., Ltd. Trimesoyl chloride (>98.0%) was acquired from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. Polyethersulfone (PES) flat-sheet ultrafiltration membrane (150 kDa) was obtained from Microdyn-Nadir Co., Ltd.

Synthesis of ATPB

To synthesize 4-amino-N, N, N-trimethylpiperidinium bromide (ATPB), 4-bromopiperidine hydrobromide (4 g) was dissolved into 130 mL ethanol in a conical flask. Then, 30 mL trimethylamine (4.2 M in ethanol) was slowly added. The mixture was stirred and refluxed at 80 °C for 72 h. The resulting solution was evaporated, washed three times with ethanol, and subsequently dried in a vacuum oven at 65 °C for 8 h.

Preparation of AJ NF membrane

The ultrafiltration membrane was dried and immersed into a 0.3 w/v% aqueous PIP solution for 5 min, followed by excess removal using a rubber spatula. A 0.1 w/v% TMC solution in hexane was then poured onto the membrane surface and allowed to react for 20 s. The freshly prepared control NF membrane was immersed into a 2 w/v% ATPB aqueous solution (pH = 11.5) for 40 min, dried at room temperature, heat-treated at 55 °C for 3 min, and stored into the ultrapure water.

Critical efficiency product evaluation

The Li+ recovery performance of NF membranes was quantified using the Critical Efficiency Product (CEP), as described in Eq. (1).

where SLi/X is the separation factor between Li+ and X2+, PLi is the penetration of Li⁺, and J is the water permeability.

Density functional theory calculations

Geometry optimizations of all stationary points were carried out at the B3LYP-D3/6-31 G(d,p) level, incorporating Grimme’s D3 dispersion correction and the IEF-PCM solvation model to account for implicit solvation effects36,37,38,39,40,41,42. And the RESP (Restrained Electrostatic Potential) charges were employed, which are suitable for molecular dynamics simulations of flexible small molecules26,43,44. All calculations were conducted under standard conditions (1 atm, 298.15 K).

Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular dynamics simulation was employed to investigate the interaction between feed ions and AJ NF membrane (Supplementary note 3)45,46,47. The models of both AJ NF membrane and JC NF membrane were constructed by artificially polymerizing PIP, ATPB, and TMC monomers (Supplementary Information)48. The charge structure of NF membrane was regulated through the protonation in amine functional groups and the deprotonation from carboxylic functional groups, along with that counterions were used to neutralize and equilibrate the charged functional groups in the polymerized membrane models49,50. In order to prevent ions directly crossing the boundary from the feed reservoirs to the permeate reservoirs, the outer boundaries of feed reservoirs and permeate reservoirs are bounded by two single-layered graphene sheets, respectively. Finally, CoCl2 and LiCl with a concentration of 0.5 M were added to the feed side, corresponding to 20 Co2+, 20 Li+ and 60 counterions Cl−. During the simulation process, the size of the polymerized membrane structure remained constant. All molecular dynamics simulations were performed with the AMBER99SB force field51.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the article, Supplementary Information, and Source Data file. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Additional source data are available on Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30277285) Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Levin, T. et al. Energy storage solutions to decarbonize electricity through enhanced capacity expansion modelling. Nat. Energy 8, 1199–1208 (2023).

Lai, Z. et al. Direct recycling of retired lithium-ion batteries: emerging methods for sustainable reuse. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 107676 (2025).

Boroumand, Y., Abrishami, S. & Razmjou, A. Lithium recovery from brines. Nat. Sustainability 7, 1550–1551 (2024).

Yu, H. et al. Non-closed-loop recycling strategies for spent lithium-ion batteries: Current status and future prospects. Energy Storage Mater. 67, 103288 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Direct electrochemical leaching method for high-purity lithium recovery from spent lithium batteries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 4591–4597 (2023).

Schiavi, P. G. et al. Aqueous electrochemical delithiation of cathode materials as a strategy to selectively recover lithium from waste lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 88, 144–153 (2024).

Alcaraz, L., Rodríguez-Largo, O., Barquero-Carmona, G. & López, F. A. Recovery of lithium from spent NMC batteries through water leaching, carbothermic reduction, and evaporative crystallization process. J. Power Sources 619, 235215 (2024).

Wang, W. et al. Boosting lithium/magnesium separation performance of selective electrodialysis membranes regulated by enamine reaction. Water Res. 268, 122729 (2025).

Zhou, L., Gu, S., Li, S. & Xu, Z. Cyclodextrin-embedded nanofilms with “knot-thread” structure for efficient lithium extraction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2506147 (2025).

Zhao, G., Gao, H., Qu, Z., Fan, H. & Meng, H. Anhydrous interfacial polymerization of sub-1 Å sieving polyamide membrane. Nat. Commun. 14, 7624 (2023).

Li, M. J. et al. Electrochemical technologies for lithium recovery from liquid resources: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 154, 103202 (2022).

Jeon, S. et al. Extreme pH-resistant, highly cation-selective poly(quaternary ammonium) membranes fabricated via menshutkin reaction-based interfacial polymerization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2300183 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Wang, L., Sun, W., Hu, Y. & Tang, H. Membrane technologies for Li+/Mg2+ separation from salt-lake brines and seawater: A comprehensive review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 81, 7–23 (2020).

Zheng, R. et al. Enhancing Ion Selectivity of Nanofiltration Membranes via Heterogeneous Charge Distribution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 22818–22828 (2024).

Gao, F. et al. Interfacial Junctions Control Electrolyte Transport through Charge-Patterned Membranes. Acs Nano 13, 7655–7664 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. A Janus membrane with electro-induced multi-affinity interfaces for high-efficiency water purification. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn8696 (2024).

Zhao, S. et al. Polyamide Membranes with Tunable Surface Charge Induced by Dipole-Dipole Interaction for Selective Ion Separation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 5174–5185 (2024).

Rudge, W. A. D. Atmospheric Electrification during South African Dust Storms. Nature 91, 31–32 (1913).

Zhang, H. & Zhou, Y.-H. Reconstructing the electrical structure of dust storms from locally observed electric field data. Nat. Commun. 11, 5072 (2020).

Peng, H. & Zhao, Q. A Nano-Heterogeneous Membrane for Efficient Separation of Lithium from High Magnesium/Lithium Ratio Brine. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2009430 (2021).

Peng, H., Su, Y., Liu, X., Li, J. & Zhao, Q. Designing Gemini-Electrolytes for Scalable Mg2+/Li+ Separation Membranes and Modules. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2305815 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. An efficient co-solvent tailoring interfacial polymerization for nanofiltration: enhanced selectivity and mechanism. J. Membr. Sci. 677, 121615 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Engineering biomimetic sub-nanostructured ion-selective nanofiltration membrane for excellent separation of Li+/Co2+. Energy & Environ. Mater. 8, e12845 (2025).

Su, Y., Peng, H., Liu, X., Li, J. & Zhao, Q. High performance, pH-resistant membranes for efficient lithium recovery from spent batteries. Nat. Commun. 15, 10295 (2024).

Roohi, H. & Pouryahya, T. TD-DFT study of the excited state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) mechanism and photophysical properties in coumarin-benzothiazole derivatives: substitution and solvent effects. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 8, 647–665 (2023).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Computational Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Motevaselian, M. H. & Aluru, N. R. Universal reduction in dielectric response of confined fluids. Acs Nano 14, 12761–12770 (2020).

Yang, Z., Long, L., Wu, C. & Tang, C. Y. High permeance or high selectivity? optimization of system-scale nanofiltration performance constrained by the upper bound. ACS EST Eng. 2, 377–390 (2022).

Yang, Z., Guo, H. & Tang, C. Y. The upper bound of thin-film composite (TFC) polyamide membranes for desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 590, 117297 (2019).

Foo, Z. H. et al. Positively-coated nanofiltration membranes for lithium recovery from battery leachates and salt-lakes: ion transport fundamentals and module performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 100134 (2024).

Zhang, H., He, Q., Luo, J., Wan, Y. & Darling, S. B. Sharpening Nanofiltration: Strategies for Enhanced Membrane Selectivity. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 39948–39966 (2020).

Zha, Z., Li, T., Hussein, I., Wang, Y. & Zhao, S. Aza-crown ether-coupled polyamide nanofiltration membrane for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation. J. Membr. Sci. 695, 122484 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. A review of the nanofiltration membrane for magnesium and lithium separation from salt-lake brine. Sep. Purif. Technol. 354, 129169 (2025).

Wen, H., Liu, Z., Xu, J. & Chen, J. P. Nanofiltration membrane for enhancement in lithium recovery from salt-lake brine: A review. Desalination 591, 117967 (2024).

Liu, K., Epsztein, R., Lin, S., Qu, J. & Sun, M. Ion-ion selectivity of synthetic membranes with confined nanostructures. Acs Nano 18, 21633–21650 (2024).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the colle-salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron-density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Computational Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 10.1063/1.3382344 (2010).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the Damping Function in Dispersion Corrected Density Functional Theory. J. Computational Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Barone, V. & Cossi, M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 1995–2001 (1998).

Mennucci, B. & Tomasi, J. Continuum solvation models: A new approach to the problem of solute’s charge distribution and cavity boundaries. J. Chem. Phys. 106, 5151–5158 (1997).

Zhang, J. & Lu, T. Efficient evaluation of electrostatic potential with computerized optimized code. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 20323–20328 (2021).

Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 161, 082503 (2024).

Martínez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: a package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Computational Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Berendsen, H. J. C., Vanderspoel, D. & Vandrunen, R. Gromacs - a message-passing parallel molecular-dynamics implementation. Computer Phys. Commun. 91, 43–56 (1995).

Liu, S., Keten, S. & Lueptow, R. M. Effect of molecular dynamics water models on flux, diffusivity, and ion dynamics for polyamide membrane simulations. J. Membr. Sci. 678, 121630 (2023).

Ritt, C. L. et al. Ionization behavior of nanoporous polyamide membranes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 30191–30200 (2020).

Liu, S., Foo, Z., Lienhard, J. H., Keten, S. & Lueptow, R. M. Membrane charge effects on solute transport in nanofiltration: experiments and molecular dynamics simulations. Membranes 15, 184 (2025).

Lindorff-Larsen, K. et al. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins-Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 78, 1950–1958 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3208002), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (52370007), and the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (NO. 2025DX24).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. performed the experimental studies and wrote the manuscript. X.T. and H.L. conceived and supervised the project. Y.Z. performed the mathematical calculations. M.Z. and S.J. performed the morphology characterization and analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ismail Abdulazeez, Amir Razmjou, Jialing Xu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, M. et al. Advanced biomimetic nanofiltration membranes for lithium recovery with anti-janus charge structure. Nat Commun 17, 202 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66887-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66887-2