Abstract

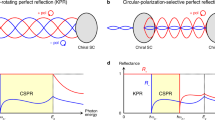

A microscopic mechanism for chiral p-wave superconductivity from Coulomb repulsion is proposed for spin- and valley-polarized state of rhombohedral multilayer graphene. The superconducting instability arises when strong Thomas-Fermi screening of the Coulomb potential allows Friedel oscillations to take over – leading to an effective attraction on length scales below the Fermi wavelength. The superconducting critical temperature is largest at low density below a Lifshitz transition to an annular Fermi sea, where the additional pocket strongly enhances Thomas-Fermi screening. The Lifshitz transition also marks a topological phase transition from a trivial to a topological superconducting phase hosting Majorana fermions. The chirality of the superconducting order parameter is selected by the chirality of the valley-polarized Bloch electrons. Our results are in reasonable agreement with observations in a recent experiment on tetralayer graphene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chiral superconductivity, characterized by spontaneous time-reversal symmetry breaking and finite-angular momentum Cooper pairing1, is a long-sought quantum phase of matter with unusual superconducting and magnetic properties. Interest in chiral superconductors is further fueled by their potential for hosting topological phases and Majorana fermions2,3. While previous material candidates, such as Sr2RuO44 and UTe25,6,7, showed initial signs of chiral superconductivity, recent experiments strongly suggest single-component superconducting order parameters that are non-chiral8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

Very recently, signatures of chiral superconductivity have been observed in rhombohedral-stacked tetralayer graphene under electron doping16. While superconductivity has been previously discovered and intensively studied in crystalline trilayer17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 and bilayer graphene31,32,33,34,35,36, the newly found superconducting state in tetralayer graphene at low density is remarkably distinctive in that it exhibits large spontaneous anomalous Hall effect above Tc and magnetic hysteresis in resistance below Tc. These observations demonstrate time-reversal-breaking superconductivity in a pure carbon system. Its pairing symmetry and pairing mechanism are open questions for investigation.

A key feature of rhombohedral multilayer graphene is the flat band dispersion near K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) point, leading to a strong correlation effect19,23. As a result, spin and valley isospin symmetry breaking occurs at low temperature, giving rise to half and quarter metal phases23. Interestingly, the superconducting state in tetralayer graphene at low density borders the quarter metal and its phase boundary shows no or little change with the applied magnetic field, indicating that the superconducting state is likely fully spin and valley polarized16. Thus, tetralayer graphene provides a rare opportunity for investigating Cooper pairing of single-flavor electrons in a solid-state platform.

In this work, we study the microscopic mechanism and pairing symmetry of superconductivity in multilayer graphene that develops from the spin- and valley-polarized quarter metal normal state [Fig. 1a, b]. Our mechanism is based on the overscreening of Coulomb interaction due to charge fluctuations, which leads to an effective attraction at length scales on a fraction of the Fermi wavelength, driving Cooper pairing. Using a minimal model for the band dispersion, our theory predicts that superconductivity occurs at low densities with enhanced density of states due to the annular Fermi surface and displacement field-induced flatness of the band. Based on our analysis, we further propose that a Wigner crystalline insulating state occurs at the Lifshitz transition from simply-connected to annular Fermi sea that splits the superconducting dome into two. This provides an explanation for the two proximate superconducting domes SC1 and SC2 with similar properties observed in the experiment16.

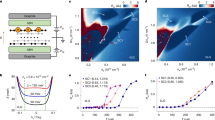

a Schematic of a chiral superconducting pairing appearing on top of an isospin-polarized quarter-metal state in multilayer graphene. b The chirality of the superconducting state is selected by the orbital magnetic moment of the electrons in the polarized valley. c Dispersion of ABCA graphene around the K valley19,23 for various electric potential differences D between top and bottom layers. The line color indicates the Berry curvature \({\Omega }_{{k}_{x},{k}_{y}}\).

In the spin- and valley-polarized state, the Pauli principle dictates that a Cooper pair can only be formed by two electrons having odd relative angular momentum, for example, with p- or f-wave symmetry37. Using Coulomb interaction and including the effect of dielectric screening in two dimensions, we find robust p-wave superconductivity at densities and temperatures in reasonable agreement with the experiment. The calculated Tc is on the order between 100 mK to a few K, depending on the dielectric screening of the Coulomb interaction in the graphene film relative to the surrounding dielectric. Relatedly, we find that electrons are paired even relatively far from the Fermi surface. Our results indicate that generally, a chiral p − iτp ordering is favored (τ = ±1 stands for \(K/{K}^{{\prime} }\) valley, independent of spin polarization), and we predict a number of relevant experimental signatures for it.

Results

Band dispersion

In rhombohedral multilayer graphene, low-energy bands come from sublattice-polarized states in the top and bottom layers. An out-of-plane electric field induces a potential bias equal to 2D between these layers and opens up an energy gap while flattening the dispersion near K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) points. Therefore, the Fermi energy is only a few meV above the band bottom for a small electron density of around 5 × 1011 cm−2, where time-reversal-breaking superconductivity is observed.

The low-energy band dispersion is highly tunable by the electric field. As the displacement field D increases, the curvature at K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) changes from positive to negative19,23 as shown in Fig. 1c for ABCA tetralayer graphene, resulting in a Mexican-hat shaped dispersion. In this case, a Lifshitz transition from simply-connected to annular Fermi surface occurs when the Fermi energy crosses the top of the hat as the electron density is reduced.

We capture the essential features of the electric-field-tuned conduction band in rhombohedral n-layer graphene with a minimal band dispersion:

where we set n = 4 corresponding to the tetralayer and treat k0 and m as D-dependent fit parameters to approximate the band dispersion of multilayer graphene, see SM (Supplementary Material) section A. We verified that qualitatively similar results for the superconducting order are obtained when the functional form of the dispersion is varied, as long as the main qualitative features are preserved. The functional form of Eq. (1) is derived from an effective 2-band model of rhombohedral tetralayer graphene with nearest-neighbor hopping38,39. The dispersion (1) is circularly symmetric. The inclusion of additional hopping terms leads to trigonal warping. For now, we neglect trigonal warping and Berry curvature effects and will treat them perturbatively later.

Rytova-Keldysh potential

The density-density interaction can be written as

where \({\psi }_{k}^{({{\dagger}} )}\) are the annihilation (creation) operators of spin-polarized electrons in a single valley. Importantly, in a 2D material surrounded by a dielectric with a lower dielectric permittivity, the Coulomb interaction between two charges can be described by the Rytova-Keldysh potential40,41,42, taking the form:

where ϵ = 5 ϵ0 is the dielectric permittivity of the surrounding hBN (with ϵ0 the vacuum permittivity), and rK is the Rytova-Keldysh parameter. The Rytova-Keldysh parameter depends on the difference between the dielectric response of the 2D material under study and that of the surrounding insulator. Since the 2D dielectric screening is determined by interband transitions and thereby depends on the band gap, rK of multilayer graphene is affected by the displacement field43. We will find that the superconducting pairing strength depends sensitively on rK.

Electron pairing from screened Coulomb repulsion

We study superconductivity in the spin- and valley-polarized state. This is justified because (i) valley polarization is observed to occur at a much higher temperature than superconductivity, and (ii) the primary superconducting state (SC1 in ref. 16) was observed within the quarter-metal state, and (iii) the primary superconducting states (SC1 and SC2) survive to very high in-plane magnetic fields.

Theoretically, we also expect that the energy scales of spin- and valley polarization to be much larger than superconductivity: Estimating the energy scale of isospin polarization in the Stoner model23 as Δpol ≈ ν(EF)V(2kF,2)EF ≈ 2 to 3 meV in the relevant range of density and dispacement field, it is an order of magnitude larger than the obtained pairing strength [see numerical results below].

Since total spin S2 and valley imbalance \({N}_{K}-{N}_{{K}^{{\prime} }}\) are conserved quantum numbers, there are no isospin fluctuations at zero temperature that can drive superconductivity in the fully-polarized quarter metal state. This motivates us to consider a mechanism for superconductivity in the spin- and valley-polarized state based on screening of electron-electron interactions by charge fluctuations44,45,46. The screening is described by the charge susceptibility \({\chi }_{e}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}({{{\bf{q}}}},\tau )=-\frac{1}{A}\langle {T}_{\tau }{\rho }_{e,{{{\bf{q}}}}}(\tau ){\rho }_{e,-{{{\bf{q}}}}}(0)\rangle\), which in random phase approximation (RPA) is determined by the expression

in terms of the charge susceptibility of the non-interacting electron gas

where τ is imaginary time and iΩn Matsubara frequencies. With the resulting dielectric response function, \({\epsilon }^{-1}({{{\bf{q}}}},\omega )=1+{V}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}}{\chi }_{e}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}({{{\bf{q}}}},\omega )/{e}^{2}\) one obtains the screened interaction potential

The charge susceptibility and screened interaction potential for the annular Fermi pocket are shown in Fig. 2a, b, respectively. The q → 0 limit of the denominator describing the screened interaction in Eq. (6) \({\lim }_{q\to 0}{V}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}}{\chi }_{e}^{{{{\rm{0R}}}}}({{{\bf{q}}}},0)/{e}^{2}=2\pi /{\ell }_{{{{\rm{TF}}}}}q\) defines the Thomas-Fermi screening length ℓTF = 4πϵ/e2ν(EF).

a Charge susceptibility of the non-interacting electron gas \({\chi }_{e}^{0{{{\rm{R}}}}}\) for D = 60 meV at density n = 0.5 × 1012 cm−2. The vertical lines indicate combinations of the momenta of the inner and outer Fermi surfaces kF,1 and kF,2. b, c Screened (solid line) and bare (dashed) Rytova-Keldysh interaction potential \(\tilde{V(q)}\) and \(\tilde{V(r)}\) in momentum and real space, respectively, with rK = 3 nm.

Due to the large density of states, the charge susceptibility becomes large for momenta below twice the Fermi momentum kF,2 of the outer Fermi surface. This leads to a suppression of the electron-electron interaction at small momenta and a peak at 2kF,2. This renormalized interaction potential promotes a p-wave superconducting instability.

In real space, the screening strongly reduces the repulsion above the Thomas-Fermi screening length ℓTF. Furthermore, Friedel oscillations appear with period 2kF,1, 2kF,2 due to the two Fermi surfaces. When the Thomas-Fermi screening length is much shorter than the wavelengths π/kF,1, π/kF,2, Friedel oscillations dominate over Coulomb repulsion and lead to an effective attraction at short length scales, as obtained from our calculations shown in Fig. 2c. We find ℓTF ≈ 1 to 2 nm, for typical parameters where we observe superconductivity as discussed below, while 2π/kF,1, 2π/kF,2 is typically around 20 nm to 30 nm. This mechanism benefits from a Mexican-hat-shaped dispersion because the additional pocket contributes a large density of states, leading to a short Thomas-Fermi screening length. This enables superconductivity at a larger density.

To determine the superconducting order parameter and its critical temperature, we solve the self-consistency equations

where Ek is the quasiparticle energy

Here, the interaction \(\tilde{V}({{{\bf{k}}}}-{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{\prime} })\) scatters a pair of electrons at opposite momenta \(({{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{\prime} },-{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{\prime} })\) to (k, − k).

Due to the rotational symmetry in our model, we decompose the pairing interaction into angular harmonics:

where we wrote \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}-{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{\prime} }}=\tilde{V}(\vartheta,k,{k}^{{\prime} })\) with ϑ the angle between k \({{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{\prime} }\) and \(k,\,{k}^{{\prime} }\) their magnitude. The order parameter can also be expanded into angular harmonics \(\Delta ({{{\bf{k}}}})={\sum }_{l=0}^{\infty }{\eta }_{l}(k){e}^{il\theta }\) with \(({k}_{x},{k}_{y})=k(\cos \theta,\sin \theta )\). The equations for the critical temperature Tc for different angular harmonics decouple.

Around Tc, we linearize the self-consistency equation and find for the individual angular harmonics,

For the superconducting order parameter at zero temperature, the self-consistency relation reads

Both equations can be solved iteratively, as detailed in SM section B. This angular decomposition applies to a circularly symmetric interaction potential, where the circular symmetry is preserved for the screened potential when the dispersion is circularly symmetric.

Importantly, the screened interaction \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}}\) is positive and large at momentum transfer \({{{\bf{q}}}}={{{\bf{k}}}}-{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{\prime} }\) around 2kF,2, compared to small q. Such q-dependent interaction favors an order parameter that takes opposite signs at opposite ±k points on the Fermi surface, i.e., it favors p-wave pairing.

For most superconductors, the pairing interaction is weak and therefore the pairing potential Δ(k) is small compared to the Fermi energy and only appreciable in the vicinity of the Fermi surface. For this reason, in solving the gap equation, it suffices to use “on-shell” pairing interaction \({\tilde{V}}_{l}(k,{k}^{{\prime} })\) at Fermi wavevectors \(k,{k}^{{\prime} }\). In contrast, in multilayer graphene, the combination of low electron density and flat band bottom leads to a large ratio of interaction to the Fermi energy. As a consequence, we will show that Δ and Tc can be on the order of the Fermi energy. Indeed, the recent experiment on tetralayer graphene16 reports an unusually high upper critical field at low density, indicating a strong-coupling superconductor with coherence length comparable to interparticle distance. For strong-coupling superconductors, the superconducting gap Δ(k) can be large even away from the Fermi momentum. Therefore, in solving the gap equation, it is necessary to use the interaction \({\tilde{V}}_{l}(k,{k}^{{\prime} })\) with full \(k,{k}^{{\prime} }\) dependence.

Our calculation of the density of states, ν and critical temperature Tc, as a function of electron density and displacement field, is shown in Fig. 3a, b, respectively. Both the displacement field D and the electron density n together determine the Fermi surface size and topology. For small D < Dc ≈ 40 meV, the dispersion increases monotonously with k and the Fermi surface is a single circle with \({k}_{F}=\sqrt{4\pi n}\), whereas at large displacement field (D > Dc), a Lifshitz transition from annular to simply-connected Fermi sea occurs with increasing electron density, which is accompanied by a large jump in the normal-state density of states at the Fermi level [Fig. 3a]. Correspondingly, superconducting properties depend strongly on the displacement field. For small D, a superconducting state is found at a small density where the chemical potential lies close to the relatively flat band bottom with a large density of states. For large D, the superconducting state sets in at low densities where the Fermi sea is annular, and Tc is largest close to the Lifshitz transition.

a Density of states of the minimal non-interacting model (Eq. (1)) normalized by νe = me/2πℏ2 with me the bare electron mass and (b) critical temperature of the chiral superconducting order as a function of electron density n and displacement field D. The dashed line indicates the Lifshitz transition from annular (A) to a single pocket (1P) Fermi sea. We choose rK = 3 nm for the Tc calculation. c Critical temperature for different dielectric screening parameterized by rK at D = 60 meV.

It should be noted that the value of Tc is sensitive to the dielectric screening of Coulomb repulsion by the multilayer graphene, which, in turn, depends on the displacement field-induced band gap. As a function of the Rytova-Keldysh parameter rK [Fig. 3c], the typical Tc at D = 60 meV ranges from Tc ≈ 3 K at rK = 1 nm to a suppression of Tc to below 0.1 K above rK = 10 nm. With bare Coulomb repulsion, a maximal Tc ≈ 8 K is obtained, see SM section H. The decrease of Tc with strong dielectric screening is consistent with electron pairing by Coulomb repulsion. Without knowing the value of rK for tetralayer graphene, we cannot make a quantitative prediction of Tc. Nonetheless, for the reasonable range of rK considered here, superconductivity always onsets at n < 0.7 × 1012 cm−2 in agreement with experimental observation, and the calculated Tc is acceptable compared to the experimental value, especially considering that the mean-field theory generally predicts higher values of Tc.

Going beyond our mean-field treatment, we estimate the critical temperature for a BKT transition47,48,49\({k}_{B}{T}_{{{{\rm{BKT}}}}}=\frac{\pi }{2}J\) determined by the superfluid stiffness. An order-of-magnitude estimate is obtained using the superfluid stiffness expression J = ℏ2n/4m for a quadratic band whose mass m ≈ 2me is matched so that its density of states matches the typical density of state ν(EF) ≈ 2νe at the Fermi energy of our model [compare Fig. 3a]. Based on this estimate, we find a typical BKT transition temperature kBTBKT ≈ 0.9 K at n = 0.5 × 1012 cm−2. This indicates that the critical temperature in this system may be limited by vortex proliferation in the BKT transition.

Strong-coupling superconductivity

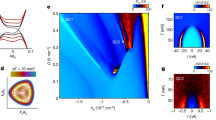

For the chiral px ± ipy pairing, the calculated pairing potential Δ(k) at T = 0 can reach a few tenths of the Fermi energy. Notably, Δ(k) is large not only close to the Fermi surface, but also extends to several times the Fermi wavevector with a sign change at around 2kF,2 [Fig. 4a]. Its functional form closely follows the interaction potential up to a proportionality factor setting the pairing strength [see SM section C]. The presence of substantial pairing potential away from the Fermi surfaces is a consequence of the strong-coupling nature of this superconducting state—because kBTc and Δ are of the order of the Fermi energy, pairing between electrons away from the Fermi surface is relevant. This is captured by our direct solution of Eqs. (10), (11).

a Momentum-dependent p-wave pairing potential Δ(k), where the tone (from black to light) indicates its magnitude and the hue corresponds to the complex phase. The white circles show the Fermi surfaces. b Zero-temperature spectral gap \({\Delta }_{0}={\min }_{k}{E}_{k}\) as a function of displacement field D and electron density ns. The dashed white line indicates the Lifshitz transition from annular (A) to a single-pocket (1P) Fermi sea. The cyan line bounds a (shaded) region at small densities and moderate displacement fields, where rs ≥ 40.

Due to the large pairing potential, the chemical potential changes appreciably in the superconducting state. This can be estimated by taking into account the pairing potential in relating electron density to chemical potential

At zero temperature, the change in chemical potential approaches 0.1 meV. The change in electron density is taken into account in Fig. 4b. Near Tc, the pairing potential is strongly temperature dependent \(\Delta \propto \sqrt{1-T/{T}_{c}}\), and therefore the change in chemical potential δμ ∝ ∣Δ∣2 is expected to increase linearly with decreasing temperature.

Topological superconductivity and Lifshitz transition

The quasiparticle gap \({\Delta }_{0}\equiv {\min }_{k}{E}_{k}\) as a function of density n and displacement field D is shown in Fig. 4b. Our p ± ip superconductor generally has a full gap, except at the Lifshitz transition from simply-connected to annular Fermi sea, where the system has a point node at the Fermi point k = 0 at which the pairing potential vanishes. The closing of the quasiparticle gap marks a topological quantum phase transition from a topological superconductor with unity Chern number in the region with a single Fermi pocket to a topologically trivial state in the annular region at large displacement fields50,51. The topological superconductor at small displacement fields hosts chiral Majorana edge modes and Majorana zero modes in the vortex2. In contrast, the trivial state with annular Fermi sea is adiabatically connected to the Bose-Einstein limit μ → −∞, because the pairing potential Δ(k) is finite at the band bottom of the Mexican hat dispersion, which forms a ring at k ≠ 0. Note that in our theory, even though the superconducting gap vanishes at k = 0 at the Lifshitz transition, the gap at the outer Fermi surface Δ(kF2) and critical temperature remains large throughout the transition– therefore the quasiparticle gap closure is not visible in the critical temperature calculations Fig. 3b.

Competing state

Since the p-wave superconductivity found in our RPA calculation occurs at relatively low density, it is important to consider its competition with the Wigner crystal state, which generally appears in 2D Coulomb systems at sufficiently low density. To estimate the transition to the Wigner crystal, we compute the gas parameter rs = Eint/Ekin given by the ratio of interaction Eint to kinetic energy Eint52. In our calculations of rs here, we included a realistic distance d = 30 nm to the metallic gates, whose screening modifies the bare interaction potential \({V}_{q}\to {V}_{q}\tanh qd\). We verified that this screening does not visibly affect our calculations of Tc and superconducting gap; however, rs depends sensitively on the gate screening as the interparticle distances at low density approaches tens of nm.

In Fig. 4, the region where rs > 40 is encircled by the cyan line; in a homogeneous electron gas, the transition to a Wigner crystal occurs around rs ≈ 30−4052,53,54,55,56. This region is where the band bottom is most flat, so that the kinetic energy per particle is low. It coincides with the region where the density of states is largest, see Fig. 3a. We expect crystalline order is likely to dominate there, so that the superconducting region is divided into two, separated by an insulating Wigner crystal state.

Trigonal warping and Berry curvature effects

Our minimal model neglects trigonal warping, which arises from electron hoppings beyond nearest-neighbor atoms in multilayer graphene. With trigonal warping, the band dispersion becomes asymmetric ϵk ≠ ϵ−k, which weakens intravalley pairing between ±k states. Fortunately, the energy scale of trigonal warping is small in tetralayer graphene in the range of density and displacement field of interest, as evidenced by the nearly symmetric band dispersion shown in Fig. 1. Furthermore, our superconducting state driven by Coulomb interaction has a large gap up to a few tenths of Fermi energy, and therefore is robust against the pair breaking effect of trigonal warping.

Up to now, we have neglected the effect of electron Bloch wavefunctions \(\left\vert {u}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\right\rangle\) within the unit cell. The momentum dependence of the complex-valued wavefunction \(\left\vert {u}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\right\rangle\) gives rise to Berry curvature, breaking time reversal symmetry, when the system is valley polarized57. We now show that the Berry-phase effect generally favors a particular chirality for p-wave pairing within a given valley. To see this, we note that the full interaction term for the electrons in the conduction band is generally of the form

where \({\widetilde{\psi }}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{({{\dagger}} )}\) creates an electron in the state \(\left\vert {u}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\right\rangle\) in the conduction band. Compared to Eq. (2), the full interaction contains the form factor \(\langle {u}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}+{{{\bf{q}}}}}\left\vert \vert {u}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\right\rangle \langle {u}_{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{\prime} }-{{{\bf{q}}}}}\left\vert \right\vert {u}_{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{\prime} }}\rangle\), which is complex-valued and thus breaks the time-reversal symmetry of the low-energy theory.

Anticipating zero-momentum Cooper pairing, we define \({{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{\prime} }=-{{{{\bf{k}}}}}_{1}-{{{\bf{q}}}}\) and focus on − k1 = k2 = k. With this, we expand the form factor into harmonics

where \({\alpha }_{l}^{\tau }={({\alpha }_{-l}^{-\tau })}^{*}\) due to time-reversal symmetry relating the two valleys τ = ±1. The limit αl → 0 for all l ≠ 0 recovers our previous analysis using Eq. (2). Now, we treat αl with l ≠ 0 as a perturbation to the p-wave superconducting state.

Including the form factor, the condensation energy is

For a pairing potential \(\Delta ({{{\bf{k}}}})={\eta }_{j}(k){e}^{ij{\varphi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}\) with angular momentum j, using the angular decomposition of the form factor Eq. (14) and the pairing interaction Eq. (9), Ec can be expressed as

When the form factor is a constant, only the α0 term is present and \({\tilde{V}}_{j}={\tilde{V}}_{-j}\) guarantees equal condensation energy for ±j pairings. However, with broken time reversal symmetry, αl≠0’s are generally nonzero and therefore the condensation energy is generally different for the two p-wave chiralities. In particular, a large contribution from the terms j = −l proportional to \({\tilde{V}}_{0}(k,{k}^{{\prime} })\) because \({\tilde{V}}_{0}(k,{k}^{{\prime} })\) it is positive definite.

Within the two-band model of ref. 39 giving rise to dispersion Eq. (1), the wavefunction is of the form \(\left\vert u({{{\bf{k}}}})\right\rangle=(1,\lambda {e}^{4i{\varphi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}})\), so that α4 ∝ λ is the leading order correction in Eq. (14). Thus, in Eq. (16) for the condensation energy, the corrections for j = ±1 pairing are proportional to the angular harmonics \({\tilde{V}}_{3}\) and \({\tilde{V}}_{5}\), respectively, which lifts the degeneracy between the two chiralities. In SM section E, we calculate the critical temperature for l = ±1 pairing, including the 4π Berry phase from the model of ref. 39 without trigonal warping, and find a difference in critical temperature of around 20%.

Discussion

We have shown that a strong-coupling chiral p-wave superconducting state may emerge from charge fluctuations due to Coulomb repulsion in a spin- and valley-polarized state in multilayer graphene. The superconducting transition occurs at low density over a range of displacement fields where the band bottom is flat on the scale of the Fermi energy. In this range, increasing displacing field induces a Lifshitz transition from simply-connected to annular Fermi sea occurs which also marks a phase transition from a topological to a trivial superconducting state. The chirality of the Bloch wave functions, which is responsible for the Berry curvature, selects the chirality of the p-wave superconducting order parameter.

Our obtained critical temperature and density range is in rough agreement with a recent experiment in tetralayer graphene16. In the experiment, quantum oscillations and anomalous Hall conductance measurements indicate the spin- and valley polarization. Superconductivity emerges in a region which does not show clear quantum oscillations, which indicates a large density of states (effective mass) in the relevant density range, consistent with our theoretical picture, see Fig. 3a, b.

We also speculate that a charge-ordered state may appear very close to the Lifshitz transition at low density, where the density of states and the ratio of interaction to kinetic energy are the largest. In this scenario, the ordered state divides the superconducting region into two domes. A similar feature has been observed in the experiment16.

We expect that our mechanism may also apply to isospin-polarized phases of rhombohedral graphene with a different number of layers because all these systems share the feature of a large density of states at the band bottom under an applied displacement field23. Crucially, calculations of ref. 23 indicate that tetralayer graphene reaches a significantly larger density of states close to the band bottom under a displacement field compared to a smaller number of layers. ref. 23 also demonstrates that the isospin polarization emerges in a Stoner model due to a large density of states and strong interaction. Our theory shows that the large density of states induces a short Thomas-Fermi screening length that enables superconductivity from repulsion via overscreened Friedel oscillations. This significant quantitative difference may explain why superconductivity has been observed in rhombohedral tetralayer and pentalayer graphene16, but not for smaller layer numbers up to now.

Related, we remark that multilayer rhombohedral graphene under a displacement field exhibits a larger density of states close to the band bottom in the conduction compared to the valence band23, which favors the charge-fluctuation mechanism for superconductivity in the conduction but not in the valence band.

The RPA is expected to be qualitatively correct, but corrections beyond RPA are expected to significantly alter the quantitative predictions because of the absence of Migdal’s theorem58 for superconductivity from screened electron-electron repulsion59. Different corrections contribute to an enhancement or reduction of Tc. A detailed study of corrections beyond RPA is left for future work.

Alternative mechanisms for superconductivity in an isospin-polarized metal include phonons and fluctuations of the isospin polarization. We assume that the superconductivity develops on top of a fully spin- and valley-polarized state, which is in line with experimental observation. For such a case, the Pauli principle requires the superconducting state to be odd-parity. However, phonons typically lead to an isotropic attraction that favors the s-wave channel and is averaged out for higher angular momenta, and thus, we expect that this is likely not an important mechanism for pairing for the system considered here. Fluctuations of the isospin order parameter can indeed mediate strong pairing in the proximity to the phase transition in the isospin order28,36,60,61. We remark that these fluctuations are not present in the fully polarized phase that we consider here.

We note that, besides possible suppression of a charge-ordered competing state, screening from metallic gates becomes relevant to the superconducting state only when the distance to the metallic gates becomes of the order of ℓTF. Because typical distances to metallic fields in experiment are of order 30 nm, much larger than the typical ℓTF ≈ 1 to 2 nm obtained from our calculations, gate-screening is irrelevant to the superconducting state. Only when reducing the gate distance to the order of ℓTF, the superconducting order gets suppressed, see SM section F for details.

Finally, we note that the intravalley pairing implies a large Cooper pair momentum of ±2K, which is commensurate with the lattice20,62,63,64,65,66,67,68. We also verified that our mechanism strongly favors p-wave pairing over higher angular momenta, see SM section G.

Note added: During the final stages of writing of the current manuscript, ref. 69 appeared, where a charge fluctuation mechanism for p-wave superconductivity in rhombohedral graphene has been discussed as well.

Data availability

The numerical data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17647995. All numerical data was created from the code contained in the Zenodo and GitHub repository.

Code availability

The code used to compute the numerical results presented in this work is available in the GitHub repository https://github.com/mg607/SpinPolarizedSuperconductivity.jl. The version published with this article is released at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17707778.

References

Kallin, C. & Berlinsky, J. Chiral superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 054502 (2016).

Read, N. & Green, D. Paired states of fermions in two dimensions with breaking of parity and time-reversal symmetries and the fractional quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 61, 10267–10297 (2000).

Sato, M. & Ando, Y. Topological superconductors: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 076501 (2017).

Maeno, Y. et al. Superconductivity in a layered perovskite without copper. Nature 372, 532–534 (1994).

Aoki, D. et al. Unconventional Superconductivity in Heavy-Fermion UTe2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 88, 043702 (2019).

Jiao, L. et al. Chiral superconductivity in heavy-fermion metal UTe2. Nature 579, 523–527 (2020).

Aoki, D. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in UTe2. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 34, 243002 (2022).

Kallin, C. & Berlinsky, A. J. Is Sr2RuO4 a chiral p-wave superconductor? J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 164210 (2009).

Mackenzie, A. P., Scaffidi, T., Hicks, C. W. & Maeno, Y. Even odder after twenty-three years: the superconducting order parameter puzzle of Sr2RuO4. npj Quantum Mater. 2, 1–9 (2017).

Rømer, A. T., Scherer, D. D., Eremin, I. M., Hirschfeld, P. J. & Andersen, B. M. Knight shift and leading superconducting instability from spin fluctuations in Sr2RuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 247001 (2019).

Kivelson, S. A., Yuan, A. C., Ramshaw, B. & Thomale, R. A proposal for reconciling diverse experiments on the superconducting state in Sr2RuO4. npj Quantum Mater. 5, 1–8 (2020).

Røising, H. S., Wagner, G., Roig, M., Rømer, A. T. & Andersen, B. M. Heat capacity double transitions in time-reversal symmetry broken superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 106, 174518 (2022).

Ajeesh, M. O. et al. Fate of time-reversal symmetry breaking in UTe2. Phys. Rev. X 13, 041019 (2023).

Azari, N. et al. Absence of spontaneous magnetic fields due to time-reversal symmetry breaking in bulk superconducting UTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 226504 (2023).

Andersen, B. M., Kreisel, A. & Hirschfeld, P. J. Spontaneous time-reversal symmetry breaking by disorder in superconductors. Front. Phys. 12, 1353425 (2024).

Han, T. et al. Signatures of chiral superconductivity in rhombohedral graphene. Nature 643, 654–661 (2025).

Zhou, H., Xie, T., Taniguchi, T., Watanabe, K. & Young, A. F. Superconductivity in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Nature 598, 434–438 (2021).

Chou, Y.-Z., Wu, F., Sau, J. D. & Das Sarma, S. Acoustic-phonon-mediated superconductivity in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 187001 (2021).

Ghazaryan, A., Holder, T., Serbyn, M. & Berg, E. Unconventional superconductivity in systems with annular Fermi surfaces: application to rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 247001 (2021).

Li, T., Geier, M., Ingham, J. & Scammell, H. D. Higher-order topological superconductivity from repulsive interactions in kagome and honeycomb systems. 2D Mater. 9, 015031 (2021).

You, Y.-Z. & Vishwanath, A. Kohn-Luttinger superconductivity and intervalley coherence in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 105, 134524 (2022).

Chatterjee, S., Wang, T., Berg, E. & Zaletel, M. P. Inter-valley coherent order and isospin fluctuation mediated superconductivity in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–10 (2022).

Ghazaryan, A., Holder, T., Berg, E. & Serbyn, M. Multilayer graphenes as a platform for interaction-driven physics and topological superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 107, 104502 (2023).

Jimeno-Pozo, A., Sainz-Cruz, H., Cea, T., Pantaleón, P. A. & Guinea, F. Superconductivity from electronic interactions and spin-orbit enhancement in bilayer and trilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 107, L161106 (2023).

Qin, W. et al. Functional renormalization group study of superconductivity in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 146001 (2023).

Pantaleón, P. A. et al. Superconductivity and correlated phases in non-twisted bilayer and trilayer graphene. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 304–315 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Charge fluctuations, phonons, and superconductivity in multilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 108, 045404 (2023).

Dong, Z., Levitov, L. & Chubukov, A. V. Superconductivity near spin and valley orders in graphene multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 108, 134503 (2023).

Dong, Z., Lantagne-Hurtubise, É. & Alicea, J. Superconductivity from spin-canting fluctuations in rhombohedral graphene. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2406.17036 (2024).

Murshed, S. A. & Roy, B. Nodal pair density waves from a quarter-metal in crystalline graphene multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 112, 085121 (2025).

Zhou, H. et al. Isospin magnetism and spin-polarized superconductivity in Bernal bilayer graphene. Science 375, 774–778 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Enhanced superconductivity in spin–orbit proximitized bilayer graphene. Nature 613, 268–273 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Tunable superconductivity in electron- and hole-doped Bernal bilayer graphene. Nature 631, 300–306 (2024).

Cea, T., Pantaleón, P. A., Phong, Vx-T.-j. & Guinea, F. Superconductivity from repulsive interactions in rhombohedral trilayer graphene: a Kohn-Luttinger-like mechanism. Phys. Rev. B 105, 075432 (2022).

Chou, Y.-Z., Wu, F., Sau, J. D. & Das Sarma, S. Acoustic-phonon-mediated superconductivity in Bernal bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 105, L100503 (2022).

Dong, Z., Chubukov, A. V. & Levitov, L. Transformer spin-triplet superconductivity at the onset of isospin order in bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 107, 174512 (2023).

Sigrist, M. & Ueda, K. Phenomenological theory of unconventional superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 63, 239–311 (1991).

Koshino, M. & McCann, E. Trigonal warping and Berry’s phase Nπ in ABC-stacked multilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 80, 165409 (2009).

Slizovskiy, S., McCann, E., Koshino, M. & Fal’ko, V. I. Films of rhombohedral graphite as two-dimensional topological semimetals. Commun. Phys. 2, 1–10 (2019).

Rytova, N. S. The screened potential of a point charge in a thin film. Moscow University Phys. Bulletin 22, 30–37 (1967).

Keldysh, L. V. Coulomb interaction in thin semiconductor and semimetal films. Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett. 29, 658 (1979).

Cudazzo, P., Tokatly, I. V. & Rubio, A. Dielectric screening in two-dimensional insulators: Implications for excitonic and impurity states in graphane. Phys. Rev. B 84, 085406 (2011).

Quintela, M. F. C. M., Henriques, J. C. G., Tenório, L. G. M. & Peres, N. M. R. Theoretical methods for excitonic physics in 2D materials. Phys. Status Solidi B 259, 2200097 (2022).

Kohn, W. & Luttinger, J. M. New mechanism for superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 15, 524–526 (1965).

Chubukov, A. V. Kohn-Luttinger effect and the instability of a two-dimensional repulsive Fermi liquid at T = 0. Phys. Rev. B 48, 1097–1104 (1993).

Maiti, S. & Chubukov, A. V. Superconductivity from repulsive interaction. AIP Conf. Proc. 1550, 3–73 (2013).

Berezinskii, V. L. Destruction of long-range order in one-dimensional and two-dimensional systems having a continuous symmetry group I. classical systems. Sov. Phys. JETP 32, 493–500 (1971).

Kosterlitz, J. M. & Thouless, D. J. Ordering, metastability and phase transitions in two-dimensional systems. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 6, 1181 (1973).

Halperin, B. I. & Nelson, D. R. Resistive transition in superconducting films. J. Low. Temp. Phys. 36, 599–616 (1979).

Geier, M., Brouwer, P. W. & Trifunovic, L. Symmetry-based indicators for topological Bogoliubov–de Gennes Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. B 101, 245128 (2020).

Kitaev, A. Y. Unpaired Majorana fermions in quantum wires. Phys. -Usp. 44, 131 (2001).

Drummond, N. D. & Needs, R. J. Phase diagram of the low-density two-dimensional homogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 126402 (2009).

Tanatar, B. & Ceperley, D. M. Ground state of the two-dimensional electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 39, 5005–5016 (1989).

Rapisarda, F. & Senatore, G. Diffusion Monte Carlo study of electrons in two-dimensional layers.Aust. J. Phys. 49, 161–182 (1996).

Spivak, B. & Kivelson, S. A. Phases intermediate between a two-dimensional electron liquid and Wigner crystal. Phys. Rev. B 70, 155114 (2004).

Monarkha, Yu. P. & Syvokon, V. E. A two-dimensional Wigner crystal (Review Article). Low. Temp. Phys. 38, 1067–1095 (2012).

Xiao, D., Chang, M.-C. & Niu, Q. Berry phase effects on electronic properties. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1959–2007 (2010).

Migdal, A. B. Interaction between electrons and the lattice vibrations in a normal metal. Zhur. Eksptl’. I Teoret. Fiz http://83.149.229.155/cgi-bin/dn/e_007_06_0996.pdf (1958).

Takada, Y. s- and p-wave pairings in the dilute electron gas: superconductivity mediated by the Coulomb hole in the vicinity of the Wigner-crystal phase. Phys. Rev. B 47, 5202–5211 (1993).

Fay, D. & Appel, J. Coexistence of p-state superconductivity and itinerant ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. B 22, 3173–3182 (1980).

Löhneysen, H. V., Rosch, A., Vojta, M. & Wölfle, P. Fermi-liquid instabilities at magnetic quantum phase transitions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 1015–1075 (2007).

Fulde, P. & Ferrell, R. A. Superconductivity in a strong spin-exchange field. Phys. Rev. 135, A550–A563 (1964).

Larkin, A. I. & Ovchinnikov, Y. N. Nonuniform state of superconductors. Zh. Eksperim. I Teor. Fiz https://www.osti.gov/biblio/4653415 (1964).

Roy, B. & Herbut, I. F. Unconventional superconductivity on honeycomb lattice: theory of Kekule order parameter. Phys. Rev. B 82, 035429 (2010).

Tsuchiya, S., Goryo, J., Arahata, E. & Sigrist, M. Cooperon condensation and intravalley pairing states in honeycomb Dirac systems. Phys. Rev. B 94, 104508 (2016).

Hsu, Y.-T., Vaezi, A., Fischer, M. H. & Kim, E.-A. Topological superconductivity in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 8, 14985 (2017).

Li, T., Ingham, J. & Scammell, H. D. Artificial graphene: Unconventional superconductivity in a honeycomb superlattice. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043155 (2020).

Scammell, H. D., Ingham, J., Geier, M. & Li, T. Intrinsic first- and higher-order topological superconductivity in a doped topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B 105, 195149 (2022).

Chou, Y.-Z., Zhu, J. & Sarma, S. D. Intravalley spin-polarized superconductivity in rhombohedral tetralayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 111, 174523 (2025).

Bezanson, J., Edelman, A., Karpinski, S. & Shah, V. B. Julia: a fresh approach to numerical computing. SIAM Rev. https://epubs.siam.org/doi/10.1137/141000671 (2017).

Acknowledgments

We thank Long Ju, Tonghang Han, Paco Guinea, Tommaso Cea, Erez Berg, Zhiyu Dong and Andrea Young for helpful discussions. This work was supported by a Simons Investigator Award from the Simons Foundation. M.G. acknowledges support from the German Research Foundation under the Walter Benjamin program (Grant Agreement No. 526129603). M.D. was supported in part by the Walter Burke Institute for Theoretical Physics at Caltech. L.F. was supported in part by the U.S. Army DEVCOM ARL Army Research Office through the MIT Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies under Cooperative Agreement number W911NF-23-2-0121. The numerical calculations were performed using the Julia programming language70.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G. and M.D. performed the analytical and numerical calculations. L.F. initiated and supervised the project. All authors contributed to the theoretical analysis and the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geier, M., Davydova, M. & Fu, L. Chiral and topological superconductivity in isospin polarized multilayer graphene. Nat Commun 17, 232 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66902-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66902-6

This article is cited by

-

Finite-momentum superconductivity from chiral bands in twisted MoTe2

Nature Communications (2026)