Abstract

Physiologically relevant increases in transcription factor dosage and their role in development and disease remain largely unexplored. Genomic deletions upstream of the Paired-like homeodomain transcription factor gene (PITX2), identified in patients with sinus node dysfunction and atrial fibrillation and modeled in mice (delB), rewire the local epigenetic landscape, increasing PITX2 expression. Here, we demonstrate that pacemaker cardiomyocytes in the embryonic delB sinus node ectopically express PITX2 at physiological dosages in a heterogeneous pattern. The prenatal delB sinus node forms discrete subdomains showing PITX2 dosage-dependent mild or severe loss of pacemaker cardiomyocyte identity. Respective subdomain sizes and severity of sinus node dysfunction and atrial arrhythmia susceptibility align with PITX2 dosage. Ectopic PITX2c expression in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived pacemaker cardiomyocytes causes PITX2 dosage-dependent transcriptional and electrophysiological changes paralleling those in delB mice. Our findings provide a mechanistic link between genetic variation–driven ectopic PITX2 expression, sinus node dysfunction and atrial arrhythmogenesis, illustrating how spatiotemporally defined increases in transcription factor dosage can translate into developmental defects and disease predisposition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tissue-specific transcription factors (TFs) play a crucial role in regulating transcription by interacting with specific DNA sequences within non-coding regulatory DNA elements. Their function is often dosage-sensitive and spatiotemporally restricted, driving cellular states and developmental trajectories1,2. Consistently, a reduction in TF levels (haploinsufficiency) is strongly associated with disease and loss-of-function variants are rarely found in the general population3. Genome-wide association studies have revealed thousands of trait-associated variants in regulatory elements that likely alter TF binding sites4,5,6, subtly influencing target gene expression levels per allele7,8. Enrichment of these trait-associated variants around genes encoding TFs further indicates that subtle variations in TF dosage strongly contribute to trait variation. While minor variation in TF levels may lead to trait variation, larger dosage reductions can lead to severe developmental disorders9. The impact of reduced TF dosage on gene regulatory networks and development has been studied in hypomorphic, haploinsufficient or knockout cell or animal models10,11,12,13,14,15,16. However, trait- and disease-associated variants have been associated with both increased and decreased gene expression at similar frequencies and several genomic deletions or translocations lead to gain in expression and developmental defects17,18,19. The mechanistic understanding of how increased TF expression within trait-relevant dosages affects cellular processes remains limited and requires further investigation20.

The paired-like homeodomain TF PITX2 is a downstream driver of the Nodal left-right asymmetry pathway and is required for development of several organ systems, including the heart21,22,23. During development, Pitx2c is selectively expressed in the left-sided components of the heart, including the left atrium, not in the right atrium or sinus node (SAN). Pitx2c-deficient mouse models have revealed that Pitx2c is required to impose left identity on the sinus venosus and atrium. This prevents left-sided SAN formation and SAN-associated gene expression by largely unexplored mechanisms24,25,26.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) upstream of PITX2 are strongly associated with atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common cardiac arrhythmia, yet the mechanisms that link PITX2 to AF are not fully understood27,28,29,30. AF is characterized by rapid, irregular ectopic electrical activation in the atria or pulmonary vein, which disrupts the regular pacing of the atria by the SAN and increases risk for multiple adverse outcomes, including heart failure and stroke31. The major limitations of current therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring sinus rhythm or maintaining ventricular rate include their potential toxicity and proarrhythmic risk32. A deeper understanding of AF etiology is necessary for atria-specific interventions and those that target the underlying pathophysiology of AF. It is generally assumed that AF-associated SNPs reduce PITX2 expression, possibly in addition to that of other (non) coding genes nearby, in left atrial (LA) or pulmonary vein tissue33,34. In accordance, Pitx2 haploinsufficiency or deletion of an enhancer region required for Pitx2 expression in the left atrium promotes an arrhythmogenic phenotype in mice10,25,35,36,37,38. Moreover, PITX2 loss-of-function in human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived atrial cardiomyocyte (CM)-like cells induces an AF-prone state39,40.

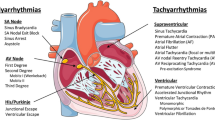

Despite this, previous investigations associate AF with reduced PITX2 expression in human left atrial samples, increased right atrial expression, or no association with AF29,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47, demonstrating that the relation between variants, direction and location of modified PITX2 expression and AF is only partially understood. Recently, the AF-associated SNPs upstream of PITX2 have been associated with SAN dysfunction (SND)48, and also with AF driven by triggers originating from the sinus venosus (where the SAN is localized)49. In SND, the activation of the atria by the SAN is impaired due to impaired function of specialized pacemaker CMs (PCs) or propagation of the action potential (AP) to the atrial myocardium50. These observations indicate that a common genetic component underlies the co-occurrence of SND and AF51,52.

We have previously identified 7 unrelated families with overlapping deletions in the gene desert 1 Mbp upstream of PITX2, in which affected members present with SND and AF50. Mice homozygous for a deletion of the paralogous region (delB) recapitulated this arrhythmogenic phenotype. Pitx2 was induced in the adult delB SAN region and in hiPSC-derived CMs homozygous for the deletion found in one of the families, which may account for the observed arrhythmias. Here, we sought to understand the mechanism linking increases in PITX2 dosage and the observed predisposition for SND and atrial arrhythmias (AA). We examined and quantified the spatiotemporal pattern of ectopic PITX2 expression and the transcriptional states, morphogenesis and function of the SAN and atria of delB mice. Furthermore, we ectopically expressed PITX2c in hiPSC-derived PC-like cells, defined PITX2 dosage-dependent transcriptional state changes and assessed how these changes modify PC electrophysiology. Our results show that PITX2 mis-expression results in altered transcriptional and functional PC state, SND and atrial arrhythmogenesis in a dosage-dependent manner, revealing how spatiotemporally defined increases in TF dosage translate into developmental defects and disease predisposition.

Results

Early onset of ectopic PITX2 expression in delB PCs

Previously, we reported that adult homozygous delB/delB mice exhibit transcriptome changes and ectopic Pitx2 expression in right atrial (RA) tissue that included the SAN region50. We investigated the location and developmental onset of Pitx2 expression in the delB hearts and the cell-type(s) involved. Ectopic Pitx2c expression was detected by in situ hybridization in the delB/delB SAN as early as embryonic day (E)10.5, when SAN morphogenesis has just been initiated (Fig. 1a). In contrast, the RA and other Pitx2-negative tissues, such as the right side of the atrioventricular canal53 did not show ectopic expression. Immunostaining further revealed co-expression of ISL1 and PITX2 in the differentiating PCs of the E10.5 delB/delB SAN (Fig. 1b). Heterozygous delB/+ embryos display ectopic Pitx2 expression in the SAN only, in a pattern very similar to that of delB/delB embryos (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1a). In wild-type fetal hearts, PITX2 expression is restricted to the myocardium of the superior caval vein, left atrium and pulmonary vein24 (Fig. 1d). However, we noted sporadic PITX2+ nuclei in the core of the SAN, revealing that Pitx2 is sometimes activated in the SAN (Supplementary Fig. 1c). In addition, we observed PITX2+ nuclei in the SAN head domain in continuity with and extending from the PITX2+ superior caval vein myocardium. In both the delB/+ and delB/delB SAN, a large fraction of PCs express PITX2, coinciding with a reduction in the proportion of PCs that express ISL1 (Fig. 1d). We conclude that while PITX2+ PCs infrequently occur in the wild-type SAN, the topological disruption associated with delB induces exaggerated and heterogeneous ectopic expression of PITX2 in PCs from the onset of SAN development.

a In situ hybridization reveals absence of Pitx2 expression at E10.5 in the wild-type SAN (n = 3) and early ectopic Pitx2 expression in the SAN alongside maintained expression in the LA, prPV, and AVC (arrow) delB/delB heart (n = 4). Scale is 200 μm. b Immunostaining shows absence of PITX2+ nuclei in the ISL1+ wild-type SAN (n = 3) and PITX2+ nuclei alongside ISL1+ nuclei in the delB/delB SAN (n = 3) at E10.5. Scale is 100 μm. Insets show co-localization of ISL1 and PITX2 expression in the delB/delB SAN. Scale is 10 μm. c In situ hybridization shows that Pitx2 clearly demarcates the left from the RA and is normally absent from the SAN (n = 2). Scale is 200 μm. Pitx2 is ectopically expressed in the delB/+ (n = 3) and delB/delB (n = 2) SAN (outlined) at E12.5. Scale is 100 μm. d Immunostaining shows that PITX2 expression is normally restricted to the SVC and LA and absent from the ISL1+ SAN (n = 3). Ectopic PITX2 expression in the delB/+ (n = 3) and delB/delB (n = 7) SAN (outlined) is heterogeneous and coincides with a loss of ISL1 expression by the end of gestation at E17.5. Scale is 200 μm and 100 μm. SAN sinus node, RA right atrium, LA left atrium, prPV primordial pulmonary vein, AVC atrioventricular canal, E embryonic day, RV right ventricle, LV left ventricle, SCV superior caval vein.

Progressive loss of pacemaker-associated gene expression in the delB SAN

In the E12.5 Pitx2+ delB/delB SAN, 3 days following the initiation of SAN formation, we observed reduced PC nuclear expression of TFs required for PC differentiation, ISL154, TBX355, and SHOX256,57 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1b). The expression of HCN4, a PC-specific ion channel responsible for phase 4 depolarization, essential for pacemaker function and embryogenesis58, remained largely unchanged at this stage (Fig. 2a). The E14.5 SAN also showed reduced ISL1, TBX3 and SHOX2 expression, which was now accompanied by the induction of NKX2-5 expression in the SAN head periphery (Fig. 2b). This indicates that NKX2-5 expression is no longer suppressed by SHOX259. Furthermore, we detected clusters of CMs in the SAN exhibiting strongly reduced HCN4 expression and ectopic CX40 expression (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2a). By the end of gestation, at E17.5, we detected two distinct PC subdomains in both the delB/+ and delB/delB SAN, HCN4low subdomains that that lack PC-associated gene expression (including ISL1, SHOX2, TBX3 and HCN4) alongside seemingly unaffected HCN4high subdomains (Fig. 2c, d and Supplementary Fig. 2b). In situ hybridization of adjacent sections reveals concomitant loss of Hcn4 and gain of Gja5 in the SAN at E17.5 (Supplementary Fig. 1d). 3D volumetric reconstruction showed that the volume of the Hcn4+ SAN domain was strongly reduced in delB/delB fetal mice compared to wild-type mice (n = 5 and 8, respectively; p = 0.0086) (Supplementary Fig. 1e, f). In summary, delB and the consequent ectopic activation of PITX2 expression in the SAN PCs correlate with two distinct PC states resulting from the progressive loss of essential pacemaker TF expression and their target genes and a gain in gene expression associated with the atrial myocardium (Fig. 2e).

a ISL1 is normally expressed in PCs throughout the SAN (outlined) at E12.5 (n = 5). Loss of ISL1 expression was detected as early as E12.5 in the delB/delB (n = 5) SAN (arrows). The expression domain of downstream functional markers HCN4 (pacemaker marker) and CX40 (working atrial myocardium marker) remain unchanged (wild-type, n = 5; delB/delB, n = 4). Scale is 100 μm. b Immunostainings show progressive loss of ISL1 and HCN4 (wild-type, n = 2; delB/delB, n = 3 alongside activation of NKX2-5 and CX40 expression (arrows) in the E14.5 SAN domain (outlined, wild-type, n = 2; delB/delB, n = 2). Scale is 100 μm. c Clusters of TNNI3+ cardiomyocytes in the SAN domain that have lost upstream (SHOX2) and downstream (HCN4) pacemaker gene expression by the end of gestation (E17.5, arrows) (wild-type, n = 3; delB/delB, n = 3). Scale is 100 μm. d Adjacent sections show co-localization of ISL1 and TBX3 expression with HCN4 in the wild-type SAN at E17.5 (n = 2). Clusters of TNNI3+ cells in the delB/delB SAN lack ISL1, TBX3 (n = 3) and HCN4 expression and express CX40 (panel, n = 4). Scale is 100 μm and panel scale is 10 μm. e Pacemaker-associated or working myocardium-associated gene expression is the product of a gene regulatory network. This gene regulatory network is progressively disrupted in the delB/delB SAN. Red arrows repress, and blue arrows drive. PC pacemaker cardiomyocyte, SAN sinus node, E embryonic day, RA right atrium, SCV superior caval vein, CM cardiomyocyte.

The activation of Pitx2 expression during SAN development may have caused the replacement of PCs by other cell types. However, the progressive loss of expression of PC-associated genes, like Hcn4, over the course of delB SAN development indicates that PITX2 expression causes differentiating PCs to change state. To determine whether PITX2 can cause a state change in fully differentiated post-mitotic PCs, we used AAV9-Myo4A expression vectors to overexpress PITX2c or mCherry in wild-type mice 2 days after birth (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Immunostaining for PITX2, GFP and CM-specific PCM-1 confirmed high transduction efficiency in the myocardium, including the SAN (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Both HCN4 and ISL1 expression was depleted in PITX2+ cells in the AAV9-PITX2c SAN (Supplementary Fig. 3d), demonstrating that ectopic PITX2 expression in differentiated PCs suppresses PC gene expression.

A unique transcriptional profile in PITX2+ PCs

To define the transcriptomes of the differentially affected HCN4high and HCN4low PC subdomains in the late fetal (E17.5) delB/delB SAN, also in relation to the RA, we applied spatial transcriptomics on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of wild-type (n = 3) and delB/delB (n = 6) hearts. Transcripts were detected using the GeoMx Whole Transcriptome Mouse Atlas Probe mix for NGS, containing probes for 19966 unique gene transcripts. We immunolabeled sections for TNNI3 to enrich for CMs and HCN4, which clearly demarcated the boundaries between HCN4high and HCN4low PCs, to segment regions of interest (ROIs) based on HCN4 and TNNI3 signal intensity. In doing so, we determined ROIs containing the wild-type HCN4+ TNNI3+ SAN PCs and TNNI3+ RA CMs, as well as the delB/delB HCN4high and HCN4low TNNI3+ SAN PCs and TNNI3+ RA CMs (Fig. 3a). We determined that all ROIs contained sufficient cells for reliable transcript quantification (Supplementary Data 14).

a Local changes in gene expression in the delB/delB SAN head and RA were defined for spatial transcriptomics by segmenting regions of interest based on HCN4 and TNNI3 expression in wild-type (n = 3) and delB/delB (n = 6) fetal (E17.5) hearts. Scale is 1 mm and 100 µm. b Principal component analysis shows that the delB/delB fetal RA is transcriptionally unaffected. HCN4low and HCN4high subdomains in the delB/delB SAN have distinct gene expression profiles and both are transcriptionally distinct from the wild-type HCN4+ SAN. c Comparing the expression of genes surrounding the gene desert on chromosome 4q25 to that of the wild-type SAN or RA reveals that Pitx2 is significantly differentially expressed in the delB/delB HCN4high (padj = 0.002) and HCN4low (padj = 5.4E-7) subdomain compared to the wild-type SAN. More Pitx2 was detected in the HCN4low subdomains than HCN4high subdomains (p = 0.047). Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. d Comparing the expression of relevant PC and working atrial myocardium markers in the delB/delB SAN and RA with that of the wild-type SAN or RA, respectively, reveals step-wise changes in gene expression in the HCN4high and HCN4low delB/delB subdomains. The delB/delB RA is transcriptionally unaffected. Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. e Gene ontology analysis on the up- and down-regulated genes in the delB/delB HCN4low vs wild-type HCN4+ SAN. f Heatmap generated following a cluster analysis comparing the wild-type HCN4+ SAN with the delB/delB HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains and the wild-type and delB/delB RA. While the delB/delB SAN transcriptome does acquire certain aspects of the RA transcriptome (clusters 1 and 3), clusters 2 and 4 suggest that these cells acquire a unique identity that is dissimilar from that found in the RA. g Several key transcription factors and ion handling genes are significantly differentially expressed in delB/delB HCN4low cells (padj < 0.05). *(p < 0.05). Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. h Scatterplot showing that the delB/delB HCN4low domain is similarly, but more severely affected than the delB/delB HCN4high domain, compared to the wild-type HCN4+ SAN. Purple dots indicate genes that are significantly deregulated (p < 0.001) in both the delB/delB HCN4low domain and the HCN4high domain compared to the wild-type HCN4+ SAN. Exact p and padj values, L2FC, fold enrichment and FDR values are listed in Supplementary Data 1–6. Source data are provided in the Source Data file. SAN sinus node, RA right atrium, E embryonic day, L2FC Log2Fold-change, FDR false discovery rate.

Principal component analysis (PCA) captured the distinct transcriptional profiles of the RA and SAN and those of the wild-type HCN4+ SAN and delB/delB HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains (Fig. 3b). Comparing delB/delB with wild-type fetal RA confirmed that the RA is transcriptionally unaffected and that Pitx2 is not expressed in the RA (Fig. 3b–d). Both delB/delB HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains were transcriptionally distinct from the wild-type HCN4+ SAN (108 upregulated and 87 downregulated transcripts; padj < 0.05 and 286 upregulated and 274 downregulated transcripts; padj < 0.05, respectively) and from each other (122 upregulated and 101 downregulated in delB/delB HCN4low; padj < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 4a and Supplementary Data 1–3). The expression of genes in a 3.5 Mbp region surrounding the delB deletion was unchanged in the delB/delB SAN and RA, except for Pitx2 in the delB/delB SAN (Fig. 3c). Comparing the wild-type HCN4+ SAN to the delB/delB HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains revealed a significant stepwise increase in Pitx2 dosage from negligible in the wild-type SAN to increasingly higher levels in the delB/delB HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains, respectively (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Data 1–3). Pacemaker markers Isl1, Tbx3, Shox2, and Hcn4 showed a reciprocal stepwise reduction, whereas atrial CM markers Gja1 and Scn5a showed a stepwise increase in the delB/delB HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Data 1–3). Interestingly, the expression of Scn5a (encoding the alpha subunit of the cardiac sodium channel essential for conduction and implicated in SND and AF60,61,62,63) in the delB/delB HCN4low subdomain increased to levels beyond those normally found in the atrial working myocardium (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Data 1–3). Tbx5, encoding a TF required for formation of the atria and SAN64 remained unchanged (Fig. 3d). Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed downregulation of terms associated with PC identity/function (e.g., sinoatrial node development (GO:0003163) and regulation of heart rate (GO:0002027)) and the upregulation of terms associated with the working atrial myocardium (e.g., atrial cardiac muscle cell action potential (GO:0086014) and cell communication by electrical coupling involved in cardiac conduction (GO:0086064)) (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Data 1–3).

Cluster analysis comparing gene expression in wild-type HCN4+ SANs, delB/delB HCN4high subdomains, HCN4low subdomains and wild-type and delB/delB RAs shows that delB PCs acquire features more similar to atrial CMs while also gaining unique characteristics (Fig. 3f). Clusters 1 and 2 show a stepwise enrichment for RA-expressed transcripts, whereas clusters 3 and 4 show a stepwise depletion of SAN-expressed transcripts (clusters 3 and 4) in the delB subdomains (Fig. 3f). GO analysis shows that differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in cluster 1 are linked with heart morphogenesis and development, while cluster 3 DEGs are associated with SAN development and heart rate regulation (Supplementary Fig. 4b and Supplementary Data 5). Clusters 2 and 4 show stepwise changes in gene expression beyond RA levels (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Data 5). GO analysis shows that cluster 2 DEGs are associated with metabolism, muscle contraction and sarcomere organization (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Data 5).

Genes encoding all TFs previously implicated in the development and function of the SAN (Gata665, Shox256, Tbx1866, Isl154, Tbx355, Hand267) were downregulated in delB/delB HCN4low subdomains, except for Tbx2048, which was upregulated (Fig. 3g). Additionally, we find that genes that drive pacemaker activity or atrial conduction are also strongly deregulated in delB/delB HCN4low subdomains, including Hcn4, Hcn1, Scn5a, Gja1, Gja5, and Kcnj3 (Fig. 3g). Ca2+ handling plays a central role in the maintenance of PC automaticity and contractility68,69,70. Expression of key mediators of intracellular Ca2+ transport and handling in CMs is disrupted in HCN4low PCs compared to the wild-type HCN4+ SAN, including Pln, Atp2a2, Ryr2, and Calm1. Also, Mfn2, involved in the maintenance of mitochondria-sarcoplasmic reticulum interactions and implicated in SND71 is downregulated in HCN4low PCs compared to wild-type HCN4+ PCs.

Direct comparison between the delB/delB HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains revealed that HCN4high subdomains are similarly, but much less strongly transcriptionally affected compared to HCN4low subdomains (Fig. 3h). Thus, the direction of change of most significant DEGs is congruent in both subdomains, whereas only a few genes are uniquely differentially expressed in either the HCN4low or HCN4high subdomain. Additionally, comparing the degree by which gene expression changed in the HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains shows that the majority of DEGs (p < 0.001) have a stronger response in the HCN4low domain, indicating that higher PITX2 expression levels coincide with stronger transcriptional deregulation (Supplementary Fig. 4c).

We next assessed how the levels of ectopic PITX2 expression in the delB SAN compared to those of myocardium of the LA that normally expresses PITX2. We quantified PITX2 signal intensity per nucleus in equivalent sections in the wild-type SAN (n = 2; 1073 nuclei), delB/delB SAN (n = 3; 1126 nuclei), wild-type LA body (LAB) (n = 2; 4999 nuclei) and wild-type LA auricle (LAA) (n = 2; 6445 nuclei). In the wild-type LA, the LAB exhibited higher PITX2 signal than the LAA, and PITX2 signal in delB/delB SAN nuclei was intermediate to that found in the LAB and LAB (Fig. 4a). These data show that PITX2 is ectopically expressed in SAN PCs at physiological levels.

a Quantification of normalized mean gray value per nucleus in the wild-type (N = 2) SAN, LAB and LAA (1073, 4999, 6445 nuclei, respectively) and the delB/delB (N = 3; 1126 nuclei) E17.5 SAN reveals that ectopic PITX2 expression level in the delB/delB SAN is intermediate to that found in the wild-type LAB and LAA (p < 0.0001; two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). b Local changes in gene expression in the E17.5 delB/delB SAN head domain, LAB and LAA were defined for spatial transcriptomics by segmenting regions of interest based on HCN4 and TNNI3 expression in wild-type (n = 3), delB/+ (n = 6) and delB/delB (n = 3) fetal (E17.5) hearts. Principal component analysis demonstrates the distinct gene expression profile of the LAA and LAB and that the HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains in both the delB/+ and delB/delB SAN are similarly transcriptionally affected. c Normalized expression of genes of interest shows that the expression levels of pacemaker- and working myocardium-associated transcription factors and ion channels in the wild-type (n = 3), delB/+ (n = 6) and delB/delB (n = 3) SAN do not align with those in the LAA (n = 3) or LAB (n = 3). Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Exact p and padj values, and L2FC are listed in Supplementary Data 6–14. Source data are provided in the Source Data file. E embryonic day, SAN sinus node, LA left atrium, LAB left atrial body, LAA left atrial auricle, L2FC Log2Fold-change.

To compare the state of PITX2+ PCs with that of PITX2+ LA CMs, we assessed the transcriptional profiles of HCN4+ , HCN4high and HCN4low SAN subdomains, and of the LAB and LAA of wild-type (n = 3), delB/+ (n = 6) and delB/delB (n = 3) E17.5 fetal mice (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Data 6–10). PCA grouped wild-type, delB/+ and delB/delB LAB and wild-type, delB/+ and delB/delB LAA ROIs together, and the transcriptomes of these regions did not overlap with those of any SAN sample (Fig. 4b), indicating that the delB LA is transcriptionally unaffected and showing that PITX2+ PCs do not acquire a LACM-like state. Furthermore, Pitx2 expression levels in the delB SAN does not exceed physiological levels found in the LA (Fig. 4c), consistent with the PITX2 protein quantification (Fig. 4a). Comparing the transcriptomic changes in the delB/delB HCN4low subdomain with those found when comparing atrial CMs with PCs72 confirms that PITX2+ PCs acquire some aspects of atrial CM identity (Supplementary Fig. 4d). However, comparing these transcriptomic changes to those found between Pitx2 haploinsufficient LACMs and wild-type LACMs34 suggests little overlap in the response to changes in PITX2 dosage in the SAN and LA (Supplementary Fig. 4e).

PITX2 dosage, reduced ISL1 and a threshold response in delB PCs

The ectopic expression of PITX2 and reduction in ISL1 expression in both the E17.5 delB/+ and delB/delB SAN are highly heterogeneous (Fig. 1d and Fig. 5a). Although we identified two distinct PC states in the delB SAN, nuclei expressing variable levels of PITX2 and ISL1 are distributed throughout the delB SAN head in a seemingly stochastic pattern (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). To align PITX2 expression level with the loss of ISL1 expression in PCs, we quantified PITX2 and ISL1 signal intensity per nucleus in equivalent sections containing wild-type (n = 3, 224 nuclei), delB/+ (n = 3, 155 nuclei) and delB/delB (n = 3, 320 nuclei) SAN head domains. Most nuclei in the wild-type SAN were ISL1+, except for the aforementioned sporadic PITX2+ nuclei (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 5a). In the delB/+ and delB/delB SANs, signal intensities per nucleus of both ISL1 and PITX2 were distributed across a large range, with the delB/delB SANs exhibiting higher PITX2 signal intensities over a larger range (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). These data indicate a relationship between the number of delB alleles and the average level of PITX2 (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). By comparing the signal intensity of ISL1 and PITX2 in individual nuclei per genotype, we found that in wild-type, delB/+ and delB/delB SANs, the expression of PITX2 and ISL1 was negatively correlated (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 5a). Taken together, these data indicate that PITX2 dosage-dependently suppresses ISL1 in PCs.

a Fetal (E17.5) delB/delB SAN nuclei exhibit variable ISL1 and PITX2 expression levels. Scale is 100 μm and panel scale is 10 μm. b Violin plots showing the quantification of normalized mean gray value per nucleus in wild-type (N = 3; n = 223), delB/+ (N = 3; n = 176) and delB/delB (N = 3; n = 452) fetal SANs (two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p < 0.0001). There is an overall incremental gain in PITX2 and reduced ISL1 expression levels in both the delB/+ and delB/delB SAN, and a progressive shift in PITX2:ISL1 expression balance in the delB/+ and delB/delB fetal SAN towards less ISL1 and more PITX2. Red line indicates median. Two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test p < 0.0001. c Relative expression levels of genes of interest show stepwise, Pitx2-correlated changes in the expression levels of pacemaker- and working myocardium-associated transcription factors and ion channels in the delB/+ (n = 6) and delB/delB (n = 3) SAN compared to the wild-type (n = 3) SAN. Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. d Scatterplot showing the relative expression of genes in the delB/+ and delB/delB HCN4low subdomains compared to the wild-type HCN4+ SAN demonstrates that while the delB/+ HCN4low subdomains are less severely affected than their delB/delB counterparts, differentially expressed genes behave similarly. Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. e Variable PITX2 expression levels in the delB/delB HCN4high and HCN4low subdomain at E17.5. Scale is 100 μm, and panel scale is 10 μm. f Fraction of total nuclei in HCN4high and HCN4low subdomain in equivalent sections of the delB/+ (n = 6) and delB/delB (n = 6) fetal SAN head domain. Two-tailed paired T test. Source data are provided in the Source Data file. E embryonic day, SAN sinus node, L2FC Log2Fold-change.

Transcriptomes of delB/+ and delB/delB HCN4high subdomains clustered together, as well as those of delB/+ and delB/delB HCN4low subdomains, both being distinct from the transcriptome of wild-type HCN4+ SAN (Fig. 4b). The expression profiles of key marker genes confirmed the stepwise increase or decrease in the wild-type HCN4+ SAN, delB HCN4high and delB HCN4low subdomains (Fig. 5c). The direction and magnitude of the Log2Fold-change of DEGs between the wild-type HCN4+ SAN and delB/+ HCN4high subdomains and between wild-type HCN4+ SAN and delB/delB HCN4high subdomains, respectively, were equivalent, as were those between wild-type HCN4+ SAN and delB/+ HCN4low subdomains and between wild-type HCN4+ SAN and delB/delB HCN4low subdomains (Fig. 5d). These comparisons indicate that the cell state changes in the delB HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains are independent of genotype and that PCs exhibit a threshold response to PITX2 dosage.

We next quantified the fraction of PC nuclei in HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains in wild-type (n = 5), delB/+ (n = 6) and delB/delB (n = 6) fetal hearts and found that the delB/delB HCN4high subdomain contains a smaller fraction of total PC nuclei and the HCN4low subdomain contains a larger fraction of total PC nuclei compared to their respective subdomains in delB/+ SANs (Fig. 5e, f). This indicates that the higher average PITX2 levels in delB/delB PCs compared to delB/+ PCs translate to substantially larger fraction of strongly affected PCs (HCN4low) in the delB SAN.

PITX2c expression in hiPSC-PCs mimics transcriptional changes in the delB SAN

Our findings in delB mice indicate a causal relationship between ectopic PITX2 expression, PC state changes in deletion carriers and SND, but do not directly address the conservation of this mechanism. To investigate these aspects, cultures of hiPSC-PCs73 were transduced with AAV6 expression vectors driving either PITX2c-p2a-H2B-EGFP or mCherry-p2a-H2B-EGFP (control) expression by the CM-specific TNNT2 promoter, followed by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) 7 days after transduction (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Flow cytometry revealed >85% transduction efficiency and expression over a wide range of levels (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Based on the expression of TNNT2, we determined that clusters 0, 1, 2, 4, 7 and 8 represented CMs (Fig. 6a, b). Cluster 0 (C0) is the largest cluster and represents PC-like cells (ISL1, SHOX2, TBX3, HCN4, RGS4, NKX2-5low) while C1 represents atrial-like CMs (NPPA, NPPB), C2 ventricular-like CMs (MYL2, IRX4) and C4 CMs of a mixed subtype (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 6d). C7 expressed PC-associated markers at lower levels compared to C0 (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 6d). C8 was separated from the other clusters in the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) and was highly MALAT1 positive, indicating these cells were stressed or damaged74,75 (Supplementary Fig. 6d). C8 is disproportionally composed of AAV9-PITX2 cells, indicating that these cells may be stressed by high (supra-physiological) PITX2 levels (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Non-CM C3 expresses TBX18 and TCF21, suggesting a proepicardial-like cell state, which was also identified in previous equivalent differentiations73. C5 and C6 expressed fibroblast, endothelial and mesenchymal marker genes. As C0 and C7 represent PC-like cells and are closely associated in the UMAP, we decided to focus on these two clusters.

a UMAP representation of the single-cell transcriptomics of hiPSC-derived PCs transduced with AAV6-mCherry or AAV6-PITX2c alongside the distribution of PC and working myocardium-associated marker expression. PC C0 and C7 are outlined. b Heat-map showing the proportion of cells per cluster expressing PC and working myocardium-associated genes and the average expression of those genes per cluster. c The contribution of AAV6-mCherry (red) or AAV6-PITX2c (blue) PCs to each cluster. d Heat-map showing the distribution of EGFP expression in AAV6-mCherry and AAV6-PITX2c cells. PC C0 and C7 are outlined. e Scatterplot showing the relative expression of genes in the mouse wild-type HCN4+ SAN and delB/delB HCN4low SAN compared to that of AAV6-PITX2c PC C0 and C7 and AAV6-mCherry C0 and C7 demonstrating that the most significantly deregulated PC genes are deregulated similarly in delB mice and AAV6-PITX2c hiPSC-PCs. Purple dots indicate genes that are significantly differentially expressed (padj < 0.05) in both comparisons. Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. f Expression analysis of AAV9-PITX2c PC C0 (light blue) and C7 (dark blue) indicates a dichotomous response in AAV9-PITX2c hiPSC-PCs that correlates with PITX2c expression level. Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. g Scatterplots showing the relative expression of genes in hiPSC-PCs and the mouse SAN, indicating that C0 (PITX2) is comparable to the delB/delB HCN4high subdomain while C7 is comparable to the delB/delB HCN4low subdomain. Key affected genes behave similarly in hiPSC-PCs and the mouse SAN. Purple dots indicate genes that are significantly differentially expressed (padj < 0.05) in both comparisons. Wald test corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. h Typical examples of spontaneous activity (top panel) and the AP upstroke velocity (Vmax; bottom panel) in AAV6-mCherry (red) and AAV6-PITX2c (blue) hiPSC-PCs. i While all measured AAV6-mCherry PCs (n = 9) showed spontaneous activity, only 50% of AAV6-PITX2c PCs (n = 12) are spontaneously active (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0186). j Of the AAV6-PITX2c PCs that retained spontaneous activity (n = 6), PITX2 increased the coefficient of variation (CoV; SD/average) (two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.0004) while differences in cycle length did not reach the threshold of significance. k Dot plot showing that the MDP is lower in AAV6-PITX2c PCs (n = 6) compared to AAV6-mCherry controls (n = 9) (two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.0076). (l) Vmax (p = 0.009) and AP duration at 20% (p = 0.0033), 50% (p = 0.0009) and 90% (p = 0.0013) repolarization following Kir2.1 injection under dynamic clamp conditions (two-tailed Mann-Whitney test). AP parameters were established for 9 AAV6-mCherry control and 12 AAV6-PITX2c PCs. Exact p and padj values and L2FC values are listed in Supplementary Data 1, 2, 11 and 12. Source data are provided in the Source Data file. PC pacemaker cardiomyocyte, SAN sinus node, C cluster, CM cardiomyocyte, L2FC Log2Fold-change, AP action potential, MDP maximal diastolic potential.

We found that all established PC-enriched genes downregulated in fetal mouse delB SAN were also downregulated in AAV6-PITX2c PCs in C0 and C7 (ISL1, SHOX, TBX18, TBX3, HCN4, BMP4, PLN, RGS4, HAND2, etc.) (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Data 11–12). Moreover, several functionally relevant atrial CM genes were upregulated, including SCN5A and CLU, which were also strongly upregulated in delB SANs (Fig. 6e). The level of PITX2 across C0 and C7 cells (combined) negatively correlated with the levels of several PC genes, and positively correlated with the levels of several of the upregulated atrial genes (Supplementary Fig. 6g). While C0 is slightly enriched for AAV6-mCherry cells, C7 is enriched for AAV6-PITX2c cells (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Moreover, PITX2 is expressed at higher levels in C7 than in C0 (Fig. 6f). These data suggest that C0 and C7 represent PC-like cells that responded to PITX2 in a dosage-dependent manner. Comparing transcriptional changes of C0-PITX2c with those of C7-PITX2c revealed a transcriptome response that correlates with PITX2c expression level (Fig. 6g). The majority of PC-associated genes were more downregulated in C7-PITX2c than in C0-PITX2c, whereas atrial genes like CLU and SCN5A were more upregulated in C7-PITX2c than in C0-PITX2c. When comparing differential expression between C0-PITX2c vs C0-mCherry and C7-PITX2c vs C0-mCherry, we found that the vast majority of significantly DEGs showed the same direction of change in C0 and C7, but that the magnitude of change was larger in C7 compared to C0. Differential expression between delB/delB HCN4high subdomains vs wild-type HCN4+ SAN and HCN4low subdomains vs wild-type HCN4+ SAN, respectively, showed very similar behavior (Fig. 6g). Moreover, of many genes, including the PC-associated gene set (ISL1, SHOX2, TBX3, HCN4, PLN, etc.) and atrial genes (SCN5A, CLU), both direction of change and magnitude difference were conserved between the hiPSC-PC clusters and the delB/delB HCN4high and HCN4low subdomains. Together, our data suggest that human PCs exhibit a PITX2 dosage-dependent threshold response reminiscent of that observed in delB PCs.

To assess the electrophysiological consequences of the PITX2 dosage-dependent transcriptional state changes described above, we next performed a series of AP measurements on hiPSC-PCs transduced with AAV6-mCherry (control) or AAV6-PITX2c. First, we recorded the APs of 9 AAV6-mCherry and 12 AAV6-PITX2c PCs in unstimulated conditions. While all AAV6-mCherry hiPSC-PCs showed spontaneous activity, only 50% of AAV6-PITX2c PCs showed spontaneous activity (Fig. 6h, i). Spontaneous activity was also more variable in AAV6-PITX2c PCs, as demonstrated by the increase coefficient of variation (CoV; SD/average) (Fig. 6j). There was no significant difference in cycle length (Fig. 6j). Finally, the maximal diastolic potential (MDP) was more hyperpolarized (Fig. 6k), the maximum AP upstroke velocity (Vmax) was increased and AP duration at 90% repolarization was significantly shorter AAV6-PITX2c PCs compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 7a).

To test whether the higher Vmax AAV6-PITX2c PCs are due to the more hyperpolarized MDP or increased SCN5A expression level, we additionally measured APs elicited at 1 Hz under conditions of a Kir2.1 injection using dynamic clamp, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 7b. Using dynamic clamp, APs could be evoked in all hiPSC-PCs measured, and Fig. 7c shows representative APs (top panel) and the Vmax in AAV6-mCherry and AAV6-PITX2c PCs (bottom panel). Under dynamic clamp conditions, MDP in AAV6-PITX2c PCs was similar to that of controls (Supplementary Fig. 7d), thus the Na+ channel availability will not be affected by differences in membrane potential. Again, we observed an increased dV/dt (Fig. 6l), which is thus due to an increased expression of SCN5A. In addition, shorter APs were observed (Fig. 5l). Taken together, our patch clamp data confirm that the transcriptional state changes that occur upon ectopic PITX2c expression in hiPSC-PCs substantially alter PC electrophysiology, including PC spontaneous activity, Vmax and AP duration.

a Typical examples of ECGs of adult wild-type, delB/+ and delB/delB mice. Arrows point to the first deflection of the P-wave, indicating negative deflections and thus, ectopic activation of the atria in delB/+ and delB/delB mice. b–d Bar graphs showing the direction of the first P wave deflection (Chi-square test), RR interval and HRV (standard deviation of RR interval) in wild-type, delB/+ and delB/delB mice. (Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test). e cSNRT120 in wild-type, delB/+ and delB/delB mice; typical examples show cSNRT120 calculated from the last stimulus artifact to the first spontaneous P-wave (Ordinary one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). f Representative examples of ECG traces showing SNRT120. g Incidence (Chi-square, p < 0.05) of induced AA in wild-type, delB/+ and delB/delB mice. h Typical examples of induced AAs. Source data are provided in the Source Data file. ECGs electrocardiograms, HRV heart rate variation, AA atrial arrhythmia, cSNRT120 corrected sinus node recovery time after 120 ms pacing.

Transcriptional changes, SND and atrial arrhythmias in adult delB mice

To translate the PITX2 dosage-associated changes in SAN composition in delB/+ and delB/delB mice to cardiac function and arrhythmogenesis, we examined ECG parameters of adult wild-type, delB/+ and delB/delB mice. Several abnormal ECG phenotypes were observed at rest in both delB/+ and delB/delB mice, including alternative P wave deflections and morphologies, both with and without sinus pauses, junctional rhythms and ectopic atrial beats (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 8; Supplementary Table 1). When we compared the direction of the first P wave deflection in wild-type, delB/+ and delB/delB mice, we found that both delB/+ (n = 27) and delB/delB (n = 45) mice had negative P wave deflections more often than wild-type (n = 33) animals (p = 0.0003 and p < 0.0001, respectively). DelB/delB mice had significantly more frequent negative first P wave deflections than delB/+ mice (p = 0.0015) (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Table 1). Unlike delB/delB mice, delB/+ mice displayed neither slower heart rate nor higher heart rate variability compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 7c, d and Supplementary Table 2). Wenckebach cycl length (WBCL) was prolonged in delB/delB mice (p = 0.0146) but not in delB/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Other baseline ECG parameters, including PR interval, P and QRS duration, and QT interval of delB/+ and delB/delB mice, were unaffected compared to wild-type mice (Supplementary Table 2).

We supplied overdrive suppression to the RA through in vivo atrial stimulation using a transesophageal catheter to examine SAN recovery time (SNRT) at 120 msec stimulation cycles (SNRT120). In delB/delB mice, but not in delB/+ mice, SNRT120 was significantly prolonged compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 7e, f). Both delB/+ and delB/delB mice were more susceptible to AA upon atrial stimulation than wild-type mice (p = 0.0216 and p = 0.0361, respectively) but there was no significant difference in AA susceptibility between delB/+ and delB/delB mice (Fig. 7g, h). Total AA duration upon stimulation was comparable between genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 9b).

Atropine and propranolol were administered to block the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and test intrinsic SAN function. ANS block prolonged the RR interval, heart rate variation, WBCL and AA incidence across all genotypes but did not change the SNRT120 (Supplementary Fig. 9c–g). ANS block did not change genotype-associated ECG phenotypes, except for a greater number of delB/delB mice with a regular rhythm and single P wave shape (p < 0.05, Supplementary Table 3). ANS block did not change the genotype-dependent differences in RR interval, heart rate variation, SNRT120, AA incidence or WBCL (Supplementary Fig. 9c–g). Together, these results confirm that SND and atrial arrhythmogenesis in delB mice are both SAN-intrinsic and independent of ANS function. Notably, the milder arrhythmogenic phenotype seen in delB/+ mice compared to delB/delB mice suggests a tolerance threshold for PITX2 dosage in the SAN, beyond which SAN function is impaired.

To connect PITX2 dosage-dependent transcriptional deregulation with the arrhythmogenic phenotype in adult delB mice, we performed spatial transcriptomic analysis of the adult wild-type (n = 3), delB/+ (n = 3) and delB/delB (n = 3) TNNI3+ SAN and adjacent RA (Supplementary Fig. 10a). We were unable to discriminate between HCN4low or HCN4high subdomains due to the very weak HCN4 signal in adult heart sections. PCA clearly separated the SAN from RA samples, confirming their distinct transcriptional profiles (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Comparing the delB/delB SAN with the wild-type SAN identified 108 up- and 97 downregulated genes (p < 0.01) whereas delB/+ SAN only showed 23 DEGs (p < 0.01) relative to the wild-type SAN (Supplementary Fig. 10c and Supplementary Data 15, 16). These findings are consistent with the genotype-dependent electrophysiological changes of adult delB mice. We found that 89 genes were deregulated in both the fetal delB/delB HCN4low subdomain and the adult delB/delB SAN (p < 0.01), and the direction of change was largely consistent across datasets (Supplementary Fig. 10d). Therefore, the transcriptional changes established in delB PCs during development seem to persist into adulthood. Furthermore, while the fetal delB/delB RA (Fig. 3b–d) and adult delB/+ RA were transcriptionally unaffected (Supplementary Fig. 10e), adult delB/delB RA were affected (169 (p < 0.01) or 52 (padj < 0.05) DEGs compared to adult wild-type RA) (Supplementary Fig. 10e and Supplementary Data 17). GO analysis of the DEGs (padj < 0.05) showed enrichment for terms associated with cardiac stress (including GO:0042026 and GO:0009408; Supplementary Fig. 10f and Supplementary Data 18). Together, these data suggest that while the deregulation of PC state is initiated during development and persists into adulthood, a cardiac stress response is initiated in the adult delB/delB RA that is absent from the adult delB/+ RA and the fetal delB RA.

Discussion

Here, we investigated a mouse model, delB, that recapitulates a human cardiac arrhythmia syndrome associated with PITX250 to examine the transcriptional and functional consequences of physiologically relevant increases in TF dosage. We found that in delB mice, PITX2 is ectopically expressed in SAN PCs in a heterogeneous pattern from the onset of SAN morphogenesis onwards. Our analyses indicate that mis-expressed PITX2 alters PC state and function in a dosage-dependent manner in both delB mice and in a human PC model. PCs that express PITX2 at lower average levels acquire a mildly altered HCN4high state, and those expressing PITX2 at higher average levels acquire a strongly altered HCN4low state. These observations indicate that PCs exhibit a PITX2 dosage-dependent threshold response. We propose a model to explain distinct PC phenotypes and functional consequences across a range of PITX2 dosages (Fig. 8a). Compared to heterozygous delB PCs, homozygous delB PCs express on average more PITX2, causing more PCs to pass threshold and form larger HCN4low subdomains of dysfunctional PCs within the SAN at the expense of functional PCs, and will therefore exhibit more severe SND. We hypothesize that also in a large fraction of human deletion carriers, elevated PITX2 dosage results in a greater proportion of PCs acquiring a dysfunctional HCN4low state and that this is sufficient to reach the threshold for SND, and, subsequently, AF.

a PITX2 dosage-dependent PC phenotype in the wild-type, delB/+, delB/delB SAN and how the proportion of affected PCs translates into predisposition for atrial arrhythmias and SND. b We propose that nucleotide variants modulate PITX2 expression levels in the SAN, atria and PV myocardium, driving SND and AF. c Overview of the human (Hg19) PITX2 locus, including the CTCF binding sites that maintain local chromatin conformation, the variant region near PITX2 associated with AF and SND, and the familial deletion recapitulated in the delB mouse. ATAC-seq tracks generated using human iPSC-derived PCs113 and LACMs114 and RNA-seq of human iPSC-derived PCs113 highlight differentially accessible DNA regions and thus, putative PC-specific regulatory elements. PC pacemaker cardiomyocyte, SND sinus node dysfunction, SAN sinus node, AF atrial fibrillation, SNP single nucleotide polymorphism, PV pulmonary vein, LA left atrium, RA right atrium, TAD topologically associated domain, CM cardiomyocyte.

PC specification and differentiation is under the control of a TF network that includes relatively broadly expressed TFs TBX5 and GATA6 and PC-specific TFs ISL1, SHOX2 and TBX376,77,78,79 (Fig. 2e). This network drives the expression of genes essential for PC function, including those that encode key ion channels like Hcn4, which is necessary for pacemaker function and heart contractions during embryogenesis58, while suppressing genes encoding TFs and functional proteins that may interfere with SAN function, including atrial CM-enriched Nkx2-5, Scn5a, Gja1 and Gja559,76. PC differentiation or function is impaired upon reduction or loss of any of the aforementioned PC TFs11,54,55,56,57,59,80. Our immunofluorescence analysis revealed that this essential PC TF network collapsed in HCN4low PCs, causing loss of PC identity and function. Gata6 expression is approximately 2-fold reduced in the delB/delB HCN4low subdomain (Fig. 3g). In mice, Gata6 haploinsufficiency predisposes to AA and SND65. Closer inspection of the histological data in this study suggests Gata6 haploinsufficient fetal SANs form subdomains of more or less affected PCs, somewhat reminiscent of the subdomains we observed in delB fetal SANs, indicating a GATA6 dosage-dependent threshold response in PCs. Because TF networks that control cell state are themselves stabilized by positive feedback and autoregulation, repression of ectopically expressed PITX2 in altered PCs is unlikely to be sufficient to re-establish the PC TF network.

Ectopic PITX2c expression in delB SAN PCs and in hiPSC-PCs induced transcriptional state changes that disrupted core PC electrophysiological properties, including their ability to spontaneously depolarize. PITX2+ PCs show less spontaneous activity, impairing AP initiation, while altered SAN morphology, and thus the SAN-RA interface, may hinder AP propagation from the SAN to the surrounding working myocardium, resulting in chronic, irregular atrial activation. Several genes upregulated in delB PCs are known to interfere with SAN function. The TFs SHOX2 and NKX2-5 regulate PC fate through a mutually antagonistic mechanism that defines the SAN-RA boundary during development53,59,81. In the delB/delB HCN4low domain, loss of SHOX2 expression coincides with NKX2-5 mis-expression (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1b), likely contributing to the activation of the atrial CM gene program. Both HCN4low PCs and AAV6-PITX2c PCs mis-express the cardiac sodium channel (SCN5A/Nav1.5) and high-conductance gap junction subunits Gja5/CX40 and Gja1/CX43 required for myocardial conductivity82. Vmax was increased in AAV6-PITX2c PCs, consistent with increased Nav1.5-driven sodium current. Activation of these atrial-enriched genes in a subset of PCs is likely to exacerbate SND, as their expression in PCs may disrupt AP synchronization or the generation of sufficient current to overcome current to load mismatch69,70,83,84,85.

PC function requires strictly regulated Ca2+ handling, and several genes involved in this process, including Pln, Atp2a2, Ryr2, Calm1, and Mfn271,86,87, were deregulated in delB SANs. Transitional PCs, a phenotypic intermediate between core PCs and atrial CMs, are essential to overcome the current to load mismatch and activate the atrial myocardium83,84,88. Transitional PC dysfunction causes SAN exit block, as is seen in transition zone-specific Shox2-deficient mice or heterozygous SCN5A loss-of-function allele carriers59,61,88. In addition to SND, we observed a possible exit block in delB/delB mice, suggesting that transitional PCs are also affected (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 8).

Compared to working CMs, PCs are characterized by underdeveloped contractile machinery, few mitochondria, and low metabolic demand relying on glycolysis rather than mitochondrial respiration71,89,90. In CMs, PITX2 maintains mitochondrial structure and function and Ca2+ homeostasis10,43,45,91,92,93,94,95. PITX2 deficiency in left atrial CMs or iPSC-derived atrial CMs causes mitochondrial dysfunction and induces a metabolic shift from mitochondrial respiration towards glycolysis, while gain-of-function activates genes encoding electron transport chain components and the expression of reactive oxygen species scavengers40,43,96. Conversely, oxidative stress in Pitx2-haploinsufficient mice promotes pro-arrhythmic remodeling and AF97. In delB PCs and AAV6-PITX2c PCs, we observed altered expression of metabolic and mitochondrial genes that align with those previously found in atrial CMs, suggesting that, also in PCs, PITX2 regulates these gene programs while they obtain a more atrial working CM-like state.

PITX2 has been found to modulate a Tbx5-dependent gene regulatory network that maintains atrial rhythm38. In this mechanism, TBX5 activates Pitx2, and PITX2 suppresses expression of TBX5-induced ion handling genes, including Scn5a, Gja1, and Ryr2. In contrast, in delB PCs and AAV6-PITX2c PCs, these genes are upregulated, indicating that the regulatory function of PITX2 is context-dependent. Indeed, in different CM cell states identified in adult left atrial and pulmonary vein myocardium, PITX2 was predicted to cooperate with different CM cell state-enriched TFs and co-factors to regulate CM cell state-enriched gene expression34. This is consistent with our findings that PITX2 expression in PCs causes unique transcriptome changes (Figs. 3f, 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4d, e).

The downstream effects of changes in TF dosage are often non-linear98 and exhibit tissue-specific threshold behavior. For example, while the lungs require high Pitx2c levels for normal morphogenesis, lower Pitx2c levels are sufficient to establish important aspects of left-atrial identity22,23. We found that already at low levels of PITX2 expression, delB PCs reduce ISL1 expression and change their state, indicating that PCs have a low tolerance for PITX2 expression with large consequences for gene regulation. Yet, in wild-type mice, sporadic PCs express PITX2, and we noted a PITX2+ domain adjacent to the SAN head expressing PITX2 as well, suggesting that some PITX2 is tolerated, or even required. Heterozygous loss of function of Pitx2 has been associated with affected SAN function10,38, an observation that has remained poorly understood in the context of the presumption that PITX2 is normally absent from the SAN and RA, but that may relate to expression of PITX2 in sporadic PCs and parts of the developing SAN we observed.

Previously, we have shown that the deletion of CTCF sites approximately 1 Mbp distant from PITX2 alters the topology of the entire locus (TAD fusion), causing altered interaction frequencies and durations between the PITX2 promoter and regulatory sequences, including those driving the lncRNA PLAYRR, a suppressor of Pitx2 in the developing gut and possibly in the SAN50,99,100 (Fig. 8c). Together, these data suggest the presence of a latently active regulatory network that drives PITX2 expression in PCs, which is actively repressed to prevent PITX2 expression in PCs. This stochastic activation-repression system may be unstable and “leak” and would be vulnerable to genetic variation that affects the function or interactions of regulatory DNA elements involved in this activation-repression system (Fig. 8c). We hypothesize that this vulnerability to deregulation and the low tolerance of PCs for PITX2 explain the variability in phenotype of heterozygous deletion carriers, as the presence of variants in deletion carriers will additionally modulate the level of ectopic PITX2 expression. The higher the average PITX2 expression level, the larger the proportion of HCN4low PCs over functional PCs, the more likely the threshold for SND is reached and the more severe the SND will be. Likewise, we hypothesize that AF/SND SNPs that decrease or elevate PITX2 expression in LA/pulmonary vein CMs, may also derepress PITX2 expression in PCs, predisposing to SND (Fig. 8b). SND and AF have been well established to frequently co-exist, and AF can contribute to SND51,52. Although PITX2 is not expressed in the delB RA, the adult delB/delB RA showed transcriptional changes consistent with a cardiac stress response. Prolonged, severe SND in delB/delB mice resulting in chronic, irregular atrial activation may promote a pro-arrhythmogenic state of RA tissue and increase susceptibility to AF (Fig. 8c).

We note a few limitations of our study design. The spatial transcriptomics analysis was limited to the transcripts provided by the probe atlas, which excludes non-coding RNAs like Playrr and splice variants, etc., and was of low resolution, requiring ROIs of >50 nuclei. The hiPSC PC model yielded <60% PC-like cells and involved PITX2 overexpression using AAV-mediated transduction, which was therefore not well-controlled in terms of level. However, the scRNA-seq data suggested that a large fraction of the PC cells expressed PITX2 at levels within a physiologically relevant range. The model could be refined using inducible expression methods, thereby controlling level and enabling assessment of reversibility of PITX2-induced state changes, or introduce the delB deletion in iPSC lines followed by PC differentiation.

In summary, we have shown that the ectopic expression of Pitx2 in SAN PCs severely disrupts the PC gene program in a PITX2 dosage-dependent manner, resulting in SND and atrial arrhythmogenesis, providing a mechanistic link between PITX2 and SND and AF.

Methods

Transgenic mice

DelB mice (FVB/NJ background (Janvier Labs))were previously generated in the Amsterdam UMC transgenic mouse core facility using CRISPR/Cas950. The region deleted in delB mice is as follows: mm10: chr3:128,329,001-128,346,349. Animals were housed under a light regime from 07:00 to 19:00 (60 lux) at 20–24 °C and relative humidity of 45-66%.

In vivo electrophysiology

Following anesthetization using 5% isoflurane (Pharmachemie B.V. 061756), both male and female adult mice ranging between 12 and 33 weeks of age were placed on a thermostated mat (37 °C). All mice received a steady flow of 1.5% isoflurane during all experiments. Electrodes connected to an electrocardiogram (ECG) amplifier (Powerlab 26T, AD Instruments) were inserted subcutaneously in the limbs and the ECG was measured for 5 min. The last 4 min of the 5-minute ECG were screened for any atypical cardiac events, and the last 60 s were used to determine ECG parameters (Lead I, L-R; RR-, PR- and QT-intervals, P-wave and QRS-durations). In adult mice, an octopolar CIB’er (NuMED) was inserted through the esophagus to capture and pace the atria. All pacing protocols were performed at 1.5x the atrial capture threshold, which was determined separately for each mouse. SNRT was evaluated using a 4 s pacing train (cycle length at 120 msec) and calculated as the interval between the last pacing stimulus and initiation of the first spontaneous P-wave. SNRT was normalized to resting heart rate (cSNRT=SNRT-RR interval) to account for inter-individual variations in sinus rate. The WBCL was evaluated using a 4 s pacing train starting at 100 msec, decreasing the pacing interval by 2 msec each train until the first atrioventricular block was detected. The susceptibility to AA was evaluated by 1 or 2 s pacing bursts starting with a cycle length of 60 msec, decreasing the pacing interval by 2 msec down to a cycle length of 10 msec. The duration of AA episodes is the sum of time each animal experienced an AA episode >1 s (2 passes). In a subset of adult mice, a combined beta-adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic blockade, blocking the autonomic nervous system (ANS block), was achieved by intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 mg/kg atropine and 1 mg/kg propranolol as previously described101. ECGs and pacing protocols described above were repeated 10 min after the ANS block was administered.

Embryo isolation

Following a timed pregnancy protocol, pregnant mice were anesthetized for 5 min using 4% isoflurane (Pharmachemie B.V. 061756) and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Embryos younger than embryonic day (E) 14.5 were isolated in cold PBS, and the yolk sac was collected for genotyping. Fetuses older than E14.5 were isolated in cold PBS, decapitated and the thorax was isolated for sufficient fixation. Tail samples were collected for genotyping by PCR. The embryos and fetuses were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraplast.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraplast-embedded fixed tissues were sectioned at 5 or 7 µm in series. Following removal of the embedding media, epitopes were unmasked by boiling for 5 min in a high-pressure cooking pan in Antigen Unmasking Solution (Vector H3300-250). Tissue sections were incubated with the primary antibody overnight in 4% BSA in PBS. The antibodies used are as follows: rabbit-anti-HCN4 (Merck Millipore AB5805), sheep-anti-PITX2 (Bio-Techne AF7388), rabbit-anti-ISL1 (GeneTex GTX102807), goat-anti-TBX3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology SC 31656), mouse-anti-SHOX2 (Abcam AB55740), goat-anti-CX40 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology SC 20466), goat-anti-NKX2-5(LabNed LN2027081), goat-anti-TNNI3 (Hytest 4T21/2), mouse-anti-TNNI3 (Merck Millipore MAB1691), chicken-anti-GFP (AvesLabs GFP1020), rabbit-anti-PCM-1 (Atlas Antibodies/Bio-connect (HPA023370)), Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat IgG (Invitrogen), Fluor 555 donkey anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen), Fluor 555 donkey anti-goat IgG (Invitrogen), Fluor 555 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen), Fluor 555 donkey anti-sheep IgG (Invitrogen), Fluor 647 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen), Fluor 647 donkey anti-sheep IgG (Invitrogen), DAPI (Sigma, D9542). Sections were mounted in PBS/Glycerol 1:1 and stored at 4 °C. Images were acquired using a Leica DM6000, TCA SP8 X confocal and Stellaris 5 confocal microscope.

In situ hybridization

Tissues were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraplast and sectioned at 7 µm. cDNA probes for Hcn4, Gja5, and Pitx2c were used and in situ hybridization was performed as previously described53,102. Images were acquired with a Leica DM5000 microscope. 3D volume reconstructions of the Hcn4+ expression domain in the RA at E17.5 wild-type (n = 8) and delB/delB (n= 5) fetuses were generated using Amira 3D 2021.2.

Image analysis

The relative expression level of PITX2 and ISL1 in individual nuclei was quantified by immunostaining equivalent sections containing wild-type (n = 2, 239 nuclei total), delB/+ (n = 3, 201 nuclei total) and delB/delB (n = 3, 280 nuclei total) for DNA (nuclei, DAPI), PITX2 and ISL1. Nuclei in the SAN head domain were segmented using ImageJ 1.54 f using StarDist 2D 0.3.0, and the mean gray value was determined per nucleus per channel to quantify the relative expression of PITX2 and ISL1103,104,105. The number of PITX2+ nuclei were quantified by immunostaining equivalent sections containing the wild-type (n = 5), delB/+ (n = 6), and delB/delB (n = 6) fetal SAN head domain for DNA (nuclei, DAPI), HCN4 and PITX2 expression. Images were then acquired using the Stellaris 5 confocal microscope. Nuclei in the SAN head domain were again segmented using ImageJ 1.54 f using StarDist 2D 0.3.0 and assigned to either HCN4high or HCN4low subdomains based on HCN4 expression. The mean gray value per nucleus was then determined per nucleus per region per channel.

Spatial transcriptomics

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded wild-type, delB/+, and delB/delB E17.5 fetuses and adult mice were sectioned at 5 µm in series and screened by immunohistochemistry using a rabbit-anti-HCN4 (Merck Millipore AB5805) and goat-anti-TNNI3 (Hytest 4T21/2) antibody to identify the SAN head domain. The samples were prepared for the Nanostring GeoMx Digital Spatial Profiler according to the GeoMx Manual Slide Preparation User Manual (MAN-10150-3) using anti-HCN4, anti-cTNNI3 and Sytox Green Nucleic Acid Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific S7020) and the GeoMx Whole Transcriptome Atlas Mouse RNA Probes for NGS (Bruker Spatial Biology). ROIs were segmented using HCN4 signal intensity thresholds that clearly demarcated the E17.5 HCN4+ SAN domain from the RA and the E17.5 HCN4high delB subdomain from the HCN4low delB SAN subdomains. ROIs were segmented based on TNNI3 signal intensity in the adult heart. The size and the number of nuclei per ROI are listed in Supplementary Data 14.

Spatial transcriptomics data analysis

FASTQ files were trimmed, stitched, aligned and deduplicated using the Nanostring GeoMx NGS pipline (version 2.3.3.10). The generated DCC files were processed with the R GeoMxTools package (version 3.8.0) using the configuration file, the sample sheet and the probe metadata file (v1). The percentage of reads trimmed, stitched, aligned and deduplicated was calculated for each segment, all of which passed the thresholds of 80, 80, 75 and 50 percent. Approximately 6000 genes were detected in the smallest segment, which contained 17 nuclei. No segments were excluded after the segment quality control. Low-performing probes were removed based on the limit of quantification, defined as two standard deviations above the geometric mean of the negative control probe counts (210 negative control probes are included in the NanoString GeoMx Mouse Whole Transcriptome Atlas). Normalization was performed using quantile-normalization. Differential gene expression analysis was performed using limma (version 3.60.1). Multiple testing correction was performed using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Differentially expressed genes were defined as an adjusted p < 0.05 and a log2fold-change (L2FC) > 0.25.

Adeno-associated virus type 6 (AAV6) preparation

AAV6 were produced in HEK293T cells. Briefly, low passage HEK293T cells were seeded in 145 mm dishes at a density of 1.5 × 107 cells per dish in DMEM-GlutaMax (ThermoFisher Scientific 31966-047) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma F7524) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P/S) (ThermoFisher Scientific 15140-122). Cells were transfected with 15 µg of the AAV transfer plasmid (pAAV-cTnT-PITX2c-p2a-H2B-EGFP or pAAV-cTnT-mCherry-p2a-H2B-EGFP) and 33 µg AAV6 helper plasmids (pDP6) using linear polyethylenimine(PEI)-Max (Polysciences Inc 24765-1) at a ratio of PEI:DNA ratio of 2:1. After 24 h, medium was refreshed with Opti-MEM medium (ThermoFisher Scientific 11058-021) and the cells were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C. AAV6 in the medium was obtained by collecting and filtering the medium through a 0.22 μm pore sized PVDF syringe filter, and then concentrated using Amicon™ Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Units (Millipore/Merck, #UFC910024), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic titre was determined by qPCR.

Adeno-associated virus type 9-Myo4A (AAV9-Myo4A) preparation

AAV9 vectors were produced by transfecting low passage HEK293T (ATCC CRL-3216) cells, which were seeded a day prior at a density of 1.5 × 107 cells per dish in DMEM-GlutaMax supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. The cells were transfected with 13 µg Rep2Cap9-Myo4A plasmid106, 21 µg AdenoHelper plasmid and 13 µ AAV transfer plasmid (AAV9Myo4A-hTNNT2p-i-ACCuORF-hPITX2c-IRES-H2B-GFP-WPRE or ssAAV9Myo4A-hTNNT2p-mCherry-P2A-H2B-GFP-WPRE) using PEI-Max at a PEI:DNA ratio of 2:1, during which the medium was replaced with Opti-MEM medium. The cells were collected 72 h after transfection, and the medium was concentrated by tangential flow filtration using the ÄKTA flux s system (GE Healthcare) to a final volume of 20 mL. Cells and medium were then combined, lysed by two freeze-thaw cycles, and followed by Benzonase (Merck 1016950001) treatment. AAV9 vectors were purified by iodixanol density-gradient ultracentrifugation, after which the AAV-containing fraction was collected and buffer buffer-exchanged and concentrated to PBS containing 0.001% Pluronic F68 (ThermoFisher Scientific 24040032) using Amicon Ultra-15 100 kDa centrifugal filter units (Millipore/Merck, #UFC910024). Concentrated AAV vectors were aliquoted and stored at –80 °C until use. Genomic titre was determined by qPCR.

Flow cytometry to evaluate transduction efficiency

Cultures of hiPSC-derived PCs were transduced with AAV6 particles on day 18. Virus-containing medium was removed the next day, and 7 days post-transduction, the cells were prepared for flow cytometry. Cells were dissociated using 1x TrypLE Select (Thermo Fisher Scientific #12563011) and resuspended in a buffer containing 0.5 M EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific #15575020) and 10% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, #A8022). Acquisition was performed on FACSSymphony A1 Cell Analyzer (Beckton Dickinson). Data were analyzed using FlowJo version 10.

Single-cell RNA sequencing

Previously described hiPSC-derived PCs73 (female, LUMC0099iCTRL04; registered in the Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Registry (https://hpscreg.eu/cell-line/LUMCi004-A)) were thawed and seeded in matrigel-coated wells at a density of 106 cells per well, and were transduced with AAV6 (TNNT2 promoter-driven PITX2c-p2a-H2B-EGFP or mCherry-p2a-H2B-EGFP). Virus was removed from the cells the next day. 7 days post-transduction, they were dissociated using 1x TrypLE Select (Thermo Fisher Scientific #12563011). Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) was performed on the 10x Genomics platform using the Chromium Single Cell 5′ v2 Reagent Kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression libraries were sequenced on the NovaSeqXPlus system (Illumina) with 150 bp paired-end reads. ScRNA-seq reads were mapped to the human genome (hg19 plus a custom added overexpression cassette) using STARsolo (version 2.7.11a) (https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR). The alignment was performed with default parameters unless otherwise specified. The non-default parameters used were: Configure Chemistry Options- Cv3; Matching the Cell Barcodes to the WhiteList- Multimatching to WL is allowed for CBs with N-bases (CellRanger 3, 1MM_multi_Nbase_pseudocounts); Maximum to minimum ratio for UMI count- 10 for mCherry samples and 12.5 for PITX2c samples (based on Barcode Rank plots). The resulting BAM files were processed to extract raw counts for subsequent downstream analysis with Seurat107. Briefly, high-quality single cells were selected according to the following parameters: gene count >350, mRNA molecule count >500 and, as cardiomyocytes naturally exhibit increased mitochondrial gene expression, a more permissive threshold of <20% for mitochondrial gene count was used108. Next, the SCTransform command was used for normalization, scaling and identification of variable features (nfeatures = 3000). Raw counts were first normalized using Normalize Data, and the data were split by sample. Each sample was then independently normalized with SCTransform. To ensure consistent gene representation, the dataset was restricted to the common gene set shared by all samples. 3000 highly variable features were then selected using SelectIntegrationFeatures, followed by PrepSCTIntegration and FindIntegrationAnchors to identify shared biological states across samples. These anchors were used to perform integration via IntegrateData, yielding a batch-corrected expression matrix. Dimensionality reduction was performed using PCA and UMAP with the top 10 principal components. The top 10 principal components were used to compute a nearest-neighbor graph (FindNeighbors). Clustering was then performed at multiple reductions (FindClusters with resolution = 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.4), and the resolution 0.4 clustering was used for downstream analyses. FeaturePlot, VlnPlot and DoHeatMap commands were used to visualize gene expression.

For each given cluster in the UMAP, the number of cells from the AAV9-mCherry and AAV9-PITX2 samples and determined the relative contribution of each sample to a cluster, the ratio between the cell numbers normalized to the total cell number of each sample was calculated (Supplementary Fig. 6c). A Z-test109 was used to determine whether the difference in cell contributions per sample were significant (Supplementary Fig. 6c).

Cellular electrophysiology

Coverslips with hiPSC-PCs were put in a recording chamber on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon Diaphot, Melville, New York, NY, USA) and the cells were superfused with modified Tyrode’s solution (36 ± 0.2 °C) containing (mM): NaCl 140, KCl.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1.0, glucose 5.5, HEPES 5.0; pH 7.4 (adjusted with NaOH). A custom-made slider for two filter blocks was used to detect EGFP- and mCherry-positive cells. Action potentials (APs) were measured from single CTRL and PITX2 hiPSC-PCs using the amphotericin-perforated patch clamp methodology and an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data acquisition and data analysis were performed with custom software. Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (TW100F-3, World Precision Instruments Germany Gmb) using a custom vertical microelectrode puller and had tip resistances of 2.0–3.0 MΩ after filling with the pipette solution containing (in mM): K–gluconate 125, KCl 20, NaCl 10.0, amphotericin-B 0.44, HEPES 10, and pH 7.2 (KOH). All potentials were corrected for the estimated liquid junction potential110. Signals were low-pass filtered (cut-off frequency: 5 kHz) and digitized at 5 (spontaneous APs) and 40 (paced APs) kHz. The cell membrane capacitance was determined by dividing the decay time constant of the capacitive transient in response to hyperpolarizing voltage-clamp steps of 5 mV (from a holding potential of −40 mV) by the series resistance.

APs were measured without pacing as well as at 1 Hz pacing frequency with 3-ms, 1.2× threshold current pulses through the patch pipette. The latter was performed under the condition of an in silico injected 2 pA/pF Kir2.1 current using dynamic clamp111 to anticipate the potential presence of quiescent cells, and potential differences in MDP and cycle length, which all will indirectly affect the availability of ion channels underlying cardiac AP112. In the presence of Kir2.1 injected currents, hiPSC-PCs all become quiescent, the MDP of hiPSC-PCs is between -80 and -85 mV, and APs can be evoked at a fixed 1 Hz pacing frequency. We analyzed the cycle length, MDP, maximum AP upstroke velocity (Vmax), AP amplitude (APA), and APD at 20%, 50%, and 90% repolarization (APD20, APD50, and APD90, respectively). Parameters from 10 consecutive APs were averaged.

GO enrichment analysis

GO enrichment analysis was carried out using the Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER) Classification System 19.0.

Statistical and reproducibility

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 10 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA. The method used to test statistical significance and the number of biological replicates (n) are stated in the figure legends. Data are presented as means unless otherwise stated. No data were excluded, and the Investigators were blinded during experiments and analyses.

Ethics statement

The guidelines from the Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and Dutch government were followed for all animal care, housing, husbandry and experiments. All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Experimental Committee of the Amsterdam University Medical Centers and animal group sizes were based on previous experience.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The scRNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the GEO database under the accession code GSE293813. Nanostring GeoMx-DSP datasets are available under accession codes GSE291746 (E17.5 wild-type and delB/delB SAN and RA), GSE291749 (E17.5 wild-type, delB/+, delB/delB SAN, RA, and LA), and GSE291752 (adult wild-type, delB/+, and delB/delB SAN and RA). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Spitz, F. & Furlong, E. E. Transcription factors: from enhancer binding to developmental control. Nat. Rev. Genet 13, 613–626 (2012).

Kim, S. & Wysocka, J. Deciphering the multi-scale, quantitative cis-regulatory code. Mol. Cell 83, 373–392 (2023).

Huang, N., Lee, I., Marcotte, E. M. & Hurles, M. E. Characterising and predicting haploinsufficiency in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001154 (2010).

Maurano, M. T. et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science 337, 1190–1195 (2012).

Consortium, G. T. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 369, 1318–1330 (2020).

Li, X., Lappalainen, T. & Bussemaker, H. J. Identifying genetic regulatory variants that affect transcription factor activity. Cell Genom. 3, 100382 (2023).

Soldner, F. et al. Parkinson-associated risk variant in distal enhancer of alpha-synuclein modulates target gene expression. Nature 533, 95–99 (2016).

Glassberg, E. C., Gao, Z., Harpak, A., Lan, X. & Pritchard, J. K. Evidence for weak selective constraint on human gene expression. Genetics 211, 757–772 (2019).

Zug, R. Developmental disorders caused by haploinsufficiency of transcriptional regulators: a perspective based on cell fate determination. Biol. Open 11, https://doi.org/10.1242/bio.058896 (2022).

Tao, Y. et al. Pitx2, an atrial fibrillation predisposition gene, directly regulates ion transport and intercalated disc genes. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 7, 23–32 (2014).

Frank, D. U. et al. Lethal arrhythmias in Tbx3-deficient mice reveal extreme dosage sensitivity of cardiac conduction system function and homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E154–E163 (2012).

Bruneau, B. G. et al. A murine model of Holt-Oram syndrome defines roles of the T-box transcription factor Tbx5 in cardiogenesis and disease. Cell 106, 709–721 (2001).

Kathiriya, I. S. et al. Modeling human TBX5 haploinsufficiency predicts regulatory networks for congenital heart disease. Dev. Cell 56, 292–309.e299 (2021).

Sweat, M. E. et al. Tbx5 maintains atrial identity in post-natal cardiomyocytes by regulating an atrial-specific enhancer network. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2, 881–898 (2023).