Abstract

Magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs) are crucial components in high-performance spintronic devices. Traditional MTJs rely on ferromagnetic (FM) materials, but significant improvements in speed and packing density could be enabled by exploiting antiferromagnetic (AFM) compounds instead. Here, we report all-collinear AFM tunnel junctions (AFMTJs) fabricated with van der Waals A-type AFM metal (Fe0.6Co0.4)5GeTe2 (FCGT) electrodes and nonmagnetic semiconducting WSe2 tunnel barriers. The AFMTJ heterostructure device achieves a tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) ratio of up to 75% in response to magnetic field switching. Our results demonstrate that the TMR exclusively emerges in the AFM state of FCGT, rather than during the AFM-to-FM transition. By engineering FCGT electrodes with either even- or odd-layer configurations, volatile or non-volatile TMR could be selected, consistent with an entirely interfacial effect. TMR in the even-layer devices arose from Néel vector switching. In the odd-layer devices, TMR stemmed from interfacial spin-flipping. Experimental and theoretical analyses reveal a new TMR mechanism associated with interface-driven spin-polarized transport, despite the spin-independent nature of bulk FCGT. Our work demonstrates that collinear AFMTJs can provide comparable performance to conventional MTJs and introduces a new paradigm for AFM spintronics, in which the spin-dependent properties of AFM interfaces are harnessed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

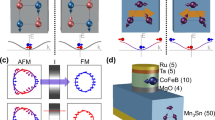

Magnetoresistive random access memory (MRAM) has emerged as a promising candidate for next-generation information storage devices due to its unique combination of non-volatility, robust endurance, and potential for scalability1,2,3. The building block for MRAM is a magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ), typically composed of two ferromagnetic (FM) electrodes separated by a nonmagnetic (NM) barrier and utilizing tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) to distinguish the relative magnetization orientations of the electrodes4,5,6,7,8. However, these MTJs suffer from large stray fields and are further inhibited by the relatively slow dynamic responses inherent to ferromagnets. These factors hinder high-density and high-speed applications. Antiferromagnetic (AFM) materials, with vanishing stray fields and ultrafast dynamics, have the potential to overcome these limitations9,10,11. However, the absence of a net magnetization implies a spin-independent nature of antiferromagnets, and hence an AFM tunnel junction (AFMTJ) has long been considered elusive12. Until very recently, AFMTJs have been constructed using two approaches, both of which rely on noncollinear AFM configurations. Electrodes that exhibit noncollinear AFM configurations and host the momentum-dependent transport polarization supportive to TMR are experimentally constructed in the first approach13,14 (Fig. 1a). The second one uses a two-dimensional (2D) Van der Waals (vdW) AFM semiconductor as the barrier for a spin-filter AFMTJ15, where a twisted stacking is introduced to generate a noncollinear alignment of the Néel vectors of the adjacent layer, allowing a magnetic field induced nonvolatile phase transition for a spin-filtering TMR (Fig. 1b). While these advances are significant and promising, an important gap remains in the field of AFMTJs: the realization of AFMTJs based on collinear AFM metals.

a An AFMTJ based on non-collinear AFM (NC-AFM) electrodes and a non-magentic (NM) barrier. b A spin-filter AFMTJ based on NM electrodes and an AFM barrier, where a non-collinear alignment of the Néel vectors is induced by twisting the collinear AFM (C-AFM) layers in the barrier. c An all-collinear AFMTJ with C-AFM electrodes and an NM barrier. The interfaces are highlighted in red color.

Collinear antiferromagnets, with two antiparallel-polarized sublattices, were discovered prior to their noncollinear counterparts16. However, a strong magnetoresistive effect in response to the rotation of the Néel vector in collinear AFM devices has yet to be observed (Fig. 1c). This stems from two major challenges: the lack of a collinear AFM system supportive of convenient Néel vector manipulation, and the inability to generate spin-polarized transport in conventional antiferromagnets. A collinear AFMTJ with a large TMR would not only complete the spectrum of available AFMTJs but also assist in a deeper understanding of the fundamental physics underlying antiferromagnets. From a technological point of view, collinear AFMTJs, especially those utilizing a perpendicular magnetic anisotropy, possess significant advantages in scalability compared to noncollinear AFMTJs. This is due to the absence of magnetic canting at the edges of collinear AFMs.

Results and discussion

Here, we present a purely collinear AFMTJ constructed as a Van der Waals (vdW) heterostructure (Fig. 1c). The recently discovered high-temperature vdW AFM metal (Fe0.6Co0.4)5GeTe2 (FCGT) was selected for the device electrodes17,18,19,20,21. FCGT has a so-called A-type collinear AFM stacking, where the magnetic moments within each vdW layer exhibit FM alignment with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy, while the interlayer show AFM coupling, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. Since the A-type AFM materials with odd and even numbers of layers exhibit different properties in the 2D limit, we systematically investigated the transport properties of FCGT with varying numbers of layers (see Supplementary Material Fig. S1). As shown in Fig. 2c, a standard Hall device of even-layered FCGT (6L) exhibits near flat Rxy between −1.8 T to +1.8 T, indicating its AFM magnetic ground state in this range. With an increase in the perpendicular magnetic field, the FCGT undergoes AFM-to-FM transitions around ±1.8 T and adopts a fully FM state at ±3.0 T, with a behavior generally found in vdW A-type AFM materials under an applied magnetic field. Hence, as shown in Fig. 2c, the FCGT states and the corresponding magnetic fields can be divided into three states; an AFM state (the blue region, up to 1.8 T), an AFM-to-FM transition state (the grey region, between 1.8 T and ~3.0 T), and a FM state (the yellow region, beyond ~3.0 T). In contrast to the relatively flat Rxy in the AFM state of even-layered FCGT, a noticeable zero-field anomalous Hall effect is observed from the Hall device fabricated with odd-layered FCGT (see Supplementary Material Fig. S1).

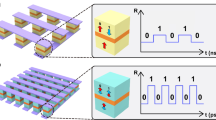

a Schematic of A-type AFM stacking of FCGT. b Schematic of a FCGT/WSe2/FCGT AFMTJ. c, Symmetrical Hall resistance Rxy as a function of perpendicular magnetic field in 6 L FCGT at 10 K. The AFM state is colored by blue. The AFM to FM transition is colored by grey. The FM state is colored by yellow. d Tunneling resistance Rzz and corresponding TMR ratio for FCGT/WSe2/FCGT AFMTJ device D1 at a fixed current 20 nA at 10 K. The sweep directions of the magnetic field are indicated by green and orange arrows. An optical image of device D1 is shown in the top-left inset, where the FCGT is outlined by the blue dashed line and the WSe2 is outlined by the orange dashed line. The black scale bar is 10 µm. The thicknesses of the FCGT layers in device D1 are denoted in the bottom-right inset.

The typical structure of the AFMTJ device is illustrated in Fig. 2b, where two FCGT electrodes are separated by a semiconductor WSe2 tunneling layer. To systematically investigate the AFMTJ, three types of devices were fabricated. These types differed in the number of layers in the incorporated FCGT. Specifically, the investigation was performed with even-even type (with both FCGT electrodes consisting of even-numbered layers), odd-even type (with odd-numbered FCGT layer on one side and even-numbered FCGT layer in the other side), and odd-odd type (with both FCGT electrodes consisting of odd-numbered layers) devices. Firstly, we focus on measurements obtained from the even-even configuration, named device D1, which exhibited the intrinsic characteristics of AFMTJs due to the absence of the net magnetization in even-layered FCGT. Atomic force microscopy (Supplementary Material Fig. S2) revealed that the top FCGT layer, middle WSe₂ layer, and bottom FCGT layer in device D1 had thicknesses of 6.0 nm, 2.8 nm, and 5.9 nm, corresponding to 6 L, 4 L, and 6 L structures, respectively. Given the critical role of the interfaces in MTJs, the pick-up method was used to fabricate the devices (see methods). In contrast to the metallic behavior observed from the FCGT standard hall device, the resistance-temperature curve of the AFMTJ devices shows insulating behavior (Supplementary Material Fig. S3), confirming that the WSe2 layer was pinhole-free and functioned effectively as a tunneling barrier. We next focus on the characteristics of the AFMTJs.

Upon sweeping an out-of-plane magnetic field B within the range ±4 T at 10 K, a prominent TMR signal was observed in the AFMTJ with even-even configuration. As shown in Fig. 2d, two prominent peaks emerged at ±0.9 T, which were within the AFM state and much lower than the AFM-to-FM transition field of FCGT. The highest resistance, RH, of 61.2 kΩ was measured at +0.9 T and the lowest resistance, RL, of 35.0 kΩ was measured at +1.5 T. Hence, the TMR ratio (RH – RL)/ RL reached 75 % at 10 K, comparable to that of FM-based vdW MTJs22,23,24,25,26,27. Such a large TMR ratio is unexpected in an AFMTJ due to the spin-degeneracy of an AFM. To eliminate the possibility that the observed TMR phenomenon arose from an AFM-to-FM phase transition, the emergence fields of the TMR and the AFM-to-FM transition fields of FCGT were collected from various devices and systematically compared (Supplementary Materials Fig. S5). The results show a significant gap between the two field regions, providing clear evidence that the TMR effect manifests in the AFM state. In addition to the prominent TMR behavior, a much smaller magnetoresistance transition occurred under a higher magnetic field of up to ±3.0 T (Supplementary Material Fig. S3b). This behavior is consistent with a change in the longitudinal magnetoresistance, Rxx, associated with the AFM-to-FM phase transition of FCGT. We note that this AFM-FM transition field is the same as that observed in the intrinsic FCGT hall device and consistent with those previously reported in FCGT17. This indicates that the AFM-to-FM transition behavior of FCGT is preserved in the FCGT/WSe₂/FCGT structure, supporting the assertion that the observed TMR behavior at +0.9 T originates from the AFM state of FCGT. The emergence of the prominent TMR signal within the AFM state and the negligible magnetoresistance change observed at the AFM-FM transition demonstrate that this TMR effect is an interface effect rather than a bulk effect. During the AFM-FM transition, although the net magnetic moment undergoes significant changes, the interfacial magnetic moment remains stable, leading to only minor fluctuations in magnetoresistance.

To systematically evaluate the performance of vdW AFMTJs, we performed temperature-dependent measurements on device D1. As shown in Fig. 3a, both the TMR ratio and the TMR transition field decrease with increasing temperature. To quantitatively display this phenomenon, we define TMR_max as the maximum TMR ratio and TMR_ZF as the TMR ratio at zero field. As shown in Fig. 3b, a typical volatile TMR behavior is observed, which decreases monotonically with increasing temperature and vanishes above 230 K. To further evaluate the interlayer interaction, we define BC1 and BC2 as the critical transition fields where the TMR effect respectively emerges and then vanishes under increasing magnetic field. As illustrated in Fig. 3c, at 10 K, the transition fields BC1 and BC2 exhibit values of 0.84 T and 0.98 T, respectively. Both fields show a gradual decrease with increasing temperature and ultimately vanish at high temperatures. Another even-even device, designated as D5 with 14 L FCGT/5 L WSe2/8 L FCGT, demonstrates analogous characteristics (see Supplementary Materials Fig. S4). We speculate that the interfacial moments serve to switch the Néel vector in FCGT. It should be noted that the interfacial magnetic moments only experience an interlayer magnetic coupling of half intensity compared with the magnetic moment of the inside layers. As illustrated in Fig. 3d, when the magnetic field is increased to BC1, the interfacial moments of one FCGT electrode are flipped first due to the relatively weak interlayer magnetic coupling, causing the Néel vector to switch due to interlayer AFM coupling. When the magnetic field is further increased to BC2, this process occurs in the opposite FCGT electrode. Therefore, BC1 and BC2 can be considered as the “coercivities” of the interfacial moments. The Interface-assisted Néel vector switching is governed by the competition between magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy, AFM exchange energy, Zeeman energy, and domain wall dynamics. Although the two FCGT electrodes in device D1 have identical nominal thicknesses, differences in their local environments—arising from proximity coupling to distinct substrate or capping layers—and variations in defect distributions can lead to different effective anisotropies and domain pinning strengths, resulting in distinct critical switching fields. This asymmetry enables the observation of TMR. We note that such interface-assisted Néel vector switching has also been reported in other A-type antiferromagnets such as Cr2O328. In this scenario, the TMR characteristics of the AFMTJs with even- and odd-layered FCGT electrodes should then differ, since their switching behaviors are different.

a Temperature-dependent TMR behavior of even-even device D1 at fixed current of 20 nA. The range of sweep field is ±4 T. The ascending and descending magnetic field sweeps are colored by orange and green, respectively. BC1 and BC2 are defined by the magnetic field at half peak height where the TMR effect respectively emerges and vanishes during field ascending. b Temperature-dependent maximum TMR ratio (TMR_max) and TMR ratio at zero field (TMR_ZF). c Temperature-dependent BC1 and BC2. d Left: TMR ratio as a function of magnetic field for device D1 at 10 K. Right: Schematic of spin configuration switching with applied magnetic field. A 4-layer spin configuration is used to represent even-numbered layers. The full-loop (±4 T) scan is denoted by solid orange-green arrows. The half-loop (±1.5 T) scan is represented by dashed orange-green arrows.

To explore this assertion, an odd-even type FCGT/WSe2/FCGT device, named D2, was fabricated. Optical and atomic force microscopy (Supplementary Material Fig. S2) showed that the underlying FCGT layer number was 14 L and the upper FCGT layer number was 5 L. Hence, a zero-net magnetic moment existed in one side and a residual net magnetic moment existed on the other side. As shown in Fig. 4a and b, typical volatile TMR behavior was observed in this odd-even configuration below 80 K. Interestingly, as the temperature increased, non-volatile TMR behavior appeared above 80 K with TMR_max coincident with TMR_ZF in Fig. 4b, despite the absence of a pinning layer. The critical transition fields BC1 and BC2 were extracted to deduce the mechanism. Figure 4c shows BC2 gradually approaching zero with increasing temperature, as observed in the even-even AFMTJ devices and indicating that BC2 is related to the interfacial coercivity of the even-layered FCGT electrode in this device. On the other hand, BC1 is associated with the interfacial coercivity of the odd-layered FCGT. As the temperature increases, BC1 first decreases and then clearly increases toward the opposite direction, with a sign change at 80 K. This behavior, unprecedented in conventional MTJs, is responsible for the non-volatile TMR at high temperatures.

a Temperature-dependent TMR behavior of the odd-even device D2 at a fixed current of 1 nA. The range of the sweep field is ±4 T. The ascending and descending magnetic field sweeps are colored by orange and green, respectively. b Temperature-dependent TMR_max and TMR_ZF. c Temperature-dependent BC1 and BC2. d Left: TMR ratio as a function of magnetic field for device D2 at 10 K. Right: Schematic of spin configuration switching with applied magnetic field. Use a 5-layer spin configuration to represent odd-numbered layers and a 4-layer spin configuration to represent even-numbered layers. The full-loop (±4 T) scan is denoted by solid orange-green arrows. The half-loop (±1.5 T) scan is represented by dashed orange-green arrows.

The temperature-dependent non-volatile TMR behavior and BC1 sign change behavior suggest two competing interactions29,30,31,32,33. Previous report suggests that during ascending or descending magnetic fields from FM states, (Fe0.56Co0.44)5GeTe2 exhibits an intermediate state M1. As shown in Fig. 4d and Fig. S7, the magnetic moments of all adjacent layers are antiparallel in the AFM alignment, while the magnetic moments of the interface and its adjacent layers are aligned parallel in the M1 state18. In the process of descending field from positive to negative, as shown in Fig. S7b, the magnetic moments in all layers point to a positive direction (the FM state) at a large positive field. With decreasing field, FCGT first enters into the M1 state, where the energy of the M1 state is lower than that of the AFM state due to the lower Zeeman energy. Further decreasing the field, the energy of the AFM state will become lower than that of the M1 state. However, there is an energy barrier between the M1 state and the AFM state; either further decreasing the magnetic field or increasing thermal agitation energy is required to overcome the barrier and then drive FCGT from the M1 state to the AFM state. As shown in Fig. S7b, the descending field needs to get to naegative value to drive the M1 state to the AFM state at low temperature. At higher temperatures, the AFM state can be realized at a positive field due to the larger thermal agitation energy. Hence, the interfacial coercivity BC1 exhibits a negative value when T < 80 K. At higher temperatures, the thermal energy is large, leading to a positive BC1. The scenario shown here can also be viewed as an exchange bias between an uncompensated interfacial FM monolayer and compensated AFM slabs, which can be further verified in the isolated odd-layered FCGT hall device (see Fig. S9b). The complete spin switching diagram for the odd-even type device is depicted in Fig. 4d, where the Neél vector switching occurs exclusively in the even layer, while the spin of the odd layer switches between the M1 alignment and AFM alignment.

To verify this physical picture, +1.5 T field-cooling and ±1.5 T field sweeps were performed on both the odd-even and even-even devices (Fig. S8). Although 1.5 T exceeds the coercivity of the interface layer, it remains below the field required for the FCGT transition from AFM to FM states, thereby precluding the formation of the M1 magnetic alignment during negative field sweeps. As shown in the supplementary material Figs. S8 and S9, the TMR peaks in the even-even device are symmetric during the ascending and descending magnetic field sweeps, consistent with the results from ±4 T large-field scans. In contrast, the height and width of the TMR peaks from the odd-even device were asymmetric between the ascending and descending sweeps, attributed to the presence of the M1 alignment and an exchange bias33 interaction in the odd-layered FCGT that results in self-pinning at high temperature. These results are in line with the half-loop transition in the schematic diagram in Figs. 3d and 4d, verifying the switching of the Néel vector in the even layer and the switching of the M1/AFM alignment in the odd layer. The inherent properties of 2D vdW materials thus enable the realization of nonvolatile TMR signals in this system with no requirement for an extra pinning layer. We also fabricated odd-odd type devices (Fig. S10) and since the M1/AFM transition occurs in both sides, only volatile TMR was observed.

The observation of conventional TMR behavior in even-even FCGT/WSe2/FCGT and non-volatile TMR behavior in odd-even FCGT/WSe2/FCGT is tantalizing, as it hints at a new underlying mechanism for TMR. Previous studies of TMR in AFMTJs have focused on the mechanisms associated with momentum-dependent34,35 or sublattice-dependent36,37 transport spin polarizations12. However, these two mechanisms can be excluded from our investigation of the behavior in the A-type collinear AFM FCGT, firstly because the FCGT slab maintains a preserved PT symmetry—a combination of inversion symmetry (P) and time reversal symmetry (T)—leading to a spin-degenerate electronic structure. Secondly, the A-type stacking within the vdW structure suggests a negligible intra-sublattice coupling along the out-of-plane direction. Our experiments demonstrate that the interface plays a crucial role in supporting TMR and point to a distinct mechanism associated with the uncompensated interfaces38.

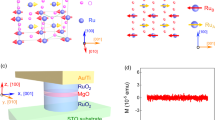

To further elucidate this mechanism, first-principles quantum transport calculations were performed on vdW AFMTJs with A-type AFM electrodes. For illustrative purposes and without compromising generality, we adopted an AFMTJ structure comprising a central vacuum layer serving as the tunnel barrier, with artificial A-type AFM Fe5GeTe2 (A-F5GT) electrodes. This device structure, as depicted in Fig. 5a and S11, allowed us to explore the physics underlying the TMR mechanism. The A-F5GT is designed to host fully occupied atomic sites and ordered Fe-vacancies based on Fe5GeTe2 (Figs. 5a and S11), keeping PT symmetry and A-type AFM properties similar to those of FCGT (Fig. 2a). This circumvents the computational challenge of simulating disordered split sites and doping atoms in FCGT. The PT symmetry in A-F5GT enforces a spin-degenerate electronic structure (Fig. 5b). As a result, the number of conduction channels for the out-of-plane direction is identical for up-spin (\(\sigma=\uparrow\)) and down-spin (\(\sigma=\downarrow\)) electrons at any transverse wave vector \({k}_{\parallel }=({k}_{x},{k}_{y})\) (Supplementary Material Fig. S11), implying the absence of bulk-driven spin-polarized transport in this A-type antiferromagnet.

a Atomic structures of a A-F5GT/vacuum/A-F5GT AFMTJ where the left and right A-F5GT electrodes are considered to be of semi-infinite thickness in the ballistic transport model. The arrows indicate the magnetic moments alignments for P and AP states. The dashed box denotes the unit cell of the A-F5GT electrode with an A-type AFM stacking. b Band structure of bulk A-F5GT. c Calculated \({k}_{\parallel }\)-dependent transmissions \({T}_{P}^{\sigma }({\vec{k}}_{\parallel })\) and \({T}_{{AP}}^{\sigma }({\vec{k}}_{\parallel })\) at EF in the 2D Brillouin zone for P and AP states, where \(\sigma\) denotes the spin channels.

We define the P and AP states in such an AFMTJ according to the relative orientations of the uncompensated interfacial moments, and calculate the associated \({k}_{\parallel }\)-dependent transmissions \({T}_{P}^{\sigma }({\vec{k}}_{\parallel })\) and \({T}_{{AP}}^{\sigma }({\vec{k}}_{\parallel })\) (Fig. 5c). We find \({T}_{P}^{\uparrow }({\vec{k}}_{\parallel })\) and \({T}_{P}^{\downarrow }({\vec{k}}_{\parallel })\) differ significantly, implying a finite transport spin polarization in the P states (Fig. 5c). On the other hand, we find \({T}_{{AP}}^{\uparrow }({\vec{k}}_{\parallel })\) and \({T}_{{AP}}^{\downarrow }({\vec{k}}_{\parallel })\) are significantly suppressed and become similar. This behavior resembles that of conventional MTJs with identical FM electrodes, and cannot be attributed to the bulk properties of the AFM electrodes. Rather, it stems from interface-driven spin-polarized tunneling. As a result, the total transmission for the P state (\({T}_{P}\)) is much larger than that for the AP state (\({T}_{{AP}}\)), leading to a TMR ratio \({TMR}=\frac{{T}_{P}-{T}_{{AP}}}{{T}_{{AP}}}\) as high as ~1000%. We find that replacing the vacuum layer with a realistic 2D insulator does not qualitatively influence the tunneling behavior of such an AFMTJ (Supplementary Material Fig. S12). The TMR ratio predicted by our calculation is larger than that obtained from our experiments. This discrepancy may be attributed to the significant disorder arising from the randomly distributed split sites and dopants in the selected FCGT samples. These introduce additional scattering effects not accounted for in our calculations, and hence significantly suppress the TMR ratio, especially at high temperatures. With this in mind, enhanced TMR and higher operational temperatures may be made possible in AFMTJs by utilizing vdW A-type AFM electrodes with more ordered structures.

We note a recent study reporting TMR in MTJs with (Fe0.8Co0.2)3GaTe2 (FCGaT) electrodes and WSe2 barriers39. Crucially, this TMR originated from a field-induced AFM-FM phase transition, where high-resistance states emerge when one electrode remains AFM while the other becomes FM. This is in contrast to our system, in which the FCGT exhibits TMR in the all-AFM state without bulk FM phase involvement and with inherent elimination of stray fields – a critical advantage for high-density integration. The divergent behaviors between FCGT and FCGaT likely stem from differences in exchange coupling strengths, magnetic anisotropy energies, interfacial cleanliness, and transfer methodologies—aspects warranting future investigation.

Our work demonstrates that uncompensated interfaces fulfill dual critical functions. They generate spin-polarized tunneling currents for magnetoresistive read-out and enable direct bulk Néel vector control for efficient write-in operations in all-AFM spintronic devices. A promising avenue for future exploration would be to use ultrafast optical method to directly detect the Néel vectors switching to study AFM dynamics and to manipulate the Néel vectors with the interface-assisted spin-orbit torque for all-electric AFM spintronic devices, as suggested recently28,40,41. Since most antiferromagnets exhibit uncompensated interfaces along selected growth directions, our approach suggests the possibility to exploit antiferromagnets previously viewed as “spin-independent” for spintronics, establishing a new device engineering paradigm.

In summary, we demonstrate that all-collinear AFMTJs can be successfully constructed as vdW heterostructures using standard techniques. These devices have achieved a TMR comparable to that of conventional MTJs. The A-type AFM stacking of the vdW electrodes facilitates convenient switching and supports nonvolatile TMR with no need for an additional pinning layer. The performance of these AFMTJs is largely unaffected by the thicknesses of the electrodes and barriers. These findings directly corroborate the theoretical proposal of interface-controlled collinear AFMTJs38 and distinguish them from existing noncollinear AFMTJs. From a technological point of view, these exceptional characteristics, combined with the inherent advantages of antiferromagnets, herald significant potential for next-generation MRAM applications.

Methods

Crystal

Single-crystal FCGT was grown by the chemical vapor transport method. Full details can be found in our earlier work17. Single-crystal WSe2 was purchased from HQ graphene.

Device fabrication and transport measurements

The FCGT and WSe2 flakes were exfoliated onto SiO2(300 nm)/Si substrates using blue tape. Ti/Au (5 nm/25 nm) contacts were patterned by photolithography and e-beam lithography and deposited by magnetron sputtering. Finally, devices were fabricated based on the dry transfer method42. The FCGT, WSe₂, and FCGT flakes were sequentially picked up by polydimethylsiloxane/polycarbonate (PDMS/PC) and then transferred onto SiO2/Si chips supporting the pre-patterned Ti/Au electrodes. The entire exfoliation and transfer process was carried out under inert conditions in an Ar-filled glovebox with O₂ and H₂O concentrations below 0.1 ppm.

Transport measurements were made in a Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS) from Quantum Design, using an SRS Model CS580 and SR830 lock-in amplifier with a measurement frequency of 13.333 Hz.

Data processing for Hall measurements

Due to the non-symmetry of the Hall device, the Hall resistance Rxy was mixed with a small part of the longitudinal resistance Rxx. We processed the Rxy data by using the standard symmetrical formula (Rxy1(+B) - Rxy2 (-B))/2 to eliminate the contribution from Rxx, where Rxy1 and Rxy2 represent the Hall resistances measured during descending and ascending magnetic field sweeps, respectively, and B denotes the applied magnetic field. The TMR data are raw data and have not undergone symmetry processing.

First-principles calculations

First-principles calculations of the electronic structure were performed within the density functional theory (DFT)43 using the projector augmented-wave (PAW)44 method implemented in the VASP code45,46. The plane-wave cut-off energy was 500 eV. The k-point meshes used in the calculations were 12 × 12 × 6 for bulk Fe5GeTe2 and 12 × 12 × 1 for the vdW heterostructures. The exchange and correlation effects are treated within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) developed by Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)47. The semiempirical DFT-D3 method parameterizing the van der Waals correction was used in the calculations48.

The non-equilibrium Green’s function formalism (DFT + NEGF approach)49,50 was used to calculate quantum transport, which is implemented in QuantumATK51. The cut-off energy of 75 Ry, the nonrelativistic Fritz-Haber Institute (FHI) pseudopotentials, and \(\vec{k}\)-point meshes of 11 × 11 × 101 for Fe6GeTe2-based AFMTJs were used for self-consistent calculations. The \(\vec{k}\)-resolved transmission was calculated using 401 × 401 k-points in the two-dimensional (2D) Brillouin zone (BZ).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Žutić, I., Fabian, J. & Das Sarma, S. Spintronics: Fundamentals and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 323–410 (2004).

Chappert, C., Fert, A. & Van Dau, F. N. The emergence of spin electronics in data storage. Nat. Mater. 6, 813–823 (2007).

Dieny, B. et al. Opportunities and challenges for spintronics in the microelectronics industry. Nat. Electron. 3, 446–459 (2020).

Julliere, M. Tunneling between ferromagnetic films. Phys. Lett. A 54, 225–226 (1975).

Moodera, J. S., Kinder, L. R., Wong, T. M. & Meservey, R. Large magnetoresistance at room temperature in ferromagnetic thin film tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3273–3276 (1995).

Parkin, S. S. P. et al. Giant tunnelling magnetoresistance at room temperature with MgO (100) tunnel barriers. Nat. Mater. 3, 862–867 (2004).

Yuasa, S., Nagahama, T., Fukushima, A., Suzuki, Y. & Ando, K. Giant room-temperature magnetoresistance in single-crystal Fe/MgO/Fe magnetic tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 3, 868–871 (2004).

Tsymbal, E. Y., Mryasov, O. N. & LeClair, P. R. Spin-dependent tunnelling in magnetic tunnel junctions. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 15, R109–R142 (2003).

Baltz, V. et al. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015005 (2018).

Jungwirth, T., Marti, X., Wadley, P. & Wunderlich, J. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 231–241 (2016).

Jungwirth, T. et al. The multiple directions of antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Phys. 14, 200–203 (2018).

Shao, D.-F. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Antiferromagnetic tunnel junctions for spintronics. npj Spintronics 2, 13 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Octupole-driven magnetoresistance in an antiferromagnetic tunnel junction. Nature 613, 490–495 (2023).

Qin, P. et al. Room-temperature magnetoresistance in an all-antiferromagnetic tunnel junction. Nature 613, 485–489 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Twist-assisted all-antiferromagnetic tunnel junction in the atomic limit. Nature 632, 1045–1051 (2024).

Néel, L. Propriétés magnétiques du manganèse et du chrome en solution solide étendue. J. Phys. Radium 3, 160–171 (1932).

Hu, T. et al. Enhanced magnetic transition temperature through ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic interaction in cobalt-substituted Fe5GeTe2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 125, 022403 (2024).

Lu, L. et al. Tunable magnetism in atomically thin itinerant antiferromagnet with room-temperature ferromagnetic order. Nano Lett. 24, 5984–5992 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Room-temperature skyrmion lattice in a layered magnet (Fe(0.5)Co(0.5))(5)GeTe(2). Sci. Adv. 8, eabm7103 (2022).

Tian, C. et al. Tunable magnetic properties in van der Waals crystals (Fe1−xCox)5GeTe2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 202402 (2020).

May, A. F., Du, M.-H., Cooper, V. R. & McGuire, M. A. Tuning magnetic order in the van der Waals metal Fe5GeTe2 by cobalt substitution. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 074008 (2020).

Min, K.-H. et al. Tunable spin injection and detection across a van der Waals interface. Nat. Mater. 21, 1144–1149 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Tunneling spin valves based on Fe3GeTe2/hBN/Fe3GeTe2 van der Waals heterostructures. Nano Lett. 18, 4303–4308 (2018).

Zheng, Y. et al. Spin filtering effect in all-van der Waals heterostructures with WSe2 barriers. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 6, 62 (2022).

Zhu, W. et al. Large tunneling magnetoresistance in van der Waals ferromagnet/semiconductor heterojunctions. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104658 (2021).

Zhu, W. et al. Large room-temperature magnetoresistance in van der Waals ferromagnet/semiconductor junctions. Chin. Phys. Lett. 39, 128501 (2022).

Jin, W. et al. Room-temperature and tunable tunneling magnetoresistance in Fe3GaTe2-Based 2D van der Waals heterojunctions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 36519–36526 (2023).

He, W. et al. Electrical switching of the perpendicular Néel order in a collinear antiferromagnet. Nat. Electron. 7, 975–983 (2024).

Manna, P. K. & Yusuf, S. M. Two interface effects: Exchange bias and magnetic proximity. Phys. Rep. 535, 61–99 (2014).

Liu, C. et al. Emergent, non-aging, extendable, and rechargeable exchange bias in 2D Fe3GeTe2 homostructures induced by moderate pressuring. Adv. Mater. 35, 2203411 (2022).

Gweon, H. K. et al. Exchange bias in weakly interlayer-coupled van der Waals magnet Fe3GeTe2. Nano Lett. 21, 1672–1678 (2021).

Liu, D. et al. Manipulation of exchange bias in two-dimensional van der Waals ferromagnet near room temperature. ACS Nano 18, 23812–23822 (2024).

Zheng, G. et al. Gate-tuned interlayer coupling in van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2 nanoflakes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 047202 (2020).

Shao, D.-F., Zhang, S.-H., Li, M., Eom, C.-B. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Spin-neutral currents for spintronics. Nat. Commun. 12, 7061 (2021).

Šmejkal, L., Hellenes, A. B., González-Hernández, R., Sinova, J. & Jungwirth, T. Giant and tunneling magnetoresistance in unconventional collinear antiferromagnets with nonrelativistic spin-momentum coupling. Phys. Rev. X 12, 011028 (2022).

Shao, D.-F. et al. Néel Spin Currents in Antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 216702 (2023).

Zhang, S.-S. et al. X-type stacking in cross-chain antiferromagnets. Newton, 1, 100068, (2025).

Yang, L. et al. Interface-controlled antiferromagnetic tunnel junctions. Newton, 1, 100142, (2025).

Jin, W. et al. Nonvolatile multistate magnetoresistance in all-van der Waals antiferromagnet-based spin valves. Appl. Phys. Lett. 126, 152403 (2025).

Guo, H. et al. Layer-dependent field-free switching of Néel vector in a van der Waals antiferromagnet. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.06764 https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.06764 (2025).

Zhang, S.-S. et al. Deterministic switching of the néel vector by asymmetric spin torque. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.10786 https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.10786 (2025).

Wang, L. et al. One-dimensional electrical contact to a two-dimensional material. Science 342, 614–617 (2013).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initiototal-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Andreev, A. F. Macroscopic magnetic fields of antiferromagnets. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett. 63, 758–762 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Brandbyge, M., Mozos, J.-L., Ordejón, P., Taylor, J. & Stokbro, K. Density-functional method for nonequilibrium electron transport. Phys. Rev. B 65, 165401 (2002).

Taylor, J., Guo, H. & Wang, J. Ab initiomodeling of quantum transport properties of molecular electronic devices. Phys. Rev. B 63, 245407 (2001).

Smidstrup, S. et al. QuantumATK: an integrated platform of electronic and atomic-scale modelling tools. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 32, 015901 (2019).

Acknowledgements

L.W. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 12374177), L.Y. and D.F.S was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant no. 2024YFB3614101), the National Science Foundation of China (NSFC Grants no. 12274411, 12241405, and 52250418), the Basic Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Based on Major Scientific Infrastructures (No. JZHKYPT-2021-08), and the CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (No. YSBR-084). W.-M. Z was supported by the Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant no. 2408085QA011). The calculations were performed at Hefei Advanced Computing Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W. and D.-F.S. conceived the project. Y.-L.L. and W.-M. Z. fabricated the devices, performed the transport measurements and data analysis, assisted by C.T., Y.Y., Z.Z., M.C., T.Y., and L.W. R.H., G.W. and M.T. synthesized the FCGT crystals. L.Y. and D.-F.S. performed the theoretical analyses and calculations. W.-M.Z., D.-F. S., J.P., and L.W. wrote the manuscript with assistance from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, WM., Liu, YL., Yang, L. et al. Interface-controlled antiferromagnetic tunnel junctions based on a metallic van der Waals A-type antiferromagnet. Nat Commun 17, 268 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66981-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66981-5