Abstract

Rising vehicle Mach numbers urgently necessitate broadband electromagnetic wave (EMW) absorbers capable of operating at even higher temperatures while maintaining environmental durability. However, Current high-temperature EMW absorbing materials face the restriction and temperature-sensitivity of dielectric frequency-dispersion (FD), which often forces reliance on complex macro-structures to broaden effective absorption bandwidth (EAB). Here, inspired by the concept of finite element method, we propose a controlled FD regulation strategy to overcome this by employing multivariate ultra-high temperature ceramic (UHTC) borides with tunable surface oxide thickness. The fabricated material (without structural design) yields a broad EAB of 26.98 GHz at just 2.8 mm thickness, alongside environmental resistance. Crucially, the multivariate polarization remains effective for FD regulation even at 1473 K, enabling our material to harvest an EAB of 10.26 GHz after applying an oxide layer, showing bright application prospects for the stealth of high-speed vehicles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rising Mach numbers in high-speed stealth vehicles expose their thermal components to extreme dynamic thermal environments, such as higher operating temperatures and severe oxidation. These parts are the main electromagnetic wave (EMW) scattering sources, which must be suppressed to avoid exposure to modern multi-band electromagnetic detection systems1,2. However, aircraft exterior design alone cannot achieve omnidirectional stealth under propulsion and harsh environmental constraints, necessitating the development of high-temperature electromagnetic wave absorbing (EMWA) materials. Ceramic or ceramic-based composites, as conventional high-temperature EMWA materials, inevitably face a challenge in matching dielectric frequency-dispersion (FD) control with elevated temperatures, severely restricting their EMW absorption performance under higher temperatures (below 1000 °C at present)3,4,5,6,7. While macro-structural designs (e.g., metamaterials) can enhance EMW absorption bandwidth, their structural complexity impedes functional integration in high-temperature components. Therefore, the fundamental issue lies in establishing an intrinsic FD engineering regulation principle to stabilize dielectric response across a broad temperature range.

Theoretical calculations show that 99.999% absorption (reflection loss (RL) values of −50 dB) can be achieved across the 1-4 mm thickness range when the ideal real part and imaginary part of permittivity (εʹ and ε") values exhibit a rapid frequency (f) dependent attenuation. This characteristic enables a full-band absorption spanning 2-18 GHz at a single thickness, as shown in Fig. 1a-f. Thus, the design of broadband EMWA materials necessitates strong and strict FD features. Furthermore, ideal permittivity profiles highlight more pronounced FD characteristics for εʹ than ε", indicating εʹ-f necessitates a steeper decline rate. Debye theory (Supplementary Equations (1, 2))8 dictates that the variation in εʹ values is governed by polarization mechanisms, while ε" is co-governed by conduction loss part (εc") and polarization loss (εp"). The partial derivative of εc" versus frequency decay is \(-\frac{\sigma }{2\pi {\varepsilon }_{0}{f}^{2}}\). For ceramic materials with low σ, the denominator predominates at 2-18 GHz, resulting in a quite small magnitude of this attenuation. This demonstrates that optimizing FD characteristics solely by changing conductivity is infeasible, so the primary focus should be on modulating polarization loss. The Debye theory elucidates that polarization mechanisms and polarization relaxation time (τ) directly govern the variations of permittivity εr. As the frequency of the external electric field increases, electronic and dipolar polarizations fail to synchronize with the alternating field, resulting in a frequency-dependent reduction in practical permittivity9. Furthermore, by independently tuning ε∞, εs, and σ parameters in Supplementary equations (1, 2), we plotted the relationship between εr and τ, as shown in the normalized Fig. 1g. It is apparent that increasing τ enhances FD characteristics of εr (Fig. 1h), progressively approaching ideal permittivity profiles (Fig. 1a, b). Therefore, strategic τ tuning and polarization enhancement are potential approaches for optimizing FD behavior.

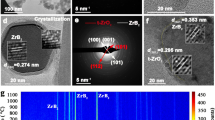

a, b The simulated ideal range of εʹ and ε" values corresponds to material’s thickness from 1 to 4 mm with an absorption efficiency of 99.999%. c−f Two-dimensional (2D) RL projection achieved with a specific thickness (1−4 mm) of the simulated permittivity, where the red dotted line represents RL = −10 dB. g The calculated real and imaginary parts of the normalized permittivity at different τ from 1 ps to 100 ps. h, i Schematic diagram of FD features influenced by τ and the permittivity regulated by multiple components. j, k TEM micrographs of the UHTC borides before and after heat treatment. l The statistical chart of the amorphous layer thickness before and after heat treatment. (Data are shown as mean ± s.d. from n = 8 independent samples). m, n Electrical conductivity (Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from n = 4 independent samples) and electron migration schematic between two boride particles before and after heat treatment.

Heterogeneous interface engineering10,11,12,13, particularly the construction of Schottky interfaces via conductor-semiconductor integration14,15,16, provides a straightforward pathway for enhancing interface polarization effects. The work function (WF) difference drives directional electron migration at the interface, resulting in an uneven charge distribution and strengthened polarization17. However, achieving stringent FD requirements remains challenging with single or dual-component systems. Inspired by finite element analysis (FEA) method, finer meshing will yield results that converge towards the exact solution, providing a close approximation to reality. Therefore, we propose increasing the number of absorbing components (analogous to increasing the number of finite elements), which leverages the distinct dielectric properties of individual components to synergistically optimize the composite’s FD properties, thus gradually approaching the ideal dielectric FD profile and achieve the desired frequency response (Fig. 1i). Guided by this concept, we selected multi-component ultra-high-temperature ceramic (UHTC) borides (ZrB2, TiB2, NbB2, HfB2, and TaB2) as the absorbing phase. Their unique dielectric properties (Supplementary Fig. 1) alongside excellent thermal stability, oxidation resistance, and ablation resistance18 ensure composite compatibility and stability in extreme environments. Additionally, the integrated multiphase absorber system can further enhance polarization effects and EMW energy dissipation19,20.

In this study, we propose a feasible strategy for dielectric FD engineering modulation from room temperature (RT) to high-temperature conditions by computationally designed composites of polymer-derived SiOC ceramic (PDC-SiOC) and multi-borides (MB). Strategic tuning of MB ratios and surface oxide thickness prolongs τ and strengthens polarization effects, thereby optimizing the dielectric FD behavior. The fabricated MB/SiOC system achieves an ultra-broad effective absorption bandwidth (EAB) of 26.98 GHz with a thickness of 2.8 mm. Notably, multivariate polarization and thermal stability of the MB absorber enable the multiphase-modulation mechanism for broadening EAB via FD to remain effective even at 1473 K, maintaining an EAB of 7.54 GHz (within a 2-18 GHz range). The EAB further increases to 10.26 GHz after applying an antioxidant layer, surpassing the reported high-temperature EWMA materials. This work provides a meaningful insight into the rational design of high-performance wide-band EWMA materials suitable for extreme high-temperature environments.

Results and Discussion

Design and Simulation

The permittivity of multi-component composites is intimately influenced by the dielectric properties of their constituent and corresponding volume fractions, as expressed in Supplementary Equation (3)21. Thus, to determine the optimal content of each UHTC boride, a thorough analysis of the physical features of various UHTC borides and their corresponding composites is performed. Figure 1j and Supplementary Fig. 2 present the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns and micrographs of pristine UHTC borides (ZrB2, TiB2, NbB2, HfB2, and TaB2), revealing that the nanoscale ceramic powder is encapsulated by an amorphous B2O3 layer formed during raw material synthesis, as shown in Supplementary Equations (4-7). Following the incorporation of 40 wt. % (optimal ZrB2 content for EMWA22) mono-component boride absorbers into polysiloxanes (PSO) and subsequent pyrolysis at 1000 °C, a series of ceramic composites were synthesized (named as S-boride-40, with S representing the SiOC), with their composition and EM properties illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 3, 4. The samples exhibit a narrow EAB with a sample thickness exceeding 8 mm, which is influenced by the amorphous B2O3 layer on the UHTC borides that hinders electron transport and reduces the EWM attenuation capability. To facilitate the electron transport, all raw powders were subjected to high-temperature treatment (600 °C for 3 h in Ar), labeled as ZrB2′, TiB2′, NbB2′, HfB2′, and TaB2′, respectively. As observed in Fig. 1k, l, and Supplementary Fig. 5, the thickness of the amorphous B2O3 layer on the boride powder surfaces decreased obviously following heat treatment, which is beneficial in reducing the hindrance to electron transport and enhancing electrical conductivity (Fig. 1m, n).

The treated mono-component UHTC borides (40 wt. %) were compounded with PSO to fabricate a series of composites (labeled as S-boride′-40), and the electromagnetic (EM) properties are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6 (a-h). All samples exhibit an increased complex permittivity and improved EMWA performance, attributed to the elevated conductivity (Supplementary Fig. 6i) and more obvious FD features in their permittivity. Notably, the position of the relaxation peak in ε" for the S-boride’-40 ceramic composites shows a distinct shift compared to the S-boride-40 samples. According to Debye theory, ε" is co-governed by εc" and εp". To further observe the change of relaxation peak position, we separately calculated the contribution of εc" and εp" by Supplementary Equation (2). The results, shown in Supplementary Figs. 7a, b and 9a, b, reveal that the primary relaxation peak in εp" of the S-boride′-40 composites shifts towards lower frequencies. Theoretically, this peak shift signifies a change in the τ, which can be determined using Supplementary Equation (8)23. The calculated result indicates that the τ for the S-boride-40 samples were 12.21 ps, 11.50 ps, 13.17 ps, 9.80 ps and 10.69 ps (Supplementary Fig. 7c). In contrast, for the S-boride′-40 composites, the high-frequency relaxation peak diminished and shifted to lower frequencies, with corresponding τ values increasing to 23.13 ps, 13.08 ps, 16.31 ps, 12.20 ps, and 12.67 ps (Supplementary Fig. 9c). Furthermore, the time-domain spectra for these samples were plotted and fitted, and the τ obtained from this analysis exhibit similar values (Supplementary Figs. 7d, e, 8, and 9d, e), which strongly supports the reliability of the calculated τ values.

First-principles calculations were employed to investigate the underlying mechanism responsible for the interfacial interaction influencing τ across different B2O3 thicknesses (using ZrB2/B2O3 as an example). We conducted two heterointerface models for ZrB2 with different B2O3 thicknesses, labeled as ZrB2/B2O3 (thin) and ZrB2/B2O3 (thick), and calculated their interfacial adsorption energies (Eads), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10a. The Eads of -0.305 eV/Ų for ZrB2/B2O3 (thin) is significantly lower than that of -0.148 eV/Ų for ZrB2/B2O3 (thick) heterointerface, which indicates that reducing the B2O3 thickness enhances the attractive interaction at the ZrB2/B2O3 interface and leads to stronger interfacial binding. The dipole moments and corresponding polarizability of two models under varying external electric field strengths were calculated, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 10b-d. The results demonstrate that the ZrB2/B2O3 (thin) heterostructure consistently exhibits a larger dipole moment and higher polarizability under the varying electric fields. The reduction in B2O3 thickness induced by heat treatment strengthens the ZrB2/B2O3 heterointerfacial interaction. This enhanced interaction promotes greater interfacial charge separation and increases the interfacial dipole moment, thereby extending τ and resulting in more pronounced dielectric FD characteristics.

Subsequently, we modulated the content of mono-component UHTC absorbers in SiOC ceramic to 50 wt. % and 60 wt. % (labeled as S-boride′-50 and S-boride′-60, respectively), the corresponding permittivity and EMWA properties were measured and illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12. Based on the EMW absorption results of S-boride′ ceramic composites, the optimal mono-component UHTC boride contents are identified, namely ZrB2′-40 wt. %, TiB2′- 40 wt. %, NbB2′-50 wt. %, HfB2′-50 wt. %, and TaB2′-60 wt. %, and this series of components is denoted as S-boride′-A. Subsequently, the volume fraction in each component of SiOC-multi-boride′ (S-MB) ceramic composites was calculated using commercial Matlab software, guided by the ideal permittivity (Fig. 1a, b) and the acquired complex permittivity of mono-component S-boride'-40/50/60 ceramic composites (detailed information is shown in Supplementary Table 2). To elevate the calculation accuracy, the frequency range was narrowed to 6-18 GHz, and the results obtained from this range will serve as the basis for subsequent experiments. The reason for using the 6-18 GHz range and an in-depth analysis of the calculation process are available in the Supplementary Figs. 13-16 and Supplementary Table 1.

Preparation and Structural Analysis

Based on the simulated results in Supplementary Table 2, the S-MB ceramic composites were prepared, which are labeled as S-MB-40, S-MB-50, S-MB-60, and S-MB-A, respectively. The detailed preparation process is illustrated in Fig. 2a. Liquid polysiloxanes pyrolyzed at 1000 °C were employed to construct a transparent matrix, MB absorbers were uniformly dispersed within the SiOC matrix to assist in establishing a conductive network, facilitating the effective EMW absorption. The crystal phase composition of the samples was analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD), as depicted in Fig. 2b. The crystallization of PDC-SiOC ceramic is incomplete at 1000 °C, leaving an amorphous phase without distinct diffraction peaks in the XRD patterns. Meanwhile, the XRD refinement exhibits diffraction peaks of multivariate UHTC borides (ZrB2, TiB2, NbB2, HfB2, and TaB2), along with calculated weight fractions consistent with the experimental data in Supplementary Table 3.

a Schematic illustration of the synthesis route for the S-MB ceramic composites. The synthesis involves (1) pre-treatment of multi-borides to reduce the surface B2O3 layer, (2) mixing and cross-linking of the pre-treated powders with a PDC-SiOC precursor, (3) mechanical processing into a green body, and (4) high-temperature pyrolysis to obtain the final S-MB ceramic composites. b XRD pattern of S-MB ceramic composites with different absorber contents. c SEM and corresponding elemental mapping images of S-MB-A. d BSE image. e CT analysis of S-MB-A, where black represents the S-MB-A sample, blue corresponds to the PDC-SiOC phase, pink indicates the pores, and red shows the multi-borides.

In addition, the information about the carbon structure change in the S-MB ceramic composite was analyzed by Raman spectroscopy, demonstrating the similar orderliness of the carbon phase in various samples (detailed in Supplementary Fig. 17). Furthermore, the detailed microscopic morphology of S-MB ceramic composites is shown in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 18, disclosing the presence of multiple pores amidst the SiOC matrix. During the transformation process from polymers to ceramics, the rapid release of gaseous byproducts can induce local pressure imbalances, resulting in stress concentration and the development of pores during material shrinkage. Backscattered electron microscopy (BSE), Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping, and point analysis proved the well-defined MB absorbers within the SiOC ceramic (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 19). Synchronously, Computed Tomography (CT) was employed to observe the spatial distribution of SiOC ceramic, pores, and MB absorbers within the S-MB-A samples (Fig. 2e). The CT cross-section image and corresponding enlarged view reveal that the MB absorbers are uniformly distributed in the SiOC ceramics.

Electromagnetic parameters and EMWA performance

Figure 3a–c show the permittivity of the S-MB ceramic composites over the frequency range of 2–18 GHz. Gratifyingly, the S-MB samples exhibit obvious dielectric FD features superior to those of S-boride′-40/50/60 ceramic composites containing mono-component absorbers, which proves the efficacy of our approach to enhance the dielectric FD properties of composites through the synergistic interaction of MB absorbers. The S-MB-50 and S-MB-60 samples exhibit lower permittivity values, attributed to their higher porosity (Supplementary Fig. 20). Furthermore, the MB absorbers provide various heterogeneous interfaces that facilitate space-charge accumulation and improve dielectric loss capacity, evidenced by the high tan δε (Fig. 3d). Cole-Cole curve was drawn according to Debye’s theory and Supplementary Equation (9) to analyze the dielectric loss mechanism24, as interpreted in Fig. 3e, f. All S-MB samples display clear semicircles in Cole-Cole plots, with varying radii, reflecting their multiple polarization relaxation processes within the ceramic composites. Additionally, Cole-Cole plots reveal distinct linear segments (red lines in Fig. 3e, f) corresponding to conduction loss25. This type of loss primarily originates from migrating and hopping electrons within the electronic transmission channel of MB absorbers, which converts the EMW energy into thermal energy via ohmic dissipation. To further determine the contribution of the conduction loss and polarization loss, we calculated the εc", εp", and their proportions on the basis of Supplementary Equation (2) and imaginary permittivity of the S-MB ceramic composites26, as depicted in Fig. 3g, h and Supplementary Fig. 21a, b. The results clearly demonstrate that polarization loss dominates the attenuation mechanism, with its contribution progressively increasing at higher frequencies. Notably, the S-MB composites provide significantly stronger polarization attenuation compared to mono-component boride ceramic composites (Supplementary Fig. 21c), attributable to the abundance of heterogeneous interfaces introduced by the incorporated MB. Theoretically, such intense polarization processes are accompanied by relaxation phenomena as the frequency of the external electric field increases. The interfacial dipoles fail to follow and respond effectively to the oscillation frequency of the external field, leading to a decrease in the real permittivity and consequently enhanced dielectric FD characteristics27.

a−d The real and imaginary parts of permittivity and loss tangent (tan δε) of S-MB ceramic composites. e, f Cole-Cole curves of S-MB ceramic composites. g, h Conduction loss and polarization loss in S-MB ceramic composites. i Polarization relaxation time τ of S-MB samples. j High-resolution TEM micrograph of sample S-MB-A, along with enlarged views of the corresponding regions 1-6 and their indexed FFT patterns. The yellow dashed lines highlight the heterointerfaces formed between the PDC-SiOC and the multi-borides.

Importantly, we observed shifts in the primary relaxation peak position in the εp"-f relationship of the S-MB samples. The S-MB-40 sample exhibits its primary relaxation peak at 10.72 GHz, resulting from abundant interfacial and dipole polarization. Changes in the polarization process induced by increasing MB content cause the relaxation peak to shift to 9.68 GHz for S-MB-50 and 8.88 GHz for S-MB-60. The S-MB-A sample displays a sharp relaxation peak at 5.20 GHz. By employing Supplementary Equation (8), we determined the corresponding τ as 14.85 ps, 16.44 ps, 17.92 ps, and 30.61 ps, respectively (Fig. 3i). The time-domain spectra and fitted results are presented in Supplementary Fig. 22, along with high coefficients of determination (R2 > 0.95) support the reliability of the acquired τ values. Owing to the synergistic regulation mechanism of the MB and significantly prolonged relaxation time, the S-MB-A exhibits the most prominent dielectric FD features, corroborating our computational optimization results.

To comprehensively observe the heterogeneous interfaces within the ceramic composites, the detailed microstructure and lattice information of the S-MB samples were analyzed using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) (Fig. 3j). Obviously, SiOC ceramic predominantly exhibits an amorphous phase, evidenced by the corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT). The EDS mapping analysis (Supplementary Fig. 23) and the enlarged high-resolution images (Regions 2-6) reveal well-defined heterogeneous interfaces. Furthermore, the corresponding indexed FFT patterns confirm the presence of MB phase, with measured interplanar spacings of 0.275 nm, 0.325 nm, 0.205 nm, 0.214 nm, and 0.266 nm, corresponding to the (100) plane of ZrB2, (001) of TiB2, (011) of NbB2, (101) of HfB2, and (100) of TaB2, respectively. These high-density heterogeneous interfaces are pivotal in enhancing interfacial polarization and modulating dielectric FD features.

Subsequently, the types of high-density heterogeneous interfaces and corresponding electronic transfer mechanisms are explored. In this study, MB is regarded as possessing conductor properties, whereas SiOC ceramic pyrolyzed at 1000 °C demonstrates semiconductor properties28. According to solid-state band theory, the difference in WF between the conductor and the semiconductor profoundly affects interfacial electron transfer in heterostructures29,30. Theoretically, establishing the Schottky interface first necessitates that the WF of the conductor is lower than that of the semiconductor, implying a lower energy requirement for electron transfer from the conductor to the external vacuum31. Additionally, the conductor’s Fermi level (EF) should be situated between the conduction and valence bands of the semiconductor32,33. When both conditions are met, a Schottky contact forms, enabling spontaneously electron migrate from the conductor to the semiconductor, resulting in self-driven charge redistribution at the heterogeneous interfaces. Based on this theory, the WF and band gap of the PDC-SiOC and MB absorbers were measured, as depicted in Fig. 4a, b (detailed calculations in Supplementary Figs. 24, 25). The results confirm that the WF of PDC-SiOC is 3.58 eV, apparently higher than that of UHTC borides', thus meeting the first requirement. Furthermore, taking ZrB2′ as an example, its band gap is only 0.45 eV, while that of PDC-SiOC is 1.88 eV. This satisfies the condition that the EF of ZrB2′ resides within the band gap of PDC-SiOC (Fig. 4c). Consequently, when PDC-SiOC and ZrB2′ are in contact, a Schottky contact forms, and the energy bands of SiOC bend upwards to align with the EF of ZrB2′. This alignment facilitates the spontaneous transfer of electrons from ZrB2′ to SiOC, creating a rapid electron transfer pathway that leads to electron redistribution at the heterogeneous interface. Importantly, the MB fulfill the criteria for creating Schottky heterointerfaces when contacted with the SiOC ceramic, thereby establishing multi-Schottky heterojunctions within ceramic composites. The face-to-face contact between SiOC and MB absorbers induces directional electron transfer from the UHTC borides to SiOC, along with generating extensive space-charge regions and the built-in electric field (BIEF), as shown in Fig. 4d14. When subjected to an applied alternating EM field, the accumulated and unevenly distributed charges undergo forced rearrangement, aligning them with the direction of the external EM field34,35. Consequently, the polarization relaxation processes arising from both the BIEF with distinct orientations and the applied EM fields establish a dynamic equilibrium, which results in the violent dissipation of EM energy. This intensified polarization relaxation mechanism not only strengthens the EM response after the formation of Schokkty heterointerfaces but also improves the dielectric FD characteristics of the composites36.

a, b The work function (WF) and band gap (Eg) of SiOC and UHTC borides, respectively. c Schematic illustration of electric transport before and after contact, where Evac, EF, Ec, and Ev represent the vacuum level, Fermi level, conduction band, and valence band, respectively. d Schematic diagram illustrating that the WF difference between PDC-SiOC and UHTC borides leads to the formation of a space charge region and the associated built-in electric field (BIEF) at their heterogeneous interface upon contact. e The schematic illustrates the mechanism underlying interfacial charge transport in scenarios where the applied electric field is oriented along and opposite to the original BIEF. FS, FE, and FB represent the driving force from the Schottky contact, external field, and BIEF, respectively.

Density functional theory (DFT) was employed to investigate the charge density distribution at the heterogeneous interface between SiOC, B2O3, and MB (ZrB2 as an example) to verify the aforementioned electron transfer mechanism. The crystal structure of ZrB2, B2O3, and SiOC (depicted in Supplementary Fig. 26a) was employed to construct the ZrB2/B2O3 and B2O3/SiOC interfacial models, followed by geometry optimization of both interfaces. The charge is redistributed at the interface, which results in electron accumulation at the B2O3 interface and electron depletion at the ZrB2 interface (Supplementary Fig. 26b). Synchronously, the charge density difference and corresponding 2D projection illustrate the electron transfer from B2O3 to SiOC (Supplementary Fig. 26c). These results are consistent with previous analyses, confirming electron migration from the MB to the SiOC ceramic. Based on these findings, Fig. 4e analyzes the charge transfer mechanism within the BIEF under an applied external electric field. Due to the WF differences and the driving force (FS) originating from Schottky contact formation, directional electron migration occurs at the MB/B2O3 and B2O3/SiOC heterointerfaces, generating a spontaneous BIEF37. When the applied electric field aligns with the BIEF direction, the driving force of the external field (FE) causes the electrons initially concentrated on the B2O3 and SiOC side to dissipate gradually and migrate to the opposite direction. This migration process is impeded by the driving force FS from Schottky contact formation, establishing an oscillatory polarization relaxation process for space charges under the alternating electric field. Conversely, when the applied electric field opposes the BIEF direction, the driving force FE enhances charge separation. Electrons tend to accumulate towards the B2O3 and SiOC side until a new dynamic equilibrium is reached with the opposing force (FB) from the BIEF38. Consequently, the most efficient interfacial polarization occurs when the direction of the applied EMW aligns with the spontaneously formed BIEF direction. The S-MB sample possesses abundant heterointerfaces. The cumulative effects of the polarization relaxation processes occurring between the BIEF at these interfaces and the external EM field is capable of causing significant dielectric FD behavior and intense dissipation of EMW energy.

To further validate this effect, the EMWA performance of the S-MB ceramic composites was evaluated based on the transmission line theory (expressed by the Supplementary Equations (10, 11))39, as shown in Fig. 5a–d. Benefiting from the strengthened FD features and robust cooperative loss capability of MB, the S-MB samples harvest excellent EMW absorption performance. Specifically, an EAB of 10.08 GHz can be achieved for sample S-MB-A at a thickness of 2.8 mm, spanning the entire X, Ku bands, and part of the C band. Interestingly, our results are almost consistent with earlier computational predictions (Supplementary Fig. 16l), validating the significant role of multivariate absorbers in synergistically tuning the dielectric property of the composites and expanding the EAB. Moreover, samples S-MB-40, S-MB-50, and S-MB-60 also exhibit good EMW absorbing ability, with EAB values of 8.48 GHz, 8.88 GHz, and 6.48 GHz at a thickness of 2.4 mm, 3.2 mm, and 3.2 mm, respectively. Simultaneously, a much lower minimal reflection loss (RLmin) value of -49.05 dB, -57.02 dB, and -46.70 dB is obtained at a thickness of 2.1 mm, 6.4 mm, and 3.1 mm, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 27a).

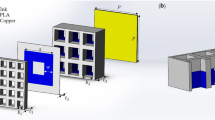

a−d 2D RL projection of S-MB ceramic composites, where the red dotted line represents RL = -10 dB. e−h 2D impedance matching degree (Δ) projection of S-MB ceramic composites, where the Δ < 0.4 represents the ideal impedance-matching. i, j Schematic diagram of target detection for aircraft by radar and simulation model, respectively. k RCS simulation curve compared to pure PEC substrate. l RCS reduction at specific angles. m, n 3D RCS value and corresponding 2D projection plots for the PEC substrate covered with S-MB materials.

Generally, excellent absorption performance always means good impedance-matching (Z) and strong attenuation constant (α)40, which can be expressed by the Supplementary Equations (12, 13)41. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 27b, the α for S-MB samples exhibits a progressive increase with frequency, only displaying minor variations in α values. Therefore, impedance-matching (Z) emerges as a critical factor in determining the EMW absorbing ability. The impedance-matching degree (Δ) was often selected to characterize the impedance-matching, as explicated in Supplementary Equations (14-16)42. In general, │Δ│ < 0.4 should be considered as ideal impedance-matching43. Supplementary Fig. 28 displays the 2D projection of Δ values corresponding to the ideal permittivity in the 1-4 mm thickness range. The results demonstrate that the dielectric constant with robust FD characteristics, which is typically accompanied by strong EMW absorption and favorable impedance-matching capabilities, enables a broad │Δ│ < 0.4 region spanning the entire 2–18 GHz under single-thickness conditions. As a consequence, the modulation of dielectric FD characteristics is beneficial for obtaining optimal impedance-matching, thereby achieving broadband EMW absorption. Notably, Fig. 5e–h reveals that sample S-MB-A occupies a larger area (│Δ│ < 0.4) within the same thickness range. Furthermore, S-MB-A demonstrates more pronounced FD features and superior attenuation ability, thus achieving optimal EMW absorption. To further verify the potential of the S-MB ceramic composites for practical applications of stealth technology (Fig. 5i), the Radar cross-section (RCS) simulation was conducted using CST Microwave Studio. The RCS value (σ) can be determined by theta and phi in spherical coordinates, which can be described in Supplementary Equation (17)44. Based on the obtained EM properties and parameters, the simulation model was established (Fig. 5j), which features a perfect electric conductor (PEC) plane with a 3D dimension of 180×180×0.5 mm and surface-coated with different S-MB EMW absorption material. Utilizing a plane wave as the excitation source, with the theta (θ) swept from -90° to 90°, and the specific frequency points of simulation are depicted in Supplementary Table 4. The stealth performance is obtained and depicted in Fig. 5m, n. Compared to the pure PEC plate, the RCS signal is significantly reduced after integrating with S-MB materials, with noticeable attenuation in the radiation structure and color change, indicating a substantial dissipation of EMW energy. Figure 5k illustrates the specific RCS values for the S-MB-coated sample across the angle range of -90° < θ < 90°. The average RCS values are consistently below -20 dBm2, in contrast to the pure PEC plate, with concrete reduction values shown in Fig. 5l. These results are consistent with excellent absorption properties obtained above, highlighting the considerable potential of S-MB ceramic composites for both civilian and military applications.

Thermal, chemical stability, and high-temperature EWM absorption properties

To evaluate the application potential for S-MB ceramic composites in harsh environments, the stability of S-MB samples was systematically investigated in high-temperature oxidation (1473 K) and acidic conditions (PH = 1), with detailed procedures provided in the Supplementary information. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 29a, b, post-oxidation macroscopic images of sample S-MB-A at different temperatures reveal negligible alterations, indicating a maintained structural integrity. Meanwhile, the weight variation curves of S-MB samples remain stable at 1073 K, demonstrating good thermal stability. Beyond this temperature, a minor mass increase was observed in the samples, suggesting oxidation reactions that capture atmospheric oxygen45. High-temperature XRD was employed to analyze phase transformation in sample S-MB-A (Fig. 6b), with the major diffraction peaks of MB gradually diminishing above 1073 K, accompanied by the formation of SiO2 and multi-oxide derivatives of MB. Supplementary Fig. 30a presents the SEM and BSE images of the sample S-MB-A after oxidation in air, revealing the formation of a molten phase encapsulating the MB absorbers. EDS mapping analysis confirms the enrichment of Si, Ta, Hf, Nb, and O elements in these regions, demonstrating multivariate oxide formation. In addition, the RL values of the samples after oxidation were evaluated (Supplementary Fig. 30c–f), revealing a little reduction in EWM absorption performance. Despite this, the EAB for samples S-MB-40, S-MB-50, and S-MB-A is 6.24 GHz, 6.40 GHz, and 7.28 GHz, at thicknesses of 2.9 mm, 3.0 mm, and 3.9 mm, respectively. This retention of absorption properties is attributed to the role of the multivariate oxide phase (Supplementary Fig. 31) in inhibiting oxygen diffusion, preventing the ceramic composites from being further oxidized, and preserving the multivariate polarization impacts of MB absorbers for dielectric FD control. Furthermore, these oxides typically exhibit lower permittivity, promoting the impedance matching with air and facilitating EMW penetration into the composites for absorption46. Simultaneously, we evaluate the stability of S-MB materials under strongly acidic conditions, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 29c and 30b. Both the relative mass and microstructure of samples remain almost unchanged, revealing the chemical stability of the UHTC boride ceramic and SiOC. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 30g–j, the EMW absorption performance of the samples remains stable, with an EAB of 9.80 GHz at a thickness of 2.8 mm for sample S-MB-A.

a The RL values in 2-40 GHz at room temperature. b high-temperature XRD pattern of sample S-MB-A. c Photos and specific size. d Photos of the high-temperature testing process. e The RL values as the temperature increases from 298 K−1473 K. f Comparison of high-temperature EMW absorption performance among recently reported literature5,6,7,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69. g Schematic illustration of the multiple EMW attenuation mechanisms and FD regulation of S-MB-A material at RT and 1473 K. g-1 Mechanisms of EMW attenuation and FD regulation at RT. g-2 Mechanisms of EMW attenuation and FD preservation at 1473 K. g-3 S-MB-A composite exhibits oxidation resistance and corrosion resistance.

Finally, a plate made of S-MB-A material with a standard size of 180 mm × 180 mm was fabricated to assess the EMW absorption performance from RT to 1473 K (Fig. 6c). Figure 6a presents a reflection curve of the S-MB-A plate at room temperature, with an EAB of 26.98 GHz within the frequency range of 2-40 GHz. Compared with other recently reported EMA absorption materials without 3D structure design, the S-MB-A plate not only illustrates an ultra-broad absorption but also has a thinner thickness (only 2.8 mm) (Supplementary Fig. 32 and Supplementary Table 5). Evaluating the EMW absorption performance of the materials over various incident angles is important for assessing their suitability in complex EM environments. Hence, we altered the angle between the two horns to observe the absorption changes. The S-MB-A plate maintains consistent performance without notable deterioration up to 40°, displaying excellent stability (Supplementary Fig. 33). The high-temperature EMW absorption performance of the S-MB-A plate was measured in the frequency range of 2-18 GHz, and the detailed testing process is shown in Fig. 6d. Figure 6e shows the high-temperature RL values of the S-MB-A plate from RT up to 1473 K. Exhilaratingly, the sample can maintain stable absorption of 12.03 GHz up to 873 K. As demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 34a, sample S-MB-A still exhibits pronounced dielectric FD characteristics at an elevated temperature of 873 K. This observation highlights the retained efficacy of multivariate polarization effects in MB for regulating dielectric FD behavior under high-temperature conditions (Supplementary Fig. 34b–d), which is pivotal for enabling EMW absorption at elevated temperatures across a wide frequency range in sample S-MB-A. Additionally, the EAB of the S-MB-A plate can reach 7.54 GHz when the temperature reaches 1473 K. Oxidation of the MB absorbers at elevated temperatures leads to reduced absorption in mid-frequency (X band). To address the performance degradation observed in S-MB-A plate, we proposed applying an anti-oxidation layer on the surface of the S-MB-A sample, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 35a, b. High-temperature dielectric and RL values (Supplementary Fig. 35c–f) demonstrate the remarkable thermal stability of the S-MB-A sample at 1473 K, with the oxide layer providing effective thermal protection. Fitting of the polarization loss indicates that the multivariate polarization effects arising from the MB remain operative even at 1473 K, resulting in dielectric properties that retain FD characteristics. Consequently, the S-MB-A plate maintains an EAB of 10.26 GHz at 1473 K, demonstrating a corresponding enhancement. To the best of our knowledge, the EMW absorption performance of S-MB-A plate surpasses other reported absorbing materials and achieves a breakthrough in absorption temperature (up to 1473 K). This represents a record, as shown in Fig. 6f (the relevant data are summarized in Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 6g elucidates the EMW absorption mechanism of our materials in harsh environments in detail. The engineered creation of multiple Schottky heterointerfaces drives directional electron migration, resulting in an uneven distribution of interfacial charges. These non-uniform charge distributions synergistically enhance the dynamic polarization process and dielectric FD characteristics, ultimately facilitating the EMW energy dissipation. Moreover, the electronic transport channel among the MB absorbers offers effective pathways for electron migration, encouraging the creation of conduction loss and facilitating EMW energy attenuation as heat. At high temperatures, the development of the oxide layer inhibits further oxidation of the ceramic composites, thereby retaining the multivariate polarization effects of MB absorbers for dielectric FD regulation and preserving the EMW attenuation capabilities. Benefiting from the above attenuation mechanisms, our ceramic composites maintain excellent EWM absorption capabilities when exposed to high-temperature oxidation and acidic environments. Hence, this confirms the reliable performance of the EMW-absorbing materials designed based on multicomponent UHTC borides in harsh conditions, highlighting their potential as high-performance radar-absorbing materials for extreme environmental applications.

In summary, an effective solution for enhancing EMW absorption bandwidth by improving material dielectric FD features is proposed in this work and validated by fabricating S-MB ceramic composites. By constructing multiple Schottky heterointerfaces and leveraging synergistic effects among MB absorbers, the relationship between permittivity and frequency of the studied materials is effectively regulated, with an ultra-EAB of 26.98 GHz at a thickness of 2.8 mm, simultaneously with satisfactory oxidation and corrosion resistance. Remarkably, the S-MB-A plate maintains distinguished EMW absorption even at a temperature of 1473 K, with an EAB of 10.26 GHz following application of an antioxidant layer, exceeding the previously reported high-temperature EMWA materials. Additionally, RCS simulation highlights the radar stealth potential of our material. This study not only offers reasonable insights for tuning the FD characteristic of EMWA materials but also provides valuable theoretical and technical guidance for the development of wide-band stealth materials in harsh environments.

Methods

Materials

All the chemicals used in our experiments, including polysiloxanes (PSO, colorless transparent liquid, density 0.992-0.994 g/cm3, viscosity 70-120 mPa∙s, ceramic yield > 78% at 1000 °C), Zirconium boride nanopowders (ZrB2, 99.9%), Titanium boride nanopowders (TiB2, 99.9%), supported by the Institute of Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences; Niobium boride nanopowders (NbB2, 99.9%), Hafnium boride nanopowders (HfB2, 99.9%), Tantalum boride nanopowders (TaB2, 99.9%), were commercially purchased from Shanghai Chaowei Nano Co., Ltd; ethanol (99.7%), provided by the Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Boron oxide powders (B2O3, 99.9 %), Silicon oxide powders (SiO2, 99.9%), Alumina powders (Al2O3, 99.9%), and silica sol, supported by the Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory.

Preparation of S-boride′ ceramic composites

S-boride′ ceramic composites were prepared by a precursor conversion method. First, the boride nano-powders (ZrB2′, TiB2′, NbB2′, HfB2′, TaB2′) with different weight ratios of 40 wt. %, 50 wt. % and 60 wt. % were dispersed evenly into the liquid polysiloxanes. Subsequently, the polysiloxanes precursor initiated addition reactions under the catalysis of dicumyl peroxide (DCP) at 160 °C for 2 h under an air atmosphere to form a 3D polymer network. After that, the cross-linked products were mixed with ethanol and ball-milled to powders. The as-prepared powders were then dried in an oven and cold-pressed into coaxial rings (Фin = 3 mm, Фout = 12 mm) under a pressure of 5 KN. After pressing, the samples were pyrolyzed at 1000 °C for 2 h in Ar atmosphere to obtain S-boride ceramic composites.

Preparation of S-MB ceramic composites

S-MB ceramic composites (S-MB-40, S-MB-50, S-MB-60, and S-MB-A) were fabricated by a precursor conversion method. Firstly, various boride powders were mixed according to the calculated ratios and uniformly distributed in liquid polysiloxanes. Subsequently, the SiOC precursor was cross-linked at 160 °C for 2 h in an air atmosphere to construct the 3D polymeric network containing MB absorbers. After that, the product was ball-milled and sieved through a 200-mesh screen. Then, the as-prepared powders were pressed into ring-shaped samples (Фin = 3 mm, Фout = 12 mm) under a pressure of 5 KN. Finally, the samples were subjected to a heat treatment at 1000 °C for 2 h in an Ar atmosphere to obtain S-MB ceramic composites.

Preparation of the S-MB-A plate

The mixed powders were cold-pressed into a metal mold at 5 KN, followed by demolding. The resulting plate was pyrolyzed at 1000 °C for 2 h under an Ar atmosphere and the S-MB-A plate was obtained.

Characterization

The phase composition of all samples was characterized by XRD (X’Pert Pro, Philips, Netherlands). SEM (FEI, NANOSEM450, USA), EDS, and TEM (FEI, Talos F200X, USA) were employed to analyze the microstructure and morphology. Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) was employed to characterize the WF of SiOC and borides. Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-vis) was used to characterize the band gap of SiOC and borides. Direct current (DC) conductivity (σ) was measured by Source Meter instrument (Keithley 6514). The sample surface was coated with a carbon point and connected to the Source Meter instrument using Pt wires to obtain the resistance. A vector network analyzer (VNA, MS4644A; Anritsu, Japan) was employed to record the electromagnetic parameters (complex permittivity (εr = ε′-jε″) through the typical coaxial-line method in the frequency range from 2 to 18 GHz. Before detection, all samples are machined into standardized specimens (Фin = 3.04 mm, Фout = 7 mm). Additionally, the Vector network analyzer (VNA, N5225B; Germany) was used to record the room temperature RL values and high-temperature RL values through the arch-testing method at the frequency range from 2-40 GHz and 2-18 GHz, respectively. A robotic arm was used to manipulate the high-temperature furnace chamber above the sample surface for heating. The sample was held for 10 min at temperatures consistently 50 °C above each target test temperature to compensate for surface cooling during furnace retraction. The sample temperature was monitored in real-time using a thermocouple contacting the sample directly through a central aperture in the stage. RL values were measured at 473 K, 673 K, 873 K, 1073 K, 1273 K, and 1473 K. The full measurement procedure is schematically shown in Supplementary Fig. 36. At last, the EM parameters in X and Ku bands were measured by the waveguide method. The data were collected when the waveguide cavity was heated to 873 K and 1473 K.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are presented in the paper or the Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Fan, R. H. et al. Constructing metastructures with broadband electromagnetic functionality. Adv. Mater. 32, 1904646 (2019).

Akinwande, D. et al. Two-dimensional flexible nanoelectronics. Nat. Commun. 5, 5678 (2014).

Zeng, X. J. et al. Constructing built-in electric fields with semiconductor junctions and schottky junctions based on mo–Mo–MXene/Mo––metal sulfides for electromagnetic response. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 213 (2024).

Wen, B. et al. Reduced graphene oxides: light-weight and high-efficiency electromagnetic interference shielding at elevated temperatures. Adv. Mater. 24, 3484–3489 (2014).

Zhou, W. et al. High-temperature electromagnetic wave absorption properties of Cf/SiCNFs/Si3N4 composites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 103, 6822–6832 (2020).

Lan, X. L. et al. Efficient high-temperature electromagnetic wave absorption enabled by structuring binary porous SiC with multiple interfaces. Carbon 170, 517–526 (2020).

Cai, Z. X. et al. Alternating multilayered Si3N4/SiC aerogels for broadband and high-temperature electromagnetic wave absorption up to 1000 °C. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 16704–16712 (2021).

Jiao, Z. B. et al. Achieving ultra-wideband and elevated temperature electromagnetic wave absorption via constructing lightweight porous rigid structure. Nano Micro Lett. 14, 173 (2022).

Quan, B. et al. Dielectric polarization in electromagnetic wave absorption: review and perspective. J. Alloy. Compd. 728, 1065–1075 (2017).

Fu, Y. R. et al. Manipulating polarization attenuation in NbS2-NiS2 nanoflowers through homogeneous heterophase interface engineering toward microwave absorption with shifted frequency bands. Nano. Mater. Sci. 6, 794–804 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Achieving superior electromagnetic wave absorbers with 2D/3 Dheterogeneous structures through the confinement effect of reduced graphene oxides. Carbon 213, 118245 (2023).

Huang, Z. H. et al. High-performance microwave absorption enabled by Co3O4 modified VB-group laminated VS2 with frequency modulation from S-band to Ku-band. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 30, 155–164 (2022).

Cheng, J. Y. et al. Construction of multiple interfaces and dielectric/magnetic heterostructures in electromagnetic wave absorbers with enhanced absorption performance: a review. J. Materiomics. 7, 1233–1263 (2021).

Liang, L. L. et al. Heterointerface engineering in electromagnetic absorbers: new insights and opportunities. Adv. Mater. 34, 2106195 (2022).

Liu, T. et al. Boosting multiple loss by hierarchical nano-architecture with manipulation of interfacial charge redistribution in Mott–Schottky heterostructures for enhanced electromagnetic absorption. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 223, 66–75 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Hydrangea-like N-doped Carbon/MoO2@ SnS2 microspheres with Schottky contact: a multi-interface heterostructure for high-performance microwave absorption. Compos. B. Eng. 263, 110858 (2023).

Zhang, X. F. et al. Gigahertz dielectric polarization of substitutional single niobium atoms in defective graphitic layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 147601 (2015).

Wyatt, B. C. et al. Ultra-high temperature ceramics for extreme environments. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 773–789 (2024).

Chen, Y. K. et al. Multiple schottky contacts motivated via defects to tune the response ability of electromagnetic waves. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2417215 (2025).

Liu, X. et al. Multicomponent competitive synergistically active NiFe2O4/Cg-C3N4/RGO heterostructure for efficient electromagnetic wave absorption. Carbon 234, 119964 (2025).

Mu, Y. et al. Mechanical and dielectric properties of 2.5 D SiCf/SiC–Al2O3 composites prepared via precursor infiltration and pyrolysis. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 596, 64–70 (2014).

Jia, Y. J. et al. Wide-band tunable microwave-absorbing ceramic composites made of polymer-derived SiOC ceramic and in situ partially surface-oxidized ultra-high-temperature ceramics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 45862–45874 (2019).

Zhang, K. et al. All-dielectric ultra-broadband microwave absorbing aerogel with optimized dielectric dispersion via dielectric relaxation time regulation. Adv. Mater. 37, 2506386 (2025).

Liang, L. Y. et al. Multifunctional magnetic Ti3C2Tx MXene/graphene aerogel with superior electromagnetic wave absorption performance. ACS nano 15, 6622–6632 (2021).

Ren, B. et al. Electromagnetic wave absorbing ceramics composites made of polymer-derived SiC with BN@ CNTs pyrolyzed higher than 1200. C. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 167, 213–227 (2023).

Wang, J. H. et al. MXene-Based ultrathin electromagnetic wave absorber with hydrophobicity, anticorrosion, and quantitively classified electrical losses by intercalation growth nucleation engineering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2402419 (2024).

Samet, M. et al. Polymer bilayers with enhanced dielectric permittivity and low dielectric losses by Maxwell–Wagner–Sillars interfacial polarization: characteristic frequencies and scaling laws. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 136, 47551 (2019).

Jia, Y. J. et al. Ultrahigh-temperature ceramic–polymer-derived SiOC ceramic composites for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 46254–46266 (2020).

Gao, Z. G. et al. Electromagnetic absorbers with Schottky contacts derived from interfacial ligand exchanging metal-organic frameworks. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 600, 288–298 (2021).

Gbadamasi, S. et al. Interface chemistry of two-dimensional heterostructures–fundamentals to applications[J]. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 4684–4729 (2021).

Shao, G. S. Work function and electron affinity of semiconductors: Doping effect and complication due to fermi level pinning. Energy Environ. Mater. 4, 273–276 (2021).

Li, X. H. et al. Metal nanoparticles at mesoporous N-doped carbons and carbon nitrides: functional Mott–Schottky heterojunctions for catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 6593–6604 (2013).

Ding, J. W. et al. Defect engineering activates Schottky heterointerfaces of graphene/CoSe2 composites with ultrathin and lightweight design strategies to boost electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2305463 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Built-in electric field enhancement strategy induced by cross-dimensional nano-heterointerface design for electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2407217 (2025).

Zhu, H. B. et al. Harmonization of heterointerface states to enhance built-in electric field effects for electromagnetic wave absorption. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 229, 223–234 (2025).

Qin, M. et al. Dielectric loss mechanism in electromagnetic wave absorbing materials. Adv. Sci. 9, 2105553 (2022).

Gao, Z. G. et al. Tailoring built-in electric field in a self-assembled zeolitic imidazolate framework/MXene nanocomposites for microwave absorption. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311411 (2024).

Zhao, X. et al. Designing a built-in electric field for efficient energy electrocatalysis. ACS Nano 16, 19959–19979 (2022).

Yin, X. X. et al. Electromagnetic properties of Si–C–N based ceramics and composites. Int. Mater. Rev. 59, 326–355 (2014).

Tang, Z. T. et al. Synthesis of CuCo2S4@Expanded Graphite with crystal/amorphous heterointerface and defects for electromagnetic wave absorption. Nat. Commun. 14, 5951 (2023).

Liu, J. L. et al. Boosted electromagnetic wave absorption performance from vacancies, defects and interfaces engineering in Co(OH)F/Zn0.76Co0.24S/Co3S4 composite. Chem. Eng. J. 411, 128601 (2021).

Lv, H. L. et al. Electromagnetic absorption materials: Current progress and new frontiers. Prog. Mater. Sci. 127, 100946 (2022).

Luo, J. H. et al. Carbon nanotubes decorated FeNi/nitrogen-doped carbon composites for lightweight and broadband electromagnetic wave absorption. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 158, 207–217 (2023).

Qu, N. et al. 2D/2D coupled MOF/Fe composite metamaterials enable robust ultra–broadband microwave absorption. Nat. Commun. 15, 5642 (2024).

Ren, B. et al. Achieving broadband electromagnetic absorption at a wide temperature range up to 1273 K by metamaterial design on polymer-derived SiC-BN@ CNT ceramic composites. Chem. Eng. J. 478, 147251 (2023).

Jia, Y. J. et al. Electromagnetic wave absorption of polymer derived ceramic composites tuned by multi-component oxide solid solution. Compos. B. Eng. 278, 111431 (2024).

Cao, W. Q. et al. Temperature dependent microwave absorption of ultrathin graphene composites. J. Mater. Chem. C. 3, 10017–10022 (2015).

Luo, C. J. et al. Excellent electromagnetic wave absorption of iron-containing SiBCN ceramics at 1158 K high-temperature. Adv. Eng. Mater. 20, 1701168 (2018).

Wei, H. J. et al. Construction of Si3N4/SiO2/SiC–Y2Si2O7 composite ceramics with gradual impedance matching structure for high-temperature electromagnetic wave absorption. Ceram. Int. 48, 23172–23181 (2022).

Song, Y. et al. SiBNCx ceramics derived from single source polymeric precursor with controllable carbon structures for highly efficient electromagnetic wave absorption at high temperature. Carbon 188, 12–24 (2022).

Lv, X. Y. et al. 3D printing “wire-on-sphere” hierarchical SiC nanowires/SiC whiskers foam for efficient high-temperature electromagnetic wave absorption. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 109, 94–104 (2022).

Mu, Y. et al. Temperature-dependent dielectric and microwave absorption properties of SiCf/SiC–Al2O3 composites modified by thermal cross-linking procedure. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 35, 2991–3003 (2015).

Luo, C. J. et al. Excellent electromagnetic wave absorption of MOF/SiBCN nanomaterials at high temperature. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 34, 277–291 (2021).

Lan, X. L. et al. High-temperature electromagnetic wave absorption, mechanical and thermal insulation properties of in-situ grown SiC on porous SiC skeleton. Chem. Eng. J. 397, 125250 (2020).

Luo, C. J. et al. Graphene shield by SiBCN ceramic: a promising high-temperature electromagnetic wave-absorbing material with oxidation resistance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 39307–39318 (2018).

Jin, Z. Q. et al. Lightweight and thermally insulating ZnO/SiCnw aerogel: a promising high temperature electromagnetic wave absorbing material with oxidation resistance. Chem. Eng. J. 498, 155110 (2024).

Xue, J. M. et al. A novel oxide ceramic matrix composite with integrated high-temperature EMW absorption and mechanical performance. J. Alloy. Compd. 1004, 175882 (2024).

Shao, T. Q. et al. High temperature absorbing coatings with excellent performance combined Al2O3 and TiC material. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 40, 2013–2019 (2020).

Yang, F. et al. In-situ construction of carbon fiber gradient periodic structure in Al2O3f/SiOC composites for ultra-broadband and high-temperature electromagnetic wave absorption. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 194, 87–97 (2024).

Lu, M. M. et al. Multi-wall carbon nanotubes decorated with ZnO nanocrystals: mild solution-process synthesis and highly efficient microwave absorption properties at elevated temperature. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2, 10540–10547 (2014).

Yin, X. W. et al. Dielectric, electromagnetic absorption and interference shielding properties of porous yttria-stabilized zirconia/silicon carbide composites. Ceram. Int. 38, 2421–2427 (2012).

Ma, J. R. et al. A green fabrication and variable temperature electromagnetic properties for thermal stable microwave absorption towards flower-like Co3O4@ rGO/SiO2 composites. Compos. B. Eng. 166, 187–195 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Electromagnetic property and tunable microwave absorption of 3D nets from nickel chains at elevated temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 22615–22622 (2016).

Gao, H. et al. Temperature-dependent dielectric and microwave absorption properties of silicon carbide fiber-reinforced oxide matrices composite. J. Mater. Sci. 53, 15465–15473 (2018).

Li, M. et al. High-temperature dielectric and microwave absorption properties of Si3N4–SiC/SiO2 composite ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. 50, 1478–1487 (2015).

Han, T. et al. Effect of SiC nanowires on the high-temperature microwave absorption properties of SiCf/SiC composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 39, 1743–1756 (2019).

Chen, D. et al. Effect of temperature on microwave-absorption property of plasma-sprayed Ti3SiC2/NASICON coating. J. Electron. Mater. 48, 1506–1510 (2019).

Yang, H. Y. et al. Enhanced dielectric properties and excellent microwave absorption of SiC powders driven with NiO nanorings. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2, 214–219 (2014).

Hou, Z. X. et al. Reduced graphene oxide/silicon nitride composite for cooperative electromagnetic absorption in wide temperature spectrum with excellent thermal stability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 5364–5372 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52232005 to J.Y.J., 52172104 to J.Y.J., and 52293370 to L.H.J.), Aeronautical Science Foundation of China (ASFC, Grant Nos. 2023Z073053010) to J.Y.J., Northwestern Polytechnical University Doctoral Dissertation Innovation Fund (CX2025005) to R.B.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bin Ren: Investigation and methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Formal analysis. Yujun Jia: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—Review and Editing. Lehua Qi: Funding acquisition. Yixiang Ling: Software, Data curation. Hang Yu: Software, Data curation. Junjie Cheng: Formal analysis, Data curation. Mengyu Dai: Investigation, Data curation. Hejun Li: Project administration, Funding acquisition. Qiangang Fu: Supervision. Yulei Zhang: Supervision. Xianghui Hou: Writing—Review & Editing. Qiang Song: Writing—Review and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yongzhao Hou, Zhaohui Yang, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, B., Jia, Y., Qi, L. et al. Broadband electromagnetic absorption up to 1473 K enabled by dielectric frequency-dispersion engineering in ceramic composites. Nat Commun 17, 318 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67003-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67003-0