Abstract

Anthropogenic-driven climate change is accelerating permafrost thaw, threatening to release vast carbon stores through increased microbial activity. While microbial roles are increasingly studied, the contributions of viruses remain largely unexplored, in part due to soil-associated technical challenges that have hindered their detection and characterization. Here, we applied an optimized virion enrichment workflow along a permafrost thaw gradient, identifying 9,963 viral populations (vOTUs), including single- and double-stranded DNA viruses, with 99.9% novelty compared to other soils. Hosts were predicted for 38% of vOTUs, spanning nine archaeal, and 36 bacterial phyla, 22% of which were linked to metagenome-assembled genomes, including key carbon-cycling taxa. Genomic analyses revealed 811 putative auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) from 658 vOTUs, nearly half involved in carbon processing. These included 59 glycoside hydrolases (GH) across nine GH families, 45 for monosaccharide degradation, and seven involved in short-chain fatty acid and C1 metabolism, linking viruses to both early and late stages of carbon turnover. Additionally, six vOTUs carried racD, which may stabilize microbial necromass and promote long-term carbon storage. Viral and AMG functional diversity increased with thaw stage, indicating that viruses might participate in a broadening range of microbial metabolic processes as permafrost thaws. These findings expand our understanding of virus contributions in microbial carbon processing and suggest their important role in deciphering soil carbon fate under changing climate conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil provides a foundation for a wide range of life on Earth, serves as both a source and a sink of greenhouse gases, and has a key role in the exchange of energy on Earth. Soils and their associated organism and virus biodiversity are vulnerable to climate change, especially at northern latitudes where upwards of 50% of global soil carbon is stored in permafrost, i.e., soil that remains frozen for at least two consecutive years1,2, making it the largest terrestrial carbon stock. Permafrost is thawing at a global rate of ~1 cm depth/year3, exposing this large carbon reservoir to microbial degradation. While the fate of this carbon remains unknown, a synthesis of previous warming experiments saw considerable carbon loss from northern latitude soils4, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has highlighted the fate of this carbon as an important knowledge gap limiting climate change model predictions5.

Microbes are key drivers in the fate of thawing and thawed permafrost carbon. Microbes degrade complex macromolecules into more labile monomers that either feed carbon metabolisms, such as fermentation, respiration, and methanogenesis, thereby causing gaseous carbon loss from the system, or sorb to the soil matrix6,7. As a result, numerous studies seek to understand microbiomes in permafrost ecosystems—largely via culture-independent techniques like paired bulk metagenomes and metatranscriptomes, which has led to a better mechanistic understanding of microbial ecophysiology in these habitats6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. A synthesis of these data highlights soil moisture content, redox chemistry, sunlight, temperature, and overlying vegetation as key drivers of the microbial response to permafrost thaw. Notably, in at least one case, the abundance of a single microbe could predict ecosystem carbon fluxes better than any other variable measured15, which emphasizes the value of illuminating the “microbial black box” for understanding ecosystem functioning. Evidence of the system-level magnitude of microbial impacts is accumulating, and while we currently are unable to fully predict post-thaw microbial assembly patterns, viruses will undoubtedly play a role.

Viruses are an essential part of soil microbiomes and may be critical for understanding the fate of soil organic carbon16. In marine ecosystems, viruses are responsible for lysing approximately one-third of microbes each day, releasing carbon and nutrients on a global scale17,18,19,20. In addition to cell lysis, viruses influence carbon cycling by metabolically rewiring their hosts, which can result in completely different ecosystem outputs for virus-infected cells as compared to their uninfected counterparts21,22,23,24. The metabolic rewiring may include the expression of virus-carried auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) that specifically augment host metabolism towards a larger ecosystem impact25. However, translating the roles of marine viruses to soil viruses is difficult, partially due to the extensive microbial richness in soils that obscures the detection of virus genomes26,27. In previous efforts to mine the virus signal in bulk metagenome soil samples, less than 2% of assembled reads originated from detected viruses28,29,30. Recent studies have reduced microbial richness by targeting specific microbes with isotopically labeled substrates, allowing increased understanding of virus effects on microbe ecophysiology31,32,33,34,35), but resolution on virus genomes (i.e., the richness of virus genomes detected and the number of reads that map to them) in soils remains low.

Virus-targeted metagenomic surveys (better known as viromes) physically separate virus-like particles (VLPs) from the soil matrix with chemical and physical methods, followed by size filtration, VLP concentration and purification, and then DNA extraction36. These additional steps provide increased resolution on viruses by targeting the estimated 107–1010 VLPs per gram of soil37,38 and removing larger organisms that recruit sequencing data29. Therefore, viromes capture a higher per-sample vOTU recovery compared to bulk metagenomes39,40, allowing for a more comprehensive view of DNA soil viral diversity and in-depth analyses into their evolution and ecology.

Hints of viral roles are starting to emerge, particularly in the natural thawing permafrost gradient of the long-term field site of Stordalen Mire, northern Sweden41. At this site, microbial community structure and metabolisms (encoded and expressed) dramatically shift with permafrost thaw7,10, as do viruses recovered from a survey of 178 bulk soil metagenomes30, 379 bulk soil metagenomes42, 12 size-fractioned metagenomes30, 55 bulk soil metatranscriptomes43 and 13 viromes29,44. These viral communities are highly diverse, endemic to their habitat, are predicted to infect key carbon cycling microbes, and carry glycoside hydrolases, considered AMGs, capable of influencing host carbon cycling. Notably, six of the viromes captured single-stranded (ss)DNA viruses in addition to double-stranded (ds)DNA viruses, and while ssDNA viral ecology was not assessed, the ssDNA viruses recruited a very small proportion of the viromic reads44. Despite the advances in soil viromics, there are still very few soil viromes from permafrost habitats, and a knowledge gap remains in understanding the breadth of carbon metabolism that viruses modulate and how it changes with permafrost thaw.

Here, we applied previously optimized sampling to purify virus particles from 20 samples across multiple depths along the Stordalen Mire permafrost thaw gradient over two consecutive years. We compared two existing library preparation techniques, capturing both ssDNA and dsDNA viruses, used optimized bioinformatics methods to detect and characterize virus populations, connect the virus populations to putative microbial hosts, and characterize virus-microbe interactions, to provide a baseline understanding of virus diversity and ecosystem impacts. The combination of a larger virome dataset and our optimized sample-to-ecology pipeline led to a tenfold improvement of vOTU recovery (~30 vOTUs/Gb of virome versus ~3 vOTUs/Gb of virome) compared to our previous method29.

Results and discussion

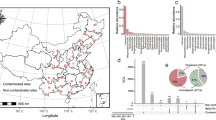

Stordalen Mire in northern Sweden is a peatland underlain by permafrost that is experiencing climate change more rapidly than many other ecosystems. Its natural thaw gradient makes it an ideal system for investigating how climate change alters ecosystem structure and function, and long-term ecological monitoring and integrative projects such as IsoGenie and EMERGE have established a strong foundation of microbial and biogeochemical data to contextualize viral dynamics41. We expanded these sampling efforts by collecting 20 peatland samples spanning three stages of permafrost thaw (palsa—intact permafrost, bog—partially thawed permafrost, and fen – fully thawed permafrost) across two years and multiple depths for viromic analyses (Fig. 1). To maximize viral particle recovery, we used protocols optimized for their resuspension45 and DNA extraction44 specifically for these soils. We then sought to maximize virus sequences captured by applying two quantitative library approaches that had been previously optimized for dsDNA viruses44,46,47,48,49 or both ssDNA and dsDNA viruses44,50. The 40 resulting libraries were then sequenced to create viromes to quantitatively capture ssDNA and dsDNA viruses as a foundation to study their ecology in the Mire.

The study site Stordalen Mire (red dot, upper left panel) lies above the Arctic Circle in northern Sweden, and spans three natural permafrost thaw stages (palsa, bog, and fen, with images of representative cores shown below; representative photos of cores were taken by Gareth Trubl). Soil cores were collected in July 2016 and 2017, with two depths subsampled for viruses in the 2016 cores and four subsampled in the 2017 cores, for a total of 20 samples for viromes. To achieve the study goals (indicated in green font), best practices in virome recovery, sequencing, and analysis were applied as shown. Illustrations were created or edited by Ryan Goldsberry.

Comparing viral signal recovery from different library methods

To access viral diversity, two quantitatively proven library methods were used: (1) the Nextera XT kit (here forth Nextera), which amplifies dsDNA51, and (2) the Accel-NGS 1S plus kit (here forth Accel), which amplifies both ssDNA and dsDNA44,50. We previously developed a pipeline using this dataset, combining read deduplication and an assembly algorithm that improved assembly of contigs ≥10 kb and increased recovery of vOTUs by 2-fold for low-input metagenomes52. Applied to the 40 viromes generated here, this pipeline yielded 24,541 dsDNA viral contigs ≥10 kb with the Nextera library method, 24,829 dsDNA viral contigs ≥10 kb and 5887 ssDNA viral contigs ≥500 bases with the Accel library method. Overall, 20,073 dsDNA viral contigs were identified in both datasets. We previously noted that these PCR-amplified metagenomes were quantitative when compared to unamplified libraries and reported coverage bias along individual genomes52. Here, we leveraged the larger dataset of paired soil viromes to characterize these two library preparation methods in terms of viral contig recovery and potential coverage biases. The number of viral contigs recovered for each sample was consistent (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Comparing the number of reads that map to contigs detected in both kits for each metagenome, revealed the Accel kit performed significantly better at the relaxed threshold (Supplementary Fig. 1B; ANOVA p < 0.01) and the kits performed similarly at the strict threshold (Supplementary Fig. C; ANOVA p > 0.05). To assess whether inter-kit variation exceeded variation within each kit, we conducted a non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis of Bray-Curtis dissimilarities. At both the 10 and 75% coverage thresholds, viromes clustered primarily by sample rather than library kit, with substantial overlap between methods (Supplementary Fig. 1D/E). The NMDS ordination had very low stress values, indicating an excellent fit to the data. This was supported by non-significant PERMANOVA results (p > 0.05) and near-zero ANOSIM R statistics, indicating that differences between library kits were not greater than variability within each kit. Contig coverage biases, specifically unmapped reads, are a common problem with tagmentation-based approaches (i.e., all Nextera amplified genomes49,53,54,55,56,57. This problem is often amplified in soils due to co-extracted polysaccharides, which are known inhibitors of DNA quantification and enzymatic reactions such as tagmentation, which can cause under- or over-tagmentation. Illumina launched a new version of Nextera called “DNA Prep kit” to address issues associated with DNA input by using bead-based technology to accommodate a wide range of DNA amounts, removing the need for DNA quantitation, and reducing under- and over-tagmentation58. Future studies are needed to assess varying quantities and compositions of polysaccharides co-eluting with DNA to determine specific associated biases that may still exist.

Characterization and ecology of viral populations

To explore the ecology of these viruses at the population level, we combined the libraries to create a nonredundant list of viral populations (vOTUs) as reference genomes for further analyses. This resulted in 9233 dsDNA vOTUs (3% unique to Nextera and 9% unique to Accel) and 730 ssDNA vOTUs (unique to Accel due to the library preparation selection step), resulting in 9963 total ssDNA and dsDNA vOTUs spanning the permafrost thaw gradient. Accumulation curves showed that vOTU richness increased with sample size before plateauing, indicating sufficient sampling depth to explore ecological patterns (Fig. 2A). Early accumulation slopes were also steeper in Bog and Fen, suggesting faster diversity accrual compared to Palsa. These results highlight clear differences in viral diversity and community structure among habitats. We next assessed the quality of the vOTUs, starting with the dsDNA vOTUs using CheckV, a bioinformatics tool that assesses the quality and completeness of metagenome-assembled viral genomes. CheckV identified 24 complete genomes, 552 high quality, 950 medium quality, 6019 low quality, and 1688 quality-not-determined dsDNA viral genomes (Supplementary Data 1). CheckV performs best where closely related reference genomes are available and soil virus reference genomes are not widely available, therefore, we interpret the large number of “not-determined” and ‘low quality’ dsDNA vOTU genomes to represent an unknown mix of challenging genomes for CheckV and highly fragmented genomes from low coverage (both the number of reads that map to contigs and the portion of the contig length covered) soil viromes. For ssDNA vOTUs, we manually inspected circularity via terminal redundancy (see Methods), identifying 676 complete genomes. The remainder were evaluated using CheckV, which categorized three as complete, seven as high quality, six as medium quality, 23 as low quality, and 15 as quality-not-determined.

A Accumulation curves of cumulative vOTU richness as sampling effort increased. The gray boxplots represent the average of all the virome data (n = 20) and reflect the rate of new vOTUs under continuous sampling (100 permutations). The overlaid lines display the mean cumulative richness per habitat: palsa n = 5, bog n = 7, and fen n = 8. B A principal coordinates of analysis plot of the twenty viromes samples. Palsa samples are brown, bog samples are green, and fen samples are blue, and 95% confidence intervals are colored coded by habitat. C A heatmap showing the normalized coverage (log 10 transformed) of the vOTUs among the three habitats, clustered using a Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metric. D Boxplots showing macro- and microdiversity metrics of the vOTUs for each habitat based on vOTU normalized abundance.

With these 9963 ssDNA and dsDNA reference genomes in hand, we next evaluated their ecological patterns across the permafrost thaw gradient. Beta diversity analyses revealed strong habitat-specific viral community structure. Principal coordinates analysis of Bray-Curtis dissimilarities showed distinct clustering of viral communities by habitat, with habitat type explaining a significant portion of the variation in community composition (R2 = 0.163, p < 0.05; Fig. 2B). Pairwise PERMANOVA comparisons indicated that palsa communities were significantly different from both bog and fen (adjusted p < 0.05), while bog and fen were not significantly different (adjusted p > 0.05). Homogeneity of group dispersions was confirmed (p > 0.05), supporting the robustness of these patterns. These results indicate that viral communities are structured primarily by habitat type, rather than depth or year. Building on these patterns, we next compared the viral relative abundance profiles by quantifying the number of reads mapping to vOTUs along the permafrost thaw gradient. Across the permafrost thaw gradient, 6,824 vOTUs (69%) were found to be unique to a single habitat, with the highest number in bog (2413), followed by fen (2272), and palsa (2139; Fig. 2C). An additional 2936 vOTUs (30%) were shared between exactly two habitats, with the greatest overlap observed between bog and fen (2394), and fewer shared between palsa and bog (343), and palsa and fen (199). Only 203 vOTUs (2%) were detected across all three habitats. This result mirrors our previous viromics analysis of these habitats in which bog had the most unique vOTUs, followed by fen and then palsa29 and aligns with a recent 13-year long-term metagenomic analyses from the same site, which found that 82% of vOTUs were habitat-specific, and just ~1% occurred in all habitats—primarily abundant vOTUs in bog and fen—highlighting the strong habitat-specific structuring of viral communities42. When comparing relative abundance, bog had the highest total viral abundance, followed closely by fen, while palsa had considerably lower abundance (Fig. 2C). Spearman correlations between habitats showed weak to moderate negative relationships between palsa and the other two habitats (palsa–bog: ρ = −0.37; palsa–fen: ρ = −0.41), and minimal correlation between bog and fen (ρ = 0.03), indicating distinct viral community structures and abundances across the thaw gradient.

Previous work from Stordalen Mire also showed that viral community composition was significantly correlated with peat depth30, with the greatest viral abundance in the fen habitat (paralleling microbial abundances), but the highest viral richness in the bog (unlike the microbes, which are richest in the fen), and a clear pattern of habitat-specific viruses29,30,42. In our dataset we saw similar trends with viral richness highest in the bog (Fig. 2D), however, these differences were not statistically significant (Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s post hoc test, p > 0.05). Evenness also did not differ significantly across habitats or depths. Both vOTU richness and read recruitment were generally greater in the surface and middle depths across all habitats—except for the palsa surface samples—though again, differences were not significant (Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s post hoc test, p > 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 2A). The lack of significant differences likely reflects both the high spatial heterogeneity of soil viruses35,59 and the limited spatial and temporal breadth of our dataset. Despite this, habitat type was a larger driving factor of viral community composition than depth or year (Supplementary Fig. 2B). We hypothesize that the increased viral richness in the upper depths was likely due to bacterial and archaeal richness also being highest at those depths7. Finally, we assessed viral population microdiversity to explore potential selection and divergence across habitats. Nucleotide diversity (Pi) and pN/pS ratios did not differ significantly between habitats (Kruskal–Wallis p > 0.05), likely reflecting the high spatial heterogeneity of soil viruses. Pairwise comparisons of FST revealed a borderline-significant difference between palsa and fen (Bonferroni-adjusted p = 0.049), indicating potential habitat-driven genetic differentiation. These results contrast with Sun et al42, who reported significant habitat-based viral selection patterns using metagenomes collected from 2010–2017. In contrast, our study focused on virions captured in viromes from 2016–2017, representing a narrower temporal window. Differences in sampling strategy and temporal scope likely contribute to the contrasting findings. Nonetheless, our macro- and microdiversity trends are consistent with long-term observations from the Mire, including higher viral richness and microdiversity in the bog and lower values in the palsa42. We proceeded to taxonomically classify the vOTUs using two approaches. First, the 9963 dsDNA vOTUs were compared to a set of virus reference genomes (viral refseq v.85) using a gene-sharing network as implemented in vConTACT2 (v. 0.9.1960). This tool clustered 5,261 of the 9,663 vOTUs into 1,488 genus-level viral clusters (VCs) and only 34 (~2.3%) of the VCs included a reference genome (Supplementary Data 2), highlighting the novelty of our dataset. The ssDNA viruses were detected and classified using marker genes (see Methods) and the phylum Cressdnaviricota accounted for the majority (574; 79%) of the ssDNA vOTUs detected, then 102 (14%) were in Phixviricota, 35 in Cossaviricota and 19 in Hofneiviricota (Fig. 3A). A taxonomic breakdown of ssDNA vOTUs at the family level revealed that virtually all the viruses within the phylum Cressdnaviricota were unclassified cressdnaviruses (99%), with just a few viruses assigned to a known family: Circoviridae (n = 4), Draupniviridae (n = 23), Genomoviridae (n = 1), Geplanaviridae (n = 3), Kanorauviridae (n = 44), Mahapunaviridae (n = 4), and Naryaviridae (n = 1) (Fig. 3B). Overall, Cressdnaviricota accounted for about 50% of the total relative abundance of ssDNA vOTUs (Supplementary Data 3). All vOTUs within Phixviricota belonged to Microviridae, which comprised 31% of the ssDNA vOTU relative abundance (Fig. 3B). The Cossaviricota vOTUs grouped under the order Piccovirales, and ~31% of the vOTUs were classified as Parvoviridae, representing 18% of the total ssDNA vOTU abundance (Fig. 3B). Similarly, the Hofneiviricota vOTUs all belonged to the order Tubulavirales, and ~32% were assigned to Inoviridae (Fig. 3B), contributing ~1% of the relative abundance (Supplementary Data 3). These analyses underestimate the diversity of ssDNA viruses in these soils because it is based solely on the lineages of viruses captured with marker genes. Nevertheless, understanding the ecological role of ssDNA viruses in environmental samples is difficult due to detection methods typically using dsDNA virus features to detect viruses61 or the use of rolling-circle amplification, which precludes ecological interpretation50; therefore, marker genes detection on de novo-assembled contigs provides the best available strategy to investigate ssDNA viral ecology.

A A breakdown of ssDNA vOTUs at the phylum taxonomic level. B Family-level taxonomic resolution of vOTUs classified within Cressdnaviricota, Phixviricota, Cossaviricota, and Hofneiviricota. (C) Habitat-specific relative abundance of taxonomically classified ssDNA vOTUs across palsa, bog, and fen habitats. The number at the end of each bar represents the number of vOTUs detected.

The relative abundance of the ssDNA vOTUs, based on normalized read counts, was used to assess their distribution along the permafrost thaw gradient. The ssDNA vOTUs were most abundant in the fen samples accounting for 74% of the reads that mapped, followed by the bog (19%), and then palsa (7%) samples (Fig. 3C). Taxonomic comparisons showed that Cressdnaviricota were heavily enriched in the fen (74%), with lower representation in bog (19%) and palsa (7%). Similarly, Microviridae were most abundant in the palsa (44%), followed by fen (49%) and bog (6%). Tubulavirales and Piccovirales vOTUs showed increasing relative abundance with thaw, from palsa (9 and 2%) to bog (25 and 27%) to fen (66 and 71%), respectively. At the family level, Inoviridae and Parvoviridae were both strongly enriched in the fen (76 and 92%, respectively). These results are dramatically different compared to a previous characterization of ssDNA vOTUs from this field site44, where viruses in the family Microviridae were not detected in the palsa habitat, and the fen habitat had the lowest viral richness, highlighting the importance of higher-resolution spatiotemporal sampling to capture dynamic viral population shifts.

Global comparison of vOTUs

In recent years, large-scale virome datasets have accumulated for marine22, human gut62, and soil ecosystems; therefore, we compared these datasets, along with viral isolate genomes and previous soil virus datasets from Stordalen Mire, to assess the global distribution of our vOTUs (Supplementary Data 4). Not surprisingly, 97% of the vOTUs from the combined global dataset included exclusively environmental sequences (i.e., metagenomes and viromes) and not isolates, and a comparison of vOTUs derived from marine, human gut, and soil systems revealed very little overlap, with >99.8% of vOTUs identified as biome-specific, with only one vOTU shared across all three environments (Fig. 4A). This pattern confirms previous assessments of habitat or ecological zone specificity for viruses where vOTUs and viral communities are structured by environmental conditions22,29,30,40,63,64. Shifting from global to a soil-focused comparison, we next explored how these new viruses compared to previously collected viruses from Stordalen Mire and other soil environments. Analogously, most (~96%) of our vOTUs were novel. Of the 4% of vOTUs that were shared, nearly all (441 of 443) overlapped with previous Stordalen Mire datasets (SMV129,44, SMM30, and SMM242) and the two shared with other soils were found in another peatland site (SPRUCE40; Fig. 4B). Therefore, Stordalen Mire viruses were 99.9% unique compared to other soils. There were no vOTUs shared with agricultural soils (Ag39), biocrusts65, California wetlands soils (CA-WET66, California grassland soils (CA-Grass59; CA-Grass267), a mix set of California habitats (CA-MIX68), tropical rainforest soils (GRE69), or with permafrost-associated bog soils from Alaska (ICE-SIP33). Notably, however, ICE-SIP did have one vOTU shared with SMV1. Patterns of regional and habitat-based clustering emerged across the soil datasets. For example, the SPRUCE dataset shared 19 vOTUs with the previous Stordalen Mire vOTUs (SMM, SMM2, and SMV1), while the California datasets collectively shared 609 vOTUs (Ag; CA-Grass; CA-Grass2; CA-WET; CA-MIX). Altogether, there is high genetic novelty in each of the soil datasets, especially considering the small amount of shared vOTUs in our dataset compared to previous Stordalen Mire datasets. The minimal overlap in shared vOTUs among the Stordalen Mire datasets likely reflects differences in virome vs bulk metagenome sampling strategies29,39, as well as the pronounced spatial heterogeneity of soil viruses59,70.

A Comparison of unique and shared vOTUs among marine, human, soil, and RefSeq (v226) datasets and B a comparison only among soil datasets. The columns represent the percent of unique vOTUs (left side of each figure) or the number of shared vOTUs per dataset (right side of the figure), with a line below the column denoting the datasets being compared. The rows represent each dataset. Datasets are color-coded by source and gray for RefSeq. Datasets: GOV2 (marine; viromes22), GVD (human gut; metagenomes and viromes62), SMV2 (soil; viromes; this paper), SMV1 (soil; viromes29,44), SPRUCE (soil; viromes40), Ag (soil; viromes39), CA-WET (soil; viromes66), CA-MIX (soil; viromes68), CA-Grass (soil; viromes59), CA-Grass-2 (soil; viromes67), GRE (soil; stable isotope probing metagenomes69), Biocrust (soil; metagenomes65), SMM (soil; metagenomes, viromes removed30), SMM2 (soil; metagenomes42), ICE-SIP (soil; stable isotope probing metagenomes33).

Although there has been significant activity in identifying ssDNA viruses from environmental systems71,72,73,74,75,76, there is limited work on soils, which makes a global comparison challenging. We took advantage of the marker genes (MCP for microviruses and Rep for cressdnaviruses) of the 676 ssDNA vOTUs with complete genomes to further explore their genetic novelty by comparing them to ssDNA viruses from GenBank (Oct. 5, 2021) and the Les Pradeaux Mire (a sphagnum-dominated peatland in France)77,78. Only four microviruses from our dataset clustered with those identified in Les Pradeaux Mire (Supplementary Fig. 3)77 and 29 cressdnaviruses phylogenetically clustered with 15 (of the 34) Rep proteins from ssDNA viruses identified in Les Pradeaux Mire (Supplementary Fig. 4)78. The minimal overlap of ssDNA viruses from Stordalen Mire with another peatland indicates there is still a lot of novel ssDNA virus sequence space in soils, undoubtedly the result of high mutation rates of ssDNA viruses and that microviruses may be the most abundant ssDNA viruses on the planet79.

Inferring ecosystem impacts of soil viruses

We next sought to predict hosts for this study’s 9963 vOTUs to better understand their impacts on microbial biogeochemistry. We first used CRISPR spacers to match vOTUs to 1529 MAGs previously reconstructed from Stordalen Mire7. This resulted in the extraction of 3560 spacer sequences from CRISPRs identified in the 1529 MAGs, and there were 42 spacers matching our vOTUs, with 38 unique spacers (from 23 host CRISPRs) matching 13 unique dsDNA vOTUs to 24 unique MAGs (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 5). Despite the 4-to-6 years’ difference in sampling (2010–2012 for the MAGs, 2016–2017 for this study’s vOTUs), the number of CRISPR spacers from a host that matched a vOTU ranged from one to five spacers, demonstrating the utility of CRISPR spacers to link viruses and microbial hosts even when not sampled simultaneously. We detected 36 unique links between dsDNA vOTUs and MAGs from phyla Verrucomicrobiota and Acidobacteriota, with roughly three quarters to MAGs from Verrucomicrobiota subdivision 3 (26 of 36), one quarter to Acidobacteriotaceae MAGs (9 of 36), and 1 match to a Solibacterales MAG. Beyond CRISPR-based host predictions, we looked next at using nucleotide similarity matches to target potentially integrated viruses and identified 644 novel putative hosts for 488 vOTUs (i.e., there was no overlap between host linkage methods; Supplementary Data 5) and expanding the number of linked microbial hosts to 12 bacterial phyla and 1 archaeal phylum (Fig. 5). The most common phylum of bacteria predicted as host of at least one vOTU was Acidobacteriota, accounting for more than half of the total virus-host linkages (53%), followed by Actinobacteria (15%), Verrucomicrobiota (11%), and Patescibacteria (11%). Acidobacteriota is the most abundant phylum in the bog7 where viral richness and diversity were highest, and its dominance of virus-host linkages was seen in previous Stordalen Mire virus-host surveys29,30,42.

A proportional bar chart showing the top 25 microbial host phyla predicted from the Stordalen Mire MAGs via CRISPR spacers, sequence similarity (Blastn), and iPHoP137. Hosts were also predicted using iPHop with the GTDB database, with training on the Stordalen Mire MAGs. The total number of vOTUs with host linkages via all methods is also provided. The “other” category represents a summation of the remaining virus-host linkages (Supplementary Data 5). The number at the top of each bar represents the number of vOTUs with a predicted host.

Host prediction of viruses is an arduous process, with our effort only linking ~1.3% of our vOTUs to MAGs, and to be able to maximize the number of putative hosts for our vOTUs, we next compared our vOTUs to the GTDB database (release 202) using the iPHoP bioinformatic tool trained on the 1529 MAGs from Stordalen Mire (see Methods). We predicted hosts for 3,806 vOTUs (38%) spanning bacteria (91.5%) and archaea (8.5%), and 41 phyla (Fig. 5). Over half (54%) of the MAGs had at least one predicted associated vOTU, and 1067 vOTUs had an iPHoP score ≥90, allowing genus-level taxonomic resolution for the predicted host (Supplementary Data 5). Most vOTUs with predicted hosts originated from the bog (41%), followed by the fen (34%) and palsa (25%), with detection declining by depth (surface: 40%; middle: 32%; deep: 17%; extra-deep: 11%). Altogether, this global prediction effort increased our host predictions by almost ninefold. Among the predicted interactions, 124 vOTUs were linked to methanogens across three archaeal phyla (Halobacteriota, Methanobacteriota, Thermoplasmatota), including 13 acetoclastic, 103 hydrogenotrophic, and 3 methylotrophic methanogens, with 75 of these vOTUs linked to 23 previously identified methanogenic MAGs7 (Supplementary Data 5). Additionally, 243 vOTUs were linked to 16 methanotrophs (ten aerobic and six anaerobic), and 231 vOTUs to non-methanogenic methylotrophs from one archaeal and four bacterial phyla, with 15 vOTUs connected to 16 previously identified methanotrophic MAGs11.

Compared to prior surveys at this site, our results represent an approximately six fold increase in methanogen-associated viruses and a ~12-fold increase in methanotroph-associated viruses. Previous studies detected 67 methanogen-associated viruses (6 acetoclastic, 61 hydrogenotrophic) and 13 methanotroph viruses42, while earlier work identified 15 methanogen and 13 methanotroph viruses30. Our expanded detection includes viruses linked to methylotrophic methanogens and a wide range of bacterial methylotrophs, aligning with recent findings that methylotrophy is a more widespread and active component of carbon cycling in the Mire than previously recognized80. Moreover, our identification of viruses infecting methanotrophs adds a new dimension to microbial controls over methane fluxes, building on previous work that highlighted the shifting abundance, composition, and activity of methanotrophic communities along the Mire’s thaw gradient11. Together, these findings point to a complex and virus-influenced microbial network contributing to methane production, oxidation, and emissions in thawing permafrost wetlands.

Current host prediction tools for viruses were developed using dsDNA viruses. To predict hosts for ssDNA viruses, we inferred hosts based on the taxonomic affiliation for the six Inoviridae and the 11 Parvoviridae vOTUs, and for the 676 complete ssDNA vOTUs, we predicted hosts based on similar nucleotide content to known ssDNA virus hosts. Inoviridae are non-enveloped filamentous bacteriophages that mostly infect Gram-negative bacteria81, but Parvoviridae are non-enveloped viruses and can infect vertebrates or invertebrates depending on their subfamily taxonomy82. Based on our phylogenetic comparison of microviruses with those identified in another peatland, Les Pradeaux Mire (Supplementary Fig. 3)77, we infer four microviruses vOTUs to infect bacteria from the phylum Bacteroidota. Microviridae is a family of ssDNA bacteriophage with a wide host range that mainly infects Bacteroidota (Gram-negative bacteria), Enterobacteriaceae (Gram-negative bacteria), Spiroplasma (parasitic bacteria without a cell wall), and Rhizobiaceae (Gram-negative nitrogen-fixing bacteria that have a symbiotic relationship with plants and often dominate Sphagnum peatlands), and to a lesser extent other Gram-negative bacteria79,83,84,85. This suggests that although microviruses may not carry AMGs nor participate in horizontal gene transfer79, they may still have appreciable impacts on the soil ecosystems. Particularly in fen ecosystems, their putative host, Bacteriodota, are the primary lactate metabolizers in the fen7 and have the capability to degrade a wide range of complex carbohydrates via their polysaccharide utilization loci86.

Cressdnaviruses are known to infect a wide array of eukaryotes87 and twelve of the cressdnavirus vOTUs have identifiable ORFs that are Rep proteins when using a ciliate translation table, which we interpret to suggest that they infect ciliates or another group of protists here too. Ciliates are bacterivorous protozoan that are commonly found in the active layer of permafrost soils, and along with other protozoa play an important role in controlling bacterial assemblages and recycling soil organic matter88,89. The roles of ciliates (e.g., grazing bacteria and viruses90) may increase as permafrost thaw continues and these environments become inundated with water, suggesting their viruses will also become more abundant and play larger roles in carbon cycling (e.g., via the viral shunt). Additionally, one of the cressdnavirus vOTUs fell into the newly created genus Naryaviridae, which are only known to infect Entamoeba91. Entamoeba is a genus of Amoebozoa, they are internal parasites of animals and are known to be able to survive in permafrost (Shmakova and Rivkina, 2015). These protists can be infected by ssDNA viruses92,93, giant DNA viruses94, and RNA viruses95, and may provide a means for viruses to persist in permafrost.

Stordalen Mire viruses are associated with dominant and major C cycling microbial lineages

Beyond infecting key carbon cycling microbes in Stordalen Mire, we next explored whether the viruses might impact ecosystem biogeochemistry by carrying AMGs that may augment host microbial metabolism. The vOTUs were investigated using DRAM-v96 with an additional, customized database reflecting carbohydrate utilization profiles of the MAGs from the same system (Supplementary Data 6)7. We identified 811 putative AMGs from 658 vOTUs, 652 AMGs were previously reported in viruses (see methods) and 30 of which were previously experimentally verified, i.e., shown in a microbial host to provide a specific function (Fig. 6a). Functions of the genes were assigned to carbon utilization (48%), organic nitrogen metabolism (~2%), miscellaneous (45%), energy metabolism (3.5%), and transporter (1%) categories (Fig. 6c). In each category, certain subcategories were more prevalent, such as carbohydrate active enzymes (CAZymes) in carbon utilization, amino acid utilization and transformations in organic nitrogen, information systems in miscellaneous, and sulfur metabolism in energy. The detection of AMGs and the diversity in AMG functions increased with thaw (29% identified in virus genomes from palsa, 31% in bog, and 40% in fen), mirroring microbial and plant compound diversity7,97. We leveraged our virus-host linkages to provide the lineage-specific microbial metabolism that these AMGs may be augmenting and identified 232 vOTUs linked to 28 archaeal and 204 bacterial taxa in total, including 169 Stordalen Mire MAGs associated with 76 distinct AMGs.

a The portion of the 811 AMGs recovered by DRAM-v that have been experimentally verified, previously reported (known), and previously unreported (putative AMG). b The metabolic assignments of the AMGs, separated into the five major functional categories and subcategories. c Cellulose and xylan (hemicellulose) degradation pathways feeding into methanogenesis, as previously reported7. Blue arrows denote genes in the pathways were detected in viral genomes, and gray denotes that no genes were detected. For each pathway step, the number of AMGs is shown in blue text, and the number of vOTUs encoding those AMGs is shown in red text. d The distribution of glycoside hydrolase (GH) families carried by vOTUs that can degrade cellulose or hemicellulose, and the number of GHs detected. The dot plot specifies the GH’s function and the cleavage site.

Focusing on the AMGs involved in carbon cycling, which was the most abundant metabolic gene type detected, these genes were involved in many important facets of microbial carbon cycling previously identified in Stordalen Mire7, including degradation of large carbon polymers (polysaccharides) and carbon monomers (monosaccharides) for utilization of sugars, and short-chain fatty acid interconversions that can supply the substrates needed for methanogenesis (Fig. 6c). Previous Stordalen Mire research showed that more than half of the microbial populations that had the potential to degrade cellulose also had the capacity for xylan degradation, with most xylan degradation activity (inferred by metatranscriptomics) occurring by Actinobacteriota in the palsa, Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, and Verrucomicrobiota in the bog, and Bacteroidota, mainly Ignavibacteria, in the fen. Most of the identified microbial hosts belonged to the phyla Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, Bacteroidota, and Verrucomicrobiota. It is likely that Acidobacteriota (cellulase- and xylanase-encoding) are the primary degraders of large polysaccharides in the palsa and bog (61 and 75% of Acidobacteriota genomes, respectively7, revealing the high potential for viruses to dictate the fate of the complex carbon that makes up most of the peat matrix98. Interestingly, most Acidobacteriota populations did not have the capability for xylan degradation, but did encode genes for xylose degradation, and in our data, we found 14 AMGs for xylan degradation carried by 14 vOTUs, but none for xylose degradation (Fig. 6c). While none of our virus-host linkages could provide information on which specific microbes these viruses infect, we posit viruses carry these AMGs alleviating a bottleneck in this microbial degradation pipeline contributing to the formation of more labile products promoting carbon loss from these peatlands.

We continued our investigation of viral roles in the microbial degradation pipeline, starting with complex carbohydrate degradation and continuing down to degradation of more labile compounds. The most prevalent carbon cycling AMGs encoded for CAZymes, with 57 vOTUs carrying 59 glycoside hydrolases (GHs, spanning nine families), which catalyze the hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds. Focusing on the GHs that enable the turnover of complex carbohydrates to smaller, more labile carbon compounds, the most abundant GHs belonged to GH5 (n = 12), GH16 (n = 15), GH71 (n = 8), and GH43 (n = 18) families (Fig. 6d). Notably, each of these GHs have the capacity to degrade cellulose or hemicellulose (e.g., xylan), both of which were important polysaccharide substrates for microorganisms in Stordalen Mire. Once plant- and microbially derived substrates are degraded, they can be fuel for other microbial metabolisms, including methylotrophy and methanogenesis, which were recently identified to be key drivers of CH4 dynamics in the Mire7,11,80, where viral abundance was found to help predict30. We identified 45 vOTUs that carried genes for the degradation of monosaccharides such as mannose (via mannose-6-phosphate isomerase or mannose 4,6-dehydratase) and galactose (via UDP-glucose 4-epimerase or glucose dehydrogenase), and ten of the vOTUs contained ten AMGs that were linked to hosts from Acidobacteriota. At lower trophic levels, AMGs were identified with the potential for short-chain fatty acid and C1 compound interconversions, including acetate kinase (n = 2), acylphosphatase (n = 1), phosphate acetyltransferase (n = 1), pyruvate formate lyase activating enzyme (n = 1), and other dehydrogenases (i.e., 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase n = 1, 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase n = 1, and Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex n = 1). These enzymes are involved in the production and processing of acetate, butyrate, and other short-chain fatty acids that could feed methanogenic pathways. Acetate, in particular, can be consumed by acetoclastic methanogens, or it could also be scavenged by Firmicutes (which account for 0.5% of the 1529 MAGs) to produce butyrate or propionate99,100. If propionate is produced, then Deltaproteobacteria (6.2% of MAGs) may oxidize it to acetate, syntrophically fueling acetoclastic methanogenesis101, which has been found previously in peatlands102 and was previously suggested for Stordalen Mire29. Further, the detection of vOTUs carrying AMGs linked to these pathways is consistent with the known vertical and habitat-specific structuring of active methanotrophs and their methane-oxidizing activity across the thaw gradient11, reinforcing the potential for viruses to influence key steps in permafrost-associated methane cycling.

In addition to shaping active carbon turnover, viruses may influence long-term carbon storage. We identified six vOTUs carrying aspartate racemase (racD), which converts L- to D-aspartate, producing amino acid forms less accessible to microbial degradation103,104. We speculate these viruses carry racD AMGs to ensure a sufficient supply of D-aspartate, an important building block for the maintenance of the bacterial peptidoglycan cell wall. By controlling the availability of D-amino acids, the virus prevents premature lysis of the host cell, which would release incomplete or defunct virions105,106. This control allows the virus to maximize the duration of its productive cycle, ensuring an optimal and functional virion yield. Racemization may also stabilize microbial necromass—a major, persistent component of soil organic matter. Four of the racD-carrying vOTUs were found in Sphagnum-dominated bogs, where acidic conditions and Sphagnum-derived phenolics and galacturonic acid suppress microbial activity and decomposition98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107. Viral racD AMGs may amplify these effects by further reducing necromass turnover, promoting soil organic matter persistence. As permafrost thaw shifts bogs toward more microbially active fen habitats, these viral- and plant-mediated protection effects diminish, accelerating soil organic matter loss and methane release98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107. Stordalen Mire is a peatland and is currently thought to store carbon, acting as a carbon sink, but with permafrost thaw, it is becoming a productive wetland, releasing carbon as CO2 and CH4 through microbial-mediated processes7. Identification of Stordalen Mire viruses that carry carbon cycling AMGs, often linked to dominant hosts, suggests that viruses play an underappreciated but potentially pivotal role in regulating soil carbon cycling.

Climate change-driven permafrost thaw is transforming Stordalen Mire from low-productivity, dry palsa into wetter, more microbially and plant-diverse fen habitats. Although these peatlands currently function as carbon sinks, this feature depends on the quantity and quality of organic matter content available and the activity of microbial inhabitants that mediate its transformation. In this study, we characterized thousands of novel ssDNA and dsDNA virus populations and show that viral diversity, virus-host associations, and the functional diversity of AMGs all increased with permafrost thaw. This increased recovery of soil viral diversity through a modified library preparation protocol and our optimized bioinformatics pipeline provided novel insights into understudied viral groups. Many AMGs supported complex carbohydrate degradation and downstream processing of labile carbon compounds, including acetate and C1 intermediates, implicating viruses in both early and late stages of the microbial carbon degradation pipeline. The detection of AMGs involved in methylotrophy and acetate turnover is particularly relevant given the ecological importance of these metabolisms across the Mire. This work advances the long-standing goal of achieving comprehensive, meta-omics–driven characterization of soil viromes. The contextualization of Stordalen Mire viruses within known microbial carbon pathways, including those involved in methanogenesis and methane oxidation, provides new mechanistic insights into how viruses influence microbial metabolic networks and potentially affect greenhouse gas dynamics in thawing permafrost ecosystems. Together, our findings emphasize the need to integrate viral processes into genome-scale metabolic models of ecosystem-scale biogeochemical frameworks. Given the global importance of peatlands and permafrost in the carbon cycle, and the detection of carbon cycling genes in indigenous viruses, the role of these viruses in the global carbon cycle could be significant.

Methods

Generating viromes

Soil cores from Stordalen Mire were collected in triplicate during the third week of July 2016 and 2017, immediately frozen with liquid nitrogen, shipped to Columbus, Ohio, and stored at −80 °C until processed in October 2017 (Supplementary Data 7). Viruses were resuspended from twenty samples from depths 10–14 and 30–34 cm in 2016 samples, and from depths 1–5, 10–14, 20–24, and 30–34 cm in 2017, using a previously optimized method (Fig. 1)44,45. Briefly, 10 ml of a 1% potassium citrate (K3C6H5O7) buffer amended with 10% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 150 mM magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) was added to 10 ± 0.5 g peat samples in triplicate. The viruses were physically desorbed from soil colloids using vortexing for 1 min and manual shaking for 30 s, then shaking the tubes at 400 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and finally, the tubes were centrifuged for 20 min at 4700 ×g at 4 °C to pellet debris, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. The resuspension steps above were repeated two more times, and the supernatants were combined and filtered through a 0.2 µm polyethersulfone (PES) membrane filter. The viral DNA was extracted using DNeasy PowerSoil extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, cat# 12888), using a heat lysis step: 10 min at 70˚C, vortex for 5 s and then continue incubating at 70˚C for another 5 min. The extracted DNA was quantified using a Qubit-fluorometer (Invitrogen), and the 20 samples were split into duplicates, making 40 samples. The Accel-NGS 1S Plus DNA library kit (Swift Biosciences, Ann Arbor, USA) was previously shown to quantitatively capture ssDNA and dsDNA viruses, but to evaluate how well it captures dsDNA viruses, we compared it to a traditionally used Nextera XT DNA library kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Therefore, half of the samples had libraries prepared using the Accel-NGS kit (Washtenaw County, Michigan) and the other half using the Nextera XT kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA; cat# FC-131-1024). The 40 virome libraries were sequenced with Illumina HiSeq-1TB, run type 2 ×151 (Supplementary Data 8). The Accel-NGS 1S plus was the designation at Swift BioSciences, which is no longer in business. The comparable kit for the new manufacturer (Integrated DNA Technologies) is “xGen ssDNA and low-input”. Recently, the SRSLY kits (ClaretBio, Santa Cruz, CA) were proposed and could provide another option for quantitative ssDNA/dsDNA viromics.

Viral sequence identification and relative abundance estimation

All 40 viromes underwent virus-specific bioinformatic analyses, with the goals of optimizing assembly to aid in virus discovery and increasing read assembly from low-input libraries52 (Supplementary Data 8). Briefly, the optimized pipeline included “relaxed” read correction with Tadpole (v. 37.76: https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/bbtools/) to correct sequencing errors by leveraging kmer frequency along each read (parameters “mode=correct ecc=t prefilter=2″), read deduplication with Clumpify (v37.76: https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/bbtools/), in which identical reads are identified and only one copy retained (parameters: “dedupe subs = 0 passes = 2″), and assembly using SPAdes (v. 3.11)108,109 with error correction step skipped, single-cell option and k-mers 21, 33, 55, 77, 99, and 127. Assemblies were evaluated using standard metrics computed with stats.sh from the bbtools suite (https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/bbtools/)52. To distinguish viral from microbial contigs, the contigs were processed with VirSorter2 v2.2.4110 and geNomad v1.8.1111. Contigs were also compared by BLAST112 to a pool of possible laboratory contaminants (i.e., phages cultivated in the lab where soil samples were processed: Enterobacteria phage phiX17, Alpha3, M13, Cellulophaga baltica phages, and Pseudoalteromonas phages; RefSeq genomes identifiers NC_001422.1, NC_001330.1, NC_003287.2, NC_021788.1, NC_021798.1, NC_021806.1, NC_021789.1, NC_021792.1, NC_021796.1, NC_021803.1, NC_021794.1, NC_021799.1, NC_021802.1, NC_021790.1, NC_021791.1, NC_021795.1, NC_021800.1, NC_021804.1, NC_021793.1, NC_021805.1, NC_021797.1, NC_048630.1, NC_070825.1, NC_070826.1, NC_070820.1, and NC_015293.1) and to a list of ssDNA virus sequences that can commonly contaminate DNA extraction columns113. The seven contigs matching these genomes at more than 95% average nucleotide identity (ANI) were removed.

These dsDNA viral contigs (identified in both library approaches) were clustered at 95% ANI and 85% alignment fraction (AF) to create a final vOTU dataset114, and their quality was assessed with CheckV v1.0.1 default parameters115 (Supplementary Data 1). We taxonomically classified the dsDNA vOTUs using a gene-sharing network as implemented in vConTACT2 v. 0.9.19 using prokaryotic viral refseq v. 85 with taxonomy approved by The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (Supplementary Data 2)60. As is common for soil virome work, only a small amount of DNA was extracted from these samples, which strains the library preparation methods and requires relaxation of read-mapping along the contigs requirements to see “biological” signals44,116,117. Therefore, reads were mapped back to the nonredundant set of contigs at 90% ANI and two thresholds for the length of contig covered with Read2RefMapper v1.1.1118 to estimate coverage: 75% contig coverage for our strict threshold as it offers robust coverage of well-sampled populations117, and 10% for our relaxed threshold because it increases read recruitment to the contigs which we hypothesized would allow detection of less abundant viruses and highlight more differences between the library kits44,116,119. The relaxed coverage threshold was only used for library comparisons, and the strict threshold was used for characterization of the vOTUs. Relative abundance was calculated as the number of bases mapped to each read normalized by the length of the contig, and by the total number of bases sequenced in the metagenome using Bowtie 2117,120 (Supplementary Data 9). The vOTU relative abundance heat map was constructed in R v4.2.2 pheatmap v1.0.12. Ecological diversity indices of vOTUs were performed using MetaPop121 for microdiversity and in R Vegan v. 2.6.4 for alpha diversity and visualized with ggplot2 v3.4.0, and accumulation curves with specaccum (method = “random”, permutations = 100, conditioned = TRUE, gamma = “jack2“). Kruskal–Wallis tests and Dunn’s post hoc tests were used (α = 0.05) to make pairwise comparisons among the diversity indices for the habitats. To assess differences in viral community composition among library preparation methods, we log-transformed viral contig abundance data at both 75% and 10% thresholds and calculated Bray-Curtis dissimilarities using the vegan v. 2.6.4 in R. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance was performed to test for global differences among library types, followed by pairwise PERMANOVA (pairwiseAdonis package) for specific comparisons. To validate the results, we also conducted an Analysis of Similarities. Principal coordinates analysis was used for visualization, and Mahalanobis distances122 were computed on the first two axes to identify multivariate outliers, defined as samples exceeding the 95th percentile. Outliers were highlighted in Principal coordinates analysis plots generated using ggplot2 v3.4.0, with 95% confidence ellipses around each library type. Linear regression analysis of the recovered viral contigs was done in Excel with the data analyses package, and outliers were identified by finding the difference between the first and third quartiles of the distribution and multiplying it by 2.2123,124.

A two-step approach was used to specifically identify ssDNA contigs. First, putative complete ssDNA virus genomes were identified based on hmmsearch v3125 (cutoffs: score ≥50 and e-value ≤0.001) hits on circular contigs to ssDNA marker genes from the PFAM database: Phage_F (also known as major capsid protein, MCP) and Viral_Rep (also known as replication-associated protein, Rep) domains (HMMER v3; cutoffs: score ≥50 and e-value ≤0.001). The protein sequences similar to the MCP or Rep domains were aligned and used to build new HMM profiles (available at: 10.5281/zenodo.8353597), which were then searched against the set of metagenome-predicted proteins (from VirSorter2 v2.2.4110), using the same hmmsearch approach with similar cutoffs as previously and size thresholds of 1–5 kb for Rep/cressdnaviruses and 4–8 kb for MCP/microviruses.

The open reading frames (ORFs) of the cressdnaviruses (only complete genomes) were determined using ORFfinder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/) coupled with manual curation of the splice sites to identify the intron in the replication-associated protein (Rep) CDS. The cressdnaviruses were manually annotated based on known ORFs of cressdnavirus Rep and CP. ORFs and annotation of the viruses in the family Microviridae were determined using RASTtk v1.3126 with manual refinement. These assembled ssDNA virus contigs were manually checked for terminal redundancy to determine circularity and were only retained if circular. Complete circular genomes of cressdnaviruses and microviruses were linearized starting at the start of the Rep or MCP coding sequences, respectively.

Second, to expand our search, we ran all contigs through geNomad (500 bases)111, which uses a large dataset of marker proteins to provide functional gene annotation and taxonomic assignment of viral genomes. We used this marker gene-based survey to detect more putative ssDNA viruses, provide taxonomic affiliation (Supplementary Data 10), and gene annotation (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8384701). The ssDNA viral genomes >500 bases were then clustered into vOTUs, and normalized coverage profiles were established following the methods stated above for the dsDNA vOTUs.

Relating vOTUs to other Stordalen Mire vOTUs and global vOTUs

To compare recovered vOTUs to those known globally, we clustered them against previous vOTU data from the same site29,30,42,44, other soils33,39,40,59,65,66,67,68,69, marine systems22, the human gut62, and NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq v226). The vOTUs from all the datasets were clustered at 95% ANI and 85% AF to determine if the vOTUs were unique or shared among the datasets. To quantitatively visualize the data, we generated two static UpSet plots in R127; databases and other information is in Supplementary Data 4).

The 676 complete ssDNA vOTUs spanning Cressdnaviricota and Microviridae were further interrogated by comparing them with previously reported Stordalen Mire ssDNA vOTUs44, Les Pradeaux Mire ssDNA viruses77,78 and with ssDNA viruses in GenBank. Reps from species of classified cressdnaviruses as well as alphasatellites were clustered with CD-HIT128 at 60% amino acid identity to generate a representative subsample of these. A representative of each of these clusters, together with 2587 Reps amino acid sequences of unclassified cressdnaviruses genomes available in GenBank (downloaded October 5, 2021) and 574 Rep amino acid sequences of cressdnaviruses identified in this study, were aligned using MAFFT129. The MCP amino acid sequences of Microviridae (n = 3153) genomes available in GenBank were aligned with 102 MCPs from this study and eight representative bullavirus MCPs using MAFFT v7.505129.

The resulting alignments of the Rep and MCPs was trimmed using trimAl v1.3 (gap threshold of 0.2)130 and used to infer a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree using IQTree2131 with Q.pfam+F + G4 substitution model and aLRT branch support. The resulting phylogenetic tree was midpoint rooted and visualized in iTOLv6 and represented as cladogram132.

Linking vOTUs to microbial hosts

We used two approaches based on sequence similarity to predict hosts for the vOTUs. The vOTU representative sequences were compared to the 1529 Stordalen Mire MAGs7 using BLASTn112 (options -dust no -perc_identity 70) based on shared genomic content133, and any vOTU with a bit score ≥50, E-value ≤10−3, and ≥70% identity across ≥2500 bp were considered for host prediction (Supplementary Data 5). CRISPR spacer matches were also used to link viruses from this study to the Stordalen Mire MAGs7. To identify CRISPRs in silico from the MAGs, we used minced v0.3.2134 (https://github.com/ctSkennerton/minced) to extract CRISPR spacers. After removal of spacer sequences with at least one ambiguous base (two spacers), we identified a total of 3560 spacer sequences. We searched the 3560 spacer sequences against all the dsDNA and ssDNA viral population representatives using BLASTn112, with the BLASTn-short option and default parameters except for “-qcov_hsp_perc 100”. After conservatively filtering for matches with 100% sequence identity, we detected 42 total spacer-virus matches (Supplementary Data 5). We traced the MAG in which each CRISPR spacer was derived to link the microbial host to its virus. Bar plots were made in R using ggplot2135 to visualize virus-host connections.

We used an additional integrated approach, iPHoP (Integrated Phage Host Prediction136), to increase the number of vOTUs connected to host taxa. Briefly, iPHoP attempts to link input phage sequences to a host taxon (typically at a genus or family rank) based on a combination of (i) direct sequence comparison to host genomes and CRISPR spacers, (ii) overall nucleotide composition comparison to host genomes, and (iii) comparison to phages with known hosts. Here, we first used iPHoP v1.2.0 with default parameters to predict hosts for all vOTU representatives based on the default iPHoP database (Sept_2021_pub). Next, we built a custom iPHoP database by adding 1,529 Stordalen Mire MAGs7 to the default GTDB-based iPHoP database (using the “add_to_db” function) and ran a second host prediction on the same vOTU representatives. Host predictions were filtered using a minimum score of 75, each vOTU was connected to the host taxon (at the family rank or if ≥90, the genus rank if available) with the highest score across both iPHoP runs (default and custom database). Host predictions by iPHoP were ignored for vOTUs predicted to infect eukaryotes based on their taxonomic classification (e.g., Cressdnaviricota), as these sequences are known to yield false-positive prokaryotic host predictions.

Predicting viral auxiliary metabolic genes from viral contigs

Identification and curation of AMGs were performed following a recently established standard operating protocol137. First, all detected viruses were annotated with DRAM-v 1.0 (Supplementary Data 6) and then AMGs were detected for vOTUs with DRAM-v96. Because DRAM-v relies on outputs VirSorter/Virsorter2 for determining confidence in classifying AMGs, we ran the geNomad-identified vOTUs through a recently developed modular viromics pipeline (v 1.0)138 designed to generate the required affiliation file format compatible with DRAM-v. We then identified AMGs using DRAM-v with the --use_uniref flag enabled and the following databases: PFAM v33.1, KEGG v89.1, dbCAN v9, MEROPS v120, and VOGDB database (Dec. 2024)96. For each gene on a viral contig that DRAM-v annotated as metabolic (M flag), a score, from 1 to 5 (1 being most confident), denotes the likelihood that the gene belongs to a viral genome rather than a degraded prophage region or a poorly defined viral genome boundary96. To link these viruses more readily to the carbon cycle in this system, we included 46 genes as putative AMGs (added to DRAM database) that were highlighted to be important in ecosystem carbon cycling7 (Supplementary Data 6). To minimize the number of false positives, we considered only genes that had a gene ID or a gene description and removed genes with a “viral” flag (V), transposon flag (T), viral-like peptidase (P), or attachment flag (A). If the AMG had been previously identified in the literature according to the DRAM-v database, it received a “K” flag (known) and if the AMG was known and had also been experimentally verified in a previous study (meaning it has been shown in a host to provide a specific function), it received an “E” flag and was labeled “experimentally verified”. The remaining AMGs were labeled as “putative AMGs”. For category assignment (e.g., carbon utilization), AMGs were assigned first by DRAM-v provided categories, and if no category was provided by DRAM-v, the genes were manually assigned to each category based on DRAM annotation.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Reads for the different metagenomes are available on https://genome.jgi.doe.gov/portal/ and the SRA database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra). Sample accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Data 8, and GenBank accession numbers for the 676 complete ssDNA vOTUs are listed in Supplementary Data 10. The HMMs generated for ssDNA viruses are available on Zenodo: 10.5281/zenodo.8353597. The 9963 ssDNA and dsDNA vOTUs sequences are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15637204.

Code availability

Custom Perl scripts used in this study are available at https://bitbucket.org/srouxjgi/scripts_pcrlibs_assembly_optimization/src/master/ and https://bitbucket.org/bolduc/docker-read2refmapper/src/master/.

References

McGuire, A. D. et al. Dependence of the evolution of carbon dynamics in the northern permafrost region on the trajectory of climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 3882–3887 (2018).

Schuur, E. A. & Mack, M. C. Ecological response to permafrost thaw and consequences for local and global ecosystem services. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 49, 279–301 (2018).

Åkerman, H. J. & Johansson, M. Thawing permafrost and thicker active layers in sub-arctic Sweden. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 19, 279–292 (2008).

Crowther, T. W. et al. Quantifying global soil carbon losses in response to warming. Nature 540, 104–108 (2016).

Shukla, P. R. et al. IPCC, 2019: Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems (2019).

Hultman, J. et al. Multi-omics of permafrost, active layer and thermokarst bog soil microbiomes. Nature 521, 208–212 (2015).

Woodcroft, B. J. et al. Genome-centric view of carbon processing in thawing permafrost. Nature 560, 49–54 (2018).

Mackelprang, R., Saleska, S. R., Jacobsen, C. S., Jansson, J. K., & Taş, N. Permafrost meta-omics and climate change. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 44, 439–462 (2016).

Ward, C. P., Nalven, S. G., Crump, B. C., Kling, G. W. & Cory, R. M. Photochemical alteration of organic carbon draining permafrost soils shifts microbial metabolic pathways and stimulates respiration. Nat. Commun. 8, 772 (2017).

Mondav, R. et al. Microbial network, phylogenetic diversity and community membership in the active layer across a permafrost thaw gradient. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 3201–3218 (2017).

Singleton, C. M. et al. Methanotrophy across a natural permafrost thaw environment. ISME J. 12, 2544–2558 (2018).

Wu, M. H. et al. Reduced microbial stability in the active layer is associated with carbon loss under alpine permafrost degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2025321118 (2021).

Hough, M. et al. Biotic and environmental drivers of plant microbiomes across a permafrost thaw gradient. Front. Microbiol. 11, 796 (2020).

Wilson, R. M. et al. Plant organic matter inputs exert a strong control on soil organic matter decomposition in a thawing permafrost peatland. Sci. Total Environ. 820, 152757 (2022).

McCalley, C. K. et al. Methane dynamics regulated by microbial community response to permafrost thaw. Nature 514, 478–481 (2014).

Carreira, C. et al. Integrating viruses into soil food web biogeochemistry. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 1918–1928 (2024).

Fuhrman, J. A. Marine viruses and their biogeochemical and ecological effects. Nature 399, 541–548 (1999).

Suttle, C. A. Viruses in the sea. Nature 437, 356–361 (2005).

Suttle, C. A. Marine viruses-major players in the global ecosystem. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 801–812 (2007).

Breitbart, M. Marine viruses: truth or dare. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 4, 425–448 (2012).

Guidi, L. et al. Plankton networks driving carbon export in the oligotrophic ocean. Nature 532, 465–470 (2016).

Gregory, A. C. et al. Marine DNA viral macro-and microdiversity from pole to pole. Cell 177, 1109–1123 (2019).

Howard-Varona, C. et al. Phage-specific metabolic reprogramming of virocells. ISME J. 14, 881–895 (2020).

Dominguez-Huerta, G. et al. Diversity and ecological footprint of Global Ocean RNA viruses. Science 376, 1202–1208 (2022).

Zimmerman, A. E. et al. Metabolic and biogeochemical consequences of viral infection in aquatic ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 21–34 (2020).

Howe, A. C. et al. Tackling soil diversity with the assembly of large, complex metagenomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 4904–4909 (2014).

Thompson, L. R., The Earth Microbiome Project Consortium et al. A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature 551, 457–463 (2017).

Goordial, J. et al. Comparative activity and functional ecology of permafrost soils and lithic niches in a hyper-arid polar desert. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 443–458 (2017).

Trubl, G. et al. (2018). Soil viruses are underexplored players in ecosystem carbon processing. mSystems 3, e00076-18 (2018).

Emerson et al. Host-linked soil viral ecology along a permafrost thaw gradient. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 870–880 (2018).

Lee, S. et al. Methane-derived carbon flows into host–virus networks at different trophic levels in soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2105124118 (2021).

Starr, E. P. et al. Stable-isotope-informed, genome-resolved metagenomics uncovers potential cross-kingdom interactions in rhizosphere soil. Msphere 6, e00085–21 (2021).

Trubl, G. et al. Active virus-host interactions at sub-freezing temperatures in Arctic peat soil. Microbiome 9, 1–15 (2021).

Barnett, S. E. & Buckley, D. H. Metagenomic stable isotope probing reveals bacteriophage participation in soil carbon cycling. Environ. Microbiol. 25, 1785–1795 (2023).

Nicolas, A. M. et al. A subset of viruses thrives following microbial resuscitation during rewetting of a seasonally dry California grassland soil. Nat. Commun. 14, 5835 (2023).

Trubl, G., Hyman, P., Roux, S. & Abedon, S. T. Coming-of-age characterization of soil viruses: a user’s guide to virus isolation, detection within metagenomes, and viromics. Soil Syst. 4, 23 (2020).

Williamson, K. E., Fuhrmann, J. J., Wommack, K. E. & Radosevich, M. Viruses in soil ecosystems: an unknown quantity within an unexplored territory. Annu. Rev. Virol. 4, 201–219 (2017).

Cao, M. M. et al. Distribution characteristics of soil viruses under different precipitation gradients on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Front. Microbiol. 13, 848305 (2022).

Santos-Medellín, C. et al. Viromes outperform total metagenomes in revealing the spatiotemporal patterns of agricultural soil viral communities. ISME J. 15, 1956–1970 (2021).

Ter Horst, A. M. et al. Minnesota peat viromes reveal terrestrial and aquatic niche partitioning for local and global viral populations. Microbiome 9, 233 (2021).

Bolduc, B. et al. The IsoGenie database: an interdisciplinary data management solution for ecosystems biology and environmental research. PeerJ 8, e9467 (2020).

Sun, C. L. et al. Virus ecology and 7-year temporal dynamics across a permafrost thaw gradient. Environ. Microbiol. 26, e16665 (2024).

Pratama, A. A. et al. RNA virus ecogenomics along a subarctic permafrost thaw gradient. Preprint at bioRxiv 2025-02 (2025).

Trubl, G. et al. Towards optimized viral metagenomes for double-stranded and single-stranded DNA viruses from challenging soils. PeerJ 7, e7265 (2019).

Trubl, G. et al. Optimization of viral resuspension methods for carbon-rich soils along a permafrost thaw gradient. PeerJ 4, e1999 (2016).

Duhaime, M. B., Deng, L., Poulos, B. T. & Sullivan, M. B. Towards quantitative metagenomics of wild viruses and other ultra-low concentration DNA samples: a rigorous assessment and optimization of the linker amplification method. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 2526–2537 (2012a).

Duhaime, M. B. & Sullivan, M. B. (2012b). Ocean viruses: rigorously evaluating the metagenomic sample-to-sequence pipeline. Virology, 434 181–186 (2012b).

Solonenko, S. A., & Sullivan, M. B. (2013a). Preparation of metagenomic libraries from naturally occurring marine viruses. Methods Enzymol. 531, 143–165 (2013a).

Solonenko, S. A. et al. Sequencing platform and library preparation choices impact viral metagenomes. BMC Genom. 14, 320 (2013b).

Roux, S. et al. Towards quantitative viromics for both double-stranded and single-stranded DNA viruses. PeerJ 4, e2777 (2016).

Rinke, C. et al. Validation of picogram-and femtogram-input DNA libraries for microscale metagenomics. PeerJ 4, e2486 (2016).

Roux, S. et al. Optimizing de novo genome assembly from PCR-amplified metagenomes. PeerJ 7, e6902 (2019a).

Marine, R. et al. Evaluation of a transposase protocol for rapid generation of shotgun high-throughput sequencing libraries from nanogram quantities of DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 8071–8079 (2011).

Jones, M. B. et al. Library preparation methodology can influence genomic and functional predictions in human microbiome research. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 14024–14029 (2015).

Rihtman, B., Meaden, S., Clokie, M. R., Koskella, B. & Millard, A. D. Assessing Illumina technology for the high-throughput sequencing of bacteriophage genomes. PeerJ 4, e2055 (2016).

Sato, M. P. et al. Comparison of the sequencing bias of currently available library preparation kits for Illumina sequencing of bacterial genomes and metagenomes. DNA Res. 26, 391–398 (2019).

Gunasekera, S. et al. Evaluating coverage bias in next-generation sequencing of Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 16, e0253440 (2021).

Bruinsma, S. et al. Bead-linked transposomes enable a normalization-free workflow for NGS library preparation. BMC Genom. 19, 1–16 (2018).

Santos-Medellín, C. et al. Spatial turnover of soil viral populations and genotypes overlain by cohesive responses to moisture in grasslands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2209132119 (2022).

Jang, H.-B. et al. Taxonomic assignment of uncultivated prokaryotic virus genomes is enabled by gene-sharing networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 632–639 (2019).

Roux, S., Enault, F., Hurwitz, B. L. & Sullivan, M. B. VirSorter: mining viral signal from microbial genomic data. PeerJ 3, e985 (2015).

Gregory, A. C. et al. The gut virome database reveals age-dependent patterns of virome diversity in the human gut. Cell Host Microbe 28, 724–740. e728 (2020).

Brum, J. R. et al. Patterns and ecological drivers of ocean viral communities. Science 348, 1261498 (2015).

Lee, S. et al. Soil pH influences the structure of virus communities at local and global scales. Soil Biol. Biochem. 166, 108569 (2022).

Van Goethem, M. W., Swenson, T. L., Trubl, G., Roux, S., & Northen, T. R. Characteristics of wetting-induced bacteriophage blooms in biological soil crust. mBio 10, e02287-19 (2019).

Ter Horst, A. M., Fudyma, J. D., Sones, J. L. & Emerson, J. B. Dispersal, habitat filtering, and eco-evolutionary dynamics as drivers of local and global wetland viral biogeography. ISME J. 17, 2079–2089 (2023).

Santos-Medellín, C., Blazewicz, S. J., Pett-Ridge, J., Firestone, M. K. & Emerson, J. B. Viral but not bacterial community successional patterns reflect extreme turnover shortly after rewetting dry soils. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1809–1822 (2023).

Durham, D. M. et al. Substantial differences in soil viral community composition within and among four Northern California habitats. ISME Commun. 2, 100 (2022).

Trubl, G. et al. Soil redox drives virus-host community dynamics and plant biomass degradation in tropical rainforest soils. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.13.612973 (2024).

Graham, E. B. et al. A global atlas of soil viruses reveals unexplored biodiversity and potential biogeochemical impacts. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 1873–1883 (2024).

López-Bueno, A. et al. High diversity of the viral community from an Antarctic lake. Science 326, 858–861 (2009).

Zawar-Reza, P. et al. Diverse small circular single-stranded DNA viruses identified in a freshwater pond on the McMurdo Ice Shelf (Antarctica). Infect. Genet. Evol. 26, 132–138 (2014).

Aguirre de Cárcer, D., López-Bueno, A., Pearce, D. A. & Alcamí, A. Biodiversity and distribution of polar freshwater DNA viruses. Sci. Adv. 1, e1400127 (2015).

Dayaram, A. et al. Diverse circular replication-associated protein encoding viruses circulating in invertebrates within a lake ecosystem. Infect. Genet. Evol. 39, 304–316 (2016).

Sommers, P. et al. Single-stranded DNA viruses in antarctic cryoconite holes. Viruses 11, 1022 (2019).

de La Higuera, I. et al. Unveiling crucivirus diversity by mining metagenomic data. mBio 11, e01410–01420 (2020).

Quaiser, A. et al. Diversity and comparative genomics of Microviridae in Sphagnum-dominated peatlands. Front. Microbiol. 6, 375 (2015).

Quaiser, A., Krupovic, M., Dufresne, A., Francez, A.-J. & Roux, S. Diversity and comparative genomics of chimeric viruses in Sphagnum-dominated peatlands. Virus Evol. 2, vew025 (2016).

Kirchberger, P. C., Martinez, Z. A., & Ochman, H. Organizing the global diversity of microviruses. mBio 13, e00588-00522 (2022).

Ellenbogen, J. B. et al. Methylotrophy in the Mire: direct and indirect routes for methane production in thawing permafrost. Msystems 9, e00698–23 (2024).

Knezevic, P., Adriaenssens, E. M. & ICTV Report Consortium. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: inoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 102, 001614 (2021).

Cotmore, S. F., ICTV Report Consortium. et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Parvoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 100, 367–368 (2019).

Brentlinger, K. L. et al. Microviridae, a family divided: isolation, characterization, and genome sequence of φMH2K, a bacteriophage of the obligate intracellular parasitic bacterium Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. J. Bacteriol. 184, 1089–1094 (2002).

Krupovic, M. & Forterre, P. Microviridae goes temperate: microvirus-related proviruses reside in the genomes of Bacteroidetes. PLoS ONE 6, e19893 (2011).

Zucker, F. et al. New Microviridae isolated from Sulfitobacter reveals two cosmopolitan subfamilies of single-stranded DNA phages infecting marine and terrestrial Alphaproteobacteria. Virus Evol. 8, veac070 (2022).

McKee, L. S. et al. Polysaccharide degradation by the Bacteroidetes: mechanisms and nomenclature. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 13, 559–581 (2021).

Zhao, L., Lavington, E. & Duffy, S. Truly ubiquitous CRESS DNA viruses scattered across the eukaryotic tree of life. J. Evolut. Biol. 34, 1901–1916 (2021).

Coolen, M. J. L., Van De Giessen, J., Zhu, E. Y. & Wuchter, C. Bioavailability of soil organic matter and microbial community dynamics upon permafrost thaw. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 2299–2314 (2011).