Abstract

Aryl C-glycosides are privileged scaffolds in drug discovery, biochemical research, and materials science. Established methods for their synthesis typically involve radical cross-coupling of saccharides. However, the glycosyl donors required in these methods encounter longstanding challenges, including instability and the need for prefunctionalization at the anomeric position. Herein, we report a highly efficient radical cross-coupling approach in which the native hydroxyl group on saccharides is activated in situ by a phosphorus reagent, enabling C − C bond formation with aryl iodides to afford a broad range of aryl C-glycosides. A combination of Zn and I2 is developed for initiating the key β-scission step. Importantly, the glycosyl donors are bench-stable and readily available, addressing the issues associated with previous donors. Furthermore, this method offers an attractive strategy for the direct synthesis of drug-sugar conjugates and therapeutic agents. Mechanistic experiments and density functional theory (DFT) calculations provide strong support for the proposed reaction mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

C-Glycosides are an important class of glycosides in which the anomeric carbon of a saccharide moiety is linked to an aglycone via a C − C bond (Fig. 1a). This strong C−C bond contributes chemical and enzymatic stability to C-glycosides, distinguishing them from the more labile O- and N-glycosides1,2,3. The synthesis of C-glycosides has gained widespread interest in medicinal chemistry, as their robust structures enable the development of glycomimetics and inhibitors with enhanced metabolic stability4,5,6,7. Among the marketed or potential C-glycoside drugs, aryl C-glycosides represent a significant proportion due to their promising pharmacokinetic properties8,9,10. In recent years, aryl C-glycosides have been successfully developed into effective therapeutics, especially for treating diseases such as diabetes, infection, and cancer (Fig. 1a)11,12,13.

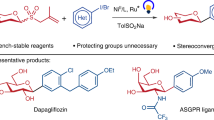

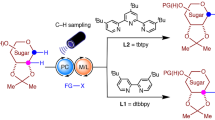

a Structure of C-glycosides and representative aryl C-glycosides in drug development. b Common glycosyl donors for accessing aryl C-glycosides. c Synthesis of aryl C-glycosides by activating native C − OH bond. d This work: direct deoxygenative arylation of saccharides via phosphorus-assisted β-scission. Et ethyl, Ar aryl, DHP dihydropyridine, NHC N-heterocyclic carbene, PC photocatalyst, tBu tert-butyl, Ph phenyl.

One of the most direct and efficient strategies for accessing aryl C-glycosides involves radical cross-coupling reactions between glycosyl donors and aryl halides or aryl metal reagents14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. In this approach, glycosyl donors serve as precursors to glycosyl radicals, which undergo C − C bond formation with aryl coupling partners to furnish the desired aryl C-glycosides. For example, a recent advancement by the Niu group has demonstrated the use of allyl glycosyl sulfones as radical precursors, enabling the efficient synthesis of unprotected aryl C-glycosides14. Similarly, the Koh group has reported glycosyl pyridyl sulfone as radical precursors for synthesizing aryl C-glycosides15. It is also noteworthy that Ye and co-workers have employed glycosyl phosphates in a ligand-controlled, diastereoselective C-glycosylation enabled by an unprecedented zirconaaziridine-mediated asymmetric nickel catalysis35. Other commonly used glycosyl donors, including glycosyl halides16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26, borates28,29, dihydropyridine esters30,31,32, and 1-deoxyglycosides33, have also been developed to access glycosyl radicals for the construction of aryl C-glycosides (Fig. 1b). While these glycosyl donors offer effective strategies for aryl C-glycosides synthesis, their instability or reliance on prefunctionalization at the anomeric position often limits their applicability. Therefore, it is highly desirable to develop a general radical cross-coupling method to access aryl C-glycosides using stable and easily accessible glycosyl donors.

Over the past few years, β-scission has emerged as a powerful strategy for enabling challenging C − O bond cleavage38. This approach often relies on N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) salts34,37,39,40,41,42,43 or main group elements such as phosphorus44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. Theoretically, β-scission offers a direct means to activate the native hydroxyl groups on saccharides for deoxygenative transformation, eliminating the need for prior functionalization at the anomeric position. Moreover, such glycosyl donors are typically stable, addressing the instability issues associated with some traditional glycosyl donors. However, compared to alkyl C-glycosides synthesis, the preparation of aryl C-glycosides is more challenging due to compatibility issues between the activation reagent and the metal catalyst. Consequently, this β-scission strategy has rarely been applied to the synthesis of aryl C-glycosides (Fig. 1c)34,37,43. One of the few successful examples is the NHC-mediated β-scission demonstrated by MacMillan and co-workers in 2021, in which only a few aryl C-glycosides were reported34. In light of these limitations, we sought to develop a β-scission strategy to enable the direct deoxygenative arylation of saccharides, applicable to synthesizing a diverse range of aryl C-glycosides.

Herein, we disclose that glycosyl radicals can be directly generated through the phosphorus-assisted β-scission. The resulting radicals undergo a nickel-catalyzed radical cross-coupling reaction with aryl iodides to produce a diverse array of aryl C-glycosides (Fig. 1d). This work represents an example in which a combination of Zn and I2 is used to activate phosphinite intermediates for radical generation. Furthermore, the glycosyl donors used in this reaction are bench-stable, with most being commercially available. Beyond the arylation of anomeric carbon, the alkylation of anomeric carbon and the arylation at the C6 position of saccharides are also demonstrated. Additionally, this method proves useful in synthesizing various drug-sugar conjugates and therapeutic agents. Mechanistic experiments, complemented by DFT calculations, are conducted to gain insights into the mechanism underlying this reaction.

Results and discussion

Reaction development

We initiated our study using bench-stable glycosyl donor 1a and aryl iodide 2a as model substrates to develop a method for the direct deoxygenative arylation of saccharides (Table 1, more details in Tables S1–S7). After extensive optimization, we established the optimal reaction conditions, achieving an isolated yield of 86% for the target product 3 on a 0.1 mmol scale (entry 1). The reaction protocol consisted of using NiCl2.dtbbpy as the catalyst, ClPPh2 as the phosphorus reagent, DMAP as the promoter for condensation, Cy2NH as the base, 1,4-dioxane as the solvent, Zn as the reductant, and I2 as the oxidant. Solvent screening revealed that replacing 1,4-dioxane with tetrahydrofuran (THF) led to a significant decrease in yield (entry 2), whereas the yield reduction was more moderate when using acetonitrile (MeCN) (entry 3) or 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME) (entry 4). Regarding the choice of reductant, alternative reductants such as Mn (entry 5) led to much lower yields. This phenomenon can be attributed to the stronger reducing potential of Mn, which may facilitate the over-reduction of both glycosyl radicals and nickel species55,56,57. The resulting side reactions, such as β-elimination to form glycals, ultimately lead to diminished yields of the desired product57. In the absence of DMAP to promote the condensation, the yield decreased slightly (entry 6). The organic base Cy2NH is crucial for condensation, and the yield decreased significantly without it (entry 7). Control experiments demonstrated that the nickel catalyst, phosphorus reagent, zinc, and iodine were indispensable for this reaction (entries 8 and 9). It is worth noting that the reaction was almost completely inhibited when all operations were carried out under air (entry 10).

Reaction scope

Upon establishing the optimized reaction conditions, we proceeded to explore the scope of the aryl iodide coupling partners (Fig. 2). We were delighted to find that a broad range of aryl iodides, with either electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups in the para-position, participated smoothly in this reaction (3-12, 19). In addition, a positive Hammett correlation (ρ = +0.32) indicates that electron-withdrawing substituents on the aryl iodide accelerate the reaction (see Supplementary Fig. 13 for more details). This trend suggests negative charge delocalization into the aryl ring during oxidative addition to low-valent nickel, which could contribute to the observed rate dependence in this coupling reaction58. The chemoselectivity was demonstrated when reacting with aryl iodides bearing chloro or bromo group (8, 9), owing to the higher oxidative addition rate of nickel catalyst to aryl iodides compared to aryl chlorides or bromides59. For meta-substituted aryl iodides (13, 14), a moderate decrease in yield was observed, whereas the yield declined more significantly with ortho-substituted aryl iodide (15). This phenomenon can be explained by the electronic and steric effects associated with substituent positioning. The disubstituted aryl iodides, including the analogue of the dapagliflozin (17), reacted in good yields to afford the desired products (16-18). Heterocycles, such as pyridines (20–21) and thiophenes (22), were also successfully incorporated to broaden the scope of this methodology.

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), 2 (0.2 mmol, 2.0 equiv.), NiCl2.dtbbpy (0.01 mmol, 10 mol%), ClPPh2 (0.11 mmol, 1.1 equiv.), DMAP (0.01 mmol, 10 mol%), and Cy2NH (0.12 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) in 1,4-dioxane (0.25 mL, 0.4 M) at room temperature for 20 min; then Zn (0.3 mmol, 3.0 equiv.), I2 (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) at room temperature for 18 h. Isolated yields are reported; All products observed and isolated occur as single anomer. Bn benzyl, dtbbpy 4,4’-di-tert-butyl-2,2’-dipyridyl; DMAP 4-dimethylaminopyridine, Cy cyclohexyl, Me methyl, Ac acetyl.

The late-stage functionalization of bioactive compounds to generate drug-sugar conjugates is a widely used strategy for improving the pharmacokinetic properties of drug candidates60. Accordingly, the synthesis of drug-sugar conjugates was highlighted to illustrate the practicality of our method (23-29). For example, menthol, specifically a monoterpenoid, is widely used to relieve minor throat irritation61. Its aryl iodide derivative was converted to the glycosylated conjugate (23) efficiently via the radical cross-coupling reaction. Similarly, the antitumor agent perillyl alcohol62 underwent conjugation to yield the desired product (24). Borneol, which is a traditional Chinese medicine63, was smoothly coupled with glycosyl donors to produce the target product (25). Galactopyranose, uridine, and cholesterol, each playing vital roles in biological systems64,65,66, were also compatible with the reaction conditions, delivering the corresponding conjugates (26–28) in good yields. Moreover, this glycosylation strategy extended to perfumery applications, as demonstrated with rhodinol derivative (29), where sugar conjugation holds the potential for optimizing its properties67.

We next investigated the substrate scope with respect to glycosyl donors (Fig. 3). In addition to the previously examined benzyl-protected saccharides, methyl (30, 33, 36), isopropylidene (31, 41-44, 46), acetyl (39, 40), and silyl (43, 44) protecting groups were also well tolerated. Beyond mannopyranose, both glucopyranose and galactopyranose demonstrated good reactivity, efficiently affording the corresponding products (32–36). However, despite extensive optimization, poor stereoselectivity was still observed in these products (32–36, see Table S8 for more details). This phenomenon can be attributed to the competing steric and stereoelectronic effects30. Specifically, the steric hindrance at the C2 position of the pyranose ring favors β-attack, whereas the transition state for α-attack benefits from stabilization via the kinetic anomeric effect. Notably, the β-anomer of product 34 serves as a key precursor to dapagliflozin, a widely used treatment for type II diabetes11. Other pyranoses, including rhamnopyranose, arabinopyranose, and glucosamine, efficiently yielded aryl C-glycosides (37-39) with excellent stereoselectivity under the standard reaction conditions. The high β-selectivities of 38 and 39 can be attributed to the strong steric hindrance of the C2 substituents on the α-face. Encouragingly, disaccharides underwent smooth deoxygenative arylation to form the desired products (40, 41) in good yields.

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), 2 (0.2 mmol, 2.0 equiv.), NiCl2.dtbbpy (0.01 mmol, 10 mol%), ClPPh2 (0.11 mmol, 1.1 equiv.), DMAP (0.01 mmol, 10 mol%), and Cy2NH (0.12 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) in 1,4-dioxane (0.25 mL, 0.4 M) at room temperature for 20 min; then Zn (0.3 mmol, 3.0 equiv.), I2 (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) at room temperature for 18 h. Isolated yields are reported; Unless otherwise noted, products observed and isolated occur as single anomer. NPhth N-phthalimido, TBDPS tert-butyldiphenylsilyl.

In addition to pyranoses, several furanoses were also tested in the deoxygenative arylation reactions. All tested substrates underwent efficient transformation, affording the corresponding products (42-45) in moderate to excellent yields, with only one single anomer observed. It is worth mentioning that the hydroxyl group at the C6 position can also participate in deoxygenative cross-coupling with aryl iodides. However, the primary alkyl radical generated at the C6 position is more susceptible to unproductive hydrogen atom abstraction, resulting in a low yield of the desired product (46).

Mechanistic study

Mechanistic experiments and DFT calculations were performed to elucidate the reaction pathway (see Supplementary Sections 6 and 7 for more details). The addition of a radical trap, such as benzyl acrylate, inhibited the reaction and led to the formation of the products from INT5 with benzyl acrylate, as well as the decomposition product likely derived from the reaction of INT4 with benzyl acrylate (Supplementary Fig. 4). This observation suggests that the reaction likely proceeds via a radical mechanism. We further hypothesized that glycosyl iodide might form as an intermediate during the reaction and could subsequently react to yield the desired product. To test this hypothesis, we directly used glycosyl iodide as substrate, affording the desired product in only 27% yield (Supplementary Fig. 5). This result suggests that, while glycosyl iodide may form transiently, it does not play a dominant role in the formation of the target product in our reaction. Moreover, INT1 could be directly used as the substrate to furnish the desired product in a comparable yield (Supplementary Fig. 7). NMR and HRMS analyses provide additional evidence for the involvement of INT2 and INT3 as intermediates in the reaction (Supplementary Fig. 10).

To gain further insight into the reaction pathway, comprehensive DFT calculations were performed, and the computed reaction energy profile for glycosyl radical generation was illustrated (Fig. 4a, see Supplementary Dataset for Cartesian coordinates). The oxidation of compound S1 by iodine68,69 is thermodynamically favorable, releasing 2.0 kcal/mol to yield intermediate S2. The hydrolysis of S270 is highly exothermic, with a Gibbs free energy change of -26.4 kcal/mol. Subsequently, a single-electron transfer (SET) step occurs on intermediate S3, where electron transfer from zinc is thermodynamically favorable, with a Gibbs free energy change of −76.6 kcal/mol, whereas electron transfer from the [NiI] complex is thermodynamically unfavorable, calculated at 55.5 kcal/mol. The kinetic barrier for this SET process was determined to be 17.3 kcal/mol using Marcus theory, supporting its feasibility. Following SET, the β-scission process of intermediate S4 proceeds with an energy barrier (TS-a) of 14.9 kcal/mol and releases 24.1 kcal/mol, indicating energetic accessibility at room temperature. This process results in the formation of glycosyl radical S5 and phosphinic acid S6, consistent with the detection of S6 by LC‑QTOF under standard conditions. Notably, the higher energy barrier of SET compared to β-scission identifies SET as the rate-determining step in this reaction pathway. Furthermore, the significantly higher energy barrier of 21.8 kcal/mol for the reduction of glycosyl iodide by the [NiI] complex suggests that glycosyl iodide is unlikely to play a dominant role in the formation of the desired product (Supplementary Fig. 17). This conclusion aligns well with the results of the mechanistic experiments.

Based on existing research16,17,18,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54, along with our mechanistic experiments and DFT calculations, we propose a plausible reaction mechanism (Fig. 4b). The sugar-phosphinite intermediate INT1, obtained from the condensation of the glycosyl donor 1 and phosphorus (III) chloride, undergoes oxidation with iodine to yield intermediate INT2. A trace amount of water induces the hydrolysis of INT2, yielding intermediate INT3, which is readily reduced by zinc. The resulting radical intermediate INT4 undergoes β-scission to generate the glycosyl radical INT5. Concurrently, the [NiI] complex engages in oxidative addition with an aryl iodide, forming a [NiIII] intermediate. Upon reduction by zinc, the [NiIII] complex is converted to the [NiII] complex. This [NiII] complex can capture the glycosyl radical INT5, and the following reductive elimination leads to the formation of the desired aryl C-glycoside product.

Synthetic applications

To showcase the synthetic utility of this strategy, a gram-scale preparation of aryl C-glycoside 3 was conducted (Fig. 5a). Extending the reaction time to 24 h afforded an 81% yield, only slightly lower than the 86% yield obtained on a 0.1 mmol scale. This methodology was also applied to the direct synthesis of biologically active C-glycosides (Fig. 5b, c). Benzamide riboside, a synthetic nucleoside analog, exhibits potent antitumor properties71. Under modified deoxygenative arylation conditions, its precursor (47) was synthesized in moderate yield. Subsequent amination and deprotection steps successfully yielded the target product, benzamide riboside (48). This product could be further transformed into BRDP-Hep (49)27, which is a potent activator of NF-kB signaling. In addition to the deoxygenative arylation of saccharides, deoxygenative alkylation was also achieved by modifying the standard reaction conditions. This process, performed without the nickel catalyst, enabled the reaction with acrylamide to produce alkyl C-glycoside 50 in 64% yield with complete α-selectivity. Subsequent deprotection of compound 50 yielded the anti-inflammatory agent 5172.

In summary, we have developed a phosphorus-assisted deoxygenative arylation of saccharides, enabling direct synthesis of a diverse range of aryl C-glycosides. Notably, the key β-scission step is initiated by a Zn/I2 system. The glycosyl donors used in this reaction are bench-stable, mostly commercially available. The reaction features a broad substrate scope, is applicable to late-stage functionalization of bioactive compounds, and allows for the construction of alkyl C-glycoside and aryl C6-glycoside. The synthetic utility of this strategy has been further demonstrated through gram-scale synthesis and the preparation of pharmaceutically relevant C-glycosides. Mechanistic insights, supported by experimental studies and DFT calculations, provide a strong foundation for the proposed reaction pathway. From a practical standpoint, this method is poised to play an important role in various research fields involving synthetic C-glycosides, including molecular biology and medicinal chemistry.

Methods

General procedure for the preparation of 3-46

A 4 mL vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with saccharide 1 (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), aryl iodide 2 (0.2 mmol, 2.0 equiv.), NiCl2.dtbbpy catalyst (0.01 mmol, 10 mol%), and DMAP (0.01 mmol, 10 mol%). The vial was transferred to an Ar-filled glove box. Subsequently, ClPPh2 (0.11 mmol, 1.1 equiv.), Cy2NH (0.12 mmol, 1.2 equiv.), and 1,4-dioxane (0.25 mL, 0.4 M) were added to the mixture, which was stirred at 1000 rpm for 20 min. Next, Zn (0.3 mmol, 3.0 equiv.) and I2 (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) were added. The vial was sealed with a PTFE cap and wrapped with a thin layer of parafilm. The vial was then transferred out of the glovebox, and the reaction mixture was allowed to stir vigorously at room temperature for 18 h. When the reaction was complete, the reaction mixture was filtered and then concentrated in vacuo. The crude material was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to afford the corresponding product.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information file. For the experimental procedures and data of NMR analysis, see Supplementary Information. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Levy, D. E. & Tang, C. The Chemistry of C-glycosides (Elsevier, 1995).

Yang, Y. & Yu, B. Recent advances in the chemical synthesis of C-glycosides. Chem. Rev. 117, 12281–12356 (2017).

Parida, S. P. et al. Recent advances on synthesis of C-glycosides. Carbohydr. Res. 530, 108856 (2023).

Compain, P. & Martin, O. R. Carbohydrate mimetics-based glycosyltransferase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 9, 3077–3092 (2001).

Zou, W. C-glycosides and aza-C-glycosides as potential glycosidase and glycosyltransferase inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 5, 1363–1391 (2005).

Tamburrini, A., Colombo, C. & Bernardi, A. Design and synthesis of glycomimetics: recent advances. Med. Res. Rev. 40, 495–531 (2020).

Leusmann, S., Ménová, P., Shanin, E., Titz, A. & Rademacher, C. Glycomimetics for the inhibition and modulation of lectins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 3663–3740 (2023).

Bililign, T., Griffith, B. R. & Thorson, J. S. Structure, activity, synthesis and biosynthesis of aryl-C-glycosides. Nat. Prod. Rep. 22, 742–760 (2005).

Lee, D. Y. W. & He, M. Recent advances in aryl C-glycoside synthesis. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 5, 1333–1350 (2005).

Liu, C.-F. Recent advances on natural aryl-C-glycoside scaffolds: structure, bioactivities, and synthesis-a comprehensive review. Molecules 27, 7439 (2022).

Edward, C. C. & Robert, R. H. SGLT2 inhibition–a novel strategy for diabetes treatment. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 551–559 (2010).

Chen, W., Zhang, H., Wang, J. & Hu, X. Flavonoid glycosides from the bulbs of Lilium speciosum var. gloriosoides and their potential antiviral activity against RSV. Chem. Nat. Compd. 55, 461–464 (2019).

Franchetti, P. et al. Furanfurin and thiophenfurin: two novel tiazofurin analogs. Synthesis, structure, antitumor activity, and interactions with inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase. J. Med. Chem. 38, 3829–3837 (1995).

Zhang, C. et al. Direct synthesis of unprotected aryl C-glycosides by photoredox Ni-catalysed cross-coupling. Nat. Synth. 2, 251–260 (2023).

Wang, Q., Lee, B. C., Song, N. & Koh, M. J. Stereoselective C-aryl glycosylation by catalytic cross-coupling of heteroaryl glycosyl sulfones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202301081 (2023).

Liu, J., Lei, C. & Gong, H. Nickel-catalyzed reductive coupling of glucosyl halides with aryl/vinyl halides enabling β-selective preparation of C-aryl/vinyl glucosides. Sci. China Chem. 62, 1492–1496 (2019).

Liu, J. & Gong, H. Stereoselective preparation of α-C-vinyl/aryl glycosides via nickel-catalyzed reductive coupling of glycosyl halides with vinyl and aryl halides. Org. Lett. 20, 7991–7995 (2018).

Gong, H. & Gagné, M. R. Diastereoselective Ni-catalyzed Negishi cross-coupling approach to saturated, fully oxygenated C-alkyl and C-aryl glycosides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 12177–12183 (2008).

Nicolas, L. et al. Diastereoselective metal-catalyzed synthesis of C-aryl and C-vinyl glycosides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 11101–11104 (2012).

Adak, L. et al. Synthesis of aryl C-glycosides via iron-catalyzed cross coupling of halosugars: Stereoselective anomeric arylation of glycosyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10693–10701 (2017).

Wu, J., Purushothaman, R., Kallert, F., Homölle, S. L. & Ackermann, L. Electrochemical glycosylation via halogen-atom-transfer for C-glycoside assembly. ACS Catal. 14, 11532–11544 (2024).

Wu, J. et al. Remote C−H glycosylation by ruthenium(II) catalysis: modular assembly of meta-C-aryl glycosides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208620 (2022).

Mou, Z.-D., Wang, J.-X. & Niu, D. W. Stereoselective preparation of C-aryl glycosides via visible-light-induced nickel-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling of glycosyl chlorides and aryl bromides. Adv. Synth. Catal. 363, 3025–3029 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Iron-catalysed reductive cross-coupling of glycosyl radicals for the stereoselective synthesis of C-glycosides. Nat. Synth. 1, 235–244 (2022).

Mao, R. et al. Synthesis of C-mannosylated glycopeptides enabled by Ni-catalyzed photoreductive cross-coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 12699–12707 (2021).

Gou, X. et al. Ruthenium-catalyzed stereo- and site-selective ortho- and meta-C−H glycosylation and mechanistic studies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205656 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Chemoselective and diastereoselective synthesis of C-aryl nucleoside analogues by nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of furanosyl acetates with aryl iodides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202110391 (2022).

Miller, E. M. & Walczak, M. A. Light-mediated cross-coupling of anomeric trifluoroborates. Org. Lett. 23, 4289–4293 (2021).

Takeda, D. et al. β-glycosyl trifluoroborates as precursors for direct α-C-glycosylation: synthesis of 2-deoxy-α-C-glycosides. Org. Lett. 23, 1940–1944 (2021).

Wei, Y., Ben-Zvi, B. & Diao, T. Diastereoselective synthesis of aryl C-glycosides from glycosyl esters via C−O bond homolysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9433–9438 (2021).

Dumoulin, A., Matsui, J. K., Gutierrez-Bonet, A. & Molander, G. A. Synthesis of non-classical arylated C-saccharides through nickel/photoredox dual catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6614–6618 (2018).

Wang, Q., Duan, J., Tang, P., Chen, G. & He, G. Synthesis of non-classical heteroaryl C-glycosides via Minisci-type alkylation of N-heteroarenes with 4-glycosyl-dihydropyridines. Sci. China Chem. 63, 1613–1618 (2020).

Xu, S. et al. Stereoselective and site-divergent synthesis of C-glycosides. Nat. Chem. 16, 2054–2065 (2024).

Dong, Z. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Metallaphotoredox-enabled deoxygenative arylation of alcohols. Nature 598, 451–456 (2021).

Gan, Y. et al. Zirconaaziridine-mediated Ni-catalyzed diastereoselective C(sp2)-glycosylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 16753–16763 (2024).

Ma, Y. et al. Highly stereoselective synthesis of aryl/heteroaryl-C-nucleosides via the merger of photoredox and nickel catalysis. Chem. Commun. 55, 14657–14660 (2019).

Xiong, W. et al. Ni-Catalyzed deoxygenative cross-coupling of alcohols with aryl chlorides via an organic photoredox process. ACS Catal. 14, 14089–14097 (2024).

Murakami, M. & Ishida, N. β-Scission of alkoxy radicals in synthetic transformations. Chem. Lett. 46, 1692–1700 (2017).

Chen, R. et al. Alcohol–alcohol cross-coupling enabled by SH2 radical sorting. Science 383, 1350–1357 (2024).

Wang, J. Z., Lyon, W. L. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Alkene dialkylation by triple radical sorting. Nature 628, 104–109 (2024).

Liu, D.-P., Zhang, X.-S., Liu, S. & Hu, X.-G. Dehydroxylative radical N-glycosylation of heterocycles with 1-hydroxycarbohydrates enabled by copper metallaphotoredox catalysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 3401 (2024).

Wang, L., Li, Z., Zhou, Y. & Zhu, J. Nickel-catalyzed deoxygenative amidation of alcohols with carbamoyl chlorides. Org. Lett. 26, 2297–2302 (2024).

Cavazzoli, G. et al. Synthesis of α-arylglycosides by Ni-photoredox arylation of sugars with an organic photocatalyst. ChemCatChem 17, e202500042 (2025).

Bentrude, W. G., Hansen, E. R., Khan, W. A. & Rogers, P. E. α vs. β Scission in reactions of alkoxy and thiyl radicals with diethyl alkylphosphonites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 94, 2867–2868 (2002).

Bentrude, W. G. Phosphoranyl radicals: their structure, formation, and reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 15, 117–125 (2002).

Zhang, L. & Koreeda, M. Radical deoxygenation of hydroxyl groups via phosphites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 13190–13191 (2004).

Stache, E. E., Ertel, A. B., Tomislav, R. & Doyle, A. G. Generation of phosphoranyl radicals via photoredox catalysis enables voltage-independent activation of strong C–O bonds. ACS Catal. 8, 11134–11139 (2018).

Rossi-Ashton, J. A., Clarke, A. K., Unsworth, W. P. & Taylor, R. J. K. Phosphoranyl radical fragmentation reactions driven by photoredox catalysis. ACS Catal. 10, 7250–7261 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Dehydroxylative arylation of alcohols via paired electrolysis. Org. Lett. 24, 7476–7481 (2022).

Xie, D.-T. et al. Regioselective fluoroalkylphosphorylation of unactivated alkenes by radical-mediated alkoxyphosphine rearrangement. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202203398 (2022).

Pagire, S. K., Shu, C., Reich, D., Noble, A. & Aggarwal, V. K. Convergent deboronative and decarboxylative phosphonylation enabled by the phosphite radical trap “BecaP”. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 18649–18657 (2023).

Xu, W., Fan, C., Hu, X. & Xu, T. Deoxygenative transformation of alcohols via phosphoranyl radical from exogenous radical addition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401575 (2024).

Chai, L. et al. Radical Arbuzov reaction. CCS Chem. 6, 1312–1323 (2024).

Maeda, H., Matsumoto, S., Koide, T. & Ohmori, H. Dehydroxy substitution reactions of the anomeric hydroxy groups in some protected sugars initiated by anodic oxidation of triphenylphosphine. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 46, 939–943 (1998).

Su, Z.-M., Deng, R. & Stahl, S. S. Zinc and manganese redox potentials in organic solvents and their influence on nickel catalysed cross-electrophile coupling. Nat. Chem. 16, 2036–2043 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Photo-medicated synthesis of 1,2-dideoxy-2-phosphinylated carbohydrates from glycals: the reduction of glycosyl radicals to glycosyl anions. Green. Chem. 24, 8280–8291 (2022).

Mazkas, D., Skrydstrup, T., Doumeix, O. & Beau, J. M. Samarium iodide induced intramolecular C-glycoside formation: efficient radical formation in the absence of an additive. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 33, 1383–1386 (1994).

Till, N. A., Tian, L., Dong, Z., Scholes, G. D. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Mechanistic analysis of metallaphotoredox C-N coupling: photocatalysis initiates and perpetuates Ni(I)/Ni(III) coupling activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 15830–15841 (2020).

Tsou, T. T. & Kochi, J. K. Mechanism of oxidative addition. Reaction of nickel(0) complexes with aromatic halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 6319–6332 (1979).

Calvaresi, E. C. & Hergenrother, P. J. Glucose conjugation for the specific targeting and treatment of cancer. Chem. Sci. 4, 2319–2333 (2013).

Eccles, R. Menthol and related cooling compounds. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 46, 618–630 (1994).

Chen, T. C., Fonseca, C. O. & Schönthal, A. H. Preclinical development and clinical use of perillyl alcohol for chemoprevention and cancer therapy. Am. J. Cancer Res. 5, 1580–1593 (2015).

Wang, S. et al. A clinical and mechanistic study of topical borneol-induced analgesia. EMBO Mol. Med. 9, 802–815 (2017).

Sanders, D. A. R. et al. UDP-galactopyranose mutase has a novel structure and mechanism. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 858–863 (2001).

Connolly, G. P. & Duley, J. A. Uridine and its nucleotides: biological actions, therapeutic potential. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 20, 218–226 (1999).

Tabas, I. Cholesterol in health and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 583–590 (2002).

De Nicolai, P. A smelling trip into the past: the influence of synthetic materials on the history of perfumery. Chem. Biodivers. 5, 1137–1146 (2008).

Forsman, J. P. & Lipkin, D. The reactions of phenyl esters of phosphorous acid with iodine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 75, 3145–3148 (1953).

Stowell, J. K. & Widlanski, T. S. A new method for the phosphorylation of alcohols and phenols. Tetrahedron Lett. 36, 1825–1826 (1995).

Cremer, S. E. et al. Substituted 1-chlorophosphetanium salts. Synthesis, stereochemistry, and reactions. J. Org. Chem. 38, 3199–3207 (1973).

Temburnikar, K. & Seley-Radtke, K. L. Recent advances in synthetic approaches for medicinal chemistry of C-nucleosides. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 14, 772–785 (2018).

Jiang, Y., Wang, Q., Zhang, X. & Koh, M. J. Synthesis of C-glycosides by Ti-catalyzed stereoselective glycosyl radical functionalization. Chem 7, 3377–3392 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding supports from Singapore National Research Foundation under its NRF Competitive Research Program (NRF-CRP22-2019-0002), Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its MOE AcRF Tier 1 Award (RG84/22, RG70/21, RG11/24) and MOE AcRF Tier 2 Award (MOE-T2EP10222-0006), a Chair Professorship Grant, and Nanyang Technological University; National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1700300); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A20201, 22071036), Frontiers Science Center for Asymmetric Synthesis and Medicinal Molecules, Department of Education, Guizhou Province [Qianjiaohe KY Number (2020)004], the Natural Science Foundation of Guizhou University [Guida Tegang Hezi (2023)23], the Central Government Guides Local Science and Technology Development Fund Projects [Qiankehezhongyindi (2024)007, (2023)001], Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities of China (111 Program, D20023) at Guizhou University, and Guizhou University (China).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.-Y.Y. performed methodology development, scope evaluation, and synthetic application. S.H. conducted DFT calculations. X.-Y.Y. and S.H. wrote the initial draft and provided constructive advice. S.G., G.W., and W.-X.L. contributed to discussions and manuscript preparation. Y.R.C. supervised the research and revised the manuscript with comments from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, XY., Huang, S., Guo, S. et al. Direct deoxygenative arylation of saccharides via phosphorus-assisted C−OH bond activation. Nat Commun 17, 380 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67061-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67061-4