Abstract

Based on preclinical studies showing synergism with simultaneous inhibition of the estrogen receptor (ER), CDK4/6 and PI3K pathways and based on window of opportunity studies showing that metformin suppresses PI3K/mTOR signaling in endometrial cancer (EC), we conduct a non-randomized phase 2 study of letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin in ER positive endometrioid EC (NCT03675893). Primary objectives include objective response rate (ORR) and rate of progression-free survival (PFS) at 6 months (PFS6) while secondary objectives include PFS, overall survival, duration of response and toxicity. Twenty-five patients initiate protocol therapy [letrozole 2.5 mg orally (PO) once a day (qd), abemaciclib 150 mg PO twice a day (bid) and metformin 500 mg PO qd]. ORR is 32% (3 complete and 5 partial responses, 95% CI 14.9%-53.5%), Kaplan Meier estimate of PFS6 is 69.8% (95% CI 46.9%-84.3%) and median PFS is 19.4 months (95% CI 5.7 months–not estimable). No patients discontinue therapy because of toxicity. There are no objective responses among TP53 mutated ECs and among NSMP (no specific molecular profile) tumors with RB1 or CCNE1 alterations; CTNNB1 mutations correlate with clinical benefit. Pharmacokinetic analyses demonstrate that administration of letrozole and abemaciclib with metformin result in a more than 3-fold increase in metformin exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although combined hormonal therapy and CDK4/6 inhibition has demonstrated promising activity in ER positive EC1,2,3,4, denovo and acquired resistance remain a challenge. Several lines of evidence indicate that activation of the PI3K pathway promotes resistance to hormonal therapy5,6,7 and is a mechanism of adaptive response to CDK4/6 inhibition8. Serial circulating tumor (ct) DNA sequencing in our previous letrozole/abemaciclib study in EC9 demonstrated frequent, acquired, mutually exclusive, PI3K pathway alterations at the time of progression suggesting that there is a strong selective pressure to activate the PI3K pathway upon exposure to combined aromatase and CDK4/6 inhibition. Preclinical studies have demonstrated synergism with simultaneous inhibition of the PI3K, CDK4/6, and estrogen receptor (ER) pathways8,10 and this concept has been successfully applied in breast cancer with the FDA approval of the alpha-specific PI3K inhibitor inavolisib in combination with CDK4/6 inhibitor (CDK4/6i) palbociclib and hormonal therapy11. Taken together, there is compelling rationale for combinatorial strategies targeting ER, CDK4/6 and PI3K pathways in EC.

Metformin inhibits PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling both directly and indirectly. Directly, metformin inhibits mitochondrial adenosine-5’-triphosphate (ATP) synthesis, resulting in induction of liver kinase B1 (LKB1)-mediated activation of AMPK (5’ AMP-activated protein kinase) and inhibition of mTOR signaling12,13,14,15. Metformin also inhibits mTOR signaling by reducing AKT activation via AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of IRS-114,16. Indirectly, metformin decreases circulating insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels resulting in suppression of insulin receptor and IGF-1 receptor signaling and inhibition of downstream PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling17,18. In two window-of-opportunity (WOO) studies in women with newly diagnosed endometrioid EC, administration of metformin 850 mg orally daily prior to surgical staging significantly decreased serum IGF-1 and insulin levels and significantly decreased phosphorylation of AKT and downstream targets of the mTOR pathway, including S6RP and 4E-BP1 in posttreatment tumor samples19,20. Preclinical studies have demonstrated synergism between metformin and the CDK4/6i abemaciclib that is mediated by mTOR inhibition, and results of a genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 loss-of function screen have shown that loss of CDK4 and CDK6 genes sensitizes cells to metformin therapy21.

Based on these considerations, we hypothesized that inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling using metformin may enhance the activity of combined hormonal therapy and CDK4/6 inhibition in EC. Here, we report the results of a non-randomized phase 2 study of letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin in recurrent ER positive endometrioid EC which showed promising and durable activity in this setting.

Results

Patients

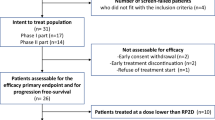

Twenty-five patients were enrolled and initiated protocol therapy (Fig. 1). All 25 patients tolerated the 1-week metformin monotherapy lead-in (metformin 500 mg orally once daily) and proceeded with letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin protocol therapy. The starting dose level 0 (DL0) of the safety lead-in was deemed safe (none of the 6 participants experienced any DLTs) and thus the DL0 of letrozole 2.5 mg once daily, abemaciclib 150 mg twice daily and metformin 500 mg once daily was administered to all patients.

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Eighteen (72%) patients had received prior hormonal therapy and the median number of prior lines of systemic therapy was 2. At the data cutoff date (10/17/2024), median follow-up was 18.7 months (95% CI: 15.3–24.4).

Antitumor activity

Of the 25 patients who initiated protocol therapy, there were 8 objective responses: 3 (12%) complete responses (CR) and 5 (20%) partial responses (PR), for an ORR of 32% (95% CI, 14.9-53.5), Fig. 2A, B. Of the 3 patients with CR, one patient had an unconfirmed CR (CR was confirmed after the data cut-off) but confirmed PR. Of the 5 patients with PR, one patient had an unconfirmed PR. Median duration of response (DOR) could not be estimated because only 2 responders developed progressive disease as of the data cutoff date.

The first patient with CR had a grade 1 endometrioid, NSMP, PIK3CA, PTEN and catenin beta-1 (CTNNB1) mutated tumor, had previously received radiation therapy and chemotherapy with carboplatin/paclitaxel and had multiple metastatic lung nodules and axillary lymph node disease prior to enrollment to the study. The second patient with CR had a grade 2, endometrioid, PgR negative, NSMP, PIK3CA mutated tumor with multiple pleural nodules, abdominal/peritoneal disease and an enlarged periportal lymph nodule at baseline, and the third patient with CR had a grade 1 endometrioid, NSMP, AKT1 and CTNNB1 mutated tumor, had previously received chemotherapy with carboplatin/paclitaxel and had multiple abdominal wall nodules and an enlarged iliac lymph node prior to enrollment in the study.

Sixteen (64%) patients exhibited stable disease (SD) as best response. Of these, 7 patients had SD for at least 6 months while the remaining 9 patients experienced a best response of SD that lasted <6 months. Overall, 15 patients met at least one of the two co-primary objectives of ORR and PFS6 and were defined as having derived clinical benefit from this regimen (CBR: 60%, 95% CI, 38.7%-78.9%). CBR was observed in 9 (69%) of 13 FIGO grade 1, 6 (75%) of 8 FIGO grade 2 and 0 of 4 FIGO grade 3 tumors. Eleven (61%) of the 18 patients who had received prior hormonal therapy and 4 (57%) of 7 patients who had not received prior hormonal therapy derived clinical benefit from letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin.

Median PFS was 19.4 months (95% CI 5.7–not estimable) while Kaplan Meier estimate of PFS at 6 months was 69.8% (95% CI 46.9–84.3%), Fig. 3A. At the time of data cut-off, 4 patients had died; median OS was not estimable, Fig. 3A.

Safety

The top 10 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) ranked by frequency of Grade 3 (G3) toxicity are presented in Table 2. Most common G3 TRAEs were decreased neutrophil count, fatigue, anemia and increased aspartate aminotransferase. Nineteen patients had ≥1 dose reduction of abemaciclib. No patients discontinued therapy because of toxicity.

Biomarker analyses

Molecular profiling via our Oncopanel assay22,23,24 revealed no polymerase epsilon (POLE) mutated and no mismatch-repair deficient (MMRD) tumors. There were 21 NSMP (no specific molecular profile) and 4 TP53 mutated tumors (TP53 mutation status was determined only by Oncopanel). There were no objective responses in the TP53 mutated tumors. Of the 21 patients with NSMP tumors, 8 (38.1%) achieved an objective response and 14 (66.7%) clinical benefit.

Five patients with NSMP tumors harbored retinoblastoma 1 (RB1) or cyclin E1 (CCNE1) alterations; such alterations have been previously associated with resistance to CDK4/6i in breast cancer8,25. None of the patients with NSMP tumors that harbored RB1 or CCNE1 alterations exhibited objective response. PFS of patients with these tumors was significantly worse than that of patients with NSMP tumors without RB1/CCNE1 alterations (p < 0.001, Fig. 3B). Overall, there was significant difference in PFS among TP53 mutated tumors, NSMP tumors with RB1/CCNE1 alterations, and NSMP tumors without RB1/CCNE1 alterations (p = 0.005, Fig. 3C).

There was only one patient with PgR negative tumor (<1% of tumor cell nuclei being immunoreactive by IHC); this patient exhibited an objective response. There was no statistically significant correlation observed between PgR positive status and clinical outcome (regardless of the cut-off for PgR positivity used). Presence of CTNNB1 mutations correlated with clinical benefit (p = 0.018). No other significant correlations with genomic alterations were observed (Table 3).

Metformin PKs

PK analyses were performed on blood samples from the 6 participants in the safety lead-in at DL0 (letrozole 2.5 mg once daily, abemaciclib 150 mg twice daily and metformin 500 mg once daily). Geometric mean and standard deviation of concentrations by time point are shown in Table 4. Individual PK profiles, along with geometric mean and standard deviation at each time point for C1D1 and C1D8, are depicted in Fig. 4A. Fold increase in metformin steady-state trough concentration (Cmin) relative to predose concentration on C1D1, were calculated and are presented in Fig. 4B.

A Metformin plasma concentrations in 6 patients receiving combination of metformin + abemaciclib + letrozole on C1D1 (left) and on C1D8 (right); individual patients (dashed lines) and geometric mean and SD (solid circles and error bars). B Metformin steady state trough concentration fold increase from baseline upon initiation of abemaciclib + letrozole dosing. Data are presented as individual patients (dotted lines) and geometric mean values +/- SD (solid lines).

Observed metformin exposure Table 4 in our study at 500 mg once daily exceeded that previously reported per the half-life (6–7 vs 5–6 h), and apparent clearance (25−38 vs 47−79 L/h)26. Significant difference between day 1 (initial day of combination) and day 8 (steady-state reached for the new combination) was observed for AUC but this change in AUC likely underestimates the fold change relative to metformin alone. The most appropriate impression of the impact of abemaciclib and letrozole on metformin exposure can be gleaned from the impact on Cmin concentrations. An initial 1.65-fold (day 1) and ultimately 3.2-fold increase in metformin Cmin, compared to Cmin of metformin alone, was observed after initiation of abemaciclib and letrozole. Steady-state of this drug interaction on day 8 is confirmed by the pre-dose and 24 h sample showing the same fold-increase on day 8.

Discussion

In this investigator-initiated phase 2 study, letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin met the prespecified objective response and PFS6 criteria to be considered worthy of further investigation in ER positive endometrioid EC. To our knowledge, this is the first study of combined hormonal therapy, CDK4/6 inhibition and metformin in any cancer type. Addition of metformin to letrozole/abemaciclib was feasible and demonstrated an acceptable safety profile with no new safety signals or unexpected toxicities. No patients discontinued protocol therapy because of toxicity and adverse events were comparable to those observed in our previous study of letrozole/abemaciclib in EC as well as previous studies of letrozole/abemaciclib in breast cancer27,28.

Although addition of metformin to letrozole/abemaciclib demonstrated comparable ORR (32%) to that of letrozole/abemaciclib alone (ORR 30%2), letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin induced deeper and more prolonged responses. Specifically, 3 patients achieved durable, complete responses to letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin, all ongoing and for >2 years, while there have been no complete responses reported thus far in any clinical trial of combined hormonal therapy and CDK4/6 inhibition in EC1,2,3,4. Letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin also demonstrated a median PFS of 19.4 months while the median PFS of combined hormonal therapy and CDK4/6 inhibition in EC was ~9 months (8.3 months with letrozole/palbociclib3, 9.1 months with letrozole/abemaciclib2, 9.0 months with fulvestrant/abemaciclib1 and 6.8 months with imlunestrant/abemaciclib4). However, it is important to acknowledge that direct cross-study comparisons are hindered by study specific differences in eligibility criteria (e.g., histologies allowed, ER cut-offs for eligibility, prior lines of therapy allowed), patient clinical, pathological and molecular characteristics (e.g., frequency of TP53 mutated tumors and G3 tumors and receipt of prior hormonal therapy), samples sizes, and statistical designs. In the current study, the subset of patients with TP53 mutated and FIGO G3 tumors (both 16%) was smaller than our previous letrozole/abemaciclib study (where 50% of the profiled tumors were TP53 mutated and 33% were G3, including 1 patient with serous carcinoma and 1 patient with carcinosarcoma) and the current study included a less heavily pretreated patient population (2 median lines of therapy versus 3 median lines of therapy with the letrozole/abemaciclib study). In other words, our previous letrozole/abemaciclib study enrolled a less prognostically favorable patient population, although 72% of patients in the current study had received prior hormonal therapy as opposed to only 50% in the letrozole/abemaciclib study. On the other hand, the subset of patients with TP53 mutated and FIGO G3 tumors in the current study was similar to that in the fulvestrant/abemaciclib study (18.5% TP53 mutated and 17% G3) and. only 40% patients in the fulvestrant/abemaciclib study had previously received hormonal therapy (as opposed to 72% in the current study). Of note, no hormonal therapy (with the exception of progestin analogs) was permitted in the letrozole/palbociclib study and the cut-off for ER positivity was 10% as opposed to only 1% in all the abemaciclib studies; no molecular profiling was reported in the letrozole/palbociclib study so the frequency of TP53 mutated tumors in that study is unknown. Taken together, acknowledging that our previous letrozole/abemaciclib included a less favorable population while the fulvestrant/abemaciclib and letrozole/palbociclib studies included at least similar or more favorable patient populations, the median PFS of 19.4 months observed here with letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin (as compared to the median PFS of ~9 months with the other CDK4/6i studies) suggests that letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin may be an effective alternative endocrine regimen for recurrent endometrioid EC and warrants further evaluation in a randomized phase 2 or 3 clinical trial. Such a study would randomize patients with ER positive, TP53 wildtype endometrioid endometrial cancer between letrozole/abemaciclib versus letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin.

The prolongation and deepening of responses with addition of metformin to letrozole/abemaciclib may be related to metformin’s ability to suppress PI3K signaling both directly and indirectly. Given that activation of the PI3K pathway promotes resistance to hormonal therapy5,6,7 and is a mechanism of adaptive response and resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition8, suppression of PI3K signaling by metformin may have delayed or prevented resistance to letrozole/abemaciclib in a subset of patients, thereby leading to deeper and more prolonged responses. In this regard, PK analyses indicated that metformin plasma concentrations when combined with letrozole/abemaciclib were sufficient to facilitate PI3K pathway inhibition based on previous metformin WOO studies in patients with endometrioid EC19,20. There is a clinically significant drug-drug interaction between abemaciclib and metformin whereby abemaciclib and its major metabolites inhibit the renal transporters OCT2 (organic cation transporter 2), multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE)1, and MATE2-K that are involved in the active secretion of metformin and thus increase metformin exposure29. Based on this consideration, we evaluated a lower (500 mg once daily) dose of metformin in this study compared to the dose (850 mg once daily) used in previous WOO studies in EC. Our PK analyses suggested >3-fold increase in metformin exposure (when combined with letrozole/abemaciclib) suggesting that a significant drug interaction had indeed occurred, likely explained by the known increase of metformin exposure due to abemaciclib mediated inhibition of OCT2, MATE1, and MATE2-K, although an interaction between letrozole and metformin cannot be excluded. This interaction of metformin with letrozole/abemaciclib was not expected to be associated with a clinically relevant increase in metformin toxicity because our day 8 average concentration of 842 µg/L was well within the recommended maximum concentration of 2500 µg/L for safe clinical use26. Nonetheless, the magnitude of the interaction indicated that metformin exposure in our study readily exceeded that of 850 mg daily, the dose associated with evidence of AMPK/mTOR inhibition in the two previous WOO studies19,20.

Although TP53 mutation status (indicative of the CN-high/serous-like subgroup of EC) correlated with lack of response in our previous letrozole/abemaciclib study, we allowed inclusion of patients with TP53 mutated tumors in this study because it was possible that addition of metformin to letrozole/abemaciclib could have been able to overcome the denovo resistance of TP53 mutated tumors to CDK4/6 inhibitors. To that end, metformin had been previously reported to exert anti-tumor activity in endometrial cancer models regardless of TP53 mutation status30. Nonetheless, the current study demonstrated that metformin could not overcome denovo resistance of TP53 mutated tumors to CDK4/6 inhibitors which is consistent with other preclinical studies demonstrating that the antiproliferative and antitumor activities of metformin depend on a normal, functional p53 protein31,32,33.

All tumors with objective responses belonged to the NSMP molecular subgroup; interestingly, 5 of the 21 patients with NSMP tumors harbored RB1 and CCNE1 alterations which may facilitate G1- > S phase transition without dependence on CDK4/6 and thus confer resistance to CDK4/6i. RB loss is a well-established mechanism of intrinsic and acquired resistance to CDK4/6i while CCNE1 amplification or overexpression can facilitate RB phosphorylation (via the cyclin E1/CDK2 complex) and promote G1 to S phase transition via an alternative way than the cyclin D1/CDK4/6 complex, thus bypassing CDK4/6i8,25. None of the 5 NSMP tumors with RB1/CCNE1 alterations derived clinical benefit from letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin and like TP53 mutations, RB1 and CCNE1 alterations may be negative predictive biomarkers of response to this regimen in EC.

Presence of CTNNB1 mutations correlated with clinical benefit to letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin; this was significant even when TP53 mutated tumors were excluded suggesting that presence of CTNNB1 mutations may be a predictive biomarker of response above and beyond their mutual exclusivity with TP53 mutations in EC. Of note, 2 of the 3 patients with durable complete responses to letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin in this study harbored CTNNB1 mutations; given that metformin suppresses β-catenin-dependent Wnt signaling and reduces the cross-talk between the β-catenin/Wnt and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathways, addition of metformin may have led to the durable and deep responses particularly in CTNNB1 mutated tumors34.

Finally, all 4 patients with ESR1 mutated ECs derived clinical benefit from letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin (with one objective response). ESR1 alterations have been shown to be present in up to 20-40% of endocrine resistant breast cancers35 and were identified via ctDNA sequencing in 4 patients with EC at the time of progression through our previous letrozole/abemaciclib study36. It is impossible to know whether abemaciclib or metformin or both contributed to overcoming ESR1-mediated resistance to aromatase inhibitor (letrozole) therapy in these 4 patients, but this observation suggests that letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin exhibits activity against ESR1 mutated tumors.

We acknowledge certain limitations of our study. The contribution of addition of metformin to letrozole/abemaciclib can be unequivocally determined only via a randomized clinical trial of letrozole/abemaciclib vs letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin as described above. Only 2 patients enrolled in our study were Black or African American and only 1 patient was Latino or Hispanic highlighting the need for better representation of African American and Hispanic patients in future studies of EC, especially in the context of the notable racial disparity in EC mortality. Our correlative analysis, which demonstrated several mechanistically relevant candidate predictors of response (CTNNB1 mutations) and absence of response (TP53 mutations and CCNE1 and RB1 alterations), requires independent validation in larger cohorts of patients. Notwithstanding these limitations, our study demonstrated that addition of an oral and inexpensive drug like metformin to letrozole/abemaciclib was feasible and tolerable, and demonstrated promising and durable activity in ER positive EC to be considered worthy of further evaluation in a randomized trial.

Methods

Study design

This investigator-initiated study is open at three institutions (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital) and was approved by the Dana Farber Harvard Cancer Center IRB (NCT03675893). All procedures involving human participants were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from patients or guardians before enrollment in the study. There was no compensation for study participation. The study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, which also provided abemaciclib.

Primary objective was to evaluate the activity of letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin as determined by the frequency of patients who had objective response (OR) by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 or survived progression-free for at least 6 months (PFS6) after initiating therapy. Secondary endpoints included duration of progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), duration of response (DOR) and toxicity; all secondary endpoints were reported here. Exploratory endpoints (all prespecified in the protocol) included correlation of baseline genomic alterations with response to protocol therapy and determination of metformin PK on protocol therapy.

All participants initially received metformin alone, 500 mg orally, once daily for 1 week. Participants who tolerated this 1-week metformin lead-in, were allowed to proceed with letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin therapy. To confirm the safety of the triplet combination, a safety lead-in was conducted whereby the first 6 participants proceeded with letrozole 2.5 mg once daily, abemaciclib 150 mg twice daily and metformin 500 mg once daily (Dose Level 0/DL0). If ≥2 of the 6 participants experienced a dose limiting toxicity (DLT), then metformin would be de-escalated to 500 mg every other day (DL-1). Protocol treatment was administered on an outpatient basis and continued until progression or unacceptable toxicity in 28 day treatment cycles. To assess the potential impact of metformin combination, glucose levels were formally evaluated in all subjects every week during cycles 0 and 1, every other week during cycle 2, and every day 1 of each cycle starting on Cycle 3. Subjects were not tracking their blood sugar as part of the study protocol. Study protocol is included in the supplement.

Sex, ethnicity and race were not formally/prospectively collected from patients as part of their enrollment in the clinical trial. This information was self-reported by patients and captured as per standard processes upon new patient registration in each institution.

Eligibility

Eligible participants had pathologically confirmed EC that was recurrent or metastatic and/or resistant to standard therapies. Patients were required to have histologically confirmed either i) endometrioid EC or ii) carcinosarcoma with an endometrioid epithelial component and were required to have ER-positive disease, defined as ≥1% of tumor cell nuclei being immunoreactive by immunohistochemistry. The eligibility cutoff for ER positivity of ≥1% was selected because this is recommended by the College of American Pathologists’ guideline for ER and PR IHC in EC37 and has been used previous studies of combinations of hormonal therapy with CDK4/6 inhibitors in EC1,2,4. Other eligibility criteria included measurable disease, no limit to the number of prior therapies, ECOG performance status of ≤1, availability of archival formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue and normal organ and marrow function. Previous hormonal therapy, including prior letrozole, was allowed. Key exclusion criteria included current treatment with metformin, prior CDK4/6i treatment, known active brain metastases, and concomitant therapy with moderate/strong CYP3A4 inducers, or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors.

Molecular profiling and PgR expression

Molecular profiling was performed using Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s OncoPanel targeted panel next-generation sequencing (NGS) assay on FFPE specimens (blocks or unstained slides) from enrolled patients; OncoPanel surveys exonic DNA sequences of 447 genes, as previously described22,23,24. Progesterone receptor expression was assessed via IHC (PR, clone PgR636, 1:200 dilution, Dako, Carpinteria, CA) on FFPE specimens.

Metformin Pharmacokinetics (PKs)

For metformin PKs, EDTA plasma was collected from subjects participating in the safety lead-in after initiation of abemaciclib and letrozole on cycle 1 day 1 (C1D1 predose, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours(h)), and cycle 1 day 8 (C1D8 predose, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 h). Each blood sample was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm, and plasma was stored at -70 °C until analysis by a validated LC-MS/MS assay utilizing a [D6]-metformin internal standard covering the range of 39−7800 ng/mL. Plasma PK data were analyzed with WinNonlin (Certara, Princeton, NJ). Statistical testing was performed with RStudio 2024.12.1.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical considerations were developed for co-primary objectives to evaluate the ORR and rate of PFS at 6 months (PFS6). A maximum of 25 evaluable participants would be accrued; if ≥6 patients exhibited an objective response, then the lower bound of the binomial 90% confidence interval would exceed 10%, and letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin would be considered worthy of further evaluation. Alternatively, if ≥9 patients were alive and progression-free after 6 months, then the lower bound of the binomial 90% confidence interval would exceed 20% and letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin would be considered worthy of further evaluation. If <6 patients exhibited an objective response and <9 patients were alive and progression-free at 6 months, letrozole/abemaciclib/metformin would not be considered worthy of further evaluation.

Patient characteristics, objective response rate, clinical benefit rate (CBR, defined as meeting at least one of the two co-primary endpoints of objective response or progression free ≥6 months after initiation of therapy), and treatment-related toxicities were summarized by count (percentage) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for ORR and CBR. Time to event variables for duration of response (DOR), progression¬ free survival (PFS), PFS at 6 months (PFS6), and overall survival (OS) were summarized using the Kaplan–Meier method with 95% CI. Correlations between biomarkers and clinical activity were evaluated by Fisher’s exact test (2-sided) for ORR or CBR and the log¬-rank test (2-sided) for PFS or OS.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All research targeted next generation sequencing data have been deposited in the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), dataset: EGAD50000001711, Study: EGAS50000001202. Data are now available for general research use upon approval; data can be requested at: https://ega-archive.org/datasets/EGAD50000001711. Reason for access restrictions is our Institutional Review Board (IRB) policy. The above link will notify data owners (Dr. Konstantinopoulos) of the request and the expected timeframe for response to access requests is <5 business days. Once access has been granted, the data will be available without restriction for general research use and indefinitely. The study protocol and the statistical analysis plan are available in the Supplementary Information file as a Supplementary Note. The remaining data are available within the Article, or Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Green, A. et al. A phase II study of fulvestrant and abemaciclib in hormone receptor positive advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 5511–5511 (2024).

Konstantinopoulos, P. A. et al. A phase II, two-stage study of letrozole and abemaciclib in estrogen receptor-positive recurrent endometrial cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 599–608 (2023).

Mirza, M. R. et al. Palbociclib plus letrozole in estrogen receptor-positive advanced/recurrent endometrial cancer: Double-blind placebo-controlled randomized phase II ENGOT-EN3/PALEO trial. Gynecol. Oncol. 192, 128–136 (2025).

Yonemori, K. et al. Imlunestrant, an oral selective estrogen receptor degrader, as monotherapy and combined with abemaciclib, in recurrent/advanced ER-positive endometrioid endometrial cancer: results from the phase 1a/1b EMBER study. Gynecol. Oncol. 191, 172–181 (2024).

Toska, E. et al. PI3K inhibition activates SGK1 via a feedback loop to promote chromatin-based regulation of ER-dependent gene expression. Cell Rep. 27, 294–306 e295 (2019).

Vasan, N., Toska, E. & Scaltriti, M. Overview of the relevance of PI3K pathway in HR-positive breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 30, x3–x11 (2019).

Yang, W. et al. Estrogen receptor alpha drives mTORC1 inhibitor-induced feedback activation of PI3K/AKT in ER+ breast cancer. Oncotarget 9, 8810–8822 (2018).

Herrera-Abreu, M. T. et al. Early adaptation and acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Res. 76, 2301–2313 (2016).

Konstantinopoulos, P. A. et al. Serial circulating tumor DNA sequencing to monitor response and define acquired resistance to letrozole/abemaciclib in endometrial cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 9, e2400882 (2025).

Vora, S. R. et al. CDK 4/6 inhibitors sensitize PIK3CA mutant breast cancer to PI3K inhibitors. Cancer Cell 26, 136–149 (2014).

Turner, N. C. et al. Inavolisib-based therapy in PIK3CA-mutated advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 1584–1596 (2024).

Green, A. S. et al. LKB1/AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway in hematological malignancies: from metabolism to cancer cell biology. Cell Cycle 10, 2115–2120 (2011).

Li, D. Metformin as an antitumor agent in cancer prevention and treatment. J. Diabetes 3, 320–327 (2011).

Clements, A. et al. Metformin in prostate cancer: two for the price of one. Ann. Oncol. 22, 2556–2560 (2011).

Zhou, G. et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1167–1174 (2001).

Zakikhani, M., Blouin, M. J., Piura, E. & Pollak, M. N. Metformin and rapamycin have distinct effects on the AKT pathway and proliferation in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 123, 271–279 (2010).

Bailey, C. J. & Turner, R. C. Metformin. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 574–579 (1996).

Leone, A., Di Gennaro, E., Bruzzese, F., Avallone, A. & Budillon, A. New perspective for an old antidiabetic drug: metformin as anticancer agent. Cancer Treat. Res. 159, 355–376 (2014).

Schuler, K. M. et al. Antiproliferative and metabolic effects of metformin in a preoperative window clinical trial for endometrial cancer. Cancer Med. 4, 161–173 (2015).

Soliman, P. T. et al. Prospective evaluation of the molecular effects of metformin on the endometrium in women with newly diagnosed endometrial cancer: a window of opportunity study. Gynecol. Oncol. 143, 466–471 (2016).

Ma, Y. et al. A CRISPR knockout negative screen reveals synergy between CDKs inhibitor and metformin in the treatment of human cancer in vitro and in vivo. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 5, 152 (2020).

Sholl, L. M. et al. Institutional implementation of clinical tumor profiling on an unselected cancer population. JCI Insight 1, e87062 (2016).

Wagle, N. et al. High-throughput detection of actionable genomic alterations in clinical tumor samples by targeted, massively parallel sequencing. Cancer Discov. 2, 82–93 (2012).

Garcia, E. P. et al. Validation of oncopanel: a targeted next-generation sequencing assay for the detection of somatic variants in cancer. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 141, 751–758 (2017).

Knudsen, E. S., Shapiro, G. I. & Keyomarsi, K. Selective CDK4/6 inhibitors: biologic outcomes, determinants of sensitivity, mechanisms of resistance, combinatorial approaches, and pharmacodynamic biomarkers. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 40, 115–126 (2020).

Graham, G. G. et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of metformin. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 50, 81–98 (2011).

Goetz, M. P. et al. MONARCH 3: abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 3638–3646 (2017).

Johnston, S. R. D. et al. Abemaciclib combined with endocrine therapy for the adjuvant treatment of HR+, HER2-, node-positive, high-risk, early breast cancer (monarchE). J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 3987–3998 (2020).

Chappell, J. C. et al. Abemaciclib inhibits renal tubular secretion without changing glomerular filtration rate. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 105, 1187–1195 (2019).

Sarfstein, R. et al. Metformin downregulates the insulin/IGF-I signaling pathway and inhibits different uterine serous carcinoma (USC) cells proliferation and migration in p53-dependent or -independent manners. PLoS One 8, e61537 (2013).

Chen, L., Ahmad, N. & Liu, X. Combining p53 stabilizers with metformin induces synergistic apoptosis through regulation of energy metabolism in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cell Cycle 15, 840–849 (2016).

Abu El Maaty, M. A., Strassburger, W., Qaiser, T., Dabiri, Y. & Wolfl, S. Differences in p53 status significantly influence the cellular response and cell survival to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-metformin cotreatment in colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Carcinog. 56, 2486–2498 (2017).

Tortelli, T. C. et al. Metformin-induced chemosensitization to cisplatin depends on P53 status and is inhibited by Jarid1b overexpression in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Aging 13, 21914–21940 (2021).

Park, S. Y., Kim, D. & Kee, S. H. Metformin-activated AMPK regulates beta-catenin to reduce cell proliferation in colon carcinoma RKO cells. Oncol. Lett. 17, 2695–2702 (2019).

Brett, J. O., Spring, L. M., Bardia, A. & Wander, S. A. ESR1 mutation as an emerging clinical biomarker in metastatic hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 23, 85 (2021).

Konstantinopoulos, P. A. et al. Serial circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) sequencing to monitor response and define acquired resistance to letrozole/abemaciclib in endometrial cancer (EC). J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 5592–5592 (2024).

Longacre, T. A. et al. Template for reporting results of biomarker testing of specimens from patients with carcinoma of the endometrium. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 141, 1508–1512 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients and their families for participating in the trial. This investigator-initiated study (IND holder PAK) was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, which also provided abemaciclib; Eli Lilly and Company had no role in study design, data collection and analysis or manuscript writing. We would like to acknowledge support from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and The Lewin Fund to Fight Women’s Cancers. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Erica Holdmore for depositing the sequencing data to the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA). Support was also provided in part by NCI grant P30CA006973 (JHB). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.A.K. conceived, supervised, coordinated, analyzed and interpreted all the data, wrote the manuscript and was the IND holder of the study; N.Z. and S.C. (Su-Chun Chen) performed the statistical analysis and were the lead statisticians of the study; R.T.P., S.C. (Susana Campos), C.K., A.A.W, R.P, N.H, S.B., J.F.L., M.S., P.W., C.C, U.A.M and E.K.L provided clinical data and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data; T.V.L. and J.H.B. performed the analysis and interpretation of the pharmacokinetic data; S.H. provided clinical data to the study and contributed to analysis and interpretation of data; L.K. contributed to the monitoring of the study; H.S., M.H., M.P. were Clinical Research Project Managers for the study and coordinated the processing and distribution of the clinical trial samples. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.A.K. declares consulting and/or advisory board participation for AstraZeneca, Bayer, GSK, Merck, Pfizer, BMS, Repare, IMV, Artios, Kadmon, Cardiff, Immunogen, EMD Serono, Scorpion, Schrodinger, Nimbus, Mural Oncology, unrelated to this work. R.T.P. reports personal fees for advisory boards from Aadi Bioscience, AstraZeneca, GSK Inc., ImmunoGen Inc., Merck & Co., Roche Pharma, Sutro Biopharma; Tubulis Gmbh; Serves on DSMBs for AstraZeneca, EQRx & Roche Pharma; Institutional research funding (as PI): 858 Therapeutics; Royalties from BMJ Publishing, UptoDate, Elsevier Ltd., Wolters Kluwer Health & Wiley Blackwell.; Payment for educational events: Research to Practice, ExpertConnect, ReachMD, CMEO Outfitters, unrelated to this work. J.F.L. declares consulting and/or advisory board participation for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Genentech/Roche, Genmab, GlaxoSmithKline, LoxoLilly, Merck, SystImmune, Regeneron Therapeutics, Revolution Medicine, and Zentalis Pharmaceuticals, unrelated to this work. U.A.M. declares participation in scientific advisory boards: NextCure, Abbvie, Immunogen, Profound Bio, Eisai, the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance, Tango Therapeutics, Novartis, GSK, Daiichi Sankyo, DayOne Bio, and Whitehawk Therapeutics; UAM also reports participation in a data safety-monitoring board: Mural Oncology, Macrogenics, Daiichi Sankyo, Astrazseneca and Symphogen, all unrelated to this work. E.K.L. declares advisory board participation: Aadi Biosciences, Oncusp Therapeutics, Genmab, all unrelated to this work. N.Z., T.V.L., S.C. (Susana Campos), C.K., A.A.W., R.P., N.H., S.B., S.H., H.S., L.K., M.H., M.P., M.S., P.W., S.C. (Su-Chun Cheng), C.C. and J.H.B. declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ramez Eskander, Gottfried E. Konecny and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Konstantinopoulos, P.A., Zhou, N., Penson, R.T. et al. Letrozole, abemaciclib and metformin in endometrial cancer: a non-randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Commun 17, 395 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67087-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67087-8