Abstract

Restoring retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells is crucial for treating retinal degenerative (RD) diseases, with chemical reprogramming offering a transformative, scalable solution. However, identifying key chemical compounds for generating functional RPE cells from somatic cells remains challenging. Here, we present a two-step chemical reprogramming strategy to convert fibroblasts into functional chemical induced RPE (ciRPE) cells. Leveraging the Single-Cell Reprogramming Compound Finder (scRCF), which integrates transcriptomics-guided predictions with advanced screening, we identified chemical cocktails that precisely reprogram fibroblasts through an intermediate state into ciRPE cells. These ciRPE cells closely mimic the structure and function of native RPE cells, and upon transplantation into RD rats, they seamlessly integrate into host tissue, protect photoreceptors, and restore visual function. Omics and mechanistic analyses revealed that the identified compounds synergistically activate core transcription factors, including Ascl1 and Olig2, orchestrating the reprogramming process. This study provides a scalable, non-integrative approach for generating functional RPE cells, offering a promising strategy for cell replacement therapies targeting RD diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is indispensable for retinal health, playing a critical role in maintaining photoreceptor function and the blood-retinal barrier. RPE dysfunction or loss is a key driver in the pathogenesis of devastating retinal degenerative (RD) diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), retinitis pigmentosa (RP), and Stargardt disease, which result in progressive vision loss and, in advanced stages, irreversible blindness1,2. Given the essential role of RPE cells in retinal function, the restoration or replacement of damaged RPE cells represents a transformative strategy for treating these debilitating conditions. However, generating fully functional and therapeutically safe RPE cells remains a substantial challenge in regenerative medicine.

Over the years, two main strategies have been explored to obtain RPE cells: isolation from native tissue and differentiation from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs)1,3,4,5,6. Both approaches have advanced considerably, yet some limitations remain. Tissue-derived RPE cells are relatively scarce and may gradually lose function in culture, which can constrain their use in large-scale applications. PSC-derived RPE cells, while considered an attractive source and already proven safe and feasible in clinical studies, often require lengthy differentiation and rigorous purification to ensure maturity and safety, adding to the complexity and cost of production7,8,9. An alternative method involves direct reprogramming using ectopic transcription factors (TFs), which can convert fibroblasts directly into RPE-like cells, bypassing the pluripotent stage10,11. While promising, this method still faces challenges such as genomic integration risks, low reprogramming efficiency, and high costs. These limitations underscore the need for alternative strategies that are transgene-free, rapid, and compatible with scalable, clinically relevant manufacturing processes.

Several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using small molecules to reprogram somatic cells into various lineages, such as neurons12,13, astrocytes14, hepatocytes15, and corneal endothelia16. Unlike TF-based methods, chemical reprogramming can offer a non-integrative, non-viral, and cost-effective approach to generating RPE cells. However, despite its potential, achieving precise reprogramming of somatic cells into RPE cells remains a complex and ongoing challenge. Current efforts predominantly rely on high-throughput screening of large chemical libraries, a process that is time-consuming and inefficient17. Furthermore, the incomplete understanding of the complex signaling networks and transcriptional regulation required to induce RPE fate has hindered progress. Thus, there is a critical need for more sophisticated, data-driven platforms that can accurately predict chemical compounds capable of inducing RPE-specific reprogramming.

Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and chemical perturbation databases have revolutionized our ability to study gene expression dynamics and cellular signaling pathways involved in reprogramming18. In particular, databases such as ChEMBL, STITCH, DrugBank, and Reactome provide essential resources for mapping interactions between transcription factors, chemical compounds, and biomolecules. These technological breakthroughs offer unprecedented opportunities to systematically identify key TFs and their interactions with chemical compounds, which could guide cell fate decisions. However, despite these advances, existing predictive platforms still have certain limitations. They rely on static models and pre-existing datasets, which do not fully capture the dynamic nature of cellular reprogramming, particularly in the context of complex cell types like RPE cells19. This highlights the urgent need for more advanced, dynamic, and scalable platforms capable of accurately predicting the chemical compounds required for RPE reprogramming.

Furthermore, identifying suitable intermediate cell states is crucial for enhancing the efficiency and stability of RPE reprogramming. Eye field (EF) or optic vesicle (OV)-derived progenitor cells, which naturally differentiate into RPE cells during retinal development, represent ideal intermediate states. These cells possess remarkable plasticity and differentiation potential, making them a biologically relevant step in guiding somatic cells toward an RPE fate20,21,22,23. Using EF (or OV) as an intermediate state not only increases reprogramming efficiency but also minimizes the risk of generating unwanted cell types, ensuring a more stable and reproducible conversion process.

In this study, we tackle the complex challenge of generating functional RPE cells by developing an innovative two-stage chemical induction protocol, enabled by the Single-Cell Reprogramming Compound Finder (scRCF), an advanced platform that integrates computational predictions guided by single-cell transcriptomics with a sophisticated DRUG-seq screening system. This platform systematically identifies optimal small-molecule combinations that guide fibroblasts to an EF-like state, ultimately generating functional chemical induced RPE (ciRPE) cells. These ciRPE cells closely mirror native RPE cells in morphology, gene expression, and essential functional properties. In an RD rat model, transplantation of ciRPE cells led to seamless integration into the host RPE layer, significant preservation of photoreceptors, and marked restoration of visual function. Multi-omics analyses provided insights into the dynamic transcriptional reprogramming that occurs during this process, while mechanistic studies revealed that chemical compounds synergistically activated endogenous TFs, such as Ascl1 and Olig2, directing fibroblast reprogramming toward the RPE cell phenotype. This study introduces a scalable, non-integrative, and cost-effective chemical approach for generating functional RPE cells, offering a promising innovative strategy for cell replacement therapies targeting RD diseases. Here, we present a two-step chemical reprogramming strategy that efficiently converts fibroblasts into functional RPE cells, bypassing the need for pluripotent intermediates and offering a promising solution for cell replacement therapies.

Results

Systematic screening of small molecules for EF fate reprogramming using scRCF

We established a two-step chemical induction strategy to reprogram fibroblasts into RPE cells. First, the fibroblasts were converted into an intermediate EF-like state and then were followed by differentiation into RPE-like cells. To address the challenge of identifying small molecules for cellular reprogramming, we developed the scRCF (Fig. 1a), which integrates single-cell transcriptomics with gene co-expression networks to identify key TFs and pathways, facilitating the rational selection of compounds. To refine their identification, we incorporated cellular-level sequencing (DRUG-seq2)24,25, enhancing the precision and efficiency of small molecule-driven reprogramming.

a The workflow of scRCF. The input of scRCF comprises scRNA-seq data from both initial and target cell types, in addition to three pre-established databases: (1) A small molecule perturbation database, integrating data from GEO and LINCS L1000, retaining only TFs identified in AnimalTFDB3.0; (2) The small-molecule target database and classification information, incorporating information from STITCH, Drug Repurposing Hub, and MedChemExpress; (3) A signaling network database, derived from Reactome and OmniPath. scRCF contains three major steps: (1) Identify candidate signaling proteins and perform pre-screening using the signaling network; (2) Calculate efficiency scores for small molecules based on the community partitioning results and output the highest-scoring compounds from each category as candidate small molecules; (3) Further screen the candidate small molecules using DRUG-seq2. b UMAP visualization of integrated scRNA-seq data from four MEF datasets and one primary EF (pEF) dataset, used to predict small molecules that facilitate reprogramming between the two cell types. c Volcano plot illustrating the differentially expressed TFs (DETFs) identified from scRNA-seq data of MEFs and EFs, analyzed using Seurat. DETFs were defined by p value < 0.05 and log2 fold change >1. d Candidate small molecules identified by preliminary screening with scRCF for reprogramming MEFs into EF cells. e Bar plot showing the Z-scores for cells treated with LAC + 1 small molecule combinations, based on a gene set of neuroectoderm- and EF-related genes. The Z-scores indicate relative gene expression changes for each drug, with higher values reflecting a stronger effect on the gene set. Bars are ordered from the highest to lowest average Z-score, and the dashed line represents the baseline score of zero. f Heatmap showing the gene expression profiles of neuroectoderm- and EF-related genes in cells after treatment with LAC + 1 small molecule combinations. The color scale represents log2-transformed expression values, with red indicating high expression, blue indicating low expression, and white indicating intermediate levels.

Using this platform, we screened and analyzed scRNA-seq data from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and EF cells (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1a)20,26,27,28. Differential gene expression analysis identified 258 TFs associated with cell type transitions (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Data 1). A modified SiPer19 framework calculated the similarity between these TFs and perturbation profiles from a small molecule database, pre-screening 489 signaling proteins. Further refinement via gene co-expression networks reduced the selection to 279 functionally relevant signaling proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1b and Supplementary Data 2). This approach revealed key signaling relationships and transcriptional regulators essential for cell fate transitions. To optimize screening, a random walk algorithm for modular partitioning of the protein network (Supplementary Fig. 1c) enabled effect scoring and prioritized small molecules based on pathway relevance. Ultimately, 41 high-efficacy candidates were identified, including Wnt pathway modulators CKI-7 and CHIR-99021, RTK pathway inhibitors orantinib and rebastinib, epigenetic regulators Trichostatin-A and RG108, TGF-β/Smad inhibitor A 83-01, and NF-κB pathway inhibitor BMS-345541 (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 1).

To further identify small molecules targeting EF fate reprogramming, we systematically evaluated 41 candidate compounds using DRUG-seq2. Given the neuroectodermal origin of the EF, we prioritized molecules such as LDN193189 (a BMP type I receptor inhibitor) and A 83-01 (a TGF-β type I receptor inhibitor) for their ability to suppress mesodermal and endodermal differentiation29,30,31. CKI-7 (an ATP-competitive casein kinase 1 inhibitor) was included to promote neuroectoderm formation32,33. Accordingly, LDN193189, A 83-01, and CKI-7 (LAC) were selected as the foundational induction cocktail for generating EF cells, with DRUG-seq2 employed to identify additional synergistic small molecules (Supplementary Fig. 1d). After 14 days of treatment with various small molecule combinations, DRUG-seq2 analysis revealed distinct molecular expression patterns and variations in target gene expression across different treatments, reflecting the specific responses to each condition (Fig. 1e, f). Effect scoring of gene sets associated with neuroectoderm and early EF development identified critical regulatory small molecules facilitating cellular reprogramming. Among these, Hh-Ag1.5, a Hedgehog signaling antagonist known for its role in eye development, achieved the highest score. Additional high-scoring compounds included GSK-3 inhibitors (CHIR-99021, 1-Azakenpaullone, Kenpaullone) and NF-κB pathway inhibitors (BMS-345541, WHI-P154) (Fig. 1e). Based on gene expression activation profiles and the removal of functionally redundant compounds (Fig. 1f), seven small molecules—Hh-Ag1.5, CHIR-99021, Golvatinib, Pirfenidone, BMS-345541, Masitinib, and RG108—were selected from the top-ranked candidates to form an optimized induction cocktail. Using this approach, we identified 10 small molecules from 4319 candidates capable of reprogramming MEFs into EF cells. In summary, we established a systematic, single-cell transcriptomic-driven screening framework integrating computational and experimental analyses. This approach identified a candidate induction cocktail of 10 small molecules with the potential to drive efficient cell fate reprogramming (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

Establishment of a two-stage chemical reprogramming strategy to generate ciRPE cells

First, we optimized serum-free, chemically defined medium containing these 10 small molecules and treated MEFs. For stage Ⅰ, we observed the emergence of epithelial-like cells colonies after 6 days treatment (Fig. 2a). Then, the colonies displayed more defined boundaries and distinct epithelial characteristics by day 12, although cell proliferation started to slow (Fig. 2a). To enhance the expansion of these colonies, we mechanically removed some surrounding cells. As expected, the colonies gradually expanded. By day 18, the cells exhibited tight packing, with some displaying a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and typical early RPE characteristics, such as cobblestone or hexagonal shapes (Fig. 2a). Further qRT-PCR analysis revealed a upregulation of genes related to EF fate (Pax6, Sox2, Six3, and Vsx2) and early RPE development (Mitf and Best1) (Fig. 2b). These findings indicated that our identified 10 small molecules induction protocol has the potential to convert MEFs into EF-like cells with early RPE characteristics.

a Representative morphological changes of MEFs exposed to a reprogramming medium (RM) containing 10 small molecules (Stage I) at different time points. Scale bar, 400 μm. b qRT-PCR analysis showing the expression of EF-related genes and early RPE development-associated genes at the indicated time points (n = 3 independent biological samples per group). c Representative morphological images of cells after exposure to differentiation and maturation medium (DM) containing three compounds (Stage II). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide, was used as a negative control. M3: NIC, RA, Activin A. Scale bar, 200 μm. d qRT-PCR analysis showing the expression of RPE-associated marker genes at the indicated time points (n = 3 independent biological samples per group). e Schematic diagram illustrating the genetic lineage-tracing strategy and chemical reprogramming of ciRPE cells from MEFs. f Morphological and tdTomato fluorescence expression changes on distinct days during the induction process of ciRPE cells. Scale bar, 400 μm. g Percentages of tdTomato+ cells induced by candidate cocktails on distinct days (n = 5 independent biological samples per group). p values indicate comparisons between adjacent time points. h Percentages of tdTomato+ cells upon treatment with candidate cocktails (all 13 compounds) and after subtraction of the indicated compound from the mixture. - represents withdrawing the indicated component. Each group was compared individually to the “ALL” group (n = 5 independent biological samples per group). i, Percentages of tdTomato+ cells before and after optimization of the reprogramming cocktail at different time points (n = 6 independent biological samples per group). j Schematic diagram illustrating the protocol for reprogramming MEFs into ciRPE cells, accompanied by representative morphological changes at key time points. MM represents the MEF medium, while RM represents the reprogramming medium and DM refers to the differentiation/maturation medium. Scale bar, 200 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to assess statistical significance. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To promote further differentiation and maturation of EF-like cells into RPE cells, we introduced Nicotinamide (NIC), Retinoic acid (RA), and Activin A (hereafter named M3) during stage Ⅱ induction. NIC facilitates RPE lineage commitment by modulating epigenetic and metabolic states, while suppressing neurogenic differentiation and promoting RPE-specific gene expression34,35,36. RA facilitates RPE differentiation and regulates the expression of RPE-specific genes to enhance pigment production10,37. Activin A promotes the differentiation of EF cells into RPE by activating the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway and regulating pigment production to maintain epithelial characteristics10,38,39. After two weeks of treatment, cells exhibited typical hexagonal RPE morphology and pigmentation (Fig. 2c). Subsequent qRT-PCR analysis confirmed significant upregulation of Best1, and mature RPE genes such as Rpe65, Tyr, Lhx2, Pmel, and Otx2 (Fig. 2d), indicating successful generation of ciRPE cells. To further validate the reprogramming effectiveness, we employed a lineage tracing strategy to monitor the reprogramming process (Fig. 2e). The Best1 gene is specifically expressed in RPE cells, and its promoter has been shown to effectively drive the expression of reporter genes in transgenic RPE cells10,40. We used Best1-Cre/ROSA26tdTomato fluorescent reporter mice, which demonstrated stable and specific tdTomato expression in RPE cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). We performed fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to collect Best1-tdTomato negative (tdTomato-) MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 2c). These tdTomato- MEFs were negative for RPE marker genes such as Mitf, Cralbp, Best1, and Rpe65 (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e), confirming the absence of residual RPE or progenitor cells. We then subjected tdTomato- MEFs to a two-step chemical induction (stage Ⅰ with 10 small molecules, followed by stage Ⅱ with M3). After stage Ⅱ induction (day 32), the proportion of tdTomato-positive (tdTomato+) cells increased, reaching 16.58%, compared to 2.51% after stage Ⅰ induction (Fig. 2f, g). These results confirm that the constructed chemical induction system effectively reprogrammed MEFs into RPE cells.

To minimize potential toxic effects of small molecules on cells, we conducted a minus-one experiment to further optimize the chemical reprogramming system. The results indicated that removing Golvatinib, Pirfenidone, and Masitinib during the stage Ⅰ induction had minimal impact on the positive rate of tdTomato expression (Fig. 2h), achieving a positive rate of 19.66% (Fig. 2i). Consequently, we finalized the reprogramming induction system, consisting of seven small molecules from the stage Ⅰ (M7: LDN193189, A 83-01, CKI-7, Hh-Ag1.5, CHIR-99021, BMS-345541, and RG108) and three compounds from stage ⅠⅠ (M3: NIC, RA, and Activin A) (Fig. 2j). Finally, we validated the robustness of our reprogramming system across MEFs from different batches and different genetic backgrounds, including C57BL/6J and 129S4/SvJae (Supplementary Fig. 2f, g). Furthermore, this M7 + M3 system successfully facilitated the reprogramming of tail-tip fibroblasts (TTFs) from neonatal mice into ciRPE cells (Supplementary Fig. 2f, g). Collectively, these results demonstrate that our optimized M7 + M3 system enables efficient reprogramming of MEFs into functional ciRPE cells.

Characteristics of ciRPE cells

To further confirm the phenotypic and functional properties of ciRPE cells, we first performed immunofluorescence staining to assess the expression of RPE markers. The results demonstrated that ciRPE cells exhibit tight junction structures (ZO-1) and express high levels of RPE markers, including Pax6, Rpe65, Mitf, Best1, and Cralbp (Fig. 3a). Additionally, these cells exhibited polarized morphology, with ZO-1 localized to the apical membrane and Best1 to the basal membrane (Fig. 3b). This structural polarity is crucial for RPE functions, particularly the apical microvilli, which mediate the phagocytosis and clearance of shed photoreceptor outer segments (POSs), ensuring normal photoreceptor turnover41,42. Subsequently, we analyzed the structural characteristics of ciRPE cells using transmission electron microscopy. These cells exhibited distinct apical microvilli, pigment granules, and tight junctions (Fig. 3c), indicating that their morphology closely resembles that of native RPE cells in vivo.

a Representative immunostaining showing that MEF-derived ciRPE cells express ZO-1, Pax6, Rpe65, Mitf, Best1 and Cralbp. Scale bars, 50 μm. b Representative Z-stack confocal micrographs showing ciRPE cells with typical polarized expression of RPE markers. ZO-1 (green) demonstrates apical localization (top), while Best1 (red) shows basolateral localization (bottom). Scale bars, 10 μm. c Representative transmission electron microscopy image of ciRPE cells showing apical microvilli (yellow arrows), melanin granules (red arrows) and tight junctions (black arrows). Scale bars, 1 μm. d Representative confocal micrograph showing phagocytosis of POSs (green) by ciRPEs. The apical sides of ciRPE cells are stained with ZO-1(violet), whereas nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 50 μm. e Apical and basal secretion of PEDF and VEGF by MEFs, ciRPE, and pRPE cells cultured on Transwells. Each group was compared to the ciRPE group within apical and basal compartments (n = 6 independent biological samples per group). f Representative morphological images showing dome structures formed by ciRPE cells during in vitro culture. The red arrows indicate the dome morphology observed under different phase-contrast microscopy conditions. Scale bars, 50 μm. g TEER measurements of MEFs, ciRPE, and pRPE cells over time in culture (n = 6 independent biological samples per group). Data are mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to assess statistical significance. Three independent experiments were performed with similar results and representative results are shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To evaluate the phagocytic capacity of ciRPE cells, we introduced fluorescently labeled porcine POSs and latex beads into the ciRPE cell culture medium. After an incubation period, laser scanning confocal microscopy revealed the presence of engulfed POS and latex beads within the ciRPE cells (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 3a), confirming their phagocytic functionality. Additionally, RPE cells are known to exhibit polarized secretion of growth factors, a process crucial for maintaining homeostasis between the retina and the choroid34,43. We further analyzed the polarized secretion profile of VEGF and PEDF across MEF, ciRPE, and primary RPE (pRPE) cells. As shown in Fig. 3e, ciRPE cells exhibited a characteristic RPE-like pattern, predominantly secreting VEGF from the basal side and PEDF from the apical side. This polarized secretion was consistent with that observed in pRPE cells and distinct from the non-polarized profile of MEFs, supporting the functional maturation of ciRPE cells. Moreover, ciRPE cells formed dome-like structures during in vitro culture (Fig. 3f), suggesting that their epithelial layer is capable of effective fluid transport while maintaining tight junction integrity. Measurements of transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) further supported the establishment of tight junctions and barrier function in ciRPE cells. As shown in Fig. 3g, ciRPE cells exhibited a steady increase in TEER over the first three weeks, eventually stabilizing around 80 Ω·cm². This value was markedly higher than that of MEFs, which showed no measurable barrier formation, and approached the TEER levels observed in pRPE cells, although somewhat lower in magnitude. Collectively, these data indicate that ciRPE cells exhibit key functional characteristics typical of native RPE cells.

To further validate the proliferative potential of ciRPE cells, we purified and cultured them in an expansion medium containing basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) for continuous passaging. The results showed that ciRPE cells could be passaged for at least 20 generations while maintaining a stable RPE morphology and normal karyotype (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). In contrast, pRPE cells gradually lost pigmentation and hexagonal morphology by the sixth passage, with a substantial reduction in growth rate (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d), consistent with previous studies44. Across different passages, ciRPE cells showed higher proliferative capacity compared to pRPE cells, with EdU incorporation rates consistently exceeding those of pRPE cells (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Flow cytometric analysis indicated that the cell cycle distribution of ciRPE cells (P3) was similar to that of pRPE cells, with 70%, 17.4%, and 6.87% of cells in the G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3e). In summary, our results indicate that ciRPE cells closely resemble native RPE cells in terms of morphology and functionality, exhibiting typical polarized characteristics, phagocytic capabilities, and a polarized secretion profile of growth factors. Additionally, they show strong proliferative capacity and stability.

Finally, we confirmed the reprogramming of MEFs into ciRPE cells using a lineage tracing strategy with Fsp1-Cre and ROSA26-tdTomato mice. MEFs from E13.5 transgenic mice (Fsp1-Cre/ROSA26tdTomato) were sorted by FACS to obtain tdTomato+/Best1- cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). These cells initially lacked RPE marker expression (Supplementary Fig. 4c–e). After chemical reprogramming, ciRPE cells expressed RPE-specific genes and co-expressed tdTomato (Supplementary Fig. 4f, g), confirming their origin from the initial MEFs.

Molecular roadmap of ciRPE chemical reprogramming

To enhance our understanding of the intricate process of reprogramming MEFs into ciRPE cells, we conducted a comprehensive multi-omics analysis (Fig. 4a). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on cells at day 0, day 7, day 18, and day 32 of the reprogramming process. Principal component analysis (PCA) of the RNA-seq result revealed substantial transcriptional changes throughout this dynamic process, demonstrating a gradual transition from fibroblasts to ciRPE cells. Notably, the final ciRPE cells exhibited greater transcriptional similarity to pRPE cells compared to earlier stages (Fig. 4b). Time-series fuzzy clustering analysis of differentially expressed genes revealed four distinct gene clusters corresponding to the stages of reprogramming: fibroblasts (day 0), intermediate state (day 7), EF-like cells (day 18), and mature ciRPE cells (day 32) (Fig. 4c).

a Schematic illustrating the multi-omics sequencing strategy employed to analyze the reprogramming process from MEFs to ciRPE cells. b PCA of RNA seq and CUT&Tag data (H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3) were performed on samples collected at days 0, 7, 18, and 32 (ciRPE) of reprogramming, along with pRPE cells serving as the control. c Heatmap showing differentially expressed genes in MEF to ciRPE cell reprogramming samples at indicated time points. The number above heatmap indicates independent biological replicates. Representative genes (left side of the heatmap) and associated gene ontology (GO; right side of the heatmap) for each block are shown. Red and blue indicate upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively. Differential expression was analyzed using the R package limma (v3.58.1) following normalization with edgeR (v4.0.16). Significantly changed genes were defined by |log₂ fold change| > 1.5 and adjusted p < 0.01 (Benjamini-Hochberg correction). d Dynamics of CUT&Tag peaks (H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K27me3) associated with cluster-specific genes (C). The red line indicates the median CUT&Tag peaks over time, the blue line represents the median RNA expression levels, and the gray background lines depict individual peak values across time points. e Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) analysis of integrated scRNA-seq data from cells collected at the indicated time points during the reprogramming process of MEFs to ciRPE cells. f UMAP plot showing identified cell types in samples collected at the indicated time points during the reprogramming process. g Dot plot illustrating the expression of representative marker genes across different cell types during the reprogramming process. h RNA velocity streamline plot illustrating the transitions of cell populations during the reprogramming process using the scVelo method. The arrows represent the flow determined by the ratio of unspliced to spliced transcripts, predicting dynamic changes in cell identity. Black arrows indicate RNA velocity flow based on the unspliced-to-spliced transcript ratio, while the gray to teal arrows are used for visual enhancement to highlight specific trajectories. i Heatmap showing the gene expression similarity between cell types during the reprogramming process and those reported in previous studies. pEF cells represent the data used for small molecule prediction as described above, while pRPE data were obtained from the GSE183572 dataset.

During the initial transition from fibroblasts to the intermediate state, downregulated genes such as Fn1, Itga11, and Runx2 were linked to reduced fibroblast functionality and proliferation activity. In contrast, the upregulated genes including Sox2, Ascl1, Gli2, Gli1, Gbx2 were linked to neuroectodermal processes (Fig. 4c). These results suggest that early chemical induction reprograms gene expression by activating neuroectodermal genes and signaling pathways while suppressing fibroblast characteristics, facilitating the progression towards a neuronal fate. Additionally, transient activation of genes such as Tfap2a, Rorb, Etv5 during the intermediate phase was associated with epithelial proliferation and inflammation, reflecting enhanced cell-cell interactions and adaptation to environmental signals (Fig. 4c). By day 18, the upregulated genes were predominantly related to eye development, such as Pax6, ID4 and Best1. As induction progressed towards mature RPE, early EF-related genes showed a trend of downregulation. By day 32, genes associated with RPE function (e.g., Rpe65, Lhx2, Tyr, Cralbp, Otx2) and pigment cell differentiation (e.g., Pmel, Mlana, Slc24a5) were upregulated (Fig. 4c), confirming the transition to mature, pigmented ciRPE cells.

To confirm successful conversion from fibroblasts to ciRPE cells, we analyzed 16 fibroblast-specific and 18 RPE-specific genes. During reprogramming, fibroblast markers were considerable downregulated while RPE markers were upregulated, indicating that ciRPE cells acquired RPE characteristics (Supplementary Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 2). Ultimately, the gene expression profile of ciRPE cells closely matched that of pRPE cells, validating the successful attainment of RPE identity (Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). Notably, the transcriptional trajectory during reprogramming was directed toward ectodermal and eye field lineages without evidence of PSC-like activation (Supplementary Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 2). Key pluripotency genes such as Pou5f1, Nanog, and Lin28a remained silenced throughout, and Klf4 showed only a mild, transient increase consistent with its physiological role in fibroblasts (Supplementary Fig. 5d). These findings indicate that reprogramming proceeded via direct lineage conversion rather than a pluripotent intermediate.

Epigenetic remodeling plays a crucial role in cell fate reprogramming45,46,47,48. We used CUT&Tag sequencing to track dynamic modifications in H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3 histone marks near gene transcription start sites. PCA analysis highlighted notable chromatin state alterations throughout reprogramming, showing that ciRPE cells closely resembled pRPE cells in histone modification patterns (Fig. 4b). H3K4me3 increased progressively from MEFs to ciRPE cells, peaking at days 18 and 32, linked to RPE gene activation. The loss of H3K4me3 decreased over time, suggesting its role in establishing new gene expression. H3K27ac changes varied across stages, with a decrease from day 7 to 18 indicating gene repression for EF specification. H3K27me3 dynamics reflected gene silencing: substantial loss from MEFs to day 7 facilitated differentiation, while increased acquisition from day 7 to 18 established new silencing. By the ciRPE stage, H3K27me3 levels stabilized, supporting the mature RPE phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Further analysis showed that the CUT&Tag signals for H3K4me3 and H3K27ac correlated with RNA expression levels, underscoring their role in gene activation (Fig. 4d). Although H3K27me3 generally showed a negative correlation with RNA-seq data, some deviations were observed during the fibroblasts stage, likely due to predominant activating marks. From day 7 to 18, increased H3K27me3 correlated with decreased RNA expression, while a trend toward stabilization at the ciRPE stage reflected balanced gene silencing and activation (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 5f). These findings underscore the intricate role of dynamic histone modifications in cell type transitions at various stages, highlighting epigenetic regulation’s pivotal role in MEF-to-RPE reprogramming. By modulating gene activation and silencing, cells successfully reprogram towards the RPE lineage.

To accurately delineate the reprogramming trajectory, we performed scRNA-seq at three key time points during the reprogramming of MEFs into ciRPE cells. Single-cell transcriptomes were obtained from samples collected on days 7, 18, and 32, yielding 9679, 13,227, and 11,282 cells, respectively (Fig. 4e). Cluster-specific marker gene analysis revealed that on day 7 of reprogramming, the cell population consisted of MEF cells, neuroprogenitor-like intermediate cells, and a small fraction of EF-like cells. By day 18, the proportion of intermediate cells cells decreased, while that of EF-like cells increased. By day 32, EF-like cells diminished, and a prominent population of ciRPE cells emerged (Fig. 4f, g and Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). To further validate the reprogramming trajectory of ciRPE cells, we performed single-cell pseudotime trajectory analysis. The analysis revealed a sequential transition from MEFs to neuroprogenitor-like intermediate cells, followed by differentiation into EF-like cells and ultimately ciRPE cells (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 6c). Unsupervised clustering highlighted dynamic molecular events during this process, including fibroblast-to-neuroprogenitor transitions, progression through eye development stages, and the establishment of RPE-specific functions such as pigmentation and retinoid metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Interestingly, among two identified neuroprogenitor-like subpopulations, the differentiation trajectory of MEFs primarily aligned with one subgroup expressing neurogenic and proliferative markers (e.g., Mki67, Cdk1, Top2a), while the other subgroup lacked these markers (Supplementary Fig. 6e). This indicates that proliferative neuroprogenitor cells are essential for subsequent differentiation into EF-like cells. RNA velocity analysis confirmed the progression of reprogramming toward ciRPE cells, consistent with the trajectory observed in pseudotime analysis (Supplementary Fig. 6f, g). We further performed similarity analysis between the reprogrammed cell population and publicly available single-cell datasets. The induced cells showed a similarity score of 0.80 with RPE cells and 0.64 with EF-like cells (Fig. 4i), indicating that the reprogrammed cells acquired both EF-like and RPE characteristics. In conclusion, our two-step chemical reprogramming system effectively directs MEFs through neuroprogenitor-like intermediate and EF-like stages to generate functional ciRPE cells. This sequential process highlights the precise control of lineage-specific gene expression and epigenetic remodeling.

Transcriptional activation of neural and eye development master factors governs ciRPE reprogramming

To identify the key TFs driving the reprogramming of MEFs into ciRPE cells, we integrated single-cell data with SCENIC analysis to systematically investigate the regulatory factors expressed in each cell type and their dynamic changes throughout reprogramming. Using a logFC>1.0 threshold, we identified 125 TFs across four cell types, highlighting their distinct roles in different reprogramming stages (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Data 3). Using the STRING database, we constructed an interaction network of these TFs, revealing their cooperative roles during reprogramming (Supplementary Fig. 7a and Supplementary Data 4). Network analysis using maximal clique centrality (MCC) identified the 15 key TFs, including MEF-specific factors (Dlx2 and Dlx1), transiently activated factors at day 7 (Sox11, Foxa2 and Pax2), and factors with sustained high expression from days 7 to 18 (Sox2, Sox9, Olig2, Zic1, Ascl1, Atoh1, Pou3f2 and Gbx2), as well as ciRPE-related factors (Lhx2 and Otx2) (Fig. 5b, c and Supplementary Data 5). Notably, the majority of these key TFs are associated with neuroectodermal development, suggesting that neuroectodermal fate is a critical transitional phase in the reprogramming from MEF to EF-like and ciRPE cells.

a Volcano plots illustrating TFs with differences in regulon activity across various cell types during reprogramming from SCENIC. b The bar-dash plot shows the MCC scores for the top key 15 TFs. c Heatmap showing the expression of the top key 15 TFs at indicated time points during cellular reprogramming. d Normalized RNA-seq and CUT&Tag sequencing of histone modifications (H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3) at the genome loci of Ascl1, Olig2, Zic1, Pou3f2, and Lhx2 at the indicated time points during cellular reprogramming. Relative reprogramming efficiency, assessed by the proportion of tdTomato+ cells at day 32, following knockdown of Ascl1 (e) or Olig2 (f) at the indicated time points under M7 + M3 induction (n = 5 independent biological samples per group). The reprogramming efficiency at day 32 for M7 + M3-induced cells was set to “1” with DMSO serving as the negative control. WT, wild-type; Control KD, scramble shRNA-mediated gene knockdown. g scRCF network visualization of the putative signaling cascades induced by small molecules targeting Ascl1 and Olig2. Orange rectangles represent perturbagens, blue diamonds represent signaling protein targets, white ellipses represent intermediate signaling proteins, and green hexagons represent query TFs. Data are mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to assess statistical significance. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further explore the regulatory mechanisms underpinning these TFs, we integrated RNA-seq and CUT&Tag-seq data to assess the activity of the top five TFs (Fig. 5d). On day 0, neuroectodermal TFs, including Ascl1, Olig2, Zic1, Pou3f2, displayed weak activation marks (H3K4me3 and H3K27ac) and predominantly repression by H3K27me3, consistent with their suppression in the stable fibroblast state. By day 7, as cells transitioned into a neuroprogenitor-like intermediate state, these TFs showed increased activation marks and RNA expression, indicating the activation of neuroectodermal pathways. This coincided with the suppression of fibroblast characteristics and the initiation of neurogenesis. By day 18, activation of Ascl1 and Olig2 had decreased, whereas Zic1 and Pou3f2 remained highly active. At day 32, during the ciRPE phase, Lhx2 exhibited robust activation and notable RNA upregulation, while earlier neuroectodermal TFs were silenced (Fig. 5d). Notably, while H3K27me3 played a key repressive role during the early phase (days 0-7), its effect diminished in later stages, implying that alternative repressive mechanisms, such as DNA methylation or other histone marks, may regulate TF activity at these stages. These findings underscore the critical role of dynamic epigenetic modifications and TF expression in guiding cell fate transitions during MEF-to-ciRPE reprogramming. Overall, neurodevelopmental TFs act as early “switches” for EF specification, while RPE-associated TFs govern later stages, driving RPE maturation.

Ascl1 and Olig2 have been reported as essential neurodevelopmental TFs that regulate neural progenitor cell fate and reprogramming49,50,51,52. To determine the impact of Ascl1 and Olig2 on fibroblast-to-EF reprogramming, we investigated how the knockdown of these genes individually with small hairpin RNA (shRNA) affected the efficiency of ciRPE induction. As expected, the knockdown of either Ascl1 or Olig2 substantially reduced the reprogramming efficiency, confirming that they positively regulate reprogramming (Fig. 5e, f and Supplementary Fig. 7b-d). Importantly, the knockdown of these genes at the early stage had the most considerable effect on reprogramming efficiency, underscoring their pivotal role in initiating neuroectodermal transitions necessary for subsequent ciRPE differentiation (9.1-, 16.7-, and 3.6- fold reduction when shAscl1 was transduced at days 0, 7 and 18, respectively, Fig. 5e; and 12.5-, 8.3-, and 2.8- fold reduction when shOlig2 was transduced at days 0, 7 and 18, respectively, Fig. 5f). On the other hand, the overexpression of Ascl1 or Olig2 enhanced the efficiency of ciRPE reprogramming mediated by M7 + M3 (Supplementary Fig. 7e), validating that Ascl1 and Olig2 are directly involved in ciRPE reprogramming.

These findings emphasize the importance of transitioning through neuroectodermal and EF-like states for successful MEF-to-ciRPE reprogramming, validating the effectiveness of our first-stage small molecule cocktail in orchestrating these transitions. Using scRCF, we constructed a regulatory network to elucidate how small molecules modulate key TFs during reprogramming (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 7f). The analysis indicated that the activation of key TFs is a collective contribution of these small molecules, which regulate TFs through their respective target proteins, orchestrating the activation of multiple signaling pathways, including Wnt, TGF-β, and Hedgehog, which collectively guide precise cell fate transitions toward ciRPE reprogramming.

Generation of human ciRPE cells from HEFs by chemical reprogramming

In our efforts to generate human ciRPE (hciRPE) cells, we initially attempted to apply the mouse induction system to reprogramming human embryonic fibroblasts (HEFs). However, the outcomes were suboptimal, likely due to the higher complexity and stricter signaling requirements of human cellular reprogramming compared to murine systems. Consequently, it was necessary to adjust the small molecule combination to enhance reprogramming efficacy and success rates. During the selection of compounds, we focused on the “OV” stage of early human retinal development as a critical intermediate state for guiding human RPE reprogramming. Using single-cell data from human embryos (carnegie stages 12 and 16)21 and 30-day-old retinal organoids22 (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b), we strategically incorporated the top 15 key TFs (Fig. 5b) identified in the mouse ciRPE reprogramming process into scRCF. This approach enabled more accurate identification of small molecules to guide the reprogramming of hciRPE cells. Ultimately, we identified 42 candidate small molecules (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Data 6–8). Notably, LDN193189, CHIR-99021, Hh-Ag1.5, RG108, and BMS-345541 (LCHRB), identified in the murine RPE reprogramming system, were included in the foundational cocktail. We then screened additional compounds using DRUG-Seq2 (LCHRB + 1), ranking the top 10 with a comprehensive scoring system (Supplementary Fig. 8c, d), leading to a final selection of 15 small molecule combinations. We hypothesized that these combinations would promote HEFs convert into OV-like cells.

a Candidate small molecules identified by preliminary screening with scRCF for reprogramming HEFs into OV. b Schematic diagram of the protocol for the reprogramming of HEFs into hciRPE cells, along with representative morphological changes at indicated time points. HM represents the HEF medium, while RM represents the reprogramming medium and DM refers to the differentiation/maturation medium. Scale bar, 300 μm. c FACS purification of reprogrammed BEST1-EGFP + hciRPE cells. d Representative optical microscopy and TEM images of hciRPE cells showing melanin granules (red arrows). Scale bars, 1 μm. e qRT-PCR analysis showing the expression of RPE-associated genes at the indicated time points during reprogramming (n = 3 independent biological samples per group). f Representative immunostaining analysis showing positive expression of ZO-1, RPE65, MITF and BEST1 in the BEST1-EGFP- HEFs-derived hciRPE cells. Scale bar, 20 μm. g PCA of samples from day 0, day 12, day 24 and day 38 (hciRPE) of celluar reprogramming, and the control primary hRPE cells. h Heatmap showing differentially expressed genes in HEF to hciRPE cell reprogramming samples at indicated time points. The number above heatmap indicates independent biological replicates. Representative genes (left side of the heatmap) and associated GO (right side of the heatmap) for each block are shown. Red and blue indicate upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively. Differential expression was analyzed using the R package limma (v3.58.1) following normalization with edgeR (v4.0.16). Significantly changed genes were defined by |log₂ fold change| > 1.5 and adjusted p < 0.01 (Benjamini-Hochberg correction). i Polarized secretion of VEGF and PEDF from the apical and basal sides of hciRPE cells grown on Transwells (n = 6 independent biological samples per group). j TEER in hciRPE cells for 30 days. p values indicate comparisons between adjacent time points (n = 5 independent biological samples per group). Data are mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA (e) and unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test (i, j). Three independent experiments were performed with similar results and representative results are shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To validate our hypothesis, we developed the BEST1 Pr-EGFP-HEFs tracing cell line to monitor the reprogramming process (Supplementary Fig. 8e). Initially, these cells did not express RPE markers such as MITF, CRALBP, BEST1, and RPE65, nor did it exhibit EGFP expression (Supplementary Fig. 8f, g). Upon successful reprogramming, the Best1 promoter was expected to drive EGFP expression specifically in induced cells. We added the 15 selected chemical compounds to the reprogramming medium to initiate HEFs reprogramming. During the early induction phase, HEFs exhibited rapid proliferation; however, by day 12, only a few clones emerged. To support clone growth, we removed surrounding cells, but their proliferation remained slow. By day 24, only a limited number of cells were BEST1-EGFP positive. Continued induction showed minimal change, with cell numbers declining. We then introduced three compounds (NIC, RA, and Activin A, M3) to enhance RPE differentiation and maturation, but the proportion of BEST1-EGFP-positive cells remained low.

Due to the suboptimal efficiency and potential cytotoxicity of excessive compounds, further optimization of the induction system was required. Starting with the initial 15 small molecules and 3 differentiation and maturation compounds, we explored various combinations and culture conditions. We found that using 9 small molecules (M9: CHIR-99021, Hh-Ag1.5, LDN193189, RG108, BMS-345541, R-268712, BIX-01294, VPA, SB-431542) in the initial phase and 2 compounds (M2: NIC, and Activin A) during the differentiation maturation phase resulted in 6.74% BEST1-EGFP-positive (hciRPE) cells by day 38 (Fig. 6b, c), whereas other combinations yielded lower proportions of positive cells.

We further characterized the molecular and biological features of hciRPE cells. After purification and expansion, induced hciRPE cells exhibited characteristic hexagonal morphology and notable melanin granules (Fig. 6d), while maintaining a normal karyotype (Supplementary Fig. 8h). qRT-PCR analysis and immunofluorescence collectively confirmed the expression of key RPE markers, including MITF, CRALBP, BEST1, and RPE65, with EGFP specifically co-expressed in induced hciRPE cells (Fig. 6e, f). Transcriptomic analysis indicated that the expression profile of hciRPE cells closely resembled that of primary human RPE (hRPE) cells used as a positive control (Fig. 6g, h). In both hciRPE cells and intermediate reprogramming states, fibroblast-specific genes (e.g., FN1 and RUNX2) were downregulated, while RPE-specific genes (e.g., RPE65, TYR, LHX2, and CRALBP) were upregulated. Notably, TFs such as RORB, PAX3, DES, and TFAP2A were upregulated during the intermediate stages, suggesting a possible activation of neuroectodermal transcriptional programs and a potential transition toward RPE lineage commitment. By day 24, markers associated with OV and retinal progenitor cells (PAX6, SIX3, VSX2, MITF and BEST1) were activated (Supplementary Fig. 8i), indicating the successful transition into OV-like cells, a critical intermediate state for RPE lineage commitment. With continued differentiation, these cells ultimately resembled hRPE cells (Fig. 6g, h). Further analysis showed that hciRPE cells secreted growth factors such as VEGF and PEDF (Fig. 6i), and TEER analysis confirmed the presence of tight junctions and barrier function (Fig. 6j). Moreover, hciRPE cells maintained typical RPE morphology, molecular identity, and stable proliferative capacity over multiple passages (Supplementary Fig. 8j-l). These findings demonstrate that our optimized two-stage chemical reprogramming system effectively converts HEFs into functional hciRPE cells, providing a safe and non-integrative approach for studying RPE biology and developing cell-based therapies.

ciRPE cell transplantation restores retinal function in RCS rat

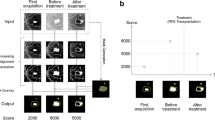

Leveraging the functional and safety advantages of ciRPE cells, we initiated in vivo transplantation studies to evaluate their therapeutic potential for RD diseases. The Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) rat, characterized by a mutation in the Mertk gene that impairs RPE phagocytosis, serves as a well-established RD model18,38. FACS-purified tdTomato+ ciRPE cells were transplanted into the subretinal space of 3-week-old RCS rats (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 9a, b), with PBS, mESCs, MEFs, or pRPE cells transplanted as controls. Postoperative Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) revealed transient subretinal bulges that resolved within three weeks, suggesting initial engraftment and tissue adaptation (Fig. 7b). During a 4-month follow-up, no tumor formation was observed in the ciRPE group, whereas 13 out of 15 rats receiving tdTomato-labeled mESCs developed visible intraocular tumors (Fig. 7c), consistent with results from subcutaneous teratoma assays (Supplementary Fig. 9c), supporting the safety profile of ciRPE cells.

a Schematic diagram of subretinal ciRPE cell transplantation in RCS rats. b Representative OCT images showing the subretinal transplantation site of ciRPE cells in RCS rats at 0, 1, 2 and 3 weeks post-transplantation. Scale bar, 600 μm. c Representative photographs from in vivo imaging showing tumor formation in nude mice following subretinal transplantation of tdTomato-labeled mESCs (via lentivirus) and tdTomato-ciRPE cells. Quantitative analysis data are displayed in the right panel (n = 10 independent mice per group). d Representative images of bright-field (top) and immunofluorescence (bottom) from eye tissue sections 8 weeks after subretinal transplantation of tdTomato-ciRPE into RCS rats. The dashed box indicates the area of cell transplantation. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 200 μm. e Immunofluorescence analysis of whole retinal sections at 12 weeks post-transplantation showed clusters of tdTomato+ ciRPE cells in the transplanted area, forming a monolayer structure. Magnified views of the regions delineated by the dashed-line boxes show: (i) a non-transplanted region and (ii) transplanted areas. Quantitative analysis data are displayed in the right panel (n = 10 independent rats per group). Scale bars, 500 μm. f–h Representative immunostaining showing tdTomato+ ciRPE cells coexpressing Mitf (F), Best1 (G), and Pax6 (H). Scale bars, 50 μm. i Representative TUNEL-stained micrographs of retinal cryosections from RCS rats 12 weeks after ciRPE cell transplantation (left), with statistical results shown on the right, using the sham-transplanted group as a control (n = 10 independent rats per group). Scale bars, 50 μm. j Representative immunostaining showing transplanted tdTomato+ ciRPE cells coexpressing Rhodopsin in the retina of RCS rats 12 weeks after transplantation. Scale bars, 50 μm. k Representative b-wave responses of the ciRPEs-transplanted and sham-transplanted groups were assessed through fERG with an intensity of 0.48 log cd*s/m² (dark 3.0) at 4w, 8w, 12w and 16w post transplantation (left). Statistical analysis of b-wave amplitudes in the ciRPEs-transplanted and sham-transplanted groups (right) (n = 6 independent rats per group). l Schematic illustration of the qOMR test setup (left). Quantitative evaluation of visual acuity in the ciRPEs-transplanted and sham-transplanted groups, obtained through the qOMR test at 4w, 8w, 12w and 16w post transplantation (right) (n = 10 independent rats per group). Data are mean ± SD. Unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to assess statistical significance. Three independent experiments were performed with similar results and representative results are shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Histological and immunostaining analyses revealed that tdTomato+ ciRPE cells formed clusters in the subretinal space at 4 weeks and organized into a structured monolayer by 12 weeks (Fig. 7d, e), with expression of mature RPE markers such as Mitf, Cralbp, Pax6, and Rpe65 (Fig. 7f–h). Typically, RCS rats exhibit severe retinal dysfunction between 2 to 3 months of age, characterized by substantial photoreceptor loss and thinning of the outer nuclear layer (ONL)38. At 12 weeks post-transplantation, the ONL in the ciRPE-transplanted eyes was thicker compared to both the sham and MEF groups, and moderately greater than in the pRPE group (Fig. 7e and Supplementary Fig. 9d–f), indicating that ciRPE transplantation partially protected photoreceptors and slowed their degeneration, thereby contributing to the preservation of retinal structure and function. Consistently, TUNEL staining showed fewer apoptotic cells in the ONL of ciRPE-transplanted eyes compared to the Sham, MEF, and pRPE groups (Fig. 7i and Supplementary Fig. 9g, h), further supporting the protective effect of ciRPE cells against photoreceptor degeneration. The loss of RPE cell phagocytic function due to the Mertk mutation in RCS rats results in impaired clearance of POSs53,54. To assess whether ciRPE cells could restore this function in vivo, we evaluated their uptake of Rhodopsin, a major component of photoreceptor outer segments. After 12 weeks post-transplantation, tdTomato and Rhodopsin co-localization was clearly observed within the transplanted ciRPE cells (Fig. 7j), while such signal was not detected in the MEF group and was barely detectable in the pRPE group (Supplementary Fig. 9i), indicating that ciRPE cells more effectively integrated into the host RPE layer and regained phagocytic activity.

To comprehensively evaluate the impact of ciRPE cell transplantation on retinal function, we performed dark-adapted flash electroretinography (fERG) and quantitative optomotor response (qOMR) tests. fERG recordings from 4 to 16 weeks post-transplantation showed that ciRPE-transplanted eyes exhibited higher b-wave amplitudes than those in the sham, MEF, and pRPE groups, particularly at earlier time points (Fig. 7k and Supplementary Fig. 9j), suggesting that ciRPE cells contributed to photoreceptor preservation and partial functional recovery. Consistent with this, qOMR tests revealed improved visual behavior in the ciRPE group, including increased sensitivity to spatial frequency and motion direction, as reflected by elevated qOMR scores (Fig. 7l and Supplementary Fig. 9k). In contrast, the MEF group showed no improvement relative to the sham group, while the pRPE group exhibited a degree of functional rescue that was slightly weaker than that observed in the ciRPE group (Supplementary Fig. 9k). These results support the survival, safety, and functional integration of ciRPE cells over the examined period in the RCS model, and suggest their potential to partially restore retinal function in degenerative conditions.

Discussion

The RPE is crucial for maintaining retinal structure and supporting photoreceptor function, with its dysfunction directly contributing to various RD diseases. While RPE cell replacement therapy holds significant potential for treating these conditions, current methods face challenges in safety, efficiency, and scalability for RPE cell production55,56,57. Our study demonstrates that chemical reprogramming efficiently generates functional RPE cells without genetic manipulation, offering a safer and more clinically promising approach for cell replacement therapies. By leveraging a predictive platform informed by single-cell transcriptomic data, we systematically identified small-molecule combinations that guide fibroblasts toward an EF/OV-like state, forming the basis of our two-stage reprogramming protocol. Using a two-stage reprogramming protocol, fibroblasts were directed into an intermediate state with RPE precursor characteristics and subsequently matured into functional RPE cells. Mechanistic studies identified key small molecules and TFs involved in this process. Transplantation experiments demonstrated the therapeutic potential of ciRPE cells, which integrated into the host RPE layer, reduced apoptosis, and improved visual function in an RD model.

Compared to traditional TF-based reprogramming strategies that rely on genomic integration, chemical modulation of TF activity offers a safer and more clinically viable approach. However, identifying optimal small molecules through conventional large-scale chemical library screening remains laborious and time-consuming. Zheng et al. developed the SiPer platform, which uses single-cell data to predict compounds that target specific TFs for cellular conversion19. While effective, its reliance on static network models and pre-existing datasets limits its ability to capture dynamic signaling interactions. In contrast, our scRCF platform integrates scRNA-seq data, a broadened chemical perturbation database, and dynamic gene co-expression networks to enable pathway-specific compound selection via effect score calculations using a random walk-based module partitioning algorithm, scRCF identifies key signaling proteins essential for cell fate transformation. This pipeline, further validated by DRUG-seq2, enhances predictive accuracy and reprogramming efficiency. Compared to SiPer, scRCF offers superior capabilities in dynamically integrating signaling networks, refining small molecule prioritization, and enabling experimental feedback, thereby improving both precision and stability.

Based on our predictive platform, we established a two-stage chemical reprogramming strategy for converting both mouse and human fibroblasts into RPE cells. In the mouse system, the initial stage involved LDN193189, A 83-01, CKI-7, Hh-Ag1.5, CHIR-99021, BMS-345541, and RG108, which facilitated neuroectodermal induction and EF/OV-like transitions. This was followed by a shared maturation stage (M3) using NIC, RA, and Activin A to drive RPE differentiation. For human fibroblasts, an extended cocktail was required by adding R-268712, BIX-01294, VPA, and SB-431542 to overcome chromatin-related reprogramming barriers and facilitate lineage progression.

The key small molecules contributed to the regulation of transcription, signaling pathways, and epigenetic remodeling. Hh-Ag1.5 activated the SHH pathway and induces TFs such as Bmi1, Sox2, and N-Myc29,58,59,60,61; LDN193189, a BMP inhibitor, promoted, and neuroectodermal induction29,62; RG108, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, relieved DNA methylation-mediated silencing and improved transcriptional accessibility63. BMS-345541 inhibited NF-κB signaling to reduce apoptosis and support reprogramming64,65. and CHIR-99021, a GSK-3β inhibitor, activated the Wnt/β-catenin signaling to enhance proliferation and differentiation66,67,68. In human cells, epigenetic regulators such as VPA, BIX-01294, and SB-431542 further increased chromatin accessibility and promoted lineage conversion63,69,70,71. The maturation stage compounds—NIC, RA, and Activin A—were selected based on established protocols and previous organoid studies to promote the final transition from EF/OV-like cells to mature, functional RPE. The use of certain small molecules in our study—such as Hh-Ag1.5, LDN193189, and CHIR-99021—overlaps with compounds previously applied in neuroectodermal induction or reprogramming. This convergence likely reflects the shared developmental origin of RPE and neural lineages. Crucially, these molecules were not selected arbitrarily but systematically prioritized and validated by our prediction platform from a large candidate pool, underscoring the accuracy and biological relevance of our strategy. Moreover, we identified molecules such as BMS-345541 and CKI-7 as novel functional contributors in RPE reprogramming, offering new potential targets for future mechanistic exploration.

Although we achieved high-efficiency ciRPE induction in the mouse system and demonstrated preliminary therapeutic effects in RD model—including host integration and partial restoration of visual function—these effects remain limited to a specific preclinical context. The long-term safety, immune compatibility, and functional stability of transplanted cells require further systematic evaluation through extended in vivo studies to support future clinical translation.

In contrast, the efficiency of ciRPE induction from human fibroblasts remains relatively low, which limits its immediate scalability for clinical-grade cell production. Several factors may underlie this challenge. One major consideration is the lack of high-quality single-cell RNA-seq datasets from early EF stages, which constrained our predictive model to rely on OV data as a surrogate reference. While organoid-derived OV datasets expanded the framework, their relatively late developmental timing may have reduced prediction resolution and reprogramming efficiency. In addition, primary HEFs are inherently heterogeneous in epigenetic state, transcriptional networks, and lineage potential, which likely contributes to variable chemical responses and divergent reprogramming trajectories. Moreover, although several small molecules effective in the mouse system were incorporated into the human cocktail, the overall efficiency remained suboptimal, pointing to species-specific differences in signaling dependencies and reprogramming routes.

These observations highlight both the opportunities and the challenges of extending chemical reprogramming to human fibroblasts. Overcoming these barriers will require more refined characterization of human fibroblast subpopulations, deeper understanding of their lineage plasticity, and optimization of small-molecule combinations tailored to human-specific regulatory landscapes. Advancing along these directions may ultimately enable scalable and clinically relevant generation of RPE and other retinal lineages from adult autologous cells for personalized regenerative therapies. In conclusion, this study outlines an innovative, gene-editing-free, and efficient two-stage approach using a small-molecule cocktail to convert fibroblasts into functional RPE cells. Our single-cell transcriptomics-based platform enabled the precise identification of optimal small molecules for enhancing reprogramming. Functional and mechanistic analyses revealed core TFs driving RPE conversion, and successful ciRPE cell transplantation in RD models demonstrated their therapeutic potential. These findings advance our understanding of cellular reprogramming mechanisms and open new avenues for developing safe, scalable, and effective regenerative therapies targeting RD diseases.

Methods

Human tissues

The primary HEFs and primary hRPE cells used in this study were isolated from donated tissues of 16- and 18-week embryos, with the research approved by the Ethics Committee of the Eye Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (Research License 2021-238-k-208-01). Informed consent forms were prepared in compliance with ISSCR guidelines for fetal tissue donation. All donors provided written informed consent and willingly contributed fetal tissue samples after deciding to undergo legal pregnancy termination. All experimental procedures adhered to the Regulations on the Management of Human Genetic Resources of the People’s Republic of China.

Animals

The Best1-Cre [C57BL/6-Tg (BEST1-cre)1Jdun/J], Fsp1-cre [BALB/c-Tg (S100a4-cre)1Egn/YunkJ], and ROSA26-tdTomato [B6. Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J] mice were obtained from the Jackson laboratory. C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Jiangsu GemPharmatech, while 129S4/SvJae and BALB/c- Nude mice were sourced from Shanghai Vital River Laboratory. RCS rats, a well-recognized and classical animal model of RD, were kindly provided by Professor Guoping Fan. Animals were randomly assigned to experimental groups regardless of sex, as no sex-specific differences were anticipated in the context of this study. All experimental animal strains underwent genotype verification prior to breeding and were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle, ambient temperature of 22 ± 2 °C, and relative humidity of 50–60%. Efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used. All procedures conducted on these animals were in compliance with ethical animal license protocols and received approval from the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Wenzhou Medical University (Research License wydw2024-0200).

Predicting and screening small molecules using scRCF

This scRCF pipeline consists of three parts: 1. Screen signal proteins and network based on SiPer; 2. Two-step optimization for small molecule prioritization; 3. Refinement and validation of predicted small molecules.

Screen signal proteins and network based on SiPer

The scRCF pipeline requires single-cell data from the initial and target cell types. Differentially expressed transcription factors (DETFs) are identified using Seurat (v4.3.0 or v5.1.0)72. The processing steps include creating a Seurat object, integrating scRNA-seq data, normalizing the data, identifying differentially expressed genes, and selecting TFs with an absolute avg_log2FC > 1 and an adjusted p value < 0.05. The list of TFs, including TFs and co-factors, is obtained from the AnimalTFDB (3.0) database73. The expression of DETFs is booleanized based on their regulation status relative to the initial cell type, with up-regulation assigned as 1 and down-regulation as −1.

Signal networks and candidate signaling proteins were identified using SiPer19, with binarized differentially expressed TFs as input. SiPer incorporates three built-in prior knowledge databases: a small molecule perturbation database, a small-molecule target database, and a signaling network. The small molecule perturbation database was constructed from the LINCS L1000 database (level 5)74, retaining signatures within six hours post-perturbation in normal or primary cell lines19,74. Only TFs were included, with regulation statuses assigned as +1 for up-regulation and −1 for down-regulation based on z-scores. This database contains 5570 entries of small molecule treatment information. The small-molecule target database integrates data from the Drug Repurposing Hub75, STITCH v5.076, and MedChemExpress (www.medchemexpress.com). For STITCH, only protein targets with a confidence score > 0.4 were retained. Interaction values between small molecules and targets were assigned as follows: 1 for activation, −1 for inhibition, and 2 for unknown. The database contains 4389 small molecules and 46,493 interactions. The signaling network is based on the prior knowledge network described by Zheng et al.19, including signal proteins, TFs, and hierarchical network information. Using SiPer, the input TFs are integrated into the signaling network, producing outputs that include signal proteins, TFs, and signaling proteins (candidate SPs) identified as critical drivers of chemical reprogramming.

Two-step optimization for small molecule prioritization

Community partitioning using short random walks. Community partitioning identifies groups of functionally similar proteins, allowing the targeting of only a subset of these proteins to achieve desired effects77. A random walk method is used to detect communities within the signaling network. Initially, each node is treated as an independent community. A fixed-length random walk is then simulated, where the walker transitions from the current node to a randomly selected neighboring node. The transition probability is defined as the likelihood of signal transmission. The similarity between node pairs is assessed by calculating the transition probability during the random walk. The distance measure \({{{\rm{r}}}}_{{{\rm{ij}}}}\) is defined as:

where \({P}_{{ik}}^{t}\) represents the probability of transitioning from node \(i\) to node k in a t-step random walk. Nodes or communities with high similarity are merged iteratively until a stopping condition is met, set here as four merges. The post-merge community distance is defined as:

where \({P}_{C1k}^{t}\) is the probability of transitioning from community C1 to node k in a t-step random walk, averaged over all nodes in the community. Gain the community partitioning results of the graph. This process produces a partitioned graph, with signal proteins assigned to specific communities.

Prioritizing candidate small molecules. Based on the community partitioning results, an effect score is calculated for each small molecule in the small-molecule target database. The effect score is defined as:

where C represents the communities affected by the small molecule, and the indicator function is defined as:

Here, D denotes the mode of action of the small molecule on a protein in the database, and P denotes the influence mode of the signaling protein. Small molecules with an effect score of 0 are then removed, yielding a refined list of candidate small molecules.

Selection of signal pathways. Small molecules achieve cell identity transitions by influencing signal transduction and epigenetic signaling pathways78. To refine signal pathway classifications, we referred to the KEGG and Reactome79 databases, which provide detailed categorizations of signal transduction pathways. Additionally, we incorporated classification information from the compound supplier (MedChemExpress) to standardize pathway classifications across these databases. Based on this integration, we identified the 10 most relevant signal pathways for reprogramming. Signal pathways were further subdivided based on specific molecular mechanisms and reaction steps (Supplementary Table 3), creating correspondences between pathways and their sub-pathways. Information on small molecule drugs, along with their associated signaling and sub-pathway classifications, was compiled using data from compound suppliers (Supplementary Data 9). Then, the effect score is normalized:

where ES denotes the effect score of each drug, and \(\max ({{ES}}_{{pathway}})\) represents the highest ES value in the pathway corresponding to the small molecule compound. Finally, retain the small molecule with the highest effect score within the sub-pathways of each signaling pathway classification. Output the list of candidate small molecules.

Refinement and validation of predicted small molecules

(Proceed with DRUG-seq2 and analysis.).

Isolation and culture of primary HEFs

HEFs were isolated as previously described80,81. Briefly, fetal skin tissue (2–4 cm²) was washed twice with Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS, Gibco, c14190500cp) containing 2% Penicillin-Streptomycin (P/S, 10,000 U/mL, Gibco,15140122), then cut into 1–2 mm² pieces and digested with 2 mg/mL Collagenase IV (Gibco, 17104019) at 37 °C for 1 h. Digestion was then terminated by adding 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biological Industries, 04-001−1ACS) and 2% P/S to high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco, C11995500bt). The suspension was collected into a 50 mL tube, allowed to stand for 10–15 min, and the supernatant containing single-cell suspensions was transferred to a cell culture dish for cultivation. After the cells adhered the next day, the medium was replaced with fresh growth medium. HEFs were then cultured in DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS, 1% P/S, 1% MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids (NEAA, Sigma-Aldrich, M7145-100ML), 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco, 35050061), and 0.055 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol (Gibco, 21985023).

Isolation and culture of primary human RPE cells

For isolation of primary hRPE cells, the dissected eye tissue was washed twice in PBS containing 2% P/S, and the anterior segments and surrounding connective tissue were removed, leaving the eyecup. Using fine tweezers, the RPE layer was separated from the neural retina and incubated in Dispase solution (0.5–1.0 mg/mL, CORNING, 534253) containing 50 μg/mL DNase Ⅰ (Roche, 11284932001) at 37 °C for 45 min. After incubation, the eyecup was gently shaken to release RPE cells, and further digestion with 0.25% trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 25200056) was performed if necessary. The cell suspension was collected, centrifuged, and resuspended in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12/GlutaMAX (DMEM/F-12/GlutaMAX, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10565042) supplemented with 20% FBS and 1% P/S. Cells were then plated onto Matrigel-coated (CORNING, 354234) culture plates and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO₂. The medium was changed every 2–3 days until the cells reached confluence.

Cell isolation and culture from mice

Primary MEFs were derived from E13.5 mouse embryos with genetic backgrounds including C57BL/6J, 129S4/SvJae, Best1-Cre/ROSA26tdTomato (generated by crossing Best1-Cre mice with ROSA26 tdTomato mice), and Fsp1-Cre/ROSA26tdTomato (generated by crossing Fsp1-Cre mice with ROSA26 tdTomato mice), following standardized protocols16. Specifically, neural tissues (including the brain, spinal cord, and tail), limbs, gonads, and visceral organs were carefully removed and discarded prior to the isolation of MEFs. The remaining tissues were then finely minced, enzymatically dissociated using trypsin, and plated onto 10-cm culture dishes in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% MEM NEAA.

The extraction of Tail-Tip Fibroblasts (TTFs) was carried out following established protocols52. Tail tips (approximately 0.3 mm) from 3-week-old mice were collected, minced, enzymatically digested with trypsin, and subsequently cultured in MEF medium to isolate TTFs.

The protocol for isolating and culturing primary mouse RPE cells was optimized based on previous research82,83. Briefly, eyes from 8–12-week-old C57BL/6J mice were dissected under a microscope. The eyes were then transferred to a dish containing DPBS supplemented with 1% P/S. The surrounding connective tissue and anterior segment were carefully removed, and the retina was delicately peeled from its internal attachment to the optic nerve using fine tweezers, ensuring the RPE layer remained intact within the eyecup. The eyecup was subsequently placed into a 24-well plate and incubated with dispase I (Sigma-Aldrich, D4818) for 45 min. The plate was gently agitated to facilitate the detachment of RPE cells from the eyecup. Detached RPE cells were then transferred to a Matrigel-coated culture plate and resuspended in complete medium (DMEM + 15% FBS + 2% P/S).

Generation of ciRPE cells from MEFs using a two-stage chemically defined reprogramming protocol

M7 reprogramming medium (RM) preparation

Equal volumes of Neurobasal (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 21103049) and DMEM/F12/GlutaMAX supplemented with 1% N2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 17502048), 1% B27 supplement without vitamin A (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 12587010), 7.5% BSA (Solarbio, H1130), 1% NEAA, 1% P/S, bFGF (10 ng/ml, PeproTech, 100-18B) and the small molecules CHIR-99021 (3 μM, MCE, HY-10182), LDN193189 (0.1 mM, Selleckchem, S2618), A 83-01 (0.5 mM, Selleckchem, S7692), Hh-Ag1.5 (0.5 mM, Xcess Biosciences, M60004-10S), RG108 (10 μM, Selleckchem, S2821), BMS-345541 (0.2 mM, MCE, HY-10519) and CKI-7 (5 μM, Sigma-Aldrich, C0742).

M3 differentiation and maturation medium (DM) preparation

DMEM/F12/GlutaMAX supplemented with 10% KSR (Gibco, 10828010), 1% NEAA, 1% P/S, 0.055 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, Y27632 (10 μM, Selleckchem, S6390) and Nicotinamide (NIC, 10 mM, Sigma-Aldrich, 47865-U), Retinoic acid (RA, 1 μM, Sigma-Aldrich, R2625), Activin A (0.2 mM, MCE, HY-P70311).

ciRPE maintenance medium preparation

ciRPE maintenance medium includes proliferation medium and function-maintaining medium. The proliferation medium consisted of DMEM/F12/GlutaMAX supplemented with 1% N2, 2% B27 without vitamin A, 1% NEAA, 1% P/S, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 ng/mL bFGF, 20 ng/mL EGF (Gibco, PMG8045), 10 μM Y27632, and 0.5 μM A 83-01. The function-maintaining medium consisted of DMEM/F12/GlutaMAX supplemented with 1% N2, 2% B27 with vitamin A, 1% NEAA, 1% P/S, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.2 μM Activin A, 0.5 μM RA, 1 μM BMP4, and 10 mM NIC.

All small molecules were dissolved and diluted in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, D4540) following the manufacturer’s instructions and are detailed in Supplementary Data 10.

Stage I: Chemical conversion of eye-field cells from MEFs

-

(1)