Abstract

Antimicrobial host defense peptides are promising alternatives to resistance prone small molecule antibiotics. To overcome the poor physiologic stability of these therapeutic candidates it is common to prepare proteolytically resistant retro-inverso analogues, where sequence backbone direction and amino acid chirality are reversed. However, in many cases, gains in stability are offset by altered assembly propensities and reduced biologic potency. Here, we show that, contrary to the dogma for non-mycobacterial pathogens, retro-inversion of antimycobacterial host defense peptides improves their potency, specificity and host safety; in some cases by more than an order of magnitude. Biophysical assays suggest that altered mycomembrane thermodynamics, instead of improved proteolytic stability, plays a causative role in retro-inverso mediated potency gains. Additional bacteriologic assays using a lead retro-inversed candidate, MAD1-RI, demonstrate this analogue rapidly sterilizes replicating cultures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is effective towards drug-resistant clinical isolates of the pathogen, and synergistically enhances the activity of co-incubated antibiotics. Transcriptomic studies uncover complementary membrane destabilizing and metabolic mechanisms of antitubercular action for MAD1-RI, and in doing so identify sequence retro-inversion as a simple, but powerful, modality in the de novo design of non-natural antimycobacterial peptides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mycobacterial lung and disseminated infections arise from several species of environmental and pathogenic mycobacteria. While M. tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of Tuberculosis (TB), has been studied for centuries, non-tuberculous mycobacteria are emerging pathogens that also cause pulmonary and soft tissue infections, particularly in cystic fibrosis and immunocompromised patients. Increasing global incidence of both tuberculous and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections, in addition to their acquisition of pan-drug resistance1, has urged the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Peptide antibiotics, particularly host-defense peptides (HDPs), are promising alternatives to traditional small molecule antibiotics in treating drug-resistant infections2. For example, colistin (polymyxin E) is now a drug of last resort against pan-resistant, gram-negative bacteria in clinical settings3. Due to the diversity of HDP modes of action, which are mechanistically distinct from classical small molecule antibiotics, phenotypic resistance towards HDPs is expected to require significant cell surface remodeling and so present a high mutational barrier4. In fact, despite millennia of exposure to HDPs as part of innate immune responses, widespread acquisition of resistance has not yet been documented. Indeed, antimicrobial peptides have co-evolved with bacterial pathogens, leading to a diverse array of membrane-lytic HDPs produced across species5,6, habitats7, and time8,9.

Yet, natural HDPs are limited to the twenty canonical, L-chiral, amino acid building blocks, thereby making them proteolytically unstable. Sequence retro-inversion, where both backbone direction (retrosynthesis) and amino acid chirality (inversion) are reversed, represents an attractive strategy to impart innate protease resistance to HDPs, while maintaining side chain topology10,11. However, nearly four decades of research have shown that gains in peptide stability from retro-inversion often come with a penalty of decreased biologic activity due to altered secondary structure, end-group presentation and self-assembly propensity12,13,14,15.

Here, we show that, contrary to the prevailing paradigm observed in non-mycobacterial pathogens, retro-inversion of HDPs improves their potency by nearly an order of magnitude towards mycobacteria. Bacteriologic assays suggest this enhanced potency is only realized for mycobacterial targets, and that retro-inversion does not appreciably change HDP toxicity towards non-mycobacterial species. Consequently, the lead retro-inverted HDP, referred to as MAD1-RI, is capable of sterilizing replicating Mtb cultures, synergistically enhances the activity of clinical TB antibiotics, and is effective towards drug-resistant clinical Mtb isolates. Through a series of biochemical, biophysical, and transcriptomic analyses, we shed light on the mechanistic basis of this enhanced activity, and demonstrate that gains in potency operate through altered mycomembrane thermodynamics of retro-inverted sequences. Thus, we identify retro-inversion as a potentially unique driver of anti-mycobacterial specificity in the design of HDPs that utilize mechanisms distinct from the traditional dogma of increased proteolytic stability.

Results

Bacteriologic screening of retro-inverted sequences

To explore the bacteriologic effects of retro-inversion we began by chemically modifying the model antimycobaterial peptide, MAD1 (mycomembrane-associated disruption sequence 1)16. MAD1 exerts antitubercular activity through disruption of the mycolic acid rich outer mycomembrane, putatively due to its structural mimicry of the mycobacteria specific porin MspA. Inhibition assays utilizing a series of Mtb complex strains (M. bovis BCG, mc2 6230, mc2 7901, H37Ra, and H37Rv) and non-tuberculous mycobacteria (M. smegmatis and M. abscessus) show that retrosynthesis (backbone reversal, MAD1-R) or chiral inversion (enantiomerization, MAD1-I) of MAD1 did not, individually, alter minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the analogues relative to the parent sequence (Table 1; see Supplementary Table S1 for peptide mass and purity). Conversely, the combination of these features, producing MAD1-RI, resulted in a significant improvement in MIC against several of the tested mycobacteria relative to native MAD1. For example, single digit micromolar MICs were recorded for MAD1-RI against M. smegmatis, M. bovis and Mtb (H37Ra, mc2 6230). Against the virulent Mtb strain H37Rv, MAD1-RI demonstrated an MIC of 40 µM, while the native MAD1 was weakly active (MIC > 40 µM). MAD1-RI was similarly effective against a panel of drug-resistant clinical Mtb isolates (PMID: 30908506), with MICs ≤ 40 µM (Supplementary Table S2).

All four MAD1 sequences were subsequently counter screened against the non-mycobacterial pathogens, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), P. aeruginosa, and A. baumanii to assess mycobacterial selectivity. A selectivity index (SI, see Table 1) was then calculated to quantitatively compare microbial specificity. Remarkably, retro-inversion yielded a > 16-fold increase in mycobacterial selectivity (MAD1-RI SI = 32) relative to the MAD1, MAD1-R, and MAD1-I peptides (SI = 1 – 2). Finally, safety of the MAD1 and MAD1-RI sequences were compared by measuring their half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) against A549 human lung epithelial cells, and subsequently calculating a toxicity index (TI, see Table 1). Gratifyingly, retro-inversion decreased the peptide’s toxicity, increasing the TI from 5.3 for the native sequence to 368.4 for MAD1-RI; nearly two orders of magnitude improvement. MAD1-RI was similarly biocompatible towards human macrophages (Supplementary Fig. S1).

To evaluate the impact of proteolytic stability on MAD1-RI activity we performed degradation assays in the presence of proteinase K, a particularly promiscuous and aggressive protease (Fig. 1a). Chromatographic results show that, as expected, backbone reversal alone (retrosynthesis, MAD1-R) did not enhance the proteolytic stability of the parent sequence, with both showing near complete digestion after 1 hour. Conversely, amino acid enantiomerization (inversion, MAD1-I) yielded a sequence that was highly resistant to proteolysis under the tested conditions, which was conserved when combined with retrosynthesis to produce MAD1-RI. Additional time-dependent stability studies in the presence of Mtb-secreted proteases indicate that native MAD1 was completely proteolyzed after 14 days (Fig. 1b), while MAD1-RI generally remained stable up to two weeks in culture (Fig. 1c). A similar outcome was observed in the presence of human serum proteases (Supplementary Fig. S2). Taken in context with our MIC results, these findings indicate that enhanced proteolytic stability, alone, does not explain the significantly greater antimycobacterial potency of the retro-inversed MAD1-RI peptide, as typical dogma suggests. Instead, later studies indicate altered thermodynamic stability of retro-inverted sequences in the unique mycolate membrane of Mtb may play a causative role.

a High-pressure liquid chromatograms of the indicated peptide (100 μM) following a 1 h incubation in the absence (black) and presence (red) of proteinase K. Stability of MAD1 (b) and MAD1-RI (c) over two weeks of incubation in the proteolytic Mtb (mc2 6230) supernatant. Representative spectra shown from n = 3 technical replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next set out to assess whether these mycobacterial-specific effects represent a conserved phenomenon of retro-inversion across membrane-active HDPs. To test this, we prepared five pairs of native peptides and their retro-inverted counterparts (see Table 1), which include two analogues of MAD1 identified through artificial intelligence guided screening (MAD2.2, MAD5.1)17 and three antimicrobial sequences isolated from insect venoms (Latarcin 3a18, Eumenitin F19, Pinipesin20). Three of the retro-inverted peptides, MAD2.2-RI, Latarcin 3a-RI and Eumenitin F-RI, showed a marked enhancement in activity relative to the native sequence across most mycobacterial cultures studied; in some cases improving activity by 16 times. MAD5.1, on the other hand, showed no improvement following sequence retro-inversion. This may be a consequence of its high formal charge (+8), where cationic membrane depolarization, and subsequent detergent-like destabilization, by the peptide may be insensitive to retro-inversion mediated conformational changes. Additionally, we observed no significant antibacterial activity of the centipede derived Pinipesin peptide across all tested species. Collectively, our studies suggest that retro-inversion may represent a broadly applicable design strategy to enhance the antimycobacterial activity of HDPs, which operate through mechanism(s) independent of enhanced proteolytic stability. We further explore this assertion through a series of conformational assays performed in both model systems and mycobacterial membranes.

Conformational consequences of peptide retro-inversion

Circular dichroism (CD) was employed to establish the secondary structure of the four conformational MAD1 variants in pH 7.4 phosphate buffer (Fig. 2a, b). As previously reported, MAD1 displays mixed α-helical (minima at 206 nm and 219 nm) and β-sheet (minima at 212 nm) conformations under physiologic conditions16, with an unusual exciton band at 228 nm indicative of a tryptophan zipper21,22. As expected, MAD1 and MAD1-I (Fig. 2a), as well as MAD1-R and MAD1-RI (Fig. 2b), congeners display mirrored CD spectra as a result of residue enantiomerization. Unexpectedly, although the spectra of MAD1 and MAD1-I show the putative tryptophan zipper signal at 228 nm, the retro-synthetic MAD1-R and MAD1-RI analogues have lost this feature. This suggests backbone reversal may alter residue side chain orientation and disrupt tryptophan-mediated peptide assembly. Additional in silico conformational analyses utilizing the BeStSel algorithm23,24,25 show that MAD1 and MAD1-RI possess similar anti-parallel β-sheet content, with accompanying turn-like arrangements, in low ionic strength conditions (Fig. 2c). However, nearly 50% of the spectra for both sequences are ascribed to disordered conformations (other), suggesting significant conformational flexibility that may potentiate varied and environmentally sensitive self-assembly phenotypes.

CD spectra of MAD1 and MAD1-I (a), or MAD1-R and MAD1-RI (b), in phosphate buffer. c Secondary structure assignment for the MAD1 (top) and MAD1-RI (bottom) peptides. Structural classification was performed using the Beta Structure Selection (BeStSeL) algorithm. d–i Left: Full CD spectra and Right: Ellipticity changes for the β-sheet (θ212nm) and tryptophan-zipper (θ228nm) structural features, for MAD1 (d, f, h) and MAD1-RI (e, g, i) as a function of SDS concentration (d, e), NaCl concentration (f, g) and temperature (h, i). Representative spectra and analyses produced from n = 3 technical replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Based on this observation, we next compared the structural dynamics of MAD1 and MAD1-RI in the presence of increasing concentrations of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) micelles, a common model for anionic lipid membranes (Fig. 2d,e). In the absence of SDS, MAD1 displays intense exciton-coupled bands at 212 and 228 nm, indicative of long-range assembly. This is significantly disrupted in the presence of SDS, with plots of the concentration-dependent change in ellipticity showing that MAD1’s β-sheet (θ212nm) and tryptophan-zipper (θ228nm) structures are nearly completely abolished in the presence of ≥1 mM SDS (Fig. 2d, right). MAD1-RI, on the other hand, was significantly more conformationally rigid, showing only minor changes in structural states up to 90 mM SDS (Fig. 2e). Parallel studies performed in the presence of the Mtb cell envelope glycolipid, trehalose dimycolate, showed a comparable trend, with MAD1 becoming more disordered and MAD1-RI conversely adopting greater structural order (Supplementary Fig. S3). Finally, CD experiments conducted under varying ionic strength (Fig. 2f,g) and temperature (Fig. 2h,i) conditions displayed a similarly contrasting conformational behavior. Remarkably, MAD1-RI maintains its secondary structure even at temperatures as high as 95 °C (Supplementary Fig. S4), suggesting significant secondary structural stability. Taken together, our ex cellulo results suggest that retro-inversion leads to greater conformational rigidity of the MAD1 peptide in physiologic solutions. This, in turn, may lower the entropic barrier to interpolation and assembly of the sequence within mycomembranes, thereby enhancing its antimycobacterial potency. Using a series of cell based and biophysical assays, we next test this assertion in the context of living mycobacteria bacilli.

Fluorescent confocal and electron microscopy were initially utilized to probe MAD1-RI localization to the Mtb cell surface, as well as investigate peptide-mediated morphologic changes in myco-envelope architecture. Fluorescence micrographs shown in Fig. 3a demonstrate that the peptide rapidly engages the Mtb cell wall and co-localizes with outer membrane mycolic acids (Fig. 3b), with greater mycomembrane accumulation relative to the parent MAD1 sequence (Supplementary Fig. S5). When employed at sub-lethal concentrations (0.5x MIC), the outer membrane interactions of MAD1-RI cause the typically smooth Mtb surface to adopt a ruffled morphology (Fig. 3c). Increasing peptide concentration to 5x MIC led to further ruffling of the pathogen outer membrane, which was complemented by the presence of extracellular aggregates; presumably released intracellular contents, as was observed previously for MAD116. Close inspection of the Mtb cell surface revealed the formation of MAD1-RI nano-assemblies (Fig. 3d), indicating the pore-formation capabilities of MAD1 have been maintained after retro-inversion. Complementary transmission electron microscopy demonstrated that exposure to these MAD1-RI assemblies at 1x and 5x MIC led to significant cell wall disruption and mycomembrane blebbing, with complete breakdown of envelope integrity and cytoplasmic condensation observed at 25x MIC (Fig. 3e).

a Fluorescent micrographs of Mtb (mc2 6230) co-stained with auramine-O (green) and Cy5-labeled MAD1-RI (red). Individual channel and merged image shown. Scale bar = 25 µM. b Fluorescent intensity line plot of the mycolic acid and MAD1-RI signals from the region delineated by the dashed yellow line in panel a, merged. c Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) of Mtb (mc2 6230) treated with varying concentrations of MAD1-RI (as indicated at the top left corner). Scale bar = 1 µM. d False colored SEM highlighting MAD1-RI assembled structures (tan) at the Mtb cell surface. e Transmission electron micrographs of Mtb (mc2 6230) treated with varying concentrations of MAD1-RI (as indicated at the top left corner). Yellow stars indicate MAD1-RI mediated cell wall thinning/disruption, budding and cytoplasmic condensation, the latter represented as an electron-transparent halo. Scale bar = 100 nm. Inset: Visualization of Mtb inner (IM) and outermembrane (OM) structures. Scale bar = 20 nm. SAXS data with model fit (f) and P(r) (g) plots for MAD1 and MAD1-RI. h Simulated molecular weights of MAD1 and MAD1-RI species obtained by AUC. i Putative arrangement, based on SAXS and AUC simulations, of MAD1 and MAD1-RI within a scaled schematic of the mycobacterial outer membrane. Representative images and spectra shown from n = 3 biologic replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further interpret the nature of these assemblies, and better understand how conformational plasticity of the peptides may contribute to their membrane-dependent assembly phenomena, small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and analytical ultracentrifugation studies were designed. SAXS curves shown in Fig. 3f demonstrate that MAD1-RI adopts a more extended and enlarged conformation relative to MAD1, with a radius of gyration (Rg) and maximum dimension of 8.2 and 22.2 Å for MAD1 and 10.2 and 30.6 Å for MAD1-RI, respectively (SAXS data collection table found in Supplementary Table S3). This further supports our assertion that MAD1-RI is more conformationally rigid than the parent sequence. A double maximum observed in the P(r) SAXS curves (Fig. 3g) suggests that both peptides adopt an ensemble of homodimeric conformers. Analytical ultracentrifuge (AUC) analyses confirmed this observation and demonstrated a dimeric species for both peptides in physiologic solution (Fig. 3h). Curiously, the predicted molecular weight of the MAD1-RI dimer was ~300 Da larger than the MAD1 dimer, despite their identical true molecular weight. It is possible this difference is due to changes in the hydration shell and bound ions for the MAD1-RI dimer assembly. Further SAXS experiments performed in the presence of SDS yielded a model of peptide assembly that suggests MAD1 adopts a head-to-head dimer, while MAD1-RI associates head-to-tail (Fig. 3i). This MAD1-RI dimer conformation would span approximately 3 nm in its longest dimension, 1 nm larger than the prediction for MAD1 dimers. Importantly, the head-to-tail alignment of MAD1-RI dimers may allow propagation of these conformers to completely span the ~8 nm thickness of the outer Mtb mycomembrane. Thus, compared to MAD1, MAD1-RI may more readily associate into a pore that spans the Mtb outer membrane and potentiate the leakage of intracellular contents; further corroborating the extracellular aggregates observed during SEM microscopy (Fig. 3d).

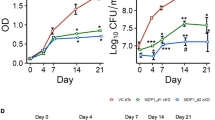

Antitubercular activity of MAD1-RI

We next evaluated time dependent killing of Mtb by MAD1-RI, in both proliferating and non-proliferating TB cultures. Initial studies confirmed that, at equivalent concentrations, MAD1-RI showed a ~ 4-log greater anti-TB efficacy relative to MAD1 (Fig. 4a). Additional kinetic growth assays demonstrated that the Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC, >99.9% reduction in colony forming units) of MAD1-RI towards Mtb was twice its MIC at ~80 µM (Fig. 4b) and complete culture sterilization occurred at 4x MIC (160 µM) between 7 and 14 days of exposure (Fig. 4a, b). This sterilizing activity was not achieved by clinically relevant doses of the front-line drugs Isoniazid and Rifampicin, which, despite a ~ 2-log reduction in the first week of exposure, permitted regrowth of treated Mtb cultures at 3 and 10 days of incubation, respectively (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. S6). Additional tolerance studies, in which Mtb was serially passaged in the presence of sub-MIC concentrations of drug, demonstrated that the pathogen was unable to gain resistance to MAD1-RI over 10 passages (Supplementary Fig. S7). Conversely, Isoniazid treated samples showed nearly an order of magnitude reduction in effective MIC90 of the drug relative to the initial culture. These results suggest that, unlike traditional small-molecule antibiotics, the diverse membrane-targeting mechanisms of MAD1-RI may impose a high mutational barrier for resistance acquisition that may be difficult for Mtb pathogens to overcome.

a Time-dependent kill kinetics of MAD1 and MAD1-RI in proliferating Mtb (H37Rv) cultures. Rifampicin included as a representative antibiotic control. b Concentration-dependent antimycobacterial efficacy of MAD1-RI (MBC = 80 µM). c Fractional inhibitory concentration plots of MAD1-RI and the indicated antibiotic. Independent, Additive and Synergistic fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) scoring regions are highlighted. Time-dependent kill kinetics of MAD1-RI, MOX or combination in (d) proliferating, (e) nutrient starved and (f) hypoxic Mtb cultures (H37Rv for (d, e); H37Ra for (f). Data in (a, b, d–f) reported as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance from n = 3 biologic replicates for each treatment condition, relative to untreated controls, in (a, b, d) is reported in Supplementary Table S4, (e) in Supplementary Table S5, and (f) in Supplementary Table S6. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, combinatorial studies were performed to identify potential synergistic pairings of MAD1-RI and clinical TB antibiotics (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. S8). Fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) scores show that MAD1-RI did not antagonize the activity of any of the tested antibiotics, and for the majority of candidates, acted independently or in an additive fashion. Two antibiotics, Moxifloxacin (MOX) and Meropenem, displayed synergistic activity with MAD1-RI (FIC score ≤ 0.5). MOX is a second-line fluoroquinolone commonly used to treat drug-resistant TB, and therefore, this drug was prioritized for follow up combinatorial kill kinetic studies. In proliferating Mtb (Fig. 4d), the co-incubation of MAD1-RI (40 μM) and MOX (0.62 μM) leads to complete sterilization of the culture after two weeks of incubation, which represents a ~ 6-log enhancement in activity relative to the monotherapy controls. We next performed similar Mtb kill kinetics studies under nutrient starvation (Fig. 4e) and hypoxic (Fig. 4f) conditions, which causes the pathogen to adopt a quiescent, non-replicating state in the phagosomes of infected macrophages within granulomatous lesions. This metabolically inactive state promotes persistence of the pathogen by rendering it phenotypically resistant to most antibiotics. This was confirmed in our experimental models, where under nutrient starvation and hypoxic conditions, Isoniazid was inactive (Supplementary Fig. S9), and the efficacy of MOX significantly blunted (Fig. 4e,f). Conversely, we hypothesized that MAD1 peptides would remain active under these conditions due to the insensitivity of its mycomembrane destabilizing mechanism of action to the pathogen’s metabolic state. Results shown in Supplementary Fig. S10 confirm this assertion, and again show enhanced activity of MAD1-RI relative to MAD1 toward persister Mtb. As expected, the combination of MAD1-RI and MOX showed more effective killing than the individual therapies in nutrient starved Mtb cultures (Fig. 4e). However, under hypoxic conditions, the combinatorial formulation was equal in its efficacy to MOX alone and was significantly less active than the anaerobic positive control drug Metronidazole (Supplementary Fig. S9b). Notably, although effective in vitro, metronidazole lacks efficacy in in vivo TB models due, at least in part, to insufficient anaerobic conditions to allow reductive activation of the drug26. Finally, intracellular kill assays in Mtb-infected human macrophages demonstrated that MAD1-RI exposure reduced the mean bacilli burden by ~1 log at four days of incubation, relative to untreated samples (Supplementary Fig. S11). However, the peptide was unable to match the efficacy of the Isoniazid positive drug control at longer incubation time points. Taken together, our results show that MAD1-RI demonstrates moderate efficacy towards non-replicating Mtb persisters, and suggests that modulation of particular metabolic pathways during intracellular dormancy may blunt the antimycobacterial activity of the peptide; an assertion further explored through genomic studies.

MAD1-RI antimycobacterial mechanisms

To characterize the transcriptional response to MAD1-RI exposure, H37Rv Mtb cultures were treated for 24 h with 25 µM of the peptide, before performing RNA sequencing. These studies employed sub-MIC concentrations of the peptide to avoid artifactually skewing RNAseq results by Mtb cell death. Log2 fold change data shown in Fig. 5a demonstrates that 16 genes were induced and 7 genes repressed (>1-fold, q < 0.05, principal components analysis shown in Supplementary Fig. S12). Within the upregulated data set, the five-gene operon espACD-Rv3613c-Rv3612c is particularly notable given its required role in ESX-1 secretion, which is essential for Mtb virulence and host cell survival27. Additionally, induction of the PE20 gene encodes for the PPE20 protein, which forms a complex with PE15 to facilitate molecular transport across the Mtb cell envelope28. Finally, MAD1-RI also induced Rv1057, which is proposed to be upregulated in response to envelope stress caused by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) exposure and stabilizes MmpL3 complexes that shuttle lipid components to the cell wall29. Thus, it was hypothesized that MAD1-RI treated Mtb would exhibit increased sensitivity to membrane-targeting agents, such as detergents like SDS. Indeed, after 24 h of drug treatment, survival differences were observed between treated and untreated cultures upon SDS exposure (Fig. 5b). Here, the viability of cultures pre-treated with MAD1-RI and lysocin E, a peptide that causes membrane disruption30, declined more rapidly in the presence of SDS, and to a greater extent than untreated cultures, indicating heightened sensitivity to the detergent. Together, these results suggest that MAD1-RI compromises the integrity of the Mtb cell envelope by disrupting cell wall secretion, transport and biosynthetic processes.

a Transcriptional responses of Mtb to MAD1-RI. RNA-seq analysis was performed on Mtb H37Rv treated with MAD1-RI. b Increased sensitivity of MAD1-RI (160 µM) and Lysocin E (6 µg/mL) treated Mtb to SDS. c Membrane potential changes of DiOC2(3)-labeled Mtb treated in the absence (black) or presence of the indicated MAD1-RI (blue) or MAD1 (green) concentration. CCCP (100 μM) was used as the positive control. Data in (b, c) reported as mean + standard deviation. Source Statistical significance for n = 3 (b) or n = 4 (c) technical replicates determined relative to untreated controls (blank) using one-sided Student’s t-test, with p values shown. Data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further empirically test this assertion, we utilized the lipophilic dye DiOC2(3) to monitor MAD1-RI mediated changes in Mtb membrane potential. This fluorophore intercalates into the mycobacterial outer membrane and displays decreased red fluorescence as membrane potential is reduced. As expected, increasing MAD1-RI concentration from 1.25 to 37.5 μM led to a systematic reduction in DiOC2(3) fluorescence, producing similar membrane depolarization at the highest tested peptide concentration to the carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) protonophore positive control (Fig. 5c).

Finally, it is notable that MAD1-RI exposure also repressed prpD and Rv1129c (prpR) transcription in Mtb (Fig. 5a). Both genes encode for key enzymes in the methylcitrate cycle utilized by Mtb to process fatty acids as a carbon source during survival within macrophages31. Additionally, bfrB encodes the iron storage protein ferritin that regulates iron homeostasis in Mtb during survival and proliferation within infected host cells32. Thus, repression of these genes suggests that, in addition to its membrane destabilizing effects, MAD1-RI can disrupt fatty acid metabolism and lipid biosynthesis to compromise Mtb fitness in vivo. This may explain the reduction in MAD1-RI activity observed in our in vitro persister models relative to the proliferating cultures (Fig. 4). Here, although lipid metabolism may be downregulated by the peptide, the pathogen is rescued by other carbon sources available in the rich media. However, evidence from animal studies33 indicating that Mtb virulence in vivo is dependent on a shift to lipid catabolism suggests that, under nutrient depravation conditions within an infected host, MAD1-RI’s anti-TB activity may be significantly enhanced.

Discussion

While peptide retro-inversion is an established approach to improve the proteolytic stability of therapeutic peptides, we show here that it also enhances the antimycobacterial potency and specificity of HDPs through mechanisms distinct from enzymatic digestion. Although these improvements were observed for most of the tested HDPs, encouraging possible re-evaluation of previously overlooked sequences, MAD1-RI exhibited a particularly strong effect, possibly due to a gramicidin-like ion-leaking mechanism. Biophysical studies suggest that this mode of action differs from general membrane destabilization, potentially involving a head-to-tail arrangement forming intercalating pores or a β-helical pore with two copies of the retro-inversed MAD1-RI sequence in the mycomembrane. We show this activity not only leads to rapid killing of replicating Mtb, but potently synergizes with clinically relevant TB antibiotics. These findings, in combination with its regulation of genes important to Mtb virulence and cell wall biosynthesis, suggest that MAD1-RI may be a potent addition to the anti-TB therapeutic arsenal. That said, the mechanisms by which MAD1-RI synergistically enhance the antitubercular activity of moxifloxacin and meropenem are not fully understood. Further, it is unclear why MAD1-RI is not more effective towards persister Mtb bacilli if it employs membrane-dependent modes of action. This suggests that, in addition to its ability to compromise mycomembrane integrity, MAD1-RI may have complementary inhibitory effects on Mtb stress response pathways that require pathogen replication to fully actualize, warranting continued mechanistic exploration. Additional formulation of this therapeutic candidate into a particulate delivery vehicle may enhance its uptake into infected macrophages and trafficking to the host cell phagolysosome, thereby improving its efficacy towards intracellular bacilli. We also observed significant binding of the MAD1-RI peptide to human serum proteins during proteolysis experiments, suggesting future preclinical applications will require direct pulmonary delivery via inhalation. Accordingly, in vivo studies to assess MAD1-RI pharmacokinetics, antimycobacterial efficacy and safety in the respiratory tract following repeated aerosol dosing will be needed. Of particular importance will be thorough assessment of MAD1-RI mediated pulmonary inflammation and/or acute epithelial damage, as has been observed for other antimicrobial peptides34,35. Finally, in addition to its clinical potential, the rapid binding of MAD1-RI to mycobacterial cells may also enable its use as a diagnostic probe to monitor pathogens in wastewater and agricultural settings. More broadly, our findings suggest that retro-inversion may represent a unique chemical approach to design narrow-spectrum bactericidal peptides with anti-mycobacterial specificity.

Methods

Peptide synthesis, fluorescent labeling, purification and characterization

All peptides were synthesized following conventional Fmoc/tBu solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) using an automated Liberty Blue 2.0 microwave synthesizer (CEM Corp., North Carolina) following a high-efficiency SPPS protocol36. Protected peptides on resin were fluorescently labelled through a coupling reaction with Cy5-NHS ester (2 eq.) in the presence of DIPEA (6 eq.) for 24 hours at room temperature in the dark. For LC-MS analysis and HPLC purification, lyophilized peptide samples were dissolved in Solvent A (0.1% formic acid in LC/MS grade water) with concentrations ranging between 0.5 and 1 mg/ml and filtered using 0.2 µm nylon centrifugal filters. 100 µL of filtrate was transferred to an HPLC vial. The LC/MS characterization was carried out on a Shimadzu Prominence UFLC chromatographic system coupled to a Shimadzu LCMS-2020 single quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. Chromatographic separation was performed on a Phenomenex Luna® Omega C18 column (4.6 ×250 mm, 5 µm particle size) at a temperature of 40 °C and a flow speed of 0.5 mL/min. A linear gradient was applied with Solvent B (90% LC/MS grade acetonitrile in water with 0.1% formic acid) increasing at a rate of 1% per minute to a final ratio of 100%. MS data was acquired in positive ion detection mode over a m/z scan range of 100–2000 Da with a scan speed of 10,000 u/s, scan time of 0.2 s and an interface voltage of 3 kV. During the analysis, temperature for the desolvation line and heating block were set to 250 °C and 300 °C, respectively. Flow rates for nebulizing gas and drying gas were set at 1.5 L/min and 10 L/min, respectively. MS data were processed using Shimadzu LabSolutions software (version 5.135). Fluorescence images of labeled peptides were collected with a Biotek Cytation 3 plate reader and Zeiss LSM 880 confocal laser scanning microscope and scanning electron micrographs were obtained with a Zeiss Sigma scanning electron microscope.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

CD measurements were conducted using a JASCO J-1500 spectrometer equipped with a Peltier-controlled PTC-517 thermostat cell holder. Spectra were recorded from 260 nm to 185 nm at a scan speed of 50 nm/min, with a bandwidth of 1 nm at 25 °C. A 1 mm pathlength quartz cuvette was used, and the peptide concentration was 100 µM. A buffer blank was measured before the sample for baseline subtraction, and the data were converted to molar ellipticity. Analysis was performed using the Jasco Multivariate SSE program along with BeStSel algorithm23,24,25 for single-spectrum analysis and secondary structure prediction. Temperature-dependent CD experiments were carried out from 20 °C to 95 °C in 5 °C increments, with a heating rate of 1 °C/min. Spectra were recorded at 50 nm/min from 260 nm to 185 nm, with a data pitch of 1 nm, a DIT of 4 s, and a bandwidth of 1 nm. Wavelength-dependent changes at 208 nm and 220 nm were plotted against temperature. All CD experiments utilized pH 7.4 phosphate buffer, except for data reported in Fig. 2d, e in which SDS in pure water was used to determine the effect of SDS concentration on secondary structure.

AUC methods

Peptides, dissolved in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at a concentration of 33 µM, were loaded into 12 mm Epon-charcoal centerpieces within AUC cells featuring sapphire windows. These cells were placed into an An50 titanium rotor, which had been pre-equilibrated to 37 °C, the experimental temperature. The rotor was then inserted into the chamber of a Beckman-Coulter Optima multiwavelength AUC equipped with absorbance optics. A full vacuum was applied in the chamber, and the rotor was allowed to re-equilibrate for 2 hours. A method scan was created using the UltraScan III software and transferred to the instrument, where the experiment began after temperature equilibration. The rotor was spun at 40,000 RPM for 11 hours, capturing radial scans every three minutes at 280 nm. Once the AUC experiment was complete, the data were imported into UltraScan III. Reference scans were automatically chosen to convert the raw radial intensity data into pseudo-absorbance. The air-liquid meniscus was manually selected for each sector. The dataset was also manually cropped, typically between 6.1 cm and 7.1 cm, and the first 5-10 scans, as well as those following complete sedimentation, were excluded from analysis. The edited data were then processed using the LIMS supercomputer at Penn State, with an S-value range set from 1 to 10, a resolution of 100, and a frictional ratio range from 1 to 4, with a resolution of 64. Time-invariant noise was also accounted for during the initial analysis. When the residuals fell below 0.003, the data were refitted, this time incorporating both time and radially invariant noise, along with 11 meniscus fits to ensure precise determination of the meniscus. Once the correct meniscus was identified, a final time and radial invariant noise fit was performed using an iterative method. Lastly, the data were analyzed using a genetic algorithm with Monte Carlo simulations (selecting 1-2 species per sample). 32 Monte Carlo simulations were run using 16 processors, and the resulting pseudo-3D plots were analyzed for final calculations of the s-value, frictional ratio, and molecular weight.

BioSAXS

Small angle X-ray scattering (BioSAXS) data were collected on peptides at a concentration of 4.5 mg/ml using X-rays with a wavelength of 1.54 Å from an in-house Rigaku MM007 rotating anode X-ray source. This system was coupled with the BioSAXS2000nano Kratky camera, which features OptiSAXS confocal max-flux optics specifically designed for SAXS experiments and a HyPix-3000 Hybrid Photon Counting detector for high sensitivity. The sample was positioned in a capillary with a detector-to-sample distance of 495.5 mm, calibrated using silver behenate powder from The Gem Dugout (State College, PA). The scattering vector q-space (q = 4πsin(θ)/λ, where 2θ is the scattering angle) ranged from q_min = 0.008 Å⁻¹ to q_max = 0.6 Å⁻¹. The X-ray beam energy was 1.2 keV, with a Kratky block attenuation of 22% and a beam diameter of approximately 100 μm. Peptide samples were automatically loaded onto a quartz capillary flow cell via a Rigaku autosampler, which was cooled to 4 °C and aligned with the X-ray beam. The sample cell and entire X-ray flight path, including the beam stop, were kept in a vacuum (below 1 × 10⁻³ torr) to eliminate air scattering. The Rigaku SAXSLAB software controlled automated data collection for each peptide, incorporating thorough cleaning cycles between samples. Data reduction, including image integration, normalization, and background subtraction, was also handled by SAXSLAB software. Six ten-minute images, along with three replicates of both protein and buffer samples, were collected, averaged, and inspected to confirm that no radiation damage occurred. Overlays of the SAXS data confirmed no radiation decay or sample loss during the 60 min collection period. Following this, buffer subtraction was performed to isolate the raw SAXS scattering curve of the peptide. The forward scattering intensity (I(0)) and the radius of gyration (Rg) were calculated using the Guinier approximation, which assumes that at very small angles (q < 1.3/Rg), the intensity follows I(q) = I(0)exp[−1/3(qRg)²]. The results were consistent with the expected size of peptide dimers. Further analysis of the data, including radius of gyration, Dmax, Guinier fits, Kratky plots, and pair distance distribution functions, was carried out using the ATSAS software. Solvent envelopes were calculated with DAMMIF, an algorithm for deriving ab initio bead models directly from solution scattering data.

Fluorescence and electron microscopy

For fluorescence microscopy, Mtb mc26230 was grown to an OD of 0.02 in supplemented Middlebrook 7H9 broth. The bacterial cells were isolated by centrifugation (7000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C) and re-suspended in 7H9 broth or PBS containing cyanine-5 tagged MAD1-RI (10 µM) for 30 min, followed by Auramine O (0.02 g/mL) staining for 15 min and washed gently twice in PBS prior to drying and heat fixation on a glass microscopy slide. A glass cover slip was then adhered to the top of the sample with a dab of ProLong™ Diamond Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen) overnight in the dark.

For SEM samples, bacteria were grown identically to the fluorescence microscopy protocol and incubated in the presence of 0.5 x MIC, 1 x MIC, and 5 x MIC of MAD1-RI for 30 min before being passed through a 0.2 micron pore filter disc. The bacteria trapped on the filter disc were then fixed with glutaraldehyde (2.5% v/v) in phosphate buffer for 30 min followed by step-wise dehydration with 10, 25, 50, 75, 85, 95, and 2 ×100% solutions of ethanol. The discs were then dehydrated with a Leica EM CPD300 Critical Point Dryer (Leica) prior to being mounted on titanium stubs and sputter coated with a 4.5 nm layer of iridium prior to viewing. For TEM analysis, Mtb were isolated during its logarithmic growth phase (OD600 0.5 - 0.8) and diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 in 500 μL of supplemented 7H9 media, following which they were treated with 1x, 5x and 25x MIC of MAD1-RI and incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes. After treatment, cells were pelleted down at 7000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and washed gently with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer once. Cells were fixed overnight using a solution containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at 4°C. Cells were washed twice with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and post-fixed with 1% Osmium tetraoxide (with 0.02% v/v Triton X-100) for 2 hours at room temperature in the dark. Triton X-100 was added to the fixative solution to enhance osmium tetraoxide penetration into cells. Fixed samples were washed again with buffer twice and dehydrated for 5 min each using a graded ethanol series (50%, 70%, 80% and 95%). Subsequently, samples were dehydrated twice for 5 minutes each in 100% ethanol and absolute acetone before they were transferred into a 1:1 v/v mixture of acetone and epoxy resin for an hour. Finally, samples were kept at 70°C in pure epoxy resin overnight for embedding before they were sliced on a Leica EM UC6 ultramicrotome to collect 70 nm sections on Formvar/carbon coated 400 mesh Cu grids (Ted Pella). The grids were post stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed on a Thermofisher F200C Talos TEM instrument.

Antimicrobial testing

Antimicrobial activity was determined by standard broth microdilution minimal inhibitory assays wherein peptide was serially diluted across a 96-welled plate and bacteria adjusted to an OD600 of 0.002 was added to each concentration of peptide30. All bacteria were grown and assayed in specialized broth at 37 °C. M. smegmatis (mc2155) and Mtb complex lab strains (M. bovis BCG, mc26230, H37Rv and H37Ra) were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 and supplemented 7H9 broth, respectively. Mtb clinical isolates were grown in Middlebrook supplemented 7H9 containing 40 mM pyruvate. All virulent strains of Mtb were handled under BSL-3 conditions following institutionally approved protocols. S. aureus (USA300), P. aeruginosa (PAO1), and A. baumanii (ATCC19606) were grown in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB). 7H9 broth for the auxotrophic mc26230 strain was prepared with glycerol (0.2% v/v), oleic acid-albumin-dextrose catalase (OADC; 10% v/v), Tween-80 (0.02% v/v), and pantothenic acid (50 mg/L). For colony growth, the mycobacteria species were grown on Middlebrook 7H10 agar with the same supplementation except for Tween-80. The other bacteria were all grown on MHB agar.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays were performed by dissolving peptides to 320 µM in sterile nuclease-free water, or dissolving antitubercular drugs in DMSO, and 2-fold serially diluting compound stock solutions in 7H9 broth (50 μL volume after dilution) in a sterile 96-well round bottom plate in triplicate. Bacterial growth was measured via OD600, and the culture was diluted to an OD600 value of 0.002 for the mCherry expressing Mtb H37Rv and other Mtb clinical isolates. 50 μL of bacterial suspension was added to the treated wells in a 1:1 v/v ratio (100 μL final volume)37. H37Rv and H37Ra growth were assessed by measuring fluorescence at 570/610 nm using a plate reader after incubating at 37 °C for 96 hours. MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide)38 assays were employed to evaluate MIC of antitubercular compounds against Mtb clinical isolates. Briefly, microtiter plates with dilution series of the antitubercular compounds were inoculated to an OD600 0.01. Following incubation (7 days for antimicrobial peptides, 14 days for antitubercular drugs) at 37 °C, 10 µL of sterile 5 mg/mL MTT was added. After overnight incubation at 37˚C, 50 µL freshly prepared formazan solubilization buffer containing 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 25% N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) was added. Plates were incubated for 4 h and OD570 was recorded using a BioTek Synergy H1 plate reader. MICs were scored as the lowest concentrations of ATDs exceeding 90% inhibition of absorbance at 570 nM. Assays were repeated with at least 2 independent biologic replicates for each strain (n ≥ 6). MIC values were reported as their geometric means unless stated otherwise.

Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) for replicating cultures was determined by adjusting exponentially growing Mtb to OD600 of 0.1 and treating bacilli with 40, 80, 160 µM of MAD1-RI. Culture plating was done on 7H10 agar at day 0, 1, 3 and 7. The MBC was defined as the lowest concentration which reduced CFU count by 99% relative to the time-zero inoculum on day 7. Twenty-one-day kill kinetics were assessed to evaluate the bactericidal activity of MAD1-RI in combination with other drugs by CFU count. For this purpose, a mid-log-phase Mtb culture was diluted in fresh medium (OD600 of 0.1). After aliquoting the culture to 30 ml square bottles, the indicated concentration of anti-TB drugs was added to each sample, and cultures were incubated for 21 days. Each culture dilution was plated at selected time intervals on 7H10 agar plates, and the Mtb CFU on each plate were enumerated after incubating at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 enriched atmosphere for 3-4 weeks30.

Mammalian cell viability

Human lung carcinoma cells (A549) were plated in flat bottomed sterile 96 well plates (2000 cells/well) and incubated overnight at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Peptide concentrations of 10–500 μM were prepared through serial dilution in cell culture media and thoroughly vortexed, before replacing cell culture media with 100 μL of prepared treatment solutions. Each treatment had six technical replicates and cells treated with blank media and 10% DMSO in media were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. After 24 hrs, cells were washed with PBS and 100 μL of MTT reagent (0.5 mg/ml) in PBS was added to all wells. After 3 hrs of incubation at 37 °C, MTT reagent was removed, and cells were solubilized using 100 μL of DMSO. Following 10 min of incubation at 37 °C, plates were loaded onto a BioTek Cytation 3 microplate reader and absorbance measured at 540 nm. Cell viability for each treatment concentration was calculated using the following equation: (Atreatment - Apositive control)/ (Anegative control - Apositive control) × 100%. MTT assays for all treatments were repeated twice (n = 12). A similar protocol was used to assess the viability of human macrophages (THP-1), with pre-differentiation with 100 ng/μL of PMA for 24 h at 37 °C and a seeding density of 40,000 cells/well.

Proteolytic stability testing

Proteinase K degradation was evaluated by preparing aliquots of the peptide and enzyme in PBS (500 µl) at a final concentration of 90 µM and 10 µg/mL, respectively, and incubated at room temperature. At each time point, 50 µL of the assay mixture was collected and mixed with an equal volume of an acetonitrile/water mixture (1:1 ratio, 0.1% v/v formic acid) prior to chromatographic analysis.

For human serum samples, blood was collected from healthy human donors (IRB# 12449) and centrifuged at 2000g for 15 min. to collect serum, which was stored at 4 °C before use. 0.5 mM peptide solutions in sterile PBS were treated with 25% v/v of fresh human serum and incubated at 37 °C. At select time points, 50 μL aliquots were taken and digestion stopped via overnight precipitation at –20 °C with 2X volume of ice-cold Acetonitrile (LC-MS grade) with 0.1% formic acid. Samples were centrifuged at 10000 g for 10 min. at 4°C to remove serum proteins and the supernatant was filtered. A sample of 10 μL was run on a LCMS-2020 instrument (Shimadzu Corporation) through a reverse phase Luna Omega C18 100 Å HPLC column. UV220 nm absorbance peaks between retention time ranging from 15.48 to 15.78 min for MAD1 and 15.29 to 15.72 min for MAD1-RI were used to calculate the total area under the curve (AUC) for samples at each timepoint, which was then normalized to t = 0. Corresponding LC-MS ESI (+) data were used to eliminate UV peaks that did not belong to the full-length native peptide. Peptide samples in PBS, or PBS alone, were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Drug synergy

Checkerboard assays were used to test for interactions between MAD1-RI and drugs with known anti-TB activities by the broth microdilution method in 96-well microtiter plates. After preparing serially diluted drugs on two different plates, 25 μl from each well of the MAD1-RI plate (plate 1) and another drug plate (plate 2) were transferred to the corresponding wells of a new plate (plate 3) and mixed (the final drug volume of each well was 50 μl). Then, like the MIC assay, 50 μl of mCherry expressing Mtb H37Rv suspension (OD600 of 0.002) was added to the wells of each plate considered for testing37. The MIC for each drug or combination was defined as the lowest concentration that reduced fluorescence by 90% after incubating the plates at 37 °C for 4 days. To evaluate the effect of each combination, the obtained MIC values were used to calculate the fractional inhibitory coefficient index (FICI) as follows: FICI = (MIC of drug A in combination/MIC of drug A alone) + (MIC of drug B in combination/MIC of drug B alone). The FIC index (FICI) calculated for each drug combination was categorized based on FICI: <0.5 as synergistic, >0.5 to <1 as additive; and >2 as antagonistic39.

Kill curves with non-replicating Mtb

To study the bactericidal activity of MAD1-RI against non-replicating mycobacteria (NRP), nutrient-starved and hypoxia-induced nonreplicating Mtb were used. To obtain the hypoxia-induced, NRP Mtb phenotype, H37Ra cultures in the early log phase were transferred to an anaerobic chamber (atmosphere of 5% CO2, 10% H2, 85% N2) and grown for 3 weeks at 100 rpm, 37 °C. Then, to evaluate the bactericidal activities of MAD1-RI against NRP Mtb, H37Ra cultures were transferred to 15 ml test tubes and treated with different concentrations of the indicated drugs. The cultures were then incubated for 2 weeks and plated on 7H10 agar at selected time intervals30. To obtain nutrient-starved NRP Mtb, H37Rv bacilli were grown to the exponential phase. Bacteria were then harvested by centrifugation (3200 rpm; 4 °C; 5 min) and washed twice with PBS containing 0.025% Tween 80. The bacteria were diluted to a final OD600 of 0.2 in PBS and incubated for 3 weeks at 37 °C. Clumps were removed by low-speed centrifugation (2000 x g; 3 min) just before treatment. To evaluate the bactericidal activities of the peptides against nutrient-starved NRP, Mtb H37Rv was transferred to 30 ml square bottles, and treated with MAD1-RI, isoniazid, or moxifloxacin at the indicated concentration. Each culture dilution was plated at selected time intervals on 7H10 agar plates, and the Mtb CFU on each plate was enumerated after incubating at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 enriched atmosphere40.

Macrophage intracellular Mtb bacilli clearance

THP-1 human monocytes (ATCC TIB-202; authenticated via company provided certificate of analysis) were cultured in Gibco RPMI 1640 Medium with 10% FBS, 0.0062% BME, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (complete medium). Cells were grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Once an appropriate density was reached, the culture was diluted to a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL. Cells were seeded in a 12-well plate at 1 mL/well and differentiated into macrophages via exposure to 100 nM PMA for 72 h. Any non-adherent cells were removed via 3x washes with 1 mL Hank’s Buffered Saline Solution (HBSS). Cells then rested in antibiotic-free complete medium for 24 hours. Cells were then exposed to 5 ng/mL IFN-γ and given 24 hours to activate.

A 10 mL culture of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv was grown in 7H9 media supplemented with 10% OADC, 0.05% Tween-80, and 0.2% glycerol (Mtb complete medium) to an OD600 of approximately 0.5 before being transferred to a 15 mL conical tube and spun down. Bacterial cells were washed 3x in antibiotic-free complete medium before being diluted to 105 CFU/mL. One mL of bacterial suspension was added to each macrophage-containing well at an MOI of 1:1. A two-hour incubation period at 37 °C with 5% CO2 was utilized for the macrophages to phagocytize the bacteria. Non-engulfed bacteria were then removed via 3x washes with HBSS. Cells were then treated with antibiotic-free complete medium with the appropriate treatment compounds (100 μM MAD1-RI, 0.31 μg/mL INH, or no drug control). Well medium with 5 ng/mL IFN-γ was replaced every 48 h. MAD1-RI and INH were both spiked in on day 4 of 8. Plating for intracellular bacteria occurred on days 0, 2, 4, and 8. Macrophages were washed 3x with HBSS before being lysed with the addition of 1 mL 0.1% TritonX 100 for 10 minutes. 10-fold serial dilutions of this lysis solution were prepared in Mtb complete medium and plated on 7H10 agar plates with 10% OADC and 0.2% glycerol. Plates were stored for 21 days at 37 °C before enumeration of CFUs occurred.

Transcriptional profiling and analysis

For RNA isolation, Mtb H37Rv was cultured in 7H9 media to an OD600 of 0.1 before being treated with 25 μM MAD1-RI for 24 h41. After treatment, mycobacterial RNA was extracted using a Zymogen RNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) with minor modifications to the manufacturers protocol. Briefly, cells were resuspended in trizol reagent and 1% Polyacyl carrier and disrupted using Zirconia beads (Biospec, Bartlesville, OK, USA) by beating two times for 1 minute and cooling on ice for two minutes in between. The samples were spun down at 14,000 RPM for 10 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was transferred to clean tubes. Each sample was vortexed after 50 µl of BCP (bromo 3-chloro propane) was added. The samples were then harvested into a fresh RNase-free E-tube and one volume of ethanol (95-100%) was added directly to one volume sample (1:1). Samples were mixed well by vortexing. The sample mixtures were then loaded into a Zymo-Spin Column in a collection tube, and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 1 min.

To clean up the RNA, the columns were washed with 400 μl RNA wash buffer by centrifuging for 30 s. To decontaminate DNA, DNase I Reaction Mix was added directly to the column matrix which was then incubated at RT (20-30°C) for 15 minutes, followed by centrifugation for 30 s. The samples were then washed with 400 μl Direct-zol RNA PreWash twice by centrifuging for 1 min. Samples were washed once again by adding 700 μl RNA Wash Buffer to the column and centrifuging for 1 min. Finally, 50 μl of Dnase/Rnase-Free Water was directly added to the column matrix and centrifuged for 1 min. The eluted RNA was stored at −80 °C and sent for processing and sequencing. cDNA libraries were prepared by SeqCenter (Pittsburgh, PA) with a Stranded Total RNA Prep using the Ribo-Zero Plus 563 Microbiome kit (Illumina Inc). cDNA libraries were sequenced using the Illumina Novaseq platform optimized for 150 bp paired-end reads and producing approximately 12 million reads.

RNA sequencing data was analyzed by preprocessing the raw.fastq output files using the pipeline available at https://github.com/MDHowe4/RNAseq-Pipeline. FastQC was utilized to measure the quality control of the reads. Read lengths and t-overhangs were trimmed via Cutadapt, the minimum read length for which was set to 30 bp. Alignment to the Mtb H37Rv genome (NC_000962.3) was performed by the STAR aligner with spliced alignment detection disabled (--alignIntronMax 1). The read counts for given genes were procured via featureCounts, with exclusion criteria defined as genes with fewer than 10 reads across all samples. A negative binomial generalized linear model was created with DESeq2 to quantify the differential expression of genes. Significance was reserved for genes which met both a log2-fold change ≥ 1 or ≤ -1 and an adjusted p-value of <0.05 criteria. The ggplot2 package was used to generate volcano plots for these data.

SDS sensitivity assay and assessment of membrane potential

Mtb H37Rv was grown in 7H9 medium supplemented with OADC and 0.05% Tween 80 to an OD600 of 0.5. Cultures were then treated with 160 µM MAD1-RI and 6 µg/ml Lysocin E for 24 h. Following treatment, bacterial pellets were washed twice with sterile PBS and resuspended to an OD600 of 0.1 in PBS. SDS was added to a final concentration of 0.005%, and cultures were plated on 7H10 agar at 0 and 3 hours post-SDS exposure. After incubation at 37 °C for 3–4 weeks, CFUs were enumerated, and percent survival at 3 hours was calculated relative to the starting CFUs at 0 h41.

Membrane potential was assessed as previously described42, with modifications. Briefly, mid-exponential- phase Mtb H37Ra cells grown in supplemented 7H9 medium were centrifuged (3000 rpm for 10 min) and resuspended to a final OD600 of 0.1 in 3 ml supplemented 7H9 medium at pH 7.0 in 30 ml square Nalgene bottles. Peptides and ionophores were added to the final concentrations indicated in the graph and incubated at 37 °C. At 30 min, 180 µl was removed, 20 µl of 150 µM 3,3-diethyloxicarbocianide chloride [DiOC2(3)] was added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were then washed, resuspended in supplemented 7H9 medium, transferred to a black-walled 96-well plate, and analyzed in a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M2 plate reader, and fluorescence was assessed by excitation of samples at 488 nm and recording the emissions at 530 nm and 610 nm. Ratios of the emission at 610 nm/emission at 530 nm were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Unless stated otherwise in the manuscript, data represents n = 3 technical replicates and presented as mean ± standard deviation. Significance between groups was determined by Student’s or Dunnett two-sided t-test, with p values for each comparison shown in the appropriate figure or tabulated in Supplementary Tables S4-6.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The primary RNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database under accession codes SRX25995207–SRX25995212 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1157802]. All other data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhang, Y. & Yew, W. Mechanisms of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: update 2015. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 19, 1276–1289 (2015).

Rima, M. et al. Antimicrobial peptides: a potent alternative to antibiotics. Antibiotics 10, 1095 (2021).

Landman, D., Georgescu, C., Martin, D. A. & Quale, J. Polymyxins revisited. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21, 449–465 (2008).

Li, Z., Cao, Y., Yi, L., Liu, J. H. & Yang, Q. Emergent polymyxin resistance: end of an era? Open Forum Infect. Dis. 6, ofz368 (2019).

Rezaei Javan, R., Van Tonder, A. J., King, J. P., Harrold, C. L. & Brueggemann, A. B. Genome sequencing reveals a large and diverse repertoire of antimicrobial peptides. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2012 (2018).

Lazzaro, B. P., Zasloff, M. & Rolff, J. Antimicrobial peptides: application informed by evolution. Science 368, eaau5480 (2020).

Santos-Júnior, C. D. et al. Discovery of antimicrobial peptides in the global microbiome with machine learning. Cell 187, 3761-3778.e16 (2024).

Maasch, J. R. M. A., Torres, M. D. T., Melo, M. C. R. & de la Fuente-Nunez, C. Molecular de-extinction of ancient antimicrobial peptides enabled by machine learning. Cell Host Microbe 31, 1260–1274.e1266 (2023).

Wan, F., Torres, M. D. T., Peng, J. & de la Fuente-Nunez, C. Deep-learning-enabled antibiotic discovery through molecular de-extinction. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 8, 854–871 (2024).

Chorev, M. & Goodman, M. A dozen years of retro-inverso peptidomimetics. Acc. Chem. Res. 26, 266–273 (1993).

Goodman, M. & Chorev, M. On the concept of linear modified retro-peptide structures. Acc. Chem. Res. 12, 1–7 (1979).

Doti, N., Mardirossian, M., Sandomenico, A., Ruvo, M. & Caporale, A. Recent Applications of Retro-Inverso Peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8677 (2021).

Li, C. et al. Limitations of peptide retro-inverso isomerization in molecular mimicry. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19572–19581 (2010).

Preston, G. W. Different directions for retro-inverso peptides. J. Pept. Sci. 28, e3384 (2022).

Al Musaimi, O. Unlocking the potential of retro-inverso (RI) peptides as future drug candidates. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 30, 56 (2024).

Simonson, A. W. et al. Pathogen-specific antimicrobials engineered de novo through membrane-protein biomimicry. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 467–480 (2021).

Biswas, D. et al. Lead informed artificial intelligence mining of antitubercular host defense peptides. Biomacromolecules 26, 3167–3179 (2025).

de Moraes, L. et al. First generation of multifunctional peptides derived from latarcin-3a from Lachesana tarabaevi spider toxin. Front. Microbiol. 13, 965621 (2022).

Rangel, M. et al. Chemical and biological characterization of four new linear cationic α-helical peptides from the venoms of two solitary eumenine wasps. Toxicon 57, 1081–1092 (2011).

Chaparro-Aguirre, E. et al. Antimicrobial activity and mechanism of action of a novel peptide present in the ecdysis process of centipede Scolopendra subspinipes subspinipes. Sci. Rep. 9, 13631 (2019).

Cochran, A. G., Skelton, N. J. & Starovasnik, M. A. Tryptophan zippers: Stable, monomeric β-hairpins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5578–5583 (2001).

Liu, J., Yong, W., Deng, Y., Kallenbach, N. R. & Lu, M. Atomic structure of a tryptophan-zipper pentamer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 16156–16161 (2004).

Micsonai, A. et al. Accurate secondary structure prediction and fold recognition for circular dichroism spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E3095–E3103 (2015).

Micsonai, A. et al. BeStSel: webserver for secondary structure and fold prediction for protein CD spectroscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, W90–W98 (2022).

Micsonai, A. et al. Disordered–ordered protein binary classification by circular dichroism spectroscopy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9 (2022).

Klinkenberg, L. G., Sutherland, L. A., Bishai, W. R. & Karakousis, P. C. Metronidazole lacks activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in an in vivo hypoxic granuloma model of latency. J. Infect. Dis. 198, 275–283 (2008).

Hunt, D. M. et al. Long-range transcriptional control of an operon necessary for virulence-critical ESX-1 secretion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 194, 2307–2320 (2012).

Boradia, V., Frando, A. & Grundner, C. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis PE15/PPE20 complex transports calcium across the outer membrane. PLoS Biol. 20, e3001906 (2022).

Pang, X. et al. The β-propeller gene Rv1057 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis has a complex promoter directly regulated by both the MprAB and TrcRS two-component systems. Tuberculosis 91, S142–S149 (2011).

Wiegand, I., Hilpert, K. & Hancock, R. E. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 3, 163–175 (2008).

Tang, S. et al. Structural and functional insight into the Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein PrpR reveals a novel type of transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 9934–9949 (2019).

Kurthkoti, K. et al. The mycobacterial iron-dependent regulator IdeR induces ferritin (bfrB) by alleviating Lsr2 repression. Mol. Microbiol. 98, 864–877 (2015).

Savvi, S. et al. Functional characterization of a vitamin B12-dependent methylmalonyl pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for propionate metabolism during growth on fatty acids. J. Bacteriol. 190, 3886–3895 (2008).

Hancock, R. E. W. & Sahl, H.-G. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 1551–1557 (2006).

Thoma-Uszynski, S. et al. Induction of direct antimicrobial activity through mammalian toll-like receptors. Science 291, 1544–1547 (2001).

Collins, J. M., Porter, K. A., Singh, S. K. & Vanier, G. S. High-Efficiency Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis (HE-SPPS). Org. Lett. 16, 940–943 (2014).

Geberetsadik, G. et al. Lysocin E targeting menaquinone in the membrane of mycobacterium tuberculosis is a promising lead compound for antituberculosis drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 66, e0017122 (2022).

Martin, A. et al. Multicenter study of MTT and resazurin assays for testing susceptibility to first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 9, 901–906 (2005).

Odds, F. C. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52, 1 (2003).

Gengenbacher, M., Rao, S. P. S., Pethe, K. & Dick, T. Nutrient-starved, non-replicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis requires respiration, ATP synthase and isocitrate lyase for maintenance of ATP homeostasis and viability. Microbiology 156, 81–87 (2010).

Jeon, A. B. et al. 2-aminoimidazoles potentiate ß-lactam antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis by reducing ß-lactamase secretion and increasing cell envelope permeability. PLoS One 12, e0180925 (2017).

Peterson, N. D., Rosen, B. C., Dillon, N. A. & Baughn, A. D. Uncoupling environmental pH and intrabacterial acidification from pyrazinamide susceptibility in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 7320–7326 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank William R. Jacobs, Jr and Michael Berney of Albert Einstein College of Medicine for gifting the various mycobacterial strains used in this study. We also wish to thank the assistance of Julia Fecko at the X-ray Crystallography core at the Penn State Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, Missy Hazen at the Penn State Materials Research Institute, and the UMN BioSafety Level 3 Program for facility management. Funding for this work was provided by NIH R01AI165996 to S.H.M., and NIH S10OD032215 and S10OD028589 to N. H. Y.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.D.G. and G.G. led compound synthesis, bacteriologic and biophysical assays, and supported manuscript writing/editing. S.S., D.B., and N.A.S. supported the synthetic and bacteriologic work, as well as data analysis and interpretation, and supported manuscript writing/editing. N.H.Y. performed biophysical ultracentrifugation studies and subsequent data analysis. M.A.R. led compound screening in clinical Mtb isolates. A.D.B. supported experimental design and result interpretation, led the supervision of work in BSL-3 facilities, and supported manuscript writing/editing. S.H.M. led the supervision of synthetic, biophysical and BSL-2 bacteriologic work, acquisition of resources, and manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bruno Rivas-Santiago, Andrea Caporale, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Glossop, H.D., Gebretsadik, G., Sultana, S. et al. Retro-inversion imparts antimycobacterial specificity to host defense peptides. Nat Commun 17, 469 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67162-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67162-0