Abstract

Coherent light-matter interactions between a quantum gas and light in a high-finesse cavity can drive self-ordering phase transitions. To date, such phenomena have involved exclusively single-atom coupling to light, resulting in coupled charge-density or spin-density wave and superradiant order. In this work, we engineer simultaneous coupling of cavity photons to both single atoms and fermionic pairs, which are also mutually coupled due to strong correlations in the unitary Fermi gas. This interplay gives rise to an interference between the charge-density wave and a pair-density wave, where the short-range pair correlation function is spontaneously modulated in space. We observe this effect by tracking the onset of superradiance as the photon-pair coupling is varied in strength and sign, revealing constructive or destructive interference of the three orders with a coupling mediated by strong light-matter and atom-atom interactions. Our observations are compared with mean-field theory where the coupling strength between atomic- and pair-density waves is controlled by higher-order correlations in the Fermi gas. These results demonstrate the potential of cavity quantum electrodynamics to produce and observe exotic orders in strongly correlated matter, paving the way for the quantum simulation of complex quantum matter using ultracold atoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interplay of competing and intertwined emergent orders is a hallmark of strongly correlated quantum matter1,2. These systems –ranging from high-temperature superconductors3,4,5 to Van der Waals materials6,7,8 and multiferroics9,10,11−exhibit diverse phases within narrow parameter ranges, offering remarkable tunability and technological promise. While there is always competition of different order parameters for electrons on the Fermi surface, the presence of one order may favor fluctuations of another one, resulting in an effective order parameter cooperation3,12,13. In electron systems, a particularly important class of competing or intertwined orders is superconductivity and spin- and charge-density wave states14,15. For example, both s-wave superconductivity and CDW orders are favored by phonon-mediated attraction between electrons. The dominant instability is determined by microscopic details of the system16. Several theoretical models suggested that the interplay of the two orders can lead to even more surprising scenarios, in which Cooper pairing occurs at finite momentum. This includes theoretical proposals of η-pairing17, Amperean pairing18, and pair-density wave states19. Pairing operators at finite momentum also play a crucial role in models of correlated electron states based on high symmetries, such as the SO(5) models of d-wave superconductivity and antiferromagnetism20, see also21,22,23. However, experimental evidence of pairing at finite momentum remains scarce (see however24).

Quantum gas experiments provide a powerful platform for exploring and understanding strongly correlated phenomena, as they combine a microscopic Hamiltonian that is known a priori, local interactions that can be tuned to extreme regimes, and direct observation of the different macroscopic orders. The unitary Fermi gas is an iconic example of a strongly correlated system where phase competition has been extensively studied25. In parallel, cavity-quantum electrodynamics (cQED) methods offer tunable, coherent light-matter interactions, resulting in the emergence of superradiant phases26,27,28,29,30 which can be combined with the short-range interactions in a quantum gas. This led to investigations of the interplay of orders31 combining superradiance and strong contact interactions32,33,34.

In this work, we realize a completely tunable interplay of three strongly coupled orders in a quantum-degenerate Fermi gas within a high-finesse optical cavity: photonic superradiance, charge-density wave and pair-density wave. Our experiment operates in the unitary limit of contact interactions, where fermions form pairs with a size on the order of the interparticle spacing35. This results in the coupling of the charge-density wave and the pair-density wave orders, which can be tuned via the Feshbach resonance. The cavity light field dispersively couples to single atoms and atomic pairs simultaneously36, resulting in three strongly coupled order parameters, with independently tunable interactions. Light scattered off single atoms and atomic pairs interferes, giving rise to a characteristic Fano-type profile of the superradiant phase diagram. This profile reflects the competition and cooperation between the two fermionic orders. On the competitive side, the suppression of the onset of the superradiant phase can be understood as frustration between antagonistic density wave and pair-density wave orders. A mean-field analysis of the three coupled order parameters captures this effect. Our analysis reveals the role of previously unexplored higher-order correlations of the Fermi gas and offers insight into the complex interplay of multiple competing and cooperating coupled orders.

Results

Coupled order parameters

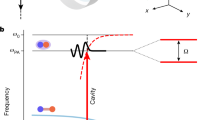

We realize a system with three strongly coupled order parameters, describing the in-phase quadrature of the cavity field and the amplitudes of the charge and pair-density waves, described by the macroscopic fields X, Θ, and Π, respectively. Up to second order in the macroscopic fields, the Landau-Ginzburg free energy of the system can be written as:

and schematically represented as in Fig. 1a (see “Methods” for a microscopic derivation). ϵΘ, ϵΠ and ϵX represent the energy cost of the uncoupled orders, which are all positive, and therefore oppose ordering. The coupling between Θ and Π is set by U, the coupling between X and Θ is determined by Λ, and that between X and Π by rΛ. Ordering occurs when, due to their mutual coupling, the curvature of the free energy in the vicinity of the origin is negative along a particular direction. In our experiment, we fix U and vary Λ and r, tuning the latter in both sign and strength. Choosing the same sign for the three couplings results in intertwining, where all the ordering contributions cooperate. Conversely, flipping the sign of r leads to frustration and competing order parameters. The phase diagram for this system is sketched in Fig. 1b, with a boundary separating the organized and homogeneous phases exhibiting a characteristic Fano shape, as a function of 1/r. Akin to geometric frustration, this phenomenology is only possible with more than two coupled orders. With only two orders, such as light and atomic density, the sign of the coupling is irrelevant, as it amounts to a sign change of the pump beam amplitude.

a Charge-density wave (Θ), pair-density wave (Π), and in-phase cavity-field quadrature (X) represent the three coupled orders. Λ, the strength of the dispersive atom-cavity coupling, is controlled via the pump strength V0. r denotes the relative strength of the dispersive coupling of atoms and pairs to the cavity. Θ and Π are mutually coupled by strong atom-atom interactions with a strength U. b Schematic phase boundary separating the normal (X = 0) from the superradiant phase (X ≠ 0) as a function of V0 and −1/r, showing a characteristic Fano-type profile. c Single atoms (left) and pairs of atoms (right) in a unitary Fermi gas within the mode of a high-finesse cavity can scatter photons from a transverse pump into the cavity and vice versa. The pump (red arrows) forms a standing wave with a wavevector \({\overrightarrow{k}}_{p}\). The dispersive coupling strengths Λ and rΛ are determined by the detuning Δa between the pump (p) and the atomic resonance (a), and the detuning Δm between the pump and a photo-association resonance (m), respectively.

Microscopically, the simultaneous occurrence of strong atom-atom and strong light-matter interactions couples the three orders as follows (see “Methods” for the formal derivation). First, the parameter Λ has its strength and sign controlled by the detuning and power of a pump laser beam illuminating the atoms from the side, as depicted in Fig. 1c. It arises from Rayleigh scattering of photons from the pump into the cavity mode by the atomic gas. Second, the pair and charge-density waves are intrinsically coupled by the contact interactions in the unitary Fermi gas. Manifestations of this coupling can be found, for example, in the equation of state, where the two thermodynamic quantities describing density and pair-density have mutual dependence. Third, our system also features a direct, dispersive coupling between photons and fermion pairs with strength rΛ, by operating the cavity resonance at a finite frequency difference Δm ∝ −1/r of a photoassociation (PA) transition36, as shown in Fig. 1c. The parameter r can be interpreted as quantifying the interference between photons scattered off atoms on the one hand, and pairs of atoms on the other hand, into the cavity. Importantly, the direct coupling between the density and the pair-density orders contrasts with previous realizations of coupled orders in the cavity QED context, where different atomic modes scatter photons between a set of optical modes37, or in the case of magnetic textures38,39,40 where cross-couplings occur due to dissipation41.

Experimental observation

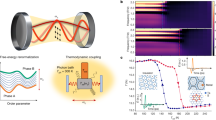

We investigate ordering through the observation of the onset of superradiance, as the relative coupling strength between light and atoms, and light and pairs, is increased. The experiment starts with a quantum degenerate, unitary Fermi gas comprising N = 5.2 × 105 6Li atoms at a temperature of T/TF ≈ 0.12, equally populating the two lowest hyperfine states within the mode of a high finesse cavity (see42 and “Methods”). As depicted in Fig. 2a, the spectrum of the coupled system close to the PA transition exhibits the characteristic avoided crossing pattern in the dispersive shift δc due to strong photon-pair coupling36. We use a retro-reflected, transverse pump beam with an absolute frequency within ±400 MHz of the PA transition and detuned by Δa/2π = − 25.25 GHz with respect to the atomic D2 transition. We focus on the PA transition, addressing the ν = 81 molecular bound states in the \(1{\Sigma }_{g}^{+}\) excited potential, already investigated in36. The pump strength is parametrized by the optical lattice depth V0, which it produces at the location of the atoms and is measured in units of the atomic recoil energy \({E}_{R}={\hslash }^{2}{k}_{p}^{2}/2m=h\times 73.67\) kHz. It controls the value of Λ34, while the detuning Δm with respect to the PA transition fixes r.

a Dispersive shift δc measured by transmission spectroscopy as a function of the molecular detuning Δm, showing the avoided crossing pattern characteristic of strong light-matter coupling. b Photon flux traces as a function of pump strength V0 while varying Δm across the photoassociation transition at fixed Δc/2π = −5.5 MHz. The blue-red line indicates the Fano-type phase boundary predicted in Fig. 1b, with an overall scaling factor left as a free parameter for the V0 axis, and the other parameters calculated using a mean-field theory. The two sharp features located around Δm/2π = 150 and 180 MHz are due to another weakly coupled photoassociation transition, leading to sharp losses without significantly affecting the atom-cavity coupling.

We detune the cavity resonance frequency by Δc/2π = −5.5 MHz from the pump frequency, thereby fixing the parameter ϵX. The pump lattice depth V0, proportional to the pump laser power, is then linearly increased over 400 μs until a lattice depth of 0.7 ER is reached, corresponding to a rate of \({\dot{V}}_{0}=1.75\times {E}_{{{\rm{R}}}}/{{\rm{ms}}}\), and the flux of photons from the cavity \({\bar{n}}_{\det }\) is monitored on a single-photon counter, measuring X2 in real time. The transition to the superradiant phase is manifested by a burst of photodetection events, allowing us to locate and track the critical pump strength V0C. Figure 2b shows photon flux traces collected as Δm is varied across the PA resonance. We observe the superradiant transition for both positive and negative values of Δm, with a pronounced asymmetry, directly demonstrating the contribution of pairs to the signal. Indeed, as ∣Δm∣ is reduced, the decrease of the critical pump strength for Δm < 0 and increase for Δm > 0 indicates cooperation and competition between charge and pair-density waves, respectively, and qualitatively reproduces the generic phase diagram presented in Fig. 1b. Overlayed with Fig. 2b, we present the phase boundary calculated from a mean-field, linear response theory (see below and “Methods”), leaving the background threshold Δm ⟶ ±∞ as a free parameter, showing good agreement and confirming our interpretation in terms of coupled orders.

In the close vicinity of the molecular transition, the signal is dominated by two-body losses due to spontaneous emission. Additionally, we observe a significant decay of the self-organized phase for Δm < 0 compared to Δm > 0, visible through the absence of cavity photons in the upper-left part of Fig. 2b. We attribute this difference to a combination of a larger photoassociation loss rate at high light intensity on the red side of the PA transition43, together with additional optomechanical instabilities due to the larger total dispersive coupling, which are also observed without molecular coupling. Below the critical pump strength, however, losses are both low and symmetric between positive and negative Δm (see “Methods” and Supplementary Fig. 2), thus the variations in the critical point are directly reflecting the interplay between light-matter and atom-atom interactions. For instance, even though approaching Δm = 0 increases losses, the threshold is nevertheless reduced for Δm < 0, indicating that the strong dispersive effects of the photon-pair coupling dominate over dissipative mechanisms. The substantial increase in the critical pump strength as Δm approaches zero from the positive side even suggests the existence of a regime where the coupling between X and Π is dominant.

To quantitatively connect the changes of the critical pump strength to the atomic and pair-density wave nature of the organized phase, we measured phase diagrams in the \({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{{{\rm{c}}}}-{V}_{0}\) plane at different Δm, where \({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) is the pump cavity-detuning corrected for the mean dispersive shift. This is illustrated in Fig. 3a for the example of Δm/2π = ±100 MHz. This approach enables us to separate the direct effect of coupling between orders from the variations in the dispersive shift. Indeed, the pump-cavity detuning is modified by the dispersive coupling to pairs, even in the absence of genuine coupling between orders, making it difficult to quantitatively ascribe the observations of Fig. 2b to the effect of strong interactions. From each phase diagram, we determine a mean critical reduced light-matter coupling strength \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}\), given by the slope of the linear dependence of the critical pump strengths on the cavity detuning (see Supplementary Fig. 1). In the absence of coupling between light and pairs, this represents the critical strength of the effective interaction between atoms mediated by the cavity and leading to self-organization31,34.

a Cavity photon count rate as a function of \({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) and pump strength V0, for Δm/2π = −100 MHz (red) and +100 MHz (blue), showing the onset of superradiance above a critical pump strength. The growing offset between the two phase boundaries between positive and negative Δm is a manifestation of the intertwining of density and contact-density wave order. b Normalized inverse critical coupling strength \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}},a}/{{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}\) as a function of the inverse detuning 2π/Δm at unitarity (open circles). The measurements agree with the predictions of the zero-momentum model (dashed green line) and the mean-field (solid yellow light), including trap averaging, within our error bars. The inset depicts measurements away from unitarity at 1/kFa = 0.22 (blue square) and 1/kFa = −0.16 (pink diamond) and the respective mean-field models (solid blue line, solid pink line).

The variations of \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}\) are presented in Fig. 3b as a function of 1/Δm ∝ −r, directly quantifying the coupling between the charge and pair density waves. We normalize these values by \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{\mathrm{C,a}}}\), corresponding to the atomic contribution alone at 1/Δm = 0, and plot the inverse of this ratio for comparison with theory. A significant variation of \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}\) is observed, reaching a 35% increase for cooperative coupling at 2π/Δm = −0.01 MHz−1, and a 20% decrease for competition at 2π/Δm = 0.01 MHz−1, indicating large atom-pair interactions.

To test the relationship between pairing in the gas and the superradiant transition, we reproduced these experiments with a Fermi gas prepared away from unitarity, which directly affects the coupling strength U between charge and pair-density waves via the pairing amplitude. The resulting variations of \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}/{{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{\mathrm{C,a}}}\) for positive and negative scattering lengths, corresponding to the BEC and BCS regimes, respectively, are presented as an inset of Fig. 3b, where the same trend as for the unitary Fermi gas is observed. At fixed Δm, the contribution of pairs is reduced as the system crosses over from BEC to BCS, where pairing and thus atom-pair coupling vanishes asymptotically. As we describe below, this tendency is reproduced by our theoretical model. We also checked that in a fully polarized Fermi gas, the photon-pair coupling is absent, thus U = 0 for all values of Δm.

Theoretical interpretation

Having established the correspondence between the experimentally observed Fano lineshape for the superradiant transition and the phenomenology of three coupled order parameters arising from Eq. (1), we now delve into the microscopics of our system, arguing that indeed the experiment faithfully realizes the physics described by Eq. (1). The microscopic order parameters for matter can be written as \(\Theta={\sum }_{Q,\sigma }\int \,d{{\bf{r}}}{e}^{i{{\bf{Q}}}\cdot {{\bf{r}}}}{\psi }_{\sigma }^{{\dagger} }({{\bf{r}}}){\psi }_{\sigma }({{\bf{r}}})\) and Π = ∑Q∫ dreiQ⋅rψ↑(r)ψ↓(r), where \({\psi }_{\sigma }^{{\dagger} }({{\bf{r}}})({\psi }_{\sigma }({{\bf{r}}}))\) is the fermionic creation (annihilation) operator at position r with spin σ. Q runs over the sum and difference between the pump and cavity fields wavevectors. Starting from the light-matter interaction Hamiltonian in the dispersive regime and following a canonical mean-field procedure, we derive explicitly the free energy as a function of the atomic (Θ, Π) and photonic (X) order parameters. To analyze the onset of the superradiant transition, we compute the Hessian of the free energy as a function of the coupled order parameters, deriving the analogs of the energy costs ϵΘ/Π and coupling U from microscopics through a set of corresponding linearized response susceptibilities. Within this analysis, the superradiant phase boundary is determined by:

where \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}={\Omega }_{a}{V}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}/{\widetilde{\Delta }}_{c}\) is the critical reduced light-matter coupling strength, Ωa is the dispersive shift per atom, Δ is the superfluid pairing gap, and \({\widetilde{\Omega }}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\) is an effective molecular coupling strength proportional to 1/Δm. For a unitary Fermi gas, mean field theory gives Δ = 0.69EF. The susceptibilities—χn,n, \({\chi }_{{{\rm{n,\eta }}}}^{{\prime} }\) and \({\chi }_{{{\rm{\eta,\eta }}}}^{{\prime} }\)—characterize fermionic density-density, density-pair-density, and pair-density-pair-density responses at the relevant momenta and depend only on fermionic degrees of freedom; for full details on the derivation starting from the microscopic Hamiltonian, see “Methods” and Ref. 44. The Fano-shaped phase boundary controlled by r in Eq. (1) results from the sign change of the effective molecular coupling \({\widetilde{\Omega }}_{m}\) across the PA resonance, tuning between competing and cooperating orders. Importantly, the position and the large asymmetry of the resonance profile directly reflect the strength of the cross-coupling of the two orders Θ, Π, which is captured by finite cross-susceptibilities \(\Delta {\chi }_{{{\rm{n,\eta }}}}^{{\prime} }=\Delta {\chi }_{{{\rm{\eta,n}}}}^{{\prime} }\) arising naturally from the strong correlations in the unitary Fermi gas.

We quantitatively compare the phase boundary given by Eq. (2) to the trap-averaged response function at finite momenta using a generalized random-phase approximation (RPA) to estimate the susceptibilities from first principles. The RPA results are shown by the solid lines in Fig. 3b and are in agreement with the experimental data. We also apply this approach away from unitarity, predicting a reduction of the cross-coupling as the system transitions from BEC to the BCS regime, as seen in the inset of Fig. 3b. In the BEC regime, the atom pairs are bound more tightly than in the BCS regime, increasing both the background value of Δ and the susceptibility Δχn,η coupling the atomic density and the pair-density waves.

The explicit appearance of the pairing gap in the phase boundary equation directly results from the coupling of light to atom pairs in the PA process, and highlights the pair-density wave nature of the ordered phase. More rigorously, light couples to atom pairs at a distance given by the Condon radius, much shorter than the Fermi wavelength. In the above expression, Δ should therefore be understood as the short-distance pairing field, comprising both condensed and non-condensed pairs45,46, and accurately described by Tan’s contact47. Therefore, the PA transition acts as an optical Feshbach resonance43,48, and the superradiant threshold as the system spontaneously modulates its scattering length. This yields a pair-density wave with a spontaneous modulation of the contact, the quantity canonically conjugate to scattering length (see “Methods” for details). In the long-wavelength approximation where ∣Q∣ ⟶ 0, this can be used to estimate the susceptibilities from the known variations of the contact with scattering length49,50,51. The results are shown with dashed lines in Fig. 3, showing a good agreement with the data.

Discussion

Our results show that strong coupling to light is a new mechanism for the formation of pair-density waves in quantum gases, i.e., a non-trivial spontaneous modulation of the pair-density in a Fermi superfluid, originating from strong interactions. While optical manipulation of two-body scattering using optical Feshbach resonances48 or closed-channel dressing52,53,54 has been shown in the past, the cavity QED framework allows for cooperative enhancement of such light-induced effects. As a result, even though these schemes may only weakly modify the two-body scattering properties, a pair-density wave can nevertheless emerge as a distinct phase at the collective, many-body level.

This state differs from pair-density waves investigated in the context of strongly correlated electrons19: First, it takes the form of a modulation of the short-range pair correlations, usually captured by Tan’s contact, and we expect that at high temperature or in the far BCS regime, the distinction between the pairing gap and the contact will require a description beyond our mean-field approach. Second, the modulation occurs on top of a large, uniform order parameter background originating from strong contact attraction, rather than as a sign-alternating pairing gap, as for example in the Fulde–Ferrell–Larkin–Ovchinnikov phase19,55. An important open question, both from the theoretical and experimental point of view, is the relationship between our observations of charge and pair order and superfluidity. More generally, the complete phase diagram and the type of transitions occurring in a system of fermions with strong contact interactions together with light-matter coupling to pairs remain to be explored56,57.

Experimentally, losses at the molecular transition have limited our investigations to situations in which the contact contribution remains smaller than the background atomic one. Losses will likely limit also the lifetime of the phases of matter reached above the threshold, restricting the range of techniques available to probe the nature of the organized phase. Two-electron atoms in optical cavities58,59,60, for which long-lived PA transitions are known to exist61,62,63,64, would be particularly suited to further investigate exotic quantum phases that could emerge in situations where pair coupling is dominant. Conversely, two-body, molecular losses are known to give rise to a variety of correlation phenomena65,66,67 that, together with the dissipation induced by the cavity, could be further studied in our experiment.

Last, adiabatically eliminating the cavity in the large detuning regime allows us to interpret our system as having infinite range photon-mediated atom-atom, atom-pair and pair-pair interactions. It demonstrates that cavity QED methods are suited to synthesize strong interactions beyond two-body68 in previously not accessible regimes69,70,71.

Methods

Experimental procedure

We start with a degenerate, unitary Fermi gas of temperature T/TF ≈ 0.12 with N = 5.2(3) × 105 6Li atoms equally populating the two lowest hyperfine states at unitarity of the broad Feshbach resonance at 832 G. The atoms are harmonically trapped with a radial trap frequency of 430 Hz and axial trap frequency of 28 Hz in a hybrid optical and magnetic trap, at the center of a high finesse optical cavity, following the procedure described in42. The latter has a length of 4.131(1) cm, a finesse of 4.7(1) × 104 and a waist of the TEM00 mode of 45.0(3) μm at 671 nm72. At the endpoint of evaporation, the unitary Fermi gas is well-described by a Gaussian profile with a full width at half maximum of 14(1) μm in the transverse direction relative to the cavity axis, and 250(17) μm along the axial direction of the cavity. For experiments at finite scattering length, we first prepare a unitary Fermi gas as described before, then adiabatically vary the magnetic field away from the Feshbach resonance. We induce cavity-mediated long-range interactions by illuminating the cloud from the side using a retro-reflected pump beam with π-polarization and an estimated beam waist of 201(8) m at the position of the atomic cloud. The pump and the cavity resonance are detuned with respect to the atomic D2 transition by − 25.25 GHz. There, the atoms induce a mean dispersive shift of the cavity resonance by δc = ΩaN/2 = −2π × 2.82(2) MHz due to the coupling to single atoms, largely exceeding the cavity linewidth κ = 2π × 77(1) kHz.

The experiment is performed in the vicinity of a strongly-coupled photoassociation transition, which is located at a detuning of −25.247 GHz from the zero-field D2 line of 6Li, corresponding to the ν = 81 molecular bound states in the \(1{\Sigma }_{g}^{+}\) excited potential. This photoassociation line was already investigated in36, where a single photon-pair coupling strength of gm = 2π × 383(3) kHz was determined, based on the estimation of the Condon radius Rc = 164a0 and width of the radial molecular orbital L = 12.6a0, and using the known Contact of the harmonically trapped unitary Fermi gas.

We perform linear ramps of the pump strength V0 = Ωa∣α∣2 (see below for notations) across the self-organization phase transition, while simultaneously recording the photon flux \({\bar{n}}_{\det }\) leaking from the cavity. The cavity photon leakage is detected with an efficiency of ~ 3%73. The linear pump ramp allows us to directly convert time into V0. We acquire phase diagrams for detunings from the dispersively-shifted cavity \({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{{{\rm{c}}}}={\Delta }_{{{\rm{c}}}}-{\delta }_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) between −2π × 0.2 MHz and −2π × 4 MHz. The pump lattice depth is calibrated using Kapitza-Dirac diffraction on a molecular BEC far away from the photoassociation transition, directly obtaining V0 without a pair-coupling contribution74.

The retro-reflected pump beam forms a standing wave that intersects the cavity axis at an angle of 18∘34, as presented schematically in Fig. 2b. This configuration results in different recoil momenta upon Rayleigh scattering between pump and cavity, k± = kc ± kp. The low-energy mode with momentum ℏk− dominates ordering at the phase boundary75.

Data analysis

We fit the onset of density wave ordering as a function of V0 i.e., the critical pump strength on each experimental trace, using a linear function:

with θ(V0 − V0C) the Heaviside function and fit parameters for critical pump strength V0C and the slope of the photon flux onset B. Each extracted \({V}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{{{\rm{c}}}})\) is subsequently converted in a long-range interaction strength \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{{{\rm{c}}}})={\Omega }_{{{\rm{a}}}}{V}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{{{\rm{c}}}})/{\widetilde{\Delta }}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) using the atomic dispersive coupling strength Ωa, as can be seen from Supplementary Fig. 1. To render \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}\) dimensionless, we use the total atom number N and the corresponding Fermi energy in the harmonic trap EF from absorption imaging, which is acquired together with the data for density wave ordering in a randomized manner. We observe a systematic shift of \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}N/{E}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\) to higher absolute values for small \({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\), which is due to the finite ramp speed of \({\dot{V} }_{0}=1.75\times {E}_{{{\rm{R}}}}/{{\rm{ms}}}\). Therefore, we extract \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}\) by averaging values at large detunings of \({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{{{\rm{c}}}}/{\delta }_{{{\rm{c}}}} > 0.75\). We still observe an absolute atomic value at unitarity of D0C,aN/EF = −2.05, which is a factor of two higher than the value reported in75.

Atom losses

We estimate the upper bound on the atom loss during the linear ramp of V0 until the critical pump strength V0C is reached, by measuring the losses at molecular detunings of Δm/2π = ±100 MHz using two consecutive dispersive shift measurements before and after the V0 ramp with a positive pump-cavity detuning, preventing the atoms from undergoing self-organization. The results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. This yields a maximal atom loss of ~25% until V0C is reached, which is encountered at the largest pump-cavity detuning \({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{c}\). We use σ-polarization for the loss measurement with the dispersive shift to avoid the systematic dispersive shift at π-polarization due to coupling to the photoassociation transition, which would make the apparent losses smaller (larger) for positive (negative) detunings.

Dispersively-coupled light-matter hamiltonian

In this section, we derive the Hamiltonian of the transversely pumped atom-cavity system with dispersive coupling to atoms and pairs. The Fermi gas inside the optical resonator is illuminated by a standing-wave, retro-reflected pump beam with a pump amplitude α and geometry as described in34. Due to the close detuning to a photoassociation transition, the combined pump and cavity light field \(\widehat{\phi }\) is not only coupled to atomic density, but also to a pair density. This results in a new type of dispersive light-matter interaction Hamiltonian:

with dispersive light-matter coupling strengths \({\Omega }_{i}={g}_{i}^{2}/{\Delta }_{i}\) for single atoms and pairs, i = a, m, the atomic density operator \(\hat{n}({{\bf{R}}})\) and the pair density operator \(\hat{{{\mathcal{B}}}}({{\bf{R}}})={\hat{P}}^{{\dagger} }({{\bf{R}}})\hat{P}({{\bf{R}}})\). The pair annihilation operator is given by:

with f(r) the molecular orbital of an excited molecular state to which the ground-state pair is coupled. The intensity of the total light field is:

where we have chosen a real pump field amplitude α = α*, and \(\hat{a}\) is the quantized cavity field. In the following, we assume Ωa to be constant, given the small variations of detuning to the atomic transition. We approximate the molecular orbital f(r) as a box centered at a Franck-Condon radius Rc with a width L36:

In the following, we neglect the pump-lattice potential for atoms and pairs. By introducing the dispersive shift contributions due to coupling to atoms and pairs:

we arrive at the full dispersively-coupled light-matter Hamiltonian:

with the Hamiltonian for a trapped, interacting Fermi gas \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{at}}}}\), Q = ± (kp ± kc) and the dispersively-shifted cavity detuning \({\widetilde{\Delta }}_{{{\rm{c}}}}=({\Delta }_{{{\rm{c}}}}-{\delta }_{c,a}-{\delta }_{c,p})\).

Mean-field free energy

In this section, we derive the effective free energy of the system as in Eq. (1), within the mean-field approximation. The bare atomic Hamiltonian Hat is given by the mean-field BCS Hamiltonian

where Δ is the BCS gap parameter, μ is the chemical potential, \({\xi }_{k}={{k}^{2}}/{{2}{m}}\) is the free fermion dispersion, and m is the atomic mass. To derive the effective free energy of the system, we mean-field decouple the interaction in the light-matter Hamiltonian given by Eq. (10). We expand the Hamiltonian, keeping all terms up to quadratic order in cavity field x, density operator \({\hat{\theta }}_{{{\bf{Q}}}}={\sum }_{k,\sigma }{\hat{c}}_{k+Q,\sigma }^{{\dagger} }{\hat{c}}_{k,\sigma }\) and pair-density operator \({\hat{\eta }}_{k,{{\bf{Q}}}}={\hat{c}}_{-k+Q,\downarrow }{\hat{c}}_{k,\uparrow }\). The light-matter coupling can then be grouped into two parts, coupling to the fermionic density

or to the fermionic pair-density

where \(\hat{x}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\hat{a}+{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} })\) and f(k) is the Fourier transform of the molecular wave function f(r) given in Eq. (7), which to first approximation simply provides a cut-off in momentum at kM = 1/Rc and a total molecular volume factor \({f}_{0}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}\pi }\sqrt{{R}_{C}^{2}L}\). Expanding the Hamiltonian in powers of Fermi-wavevector and the Frank-Condon Radius kFRc ≪ 1, simplifies to the total interaction term to take the form

where \({\hat{\eta }}^{{\prime} }=\frac{8{k}_{{{\rm{F}}}}{R}_{C}}{3{\pi }^{2}}{\sum }_{k}^{{k}_{M}}{\hat{\eta }}_{k,{{\bf{Q}}}}\) is an integrated pairing operator, with the cut-off set by the molecular wavefunction and \({\widetilde{\Omega }}_{m}={\Omega }_{m}\frac{3\pi {k}_{F}L}{16\pi }\). Note, in all the computations we keep track of the molecular cut-off and assume the hierarchy of scales \({k}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\ll \frac{1}{{R}_{c}}\ll \frac{1}{b}\), where b is the contact interaction range. Having derived the full mean-field Hamiltonian, we now proceed to compute the effective free energy in terms of the order parameters. We introduce three source terms hx, hΘ, hη, coupling to the order parameters and write the partition function as

The order parameters are defined as the derivatives of the partition function

To obtain the Landau-Ginzburg free energy, we perform a Legendre transform with respect to the source terms

Following44,76, we consider the free energy as parametrically dependent on the pump strength α. The Hellman-Feynman theorem imposes

where the expectation value is evaluated with a finite value of α. Integrating from α = 0, we obtain the (so far exact) expression:

where the expectation value is taken for the many-body state of the system at the running value of the pump strength \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\). \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}^{(0)}\) is the free energy of the atoms and cavity field in the absence of coupling via pump laser. Up to linear order in the coupling between the fermions and the cavity field, we can re-write the Free energy as

where we have ignored the dependence of the expectation value on \({\alpha }^{\prime}\) and separated the fermionic and cavity degrees of freedom in the expectation value, as in the absence of external coupling the expectation value decouples. We also identified \(\Lambda=-\sqrt{2}{\Omega }_{a} \alpha\) and \(r=\frac{{\bar{\Omega }}_{m}}{{\Omega }_{a}}\frac{\Delta }{{E}_{{{\rm{F}}}}}\). The uncoupled part of free energy can be split into cavity and fermionic part \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}^{(0)}={\Delta }_{c}{X}^{2}+{{{\mathcal{F}}}}^{(F)}\), where \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}^{(F)}\) is the free energy of interacting free fermions. For the fermionic variables Θ, Π, by performing the Legendre transformation as defined above it follows that

To obtain the free energy up to the quadratic coefficient, we need to compute the second derivative of the free energy, w.r.t. the order paramereters i.e. \(\frac{{\delta }^{2}{{{\mathcal{F}}}}^{(F)}}{\delta \Theta \delta \Theta }\). By differentiating the above equation we obtain:

By definition of the response functions, it follows \(\frac{1}{N}\frac{{\delta }^{2}\log Z[h]}{\delta (\beta {h}_{k})\delta (\beta {h}_{j})}={\chi }_{k,j}\), where N is the fermion number. Inverting the above relation gives

where χn,n is the density-density response function of the system, \(\Re {\chi }_{{{\rm{n,\eta }}}}^{{\prime} }\) is the real part of the regularized density-pairing response and \({\chi }_{{{\rm{\eta,\eta }}}}^{{\prime} }\) is the regularized pairing-pairing response function. The response functions are evaluated using the RPA response77,78, keeping track of the molecular cut-off kM. We can now identify \({\epsilon }_{\Theta }=\frac{1}{2N}\left(\frac{{\chi }_{{{\rm{\eta,\eta }}}}^{{\prime} }}{{\chi }_{{{\rm{n,n}}}}{\chi }_{{{\rm{\eta,\eta }}}}^{{\prime} }-| {\chi }_{{{\rm{\eta,n}}}}^{{\prime} }{| }^{2}}\right)\), \({\epsilon }_{\Pi }=\frac{1}{2N}\left(\frac{{\chi }_{n,n}}{{\chi }_{{{\rm{n,n}}}}{\chi }_{{{\rm{\eta,\eta }}}}^{{\prime} }-| {\chi }_{{{\rm{\eta,n}}}}^{{\prime} }{| }^{2}}\right)\) and \(U=\frac{1}{N}\left(\frac{\Re {\chi }_{{{\rm{\eta,n}}}}^{{\prime} }}{{\chi }_{{{\rm{n,n}}}}{\chi }_{{{\rm{\eta,\eta }}}}^{{\prime} }-| {\chi }_{{{\rm{\eta,n}}}}^{{\prime} }| }\right)\).

Phase-boundary

To compute the phase boundary, we compute the Hessian of the Free energy and require that one of the normal modes goes soft, i.e. the determinant of the Hessian is zero. Using notation from the main text, this gives the boundary equation

The equation in terms of the microscopic response functions reduces to

where \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}={\Omega }_{a}{V}_{0{{\rm{C}}}}/{\widetilde{\Delta }}_{c}\) is the critical reduced light-matter coupling strength.

Pair-density wave and Tan’s contact

After deriving the boundary equation in the mean-field picture, we generalize the approach to take into account the full many-body correlations. Our approach consists of two main steps: first, evaluating the molecular density operator \(\hat{{{\mathcal{B}}}}({{\bf{R}}})\), and second, employing linearized equations of motion, generalizing the previously developed approach in75,78. Given the separation of scales, b ≪ Rc ≪ 1/kF, where b is the range of the short-range contact interactions from the Feshbach resonance, we can utilize the operator product expansion25,79 to obtain:

up to leading order in 1/∣r∣. We define the operator \(\hat{C}({{\bf{R}}})={m}^{2}{U}^{2}{\hat{\psi }}_{\uparrow }^{{\dagger} }({{\bf{R}}}){\hat{\psi }}_{\downarrow }^{{\dagger} }({{\bf{R}}}){\hat{\psi }}_{\downarrow }({{\bf{R}}}){\hat{\psi }}_{\uparrow }({{\bf{R}}})\), which upon taking the expectation value is contact density at position R, \(\langle \hat{C}({{\bf{R}}})\rangle=C({{\bf{R}}})\), and U represents the contact interaction strength, requiring appropriate renormalization (see below). Using the simple excited-state molecular wave function model given in Eq. (7), we obtain for the ground state and excited state overlap integral:

Absorbing the molecular factor into the coupling constant gives the final effective Hamiltonian

where now we re-define \({\widetilde{\Omega }}_{{{\rm{m}}}}={k}_{{{\rm{F}}}}L{\Omega }_{{{\rm{m}}}}/4\pi\), kF is the Fermi wave vector and the density and contact-density wave operator at wave vector Q are now defined as

Therefore, we see that the light-matter Hamiltonian contains two different ordering channels: the density and the contact-density. Having separated the Hamiltonian in this form, the boundary equation directly follows, with the mean-field response functions replaced \(\frac{\Delta }{{E}_{{{\rm{F}}}}}{\chi }_{n,\eta }^{{\prime} }\to {\chi }_{n,C}\) and \(\frac{{\Delta }^{2}}{{E}_{{{\rm{F}}}}}{\chi }_{\eta,\eta }^{{\prime} }={\chi }_{C,C}\), where χn,C is the density-contact and χC,C is the contact-contact response function. The boundary equation can be written as

which can also be re-cast in the form of a Fano-resonance explicitly

Note, the only approximation in this approach is the decoupling of fermionic and cavity degrees of freedom, which should be valid close to the phase transition. The main challenge remains evaluating the density-contact and the contact-contact response functions.

Zero-momentum response functions

In the zero-momentum limit, Q → 0, the phase boundary equation can be exactly evaluated using thermodynamic relations. To illustrate the general approach, consider the density-density response, which reduces to the compressibility: \({\chi }_{n,n}{\to }^{{{\bf{Q}}}\to 0}-\frac{1}{N}\frac{\partial N}{\partial \mu }\), where N is the total atom number. To derive this relation, we introduce an external perturbation coupling to density, Hext = ϕθQ. As Q → 0, this simplifies to Hext = ϕN. In the grand-canonical ensemble, we identify ϕ = − δμ, meaning that adding a small external field corresponds to shifting the chemical potential μ by −δμ. From the standard definition of the response function, it follows that:

To derive analogous relations for the case of an external perturbation coupling to the contact, we consider \({H}_{{{\rm{ext}}}}={\phi }^{{\prime} }{\Pi }_{Q}\). Taking the limit Q → 0 limit, we find that 〈Πq〉 → C, which corresponds to the total contact.

By comparing the familiar adiabatic sweep relation \(\delta E-=\frac{1}{4\pi m}C\delta ({a}^{-1})\)25 with the energy variation due to the external perturbation \(\delta E=C{\phi }^{{\prime} }\), we can directly identify \({\phi }^{{\prime} }=\frac{1}{4\pi m}\delta (-{a}^{-1})\). Microscopically, the field \({\phi }^{{\prime} }\) can be thought of as resulting from a second order coupling to a molecular channel at short distance, achieved either with a traditional magnetically induced Feshbach resonance, or in our case optically via coupling to the photo-association line. In the latter case, our treatment is equivalent to that of optical Feshbach resonances43.

It is important to note that this identification assumes the chemical potential μ remains constant as 1/a is varied. Following this identification, we obtain:

Using the relations between N, C, μ in the microcanonical ensemble, these can be related to second derivatives of energy E(N, a)

where we keep N, a fixed when evaluating ∂/∂a, ∂/∂N respectively. The above expression explicitly satisfies the stability condition, \(\det (\chi ) > 0\), while ensuring that all the response functions remain negative, as required by stability. To evaluate the responses, we use the internal energy expansion at unitarity in terms of 1/kFa at zero temperature80,81

where we use ξ ≈ 0.383, ζ ≈ 0.901 and ν ≈ 0.49 from Monte Carlo simulations82. The resulting phase boundary curve for the unitary Fermi gas is plotted in Fig. 3b in the main text.

Data availability

The experimental data supporting this study’s findings are available in83.

Code availability

Codes are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Sachdev, S. In: Cabra, D.C., Honecker, A., Pujol, P. (eds.) Quantum phase transitions of antiferromagnets and the cuprate superconductors. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2012).

Fernandes, R. M., Orth, P. P. & Schmalian, J. Intertwined vestigial order in quantum materials: nematicity and beyond. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 10, 133–154 (2019).

Fradkin, E., Kivelson, S. A. & Tranquada, J. M. Colloquium: theory of intertwined orders in high temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 457–482 (2015).

Zaanen, J. Quantum phase transitions in cuprates: stripes and antiferromagnetic supersolids. Phys. C. 317-318, 217–229 (1999).

Chakravarty, S., Laughlin, R. B., Morr, D. K. & Nayak, C. Hidden order in the cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 63, 094503 (2001).

Zhou, H. et al. Isospin magnetism and spin-polarized superconductivity in Bernal bilayer graphene. Science 375, 774–778 (2022).

Balents, L., Dean, C. R., Efetov, D. K. & Young, A. F. Superconductivity and strong correlations in moiré flat bands. Nat. Phys. 16, 725–733 (2020).

Nandkishore, R., Levitov, L. S. & Chubukov, A. V. Chiral superconductivity from repulsive interactions in doped graphene. Nat. Phys. 8, 158–163 (2012).

K.F. Wang, J.-M. L. & Ren, Z. F. Multiferroicity: the coupling between magnetic and polarization orders. Adv. Phys. 58, 321–448 (2009).

Fiebig, M., Lottermoser, T., Meier, D. & Trassin, M. The evolution of multiferroics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 1–14 (2016).

Khomskii, D. I. Multiferroics: different ways to combine magnetism and ferroelectricity. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 306, 1–8 (2006).

Zhang, Y., Demler, E. & Sachdev, S. Competing orders in a magnetic field: spin and charge order in the cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 66, 094501 (2002).

Amin, A. & Agterberg, D. F. Generalized spin fluctuation feedback in heavy fermion superconductors. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013381 (2020).

Demler, E., Sachdev, S. & Zhang, Y. Spin-ordering quantum transitions of superconductors in a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 067202 (2001).

Carlson, E., Kivelson, S., Orgad, D., Emery, V. Concepts in High Temperature Superconductivity. 275–451 (Springer, 2004).

Esterlis, I. et al. Breakdown of the migdal-eliashberg theory: a determinant quantum monte carlo study. Phys. Rev. B 97, 140501 (2018).

Yang, C. N. η pairing and off-diagonal long-range order in a Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 63, 2144–2147 (1989).

Lee, P. A. Amperean pairing and the pseudogap phase of cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031017 (2014).

Agterberg, D. F. et al. The physics of pair-density waves: cuprate superconductors and beyond. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 11, 231–270 (2020).

Zhang, S.-C. A unified theory based on so(5) symmetry of superconductivity and antiferromagnetism. Science 275, 1089–1096 (1997).

Lin, H.-H., Balents, L. & Fisher, M. P. A. Exact so(8) symmetry in the weakly-interacting two-leg ladder. Phys. Rev. B 58, 1794–1825 (1998).

Nagao, H., Nishino, M., Shigeta, Y., Yoshioka, Y. & Yamaguchi, K. Theoretical studies on superconducting and other phases: triplet superconductivity, ferromagnetism, and ferromagnetic metal. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 80, 721–732 (2000).

Podolsky, D., Altman, E., Rostunov, T. & Demler, E. So(4) theory of antiferromagnetism and superconductivity in Bechgaard salts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 246402 (2004).

Hamidian, M. H. et al. Detection of a cooper-pair density wave in bi2sr2cacu2o8+x. Nature 532, 343–347 (2016).

Zwerger, W. The BCS-BEC crossover and the unitary fermi gas. Lecture notes in physics. 836. (Springer, Berlin, 2012).

Black, A. T., Chan, H. W. & Vuletic, V. Observation of collective friction forces due to spatial self-organization of atoms: from rayleigh to bragg scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 203001 (2003).

Slama, S., Bux, S., Krenz, G., Zimmermann, C. & Courteille, P. W. Superradiant rayleigh scattering and collective atomic recoil lasing in a ring cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 053603 (2007).

Baumann, K., Guerlin, C., Brennecke, F. & Esslinger, T. Dicke quantum phase transition with a superfluid gas in an optical cavity. Nature 464, 1301–1306 (2010).

Klinder, J., Keßler, H., Wolke, M., Mathey, L. & Hemmerich, A. Dynamical phase transition in the open dicke model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3290–3295 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Observation of a superradiant quantum phase transition in an intracavity degenerate fermi gas. Science 373, 1359–1362 (2021).

Mivehvar, F., Piazza, F., Donner, T. & Ritsch, H. Cavity qed with quantum gases: new paradigms in many-body physics. Adv. Phys. 70, 1–153 (2021).

Klinder, J., Keßler, H., Bakhtiari, M. R., Thorwart, M. & Hemmerich, A. Observation of a superradiant Mott insulator in the Dicke-Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 230403 (2015).

Landig, R. et al. Quantum phases from competing short- and long-range interactions in an optical lattice. Nature 532, 476–479 (2016).

Helson, V. et al. Density-wave ordering in a unitary fermi gas with photon-mediated interactions. Nature 618, 716–720 (2023).

Randeria, M. & Taylor, E. Crossover from bardeen-cooper-schrieffer to bose-einstein condensation and the unitary fermi gas. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 5, 209–232 (2014).

Konishi, H., Roux, K., Helson, V. & Brantut, J.-P. Universal pair polaritons in a strongly interacting fermi gas. Nature 596, 509–513 (2021).

Morales, A., Zupancic, P., Léonard, J., Esslinger, T. & Donner, T. Coupling two order parameters in a quantum gas. Nat. Mater. 17, 686–690 (2018).

Kroeze, R. M., Guo, Y., Vaidya, V. D., Keeling, J. & Lev, B. L. Spinor self-ordering of a quantum gas in a cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 163601 (2018).

Landini, M. et al. Formation of a spin texture in a quantum gas coupled to a cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 223602 (2018).

Kongkhambut, P. et al. Realization of a periodically driven open three-level dicke model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 253601 (2021).

Dogra, N. et al. Dissipation-induced structural instability and chiral dynamics in a quantum gas. Science 366, 1496–1499 (2019).

Bühler, T. N. C. et al. Direct production of fermionic superfluids in a cavity-enhanced optical dipole trap. SciPost Phys. 18, 133 (2025).

Chin, C., Grimm, R., Julienne, P. & Tiesinga, E. Feshbach resonances in ultracold gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1225–1286 (2010).

Dupuis, N. Field Theory of Condensed Matter and Ultracold Gases. (World Scientific Europe,2023).

Altman, E. & Vishwanath, A. Dynamic projection on feshbach molecules: a probe of pairing and phase fluctuations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 110404 (2005).

Haussmann, R., Punk, M. & Zwerger, W. Spectral functions and rf response of ultracold fermionic atoms. Phys. Rev. A 80, 063612 (2009).

Braaten, E. & Platter, L. Exact relations for a strongly interacting fermi gas from the operator product expansion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 205301 (2008).

Theis, M. et al. Tuning the scattering length with an optically induced feshbach resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 123001 (2004).

Navon, N., Nascimbène, S., Chevy, F. & Salomon, C. The equation of state of a low-temperature Fermi gas with tunable interactions. Science 328, 729 (2010).

Horikoshi, M., Koashi, M., Tajima, H., Ohashi, Y. & Kuwata-Gonokami, M. Ground-state thermodynamic quantities of homogeneous spin-1/2 fermions from the bcs region to the unitarity limit. Phys. Rev. X 7, 041004 (2017).

Jäger, M. & Denschlag, J. H. Precise photoexcitation measurement of Tan’s contact in the entire BCS-BEC crossover. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 263401 (2024).

Bauer, D. M., Lettner, M., Vo, C., Rempe, G. & Dürr, S. Control of a magnetic feshbach resonance with laser light. Nat. Phys. 5, 339 (2009).

Clark, L. W., Ha, L.-C., Xu, C.-Y. & Chin, C. Quantum dynamics with spatiotemporal control of interactions in a stable bose-einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 155301 (2015).

Jagannathan, A., Arunkumar, N., Joseph, J. A. & Thomas, J. E. Optical control of magnetic feshbach resonances by closed-channel electromagnetically induced transparency. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 075301 (2016).

Kinnunen, J. J., Baarsma, J. E., Martikainen, J.-P. & Törmä, P. The Fulde–Ferrell–Larkin–Ovchinnikov state for ultracold fermions in lattice and harmonic potentials: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 81, 046401 (2018).

Sharma, S., Chwedeńczuk, J., Wasak, T. Engineering interactions by collective coupling of atom pairs to cavity photons for entanglement generation. Phys. Rev. Research 7, L012038 (2025).

Chen, Y. et al. Atom-molecule superradiance and entanglement with cavity-mediated three-body interactions. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.09497 (2025).

Norcia, M. A. & Thompson, J. K. Strong coupling on a forbidden transition in strontium and nondestructive atom counting. Phys. Rev. A 93, 023804 (2016).

Kawasaki, A. et al. Geometrically asymmetric optical cavity for strong atom-photon coupling. Phys. Rev. A 99, 013437 (2019).

Rivero, D. et al. High-resolution laser spectrometer for matter wave interferometric inertial sensing with non-destructive monitoring of Bloch oscillations. Appl. Phys. B 128, 44 (2022).

Enomoto, K., Kasa, K., Kitagawa, M. & Takahashi, Y. Optical Feshbach resonance using the intercombination transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 203201 (2008).

Blatt, S. et al. Measurement of optical Feshbach resonances in an ideal gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 073202 (2011).

Höfer, M. et al. Observation of an orbital interaction-induced Feshbach resonance in 173Yb. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 265302 (2015).

Pagano, G. et al. Strongly interacting gas of two-electron fermions at an orbital Feshbach resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 265301 (2015).

Tomita, T., Nakajima, S., Danshita, I., Takasu, Y., Takahashi, Y. Observation of the Mott insulator to superfluid crossover of a driven-dissipative Bose-Hubbard system. Sci. Adv. 3 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1701513 (2017).

Yamamoto, K., Nakagawa, M., Tsuji, N., Ueda, M. & Kawakami, N. Collective excitations and nonequilibrium phase transition in dissipative fermionic superfluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 055301 (2021).

Huang, C.-H., Giamarchi, T. & Cazalilla, M. A. Modeling particle loss in open systems using Keldysh path integral and second order cumulant expansion. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 043192 (2023).

Luo, C. et al. Realization of three- and four-body interactions between momentum states in a cavity. Science 390, 925 (2025).

Kraemer, T. et al. Evidence for Efimov quantum states in an ultracold gas of caesium atoms. Nature 440, 315–318 (2006).

Petrov, D. S. Three-body interacting bosons in free space. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 103201 (2014).

Hammond, A., Lavoine, L. & Bourdel, T. Tunable three-body interactions in driven two-component Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 083401 (2022).

Roux, K., Helson, V., Konishi, H. & Brantut, J.-P. Cavity-assisted preparation and detection of a unitary fermi gas. N. J. Phys. 23, 043029 (2021).

Helson, V. et al. Optomechanical response of a strongly interacting Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 033199 (2022).

Gadway, B., Pertot, D., Reimann, R., Cohen, M. G. & Schneble, D. Analysis of Kapitza-Dirac diffraction patterns beyond the Raman-Nath regime. Opt. Express 17, 19173–19180 (2009).

Zwettler, T. et al. Nonequilibrium dynamics of long-range interacting fermions. Phys. Rev. X 15, 021089 (2025).

Georges, A. Strongly correlated electron materials: dynamical mean-field theory and electronic structure. AIP Conf. Proc. 715, 3–74 (2004).

Zhao, H., Gao, X., Liang, W., Zou, P. & Yuan, F. Dynamical structure factors of a two-dimensional fermi superfluid within random phase approximation. N. J. Phys. 22, 093012 (2020).

Marijanović, F. et al. Dynamical instabilities of strongly interacting ultracold fermions in an optical cavity. (2024).

Inguscio, M., Ketterle, S.S. W., Roati, G. (eds.) Quantum Matter at Ultralow Temperatures, Proceedings of International School of Physics Enrico Fermi, Course CXCI. (IOS Press, 2016).

Bulgac, A. & Bertsch, G. F. Collective oscillations of a trapped Fermi gas near the unitary limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 070401 (2005).

Chang, S. Y., Pandharipande, V. R., Carlson, J. & Schmidt, K. E. Quantum Monte Carlo studies of superfluid Fermi gases. Phys. Rev. A 70, 043602 (2004).

Gandolfi, S., Schmidt, K. E. & Carlson, J. BEC-BCS crossover and universal relations in unitary Fermi gases. Phys. Rev. A 83, 041601 (2011).

Zwettler, T. et al. Cavity-mediated charge and pair-density waves in a unitary fermi gas. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17542764 (2025).

Acknowledgments

We thank Felix Werner, Markus Mueller, Aurélien Fabre and Gaia Bolognini for useful discussions. TZ, TB, GDP, VH and JPB acknowledge funding from the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (Grants No. MB22.00063 and 20QU-1_215924). FM, SC, LS and ED acknowledge funding from the SNSF project 200021_212899, the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) under contract number UeM019-1, and NCCR SPIN, a National Center of Competence in Research, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 225153). SU acknowledges funding from JST PRESTO (Grant No. JPMJPR235) and JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. JP21K03436).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Z., T.B., G.D.P. and V.H. performed experimental work, with theoretical support from S.U. F.M., S.C. and L.S. performed theoretical work. J.P.B. and E.D. supervised the experimental and theoretical work, respectively. T.Z., F.M. and J.P.B. wrote the paper with contributions from all authors. All the authors contributed to discussing the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Randy Hulet, Haibin Wu and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zwettler, T., Marijanovic, F., Bühler, T. et al. Cavity-mediated charge and pair-density waves in a unitary Fermi gas. Nat Commun 17, 496 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67184-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67184-8